Introduction

In Fiji, Ghana, Jamaica, and the Maldives, the tourism sector is an important source of economic wealth. For example, in the Maldives tourism accounts for around a quarter of total GDP and is a main source of employment (Meierkord, Reference Meierkord2018: 5). Similarly, the role of tourism as one of Jamaica's main industries has been stated in Deuber (Reference Deuber2014: 29), and Hundt, Zipp and Huber (Reference Hundt, Zipp and Huber2015: 691) also mention that tourism is one of the key industries and employment sectors in Fiji. While many of these destinations use traditional channels of advertising such as print magazines, a considerable amount of advertising is carried out online via social media.

The increased popularity of social media websites such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter has brought with it an attendant interest in how language, specifically English, is used in these contexts (cf. Seargeant & Tagg, Reference Seargeant and Tagg2014). However, with a few exceptions (cf. Lee, Reference Lee, Seargeant and Tagg2014; Shakir & Deuber, Reference Shakir and Deuber2018), social media studies tend to overlook social media language in what Kachru (Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985) calls Outer Circle countries.

In this paper, we examine how English and other languages are used in tourism advertisements on Instagram in four different countries in which tourism plays an important role, i.e. the Maldives, Fiji, Ghana, and Jamaica. Specifically, we investigate the range of languages used in Instagram posts in advertisements geared towards tourists from these destinations. We consider the effect of the use of different languages in these posts, and we investigate how features typical of social media, specifically hashtags, are employed in tourism advertisements on Instagram. The paper begins with a brief overview of the role of English in each of the selected territories, before moving on to contextualise these varieties in terms of major models of World Englishes. The data and methods used in this study are then presented, followed by the quantitative and qualitative results.

World Englishes and online tourism advertising

Ghana is a multilingual country in which over 80 indigenous languages are spoken (Adika, Reference Adika2012). English is used as the primary medium of instruction in schools, and is also widely used in the news media, government (Huber, Reference Huber and Mesthrie2008: 73), and as a language of cross-ethnic communication (Adika, Reference Adika2012: 152). In spite of the predominance of English, Ghanaian languages are actively promoted in television and radio media and Ghanaian identity is closely linked to the ability to speak a Ghanaian language. In addition, Ghanaian Pidgin English is also spoken as a lingua franca and is a marker of local identity.

In Fiji, English was introduced in the late 19th century in the course of colonisation and is currently a second language variety that has been institutionalised (Hundt et al., Reference Hundt, Zipp and Huber2015: 690). As a consequence of the establishment of sugar plantations and the recruitment of indentured labourers from India, English has been in contact with other languages for a long time. English can be found in domains such as administration, the education system, and the media. Furthermore, English is used as a lingua franca between different ethnic groups (ibid.) Apart from English, the other two main languages spoken in Fiji are Fijian and Fiji Hindi (Schneider, Reference Schneider2007: 116).

In Jamaica, a local emerging variety of Standard English, Jamaican English (JE), is spoken alongside an English-lexicon Creole, Jamaican Creole (JC). Since English is Jamaica's official language, JE is widely used in formal domains such as government, education, and the media, while JC is relegated to private and informal domains. However, in recent times the division has been less clear-cut, and JC is increasingly used in contexts that were previously reserved for JE, particularly news media (Westphal, Reference Westphal2017). JC is an important marker of local identity and group membership and can increasingly be heard in political speeches and campaigns.

The only official language in the Maldives is Dhivehi. English does not have the status of an official language and is therefore absent from the domains of administration, law, and politics. However, English is employed in education, the media, and tourism, and is also frequently used in the workplace (Meierkord, Reference Meierkord2018: 4–5). The importance of Islam and the Qur'an in the country suggests that some Maldivians have command of Arabic.

