Increasing life expectancy is changing the age structure of populations across the world. For example, in the UK, adults aged 65 years and over represented 17·8 % of the population in 2015; current projections are that this figure will rise to 24·6 % by 2045(1). Set against expected population growth over this time, the numbers of older adults will grow significantly. However, to date, the changes in life expectancy have not been mirrored by comparable changes in healthy life expectancy, and in most countries, there have been increases in the number of healthy life years being lost to disability(Reference Salomon, Wang and Freeman2). The need to address this gap in morbidity has focused attention on the role of lifestyle and health behaviours, including nutrition, and their links to the ageing process, with a view to considering strategies to promote healthier ageing(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3). This review considers the importance of nutrition in older age and potential opportunities and approaches to support older adults to improve nutrition and health.

Age-related changes in food and nutrition

Alongside declining activity levels, age-related falls in food consumption are expected in later life, and are well documented. The differences in energy intake across adulthood are significant. In a recent analysis of energy intake data from healthy older (around 70 years) and younger (around 26 years) adults, a difference in energy intake of approximately 16–20 % was shown between the groups, amounting to a reduction of about 0·5 % per year(Reference Giezenaar, Chapman and Luscombe-Marsh4); this compares with previous estimates of a fall in energy intake of about 25–30 % between young adulthood and older age(Reference Giezenaar, Chapman and Luscombe-Marsh4, Reference Nieuwenhuizen, Weenen and Rigby5). There are a number of age-related physiological changes, which include more rapid and longer satiation, dental and chewing problems, being less hungry and thirsty, and impairments in smell and taste, that can act to change eating behaviour. Older adults may eat more slowly, consume smaller meals and snack less, leading to lower food consumption and ultimately, to weight loss(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3–Reference Nieuwenhuizen, Weenen and Rigby5). These changes may be compounded by effects of comorbidities and medication that cause loss of appetite. Described as the ‘anorexia of ageing’, arising from the loss of appetite and/or falling food consumption, this is both common in older adults, and known to be an independent predictor of adverse health outcomes(Reference Landi, Calvani and Tosato6). However, ahead of dietary changes that result in significant weight loss, declining food consumption can still affect the nutritional risk of older adults. Unless more nutrient-dense foods are selected at the same time as overall changes in the level of food consumption are occurring, falling food intake will result in lower nutrient intakes in parallel with energy intake, making it more challenging for older adults to meet their nutrient needs(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3, Reference Wakimoto and Block7). Importantly, although energy requirements are lower in older age, the requirements for many other nutrients may not change, or may even increase. Consistent with the possibility of an increasing nutritional risk, many studies of older adults describe insufficient intakes of a range of nutrients, which include protein, fibre and a number of micronutrients(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3). At a time of falling food consumption, and changing nutrient requirements, consumption of nutrient-dense foods and having a diet of adequate quality are key to ensuring older adults meet nutrient needs(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3).

Diet quality in older age

In common with younger age groups, there is huge variability in food choices and quality of diet among older adults(Reference Robinson, Syddall and Jameson8–Reference Savoca, Arcury and Leng10). Some of this variability is linked to differences in background characteristics such as education, gender and ethnicity(Reference Robinson, Syddall and Jameson8–Reference Savoca, Arcury and Leng10), but much is unexplained, and the influence of ageing on diet is not well understood. An important gap in current understanding is that much of the evidence is cross-sectional, and little is known about trajectories of change in diet quality in later life and how age-related factors impact on individual food choices(Reference Lengyel, Jiang and Tate11). In two recent studies of older adults, followed over 3 years in Canada(Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller12) and over a decade in the UK(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson13), average diet quality did not change substantially between baseline and follow-up assessments. However, these average figures mask sizeable decreases in diet quality for some participants in both studies, particularly among older women. Comparable messages about poorer diet quality have come from a number of studies of older adults, in which monotonous diets of lower diversity and quality have been reported(Reference Bartali, Salvini and Turrini14, Reference Irz, Fratiglioni and Kuosmanen15). Such patterns of diet, and changes in the balance of nutrient-dense foods v. foods that are less dense, can contribute to lower intakes of protein and micronutrients(Reference Bartali, Salvini and Turrini14, Reference Roberts, Hajduk and Howarth16). As the need for a more nutrient-dense diet may coincide with a time when physical limitations are starting to impact on food access and availability, these changes are likely to affect nutritional risk. Additionally, alongside concerns regarding insufficient nutrient intakes, there is also a significant body of evidence that links lower diet quality in older age to an array of poorer health outcomes, which include increased risk of CVD and cancer(Reference Hlebowicz, Drake and Gullberg17–Reference Schwingshackl and Hoffmann19) and to declines in physical function(Reference León-Muñoz, García-Esquinas and López-García20). This has obvious implications for healthy life expectancy in older age, and raises further concerns about older adults who currently have poor diets.

