Introduction

Culture has a significant impact on the way individuals interpret and engage with the world and those around them (Jandt, Reference Jandt2007). This set of customs, beliefs and traditions have far-reaching effects that influence psychopathology and psychotherapy across the globe (Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019). In an effort to accommodate for such effects, various psychological interventions have been adapted to align with cultural impacts and this is often implemented through cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). CBT is a common therapeutic approach, applied to a wide scope of disorders with high success rates (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2012). Behaviourism was first developed in the early 1900s and therapies based on this rationale emerged in the mid-1950s (Thorndike, Reference Thorndike1905; Watson, Reference Watson1913). Interventions such as rational emotive behaviour therapy and CBT were developed with the aim of challenging dysfunctional thoughts and behaviours in individuals to reduce symptoms of psychopathology (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979; Ellis, Reference Ellis1995). CBT in particular has undergone several adaptations over the years. Initially, cognition was thought to be made up of retroactive structural processes over which one had limited control, but this view quickly changed, and the processes of self-knowledge and psychodynamics were recognised as influences on cognition (Ruggiero et al., Reference Ruggiero, Spada, Caselli and Sassaroli2018). There is scope for CBT to be implemented with considerable adjustment, with flexibility relating to client goals and outcomes as well as inclusion of topics that hold importance for the client (Strunk et al., Reference Strunk, Mandel, Ezawa and Kendll2021). The original model of CBT has gone through several adaptations to make it more suitable for various psychological conditions and the last two decades have seen an enormous drive towards the lateral spread of culturally adapted CBT through to non-Western European and non-North American cultures.

The need for cultural adaptation

Culture can be defined as ‘the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs’ (IBE-UNESCO, 2008). This can encompass one’s religious views, their ethnic or racial origin as well as their national identity, hence providing a holistic understanding of one’s beliefs and backgrounds and the influence they exert. Within recent years, globalisation has rapidly increased, which has led to an influx of migration across the globe. Due to this, cultural, ethnic and racial diversity is becoming more recognised and acknowledged, which has led a drive towards providing equitable, culturally sensitive and effective clinical services to cultural minority groups across the Global North (the developed, affluent countries). In a similar fashion, the Global South (the low-income, marginalised countries) has seen an increased interest in modern psychotherapies. However, many observers noticed that CBT in its standard form is not suitable for individuals from non-Western backgrounds due to the ethnocentric nature of such psychosocial interventions which were developed based on Western cultural values (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019).

Cultural adaptations are systematic modifications of various research-based interventions to include considerations of various cultural beliefs and ideas to ensure that such interventions are compatible for patient engagement (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009). Culturally adapting CBT is vital to ensure relevance and effectiveness of such an intervention for the individual. CBT involves understanding and exploring the individual’s dysfunctional thoughts and assumptions in order to challenge and change them (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). As culture has such far-reaching effects into all aspects of one’s life, it is important to remember that illness and psychopathology will also be influenced. Due to this, people from non-Western backgrounds may have difficulty adjusting to and trusting mental healthcare services (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019). If interventions such as CBT are implemented without adaptation, individuals are likely to disengage and there is the risk of poor outcomes (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Smith and Turkington2005). A systematic review looking at the need to implement culturally adapted public health interventions revealed that 64.3% of individuals believed that adaptations are key requirements to ensure cultural appropriateness (Escoffery et al., Reference Escoffery, Lebow-Skelley, Haardoerfer, Boing, Udelson, Wood and Mullen2018). Laungani (Reference Laungani2004) shared four core dimensions across which Asian and Western cultures differ: individualism-communalism, cognitivism-emotionalism, free-will-determinism, and materialism-spiritualism. These dimensions will cause variation in perception and understanding of experiences. Participants of African-Caribbean and South Asian descent attribute symptoms of psychosis and schizophrenia to supernatural experiences or wrongdoings in their past life, and are inclined to turn to faith healers for treatment and support (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Phiri and Gobbi2010). Similarly, patients from China stated that supernatural causes and family stress led to their symptoms of schizophrenia; again, they would often seek help from faith healers (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Luo, Liu, Liu, Lin, Liu, Xie, Hudson, Rathod, Kingdon, Husain, Liu, Ayub and Naeem2017). Individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from a Hispanic background believe that all events are uncontrollable and inevitable but also that experiencing excessive stress is normal which delays them seeking treatment and support (Ruef et al., Reference Ruef, Litz and Schlenger2000). Finally, cultural adaptation of psychotherapy has been advocated from an ethical point of view (Pantalone et al., Reference Pantalone, Iwamasa and Martell2010). In fact, it has been argued that ‘delivering mental health services outside of one’s area of competence constitutes an ethical infraction’ (Ridley, Reference Ridley1985).

