1. Endophoric demonstratives: distinctions and definitions

Demonstratives, such as ‘proximal’ this and ‘distal’ that in English, take up an important position in the system of referential devices that languages offer their users. On the one hand, demonstratives contribute to establishing successful reference to entities within a joint speaker-hearer space, in close coordination with other devices such as deictic bodily gestures (Cooperrider, Reference Cooperrider2016; Levinson et al., Reference Levinson, Cutfield, Dunn, Enfield, Meira and Wilkins2018; Peeters & Özyürek, Reference Peeters and Özyürek2016). On the other hand, they are part of a larger set of referential expressions (e.g., including pronouns and definite noun phrases) that speakers or writers may use to activate or reactivate a discourse referent in the mind of one’s addressee (Ariel, Reference Ariel1990; Cornish, Reference Cornish2011; Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski, Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993). Traditionally, a clear distinction is hence made between the exophoric vs. endophoric use of demonstratives respectively, with exophoric demonstratives referring to actual entities in the speech situation, predominantly studied in spoken interaction, and endophoric demonstratives covering all other uses (e.g., Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Halliday & Hasan, Reference Halliday and Hasan1976).

The exophoric use of demonstratives is largely considered the ontogenetic, phylogenetic, and grammatical precursor from which other types of use have derived (e.g., Bühler, Reference Bühler1934; Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Lyons, Reference Lyons1977; Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2008) and it has been studied in a wide variety of languages (e.g., Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Levinson et al., Reference Levinson, Cutfield, Dunn, Enfield, Meira and Wilkins2018). The study of exophoric demonstratives relies on research tools that enable researchers to unify and compare results coming from different languages and communicative situations. For example, Wilkins (Reference Wilkins, Levinson, Cutfield, Dunn, Enfield, Meira and Wilkins2018) developed an analytical tool that can be used to elicit the basic use of exophoric demonstratives in virtually any spoken language based on a fixed set of interactional configurations between speaker, hearer, and object referent (see Levinson et al., Reference Levinson, Cutfield, Dunn, Enfield, Meira and Wilkins2018). Experimental laboratory studies into exophoric demonstratives also often use comparable spatial (game) setups, likewise enabling refined parametrization of physical and interactional variables, and study their effect on the demonstrative variant speakers decide to use (e.g., Coventry, Valdés, Castillo, & Guijarro-Fuentes, Reference Coventry, Valdés, Castillo and Guijarro-Fuentes2008; Diessel & Coventry, Reference Diessel and Coventry2020; Reile, Plado, Gudde, & Coventry, Reference Reile, Plado, Gudde and Coventry2020).

The empirical study of endophoric demonstratives shows a more divergent picture. Endophoric demonstratives are commonly considered as part of the larger set of referential expressions, either expressing different degrees of mental activation of the underlying referent (e.g., Ariel, Reference Ariel1990; Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993) or different degrees of deictic force to mentally construct the intended referent (e.g., Cornish, Reference Cornish1999). A large number of studies discuss pragmatic functions of endophoric demonstratives going beyond simple reference, and relate demonstratives to the assumed psychological and social relations between writer and addressee (see for an overview, Maes, Krahmer, & Peeters, Reference Maes, Krahmer and Peetersin review; Peeters, Krahmer, & Maes, Reference Peeters, Krahmer and Maes2021). However, in the endophoric domain, helpful tools enabling a unified and comparative analysis including all classes of endophoric demonstratives are lacking.

The aim of this paper is therefore to develop a taxonomy of endophoric demonstrative use, based on the analysis of demonstratives in three representative genres of written texts (narrative, expository, and evaluative). We consider all demonstratives occurring in written discourse endophoric, and here restrict our scope to written non-interactive ‘one-to-many’ discourse aimed at a generic audience, with typical examples being everyday newspaper articles, Wikipedia texts, and written product reviews. The exclusion of one-to-one personal discourse (as in many instances of spoken interaction, and conversational and personal written genres) enables us to focus on situations in which communication partners cannot rely on direct interactional feedback, nor on ‘private’ common ground, two conditions expected to affect the use of demonstratives, in particular, when they are used to access a new referent (e.g., ‘recognitional’ that; Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996), or to construct a referent on the basis of non-nominal antecedents (e.g., discourse deixis; Webber, Reference Webber1988).

Within this scope, we aim at creating an analytical tool enabling analysts to reliably code and exhaustively classify demonstratives in written corpora based on observable surface variables, thus allowing researchers to unify and compare the results of studies on endophoric demonstratives coming from different genres and languages. The taxonomy should provide them with a sound empirical basis for future experimental and analytic work into endophoric demonstratives, for example, when contrasting and testing different theoretical proposals on demonstrative variance (Diessel & Coventry, Reference Diessel and Coventry2020; Peeters et al., Reference Peeters, Krahmer and Maes2021). In testing these proposals, clear and reliable taxonomic distinctions are needed to develop claims about demonstrative variance in different types of demonstrative use in written discourse (Maes et al., Reference Maes, Krahmer and Peetersin review).

