Portfolio-based learning is relatively new to medical education and, in many ways, quite far removed from the more traditional instructional pedagogy that has been associated with the education of doctors for centuries. Despite that, the use of portfolios has rapidly expanded in recent years. This increased popularity is clearly set against a background of important changes and new trends in medical education. Before considering further the use of portfolios, it is useful to understand some of these changes as the contextual factors on which the search for new and creative learning and assessment strategies (which include portfolio-based learning) is predicated. I will particularly focus on:

-

1 increasing levels of accountability

-

2 the professionalisation of trainers.

Increasing levels of accountability

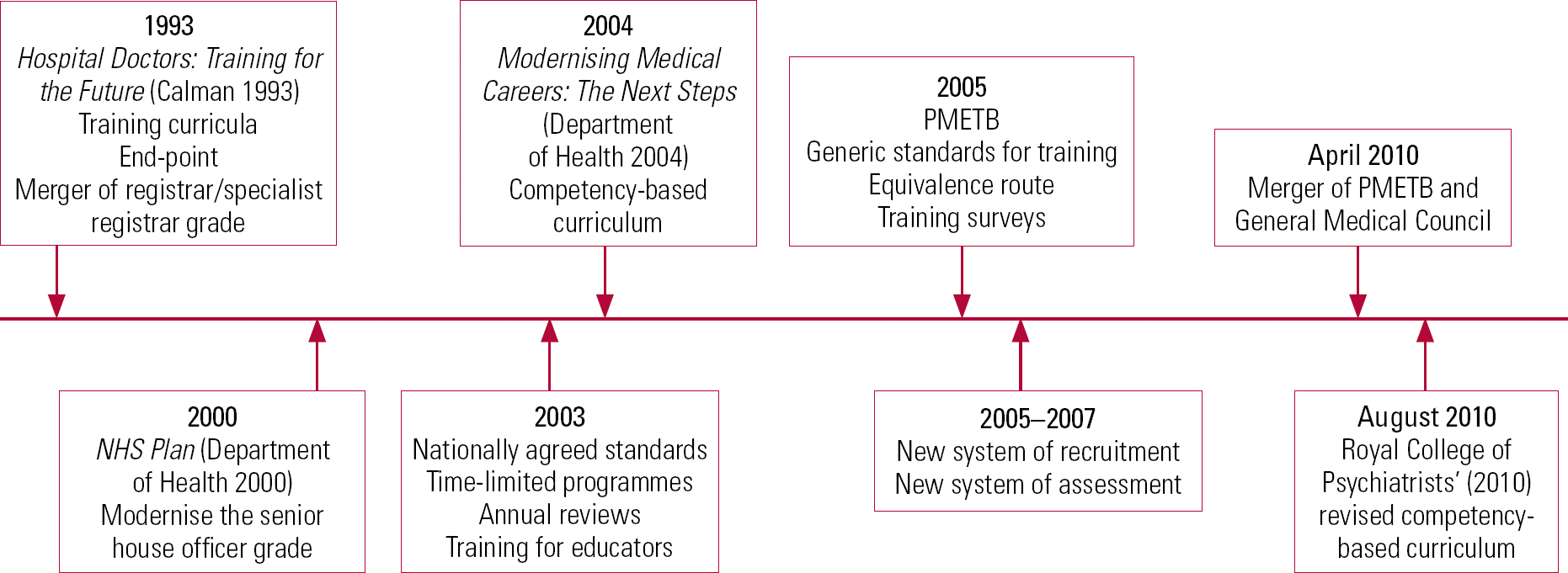

Standards are nothing new in the practice and teaching of medicine. The traditional Hippocratic Oath sets out practical and ethical standards to be upheld by the new physician, as well as a responsibility to teach and pass on the knowledge acquired. However, in recent years the regulation of doctors and the quality assurance of undergraduate and postgraduate medical training and continuing professional development (CPD) have assumed an increasingly high profile in the UK (Fig. 1). It is therefore no surprise that medical education has become ‘a place of increasing accountability and regulation’ (Reference Swanwick, Buckley and SwanwickSwanwick 2010). This process arguably started in 1993, when the Calman Report, Hospital Doctors: Training for the Future (Reference CalmanCalman 1993), recommended significant alterations to medical postgraduate training. Further changes and a clear move towards the establishment of a competency-based curriculum were introduced by Modernising Medical Careers in 2005.

FIG 1 Timeline of changes in medical education. PMETB, Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board.

The Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB) was also established in 2005, drawing attention to learning and assessment in the workplace and external accountability. This focus has been maintained following the merger of PMETB and the General Medical Council (GMC) in April 2010.

Interestingly, Reference WilliamsonWilliamson (2011) argues that a well-maintained portfolio, by providing corroboration of the competencies achieved, also ensures public accountability, as patients can be confident that a doctor's ability to practise against agreed standards has been clearly evidenced.

Professionalisation of trainers

Education has always been an integral part of the working day of a consultant because medical education has rightly been centred on patient care. Nonetheless, as the demands and pressures on senior clinicians rapidly increase, is it feasible to expect that medical educators will simply ‘find’ the time to exercise their role? In addition, as we move away from traditional models of medical education to focus on the process, as well as the content, of learning, can trainers develop a better understanding of ‘how best’ to educate, an area where they have often had little or no training?

The process of formal recognition of trainers, which will effectively ‘professionalise’ the role of large numbers of medical educators, presents both challenges and opportunities to address some of these dilemmas. Under the powers of the Medical Act 1983, the GMC, through the Deaneries, has been responsible for the selection and accreditation of general practitioner (GP) trainers for a number of years. This approach has had a very positive impact on the quality of training for GPs and provides a useful template for postgraduate medical training in other specialties.

The Patel Review (General Medical Council 2010) suggested that ‘the GMC should develop a framework for the accreditation of trainers’; after extensive consultation, a proposal to enhance the process of recognition for non-GP trainers has been finalised (General Medical Council 2012a). The new arrangements will be in place from 2013/2014 and will require postgraduate deans and medical schools to formally recognise medical trainers undertaking these specific roles:

-

• undergraduate education

-

• those responsible for overseeing students' progress at each medical school

-

• lead coordinators at each local education provider

-

-

• postgraduate training

-

• named educational supervisors

-

• named clinical supervisors.

-

What is (and what is not) a portfolio?

A portfolio can be generally defined as:

‘a purposeful collection of student work that exhibits the student's efforts, progress, and achievements in one or more areas. The collection must include student participation in selecting contents, the criteria for selection, the criteria for judging merit, and evidence of student self-reflection’ (Reference Paulson, Paulson and MeyerPaulson 1991: p. 60).

In its widest use the term portfolio has come to encompass a number of commonly used tools in the education and career development of doctors, despite the significant differences in structure and purposes. Therefore, a portfolio is not the same as:

-

• a logbook, which simply records specific activities undertaken

-

• a CV, which just provides a summary of an individual's employment history and qualifications

-

• a course log, which records training and targeted activities for a specific course

-

• a training folder, which collects evidence of participation in training (e.g. certificates, programmes).

Reference Snadden and ThomasSnadden & Thomas (1998) provide a useful description for portfolios in postgraduate medical education as ‘a documentation of learning and an articulation of what has been learned’. These authors suggest that a portfolio can include some of the things listed above as long as the learner also provides written reflective accounts of the events documented, reflections on problem areas, what has been learnt and plans for how new learning needs will be tackled.Footnote †

Although a number of other different descriptions are available, it is clear that portfolios provide the best educational value for any learner when the following are achieved:

-

• the learner takes full responsibility for the creation and the development of the portfolio

-

• the portfolio contains an account of the learning that has taken place as well as an articulation of what has been learnt

-

• the learner's portfolio is reviewed with another individual (a supervisor, a peer, etc.) who can provide feedback

-

• the portfolio is closely linked to the learner's professional development plan.

Other professional groups have successfully used portfolios as part of their systems for accreditation and continuing education. For example, nurses and midwives consistently rely on the use of professional portfolios to evidence their skills and to support their career development. This process is helpful both in the pre-registration stage, to demonstrate the achievement of competencies set out by the Nursing and Midwifery Council, and in the post-registration stage, to show a commitment to ongoing learning and CPD.

Writing about their use in the nursing profession, Reference NeadesNeades (2003) points out that portfolios can help accomplish three important outcomes:

-

• ownership of learning

-

• bridging of the theory–practice gap

-

• development of reflective learning.

Portfolios are also useful springboards for the sort of experiential learning which is often associated with Kolb's learning cycle (Reference KolbKolb 1984): a model of continuous spiral learning is presented, constantly moving between the realm of concrete experience, through observations and reflections on that experience, to abstract concepts (the theory), which are then tested, evaluated and redefined on the basis of further experience.

