Given the high rates of trauma exposure (76–100%) and the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in South African adolescents (8–22%)Reference Seedat, Nyami, Njenga, Vythilingum and Stein1–Reference Ensink, Roberstson, Zissis and Leger4 there is an urgent need to provide evidence-based treatments for PTSD. A variety of trauma-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) programmes for PTSD in adults are well established internationally as first-line interventions.Reference Forbes, Creamer, Bisson, Cohen, Crow and Foa5 Similarly, recent meta-analyses of interventions for children and adolescents with PTSDReference Morina, Koerssen and Pollet6, Reference Gillies, Taylor, Gray, O'Brien and D'Abrew7 identified 41 and 14 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), respectively. The studies concluded that trauma-focused treatments can effectively reduce PTSD symptoms and comorbid depression in children and adolescents. Of the studies mentioned in both meta-analyses, only three studies comprised trauma-focused interventions specifically developed for adolescents.Reference Ahrens and Rexford8–Reference Gilboa-Schechtman, Foa, Shafran, Aderka, Powers and Rachamim10 Two of these studiesReference Foa, McLean, Capaldi and Rosenfield9, Reference Gilboa-Schechtman, Foa, Shafran, Aderka, Powers and Rachamim10 provided evidence for the effectiveness of a prolonged exposure intervention tailored for adolescents.Reference Petersen, Lund and Stein11 The lack of mental healthcare specialists at most community level clinics in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) often leads to treatment delays and perceptions by those with conditions that treatments for mental disorders either do not exist or are not accessible to them.Reference Weinmann and Koesters12 The importance of improving investment in and access to mental health services in LMICs is increasingly being recognised.Reference Weinmann and Koesters12

Accessible and effective treatments for common mental disorders such as PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders and substance use disorders, could be provided in community settings by non-specialist health workers (NSHWs).Reference Kilpatrick, Ruggiero, Acierno, Saunders, Resnick and Best13, Reference Cohen14 In many LMICs, including South Africa, there has been a call for integrated community-based mental health servicesReference Petersen and Lund15, Reference Van Ginniken, Tharyan, Lewin, Roa, Meera and Plan16 and the utilisation of trained NSHWs, a practice often referred to as ‘task-shifting’,17 to provide mental healthcare as a strategy to increase access to treatment in the context of the glaring shortage of mental healthcare specialists. There is an urgent need to prioritise RCTs to demonstrate the effectiveness of task-shifted, community-based psychosocial treatment of PTSD in LMICs.Reference Tomlinson, Rudan, Saxena, Swartz, Tsai and Patel18

The effectiveness of prolonged exposure for adolescents (PE-A) compared with supportive counselling using a task-shifting, community-based paradigm was examined. An adult prolonged exposure studyReference Foa, Hembree, Cahill, Rauch, Riggs and Feeny19 found that community-based Master's-level trained counsellors performed equally well compared with specialised psychologists and similarly a pilot and feasibility RCTReference Rossouw, Yadin, Alexander, Mbanga, Jacobs and Seedat20 provided preliminary evidence that both PE-A and supportive counselling can be successfully implemented within a community setting (schools) in Cape Town, South Africa, utilising the services of previously psychosocial-treatment-naive NSHWs. To our knowledge, there are no other published RCTs for the treatment of PTSD in youth in South Africa.Reference Young21 The trial is registered in the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry: PACTR201511001345372 (retrospectively registered on 11 November 2015 as a result of an administrative oversight). Ethics approval and the study protocol were accepted by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (N12/06/031) on 8 August 2012 defining primary and secondary outcomes prior to assessment of the first participant during February 2014 (available at: https://osf.io/ugnsm/?view_only=8479849e340b44de907689f445aaabb2). Study data are available from the authors on request.

Method

Participants

Adolescents aged 13–18 years who had experienced or witnessed an interpersonal trauma and had chronic PTSD (>3 months) recruited from schools around Cape Town, South Africa were included. Adolescents with comorbid mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder were eligible for inclusion, provided that PTSD was determined to be the primary disorder requiring treatment. Adolescents with conduct disorder, primary substance use disorders or psychotic disorders were excluded.