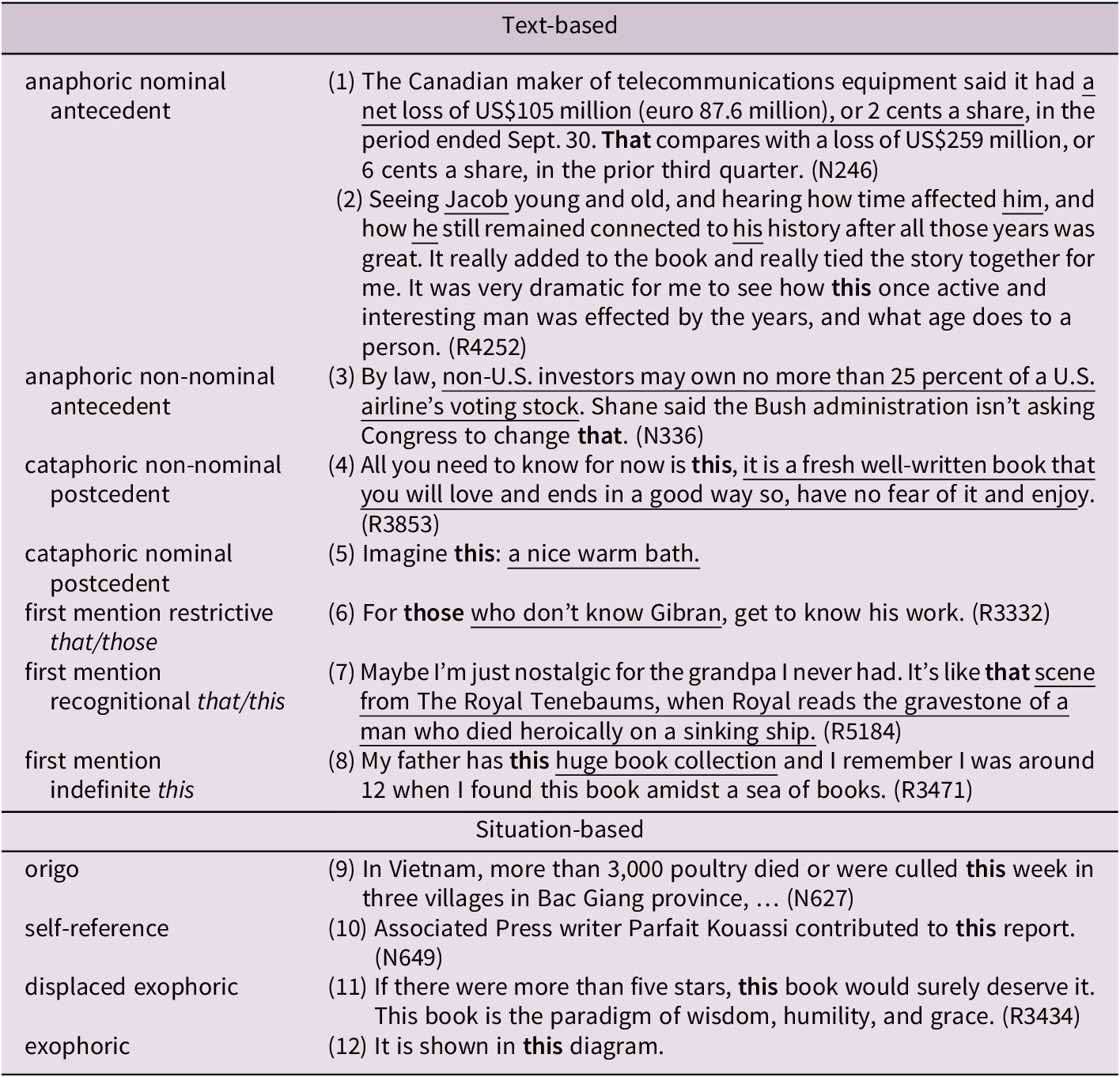

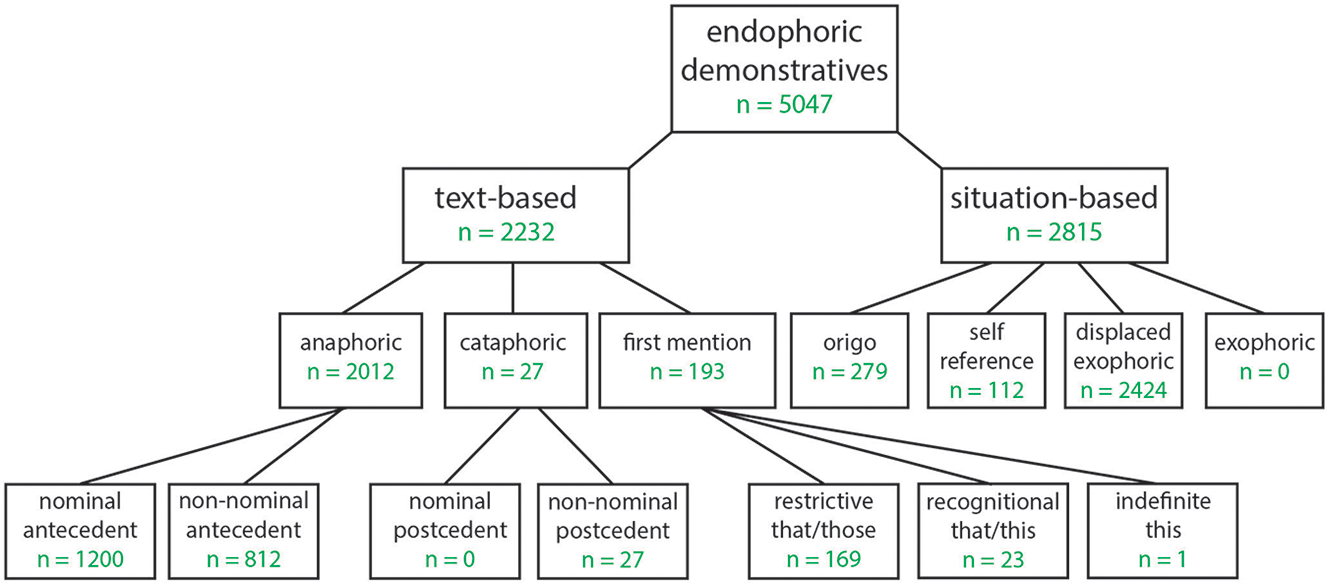

Figure 1 presents our taxonomy and Table 1 provides typical examples for each of the classes we propose. We globally distinguish two main classes of endophoric demonstratives: text-based and situation-based demonstratives. We consider endophoric demonstratives text-based when the discourse context contains explicit linguistic ‘antecedent’ elements: (i) direct or indirect nominal elements (Noun Phrases and pronouns) or non-nominal elements (a Verb Phrase, clause, sentence, and parts or combinations thereof) in the case of anaphoric or cataphoric demonstratives as in examples (1) to (5) and (ii) elements included in the noun phrase (NP) following the demonstrative determiner in cases of first mention demonstratives as in examples (6) to (8).

Table 1. Typical examples for each class in our taxonomy

In these and following examples, we have underlined the proposed antecedent or postcedent, presented the critical demonstrative in boldface, and added the source (News, Wikipedia, and Reviews) and the corpus ID number.

Fig. 1. Proposed taxonomy of endophoric demonstrative reference, and the number of demonstratives observed in our corpus per class, after data exclusion (see Section 2)

Situation-based endophoric demonstratives instead find their interpretation outside the text proper, but in the writing situation: for instance, in relation to the communicative situation of the text (origo), in the container of the text (self-reference), in elements typically activated in specific genres (displaced exophoric), or even in non-linguistic visible objects in multimodal texts (exophoric). Their interpretation is triggered by the absence of explicit linguistic antecedent cues, and by the inability (at least in English) to change the obligatory proximal variant into a distal one (see examples (9)–(12)).

Note that the two basic classes we distinguish roughly represent what traditionally has been termed anaphoric vs. deictic, respectively (e.g., Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Levinson, Reference Levinson and Horn2004). Yet, we will not make use of these notions in this sense, as we consider all endophoric demonstratives deictic. Situation-based demonstratives can be seen as pointing directly to referents outside the written text proper, relatively comparable to the typical deictic function of exophoric demonstratives. Text-based demonstratives are used when a discourse referent needs a deictic device (as compared to a regular pronoun or definite NP) to be accessed properly, as explained in Section 3.1.1.

The definitions of demonstrative classes in our taxonomy are based as much as possible on observable linguistic cues. Still, we fully realize that surface cues represent only a first step in mentally constructing a discourse referent, accessing semantic representations, and making pragmatic inferences associated with demonstrative reference (e.g., Lambrecht, Reference Lambrecht1994; Verhagen, Reference Verhagen2005). We consider the taxonomy as a sound basis for more in-depth analyses of subclasses and borderline cases, in which surface cues are weighed against and complemented with less objective cues, such as assumptions on mental representations of discourse referents.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we discuss the selection and coding criteria of our corpus, which includes text fragments taken from three well-known written genres. In Section 3, we further discuss our taxonomy of endophoric demonstrative classes in detail, based on the coding results and in light of existing taxonomies. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. A corpus approach to endophoric demonstratives

In this section, we discuss the details of the corpus used to develop our taxonomy. We compiled a corpus of 6,884 demonstratives coming from three different, common genres of written discourse: news articles, Wikipedia items, and book reviews. We used different clear-cut genres for reasons of representativity, but also because of the assumed theoretical relevance of genre for endophoric demonstrative variance (Peeters et al., Reference Peeters, Krahmer and Maes2021). The perspective we take is that a taxonomy of endophoric demonstratives should enable us to distinguish and code all demonstratives in a written corpus, and that the classification of demonstratives should be based on analytical variables that can be coded objectively and reliably.