Though several models have been proposed for describing World Englishes and the ways in which they relate to one another, the older models, such as Kachru's (Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985) Three Circles Model and Schneider's (Reference Schneider2007) Dynamic Model, do not allow us to study the varieties at hand on equal terms. For example, in the Kachruvian model, Fiji, Ghana, and Jamaica are traditionally placed in the Outer Circle, whereas the Maldives would fall into the Expanding Circle. In reality, the Maldives appears to be transitioning from the Expanding to Outer Circle, and Meierkord (Reference Meierkord2018: 2) notes that the Maldives represents ‘a rapidly transforming society, in which English is fast establishing itself as a second language in large parts of the population’. Similarly, while Fiji, Ghana, and Jamaica (as former colonies) can be dealt with in Schneider's postcolonial model, the Maldives have never been a colony, and the development of English there differs considerably from the three postcolonial Englishes because of the lack of a settler population (Meierkord, Reference Meierkord2018: 4). Consequently, a key component of Schneider's (Reference Schneider2007) Dynamic Model is missing.

Buschfeld and Kautzsch's (Reference Buschfeld and Kautzsch2017: 113) Extra- and Intra-territorial Forces (EIF) Model makes use of the ‘notion of extra- and intra-territorial forces’ that are at work at all times in the development of postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes. The pair propose that tourism, as a largely extra-territorial influence, might be a key factor in the expansion and development of English, particularly with respect to the general role of tourism in a given country. They also acknowledge an intra-territorial dimension, especially ‘with respect to the question of how readily a country's inhabitants make use of English in interchanges with tourists’ (Buschfeld & Kautzsch, Reference Buschfeld and Kautzsch2017: 115).

In each of the countries studied here, English is the main language of tourism, and has become ‘the default language of choice for brochures, signposts, websites and other text-based information material for tourists’, as well as the main language for spoken interaction with tourists (Schneider, Reference Schneider2016: 2). In spite of this, local languages remain central to tourists’ travel experience in another country. Jaworski and Thurlow (Reference Jaworski, Thurlow and Coupland2010: 262) note that ‘tourist consumption is organized around the recognition and interpretation of various signs’ and that ‘[t]hese signs are frequently linguistic’. In their study of a guided tour in the Maori village of Whakarewarewa, Rotorua, NZ, the authors demonstrate that it is the place name itself that is the object of tourist consumption. Similarly, we could say that Instagram users adopt the tourist gaze when they look at pictures of beautiful scenery or cultural artefacts in the posts that are offered by tourism organisations online. Together with expressions in local languages, Instagram posts may constitute objects of tourist consumption.

In advertising too, English is one of the most frequently used languages. Even in countries where it is not spoken as a first language, English has become associated with modernity and globalisation (Piller, Reference Piller2001: 161). A country that advertises in English may draw tourists from all over the world who use English as a lingua franca. English use is not restricted to Standard British or American English and television advertisements in particular employ different varieties of English (Bhatia, Reference Bhatia, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020). The mixing of English with local accents and words is meant to heighten trustworthiness (Bhatia, Reference Bhatia, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020: 625), but it also lends the advertisement an exotic flavour. As in tourism, English in advertising often appears with other languages. Outer and Expanding Circle countries are most likely to use English for products and company names (Bhatia, Reference Bhatia, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020: 621), but English is not usually used for traditional concepts (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 383). This suggests that while English plays an important role as a lingua franca, local identity is indexed largely via local languages.

Finally, hashtags ‘have become an integral part of social media communications’ (Rauschnabel, Sheldon & Herzfeldt, Reference Rauschnabel, Sheldon and Herzfeldt2019: 473), found on virtually all social media platforms, including Instagram. A hashtag ‘acts as a form of metadata labelling the topic of the posts so that it can be found by others’ (Zappavigna, Reference Zappavigna, Seargant and Tagg2014: 139). In her analysis of tweets about coffee, Zappavigna (Reference Zappavigna, Seargant and Tagg2014: 148) demonstrates that the ‘#coffee hashtag plays an important role in aligning users into communities of shared values about coffee’. Similarly, hashtags around topics such as travel, safety, or specific tourism destinations may serve a similar function in ‘proposing interactive bonds’ (ibid.: 142).

