Introduction

Who has the power of implementing policies in the European Union (EU)? Answering this question is harder than it may seem at first sight. Along the past three decades, known as the “post-Maastricht” era, the EU system of governance has become essentially more complex and “multilevel” (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2001, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003; Scharpf Reference Scharpf1997). While the EU legislative power is divided between the Commission (who initiates the legislation), the Council and the European Parliament (who negotiate the laws proposed by the Commission), laws are subsequently implemented at different levels and by different actors. They include national (public administration and independent regulatory authorities), supranational (the European Commission) “networked” (Levi-Faur Reference Levi-Faur2011) and “de novo” (Bickerton et al. Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015) bodies (e.g. over 34 EU decentralised agencies and other institutions such as the European External Action Service and the European Stability Mechanism).Footnote 1

The existence of different kinds of policy implementers in the EU opens puzzling questions including, on the one hand, why EU legislators select more or less supranational actors to implement policies (Delreux and Adriaensen Reference Delreux and Adriaensen2018, p. 265). On the other, it leads to ask what determines the different degrees of executive leeway these actors enjoy vis-à-vis each other. Although, since the early 2000s, several scholars have sought to disentangle the dynamics underlying these phenomena, the rapidly evolving EU governance system makes this an increasingly intricate exercise.

With this article I employ a principal–agent (PA) framework to address the politics of executive delegation in the post-Maastricht era by addressing two main issues, that is, (a) what determines the choice of opting for delegation to national administrations, to the European Commission, EU agencies, or a combination of these actors and (b) what determines the degree of discretion enjoyed by the supranational level vis-à-vis the national one. By so doing, I contribute to the literature on EU public policy by providing an empirical overview of the distribution of implementation competences delegated in EU legislation without limiting it to the traditional Commission–national dichotomy but also grasping variation in between.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. After a review of the state of the art on PA applied to the EU context, I outline the main PA relationships identifiable within the EU legislative process. I then specify five hypotheses accounting for different implementation choices and different degrees of discretion granted to implementers. I test my framework through ordered logistic and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses. My findings show that decision rules and policy complexity favour the involvement of supranational actors (both agencies and the Commission) in the implementation of EU laws. Moreover, when codecision applies, the degree of supranational integration of a policy is associated with the likelihood of choosing supranational implementation in a curvilinear way. Regarding the agents’ discretion, I find that the Commission enjoys higher discretion vis-à-vis national actors when qualified majority voting (QMV) applies, and when higher levels of conflict in the Council of Ministers are present.

The PA framework: an overview

According to the PA framework (for early work see Calvert et al. Reference Calvert, McCubbins and Weingast1989; Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1994; McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; McCubbins and Sullivan Reference McCubbins and Sullivan1987; Volden Reference Volden2002), executive delegation occurs when legislators (the “principals”) decide to give up a share of their responsibility to policy executors (the “agents”) in order to implement policies. Political principals are willing to delegate executive tasks in order to reduce transaction costs (Pollack Reference Pollack1997) and overcome thorny issues such as the lack of policy efficiency and credible commitments (Majone Reference Majone1997, Reference Majone2001; Thatcher Reference Thatcher2002, Reference Thatcher2011; Yesilkagit and Christensen Reference Yesilkagit and Christensen2010). In spite of the benefits of delegation, this action may produce agency losses from “shirking” due to diverging preferences between principals and agents and information asymmetries (Kiewiet and McCubbins Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Pollack Reference Pollack2003, 26–27; Thatcher Reference Thatcher2011). Delegation, in fact, entails by definition, a risk of the principals to lose control over their agents, who in turn may defect and pursue their own agendas (agency drift, or slack), or simply fail to produce outcomes as good as if the principal had been in charge (agency loss). In order to minimise costs, therefore, delegation of any kind of authority must be accompanied by control mechanisms (Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1994). For this reason, the PA framework is not limited to theorising the act of delegation but also outlines the dynamics underlying the agents’ discretion, that is, “the leeway conferred to an agent to accomplish a delegation mandate” (da Conceição-Heldt Reference da Conceição-Heldt, Delreux and Adriaensen2017, p. 204). Political principals can exert control ex ante by limiting the flexibility of the agents’ actions (da Conceição Reference da Conceição2010; McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; McCubbins et al. Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1989) and by imposing procedural constraints within the legislation (Franchino Reference Franchino2007).

The EU is a prolific testing ground for the PA approach as the process of EU integration has involved a remarkable transfer of tasks from the EU legislative bodies to both national and supranational executors in comparison to traditional international organisations (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2015). Yet, being a system of “multi-level governance” (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2001, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003; Scharpf Reference Scharpf1997), the EU displays multiple chains of delegation (Bergman Reference Bergman2000; Curtin Reference Curtin2009; Nielson and Tierney Reference Nielson and Tierney2003) through which different legislative bodies delegate executive tasks to multiple actors. These features make, on the one hand, the PA framework a valuable “toolkit”, helpful to disentangle several questions related to the distribution of power and competences in the EU (Delreux and Adriaensen Reference Delreux and Adriaensen2018; Egan et al. Reference Egan2017). On the other, they constrain the applicability of the model as the individuation of delegation relations may be harder than in the presence of less actors in the institutional landscape (Delreux and Adriaensen Reference Delreux, Adriaensen, Delreux and Adriaensen2017, Reference Delreux and Adriaensen2018; Kassim and Menon Reference Kassim and Menon2003). In spite of these limitations, research applying PA to the EU is vast. Several scholars have focused on delegation to traditional supranational institutions such as the European Commission (Franchino Reference Franchino2002, 2007) and the European Court of Justice (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002) but also on member states’ relations with other institutions such as the Council Presidency or the European Central Bank (Elgie Reference Elgie2002; Thatcher and Sweet Reference Thatcher and Sweet2002). Scholars have also sought to focus on inter-institutional interaction between the European Council and the Council of the European Union (Kroll Reference Kroll, Delreux and Adriaensen2017), on delegation to scientific committees (Dunlop and James Reference Dunlop and James2007) and to comitology committees (Moury and Héritier Reference Moury and Héritier2012). Moreover, PA has been applied to specific policy areas such as negotiations in trade (Gastinger and Adriaensen Reference Gastinger and Adriaensen2019; Kerremans Reference Kerremans2004) and environmental policies (Delreux Reference Delreux2009).

As far as the process of delegation in EU secondary laws is concerned, the first theoretical and empirical attempt to assess it on a relatively large sample is Franchino’s seminal work, “The powers of the Union” (2007). Thomson and Torenvlied (Reference Thomson and Torenvlied2011) provided a similar contribution, concentrating on the period between 2000 and 2005. Ershova (Reference Ershova2019), in turn, analysed delegation to the European Commission during Barroso II and Junker’s leaderships, while Migliorati (Reference Migliorati2019) tackled delegation to EU agencies between the mid-1980s and 2016.

Against the background just overviewed, a contribution providing an encompassing picture of delegation to supranational actors and the discretion they enjoy across policy area in the post-Maastricht era is still missing.

An empirical mapping of delegation paths and agents’ discretion in EU secondary law

According to Delreux and Adriaensen, the PA approach is useful in the EU context to carry out three main tasks, that is, “mapping principal–agent relations; studying the politics of delegation; and studying the politics of discretion” (2017, p. 14). In this section, I draw the main PA relationships that are empirically identifiable in EU secondary law on the basis of a pre-existing data set covering the period between 1985 and 2016 (Migliorati Reference Migliorati2019). After that, on the basis of the same data, I measure the degree of discretion granted to national and supranational agents.

