On October 7, 2023, Palestinian armed groups, chiefly Hamas's armed wing, breached the fence around the Gaza strip and launched attacks on Israeli territory. Over several hours, Palestinian fighters killed 1,269 people, mostly civilians,Footnote 1 engaged in sexual violence and torture,Footnote 2 and took 253 hostages. Footnote 3 The same day, Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared, “Israel is at war,” and the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) launched air strikes and later a ground invasion of Gaza.Footnote 4 In the eleven months since, Palestinian groups have continued to hold, mistreat, and kill hostages and launched rockets into Israel's population centers.Footnote 5 Meanwhile, the IDF has killed an estimated forty-one thousand people in Gaza, mostly civilians,Footnote 6 engaged in sexual violence and torture of Palestinian detainees,Footnote 7 damaged or destroyed most of the food, water, and medical infrastructure,Footnote 8 and restricted humanitarian access, with dire consequences.Footnote 9 Civilian casualty experts argue the death toll (which excludes the likely greater number killed “indirectly” through disease and deprivation) far exceeds what we have come to expect from contemporary military campaigns.Footnote 10 Both sides have committed violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), too many to list individually.Footnote 11

The prevalence of violations is not unique to this conflict. What is unusual in Gaza is that catastrophic civilian harm coincides with more than a perfunctory claim of legal compliance: Israeli officials consistently and often proactively argue that their military operations adhere to international law,Footnote 12 with support from some legal experts.Footnote 13 This has put the spotlight on international law. Three proceedings before the International Court of Justice (ICJ)—South Africa's allegation that Israel is engaged in genocide, Nicaragua's allegation that Germany is complicit in Israel's alleged violations of international law, and an Advisory Opinion affirming the illegality of Israel's continued occupation—as well as the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor's request for arrest warrants against Hamas and Israeli leaders garner unprecedented public interest. These discursive and judicial processes could repair and solidify international law's role as the yardstick for normative evaluation of war, including vis-à-vis powerful Western states. Or they could reveal IHL's incapacity to meaningfully restrain war, catalyzing legal deterioration.

We may not know the net effect of the war on international law's trajectory for some time. However, from the beginning, the devastating human toll of this conflict has underscored the urgent need for international law to fulfill three distinct functions: ex ante action-guidance; concurrent third-party evaluation; and ex post accountability. Much commentary on Gaza has prioritized concepts and institutional frames developed for accountability. For critics of a party's military operations, charging war crimes may express stronger disapproval than “mere” IHL violations. For those defending that conduct, calling attention to law's accountability function often grounds a demand to suspend legal judgement until after adjudication.Footnote 14 Accountability is important. However, IHL is also meant to constrain belligerents’ actions ex ante and to help third states evaluate these actions so they can concurrently meet their own obligations. Law must discharge these functions while hostilities are ongoing or not at all.

To be sure, IHL faces challenges in fulfilling its action-guiding and evaluative functions in real time.Footnote 15 In war, information is partial, cognitive biases are primed, and propaganda machines operate at full tilt.Footnote 16 The resulting epistemic fissures can lead to disagreement on basic facts, while out-group bias fuels extreme views of what ought to be permitted in pursuit of a military aim.Footnote 17 Still, it would be a mistake to invoke this epistemic environment to defer legal analysis. Instead, international law must provide the doctrinal resources to navigate the uncertainty and contestation that characterizes armed conflict.

The war in Gaza has spotlighted two doctrinal questions that partly underpin polarized evaluations and that go to the heart of law's capacity to discharge its action-guiding and evaluative functions in real time: first, how to conceptualize intent in war, and second, how to evaluate international courts’ early-stage engagement with ongoing conflict. We submit that the functional differentiation of law's tasks, in turn, is critical to answering these questions. In Part I, we clarify intent requirements and argue that their meaning and inference may differ across international law's three functions. In Part II, we clarify the doctrinal significance of international courts’ provisional engagement with ongoing armed conflict particularly for guiding third states’ evaluations in real time.

I. Belligerent Intent in Gaza

In criminal law, “a guilty mind” is generally a precondition for accountability. However, in war, intent also determines action guidance and third-party evaluation. Some strikingly divergent evaluations of Israel's conduct in Gaza hinge on what intent is attributed to Israel or its officials. Are mass civilian casualties unavoidableFootnote 18 and potentially proportionateFootnote 19 in this operational context? Or do they evince intentional attacks against civilians or civilian objects in violation of distinction?Footnote 20 When it comes to hunger in Gaza, some portray the crisis as a “tragic” consequence of civilians being “caught in the midst of intense hostilities,”Footnote 21 while others identify intentional starvation of civilians as a method of warfare.Footnote 22 And of course, whether we need “to sound the alarm”Footnote 23 about genocide or whether the allegation is “morally repugnant”Footnote 24 depends on whether the observer entertains the possibility that Israel has the special intent to “destroy in whole or in part” Palestinians as a group.

Some of these divergent judgments relate to contested facts. Others, however, stem from doctrinal confusion about how to conceptualize intent. We identify five dimensions of this confusion. First, intent in law has multiple meanings, including acting with purpose (direct intent), but also acting with knowledge (indirect or oblique intent).Footnote 25 Which is required for some prohibitions is debated. Second, the object of intent may be contested. Whereas some violations are triggered merely through prohibited conduct (regardless of consequences), the difference between purpose and knowledge matters for prohibitions that include a consequence element or define intent in relation to consequences. Third, when prohibited intent is not limited to purposive acts, the question arises whether it extends to acting with less than perfect foresight—e.g., taking a substantial and unjustified risk. Fourth, when purpose is central to a prohibition, an actor's motives and attitudes (including regret) may cloud legal analysis. Finally, what does state intent mean when officials involved in state policy operate with divergent intentions?

The threshold for criminal accountability is often higher than for “mere” legal violation. And yet, most jurisprudence on intent emanates from international criminal law. Intent defined for law's accountability function therefore shapes our understanding of intent for constraining belligerents’ actions and evaluating their conduct in real time, producing a “forensic fallacy” that confuses “[the] narrowness and precision in criminal statutes with defining features” of the prohibited act.Footnote 26 Due process demands that law discharge its accountability function with a high inferential standard. Moreover, “criminal intent” must track blameworthiness, not only wrongfulness of conduct. However, third-party efforts to ensure compliance through exercising appropriate leverage cannot plausibly be conditioned on operating like a criminal court. Suspending judgment until adjudication subverts IHL's capacity to protect civilians. Rather, prohibited intent must be conceptualized and inferred differently depending on the legal function at stake.