Procedure

The Western Cape Education Department, conditional upon not identifying the participating schools, and the 11 participating school principals provided permission for the interventions to be delivered at the schools. All participating schools were free-tuition schools located in low socioeconomic status communities with an average of 900 students from grades 8 to 12. A recruiter addressed the children during school assembly and classes to provide information on the RCT. Self-referred adolescents completed a PTSD screening instrument. Adolescents who indicated that they had experienced a trauma and whose scores were above the cut-off for inclusion were scheduled for a baseline assessment accompanied by a parent or guardian. The baseline, mid-, post-intervention and 3- and 6-month post-intervention assessments were conducted by two independent evaluators masked to treatment condition; one was an experienced psychiatric research nurse and the other a clinical psychologist with experience in diagnostic interviews.

All primary guardians provided written consent and all participants provided written assent. Participants then completed a 2–3 h baseline evaluation, comprising a clinical interview and self-report measures to assess eligibility and capture baseline information. After randomisation, 1.5 h assessments were conducted at mid-intervention (after five sessions), post-intervention, 3- and 6-months post-intervention and comprised a battery of self-report measures and a clinical interview to determine the presence or absence of a PTSD diagnosis.

Randomisation procedure

Participants who met the criteria for inclusion were randomised to receive either PE-A or supportive counselling using a statistician-generated computer-randomised, parallel, permuted block procedure with six randomisations per block (1:1 ratio). The principal investigator then informed the identified NSHW of the participant's details and treatment assignment who then contacted the school and adolescent to schedule the first appointment.

Sample size

We expected the between-group effects for PE-A and supportive counselling to be comparable with effect sizes that were found in previous trials delivering these treatments to children and adolescents.Reference Foa, McLean, Capaldi and Rosenfield9, Reference Cohen, Deblinger, Mannarino and Steer22 Based on a power calculation, 64 participants would be required to provide 80% power for a two-tailed alpha level of 0.1.

Assessments

The assessment battery was determined during a pilot and feasibility RCT.Reference Rossouw, Yadin, Alexander, Mbanga, Jacobs and Seedat20 It is important to note that the assessment tools administered in this RCT, with the exception of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),Reference Ward, Flisher, Zissis, Muller and Lombard23 have not been psychometrically evaluated and validated in South Africa. The current paper reports on the primary outcome and some of the secondary outcomes relating to PTSD, namely depression and functional impairment, where data were available for analysis at the time of this write-up. Assessment instruments included a demographic questionnaire; this was administered at the baseline assessment to obtain sociodemographic information (such as age, grade, gender and alcohol and drug use history) as well as information about the parents or primary caregivers (such as age, educational level, marital status, income, employment, alcohol and drug use history).

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was measured using the Child PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview (CPSS-I).Reference Foa, Johnson, Feeny and Treadwell24 The CPSS-I is made up of 24-items, 17 of which correspond to the DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD. Each of the 17 items is rated on a scale from 0 to 3; the total score ranges from 0 to 51. This measure is appropriate for children ages 8–18 years. Internal consistency has been found to be good for total and symptom cluster scores in prior studies (Cronbach α ranged from 0.83 to 0.89)Reference Foa, Johnson, Feeny and Treadwell24, Reference Gillihan, AderkaI, Conklin, Capaldi and Foa25 and in the present sample (α = 0.81). Convergent validity is high: the CPSS correlated 0.80 with the Child Posttraumatic Stress Reaction Index. A cut-off score equal to or greater than 11 on the CPSS-I yielded 95% sensitivity and 96% specificity. Test–retest reliability was good to excellent (0.84 for the total severity score, 0.85 for re-experiencing, 0.63 for avoidance and 0.76 for arousal). The CPSS-I was completed by the independent evaluators at pre-intervention as well as at all post-intervention assessments.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were as follows.

(a) The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID).Reference Sheehan, Sheehan, Shytle, Janavs, Rogers and Milo26 The MINI-KID is a semi-structured interview covering current and lifetime disorders. It has excellent test–retest reliability (0.64–1.00). The MINI-KID was used to determine the presence of a diagnosis of PTSD and other diagnoses at baseline. At all post-interventions independent evaluator assessments, the PTSD component was used to confirm the presence or absence of a PTSD diagnosis.

