1 Introduction

In this article I reflect on interpretations of sociolinguistic style, focusing on an under-described pattern of intraspeaker variation. Specifically, I investigate an inverted style pattern (see Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith2014: 254; Sandow Reference Sandow2020), that is, where speakers’ usage of non-standard forms increases as their attention-to-speech becomes greater. I illustrate this pattern and, using the Bourdieusian notions of capital and linguistic markets (e.g. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1991), consider the social psychological motivations for inverted style-shifting in the context of lexical variation in Cornwall, United Kingdom. Using speakers’ metalinguistic commentaries, I account for inverted style-shifting from the perspective of place identity, social meaning and language ideology. Additionally, this article contributes to the relatively limited but growing body of spoken lexis-oriented sociolinguistic studies (e.g. Beeching Reference Beeching, Pooley and Lodge2011; Beal & Burbano-Elizondo Reference Beal and Burbano-Elizondo2012; Robinson Reference Robinson2012; Tagliamonte & Brooke Reference Tagliamonte and Brooke2014; Sandow & Robinson Reference Sandow, Robinson, Braber and Jansen2018; Sandow Reference Sandow2020; Tagliamonte & Pabst Reference Tagliamonte and Pabst2020).

As well as internal linguistic constraints (see Labov Reference Labov1994), the trajectory of linguistic variation and change is well attested to be mediated by stylistic and social factors (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1972a; Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974). Stylistic, or intraspeaker, variation emerges in different speech environments in response to contextual, linguistic and social stimuli. One of the contextual factors which has been observed to condition language use is attention. Labov's (Reference Labov1972a, Reference Labov1972b) ‘attention-to-speech’ model is underpinned by the principle of style-shifting and the principle of attention.

-

The principle of style-shifting: ‘there are no single style speakers’ (Labov Reference Labov1972b:112).

-

The principle of attention: ‘[s]tyles can be ordered along a single dimension, measured by the amount of attention paid to speech’ (Labov Reference Labov1972b: 112).

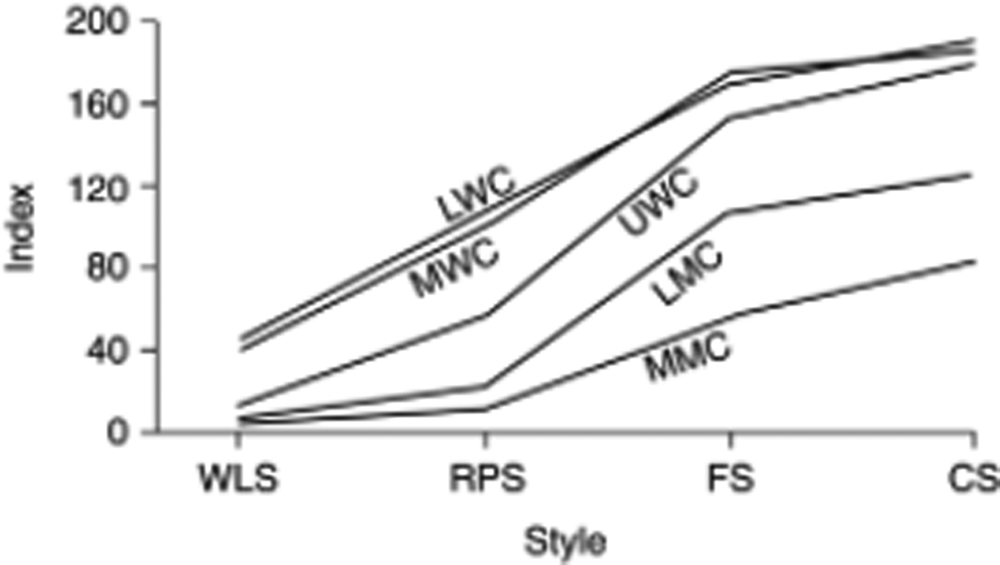

Early sociolinguistic studies reported on a consistent pattern of style-shifting. Indeed, in his study on the Lower East Side of New York, Labov (Reference Labov2001a: 38) reported that ‘each individual followed the same community-wide pattern of style-shifting’. Speakers of all socioeconomic groups typically converge on the speech of the higher socioeconomic groups when their attention-to-speech is elevated (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1990: 223–4; Snell Reference Snell2018: 667). This monotonic relationship between speech style, socioeconomic class and use of a sociolinguistic variant can also be observed in figure 1, with higher values on the y-axis representing greater usage of non-standard variants of (t).

Figure 1. Social and stylistic variation of (t) in Norwich in word-list style, reading passage style, formal speech and casual speech among lower-working-class, middle-working-class, upper-working-class, lower-middle-class and middle-middle-class speakers (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974: 96)

Figure 1 demonstrates a widely attested pattern of style-shifting, whereby, as their attention-to-speech increases, speakers shift towards a greater usage of standard variants, and, therefore, reduce their usage of non-standard variants. Some groups of speakers exhibit greater stylistic variation than others. For example, in his Harlem study, Labov (Reference Labov1972c) found that for the (r) variable, isolated individuals, so-called ‘Lames’, who had limited engagement in vernacular culture, exhibited greater stylistic variation than those who had greater engagement in vernacular culture, such as those aligned with the peer groups the ‘Thunderbirds’ or ‘Aces’ (see also Labov et al. Reference Labov, Cohen, Robins and Lewis1968: 170). However, it is not only the extent to which individuals or groups of individuals participate in style-shifting that has been shown to vary, but also the direction of this shift.