Estimates of the prevalence of low diet quality in older age vary according to methods of assessment and definitions used, as well as to differences in study populations. In an analysis of data from four European countries (Finland, Sweden, Italy, UK), overall diet quality (defined using a diet quality index) was found to be relatively poor, with few participants achieving the maximum scores(Reference Irz, Fratiglioni and Kuosmanen15). This is echoed in findings from the USA. For example, in a study of older independent adults living in New York City, 73 % of women and 78 % of men did not have diet scores that achieved the HEI-2005 (>80) that is defined as ‘good’(Reference Deierlein, Morland and Scanlin9); among a study of rural older adults, the prevalence was even higher, with an equivalent figure of 98 % of older participants studied(Reference Savoca, Arcury and Leng10). Although all of these studies highlighted considerable heterogeneity in diet quality in the study populations, and wide ranges in scores for the dietary indices used, the studies are consistent in their overall message that poor diets in contemporary older populations are common. Importantly, in each case, they identify sizeable groups of older adults, living independently, who are likely to be at nutritional risk.

Malnutrition

Low food intakes and poor diet quality maintained over a prolonged period can lead to lower nutrient status and weight loss. In recent years, the development of validated tools, which are now widely used to identify and define malnutrition(Reference Neelemaat, Meijers and Kruizenga21, Reference Hamirudin, Charlton and Walton22), have led to its clearer recognition as an issue in older populations, as well as to improved understanding of its health consequences and related economic costs. An important contribution to improving awareness has been the provision of data to enable estimates of prevalence in the population. In England, an estimated one in ten older adults are currently at risk of malnutrition, defined using the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool(Reference Stratton, Hackston and Longmore23), a figure that rises to one in three older adults on admission to hospital(Reference Elia24). The poorer health outcomes associated with malnutrition have been described in many studies, including greater risk of complications, longer hospital stays and increased mortality(Reference Naseer, Forssell and Fagerström25–Reference de van der Schueren, Elia and Gramlich27). Thus, apart from the huge costs to the individual who is malnourished, there are significant incremental healthcare costs associated with malnutrition. For example, the most recent estimate of public expenditure on malnutrition in health and social care in England amounted to £19·6 billion, with older adults accounting for 52 % of this figure(Reference Elia24). Given the changing age structure of populations in England and across the world, without effective strategies to prevent malnutrition in older age, future expenditure is likely to be unaffordable.

Progress has been made in nutrition screening of older populations to define malnutrition risk. Screening can improve nutritional status when it is timely and supported by appropriate care and continued monitoring(Reference Hamirudin, Charlton and Walton22). Although key components of many screening tools are thinness (low BMI) and unintended weight loss, individuals categorised as being at greater risk of malnutrition in this way have been shown also to be more likely to have lower micronutrient status(Reference Margetts, Thompson and Elia28). Similarly, in a recent review of data from five studies of community-dwelling and institutionalised older adults, malnutrition status, defined using the MNA (mini nutritional assessment), was found to be associated both with nutrient intake and with diet quality(Reference Jyväkorpi, Pitkälä and Puranen29). However, an important finding from the latter study was that low energy and protein intakes, and insufficient micronutrient intakes, were common in older participants whose nutritional status was defined as normal using this tool. The authors conclude that the screening tool, which was not designed to describe low diet quality and suboptimal nutrient intakes, may not identify older adults who have poorer intakes, and that additional tools, such as dietary assessment, should also be used in order to recognise nutritional risk(Reference Jyväkorpi, Pitkälä and Puranen29). As the vast majority of malnourished individuals are community-dwelling(Reference Elia24), this finding has important implications for screening approaches to identify falls in diet quality and food consumption in older age, occurring ahead of significant changes in nutrient status and weight loss. Recognising these early signs of declining nutrition among older independent adults may be key to effective preventive strategies in the future.