In the following, we clarify the meaning of intent as applied to the conduct of hostilities (I.A), starvation (I.B), and the genocide allegation before the ICJ (I.C). We show where law already differentiates intent for the purpose of law's accountability function from intent appropriate for law's action-guiding and evaluative functions, but also highlight open doctrinal questions. We focus primarily on intent in relation to Israel's conduct since, with two noted exceptions, there is little contestation about intent in evaluating Hamas's actions.

A. Conduct of Hostilities in Gaza

In May 2024, the U.S. State Department reported to Congress that it had found “no direct indication of Israel intentionally targeting civilians,” even though it described several strikes, specifically on humanitarian assistance missions, without a military target and flatly stated that “Israel could do more to avoid civilian harm.”Footnote 27 The United States concluded that it did not have to suspend arms transfers to Israel. But does the report really rule out that Israel is violating IHL's “cardinal principle” of distinction? The principle is cast in terms of prohibitions on making civilians or the civilian population “the object of attack,” or “directing attacks against” protected civilian(s)/objects—terms commonly understood to implicate intent. Israel argues that “a commander's intent is critical in reviewing the principle of distinction during armed conflict.”Footnote 28 But what does intent mean here?

Jens David Ohlin has argued that violations of distinction require direct intent, i.e., acting with purpose, vis-à-vis the attack's impact on civilians. This, he argues, is because IHL does not prohibit knowingly killing civilians or destroying civilian objects, if compliant with precautions and proportionality.Footnote 29 On attaching intent to impact, Michael Bothe seems to agree that “not only the actual conduct (e.g., the dropping of the bomb), but also the consequences (e.g., hitting a civilian object) must be covered by the intent.”Footnote 30 The State Department may rely on something like this approach in arguing that a pattern of attacks without identifiable military objectives does not imply violations of distinction without evidence that what the report considers avoidable civilian deaths were brought about with purpose. We proffer three reasons against this interpretation of prohibited intent.

First, Ohlin's correct observation that “distinction and proportionality must be understood as two normatively distinct prohibitions”Footnote 31 does not require that the attacking commander violates distinction only if she seeks to harm civilian(s)/objects. Rather we must disaggregate two questions often merged—“who the attacker wishes to affect [and] who he is aiming his attack at.”Footnote 32 Even in relation to war crimes, the ICC's Elements of Crimes document raises only the latter question: it requires meaning to engage in an attack (purposive intent attached to conduct) that is directed (aimed) against what is known to be a civilian object/person.Footnote 33 This knowledge characterizes the prohibited conduct and its circumstances, not its consequences. The key is that the perpetrator “intended” civilian objects/persons “to be the object of the attack,” Footnote 34 not that she wished to kill or injure them. Intentionally launching an attack known to be directed against a civilian person/object violates distinction (including criminally). This is clearly distinct from the separate ban on intentionally directing an attack against a military objective that may be foreseen (known) to cause (clearly) excessive incidental civilian harm, thus (criminally) violating proportionality.Footnote 35

Second, International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) case law supports that for the purpose of violating distinction, prohibited intent attaches not to the consequences, but to the direction of the attack. Unlike the Rome Statute, ICTY jurisprudence considers harmful consequences—“deaths and/or serious bodily injury within the civilian population or damage to civilian property”Footnote 36—a constituent element of the crime. However, these consequences primarily demarcate whether an attack was “grave enough to bring the offence into the scope of the Tribunal's jurisdiction.”Footnote 37 Moreover, the Appeals Chamber states categorically that in “none of [the] declarations of customary international law . . . is the prohibition of attacks on civilians or civilian objects explicitly combined with statements regarding a finding of actual injury to civilians or damage to civilian objects.”Footnote 38 Nodding to functional differentiation, the judges highlight that ex ante “the purpose of this prohibition is not only to save lives of civilians, but also to spare them from the risk of being subjected to war atrocities.”Footnote 39

That a violation of distinction hinges at most on knowledge of the target's status and not the consequences of an attack (sought, foreseen, or realized) explains why an attack that is directed against civilian(s)/objects violates distinction even if the attacker seeks military effects, i.e., has an ultimate military purpose.Footnote 40 In Gaza the reported target category “operatives’ homes” illustrates this.Footnote 41 Homes are presumptively civilian until it is established that they are used to make an effective contribution to military action.Footnote 42 Facts are contested, but attacking homes while the operatives are out would straightforwardly violate distinction. What about the alleged approach “to destroy private residences in order to assassinate a single resident suspected of being a Hamas or Islamic Jihad operative?”Footnote 43 Even assuming the operatives are plausibly legitimate targets (for example, on the basis of their continuous combat function), their mere presence would not transform their personal homes into military objectives.Footnote 44 If these attacks were directed against the home rather than the person, they would violate the principle of distinction even if the intended consequence was the death of the latter.

Differentiating between a person and the surrounding home being the object of attack may seem technical, but it clarifies legal assessments. Using munitions that destroy the home, rather than available alternatives that would target the individual while preserving the home, in addition to violating precautionary requirements, would entail directing the attack at the home, regardless of how one might construe the attack's purpose. Similarly, attacking a home without certainty that the combatant is there, again in addition to violating precautions, could only be construed as directing the attack at the home, regardless of whether it would be plausible to construe the (wished for) purpose as killing the person. The difference matters. The widespread destruction of family homes in Gaza has devastating humanitarian consequences.Footnote 45

That “military purpose” of an attack alone cannot render a civilian object a legitimate target of direct attack is relevant also in other contexts. It would for instance rule out directing an attack against a civilian structure wishing to collapse it over, and thereby neutralize, a distinct military objective. On October 25, 2023, a twelve-story residential tower in the Al-Yarmouk neighborhood “was directly hit” by an airstrike which the IDF labeled a “strike on a Hamas terror tunnel.” Footnote 46 The attack collapsed the tower and killed eighty-one women and children. Distinction would have precluded directing the attack at the building (presumptively a civilian object) as the means to destroying the tunnel.Footnote 47 If, on the contrary, the tunnel was targeted, and the residential tower was destroyed incidentally, the legality of the attack would turn on the preventability and the very likely excessiveness of expected civilian harm.

