In the first article in this series (Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams & Garland, 2002) we encouraged readers to try out elements of the Five Areas model of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) with some patients. Before we further discuss the model it might be of value to reflect on your experiences. If you did try, was it successful? Did it teach you anything about your clinical skills and the patients' problems? Can you build on this experience and use the Five Areas model more widely in your practice? If you did not try this out, why not? Were you prevented by internal factors (too busy, could not see the patient, thought you could not do it) or problems beyond your control (the patient failed to turn up)? How can you overcome these obstacles?

The Five Areas model

Cognitive–behavioural therapy enables a structured consultation, provides the clinician with a broad range of techniques to help the patient address his or her current problems and is especially useful in enabling patients to practice these solutions between therapy sessions. This paper will outline how the Five Areas assessment CBT model can be implemented in out-patients, day hospitals and ward-based settings; discuss some of the clinical advantages of this model; and identify potential obstacles to using this approach in everyday practice.

Difficulties of psychosocial interventions for psychiatrists

Despite the many advantages of working with a clear psychosocial model of assessment and management, such psychotherapeutic skills are not widely used in psychiatry. This position is difficult to understand in view of the fact that almost all of the current evidence-based psychosocial interventions were either devised or substantially developed by doctors: psychoanalysis (Reference Freud and StracheyFreud, 1914a ,Reference Freud and Strachey b ); rational emotive–behavioural therapy (Reference EllisEllis, 1962); cognitive therapy (Reference BeckBeck, 1967); family therapy (Reference MinuchinMinuchin, 1974); and behavioural therapy (Reference MarksMarks, 1987).

This article is based on material contained in Structured Psychosocial InteRventions In Teams: SPIRIT Trainers' Manual. Further details available from the author upon request.

Despite this, there has been a general withdrawal by psychiatrists from providing psychosocial interventions. Many factors have contributed to this and include multiple and competing demands upon time, increasing management, audit and training commitments, and very high patient numbers. These clinical demands, coupled with a focus on severe and enduring mental illness, have meant that psychiatrists have often delivered an assessment service, with clinical management being largely risk management coupled with medication prescription. As a result other members of the multi-disciplinary team have often become the main practitioners delivering psychosocial interventions. This pattern is mirrored in psychiatric training. By the time Part II MRCPsych examinations are taken, many trainee psychiatrists are confident in their ability to diagnose and to prescribe safely and appropriately, but they are less confident in their abilities to provide effective psychosocial assessment and management. In part this is due to the pressure on service delivery; however, it is compounded by the fact that psychiatric trainees often receive little specific training on the structure, content or conduct of out-patient sessions.

There are several difficulties caused by this situation. Other team members are seen as the main providers of psychosocial interventions, leaving the psychiatrist as only the expert in diagnosis and prescription. The potential outcome is that psychiatrists may lack confidence and credibility in this area. Furthermore, as psychiatric practice becomes less psychological and more mechanistic, this will result in some clinicians becoming dissatisfied with a career that they were originally attracted to because of the high level of interpersonal contact. If consultant psychiatrists lack training and experience in psychosocial interventions they will be unable to offer effective training in such interventions to their psychiatric trainees. Trainees become the trainers of tomorrow, and the lack of current access to training in this area is likely to become self-perpetuating. This situation is worsened by the fact that senior staff have difficulty finding the time or funding to attend skills-based training events that address this issue. Such training is also not available in many parts of the country. There is also a lack of consultant psychiatrists in CBT who might provide the appropriate clinical supervision and local access to training.

Paradoxically, a related problem occurs when specialist training in CBT has been acquired. Such training often involves the practitioner completing an expensive (in terms of time and money) specialist postgraduate course. After completion of such courses, 71% of practitioners change jobs (Reference Ashworth, Williams and BlackburnAshworth et al, 1999) and many migrate into specialist CBT posts. The consequence is that trained practitioners – whether medic or non-medic – are not integrated into generic clinical services, thus reducing the formal and informal dissemination of necessary clinical skills in psychosocial interventions within these settings.

A further difficulty is that the traditional language of CBT is highly technical and therefore inaccessible to those without specialist training. This hinders the dissemination of CBT skills within the generic mental health workforce. It also causes problems for clinicians new to the principles and practices of CBT, who must ‘translate’ concepts such as dysfunctional assumptions and selective abstraction in order to utilise their knowledge clinically. So the language used not only affects clinical work with patients, but can also affect the take-up of CBT skills across health service settings within both primary and secondary care.

