Within recent musicology, there has been a tendency, which I will address shortly, to view the performance practice of European serial music as sterile and lacking in performer agency. This stems, I would argue, from a monolithic conception of this practice in terms of the utopian rationalism of its earliest theorists, as well as a lack of engagement with the reality of actual performances. As M. J. Grant has made clear, belief in the possibility of structurally pure musical systems, realizable without the aid of a performer via electronic composition, was in fact extremely short-lived, as composers and theorists quickly came to realize the inherent irrationality of the technology at their disposal.Footnote 1 Chief among these was Karlheinz Stockhausen, who, having spent one and a half years working in the newly founded WDR electronic music studio in Cologne, returned to his principal instrument, the piano. As he explained in early 1955:

I have now taken to working on piano pieces at the same time [as electronic compositions] because the strictest forms of structural composition brought me up against essential musical phenomena that are not susceptible to measurement. This does not make them any the less palpable, detectable, imaginable and effective. I can (for the time being, at any rate) bring these things into play more clearly by using an instrument and a performer than in electronic composition. Primarily it is a matter of imparting a new way of feeling time in music, in which the infinitely subtle ‘irrational’ nuances and gestures of a good performer often produce what one wants better than any centimetre gauge. Statistical formal criteria such as these will give us a completely new and unprecedented angle on the question of instruments and their playing.Footnote 2

These comments coincide with what has been regarded as the end of the first phase of Darmstadt serialism,Footnote 3 whose music was predicated on a poised equilibrium of dynamic, registral, timbral, and rhythmic contrasts, dictated by strict parametric organization; the results were chiefly pointillistic, engendering a non-directional, immanent sense of form.Footnote 4 Furthermore, the majority of early serial music was written either for electronic media, or for piano, an instrument whose versatility and immediacy suited the demands of the composers. European serialism proper could thus be defined as parametrically composed music, dating from 1950 to the end of 1954, principally for electronic media, or one or two pianos, by composers who attended the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music.

It is this repertoire to which Nicholas Mathew implicitly refers in his discussion of ‘Darmstadt Pianism’: an approach to playing, supposedly prevalent at the 1950s Courses, involving a literal, one-to-one translation of the composer's instructions.Footnote 5 While principally concerned with the contemporaneous performance practice of Webern's Piano Variations (1936), Mathew begins the article by questioning the possibility of ‘historically informed Stockhausen performance’.Footnote 6 Taking Klavierstück V (1954) as his case study, he observes how the notation ‘appears to take a concern for textual exactness to its farthest possible limits without banishing the pianist altogether. We find ourselves on the eve of the performer's vanishing, so to speak: for at first blush one might fairly ask what role a pianist can play here other than to become a function of the notation – a mechanical, if athletic, follower of orders; an organic tape player.’Footnote 7 He is particularly fixated on Stockhausen's instruction in the General Foreword for the pianist to depress keys for precisely the durations indicated;Footnote 8 interestingly, this is also a detail that Stuart Paul Duncan addresses in his critical appraisal of a style of playing associated more broadly with 1950s and 1960s Darmstadt, citing Stockhausen's comment in a later interview that when playing his music, ‘a note should not be shortened before the rest, but held exactly to the value that it is written’.Footnote 9 Duncan takes this as representative of the composer's ‘performative mentality’, arguing that ‘the technological advancements made during the 1950s, encouraged performers to view the score as a set of instructions that elicited accuracy in all domains (especially in the rhythmic domain)’,Footnote 10 and subsequently bundling Stockhausen's comments together with the more overtly authoritarian rhetoric of Milton Babbitt.Footnote 11 While Duncan's critique is made as a means of distinguishing the performance practice of early Darmstadt with that of New Complexity composers at the 1980s Summer Courses, and Mathew's as part of a broader attack on modernist performance aesthetics, both share a critical view of the perceived literalism and resultant sterility of a practice associated with European serial music and with Stockhausen in particular.

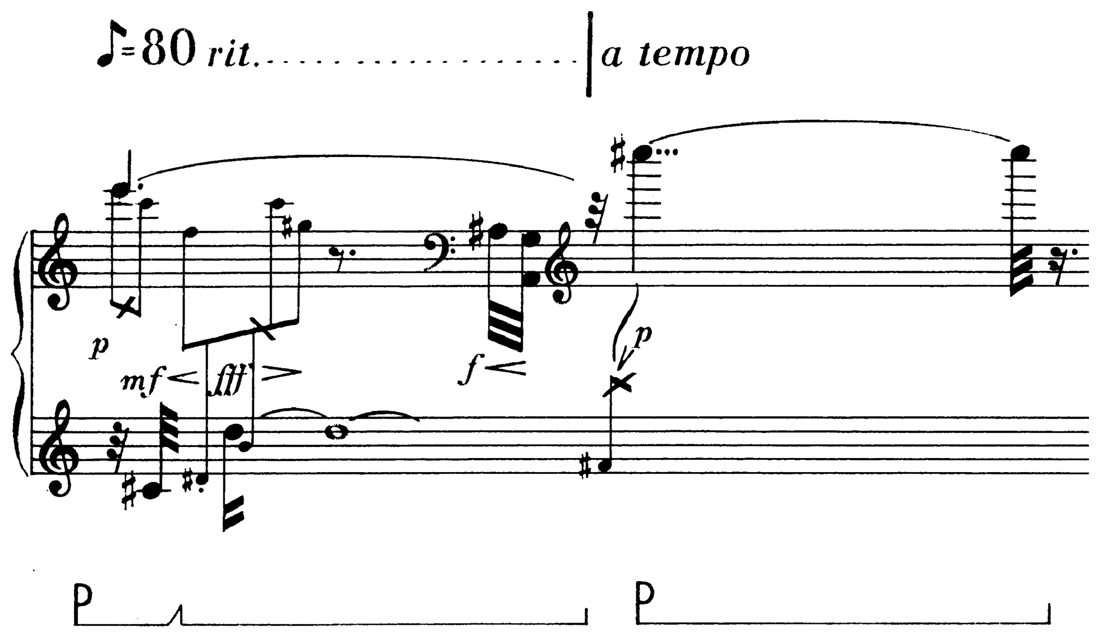

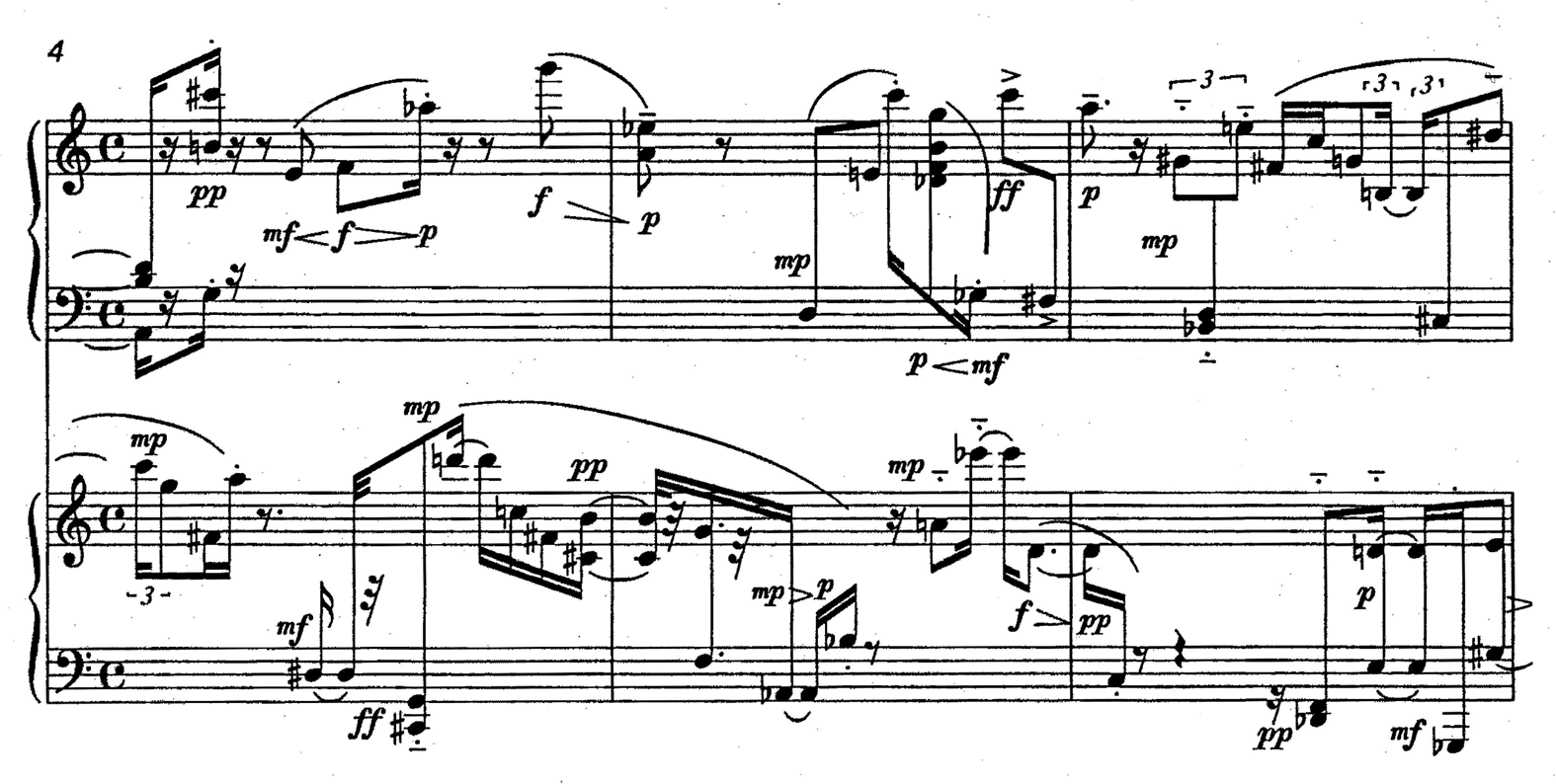

These critiques both suffer from a lack of proper engagement with the affordances of serial scores; that is, what they tell the performer to do, what they tell the performer not to do, and which decisions are left open to interpretation.Footnote 12 For example, despite providing a reproduction of the first page of Klavierstück V (1954–5), Mathew ignores the complex temporal ambiguities of the opening grace-notes, interpolated with durational attacks under a ritardando marking (see Example 1), fixating instead on an instruction – with its likely roots in Stockhausen's own painstaking experience of controlling and shaping the ends of tones in the electronic studio – designed to foreground the temporal irrationality of less traditional aspects of the notation. Duncan, meanwhile, does not provide examples; nor does either author refer to recordings of serial music. Instead, Mathew cites Jean-Jaques Monod's 1951 recording of Webern's Variations,Footnote 13 in which he hears ‘a consistent, and consistently hard timbre: the color of colorlessness’, concluding that ‘this almost more than any other feature of the recording emblematizes the specious universality of Darmstadt pianism: like the grayness of 1960s brutalist architecture, its astringency and lack of variation imitates the appearance of objectivity, it adopts abstraction's tone of voice’.Footnote 14

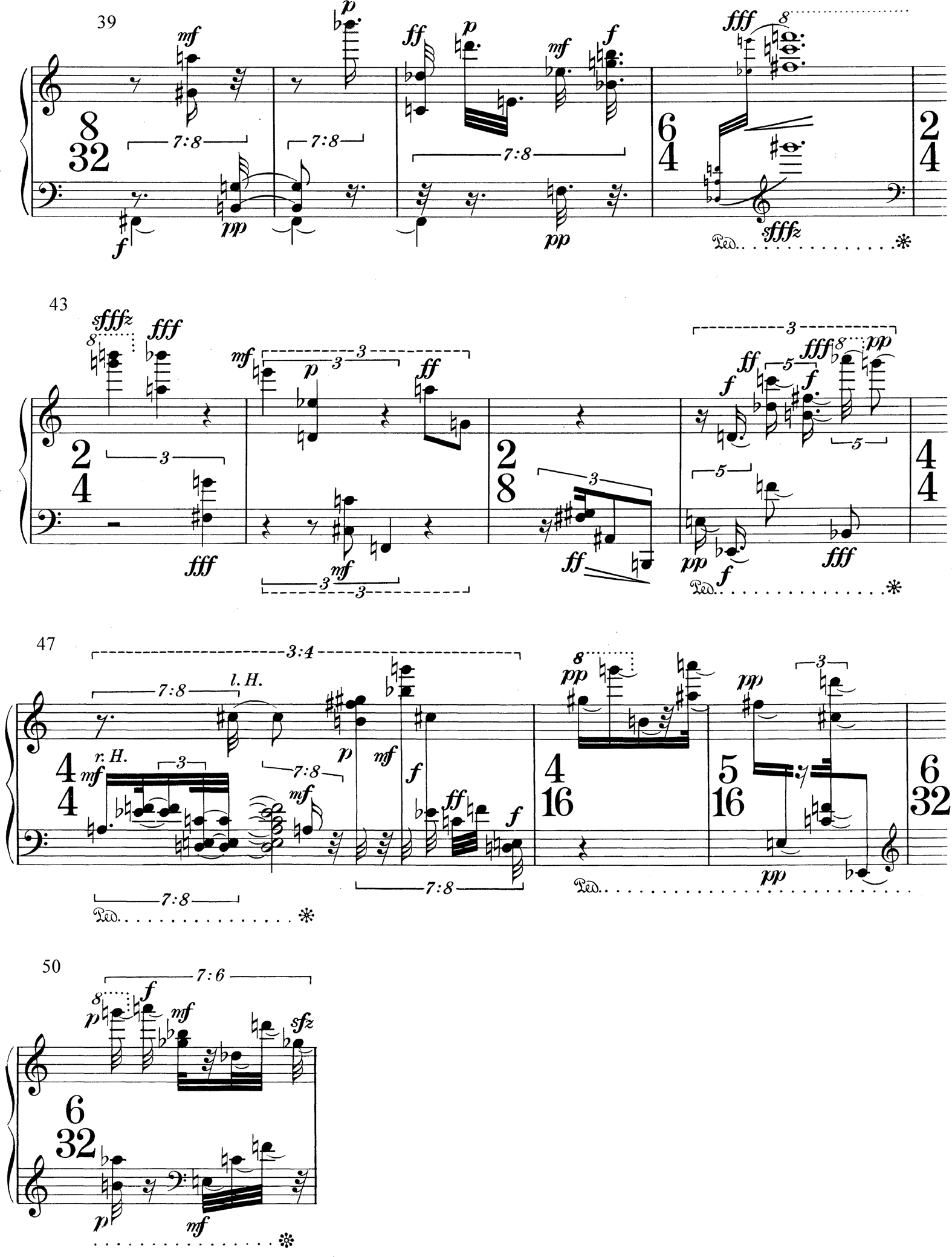

Example 1 Stockhausen, Klavierstück V, opening gestures. © Copyright 1965 by Universal Edition London (Ltd), London.

While Webern and the Variations in particular had a well-documented influence on composers at the 1950s Darmstadt Courses,Footnote 15 and the type of modernist objectivity that Mathew pejoratively describes in Monod's recording was certainly an established style of performance by the 1950s – though as Nicholas Cook has pointed out, by no means limited to Darmstadt – the performance affordances of Webern's skeletal yet in many ways traditionally expressive scores are fundamentally different from those of serial scores.Footnote 16 Through their self-consciously novel configurations, these scores did ultimately give rise to Stockhausen's ‘new and unprecedented angle on the question of instruments and their playing’, with far-reaching implications for the aesthetics of serialism and the practice of new music. To fully understand this development, I would argue, requires close analysis of the affordances of serial scores, and of their performances.

