Port cities were at the heart of the connections of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century imperialism. They are described as emblems of cosmopolitanism at the interstices of flows of capital, people, and ideas.Footnote 1 For scholars of the fin de siècle Indian Ocean, port cities are successors to the hinterland's precolonial kingly capitals and antecedents to the global metropolises of the contemporary world. They are often seen as placeless coordinates in a globally integrated system. Yet to study them as inert sites of transit is to simplify their role in social mixing and commercial innovation. Ideas—such as emancipation, empire, and nation—were mutated in ports. One scholar describes ports as spaces of “shock,” indicating how they were key venues to experience and respond to spikes in migration or shipping and the arrival of news and ideas generated by world revolutions and wars.Footnote 2 Another has called them “hinges” in between empires, continents, trading blocs, and nation states.Footnote 3 Ports may be compared with other spaces of oceanic history—the ship, the island, the strait, or the bay—that are now attracting sustained attention in their own right.Footnote 4 The nature of connection at ports is worth highlighting. Fears of crowding and disease emerged in ports and provided justification for programs of urban planning and segregation.

By focusing on the space of one port, Colombo in the island of Sri Lanka, and how its dense network was crafted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this paper reconsiders the port as a site not only of connection but also disconnection and evacuation. Instead of giving the now fashionable term “connection” simple or full analytical purchase, the paper determinedly historicizes it. It argues, firstly, that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries connection was an idea within an intellectual debate in Imperial Geography and a wider span of imperialist academic disciplines. Secondly, connection was tied to the physical making of the port of Colombo, which in turn arose from ambitious schemes pushed by engineers and capitalists. Thirdly, connection was at the heart of the visual politics of high empire at the site of the port, as seen in the breakwaters of Colombo. From a thick study of this single node of connection—the port of Colombo—I make a provocation. If at an imperial time, connection, “circulation,” and “World History” were linked as concepts, this necessitates critical attention to the history of our own thinking. Connections can channel, mesmerize, and displace. A self-reflexive critique of the word “connection” highlights the need to join linkage with boundedness in moving further with it.

Across the disciplines, from anthropology to history, there have been countervailing tendencies in relation to what Arjun Appadurai called the “scapes” of globalization.Footnote 5 Appadurai's critics argue that globalization is about not only deterritorialization but also reterritorialization: “Flows of various sorts both build up and tear down territorial units. They contribute to the persistence and even strengthening of borders in many cases.”Footnote 6 In another rendition, encounter has a “grip” and proceeds by “friction.” Globalization should then be seen as sticky, for its frictional character is “enabling, excluding and particularizing.”Footnote 7 People do not move freely: cosmopolitanism is conceptually inadequate for coming to terms with the legal frameworks that characterize migration, including, for example, the movement of refugees and stateless peoples. A related concern in anthropology has been the defense of the field site and the necessity of “bounding as an anthropological principle,” through self-imposed limitations to ethnographic work and as a response to an overdue emphasis on multi-sited networks.Footnote 8 Historical geographers and historians of science played an important role in working through the possibilities afforded by networks and webs in order to study the imperial past, and this led into a concern with mediators, imperial cities, or imperial careering.Footnote 9 Such work borrowed heavily from Bruno Latour, who has recently argued that “in spite of so much ‘globalonney,’ globalization circulates along miniscule rails resulting in some glorified form of provincialism.”Footnote 10 This essay follows in the wake of all these reassessments of global methodologies.

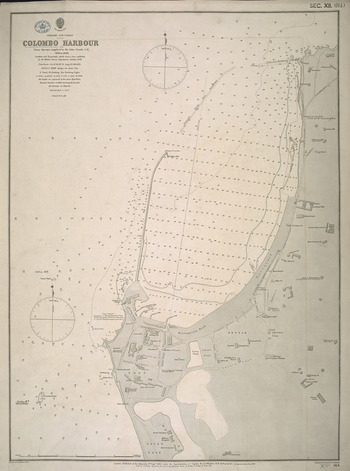

In 1910, the port of Colombo, nicknamed “The Clapham Junction of the East,” was by tonnage ranked the seventh busiest port in the world after New York, London, Antwerp, Hamburg, Hong Kong, and Rotterdam and before Liverpool, Marseilles, and Singapore.Footnote 11 By 1885, a southwest breakwater was constructed, which was followed by dredging, a further bout of infrastructural consolidation in the late 1890s and early 1900s, and the building of a northeast and northwest breakwater. With these changes, Colombo became characteristic of the industrial improvements made by the British Empire and its ability to create sinews of power across the world, here in a place where nature had not endowed a large harbor (figure 1). The growth of trade, tourism, and communications traffic through Colombo was tied to its location on the route to Australia from the Suez Canal, and also to its role as an entrepôt for the Indian subcontinent. A visual repertoire of lines, arms, and passageways characterizes the large number of engravings, photographs, postcards, guide books, and maps that document the port's growth.Footnote 12

