As governments have struggled to suppress the spread of COVID-19, they have resorted to extraordinary and often draconian measures, such as restrictions on individual movements, physical distancing requirements, surveillance of civilians and border closures. Although these lockdown measures are extraordinary, so was the public's initial response to them. Studies suggest that compliance with social distancing and hygiene advice at the onset of the pandemic was widespread and that public support for policy measures that limit individual freedoms such lockdowns was high (Fetzer et al., Reference Fetzer, Hensel, Jachimowicz, Haushofer, Ivchenko, Caria, Reutskaja, Roth, Fiorin, Gomez, Kraft-Todd, Goetz, Yoeli and Gadarian2020). Notably, incumbents around the globe also experienced rising popularity (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Damien Bol, Giani and Loewen2020; Bøggild and Jensen, Reference Bøggild and Jensen2020; Jennings, Reference Jennings2020; Leininger and Schaub, Reference Leininger and Schaub2020). Even the approval of President of the United States Donald J. Trump, who has faced sustained criticism for his slow response to the crisis, rose at the start of the COVID-19 outbreak to the highest ever with 49 percent of adults in the United States approving of his performance (Jones, Reference Jones2020).

This raises the question of whether the increase in governments’ popularity at the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak was primarily driven by their actual policy response to the crisis or whether some other mechanisms were at work. There are indications that the sudden rise in government popularity may not be entirely due to government performance at the beginning of the crisis. Not only did approval ratings increase in many countries ahead of governments taking action, the policy responses to the outbreak varied significantly both in terms of their timing and effectiveness. Some government leaders, such as French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, were quick to issue grave warnings, others, like President Trump or British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, initially played down the danger of virus. Also, the preparedness to the crisis varied across countries. For example, although tests were widely available and used in Germany, this was not the case in all other European countries or in the United States. Nonetheless, incumbents all saw their popularity increase at the start of the outbreak (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Damien Bol, Giani and Loewen2020; Jennings, Reference Jennings2020; Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee, Milojev, Bulbulia, Osborne, Milfont, Houkamau, Duck, Vickers-Jones and Barlow2020).

In this study, we aim to delve deeper into this phenomenon by examining how the first lockdown on European soil affected incumbent support in other European countries. We use the decision of the Italian government to implement a nationwide lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak as a kind of quasi natural experiment that allows us to shed light on the degree to which citizens evaluate politicians in the initial phase of a crisis on the basis of concrete policy decisions or something else more prospective. We are fortunate that an eupinions survey was in the field in France, Germany, Poland and Spain just before and after the Italian lockdown, which allows us to isolate the effect of the Italian lockdown before these countries had a chance to enact their own lockdowns. Our results suggest that citizens in these countries reacted to the Italian lockdown by increasing support for their governments, even in the absence of a similar domestic government response. We contend that these findings suggest that the Italian lockdown alerted citizens in other European countries about how grave the unfolding crisis was, leading them to increase support for their government.

The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, our findings contribute to an emerging literature on the political consequences of COVID-19 by offering systematic evidence that the crisis response in one country had an effect on incumbent support in another. Second, our results inform the literature on performance voting by showing that large shifts in incumbent support can occur independently of an explicit change in incumbent performance. Third, our findings have important implications for understanding accountability during crises. Our evidence suggests that in times of crisis an exogenous shock abroad—not directly related to incumbent performance—may nonetheless affect domestic support for the incumbent. As such our findings highlight the importance of how developments abroad can affect incumbent approval at home. Our paper adds to a growing body of literature on economic voting highlighting how international economic developments, such as commodity shocks or remittances flows as well as international benchmarks, affect incumbent popularity (Kayser and Peress, Reference Kayser and Peress2012; Campello and Zucco Jr, Reference Campello and Zucco2014, Reference Campello and Zucco2020; Tertchayna et al., Reference Tertchayna, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). Our findings lend credence to the idea that ordinary citizens find it difficult to disentangle performance signals from exogenous shocks, at least during the early phase of a crisis.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, we consider the emerging literature on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on political attitudes and incumbent support. Second, we present our argument that the Italian lockdown provided a “crisis signal” that influenced support for governments across Europe. Third, we introduce the specific case and data, namely an eupinions survey in the field at the time of the Italian lockdown. Thereafter, we present the empirical model and variables and the results that clearly indicate that the “signal” of the Italian lockdown made citizens in other European countries more supportive of their own governments. We conduct various robustness checks to show that this effect holds even when controlling for domestic developments and restricting the samples to just the period before national lockdowns. Finally, we discuss the possible mechanisms driving these results in greater detail and consider the wider implications of our findings for the literature on incumbent approval and vote choice.

1. Why would Italy's lockdown affect incumbent support in other countries?

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected nearly every aspect of economic, social and political life across the globe. Although the novel coronavirus originated in China in late 2019, it quickly spread to other parts of the world, from Asia via Europe to the United States. By April 2020, virtually every country in the world reported infections, and Europe and the United States were among the hardest-hit. In the United States, the response to COVID-19 has been deeply political. Studies suggest that elite messaging from the administration of President Donald J. Trump and conservative media hosts, like Sean Hannity on Fox News, have produced a differential mass public health response among conservative voters who comply less with social distancing measures (Allcott et al., Reference Allcott, Levi Boxell, Conway, Gentzkow, Thaler and Yang2020; Bursztyn et al., Reference Bursztyn, Rao and Yanagizawa-Drott2020; Gadarian et al., Reference Gadarian, Goodman and Pepinsky2020). In contrast, the crisis response in Europe has been far less polarized. Although some of the policy measures introduced in Europe have been among the most stringent globally, compliance with and support for the restrictions to individual movements and gatherings as well as health advice among Europeans has been high, even among those who do not trust the government (Barari et al., Reference Barari, Caria, Davola, Falco, Fetzer, Thiemo, Ivchenko, Jachimowicz, King, Kraft-Todd, Ledda, MacLennan, Mutoi, Pagani, Reutskaja, Roth and Slepoi2020; Fetzer et al., Reference Fetzer, Hensel, Jachimowicz, Haushofer, Ivchenko, Caria, Reutskaja, Roth, Fiorin, Gomez, Kraft-Todd, Goetz, Yoeli and Gadarian2020)—albeit with differences based on socio-demographic or personality profile (Brouard et al., Reference Brouard, Vasilopoulos and Becher2020; Zettler et al., Reference Zettler, Schild, Lilleholt and Böhm2020).