(b) CPSS – Self Report (CPSS-SR).Reference Foa, Johnson, Feeny and Treadwell24, Reference Gillihan, AderkaI, Conklin, Capaldi and Foa25 The CPSS-SR is a self-report version of the scale with psychometric properties that are equivalent to those of the CPSS-I. Diagnostic agreement between the CPSS-SR and CPSS-I is excellent (85.5%).Reference Foa, Johnson, Feeny and Treadwell24, Reference Gillihan, AderkaI, Conklin, Capaldi and Foa25 It was administered at every treatment session to monitor treatment progress and as a self-report measure of PTSD during independent evaluator assessments.

(c) The Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS).Reference Shaffer, Gould, Brasic, Ambrosini, Fisher and Bird27 The CGAS was used by the independent evaluator at pre-intervention as well as at post-intervention assessments to provide a summary measure of functional impairment. The CGAS is appropriate for children as young as 4 and has shown good interrater reliability (r = 0.85).Reference Shaffer, Gould, Brasic, Ambrosini, Fisher and Bird27

(d) BDI.Reference Carey, Walker, Rossouw, Seedat and Stein2Reference Peltzer3, Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelsohn, Mock and Erbaugh28, Reference Beck, Steer and Garbin29 The BDI, which has been normed for adolescents in South Africa,Reference Ward, Flisher, Zissis, Muller and Lombard23 was used to assess depression. Each of the 21 items is rated on a scale from 0 to 3; the total score ranges from 0 to 63. It has good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach α = 0.80), split half-reliability is 0.93 and correlations with clinician ratings of depression range from 0.62 to 0.65.Reference Beck, Steer and Garbin29 It was administered at every treatment session to monitor treatment progress. It was also administered as a self-report measure of depression during independent evaluator assessments.

(e) The Expectancy of Therapeutic Outcome for Adolescents (ETO-A).Reference Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs and Murdock30 The ETO-A assessed participants' expectancy of treatment efficacy by enquiring about the logic of the treatment, its success in reducing trauma-related symptoms and other problems, and the adolescent's confidence in recommending the treatment to others. The ETO-A was completed in the first session after the rationale for treatment was explained.

Other measures included in the full-assessment battery were other psychopathology measures (anxiety and anger), as well as cognition and emotion measures (trauma-related cognitions, self-esteem, social support, resilience and affect regulation). The analysis of these measures was not included here as it was beyond the scope of this paper and will be addressed in a later publication when the 12- and 24-month follow-up results will be reported.

NSHWs

NSHWs volunteered to serve as counsellors for this study. They were qualified psychosocial-treatment-naive nurses undertaking a 1-year advanced diploma in psychiatric nursing at Stellenbosch University (2014, 2015 and 2016). All NSHWs were trained in both PE-A and supportive counselling and provided both interventions in order to counter counsellor effect. New NSHWs were identified and trained every year. This resulted in NSHWs treating no more than four participants each, which meant that they had a similar duration of exposure to, and experience with, both interventions. NSHWs were reimbursed for their petrol/transport costs.

Training and supervision

Training of the NSHWs occurred over 4 days. Three 8 h days were devoted to training in the PE-A protocol and provided by two clinical psychologists (E.Y. and J.R.) with extensive experience in the treatment of PTSD and supervision in prolonged exposure. These sessions consisted of lecture presentations, demonstration video clips and role-play practice of all the treatment components, under supervision of the trainers. An 8 h fourth day was dedicated to supportive counselling training provided by a clinical psychologist (J.R.) with experience in training and supervising the principles of supportive counselling. This was followed by an additional 16 h of supervised role-playing with peers, focusing on empathic responding and non-directive problem-solving skills. Training culminated in the ability to implement PE-A and supportive counselling skills and to follow both treatment manuals.

Supervision of NSHWs was provided by one of the authors (J.R.). This took the format of group supervision with case review of recorded weekly treatment sessions and an opportunity to address both intervention- and participant-related concerns. Individual supervision regarding specific case management issues was available to all NSHWs, as required.