Third, knowledge of the target's civilian status is not necessary to violate distinction. The customary war crimes regime,Footnote 48 the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Commentary to Article 85(3) of the First Additional Protocol,Footnote 49 and ICTY jurisprudence envisage criminal accountability for reckless targeting of civilians/objects.Footnote 50 Recklessness lies beneath knowledge on an epistemic continuum. The threshold for “mere” illegality is still lower. Target misidentification violates IHL if the attacking party fails to “do everything feasible to verify” the target's status and to take “constant care” to spare civilians.Footnote 51 In cases characterized by doubt regarding target status, civilian status must be presumed and attack eschewed (although how much doubt is disputed).Footnote 52 Concretely, even if those who directed the Israeli airstrike that killed seven World Central Kitchen aid workers did not know the persons targeted to be civilians, information in the public domain indicates that the latter were likely targeted despite a substantial and unjustifiable risk that they were civilians (i.e., recklessly) and almost certainly in context defined by doubt.Footnote 53

Ultimately, even if the war crimes status of certain strikes cannot be determined in real time, the United States’ findings of a pattern of attacks without a plausible military target and the diagnosis that the IDF did not do everything feasible to avoid civilian casualties, possibly including target verification, entail clear IHL violations. For the United States to withhold evaluative judgment here is: (1) to hide behind a (highly deferential) application of the narrowest interpretation of intent developed for war crimes (IHL's strictest accountability function); and (2) to fail to consider IHL as a whole, including its rules on precautions and doubt.

A legal assessment of Hamas's conduct, though significantly less polarized, likewise benefits from differentiating intent by law's functions. We argued above that seeking lawful consequences cannot legitimate the use of unlawful means. Yet, seeking unlawful consequences (for example, killing or destroying civilian(s)/objects) can taint what might otherwise be lawful means (such as directing attacks against lawful military objectives). Concretely, even assuming some Hamas rocket fire into Israel has been directed (loosely) against military objectives,Footnote 54 if those firing sought also to harm civilians, they violated distinction.Footnote 55 Such an attack would be directed at both the military objective (as the target) and the civilians (whose harming is one of the attack's animating purposes);Footnote 56 neither would be harmed “incidentally.” Even in the criminal domain, the ICC has identified combined attacks on both civilian and military targets as attacks directed against both.Footnote 57 Purpose is inculpating but not exculpating because an unlawful purpose changes the nature of conduct, but a lawful purpose cannot rehabilitate unlawful conduct.

The use of human shields, a charge often laid against Hamas, further illustrates the need to consider IHL as a whole, across legal functions. Here, both war crime and underlying IHL prohibition attach only to intermingling undertaken with the purposive intent to “shield from attack” or “favor or impede military operations.”Footnote 58 Particularly in densely populated areas, this cannot easily be inferred from context, making violations hard to diagnose in real time.Footnote 59 However, where it could be feasibly avoided, Hamas's practice of “locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas” would straightforwardly violate Article 58 of the First Additional Protocol, regardless of intent. This precautionary requirement, even if it does not give rise to criminal accountability, is critical for real-time evaluation of Hamas's conduct.

The use of human shields also highlights a further doctrinal confusion that can be clarified by differentiating among law's functions. Hamas's alleged criminal conduct is often invoked to rebut the alleged disproportionality of Israeli attacks that kill many civilians, based on the argument that the defender's “ultimate responsibility” for civilian casualties modifies the permissibility of an otherwise disproportionate attack.Footnote 60 The U.S. Law of War Manual also argues that “the responsibility of the defending force is a factor that may be considered in determining whether such harm is excessive.”Footnote 61 Space does not permit a full discussion of the legal debates about shielding. However, this invocation of the shielding party's responsibility is clearly erroneous in two ways. First, at the accountability stage, Hamas's responsibility for human shielding would not preclude either the state responsibility of Israel or the criminal responsibility of its officials for engaging in attacks with clearly excessive civilian harm. Responsibility is not zero sum. Second, even assuming Israel's ex post responsibility for excessive civilian casualties were diminished or excused by Hamas's use of those civilians as shields, this would not affect ex ante impermissibility. Excuses are not justifications, and civilians do not forfeit their protection because they have suffered a violation by the adversary. The First Additional Protocol reflects this, specifying that even purposive human shielding by one party does not “release” the other from its legal obligations relating to civilians.Footnote 62

B. Starvation and the Siege of Gaza

Two days after the October 7 atrocities, Israel's defense minister ordered “a complete siege” on Gaza, specifying “There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed.”Footnote 63 Charging that “the citizens of Gaza” were celebrating Hamas's crimes, the head of Israel's agency for the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories promised the encirclement would bring “hell.”Footnote 64 Credible reports indicate that in the ensuing months, Israel: significantly restricted humanitarian access to Gaza (especially the north);Footnote 65 attacked “deconflicted” humanitarian actors, distribution centers, and convoys;Footnote 66 destroyed agricultural areas and water systems;Footnote 67 and restricted fuel, electricity, and the entry of mobile desalination units.Footnote 68 In December, an Integrated Food Security Phase Classification report estimated that 25 percent of civilians in northern Gaza were suffering catastrophic levels of acute food insecurity.Footnote 69 By March 2024, that estimate was 55 percent, with 69 percent of all Gazans suffering emergency (39 percent) or catastrophe (30 percent) levels of food insecurity.Footnote 70 In March and April, access was expanded, particularly to northern Gaza,Footnote 71 improving the numbers.Footnote 72 However, even then, the Famine Review Committee warned of an enduring “high and sustained risk of Famine across the whole Gaza Strip.”Footnote 73 The Rafah offensive and expanded Israeli operations around purported humanitarian zones brought further significant declines in humanitarian access and resurgent malnutrition.Footnote 74

The ICJ recently affirmed that notwithstanding its military withdrawal in 2005, Israel retained law of occupation obligations in Gaza “commensurate” with its enduring control—“even more so” since October 7, 2023.Footnote 75 One of the clearest “commensurate” obligations, given Israel's relevant control is to “ensur[e] the food and medical suppl[y]” (including water) of the civilian population in Gaza to “the fullest extent of the means available to it,” including by “bring[ing] in” those supplies “if the resources of the occupied territory are inadequate.”Footnote 76 It is hard to see how Israel's aforementioned practices could be reconciled with these duties. Given the siege, however, most commentary has focused instead on the starvation war crime, often revealing confusion about proscribed intent.

IHL does not prohibit sieges per se. A belligerent may besiege to fix, hold, and deny military supply, and may inspect humanitarian consignments, while controlling their times and routes.Footnote 77 Furthermore, genuinely incidental deprivation, such as when food is the collateral damage of a strike on a military objective, implicates proportionality, not the starvation ban. But when is starvation intentional and therefore prohibited?