Early evidence suggests that Europeans rallied around their political leaders and institutions. Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Damien Bol, Giani and Loewen2020) for example use an interrupted time series fielded in March and April 2020 to study the effects on a set of key political attitudes of the enforcement of a lockdown policy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors find that lockdown policies rally individuals around institutions: they increased vote intentions for the party of the Prime Minister/President, trust in government and satisfaction with democracy. Leininger and Schaub (Reference Leininger and Schaub2020) exploit variation in the number of confirmed cases at the county level to estimate the effect of the health crisis on political behavior and find that it benefited the dominant party in Bavaria. Finally, Bøggild and Jensen (Reference Bøggild and Jensen2020) use a panel survey among Danish citizens who were interviewed before and after the outbreak to show that after the outbreak Danish respondents display higher trust in politicians, more satisfaction with democracy, more support for the incumbent party and greater interest in politics.

We contribute to this emerging literature by focusing on how the policy reaction in one European country has affected incumbent support in other European countries. Our motivation for this is the observation that the sudden rise in government popularity in Europe appears not to reflect government performance at the beginning of the crisis, since the change approval in many European countries pre-dated government responses to the outbreak (Jennings, Reference Jennings2020). Moreover, we have witnessed a considerable variation in the type of responses, their perceived effectiveness across Europe and levels of preparedness. Some government leaders, such as French president Emmanuel Macron or German Chancellor Angela Merkel, adopted a sombre tone, others, like British Prime Minister Boris Johnson or Stefan Löfven Swedish Prime Minister, initially played down the danger of virus, highlighting that no real policy changes were needed. Yet, what these incumbents all have in common is that their popularity increased at the start of the pandemic outbreak (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Damien Bol, Giani and Loewen2020; Jennings, Reference Jennings2020).

According to the retrospective evaluation model, voters should reward parties when times are good and punish them when times are bad. After all, politicians always promise that their policies will benefit voters. However, the only way for voters to ensure that the politicians in power will seek policies that benefit them is to evaluate politicians retrospectively based on the past performance of their policies as opposed to evaluating them prospectively on what they promise to do (Barro, Reference Barro1973; Ferejohn, Reference Ferejohn1986). Although there is substantial evidence that policy outcomes, such as economic performance, correlate with election outcomes, a good deal of debate remains over how well the evidence aligns with the thesis that voters behave “rationally” (see Healy and Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013). For instance, studies have shown that voters sometimes evaluate politicians retrospectively on the basis of outcomes that are seemingly unrelated to public policy, such as the outcome of sporting events, financial remittances from abroad or natural disasters (e.g., Arceneaux and Stein, Reference Arceneaux and Stein2006; Healy et al., Reference Healy, Kuo and Malhotra2010; Tertchayna et al., Reference Tertchayna, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). Yet, just because voters at times punish politicians for outcomes that are outside of their control does not necessarily offer evidence of voter “irrationality,” since these exogenous events may allow voters to learn something about the way in which incumbents manage exogenous shocks and about their level of preparedness (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, de Mesquita and Friedenberg2018).

Distinguishing between competence signals and exogenous shocks, that is, events largely outside of the control of incumbents, is far from straightforward. Although some evidence suggests that voters are able to tell them apart it when it comes to the economy (Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008), recent study has challenged this assumption, especially in low-information environments (Campello and Zucco Jr, Reference Campello and Zucco2014, Reference Campello and Zucco2020; Tertchayna et al., Reference Tertchayna, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). Campello and Zucco Jr (Reference Campello and Zucco2014), for example, argue that sometimes developments from abroad are the only signal or source of information about incumbent competence that voters have and thus may serve as the basis for incumbent evaluation.

The immediate effect of the Italian lockdown on the evaluation of governments outside of Italy sheds light on this debate. From the perspective of those living outside of Italy, the Italian lockdown reflected a radical policy action of another country to an unprecedented public health crisis. The question is whether this external event can be seen to provide information to voters about their own government that can be used to fairly evaluate their performance, in line with the retrospective evaluation model, or whether alternative explanations are more plausible. In the days right after the Italian lockdown, voters could not have learned very much about what their own government was doing to manage the pandemic. As such, the appropriate response would have been to take a “wait and see” attitude, leaving evaluations of incumbent performance unchanged. Moreover, even if the Italian lockdown led voters to learn about the policies of their government, the countries we study had not yet announced major policy actions to tackle the spread of the virus within their own borders,Footnote 1 which suggest that this exogenous event had no direct bearing on the performance on incumbents in neighboring countries. However, in line with a rational choice perspective, external events, like the Italian lockdown, can provide information to voters about their own government by helping them to better understand their country's preparedness to crises (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, de Mesquita and Friedenberg2018). For example, after the Italian government decided to enforce a lockdown, voters in other countries may have felt the need to inform themselves about their country's preparedness for the pandemic. Yet, such a voter response would require very high levels of political interest and sophistication and, as we will show in the case description section, we find little evidence of votes actively trying to inform themselves about their country's level of preparedness in the immediate aftermath of the Italian lockdown.

So, why did voters uniformly improve their assessment of government parties in the direct aftermath of the Italian lockdown? Research on communication and psychological models that highlight the role of issue salience (e.g., Iyengar and Kinder, Reference Iyengar and Kinder2010) and emotions (e.g., Albertson and Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015) can provide a plausible explanation for this response. Psychological models, in contrast to classical rational choice models, incorporate the possibility that people's evaluations can be biased by the decision-making context. Anxiety, for instance, causes people to be more averse to losses, biasing how they process political information (Arceneaux, Reference Arceneaux2012). Existential threats require collective responses as a way to avoid losses, and as a result, they often motivate individuals to cope with the anxiety that it generates by increasing their support for government and leaders who choose decisive action (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Solomon, Maxfield, Pyszczynski and Greenberg2004; Kay et al., Reference Kay, Shepherd, Blatz, Chua and Galinsky2010).