To proceed with the empirical analysis, some premises are necessary. First of all, investigating delegation in secondary legislation is less straightforward than in primary law. While treaties limit to set general competences and decision rules through inter-state bargaining, secondary law is much more fine-grained and involves different decision-making rules. Legislation can be adopted either by the Council alone or jointly by the Council and the European Parliament under a proposal of the Commission. Laws can be adopted by unanimity or QMV (in the Council), depending on the procedure. With the Lisbon Treaty (2009), codecision became the EU’s “ordinary legislative procedure” (OLP) making most of legislative files subject to QMV. There are still several exceptions including taxation, social security, the accession of new countries to the EU, foreign and common defence policy and operational police cooperation between EU countries, which are still voted by unanimity. When the Council legislates by itself, it is the only legislative body able to make delegation choices and therefore the only actual principal. Conversely, when the European Parliament and the Council legislate together under codecision, they represent a “collective principal” (Delreux and Adriaensen Reference Delreux, Adriaensen, Delreux and Adriaensen2017; Nielson and Tierney Reference Nielson and Tierney2003).

When (the) principal(s) decide(s) to delegate to national and/or supranational actors, this constitutes “an active choice between alternative governance structures” (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002, p. 25). Implementation tasks may be left in the hands of national administrations or, conversely, be delegated entirely to the supranational level by employing the European Commission as the sole policy executor. Moreover, legislators may opt for an implementation path based on the relative reliance on these types of bureaucratic actors (Franchino Reference Franchino2007, p. 20), in which tasks are shared among the Commission and national administrations. Finally, legislators can also opt for an intermediate degree of supra-nationalisation by relying on the help of EU decentralised agencies (Busuioc and Groenleer Reference Busuioc and Groenleer2013; Chiti Reference Chiti2004; Egeberg and Trondal Reference Egeberg and Trondal2017; Levi-Faur Reference Levi-Faur2011; Majone Reference Majone1994) that broadly represent a second-best design choice to further delegation to the Commission (Kelemen and Tarrant Reference Kelemen and Tarrant2011), and other de novo bodies (Bickerton et al. Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015; Fabbrini and Puetter Reference Fabbrini and Puetter2016). In the case of agencies, according to a “double-delegation” logic (Eberlein and Grande Reference Eberlein and Grande2005; Michaelowa et al. Reference Michaelowa, Reinsberg and Schneider2018), the Commission may be considered a principal too, given that agencies are often treated as an expansion of the EU administrative apparatus (Egeberg and Trondal Reference Egeberg and Trondal2017).Footnote 2

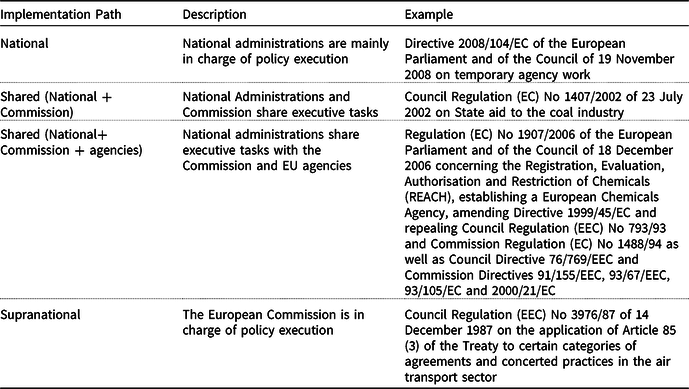

Examples of the four detected paths are provided in Table 1: for instance, legislation on temporary agency work leaves implementation in the hands of national administrations, while competition in the air transport sector is entirely delegated to the Commission. Since 2006, regulation of chemical products in the Union is shared between the Commission, national regulatory authorities and the European Chemicals Agency.

Table 1. Examples of implementation paths

The coding of delegation consists of a textual analysis performed following Franchino’s approach (Reference Dunlop and James2007). The method has been used by other authors including Ershova (Reference Ershova2019), Pollack (Reference Pollack2003), Thomson and Torenvlied (Reference Thomson and Torenvlied2011), and Epstein and O’Halloran (Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999). Once identified provisions within the legislative text, I code whether legislative provisions delegate implementation powers to national administrations and the Commission. For example, provisions specifying that member states may, or are entitled to, take some action, or that they are exempted from certain aspects of the law, delegate to national administrations. Conversely, acts letting the Commission adopt decisions, set guidelines and standards, request actions, or authorise action of other actors, delegate to the Commission.

Finally, if an agency is included in the act for the purpose of policy implementation, delegation to agencies is coded as present. Other de novo bodies are excluded from coding as they are either absent (e.g. the European External Action Service) or present only in a small number of cases (e.g. the European Central Bank).Footnote 3

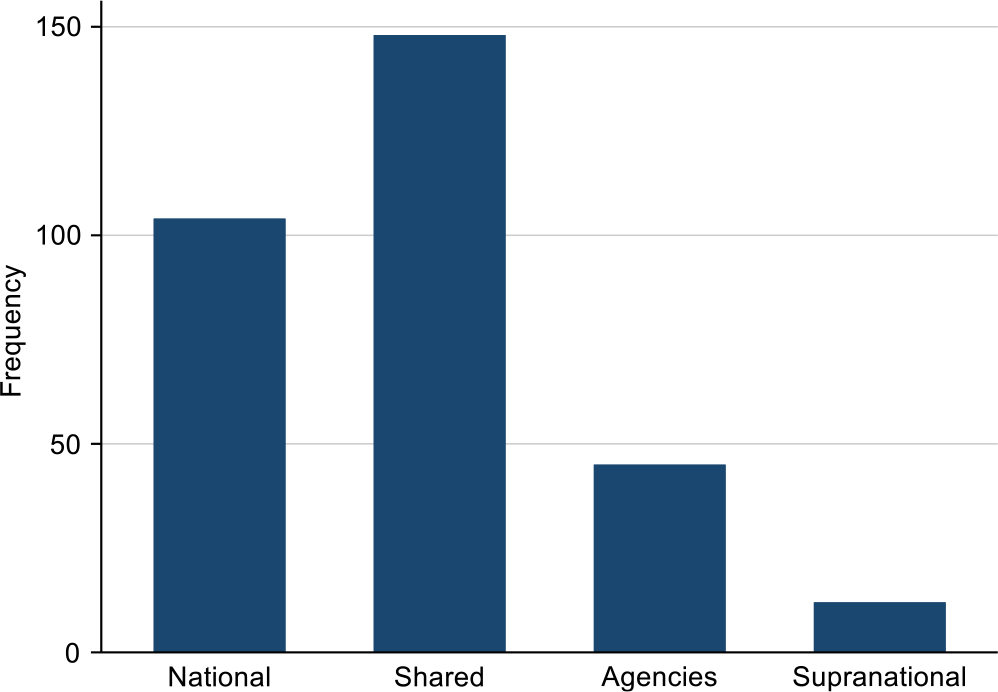

Completely, national delegation is present when only national delegation is higher than 0. The first degree of shared delegation occurs when both national and Commission delegation are higher than 0, but no agency is involved. The second degree of shared path occurs when both Commission and national delegation are higher than 0, and an agency is involved in implementation. Finally, the path is supranational when national delegation is equal to 0 and the Commission delegation ratio is higher than 0. The bar chart in Figure 1 shows the frequency of each category present in the data set. Shared powers by Commission and national administration are the most frequent one, followed by the fully national path. The third (agencies involvement) and fourth paths are less frequent. Table 2, in turn, shows the share of each category within the broad policy categories (Leuffen et al. Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2013).

Figure 1. Implementation paths in the dataset.

