I. Introduction

In this article, we put forward an agency-oriented constructivist approach to interface conflicts that emphasises how international actors articulate and problematise norm collisions in discursive and social interactions. We understand norm collisions as situations in which actors perceive at least two norms as incompatible with each other. They express a potentially productive struggle over norms and their relations with each other. We propose studying how norm collisions emerge and not only how they are eventually managed once actors bring them to court or quasi-legal authorities. Tracing and explaining how and why collisions have emerged in the first place, we therefore complement approaches in International Relations (IR) and International Law (IL) whose predominant interest lies in identifying appropriate mechanisms or legal principles to resolve problematic collisions. Empirical research on norm collisions in international politics has typically focused on such cases of colliding norms that state actors found intolerable to such an extent that they took legal action (Wisken Reference Wisken2018; Pauwelyn Reference Pauwelyn2003). Instead, we enlarge the range of fora in which we expect actors to address norm collisions by articulating the incompatibility between two or more social expectations. By taking into account collisions between legal and non-legal norms, we also suggest going beyond the narrow focus on codified international law in the study of norm collisions.

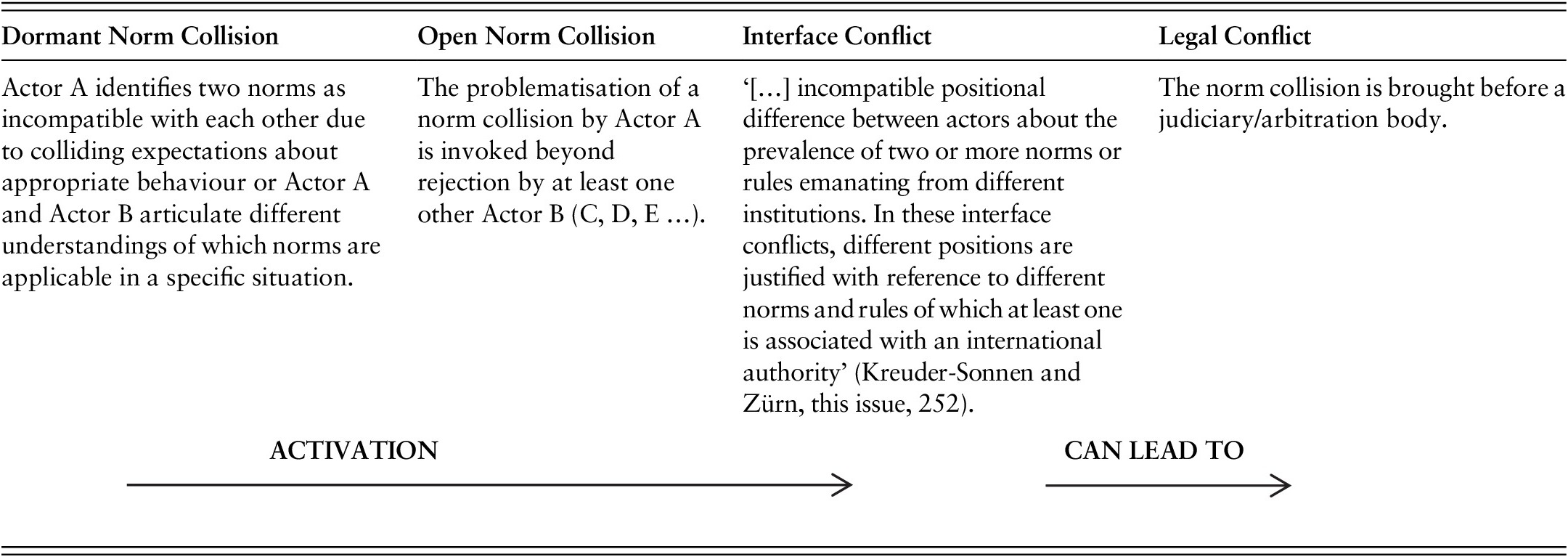

Our argument is threefold. First, we claim that agency matters to the analysis of the emergence, dynamics, management, and effects of norm collisions in international politics. Whereas norm collisions have been largely treated as incompatibilities between codified international standards in IL, we conceptualise them as discursively expressed social expectations. We thereby shift the focus to their relevance in those social interactions in which actors articulate a concern about incompatible behavioural expectations between two or more norms. In order to become observable, norm collisions need to be articulated, i.e. brought to the fore by actors who claim that they are problematic. This is not to say that incompatibilities between the social expectations enshrined in norms are not – hypothetically – ubiquitous, or that the trajectories of norm collisions – once articulated – evolve in a predetermined manner. To be precise: while we propose sensitivity to agency when studying norm collisions, we by no means deny that norms have a structural quality. Second, we propose to differentiate between dormant and open norm collisions, which is essentially a differentiation between individual articulations of colliding behavioural prescriptions (dormant norm collision) and intersubjective exchange and argumentation by several actors which makes a collision relevant and socially consequential (open norm collision).

Third, we contend that the activation of an intersubjective problematisation of incompatible norms depends on the existence of certain scope conditions. Ultimately our article puts forward a number of propositions concerning the conditions that enable different agents to bring norm collisions to the fore and, thus, to turn dormant collisions into open ones. Open norm collisions may lead to interface conflicts when at least one of the colliding norms is associated with an international authority and when actors express them in positional differences (Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn, this issue). We analyse the possible development from dormant norm collisions to an open norm collision to interface conflicts both theoretically and empirically. Two larger questions motivate our article: Under which conditions, and how, do actors activate norm collisions and interface conflicts? We examine these questions by engaging with the literature on regime complexity, legal fragmentation, and norm contestation.

Our article is structured as follows. Section II presents our conceptual framework based on the constructivist agency-oriented understanding of norm collisions we embrace. Section III elaborates on our methodological framework, illuminating how we identify dormant and open norm collisions as well as interface conflicts. Section IV analyses norm collisions in the issue area of international drug control. Here we empirically illustrate our argument discussing the specific and very contentious case of coca leaf chewing. Using this case, we probe the plausibility of scope conditions for the activation of norm collisions and interface conflicts. Section V offers a conclusive summary and an outlook on future research.