In this way, the Italian lockdown may have served as a “crisis signal” that made the significance of the existential threat caused by the spread of the coronavirus and the magnitude of the crisis salient in the mind of voters. This bears similarities to other international crises, such as wars or terrorist attacks, that have also been shown to create a rally-round-the-flag effect, driving citizens to rally around the incumbent and giving a short-term boost to their support (Baker and Oneal, Reference Baker and Oneal2001). Although a virus is a very different sort of external enemy, the emotional response of an emerging public health threat could have a similar effect. Despite some important differences between the various explanations for the rally-round-the-flag effect, many studies have emphasized that a salient threat engenders an emotional response that motivates people to affiliate themselves with the incumbent, for example, the American president, who offers a symbolic sense of ingroup belonging and safety (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Schott and Scherer2011). One such emotional response is collective angst, a group-based emotion that is elicited when people believe a threat to the in-group exists. This can motivate specific group-based behavior, and lead to a support for the incumbent as the embodiment of the nation (Porat et al., Reference Porat, Tamir, Wohl, Gur and Halperin2019). Similarly, as a reaction to the realization that a pandemic was unfolding, many citizens may have increased their support for their government as a way to manage their anxiety and express a sense of patriotism, as opposed to a thoughtful judgment of their governments’ handling of the nascent crisis. This is not to say that these voters are “irrational.” Indeed, it seems likely that as the crisis unfolds they will update their assessment of their government in light of the way it manages it. Yet, it does suggest that the way in which they arrive a political judgments at an onset of a crisis is perhaps more complex than the retrospective evaluation model assumes.

2. Data and methods

2.1. Data

To examine whether a government crisis response in another country can affect domestic incumbent support, we leverage the fact that the nationwide lockdown in Italy on 9 March 2020 happened during the fieldwork of the eupinions survey in four other European countries, France, Germany, Poland and Spain. Eupinions is an online survey that is repeatedly conducted in a set of different countries by Dalia Research on behalf of the Bertelsmann Foundation (see, www.eupinions.eu). For this study we were able to make use the surveys for France, Germany, Poland and SpainFootnote 2 that were conducted between 5 March and 25 March 2020 and comprised of a sample of 5303 respondents in total.Footnote 3 This allows us to compare the incumbent support of those who were interviewed before and after Italy's lockdown. The date respondents were interviewed serves as the variable Lockdown that assigns individuals to the treatment or control group. The variable Lockdown takes on a value of 0 for respondents who were interviewed before 9 March and a value of 1 for those interviewed after, which ends on 25 March when the fieldwork period of the surveys ended.

2.2. Case

Italy was one of the first countries outside China to witness a major COVID-19 outbreak. By the beginning of March 2020, the virus had spread to all regions of Italy, and the Italian government became the first government in Europe to impose restrictions to individual movements and public gatherings, a so-called “lockdown.” Although some villages in Lombardy and Veneto were quarantined late February already, starting on 8 March 2020, the region of Lombardy together with 14 additional northern and central provinces in Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna, Veneto and Marche, were put under lockdown. A day later, on 9 March the government extended the lockdown measures to the entire country.Footnote 4