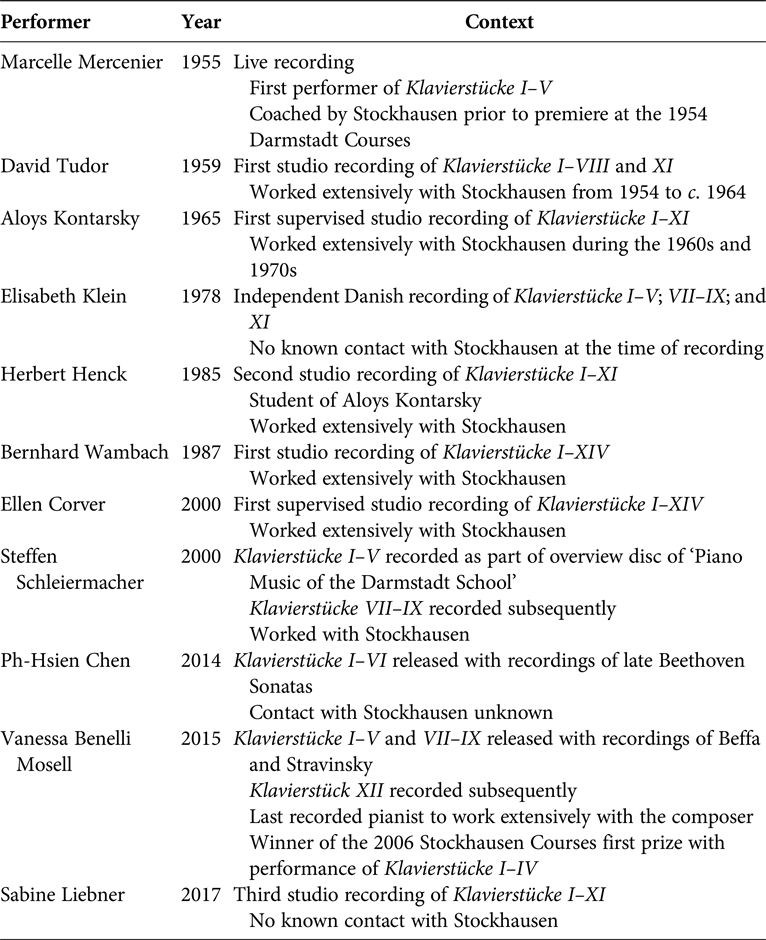

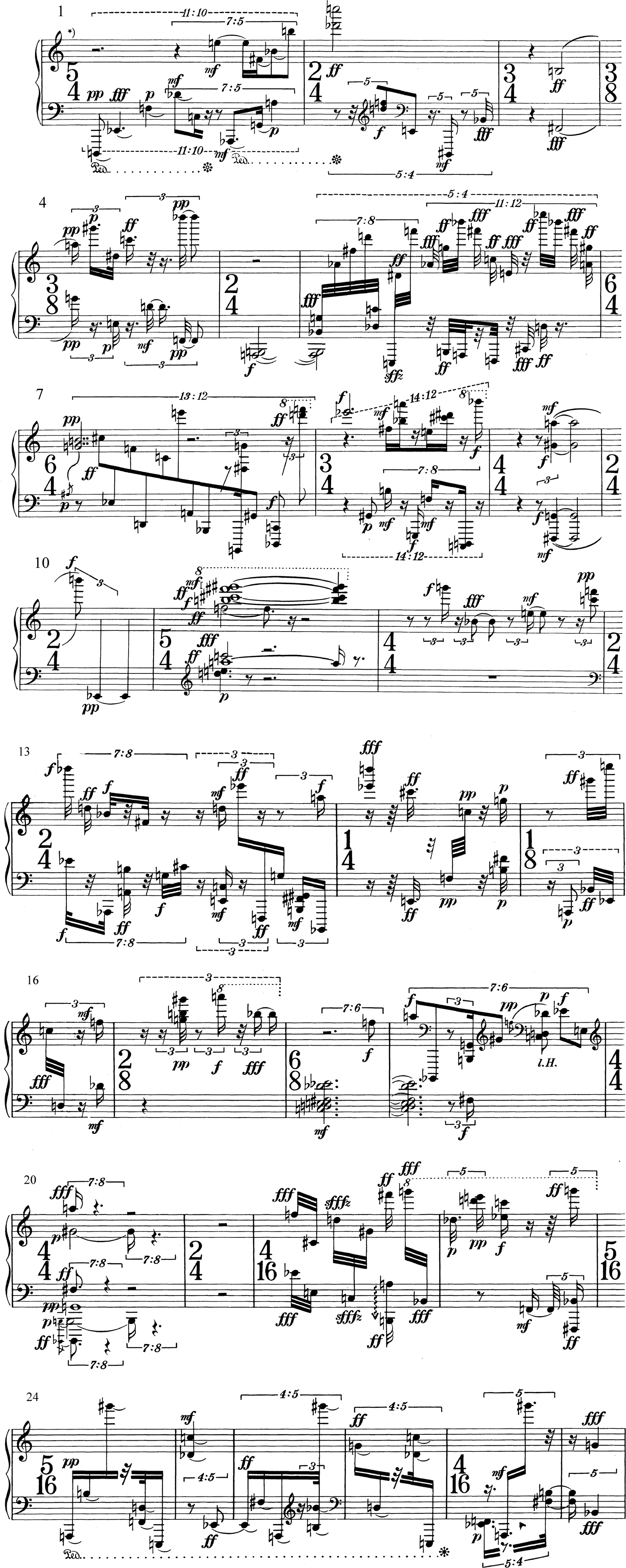

Stockhausen's Klavierstück I (1952–3) is chosen as the case study for this analysis for a number of reasons.Footnote 17 First, in light of its development alongside the composer's first electronic composition, the Konkrete Etüde (1952), produced at Pierre Schaeffer's electronic music studio in Paris,Footnote 18 it offers an insight into Stockhausen's state of mind with regard to the nascent dialectic of electronic and instrumental composition just prior to beginning work at the WDR studio; it also contains a number of experimental translations of electronic compositional principles with significant implications for the performer. Second, it marks an important step away from the punctual aesthetics of early serialism towards thinking in terms of groups,Footnote 19 while still preserving elements of punctualism; as such it can be viewed as a bridging piece in both serial composition and performance practice. Third, close inspection of the affordances of the score and the practice traditions that have emerged over the course of the piece's recording history reveal a hitherto unrecognized precedent for Stockhausen's use of grace-notes in the subsequent Klavierstücke, with implications for the development of his temporal theory. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, unlike much early serial music, Klavierstück I has continued to attract performers and audiences, with a significant body of recordings available for analysis, eleven of which were selected for this study (see Table 1 for contextual details; see discography for recording information).Footnote 20

Table 1 Selected recordings of Klavierstück I with contextual information

My analysis of these recordings in relation to the affordances of the score is used to provide evidence for Grant's influential reassessment of serial theory, to support and extend her vision of serial aesthetics, and to offer a practical basis for what she calls ‘serial listening’.Footnote 21 This latter concept remains underdeveloped in her book, chiefly, and similarly to Mathew and Duncan, through lack of engagement with the affordances of serial scores and the actualities of performances. I maintain that it is a worthwhile concept, however, encouraging modes of aesthetic appreciation suited to the non-thematic principles and hermeneutic contexts of serial music. These contexts, which will later be used to frame the results of my performance analysis, include the tension between the fixed aesthetics of electronic composition and the dynamic aesthetics of live performance; the embodied response of the performer to defamiliarized musical material; the transcendent interpretation of ‘pure’ musical systems; and the traces of thematicism that linger in music founded on the fundamental relationships of sounds to one another.

What my study ultimately aims to address is the influence of individual interpretation on the quality of the serial aesthetic, and the presence of three principal styles of performance that have emerged over the course of the nearly seventy-year performance history of Klavierstück I; these I term the experimental, the analytical, and the classical, epitomized respectively by David Tudor in the 1950s, Herbert Henck in the 1980s, and Ellen Corver in the 1990s. While not mutually exclusive, these styles, in some ways indicative of Stockhausen's own changing musical tastes, bear differing relationships to the hermeneutic contexts listed previously, calling for differing modes of serial listening, which may in turn allow for serious judgements of value and taste by the listener. To fully understand these styles, however, first requires an understanding of the affordances of the score.

The interpretive affordances of Klavierstück I

Unlike Olivier Messiaen and Pierre Boulez, both of whom approached parametric composition for the piano as concert-standard pianists, Stockhausen's primary experience as a performer prior to composing Klavierstück I was as a lounge pianist and as an improviser of accompaniments for a magic show. This latter experience was particularly extensive, as Stockhausen toured Germany with Adrion the Conjuror from summer 1950 to the end of 1951, while working on early serial compositions including Kreuzspiel (1951).Footnote 22 As Michael Kurtz relates, ‘during these months there must have been strong conflicts within Stockhausen's music making: when improvising for Adrion he could let his intuition run free, achieving certain things he could never have written’.Footnote 23 This, I would argue, is an important, overlooked context for the originality and creativity of his piano writing in the early Klavierstücke and beyond.Footnote 24

It is also worth noting that Klavierstück I did not begin life as a compositional experiment, as in Messiaen's Mode de valeurs et d'intensités (1949), or as an exercise in stylistic negation, as in Boulez's Structures, livre I (1952), but rather as a Klavierstück: a piece written specifically for pianist and piano, in contradistinction to the fixed media of early electronic music.Footnote 25 Much of Klavierstück I is therefore idiomatic and physically satisfying to play, despite its reportedly brief period of composition.Footnote 26 This, together with its place in the over-arching Klavierstücke I–XI (1952–61),Footnote 27 has undoubtedly contributed to its popularity among performers. Certain aspects of the score, however, particularly those less critically translated from electronic music, remain problematic.

The most striking and infamous notational features of Klavierstück I are its so-called ‘irrational’ rhythms: complex, non-binary divisions of durational values (see, e.g., bb. 1–2 and 6–8 in Example 2).Footnote 28 These rhythms caused controversy on their first appearance, with Boulez among others criticizing their playability.Footnote 29 Maarten Quanten recognizes their origins in the proportional measurement of tape for the Konkrete Etüde, where ‘over-durations’ are divided into complex groups of ‘subordinate durations’, suggesting an interesting translation of Stockhausen's thinking for the two media.Footnote 30 However, it seem likely that the idea for this notation, and perhaps the origin of what is now more neutrally described as nested-tuplet practice, came from Messiaen's Messe de la Pentecôte (see Example 3), to which Stockhausen would surely have been introduced during his classes with the composer in Paris in 1952.Footnote 31

Example 2 Stockhausen, Klavierstück I, bb. 1–29. © Copyright 1954 by Universal Edition London (Ltd), London.

Example 3 Messiaen, Messe de la Pentecôte, Entrée, bb. 24–30. © 1951 by Alphonse Leduc Editions Musicales. Used by permission of Hal Leonard Europe Limited.

Regardless of their true origins, the most challenging rhythms of Klavierstück I represent a significant increase in complexity to those of Messiaen's piece, with no established practice for their realization at the time of writing. This is corroborated by the increasingly worried tone of Marcelle Mercenier's correspondence with the composer, prior to the premiere of Klavierstücke I–V at the 1954 Darmstadt Courses.Footnote 32 Following the initial publication of Klavierstücke I–IV by Universal Edition in 1954, Stockhausen provided an addendum advising that the more complicated rhythmic proportions be performed using tempo substitutions.Footnote 33 This is the first documentation of a technique that would subsequently be advocated as a means of approaching tuplet rhythms in later complex music,Footnote 34 suggesting a direct practical connection between Stockhausen's early work and the practice of New Complexity, overlooked by Duncan. In combination with other methods, including lowest common denominator proportioning,Footnote 35 and the production of bespoke counting tapes,Footnote 36 the nested tuplets of the opening bar are now eminently realizable, as the precision of a number of performances, to be discussed in due course, will testify.

Not all the rhythmic figurations in Klavierstück I are so straightforward, with challenges arising when complex rhythms are combined with disparate pitch distribution and non-idiomatic dynamic markings. The most extreme example of this occurs in bar 6 (see Example 2 for all references to bb. 1–29), where two sets of asymmetric nested values must be played within an over-arching 5:4 quaver proportioning, with pitches distributed in groups across the keyboard, and dynamics switching rapidly between ff and fff.Footnote 37 Matters are made significantly more complicated, and from the listener's perspective more interesting, by Stockhausen's direction to perform the piece ‘as fast as possible’ according to the speed of execution of the smallest note values, which occur in the second nested group of this bar. As my analysis will show, the way that performers approach this bar and what they choose to prioritize in its interpretation has remained relatively consistent since the first performances, with implications for the aesthetics of each performance as a whole.

These instances of ‘irrational’ notation constitute one extreme of a rhythmic continuum in Klavierstück I, which extends down to simple binary relationships, and ultimately the inaction denoted by various rest durations. This non-dialectical continuum (non-dialectical in that no one element emerges as more important than any other) is an essential feature of the statistical form of serial music. According to Grant, ‘the criteria of statistical form are not heard in terms of individual formants but as complexes. This depends on the rate at which events occur: slower structures will increase the ability to hear the individual elements, so that pointillist structures can be described as a special case of statistical form’, concluding that ‘it is the possibility of a field between these extremes which appealed to Stockhausen’.Footnote 38 What matters for the listener, and indeed the performer, is the serially determined equilibrium of rhythmic complexity, ranging from that which might theoretically be performed with the type of literalism ascribed by Mathew and Duncan, to that which demands technical compromise and innovation, ensuring unforeseeable results. The difference in later complex music is the overriding presence and drastic expansion of this latter category.

In line with its serial premises, the level of variegation in dynamic markings in Klavierstück I does not change when material becomes more rhythmically complex and less idiomatic. Therefore, the possibility of literally realizing dynamic contrasts is also contingent on the complexity of the material, and the performer's choice of tempo. Hence the stark opening juxtapositions and subtle p–mf voicing of the A–B♭ dyad in bar 1 are technically achievable at a range of tempi, whereas the non-idiomatic juxtapositions of bar 6 remain impossible for the performer and imperceptible for the listener at any significant speed.Footnote 39 As I will highlight, a wide range of dynamic interpretation has been recorded within idiomatic contexts, with some performers flattening or attenuating contrasts – thereby exhibiting the type of objective colour palette that Mathew describes – while others have played them up.

While the non-idiomatic dynamic configurations of bar 6 and elsewhere remain within the realm of technical possibility, Stockhausen's stratification of dynamic markings in certain chords is more fundamentally problematic. Ian Pace has cited non-idiomatic voicing, particularly that which avoids uncritical projection of the upper part, as a key feature of modernist performance practice, with direct reference to Stockhausen's early Klavierstücke.Footnote 40 Countering Ronald Stevenson's assertion that dynamically stratified chords in these pieces are ‘simply unplayable’, Pace suggests that they can be discerned in recordings by Aloys Kontarsky, Tudor, Herbert Henck, Bernhard Wambach, and Ellen Corver.Footnote 41 However, close listening to the stratified chords in bars 11 and 54 in these recordings disproves this. Indeed, Corver herself has addressed the impossibility of realizing the bar 11 chord – made more challenging by its high register – in her thesis on the performance practice of Stockhausen's piano music.Footnote 42 Some creative solutions to this problem have emerged, which I will address in due course. However, in literal terms, the notation, which suggests thinking in terms of layers of electronic sound, does not afford a direct translation, at best pointing towards the possibility of creative voicing elsewhere.Footnote 43

One of the most significant pianistic developments to emerge from serial and American experimental music in the 1950s was the expanded use of the pedals. In serial music, these innovations came in two principal forms. First, the colouristic use of half and other variable sustaining pedal markings, often appearing in combination with novel modes of attack, first pioneered by Tudor in his work with John Cage and other members of the New York School, and adopted by Stockhausen in Klavierstücke V–XI.Footnote 44 Second, and less widely recognized because of its subtlety, is the virtuoso use of the sostenuto pedal, which became needed to precisely manage the stratified textures of early serial music.

Sustaining pedal markings are minimal in Klavierstück I, with directions in bars 1, 46 and 47 designed to affect the accumulation and simultaneous release of disparate tones, in bars 42 and 61 to affect a more resonant climax, and in bars 24–7 and bars 48–50 to affect an impressionistic wash, contrasting with the implicitly dry articulation of surrounding material (see Example 4 for all references to bb. 39–50). This latter colouristic use of the pedal evokes the timbre of early electronic music recordings,Footnote 45 while anticipating the more sophisticated and diverse use of sustaining pedal in the later piano pieces. Particularly when combined with subito dynamic juxtapositions (see, e.g., the transitions from bb. 23–24 and 47–48), it is equally suggestive of Stockhausen's background as an improviser of special effects.Footnote 46

Example 4 Stockhausen, Klavierstück I, bb. 39–50. © Copyright 1954 by Universal Edition London (Ltd), London.

Elsewhere, use of the sostenuto pedal is clearly implied, though never indicated. For example, it is needed to sustain the lower dyad of bar 5 through the virtuosic figurations of bar 6.Footnote 47 In other places, such as bar 20, where Stockhausen calls for the stratified release of a six-note chord within a 7:8 quaver–tuplet proportioning, implied use of sostenuto pedal is more complicated. Whether envisioned by Stockhausen or not, one ‘solution’ here involves catching the low grace-note dyad in the sostenuto pedal, then quickly playing the upper pair of dyads, before substituting fingers to retake the upper note of the lowest dyad. The low E♭ can then be released from the sostenuto pedal, with the remaining note-endings controlled manually.Footnote 48 The influence of such implied sostenuto pedal use in Klavierstück I, and in other serial music, can be felt in the sophisticated and explicit use of sostenuto pedal by composers such as Helmut Lachenmann and Rebecca Saunders, particularly as a means of sustaining silently depressed keys, a technique that would also become prevalent in the later Klavierstücke.Footnote 49 However, as Peter Hill has pointed out, the uncharacteristic cloudiness of Messiaen's own recording of Mode de valeurs suggests that sophisticated use of the middle pedal had not been considered for the earliest serial piano music, even by expert pianist-composers.Footnote 50 Indeed, neither this piece nor Boulez's Structures I contain any pedal markings. The performer is thus left to decide whether adjacent notes should be separated or connected, and how to manage and prioritize durational overlaps. This suggests an influential performer-driven development, made in response to music for which, as Grant observes, practice frequently lagged behind theory.Footnote 51

As with many aspects of the performance practice of serial music, the use of sostenuto pedal becomes a question of technical priority, with ramifications for textural clarity, as well as rhythmic execution, and even choice of tempo.Footnote 52 As Stockhausen's comments reveal, precision of duration was of paramount importance, and as the technical management of bar 20 shows, this was not always as simple as Mathew and Duncan would have us believe. The question of pedalling in relation to the connection or separation of tones, however, remains more subjective in its interpretation.

Klavierstück I features just two explicit articulation markings, namely slurs linking dyads in bars 3–4 and linking a four-note chord with a single high tone in bars 9 –10, in stark contrast to the ubiquitous, parametric variety of articulation markings in Mode de valeurs and Structures I, thereby sidestepping some of the contradictions of these works.Footnote 53 The performer is therefore left to decide in many instances whether to connect adjacent tones, using either a manual legato – often calling for finger substitution or the rearrangement of hands – or the sustaining pedal, or whether to embrace the separation of disjunct intervals, thereby fostering a drier, pointillistic texture. The visual aspect of these decisions in live performance is also important. For example, Gregor Prozesky, in his video recording, the only such version currently available on YouTube, clearly lifts his hands away from the keyboard between the opening tones, thereby invoking a pointillist aesthetic, despite the audible, notated connection of these tones with the sustaining pedal.Footnote 54 Other pianists, including myself, prefer to connect these, and as many other adjacent tones as possible, manually, to create a more linear and lyrical sense of line, further conveyed in live performance through physical engagement with the keyboard. The visual impact of this physicality is of course lost in audio recordings; however, an awareness of the embodied gestures involved in all the interpretive actions discussed previously remains vital for appreciation of this music – an idea to which I return at the end of the article.