Identifying opportunities for prevention

The development of community-based interventions, to support older adults to ensure nutrient needs are met, requires a clear understanding of the influences that affect dietary choices and habits in older age, and the factors that determine diet quality and the amounts and types of food eaten. Although some influences on diet are common to younger and older age groups, including positive effects of education and female gender on diet quality(Reference Robinson, Syddall and Jameson8, Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller12, Reference Irz, Fratiglioni and Kuosmanen15, Reference Atkins, Ramsay and Whincup30, Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller31), there is also evidence to suggest that specific factors may be particularly important in older age. For example, in the study of diet quality among older adults in four European countries, living alone was consistently associated with poorer diets(Reference Irz, Fratiglioni and Kuosmanen15). Other significant messages from this study were firstly that poor diet quality was not simply explained by insufficient resource in the older populations studied, and secondly that chronological age contributed little to explaining differences in diet quality. The lack of observed age effects on diet may be consistent with recognised differences between biological and chronological ages(Reference Lowsky, Olshansky and Bhattacharya32, Reference Martin-Ruiz and von Zglinicki33), but it emphasises the need to understand the roles and importance of age-related factors as determinants of food choice and diet quality to be able to inform the design of the interventions that are needed to support older adults(Reference Host, McMahon and Walton34).

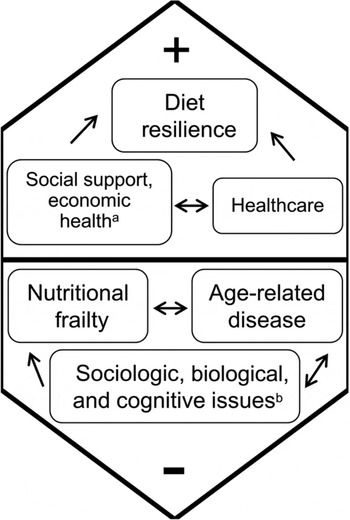

In their review of factors that affect the nutritional health of older adults, Shlisky et al. set out a model that brings together the diverse influences that have both positive and negative effects (Fig. 1)(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3). Alongside the negative effects of age-related physiological factors, such as loss of appetite, this model also highlights the positive role of social factors such as social support and social interaction, and effects of psychological factors such as resilience(Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3).

Fig. 1. Factors with positive and negative influences on nutritional health, including alack of social interaction, economic factors leading to food insecurity, as well as bage-related physiological changes, such as loss of appetite. From Shlisky et al. (Reference Shlisky, Bloom and Beaudreault3).