Some observers argue that the war crime obtains only when “the individual acted with the conscious objective of producing the prohibited result, in this context starvation of civilians,” a purpose they decline to attribute to Israeli officials.Footnote 78 On this view, prohibiting belligerents from knowingly causing civilian starvation “without an actuating illicit purpose would impose an unrealistic demand on war fighters.”Footnote 79 Sean Watts has warned that limiting “intentional” starvation to acting with the purpose of causing civilians to suffer fatal or near-fatal malnutrition, “reduces the rule's humanitarian effect, perhaps to the vanishing point.”Footnote 80 He nevertheless argues that military necessity precludes an interpretation that would ban siege starvation in contexts of civilian-populated encirclements.Footnote 81 We disagree.

To insist that military necessity demands permitting siege deprivation, even if it implies knowingly starving the civilian population, is to turn three foundational principles on their heads. First, per IHL's “basic rule,” belligerents must distinguish “in all military operations” between combatants and the civilian population, directing military operations solely at the former.Footnote 82 A starvation siege is plainly a “military operation.” Second, a predominantly civilian population does not lose its civilian character due to the presence of combatants within it.Footnote 83 Third, a besieging party cannot recharacterize an operation directed against such a population as lawful simply by warning or allowing civilians to leave (e.g., from northern to southern Gaza). Those who eschew, or cannot take, that chance do not thereby “participate directly in hostilities”—the only threshold for losing IHL's civilian protection.

Over 98 percent civilian, Gaza's population is a civilian population by any measure.Footnote 84 So is the population of northern Gaza, site of the most severe deprivation.Footnote 85 Denying sustenance to either of these areas entails directing sustenance denial against a civilian population, even if the goal is to squeeze militants within that population. When the (only) means to starve militants is deliberately starving the civilian population, the lawful ultimate goal cannot authorize the unlawful means any more than a kinetic attack against a civilian population can be justified with reference to the ultimate goal of eliminating combatants embedded within that population.Footnote 86 The latter bombardment would constitute a clear war crime and likely crime against humanity.Footnote 87 Mass deprivation is no more permissible.

Moreover, the starvation prohibition is underpinned by a specialized IHL framework on objects indispensable to survival (OIS). Unlike dual-use objects generally, which are widely thought to be military objectives, OIS are protected against being the object of attack, destruction, removal, or rendering useless: (1) for their sustenance value, including their sustenance value to combatants, unless only combatants draw sustenance from them; and (2) for any other military reason, if such deprivation “may be expected” to leave civilians starving or forced to move.Footnote 88 As explained elsewhere, these safeguards are best understood as constitutive of the IHL starvation ban, which applies to all modalities of deprivation, including deprivation by impeding humanitarian relief.Footnote 89 Complementary rules preclude arbitrarily denying humanitarian access to populations in need.Footnote 90 Thus understood, the IHL starvation ban covers the intentional (“methodical”) deprivation of OIS either: (1) with the purpose of denying their sustenance value to a population that qualifies as a civilian population in aggregate (including denying sustenance to the civilian population as the predicate purpose to squeezing embedded enemy forces); or (2) for any other military reason when that deprivation may be expected to leave civilians starving.

Building on this IHL foundation and the ICC Statute's inclusion of both direct and oblique intent, the war crime of intentionally starving civilians as a method of warfare is best understood to entail the deliberate deprivation of OIS, either with the direct intent of denying sustenance to a civilian population, or with the oblique intent of knowing that civilians will starve.Footnote 91 At writing, the ICC chief prosecutor is seeking arrest warrants for Defense Minister Gallant and Prime Minister Netanyahu for starvation and related war crimes and crimes against humanity.Footnote 92 In this case, the Court has the opportunity to set a precedent in which the criminal intent threshold is communicated definitively. Critically, the ICC threshold should not be inaptly transposed to ex ante and concurrent legal assessments, which must incorporate prohibitions on acts of deprivation that may be expected to cause starvation or forced movement, arbitrary denials of humanitarian access, and the law-of-occupation duty to ensure food and medical supply.Footnote 93 As elaborated below, ICJ provisional measures offer essential resources for third states evaluating compliance with these rules.

C. The Genocide Allegation and Three Questions of Intent

It is uncontested that genocide, both as an individual criminal act and as a state act, hinges on the special intent to destroy in whole or in part a protected group. Yet, three doctrinal questions about intent underpin polarized reactions to South Africa's allegation that Israel is violating the Genocide Convention in Gaza.

First, what is the legal significance of committing acts enumerated in the Convention in the knowledge that they substantially risk (partial) group destruction? The special intent that characterizes genocide is generally understood as direct.Footnote 94 International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR)Footnote 95 and ICTYFootnote 96 jurisprudence, as well as the drafting history of the Genocide Convention, confirm that prohibited acts must be carried out “with the aim, purpose or desire to destroy a group” in whole or in part.Footnote 97 Knowledge of the genocidal intent and actions of others may suffice for secondary liability, but the underlying genocide must be perpetrated with special purposive intent.Footnote 98 The notion that knowing or reckless group destruction could ground principal individual criminal responsibility for genocide remains a minority scholarly position.Footnote 99 But does the prevailing consensus regarding intent as defined for accountability entail that the Genocide Convention neither bears on conduct that poses a substantial risk of (partial) group destruction, nor informs third-party evaluation of such conduct, unless (partial) group destruction is also evidently its purpose?