Over the years, different types of corpora have been analyzed for referential expressions in general (e.g., Toole, Reference Toole, Fretheim and Gundel1996; Uryupina et al., Reference Uryupina, Artstein, Bristot, Cavicchio, Delogu, Rodriguez and Poesio2020) or demonstratives in particular (e.g., Botley & McEnery, Reference Botley and McEnery2001a, Reference Botley and McEnery2001b; Byron & Allen, Reference Byron, Allen, Botley and McEnery1998; Maes, Reference Maes1996; Petch-Tyson, Reference Petch-Tyson, Botley and McEnery2000). Although these studies offer valuable distributional information, to the best of our knowledge, no existing corpus presents an in-depth discussion of endophoric classes of demonstratives based on a sizeable and balanced set of well-defined, different written genres. Early proposals often tested their claims on demonstrative variation in small-scale, unbalanced, or genre-unspecific corpora (Ariel, Reference Ariel1988; Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski, Reference Gundel, Hedberg, Zacharski, Vargha and Hajičová1988; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996; Kirsner, Reference Kirsner1979; Oh, Reference Oh2001). Other studies restricted themselves to studying either only anaphoric demonstrative NPs (Maes, Reference Maes1996), abstract (Dipper & Zinsmeister, Reference Dipper and Zinsmeister2012), proximal (Poesio & Modjeska, Reference Poesio, Modjeska, Branco, McEnery and Mitkov2005), or distal (Byron & Allen, Reference Byron, Allen, Botley and McEnery1998; Passonneau, Reference Passonneau1989) demonstratives, to a single genre (Acton & Potts, Reference Acton and Potts2014; Botley & McEnery, Reference Botley and McEnery2001b; Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski, Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski2004; Hedberg, Gundel, & Zacharski, Reference Hedberg, Gundel and Zacharski2007; Potts & Schwarz, Reference Potts and Schwarz2010), or they did not explicitly define the categories used (Botley & McEnery, Reference Botley and McEnery2001a, Reference Botley and McEnery2001b).

The corpus together with the annotations is publicly available via the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/b32xz/).

2.1. Selection of the corpus

We selected English texts coming from three written genres: narrative (news articles), expository (Wikipedia texts), and evaluative (book reviews). The news texts consisted of Associated Press news articles (n = 2,021) on national and international news from the period 2004–2006, taken from the AQUAINT-2 Information-Retrieval Text Research Collection (Voorhees & Graff, Reference Voorhees and Graff2008). Wikipedia entries (n = 1,755) were taken from the GREC corpus, and consisted of topics on persons, mountains, rivers, cities, and countries (Belz, Kow, Viethen, & Gatt, Reference Belz, Kow, Viethen, Gatt, Krahmer and Theune2010). The book reviews (n = 1,904) were taken from the Amazon product data corpus (He & McAuley, Reference He and McAuley2016; http://jmcauley.ucsd.edu/data/amazon/), and were written in a more informal style by assumedly less professional writers.

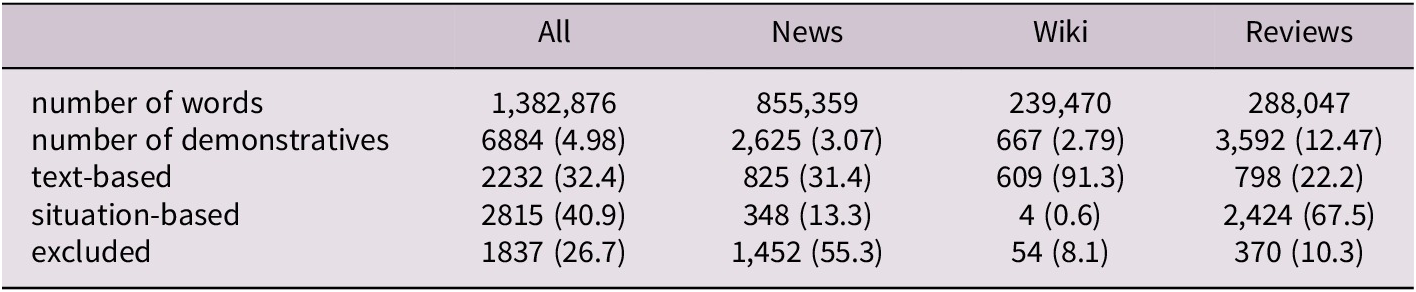

2.2. Data exclusion and coding

We used the Stanford CoreNLP system (https://stanfordnlp.github.io) to tokenize text in the corpus, and to extract lemmas and parts-of-speech. Paragraphs were the input in the news and Wikipedia texts, complete reviews were the input in the review texts. We selected the complete set of Wikipedia texts in the GREC corpus and the first 3,000 paragraphs from the news and the reviews corpus. We automatically retrieved all sentences that contained at least one demonstrative, plus the three sentences that preceded the retrieved sentence (or as many preceding sentences as possible when the retrieved sentence was the first, second, or third in the text). Only demonstrative determiners and demonstrative pronouns were included, thus excluding other uses of that (conjunction, complementizer, and relative pronoun). This resulted in 6,156 fragments (news n = 2,503; Wikipedia n = 660; and reviews n = 2,993) with one or more demonstratives, some of them partially overlapping with other fragments. For each of these fragments, we first manually coded all demonstratives (n = 6,884) according to their main endophoric class (text-based vs. situation-based). Table 2 shows substantial differences in the total number of observed demonstratives (in particular per 1,000 words) across the three genres.

Table 2. Across the three genres (All), and per genre (News, Wiki, and Reviews), the overall number of words, the number of demonstratives in total (and per 1,000 words between brackets), and the number (and percentages between brackets) of text-based, situation-based, and excluded demonstratives

In total, from this first selection, 1,837 demonstratives were excluded prior to analysis. As one of our aims was for the taxonomy to be useful in contrasting and testing theoretical proposals on demonstrative variance (Maes et al., Reference Maes, Krahmer and Peetersin review; Peeters et al., Reference Peeters, Krahmer and Maes2021), we excluded 1,283 demonstratives (832 proximal), almost all from the news texts, because they were part of quoted text. A quotation makes the demonstrative form (e.g., proximal vs. distal) unreliable, in particular, when it is impossible to determine whether the chosen demonstrative variant is literally taken from an original context, or adapted when written up by the journalist. Furthermore, 354 demonstratives (225 proximal), most probably anaphors, were excluded due to the automatic selection procedure, with the (demonstrative) anaphor sentence being selected in the absence of the sentence containing the antecedent. Furthermore, a total of 169 duplicates were excluded. Finally, we excluded a small number of degree modifier demonstratives (e.g., this/that much; n = 31, 10 proximal), apparently also considered a determiner by the automatic parser. Although these examples show demonstrative variation and can be seen as an extension of regular deictic reference (Klipple & Gurney, Reference Klipple, Gurney, van Deemter and Kibble2002; König & Umbach, Reference König, Umbach, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018; Labrador, Reference Labrador2011), we did not include them, as they do not access a discourse referent; they are adverbials followed by an adjective, and thus do not fit the coding variables we used to analyze the demonstrative pronouns and determiners.

As a starting point for our taxonomy, we first divided the remaining endophoric demonstratives (n = 5,047) into two overarching categories based on the source of interpretation, as shown in Fig. 1: text-based demonstratives having explicit antecedent or postcedent triggers in the surrounding text; situation-based demonstratives, obligatorily proximal in English and finding their interpretation triggers outside the text proper but in the writing situation.