Treatment

The PE-A intervention group

Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD has empirical support in adults in varied populations and contexts.Reference Foa, Hembree, Cahill, Rauch, Riggs and Feeny19, Reference Cahill, Foa, Hembree, Marshall and Nacasch31, Reference McLean and Foa32 PE-A, adapted from the adult protocol, has been shown to be effective in community settings and successfully disseminated to non-specialists.Reference Foa, McLean, Capaldi and Rosenfield9, Reference Gilboa-Schechtman, Foa, Shafran, Aderka, Powers and Rachamim10 In the current RCT, manualised PE–AReference Foa, Chrestman and Gilboa-Schechtman33 consisted of 7–14 weekly, 60 min sessions. Treatment offered eight modules. Homework exercises provided the opportunity to practice outside of the sessions. Module 1 included presentation of the treatment rationale. Module 2 comprised information gathering, identifying the index trauma and conducting a breathing retraining exercise. Module 3 comprised a discussion of common reactions to trauma. Module 4 included a discussion of the rationale for in vivo exposure (confronting trauma reminders in real life), construction of an in vivo hierarchy and assignment of in vivo homework. Module 5 included presentation of the rationale for imaginal exposure (revisiting and recounting the traumatic memory), conducting imaginal exposure for 15–45 min and processing this revisiting experience. This module was repeated for two to five sessions. In module 6, the imaginal exposure focused on the worst moments of the trauma. Module 6 was repeated for four to seven sessions. Module 7 focused on generalisation of skills learned in treatment and on relapse prevention. Module 8 comprised a ‘final project,’ such as making a collage detailing the trauma and the gains made in treatment. The number of sessions required was determined on the basis on an adolescent achieving a reduction of at least 70% on the CPSS-SR. Treatment completers were defined as having completed at least seven sessions, which would have ensured that participants in PE-A treatment received the main components of treatment across the sessions.

The supportive counselling treatment group

Supportive counselling (Cohen JA, personal communication, April 2012), the comparator intervention, is a non-trauma-focused treatment that is based on the traumagenic dynamics model of symptom formation after child sexual abuseReference Finkelhor and Browne34 and the Rogerian psychotherapy modelReference Rogers35 and has been used as an active comparator in other trials of trauma-focused interventions.Reference Foa, McLean, Capaldi and Rosenfield9, Reference Cohen, Deblinger, Mannarino and Steer22 In this RCT, the time-matched supportive counselling manualised programme consisted of 7–14 weekly, 60 min sessions of client-centred therapy. Supportive counselling sessions focused on establishing a trusting, empowering and validating therapeutic relationship. Participants directed the agenda of the sessions and were allowed to choose whether, when and how to address the trauma. In session 1, they were oriented to supportive counselling. NSHWs provided active listening, empathy and encouragement to talk about feelings and express beliefs in participants' ability to cope. Tools such as non-directive problem-solving and keeping a diary were taught.

Treatment integrity

All treatment sessions were video recorded. NSHWs' adherence to the treatment protocols was assessed by reviewing video recordings during weekly supervision sessions. In addition, 10% of treatment sessions were randomly selected for protocol adherence ratings by a trained, independent rater who was not otherwise involved with the study. The rater assessed adherence to both treatments and monitored protocol violations. PE-A and supportive counselling fidelity ratings were based on the number of key elements delivered in the session and scored on a scale of 0–3 (0, very poor; 1, barely adequate; 2, good; 3 excellent).

Data analysis

Linear mixed models (LMMs), using Dell Statistica (2016) were used to analyse the continuous data. The LMMs included all randomised participants regardless of missing data. No covariates were included in the LMM analysis. Possible covariates assessed in preliminary analysis and not included in the LMM (r<0.3) were, age, depression scores, presence of PTSD diagnosis and general anxiety scores at baseline. Effect sizes were calculated for primary (CPSS-I) and secondary (BDI, CGAS, CPSS-SR) outcomes. We obtained 89.42% of the possible assessments for both the primary and secondary outcome variables. This includes participants who dropped out and missing data. LMM results did not vary according to the pattern of missing data.

A ‘good response’Reference Jacobson and Truax36 was defined as a CPSS-I score greater than 2 s.d. below the baseline mean. Fisher's exact tests were used to calculate the proportion of participants meeting this criterion among treatment completers only.