Frameworks for culturally adapting psychotherapies: a short history

Methods for identifying frameworks

A vast number of frameworks to inform the development of culturally adapting therapies have been published. We acknowledge many more publications, which share insights on culturally adapting therapies of which a selection is chosen and reported in Table 1. All these frameworks provide guidelines on the processes and elements involved in culturally adapting therapies, some outlining more general procedures whilst others highlight specific demographics or therapies.

Table 1. Frameworks for cultural adaptation of psychotherapies

The first guidelines on culturally adapting psychotherapies, the Social Cognitive Framework, was proposed by López et al. (Reference López, Grover, Holland, Johnson, Kain, Kanel and Rhyne1989) and suggested that the process of cultural adaptation consists of three stages: (1) being unaware of cultural issues, (2) heightened awareness of cultural issues, and (3) cultural sensitivity. A few years later, the ecological validity model was published by Bernal and colleagues (Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995) which highlighted eight key areas needing to be addressed in order for cultural adaptations to be successful. These were: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods and context (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995). This provided context and relevant examples to the specific areas and topics in which there are great differences between Western cultures and other minority cultures around the world. The multidimensional model mentions culture and structure as the two core elements which inform cultural responsiveness; this was believed to be enough adjacent to be culturally accommodating (Koss-Chioino and Vargas, Reference Koss-Chioino, Vargas, Vargas and Koss-Chioino1992). Although this framework provides a variety of examples as to how cultural changes can be modified, it does not really explore the depth to the topic of culture and its far-reaching impacts. The adaptation framework developed by Tseng (Reference Tseng1999) describes three levels of adaptation: technical, theoretical and philosophical. These branch of into a further nine areas which explore the breadth of impact culture has on various elements of therapy, including the therapeutic relationship and therapeutic model (Tseng, Reference Tseng1999). This model introduces new understanding of how cultural adaptations fit within therapy and the various elements that need to be addressed to develop an accommodating intervention.

Resnicow et al. (Reference Resnicow, Soler, Braithwaite, Ahluwalia and Butler2002) explored the impact that culture has on the structure of therapies, looking at both surface level and deep level structure. Whilst this proposes similar understanding to Koss-Chioino and Vargas (Reference Koss-Chioino, Vargas, Vargas and Koss-Chioino1992), Resnicow et al. (Reference Resnicow, Soler, Braithwaite, Ahluwalia and Butler2002) go on further to explain the various elements of culture that influence the target population and hence outcomes and engagement with therapy. The Cultural Adaptation Process Model introduced the idea of involving treatment developers and cultural adaptation theorists to make appropriate cultural adjustments to interventions whilst maintaining the feasibility and efficacy of the therapy and its outcomes (Domenech-Rodriguez and Wieling, Reference Domenech-Rodríguez, Wieling, Rastogi and Wieling2005). Again, stakeholders were involved, but this time it was community leaders with whom the need for interventions was shared and the needs of the community were discussed (Domenech-Rodriguez and Wieling, Reference Domenech-Rodríguez, Wieling, Rastogi and Wieling2005). Castro et al. (Reference Castro, Barrera and Martinez2004) moved away from the focus on the patient and more towards the programme delivery staff, programme administration and community factors, stating the need to understand the impact of these. They also went on to highlight two specific internal cognitive processes and how these may exert influence, rather than looking at the individual and their cultural influences overall (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Barrera and Martinez2004). The Selective and Directed Treatment Adaptation Framework proposed that cultural adaptation was not needed consistently, but only when outcomes of standard un-adapted interventions produced significantly poorer outcomes compared with adaptations (Lau, Reference Lau2006). It also mentions when adaptations can either enhance engagement by creating an appropriate link with the cultural group or can provide more relevant context to the intervention (Lau, Reference Lau2006). Barrera and Castro (Reference Barrera and Castro2006) build further on Lau’s (Reference Lau2006) work, exploring the development of equivalent, yet culturally relevant, scales and outcome measurements.