In Gaza, the question looms large. Responding to South Africa's application under the Genocide Convention, the ICJ has, to date, thrice indicated provisional measures. In January 2024, the Court determined that “there [was] a real and imminent risk that irreparable prejudice [would] be caused to the rights [of the Palestinians in Gaza].” Footnote 100 What rights? “[T]he right[s] . . . to be protected from acts of genocide and related prohibited acts mentioned in Article III [of the Genocide Convention].”Footnote 101 The Court then ordered Israel to prevent violations of the Convention, punish incitement, and “enable the provision of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance.”Footnote 102 It did not, as South Africa requested, order Israel to halt hostilities. In March, the Court ordered Israel to “ensure, without delay, in full co-operation with the United Nations, the unhindered provision at scale by all concerned of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance.”Footnote 103 Two months later, the Court demanded that Israel “[i]mmediately halt its military offensive, and any other action in the Rafah governorate, which may inflict on the Palestinian group in Gaza conditions of life that could bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”Footnote 104

Although the first order recalled statements by Israeli officials that may be probative of intent,Footnote 105 the Court has not explicitly grappled with whether Israel's conduct can plausibly be seen as purposively bringing about the destruction of Palestinians in Gaza. This has led some to demand “not to read any substantive conclusions”Footnote 106 regarding genocide into its orders.Footnote 107 Others, including one of us,Footnote 108 have pointed out that ordering provisional measures means finding that Israel's actions in Gaza pose “a real and imminent risk”Footnote 109 of whole or partial group destruction. For instance, in the third order, the “Court finds that the current situation arising from Israel's military offensive in Rafah entails a further risk of irreparable prejudice to the plausible rights claimed by South Africa,” namely the Palestinians’ rights under the Genocide Convention.Footnote 110 As the orders have become more demanding, the Court appears to have tightened the link between its demands and Israel's primary obligations relating to genocide.Footnote 111

One way to read the orders assumes that the Convention rights that the Court seeks to safeguard are rights to be protected from prohibited acts carried out with special intent. On this reading, the Court deemed, for instance, Israel's offensive operations in Rafah to pose a real and imminent risk of genocide (with purposive intent). An alternative reading is that the Court put Israeli officials on notice that continuing with the identified conduct amounts to recklessly, and potentially knowingly, destroying a protected group in whole or in part because a “real and imminent risk” is an objective and substantial risk. On this view, although accountability under the Genocide Convention turns on purposive intent, the Convention (and the framework for provisional measures) should be understood ex ante as guiding states not to engage in enumerated acts that pose a substantial risk to the survival of a protected group because doing so carries a risk of genocide. Supporting the second interpretation, in The Gambia v. Myanmar, the ICJ did “not consider that the exceptional gravity of the allegations is a decisive factor warranting . . . the determination, at the present stage of the proceedings [provisional measures], of the existence of a genocidal intent.”Footnote 112

To be clear, this interpretation implies that the Court bracketed intent in inferring a risk that genocide is or will be occurring, not in the substantive definition of genocide. This approach arguably secures international law's functionality ex ante and in real time. Purposive intent is held in the first instance by individuals, is exceedingly difficult to detect, and can often only be established, if at all, ex post. Meanwhile, states generally have a duty to prevent genocide when there is a “serious risk” it will be committed.Footnote 113 When individual officials adopt a plan or carry out acts that pose a substantial risk of whole or partial group destruction, an ex ante functional law might therefore guide the state in whose name these officials act to put a stop to their conduct even while their intent remains obscure (thus requiring a form of auto-prevention). At the accountability stage, the ICJ will only find Israel responsible for violations of the Genocide Convention (preventive or direct) if it establishes that relevant acts were committed with special purposive intent.

For concurrent third-party evaluation, such a functionally differentiated interpretation is more established: any state conduct that poses a risk of group-destruction (regardless of intent) logically poses “a serious risk that genocide will be committed,” which incontestably triggers third states’ prevention duties. Footnote 114 And yet, a state that has violated this prevention duty ex ante will not incur responsibility if the genocide risk does not materialize.Footnote 115 This opens a response to the concern that South Africa used the Convention's compromissory clause to litigate IHL violations in a court without IHL jurisdiction in this conflict.Footnote 116 If IHL violations are so widespread as to pose a risk of group destruction, then even if South Africa were unsure of the attributability of genocidal intent to Israel, its request that the Court consider a genocide allegation would be appropriate to genocide prevention.

A second doctrinal question underlying polarized assessments of the genocide allegation is how to distinguish direct (purposive) intent from desire, ultimate goal, and motive.Footnote 117 Judge Nolte, on occasion of the first order, declared himself “not persuaded”Footnote 118 that South Africa had established genocidal intent, pointing instead to “the stated purpose of [Israel's] operation, namely to ‘destroy Hamas’ and to liberate the hostages.”Footnote 119 Yet, those aims are not dispositive. If the destruction of Palestinians in Gaza as a protected group in whole or in part were the means by which Israel sought to achieve its ultimate goal of security, group destruction would be the predicate purpose, pursued with direct intent.Footnote 120 This construction also exemplifies the possibility that one can act purposively in relation to conduct or an outcome despite lamenting it. Whether in relation to targeting, starvation, or genocide, neither the fact of a permissible ultimate goal nor the lamentation of what was deemed necessary to achieve it would warrant recharacterizing that predicate action as anything other than directly intended.Footnote 121 Ultimately, the ICJ will need to evaluate whether total or partial group destruction was a purpose of an enumerated act, not whether it was pursued enthusiastically or as an end in itself.

A third question is what it means for a state to act with genocidal intent, as distinct from failing to prevent or punish individuals who perpetrate genocide.Footnote 122 The least contestable basis for “genocidal” state intent would be a “concerted plan” among government leaders.Footnote 123 In the current context, this would have to be a policy developed by Israel's Security Cabinet or some other leadership group. However, even if such a plan existed, proving it would be very difficult. Often, intent must instead be inferred from a consistent pattern of state conduct, either as evidence of the plan, or as the manifestation of a form of collective intent, whether or not defined centrally.Footnote 124 Absent a concerted plan or a pattern of state conduct leaving no reasonable inference other than the presence of genocidal intent, is it possible to speak of “the intent of a state?”

Uncontroversially, when a state official acts (even ultra vires) in their official capacity, that act is attributable to the state.Footnote 125 The individual's conduct is, legally speaking, state conduct. But when a composite act involves the conduct of multiple state officials, each acting in their official capacity, but with different intentions, which of those intentions is properly understood to be the state's? Can the state be said to hold each official's intent simultaneously, such that the unlawful intent of any entails the unlawful intent of the state vis-à-vis the collective act? In extremis, that could mean attributing genocidal intent to Israel based on the group-destructive intent of an IDF soldier engaged in criminal killings (an enumerated genocidal act).Footnote 126 That strikes us as implausible.Footnote 127 Alternatively, does the individual's control over the collective action determine the attributability of their intent to the state as it relates to that action, such that leaders’ statements are uniquely important?Footnote 128 It warrants mention that state responsibility generally does not require establishing state intent, which may explain why these issues have yet to be fully resolved.Footnote 129

II. Courts’ Provisional Products and Real-Time Evaluation

In Gaza, international courts’ profile as focal points for public engagement with international law is striking. What does this mean for law's capacity to discharge its three functions?