Results

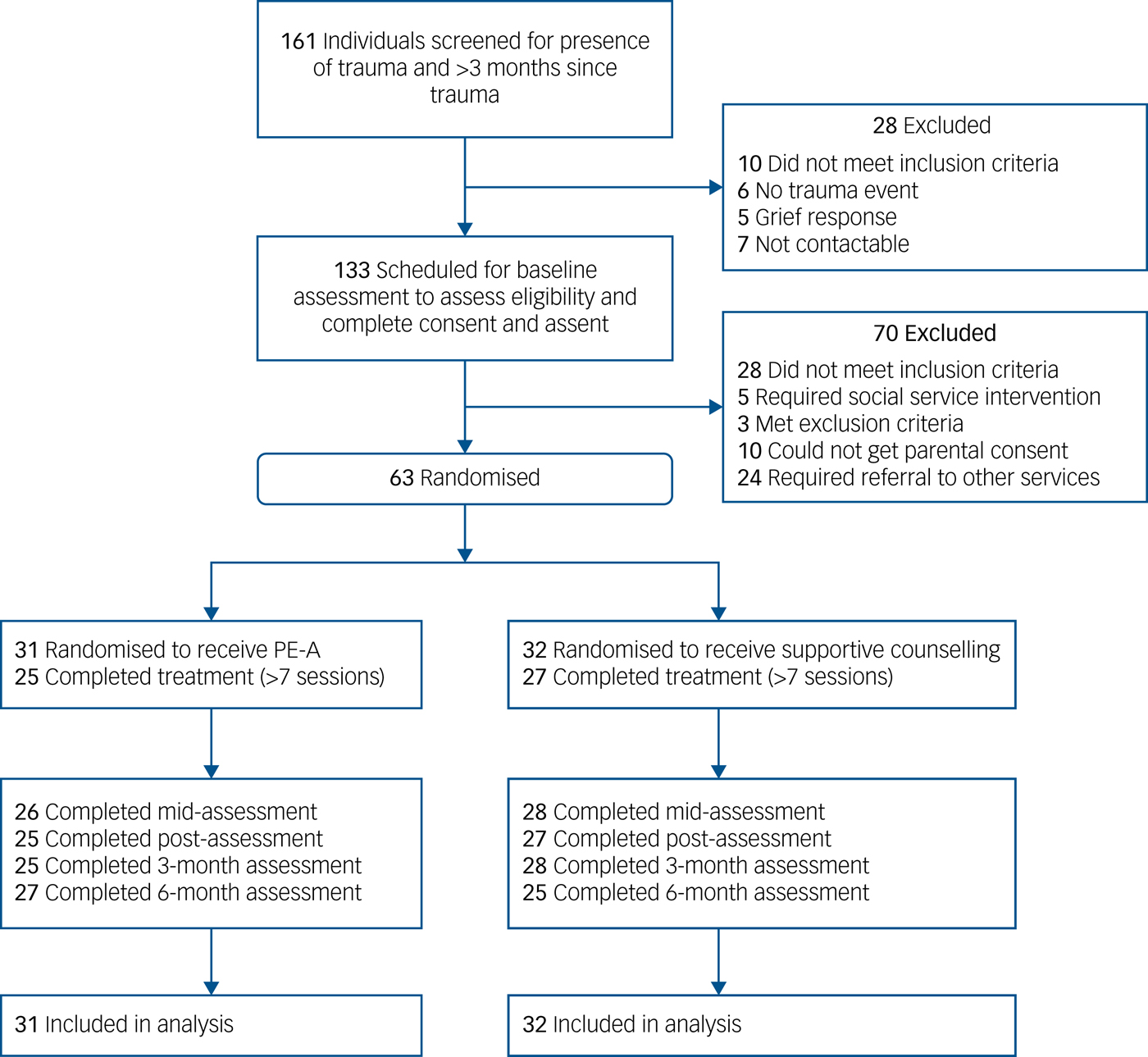

Figure 1 provides an overview of the participant flow through the study. From February 2014 to June 2016, 161 adolescents volunteered to participate in the study. Of these, 133 completed baseline assessments. Sixty-three adolescents were eligible for the study and were randomised to receive either PE-A (n = 31) or supportive counselling (n = 32) and all 63 were included in the analysis.