Table 2. Implementation paths and policy areas

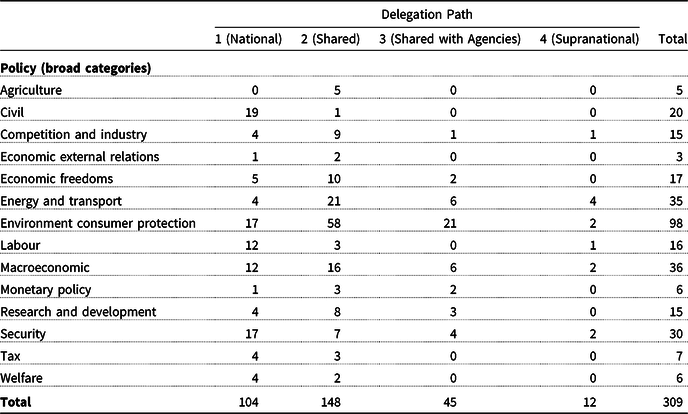

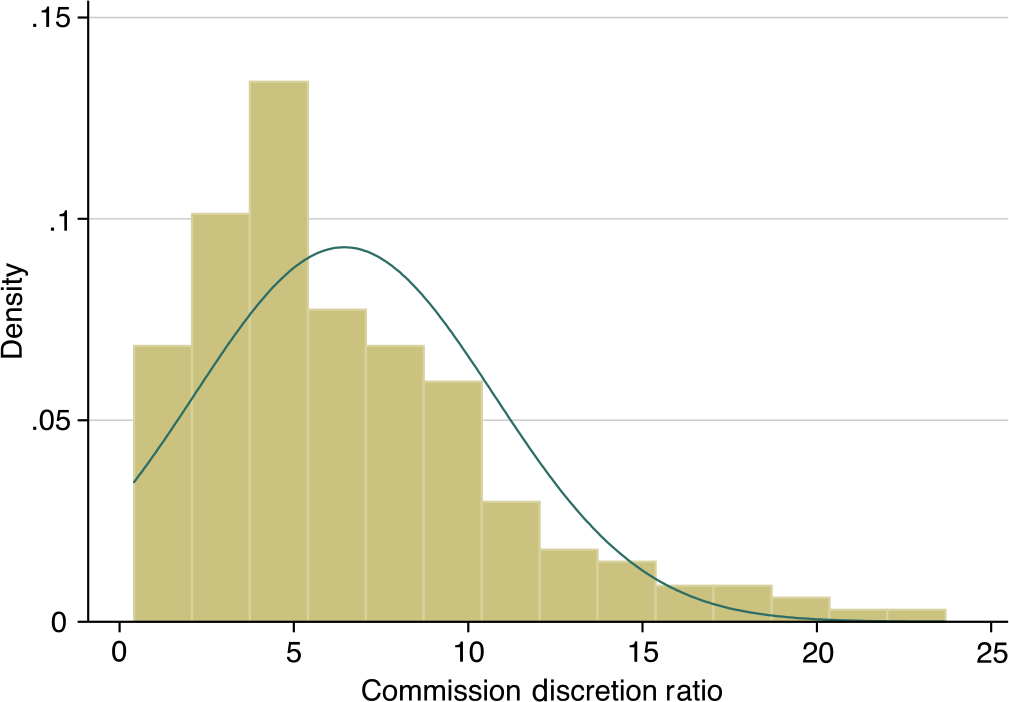

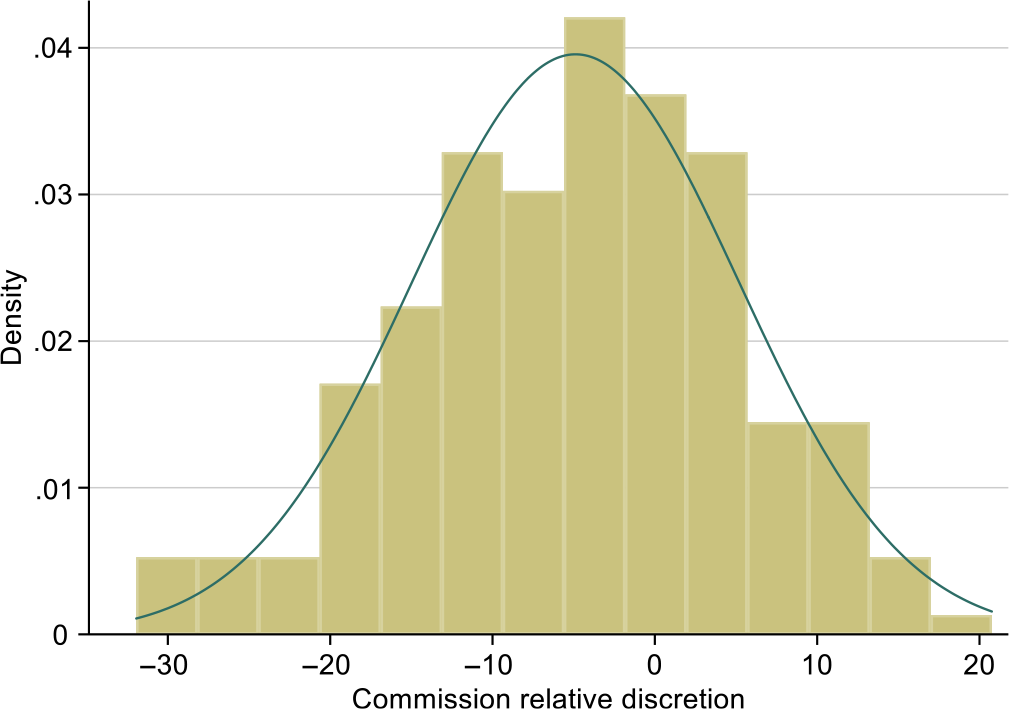

And yet, the choice of delegation is just half the story. As noted before, the concept of delegation goes hand in hand with the degree of discretion granted to the executors. Indeed, delegation is usually accompanied by the establishment of several control mechanisms so as to prevent agency losses (Gastinger and Adriaensen Reference Gastinger and Adriaensen2019). Hence, even if supranational actors are indeed involved in the implementation process, they may be substantially more constrained than national ones. The degree of national administrations’ and the Commission’s discretion is obtained by weighting the delegating provisions by the constraints imposed on implementers (measurement details for constraints in the Appendix).Footnote 4 Histograms in Figures 2 and 3 show, respectively, the distribution of national and supranational (Commission) discretion. In 30 cases of 309, national discretion is equal to 0, while in 107 cases of 309, the Commission’s discretion is equal to 0. The two graphs show that national discretion is, overall, comparatively twice as high as the Commission’s, and that both distributions are skewed towards 0.

Figure 2. Distribution of national discretion ratio.

Figure 3. Distribution of Commission’s discretion ratio.

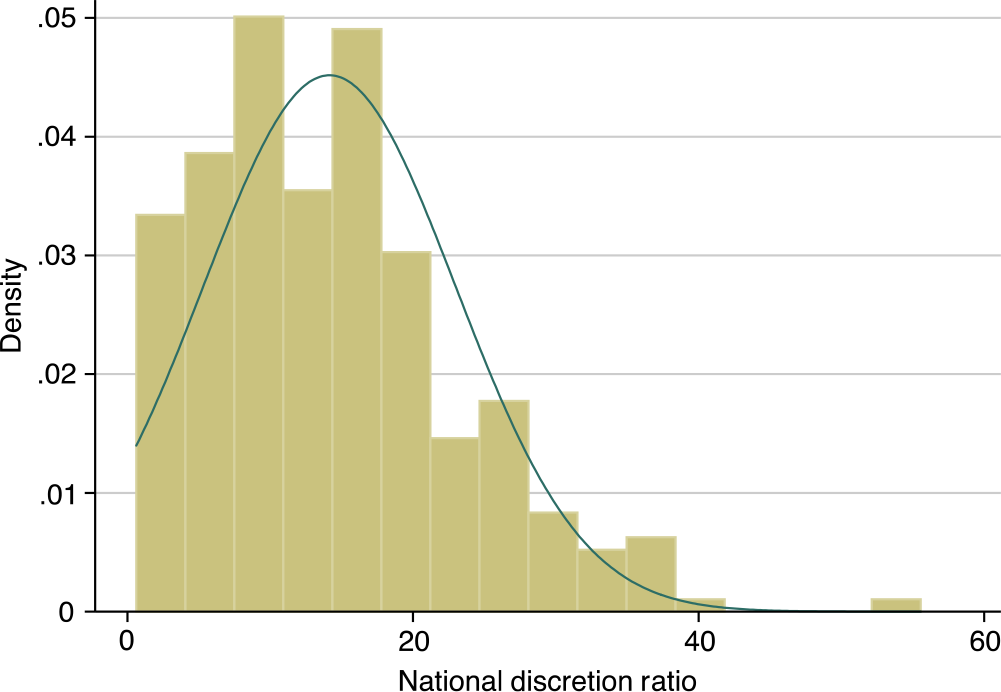

In order to collapse the two ratios into a single measurement, I compute the relative discretion between the Commission and the national administrations, that is, the extent to which the Commission enjoys executive leeway vis-à-vis national administrations. I do this by calculating the difference between the Commission discretion ratio and the national discretion ratio (Franchino Reference Franchino2007), shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Distribution of Commission’s relative discretion.