Hwang (Reference Hwang2006) provided a detailed framework, outlining six core domains which need to be addressed for adaptations; these were explained further through various principles. This framework mentions the complexities of cultural adaptation, stating it is important to gain context and understand the issues around adjustment before implementation (Hwang, Reference Hwang2006). Leong and Lee (Reference Leong and Lee2006) and Whitbeck (Reference Whitbeck2006) build on previous understanding by highlighting the need to identify gaps in current cultural-adaptation literatures and the importance of testing the adapted interventions for feasibility and efficacy before implementation. Kumpfer et al. (Reference Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, Teixeira de Melo and Whiteside2008) suggested making small changes to interventions and testing at each point through pilot studies and focus groups. This can ensure that the intervention does not change too much from the original than needed, helping to maintain cultural equivalence of outcome measures (Kumpfer et al., Reference Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, Teixeira de Melo and Whiteside2008). Rathod et al. (Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019) developed the Cultural Adaptation Framework (CAF) through revisions of previous models based on evidence and literature (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015; Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Chang and Nishjzono2005). Cardemil (Reference Cardemil2010) looked at gaps in the literature relating to the structure and delivery of adapted interventions, reiterating the need for changes to be made in a holistic manner for them to be culturally appropriate. The importance of testing and evaluating the efficacy of adapted interventions is also repeated (Cardemil, Reference Cardemil2010). The Cultural Adaptation Process Model and the Cultural Treatment Adaptation Framework both include the majority of the concepts already mentioned in previous frameworks: the need to consult previous literature, the use of stakeholders in pilot studies, and assessing outcomes post-intervention (Chu and Leino, Reference Chu and Leino2017; Domenech-Rodriguez et al., Reference Domenech Rodríguez, Baumann and Schwartz2011).