Fig. 1 Consort flow diagram.

Table 1 provides demographic data for the sample. Participants experienced sexual assault (n = 31, 49.21%), physical assault (n = 12, 19.05%) or witnessed assault (n = 20, 31.75%). Eleven participants (six in the PE-A group and five in the supportive counselling group) did not complete a minimum of seven sessions (P = 0.71) and were, therefore, considered to have dropped out. Expectancy of treatment was similar between the two treatment groups (P = 0.80). A mean number of nine sessions were completed in each treatment arm (Table 1) and the mean session length was 47.78 min (PE-A, 46.55; supportive counselling, 48.87; t = −1.73, P = 0.042). All key treatment components in both protocols were adhered to, with the exception of one of the supportive counselling sessions that was sampled where the NSHW initiated a focus on the traumatic event during the session but did so applying supportive counselling principles. There were no PE-A treatment components included in any of the supportive counselling sessions reviewed, and all PE-A components were appropriately applied in reviewed PE-A sessions. Mean adherence in the PE-A treatment arm was 2.03 out of 3.00 (s.d. = 0). Mean adherence in the supportive counselling treatment arm was 2.00 out of 3.00 (s.d. = 0).

Table 1 Demographic variables for the intent-to-treat sample (n = 61)

PE-A, prolonged exposure for adolescents.

Adverse events

Participants who discontinued treatment did so of their own accord. All of them had a final interview and did not accept alternative treatment or report any suicidal ideation. Adverse eventsReference Duggan, Parry, McMurran, Davidson and Dennis37 were documented in two participants who reported suicidal ideation which, upon investigation, was secondary to interpersonal conflict with a teacher and parent, respectively. Suicide risk was assessed to be low and conflict with the family and teacher was addressed. The adolescents were informed that their counsellors and the principal investigator could be contacted for any crisis outside of weekly treatment sessions. Both participants completed treatment without further incidents. No serious adverse eventsReference Duggan, Parry, McMurran, Davidson and Dennis37 were reported during the RCT.

Acute treatment phase

Primary outcome

Table 2 shows the primary outcome data for both arms. Participants' baseline assessment scores indicated severe PTSD and depression. In both PE-A and supportive counselling arms, there was significant improvement in PTSD symptom severity from baseline to post-treatment (Table 3), as measured by the CPSS-I (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group 28.50, 95% CI 23.11–34.1, P < 0.001, d = 3.81; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group 17.77, 95% CI 12.41–23.1, P < 0.001, d = 1.76). Consistent with our hypothesis, improvement in PTSD symptom severity in the PE-A group was significantly greater than in the supportive counselling group (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group 12.37, 95% CI 6.82–18.17, P < 0.001, d = 1.220.

Table 2 Primary and secondary outcomes at baseline and after treatment

PE-A, prolonged exposure for adolescents; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CPSS, Child PTSD Symptom Scale; CPSS-I, CPSS – Interview; CPSS-SR, CPSS – Self Report; MINI-KID, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale.

a reported for treatment completers

b reported for all participants that completed post-assesments

Table 3 Difference in improvement on primary- and secondary outcomes across assessment points

PE-A, prolonged exposure for adolescents; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; CPSS, Child PTSD Symptom Scale; CPSS-I, CPSS – Interview; CPSS-SR, CPSS – Self Report; MINI-KID, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale.

The proportion of participants who achieved a ‘good response’ (CPSS-I ≤19.62) was significantly greater in the PE-A than in the supportive counselling group (22 of 25 completers (88%); 13 of 27 completers (48.15%), respectively; P = 0.002).

Secondary outcomes

Loss of PTSD diagnosis from baseline to post-treatment occurred in both PE-A (n = 20, 80.0%) and supportive counselling (n = 13, 48%) groups. However, as hypothesised, the percentage of participants who lost their PTSD diagnosis was significantly greater in the PE-A group than in the supportive counselling group (P = 0.017).