Orientation and methods of analysis

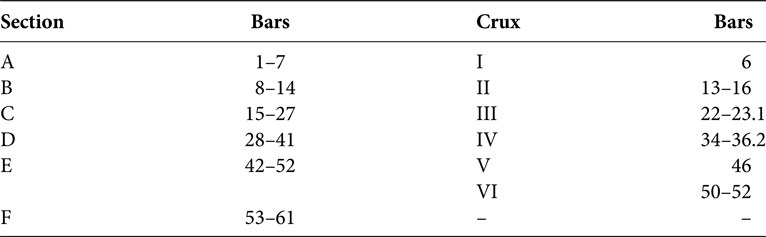

Bar 6 represents what I will term the ‘Crux’ of Klavierstück I and should theoretically determine each performer's ‘as fast as possible’ tempo, depending on which aspects of the notation they choose to prioritize.Footnote 55 There are five more similarly dense and technically challenging passages, constituting further localized Cruxes. These six Cruxes are fairly evenly distributed between the six Sections of approximately twenty-one crotchets that appear in Stockhausen's original sketches, labelled A–F.Footnote 56 As Table 2 illustrates, each Section contains one Crux, except for Section E which contains two, and Section F which contains none.

Table 2 Distribution of Sections and Cruxes

In light of my analysis of the affordances of the score, and the equilibrium of technical difficulty which stands in direct relation to the serial organization of material, these passages become important foci for serial listening. First, with respect to their extreme physicality, whereby the irrational, embodied physicality of the performer stands in maximum contrast to the analogous, yet fixed sonic complexes of contemporaneous electronic music. Second, in their contrast with moments of maximum repose and simplicity within the piece itself, that is, as collective extremes of the interrelated, rhythmic, dynamic, and registral continua that underscore the composition. Whether a performer maintains tempo through these passages, speeds up, or, as is frequently the case, slows down, and of course how passages of lesser complexity are treated, will also have a significant effect on the maintenance or distortion of rhythmic and textural equilibrium, and thus the quality of the serial aesthetic. For this reason, while bearing in mind the traditional formal significance of rests and long tones, my analysis is primarily oriented around these six Sections and their constituent Cruxes.

The performance analysis itself is broadly traditional, using the program Sonic Visualiser to collect timing data in support of what Cook has called ‘close and distant listening’.Footnote 57 Simply put, close listening involves detailed analysis of recordings, with empirical data and analytical software used to augment the analyst's aural capabilitiesFootnote 58 and to convey their findings to the reader. Distant listening involves the analysis of trends, typically involving tempo, in large bodies of recordings.Footnote 59 The dangers of both approaches, including the potential for data to override and even replace the listening experience, persist in the study of contemporary repertoire. The lack of ready access to recordings that remain under copyright, or are expensive or difficult to procure, also poses a significant problem, perhaps explaining why relatively little attention has been directed towards new music in this field.Footnote 60 It is of course recommended that the reader listen to and engage with as many of the recordings under discussion as possible, with timings given where appropriate. However, I do recognize that while Tudor, Pi-Hsien Chen, and Sabine Liebner's recordings are currently available on streaming services, and others may be found online, not all will be readily accessible. This is where data collected in aid of distant listening can become important in and of itself, as representative not of individual approaches but of trends and patterns in performance, which may contribute to wider understanding of the performance practice of serial music as a cultural phenomenon.

It is also important to acknowledge that in approaching the contentious field of serial music, the empirical performance analyst stands open to the same criticisms of artistic rationalization levelled at the serialists themselves. Stockhausen's observation that there are ‘essential musical phenomena that are not susceptible to measurement’ remains pertinent, and it is not my aim to prove or disprove ‘facts’ of performance. Rather, use of data, in combination with qualitative judgements, and informed by my own extensive experience of performing the piece, is designed to guide the listener towards the complex tension that exists between the notation and the sounding outcome in performance.

Finally, some notes on my technical approach. In Table 2 and throughout my analysis, individual attacks, containing single or multiple tones, are referenced in terms of their position within each bar; for example, attack 1.8 for the G–F♯ dyad in bar 1. Inter-onset timings were extracted using Sonic Visualiser. In light of their temporal ambiguity, grace-notes, appearing individually or in pairs in bars 7, 19, 20, 34, 42, and 54 were not accounted for, resulting in an inevitable, if slight distortion of timing data. Misalignments and omissions were necessarily factored into calculations. Since they are not consistently audible, the release of notes/onset of rests was disregarded. Consequently, average tempo was determined from the first attack value of sections beginning with rests and average tempo for preceding sections was determined up until the final attack value. Average tempi for Cruxes I and IV were determined up until the final attack of each bar, thereby avoiding the metric ambiguity of subsequent grace-notes. ‘Global tempo’ refers to the average tempo of the performance as a whole.