1.1 Inverted style patterns

Another attested pattern of intraspeaker variation, whereby non-standard forms increase as attention-to-speech is elevated, has been referred to as an ‘inverted’ style pattern (Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith2014: 254; Sandow Reference Sandow2020). Inverted style-shifting has been observed in diverse localities, including Appalachia (Reed Reference Reed2016), Belfast (Milroy Reference Milroy1987), Glasgow (Stuart-Smith et al. Reference Stuart-Smith, Timmins and Tweedie2007; Stuart-Smith & Ota Reference Stuart-Smith, Ota and Androutsopoulos2014) and Israel (Gafter Reference Gafter2016), as well as among British Indian adolescents in London (Hundt & Staicov Reference Hundt and Staicov2018).

It has been reported that speakers use careful speech styles as an opportunity to perform identities (e.g. Schilling-Estes Reference Schilling-Estes1998; Sandow & Robinson Reference Sandow, Robinson, Braber and Jansen2018). This pattern is evidenced by Milroy's (Reference Milroy1987: 101) observation that in her Belfast data, for the (a) variable ‘word list (a) scores are usually closer to the vernacular than interview style (a) scores’. Likewise, Gafter (Reference Gafter2016) found a higher frequency of (stigmatised) pharyngeal variants in the word-list task than in conversational speech. Gafter (Reference Gafter2016) interprets this style pattern as a performance of ethnic identity. Similarly, Stuart-Smith & Ota (Reference Stuart-Smith, Ota and Androutsopoulos2014) found that while many older and middle-class Glaswegians conformed to the typical style pattern of using fewer non-standard forms in careful speech, many working-class adolescents did not. Specifically, Glaswegian working-class adolescents used more non-standard variants in word lists than in conversational speech. Stuart-Smith & Ota (Reference Stuart-Smith, Ota and Androutsopoulos2014: 158) interpret this style pattern as a performance of localness and to be indicative of ‘a particular stance to the task, and to the fieldworker’, clearly distinguishing the speaker from the fieldworker who was perceived as ‘posh’ (Stuart-Smith & Ota Reference Stuart-Smith, Ota and Androutsopoulos2014: 163).

Even Labov's seminal (Reference Labov1972a) data reveal a slightly inverted pattern for some speakers, including Abraham G. ((oh) variable, Labov Reference Labov1972a: 102) and Steve K. ((eh) variable, Labov Reference Labov1972a: 104). Additionally, Labov (Reference Labov, Eckert and Rickford2001b: 101) found 17 per cent of participants under the age of 30 (and 6 per cent of those over 30) ‘reversed’ the community-wide pattern of style-shifting towards standard forms of (DH) in careful styles. That is, they used a higher frequency of non-standard forms in careful styles. Similarly, Cheshire (Reference Cheshire and Romaine1982) found that ‘Barney’, an adolescent with a particular hostility towards his school, used a higher rate of non-standard present tense verb forms in the ‘school’ style as opposed to the ‘vernacular’ style.

Inverted style patterns have also been observed in Cornwall. A pattern of inverted style-shifting was observed in West Cornwall by Dann (Reference Dann2019) for the bath vowel, with local realisations being more likely to occur in word lists as opposed to conversational speech. Similarly, based on data collected from a pilot study of 21 Cornish males, Sandow & Robinson (Reference Sandow, Robinson, Braber and Jansen2018) and Sandow (Reference Sandow2020) report on the finding that local dialect forms crib and croust (≈‘snack/lunch’) were more likely to occur in careful as opposed to casual speech styles.

1.2 Social meaning

Other studies of sociolinguistic style (e.g. Coupland Reference Coupland1985; Eckert Reference Eckert1989; Johnstone Reference Johnstone and Englebretson2007; Moore & Podesva Reference Moore and Podesva2009; Soukup Reference Soukup2013; Drummond Reference Drummond2018; Snell Reference Snell2018) have moved away from elicitation tasks and attention-based models of intraspeaker variation to consider style as a resource with which speakers can construct identities and stances in interactions. Such research has demonstrated that in addition to the referential function of language, linguistic usage also communicates social meaning. From the perspective of social meaning, linguistic features ‘index’ particular social identities and stances. Social indices can include membership of social groups, such as the working class, traits associated with those groups, such as toughness, as well as interactional stances, such as friendliness. In light of the social meanings attributed to sociolinguistic variants, speakers can manipulate their sociolinguistic repertoires and a range of other socio-semiotic resources in order to align themselves with or in opposition to other individuals, groups of individuals, or social structures (see Eckert Reference Eckert2000).

Standard variants are widely attested to index character traits believed to be statusful, including educatedness and articulateness as well as stances such as ‘polite’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008a). Typically, standard forms of language assert status, while non-standard forms lack status (see Snell Reference Snell2018). Snell (Reference Snell2018) argues that while standard forms index status, local forms often index solidarity (see also ‘overt’ and ‘covert’ prestige, e.g. Trudgill (Reference Trudgill1972)). However, it is not the case that there is a simple singular mapping between a linguistic form and social meaning. Moore & Podesva (Reference Moore and Podesva2009) highlight the ways in which tag-questions can communicate different social meanings to different groups. For example, while non-standard regional dialects typically lack status, there are interactional contexts in which the very same variety can assert status (see Snell Reference Snell2018). This demonstrates the dynamic nature of social meaning and the ways in which the interaction between the speaker and hearer can activate any number of social meanings associated with a particular sociolinguistic variant (see Eckert Reference Eckert2008a).