The improvement from baseline to post-treatment in self-reported PTSD symptom severity, as measured by the CPSS-SR, for both the PE-A and supportive counselling groups was significant (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group 28.96, 95% CI 23.41–34.51, P < 0.001), d = 3.99; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group 18.34, 95% CI 12.95–23.74), P < 0.001, d = 1.75). As hypothesised, the self-reported PTSD symptom severity improvement in the PE-A group was significantly better than in the supportive counselling group (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group 10.69, 95% CI 4.96–16.42, P < 0.001, d = 1.07).

The pattern in severity of depressive symptoms, as measured by the BDI, was similar. Both groups experienced significant improvement from baseline to post-treatment (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group 24.32, 95% CI 18.18–30.46, P < 0.001, d = 3.18; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group 16.4, 95% CI 10.43–22.37, P < 0.001, d = 1.28). On this measure too, the PE-A group improved significantly more than the supportive counselling group (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group 10.04, 95% CI 3.70–16.38, P = 0.002, d = 0.85).

Improvement in CGAS scores from baseline to post-treatment was significant in both groups (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group 18.05, 95% CI 4.53–21.25, P < 0.001, d = 2.71; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group 19.85, 95% CI 16.60–23.12, P < 0.001, d = 2.97). The PE-A group and supportive counselling group experienced similar improvement in functioning (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group −0.17, 95% CI −3.99 to 3.64, P = 0.93, d = 0.06).

Follow-up phase

Table 2 also shows the outcome data at 3- and 6-months post-intervention. As can be seen, gains were similarly maintained in both groups on primary and secondary outcome measures at 3- and 6-month follow-ups. This was the case for the independent evaluator-assessed CPSS-I (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group at 3 months 29.42, 95% CI 25.23–33.60, P < 0.001, d = 4.11; at 6 months 30.18, 95% CI 26.05–34.31, P < 0.001, d = 4.38; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group at 3 months 22.30, 95% CI 18.29–26.31, P < 0.001, d = 2.19; at 6 months 21.42, 95% CI 17.27–25.58, P < 0.001; d = 2.02). At 3- and 6-month follow-ups, improvement in PTSD symptom severity in the PE-A group remained significantly greater than in the supportive counselling group (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group at 3 months 8.76, 95% CI 3.27–14.25, P < 0.001, d = 0.85; at 6 months = 10.40, 95% CI 4.84–15.96, P < 0.001, d = 1.02). The proportion of participants who maintained a ‘good response’ was also significantly greater in the PE-A group than in the supportive counselling group at 6 months (23 of 25 completers (92%); 18 of 27 completers (66.67%,) respectively; P = 0.04).

A similar pattern was seen for secondary outcome measures. Loss of PTSD diagnosis was maintained in both PE-A and the supportive counselling groups at 3- and 6-months post-intervention (n = 18, 75% and n = 23, 88% in PE-A group, n = 13, 50% and n = 16, 64% in the supportive counselling group), with a significantly greater percentage of participants attaining remission in the PE-A group than in the supportive counselling group (P = 0.05).

Similarly, improvement in PTSD symptoms, as measured by the CPSS-SR, was also maintained in both groups (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group at 3-months 29.34, 95% CI 25.27–33.42, P < 0.001, d = 4.40; at 6 months 29.97, 95% CI 25.96–33.00, P < 0.001, d = 4.67; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group at 3 months 19.84, 95% CI 15.95–23.75, P < 0.001, d = 1.87; at 6-months 20.85, 95% CI 16.80–24.89, P < 0.001, d = 2.12), with a greater reduction in PTSD symptom severity in the PE-A group than the supportive counselling group (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group at 3 months 9.57, 95% CI 4.26–14.88, P < 0.001, d = 0.97; at 6 months 9.20, 95% CI 3.82–14.57, P < 0.001, d = 1.08).

With regards to depression symptom severity (BDI scores) there was maintenance in gains in both groups (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group at 3 months 24.05, 95% CI 20.10–28.01, P < 0.001, d = 3.14; at 6 months 23.83, 95% CI 19.93–27.73, P < 0.001, d = 3.03; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group at 3 months 19.45, 95% CI 15.66–23.23, P < 0.001, d = 1.67; at 6 months 19.14, 95% CI 15.15–23.12, P < 0.001, d = 1.65) but here again gains were significantly greater for PE-A than for supportive counselling (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group at 3 months 6.72, 95% CI 0.93–12.52, P = 0.024, d = 0.69; at 6 months 6.81, 95% CI 0.92–12.69, P = 0.023, d = 0.87).