Performance analysis

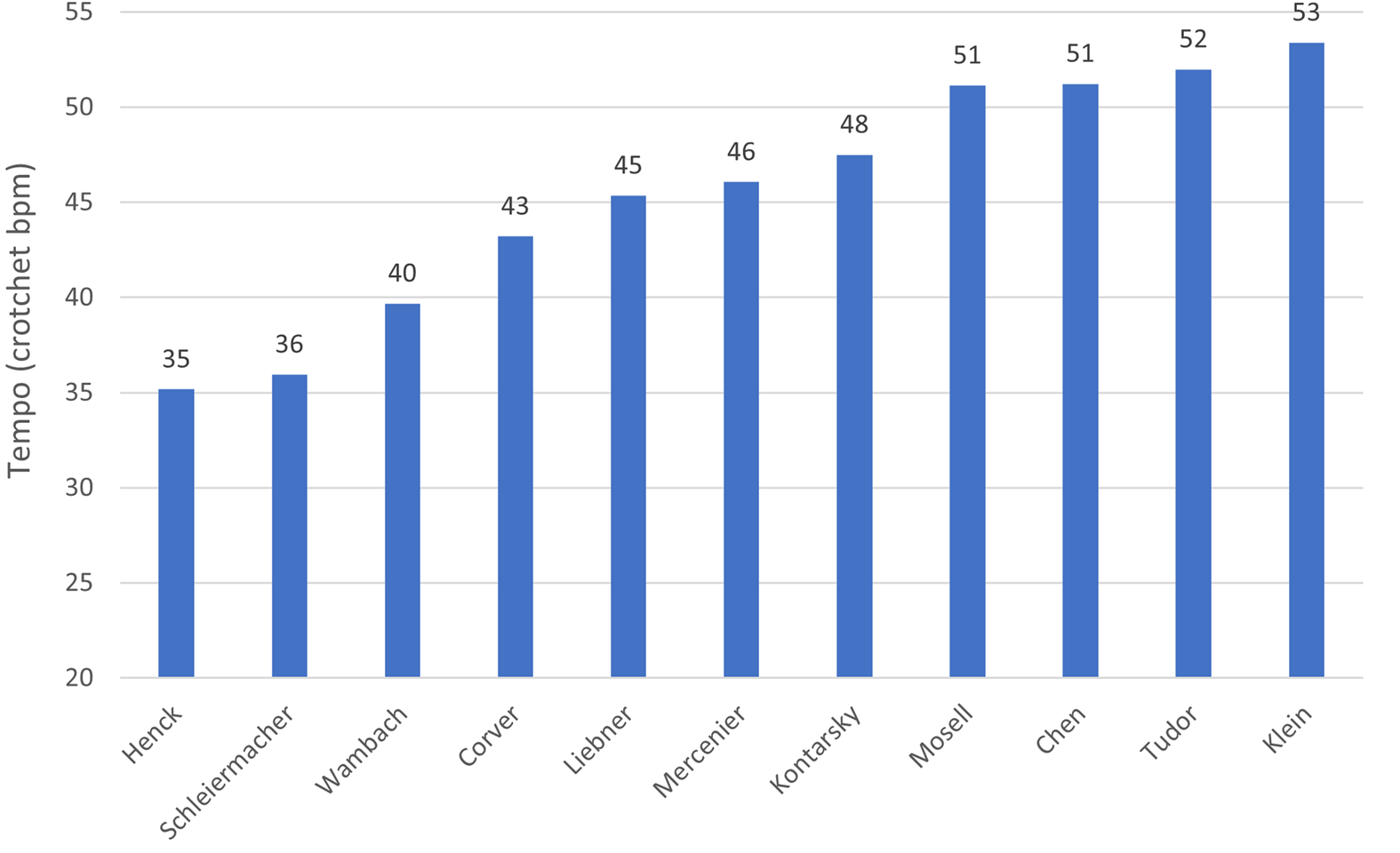

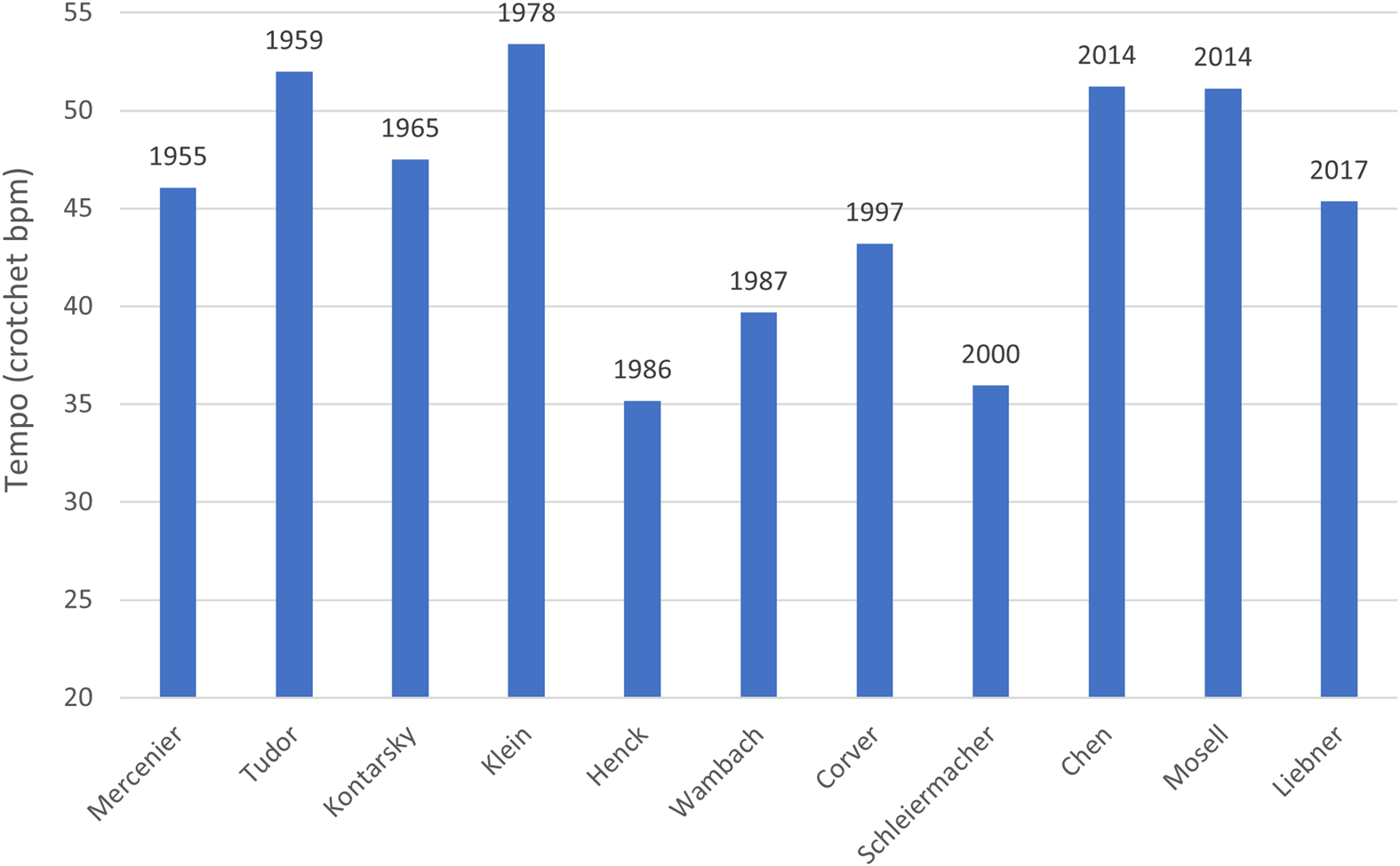

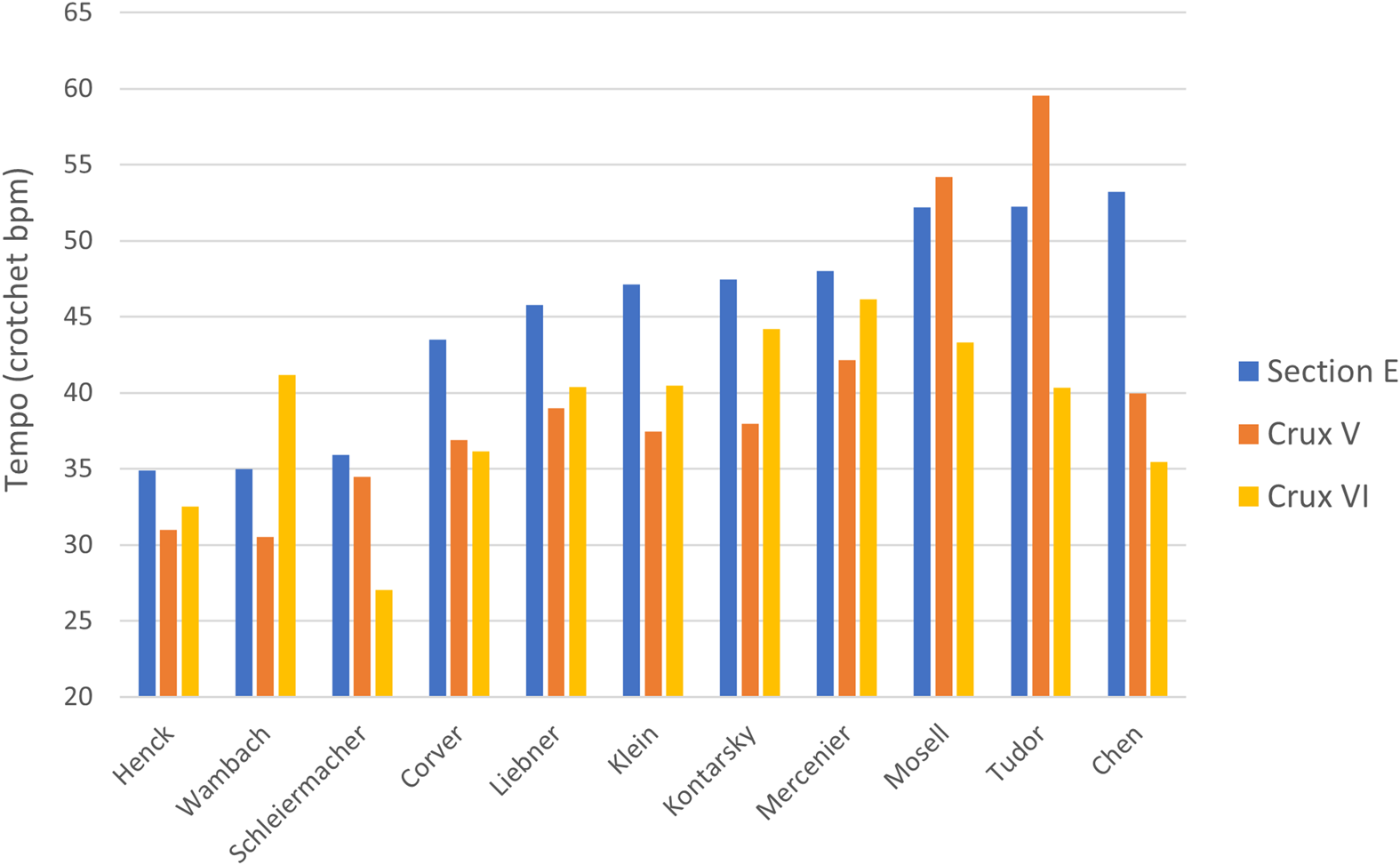

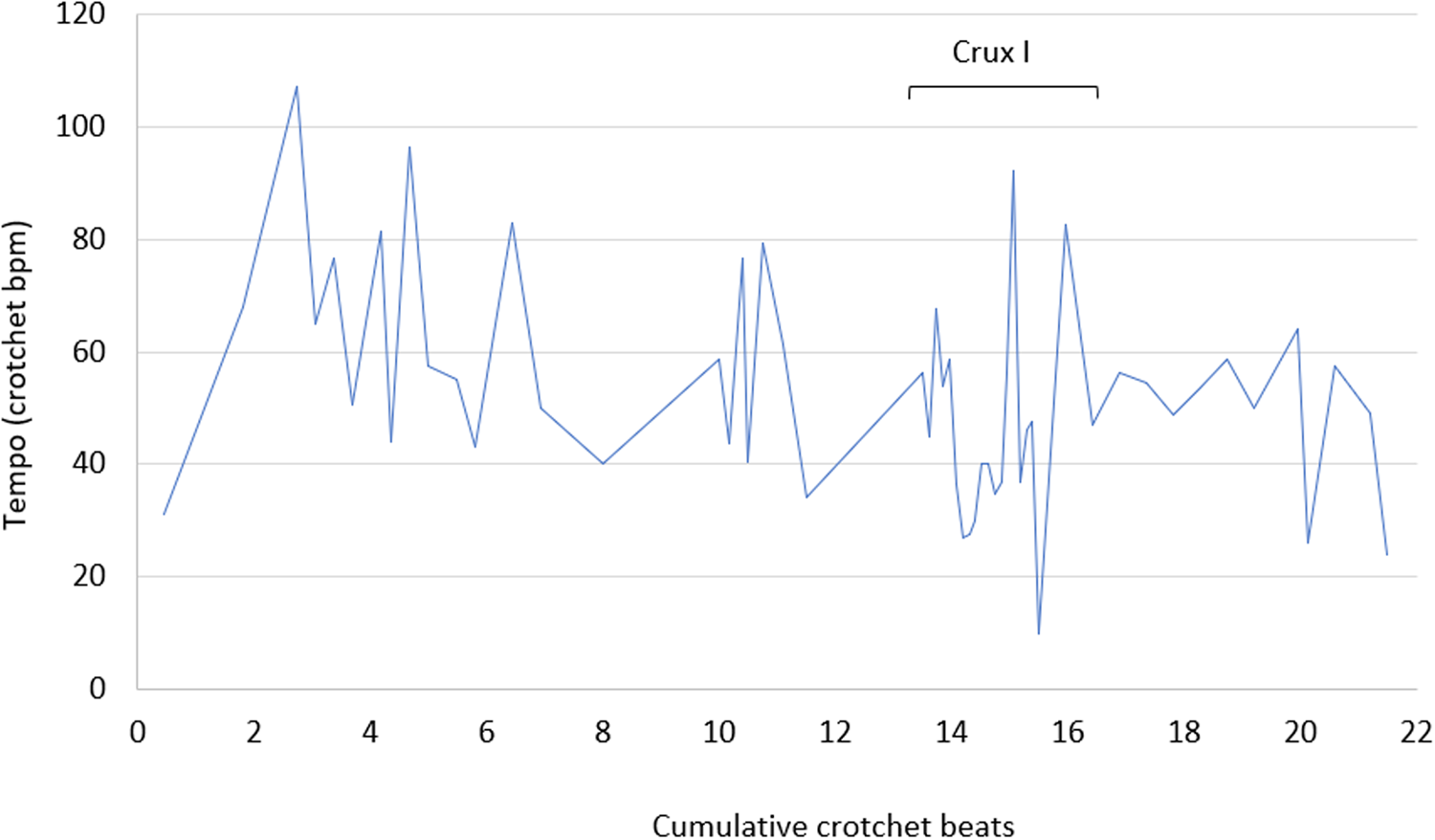

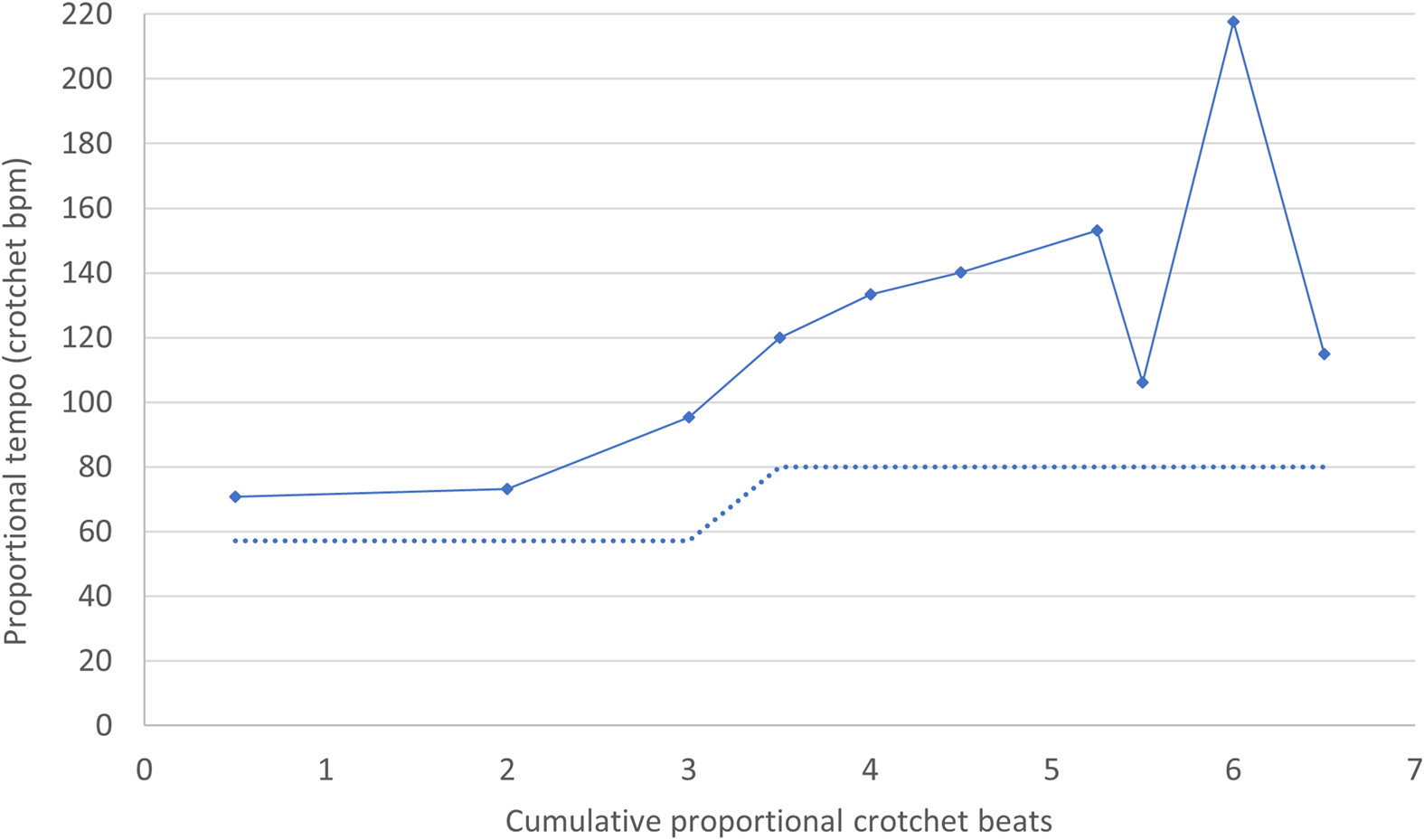

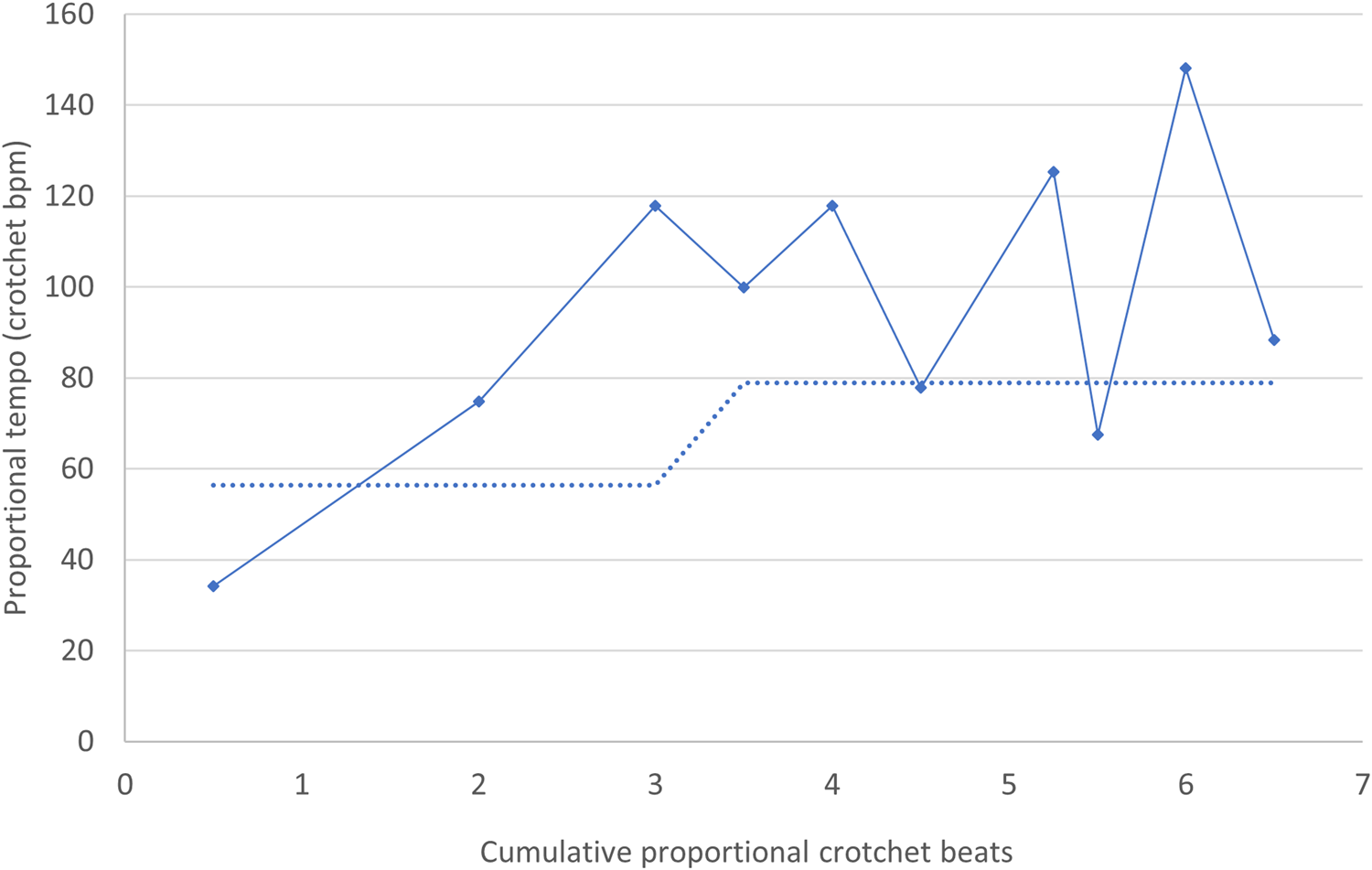

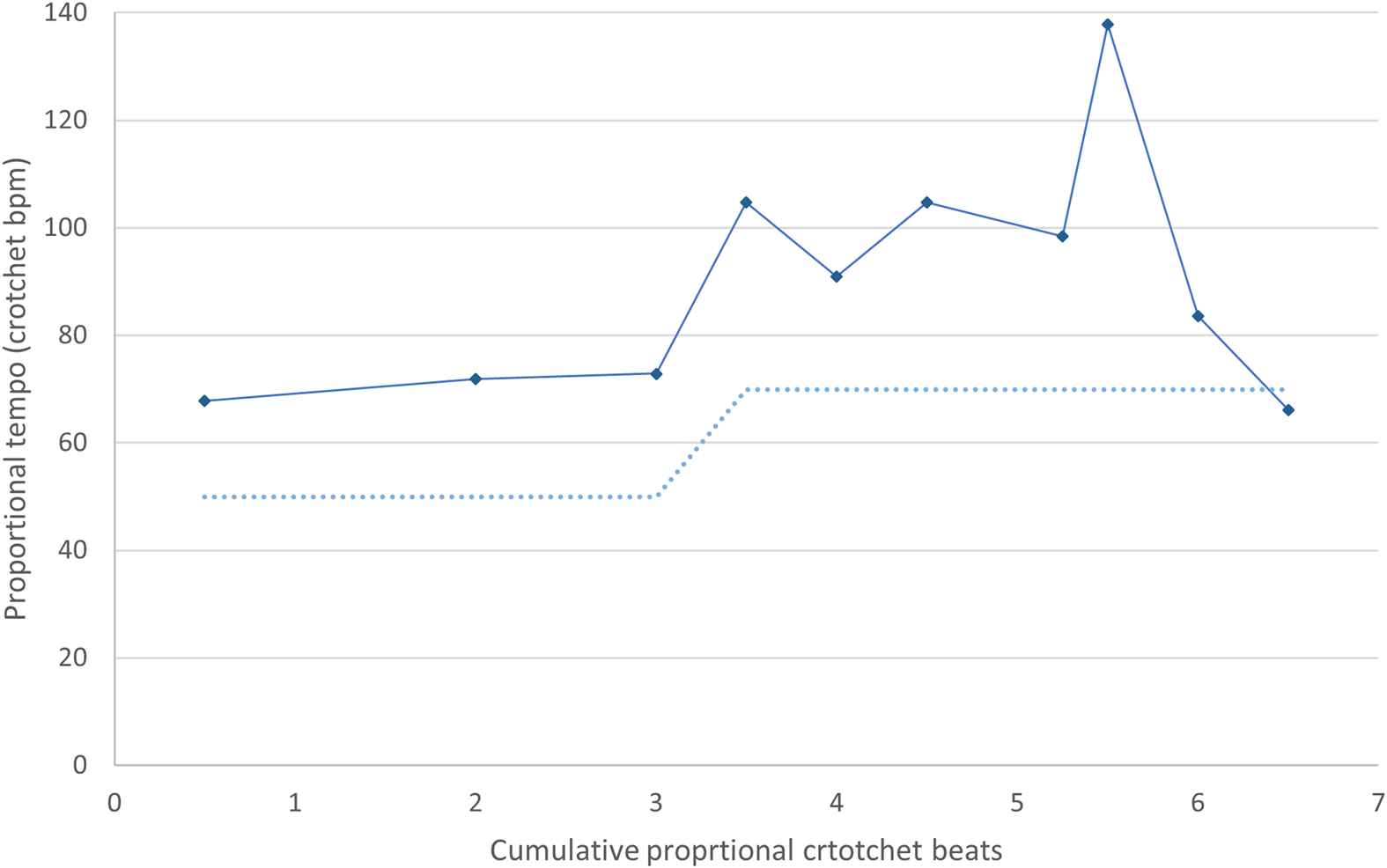

Individual responses to Stockhausen's ‘as fast as possible’ direction have resulted in a wide range of global tempi in the selected corpus of recordings, presented in ascending order in Figure 1. While limited, these data suggest the presence of relatively slow (Henck, Schleiermacher, and Wambach), moderate (Corver, Liebner, Mercenier, and Kontarsky) and fast (Mosell, Chen, Tudor, and Klein) performance types. As the chronological ordering of Figure 2 illustrates, Henck's recording is significantly slower than those of his predecessors, ushering in a series of slower performances before a return to faster tempi in the 2010s. Together the data suggest personalized responses to the ambiguous affordances of the score.

Figure 1 (Colour online) Average global tempi of recorded pianists in ascending order.

Figure 2 (Colour online) Average global tempi of recorded pianists in chronological order.