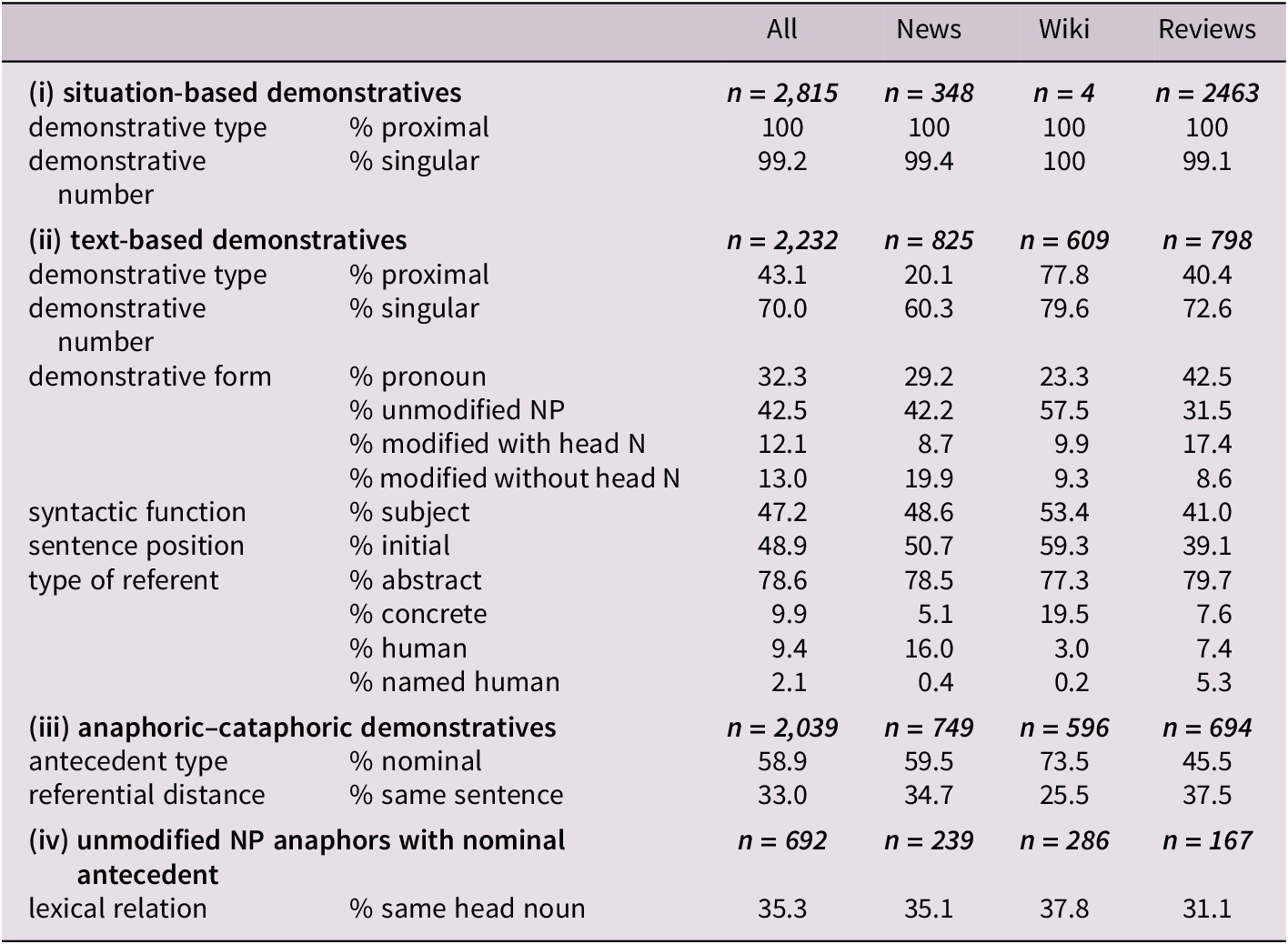

We coded the remaining text-based (n = 2,232) and situation-based (n = 2,815) demonstratives on their demonstrative type (proximal this/these vs. distal that/those) and demonstrative number (singular this/that vs. plural these/those). Furthermore, we coded all text-based demonstratives with regard to variables that could be assigned objectively and which were deemed relevant to explain demonstrative functions and demonstrative variance, thus enabling us to test different theoretical proposals on demonstrative variance elsewhere (Maes et al., Reference Maes, Krahmer and Peetersin review). These were demonstrative form (pronominal vs. unmodified vs. modified NP with and without head noun, for example, those vs. those people vs. those great people vs. those who are great), syntactic function (subject vs. non-subject), sentence position (initial vs. non-initial), type of referent (abstract vs. concrete vs. human vs. named human). In addition, for anaphoric and cataphoric demonstratives (n = 2,039), we coded the following variables: antecedent type (nominal vs. non-nominal), referential distance (same sentence vs. previous sentence(s)). Finally, for unmodified anaphoric NPs with a nominal antecedent (n = 692), we coded the lexical relation between the anaphor noun and the head noun of their antecedent (same vs. different noun).

2.3. Descriptive observations

Table 3 presents the distribution of demonstratives across the coded variables, overall and separately for the three genres. Situation-based demonstratives in our corpus, by definition exclusively proximal, were almost all singular (99.2%). As to text-based demonstratives, stable across the three genres, a strong preference was observed for singular (70%) vs. plural demonstratives, for antecedents in previous sentence(s) (67.0%) rather than in the same sentence, and for different (64.7%) vs. the same head nouns. There was a preference for demonstrative NPs (67.7%) vs. pronouns, which resonates well with a long tradition of stylistic guidelines and prescriptions in favor of the use of NP over pronominal demonstratives (Finn, Reference Finn1995; Geisler, Kaufer, & Steinberg, Reference Geisler, Kaufer and Steinberg1985; Moskovit, Reference Moskovit1983; Rustipa, Reference Rustipa2015; Wulff, Römer, & Swales, Reference Wulff, Römer and Swales2012), and with studies concluding that essays with a higher proportion of pronominal demonstratives are more difficult for readers, although at the same time receiving higher marks from trained essay raters (Crossley, Rose, Danekes, Rose, & McNamara, Reference Crossley, Rose, Danekes, Rose and McNamara2017). Also, there was a preference for higher order, abstract (78.6%) vs. concrete or human referents and a relatively high proportion of demonstratives with non-nominal antecedents (41.1%), pointing at a majority of demonstratives accessing abstract referents. Finally, modified NPs with and without head noun (25.1%, n = 561) were partly first mention demonstratives (n = 193), partly anaphoric (n = 368). In the latter case, they typically predicated new information on an activated referent, as in example (2) (e.g., Cornish, Reference Cornish2011; Maes & Noordman, Reference Maes and Noordman1995).

Table 3. Across the three genres (All), and per genre (News, Wiki, and Reviews) (i) the proportion of situation-based demonstratives for the variables demonstrative type: proximal (vs. distal) and number: singular (vs. plural), (ii) the proportion of text-based demonstratives for the variables demonstrative type: proximal (vs. distal), number: singular (vs. plural); form: pronouns, unmodified NPs, modified NPs, modified elliptic NPs; syntactic function: subject (vs. non-subject); sentence position: initial (vs. non-initial); and type of referent: abstract, concrete, human vs. named human; (iii) the proportion of anaphoric and cataphoric demonstratives for the variables antecedent type: nominal (vs. non-nominal); and referential distance: same sentence (vs. earlier sentence); (iv) the proportion of unmodified NP anaphora with nominal antecedent with either a lexically same (vs. different) head noun.