Improvement in functioning (CGAS scores) from baseline to 3 months and baseline to 6 months was significant for both groups (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group at 3 months 16.32, 95% CI 12.50–19.77, P < 0.001, d = 2.39; at 6 months 15.67, 95% CI 12.34–18.99, P < 0.001, d = 2.18; difference in mean scores in the supportive counselling group at 3 months 17.93, 95% CI 14.70–21.16, P < 0.001, d = 2.45; at 6 months 14.50, 95% CI 11.16–17.84, P < 0.001, d = 2.08). There were similar gains over time maintained in both groups (difference in mean scores in the PE-A group versus supportive counselling group at 3 months 0.20, 95% CI −3.63 to 4.02, P = 0.92, d = 0.10; at 6 months 2.96, 95% CI −0.92 to 6.85, P = 0.13, d = 0.370.

Discussion

Main findings

These findings indicate that both PE-A and supportive counselling are effective treatments for adolescent PTSD, as evidenced by significant improvements on primary and secondary outcome measures. However, participants receiving PE-A experienced significantly greater reduction in PTSD symptoms, were more likely to be ‘good responders’, and to attain remission (i.e. lose their PTSD diagnosis) than those receiving supportive counselling. These results are consistent with the findings of earlier studies,Reference Foa, McLean, Capaldi and Rosenfield9, Reference Gilboa-Schechtman, Foa, Shafran, Aderka, Powers and Rachamim10 where PE-A was found to be superior to a short-term psychodynamic intervention, or to supportive counselling, respectively, in terms of PTSD symptom reduction and associated problems. It is of interest that despite the superior outcome of the PE-A compared with supportive counselling, participants' general functioning, as measured by the CGAS, was not significantly different between treatments, suggesting that receiving either treatment for PTSD was perceived by them as having a positive impact on their everyday functioning.

The second important finding of this study is that both PE-A and supportive counselling could be task-shifted to previously psychotherapy-naive nurse NSHWs, with good fidelity of treatment protocols and retention of NSHWs throughout the trial. In this RCT, we included participants whose index trauma was either a sexual assault, a physical assault or who had witnessed violence or murder. The results of this RCT underscore the generalisability of PE-A as a treatment for PTSD for a wide variety of traumas that are typically experienced by adolescents in community settings. This study confirms that PE-A is effective in addressing PTSD and associated morbidity in adolescents when task-shifted to nurse NSHWs in a low-income South African context. This bodes well for a task-shifted implementation of PE-A in LMIC environments.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the administration of assessment tools that have not been specifically validated in a South African context. Another limitation was the underrepresentation of males in the sample, which could limit the generalisability across gender. Future studies should include more males exposed to physical and sexual assaultive traumas. A further limitation may be the burden of time and effort invested in weekly supervision of NSHWs. However, emphasis on adherence to treatment elements and support of the newly trained personnel to competently implement the interventions will arguable serve to protect against drift and improve the effectiveness and ease of dissemination.

Implications

Despite the clinical complexities of utilising this framework in non-research settings (for example allocation of resources for training, scheduling constraints, added burden), the profound change in symptoms and maintenance of gains seen in adolescents in this study suggests that there may be great benefit in integrating the principles of these treatments in general practice, particularly at primary-care level. A potential future direction would be to scale this up in community and clinic settings, within the paradigm of integrated care, and include a cost-effectiveness evaluation.

Funding

J.R. is supported by Stellenbosch University Rural Medical Education Partnership Initiative (SURMEPI). The trial research is also supported by the South African Research Chair Initiative in PTSD, supported by the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation. J.R. was also funded by the Ithemba Fund and Harry Crossley Fund.

Acknowledgements

Irene Mbanga, Tracy Jacobs and Wendy Rossouw were involved in recruitment and assessment of the participants. We wish to acknowledge their commitment and hard work in making this project possible.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.