Data and method

The data here comprise Instagram posts created by tourism organisations from the Maldives, Fiji, Ghana, and Jamaica during the period March to June 2020. For each of the countries, we collected 20 Instagram posts from Instagram accounts such as Tourism Fiji, Visit Maldives, Visit Jamaica, and Ghana Tourism Authority, all pages hosted by the official tourism authorities of the respective countries. In addition to these, posts from official airlines such as Fiji Airlines were used. A selection of these posts is reproduced below. Since Instagram's fair use guidelines (Instagram, 2021) allows for the use of copyrighted work for education and research purposes, and since all the posts used were public, i.e. visible even to people without Instagram accounts, we are confident that the reproduction of posts should not raise any ethical concerns. In line with these fair use guidelines, we limit ourselves to text posted by the owners of the account, and do not make reference to comments made by Instagram users on each of the posts. Although Instagram is primarily a photo-sharing app, the focus of this paper is on language use. Specifically, we focus on the range of languages used in online contexts by authors producing texts in multilingual settings.

In the first phase of analysis, a total word count for the posts of each variety was calculated. Word counts included text captions, texts in pictures that were posted alongside the text, mentions, links, numbers, and hashtags. Since in the lattermost case, there are typically no spaces between words, as in #visitjamaica, each hashtag was counted as one word. In addition, words written in non-Roman scripts, such as Arabic, were included. Emoticons are comprised of different elements of punctuation and so these were excluded from the word count. Our analysis only considers the words written by the post author in the original public post and in original post captions. This is in keeping with Instagram fair use regulations. Content generated by private individuals is not included.

Each word was then coded into one of five categories. The first of these was Standard English, used for forms that were written in Standard formal English. The second category was Colloquial English, which designated forms such as chillin’, which are written using non-standard English forms shared across varieties of English. Sharedness is what allowed us to make a distinction between Colloquial English and Creole/ Pidgin English forms, which are often variety specific e.g. soon come in Jamaica. We are aware of the theoretical difficulties such a distinction poses, but it goes beyond the scope of the current paper to address this more fully. Furthermore, it was not possible to merge Creole/ Pidgin with the next category, indigenous language variety, since in Ghana, there is a Pidgin as well as several local languages, and such a merger could obscure the realities of language use in posts generated by Ghanaian authors. Thus, the label indigenous language variety was applied to forms that were taken from languages other than English and Creole or Pidgin that occurred in the posts e.g. sota tale in Fiji. The final code was foreign language, which was applied to forms written in a language other than English or one of the languages spoken as a first language in the community in which the post was generated. In the current paper, we present a quantitative analysis, in which we compare the overall frequencies of the different codes in order to gain insights into the distribution of language varieties in the texts. We also carry out a qualitative analysis of the data, in which we focus on possible explanations for the use of different languages used in the posts.

Results

Table 1 shows the frequency of each of the varieties in the sample of posts taken from the different Instagram accounts. The difference in the final word count for each country arose because some accounts used a great deal of text. Though this is, in and of itself, telling with regard to how different users employ the app, this is not the focus of this paper.

Table 1: Frequency of linguistic codes in Instagram posts

Several trends are apparent in the data. Firstly, Instagram posts are largely in English, which accounts for at least 95% of all words used in the Instagram posts. This is unsurprising given the predominance of English in international tourism advertising and on the internet (cf. Seargeant & Tagg, Reference Seargeant and Tagg2011: 502). On the other hand, languages other than English are used only marginally. Creole and pidgin words and expressions are only found in the posts from Jamaica, where they account for some 5.1% of all words used, the highest non-English word count in any variety. Ghanaian posts do not contain any instances of Ghanaian Pidgin English. Instead, posts from both Ghana and Fiji include several instances of indigenous language expressions, which for both countries are the most frequent forms of non-English language use. In the Maldives, indigenous language use is rare. On the other hand, 3.5% of all language used in the posts from the Maldives contain foreign languages, which are completely absent from the posts from Jamaica and Fiji. The low frequency of languages other than English suggests that there is little to be gained from further quantitative exploration of the data. In the remainder of the paper, we discuss the data from a qualitative perspective.