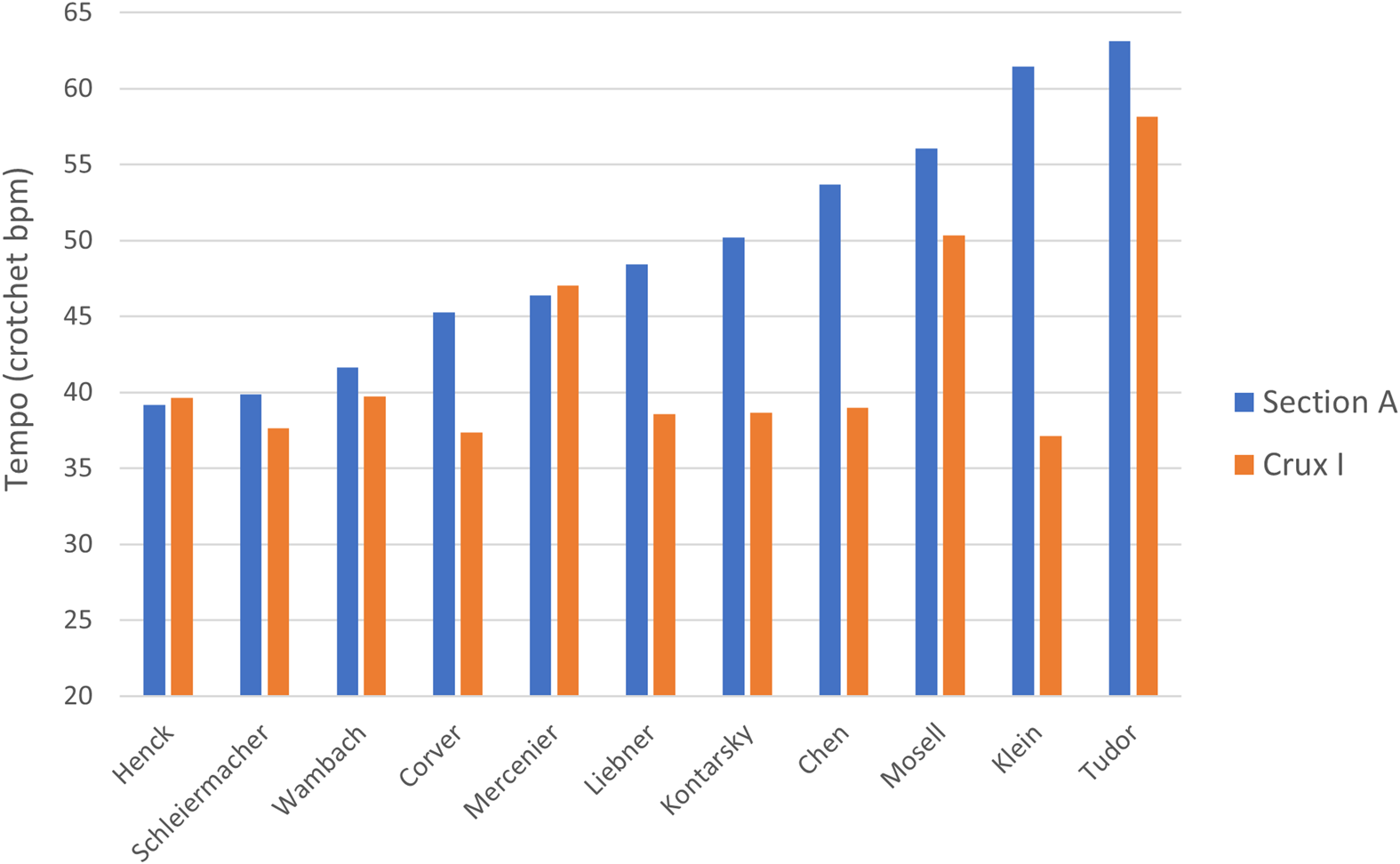

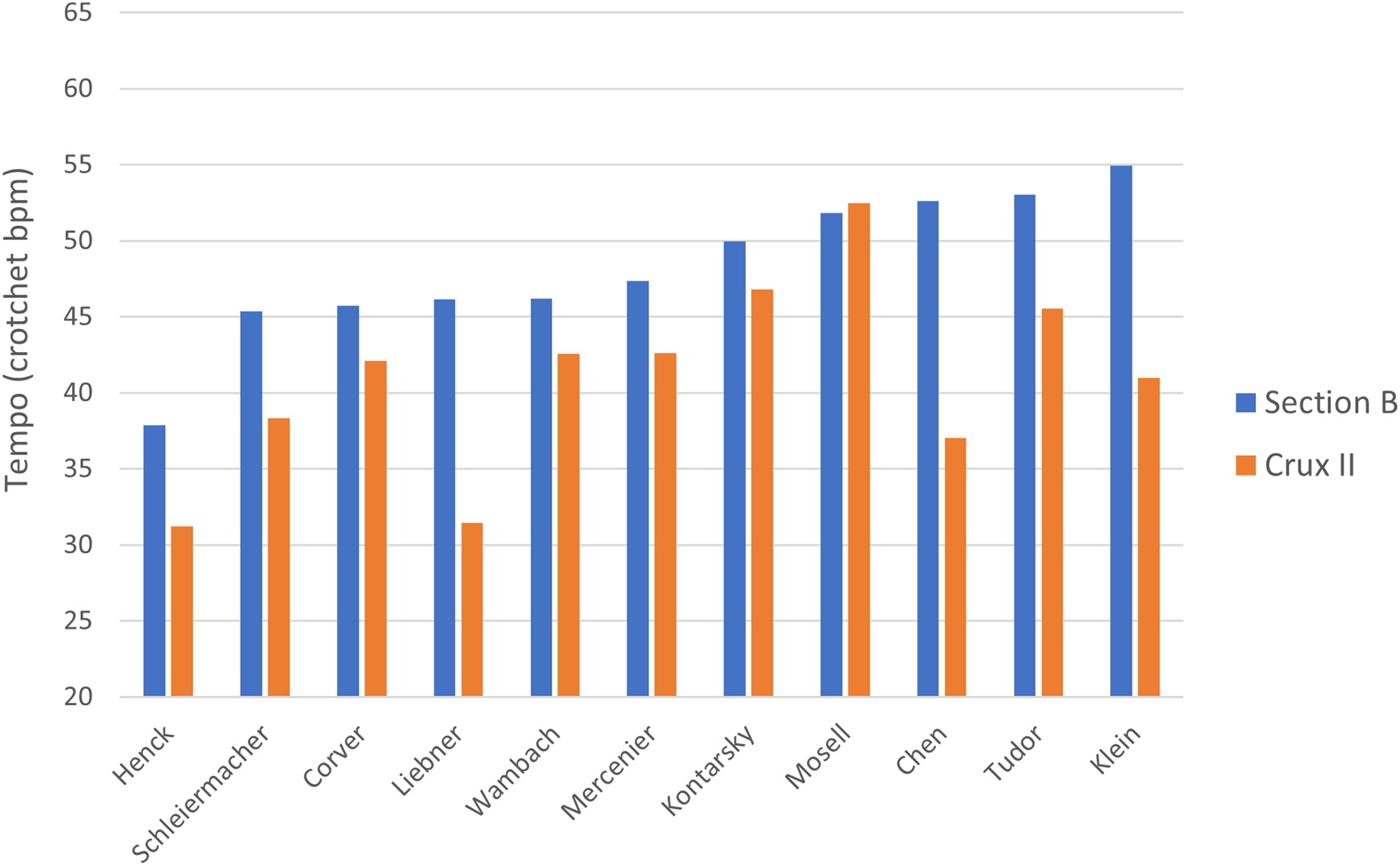

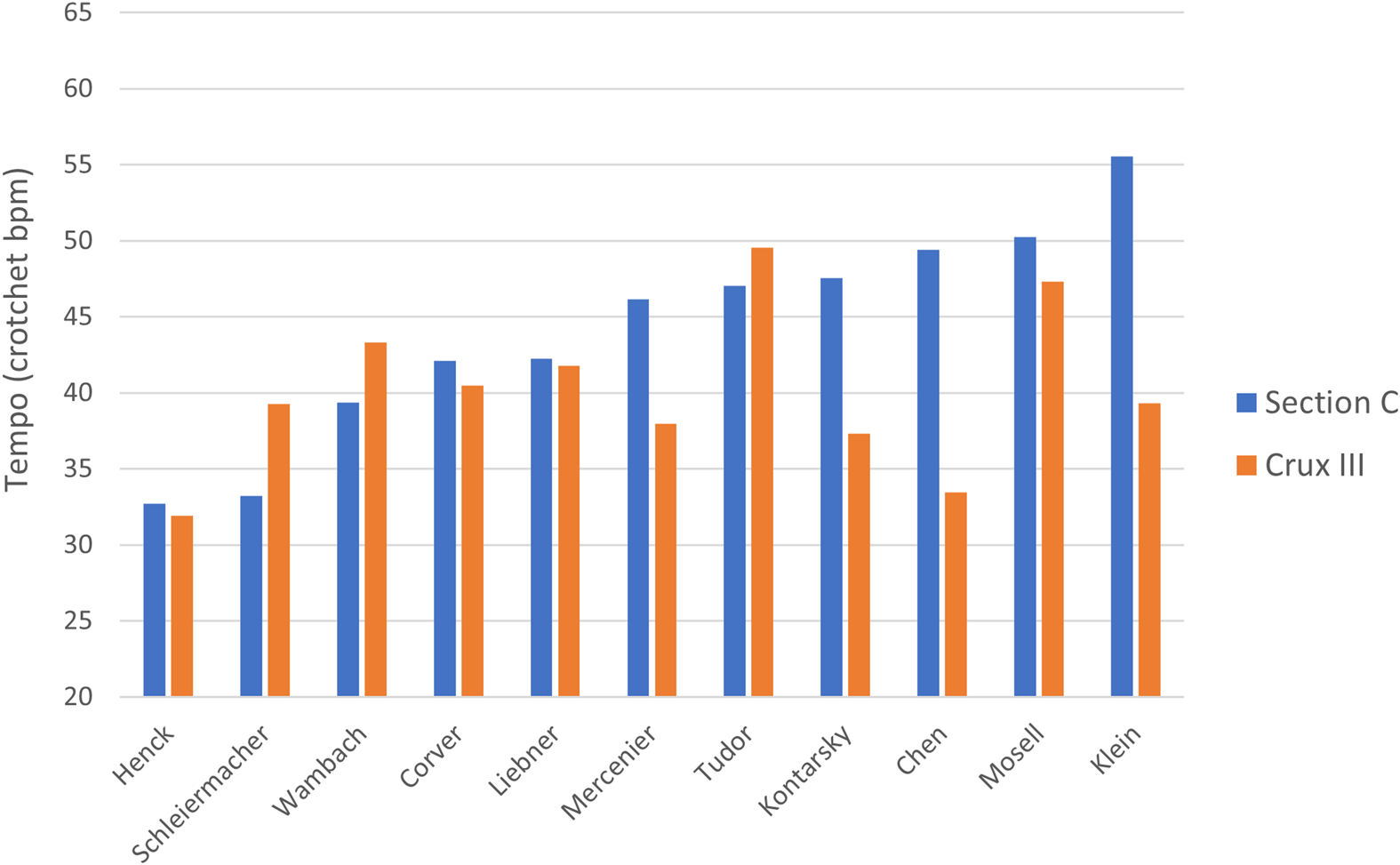

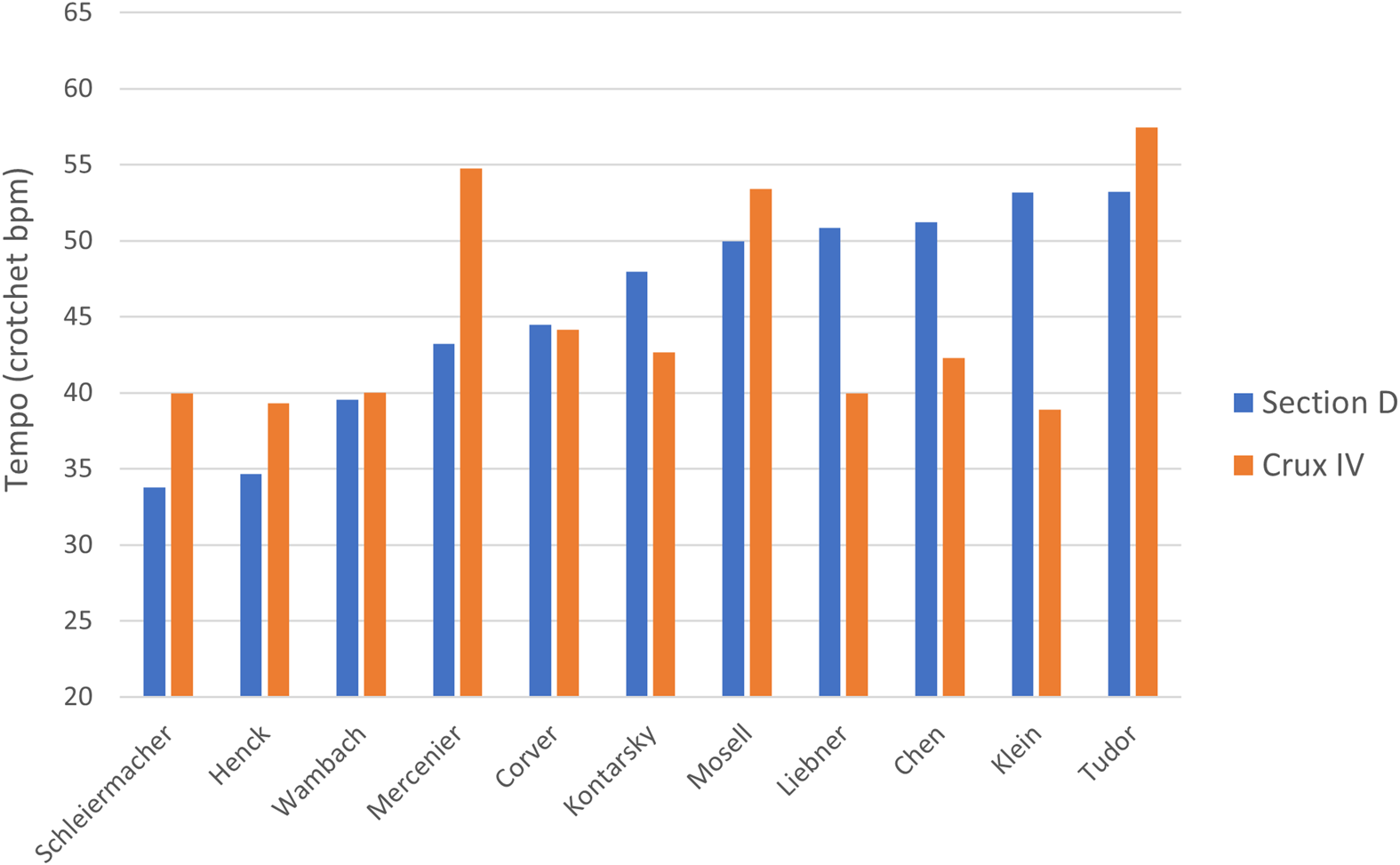

While certain stylistic correspondences can be heard between performances at similar tempi, there are also notable differences, particularly affected by tempo consistency and the proportional performance of Cruxes. As Figures 3–7 illustrate, with performers in ascending order of sectional tempi, these passages are almost always performed more slowly than their respective Sections. Isolated exceptions to this rule include Henck and Mercenier for Crux I, Mosell for Crux II, Schleiermacher, Wambach and Tudor for Crux III, Mosell and Tudor for Crux V and Wambach for Crux VI. In contrast, six of the eleven pianists play the demisemiquaver-quintuplets of Crux IV faster than their average tempo for Section D, highlighting a tendency for pianists to perform this Crux with greater virtuosity, perhaps in response to the more idiomatic grouping of pitches.

Figure 3 (Colour online) Section A and Crux I tempo comparison.

Figure 4 (Colour online) Section B and Crux II tempo comparison.

Figure 5 (Colour online) Section C and Crux III tempo comparison.

Figure 6 (Colour online) Section D and Crux IV tempo comparison.

Figure 7 (Colour online) Section E and Cruxes V and VI tempo comparison.

In terms of individual performances, Mosell is the most consistent, often playing slightly faster during Cruxes, despite her fast global tempo (♩ = 51), thereby foregrounding the inherent virtuosity of the piece. Elsewhere, Henck and Schleiermacher's proportional interpretation of Cruxes is the most varied, which, in combination with their slower global tempi and creative approach to expressive detail (to be discussed in due course), accentuates the heterogeneity of group material. Finally, Klein, Liebner, and Chen show the greatest tendency to slow down during Cruxes. This is particularly noticeable in Klein's recording, where slow Cruxes are thrown into greater relief by her otherwise propulsive global tempo (♩ = 53). As a result, the melodic content of each Crux becomes easier to discern, having the opposite effect to the irruptive performance of Cruxes in similarly fast recordings by Mosell and Tudor, which take on the quality of statistical Gestalten, contrasting in turn with the melodic quality of surrounding material.