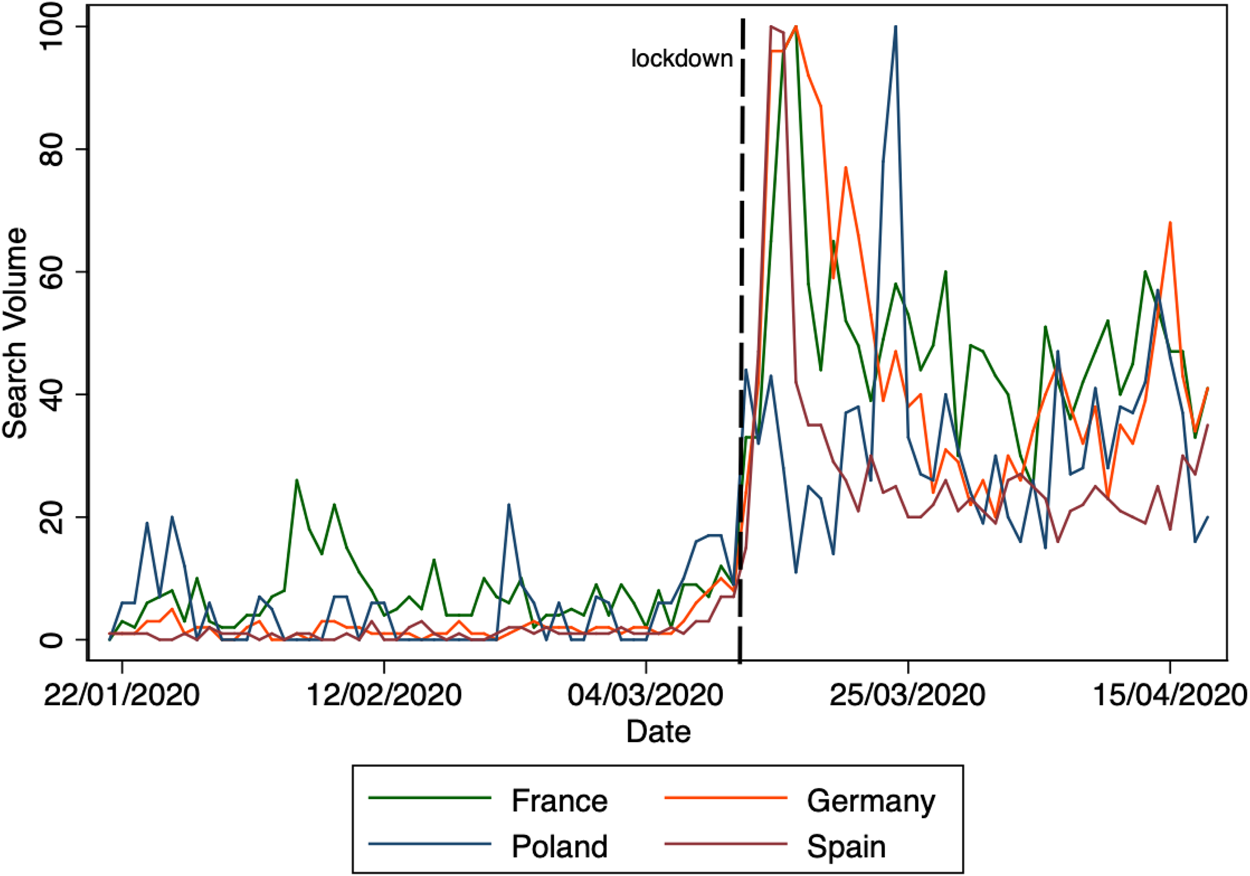

As the first major COVID-19 outbreak on European soil, the Italian situation was prominently covered by the news media across Europe. It signaled that COVID-19 severity and the speed of the unfolding situation in Italy signaled the coronavirus was likely to spread across the continent. To illustrate that the nationwide lockdown of Italy on 9 March was something that grabbed the attention of people across Europe, Figure 1 presents Google Trends data from France, Germany, Poland and Spain. Google Trends data provide an overview of the search volume of keywords used on the Google search engine. In order to make comparisons between search terms easier, each data point is divided by the total searches in a country on a given day and time range, and is then scaled on a range of 0–100 based on a topics proportion to all searches.Footnote 5 We provide overview of the Google searches for the word “lockdown” (in English or the national equivalent) for 90 days ranging from 22 January to 18 April 2020. The Google Trends data presented in Figure 1 clearly suggest that the searches for “lockdown” increased dramatically when the nation-wide lockdown in Italy was introduced. This suggests that the news about Italy's lockdown clearly reached French, German, Polish and Spanish citizens.

Figure 1. Google trends data in four countries for “lockdown” searches.

Note: This figure shows Google Trends data for the search term “Lockdown” in English or the national equivalent. Google Trends data give an overview of the search volume of keywords used on the Google search engine. In order to make comparisons between search terms easier, each data point is divided by the total searches in a country on a given day and time range, and is then scaled on a range of 0–100 based on a topics proportion to all searches. The dotted line signifies the date of the Italian lockdown.

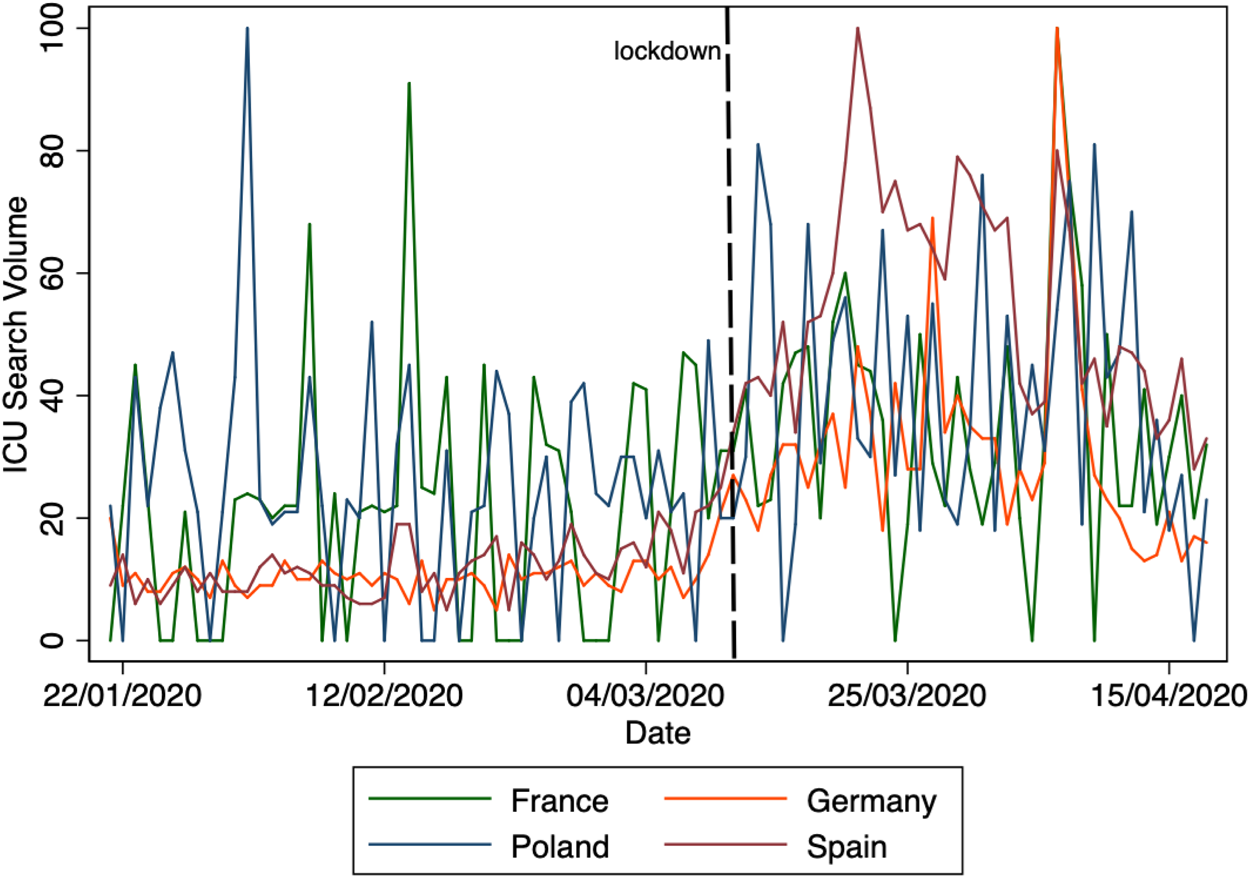

One of the most reported aspects of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy was the pressure on Italian hospitals and intensive care units (ICUs), in particular. We therefore examine whether citizens were gathering information on the capacity in hospitals and ICUs in their own countries. Interestingly, based again on Google Trends data, we find little evidence that French, German, Polish and Spanish citizens were actively searching for information about their country's preparedness for the pandemic when the nationwide lockdown in Italy was introduced. Figure 2 provides an overview of the Google searches for the term “Intensive Care Unit” (in the national equivalent) for 90 days from 22 January to 18 April 2020. As shown, there no clear temporal pattern in the searches for “Intensive Care Unit,” suggesting that while there was considerable interest in the Italian lockdown, it didn't make French, German, Polish and Spanish citizens actively search for information about their country's level of preparedness to a similar outbreak.

Figure 2. Google trends data in four countries for “intensive care unit” searches.

Note: This figure shows Google Trends data for the search term “Intensive Care Unit” in the national equivalent. Google Trends data an overview of the search volume of keywords used on the Google search engine. In order to make comparisons between search terms easier, each data point is divided by the total searches in a country on a given day and time range, and is then scaled on a range of 0–100 based on a topics proportion to all searches. The dotted line signifies the date of the Italian lockdown.