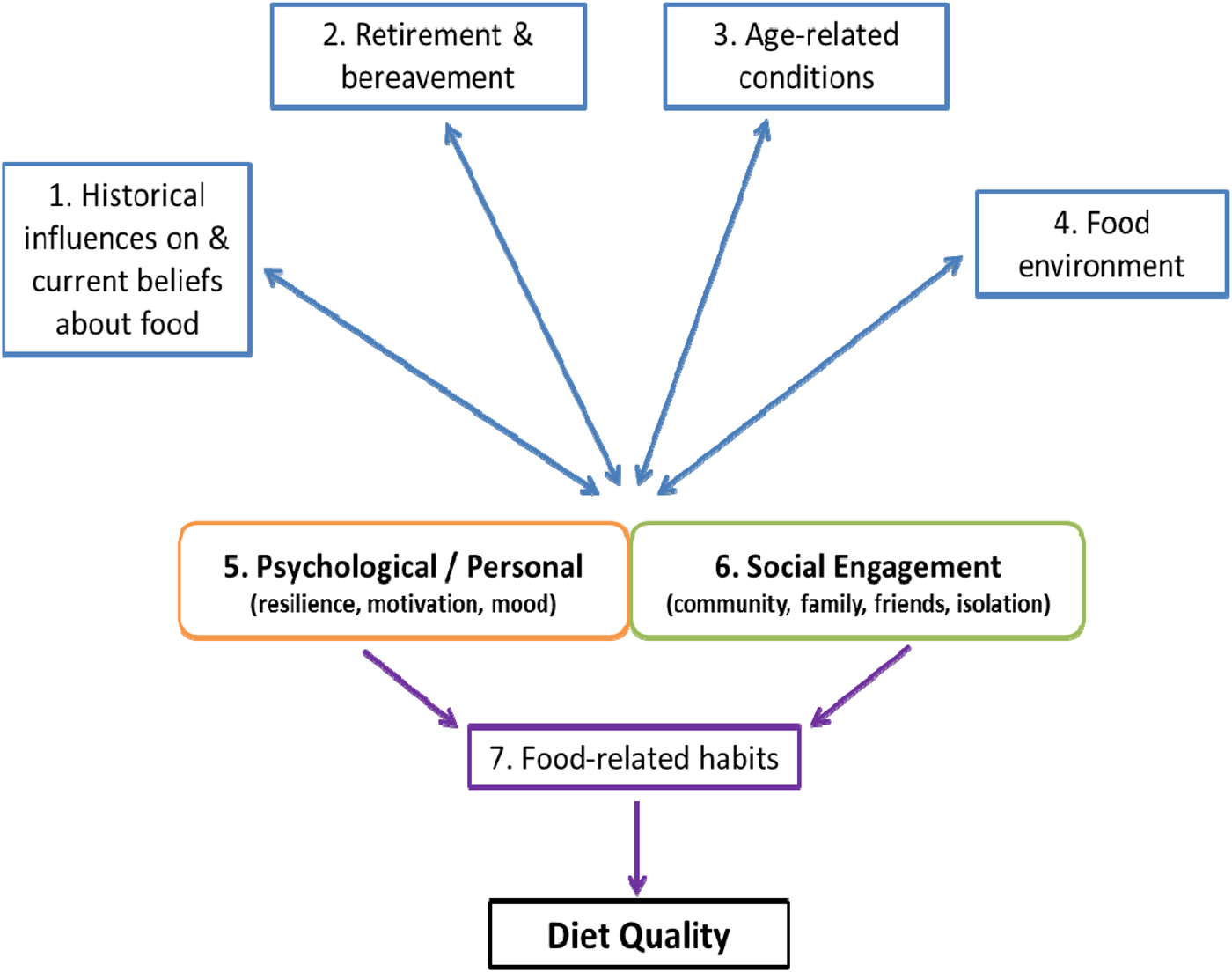

The role of social and psychological factors as determinants of nutritional health have been described in a number of studies, and their importance within the complex range of influences that affect diet and health in older age has been described in other studies(Reference Host, McMahon and Walton34–Reference Tyrovolas, Haro and Mariolis36). For example, in a recent systematic review of factors that influence food choice in older independent adults, qualitative analysis of twenty-four studies identified three broad domains: physiological changes associated with ageing, psychosocial aspects and personal resources(Reference Host, McMahon and Walton34). However, some of the evidence of effects of social and psychological factors is fragmented, and less is known about their mechanisms and how these factors interact to affect individual trajectories of nutritional health(Reference Shatenstein, Gauvin and Keller31, Reference Host, McMahon and Walton34, Reference Bloom, Lawrence and Barker37). In a recent qualitative study of older (74–83 years) community-dwelling adults in the UK, the nature of these interactions was explored(Reference Bloom, Lawrence and Barker37). Thematic analysis of focus group discussions showed that a number of age-related factors were linked to differences in patterns of food consumption and diet quality, which included bereavement and medical conditions. However, the variability described in individual responses to these influences suggested that psychological and social factors may act by mediating or conditioning ageing effects on diet(Reference Bloom, Lawrence and Barker37). The proposed relationships that describe these interactions are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. (Colour online) Hypothetical model of the relationships between themes and potential routes to impact on diet quality in older age. From Bloom et al. (Reference Bloom, Lawrence and Barker37).

For example, discussion about ‘keeping going’ and other examples of coping strategies pointed to the importance of psychological factors in determining individual responses to age-related changes in physiology and context, and discussion about social activities highlighted the positive role of social engagement. Such differential effects of age-related factors suggest that they could act both as barriers or facilitators to maintaining diet quality in older age, and they may also contribute to some of the inconsistencies seen in the findings of intervention studies to improve nutrient intake in older populations(Reference Bandayrel and Wong38, Reference de van der Schueren, Wijnhoven and Kruizenga39). To understand the implications of these findings for the design of future interventions, more needs to be known about their effects, and how they affect food consumption(Reference Host, McMahon and Walton34).