In light of the social meaning of sociolinguistic variants, speakers can use their sociolinguistic repertoire as a resource to construct identities. Managing and negotiating these potential social meanings is a feature of the competence of speakers as social actors. In order to make oneself socially locatable, a speaker can use their stylistic repertoire to index perceived desirable social characteristics about themself (Sharma Reference Sharma2018). According to Eckert & Labov (Reference Eckert and Labov2017: 467), style-shifting is ‘an indirect indication of social meaning’. However, seldom have sociolinguists considered attention-based style-shifting from the perspective of social meaning.

2 Style in Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis

Historically, as well as today, Cornish people have a very strong sense of local identity, including a pride in the local dialect, Anglo-Cornish, despite widespread stigma attached to this variety (Beal Reference Beal2006, Reference Beal, Montini and Ranzato2021; Montgomery Reference Montgomery2007; Dann Reference Dann2019).Footnote 2 This identity has evolved over the centuries and is largely contingent on Cornwall's peripheral status in relation to England (see Payton Reference Payton1992). Many Cornish people reject the notion that Cornwall is a county of England and assert that Cornwall is a Celtic nation (see Deacon et al. Reference Deacon, Cole and Tregidga2003). In doing so, they position themselves in opposition to England and the English. This opposition is manifested at many levels of everyday life and social structure, including eating habits, a de facto national anthem, and iconography, as well as language. At the same time, many other Cornish people view Cornwall as a county of England and are keen to distance themselves from those who assert nationhood. A key question that this study serves to answer is, is the rejection of Englishness and the strong orientation to Cornwall reflected at the level of lexical usage?

The ideological landscape in Cornwall makes it an interesting test-site to conduct variationist sociolinguistic analysis. The primary focus of this study is the stylistic variation in the usage of Anglo-Cornish words by 80 speakers from the Cornish towns of Camborne and Redruth. Anglo-Cornish is the variety of English spoken in Cornwall and is distinct from Kernewek, the Cornish language. In addition to considering the intraspeaker distribution of Anglo-Cornish words, participants’ metalinguistic observations provide further insight. The metalinguistic commentaries are mostly concerned with reported usage patterns and the participants’ perception of the social meaning of the investigated lexical items.

2.1 Lexis-oriented elicitation procedures

I explore the usage of four lexical variables, which can be realised by five Anglo-Cornish lexical variants.Footnote 3 The variables are lunch box, woman, walk and tourist, which can be realised by the Anglo-Cornish variants crib [box]/croust [box/tin], maid, stank and emmet. Eighty participants, who were all ethnically white British, self-identified as Cornish and who lived and/or worked in the Cornish towns of Camborne or Redruth, completed lexical elicitation procedures, engaged in metalinguistic discussions and provided narratives regarding Cornwall and Cornish identity. It is important to note that I, the interviewer, am Cornish so could be viewed as a member of a Cornish in-group. However, this in-group membership is tempered by the fact that I speak with an accent and dialect that is typically characterised as Standard Southern British English (for discussion of my positionality, see Sandow Reference Sandow2021).

In this article I discuss usage data collected from two lexical elicitation tasks which contrast in the attentional load that they demand from participants. Firstly, relatively casual speech was elicited through spot-the-difference tasks (cf. Diapix tasks (Van Engen et al. Reference Van Engen, Baese-Berk, Baker, Choi, Kim and Bradlow2010; Baker & Hazan Reference Baker and Hazan2011)).Footnote 4 Participants were asked to identify six differences from each of five spot-the-difference tasks, totalling 30 differences. These tasks represent scenes which can be described as ‘living-room’ (see figure 2), ‘street’, ‘beach’, ‘bathroom’ and ‘table’. In order to complete the task, participants needed to lexicalise the concepts that are of interest to this study, by ‘spotting the difference’, for example, ‘the lunch box/crib box is facing a different direction’. As well as a number of distractor differences, each of the investigated variables occurred in two scenes, for example, the concept lunch box occurred in the ‘living-room’ and ‘table’ scenes.

Figure 2. The ‘living-room’ spot-the-difference scene

The tasks are designed so that the participant's primary cognitive load is concerned with problem-solving. In order to increase their attention to the task, and not speech, I used a watch to record the time each participant took to complete the tasks. It was thought that by doing the tasks ‘against the clock’ their speech would be less monitored, and, consequently, more casual.

In contrast to the relatively casual speech style elicited from the spot-the-difference tasks, a relatively careful speech style was elicited through ‘naming tasks’. In this task, participants saw an image and an incomplete sentence. They were asked to use the image to complete the sentence (see figure 3). Participants were told that in this task, the interviewer was ‘interested in the words that you use’. This was done in order to maximise the attentional load paid to speech in this task by diverting the primary cognitive processing load onto language, particularly lexical usage. This serves to distinguish the primary focus of participants’ cognitive load, from problem-solving in the spot-the-difference task, to lexical usage in the naming task.

Figure 3. The naming task for lunch box

The trigger stimulus for each investigated variable, such as the representation of a lunch box, that all participants saw was identical between the two tasks. Thus, the observed variation was not referential but social or stylistic. After the elicitation tasks, participants engaged in metalinguistic discussions with the interviewer and provided narratives pertaining to Cornwall and Cornish identity.