Courts operate primarily as institutions of accountability.Footnote 130 Applying law to established facts, they are meant to determine with finality whether a subject violated its obligations in a particular case. In addition to resolving disputes and endeavoring to dispense justice,Footnote 131 their decisions contribute to international law's development, as “subsidiary means” for its ascertainment,Footnote 132 including in ways that ultimately guide action and third-party evaluation. However, the latter process occurs ordinarily through the jurisprudential impact of courts’ final judgments. Whether those entail declaratory, reparative, or punitive accountability, the procedural ideal of the rule of law demands a process that is measured in years. The two previous genocide cases to reach full merits judgments at the ICJ took well over a decade from initiation to judgment. Plainly, courts’ capacity to contribute directly through these judgements to ex ante action-guidance (e.g., via specific deterrence) or to concurrent third-party evaluation is limited.

Issued on a shorter time horizon, courts’ provisional products may offer a more direct mechanism through which to discharge law's functions during armed conflict. Although the ICJ's “real-time” involvement is not unique to this conflict,Footnote 133 its provisional products relating to Gaza have received more attention than most of its final judgments elsewhere, adding urgency to clarifying their significance for action-guidance and third-party evaluation.

Uncontroversially, the ICJ's provisional measures orders bind the litigating parties,Footnote 134 though compliance is generally “unsatisfactory,”Footnote 135 including, observers argue, in the case at hand.Footnote 136 However, a potentially consequential (yet untested) question in a system of decentralized enforcement, is what courts’ provisional products mean for third states. Below, we discuss both the possibility of third states’ complicity in provisional measures violations (II.A), and provisional measures’ potential significance for third states’ discharging their pre-existing obligations regarding genocide (II.B) and IHL (II.C).

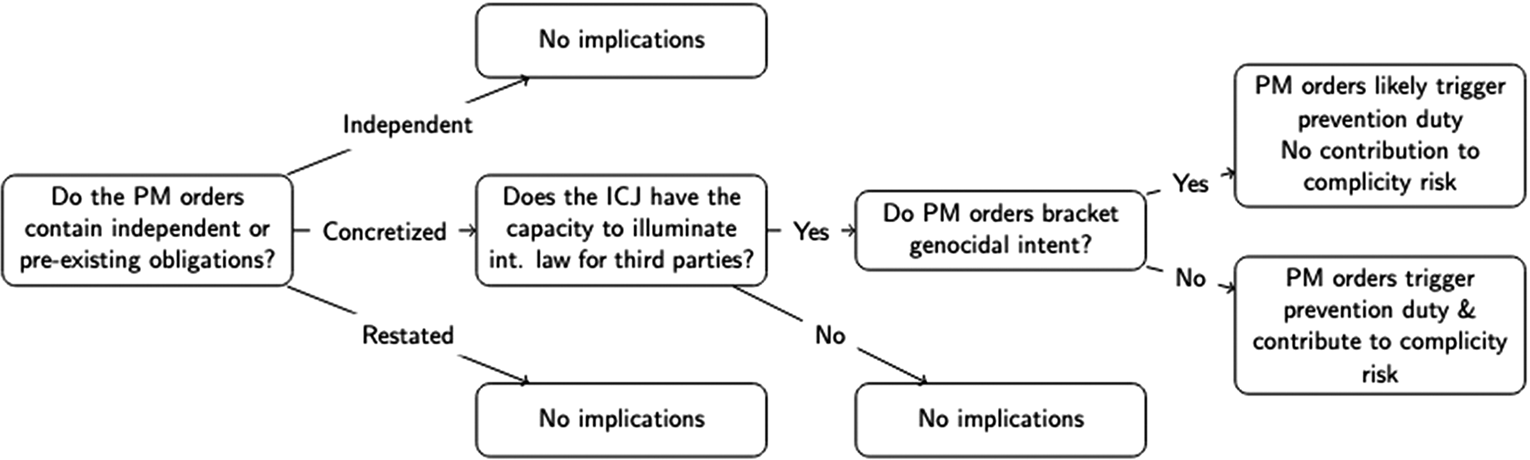

A. Provisional Measures and ARSIWA Complicity

When the addressee of a provisional measures order does not comply (hereinafter PM-breach), it incurs state responsibility for an internationally wrongful act.Footnote 137 There is reason to believe that Israel has failed that obligation.Footnote 138 If it has, per Article 16 of the International Law Commission's (ILC's) Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA), it would seem to follow that third states could be complicit if they contribute significantly to that breach, “with knowledge of the circumstances of the internationally wrongful act.”Footnote 139 However, before drawing that conclusion, two doctrinal questions must be addressed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ICJ Provisional Measures Orders & Secondary ARSIWA Responsibility

Example: State A assists Israel in breaching an ICJ Provisional Measures Order, for instance, by sending weapons to be used in a Rafah offensive that threatens Palestinians’ rights under the Genocide Convention. Does State A incur secondary responsibility for assisting in an internationally wrongful act under Article 16 ARSIWA?

First, must a state assist purposively in a PM-breach or does knowledge suffice for complicity? Confusing the otherwise straightforward use of “knowledge” in Article 16, the ILC Commentary indicates that the contribution must have been made “with a view to facilitating the commission” of the wrongful act.Footnote 140 The latter implies a purpose element that would be difficult to establish, and would exceed the parallel criminal intent standard for complicity.Footnote 141 Meanwhile, the Commentary's separate discussion of jus cogens violations is framed in terms of the Article 16 threshold with reference only to knowledge, not purpose. Footnote 142 In assessing complicity in the Bosnian genocide case, the ICJ focused exclusively on knowledge, albeit without ruling out that purpose may also have been necessary.Footnote 143 Notably, the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) absolutely prohibits authorizing arms transfers in the “knowledge” that they would be used to commit genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes.Footnote 144

Second, is a PM-breach the kind of wrongful act that can underpin ARSIWA complicity? Article 16 responsibility attaches only to acts that “would be internationally wrongful if committed by [the assisting] State”—hereinafter the “mutual obligation” requirement. There are two ways of reading this qualification, one contingent on the primary rule's actual reach and one counterfactual.