Training initiatives

Government-led initiatives such as the Mental Health National Service Frameworks in England and Wales (Department of Health, 1999), coupled with the recent Treatment Choice in Psychological Therapies and Counselling (Department of Health, 2001), have bought the above issues sharply into focus. The College is well aware of the challenge this poses and has laid out new guidelines for senior house officer (SHO) training. By 2003, new SHOs will be able to sit Part II of the MRCPsych examination only if they have gained supervised practice in a time-limited, short-term psychological intervention (8–16 session). This includes one case using CBT, with the further requirement of treating one individual long-term (12–18 months), which can, if desired, be CBT in focus (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001).

These new training initiatives will require the development of new training structures giving doctors access to CBT training using an approach that allows the integration of CBT skills into routine clinical practice. This can be achieved by teaching an integrated approach of assessment and treatment that incorporates both diagnosis and formulation of problems from a psychosocial perspective within a CBT framework. This will enable trainees to use the skills, not just in the longer 1-hour sessions labelled as CBT, but also within their general clinics where CBT skills are essential.

An everyday CBT model – the Five Areas assessment model (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001a ) – has been developed as part of an NHS commission to provide a jargon-free and accessible model of CBT for use in busy clinical settings. It has been widely used by practitioners during its piloting, and the language used within the approach has been found to be acceptable to a wide range of health care practitioners and their patients (Reference Williams and WhitfieldWilliams & Whitfield, 2001). The model provides a clear structure to summarise the range of problems and difficulties in each of the following domains that a patient faces:

-

• life situation, relationships, practical problems and difficulties

-

• altered thinking

-

• altered feelings (also called moods or emotions)

-

• altered physical feelings/symptoms in the body

-

• altered behaviour or activity levels.

This assessment approach offers some clear benefits to both the patient and the practitioner and identifies clinical problems of relevance to them both, thus aiding engagement of both parties and providing a clear focus for treatment.

How the Five Areas model fits the concept of diagnosis

In the CBT approach, cognitive content and/or processes, emotional responses and behaviour are all seen as being important for assessment. The form of symptoms is still assessed, as this is needed for effective diagnosis. The CBT and diagnostic approaches can be combined, however, within a single assessment. Box 1 summarises how this process can be used in practice.

Box 1 ICD–10 (World Health Organization, 1992) assessment using the Five Areas model

Altered mood

Depressed mood

Loss of interest and enjoyment, with anhedonia present for more than 2 weeks

Altered thinking

Reduced self-esteem and self-confidence

Thoughts concerning guilt and unworthiness

Bleak and pessimistic views of the future

Ideas of self-harm

Altered physical symptoms

Diurnal variation of mood

Early morning wakening and disturbed sleep

Diminished/increased appetite/weight

Loss of libido, fatigue and reduced energy

Reduced attention and concentration

Constipation

Altered behaviour

Acts of deliberate self-harm or suicide

Reduced social activity/work/domestic activities

Assessment with a purpose: agreeing targets for change

Patients in psychiatry rarely have only one or two clinical problems. The Five Areas assessment model allows the range of problems and difficulties to be summarised within a single model. Whether from the viewpoint of the clinician or patient, when faced with a myriad of problems trying to deal with everything at once results in confusion and feelings of being overwhelmed. To tackle problems effectively, it is necessary initially to prioritise them and focus on changing just one area at a time. The clinician needs to discuss and jointly agree with the patient how to prioritise the problems. This necessitates putting some of the problems to one side for the time being and then, having jointly identified a key area, together drawing up a plan of how to tackle the problem. Change will be difficult without this degree of focus and structure.

Planning and selecting which areas to try to change first is a crucial part of successfully moving forwards. By choosing a single problem area to focus on initially, you and your patient are actively choosing not to focus on other areas. Setting targets will help you and your patient to focus on how to make the changes needed to get better. To do this you will need to identify the following:

-

• Short-term targets – changes that can be made today, tomorrow and next week. In practice, this often means changes to be made in time for the next out-patient clinic or clinical review.

-

• Medium-term targets – changes to be put into place over the next few weeks. This often means changes that are expected over the next few sessions.

-

• Long-term targets – where your patient wants to be in 6 months or a year. This might be the target to be achieved by discharge or, more often, a target that the patient continues to work towards some weeks or months after discharge.