II. An agency-oriented constructivist approach to interface conflicts

Our agency-oriented approach to interface conflicts focuses on norm collisions, i.e. situations in which actors perceive two or more norms to be incompatible with each other. Hence, we focus on perceived normative inconsistencies and ask how and under which conditions actors are able to articulate and problematise norm collisions in international fora. We thus rely on agency when seeking to explain norm collisions in discursive and social practices. The second part of our article, however, serves to identify the structural conditions that enable such practices in the first place. In the following, we provide, first, a discussion of the relevant literature and, second, definitions of norms and norm collisions.

Norm collisions in scholarship on regime complexity, fragmentation, and contestation

Three research traditions at the intersection between IR and IL are relevant for our approach: the literature on regime complexity; the literature on legal fragmentation; and newer literature on norm contestation. As the Introduction to this Special Issue has already addressed theories on regime complexity and legal fragmentation, we discuss these research strands only with a particular focus on how we seek to extend and transcend them.

Theories on regime complexity have pointed to the increasing likelihood of institutional and regime overlaps as one cause of interface conflicts and resulting norm collisions (Aggarwal Reference Aggarwal1998; Young Reference Young2002). Studies on regime complexity have shifted their focus to the consequences of regime complexity (Gómez-Mera Reference Gómez-Mera2016; Oberthür and Stokke Reference Oberthür and Stokke2001; Orsini et al. Reference Orsini, Morin and Young2013) – and in particular to the numerous interface conflicts that may result from overlaps between international institutions (see Faude and Fuß, this issue). While the regime complexity literature has mainly focused on the origins and effects of overlapping rule-systems and organisational mandates and resulting incompatibilities between norms and rules, contemporary international legal scholarship is replete with theoretical discussions of and empirical studies on norm collisions, with a particular focus on how such collisions should be dealt with (de Sousa Santos Reference De Sousa Santos1995: 14; Koskenniemi Reference Koskenniemi2009; Günther Reference Günther2008). Scholars either adhere to a legal positivist tradition which advocates for a unitary perspective (Borgen Reference Borgen2005) or embrace a sociological theory of law that promotes a pluralist perspective, thereby accepting norm collisions as an inevitable characteristic of international law (Günther Reference Günther2008; Fischer-Lescano and Teubner Reference Fischer-Lescano and Teubner2003; Twining Reference Twining2010).

Theories on regime complexity and legal fragmentation leave no doubt that interface conflicts are a recurrent feature of international cooperation and that they often result in protracted conflicts over the validity and compatibility of norms. These theories provide analytical tools for situations in which multiple norms matter. However, while they provide us with insights into how actors and institutions respond to norm collisions – and thus emphasise agency and choice in the way norm collisions are dealt with – the question of who brings these collisions to the fore, under which conditions, and in what context remains unanswered.

While we tie in with these emerging research programmes, we build on the ontological assumption that norms, while in principle stabilising expectations and structuring behaviour, do not themselves possess a stable meaning (Wiener Reference Wiener2009; Krook and True Reference Krook and True2012). Critical constructivist norm research provides important insights on norms as processes and puts forward a stronger focus on agency (Niemann and Schillinger Reference Niemann and Schillinger2017). This is fruitful for us because it allows us to analytically privilege actors’ articulations when studying incompatibilities between normative prescriptions. How do actors ‘construct’ norm collisions and frame them as problematic in their social and discursive interactions?

We build on some of the core theoretical propositions of the critical constructivist norm debate, including the norm contestation literature, but we also extend it in two crucial aspects. Firstly, by studying norm collisions, we suggest looking at dynamic relationships between norms stemming from different spheres of authority rather than zooming in on a single norm and how it is interpreted. Both theoretically and empirically, the contestation literature has focused so far on single norms, for example, the ban on commercial whaling or the Responsibility to Protect (Welsh Reference Welsh2013; Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020: 70). Similarly, much of the constructivist norm literature deals only with the dynamic nature of a single norm, in the form of emergence, change, or death of one particular norm (Labonte Reference Labonte, Bellamy and Dunne2016). Secondly, while contemporary research on norms with its focus on translation (Merry Reference Merry2006; Berger Reference Berger2017) and localisation (Acharya Reference Acharya2011; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2017) typically studies vertical interface conflicts (i.e. collisions between international and domestic rules; Cloward Reference Cloward2016), we look at norm collisions and interface conflicts predominantly at the horizontal level, although our case study also has a vertical dimension (for this distinction, see Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn, this issue). Our contribution, therefore, offers an agency-based perspective on the dynamic relationships between different norms at the global (and regional) level.

Norms

Classically, constructivists have defined norms as ‘collective expectations for the proper behaviour of actors with a given identity’ (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein and Katzenstein1996: 5). Following newer work (Winston Reference Winston2018), we define norms as value-based collective expectations for the appropriate behaviour of governments and states in specific types of situations. Footnote 1 In line with the work of critical constructivist scholars, we hold that a norm’s meaning can change over time and that actors can contest both a norm’s meaning and its application. Norms may also have different meanings depending on the situation in which actors invoke them (Krook and True Reference Krook and True2012; Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020; Wiener Reference Wiener2018). Here it is important to stress the context-sensitive nature of the definition of norms we put forward, assuming that the specific situation in which we look at norms, norm collisions, and interface conflicts matters greatly for the analysis we conduct. Linked to this is the assumption that norms are in our understanding always discussed – implicitly and explicitly – with reference to other norms.

In our perspective, actors invoke both legal and non-legal norms when discussing the applicability and boundaries of a specific norm in a specific situation. Acknowledging the widely used distinction between non-legal and legal norms (Brunnée and Toope Reference Brunnée and Toope2010: 350; Finnemore and Toope Reference Finnemore and Toope2001: 746–51; Weiner Reference Weiner1998: 434), we conceptualise legal norms as those norms that come with a legal obligation to comply, irrespective of their degree of precision. As we will show below in the case study, actors have for a long time referred to non-legal norms referring to indigenous practices when seeking to eliminate the prohibition of coca consumption from the 1961 Single Convention. These efforts gained further momentum with the legalisation of indigenous rights in the context of the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) and the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention C169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO). As regards their legal quality it has to be acknowledged that they both contain rather unspecified prescriptions and the latter can be considered to be legally binding mainly in Latin America.