The empirical evidence just overviewed confirms the existence of a strong variation among both implementation paths and discretion levels. In the next section, I draw five hypotheses accounting for the differences just outlined.

Determinants of delegation paths

Decision rules

I hypothesise that the first factor affecting the likelihood of involving the supranational level in policy implementation is linked to the utilisation of QMV in the Council of Ministers, regardless of the involvement of the European Parliament. Pooling, that is the choice of states to “transfer the authority to make binding decisions from themselves to a collective body of states within which they may exercise more or less influence” (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2015, p. 308), supposedly affects delegation choices because it “not only makes the formal decision-making of any single government more dependent on the votes of its foreign counterparts, but also more dependent on agenda-setting by the Commission” (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik1993, p. 509). According to Franchino, delegation of executive tasks to the Commission by the Council is more likely under QMV than unanimity, because the Commission can take advantage of different preferences in the Council and make winning proposals that delegate more powers to the supranational executive and restrain further national administrative autonomy. In addition, pivotal ministers in majority voting are likely to have more moderate preferences and they are also likely to prefer lower national executive discretion and/or delegation to the Commission (Franchino Reference Franchino2007, p. 22). In sum, the Commission should have more leverage under QMV as it has to convince less (and less hostile) actors in order to obtain a policy closer to its preferences, that is, delegating to itself or, as a second choice, to EU decentralised agencies (Kelemen and Tarrant Reference Kelemen and Tarrant2011). It follows that it should be more likely to observe a higher frequency of delegation to supranational actors under qualified majority than under unanimity.

H1: QMV increases the probability of delegation to the supranational level.

Policy complexity

The second argument accounting for the selection of a more supranational path derives from a functional logic connected, on the one hand, to principals’ transaction cost calculations and, on the other, to the multi-level structure of EU governance. Several scholars have underlined that poorly informed politicians tend to rely more on the expertise of implementers (Epstein and O’ Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999; Elgie and McMenamin Reference Elgie and McMenamin2005; Majone Reference Majone2001; Thatcher Reference Thatcher2002; Wonka and Rittberger Reference Wonka and Rittberger2010). It is sensible for a legislator to delegate the burden of implementing policies requiring high levels of expertise, especially if implementers are better informed about the effects of European policies than are policymakers themselves. On top of that, with the emergence of a multi-level system characterised by high interdependence and dialogue across different governance levels, it has been observed how the EU tends to increasingly rely on network structures (Levi-Faur Reference Levi-Faur2011) orchestrated by the Commission (Blauberger and Rittberger Reference Blauberger and Rittberger2015; Migliorati Reference Migliorati2017) and facilitating best practices and diffuse expertise, and on EU-level agencies to deal with complex policy issues (Migliorati Reference Migliorati2019; Wonka and Rittberger Reference Wonka and Rittberger2010). This evidence suggests that the post-Maastricht scenario is increasingly characterised by the need to rely not only on national implementers, but also on supranational ones, when issues become more complex and encompass multiple policy dimensions. Being a functional logic of delegation based on the need of principals to acquire as much expertise as possible, it should apply both when the European Parliament is involved and when it is not.

H2: Higher policy complexity increases the probability to rely on multiple levels of governance and, therefore, on supranational implementers

Supranational integration

Tallberg (Reference Tallberg2002) maintains that delegation dynamics in the EU present “feed-back loops”. According to this view, future delegation choices are affected by previous ones (see also Thatcher Reference Thatcher2011). Given that supranational institutions have been increasingly granted competences through the EU treaties (Börzel Reference Börzel2005; Leuffen et al. Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2013), it is reasonable to expect secondary law to be more likely to grant more implementation tasks to supranational actors when integration at the supranational level is higher. Ripoll Servent argues that in the EU, “power is usually not delegated horizontally but vertically” (Ripoll Servent Reference Ripoll Servent2018, p. 5). This implies that delegating tasks to the Commission and to agencies is often preceded by a transfer of competences to the EU level.

However, there are reasons to expect that such an upward trend may be interrupted by a countervailing mechanism specific to the post-Maastricht era: Bickerton et al. (Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015) and Fabbrini and Puetter (Reference Fabbrini and Puetter2016) argue that since the early 1990s, the EU has witnessed a process of “integration without supranationalisation” characterised by the reluctance of EU member states to further delegate tasks to the supranational level beyond a certain level. Cases in point are the area of justice and home affairs (Maricut Reference Maricut2016) and energy policies (Thaler Reference Thaler2016).

Against this background, I argue that the degree to which a policy is integrated at the EU level should be associated with an increasing probability of involving supranational actors in subsequent processes of policy implementation. The probability may start declining after a certain threshold, due to the reluctance of member states to delegate further competences to supranational actors. As the European Parliament is generally assumed to prefer delegation to EU actors (Kelemen and Tarrant Reference Kelemen and Tarrant2011), it may be the case that legislation adopted under codecision has a stronger positive effect on delegation to the supranational level than laws adopted by the Council alone.

H3: the higher the degree of supranational integration and competence transfer to the supranational level, the more likely the involvement of more supranational actors in policy implementation. However, the trend should invert for high levels of integration producing a curvilinear development.

Determinants of varying discretion levels: decision rules and conflict

Extensive research has been conducted to assess the factors that trigger principals’ control and, consequently, affect agents’ discretion. Research along these lines focuses especially on the effects of decision rules (Franchino Reference Franchino2007; Thomson and Torenvlied Reference Thomson and Torenvlied2011) and the preference heterogeneity among principals (da Conceição Reference da Conceição2010; da Conceição-Heldt Reference da Conceição-Heldt, Delreux and Adriaensen2017; Elsig Reference Elsig2010; Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1994; Franchino Reference Franchino2007; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Lake, Nielson and Tierney2006; Martin Reference Martin2006; Schneider and Tobin Reference Schneider and Tobin2013). On the basis of this literature, I draw two main expectations.

First of all, by essentially the same mechanism described in the previous theoretical section, as much as QMV allegedly affects the choice of the implementation path, it should also be able to facilitate higher discretion levels granted to the supranational level.

H4: QMV grants relatively higher discretion to the Commission than to national administrations.

Second, according to previous literature, one of the most important factors shaping agents’ discretion seems to be the preference heterogeneity between principals. Back in the 1990s, Epstein and O’ Halloran (Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1999) were the first to show that with divided governments, the Congress gives up more executive discretion to independent regulatory agencies, rather than to bureaucratic departments. By a similar token, Franchino (Reference Franchino2007) showed how the relative discretion granted to the Commission compared to national administrations increases as the conflict among Council members increases; and, more recently, da Conceição (Reference da Conceição2010) and Elsig (Reference Elsig2010) proved empirically that the preference heterogeneity of the principals increases the agents’ discretion.

The underlying argument linking conflict to discretion is that, in the presence of conflict, principals would rather grant higher discretion in policy implementation to a more impartial supranational executor, that is, the Commission, instead of risking to incur in losses provoked by other states’ implementation deficits (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002, p. 25). In additional support to this view, a commitment component exists: for example, when conflict among Council members is high, member states’ governments are more likely to face commitment problems, because preference divergence makes the strength of their policy commitments much looser (Thomson and Torenvlied Reference Thomson and Torenvlied2011). The act of self-commitment, in sum, “is only meaningful to the extent that supranational agents enjoy extensive discretion in the execution of their functions and do not face the immediate threat of having their decisions overturned by government principals” (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002, p. 29). In presence of conflict, delegation of higher discretion to the Commission would be, therefore, preferable rather than national administrations, because it protects states from each others’ defections and ensures the credibility of the commitments taken.