2.3. Variables and methods

We examine the effect of the nationwide lockdown in Italy on incumbent support in France, Germany, Poland and Spain. Incumbent support is captured by responses to the following question: Generally speaking do you consider yourself close to one of the following parties? This item is a question tapping into the attachment to political parties instead of vote intention. Attachment to political parties is relatively stable (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018) compared to vote intention which fluctuates quite a bit (Van der Meer et al., Reference Van der Meer, Van Elsas, Lubbe and Van der Brug2015; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Klemmensen, Nørgaard and Schumacher2016). This is the only item available in the eupinions survey tapping into people's preference for parties and can be seen as a rather conservative test of our hypothesis. On the basis of respondents’ answers to these questions, we constructed a variable Government Party Support that takes on a value of 1 if respondents state that they feel close to one of the parties in government and 0 if not. Except for Poland in which the government consists of one party (Law and Justice), all other countries in this study have coalition governments: Christian Democratic Union and Social Democratic Party in Germany, En Marche and Democratic Movement in France, and Social Democratic Party and Podemos in Spain. Note that this measure constitutes a rather conservative operationalization of incumbent support as it taps into closeness to government parties rather than an evaluation of their performance.

In addition, we construct two other variables of interest. First, PM Party Support that takes on a value of 1 if respondents state that they feel close to the party of the Prime Minister and 0 if not. Second, due to the recent rise of far right parties in Europe, we include an outcome variable capturing far right party support. Far Right Party Support takes on a value of 1 if respondents state that they feel close to the National Rally in France, the Alternative for Germany in Germany or VOX in Spain.Footnote 6

Finally, we include a set of socio-demographic controls: Gender (1 female, 0 male), Urban Residency (0 rural, 1 urban), Education (1 no formal education, some high school or secondary education; 2 completed high school, an equivalent diploma; 3 completed a university or equivalent degree), perceived Social Class (1 working class, 2 lower middle class, 3 upper middle class, 4 upper class) and Unemployment (0 employed, 1 unemployed).

2.4. Method

To test the crisis signal effect, we regress our Lockdown variable on Government Party Support. We estimate a linear probability model for the four different outcome variables using the equation below. Note, that we include survey weights in all subsequent analyses:

By relying on an event that occurred within the fieldwork of an existing survey, we leverage a so-called Unexpected Event during Surveys Design (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2018). This type of design relies on a core assumption, namely that the moment at which each respondent is interviewed during the fieldwork is independent from the time when the unexpected event occurs. This allows an as-if randomization to take place based on the occurrence of the event should.

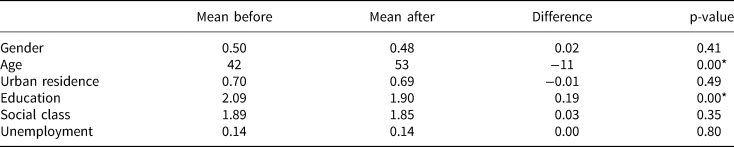

We test this assumption by means of balance tests, shown in Table 1 (further placebo tests are also shown in the “Results” section). We report the results from two-sided means difference tests on all socio-demographic variables that were included in the survey. These balance tests reveal that respondents interviewed before and after Italy's lockdown are very similar, except for a statistically significant difference in age and education. Respondents interviewed after the lockdown are likely to be older and less educated. This might not be entirely surprising given that it seems less difficult to reach younger and more educated respondents in an online survey, and therefore more likely to be interviewed earlier in the fieldwork period. In order to account for this potential selection effect, we add age and education as individual-level covariates to our regression analyses in addition to other individual level characteristics, such as gender, urban residence, social class and unemployment status. As can be seen below, the results do not change with our without these covariates.

Table 1. Balance tests

Note: 4815 respondents completed their surveys before the lockdown while 488 respondents after. * significant at the p<.05 level (two-tailed).

See Figure A6 in the online appendix for more information on days surveys were completed.