2.2 Usage data

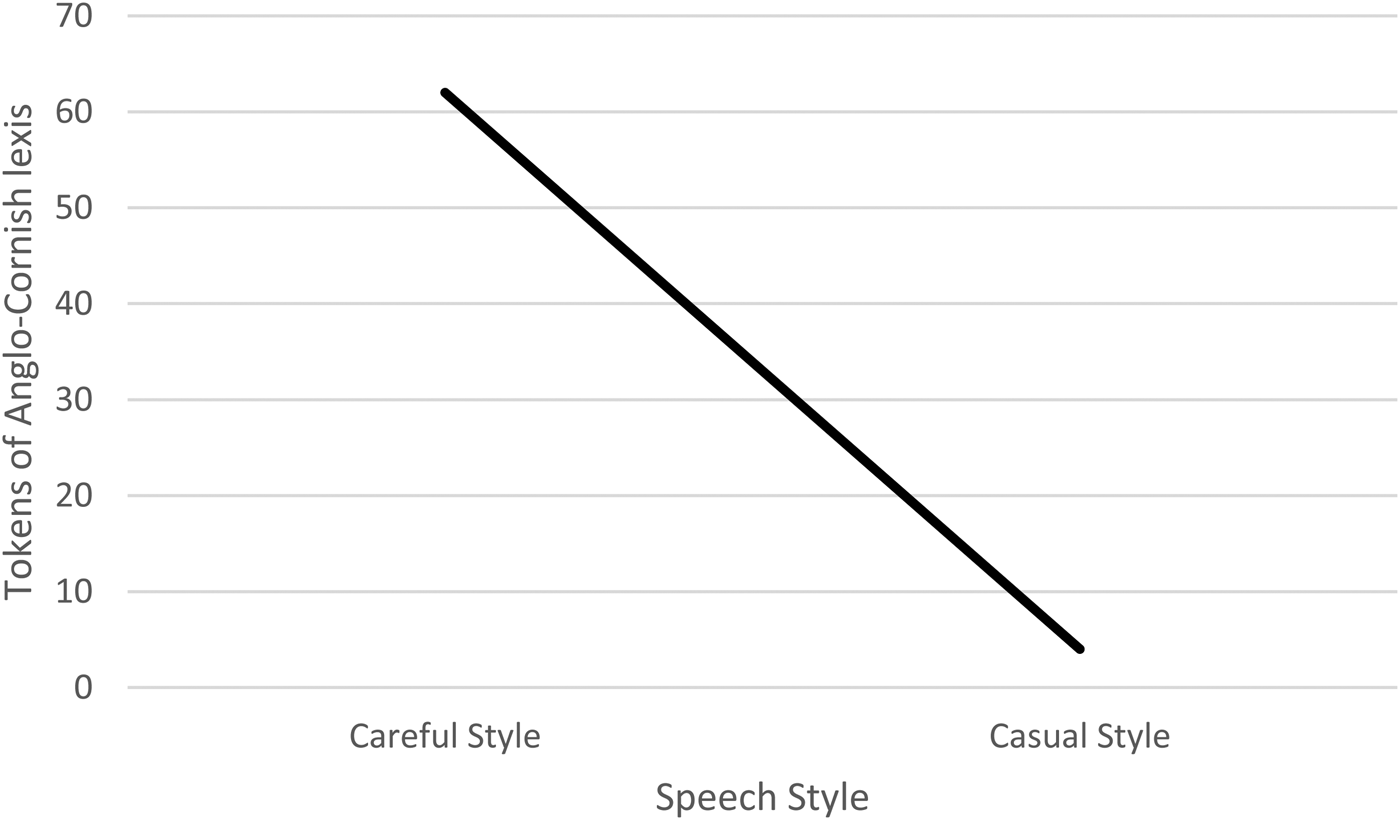

Overall, participants used 67 tokens of Anglo-Cornish variants, 62 of which occur in careful speech styles. Of the four lexical variables investigated in this study, the average number of Anglo-Cornish variants used in the casual speech style per speaker is 0.062, while in the careful speech style, participants used an average of 0.775 Anglo-Cornish variants.Footnote 5 For the purposes of the quantitative analysis in this article, I make the distinction only between Anglo-Cornish variants and non-Anglo-Cornish variants.Footnote 6 Each investigated Anglo-Cornish variant exhibits the same direction of intraspeaker variation. The stylistic distribution of Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis can be seen in figure 4.Footnote 7

Figure 4. The usage of Anglo-Cornish variants in careful and casual speech styles

Figure 4 shows that Anglo-Cornish lexis was much more likely to be found in careful, as opposed to casual, speech styles (2-tailed Fisher's exact test, p = <.001). This is an example of an inverted style pattern.

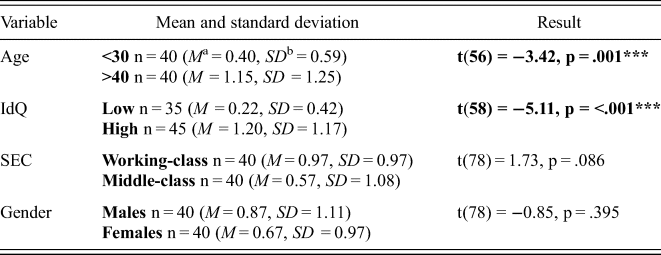

While I do not go into detail with regard to social variation in this article (for more detail, see Sandow Reference Sandow2021), it is important to note that strength of local identity, as determined by an identity questionnaire (IdQ) (adapted from Llamas Reference Llamas1999; Burbano-Elizondo Reference Burbano-Elizondo2008), is the best overall predictor of Anglo-Cornish lexical usage (see table 1). The IdQ contained ten statements, such as ‘I would not want to be from anywhere else’, and asked participants to rate the extent to which they agreed with these statements from 1, indicating strong disagreement, to 5, indicating strong agreement. If participants, on average, ‘agreed’ with each statement their aggregate IdQ total would be 40. Thus, a score of 40 or above was used to distinguish those with a ‘high’ IdQ total from those with a ‘low’ IdQ total (a total of 39 or below), with ‘high’ and ‘low’ totals indicating strong and less strong feelings of Cornish identity, respectively.