Figure 1 “Colombo Harbour, from Surveys supplied by Sir John Coode, C.E., 1878 to 1896.” © British Library, Cartographic Items Maps, SEC.12.(914.).

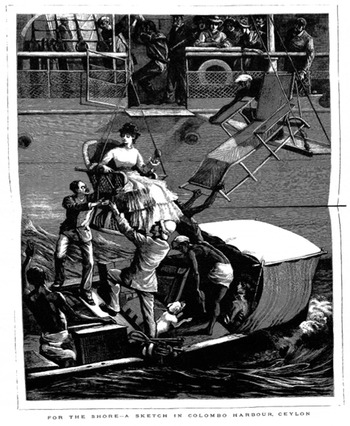

This was a node in the imperial network, a point where the sea and land were bridged, and it was one of the most connected places on the earth. Yet, observe an engraving from the Graphic of 1883 titled, “For the Shore: A Sketch in Colombo Harbour” (figure 2). It shows a woman being taken off a British Indian steamer.Footnote 13 Named only as Miss Barker, she is said to complain of the “Babel-like din,” the “jabbering” and “hurling [of] packing cases, portmanteaus, chairs, gun-cases &c into the [pilot] boat.” She wishes to be ladylike, but how can she come to terms with the fact that she cannot and should not jump into the boat? She is put into a chair and lowered while guarded by Englishmen: “I clasp the rope tightly, and look braver than I feel. I seem to be going down into the waves.” This is not an account of a nodal point or of a seamless passage to the shore. Instead it is evidence of the work that is necessary to make a connection, and of the visual and psychological investment apparent in this period in the event of arriving, here by a single woman. Contrast this with a poster from 1930, after the period covered in this essay, commissioned by the Empire Marketing Board and titled, “Colombo, Ceylon,” which shows very dark laborers hauling packages bound for London onto a ship (figure 3).Footnote 14 Here imperial trade is made a visual marvel, and yet, in this instance, the laborers, who are raced and gendered differently than Barker, are central to the linking of sea and land.

Figure 2 “For the Shore: A Sketch in Colombo Harbour,” Graphic, 24 Feb. 1883.

Figure 3 K. D. Shoesmith, “Colombo, Ceylon” (ca. 1935). Source: Manchester Art Gallery, 1935.729.

This paper, instead of taking the transition from ship to shore or from shore to ship for granted, teases apart the moment depicted in these two images. As one moves from the 1880s to the 1910s, connection comes to seem more stable and racially hygienic, in the face of the fears expressed by Barker and others. Visual instruction and consumption were central to the production of connectivity in the imagining, of lines of passage, linking land and sea, the highland plantations and the lowland entrepôt, and railways, carriages, and ships in turn. This is in keeping with Tim Ingold's suggestion that the straightening of lines was central to modernity.Footnote 15 Imperial thought, education, and capital also played their role by bolstering the prestige of the British Empire and its coffers, and by recourse to grand visions and proposals of dense networks of connection. This was the imagination of “Greater Britain” as a global polity.Footnote 16 If connection was crafted in this way, taking it apart leads us to what connection made invisible and who was subjected to oppression in the process.

Useful in contextualizing the idea of Colombo within a history of intellectual disciplines are the writings of Halford Mackinder (1861–1947), the geographer and imperial strategist, along with the work of two of his associates in Colombo, F.H.H. Guillemard (1852–1933), another geographer, and Alfred Hugh Fisher (1867–1945), a photographer who worked for Mackinder and wrote copiously to him while travelling. The paper will begin with Mackinder's writings and their resonance with the terminology of present scholarly concerns with connection. It then shifts focus to the port of Colombo as a visual icon in the photographic collections of Guillemard and Fisher. From there, the paper's scope broadens to the imperial context for the making of the port by considering the infrastructural, commercial, and visual production of its breakwaters. The sting in the tail comes at the end with a study of the underside of the port of Colombo's connections.