The mechanisms just overviewed relate mainly to a situation in which the Council is the only principal. When it comes to dealing with the role of the European Parliament, there are very few contributions available. According to recent work by Conceição-Heldt (Reference da Conceição-Heldt, Delreux and Adriaensen2017), preference homogeneity between states and the Parliament in trade policy results in lower discretion to the Commission, as more cohesive principals are more successful in presenting a unified front vis-à-vis their agent.

Against this background, I draw a general hypothesis on the relationship between conflict and discretion:

H5: The higher the preference heterogeneity of principals, the higher the discretion granted to the supranational level.

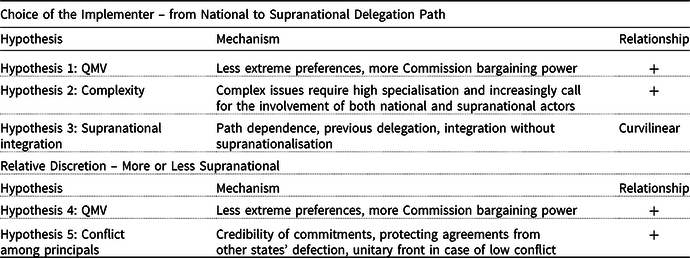

Table 3 summarises the hypotheses outlined so far.

Table 3. Summary of main hypotheses and mechanisms

Measurement (independent variables)Footnote 5

Complexity

The operationalisation of policy complexity is notably cumbersome. As far as EU legislative studies are concerned, a number of scholars (Franchino Reference Franchino2002, 2007; Kaeding Reference Kaeding2006; Migliorati Reference Migliorati2019; Rasmussen and Reh Reference Rasmussen and Reh2013; Thomson and Torenvlied Reference Thomson and Torenvlied2011) have employed the number of recitals included in the legislative acts.Footnote 6 A large number of recitals indicate that the directive has an extensive scope as well as addressing a high number of important issues and the overall more complex policy areas (Toshkov Reference Toshkov2008). Although such measurement may also hint at the scope of a proposal, its salience and/or controversy (Ershova Reference Ershova2019; Warntjen Reference Warntjen2012), given the widespread use of recitals as a proxy of complexity, I assume a good degree of reliability for this measurement. Yet, to better grasp the multi-dimensionality of a policy, I also employ the number of definitions included by the EuroVoc dictionary in the Eurlex database. EuroVoc is a multilingual, multidisciplinary thesaurus covering the activities of the EU. For example, Directive 2009/73/EC of 13 July 2009, concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas includes 10 different terms ranging from consumer protection to gas supply, while Directive 2008/48/EC on credit agreements for consumers has only 4 terms. By measuring the amount of specific terms associated with each legislative act, this variable should be able to grasp not only the absolute complexity of the act but also the amount of policy dimensions it encompasses.

Conflict

Several scholars have argued that the EU policy space is multi-dimensional (see Hix and Høyland Reference Hix and Høyland2011). The three most important ones acknowledged by the literature are the integration dimension, the left-right dimension and the policy dimension. Some studies have considered all of them (e.g. Franchino Reference Franchino2007), while others, such as Crombez and Hix (Reference Crombez and Hix2015), simplify the multi-dimensionality argument and employ just the left-right dimension, arguing that it is reasonable to assume that politicians’ preferences on EU policies are influenced by their underlying left-right preferences and by their actual policy preferences (Crombez and Hix Reference Crombez and Hix2015). In order to make the analysis as encompassing as possible, I employ both the left-right and the integration dimensions. I calculated the left-right position of each government drawn from the Parlgov data set (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2012) at the time of legislative adoption, by weighting the left-right score of each party sitting in the government by the share of seats it holds in the national parliament. I then measured the right-left range among Council member governments by calculating the absolute difference between the extreme right and the extreme left government position in the Council (under unanimity rule), and the absolute difference between the right and left pivots (under QMV), at the time of adoption. In a one-dimensional setting, there are two pivotal states, one for the leftward move (the most left-wing member among the right-wing) and one for the rightward move (the most right-wing member among the left-wing ones. To identify, respectively, the right and left pivots, I employ the codebook of the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) in order to match policy categories and corresponding leftward and rightward shifts. I apply a matching similar to Franchino (Reference Franchino2007) and Ershova (Reference Ershova2019). For example, I match the “Water framework directive”, which aims at the prevention of water pollution, with the category “Environmental Protection”, which is recognised as being a priority for left-wing parties. In this case, therefore, more environmental protection implies a leftward shift: The pivotal actor in this instance was Belgium. I followed a similar procedure to calculate conflict along the integration dimension through the Parlgov data set. Assuming that passing EU legislation generally implies a shift towards higher integration, the integration pivot is the least integrationist among the pro-integration Council members. Using the Parlgov data set, I also calculate the position of the European Parliament following Crombez and Hix (Reference Crombez and Hix2015), thereby taking the score of the left-right and integration position of the median European Parliament (EP) group at each time of adoption. I then obtain the absolute value of the difference between the median EP (across integration and left-right dimensions) and the Council pivot.

Decision rules

I created a dichotomous variable taking the value of 1 when qualified majority applies (QMV) and 0 for unanimity (U). The majority (85%) of legislation in the sample is adopted by QMV. The rest (15 %) is adopted by unanimity.

Supranational integration

The balance of policy authority between the EU and the national levels has primarily been investigated through case studies, focusing on individual treaty effects or the effects of secondary legislation (Featherstone and Radaelli Reference Featherstone and Radaelli2003; Saurugger and Radaelli Reference Saurugger and Radaelli2008). Moreover, Börzel (Reference Börzel2005) has mapped policy integration in the EU, considering the level and scope of integration; while Hix and Høyland (Reference Hix and Høyland2011) show how different treaties have modified the competences and the decision-making process in the EU. Finally, Leuffen et al. (Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2013) calculated the evolution of formal, treaty-based authority over time in different fields of EU governance which, in turn, builds on Lindberg (Reference Lindberg1970) and Börzel’s breadth and depth conceptualisation (2005). They distinguish between levels of authority ranging from 0 to 5 and including the following dimensions: No coordination at the EU level. Unanimous intergovernmental coordination without the involvement of supranational institutions; unanimous intergovernmental cooperation with limited involvement of supranational institutions; joint decisionmaking by majority with limited involvement of the EP; joint decisionmaking by majority with EP involvement and supranational centralisation. Given that this is the most recent policy-specific measurement of integration collapsed into one single dimension, I employ this measurement for my analysis.