The cultural adaptation frameworks: current understanding

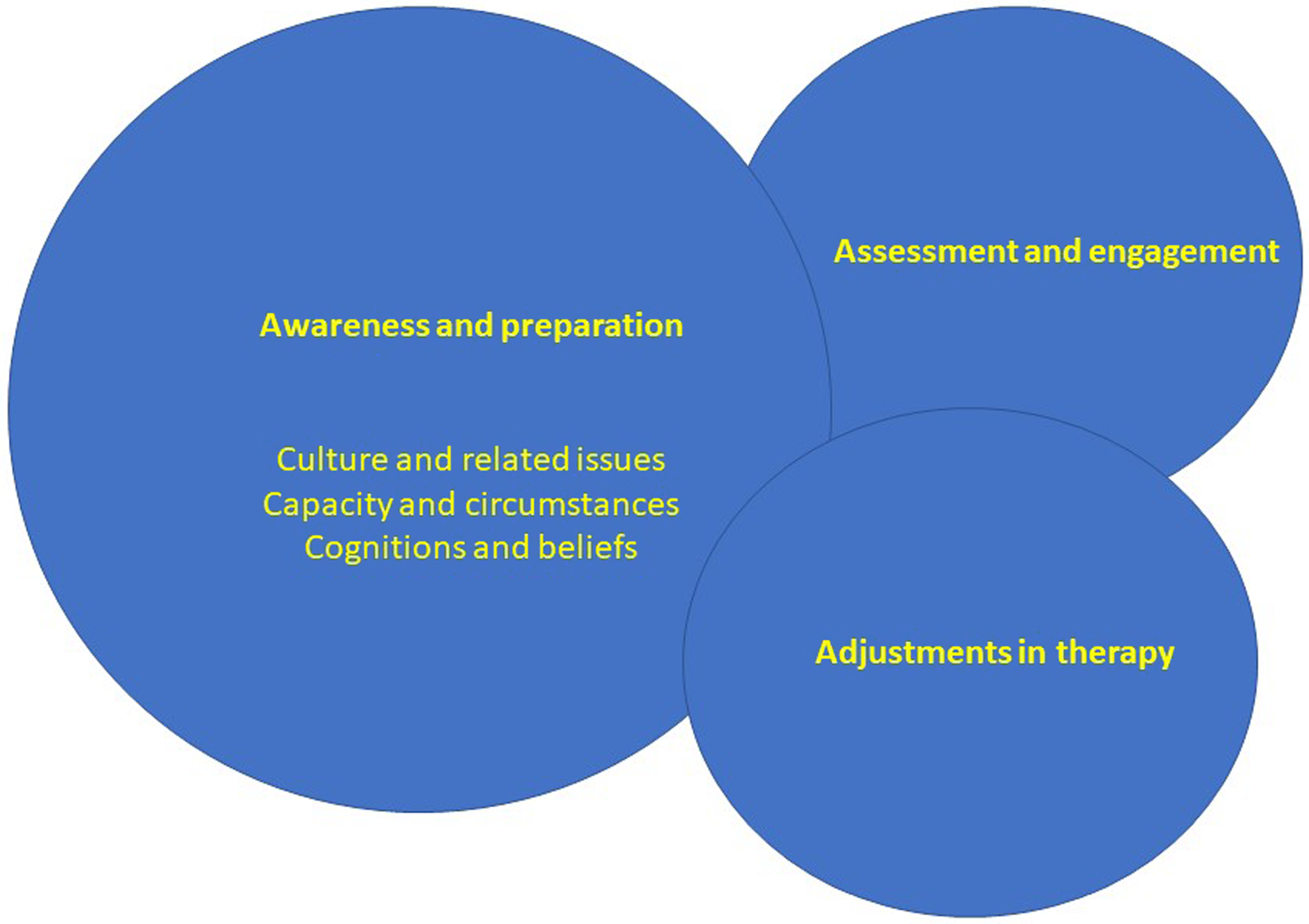

The Southampton Adaptation Framework was the first framework developed for culturally adapting CBT (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Ayub, Gobbi and Kingdon2009). This framework however, involved immense stakeholder involvement, providing insight into the adjustment and engagement processes of adapted interventions (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Ayub, Gobbi and Kingdon2009). This was one of the first cultural adaptation frameworks to be tested in a randomised controlled trial (RCT), stressing the importance of testing adjusted interventions to ensure they produce positive outcomes (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Ayub, Gobbi and Kingdon2009) (see Fig. 1). The framework proposes a ‘bio-psycho-socio-spiritual’ model of causation of illness, instead of a bio-psycho-social model. The framework consists of three major areas (the triple A principle) of concern: (1) cultural awareness, (2) assessment and engagement, and (3) adjustments in therapy. Cultural awareness can be further can be divided into three areas: (1) culture, religion and spirituality, (2) context and capacity of the system, and (3) cognitions and beliefs. Please see Table 2 for further details. This framework has been used to adapt CBT for depression and anxiety in Saudi Arabia (Algahtani et al., Reference Algahtani, Almulhim, AlNajjar, Ali, Irfan, Ayub and Naeem2019) and Morocco (Rhermoul et al., Reference Rhermoul, Naeem, Kingdon, Hansen and Toufiq2017) and psychosis in China (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Luo, Liu, Liu, Lin, Liu, Xie, Hudson, Rathod, Kingdon, Husain, Liu, Ayub and Naeem2017) and for and emotional dysregulation in learning disability in Canada (McQueen et al., Reference McQueen, Blinkhorn, Broad, Jones, Naeem and Ayub2018). Currently, the framework is being used in Canada to adapt CBT for depression and anxiety for the South Asian population (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Tuck, Mutta, Dhillon, Thandi, Kassam, Farah, Ashraf, Husain, Husain, Vasiliadis, Sanches, Munshi, Abbott, Watters, Kidd, Ayub and McKenzie2021). The framework has been used to adapt and test CBT for a variety of issues such as depression (Naeem, Gul, et al., Reference Naeem, Gul, Irfan, Munshi, Asif, Rashid, Khan, Ghani, Malik, Aslam, Farooq, Husain and Ayub2015), schizophrenia (Naeem, Saeed, et al., Reference Naeem, Saeed, Irfan, Kiran, Mehmood, Gul, Munshi, Ahmad, Kazmi, Husain, Farooq, Ayub and Kingdon2015) and OCD (Aslam et al., Reference Aslam, Irfan and & Naeem2015) self-harm (Husain et al., Reference Husain, Afsar, Ara, Fayyaz, ur Rahman, Tomenson and Chaudhry2014).

Figure 1. Fundamental areas of adaptation.

Table 2. Components of the Southampton Adaptation Framework

Implementation of culturally adapted CBT in existing services remains a challenge. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme in England has a 5-stage outline for adjusting interventions to the needs of the individuals in order to facilitate effective treatment outcomes (Clark, Reference Clark2011). Individuals from minority ethnic backgrounds tend to have a disparate experience of mental health services. To combat this, IAPT have enabled self-referrals to reduce discriminations in accessing mental health services but now there is a need to understand and address the shortcoming of therapeutic interventions themselves (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Naeem, Halvorsrud and Phiri2020). To further support the work of the IAPT programme, the BAME Service User Positive Practice guide was developed in 2019 (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019). It outlined key targets and guidelines that IAPT services needed to incorporate to ensure better access and outcomes for minority ethnic patients (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Naeem, Halvorsrud and Phiri2020). Whilst IAPT services are trying to become more accommodating, there are very few culturally adapted interventions currently being offered such as culturally adapted IAPT services for individuals from a Tamil background (Bahu, Reference Bahu2019). Action must be taken in this area to directly improve engagement and outcomes for individuals from minority ethnic backgrounds.