Other variables showed considerable variation over the three genres. There was a huge difference in demonstrative type across genres, with the news and reviews texts having a (strong vs. weak) preference for distal demonstratives (79.9% and 59.6% respectively), while the Wikipedia texts displayed a strong proximal preference (77.8%), highlighting the importance of discourse genre in explaining demonstrative variance as we argued for elsewhere (Maes et al., Reference Maes, Krahmer and Peetersin review; Peeters et al., Reference Peeters, Krahmer and Maes2021). Also, demonstratives in the book reviews predominantly took up a non-subject (59%) and non-initial (60.9%) sentence position.

2.4. Reliability of the coding

Although the coding of the demonstratives for the various variables is fairly objective and formal in nature, about 10% of the data (n = 689; 222 situation-based and 467 text-based demonstratives) was independently coded by a second coder. For each of the coding variables, the agreement between the two coders was between 96.3% and 98.7%. In total, 69 coding differences were found in 60 out of the 689 fragments (7 situation-based; 62 text-based: 14 demonstrative form, 17 antecedent type; 14 distance, 11 syntactic function, 6 sentence position). Most of these (78%) were simple errors made by one of the coders. Some other coding differences were borderline cases or were resolved after discussion, in particular, concerning the exact type or extension of the antecedent, or the difference between a nominal or non-nominal antecedent, as in example (13). The coded corpus, as well as details of the second coding procedure, are available online via the OSF entry for this study.

3. A new taxonomy of endophoric demonstratives

In this section, we will discuss our taxonomy class by class and relate it to the properties of the demonstratives observed in the corpus and to choices made in alternative, existing approaches. Some earlier distinctions originate from the study of exophoric demonstratives in interactional discourse (Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996; Levinson, Reference Levinson and Horn2004), while others are developed within an endophoric tradition (e.g., Ariel, Reference Ariel1990; Cornish, Reference Cornish2001; Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019; Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993; Halliday & Hasan, Reference Halliday and Hasan1976). We will also include ideas and proposals coming from studies of particular uses of demonstratives, such as bridging demonstratives (Lücking, Reference Lücking, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018) or demonstratives with non-nominal antecedents (e.g., Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper, & Zinsmeister, Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018). The discussion of our taxonomy below will follow the classes distinguished in Fig. 1 and discuss these one by one.

3.1. Text-based endophoric demonstratives

In our taxonomy, we distinguish three classes of text-based endophoric demonstratives: anaphoric, cataphoric, and first mention demonstratives. Anaphoric demonstratives (n = 2,012) find their interpretation trigger in an antecedent that by definition precedes it, as in examples (1), (2), and (3). They can be further subdivided as a function of whether the antecedent has a nominal (examples (1) and (2)) or non-nominal form (example (3)). Cataphoric demonstratives were observed substantially less often (n = 27) and all had a non-nominal ‘postcedent’, as in example (4). Finally, first mention demonstratives (n = 193) were observed to flexibly create a new discourse referent on the spot, with a productive class formally restricted to a distal demonstrative followed by a post-modification (n = 169), for example, a relative clause as in example (6), and a smaller category introducing a new referent using a modified NP (n = 24), as in examples (7) and (8). We will now discuss these three text-based classes in more detail, relate them to earlier work, and discuss several borderline cases to illustrate our coding and classification procedures.

3.1.1. Anaphoric demonstratives

Our classification of anaphoric demonstratives differs from existing taxonomies that consider anaphoric and discourse deictic demonstratives as conceptually distinct classes (e.g., Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996; Levinson, Reference Levinson and Horn2004). In these taxonomies, anaphoric demonstratives are proposed to track discourse entities with a past and a future. They refer to ‘pre-existing’ or ‘pre-activated’ discourse entities, established in previous discourse via a nominal antecedent, which then often persist in subsequent discourse. Discourse deictic demonstratives, on the other hand, are typically argued to ‘point’ at a variety of non-nominal stretches of preceding discourse, thereby connecting this information to the current sentence. As such, they are usually considered ‘impure’ deictic devices: they do not refer to clearly definable pre-existing entities, but create entities on the spot, which rarely persist in subsequent discourse (e.g., Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Hauenschild, Reference Hauenschild, Weissenborn and Klein1982; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996; Lyons, Reference Lyons1977). Although we acknowledge this distinction, and consider the type of antecedent (nominal vs. non-nominal) indeed as a crucial analytical variable, we propose to attenuate the conceptual distinction between nominal/anaphoric and non-nominal/discourse deictic. This position is inspired by the behavior of demonstratives in our corpus and congruent with ideas proposed elsewhere (see e.g., Cornish, Reference Cornish2001; Ehlich, Reference Ehlich, Jarvella and Klein1982; Kolhatkar et al., Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018; Piwek, Beun, & Cremers, Reference Piwek, Beun and Cremers2008).

First, we consider demonstratives with nominal and non-nominal antecedents both deictic, as their referents need the deictic force of a demonstrative (rather than a regular pronoun or definite NP) to be accessed properly. In case of nominal antecedents as in example (1), demonstratives more often have a non-subject antecedent than regular pronouns (e.g., Brown-Schmidt, Byron, & Tanenhaus, Reference Brown-Schmidt, Byron and Tanenhaus2005; Çokal, Sturt, & Ferreira, Reference Çokal, Sturt and Ferreira2014; 2018; Fossard, Garnham, & Cowles, Reference Fossard, Garnham and Cowles2012; Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008), and bring less accessible entities into focus (e.g., Ariel, Reference Ariel1990; Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993, Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski2004; Hauenschild, Reference Hauenschild, Weissenborn and Klein1982; Linde, Reference Linde and Givón1979). In their function as determiner in a (modified) demonstrative NP accessing highly activated referents, as in example (2), they create additional inferences compared to definite determiners (e.g., ‘predicating’ demonstrative NPs, Cornish, Reference Cornish2011; de Mulder, Reference De Mulder1998; Doran & Ward, Reference Doran, Ward, Gundel and Abbott2015; Gaillat, Reference Gaillat2016; Goethals, Reference Goethals2013; Kleiber, Reference Kleiber1991; Maes & Noordman, Reference Maes and Noordman1995; Schnedecker, Reference Schnedecker2006). In the case of non-nominal antecedents and higher order abstract referents, as in example (3), demonstratives are found to be used more frequently than pronouns (e.g., Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski2004; Kolhatkar et al., Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018; Maes, Reference Maes1997). Demonstratives also enable access to new referents (e.g., recognitional that or indefinite this as in examples (7) and (8)) more easily than definite NPs, and more easily allow cataphoric relations, as in example (4), than pronouns. Finally, they are also more powerful in creating mental representations of referents based on indirect cues, as we will see below: both nominal cues (e.g., in deferred/bridging or generic reference, Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019; Lücking, Reference Lücking, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018) and non-nominal cues (e.g., discourse deixis, Cornish, Reference Cornish, Nilsen, Amfo and Borthen2007; referent coercion, Kolhatkar et al., Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018; Webber, Reference Webber1988). All these observations justify them to be considered a combination of deixis and anaphora, captured adequately by the notion of anadeixis (e.g., Cornish, Reference Cornish2001, Reference Cornish, Nilsen, Amfo and Borthen2007, Reference Cornish2011; Ehlich, Reference Ehlich, Jarvella and Klein1982).