Controls

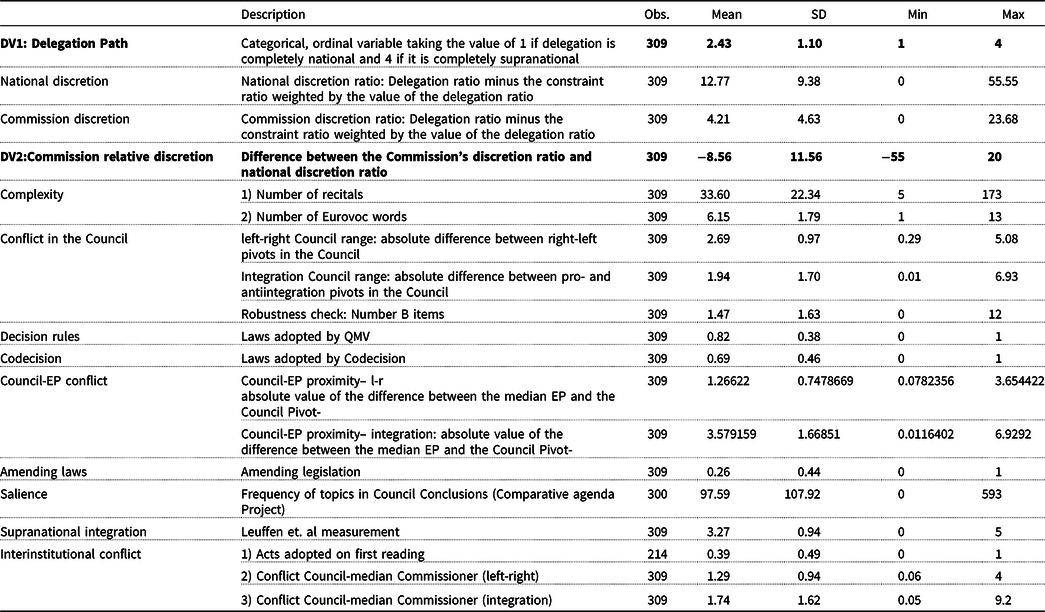

Contrary to Thomson and Torenvlied (Reference Thomson and Torenvlied2011), I do not include a control variable differentiating directives from regulations. The relationship between executive discretion and type of legislative act is typically endogenous: regulations are directly applicable to national jurisdictions, while directives require the adoption of new legislation at the national level. Given that regulations are implemented at the supranational level, the Commission is by definition typically more constrained by the legislators, while directives are implemented at the national level, which implies that more detailed constraints are not necessary. I opted, instead, to control for acts which amend from those which introduce completely new laws, because when a provision is completely new, the impact of the Council’s preferences should be higher as the implementers’ discretion starts from 0, while in the case of amending acts, we start from a different status quo in which the Commission and national administrations may already have some leeway secured by previous acts. I control for treaty fixed effects as there might be systematic changes associated with the adoption of a new treaty, and I distinguish between policies dealing with economic and social regulation (Wonka and Rittberger Reference Wonka and Rittberger2010). Finally, I control for policy salience through the Comparative Agenda Project Council Conclusions (Wilkerson et al. Reference Wilkerson, Baumgartner, Brouard, Chaqués, Green-Pedersen, Grossman, Jones, Timmermans and Walgrave2009), as the literature presents contradicting expectations in this regard. According to Rittberger et al. (Reference Rittberger, Schwarzenbeck and Zangl2017), major media outlets tend to frame political responsibility for policy failures against the actor which is in charge of the implementation of a policy. Considering the increasing politicisation of EU integration (Hartlapp et al. Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Rauh Reference Rauh2019), it may be the case that the logics of delegation themselves in the EU are influenced by this pattern: in particular, the unpopularity of certain policy decisions may result in higher levels of discretion to the Commission or to EU agencies. A countervailing logic supported by Calvert et al., (Reference Calvert, McCubbins and Weingast1989) and more recently Ershova (Reference Ershova2019), on the other hand, links salience to lower supranational delegation and discretion. I also control for inter-institutional conflict (Ershova Reference Ershova2019) through the inclusion of early agreements under codecision and the distance of preferences between the median Commissioner and the pivotal Council member under other procedures. Summary statistics of all main variables of interest are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary statistics of main dependent and independent variables

Analyses

Determinants of delegation paths

I test my first three hypotheses (Hypotheses 1 to 3) relating to the choice of the delegation path by means of an ordered logistic regression model, as my dependent variable is an ordered categorical variable ranging from completely national implementation (1) to completely supranational implementation (4). I insert one interaction term for the curvilinear hypothesis.

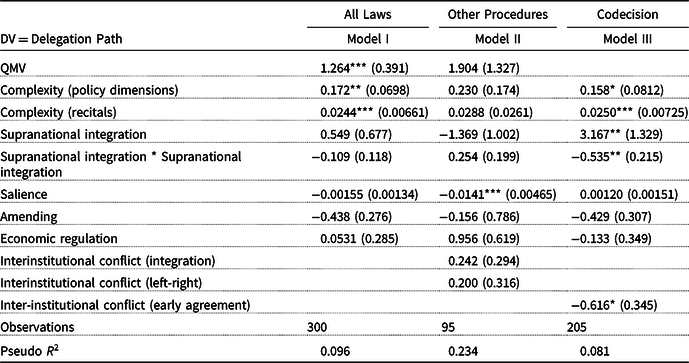

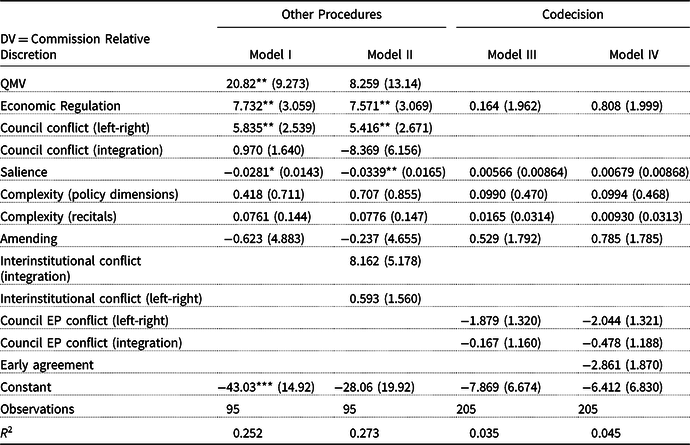

I specify three models: the first includes all laws. The second only laws where the Council is the only principal and the third only laws adopted under codecision. The results are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5. Determinants of delegation choice

Ordered Logistic Regression with Treaty Fixed Effect (omitted from table). Standard errors in parentheses. Legend: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Table 6. Determinants of the Commission’s relative discretion

Multivariate OLS regression with Treaty fixed effects. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Legend: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

The effect of QMV is strong when all laws are included (Model I): On average, the probability of observing a fully national implementation path decreases by 20 percentage points under QMV than unanimity. Conversely, the probability of observing an implementation path shared between national administrations and the Commission increases by 20 percentage points under QMV compared to unanimity, the implementation path involving agencies by 14 percentage points and the completely supranational path by about 2 percentage points. The effect loses statistical significance in Model II. This may be due to the considerably smaller sample size and to the strong effect of salience in this subsample (see below).