Culturally adapted psychotherapies – the evidence

What works? Types of adaptations

A systematic review of culturally adapted psychological treatments found that most alterations were made in the implementations rather than content of the intervention (Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014). For example, adaptations to language, context and therapist were common implementations. Likewise, Degnan et al. (Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017) identified 9 core themes around which cultural adaptations were based including family, communication, therapeutic alliance, and treatment goals. This was beneficial as it ensured fidelity was maintained of the intervention itself, whilst accommodating for cultural applicability (Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014). Chowdhary et al. (Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014) evaluated cultural adaptation using the Medical Research Council framework (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Dieppe, Macintyre, Michie, Nazareth and Petticrew2008) and Bernal and Saez-Santiago’s model (Bernal and Sáez-Santiago, Reference Bernal and Sáez-Santiago2006) to describe the nature of adaptation, while Degnan et al. (Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017) used qualitative methodology to evaluate the nature of cultural adaptations. Griner and Smith (Reference Griner and Smith2006) classified adapted interventions based on an explicit statement of culture, matched race or ethnicity between the client and the therapist, use of the client’s preferred language, incorporation of cultural values and worldview into sessions, collaboration with cultural others, appropriately localized services, and relevant spirituality discussion. Interventions that were adapted for specific cultural groups were 4 times more effective than interventions adapted for ethnic minority groups as a whole; however, adapted treatments for collective minority groups were still effective compared with un-adapted interventions (Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006).

Numerous studies have reported that cultural adapted interventions implement changes in the following domains: language, family, content, context and access (Aujla-Sidhu, Reference Aujla-Sidhu2020; Lehman and Bordlein, Reference Lehmann and Bördlein2020; Rojas-Garcia et al., Reference Rojas-García, Ruíz-Pérez, Gonçalves, Rodríguez-Barranco and Ricci-Cabello2014; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Reisig and Cullen2020). Implementing interventions at home, as well as introducing psychoeducation is also an effective technique to increase beneficial outcomes (Rojas-Garcia et al., Reference Rojas-García, Ruíz-Pérez, Gonçalves, Rodríguez-Barranco and Ricci-Cabello2014). Similarly, Degnan et al. (Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017) reported interventions were more successful when patients attended with relatives rather than alone. Multiple reviews found age as a predictor of the effect of culturally adapted interventions whilst other studies reported shared language between client and therapist to improve the effectiveness of the interventions (Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti and Stice2016; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Rodríguez and Bernal2011; Sutton, Reference Sutton2015).

Family is a core factor within many communal societies when it comes to help-seeking and treatment engagement. Therefore, interventions involving the patient and their family are likely to bolster treatment outcomes as core cultural values have been considered when implementing treatments (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019). Family members would also be able to support homework completion, again increasing positive outcomes for the patient (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019). CBT recommendations for individuals with psychosis outline the need to incorporate family interventions within treatment plans to ensure improved outcomes, and this has been supported by a large body of evidence (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Chan, Chien, Bressington, Mui, Lee and Chen2020; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Ayub2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015; Sitko et al., Reference Sitko, Bewick, Owens and Masterson2020). A systematic review studying the effectiveness of culturally adapted CBT interventions also incorporated family interventions within their analyses (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017). Most of the reviewed interventions acknowledged the importance of family involvement in patient treatment and recovery, which involves adjustments such as home visits, family sessions, or extra homework activities (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017). Treatment goals were also modified in 28% of studies to ensure that achievements aligned with cultural values (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017). These included and considered managing family expectations and meeting the needs of the family as a unit, as well as keeping family integrated in the remission process (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017).

How effective is it?

So far, multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses of culturally adapted psychosocial interventions have been published. Various mental health conditions have been considered through different patient demographics (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity) and also different psychosocial interventions. Although studies have been carried out in a systematic and rigorous manner, the evaluations contained several flaws, including methodological heterogeneity. The authors reported several biases, such as the effect of risk biases, including publication bias, blinding of outcome assessors, and attrition bias. This would of course affect the validity, applicability and generalizability of the results and conclusions.