Norm collisions and interface conflicts

We define norm collisions as instances in which actors claim that two or more norms provide conflicting or incompatible expectations about appropriate behaviour in a specific situation. It is essential to add that a norm collision can either take place between two norms that had existed before they were perceived to be colliding, between two newly emerged norms that had hitherto not been related to each other, or between an already existing and a newly emerged norm. We hold that while there are theoretically many norm collisions in global politics, they mainly matter when actors articulate them as such and bring them to the fore in the context of international cooperation. We distinguish between subjective and therefore singular articulations of colliding behavioural prescriptions (dormant norm collision) and intersubjective exchange and argumentation by several actors who perceive a collision to be relevant and socially consequential (open norm collision). Consequently, we understand the activation of a norm collision as an intersubjective process whereby actor A’s claim that two behavioural prescriptions are incompatible is seized by at least one other actor B.

Our argument that norm collisions are activated does also not imply that actors can construct any collision they like or freely determine the meaning of norms. Our starting point is a discomfort with the rather structural perspective that other scholars embrace in their analysis of norm or regime collisions. They often treat norms as a fact, i.e. something ‘given’ (see also Niemann and Schillinger Reference Niemann and Schillinger2017). It is not our interest to fall into the opposite extreme, but rather to take a certain level of agency seriously. In a nutshell, we neither argue that norms are stable and have a determined and fixed meaning, nor do we uphold that their meaning is entirely contingent. As our examples below show, the core of a norm often remains uncontested for quite a while and will most likely not be affected by actors’ articulations. Despite behavioural and discourse contestation, international norms such as those on drug control, the ban on commercial whaling or the prohibition of child labour would cease to exist if they were not grounded in a consensus on the necessity to preserve whale stocks, protect children from exploitation and societies from harmful drug use. However, as our own study and the studies of others (Bourdillon et al. Reference Bourdillon, Levison, Myers and White2010; Epstein Reference Epstein2008) have shown, interpretations of the breadth and depth of these norms have transformed considerably over time with regard to their referent objects ‘child labour’, ‘whaling’, and ‘drugs’.Footnote 2 Currently, the supposedly ‘shared’ consensus on these norms seems to be crumbling: several states, international organisations (IOs), and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) contest the idea that cannabis or coca are essentially harmful drugs while alcohol is not. Thus, interpretations of the exact referent object (i.e. who counts as a child; what counts as a harmful drug) and interpretations of the appropriate behavioural prescriptions (e.g. which forms of whaling to prohibit) change over time. Even where discursive and behavioural contestation as well as decreased efforts to shame non-compliance eventually weaken a norm, such as in the case of the ban on commercial whaling (Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2020: 70), we argue that the core value of these norms, i.e. the expectation to preserve whale stocks or to protect children, still structures the identity, interests, and discourse of actors (see also Lantis and Wunderlich Reference Lantis and Wunderlich2018: 576).

Based on this reasoning, our agency-oriented approach to norm collisions rests on the observation that actors have always actively challenged the given status quo of international norms and, thereby, negotiate the margins of these norms. We follow Hofferberth and Weber (Reference Hofferberth and Weber2015: 85) in their understanding of norms as ‘points of orientation and reference’ with which actors ‘make sense of indeterminate situations’. How these are applied depends on agents’ context-specific interpretation of certain elements of norms. By analogy, we assume that actors articulate norm collisions when a) their expectations towards norms or reference objects have changed (e.g. when they began to see children not only as objects of protection but also as social, political and economic agents), b) they seize the opportunity to change norms that they never internalised (e.g. Japan and the commercial whaling ban), c) when existing norm hierarchies are challenged, or d) when they deal with new cases of norm application (e.g. women’s rights in the private sphere).

The Special Issue is especially interested in those norm collisions that denote interface conflicts as those collisions in which at least one of the colliding norms is associated with an international authority (Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn, this issue). We, therefore, study how open norm collisions evolve into interface conflicts. Table 1 summarises our conceptualisation of dormant and open norm collisions, and interface conflicts, as covered in this article. We do not consider the potential next step, namely when an interface conflict is brought before a court or court-like institution (for legal conflicts see Birkenkötter, this issue; for the role of interface conflicts as a pathway to change in international law, see Krisch et al., this issue).

Table 1 Activation of norm collisions

Source: Authors

The following section provides the methodological framework for the identification of norm collisions (both dormant and open) and interface conflicts.

III. Identifying norm collisions and interface conflicts

In this section, we outline how we identify norm collisions and interface conflicts by studying discursive interactions in the international realm. Building on the ontological assumption that there is a close relationship between language and the construction of social reality, we turn to discourses as the space where social reality manifests itself (Doty Reference Doty1993: 302; Milliken Reference Milliken1999). Understanding discourse as ‘the space where human beings make sense of the material world, where they attach meaning to the world and where representations of the world become manifest‘ (Holzscheiter Reference Holzscheiter2014: 144), it is both constitutive of and constituted by social interaction – it is ‘text in context’ (van Dijk Reference Van Dijk and van Dijk1997: 3) or ‘meaning-in-use’ (Wiener Reference Wiener2018: 54). Such a co-constitutional understanding necessitates analysing discourse as communicative action on the micro-interactional level (text, in-use) and the macro-structural level that foregrounds and gives meaning to such action (context, meaning) (Fairclough and Wodak Reference Fairclough, Wodak and Dijk1997: 258). On the micro-level, we focus on individual speech acts on norms by actors voiced within various fora such as international organisations. On the macro-level, we analyse discourse as a structural context, where debates on norms and normative expectations take place. In order to study norm collisions and interface conflicts, we first have to identify them in discursive practices. Second, we need tools to analyse how actors activate them. Here we study how a dormant norm collision turns into an open one. We discuss these two requirements in the remainder of this section.