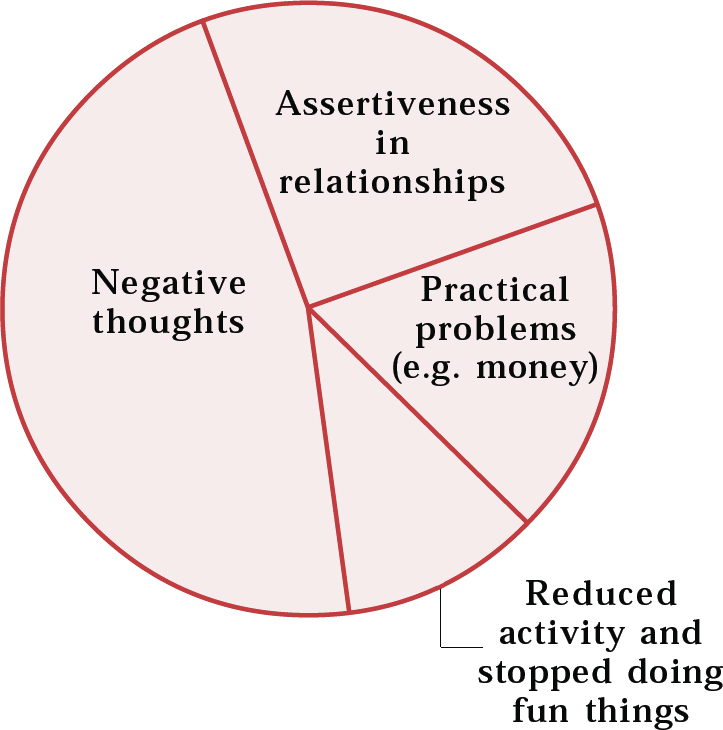

An important concept to communicate when agreeing targets for change is the idea of focusing on tackling only one or two questions to begin with. Part of the clinical assessment therefore involves working with the patient to negotiate and agree the sequence of problem areas to be tackled, starting with the first (short-term) problem, and then progressively moving into working on the medium- and longer-term problems. In the next section we use a pictorial approach – the pie chart (Fig. 1) – to help collaborative work with the patient on identifying these initial targets for change.

Fig. 1 Completed pie chart for selecting targets

Using a pie chart to agree targets for change

Most patients that psychiatrists see are currently facing a range of problems (Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams & Garland, 2002: p. 176). A common clinical difficulty is in trying to agree with the patient which area to try to change first. The following is a useful and collaborative approach that can aid this process and help to identify the short-, medium- and longer-term targets for change.

First, work together using the written Five Areas assessment summary. Draw each of the symptoms onto a pie chart. Each symptom should be allocated an area on the chart that summarises how much it is contributing currently to the total distress. If the term pie chart confuses the individual, other terms, such as slices of pizza, may be used.

Unless symptoms are initially combined in some way, the chart will often end up containing numerous small segments. This is unhelpful and can be very dispiriting for the patient. Instead it is better to try to combine symptoms into fewer, more general problem areas that can then be tackled in a systematic way. For example, five separate identified thoughts could be summarised as a general problem, such as extreme and unhelpful thinking (negative thoughts; see Fig. 1). The problem could then be summarised as a need to modify this type of thinking. Similarly, a problem such as lying in bed and not answering the phone could be summarised as a problem of reduced activity. Suicidal thoughts are important and should always be summarised on the chart, however they may be affected by other areas, such as excessive drinking, arguments and social isolation, each of which could also be identified as targets for change.

The summary terms used in completing this task are important. The contrast between poorly defined and well-defined problems is shown in Box 2.

Box 2 Poorly defined and well-defined problems

Poorly defined problems Well-defined problems

I feel terrible I have problems with recurrent negative thoughts that leave me feeling upset

Identify and then begin to modify specific examples of such thoughts

I have poor relationships I am unassertive and keep saying yes when I mean no

Teach assertiveness skills and how to apply them in relationships – at first with specific people and addressing specific topics

I have money worries I have problems with practical problem-solving

Teach practical problem-solving skills and apply them to the specific problems caused by the lack of money

I am doing nothing I have stopped doing things that I previously used to enjoy

Identify a specific vicious circle of reduced activity and help plan a step-by-step increase in a specific pleasurable activity to begin with

The role of the clinician is to try to summarise the problems into areas that provide clear targets for change. Typically these will revolve around:

-

• problem-solving

-

• assertiveness or dealing with relationships differently

-

• identifying and modifying extreme and unhelpful thoughts

-

• overcoming reduced activity or unhelpful behaviours such as drinking excessive amounts of alcohol

-

• overcoming physical problems such as pain or sleep difficulties

-

• using prescribed medications appropriately and effectively.