Chowdhary et al. (Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on culturally adapted interventions for ethnic minority groups with depressive disorders. The analysis revealed that adapted treatments significantly improve patient symptoms compared with unadjusted interventions (standardized mean difference (SMD)=–0.72, 95% CI –0.94 to –0.49). A systematic review and meta-analysis on culturally adapted interventions for schizophrenia revealed that adapted interventions presented significant improvements in overall symptom severity (g=–0.39, 95% CI –0.36 to –0.09) as well as positive (g=–.056) and negative (g=–0.39) symptoms (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017). This research did not uncover sufficient evidence to support the claim that culturally adapted interventions are more advantageous compared with unadapted treatments (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017). The meta-analysis by Griner and Smith (Reference Griner and Smith2006) revealed a moderate effect size (d=.45), indicating that culturally adapted interventions provide beneficial outcomes for patients. Adapted interventions aimed at women with perinatal depression were all effective, providing a significant reduction in depressive symptoms (–0.44, 95% CI –0.67 to –0.22) (Rojas-Garcia et al., Reference Rojas-García, Ruíz-Pérez, Gonçalves, Rodríguez-Barranco and Ricci-Cabello2014). Rojas-García et al. (Reference Rojas-García, Ruíz-Pérez, Gonçalves, Rodríguez-Barranco and Ricci-Cabello2014) also found that culturally adapted interventions were twice as effective with Asian Americans compared with other cultural minorities. However, another review reported a lower efficacy of outcomes for the Chinese population (95% CI g=–1.50 to –0.47), compared with other ethnic groups (g=–0.56, 95% CI –0.85 to –0.26), following adapted interventions targeting schizophrenia (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Baker, Edge, Nottidge, Noke, Husain, Rathod and Drake2017).

A meta-analysis by Soto et al. (Reference Soto, Smith, Griner, Domenech Rodríguez and Bernal2018) revealed a moderately strong effect size (d=.50) across 99 studies, suggesting that culturally adapted interventions result in increased positive outcomes. Using a Latino population, a systematic review of 60 adapted CBT interventions was carried out (Hernandez Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez Hernandez, Waller and Hardy2020). New findings revealed that both adapted and unadapted CBT provided the same beneficial outcomes for effectiveness and retention rates in Latin American populations (Hernandez Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez Hernandez, Waller and Hardy2020). Large effect sizes (d=1.00) were prevalent across most non-adapted CBT studies; adapted CBT effect sizes range from d=0.13 to 4.18, with 75% retention and mid- to high-quality studies (Hernandez Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez Hernandez, Waller and Hardy2020). This led to the suggestion of whether clinicians should be encouraged to improve their delivery of CBT to ensure consistent positive outcomes rather than adapting CBT for different ethnic groups (Hernandez Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez Hernandez, Waller and Hardy2020). Again, within the Latino population, interventions aimed at individuals with depression or anxiety revealed that those who engaged with adapted interventions reported outcomes 0.344 standard deviations above control groups, indicating very high outcomes (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Ayers, Sun and Zhang2020). A systematic review looking at the effect of adapted narrative exposure therapy on reducing trauma symptoms in refugees found a significant reduction across all studies (–0.59, 95% CI –1.19 to –0.31) (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Reisig and Cullen2020).

Aujla-Sidhu (Reference Aujla-Sidhu2020) conducted a systematic review examining culturally adapted interventions for a South Asian population with depression. The results of this study displayed a significant reduction in outcome measure scores for individuals engaging with CBT, highlighting the effectiveness of adapted interventions in reducing depressive symptoms (Aujla-Sidhu, Reference Aujla-Sidhu2020). A comprehensive systematic review by Anik et al. (Reference Anik, West, Cardno and Mir2021) also found statistically significant effects promoting the use of culturally adapted interventions for depression in comparison with control groups (SMD=–0.63, 95% CI –0.87 to –0.39), which is in line with previous findings and reviews (Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014). Subgroup analysis did reveal when implementing an intervention with a majority ethnic group that the effect was much larger (Anik et al., Reference Anik, West, Cardno and Mir2021). If the therapist and client share ethnic background, the effects are successful in CBT and are amplified further (Anik et al., Reference Anik, West, Cardno and Mir2021).

Discussion

Culturally adapted psychotherapy frameworks have evolved over the past 30 years. These frameworks provide some guidance on culturally adapted psychosocial interventions. Some frameworks promoted more surface adaptations, which provided a basis to formulate more concrete suggestions and recommendations (Koss-Chioino and Vargas, Reference Koss-Chioino, Vargas, Vargas and Koss-Chioino1992; López et al., Reference López, Grover, Holland, Johnson, Kain, Kanel and Rhyne1989). As time progressed, frameworks began to focus on the intricacies of culture and the various elements which can affect an individual. This led to the development of more comprehensive framework, which focused on implementing core adaptations to interventions (Kumpfer et al., Reference Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, Teixeira de Melo and Whiteside2008; Hwang, Reference Hwang2006; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019). Similarly, frameworks generally avoid changes in the theoretical or philosophical underpinnings of therapy. Making changes in the theoretical basis of therapy risk deviation from the core model of a particular therapy. Most frameworks were developed and published in North America, based on the therapist’s personal experience or, at times, based on a literature review. As the need for culturally adapted intervention is becoming more prominent, frameworks and guidelines are being implemented and tested in various research and literature. All frameworks mentioned above have been utilized in books, guidelines and research articles, all focusing on adapted interventions (Barrera and Castro, Reference Barrera and Castro2006; Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995; Hwang, Reference Hwang2006). Many of the recent frameworks have also been tested through pilot studies and RCTs to ensure further validity and efficacy (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Barrera and Martinez2004; Domenech-Rodriguez and Wieling, Reference Domenech-Rodríguez, Wieling, Rastogi and Wieling2005; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Ayub, Gobbi and Kingdon2009; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019; Tseng, Reference Tseng1999). Whilst systematic reviews looking at adapted interventions have been carried out, there has been no comprehensive review including all scientific evidence relating to culturally adapted CBT. This lack of scientific rigor in developing and testing adaptation frameworks needs to be addressed.