IMPERIAL THINKING

Halford Mackinder is famous for many things: he is known as the father of “geopolitics,” despite his dislike for that term. He was also the author of the 1904 paper “The Geographical Pivot of History,” a study in futurology that is still debated. It set out that the quest for world dominance would be fought in the Eurasian heartland. The strategic basis of power, he argued, was shifting from the seas to the land. He was also an imperialist advocate of geography and of the value of the discipline as an entry-point into other fields such as history. Yet despite their general correctness and applicability, these stereotypes of Mackinder do not serve well here. Though he defined his “Heartland” as the area which could not be accessed by sea, he did not obliterate the significance of the seas, and though his commitment to imperialism was undoubted, it is instructive to observe how it was wrapped around an attachment to the globe, as the physical planet.Footnote 17

With an Anglican and liberal upbringing behind him and an education at Oxford, initially in the sciences and then in modern history, Mackinder also took up geology, anthropology, and economics and entered the Inner Temple to read law. But law was not to his taste and he was appointed Reader in Geography at Oxford University in 1887, and later the Director of the London School of Economics (1903–1908). The need to assert the primacy of geography over rival fields of inquiry quickly became keenly-felt. In a paper that he read at the 1911 Imperial Education Conference titled “The Teaching of Geography from an Imperial Point of View,” he argued that geography should be the “chief outlook subject” in schools, taught by methods of “visualization.” This was not a call for the dry “knowledge of place names,” but rather for “a special mode and habit of thought,” or even “a special form of visualisation which I cannot otherwise describe than as ‘thinking geographically.’”Footnote 18

Mackinder argued for the geographer's preference for a map with no names on it. Such a map can let the mind's eye roam more easily: “Finally … the pupil [of geography] is asked to visualise with a single grasp our whole world of varied scene and incessant change.” A significant feature of this method was to focus in on a point and then to use that point as a vantage from which to zoom out to the entirety of the planet and world. Mackinder specifically noted the need for what he called “World History,” but argued that it should be taught as a geographical subject. The students first acquainted themselves with the homeland, “there learning to read the geographical alphabet,” and then proceeded in order around it, so that what he called “the incidental history,” namely the non-European, could be put into a chronological sequence around the metropole.Footnote 19

Reading Mackinder is a bit unnerving for those who try to theorize the historical relationship between land and sea and discover the right way to address the balance between empires and their global setting. This is why even a scholar of standing such as Paul Kennedy can end up seeming like an admirer who forgets Mackinder's unsavory political legacy.Footnote 20 One way in which Mackinder's prose rings of presentism is his use of the language of circuitry in theorizing linkages, which is once again in fashion. For instance, he wrote of the closing of the age of discovery by the end of the nineteenth century, “We now have a closed circuit—a machine complete and balanced in all its parts. Touch one and you influence all.”Footnote 21 Or again, in his famous paper of 1904: “Every explosion of social forces, instead of being dissipated in a surrounding circuit of unknown space and barbaric chaos, will be sharply re-echoed from the far side of the globe, and weak elements in the political and economic organism of the world will be shattered in consequence.”Footnote 22

The globular, the nodular, the linear, the circuitous, and the bodily were metaphors of Mackinder's geographical thought and these resonated more broadly in the intellectual ferment of his age.Footnote 23 Despite advocating global connections and the revolutions brought about by the railroad, the steamship, and later the airplane, as they spread dense lines of linkage and democracy, Mackinder tied these interests to the British Empire. The contradiction is well expressed in one formulation in Britain and the British Seas (1902): “Britain is possessed of two geographical qualities, complementary rather than antagonistic; insularity and universality.”Footnote 24 The insularity of Britain here arose from its island status and also from its history as a maritime power, for the seas were a terrain of defense for Mackinder. Yet, for him, universality could also be defined as British because of the British character and racial stock. In equating the global and the imperial, and the islanded and the universal, Mackinder sought to naturalize the British Empire. Its rise could be explained in accord with the geology, tidal pattern, the rivers, and the climate of the British Isles.Footnote 25 As a Social Darwinist, Mackinder held that human circulations were part and parcel of biological circulations, and chemical and physical reactions, and in fact were determined by the latter.Footnote 26 These slippages in disciplinary method and the combination of spatial inclusivity with British expansionism made way for his use of the word “global,” set apart from the “world” and linked to the British Empire.Footnote 27