The whole approach promotes collaboration, active discussion and negotiation, with the aim of helping the patient to select targets for change. Once the general problem areas have been identified, more specific examples of these problems are focused upon.

Selecting targets

The next stage, having summarised the problems, is to identify the first target area to tackle – the short-term target(s). Short-term targets do not necessarily concur with the largest sector that has been identified. Factors to consider in the choice include the following.

Short-term targets must be realistic: change should be readily achievable over the next week or so. Choosing inappropriate and overly ambitious initial targets only leads to failure and demoralisation. Identifying targets that can be improved rapidly and successfully is important early on in treatment. There are many benefits of choosing a target area that has the greatest chance of success to begin with.

The patient has also to be actively involved in agreeing the choice or he or she is likely to be unmotivated, showing poor compliance or failing to return to the clinic.

Once the short-term goals have been identified, treatment focuses upon these over the next few sessions. This raises the question of how to integrate CBT approaches within the short time available in everyday busy clinical sessions.

How to structure sessions when there is not much time

In traditional CBT, a 1-hour (or often 50-minute) treatment session uses a very specific structure in order to maximise the effectiveness of the session by providing both a focus and structure for work. With a few modifications, the CBT session structure can be readily integrated into shorter clinical review sessions. To achieve this, clear choices need to be made regarding the focus and content of the session. In order to be realistic in terms of the time frame available, it is necessary to focus on only one, or at most two, area(s) in each session.

The similarities and differences of this approach when compared to the traditional CBT format are highlighted in Box 3. Our own clinical experience suggests that, for a practitioner to work effectively using this approach of a highly focused CBT intervention, the minimum time required is about 20 minutes. This is normally well within the time available for trainees, but it may require some rearrangement of the time allocated to the majority of consultant follow-up appointments. It is unlikely that most consultants can free up this amount of additional time immediately and across the board – for some colleagues this would mean an immediate doubling of the length of clinics. A more practical approach is, therefore, to create between two and four such slots within the usual out-patient clinics to begin with, allowing for non-attendance.

Box 3 Comparison of the structure of a session using traditional cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and the Five Areas everyday CBT approach

Traditional CBT session of 50–60 minutes Five Areas model (can be offered in 20-minute sessions)

Welcome Welcome

Brief update, mood/mental state examination, symptom review and medication check Brief update, mood/mental state examination, symptom review and medication check

Agenda setting: set the agenda for this session Prioritise agenda items if time is likely to be insufficient Agree an agenda (‘things we will choose to cover today’) for the session, with an explicit statement of the time limitation (e.g. we have 20 minutes today). Then prioritise problems and focus the session down to one, or at most two, area(s) only

Practice review Practice review

Discuss each agenda item in turn, with a summary of key points at the end of each item Discuss each agenda item in turn, with a summary of key points at the end of each item

Summary of the session, identify key things learned and what the patient plans to practice before the next session Summary of the session, identify key things learned and what the patient plans to practice before the next session

Feedback from the patient on how he/she found the session Feedback from the patient on how he/she found the session

This standardised session structure allows both clinician and patient to work in partnership and quickly get down to focusing on the therapeutic task at hand. The use of a session structure also provides a clear idea of what is and is not being achieved within the limited time available. Agenda items not addressed in one session are carried over to the next. This is not only reassuring for the patient, but also allows the clinician to prepare for the next session. The clinical records of the session are also structured with the same headings as the session, which makes record-keeping clearer, makes supervision easier and helps subsequent clinicians to see what treatment has already been given, the outcome and what needs to be done next.

Offering cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions

Cognitive–behavioural therapy offers a considerable additional armamentarium in the form of specific behavioural and cognitive interventions (Box 4). Many of these interventions stand alone and once taught can be used by patients to address their own problems. Only interventions that are relevant to the patients' current problem areas are offered.