Current evidence suggests that culturally adapted interventions can be effective. Most meta-analyses showed a moderate to large effect for culturally adapted interventions. However, most of these meta-analytic reviews lacked methodological rigor and other problems, such as poor consideration of theoretical underpinning and cultural issues. The overall approach in cultural adaptation studies seems to compare western European and North American to non-western cultures as a whole, without realizing the diversity and sub-cultures within the non-western groups. While most studies included in meta-analyses used CBT for adaptation, currently, no comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis is available that encompass all implementations of culturally adapted CBT and its effectiveness.

Frameworks have outlined various core elements which are needed to culturally adapt interventions to make then relevant for an ethnic minority population. The main elements mentioned across models and frameworks are: language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, context, therapeutic relationship, and community involvement (Barrera and Castro, Reference Barrera and Castro2006; Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995; Cardemil, Reference Cardemil2010; Castro et al., Reference Castro, Barrera and Martinez2004; Domenech-Rodriguez and Wieling, Reference Domenech-Rodríguez, Wieling, Rastogi and Wieling2005; Hwang, Reference Hwang2006; Koss-Chioino and Vargas, Reference Koss-Chioino, Vargas, Vargas and Koss-Chioino1992; Kumpfer et al., Reference Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, Teixeira de Melo and Whiteside2008; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Ayub, Gobbi and Kingdon2009; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019; Tseng, Reference Tseng1999). What is needed now is a comprehensive and inclusive framework or guidelines which encompass all research aspects of cultural adaptations to ensure appropriate adjustments are being made. Pilot studies which involve stakeholders will provide evidence for relevancy and applicability to minority ethnic populations whilst RCTs will uncover levels of efficacy and fidelity of interventions and outcome measures.

Implications and future directions

The field of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions, including CBT, is an emerging field, and therefore research into the relevancy, fidelity and efficacy of adaptations needs to be carried out to ensure interventions are providing beneficial outcomes for patients. The current political environment is conducive to the implementation of culturally adapted interventions (Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Gerada, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016). Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of adapted interventions using robust designs and improved methods, with the need to compare culturally adapted therapy with non-adapted interventions as opposed to usual care. Most importantly, there is a need to conduct economic evaluation studies to determine how beneficial culturally adapted interventions are compared with standard therapies.

One major gap identified in the literature in relation to adaptation frameworks is the lack of stakeholder involvement during the formulation processes. Very few frameworks incorporated stakeholders but it would be insightful to gain their experience and understanding. Alongside providing a supportive role in framework development, stakeholders could also be involved in the pilot testing through RCTs to ensure applicability and fidelity of the adapted interventions. One way in which this can be done is through implementation mapping (IM) which aims to actively engage stakeholders in the developmental stages of intervention development (Majid et al., Reference Majid, Kim, Cako and Gagliardi2018). There are six main steps which should involve relevant stakeholders to ensure any interventions are adapted to be appropriate for the according patient population and these are: assess needs and barriers, establish objectives, select theory-informed interventions, design and pilot-test the intervention, implement and assess fidelity of the intervention, and evaluate the impact of the intervention (Majid et al., Reference Majid, Kim, Cako and Gagliardi2018). Despite implementing the IM framework in research, over 25% of the reviewed papers failed to include stakeholders; the research that did have stakeholder involvement shared its methodology only half of the time (Majid et al., Reference Majid, Kim, Cako and Gagliardi2018). Likewise, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) reiterates the importance of nested process evaluations to enable better understanding and efficacy of adapted interventions, especially when involving a complex concept such as culture (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009; Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Piper, Richard, Furler, Herrman, Cameron, Godbee, Pierce, Callander, Weavell, Gunn and Iedema2016; Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, 2022). The CFIR outlines five major domains through which patients, as stakeholders, can share their perspectives and experiences which would aid the formulation of culturally adapted interventions (Damschroder and Lowery, Reference Damschroder and Lowery2013). These main domains are: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and the process (Damschroder and Lowery, Reference Damschroder and Lowery2013; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Gerada, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016). Due to the complexity of culture, it is important to have such frameworks and guidelines which provide detailed understanding of how to apply appropriate adjustments and implementations to interventions (Damschroder and Lowery, Reference Damschroder and Lowery2013). Naeem et al. (Reference Naeem, Phiri, Nasar, Gerada, Munshi, Ayub and Rathod2016) have also proposed that the first step of the CBT adaptation process involves stakeholders to enable high-quality, detailed understanding of a culture from the experience and perspective of individuals belonging to that culture.