On the more restrictive interpretation of Article 16, complicity would depend on the actual reach of the underlying primary obligation. In support, the Commentary describes third-party responsibility as turning on whether the assisted act breaches “obligations by which the aiding or assisting State is itself bound.”Footnote 145 That would not include assisting a PM-breach as such, as ICJ decisions bind only the litigating parties.Footnote 146 As a general matter, this interpretation could create potentially dangerous gaps. For instance, the territoriality of many human rights obligations risks implausibly precluding complicity in their violation, even across parties to the same treaty, as only the principal (territorial) state would bear the relevant obligations to those whose rights are violated.Footnote 147

The counterfactual approach meanwhile asks whether the assisting state would bear those obligations if it were engaged in the conduct of the principal state, in the latter's circumstances, but given its own legal commitments. In support, the Commentary states that third party responsibility obtains if “the conduct in question, if attributable to the assisting State, would have constituted a breach of its own international obligations.”Footnote 148 In addition to grounding third-party complicity in human rights violations, this approach arguably entails that complicity in a PM-breach—for instance through weapons transfers supporting offensive operations in Rafah that threaten Palestinians’ rights under the Genocide Convention—would hinge on whether the assisting state, if it were in Israel's position in terms of conduct and circumstances, would be bound by the relevant orders. For states that have accepted the ICJ's Genocide Convention jurisdiction, this counterfactual approach could imply that materially and knowingly assisting a PM-breach would implicate Article 16.Footnote 149

If the counterfactual approach prevails, states may incur secondary ARSIWA responsibility for assisting a PM-breach as such. Even if the more restrictive interpretation prevails, an assisting third state could still incur responsibility if the order relayed an underlying obligation shared by both states and the PM-breach would, by implication, also breach that underlying obligation.Footnote 150 We turn to that possibility next.

B. Provisional Measures and Genocide Complicity and Prevention

Ordering provisional measures, the ICJ can either create new independent obligations, or relate pre-existing obligations (see Figure 2). Footnote 151 In the latter case, PM orders could inform how states that share these pre-existing obligations must discharge them. Do the Gaza PM orders for instance bear on third states’ risk of complicity in genocide (rather than complicity in any PM-breach)? The ICJ's third order demanded, among other things, that Israel: “Immediately halt its military offensive, and any other action in the Rafah Governorate, which may inflict on the Palestinian group in Gaza conditions of life that could bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”Footnote 152 As an independent obligation to halt a specific military operation in a specific context, this demand would not bear on how third states discharge their obligations under the Genocide Convention. But that the order created an independent obligation is debatable.

Figure 2: ICJ Provisional Measures Orders & Genocide Complicity/Prevention

Note: Do the ICJ orders in South Africa v. Israel affect the epistemic environment in which third states discharge their obligations under the Genocide Convention?

Judge ad hoc Barak in his Dissenting Opinion interpreted the “halt” order as merely “reaffirming” Israel's prior obligation not to violate the Genocide Convention. The order indeed demands several times that Israel must act “in conformity with its obligations under the Convention.”Footnote 153 Barak states that “even without an order issued by the Court, a military offensive that may result in a violation of a State's obligations under the Genocide Convention would have to stop.”Footnote 154 By attaching the order's “halt” requirement to pre-existing obligations, Barak's interpretation supports the notion that the order could in principle have implications for third states assisting Israel in offensive operations in Rafah. However, for him, the Court's order amounted to a redundant restatement of the law—the “halt” requirement conditional on whether the offensive in fact would violate the Genocide Convention, which third states would have to determine for themselves when assessing their complicity risk.

A third interpretation of the order is that the Court concretized a pre-existing obligation not to engage in military operations “which may inflict on the Palestinian group in Gaza conditions of life that could bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part,” and identified the Rafah offensive as such an operation.Footnote 155 If this is correct, then, actualizing law's ex ante function, the ICJ's order arguably specified Israel's pre-existing obligations into an action-guiding demand to halt offensive operations in Rafah. That demand would not itself bind third states. However, might the concretization of Israel's duties inform third states that share the obligation under the Genocide Convention?

Here the question arises whether the ICJ has the capacity to illuminate how states not directly bound by its pronouncements must discharge their existing international obligations in a specific context. We believe so. Although not a specialized factfinder, the ICJ has distinct epistemic advantages that warrant presumptive deference, most obviously because it is presented with available evidence by competing litigants, including the evidence most favorable to the party against which a decision is issued. Moreover, as manifest in its advisory opinions, the ICJ has a general competence to apply and concretize international law in an authoritative, if non-binding, way.Footnote 156

Of course, to the extent that an order's relevance for third-party evaluation and response hinges on its role in concretizing pre-existing obligations, its usefulness depends on its determinacy. Ambiguity, while “constructive” in building consensus, weakens action-guidance and epistemic value for third-party evaluation.Footnote 157 Recall here the contestability of whether the Court identified a risk to Palestinians’ rights not to be harmed by Israel with genocidal intent or whether it diagnosed a risk of group destruction, while bracketing intent. At the accountability stage, where Article 16 operates, the Court has identified knowledge of genocidal intent as a condition of complicity.Footnote 158 If the ICJ's provisional measures orders have bracketed intent, their epistemic value to third states to assess their complicity-risk is limited. Conversely, if the Court has identified a real risk of genocidal intent through its orders, this would be an important, though not sufficient, contribution to third states’ knowledge of that intent.

A state's duty to prevent genocide, meanwhile, is implicated when it “was aware, or should normally have been aware, of the serious danger that acts of genocide would be committed.”Footnote 159 If the Court's orders implied a risk that Israel is acting with special intent (because Palestinians’ rights under the Genocide Convention are rights not to be harmed with special intent), the orders incontestably implicate third states’ prevention duties. The latter “arise at the instant that the State learns of, or should normally have learned of, the existence of a serious risk that genocide will be committed,”Footnote 160 so by January 26, 2024.Footnote 161 On the alternative interpretation, the Court bracketed special intent and declared that Israel's actions, specifically continued deprivation (second and third order) and the military offensive in Rafah (third order), risk group destruction. Here, although the implications for third states’ duties are, in principle, more contestable, we suggest they remain significant. Why?