Second, we consider demonstratives with nominal and non-nominal antecedents both anaphoric, in the sense that they always require some explicit antecedent trigger being present in the text. This condition is widely accepted for anaphors with nominal antecedents, but the ‘required presence’ of a non-nominal trigger should also be seen as a necessary condition for the construction of abstract referents (e.g., Kolhatkar et al., Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018; Recasens, Reference Recasens2008; Webber, Reference Webber1988).

Third, anaphoric demonstratives with nominal antecedents in our corpus do not typically enable access to discourse referents ‘with a past and a future’. Most of these antecedents (78.6%) actually refer to abstract entities, they are often derived from verbs as in example (1), and rarely refer to persistent referents. This makes them conceptually similar to the referents accessed by non-nominal antecedents. In many cases, it is even unclear whether the antecedent is nominal or non-nominal, as we observed in our second coding exercise. For instance, in example (13), we may consider the whole NP (the fact that…) or only the that-clause as the nominal or non-nominal antecedent respectively. Whatever (subjective) interpretation we take, in either case, the demonstrative is roughly referring to the same conceptual entity.

Finally, we include in the two anaphoric classes regular cases as well as borderline cases, as we see this as the best starting point for more in-depth analyses of these cases. Scholars from different backgrounds use different labels for different types of borderline cases. Nominal antecedents are said to enable bridging, deferred, indirect, and/or inferrable reference (e.g., Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski2004; Prince, Reference Prince, Joshi, Webber and Sag1981a), while non-nominal antecedents have been claimed to allow coercion, ostension, or indirect reference (e.g., Hedberg et al., Reference Hedberg, Gundel and Zacharski2007; Kolhatkar et al., Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018; Webber, Reference Webber1991). Here, we will review some borderline cases as we found them in the corpus.

Borderline cases of demonstratives with nominal antecedents are mostly characterized by anaphor referents having a different semantic interpretation or denotation compared to their antecedent referent. Typical cases involving quantificational shifts, often discussed in semantic accounts of demonstratives, were not found in our corpus (e.g., “ Every dog in the neighborhood, even the meanest, has an owner who thinks that that dog is a sweetie”; Roberts, Reference Roberts, van Deemter and Kibble2002, p. 93). Shifts between a generic and a specific referent interpretation (Bowdle & Ward, Reference Bowdle, Ward, Ahlers, Bilmes, Guenter, Kaiser and Namkung1995; Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019) are illustrated in the shift from a specific (a story) to a generic (these stories) referent in example (14), or the other way around (elephants → this one [elephant]) in example (15).

We coded a small number of demonstratives (n = 16) as bridging inferences (e.g., Apothéloz & Reichler-Béguelin, Reference Apothéloz and Reichler-Béguelin1999; Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019), most of them having distal forms (n = 12) and/or coming from the book reviews (n = 13). Example (16) presents a fairly standard case based on a general knowledge inference (the “Our Father” in Polish → those words). Most other cases, however, partly also rely on genre-specific knowledge, in particular, on assumed knowledge of the book reviewed, and thus also have a displaced exophoric flavor, as in example (17) where all those chapters refer to the substantial part of the story that is situated in a retirement home.

As noted in previous work, demonstratives can furthermore sometimes defer reference (“A car drove by. The horn was honking. Then another car drove by. That horn was honking even louder,” e.g., Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019; Lücking, Reference Lücking, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018; Wolter, Reference Wolter2006). In the corpus, we did not observe such cases, but we did find a productive class of deferred elliptic those/that anaphors (n = 156), as in example (18), where the demonstrative picks out the head noun of the antecedent NP (Cubans) to create a new entity (wet foot Cubans).

Finally, some demonstratives rely on information present in the previous discourse, but without representing a clear reference, as in example (19), where the demonstrative NP (that point) refers to a point in the story that is implied in the writer’s strategy of foreshadowing. These cases are often distal, like in semi-fixed expressions (e.g., at that, that being said, for that matter), and their semantic borderline type is hard to determine.

In sum, borderline cases of demonstratives with nominal antecedents show a varied picture. Yet, for all of them, the initial interpretation trigger can be found in the text, which is why we classified them all as anaphoric demonstratives.

For demonstratives with non-nominal antecedents, distinguishing between regular and borderline cases is much more complex. Apart from discussions on the nominal vs. non-nominal status of the antecedent, as in example (13), analysts have to find the exact syntactic extension of the antecedent, the semantic type of the anaphor, and the semantic type of the antecedent. In particular, the semantic interpretation turns out to be notoriously difficult, as both the antecedent and the anaphor can have a different semantic interpretation, to be selected from a fluid list of object types with increasing degrees of abstractness, including events, states, situations/facts, or propositions/speech acts (Asher, Reference Asher1993; Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski2004; Kolhatkar et al., Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018). Because of these complexities, early annotation attempts restricted themselves to distinguishing between direct and indirect cases of non-nominal demonstrative reference (Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski2004; Hedberg et al., Reference Hedberg, Gundel and Zacharski2007).

More recently, Dipper & Zinsmeister (Reference Dipper and Zinsmeister2012) developed an annotation system based on three linguistic tests, applied here to example (13). The namely test identifies the antecedent in a namely construction following the demonstrative (this → this, namely (the fact) that the Amazon has no clouds above its channel near its mouth). The NP-replacement test adds a noun to the demonstrative, taken from a fixed list, and identifies the semantic type of the demonstrative anaphor (this → this state of affairs/situation/fact). The colon test adds a writer’s statement in front of the antecedent, and so identifies the semantic type of the antecedent (I state the fact: “the Amazon has…”). The combination of these tests allows these authors to detect semantic shifts between anaphor and antecedent with a fair level of intersubjective reliability, by using expert annotators and lists of nouns and statements connected to different abstractness levels.

Discussions remain however, as the linguistic tests do not prevent that several nouns or statements are acceptable at the same time. In example (13), the antecedent is clearly presented as a fact, but it remains unclear whether the anaphor has to be interpreted as a state, a situation, or a fact. Example (3) can be given a regular interpretation with the antecedent and the anaphor being both state-of-affairs or situations (i.e., Congress being asked to change the situation or state-of-affairs described in the antecedent sentence) or a slightly shifted one with an anaphor representing an action-event inferred from the antecedent (i.e., Congress being asked to carry out the action of changing the law which is responsible for the situation described in the antecedent). Also, the tests are not always easily applicable, for example in the semi-fixed construction in example (20), where the demonstrative refers to the container of the previous sentence or perhaps to the illocutionary act of saying, rather than to states, facts, or propositions expressed in the sentence.

In sum, congruent with our view, non-nominal antecedents are considered a necessary condition for the linguistic tests to be applied properly. Although the tests do not guarantee unambiguous coding of all subtle semantic changes between non-nominal antecedents and demonstrative anaphors, they are very useful in distinguishing regular from borderline cases.

3.1.2. Cataphoric demonstratives

Endophoric demonstratives also allow for cataphoric relations with nominal or non-nominal postcedents (see example (4)). Most taxonomies restrict these to proximal demonstratives with non-nominal postcedents (Chen, Reference Chen1990; Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg, Zacharski, Vargha and Hajičová1988; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996), although occasional distal cases have been reported as well (Danon-Boileau, Reference Danon-Boileau, Grésillon and Lebrave1984; Fraser & Joly, Fraser & Joly, Reference Fraser and Joly1980; Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech, & Svartvik, Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985), and cross-linguistic differences in whether the proximal or distal (or any other) form functions as the preferred or ‘unmarked’ cataphoric demonstrative are expected. In our corpus, we found a small number of cataphoric demonstratives (n = 27). Six of them include a distal demonstrative, but all these can be considered borderline cases between an anaphoric and cataphoric interpretation, as in example (21) where the distal demonstrative can also be said to vaguely refer to the preceding proposition. The absence of cataphoric demonstratives with nominal antecedents in the literature and in our written corpus does not radically exclude such cases, as in example (5), but it is clear that they more typically fit in an interactive (and spoken) context.