Reference ClarkeClarke's (2010) suggestion of the use of practice notes (Box 1), although mainly directed at nurses, is a useful example of how the above outcomes can be achieved in everyday practice. Similarly, the Royal College of Psychiatrists' (2012) reflective templates for critical (significant) events (Box 2) provide a clear direction for any psychiatrist on how to begin to develop a portfolio that can be used as a reflective tool, linking theory to practice, as well as for revalidation purposes.

BOX 1 Using practice notes in a portfolio

A practice note is a way of describing experiences in everyday practice and what has been learnt from them, using the following three questions:

-

1 What have I done today in terms of patient care activities or team activities?

-

2 What have I learnt today about:

my approach to …?

how much I know about …?

how skilled I am becoming in …?

-

3 What do I need to do now to enhance my knowledge, skills or approach?

(Adapted from Reference ClarkeClarke 2010)

BOX 2 Significant event audit – structured reflective template

What happened? (Describe the significant event and the context for it)

I work with a team providing specialist mental health services to adolescents in the care of the local authority. These young people have had very unsettled lives, disappointing or abusive experiences with their families, and find change very unsettling. Our team is commissioned to see young people up to their 18th birthday and the transition to adult mental health services is often difficult.

A number of our patients experience crises just before or after their 18th birthday. One of our patients was admitted under section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983 a week after their 18th birthday.

What could have been done better? (Identify triggers and opportunities for better practice)

Despite the fact that our team had made efforts to link up with adult mental health teams, our patients often voice concerns at the prospect of working with a set of different professionals. In response to our request for transfer, the adult team had been hesitant and unclear about their potential role.

What changes have been agreed? (Identify opportunities for learning and actions to be taken forward)

Personally

Although I was aware of the difficulties of the transition process, this case highlighted the need to focus on the ending process much earlier in the work.

For the team

We have now put in place an even tighter process for transition to adult mental health, which includes a series of meetings with the prospective key worker in the months leading up to the 18th birthday, so that the young person can become familiar with the new treating team. We have also undertaken an audit of cases transferred and presented the results to colleagues in adult mental health to highlight potential difficulties and practice issues.

What is the educational value of a portfolio?

Reference SwanwickPitts (2010), referring to the growing literature on the use of portfolios, identifies six main purposes:

-

1 CPD

-

2 enhanced learning

-

3 assessment

-

4 evaluation

-

5 certification and re-certification

-

6 career advancement.

These items clearly have overlapping scopes and I will summarise them into two broad areas of assessment and reflection.

A portfolio as an assessment tool (formative and summative)

‘The whole discussion about scoring, marking and standard setting is in fact all about finding the best possible way to throw away a substantial amount of measurement information.’ (Reference Schuwirth and van der VleutenSchuwirth 2006: p. 297)

The above quotation highlights some of the difficulties of using traditional psychometric methods in the assessment of doctors' competence and performance. As it is increasingly recognised that valid assessment methods cannot rely just on the testing acquisition of knowledge and the reproduction of facts, portfolios have been put forward as a useful alternative.

Reference Sturmberg and FarmerSturmberg & Farmer (2009: p. e86) suggest that an ‘assessment should aim to test or closely approximate the learner's capabilities, i.e. the attributes that the learner should demonstrate in actual clinical practice’. Consequently, they advocate the use of portfolios as a flexible and reliable way to demonstrate:

-

• clinical capability – as this is a reflection of a very complex interaction between knowledge, skills and attitudes, it is arguably best demonstrated through a gathering of ‘real practice’ examples such as patient letters, records of case-based discussions and peer-review meetings;

-

• reflective abilities – the building of the portfolio is predicated on the process of reflection, both at the beginning (in the purposeful and attentive collection of the actual material) and throughout the process when further learning needs can be identified on the basis of gaps, challenges and difficult encounters in clinical experience;

-

• organisational capability – these are the domains of practice often referred to as non-technical or non-clinical skills (e.g. leadership, the ability to work effectively as part of a team, awareness of one's role in a complex organisation). These skills, which underpin and enhance any practitioner's technical skills and underline successful performance, are undoubtedly essential to mental health practitioners but notoriously hard to measure with traditional assessment tools. A portfolio has the significant advantage of incorporating elements of feedback which most closely reflect achievement in these areas of professional practice.

Portfolios have high face validity when used for formative and developmental assessments and this is probably the more widespread and uncontested use of portfolio-based learning.

Despite the advantages highlighted above, the use of portfolios for summative assessments in medical education is still relatively untested and a number of potential difficulties are reported in the literature.