Fiji

The main content of the Fijian posts consists of pictures or videos of Fiji's flora and fauna, accompanied by short texts and hashtags, in which Standard English is used (Figure 1). There are also some colloquialisms, such as it's in ‘It's not goodbye, just see you later’ (Figure 1). The posts introduce Fiji's natural environment to an international audience by using Standard English. In addition to the usage of English, there is evidence of code mixing with Fijian words and phrases. In 17 out of 20 Instagram posts, Fijian loan words are used, most frequently Sota tale (Figures 1 & 2), bulanaire (Figure 2), vinaka, and bula.

Figure 1. Fiji Airways (fly_fijiairways, 2020)

Figure 2. Outrigger Resorts (outriggerfiji, 2020)

One feature peculiar to the Fijian texts is the use of blends. One of them is the blend boatel, which was formed with the help of the nouns boat and hotel, meaning ‘a boat which can be used as a hotel for tourists’. There are also blends formed by combining morphemes from different languages. For example, the word bulanaire ‘people rich in happiness’, is a blend of the Fijian word for ‘hello’, bula, and the English quasi suffix-naire. It seems to have been formed analogously to billionaire ‘a person possessing great material wealth’.

Ghana

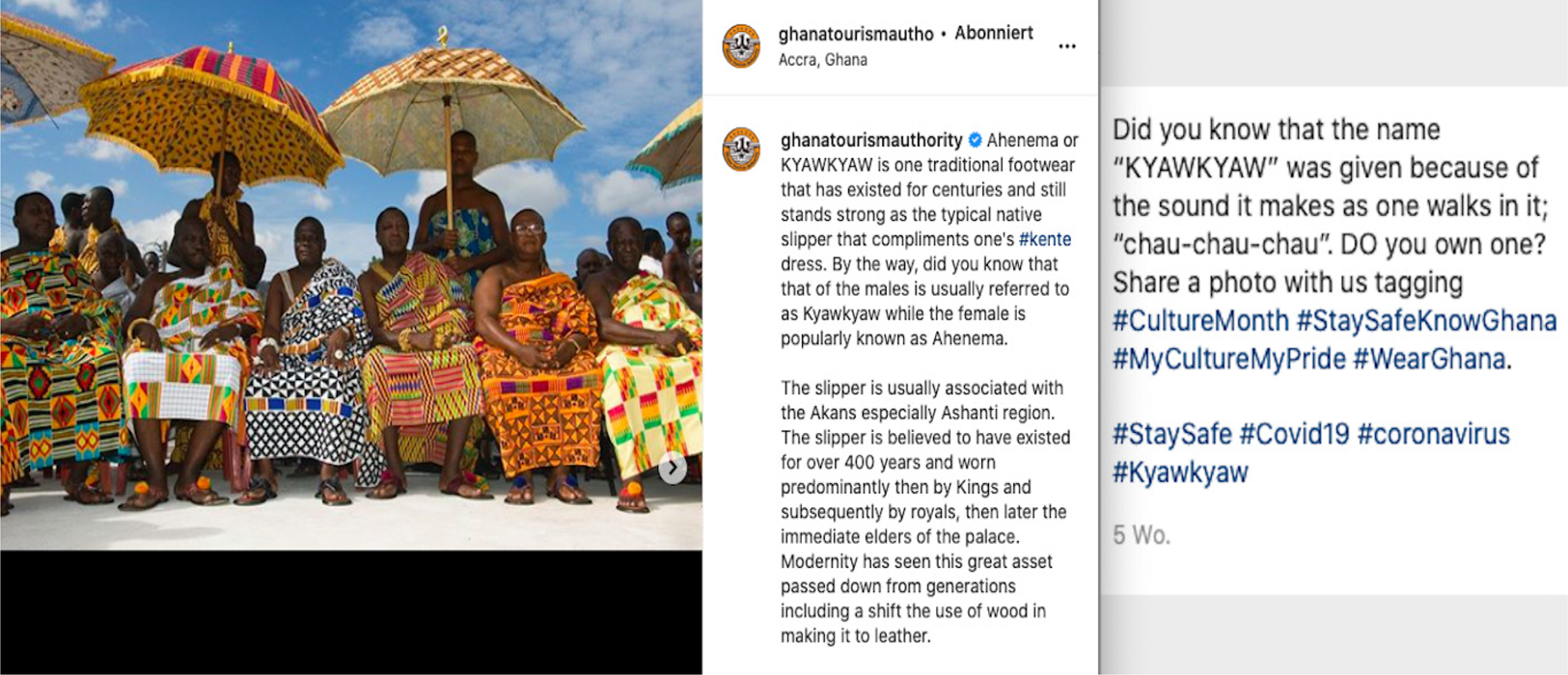

As in Fiji, the main language used in the tourism-related Instagram posts from Ghana is Standard English, accounting for 98% all words. This makes the posts more accessible to English-speaking foreigners and potential tourists. Furthermore, Instagram pages like ‘Ghana Tourism Authority’ mainly advertise the traditional Ghanaian lifestyle in their posts with topics like traditional clothing or food. When doing this they often use Akan words such as kyawkyaw ‘traditional footwear’ (Figure 3), or waayke ‘a typical Ghanaian dish’ (Figure 3). The words are presented with explanations, so that viewers learn something about Ghana from the posts.