Box 4 Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions in the language of the traditional and Five Areas models

Traditional CBT Five Areas assessment

Collaborative empiricism with guided discovery using Socratic questioning Aim to ask sequences of effective questions, and provide information that can help the person understand more about how he/she feels

Identify negative automatic thoughts and schemas using thought diaries Identify extreme and unhelpful thoughts using a thought investigation worksheet

Modify negative automatic thoughts, restructure core beliefs and schemas Use thought challenge worksheet to challenge extreme and unhelpful thoughts

Behavioural deficits – behavioural activation or pleasant event scheduling, graded task assignment, self-reward Identify the presence of the vicious circle of reduced activity

Graded exposure with or without response loop tapes, event rehearsal (for nightmares and post-traumatic stress disorder) and stress inoculation Plan a step-by-step increase in activity Identify the vicious circle of unhelpful behaviours. Face up to fears in a planned step-by-step way

Problem-solving Practical problem-solving using a seven-step plan (see Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001b )

Relaxation, re-breathing, stimulus control, visualisation, worry periods and mindfulness meditation Use any evidence-based, short relaxation treatment, e.g. anxiety control training (Reference SnaithSnaith, 1998)

Sleep hygiene Identify the vicious circle of insomnia. Make sensible changes to re-establish a normal sleep pattern

Homework task ‘Putting into practice what you have learned’

Compliance therapy Using medication effectively (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001a )

Relapse prevention Planning to stay well (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001a )

Some interventions are brief and can be taught in a single short session. Others may require instruction over an extended number of sessions. The use of structured CBT self-help materials can also be a very useful part of treatment (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001b ). Ten self-help workbooks have been developed that aim to allow patients to self-assess and self-manage focused treatment areas and use the Five Areas model (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 2001a ). This has a licence to allow photocopying of materials for use with patients and in teaching. These can supplement and reinforce what is covered in the sessions, and are used by the patient at home. Other self-help manuals are also available (e.g. Reference BurnsBurns, 1990; Reference Greenberger and PadeskyGreenberger & Padesky, 1995) and clinicians need to familiarise themselves with any materials used before recommending them to patients.

The style of treatment in cognitive–behavioural therapy

The emphasis that CBT places on asking questions can be difficult, particularly when we are more familiar with the traditional diagnostic interview, or find that we are overly prone to tell the patients our answers to their problems. Although a didactic approach is required when providing information about a disorder or treatment, a collaborative style offers many benefits for patient and clinician. It results in greater adherence to the final treatment plan and is more in line with the expectations that many patients have of their doctors.

Measuring outcomes

In CBT, questionnaires are often routinely used with patients to assess the severity of their disorder and to monitor the outcome of treatment. Not all are expensive: some, such as the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE; Reference Evans, Margison and BarkhamEvans et al, 1998), are in the public domain and others are available at a flat fee that includes photocopying rights. An example of the latter are the NFER-Nelson assessment packs (available from http://www.nfer-nelson.co.uk/html/edu/index.htm). Such questionnaires offer considerable advantages by standardising assessment and reducing inter-observer variability associated with changing clinicians. In addition, self-rated scales can be completed by the patient while in the waiting room, thus saving valuable clinic time and providing objective evidence of clinical outcomes that could readily be used in service audit and clinical governance review. In addition, diaries and worksheets are central to the CBT approach, and their use is summarised in the next two articles of this series.

Problems with implementing cognitive–behavioural therapy in everyday clinical practice

New referrals to the psychiatric out-patient clinic have varied expectations, but can be educated about the treatment process and the interventions that might be delivered. Patients who have already attended the clinic for months or years are a very different group. The introduction of focused psychological techniques such as the Five Areas CBT approach raises the expectation of change in both patient and clinician. The possibility of change may be perceived as threatening and intrusive on an otherwise stable state resulting in fears of failure and shame. Such patients may be more resistant to new psychological interventions and for these reasons gradual, slow, consistent change over many months is likely to yield better results.

Working with patients with personality disorder

The CBT assessment model offers a number of advantages in work with patients with personality disorder. First, it provides a readily applicable understanding of the internal world of such patients, making therapeutic breakdown easier to predict and pre-empt. Second, specific interventions can help address the presenting problem, so reducing any sense of helplessness in both patient and clinician.