How do we identify a dormant norm collision in discursive practice? Our operationalisation rests on three elements: First, an actor must invoke at least two norms. Second, an actor must identify both norms as applicable to the specific situation or practice. Third, s/he must problematise that the two norms are incompatible with each other, as, for example, norm A prescribes a certain course of action that would interfere with norm B. How do we identify an open norm collision and thus its activation? To turn a dormant norm collision into an open one, at least one other actor has to follow the first actor’s problematisation of a norm collision. For the identification of an open norm collision, the observation of intertextuality, i.e. links between different actors’ articulations and often also between different documents, is central.Footnote 3 Intertextuality reflects the transformation from a subjective claim to an intersubjective exchange.

Following the Introduction to this Special Issue, for the norm collision to denote an interface conflict, we must find speech acts pointing to positional differences, in which at least one of the colliding norms must be associated with an international authority. The interaction between our two (or more) actors may take place within the same or in two different fora. As norm collisions and interface conflicts unfold over time, it is important for us to trace their development over more extended periods, zooming in on moments of social interactions.

In this article, we centre on IOs as the primary site for interface conflicts, where plural identities and memberships intersect and are potentially at odds. IOs are not only seen as the main platforms for cooperation and coordination between state (and increasingly also non-state) actors but also as the most relevant and authoritative fora in which to assess the validity of existing international standards.

In terms of research methods and data, we use a discourse analytical framework that integrates both interpretivist and quantitative, computer-assisted text analysis. We have applied lexical analysis tools available in MAXQDA to assess all International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) reports between 1968 and 2015, meeting records for all three Conventions, relevant Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) resolutions, all reports of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), and all official records concerning Bolivia’s attempt to amend the Single Convention. Furthermore, we analyse selected documents of relevant IOs, such as the International Labour Organization, the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights or the UN General Assembly Special Sessions on International Drug Control in 1998 and 2016. Our analysis also includes reports by NGOs such as the Transnational Institute. We also close-read key documents identified through lexical search and through reference in the secondary literature on the issue area. The lexical searches focuses on words indicating incompatibility between norms, i.e. violat*, incompatib*, inconsisten*, clash*, colli*, discriminat*. Such a well-established approach allows us to cover a large body of documents whilst retaining the ability to work inductively and interpretatively (Bennett Reference Bennett2015) and ensures that we do not miss relevant traces of the norm collision we are interested in.

We now turn to the issue area of international drug control to illustrate our argument and to empirically trace the development from dormant to open norm collision to interface conflicts. In addition, we analyse the conditions that enable this transformation.

III. Norm collisions and interface conflicts in international drug control

We begin by mapping the issue area of international drug control to demonstrate the existence of several dormant norm collisions. For this, we rely on both our own analysis and secondary literature. We then analyse the activation of a norm collision using the case of the collision between the prohibition of coca leaf chewing (based on the prohibition of the coca leaf as a drug, according to Articles 2(1) and 4(c) of the 1961 Single ConventionFootnote 4) and indigenous rights protecting indigenous practices and cultural heritage (codified in Articles 11, 24, and 31 of UNDRIP). Here, two norms, the prohibition of drug use on the one hand and the protection of indigenous rights, on the other hand, are brought into collision with each other over the practice of coca leaf chewing. In the last part of this section, we seek to provide answers to the second question motivating our article: under which conditions do norm collisions come to the fore and even turn into interface conflicts?

Mapping the Field

International drug control has been, from the onset, characterised as a ‘prohibition regime’ (Nadelmann Reference Nadelmann1990); its core norms deal with the criminalisation and prohibition of drugs except when used for medical or scientific purposes. The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs as amended by the 1972 protocol, the 1971 Conventions on Psychotropic Substances, and the 1988 Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances constitute the core building blocks of the regime. The 1961 Convention establishes three international authorities: The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), whose role is to oversee the implementation of all three conventions; The Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), whose role is that of policymaking; and the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crimes (UNODC), which serves as the secretariat, providing technical and administrative support (Bewley-Taylor Reference Bewley-Taylor2004: 484). Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) is mandated to assess which substances qualify as drugs and are thus regulated under the Single Convention.

The literature portrays the prohibition approach as one with a high degree of consensus on criminalisation among states (Jelsma Reference Jelsma2003: 193). This consensus results in a marginalisation of norms protecting individual or public health, often leading to tensions between drug control and human rights protection (Lines Reference Lines2017: Ch 4; Barrett and Nowak Reference Barrett, Nowak, Constantinides and Zaikos2009; Barrett Reference Barrett2010). However, scholars have also noted that this consensus has recently started to disintegrate (e.g. Bewley-Taylor Reference Bewley-Taylor2012). Against this backdrop, it seems plausible to assume that this disintegration opens up possibilities for actors to articulate norm collisions. In fact, a number of dormant norm collisions have been perceived by state and non-state actors in the international drug prohibition regime for considerable time – and yet, only recently have these collisions been openly debated and thereby activated. Based on our analysis of several dormant norm collisions in the area of drug control, we go on to ask: why has a specific dormant collision turned into an open norm collision and ultimately an interface conflict? To this end, we probe our empirical material, demonstrating that in the specific case of a norm collision concerning the practice of coca leaf chewing certain structural and agent-level conditions facilitated the activation of norm collisions. On the structural level, we relate to the quality of norms and changing power structures. We can show, for example, that the degree of obligation and precision of the relevant norms in the collision increased over time, which in turn facilitated the activation of a norm collision. On the level of actors, our case illustrates the effect of changing actor constellations and the decisive role of state coalitions, but we find no discernible influence of advocacy coalitions in the stricter sense of the term.