“The Geographical Pivot of History” was certainly written by reflecting on current events, and it bears the signs of the South African or “Boer” Wars and also of Russia's deployment of troops in Manchuria in 1904. Though both of these theaters highlighted the British need for land-based power, Mackinder did not delete the value of the seas. Japan was triumphant against Russia, after all. By the First World War the declining usefulness of maritime power was clear. In fact, Mackinder wrote that the war was a contest between islanders and continentals.Footnote 28 However, in chapters concerned with geology, which later commentators have been less interested in, Mackinder wrote: “The rough molding of the land surface resembles that of the seabed, and is continuous with it. As the seabed presents shallows and deeps, so the land has its lowlands and uplands; and as the deeps are broad basins with gradual slopes sinking to wide undulating bottoms so the uplands rise from the lowlands in bas-relief, like the sovereign's head on a coin, with slightly-rounded surfaces….”Footnote 29 There is a parallelism between seeing land and seeing sea in Mackinder's writing and this imaginative or even visual tension points to how he sought to link the sea and land as spaces of politics and natural circulation. As the historical geographer David N. Livingstone writes, Mackinder used evolution as a means of keeping “nature and culture umbilically connected” around geography.Footnote 30

Another reason to qualify any sense that Mackinder's work allowed a turn away from the seas is that several of his acolytes and colleagues continued to undertake and write of sea journeys as a way of envisioning the globe, the frontier, and the empire. The seas were at the heart of the work of the Visual Instruction Committee, established by the Colonial Office in 1902 to visually instruct British children about the empire and children in the colonies about Britain. Mackinder's own Eight Lectures on India began by taking the reader from Dover to Marseilles, through the two Straits of Bonifacio and Messina to Port Said and the Suez Canal, and then to Aden and Colombo. Leaving Ceylon behind and entering India from Tuticorin, the reader is addressed by Mackinder lying on their bunk on a ship and called to imagine their location on the globe and the route of their journey.Footnote 31 A. J. Sargent's The Sea Road to the East (1912), another text brought out by the Visual Instruction Committee, also took its reader on a steamship journey with lectures on Gibraltar and Malta, Malta to Aden, and the Indian Ocean, followed by Ceylon. In these accounts, the traveler exults in the industrial improvements wrought by Britain—for instance noting that the new port of Colombo “owes everything to engineering”—but at the same time is reminded of a “network of traffic and intercourse which was in existence centuries ago, long before the first European keel broke into the eastern seas.”Footnote 32

Here it is appropriate to introduce two people—one a direct agent of Mackinder and the other one of Mackinder's colleagues—whose photographic collections of Colombo are studied in the next section of this paper. Both of them undertook sea journeys. At Mackinder's behest, the Visual Instruction Committee appointed Alfred Hugh Fisher (1867–1945) to take photographs and make drawings of his travels around the world. Linked with the Illustrated London News, he was a painter trained in photography and equipped with two cameras. According to the instructions given to him, Fisher's images were to relay both the “native characteristics of the country” and the “super-added characteristics due to British rule.”Footnote 33

The sea journey and the arrival at port are also combined in the writings of another geographer operating in this period in Cambridge. This is F.H.H. Guillemard, who traveled widely and was in South Africa for the first “Boer” war of 1881. Somewhat earlier than Fisher, Guillemard took up the early nineteenth-century British tradition of the natural historical voyage, in the form of a zoological sea voyage on the yacht Marchesa, from 1882 to 1884, with the aim of “wandering into unknown paths and infrequent waters.” He returned with over three thousand bird specimens.Footnote 34 The Cambridge geographer published Ferdinand Magellan and the First Circumnavigation of the Globe (1890) in “The World's Great Explorers” series. It was edited by Mackinder, together with J. Scott Keltie and E. G. Ravenstein, and with these scholars Guillemard was a stalwart of the Royal Geographical Society. His journey on the Marchesa also involved the imagination and reconstruction of strategic waterways and dense passages of maritime activity, very much in keeping with Mackinder's brief for the new geography. He wrote to his elder sister Caroline from the Red Sea in 1882 about the Suez Canal and its linear character: “You must know the place by heart. I should think without ever having seen it. The endless wastes of perfectly level sands; the absolutely straight line made by the canal through it, flanked by the telegraph poles becoming fine by degrees and beautifully less till they disappear into nothingness….”Footnote 35

Having situated Mackinder in relation to land and sea journeys, it is time to move to the port of Colombo.