Often patients with personality disorder have numerous concurrent problems – many of which are long-term. It may well not be possible to improve more than one or two of these areas. The need for realistic goals is paramount, and the Five Areas model helps to identify such goals. For example, in the short-term focusing on over-coming problems of reduced activity, or reducing unhelpful behaviours in a planned, step-by-step way may lead to significant improvements. In the medium- to longer-term, teaching more effective skills of problem-solving, more appropriate assertiveness skills or addressing issues such as poor compliance with medication can lead to significant benefits. Although such focused interventions do not improve every problem faced by the individual, because of the reciprocal links between each of the five areas, significant improvements in mood and in interpersonal functioning may still be attainable from some relatively unambitious interventions. As the patient experiences benefit from the psychological intervention, this may enhance his or her motivation to pursue treatment. Finally, an empathic and collaborative working style is less likely to inflame the situation and may help the patient begin to engage more in treatment.

Building one session on another

Cognitive–behavioural therapy views the clinical sessions with the patient as only a part of the overall treatment. The individual sessions provide a structure and focus to treatment, with the planned provision of information and the learning of self-management skills within the context of a collaborative therapeutic relationship with the clinician. A crucial part of CBT is a self-help approach that enables the patient to put into practice in everyday life what he or she has learned during treatment sessions. Equipping the patient with a set of skills to self-manage current problems is a central aim of CBT. For this reason a key component of each treatment session is to work with the patient in developing a specific action plan of how, between now and the next scheduled meeting, he or she is going to put into practice what was learned in the session. The term ‘putting into practice what you have learned’ is preferred to the traditional CBT term ‘homework’ as it avoids the potential negative associations of treatment being akin to school work that must be completed and is then marked by a teacher, or in this case the clinician. ‘Practice’ is negotiated collaboratively between patient and clinician and is seen as a time for active self-treatment. The inter-session practice encourages the patient to generalise skills learned in sessions to tackle problems encountered in everyday life. It is important that difficulty with this process is not viewed as a failure but simply as an opportunity for further learning. Success, on the other hand, can reinforce the patient's sense of self-efficacy and give encouragement that future difficulties or relapses may be tackled in a similar manner. As a result, treatment outcome is enhanced for patients who complete such ‘homework’ assignments.

In addition to setting clear practice goals, it is useful to build in a practice review time at the beginning of each scheduled treatment session. This allows patient and clinician to review how well the inter-session practice has gone, identify any problems encountered in its completion and use the results of the practice as a basis for future work, both in and out of sessions. Structuring the session in this way will also highlight to the patient the importance of inter-session practice, which in turn should increase the likelihood that the practice tasks will be carried out. This ongoing process of reflecting on individual learning derived from the inter-session task is a key component of the CBT approach. Ideally such tasks should present the patient with a no-lose situation. Thus, even if the task does not go as intended, or indeed if it is not completed at all, patient and clinician can still both learn more about the patient's problems. Even if the inter-session task yields an extremely beneficial result it is still vital to review the outcome of the task, identify the specific learning that has taken place and take every available opportunity to generalise this to other situations in the patient's life. This review process can be summarised by four simple questions:

-

• What went well?

-

• What did not go so well?

-

• What have you learned as a result?

-

• How can you put into practice what you have learned from this task?

Multiple choice questions

-

1. In the Five Areas assessment model, when choosing targets for intervention:

-

a the largest problem should always be tackled first

-

b every problem identified in the assessment should be placed individually on the pie chart

-

c the target problem should be decided by the health care practitioner alone

-

d the short-term targets should be realistic and achievable

-

e general problem areas such as the presence of extreme and unhelpful thoughts should be identified.

-

-

2. Continued work on problems between sessions is:

-

a best called homework

-

b best ‘set’ by the practitioner

-

c enhanced by introducing a practice review at the start of the next session

-

d associated with improved outcomes

-

e not as important as the one-to-one session with the practitioner.

-

-

3. Key questions that can be used in the practice review include:

-

a how do you feel?

-

b what didn't go so well?

-

c what have you learned as a result of what happened?

-

d what went well?

-

e how have things been?

-

-

4. Problems encountered when offering CBT treatments in everyday practice include:

-

a practitioners with training often move jobs, away from the clinical team

-

b the traditional language of CBT is complex and makes little immediate sense without specialist training

-

c most patients are unwilling to work in this way

-

d difficulties adapting the approach for use with patients with personality disorder

-

e the incompatibility of the approach with the use of medication and diagnostic summaries.

-

-

5. Elements of a Five Areas treatment session include:

-

a active discussion between the practitioner and patient

-

b a major focus on past developmental issues

-

c a formal mental state examination

-

d significant silences where the patient reflects on his or her upbringing

-

e a medication review.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | T | a | T |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | F | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | F | d | F |

| e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.