3. Results

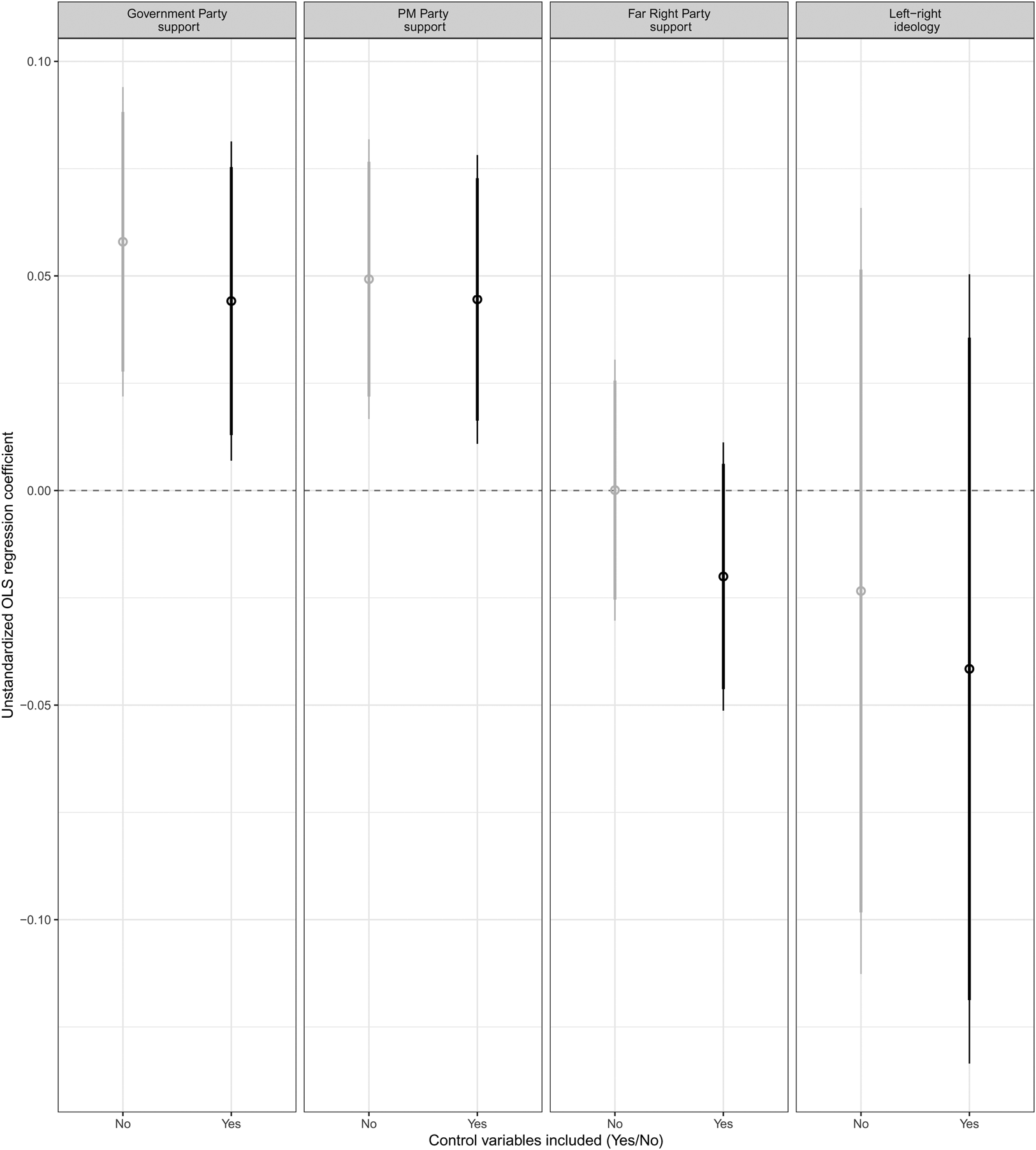

To test our argument, we turn to the results of regression analyses presented in Figure 3. In order to examine the effect of Italy's lockdown on incumbent support in France, Germany, Poland and Spain, we regress our Lockdown variable on our two measures of incumbent support, Government Party Support (most left-hand panel) and PM Party support (second panel on the left). In addition, we also examine if there is an effect of Italy's lockdown on support for far right parties (third panel from the left) as well as a placebo test for left-right ideology (most right-hand panel). We present the unstandardized regression coefficients of the effect of the Italian lockdown on our three dependent variables and our placebo test in models that include individual level covariates and country fixed effects (in black) and those that only include country fixed effects.

Figure 3. Effect of Italian lockdown on Government Party support, PM Party support, Far Right Party support and left-right ideology in France, Germany, Poland and Spain.

Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients of models with (black) and without (gray) controls. The dot is the point estimate and the thick bars are 90 percent confidence intervals and the thin bars are 95 percent confidence intervals. Full regression output belonging to all models can be found in the online appendix, Table A1 (models without controls), Table A.2 (models with controls) and robustness checks in Tables A2 and A3.

The results so far show that for respondents interviewed after Italy's lockdown there was a significant increase in support for government parties by 4.4 percentage point than those interviewed before the lockdown (b = 0.044, SE = 0.019, p = 0.020) and support for the prime minister party by 4.5 percentage point (b = 0.045, SE = 0.017, p = 0.010) controlling for the socio-economic background characteristics. These results lend support for the notion of a signal crisis effect of Italy's lockdown, as support for the incumbent increased in other European countries after the lockdown.

Importantly, when we inspect the results reported in the third column from the left in Figure 3, there does not seem to be an effect of Italy's lockdown on the support for far right parties ($b = -0.022,\; {\rm SE} = 0.016,\; {\rm p} = 0.176$![]() ). This lends further credence to the idea of crisis signaling effect. The decision of the Italian government to implement a nationwide lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak alerted citizens in other European countries about an imminent and severe crisis that could hit their countries as well. As a result of this, incumbent support in these other countries should rise, not necessarily support for the far right that run on platforms criticizing the government.

). This lends further credence to the idea of crisis signaling effect. The decision of the Italian government to implement a nationwide lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak alerted citizens in other European countries about an imminent and severe crisis that could hit their countries as well. As a result of this, incumbent support in these other countries should rise, not necessarily support for the far right that run on platforms criticizing the government.

The results presented so far remain robust when additional tests are performed. First, the results remain robust against different model specifications, for more information see Section A.2 in the online appendix. We have restricted the sample to one-week after the lockdown (Figure A1), controlled for the number of COVID-19 deaths and confirmed cases at the time the participant completed the survey (Figure A3), performed logistic regression models which account for the binary nature of the dependent variable (Table A3) and excluding the survey-weights (Figure A4).

Second, recent study has shown that national governments become more popular after imposing a lockdown (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Damien Bol, Giani and Loewen2020; Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee, Milojev, Bulbulia, Osborne, Milfont, Houkamau, Duck, Vickers-Jones and Barlow2020). One might be worried that our estimates are biased by the domestic lockdown effects. To examine this we limit our sample to participants who are only “treated” by the Italian lockdown—that is, we only include people up to the day before a lockdown was announced in their country. We re-ran part of our analysis by restricting our sample to the day before the country of the survey respondent went into lockdown.Footnote 7 As can be seen in Figure 4, the results are basically unaffected by this robustness check.

Figure 4. Effect of Italian Lockdown on Government Party support, PM Party support, Far Right Party support and left-right ideology in France, Germany, Poland and Spain, sample is restricted to the day before national lockdown.

Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients of models with (black) and without (gray) controls. The dot is the point estimate and the thick bars are 90 percent confidence intervals and the thin bars are 95 percent confidence intervals. Full regression output belonging to all models can be derived from the replication files.

Third, we performed a set of placebo tests. The results presented so far support our intuition that the nationwide lockdown introduced by the Italian government acted as a signal for citizens in other European countries about an imminent and severe crisis that could hit their countries as well and rallied them around their government. This would also suggest that Italy's lockdown should not affect other outcomes related to politics that are usually considered to be more stable, such as a person's ideology. We test this by replicating the initial analysis but now using a different outcome variable, namely a respondent's self-reported ideology on a left-right scale (coded as 1 left, 2 center left, 3 center right, 4 right). The results presented in the right-hand column of Figure 3 and suggest that Italy's lockdown did not affect the ideological self-placement of respondents ($b = 0.048,\; {\rm SE} = 0.047,\; {\rm p} = 0.301$![]() ).

).