“CLAPHAM JUNCTION OF THE EAST”

Colombo was a port of great interest to imperial geographers because it became a regular stopping point after the opening of the Suez Canal. Western geographers had been interested in the island's ports for centuries, but in the late nineteenth century the placing of Colombo in a grid of linkage took on a mechanical intensity.Footnote 36 Both Fisher and Guillemard participated in this project.Footnote 37 Photographs arising from the port were concerned with passage and movement; they made connection legible while distinguishing the technological feats undertaken by the British Empire from the naturalized mobility of indigenous peoples. Reproductions came quickly and evinced the latest designs of photography.

Fisher wrote to Mackinder of his arrival, combining the imperial with the exotic: “I went ashore in a small boat and the first thing I noticed outside the gates of the landing stage was a large white marble statue of Queen Victoria and a stand of rickshaws in front of us.”Footnote 38 In leaving Colombo, he wrote, “I looked back over the great enclosed field of water. If only Trinco [Trincomalee] had been on this side. Yet without a natural advantage a good harbour has at last been made and Colombo is destined without doubt to become more and more important.”Footnote 39

The departing sea-borne textual eye inverted the directionality of the land-based photographic eye looking to sea. Images looking out across the harbor of Colombo from within land were common in this period. Guillemard carefully put together a series of albums after his voyage, and that titled “Ceylon VI” includes ninety-one photographs that he collected. It includes “Colombo Harbour,” embossed with “Photographer W.L.H. Skeen & Co Colombo Ceylon” (figure 4). It is a layered image: the large carpet of coconut trees in the foreground balances the empty sky at the top of the image, leaving the viewer with thin and dense lines in the middle of the photograph, denoting the town, the smaller sailing vessels, and the steamships lying in parallel.Footnote 40 Once again, it is all about imperial lines, picking up Imperial Geography: the image is structured in a linear grid which guides the reader along tracks of connection. At the same time, the eye moves out to sea from the land. It is the exact counterpart of the mode of vision displayed by the departing Fisher, who in fact documents the segments that make up this image from the opposite direction of vision. Fisher continued to Mackinder: “Beyond the foam track of the steamer and the thin line of the harbour embankment I watched the city dwindle to a long low strip of dark sprinkled with lamps. To the right the clock tower showed its intermittent flare and far away to the left stretched the band of neutral grey, which I knew to be palm forest. The sky was flushed for a little with the rose colour of the afterglow and then the night fell quickly.”Footnote 41

Figure 4 “Colombo Harbour,” from F.H.H. Guillemard. Source: Add 7957/6/82, Ceylon VI, Cambridge University Library.

From the mid-nineteenth century the importance of Colombo was tied to the spread of colonial plantations and the ready access from the western side of the island to the highlands where crops were grown. As historian Michael Roberts notes, Colombo changed over the course of the century from being a colonial fort and citadel to a site of commerce and symbolic display, even as its fortifications were demolished. Its rise to prominence was not a natural given, but arose out of the needs of colonialism.Footnote 42 While in mid-century there was a division of roles between Colombo and its southern rival Galle, this gave way by the 1880s to the undoubted supremacy of Colombo over all of these services.Footnote 43 The main callers in the islands' ports were of course British or British colonial vessels: amounting to 2,420 ships in 1909, compared with 813 non-British ships that same year, mainly of German, Maldivian, French, or Japanese origins.Footnote 44