Figure 3. Kyawkyaw (ghanatourismauthority, 2020)

Maldives

Figure 4 from the Visit Maldives Instagram account shows almost no traces of a language variety other than Standard English. One potential exception is the sentence, ‘May this Easter makes our bond stronger & renew our hope’, where the main clause contains an example of non-agreement, or perhaps hypercorrection, since, due to the auxiliary verb may, the main verb make should take the infinitive form like the second verb renew rather than the third-person singular form makes. Meierkord (Reference Meierkord2018: 7) identified this feature as part of the English variety spoken in the Maldives. However, it is equally as likely that this is a typographical error, since there is no evidence of this feature being drawn upon to index Maldives English in any of the remaining posts.

Figure 4. Happy Easter (visitmaldives, 2020)

Given that the Maldives’ national language shows an increasing prevalence of mixing with English, especially among the younger generation (Mohamed, Reference Mohamed2013), the absence of Dhivehi in the posts from the Maldives is striking. This may be because our study focuses on tourism advertisements, rather than the personal Instagram accounts of Maldivian users. However, the Maldives’ Instagram posts do draw on foreign languages. In Figure 5, Arabic script is used. This post targets potential Muslim visitors, wishing them a happy Ramadan. Given that the Maldives is an Islamic nation, it is also likely that this post is aimed at locals. However, foreign languages and scripts occur in several other posts from the Visit Maldives account, which also includes uses of Malay, Italian, and Mandarin (using Chinese characters).

Figure 5. Wishing you a blessed Ramadan (visitmaldives, 2020)