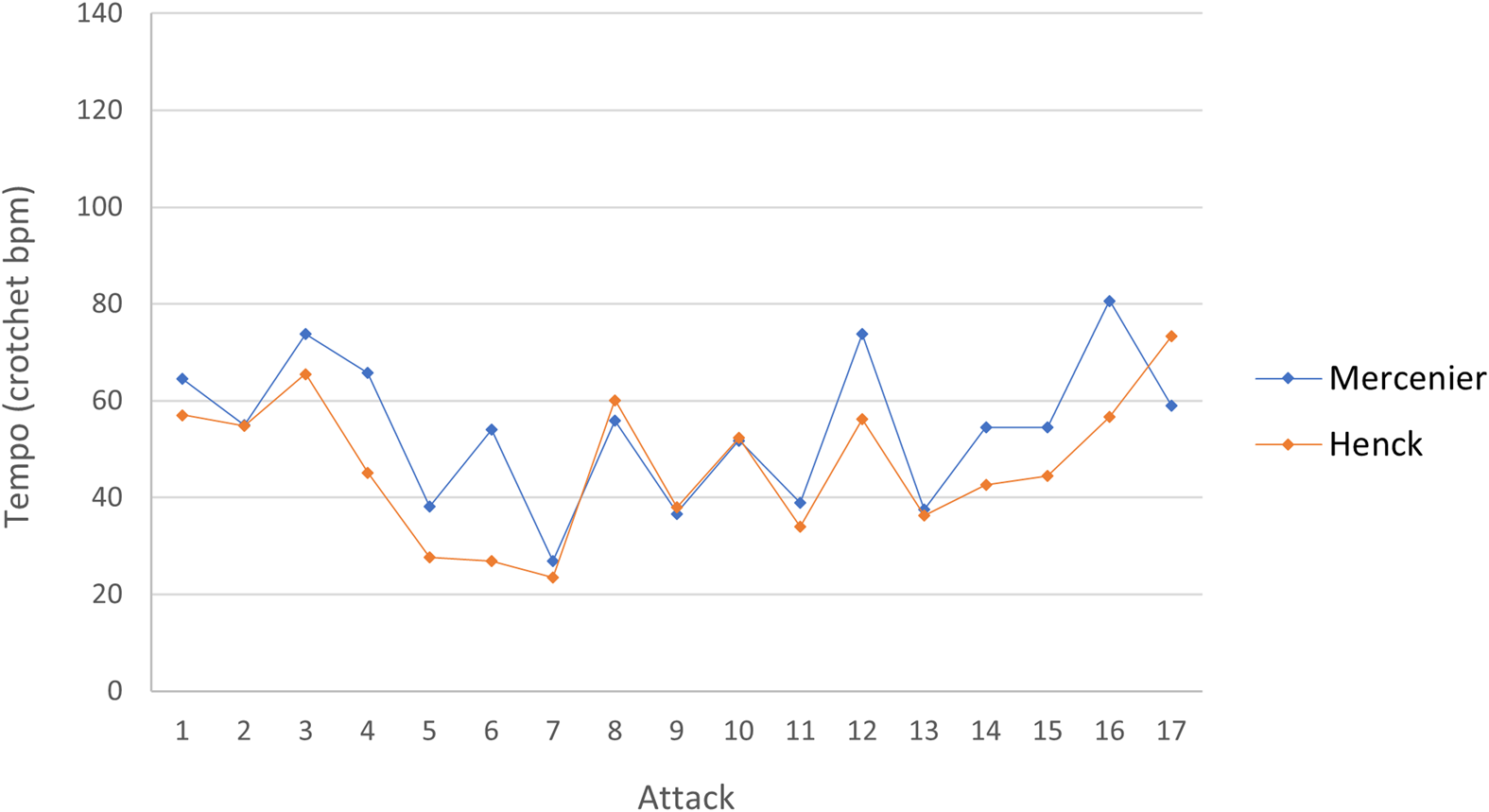

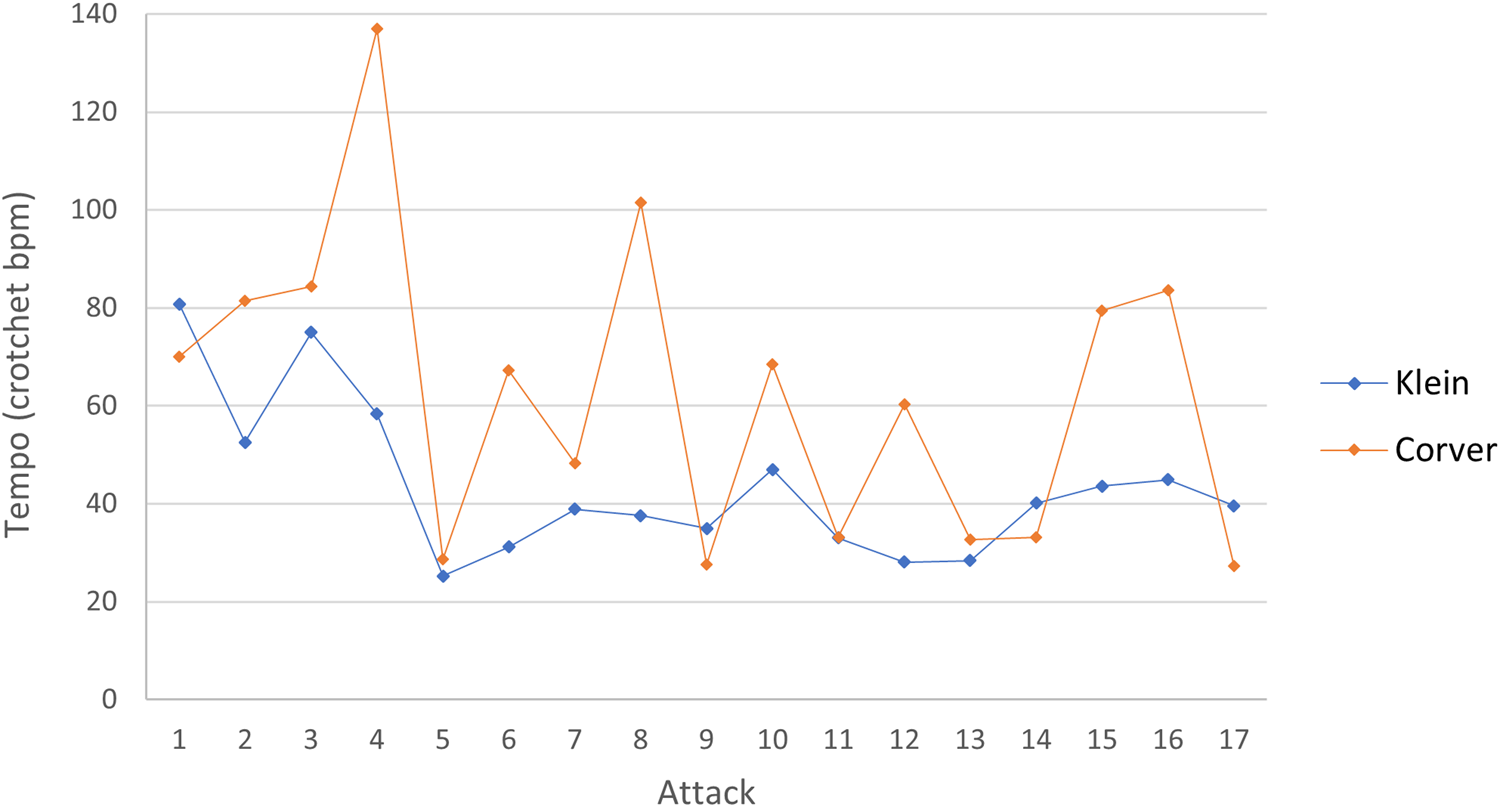

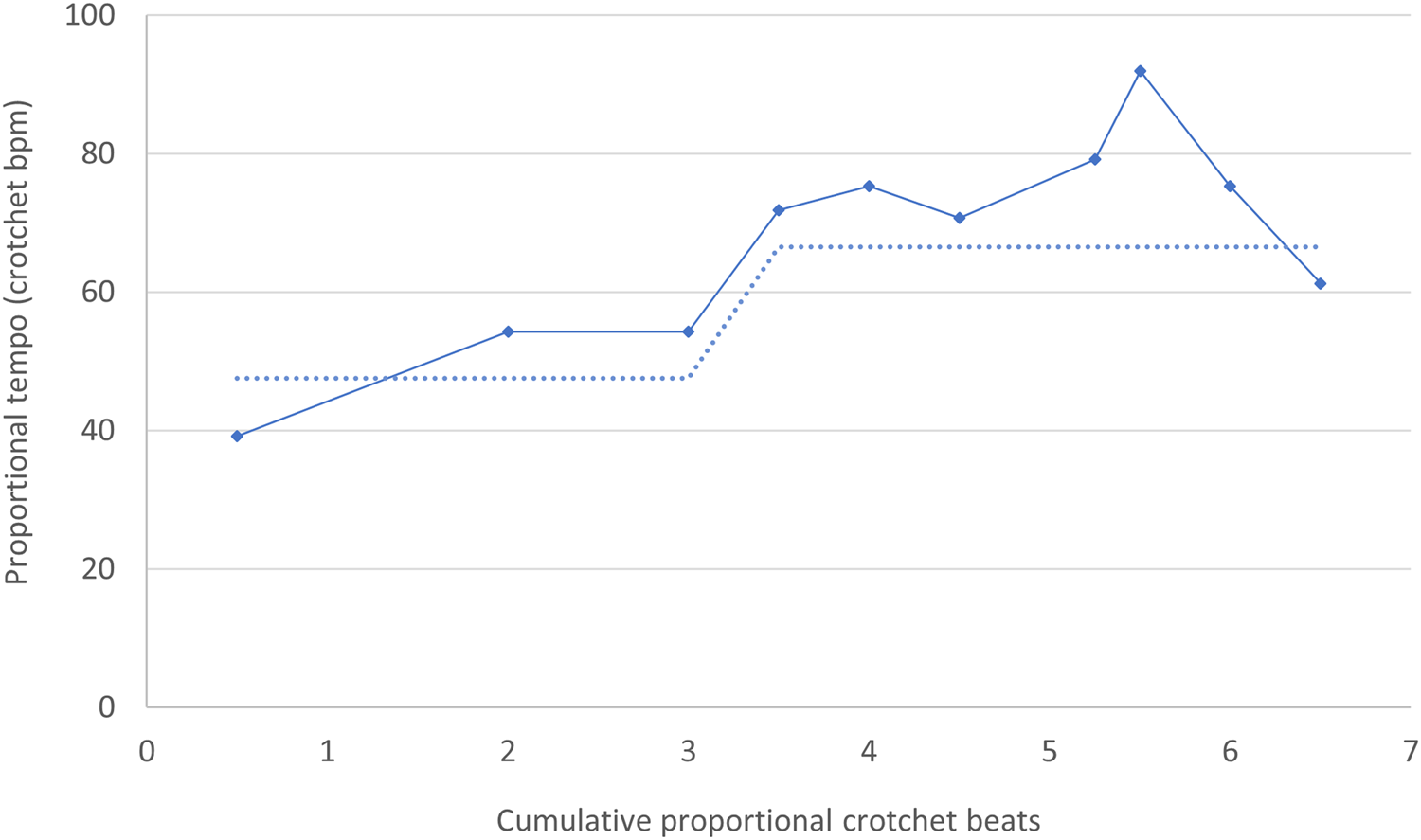

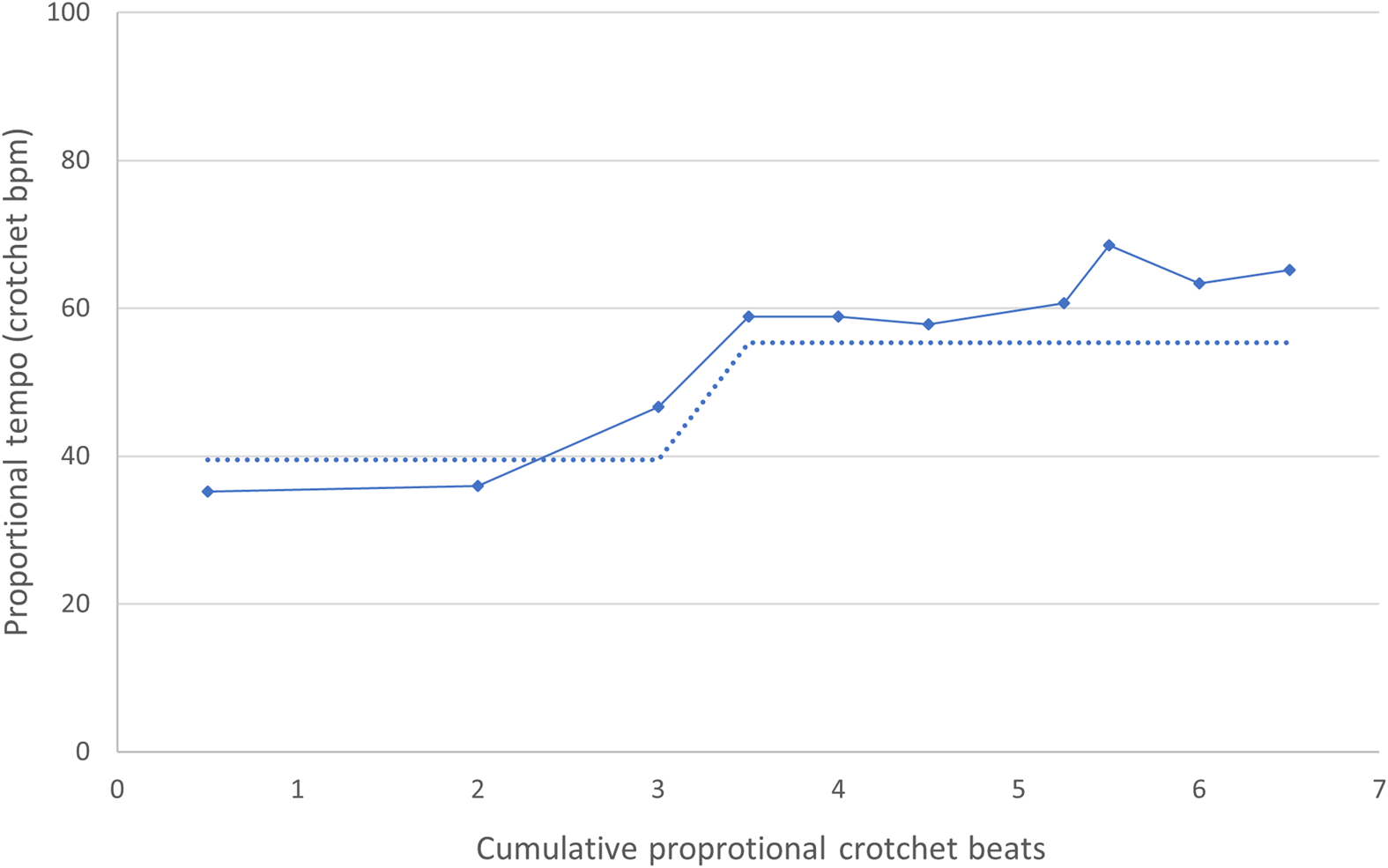

As noted, Mercenier and Henck are the only pianists to perform Crux I at a higher average tempo than Section A. Their tempo fluctuation during this Crux is also similar, excepting Mercenier's anticipation of attack 6.7 and Henck's acceleration towards the final dyad (Mercenier, 1′16″–1′20″; Henck, 0′19″–0′26″).Footnote 61 As Figure 8 shows, both pianists exhibit considerable tempo irregularity, performing the theoretically periodic groupings in short gestural bursts,Footnote 62 though Henck's studio recording is tidier than Mercenier's frantic live performance, the broader implications of which will be discussed in my final conclusions. These bursts, choreographed by the disjunct leaps and suggestive beaming of the groups, feature to a greater or lesser degree in every recording of Cruxes featuring periodic note values (i.e., I, III, IV, and the 7:6 tuplet of Crux VI). Corver's rapid gestures (0′28″–0′33″) and Klein's relatively even, restrained execution, particularly of the 11:12 nested tuplet (0′15″–0′21″), represent opposing extremes of this phenomenon in Crux I (see Figure 9).

Figure 8 (Colour online) Mercenier and Henck Crux I tempo comparison.

Figure 9 (Colour online) Klein and Corver Crux I tempo comparison.

