The Royal College of Psychiatrists has recently revised its report Safety for Trainees in Psychiatry (1999) replacing it with Safety for Psychiatrists (2006), to target all practising psychiatrists. But do consultants take safety measures as seriously as trainees? An electronic database search revealed no existing studies comparing attitudes of trainees with those of senior clinicians.

Safety has been a concern to junior psychiatrists for some time, with various audits and reports highlighting deficiencies (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1999; Reference Sipos, Balmer and TattanSipos et al, 2003). However, there has been little focus on more senior doctors. Consultants are often central to risk assessments and advise junior staff on complex management decisions for potentially violent patients.

Safety of National Health Service (NHS) staff is now recognised nationally as an important issue, for example the NHS Zero Tolerance campaign (Department of Health, 1999) and launch of a National Audit on Violence (2007). The chances of a violent incident occurring can be reduced by appropriate safety measures (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2006). We carried out our survey to investigate whether these suggested measures were being correctly implemented and to gauge staff attitudes towards them.

Method

We devised confidential questionnaires based on Royal College guidelines (2004, 2006) to survey safety awareness among junior and senior doctors in a teaching hospital and a district general hospital in East Anglia. The questionnaire covered all aspects of safety including training, interviewing, community assessments and incidents recorded. There were 38 questions in all, comprising forced yes/no responses, Likert scales for agreement or disagreement with statements on safety issues, and free text for comments (a copy of the questionnaire is available from the authors). An inspection of the interview rooms was also carried out to see whether they met with College standards.

We sent out postal questionnaires to all senior house officers (SHOs), specialist registrars (SpRs) and consultants working in general or old age psychiatry. This included SHOs working in other specialties but doing general psychiatry on-calls. We then emailed the questionnaires to any non-responders a month later.

Results

Of those surveyed, 29 of 32 SHOs, 11 out of 13 SpRs (85%) and 27 of 28 consultants (96%) returned their questionnaires. The overall response rate was 92%.

Training and interviews

Table 1 shows a summary of the survey's results relating to safety training, interviews with patients and community assessments.

Table 1. Survey results investigating safety training, interview and community assessment practices

| Senior House Officer (n=29) | Specialist Registrar (n=11) | Consultant (n=27) | Total (n=67) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | ||||

| Attended breakaway training | 26 (90%) | 8 (73%) | 6 (22%) | 40 (60%) |

| Attended in past year | 20 (69%) | 5 (45%) | 3 (11%) | 28 (42%) |

| Aware of breakaway course dates | 28 (97%) | 10 (91%) | 16 (59%) | 54 (81%) |

| Aware of local safety guidance | 24 (83%) | 4 (36%) | 8 (30%) | 36 (54%) |

| Interviews | ||||

| Inform staff of whereabouts | 25 (86%) | 10 (91%) | 21 (78%) | 56 (84%) |

| Work with staff during joint assessment | 11 (38%) | 10 (91%) | 27 (100%) | 48 (72%) |

| Carry personal alarms | 11 (38%) | 1 (9%) | 0 | 21 (31%) |

| Community assessments | ||||

| Aware of lone working policy | N/A | 5 (45%) | 19 (70%) | |

| Adhere to lone working policy | N/A | 1 (9%) | 11 (41%) | |

| Mobile phone provided | N/A | 10 (91%) | 23 (85%) |

Safety training for SHOs and SpRs was included as part of their induction. The main reason cited by consultants for not attending breakaway courses was that the training was too time-consuming. A second reason given was lack of evidence that it is effective, unless practised regularly. You can also see from Table 1 that while the majority of SHOs were aware of local safety guidance, only a third of SpRs and consultants were well informed.

Reasons for not wearing the personal alarms included forgetting it, losing it, inconvenience (no clip to attach to clothing), forgetting to charge it or check batteries, not being given one, and individual alarm systems for different wards so impractical to carry several. Consultants generally believed that staff were present on the wards when they were seeing patients and therefore felt that carrying alarms themselves was unnecessary. However, too few SHOs, compared with SpRs and consultants, appear to have staff accompany them for joint assessments.

Poor access to medical records was the main reason 90% of SHOs at the teaching hospital felt that they routinely did not have enough information on risk before they went to assess patients. On some sites these are not yet available electronically.

In the questionnaire we enquired about community assessments carried out by SpRs and consultants (Table 1). Many said that they did not follow lone working policies. Lack of knowledge of the policy and no regular person to inform of whereabouts were two reasons for this and SpRs felt they were always doing joint assessments out of hours, making the policy unnecessary.

Environment

In addition to sending out questionnaires we inspected the psychiatric ward interview rooms used by the SHOs, SpRs and consultants on the main psychiatric hospital site.

The results (Table 2) show the flaws noted with the interview rooms. Those on the ward were isolated, small and the doors opened inwards. The room in Accident and Emergency (A&E) was better, but still small with the door opening inwards. Potential weapons were reported by SHOs in 81% of interview rooms (including in A&E). These included snooker cues, darts, knitting needles, brass plates, mugs and potted plants. None of the panic buttons (including those in A&E) were felt to be easily accessible.