The intent-bracketing reading of the orders indicates that the Court deemed it appropriate to cast an objective risk of group destruction (possibly without genocidal intent) as a risk of irreparable prejudice to the Palestinians’ rights under the Genocide Convention. As argued above, this could itself be framed in terms of functional differentiation, with the Court—at the provisional measures stage—acting in the paradigm of action guidance, not accountability. Third states’ obligation to prevent genocide arguably operates in a similar paradigm, geared toward the same purpose of preventing irreparable prejudice to the right not to be subjected to group destruction through violations of the Genocide Convention. A teleological interpretation might therefore indicate that facts that trigger provisional measures also trigger third states’ preventive obligations. Just as provisional measures orders do not prejudge the merits, a third state may fail to act preventively as required by the Genocide Convention, and yet, by chance, avoid a violation at the accountability stage, where state responsibility even for a preventive failure would materialize only if the principal “actually committed” genocide, with the requisite intent.Footnote 162

Of course, genocide lends itself to “bracketing” intent in real-time evaluation. As the underlying conduct would ordinarily be illegal (likely criminal) absent genocidal intent, the risk that low-threshold third-state prevention duties (or PM orders) would undermine lawful action is minimal. Whether a similar bracketing of intent in service of functional differentiation could work in shaping third-state duties vis-à-vis principal-state conduct that is closer to the line of legality may be contested. And yet third-state duties to avoid the risk of contributing to violations are more broadly applicable in war. We next turn to another set of obligations for which the ICJ's provisional measures could modify third states’ epistemic environment.

C. Provisional Measures and Third States’ Obligations Under IHL

States have an obligation “to ensure respect” for IHL under Common Article 1 of the Geneva Conventions and customary law. Per the updated ICRC Commentary, this requires states “to refrain from transferring weapons if there is an expectation, based on facts or knowledge of past patterns, that such weapons would be used to violate the Conventions.”Footnote 163 In a similar vein, parties to the Arms Trade Treaty may not transfer weapons that “could facilitate” a serious IHL or human rights violation if, following mitigating measures (or the consideration thereof), an “overriding risk” of such violation remains.Footnote 164 The question in relation to the ICJ's orders is whether “a real and imminent risk” to rights protected under the Genocide Convention (the provisional measures threshold) implies a “clear” or “overriding” risk of IHL violations (see Figure 3).Footnote 165 The rules are primarily action-guiding and have been invoked in multiple tranches of ongoing litigation across several states not for the purpose of accountability, but to stop arms transfers.Footnote 166

Figure 3: ICJ Provisional Measures Orders & Third States’ Obligations Under IHL

Note: Provided the ICJ has the capacity to illuminate international law for third parties, do the ICJ orders in South Africa v. Israel affect the epistemic environment in which third states discharge their primary obligation to ensure respect for IHL and obligations under the Arms Trade Treaty?

Is it possible that IHL-compliant acts may pose a real and imminent risk of genocide or group destruction? This claim may be likely to be invoked in conjunction with a charge that the adversary inflates that risk through the systematic use of human shields. Although it is conceivable in theory that perpetrators act with the purpose to destroy a group but (1) direct their efforts only against group members who are targetable under IHL, or (2) pursue that end through IHL-compliant conduct in densely populated areas,Footnote 167 an IHL-compliant genocide, including the genocidal intent implied in the first interpretation of the orders, is difficult to credit as a practical possibility. In Gaza, ICJ orders related not anomalous scenarios of genocidal purpose with little impact on the protected group. Instead, the Court diagnosed a risk to Palestinians’ rights under the Genocide Convention due to “famine and starvation,”Footnote 168 “the forcible displacement of the vast majority of the population, and extensive damage to civilian infrastructure.”Footnote 169

Even on the second interpretation, according to which the ICJ bracketed intent and “merely” diagnosed a real and imminent risk of partial or whole group destruction, the orders have clear implications for third states’ duties under Common Article 1 and the Arms Trade Treaty: grave IHL violations, such as starvation, indiscriminate attacks, and forcible displacement, are the non-contingent reality of threats to the survival of protected groups in war.Footnote 170 As states grapple with how to evaluate an armed conflict in real time, it would violate their due diligence duties to ignore the systematic connections between group destruction, genocide, and violations of IHL for the sake of honoring either (1) the doctrinal possibility that violations of the Genocide Convention do not also violate the Geneva Conventions or (2) the empirical possibility that Israel poses “a real and imminent risk” of (partial) destruction to the Palestinians in Gaza without violating IHL. In this overtly action-guiding aspect of international law, the ICJ's orders provide a key focal point for third-state evaluation and response.

Conclusion

Current developments in Gaza, where Israel's systematic compliance claim collides with catastrophic civilian harm, create doctrinal pressure on concepts and frameworks that permit international law to discharge its ex ante action-guiding and concurrent evaluative functions. Establishing belligerent intent is a critical, but misunderstood, challenge. Where available, courts’ provisional products can provide a key epistemic resource in real-time legal assessments of war.

Concretely, we argued that doctrinal confusion obscures prohibited intent in Israel's conduct of hostilities and siege. The relevant violations do not require purposively bringing about prohibited consequences such as dead or starved civilians. When not unduly shaped by standards developed for law's accountability function, an application of lex lata in real time demands that Israel change course and third states suspend material assistance. Notably, UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy recently distinguished his government's decision to suspend the licensing of certain arms exports to Israel from the future accountability work of international courts.Footnote 171 Meanwhile, the ICJ's provisional orders contribute critically to third states’ awareness of risks sufficient to trigger their IHL obligation to act now rather than defer to law's accountability function.

Regarding the allegation of genocide, developments in Gaza spotlight doctrinal questions that should be resolved with due regard to differentiating accountability from action-guidance and concurrent evaluation. Specifically, we argued that before and during a risk of (partial) group destruction, bracketing genocidal intent in the inference of a genocide risk may be appropriate when the ICJ issues provisional measures, the primary state evaluates its own officials’ conduct, and third states discharge their prevention duty. Direct intent is exceedingly difficult to infer in real time. Law's functionality in inhibiting wrongful conduct must not be sacrificed for standards developed to safeguard due process and track blameworthiness in law's accountability function. In some legal contexts, lowering inferential (or substantive) intent standards ex ante may carry the risk that an agent is inhibited or unsupported in what would be legally permissible (morally desirable) conduct. This is not the case when conduct poses a real and imminent risk of group destruction.

Finally, we argued that ICJ provisional measures can in principle clarify the ex ante and concurrent obligations of parties not directly bound by them. However, several open doctrinal and interpretive questions condition the third-party implications of the South Africa v. Israel orders. One pervasive danger is that third parties—rather than drawing on provisional court orders as epistemic resources or seeking to undertake rigorous IHL risk assessments themselves—will rely instead on the perceived or imputed character of the belligerent. Current developments in Gaza show that this guarantees contradictory inferences and the functional infirmity of international law as a restraining force in real time. To presume that a party complies with international law, for instance because it is a democracy,Footnote 172 is not only to ignore the empirical record. It is also inimical to the idea of law and thus an existential threat to the primary mechanism available to limit the horrors of war and mass violence.