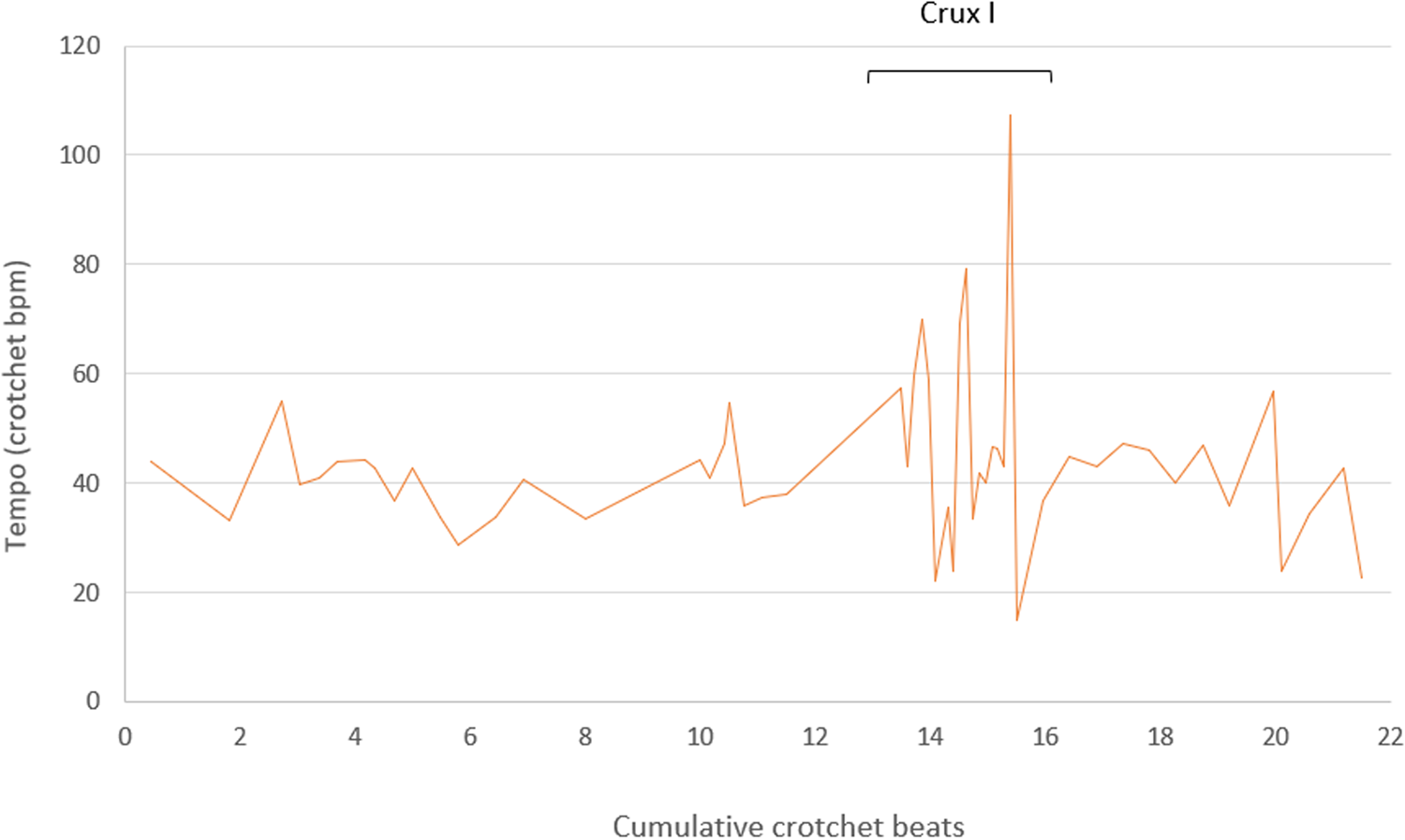

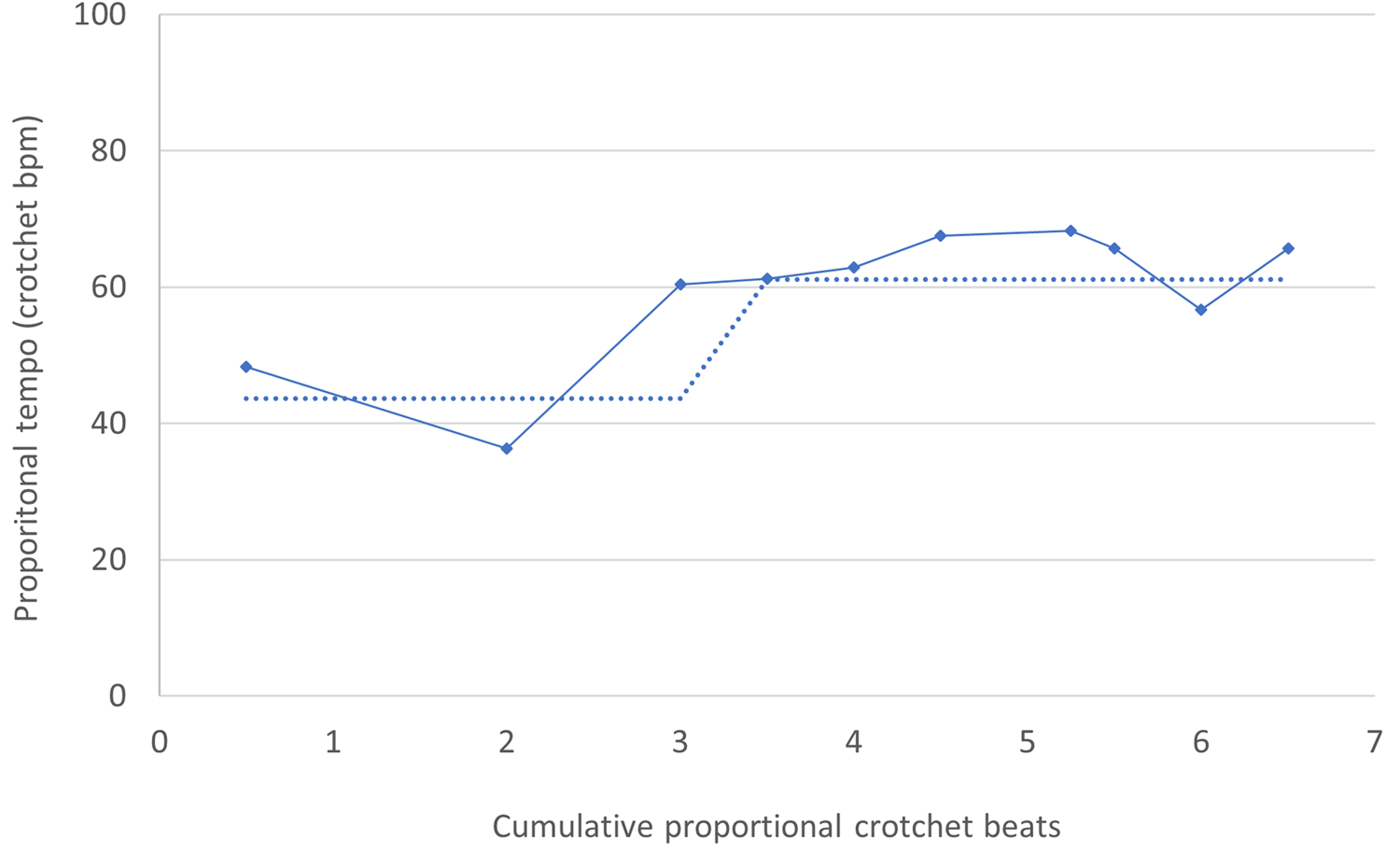

Outside of periodic Crux contexts, rhythms are generally executed more precisely. This is particularly striking in Wambach's performance, where the unpredictable dynamism of each Crux is enhanced by contrast with the measured poise of surrounding material, as illustrated in Figure 10 for Section A and Crux I (0′00″–0′31″). In contrast, Chen exhibits less distinction between rhythmic execution in Crux and non-crux contexts, as illustrated in Figure 11 (0′00″–0′28″). Together with her proportional slowing of every Crux (see Figures 3–7), this contributes to the homogeneity and impulsive character of her performance, contrasting with the greater sense of aesthetic variety in Wambach's stricter interpretation.

Figure 10 (Colour online) Wambach Section A tempo graph.

Figure 11 (Colour online) Chen Section A tempo graph.

In summary, nothing approaching the proportions of the nested-tuplet notation in bar 6 has been reproduced in any of the recordings. Instead, rapid, gestural performance of this and other Cruxes, evident from at least the time of Mercenier's 1955 live performance, has become part of the performance tradition, affecting differing degrees of fast, though not precisely calibrated, global tempi. While technically unspecified, evidence from Stockhausen's correspondence with Tudor indicates that he advocated this practice from the outset, writing that for groups of quick notes ‘even when [notes] are written with identic [sic] values … If you have a great interval, the duration of the first note will be a bit longer, than in the case of a small interval!! I really wrote in this manner.’Footnote 63 This directly anticipates his directions for the performance of grace-note groupings in Klavierstücke V–X, which specify that ‘the various intervallic leaps within groups of small notes [i.e., grace-notes] should result in a differentiation of the actual intervals of entry (do not make them equal)’,Footnote 64 suggesting a hitherto unexplored dialogical relationship between the performance practice and aesthetics of the two sets of pieces, with implications for the development of his temporal theory.

The emergence of this theory, allowing for degrees of inconsistency in performance within serially ordered ‘time fields’, is commonly attributed to Stockhausen's work on acoustics and information theory with Werner–Meyer Eppler in early 1954.Footnote 65 However, the composition and early performance practice of Klavierstück I might constitute an earlier precedent for this thinking. Given Stockhausen's abilities as a pianist and the idiomatic writing found elsewhere in the piece, he was surely aware of the contradictory demands of periodic values and the disparate distribution of pitches in Cruxes, in spite of the short time he took to compose the piece. These passages could thus be seen as early prototypes of Stockhausen's time fields, notated using grace-notes in Klavierstücke V–XI, and through the relation of tempo and breath in the wind quintet Zeitmaße (1956),Footnote 66 wherein irrational rhythmic effects are engendered by the physicality of the performers, as well as the acoustics of the space and the characteristics of the instruments. At the very least, these notational developments and the evidence of the earliest recordings, combined with insights from Stockhausen's correspondence, highlight the reciprocal influence of his observance and involvement in the early performance practice of Klavierstücke I–IV on the development of his temporal theory and his understanding of the unique characteristics of human performance. For the listener, Crux passages in Klavierstück I, lying at one extreme of the statistical spectrum, are the most unforeseeable in performance, varying subtly and sometimes dramatically, not just between performances by different pianists, but between live performances by the same pianist.

While less gestural and more consistently precise, performances of the idiomatic rhythmic figurations of Cruxes II and V still exhibit a significant degree of rhythmic variability, including the appearance of some noteworthy trends. For example, virtually all performers exhibit some form of rubato phrase-arching in the opening septuplet of Crux II (attacks 13.1–7).Footnote 67 Sharing a similar expressive flexibility, Klein (0′44″–0′46″), Henck (1′02″–1′04″), and Wambach (0′55″–0′57″) all accentuate the disjunct physicality of the initial hand movement by separating the second and third attacks, before subtly arching the remaining tones. In contrast, both Schleiermacher and Corver conceal the physicality of the leap, with Schleiermacher's measured reading (0′57″–0′59″) slowing subtly from the outset, while Corver's lyrical arching (1′04″–1′06″) matches the valleyed melodic counter of the grouping. Finally, the interpretations of the septuplet by Mercenier, Tudor, Kontarsky, and Mosell are more physically intense, with Mercenier (1′48″–1′50″) and Tudor (0′43″–0′45″) dramatically accelerating, while Kontarsky (0′48″–0′50″) and Mosell (0′50″–0′52″) are more chaotic.

Similar trends appear when complex tuplet configurations appear in non-Crux contexts such as bar 1. Thinking in terms of Stockhausen's recommended tempo substitutions, the opening 11:10 quaver tuplet of this bar corresponds to a subtle increase of base quaver speed (x 1.1), with the nested 7:5 tuplet affecting a further proportional, terraced increase (x 1.54). To make sense of the relationship of the performances and the score, I replaced the tuplet brackets with these proportional tempi to create a 6/8 + 7/8 bar (see Example 5).Footnote 68 I was then able to produce a hypothetical tempo line for each performer based on their average global tempo, to serve as a personalized benchmark for deviation. As Figures 12–14 show, Corver, Schleiermacher, and Wambach remain remarkably close to their hypothetical tempi, represented by dotted lines, with both Corver and Schleiermacher beginning slightly slower before gradually accelerating. Corver then peaks with an exaggerated hurrying of the semiquaver dyad, followed by a subtle allargando, affecting a greater sense of climactic arrival on the downbeat dyad of bar 2 (0′12″–0′19″). This subtle arching emphasizes the implicit tension and resolution of the notation, engendered by diminishing note values and the upwards trajectory of the grouping, further exemplifying Corver's lyrical approach to rhythmic expression. This profile is attenuated in the case of Schleiermacher, which, in combination with his slower global speed, lessens the rhetorical effect, allowing the listener more time to focus on the harmonic accumulation of tones (0′00″–0′09″). Elsewhere, Wambach's pronounced delay of the third attack is atypical, imbuing his opening gesture with a sense of coiled apprehension, which dissipates in his measured reading of the second subordinate group (0′00″–0′08″).Footnote 69

Figure 12 (Colour online) Corver b. 1 proportional versus hypothetical tempo.

Figure 13 (Colour online) Schleiermacher b. 1 proportional versus hypothetical tempo.

Figure 14 (Colour online) Wambach b. 1 proportional versus hypothetical tempo.

Example 5 Metric re-notation of Klavierstück I, b.1 using proportional tempi.

Contrasting approaches are taken by Tudor (0′00″–0′06″), Chen (0′00″–0′08″), and Liebner (0′00″–0′06″), all of whom deviate significantly from their hypothetical tempi, as illustrated in Figures 15–17. Tudor's exaggerated tempo and steady acceleration of attacks 1.3–7 is particularly striking, culminating in the dramatic gestural grouping of attacks 1.8–10, affecting a more intense expressive arching than that witnessed in Corver's recording (see Figure 12). Liebner and Chen, on the other hand, are both less predictable, deviating from the internal proportioning of the nested tuplets in a series of irregular gestures. Lack of strict rhythmic proportion is once again particularly pronounced in Chen's recording (see Figure 11), affecting a sense of unsteadiness, in maximum contrast with Schleiermacher's poised equilibrium and sense of unfolding melody. As the data show, Tudor, Liebner, and Chen, like Corver, all delay the downbeat dyad of bar 2. However, while Corver's and Tudor's interpretations emphasize the focal position of the chord, albeit with differing degrees of intensity, the sense of arrival is significantly weakened by Chen's and Liebner's prevailing inaccuracy in bar 1.

Figure 15 (Colour online) Tudor b. 1 proportional versus hypothetical tempo.

Figure 16 (Colour online) Chen b. 1 proportional versus hypothetical tempo.

Figure 17 (Colour online) Liebner b. 1 proportional versus hypothetical tempo.

As these case studies show, the complex rhythms and technical demands of Klavierstück I, combined with Stockhausen's ambiguous tempo direction, have given rise to a wide variety of realizations. Despite this variety, some key conclusions can be drawn. First, performances of the nested tuplets of bar 1 remain much closer to the notated proportions than those of bar 6. As might be expected, this suggests a more direct relationship between notation and performed result when technical difficulty is reduced, confirming the need for distinction between levels of complexity, and the limitations of the umbrella term ‘irrational notation’.Footnote 70 Second, my findings highlight the continuing presence of performance tropes associated with traditional repertoire, including rubato phrase-arching, acceleration through rising material, and the agogic delay of climactic chords. These tropes appear partly in response to the latent melodic character of much of the ostensibly progressive and intimidating rhythmic notation of Klavierstück I: a natural corollary of ‘group’ composition, but also indicative of Stockhausen's melodic thinking, and a key feature of Klavierstück I's move away from the instrumental pointillism of Mode de valeurs and Structures I. The impression of traditional phrasing is obscured, however, when, as in the case of Chen, certain rhythms are performed inaccurately, affecting a more consistently statistical aesthetic, in contrast to the interplay of the lyrical and the statistical that characterizes recordings such as Wambach's and Corver's, and relates directly to Grant's interpretation of Stockhausen's theory of statistical form.

The inaccuracy of many performers in simpler rhythmic configurations points to the more progressive quality of tuplet notation in less ostensibly challenging contexts. For example, the sequential 5:5, 4:5, and 5:4 metric proportioning of bars 24–9 appears to be responsible for significant distortion of the constituent semiquaver pulse and basic iambic rhythms in many of the recordings, including those that are otherwise very accurate (hear, for example, Corver 1′32″–1′40″). Elsewhere, the nested triplets of bar 44 are performed with a sense of syncopated swing by Klein (1′42″–1′47″), Schleiermacher (2′27″–2′34″), and most notably Kontarsky (1′53″–1′59″). This unexpected, and perhaps unintended, playfulness appears at odds with the austere rhythmic notation, more precisely reproduced by Henck (2′32″–2′40″) and Wambach (2′14″–2′25″), whose stricter interpretations affect subtle, terraced shifts of rhythmic density, bearing a closer relation to the non-expressive ‘rhythmic’ juxtapositions of electronic music. This shows that whether performers study and perform these passages with the assistance of common denominator proportioning, tempo substitutions, or simply by instinct, and indeed the degree to which rhythmic accuracy is prioritized, will have a significant effect on the aesthetic result, particularly when it is heard in relation to the shifting densities of electronic music.

In terms of dynamics, the earliest recordings by Mercenier and Tudor feature the broadest range of colours and contrasts (hear, for example, their similarly clear and accurate distinctions in bars 39–41: Mercenier, 2′44″–2′52″; Tudor, 1′34″–1′38″). Elsewhere, the extreme range of Tudor's playing can be heard in his differentiation of attacks in Crux II (0′42″–0′52″), and consecutive fff, pp, and ff contrasts in bar 33 (1′20″–1′25″), enhanced by the expansive dynamic capture of the recording. This range foregrounds the disjunct quality of melodic profiles, drawing greater attention to the momentary effect of individual tones and groupings.

In contrast, Kontarsky, Wambach, and Corver exhibit a mixture of dynamic precision in certain passages, and attenuation or even reversal of contrasts in others. This is apparent from the outset in Kontarsky's recording, with almost no sign of the idiomatic contrasts in bar 1 (0′00″–0′08″). However, in most instances, notated contrasts, while clearly attenuated, can still be discerned, contributing to the prevailing sense of lyricism and phrasing, supported by a predominating legato touch, that characterizes his playing. This approach is shared by Corver, who, in addition to the aforementioned lyrical tendencies in her rhythmic interpretation and broad attenuation of contrasts, occasionally projects quieter notes, thereby fostering longer melodic connections. A good example of this is her significant playing up the piano B♭ of attack 40.1, whereby a clear registral link with the climactic ‘cadential’ chord of bar 42 is established, accentuating the implied linear drive of the upward melodic trajectory and diminishing note values.Footnote 71

Prioritization of melodic line is also recognized by Iryna Krytska as an important feature of Kontarsky's playing in Klavierstück XI, which she attributes to his technical training and continuing role as a regular performer of both avant-garde and traditional repertoire,Footnote 72 a role notably shared by Corver, who regularly performed classical repertoire while working with Stockhausen.Footnote 73 Krytska also sees the influence of this background in Kontarsky's measured performance of grace-notes in Klavierstück XI, which she contrasts with Tudor's breakneck execution,Footnote 74 with similar contrasts appearing in the interpretation of Cruxes by these pianists in Klavierstück I. Incidentally, this is a feature, in addition to Corver's refined sense of metric proportion, that distinguishes her supervised recording from that of Kontarsky, as her Cruxes, most notably Crux I, are significantly more explosive and virtuosic than those of her predecessor.

Following Kontarsky, Henck's recording is considerably more varied in terms of touch and dynamics. This is made possible by his significantly slower tempo, inhabiting a middle-ground of sorts between the lyricism of Corver and Kontarsky and the momentary beauty of Tudor's physical approach. Henck's pervasive variety of dynamics is particularly effective when contrasted with the mechanistic quality of periodic, dynamically uniform groups (hear, for example, his interpretation of bb. 7–8, 0′25″–0′40″), thereby maximizing the opposition of homogeneity and heterogeneity that is central to Stockhausen's own analysis.Footnote 75 This sensitivity is also evident in Schleiermacher's similarly slow recording, with characteristic softening of the loudest markings foregrounding the subtle distinctions of his quiet and mid-range playing. Thus, Tudor, Henck, and Schleiermacher showcase the potential for clarity and distinction of dynamics at the lowest volumes, enhanced by the technical capture of their recordings, in contrast to the occasionally fragile tone exhibited by Liebner and Chen, and the less expansive range of Kontarsky and Corver.