3.1.3. First mention demonstratives

Apart from anaphoric and cataphoric demonstratives, we distinguish a variety of demonstratives (n = 193) used to introduce a new entity. We consider them text-based because the NP information following the demonstrative includes necessary triggers for an acceptable interpretation. In that sense, it is reasonable to consider them cataphoric as well, as has been done elsewhere (Deichsel & von Heusinger, Reference Deichsel, von Heusinger, Hendrickx, Devi, Branco and Mitkov2011; Gary-Prieur, Reference Gary-Prieur1998; Labrador, Reference Labrador2011, see also Kolhatkar et al., Reference Kolhatkar, Roussel, Dipper and Zinsmeister2018 for a similar use of the notion of cataphoric). In the corpus, their characteristics deviated from the general picture presented in Table 3: they are modified, often take up a non-subject function (81.9%) and non-initial (75.6%) sentence position, and are predominantly used in reference to first order (human or concrete) entities (88.6%), thus very much similar to the ‘predicating’ anaphoric modified demonstrative NPs.

An example of a first mention demonstrative that is extensively discussed in existing literature is recognitional that (e.g., Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter, & Veenstra, Reference Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter, Veenstra, Coniglio, Murphy, Schlachter and Veenstra2018; Cornish, Reference Cornish2001; Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996). The crucial characteristic of this class of first mention demonstratives is the assumption on the part of the speaker or writer that the addressee will be able to identify the intended referent on the basis of the newly provided information (Cornish, Reference Cornish2001; Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993). Two additional modality-specific conditions are that the demonstrative is meant to signal to the addressee that a given referential expression may be elaborated on if necessary (Auer, Reference Auer, Hindelang and Zillig1981; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996; Schlegloff, Reference Schlegloff and Fox1996), and that the NP information is assumed to be privately shared between speaker and hearer (Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019). These two latter conditions hence do not apply in written communication where direct feedback is not available or audiences may be unknown. Therefore, in our corpus, recognitional demonstratives tend to stay more on the safe side and suggest only a generic type of familiarity, often combined with an attitudinal or rhetorical stylistic effect, as illustrated in examples (7) and (22). Note that the distal demonstrative in example (7) remains acceptable, even for readers not acquainted with the scene of the Royal Tenebaums, and that the effect of the demonstrative remains the same when reference to the new entity is repeated, as in example (22), the latter being observed in Norwegian as well (Johannessen, Reference Johannessen2008).

We should mention here that some scholars also discuss examples of unmodified recognitional or familiar that (“I couldn’t sleep last night. That dog (next door) kept me awake,” Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993, p. 277; “[Sticker on rear window of car] Mind that child! He may be deaf,” Cornish, Reference Cornish2001, p. 300). Although one may see familiarity indeed as part of the pragmatic interpretation of these demonstratives, their acceptability also depends on generic scenario knowledge (dogs being part of neighborhoods; children being vulnerable in traffic), rather than individual knowledge about one specific dog or child. Moreover, the two cases have an exophoric flavor: the location of the rear window sticker activates the relevant exophoric context, and addressees with private knowledge of that annoying dog next door may give that dog a displaced situational interpretation (Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996, p. 220–221). So, in non-interactive written discourse, where such conditions do not apply, we consider the presence of NP information crucial for these first mention demonstratives.

For indefinite this, as in example (8), roughly the same story holds. Proximal demonstratives in English are able to introduce new ‘indefinite’ referents (MacLaran, Reference MacLaran1980; Prince, Reference Prince and Cole1981b), but only if they can assure the reader that enough information is provided in the modified NP, and again with the demonstrative as a signal marking the upcoming new information, together with the pragmatic ‘proximal’ inference that the speaker or writer will provide this information. A typical context for these proximal NPs is the presentational sentence (e.g., She is this lawyer! Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019, p. 250), but a similar effect can also be found in predicating anaphoric demonstratives as in example (23). In these instances, highlighting new information is combined with a positive evaluation based on the degree modifying effect of demonstratives (e.g., she is so good as a lawyer).

In our corpus, recognitional that and indefinite this were found almost exclusively in the book reviews (n = 23), attesting their informal nature. The distal cases (n = 15) represent typical cases of recognitional or familiar thatN. Only one of the remaining proximal cases could be replaced by an indefinite determiner, that is, in example (8). The others evoked similar inferences of familiarity based on assumed knowledge of the activated book, thus combining familiarity with a flavor of displaced exophoricity, as in example (24). All had a modified NP format, except example (25), where the reader of the book review is assumed to know that the referents of the distal and proximal unmodified demonstratives that barn, those years, and this man, as well as the referent of these poor men and women are to be found in the book, while those summers with my Grand-dad, a referent playing a part in the reviewer’s private life, again is modified with sufficient private (although not privately shared) information.

The most productive type of first mention demonstratives we observed are so-called restrictive that/those (n = 167) cases, found in all three text genres (news 75, wiki 13, and reviews 81): postmodified distal demonstratives without a head noun, as illustrated in example (6). Again, here the acceptability of the demonstrative type depends on the information provided by the subsequent relative clauses. These cases have a typical syntax and do not allow for replacement by a proximal variant. Semantically, they are somewhat related to quantificational demonstratives (Doran & Ward, Reference Doran and Ward2019; MacLaran, Reference MacLaran1980), and akin to deferred anaphoric demonstratives as in example (18).

3.1.4. In sum

We have proposed three main classes of text-based endophoric demonstratives. Anaphoric demonstratives, both in pronominal use and when part of a demonstrative NP, can have nominal and non-nominal antecedents, and include regular as well as borderline cases. Cataphoric demonstratives have a postcedent that is most typically non-nominal. First mention demonstratives are used to introduce new referents on the spot, thereby relying on information in the demonstrative NP. Objective formal variables (e.g., the presence of antecedent information preceding or following the demonstrative, or included in the demonstrative NP) suffice to distinguish the three main classes, as well as some subcategories, such as demonstratives with non-nominal antecedents or restrictive that demonstratives.

3.2. Situation-based endophoric demonstratives

In sharp contrast with text-based demonstratives, situation-based endophoric demonstratives find their interpretation outside the ongoing text. We used two analytic criteria to define robust and objectively measurable classes of situation-based endophoric demonstratives. First, the impossibility, at least in English, for a proximal form to be reasonably replaced by a distal form, as situation-based endophoric demonstratives in English are exclusively proximal and almost always have a singular NP format. Second, the absence of explicit linguistic antecedent information. Apart from that, we assume for all situation-based demonstratives the mental presence of a referent being activated on the basis of either the standard coordinates of a communicative situation or genre-specific assumptions. Taking into account these criteria, we distinguish four classes of situation-based demonstratives (cf. Fig. 1), which are illustrated below.