Table 1. Independent sample t-tests of the relationship between Anglo-Cornish lexical usage and age, identity questionnaire (IdQ) score, socioeconomic class (SEC) and gender. Each of the independent variables is conceptualised as binary

a M = Mean (average).

b SD = Standard Deviation.

Speakers with a strong local orientation, as determined by a ‘high’ identity questionnaire score, are more likely to use the local dialect forms than those with a weaker sense of Cornish identity.Footnote 8 Age also exhibits a strong effect, with those aged over 40 being most likely to use the Anglo-Cornish variants. There is no overall difference between the usage of Anglo-Cornish words by middle-class and working-class speakers, although working-class speakers are more likely to use crib/croust and emmet than their middle-class counterparts (2-tailed Fisher's exact tests, p = .010 and p = .039, respectively). Overall, gender does not exhibit a statistically significant association with the usage of Anglo-Cornish lexis, nor does it exhibit a statistically significant relationship with any of the individual investigated variables.

2.3 Metalinguistic commentaries

The usage data, as displayed in figure 4 and table 1, are consistent with participants’ metalinguistic observations. While participants also provided a great deal of metalinguistic detail relating to interspeaker variation (see Sandow Reference Sandow2021), in this section I focus on comments pertaining to intraspeaker variation and stylisation of local identities through the Anglo-Cornish dialect. Participants consistently report that the Anglo-Cornish dialect, particularly its lexis, can be used to construct a Cornish identity and that this is done agentively. This is consistent with the shift towards Anglo-Cornish forms in the careful speech style.

The link between local identity performance and the Anglo-Cornish dialect is widely attested by informants in this study. For example, Tamara (all names used in this article are pseudonyms) states that ‘most [Anglo-Cornish dialect words] are working-class words but are also used as a marker when you want to assert your Cornishness’. Indeed, Tim explains that ‘[the Anglo-Cornish dialect] is reflective of a Cornish identity. It is an identity statement.’ Similarly, Toby says that ‘people use [emmet] to advertise their Cornishness’, while Sally states that ‘[using maid] accentuates your Cornishness’. These quotes demonstrate that the value of the Anglo-Cornish dialect is not covert but overt and the subject of explicit metalinguistic commentary.

This stylisation of Cornish identities was observed to be a response to lexical attrition. For example, Derek observes that ‘[the Anglo-Cornish dialect] now seems not quite authentic, lots of [Anglo-Cornish] dialect words are becoming less authentic as they're becoming a badge of a Cornishman’. Derek then comments that he uses Anglo-Cornish dialect forms ‘to assert my own pride in being Cornish and my sadness that the dialect is dying out’. He also states that croust was ‘very common in [his] childhood. Now it is more likely to be used in a half-mocking way by the educated middle-class Cornish to prove that they are Cornish.’ Similarly, Tina states that ‘[emmet] is something that is being used more and more as a flag of Cornishness’. These metalinguistic commentaries suggest that Cornish people stylise a ‘local’ identity and index their Cornish provenance through the use of Anglo-Cornish words. Thus, while Anglo-Cornish variants are not attested as typical of casual speech, they are reported as being used purposefully to communicate a speaker's Cornish provenance.

The participants’ metalinguistic observations suggest that the inverted style pattern shown in figure 4 is consistent with many participants’ lived experiences of Anglo-Cornish dialect usage in their local community. In the following section, I consider social psychological and cultural explanations for this inverted style pattern in Cornwall.

3 Style in context

I consider the use of Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis in careful, as opposed to casual, speech styles from the perspective of Bourdieu's (Reference Bourdieu1977, Reference Bourdieu1991) concepts of capital and the linguistic marketplace. Under this interpretation, language practices are commodified on a market, the ‘linguistic market’, where they are assigned value as part of a broader model of symbolic capital. Typically, in the linguistic marketplace the standard variety is perceived to be ‘legitimate’ as it is validated by its association with legal, ecclesiastical and political institutions (see Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1991). According to Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1991: 67), ‘[u]tterances receive their value (and their sense) only in their relation to a market, characterized by a particular law of price formation’. The legitimate language is afforded greater prestige, and, therefore, more capital, than overtly stigmatised regional varieties, such as Anglo-Cornish.

Bourdieu (e.g. Reference Bourdieu1991) argues that there is no counter-legitimate language. For example, Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1991: 45) states that the ‘official language’ or simply the ‘language is the one which, within the territorial limits of that unit, imposes itself on the whole population as the only legitimate language’. Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1993: 82) argues that the linguistic marketplace is ‘relatively unified’. That is, there is a broad consensus on the value of linguistic forms on the linguistic market. For example, Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1991: 45) states that ‘to impose itself as the only legitimate one, the linguistic market has to be unified and the different dialects (of class, region or ethnic group) have to be measured practically against the legitimate language’. This suggests a hierarchical structure, with the standard, conceived of as the ‘legitimate’ language, occupying the topmost point of the hierarchy. Bourdieu's notion ‘of the linguistic market is a monolithic market at the national level’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008b: 32; see also Park & Wee Reference Park and Wee2012). Thus, while there may be different markets which assign symbolic values to language in, for example, England and the USA, each nation is thought to have a relatively unified linguistic market.

Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1991: 71) predicts greater use of the ‘legitimate’ language in formal speech. This is consistent with the finding in variationist sociolinguistics (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1972a; Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974) that standard forms of language are most likely to be used in formal, or careful, speech. Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1993: 85) accounts for the use of non-standard, that is, non-legitimate, language by noting that ‘plain speaking exists but as an island set apart from the laws of the market’. Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1993: 84–5) gives an example of people talking in a village bar as a context in which the market is less dominant (see also Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1991: 71).

The intraspeaker variation exhibited in this study challenges Bourdieu's account of the linguistic market. Bourdieu's notion of a unified market does not account for why Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis is used most frequently in careful speech styles. I suggest that the shift towards the local forms indicates that the Anglo-Cornish dialect has locally meaningful value. Similarly, Labov (Reference Labov2001a: 105) recognises that ‘nonstandard forms represent an alternate form of symbolic capital that carries full value in working class social networks, and serves the needs of members of that society’. This raises the question as to where this value comes from.

A deregulated market, such as in Bourdieu's (Reference Bourdieu1993: 84) village bar example, would not engender a structured marketplace. Without structure and a shared understanding of the value of linguistic forms, the direction of style-shifting would be random. Yet, in Cornwall, this pattern of style-shifting is not random. Out of 67 uses of Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis 62 occurred in careful speech styles and all speakers who exhibited style-shifting did so in the same direction. The shift towards Anglo-Cornish forms in careful speech suggests that there is a widespread, though not ubiquitous, understanding of the value of local forms. The inverted style pattern suggests not just an absence of negative value, but positive value conferred on the Anglo-Cornish dialect. By using Anglo-Cornish lexis in careful styles, speakers indicate a rejection of the standard language market and the limited value it assigns to the Anglo-Cornish dialect. Thus, it is not the case that the speakers who exhibit the inverted pattern of style-shifting align with the standard language market, nor is it the case that this pattern of intraspeaker variation is a consequence of a weakening of standard language market forces. Therefore, there must be an alternative market force assigning value with (largely) autonomous laws of price formation.

I suggest that more than one linguistic market exists in Cornwall. This is evidenced by the mixture of negative and positive affect towards the Anglo-Cornish dialect in the metalinguistic evaluations from many of the participants in this study. I propose that, in Cornwall, the standard language market competes alongside a Cornish ‘micro-market’ (for a discussion of a ‘micro-market’, see Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1993: 80), validated by a distinctly Cornish habitus (see Kennedy Reference Kennedy2016). I suggest that this is a local manifestation of a broader ‘vernacular’ or ‘alternative’ market (see Woolard Reference Woolard1985; Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1992; Roseman Reference Roseman1995; Eckert Reference Eckert2000; Moore Reference Moore2002; Filimonova Reference Filimonova2020). This is consistent with Park & Wee (Reference Park and Wee2012), who acknowledge the presence of smaller, more geographically confined, and autonomous markets.Footnote 9

The standard language market and the Cornish micro-market endow different values to Standard English and Anglo-Cornish forms. They have different rates of capital conversion (Park & Wee Reference Park and Wee2012). That is, the relative value of the standard and Anglo-Cornish varieties varies between the two markets. The Cornish micro-market sets its own value autonomously, even in contrariety to the standard language market. Anglo-Cornish forms lack status on the standard language market but those same forms can assert status on the Cornish micro-market (cf. Snell Reference Snell2018). While on the standard language market, using Anglo-Cornish forms depreciates one's cultural capital, on the Cornish micro-market, the use of Anglo-Cornish variants enhances one's cultural capital. That is, the Anglo-Cornish dialect is a liability on the standard language market, whereas it is an asset on the Cornish micro-market. This is evidenced by the shift towards Anglo-Cornish forms in careful speech styles. The range of values attributed to the standard and to local dialect forms highlight the fact that Cornwall is not a classic ‘speech community’ which is characterised by a shared evaluation of linguistic norms (Labov Reference Labov1972a).

Alignment with the competing linguistic markets in Cornwall can be considered in light of Cornish identity. Those who align themselves with the local micro-market position Cornwall at the centre of an alternative structural paradigm, in opposition to the conventional market, which assigns the greatest degree of capital to the cultural and linguistic output associated most with London and the Southeast. However, this does not explain why, if the Anglo-Cornish dialect is so valuable in the Cornish micro-market, Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis was not more commonplace, particularly in casual speech styles. If the Anglo-Cornish dialect, and the indexed ‘Cornish’ identity, is aspirational for many speakers, why don't they use the Anglo-Cornish dialect all of the time? I suggest one primary reason for this.

In the face of perceived pressure to assimilate to Anglo cultural norms, I suggest that the use of Anglo-Cornish lexis mainly in careful speech styles is indicative of a ‘minority-group reaction’ (see Edwards Reference Edwards and Bassiouney2017). Edwards (Reference Edwards and Bassiouney2017: 25) suggests that this reaction can occur when ‘the codes, postures and practices of the dominant become accepted and normative among the less dominant, even where such acceptance may be grudging’. From a sociolinguistic perspective, the minority group (the Cornish) are aware of the widely acknowledged stigma of their local dialect and conform to the normatively prescribed linguistic and other social practices, yet reject these very same practices when they feel that they are able to, including, but not limited to, a sociolinguistic interview with a Cornish fieldworker.

In light of the anticipated negative reactions that Anglo-Cornish lexical forms may incur, participants may habitually conform to the standard language market. Yet, in the interview, where the Anglo-Cornish dialect was felt to be legitimised, participants identified an opportunity to present themselves as Cornish. In this context, the value of a Cornish identity is validated by the Cornish micro-market. This construal of an ostensibly authentic or ‘real’ self in careful speech styles can be accounted for by an attention-to-self model of style.