Early debates about the role of human rights norms in international drug control provide a good example for dormant norm collisions (Bruun et al. Reference Bruun, Pan and Rexed1975: 42). We find references to human rights norms by individual actors as early as 1961. The representative of Uruguay, Mr. Fabregat, for example, called for the inclusion of human rights in the Convention (United Nations 1961b: 113). And the representative of the Holy See, Monsignor Flynn, included a call for respect for human rights when dealing with drug addicts (United Nations 1961b: 197). These examples demonstrate that even then actors perceived human rights norms as relevant for international drug control and that there was a potential for norm collisions. These references to human rights norms, however, did not turn into open norm collisions because references to these norms by individual actors were not seized by other actors during these or other debates, and thus did not trigger deliberations on the potential (in)compatibility between global drug policies and human rights norms. Furthermore, these calls did not lead to an inclusion of human rights norms in both the 1961 and 1971 Conventions. We interpret these developments as indicating a dormant norm collision. Obviously, the process of codifying human rights norms was in full swing long before the post-World War II Conventions on drug control emerged. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights dates back to 1948. Other treaties and declarations, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), came into force shortly after the Single Convention. However, it took until 1988 when for the first time a drug control convention referred to human rights (Article 14(2) of the 1988 Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Convention) (see Lines Reference Lines2017 for a detailed discussion of the relationship between drug control and human rights).

Beyond potential incompatibilities between human rights norms and the drug prohibition regime (Lines Reference Lines2017: Ch 4), the literature identifies additional norm collisions such as collisions between a drug criminalisation norm and norms prohibiting inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment (Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, Worth and Wilson2015); between the norm on the eradication of illicit crops and environmental protection norms (Grisaffi Reference Grisaffi, Labate, Cavnar and Rodrigues2016); and between drug criminalisation norms and the right to health (Burke-Shyne et al. Reference Burke-Shyne, Csete, Wilson, Fox, Wolfe and Rasanathan2017).

From these various norm collisions, we chose the norm collision between the prohibition of coca leaf chewing (based on the classification of the coca leaf as a drug) and human rights protecting indigenous practices and cultural heritage to illustrate the feasibility of our argument (for an overview see: Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer2013): First, the international debate on the appropriateness of coca leaf chewing illustrates our central argument that norm collisions may remain dormant for a considerable time, despite early and recurrent problematisation by individual actors. Second, and related to the first point, the case allows us to analyse how changes in structural factors and actor constellations have affected the process that eventually led to the transformation from dormant to open. Third, the collision constitutes, in its latter stage, an interface conflict, the central unit of analysis of this special issue (see Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn, this issue). As this issue has been debated in-depth by relevant actors such as the INCB and studied in the literature on international drug control (as the discussion below demonstrates), the example provides us with a substantive amount of data to reconstruct and explain its activation.

The collision between drug prohibition and indigenous practices

The first part of our argument holds that while dormant norm collisions are all-pervasive, they are not always out in the open. As a dormant collision, the collision between drug prohibition and the protection of indigenous practices such as coca leaf chewing had been smouldering since the 1950s. The norm collision was activated and turned into an open norm collision in 2009 when it also became an interface conflict. Our analysis, thus, emphasises the role of agents in bringing incompatibilities between drug prohibition norms and norms on indigenous cultural heritage to the fore, thereby activating the norm collision. The following analysis presents our reconstruction of the discourse.

Dormant norm collision and a temporary response: 1950–1990.

The question of whether the practice of coca leaf chewing constitutes a form of drug addiction was debated from the very beginning of the post-World War II international drug control regime. While a report in 1950 had argued that coca leaf chewing was not an addiction ‘in the medical sense’ (ECOSOC 1950: 93), a 1952 report of the Expert Committee on Drugs Liable to Produce Addiction (today: WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence) classified coca leaf chewing as an addiction (Metaal et al. Reference Metaal, Jelsma, Argandoña, Soberón, Henman and Echeverría.2006: 6; World Health Organization 1952: 10). This distinction is important, as the suggestion to ban coca leaf chewing during the negotiations of the 1961 Single Convention was based on this report and its finding that it is a form of drug addiction.

The meeting records of the 1961 Single Conventions reveal that this suggestion was met with some resistance. During the debate on the Single Convention in 1961 representatives of Bolivia and Peru contested the explicit ban on coca leaf chewing, deemed as legitimate by the US and others as a way to apply the norm of drug prohibition. The following quotes illustrate this:

Mr. MENDIZABAL (Bolivia) said that […] ‘some provision should be made in the Convention to allow chewing of coca leaves to continue for a certain time . In Bolivia, coca chewing was a long-established habit among the peasants’ (United Nations 1961b: 170, emphasis added).

Mr. ESTRALLA (Peru): […] ‘It could be said that his country had received a gift from Nature that was both good and bad, the coca bush;’ (United Nations 1961a: 172, emphasis added).

Both quotes illustrate that certain actors felt an immediate prohibition was not appropriate, given the established, widespread, and locally accepted social practice of coca leaf chewing. In our reading this widespread practice has evolved into a social norm: actors in the Andean region deem the practice of coca leaf chewing by indigenous people in the region as appropriate (see also Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer2013: 295).

As these contestations of the ban with reference to social norms of indigenous people were not taken up by other actors, i.e. not intersubjectively shared, we classify the norm collision as dormant. Furthermore, an immediate, albeit temporal, solution to the dormant norm collision was created through including a moratorium in the Single Convention, allowing inter alia coca leaf chewing for states wishing to do so for 25 years – until 1989 – on their territory (1961 Single Convention Article 49(1)c and 2(e)).Footnote 5 As meeting records show, actors expressed the view that within 25 years, the practice would cease to exist (United Nations 1961b: 101).

Coca leaf chewing after the moratorium: 1990–2009.