Jamaica

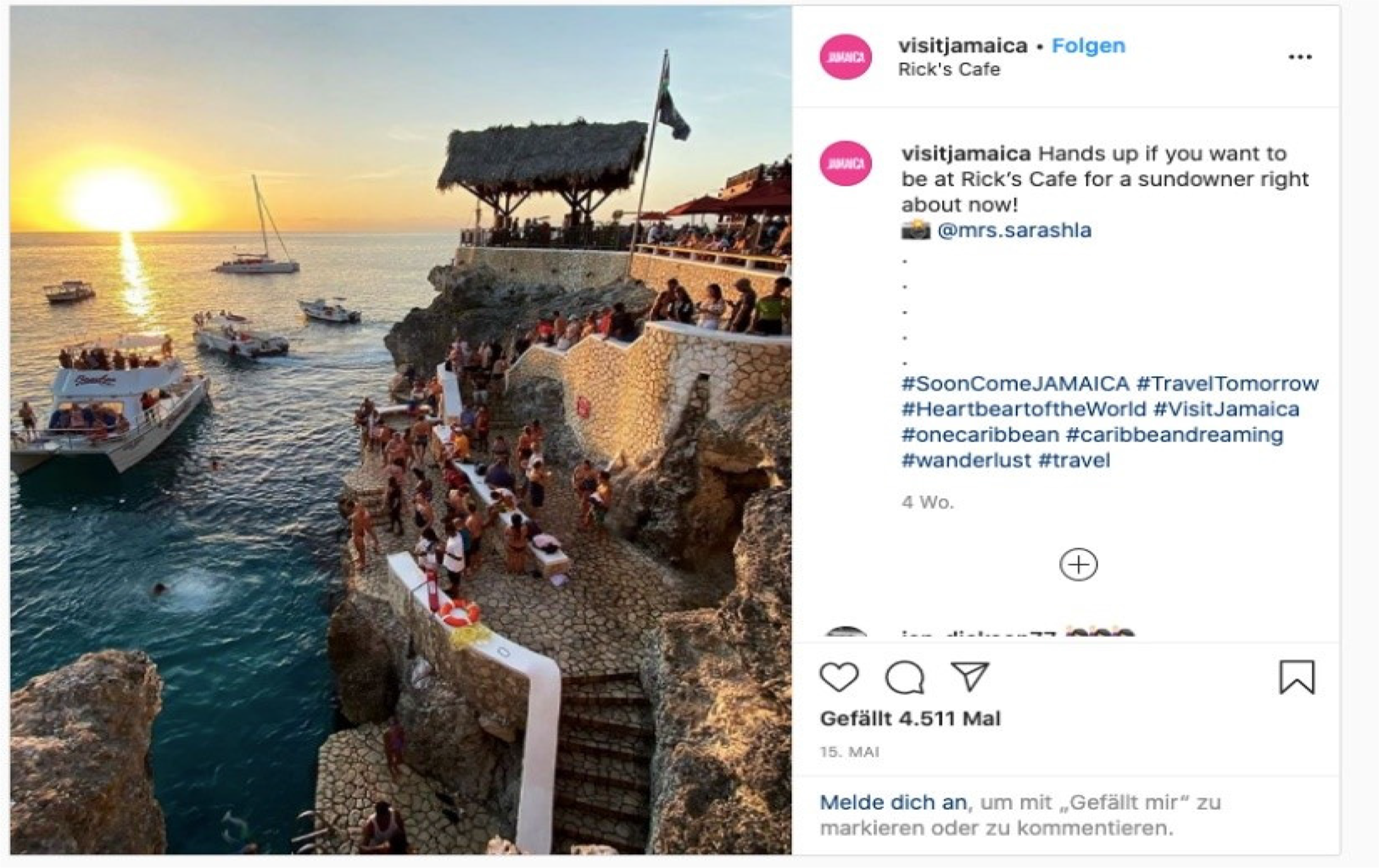

The Instagram posts from Jamaican tourism-related accounts show a general preference for Standard English with JC words or phrases interspersed. For example, in Figure 6, the JC word jerk is incorporated into the otherwise Standard English text. The phrase soon come recurs not only as a caption in many posts (Figures 6, 7) but also as a hashtag. Soon come is a Jamaican expression meaning ‘I'll be right there’ (Rosenfeld et al., Reference Rosenfeld, Farquharson, Jones, Wilson–Shim, Malcojm and Chang2020: 15), but refers to a more distant time period than soon soon, which means very soon (ibid.: 88).

Figure 6. Visit Jamaica (visitjamaica, 2020)

Figure 7. Rick's Cafe (visitjamaica, 2020)

#Hashtags

Hashtags were present in many of the posts, accounting in total for 16% of the total word count. In general, the use of hashtags in the data serves as a form of ‘semiotic alignment’ (Zappavigna, Reference Zappavigna, Seargant and Tagg2014: 149). When used in combination with local languages, especially with food and place names, hashtags lend an element of iconicity to the destinations’ language and culture.