3.1 Attention-to-self

While I attribute the locally meaningful prestige of Anglo-Cornish dialect lexis to the presence of a Cornish micro-market, that is, a local system of (symbolic) price formation, the use of the local forms in careful speech styles warrants further exploration. Labov's (Reference Labov1972a) attention-to-speech model accounts for a widely observed (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1966; Trudgill Reference Trudgill1974; Modaressi-Tehrani Reference Modaressi-Tehrani1978; Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith1999; Schleef Reference Schleef2021) shift towards an idealised, typically standard, way of speaking in careful speech styles. Eckert (Reference Eckert2000: 18) describes the standard language as ‘stylistic target’ in survey studies of variation (see also Labov Reference Labov1990: 223–4). In Labov's (Reference Labov1966) New York study, for most speakers, an idealised way of speaking resembled that of the overtly prescribed standard, guided by language ideologies of correctness. This idealised way of speaking has been widely used as a default assumption and assumes that participants align with a standard language ideology. I suggest that when the idealised way of speaking is not the overtly prescribed standard, but an exogenously stigmatised or otherwise non-standard local variety, such as when validated by a local micro-market, the stylistic distribution can exhibit an inverted pattern.

The intraspeaker variation in this study shows that speakers use more non-standard local forms when their cognitive load is primarily concerned with language use. Thus, many individuals are using more Anglo-Cornish variants in careful speech styles. When speakers use stylised language, they are not only aware that they are changing their use of language, they are projecting a contextually idealised representation of themselves (see also Goffman's (Reference Goffman1959) ‘presentation of self’). Speakers use language to ‘point to’ (see Kiesling Reference Kiesling1998) who they are, who they think they are, or who they would like to be. Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1977: 653) notes that ‘[w]hat speaks is not the utterance, the language, but the whole social person’. Thus, when their attention is elevated, a speaker is not only aware that their use of language is being observed, they are also cognisant of the fact that their use of language provides clues to a range of social characteristics about their self. This self is stylised in careful speech styles.

I suggest that this intraspeaker variation should not be attributed to attention-to-speech (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1972a), but as part of a broader attention-to-self model. When speakers pay greater attention-to-self, they closer approximate a contextually desired self, a target self which they aspire to embody at a given time. For example, when speakers subvert the standard language ideology, their idealised self may not be ‘educated’ or posh’, but ‘local’. Thus, for many Cornish people, particularly those with a strong local identity, the stylistic target can be a ‘Cornish’ self. This identity can be constructed through the use of linguistic features enregistered as ‘Cornish’. This is exemplified by participants’ metalinguistic commentaries, such as Elida's claim that she ‘can speak really Cornish when I want to’. This highlights the fact that Cornishness is only one facet of a speaker's identity, intersecting with a constellation of other aspects of the self. While the attention-to-speech model focused on speech as a distinct system, the attention-to-self model acknowledges the role of speech as a constituent part of a broader semiotic process of identity construction. It also acknowledges the patchwork nature of identity, any aspect of which could be desirable in a given context, depending on interactional, contextual and ideological factors.

In the specific version of the sociolinguistic interview used in this study, where participants were told that I was interested in Cornish dialect and identity, many speakers were keen to exemplify widely accredited values and social traits associated with Cornishness through Anglo-Cornish lexis. Lexis is a diagnostic for regional, and other social, identities (e.g. see Snell Reference Snell, Montgomery and Moore2017; Sandow & Robinson Reference Sandow, Robinson, Braber and Jansen2018), and speakers know it. The regularity of the stylistically conditioned distribution of Anglo-Cornish lexical items demonstrates that this is not a random or idiosyncratic pattern but is sanctioned by social meaning potentials at the level of the community. By employing regionally marked lexis over Standard English alternatives, speakers are making themselves socially and ideologically locatable. They are sign-posting their worldview with lexis as the semiotic index of their Cornish identity.

I suggest that ideological variation becomes more visible when speakers pay greater attention to their speech and, by extension, their self. When speakers are highly conscious of the social meanings of their behaviours, they more closely approximate an idealised version of the self. If an individual conforms to a standard language ideology, such as prescriptive attitudes of ‘correctness’, they align themselves with a standard language market, which manifests in the use of non-regionally marked linguistic variants. Alternatively, if they align themselves with a locally relevant micro-market, then they can make themselves ideologically locatable by stylising their identities through the use of local dialect variants. These differences can become more visible when individuals are acutely aware of the social meaning of their (linguistic or otherwise) behaviours, that is, when attention-to-self is elevated.

The postmodern globalised world has led to dialect levelling, on the one hand, and widespread attention to regional variation, on the other (Johnstone Reference Johnstone and Englebretson2007: 49). In Cornwall, both levelling and increased awareness of dialect variation are present, simultaneously. There is a great deal of lexical attrition in casual speech styles, as the vast majority of speakers use regionally unmarked forms. Yet, when speakers pay attention to the social meaning of their language use, many perform local identity by employing regionally marked lexis. Ryan (Reference Ryan, Giles and St Clair1979: 147) suggests that the ‘value of language as a chief symbol of group identity is one of the major forces for the preservation of nonstandard speech styles or dialects’ and that this use of non-standard forms can be used by speakers in order to ‘distinguish themselves from the established prestige groups’ (Ryan Reference Ryan, Giles and St Clair1979: 148). This is significant in terms of local identity, whereby some individuals with a strong sense of local identity choose not to align their value system with the overtly prescribed standard, but to revert to an alternative local prestige which is valuable on the Cornish micro-market. In doing so, they increase the linguistic and, therefore, social distance between themselves, as ‘Cornish’, and ‘England’ and ‘the English’. Moreover, the usage of Anglo-Cornish dialect in careful speech styles functions as a rejection of the powerlessness of users of Anglo-Cornish on the standard language market and signals alignment with the Cornish micro-market, on which Anglo-Cornish is imbued with symbolic power (cf. Snell Reference Snell2018).