Reference Snadden and ThomasSnadden & Thomas (1998), on the basis of the findings of their study on portfolio learning in general practice vocational training, urge caution against portfolio-based summative assessment. This is because the presence of high-stakes external monitoring might fundamentally alter the nature and content of the material learners might include in a portfolio, at the expense of any problem areas or examples of ‘less than excellent’ practice, the very areas one would wish to usefully focus on in a formative, reflective portfolio.

In addition, as Reference ChallisChallis (1999) points out, ‘the highly individual nature of each portfolio means that their assessment can present as many challenges as the building of the portfolio itself’ (p. 375). Therefore, issues concerning interrater reliability (how the scores of different examiners correlate), variability of content (how much freedom the learner should be allowed in the choice of content) and criterion-related validity (how portfolio-based assessments compare with other forms of assessment) are often quoted as barriers to a more widespread introduction of portfolio-based summative assessments.

A portfolio as a tool to enhance learning and reflection

The process of reflection is a cornerstone of adult learning and, for medical practitioners, the necessary link between the academic knowledge acquired during years of rigorous training and the day-to-day experience of dealing with patients' illness and suffering. An often quoted analogy by Reference SchonDonald Schon (1984: p. 42) clearly illustrates the challenges of translating theoretical, evidence-based, technical solutions (what Shon describes as ‘the high ground’) to complex encounters with patients, the ‘swampy lowlands of practice’. Portfolio-based learning has clear value in helping practitioners develop that link, create a bridge between theory and practice, encouraging further learning that arises directly from dilemmas in clinical practice. As Reference ChallisChallis (1999: p. 371) points out:

‘the building of the portfolio itself requires engagement in a process of reflection and critical self-awareness. Its creation therefore constitutes an educational process, and this aspect needs to be recognised over and above the outcomes of learning that are identified and evidenced in the physical material contained in the portfolio.’

The examples in Boxes 2 and 3 use different approaches to illustrate the value of a reflective portfolio in promoting improvements in clinical practice and learning from challenging situations. By stimulating reflection and self-analysis, a portfolio provides the additional benefit of highlighting gaps in skills and knowledge, prompting practitioners at every level of experience and training to find creative solutions to address them.

BOX 3 Reflective note on a clinical case using the patient's unmet need/doctor's education need approach

Case synopsis

Patient B is a young person with symptoms of depression, self-harming behaviour and anger outbursts. Antidepressant medication has led to an improvement in mood but has not significantly affected other presenting complaints.

Patient unmet need (a clinical event that challenges your current practice)

The patient has requested a review of their diagnosis, looking for a better explanation for the serious difficulties.

Doctor's educational need (an identified learning need arising from practice)

I am considering an additional diagnosis of personality disorder but I have not yet discussed this with the patient or their family. I am aware of the controversial nature of this diagnosis and the issue of applying it to young people. I do not often use this diagnosis.

Actions to be taken forward

I will discuss this case in our peer supervision group to hear about colleagues' experiences, whether they are using this diagnostic category, how they are discussing and presenting it to young people and their families. I also plan to:

-

• do a literature search

-

• look for useful information leaflets

-

• discuss with the young person and their family.

How are portfolios currently used in the professional development of doctors?

Foundation training

All doctors in foundation training have access to an electronic portfolio, which is used as evidence of satisfactory learning and generally includes the following:

-

• a personal and professional development plan

-

• records of meetings with educational and clinical supervisors

-

• workplace-based assessments

-

• reflections on clinical work

-

• sign-off documents.

Some of the tensions, as well as the benefits, of using a portfolio are highlighted in this quote by a foundation year 1 doctor:

‘Finally, the temptation is to fill in the portfolio because it's a requirement, and you're running out of time by the end of the year. But this is something to be proud of, and ultimately should be a personal log of what you've become since passing medical school – a competent doctor’ (Reference MooreMoore 2010: p. 20).

Specialist training

Portfolios, often in an electronic format, are used to support and monitor the educational progress of doctors in a range of specialist training programmes.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists also has an online portfolio online and all doctors in training are registered with it, as it supports the Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP). This is a mandatory process that reviews the ongoing progress of doctors in training through a portfolio of evidence which is gathered in a structured way by the trainee and evaluated by a panel. An enhanced ARCP process, with clear responsibilities for the doctor in training, the responsible officer (the Postgraduate Dean, in England, or equivalent role in the other UK countries) and the employing organisation will be the vehicle for the revalidation of doctors in training (General Medical Council 2012b).