Table 2. Results of interview rooms inspection

| Psychiatric ward interview rooms (n=12) | A&E interview room | |

|---|---|---|

| Panic buttons | 2 (13%) | Yes |

| Isolated | 7 (62%) | Yes |

| Free of clutter | 4 (31%) | Yes |

| Inspection window present | 10 (87%) | Yes |

| Not lockable from inside | 10 (81%) | Yes |

| Adequate room size > 12 m2 | 1 (12%) | No |

| Door opens outwards | 2 (19%) | No |

Incidents

In the 6 months prior to the survey, 55% of the SHOs had felt sufficiently threatened by a patient that they decided to terminate the interview. Similarly 64% of the SpRs and 52% of the consultants remembered feeling threatened by a patient or their relatives. One SpR and two consultants had been physically assaulted. While the physical assaults were reported, the staff were generally reluctant to report verbal incidents or acts of aggression that had not resulted in injury. A third of the SHOs routinely report incidents compared with 18% of SpRs and only 11% of consultants who fill in incident forms.

Perception of safety: qualitative data

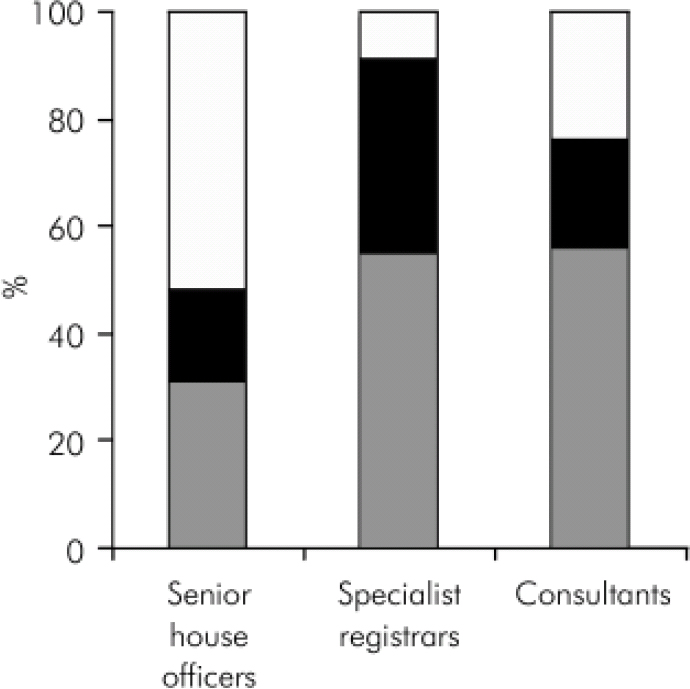

All participants were asked for their views on the statement ‘There are reasonable measures to ensure my safety at work’ (Fig. 1). The majority of SHOs disagreed with this statement, in contrast to the views of the SpRs and consultants.

The main comments from SHOs regarding safety related to environment (interview rooms were not up to standard; on-call accommodation was isolated). Several commented that there was a ‘lack of safety culture’. Concerns voiced by SHOs and SpRs included similar themes about environment (‘Lack of electronic medical notes, which leads to incomplete risk assessments’) as well as about safety in a wider context: ‘Verbal abuse is often not taken seriously’; ‘Verbal abuse seen as part of the job’; ‘Blame can be attached to untoward incidents’. In contrast, consultants replies tended to minimise issues: ‘I’m only a locum’; ‘I’ve covered up my inspection window as it's my office too’; ‘I work with the milder end of the spectrum’; ‘I avoid risky situations’.

Fig. 1.

Participants’ responses to statement: ‘There are reasonable measures to ensure my safety at work’ - □, disagree; ▪, not sure; ![]() , agree.

, agree.

Conclusions

The trainees surveyed gave safety issues more consideration overall than consultants. This may be because safety is incorporated into their training on a regular basis. At work SHOs generally feel less safe than consultants who tend to have more positive perceptions of their own safety. Reasons for this may include greater experience in risk assessments, less exposure (in particular in A&E departments, at night and of patients new to the service), fewer delays in accessing staff for joint assessments, and lack of prioritising safety training compared with junior staff. However, this survey shows that consultants do still feel threatened at work and are sometimes assaulted. As such, it is important that they are aware of their own personal safety and the safety policy of their employing trust (something about which many were unclear). Clear mechanisms for cascading information on policies and policy alterations to staff are needed.

Breakaway training is generally well attended by junior staff but not senior, who see the training as time-consuming and the techniques taught unlikely to be useful, especially given the relatively low frequency of serious incidents for most clinicians. There is no research evidence on the effectiveness of such training for psychiatrists; some argue that learning breakaway techniques engenders recklessness.

We can speculate as to why many SHOs do not feel that there are reasonable measures to ensure their safety, unlike most consultants and SpRs. They do more emergency and urgent assessments (sometimes, it seems, alone); are less experienced in psychiatry, though perhaps better trained in safety issues; and may work in different areas resulting in unfamiliarity with each set of safety procedures.

While the employing trust clearly has some responsibilities to ensure safety, such as providing adequate interview rooms, it is the individual's responsibility to check that safety measures would work in an emergency. It was striking that many staff were unaware whether or not existing panic buttons worked or the nature of expected response to a panic alarm. Very few doctors wear personal alarms, usually by their own choice, but sometimes because of insufficient alarm units or problems in using different alarms when covering multiple wards/sites. This is unacceptable for staff, even where joint assessments are the norm.

This survey demonstrated an overall reluctance to report verbal abuse, with some staff seeing it as ‘part of the job’, and with senior staff least likely to report incidents. This could be adding to the SHOs perceived ‘lack of safety culture’ at work.

Safety is important; a joint responsibility between individuals and employers. The use of a questionnaire such as this one could be useful in auditing safety standards at work. The College also has a role in addressing these issues within the approval visit system, and ensuring that safety is not forgotten, following changes under the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.