3.2.1. Origo demonstratives

Each communicative situation is intrinsically connected to a here-and-now (Bühler, Reference Bühler1934), which provides the opportunity to use situation-based demonstratives in reference to the origo of the ongoing discourse, as in example (9). This includes examples such as this week, this era, this room, or this country, which have previously been termed ‘symbolically exophoric’ (Levinson, Reference Levinson and Horn2004). These demonstratives are commonly observed in spoken discourse, but also occur in written text. In our corpus, the frequency of origo-based demonstratives differed substantially as a function of text genre: the news texts were responsible for 90% (n = 246) of all cases, consistent with the important role of space and time in news items.

Endophoric demonstratives can also refer in terms of a projected, transposed, imagined, or displaced origo (Bühler, Reference Bühler1934; Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Levinson, Reference Levinson and Horn2004; Lyons, Reference Lyons1977). In our corpus, we however found them in these cases to be dependent on antecedent information needed to evoke a projected origo. Example (26) is taken out of the narrative part of a book review. The demonstrative has a clear antecedent, and replacement by a distal variant is a matter of stylistic effect rather than a drastic change of semantics (as would be in the case of origo deixis). In our taxonomy, this makes them text-based and therefore not situation-based.

3.2.2. Self-reference demonstratives

Each communicative situation also allows for self-reference via demonstratives, as in example (10). Such use of demonstratives includes deictic expressions referring to ‘the container’ rather than the content of the ongoing discourse, such as this chapter, this conversation, this article, this manual, etc. (e.g., Gundel et al., Reference Gundel, Hedberg, Zacharski, Vargha and Hajičová1988; Hauenschild, Reference Hauenschild, Weissenborn and Klein1982; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996; Paraboni & van Deemter, Reference Paraboni, van Deemter, van Deemter and Kibble2002). In our corpus, self-references (n = 112) were all NPs, almost all referring to the news reports (n = 102), as in example (10), and in exceptional cases also to the Wikipedia article (n = 3) or book review (n = 7).

Traditional taxonomies sometimes discuss borderline cases of self-reference when they distinguish between references to propositions (i.e., discourse deixis or ‘impure’ deixis) and references to the ‘material side of language’, i.e., [pure] text deixis (Cornish, Reference Cornish1999; Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996; Lyons, Reference Lyons1977; Webber, Reference Webber1991). In example (27), that word does not refer to the meaning of unsophisticate but to the container of the meaning, similar to example (20). Although we consider this a valid distinction, adding to the other subtle semantic distinctions found in anaphoric demonstratives, the presence of clear antecedent information makes these latter cases, as in example (27), according to our taxonomy, text-based and not situation-based.

3.2.3. Displaced exophoric demonstratives

Some demonstratives in the corpus enabled direct access to entities typically associated with specific written genres, and thus assumed to be activated on the basis of genre-specific knowledge. This class is particularly productive in the book reviews, as almost all reviews refer to this book as if it was physically present, as in example (11). These demonstratives can introduce the referent in a flexible way, using a pronoun only, as in example (30), a bridging inference as in example (31), or a generic demonstrative as in example (32).

We expect these displaced exophoric demonstratives to show up in many other genres as well. Manuals or product reviews, for instance, typically almost by default activate particular products or services. This results in a productive class of displaced exophoric demonstratives, reminiscent of displaced situational demonstratives (Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann and Fox1996, p. 220–222).

3.2.4. Exophoric demonstratives

Situation-based endophoric demonstratives can paradoxically also be exophoric, for instance, when they refer to non-linguistic objects physically present in multimodal written genres, as via the words this diagram or this photograph, see example (12). They cannot be considered text-based, as the crucial cue for the interpretation of these demonstratives is not a linguistic one. On the other hand, they do not point at a genuine exophoric object either, as the referent can be seen as integral to the interpretation of the text. Therefore, we consider these cases endophoric situation-based exophoric demonstratives. In the corpus, due to the nature of the selected texts, they were not observed.

3.2.5. In sum

In the proposed taxonomy, situation-based demonstratives are demonstratives finding their interpretation in the origo of the discourse, in the container of discourse itself, in prominent (displaced) entities in the writing situation, or in non-linguistic objects present in multimodal written texts. None of them can reasonably be replaced by the distal variant in English and no linguistic antecedent is available. As a final note, it is worth mentioning that the usage most central in the study of exophoric demonstratives (this here vs. that there) did not show up in our endophoric corpus.

4. Conclusion

The corpus data presented in the current study allowed us to develop a new taxonomy of endophoric demonstrative reference. We conclude that the taxonomy enables a reliable coding of a large and varied corpus of endophoric demonstratives. Endophoric demonstratives are re-categorized on the basis of easily measurable criteria. Thus far, we do not have proof of the usability of our taxonomy across languages and across a larger variety of genres. Studying a wider variety of genres and languages may well result in more specific uses of endophoric demonstratives. Nevertheless, we expect analyses of other languages and other genres to fit in the classes we distinguished in Fig. 1, because in developing the taxonomy, a large variety of endophoric demonstratives from studies involving many different genres and languages were taken into account.

Although the present corpus analysis did not allow us to compare demonstratives with other types of referential expressions, many corpus distributions support the view of text-based demonstratives as giving access to relatively complex discourse referents, thus referents in need of an (ana)deictic device to be accessed properly. The proportion of anaphoric demonstratives with a non-nominal antecedent (41.1%), the huge proportion of abstract referents (78.6%), and the variety of (mostly distal) borderline cases points to demonstratives being devices flexibly creating complex referents on the basis of non-nominal, abstract, or vague antecedent information (e.g., Wittenberg, Momma, & Kaiser, Reference Wolter2021). Likewise, the relatively high proportion of modified demonstrative NP anaphors (25.1%), as in example (2) (compared to anaphoric definite NPs, e.g., Fraurud, Reference Fraurud1990; Vieira & Poesio, Reference Vieira and Poesio2000), supports the idea of demonstrative NPs often predicating new information about the referent (e.g., Cornish, Reference Cornish2001; Maes & Noordman, Reference Maes and Noordman1995).

The taxonomy introduced in this paper can be seen as a sound theoretical basis for future experimental or analytic work into endophoric demonstratives. In addition, it allows researchers to unify and compare the results of corpus studies on demonstratives coming from different genres and languages, and it can be used to compare and refine the analysis in studies in which demonstratives are seen as instrumental, for example, in assessing the quality of translations (e.g., Goethals, Reference Goethals2007) or the proficiency of learners of a (foreign) language (e.g., Blagoeva, Reference Blagoeva2004; Petch-Tyson, Reference Petch-Tyson, Botley and McEnery2000). Elsewhere, we have successfully used it to test hypotheses on demonstrative variance (this vs. that), and found that variance in English is not determined in the first place by the discourse-local activation status of discourse referents, but by discourse-global knowledge of genres, in particular, assumptions on subtle interactional inferences with respect to writer, addressee, and referent connected to specific discourse genres. Thus, we explained the dominance of distal vs. proximal demonstratives in the news vs. Wikipedia texts as a result of a reader- vs. writer-oriented interaction assumption connected to narrative vs. expository written texts, respectively (Maes et al., Reference Maes, Krahmer and Peetersin review).

Finally, we hope that our taxonomy will provide the theoretical and empirically supported foundation for a coherent and cooperative future research agenda focusing on the analysis of endophoric demonstratives in text.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank three anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions on an earlier draft of this work, and Thiago Castro Ferreira and Emiel van Miltenburg for help in the construction of the corpus.

Funding statement

D.P. was supported by a Veni grant (275-89-037) awarded by De Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO, the Dutch Research Council).