When the moratorium ended in 1989, the practice of coca leaf chewing was still prevalent in the Andean region. An INCB report from 1989 noted this and suggested to better assist Bolivia and Peru (INCB 1989: 12). Yet, coca leaf chewing was, while mentioned in subsequent INCB reports, not hotly debated. In 1992, Bolivia and Peru requested a re-evaluation of the coca leaf at the 36th session of the CND, supported by a number of grass-roots movements (Metaal et al. Reference Metaal, Jelsma, Argandoña, Soberón, Henman and Echeverría.2006: 7). However, the WHO committee responsible for these evaluations declined the request (Metaal et al. Reference Metaal, Jelsma, Argandoña, Soberón, Henman and Echeverría.2006: 9; CND 1993: 39). As a response to these attempts to renegotiate the appropriate position on coca leaf chewing, the INCB in its 1992 Annual Report declared any attempt to legalise coca leaves as violating the Single Convention (INCB 1992: 6–7). In 1995, a study conducted under the auspices of the WHO and the UN Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute cast doubt on the characterisation of coca leaf chewing as a form of substance abuse (World Health Organization and UNICRI 1995). The change in the WHO position between the 1952 report and the 1995 report is noteworthy as it mirrors a general shift in attitude towards a more tolerant perspective on indigenous peoples and their right to uphold traditional practices (Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer2013: 319–22). Due to US pressure, however, the report was not published. Over and above that, the contentious issue was not picked up by other actors, leaving the norm collision dormant. This changed about ten years later.

In January 2006, Evo Morales, a coca farmer and former General Secretary of the Bolivian coca farmer union (Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer2013: 298), was elected as the new Bolivian president. The same year, Bolivia announced at a CND meeting that it would like to see the prohibition of coca leaf chewing removed from the Single Convention (CND 2006: 46). The INCB responded in a report, making clear that the proposed measures would not be in line with the Single Convention’s limitation on drug use for medical and scientific use (Single Convention, Article 4(c)) (INCB 2007: 27). In reaction, Evo Morales expressed his critique in a letter to then UN Secretary Ban Ki-Moon (Morales Reference Morales2008).

2009 until today – Activating the norm collision.

At a high-level meeting of the CND in 2009, Morales began his speech by ostentatiously chewing coca leaves. He then called for an end of the coca leaf chewing prohibition as codified in the 1961 Single Convention. The incident and his previous speeches indicate that Morales perceived a norm collision between the prohibition of coca leaf chewing and indigenous rights as problematic. Bolivia formalised its initiative in March 2009 by proposing to delete Article 49(1)c and 2(e) of the Single Convention (Bolivia Reference Bolivia2009a). Bolivia justified the suggested amendment by reference to indigenous rights:

The restrictions on and prohibition of coca leaf chewing […] constitute a violation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples set forth in, inter alia, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ and other treaties (Bolivia Reference Bolivia2009a: 3, emphasis added).

A few weeks later, in May 2009, the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) took up Bolivia’s position and recommended amending the Single Convention. It stated that the Single Convention’s rules on coca leaf chewing are inconsistent with the UNDRIP (UN General Assembly 2007; see also Lines Reference Lines2017: 165–6):

The Permanent Forum recommends that those portions of the Convention regarding coca leaf chewing that are inconsistent with the rights of Indigenous Peoples to maintain their traditional health and cultural practices, as recognised in articles 11, 24 and 31 of the Declaration, be amended and/or repealed (UNPFII 2009: 89, emphasis added; also see International Drug Policy Consortium 2018: 68).

At the end of July 2009, ECOSOC opened an amendment procedure under Article 47 of the Single Convention (ECOSOC 2009). In 2010, the UNPFII backed the amendment process and urged its members to support Bolivia (UNPFII 2010: 6). Eighteen Latin American and Caribbean States supported the proposal (Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer2013: 302). Ecuador made an explicit reference to UNDRIP Articles 11–13, which protect the right of indigenous people to ‘to practice and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs and to manifest, practise, develop and teach their traditions and customs’ (Ecuador Reference Ecuador2011: 2). Furthermore, Ecuador argued that ‘[t]he prohibition [of coca leaf chewing] is unjustifiable and discriminates against indigenous peoples that maintain this ancestral practice’ (Ecuador Reference Ecuador2011: 2, emphasis added). It is here, in this protracted intersubjective exchange following the Bolivian proposal, that we can identify the activation of the norm collision on the international level as well as its shift from dormant to open, a view also supported by the literature (Lines Reference Lines2017: 103).Footnote 6

Between 2009 and 2011 a number of UN member states sent in notes verbales rejecting the proposal, e.g. the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, the U.S., Sweden, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Canada. It is noteworthy that the U.S. organised an informal group of states, called the ‘Friends of the Convention’, to mobilise a larger number of rejections of the Bolivian proposal (Forsberg Reference Forsberg2011: 11; Bewley-Taylor Reference Bewley-Taylor2013: 62). Given that a proposed amendment can only enter into force when no objections are raised within 18 months (Article 47 Single Convention), the proposal was declined.

The open collision also constitutes an interface conflict between the INCB and the UNPFII, as both authorities expressed their positional differences with reference to norms in their respective spheres. UNPFII endorsed Bolivia’s claim of a norm collision in May of 2009, a position it reiterated in 2010 and 2011. In 2010, the UNPFII explicitly supported the amendment procedure (UNPFII 2010, 2011). The INCB stated in its 2010 report that it regretted the steps taken by Bolivia, but refrained from mentioning indigenous rights or the UNPFII position (INCB 2011).

Following the failure of the process, Bolivia left the Single Convention in 2011 and re-entered with a reservation on the coca leaf chewing prohibition in 2013. Despite attempts by the U.S. to garner sufficient rejections of this reservation, less than the required one-third of all parties to the Convention rejected it. The entire process was strongly criticised by the INCB, who saw the reservation as ‘contrary to the fundamental object and spirit of the 1961 Convention’ (INCB 2013: 4). The INCB furthermore argued with reference to coca leaf chewing that ‘[c]ertain aspects of Bolivia’s drug control legislation and policy are in contravention of the international drug control conventions’ (INCB 2012: 4). To the present day, there is neither a political nor a legal solution in sight and Bolivia has only solved the issue for itself on the national level. The norm collision and the interface conflict remain active as official reports of the Organization of American States in 2013 (Organization of American States 2013: 47), the UNGA Special Session on International Drug Control in 2016 (UN General Assembly 2016) and the OHCHR in 2018 (OHCHR 2018: 14) continue to refer to UNDRIP or more broadly indigenous rights in the context of plant-based resources such as coca.