As noted, the dynamic stratifications of chords in bars 11 and 54 are not precisely realized in any of the recordings. Interestingly, Mercenier (1′38″–1′42″), Klein (0′34″–0′38″), and Liebner (0′38″–0′42″), split the bar 11 chord, performing the lower D–E dyad either before or after the upper voices, thereby achieving some degree of dynamic distinction.Footnote 76 Hand size may factor into this decision, allowing the left to assist the right in performance of the augmented ninth and awkward inner voicing of the chord. Regardless, this practice goes some way towards conveying the dynamics as notated, albeit lacking distinctions between mf, f, ff, and fff in the upper chord. As a corollary, a distinct rhythmic variation is created, affecting an echo of the preceding triplet gesture, while attenuating the impact of the chord as the longest duration of the piece thus far, and as a procedural mirror to the accumulations of the opening group.Footnote 77

As discussed, the minimal articulation markings and frequent impossibility of executing a default legato without the assistance of the sustaining pedal in Klavierstück I offer the pianist much creative responsibility and freedom. This is borne out by the corpus of recordings, each of which displays a unique approach to articulation and pedalling.Footnote 78 Klein, for example, brings aesthetic variety to certain periodic figurations, using a number of unnotated slurs and staccatos in bars 7 (0′20″–0′26″) and 19 (0′53″–0′56″) to break the implied continuity of beamed pitches into irregular groupings. Elsewhere, articulation is used as a means of establishing localized connections or, conversely, exaggerating separation of material in a range of contexts. For example, Mosell's quasi-tenuto ‘full stop’ execution of the final fff demisemiquaver B♭ of bar 2 clearly demarcates the arching Gestalt of the opening bars (0′12″–0′17″), while Henck's crisp, upbeat articulation fosters continuity by anticipating the minim dyad of bar 3 (0′07″–0′15″). Bar 4 introduces another set of common articulative choices, relating to the connection or separation of adjacent pitch material, explicitly directed in this instance by a slur. Where the majority of performers ignore this detail, Henck slightly separates attacks 4.1 and 4.2, creating a subtle sense of syncopation, enhanced by his delicate distinctions of pp and p (0′16″–0′20″), which is then contrasted with the loudness and physicality of Crux I.

In addition to near universal observation of the seven pedal markings in the score, many of the recordings feature use of the pedal to forge legato connections and to contribute localized colour. According to Benjamin Kobler, who worked extensively with Stockhausen in his later life, the composer insisted on additional colouristic use of pedal in the Klavierstücke, asking him, for example, to add ‘dabs’ to each of the isolated attacks in bar 2 of Klavierstück I, thereby reducing the inherently dry pointillism of the figuration.Footnote 79 Wambach's playing is particularly striking in this respect, with the audio fidelity of his recording allowing for finer appreciation of timbral details, including the use of sustaining pedal to establish internal connections within Cruxes (hear, for example, his subtle linking of tones in Crux I, 0′20″–0′23″) and to enrich and balance high attacks, in particular the G♯ of attack 28.3 and the D of attack 31.2 (1′30″–1′40″). Taking an alternative approach to the same passage, Chen avoids clearing the pedal at all following the misterioso effect of bars 24–27, thereby minimizing textural contrast (1′11″–1′25″). She then takes the opposite approach by disregarding Stockhausen's pedal marking at bar 50, affecting a crystalline textural juxtaposition with the pedalled material of the preceding bars (1′59″–2′05″). Finally, Schleiermacher makes interesting use of the pedal to exaggerate elisions, such as those between attacks 4.6 and 5.1 (0′16″–0′20″), between the final chord of Crux I and the pp downbeat dyad of bar 7 (0′21″–0′25″), and most strikingly between the ff F♯ of attack 23.5 and the pp downbeat A of bar 24 (1′28″–1′32″). This last technique, first witnessed in Henck's recording (1′35″–1′39″), addresses the problematic juxtaposition of the ff triad of attack 23.5 and the fragile pp tone of attack 24.1, allowing the latter to emerge from the former, in a manner reminiscent of electronic noise filtering.

The corresponding transitions between loud, unpedalled material and pedalled pp semiquavers in bars 23–4 and bars 47–8 have been interpreted in a number of ways. In contrast to Henck and Schleiermacher's creative elision, for example, Mercenier (2′09″–2′16″) and Wambach (1′18″–1′26″) introduce a large break between bars 23 and 24, allowing for the sound of the low ff F♯ to clear entirely before the semiquavers commence, thus affecting a clear structural break. These breaks are accentuated in Klein's recording by a significant reduction of tempo as the semiquavers begin in both instances (1′00″–1′16″ and especially 1′50″–2′00″), further exemplifying her idiosyncratic but effective tendency to reduce tempo in localized contexts. Crucially, the consistency of these techniques helps to establish structural coherence, enhanced by consistent approaches to interpretation elsewhere, which together have a bearing on the emergence of different performance styles and the quality of the serial aesthetic.

Conclusions

In a wide-ranging article on notation and interpretation, originally written while working as Stockhausen's assistant on the realization of Carré (1959–60) for four orchestras and four choirs, Cornelius Cardew, himself an accomplished pianist, summarized the role of the performer of 1950s Darmstadt serialism:

The music seemed to exclude all possibility of interpretation in any real sense; the utmost differentiation, refinement and exactitude were demanded of the players. Just because of this contradiction it is stimulating work, and sometimes rewarding to interpret this music, for any interpretation is forced to transcend the rigidity of the compositional procedure, and music results.Footnote 80

Writing in 1963, Leonard Stein paints a similar picture, noting how ‘the role of the performer becomes that of one removed; once he has mastered his responses as accurately as possible, according to the details of serialization, he must then strive to articulate the sections and discover what contrasts exist’,Footnote 81 and in his later dissertation on the performance practice of twelve-tone and serial music, with specific reference to Klavierstück I, how ‘the performer's main task … is essentially that of relating groups and like occurrences so that the structure is ultimately revealed’.Footnote 82 These statements corroborate Mathew's and Duncan's view of literalism in the historic performance practice of serial music, while looking to the frontiers that lie beyond: they describe an ethics of performance that takes literalism as a starting point rather than an end point. The questions remain, however, given the agency involved and how patently different each of the eleven selected recordings of Klavierstück I are, how does one arrive at personal judgements of value and taste? How might one interpret performances? How should one decide what lies within the bounds of acceptable interpretation on the part of the performer?

In a spontaneous 1992 lecture on his early piano music, Stockhausen advocated an idealized mode of listening, whereby the listener becomes so familiar with the pieces that they are able to simulate the gestures and keystrokes of the performer during audition.Footnote 83 While this may seem unrealistic and symptomatic of Stockhausen's desire to control even the way in which his music is experienced, it points towards the importance of an embodied understanding of serial music. As Mine Doğantan-Dack argues, ‘music needs to be understood as constituted both by abstract structures and performance movements, both by the score and its performances; and musical meanings are emergent in the processes of listening, performing and composing, where the abstract and the concrete are in continual interaction’.Footnote 84 In early serial music, and in light of the dialectical relationship of instrumental and electronic composition, this takes on a further dimension, with the performer's defamiliarized, often virtuosic physical movements gaining in significance and independence of meaning. Mathew's characterization of the performer as an ‘organic tape player’ and insistence on the metaphor of the ‘vanishing performer’ is thus extremely unhelpful, and, in light of Stockhausen's mission statement for the Klavierstücke, cited at the beginning of this article, sorely misguided. Hence, while Stockhausen's advice may seem out of reach for even the well-informed listener, an awareness of the defamiliarized gestures of serial music in performance is an important first step towards understanding, which my analysis aims to support.Footnote 85

If Stockhausen's proposed level of familiarity seems idealistic, it is at least reasonable to suggest that one knows the music well enough to recognize blatant errors of pitch, which can be heard in certain recordings of Klavierstück I. For an experienced listener, these soon become obvious and problematic, just as they would in recordings of traditional repertoire. Such errors are different in kind, however, to those witnessed in Mercenier's and Tudor's performances of virtuosic material. While Mercenier's splashiness during Cruxes may be attributed to live performance nerves, Tudor's comparable inaccuracies are indicative of an explicit performance ethos, expressed to Stockhausen shortly after his first performances of Klavierstücke I–IV in New York in a letter dated 3 February 1955:

My pianistic method involves (usually) doing things with a precise control, as fast as this control can be exercised; and at that point to push beyond into an area where control might be lost (or forgotten) and where the act of playing becomes a ‘dangerous’ matter.Footnote 86

In this sense Tudor's approach comes closest to a literal realization of the direction ‘as fast as possible’, inhabiting a dangerous space which may occasionally stray into performance that is ‘faster than possible’.Footnote 87 As Stockhausen's enthusiastic reaction to Tudor's performances and praise of his methods in their correspondence indicates, this is much closer to the way that the performance of serial music was actually conceived in the 1950s, that is, as experimental, irrational, physically mediated, and gaining meaning in its opposition to the fixed inscriptions of electronic music. Far from vanishing, the performer becomes extremely present under these circumstances. This experimental style (experimental in the sense that by playing at the limit of their capabilities the performer enters into each performance not fully aware of what will result) is what might more accurately be described as ‘Darmstadt pianism’, or simply the historical performance practice of Darmstadt serialism. This style of performance is also inimical to recording and the associated practice of repeated listening, wherein instrumental serialism loses its ontological distinction from the inscribed quality of electronic serialism;Footnote 88 experimentalism such as Tudor's, while valuably documented, demands the unforeseeable, irrational experience of the live musical event.

Kontarsky's approach, later refined by Corver, marked the emergence of a second, classical style of performance, which foregrounded the latent melodic content of serial scores, with a concern for higher level relationships and macro-structure. Shortly prior to the release of Kontarsky's recordings, Stein outlined the tenets of this practice with reference to Klavierstück I, noting how ‘changes in tempo, density, emphasis on certain tones – even the appearance of occasional motives and imitations – may be considered by the performer to be more than just fortuitous happenings, and should also be taken into account so that he does not react as a mere automaton but discovers, instead, relationships of a higher order than those inherent in the “serial” system itself’.Footnote 89 This requires an attenuation of the many subito contrasts that populate Klavierstück I, superficially aligning this style of playing with the modernist objectivity that Mathew describes. However, as Cook's nuanced reassessment of this style in performances of Webern's Variations attests, this approach to the score, in itself an interpretive choice, retains much of musical interest, and in the case of serial music offers a clear alternative to the practice of the 1950s. In terms of listening practice, the auditor attuned to this style of performance will gain from creative and comparative listening to the melodic fortuities of the music that are projected, consciously or otherwise, by the performer.

Henck's approach marked the emergence of a third, analytical style of performance in the 1980s, also witnessed in the recording of Wambach and to a lesser extent in the later recording of Schleiermacher, characterized by slower tempi and a focus on extreme clarity and variety of detail. This may be seen as an embrace of the manifold, interrelated continua of Klavierstück I's parametric composition, calling for fine differentiation of durational and dynamic values (the latter of which offer the bare bones of a continuum) and a creative approach to the management of articulation. The decision to omit articulation markings in Klavierstück I, which, along with its rhythmic innovations and grouping of material, sets it most clearly apart from Mode de valeurs and Structures I, allows the performer a strong hand in shaping and communicating this over-arching continuum, itself a function of dynamics and duration, as illustrated by the variety of these three recordings. The choice of cover art by serial artist Paul Lohse (see Figure 18), and the inclusion of Lohse's 15 Principles of Serial Orders 1943–4 in the liner notes to Henck's recordings of Klavierstücke I–XI, as well his extensive serial analyses of Klavierstücke IX and X,Footnote 90 suggest thinking in these terms and a keen awareness of the multidimensional principles of serial composition. Above all, these recordings foreground the micro-aesthetic qualities of the music, which rise to prominence in relation to the macro-aesthetic whole.Footnote 91 This calls for a third approach to listening, diametrically opposed to that of experimentalism, which, rather than taking each musical event as unique and transitory, seeks to discover ever finer expressive nuances and gradations of formal equilibrium through repeated close listening to individual recordings.

Figure 18 (Colour online) Cover art for Henck's Klavierstücke I–XI recordings, featuring Paul Lohse's Fifteen systematic colour rows with vertical and horizontal compression. Used by permission of Schott Music & Media GmbH/Wergo.

Uniting these styles of performance and suggested modes of listening, and ensuring the interplay between them, is the tension that exists between the manifold parametric extremes of Klavierstück I. This is the aesthetic component of serialism that distinguishes it most clearly from thematicisim. As Grant writes, ‘serialism is based on a tension fraught with expectation’, as opposed to that of American experimental music, which guides the listener towards ‘non-expectation’.Footnote 92 This tension is different in kind to that of thematic music, in that it is not predicated on resolution, existing rather in constant anticipation of the unforeseeable.

Arguably the most striking tension in Klavierstück I, and that which is felt most keenly by its absence, is that between its rhythmic proportions. In her recent teaching at the biennial Stockhausen Courses, Corver advised that all metres in Klavierstück I should be reduced to a unified crotchet pulse, relating back to the 1–6 beat crotchet metres of Stockhausen's original scheme,Footnote 93 inspiration she first took from hearing Stockhausen singing the opening of the piece while tapping crotchet time during a masterclass.Footnote 94 The ‘tempi’ of the variegated tuplets may then be felt in relation to this basic pulse. My own experience has shown this to be a highly effective way of internalizing proportions and maintaining rhythmic tension. As my analysis has illustrated, this tension exists in many different states within the recordings, naturally depending on working methods and the prioritization of accuracy. Once one has a feel for this tension and the relationship of groups as a listener, these differences and other details – Stockhausen's ‘irrational nuances’ – come to the fore. It also becomes clear when rhythmic tension is lacking, as in the case of Chen and Liebner, whose interpretations tend towards a general homogeneity, at odds with the multidimensional tenets of serial aesthetics.Footnote 95 In Klein's case, meanwhile, these characteristics are pushed to such an extreme, and combined with such imaginative playing, that something quite unusual and to my ears very interesting emerges.

As noted, Stockhausen's comments regarding the listening experience could be used to support the view of authoritarian control cited by Mathew and Duncan and echoed by many who have worked with the composer.Footnote 96 Control of the performer was undoubtedly a persistent theme in Stockhausen's writing, yet it appeared in many different states, and tended to develop in response to practical outcomes. Within Klavierstücke I–XI, for example, the limited affordances of Klavierstücke V and VII tend towards similar results in literalist performances, with ‘irrational nuances’ of expression reduced to the micro-aesthetic plane (hear, for example, the similarity of Kobler's and Corver's recordings of Klavierstück VII), while the more open, complex affordances of Klavierstücke I, VI, X, and XI, each demanding their own bespoke practice, leave enormous scope for interpretation, with less direct control of the results on the part of the composer.Footnote 97 This reflects the sui generis nature of serial compositions, and indeed of much new music, both in terms of composition and performance practice; it is also partly why the serial moment developed so quickly.

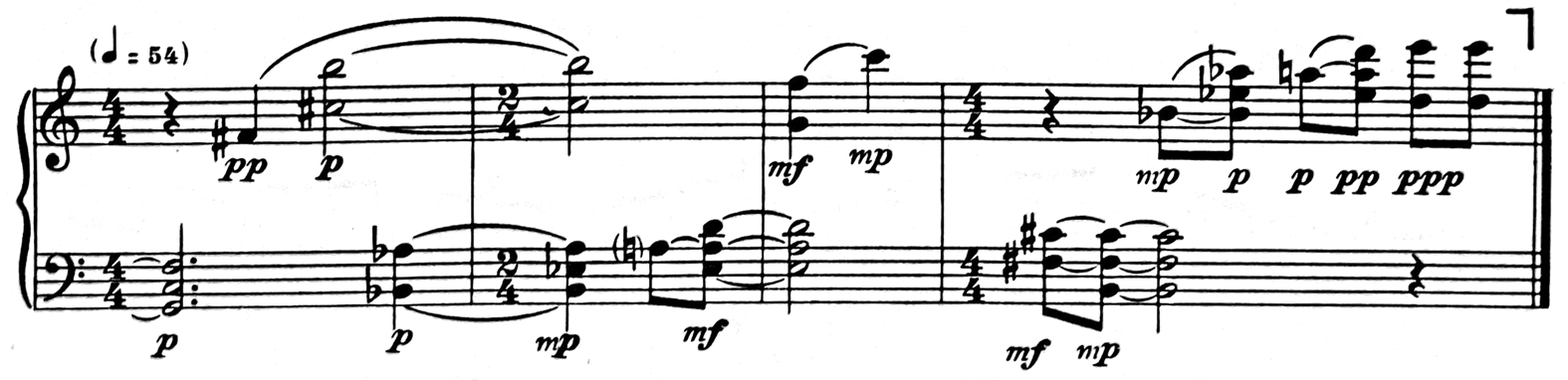

Stockhausen's talent for defamiliarization, combined with a persistent and empirically regulated sense of idiom, was key to his ongoing success. One of the issues that Adorno may have recognized in listening to Stockhausen and Karel Goeyvaerts perform the latter's Sonata for Two Pianos at the 1951 Darmstadt CoursesFootnote 98 was the contradiction between the traditionally expressive and the rationalized, similar to the critique made by Boulez of Schoenberg's archaic forms, unsuited to the novelty of the musical material.Footnote 99 In Goeyvaerts's Sonata, as well as other early parametrically organized works such as Babbitt's Three Compositions for Piano (1948), phrasing remains broadly traditional and the writing idiomatic, with the parametric micromanagement of dynamics designed to precisely control the performer's interpretation along familiar lines (see Examples 6 and 7). Stockhausen's registral, textural, and dynamic reformulation of Goeyvaerts's scheme in Kreuzspiel Footnote 100 and his radical, frequently contradictory writing in Klavierstück I are emblematic of his role in advancing beyond the stagnation of this early moment, and the limitations of a modernist approach to performance, unsuited to the new music.

Example 6 Karel Goeyvaerts, Sonata for 2 Pianos, Op. 1, bb. 4–6. Used by permission of Donemus Publishing.

Example 7 Milton Babbitt, Three Compositions for Piano, II, bb. 101–4. Copyright © 1948 Boelke-Bomart, Inc. Copyright © renewed. Used by permission.