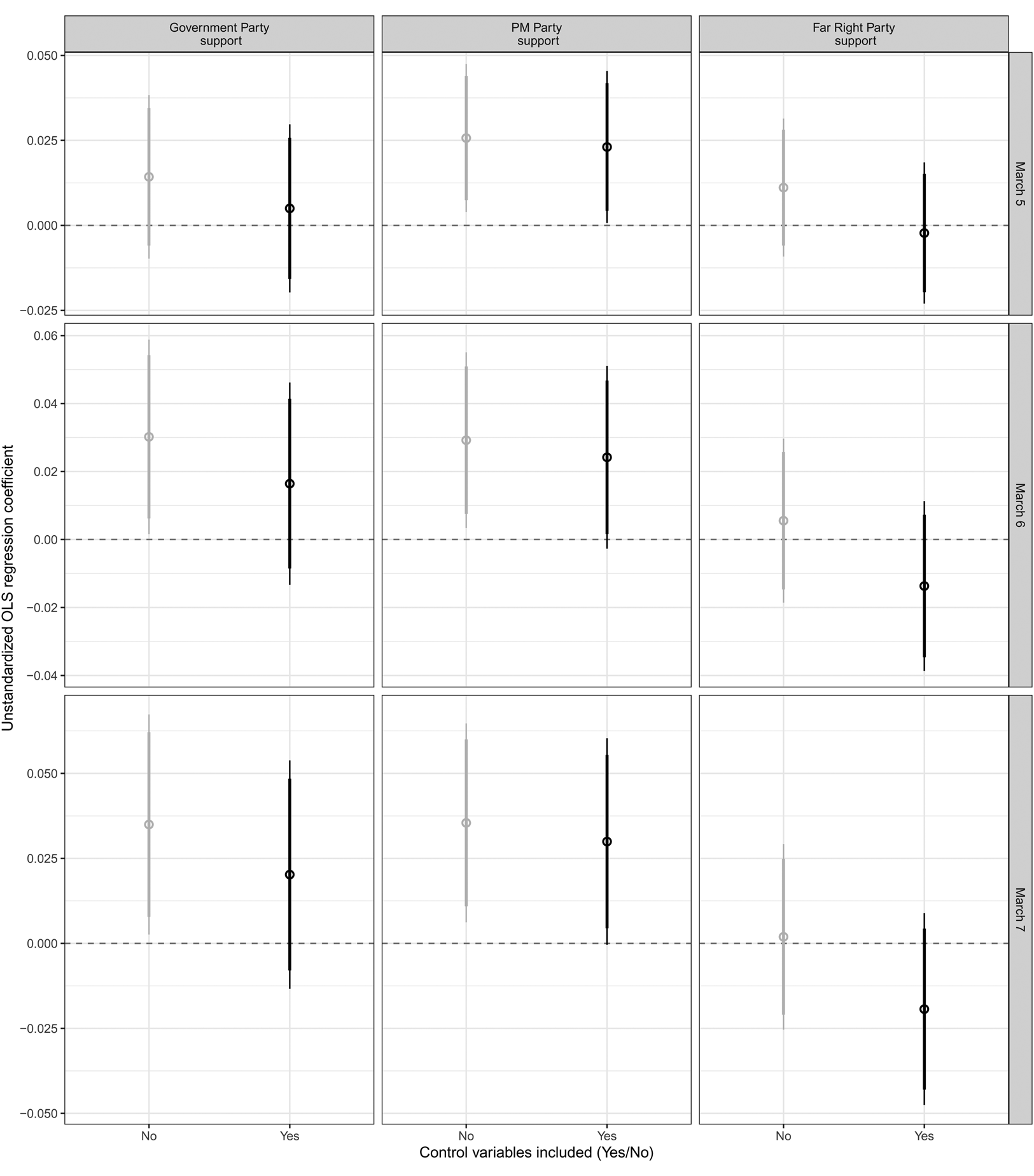

We also conduct placebo tests and randomly select other dates in the fieldwork period as cut-off points to create a placebo treatment variable (responses at 5 March 6 March or earlier and 7 March or earlier) (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2018). Respondents interviewed before the placebo dates are assigned to the placebo control group, while those that were interviewed after are assigned to the placebo treatment group. The results of the placebo tests presented in Figure 5 reveal that there are no statistically significant differences between those interviewed before or after the randomly chosen dates exist for government party or far right party support when we set the placebo treatment to 5 March (top panels of Figure 5), 6 March (middle panels of Figure 5) or 7 March (bottom panels of Figure 3). Yet, we do find effects for prime minister party support. Prime minister party support rose already prior to the introduction of the lockdown in Italy as can be seen by the positive and—marginally—significant effects of the placebo treatments on 5 March (top panel of the middle column of Figure 5), 6 March (middle panel of the middle column of Figure 5) and 7 March (bottom panel of the middle column of Figure 5) on prime minister party support. This might indicate that the effect of the unfolding COVID-19 crisis, as reported through the media, had already begun to create a rally around the leader (PM) bump that was then transferred to the rest of the governing parties once Italy put in place the lockdown order.

Figure 5. Placebo tests of effect of Italian lockdown on Government Party support, PM Party support, Far Right Party support and left-right ideology in France, Germany, Poland and Spain.

Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients of models with (black) and without (gray) controls. The dot is the point estimate and the thick bars are 90 percent confidence intervals and the thin bars are 95 percent confidence intervals. Full regression results belonging to all models can be derived from the replication files.

3.1. Discussion

Our empirical results show that incumbent support in other European countries increased after Italy's COVID-19 lockdown, even before domestic governments had responded with similar measures. What might be the reason for the increase in government approval? Although the nature of the data presented in this paper does not allow us to isolate the precisely determine mechanism through which the crisis signaling effect happens, in this section we wish to reflect on the potential channels.