When do norm collisions come to the fore? Structures, actors, scope conditions

While the previous section traced the shift from a dormant to an open norm collision, we will now discuss why the norm collision was activated only in 2009. Following established theories on the causes of norm change, we assess the explanatory value of several scope conditionsFootnote 7 for the study of norm collisions and interface conflicts. These relate to the quality of norms (specifically their precision and obligation) and to changes in power structures and actor constellations.

Quality of norms.

We begin with a discussion of changes in the (legal) quality of norms as a potential scope condition for the activation of norm collisions. The prohibition of coca leaf chewing is based on the 1961 Single Convention, which for long possessed a higher degree of obligation and precision than norms protecting indigenous cultural practices. The moratorium allowed the two norms to coexist in order to avoid non-compliance by some Andean states in which coca leaf chewing was still widespread. However, it never presented the two norms as being on equal footing. We show above that the relation between the two sets of norms changed, once the UN General Assembly adopted UNDRIP in 2007.

Following Abbott et al.’s legalisation approach, we assume that a relation between the quality of norms and norm change exists. For the purpose of this article, we specifically focus on precision and obligation as two of the three dimensions of legalisation: precision ‘means that rules unambiguously define the conduct they require, authorize, or prescribe’ (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal2000: 401). It ‘narrows the scope for reasonable interpretation’ (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal2000: 412). The more imprecise a norm is, the easier it is to define actions as appropriate under that norm. It thus seems plausible to expect that norm collisions do not come to the fore when the two (or more) norms are imprecise because this enables actors to be much more flexible when applying the norm.

Obligation implies that ‘states or other actors are bound by a rule or commitment or by a set of rules or commitments’ (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal2000: 401). As all dimensions of legalisation, obligation is seen as a continuum, in this case ranging from ‘expressly non-legal norm’ to binding jus cogens rules (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter and Snidal2000: 404). We assume that norms on equal footing bear a high potential for activated norm collisions as strong hierarchies between norms already imply that actors agree on normative priorities. When these hierarchies flatten, we expect a stronger likelihood for norm collisions. Our case confirms these assumptions:

Following the end of the 25-year moratorium on coca leaf chewing, the prohibition norm became less flexible as the Single Convention allowed no longer a deviation concerning the social norm of coca leaf chewing. This can be regarded as an increase in the degree of obligation and precision. At the same time, beginning in the 1990s, indigenous rights were strengthened both on the national and the international level – on the national level for example through amendments of national constitutions recognising indigenous rights (Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer2013: 295). The new Bolivian constitution of 2009 even recognised that coca is not a narcotic drug (Bolivia Reference Bolivia2009b: Article 384).Footnote 8 Furthermore, in 2011, the Colombian Supreme Court held that the prohibition on ‘narcotic drugs and psychotropic drugs’ did not apply to indigenous peoples when they used these substances in ancestral practices (Wisehart Reference Wisehart2019: 110). On the international level, the aforementioned ILO Convention C169 (entry into force 1991), especially Article 2(2)Footnote 9 and UNDRIP 2007, especially Articles 11, 24, and 31 are of relevance.Footnote 10 Concerning C169 it is noteworthy that of the 23 countries that ratified the Convention, 14 are from South America. Also, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has referred to the Convention several times when arguing for ‘cultural particularism’ (Wisehart Reference Wisehart2019: 109). No INCB report has ever referred to ILO C169 since its adoption and entry into force, but participants referred to it during the 49th Session of the CND (CND 2006: 46). Analysing the speech acts by Bolivia and the UNPFII cited above, we thus find that the norm collision concerning coca leaf chewing was activated only once actors could draw on a more precise set of widely accepted norms in UNDRIP protecting indigenous practices, to bring them into collision with the precise and legalised norm of the leaf-chewing prohibition.

Even though UNDRIP is non-binding, we argue that the degree of precision and obligation of indigenous rights were increased, given that the declaration outlines the individual and collective rights of Indigenous Peoples as well as duties of States Parties and given its adoption by the UN General Assembly with 143 of 159 states voting in favour of the resolution.Footnote 11 Furthermore, the UNPFII interprets UNDRIP as protecting the traditional use of the coca leaf (Wisehart Reference Wisehart2019: 111).Footnote 12 One may therefore safely argue that the degree of precision and obligation of norms protecting indigenous rights increased on the horizontal level (i.e. between states and between international organisations) since ILO C169 and UNDRIP entered into force (Wisehart Reference Wisehart2019: 114). Wisehart (Reference Wisehart2019: 112) goes as far as to argue that ‘at least within the region of South America, indigenous rights – including cultural rights – have become part of (regional) international law’. UNDRIP strengthened the status of indigenous rights globally and gave them more precise contours. Both documents now constitute a central point of reference for actors who argued in favour of the protection of coca leaf chewing as an indigenous practice and tradition, facilitating the activation of the norm collision.

Changing power structures and actor constellations – Hegemony and advocacy coalitions

Actor constellations and the power relations among them are a popular explanatory factor in theories on norm change. Neorealist accounts privilege the concept of hegemony in explaining the emergence, spread, and transformation of norms. It is assumed that the spread of norms hinges on the will and the capabilities of a great power which bears the costs of institution building and uses its power to enforce compliance (Gilpin Reference Gilpin1981). While concepts of hegemony in IR vary, scholars agree that normative orders are established and stabilised in periods of hegemonic leadership. Powerful states are central in either coercing or leading others to accept and follow norms (Krasner Reference Krasner and Rittberger1993). While these assumptions do not explicitly refer to the relations between different norms, we deem it plausible to assume that powerful states are also in a position to shape relations between norms. A dominant narrative in international relations holds that the ‘old liberal international order was designed and built in the West’ (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2011: 57) and that the rise of new powers has led to an increase in the contestation of ideas and norms underlying a global order built by Western states and particularly the United States. We take these ideas on a link between power structures and norms seriously and examine if norm collisions and interface conflicts are activated when power structures and actor constellations change.