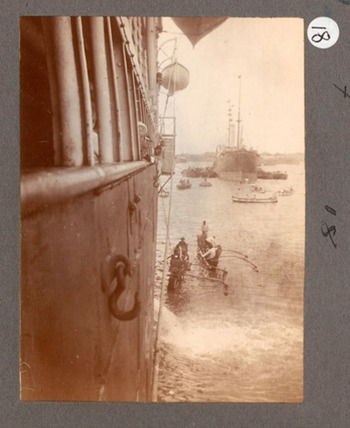

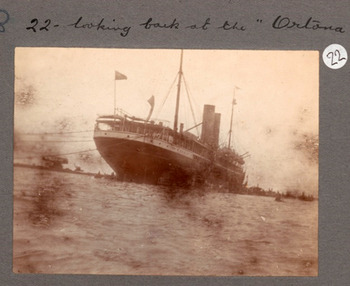

Fisher's photographs bear the traces of his own journey and the album arranged for the Visual Instruction Committee begins in Port Said with the arrival of coal barges, and out at sea looking at Cape Guardafui in Somaliland.Footnote 45 Details of Fisher's arrival at Colombo are there in full in what is effectively a photo-diary: the arrival of the pilot boat to convey passengers to shore, a “Dug-out canoe,” “Boys diving for coins,” and the gradual approach to the landing stage are all pictured and arranged for view.Footnote 46 James Ryan writes that the impressionism in Fisher's photography somewhat intrudes into Mackinder's structuralist agenda.Footnote 47 This is true, but the disruption caused by impressionism must not be overdone. Despite the difference of style, Fisher's photographs, like Guillemard's, are still concerned with lines of passage, connectivity, and the link between sea and land. The narration of his arrival thus depicts local boats pulling alongside the vessel in which he arrived, the Ortona, which draws the viewer along a line radiating into land, and picking up another steamer in the distance. This forward glance is followed by a backward one as Fisher gets into a “small boat” and looks back at the much larger Ortona (figures 5 and 6).Footnote 48

Figure 5 Disembarking from the Ortona, no. 18, Alfred Hugh Fisher, Fisher 1: “Outward Journey, Ceylon, October–December 1907.” Source: Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

Figure 6 “Looking back at the ‘Ortona,’” no. 22, Alfred Hugh Fisher, Fisher 1: “Outward Journey, Ceylon, October–December 1907.” Source: Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

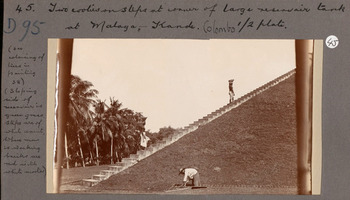

The interest in passage and movement fits into a recurrent motif in both of these travelers' collections: namely the staircase, the bridge, and the railway line as further marks on the island of Lanka, which link it up to create the modern colony in global context.Footnote 49 This was a visual technique of making connection legible. Perhaps most striking in this respect is Fisher's “Two coolies on steps at corner of large reservoir tank at Malaga Kande. Colombo. ½ plate”Footnote 50 (figure 7). This was used as the basis for a painting, which is no longer in the Fisher collection since no watercolors of Ceylon are extant. It also follows a photograph, now missing from the album, which was of the whole of Colombo, taken from the top of this reservoir. The missing image lives on in a plan Fisher drew of the image, which pays especial attention to the horizon and is titled, “The whole city almost entirely hidden by trees.”Footnote 51 These ephemeral and textual traces show that Fisher deliberated and constructed his images; any impressionism must not indicate spontaneity. He noted that he visited this particular reservoir twice because he wished to better an earlier photograph. The image of the steps at the reservoir in the album is annotated: “Sloping side of reservoir is green grass. Steps are white cement. Where man is working bricks are red with white mortar.” This may be read alongside a letter to Mackinder, which reveals that Fisher hoped to highlight that the mason at the front was “Mohammedan.”Footnote 52 The photograph can be compared with a much more historicized pair of images in Guillemard's album, titled “Mihintale: upper flight of steps leading up the Sacred Mountain,” and “Minhintale: lower flight ditto.” Here, unlike in images of colonial improvement, nature intervenes into the path, which is decaying and deserted (figure 8).Footnote 53

Figure 7 “Two coolies on steps at corner of large reservoir tank at Malaga Kande. Colombo. ½ plate,” no. 45, Fisher 1. Source: Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

Figure 8 “Mihintale: upper flight of steps leading up the Sacred Mountain,” and “Mihintale: lower flight ditto.” Source: Add 7957/6/51, Ceylon VI, Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

Such historicized attention to pathways accentuates the improvements of the railroad. Guillemard included a stock image of this period of “Sensation Rock on the Kandy Railway,” and also “Allegala Peak from the Kandy Railway.”Footnote 54 The focus on the port of Colombo and steam travel thus fit into Mackinder's other technologies of land-based mobility; all of these modes of connection were placed together and contrasted with local paths and travel. The images of the railroad almost invariably include a train in motion, which contrasts vividly with the forlorn character of the Mihintale steps. In Fisher's album, “Scenery on the way to Kandy from Polgulla station” is structurally similar to the photograph taken from the side of the ship he arrived on (figure 9).