The ‘seasoned’ practitioner

In its revised CPD policy, the Royal College of Psychiatrists encourages a portfolio-based approach with self-accreditation as well as peer reviewing and external audit of annual returns (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2013). Along similar lines, the GMC's guidance for CPD (General Medical Council 2012c) also provides a good framework to think about the ongoing needs of doctors in a way that is both practical and reflective.

A model of portfolio-based accreditation, with a rolling 3-year cycle of review, is promoted by the London Deanery's Professional Development Framework for Supervisors. It applies to all named supervisors (clinical and educational) within a trust or local education provider, with the Director of Medical Education being responsible for the quality control of this process. This is in line with the GMC guidance on the accreditation of trainers (General Medical Council 2012a).

Most importantly, the process of revalidation is likely to become a key driver for the use of portfolios by medical professionals. This is because the suggested approach to revalidation is dependent on a system of annual appraisals based on the Good Medical Practice Framework (General Medical Council 2013) and it will therefore strongly rely on the doctor's ability to provide relevant supporting information in a structured and well-thought-out portfolio. This is not intended as a mere collection of evidence of the doctor's achievements – GMC guidance (General Medical Council 2013) clearly highlights the importance of the reflective process which underpins the development of any worthwhile portfolios:

‘When you are preparing for your appraisal and collecting supporting information, you should review your practice and consider how the supporting information can demonstrate that you are continuing to meet the principles and values set out in Good medical practice […] In most cases, your appraiser will be interested in what you did with the information and your reflections on that information, not simply that you collected it and maintained it in a portfolio. Your appraiser will want to know what you think the supporting information says about your practice and how you intend to develop or modify your practice as a result of that reflection’ (p. 1).

In its own guidance on revalidation, the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2012) provides a detailed list of the sort of supporting information psychiatrists ought to include in their portfolio.

It is useful to consider the potential difficulties of introducing portfolios to experienced practitioners, as on one hand they are less likely than trainees to be familiar with their use, and on the other they may be required, at any time, to maintain three different ones concurrently:

-

1 a CPD portfolio

-

2 a supervisor's portfolio (for those in educational roles)

-

3 a revalidation portfolio.

In terms of the specific challenges for psychiatrists, the Royal College of Psychiatrists' and GMC's recommendations about the intents and purposes of such portfolios share a clear emphasis on the value of reflection, learning from experience and multisource feedback. However, a number of details about overlapping information (e.g. Is the CPD portfolio just a subsection of the revalidation portfolio? How much of the information in the supervisor's portfolio is repeated in the CPD portfolio?) and overlapping roles (e.g. Is the Director of Medical Education performing the same role of the responsible officer in appraising supervisors? How does the 3-yearly educational appraisal for supervisors relate to the general appraisal, given that most consultants also have supervisory roles?) are still left to be debated at local levels.

Practical considerations

Although it is clear that a number of developments in educational theory underpin the value of portfolio-based learning, the introduction of portfolios in the medical profession has been met by mixed responses. For example, a study assessing the knowledge, attitudes and pattern of use of portfolios by psychiatric trainees (Reference Seed, Davies and McIvorSeed 2007) showed that although doctors' attitudes to the use of portfolios were broadly neutral, their understanding of their actual purpose and benefits was very limited. Relatively few trainees had included in their portfolios examples of reflective practice, despite the available evidence that portfolios are probably most effective as reflective tools. Similarly, a more recent study of psychiatric trainees' views on portfolios (Reference Halder, Subramanian and LongsonHalder 2012) shows large variations in the use and appreciation of the usefulness of this learning tool.

A systematic review of the use of portfolios (Reference Driessen, van Tartwijk and van der VleutenDriessen 2007) highlights a number of potential issues which may account for the ‘mixed success’:

-

• poor introduction

-

• time constraints

-

• lack of clarity about structure

-

• lack of adequate support

-

• the issue of assessment.

These issues are echoed by Reference McKimmMcKimm (2001). In her review of the literature about portfolios carried out between October 2000 and January 2001, she identified the following potential disadvantages:

-

• keeping a portfolio is a time-consuming process for learners and teachers

-

• care must be taken in clearly defining the purpose and boundaries

-

• mentors/facilitators/tutors must be trained

-

• if a portfolio is used in a summative assessment, then issues of ownership (in reference to the potential issue of plagiarism), reliability and validity must be considered and robustly addressed

-

• learners often do not see the direct relevance of reflective learning to their practice.