It is important to acknowledge the possibility of demand characteristics influencing the results in this study. That is, speakers used Anglo-Cornish dialect words to please the researcher in some way. There are three key pieces of evidence to consider in relation to this point. Firstly, participants were told that the study was focused on the Anglo-Cornish dialect at the start of the interview. The first lexical elicitation procedures they completed were the spot-the-difference tasks, in which very low rates of Anglo-Cornish dialect words were used. Thus, immediately after potential ‘priming’ of the Anglo-Cornish dialect, very little usage of Anglo-Cornish words was observed. It was only in the naming task, which followed the spot-the-difference tasks and where the cognitive load was more oriented towards vocabulary usage, that Anglo-Cornish dialect words were used much more frequently. Secondly, it was overwhelmingly those with positive orientations to Cornwall, quantified through the high IdQ totals, who exhibited this stylistic shift. The potential demand characteristics did not appear to influence those with lower IdQ totals, suggesting that identity and the social meanings of the Anglo-Cornish variants are an important consideration. Thirdly, the metalinguistic commentaries from participants suggest that this inverted pattern is not an artefact of the experimental nature of this study but is reflective of the purposeful usage of the Anglo-Cornish dialect beyond the context of a sociolinguistic interview. While I acknowledge that the results may have been different if the research had been framed as a study on ‘social class and language variation’ or ‘gender and language variation’, the results nonetheless highlight the fact that speakers can use their stylistic repertoire, in light of attentional demands, to index their Cornishness when interactional and ideological factors are deemed to be apposite. This is not consistent with Labov's (Reference Labov1972b: 112) framing of sociolinguistic style as being ordered along a single dimension, but suggests that contextual and ideological factors can interact with attention to make a range of stochastic predictions regarding sociolinguistic patterns.

4 Conclusions

In this article, I have used place identity, social meaning and language ideology in order to account for an inverted pattern of style-shifting. While typically, the Anglo-Cornish dialect is stigmatised, it is positively evaluated on the Cornish micro-market. When speakers pay greater attention to the social sensibilities of their behaviours and the identity they are constructing, they more closely approximate a desired stylistic target. For many speakers in this study, when their attention-to-self is elevated, they stylise a Cornish self. While the methodological framework employed in this study is relatively novel (see also Sandow & Robinson Reference Sandow, Robinson, Braber and Jansen2018; Sandow Reference Sandow2020, Reference Sandow2021), the data are consistent with the speakers’ metalinguistic observations and Dann's (Reference Dann2019) finding that Anglo-Cornish variants of the bath vowel were more likely to occur in word lists as opposed to conversational speech. Dann's (Reference Dann2019) study showcases the fact that this finding is not limited to the level of lexis, while inverted style patterns in a range of other localities (e.g. Milroy Reference Milroy1987; Reed Reference Reed2016) demonstrate that this pattern is not unique to Cornwall.

Rather than assuming that speakers orient themselves towards the standard in careful speech styles, this study demonstrates that many speakers reject this standard language ideological orthodoxy. When they do so, these speakers can style-shift towards non-normatively prescribed linguistic forms in careful speech styles. This is because, in the context of the locally constructed micro-market, Anglo-Cornish dialect forms can accrue a high level of symbolic capital due to its locally meaningful value. By style-shifting in the inverted direction, many Cornish people are rejecting a system that they feel does not serve them. Much of the Cornish population feel disengaged and disenfranchised by Cornwall's peripherality (see Payton Reference Payton1992). As a result, they orient towards an alternative value system, one which attempts to re-establish the centres of power. Indeed, many Cornish people orient themselves towards a Cornish micro-market, one which not only provides a greater sense of autonomy for Cornwall, but also imbues their locale with a higher cultural value.

While lexis is an understudied level of language from a sociolinguistic perspective (see Beeching Reference Beeching, Pooley and Lodge2011; Durkin Reference Durkin2012; Sandow Reference Sandow2021), this study showcases the structured nature of lexical usage and the ways in which lexis can be employed in order to stylise identities. Those who positively evaluate Cornwall, Cornish identity and the Anglo-Cornish dialect can make use of the higher-order indexical meaning potentials of local dialect lexis in order to embody their locally oriented ideologies. By employing regionally marked lexis over Standard English alternatives, they are making themselves socially and ideologically locatable. They are signposting their worldview with lexis as the semiotic index of Cornish provenance. It is important to note that when Anglo-Cornish speakers use Anglo-Cornish lexis to do identity work, the identity that is being stylised is not uniform. A multitude of Cornish identities can be evoked even through the use of a single lexical item, e.g. emmet (see Sandow Reference Sandow2021).

Inverted style patterns have been observed in localities in which large parts of the population in some way reject the standard language ideology. Examples include Appalachia, Belfast, Glasgow and Cornwall, where identities of place, and pride in the local dialects, are strong. This serves to reframe our understanding of sociolinguistic style and to acknowledge the alternative patterns of intraspeaker variation which can emerge when the standard language ideology is challenged. However, the data on attention-based style-shifting among speakers who do not align with the standard language ideological orthodoxy remain limited. This calls for further study of quantitative sociolinguistic variation in geographically, culturally and economically peripheral localities.