Currently, there is no agreement on components of cultural adaptation that work. Too many frameworks provide general and often vague guidelines, and few focus on parent interventions or CBT more specifically. Outcome measures and parameters for judging research quality are inadequate for assessing those related to ethnic minority groups due to the ethnocentric environment under which they were developed. There is a need for a universally accepted framework that would ideally be supported by the International Association for CBT to ensure global agreement on adaptation processes. Such a framework can use data from existing literature to provide a common evidence-based framework that could guide clinicians and researchers in adapting different therapies through a standardized procedure. There is also a need for updated high-quality meta-analyses as current literature is almost 10 years old, consisting of various psychosocial therapies from a wide range of theoretical backgrounds. Future meta-analyses should focus on specific ethnic and diagnostic populations, with intervention types sub-analysed, instead of combining participants from various backgrounds and analysing different types of interventions together regardless of their varied theoretical underpinning. In terms of CBT, a framework specific to each element of the therapy would be required. As CBT runs on the three main principles of core beliefs, dysfunctional assumptions, and negative automatic thoughts, it would be necessary for any cultural adaptation guidelines to refer specifically to these elements and how these can be adjusted whilst maintaining fidelity and effective outcomes (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). On a similar note, there are significant differences between various psychological therapies, all of which consist of different underlying principles. It would therefore be impractical to apply one universal framework or guideline to all types of psycho-interventions. On another note, it is important to bear in mind that there are still gaps in the adaptation of outcome measures and their appropriate validation for cultural minorities. For these goals to be accomplished, a diverse workforce is essential for meeting the needs of cultural minorities and providing culturally appropriate mental health services to these individuals alongside implementing culturally sensitive training and supervision to those healthcare professionals working with these populations.

Implications for researchers

-

(1) Research on culturally adapted CBT should be an immediate priority to ensure up-to-date, detailed understanding of the topic area.

-

(2) Researchers need to focus on improving the guidelines for culturally adapting interventions, but also outcome measures.

-

(3) Researchers should also focus on innovative and cost-effective ways to increase the accessibility of culturally adapted CBT.

-

(4) Researchers need to focus on improving current frameworks with the aim of developing comprehensive guidelines on how to conduct research in the field of culturally adapting interventions.

Implications for trainers and supervisors

-

(1) Regular re-assessment and re-examination of the cultural backgrounds of patients to ensure clinicians have up-to-date understanding of the experiences and perspectives of their patients.

-

(2) Ensure psychological intervention aligns well with the patient’s ethnic background through the use of accommodating language and methods, keeping the cultural norms in mind to help formulation direction of sessions as well as treatment goals.

-

(3) Take a sensitive and respectful stance when dealing with cultural issues to help improve patient outcomes and bolster therapeutic alliance; ask for feedback relating to the cultural appropriateness of the adjustment made to the intervention.

-

(4) Clinicians should remain self-aware and recognize their own biases and perspectives that may differ from that of their patients’

Implications for commissioners and managers

-

(1) Where support with mental health services is offered at an occupational level, culturally adapted interventions, especially CBT, are currently not implemented at the organizational level. If there is availability, this has not been shared.

-

(2) There is a need to develop training packages for existing therapists in psychological services to improve their cultural competence in delivering CBT.

-

(3) The routine evaluation of psychological services should include cultural competence in delivering CBT as a regular check to ensure clients are receiving culturally sensitive interventions.

Key practice points

-

(1) This paper has highlighted the need for culturally adapted psychotherapies, especially CBT, to be implemented for individuals of minority ethnic backgrounds as previous research has shown outcomes to be advantageous.

-

(2) The next aim for researchers would be to develop a framework, tested through pilot studies and RCTs, which would aid clinicians in adapting interventions to ensure high outcomes.

-

(3) For CBT therapists, a comprehensive and detailed framework needs to be published which encompasses all elements of culture and its effects on psychopathology and interventions.

Data availability statement

The data used are readily available in the public domain.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Farooq Naeem: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal); Sana Sajid: Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal); Saiqa Naz: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal); Peter Phiri: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal).

Financial support

The research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not for profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.