Some of the cautions about the use of portfolios as summative assessment tools will undoubtedly apply to revalidation portfolios, particularly with regard to the nature and content of the material included. This will only partially be chosen by the doctor, who will have to engage with a variety of service-related information that does not always reflect individual performance (e.g. DNA data and cancellation reports, data on outcome measures, bed usage, and serious untoward incidents) and a range of organisational priorities affecting individual performance (staffing levels and funding, support for developmental activities in job plans, etc.).

It has been proposed that some of the practical challenges can be overcome by the use of e-portfolios; for example, having access to electronic devices for timely recording is known to increase the frequency of reflection (Reference Macaulay and WinyardMacaulay 2012). This is indeed promising but the expectations about accessibility and functionality cannot be underestimated, as highlighted by Reference PathirajaPathiraja (2012):

‘the ePortfolio is far from perfect. The end user is typically generation Y and expects technology to have the beautiful aesthetics and seamless functionality of their i-products.’

Significant investment and wide consultation with potential users will be required to address some of these issues. The Royal College of General Practitioners, for example, in response to practical concerns raised by trainees and trainers, will significantly change the functionality of their 5-year-old trainee e-portfolio from August 2013. In addition, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, alongside a cohort of other medical Royal Colleges funded by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, is developing an e-portfolio to support UK doctors through their appraisal and revalidation; the project is currently in the testing and approval phase, which is involving a number of doctors as potential users, and it is envisaged that the e-portfolio will be launched by the end of 2013.

Conclusions

A portfolio-based approach fits very well with ideas about adult learning; a well-maintained portfolio, by allowing the learner to retain a high degree of flexibility and control over their own learning, is clearly one of the educational strategies that promote the development of self-directed learning. Although the reliance on the learner's ability to identify and effectively address learning needs has been questioned (Reference Davis, Mazmanian and FordisDavis 2006), a number of other sources for their identification are recognised in the literature, including peer review, external observation, gap or discrepancy analysis. All of those methods, alongside self-assessment and self-direction, strengthen and complement a portfolio-based approach to learning and would enhance any professional portfolio.

Barriers to the use of portfolios, both practical and ideological, are often quoted. This is despite the trend towards their increasing usage, which is based on sound educational principles and, most importantly, mirrors changing values and expectations about training, assessment and CPD within the profession and among the general public.

Although there are clearly no straightforward answers for these dilemmas, it is important for all psychiatrists to actively seek to engage in this dialogue about changing values and expectations, as suggested by Reference BhugraBhugra (2008: p. 282):

‘In the 21st century, it is only appropriate that psychiatry as a profession revisits what society expects from the profession and in turn what we expect from society. Complacency, paternalism, arrogance, inability to self-regulate and poor leadership have no place in our profession.’

The use of portfolios as an example of ‘authentic’, real-life assessments gives us yet another opportunity to do just that. In addition, the use of portfolios calls for medical educators to rethink some of the paradigms on which traditional examinations and appraisals have been based, to make room for a different set of educational values and prioritise learning from reflective practice which ‘accepts the subjectivity of data and interpretations, and focuses on individual insights and developments […] values creativity and, importantly, allows and understands the possibility of being wrong’ (Reference SwanwickPitts 2010: p. 104).

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The educational role of the following group of professionals will need to be formally recognised through a portfolio-based approach:

-

a named clinical supervisors

-

b clinical directors

-

c training programme directors

-

d college tutors

-

e clinical tutors.

-

-

2 A portfolio can be defined as:

-

a a logbook, recording specific activities undertaken

-

b a CV, providing a summary of an individual's employment history and qualifications

-

c a purposeful collection of student work that exhibits the student's efforts, progress and achievements, and includes student participation in selecting contents, the criteria for selection, the criteria for judging merit and evidence of student self-reflection

-

d a course log, recording training and targeted activities for a specific course

-

e a training folder, collecting evidence of participation in training (e.g. certificates, programmes).

-

-

3 In the literature, the following has not been identified as the main purpose of the use of portfolios:

-

a enhanced learning

-

b evaluation

-

c incident reporting

-

d certification and re-certification

-

e career advancement.

-

-

4 The following difficulty has not been encountered when using portfolios for summative assessments:

-

a interrater reliability

-

b variability of content

-

c criterion-related validity

-

d increase in pass rates

-

e reduces reporting of problem areas.

-

-

5 The e-portfolio of a foundation trainee will generally not include:

-

a a personal and professional development plan

-

b records of meetings with educational and clinical supervisors

-

c workplace-based assessments

-

d reflections on clinical work

-

e personal correspondence.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | a | 2 | c | 3 | c | 4 | d | 5 | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.