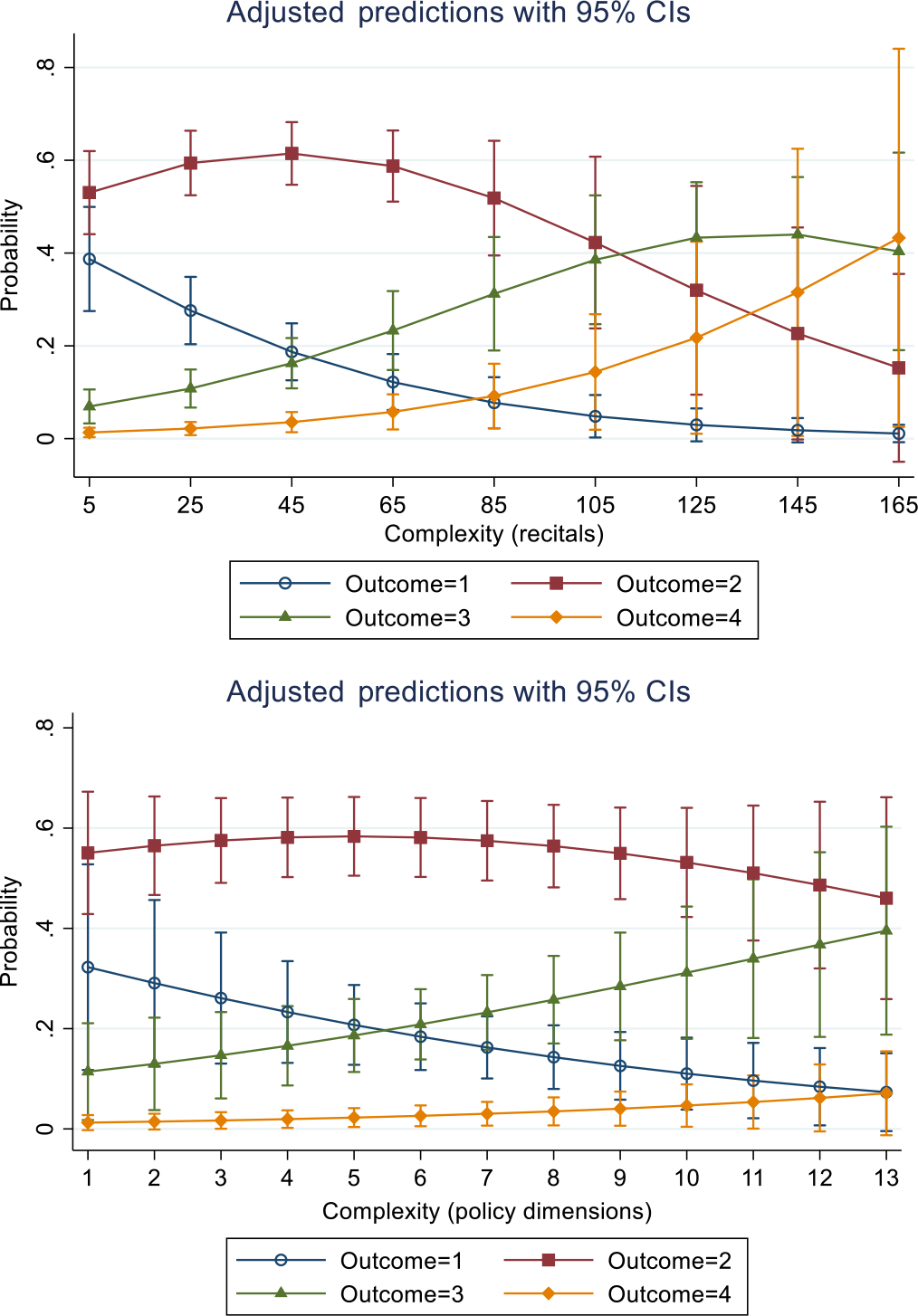

Both complexity measurements yield significant and robust results in Models I and III, in line with Hypothesis 2, while it is not significant in Model II. On average, as shown in Figure 5, more complex laws are more likely to involve the supranational level and twice as less likely to involve only the national level (outcome 1). The effect is more significant for the traditional measurement of complexity (i.e. the number of recitals in the legislative act), while the measurement grasping multi-dimensionality has lower significance.

Figure 5. Effect of complexity on probability of agent selection.

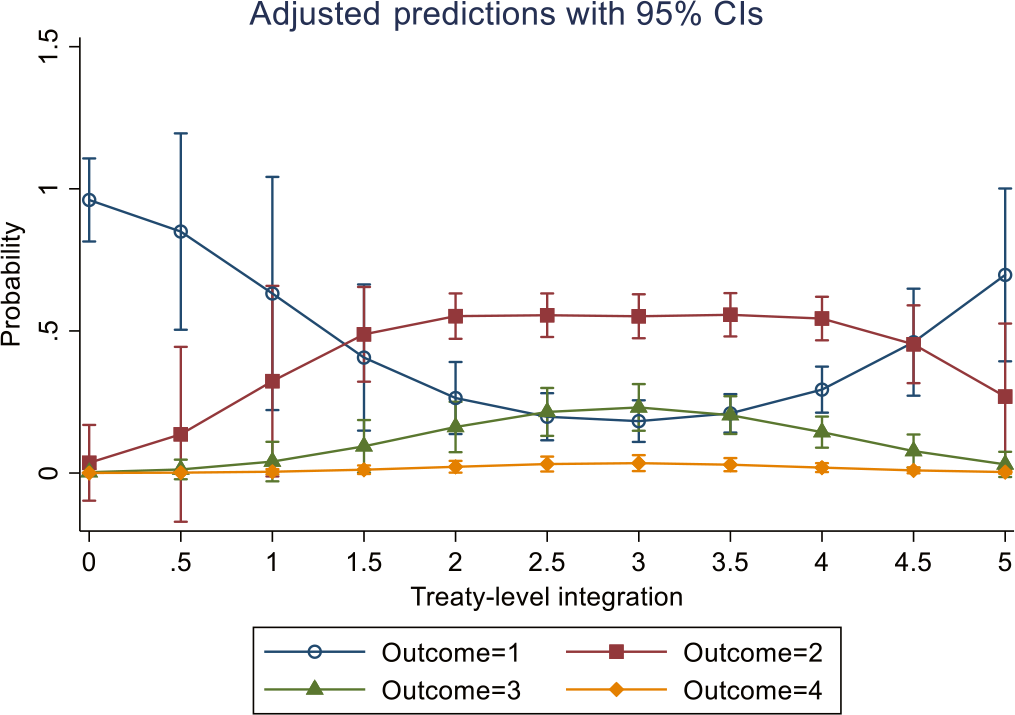

Regarding the level of supranational integration, the results corroborate Hypothesis 3 only for laws adopted under codecision. Figure 6 visualises the results.

Figure 6. Effect of treaty-level integration on probability of agent selection.

The effect is particularly marked in the case of outcome 1 (national implementation), indicating that a completely national implementation path is extremely likely (96% probability) in case of no supra-nationalisation, less so for medium levels of integration (26%–18% probability) and more likely for high integration levels. On the contrary, the other three paths display the opposite trend, characterised by low probabilities for low integration levels, higher in the middle and low again for very high integration levels. This is particularly marked in the case of agencies’ involvement, as probability with low integration is very close to 0, while it reaches 23% for medium integration levels. In the case of the Commission, the trend is less visible as the outcome is not very frequent. Yet, probability goes from 0 to 3.5 and then decreases to 0 again.

Among the control variables, an interesting finding relates to salience. While it does not have any significant effect on Models I and III, it displays a strong and highly significant effect for laws adopted only by the Council. In these cases, the more salient the policy area is, the more likely legislation delegates to national administrations. This finding is interesting because salience seems to be the only factor affecting delegation choices when the Council is the only principal. It suggests that when the Council has the power to decide by itself, it systematically favours more national control over policy implementation in the case of high political salience, all other things being equal. However, this mechanism does not seem to apply when the European Parliament is involved. Given that the measurement I use for salience is the importance attached to policy issues in the Council agenda, it may be the case that under codecision issues that are salient to the Council are counter-balanced by the priorities of the Parliament. Finally, under codecision, early agreements seem to slightly increase the likelihood of opting for a national implementation path, while decreasing the likelihood of the shared one.

Relative discretion

I now test my hypotheses accounting for varying degrees of relative discretion (Hypotheses 4 and 5) by means of multivariate OLS regression analysis, given that my second dependent variable is continuous. I report four models. I distinguish between acts adopted under codecision and acts adopted under other procedures, and I also control for complexity as it might as well affect discretion granted of implementers.

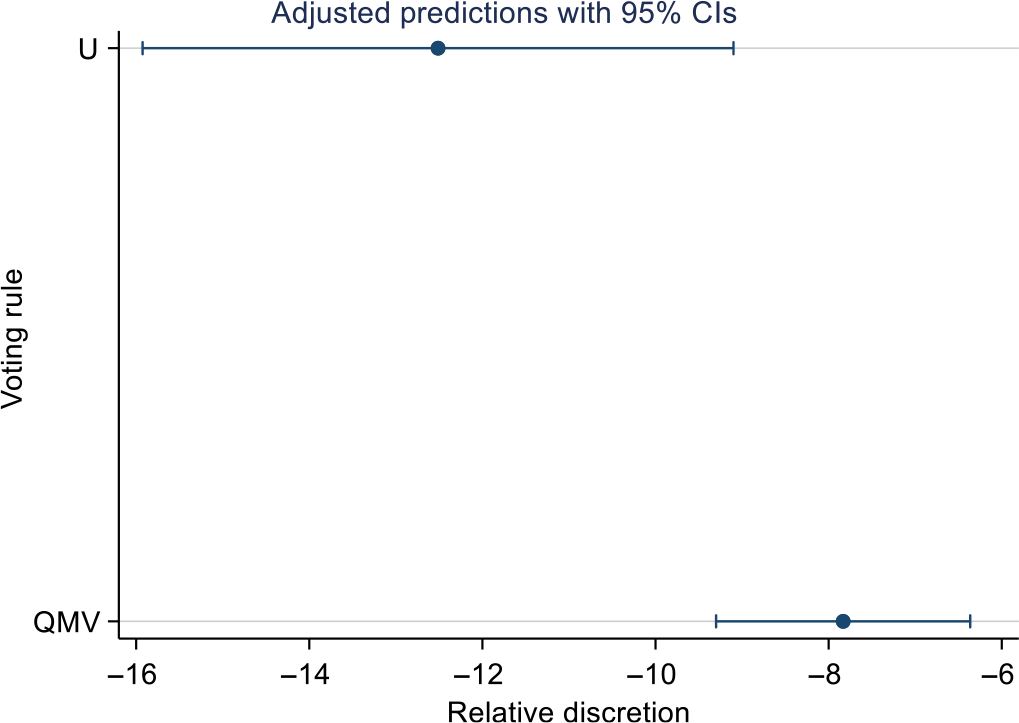

First of all, as shown in Figure 7, QMV grants on average more discretion to the Commission vis-à-vis national administrations, both significance and effect are quite strong, given that shifting from unanimity to QMV increases the Commission’s relative discretion, by on average 120%. Hence, not only QMV produces a higher likelihood of opting for more supranational agents, it also increases the discretion of the Commission vis-à-vis national administrations.