The data were collected between March and June 2020, a period which marked the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, in which several countries were under lockdown and borders closed. This time period is marked in the hashtags. For example, in the Fijian data, posts also included the hashtag #staysafe or #stayhome combined with #seeyousoon, referring to the pandemic and the impossibility of travel during this period. Similarly, the Maldives and Jamaican posts also use the hashtags #staysafe or #stayhome, this time combined with #visitlater and, for Jamaica, #sooncome. These hashtags acknowledge the global circumstances under which the posts were produced and, more importantly, invite readers to start planning a trip to one of the destinations. In the Ghanaian data, the use of the hashtag #staysafeknowghana connects the posts’ authors and viewers to the pandemic, suggesting that even though people currently cannot travel to Ghana, there are other ways of exploring the country.

Beyond the crisis-motivated hashtags, there are a number of other hashtags which occur in the data. Words with direct links to the whole semantic field of travelling such as #bucketlist, #vacation, #travel, or #wanderlust are used very frequently as hashtags, particularly in the Jamaican and Fijian data. In the scheme of Instagram usage, the hashtags serve the practical purpose of making it possible for users to locate the posts related to the topic of #bucketlist, and thus increase the posts’ visibility.

Discussion

At the theoretical level, we see how the extra-territorial forces of colonialism and globalisation, here viewed through the lens of Instagram tourism posts, together influence language use in the posts. English is the primary language of all the posts, possibly because the intended audience of the posts are international tourists, who, given the status of English in tourism, are likely to be able to understand English texts. Our findings thus align with previous theorising by Buschfeld and Kautzsch (Reference Buschfeld and Kautzsch2017) and observations made by Schneider (Reference Schneider2016). Furthermore, the use of English over other official and national languages further highlights the predominance of English on the internet (Seargeant & Tagg, Reference Seargeant and Tagg2011).

Standard English posts provide a matrix into which other varieties may be inserted. Indigenous languages and pidgins and creoles often fill in the blanks that English leaves. This may be partly because some words, such as the Ghanaian kyawkyaw, have no direct English equivalents or because, in keeping with Martin's (Reference Martin2002) observation, English is not used for specific cultural terms. However, other uses of non-English words and expressions comprise formulaic bits of language such as soon come and sota tale. These uses can be understood as indexes of place (Johnstone, Reference Johnstone2011), possibly adding to the posts’ perceived authenticity; viewers of the post are not expected to understand what these bits of language mean without translation or explanation (Figures 1, 3). Furthermore, the use of languages other than English can be viewed as examples of language commodification, where ‘exotic’ accents and languages are parcelled off as part of the tourist experience (Jaworski & Thurlow, Reference Jaworski, Thurlow and Coupland2010).

Conclusion

This paper documents language use in the context of travel advertising for four countries where English is either an/the official language, or, as in the case of the Maldives, indispensable for the local (heavily tourism-based) economy. Despite the fact that Instagram is a photo-sharing app, we concentrate solely on language use. Future studies may consider including a semiotic analysis. We found that Standard English is used predominantly in posts from all four regions, since the target group is an international audience. However, English is complemented by the use of bits and pieces of local languages to evoke the impression of authenticity and highlight local customs and traditions.

GUYANNE WILSON is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Ruhr-University Bochum. Her research interests include World Englishes, language use in diaspora communities, and research methods in English linguistics. During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, participants in Guyanne Wilson's course on World Englishes grew interested in World Englishes on the internet. This paper is a result of their sustained interest and effort. All co-authors were MA students of English at the Ruhr-University Bochum. Email: [email protected]

GUYANNE WILSON is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Ruhr-University Bochum. Her research interests include World Englishes, language use in diaspora communities, and research methods in English linguistics. During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, participants in Guyanne Wilson's course on World Englishes grew interested in World Englishes on the internet. This paper is a result of their sustained interest and effort. All co-authors were MA students of English at the Ruhr-University Bochum. Email: [email protected]  The student authors of this paper were involved in all aspects of producing this article: data collection and analysis, writing, and editing.

The student authors of this paper were involved in all aspects of producing this article: data collection and analysis, writing, and editing.