Social factors

Social factors, such as level of social engagement, size of social network and support, marital status and whether living alone, have been linked to differences in diet in a number of studies of older adults(Reference Conklin, Forouhi and Surtees40–Reference Sahyoun and Zhang43). In general, greater number and quality of social relationships and contacts are associated with better diet quality. This may be linked to positive psychological states that encourage healthier behaviours(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson13), and consistent with positive effects of supportive social environments on health(Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton44). In particular, living alone is identified as a risk factor for poor nutrition(Reference Host, McMahon and Walton34). However, there are differences in findings across studies, including lack of associations observed in some groups(Reference Pieroth, Rigassio Radler and Guenther42, Reference Holmes and Roberts45). While some of these differences may be explained by the background characteristics and health of participants studied, sex differences appear to be particularly important(Reference Conklin, Forouhi and Surtees40–Reference Pieroth, Rigassio Radler and Guenther42). For example, in a large study of older adults from the EPIC-Norfolk prospective cohort in the UK, the influence of marital status and living arrangement on fruit or vegetable variety were greater for men than for women(Reference Conklin, Forouhi and Surtees40). Some social factors, such as level of social engagement, are amenable to change and they may offer opportunity in terms of interventions to promote better diet quality. Social network interventions are already being used to support adults who have long-term conditions(Reference Kennedy, Vassilev and James46), and may be an effective approach for the promotion of health behaviours in the general population of older adults. The potential for social interventions to promote nutritional health is supported by recent data from a study of older community-dwelling adults who were participants in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study in the UK. Diet quality was defined by participants’ ‘prudent’ diet scores at baseline (when aged 59–73 years), and in a subgroup who were followed up after 10 years. At baseline, a range of social factors predicted better diet quality score, which included better social support and greater social engagement (identified by greater participation in social and cognitive leisure activities); these associations were seen both in men and women (Fig. 3)(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson13).

Fig. 3. Diet quality scores (prudent dietary pattern (PD)(Reference Robinson, Syddall and Jameson8)) at baseline and 10-year follow-up, according to participation in leisure activities (social and cognitive) at baseline, among older men and women in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson13). Values are mean with 95 % CI indicated by vertical bars.

In comparison, the study found fewer predictors of change in diet quality over the follow-up period. However, in men and women, greater social engagement at baseline was associated with smaller declines in prudent diet scores over the following decade, suggesting that it may have protective effects on diet quality(Reference Bloom, Edwards and Jameson13). These observational findings underline the importance of maintaining social relationships in older age and suggest that supporting older adults to achieve this could be a valuable part of strategies to promote health in later life. They may also point to subgroups in the population who might benefit from additional support, particularly with a view to targeting early preventive initiatives(Reference Schilp, Wijnhoven and Deeg47).

Psychological influences on diet in older age

A body of evidence from younger and older populations links psychological factors to differences in food choice and diet quality, which include psychological wellbeing, self-efficacy and depression(Reference Host, McMahon and Walton34–Reference Tyrovolas, Haro and Mariolis36). For example, greater self-efficacy has been shown to predict adherence to healthier dietary patterns, and to affect ability to change dietary habits(Reference Cuadrado, Tabernero and Gutiérrez-Domingo48). Psychological influences may be key to mediating effects of age-related factors, such as medication and poor appetite, on the diet quality of older adults (Fig. 2)(Reference Bloom, Lawrence and Barker37), with important implications for nutritional risk. One psychological characteristic is resilience. In a population-based cohort in Germany, Perna et al. showed that resilient older adults were more likely to have better health-related behaviours, which included high consumption of fruit and vegetables and moderate–high levels of physical activity, when compared with non-resilient participants(Reference Perna, Mielck and Lacruz49). Importantly, these differences were independent of socioeconomic position and the findings provide strong support for interventions that focus on resilience to promote health in older age. More recently, cluster analysis of data from the Helsinki Birth Cohort, to define resilient and non-resilient older adults, has extended these findings to show differences in intakes of a range of foods among women studied (women with resilient personality profiles reported higher consumption of fruit, vegetables and fish, and lower consumption of processed meats and soft drinks when compared with non-resilient), although comparable differences were not found among men(Reference Tiainen, Männistö and Lahti50). One explanation for the differing findings in the German and Finnish cohorts may be differences in ages of the participants studied: the Finnish adults (average age 61·5 years) are likely to have been assessed before many age-related challenges had been encountered. Consistent with this suggestion, Vesnaver et al. have described the importance of dietary resilience in a group of older participants (73–87 years) from the Canadian NuAge cohort; analysis of semi-structured interviews with these men and women identified strategies used to deal with difficulties in shopping, meal preparation and eating(Reference Vesnaver, Keller and Payette51). Prioritising eating well and ‘doing whatever it takes to keep eating well’ were key themes identified. Consistent messages have also come from a recent study of older community-dwelling adults in the USA (mean age 82·5 (sd 4·9) years) who were categorised according to their nutritional risk, using the dietary screening tool(Reference Greene, Lofgren and Paulin52, Reference Bailey, Miller and Mitchell53). Participants who were classified as being at risk had lower resilience, and lower self-efficacy (fruit and vegetables) as well as higher geriatric depression scores(Reference Greene, Lofgren and Paulin52). These data suggest a clustering of psychological factors among older adults who were at nutritional risk(Reference Greene, Lofgren and Paulin52). Further research is needed, particularly to understand potential bi-directional effects of psychological factors on food choice and diet quality, to determine the focus of future interventions to support nutrition among older adults(Reference Perna, Mielck and Lacruz49).