Figure 7. Effect of QMV on relative discretion.

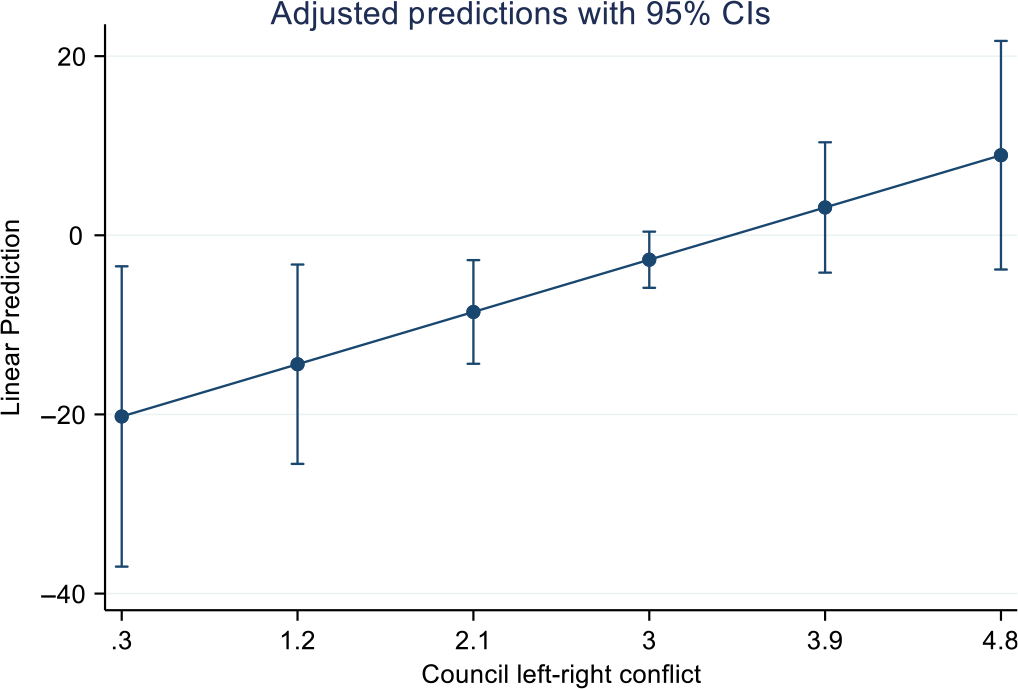

Regarding conflict, Model 1 supports Hypothesis 5 by showing that with the increase in conflict among Council members on the left-right dimension (the integration one is not significant), higher discretion is granted to the Commission. On average, one standard deviation increase in both left-right and integration conflict increases the Commission’s relative discretion by about 40%, as displayed in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Effect of conflict in the Council on the Commission’s relative discretion.

Regarding the conflict between the Council and the European Parliament under codecision, the results are not statistically significant. Yet, the direction of the relationship contradicts Hypothesis 5. Indeed, it seems that higher conflict between the EP and the Council leads, on average, to lower relative discretion for the Commission favouring, therefore, national administrations for policy implementation. The reason underlying this negative association may deserve further investigation. For example, Gastinger and Adriaensen (Reference Gastinger and Adriaensen2019) suggest that delegation dynamics when the EP is involved in the negotiating process may be affected by the interaction between the European Parliament and citizens/civil society. Finally, similar to the previous empirical analysis, the results show that salient laws grant on average less discretion to the Commission than to national administrations. The effect is significant when all laws are included as well as when the Council is the only principal, while it loses significance under codecision.

Discussion

Throughout this article, I have mapped delegation paths and agents’ discretion in EU secondary legislation in the post-Maastricht era, on the basis of a data set embracing this period up to 2016. As much as description per se does not provide causal explanation, this step was useful for the purposes of a subsequent investigation of why specific delegation choices occur and how much agent control is associated with them. Assessing why principals opt for different degrees of supranational implementation was the second step of the empirical analysis. Following a PA framework, I have argued in favour of functional logics (complexity) and path dependence (degree of previous integration). Indeed, complexity is a strong predictor of the choice of involving agencies and the Commission, more than just national administrations and the Commission, or just national administrations. Although national administrations may be generally endowed with more resources than the Commission and agencies, supranational actors are increasingly involved as the complexity increases. Another interesting finding relates to the degree of integration in the EU treaties. This latter is associated with agent selection in a curvilinear way. This is especially relevant in view of the recent new intergovernmentalist literature (Bickerton et al. Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015), supporting the view of integration without supranationalisation as the curvilinear trend may point to a decreasing willingness to grant authority to the supranational level over time and across policy. However, the result leaves unanswered why this relationship holds only for laws adopted under codecision.

In my analysis, I have also taken pooling into account as a major determinant of supranational delegation, which is partly confirmed by the results, suggesting that QMV keeps working as a “commitment technology” (Franchino Reference Franchino2007, p. 187), ensuring higher supranational delegation and discretion.

As far as discretion is concerned, one result confirms previous findings and another opens a scholarly debate. When the Council is the only principal, conflict among Council members shapes delegation choices so as to have higher supranational discretion. However, when the European Parliament is involved, the Commission appears to be granted relatively lower discretion when the Council and the Parliament display more heterogeneous preferences. This may depend on the preference divergence between the Commission and principals, combined with the relative bargaining power of the two legislators. Future research might want to expand research in this field through in-depth case studies along the lines of da Conceição-Heldt (Reference da Conceição-Heldt, Delreux and Adriaensen2017) and Gastinger and Adriaensen (Reference Gastinger and Adriaensen2019).

Lastly, the results of the effect of salience are interesting, as the Council seems to be less willing to grant supranational delegation and discretion when issues are high on its agenda.

Where does implementation lie, then, and why? This study shows that the copresence of multiple actors that together participate in the implementation of EU policies is subjected to impressive variation. The PA approach explains the choice of going more or less supranational as a response to functional necessities as well as previous delegation decisions, but that delegation to supranational institutions may be halted by political dynamics connected to the broader process of EU integration. Supranational leeway in turn is favoured by conflict within the Council. Yet, the relevance of this finding is somewhat limited by the fact that in the past 10 years the European Parliament has been colegislator and is increasing its influence (Costello and Thomson Reference Costello and Thomson2013). For this reason, the impact of the conflict between Parliament and the Council bears growing interest and should enjoy more space in the future research on delegation.

Finally, the explanatory power of the study presents a limitation, as the sample size may be considered small in comparison with the whole EU legislative output. In order to further increase the robustness and reliability of these findings, future research could extend the investigation to a much wider body of legislation by employing methodologies allowing a swifter extraction of delegation relationships from legal acts. For example, recent scholarly works by Shaffer (Reference Shaffer2020) and Anastasopoulos and Bertelli (Reference Anastasopoulos and Bertelli2020) offer promising research avenues, through the application of natural language processing and machine learning techniques to the analysis, respectively, of the United States and EU legislation.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X20000100.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Fabio Franchino, Camilla Mariotto, Christian Rauh, Hussein Kassim, Marcello Carammia, Mattia Guidi and three anonymous referees for their precious feedback on previous versions of this article.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/JVLKNW