The analysis of the coca leaf case demonstrates the relevance of changing power constellations for the activation of norm collisions. The U.S. has played a strong role in developing the international drug control regime (McAllister Reference McAllister2000). The Single Convention ‘greatly reflected the aspirations and goals of the United States’ (Bewley-Taylor and Jelsma Reference Bewley-Taylor and Jelsma2011: 8). The hegemonic position of the U.S. remained relatively stable throughout the dormant phase of the norm collision between 1950 and 2009. Even when, in the context of a 1995 report by the WHO, a changing position on coca leaf chewing could be identified, the U.S. was capable of preventing the publication of the report, specifically by threatening to cut funding for the WHO should the WHO not distance itself from the study (Metaal et al. Reference Metaal, Jelsma, Argandoña, Soberón, Henman and Echeverría.2006: 4, 8; Bewley-Taylor Reference Bewley-Taylor2012: 259; World Health Organization 1995: 229).

U.S. dominance in the field of international drug control started to ‘crumble’ when in the late 2000s other actors gained more authority in the field. We observe that additional IOs (both old ones such as the WHO and ILO and newer ones such as the UNPFII) as well as influential transnational non-state actors such as the Transnational Institute – an international research and advocacy institute – began to take interest in the issue of coca leaf chewing shortly before the norm collision became activated. These activities accompanied broader shifts in positions in the issue area from a criminalisation approach to approaches more cognisant of human rights and harm reduction (Levine Reference Levine2003: 145). After 2009, the U.S. were no longer capable of organising an effective alliance against the Bolivian government’s bold demand to remove coca leaf chewing from international drug control policies. The U.S. did not succeed in mobilising the ‘friends’ of the Single Convention – as a consequence, they failed to prevent Bolivia’s re-entering of this convention with a reservation on coca leaves. At the same time, the coalition of state and non-state actors endorsing the Bolivian position had grown. We find that U.S. influence over international drug policies has significantly diminished (see also Jelsma Reference Jelsma2017: 21–2).

These changes in power structures and actor constellations speak to another prominent scope condition in the literature on norm emergence and transformation: the existence of transnational advocacy networks or coalitions, composed of state and non-state actors, including IOs, whose formation is motivated by principled ideas or values (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). A number of seminal studies have highlighted the interplay between norm evolution and such transnational coalitions of state and non-state actors (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2007; Epstein Reference Epstein2008; Price Reference Price1998). As these studies make clear, the emergence of such advocacy networks open up new discursive spaces and create possibilities for a reconsideration of established norms. It thus seems reasonable to assume that norm collisions and interface conflicts are more likely when large coalitions of non-state and state actors advocate for a specific issue and normative position inside and outside IOs. However, in the case of coca leaf chewing, we cannot find much evidence that typical advocacy coalitions did so. As our account of the coca leaf case shows, there were, in fact, different actors endorsing norm change such as the WHO, Latin American countries, or the Transnational Institute – who strongly supported the Bolivian position by publishing numerous briefing papers and opinion pieces (e.g. Jelsma 2011). The endorsement of Bolivia’s position by the UNPFII – an institution representing indigenous peoples with a disputed legal personality under international law – can also be seen as another strong non-state proponent of the anti-prohibitionist position on coca. However, these actors did not form a value-driven network or participate in a larger transnational campaign. Instead, the empirical material highlights state coalitions as central norm entrepreneurs. While Bolivia failed to build a coalition of like-minded states (Bewley-Taylor Reference Bewley-Taylor2013: 62), the U.S. and its allies collaborated to uphold the prohibition of coca leaf chewing. We, therefore, hold that the transnational advocacy network scope condition – at least in the specific case of the coca leaf chewing norm collision – does not hold.

IV. Conclusion

In our contribution, we put forward a constructivist agency-oriented approach to norm collisions and interface conflicts. It rests on a conceptual differentiation between dormant and open norm collisions, putting emphasis on actors’ interpretations and articulations. By tracing debates in the policy field of international drug control, we showed that different and long-established norms were potentially relevant to international drug control policies. The post-1945 drug control regime with its (presumably) consented prohibition norms has always existed alongside alternative public health and human rights norms, including indigenous rights. Ample possibilities for norm collisions were thus given.

Second, we argued that dormant norm collisions must be activated to become socially consequential. Our empirical observations suggest that dormant norm collisions are a common phenomenon in international relations, while open ones are much less frequent. The move from dormant to open norm collision – the moment of activation – requires agency. Open norm collisions may evolve into interface conflicts when at least one norm is associated with an international authority. Our case study exemplifies an ongoing interface conflict with open positional differences between traditional drug control authorities on the one hand and proponents of a liberal stance towards coca leaf chewing justified by recurrence to indigenous rights.

The eventual activation of this norm collision was facilitated by changes in power structures and in norm quality. As our analysis demonstrated, previously its activation had long been obstructed by the U.S. and its allies. Concerning norm quality, the collision was enabled by a strengthening of indigenous rights which underwent a process of gradual legalisation. In our exploration of potential explanatory factors, we had relied on assumptions formulated for the purpose of studying single norms. We have transferred them to the dynamic relationship between norms and probed their potential explanatory strength. Our article indicates that it is a promising avenue to refine and explore these scope conditions further, not least in comparative case studies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the OSAIC Research Unit for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article. We presented the argument and the empirical analysis at the ECPR General Conference 2018 in Hamburg, the DVPW Congress in 2018 Frankfurt, the 2019 ISA Annual Convention in Toronto, and the research seminar of the Research Group ‘The International Rule of Law – Rise or Decline?’. We thank the participants and especially Noele Crossley, Georg Nolte, Elvira Rosert, and Andreas von Staden for valuable comments. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and Jeffrey Dunoff for valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank Marleen Boschen, Markus Specht, and Martha van Bakel for research assistance and proofreading. Research for this article was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant HO 3915/4-1 and grant LI 1947/3-1.

The authors appear in alphabetical order and contributed equally to this article.