Lifecourse perspectives

Much of the evidence reviewed here is cross-sectional and based on studies of older populations. As early identification of the declines in food consumption and falls in diet quality, which lead to increased risk of undernutrition, will be key to effective strategies to promote nutritional health in older age, data from longitudinal studies are needed that can inform the timing and nature of interventions to achieve this. There are few studies that have addressed the early determinants of developing nutritional risk among older adults. An important example is the study reported by Schilp et al. (Reference Schilp, Wijnhoven and Deeg47). Using baseline and follow-up data, over 9 years, from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (participants aged 65–85 years), the predictors of incident undernutrition (defined by low BMI or self-reported unintentional weight loss) were examined. A number of factors were linked to incidence of undernutrition, but in a multivariate model, poor appetite and reported difficulties in climbing stairs (<75 years) remained the only independent predictors(Reference Schilp, Wijnhoven and Deeg47). The authors concluded that simple measures could be used to identify subgroups of older adults in the population who are at greater risk of undernutrition, who could benefit from additional support, enabling the targeting of interventions to those at highest risk.

Future longitudinal studies are needed to inform our understanding of the determinants of nutritional risk in older age. However, progress may also come from better recognition of opportunities for preventive strategies that start even earlier in the lifecourse. Partly this is due to the tracking of health behaviours, including diet(Reference Artaud, Sabia and Dugravot54, Reference Robinson, Westbury and Cooper55), such that health promotion efforts at much younger ages have potential to be effective in improving nutrition and health in older age. But alongside such behavioural considerations, the lifecourse approach to understanding health and disease in older age underlines the benefit of slowing age-related falls in function, starting much earlier in adulthood, to preserve functional capacity(56). For example, diets of higher quality in middle age are associated with better measured physical function in older age(Reference Artaud, Sabia and Dugravot54–Reference Hagan, Chiuve and Stampfer57) and dietary pattern trajectory analyses from the China Health and Nutrition Survey showed cumulative benefits of longer exposure to healthier diets in adulthood in relation to glycaemic control (assessed by glycated Hb)(Reference Batis, Mendez and Sotres-Alvarez58).

Earlier health promotion, with the aim of achieving better nutritional health in older age, could easily build on existing strategies, even though messages regarding potential longer term benefits of healthier diets may be more novel. In addition, there may be particular opportunities for behavioural interventions, including the promotion of healthier lifestyles, around the time of transition to retirement(Reference O'Brien, McDonald and Araújo-Soares59, Reference Lara, Hobbs and Moynihan60). Present studies point to the importance, as well as the feasibility and acceptability of participatory approaches to intervention design for community-based research, which involve older people from the concept-planning stages onwards(Reference Evans, Ryde and Jepson61, Reference Patzelt, Heim and Deitermann62). Existing prevalence figures for poor nutrition among older adults in developed settings, together with current population projections, underline the need for further longitudinal data to inform the design of such preventive interventions to address nutritional risk in older populations.

Conclusions

Falling food consumption may put older adults at nutritional risk. Although this highlights the importance of nutrient-dense foods and overall diet quality in older age to ensure nutrient intakes are sufficient, maintaining or increasing diet quality may be difficult at a time when food access and preparation are becoming more challenging and diets may be more monotonous. Poor nutrition, even in developed settings, is common, and malnutrition rates are very high(Reference Elia24). Effective preventive strategies to promote good nutrition among older populations are needed. Design of future interventions to support older community-dwelling adults requires a clear understanding of the personal and contextual influences that affect patterns of food choice and consumption, including consideration of the importance of social and psychological factors. In addition, there are opportunities to intervene earlier in the lifecourse; the most effective preventive efforts to promote good nutrition for healthier ageing may need to start ahead of age-related changes in physiology and function, including younger adulthood and at the retirement transition.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authorship

The author was solely responsible for all aspects of preparation of the present paper.