In line with the classic retrospective voting model, pandemics as natural disasters can inform voters about the level of preparedness of the governments regarding these disaster (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, de Mesquita and Friedenberg2018). In the case of the coronavirus pandemic, as French, German, Polish and Spanish citizens learned that another European country (Italy) was badly affected by COVID-19, they may have inferred that their government was better prepared as they had not yet suffered the same fate. This could explain the initial rallying around national governments. Our analysis of Google Trends data reported in Figure 2, however, provided limited evidence to support the suggestion that voters responded to the Italian lockdown by actively getting informed about their country's level of preparedness. What is more, an implication of idea that people used the Italian lockdown as signal of their country being better prepared, would be that as this these countries became severely affected by the virus a few weeks later (e.g., France and Spain), incumbent approval should drop sharply as performance perceptions are updated. Yet, this does not seem to have been the case as incumbent approval generally increased during the early phase of domestic lockdown across Europe.Footnote 8

Using the Italian lockdown to make inferences about pandemic preparedness in your own country also requires a degree of sophistication among citizens. To explore whether political sophisticates reacted differently to the external event, we therefore examined heterogeneous effects in responses to the Italian lockdown based on sophistication, see Figure 6. Political sophistication has often been theorized as a factor determining more or less responsive to new information (Arceneaux, Reference Arceneaux2008; Kahan et al., Reference Kahan, Peters, Dawson and Slovic2013). The idea is that sophistication makes people more attuned to information and in this case should make them more responsive to the lockdown.Footnote 9 The only proxy of political sophistication that is available in our survey data is education, which is often used as a measure of political sophistication. We plot in Figure 6 the average marginal effect of the lockdown (1 post lockdown; 0 before lockdown) on the four dependent variables among those less than high school, high school or university education. As can be seen in the four panels, there is no consistent evidence that the effects of the lockdown are conditional upon the level of education. Given that making inferences about government preparedness on the basis of information about events in another country seems quite demanding, we would have expected to find some differences across respondents based on their level of education if this were the mechanism through which the crisis signaling effect worked.

Figure 6. Average marginal effect of Italian lockdown on Government Party support, PM Party support, Far Right Party support and left-right ideology in France, Germany, Poland and Spain over the range of education.

Note: average marginal effect of lockdown on the dependent variable. The dot is the average marginal effect and the thick bars are 95 percent confidence intervals. Full regression output can be derived from the replication files.

Another channel that could account for our findings focuses on how exogenous events can create emotional responses that carry over to influence political outcomes (e.g., Small et al., Reference Small, Lerner and Fischhoff2006; Healy et al., Reference Healy, Kuo and Malhotra2010). There are various ways in which the Italian lockdown may have also shaped emotions and political opinion outside Italy. One possibility is that the lockdown made some people in other countries feel positive emotions, perhaps out of hope that it would limit the spread of the disease or out of a sense of relief that somebody somewhere was doing something (Egan, Reference Egan2014).

Another possibility is that the Italian lockdown laid bare the severity of the crisis and the likelihood that it would soon spread to other European countries, which increased people's anxiety. In times of crisis, anxiety tends to increase trust in government and incumbent politicians (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Schott and Scherer2011; Albertson and Gadarian, Reference Albertson and Gadarian2015). Indeed, some scholars posit that anxiety and a need for security drives the rally-round-the-flag effect often observed in the face of foreign threats (e.g., Pyszczynski et al., Reference Pyszczynski, Solomon and Greenberg2003). Although the COVID-19 pandemic is not exactly the type of military threat that lies at the center for rally-round-the-flag effects, it shares features with foreign threats. It spreads across internal borders, it threatens people's lives, and it requires personal sacrifices to confront. The question of whether people responded to the lockdown with positive emotions or anxiety (or indeed a heterogeneous response) opens up new avenues for future research to explore the emotional responses to the crisis, and how they translate into political opinions and behaviors and the pandemic unfolds.

When it comes to our placebo tests, the results for government party support was more robust compared to the prime minister support. This might mean that the effect of the unfolding crisis, as reported through the media, had already begun to create a rally-around-the-leader (PM) effect that was then transferred to government parties when Italy put in place the lockdown order. This perhaps indicates that our treatment is fuzzy. As we can see in Figure 1, some citizens of France, Germany, Poland and Spain were already—but to lesser extent—searching for the word lockdown on the internet prior to 9 March albeit to a much lesser extent that after the lockdown was introduced. Our treatment, the introduction of the lockdown, is of course not exogenous to how the COVID-19 outbreak unfolded in Italy. So, how developments abroad affect incumbent support in other contexts during an unfolding crisis is an interesting topic for further research.

4. Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated that incumbent support in other European countries increased after Italy's COVID-19 lockdown, even before domestic governments had responded with similar measures. These results are robust against different model specifications and placebo tests. This evidence illustrates the importance of how developments abroad can affect incumbent approval at home (Kayser and Peress, Reference Kayser and Peress2012; Campello and Zucco Jr, Reference Campello and Zucco2020). Our findings thus have implications for the study of electoral accountability more generally. They suggest that the electorate can be swayed to support the incumbent by developments abroad, not necessarily confined to the economic realm. The results also suggest that models of incumbent support should not only place importance on domestic performance-based indicators, or evaluations thereof, but should consider a broader range of international developments that may shape people's allegiance to incumbent parties. Our findings open up important new avenues for future research to explore the emotional responses to the coronavirus, and how they translate into political opinions and behaviors as the pandemic unfolds.

Whatever the precise mechanisms, our findings inform the literature on performance voting (e.g., Kramer, Reference Kramer1971; Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981), competence misattribution (e.g., Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Healy et al., Reference Healy, Kuo and Malhotra2010). Our results suggest that a boost to incumbent support in response to quickly developing crises can be unrelated to changes in performance domestically. In line with recent study on the effects of commodity or remittances shocks (Tertchayna et al., Reference Tertchayna, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018; Campello and Zucco Jr, Reference Campello and Zucco2020), our findings cast some doubt on the notion that ordinary citizens can always disentangle performance signals from exogenous shocks at the outset of a crisis.

Does this suggest that incumbents will enjoy a sustained boost to their approval ratings throughout the COVID-19 crisis? Not necessarily. As the crisis has become more embedded in domestic politics and crisis response, performance of the incumbent will start to matter more. Just as we have seen in relation to natural disasters, when governments are often blamed, and held to account, for their inadequate disaster responses (e.g., Malhotra and Kuo, Reference Malhotra and Kuo2008). In the case of a pandemic lasting for months or even years, voters are likely to monitor their government's crisis handling closely. If so, we expect that governments that handle the COVID-19 crisis well will enjoy a continued boost to their popularity, while those that do not will experience a decline in support.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.6.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: CdV; SBH; KA; BNB; resources: CdV; formal analysis: CdV, BNB; visualization: CdV, BNB; validation: BNB; writing original draft: CdV; writing, review and editing: KA; SBH; BNB.