Figure 9 “Scenery on the way to Kandy from Polgulla station. The train rounding a curve. Taken from the train,” no. 77, Fisher 1. Source: Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

Catamarans or local canoes figure often in the visual repertoires of these two travelers and others. They also accentuate the power of the steamship and are naturalized. This allows these canoes to become part and parcel of the conditions of the rise of the British Empire rather than its motor. In Guillemard's collection, the image of Colombo harbor is quickly followed by “View from Mt. Lavinia Hotel,” the old out-of-town residence of the British governor. Given what Mt. Lavinia looks like today, this shot shows an astonishingly still and unpeopled vista, except for one figure that cannot be deciphered since he or she is out of focus. The catamarans are all lined, on one shore, merging into the sand, and balance out the coconut trees from which they are made on the further horizon of the bay (figure 10).Footnote 55 The relationship between coconut trees and boats is also evident in another image: “Outrigged sampans, Ceylon,” where the canoes are nestled amongst the trees.Footnote 56 Fisher took photographs of catamarans, too. On his arrival he wrote to Mackinder that they seemed like “roughly hewn logs which could hardly be dignified by the name of dugout canoes.”Footnote 57 Even before he landed, men had climbed aboard wishing to sell him models of catamaran boats, amongst other items designed for passing tourists.Footnote 58 For “No. 171,” a photograph in the second album connected to his journey, he has “Fishing boats in Galle,” specifically annotated “(Band of green coconut palms in background—sand in front).”Footnote 59 He also wrote to Mackinder of a photograph he had taken of “native boats” and his description of it is redolent with naturalism. This last image was taken outside the harbor: “I was on the outskirts of Colombo and getting down from the gharry a few hundred yards walk brought me to Mutwall Point near which is a fisherman's quarter. The boats were all drawn upon the beach and their tall masts with the background blue sea framed in forests of cocoa palms made good picture under the setting sun. The red earth glowed like burnt Sienna and then a herd of goats mingled with a crowd of coolies returning from work in a scrambling confusion.”Footnote 60

Figure 10 “View from Mt. Lavinia Hotel.” Source: Guillemard, Add 7957/6/84, Ceylon VI, Cambridge University Library.

VISUAL MARKETING

The spread of the line—as a visual device—linking sea and land, and Europe and Asia, may be taken as Mackinder's closing of the circuit. Such line-making surely arose out of the governing forces of empire, but it was dependent also on another body of agents: the men of capital. They pushed for Colombo to take on more transshipment.Footnote 61 Given this commercial context, this section will place Fisher's and Guillemard's photographs within the world of finance and the popular market for postcards. The breakwaters in the port of Colombo, scrutinized below, are an excellent topic for showing the links between commerce, images, and imperial ideas. They were the subject of some of the most circulated postcards of Colombo.

The building of Colombo's breakwaters can be understood from the perspective of other schemes proposed for the integration of the port within circuits of transport, trade, and communication. One such proposal saw the Chamber of Commerce and Governor Arthur Havelock in a standoff in 1893.Footnote 62 Another bold plan came from a paper written by John Ferguson, who had recently taken over the running of the Ceylon Observer. The Ferguson paper, read at the London Chamber of Commerce in 1897, advocated the building of a railway line between Sri Lanka and India. It began with a survey of the importance of ports to the colonial history of Sri Lanka and to the military security of empire, and described Colombo “as the most central and convenient” of ports “in the Indian Ocean” after the opening of the Suez Canal. In proposing greater connectivity between the island and the mainland, Ferguson wrote:

Travancore, a flourishing planting division in Southern India may be considered an offshoot from Ceylon, its first planters having been trained in the island, and the natural market for its tea &c., is Colombo—where there is now regularly established weekly public sales of tea. To all Anglo-Indians in the Madras Presidency—whether public officers, planters, missionaries or others Colombo must become the favourite port, because there, they can get a steamer direct to almost any part of the world, which is not the case at Calcutta or even Bombay, while few steamers now call at Madras.Footnote 63

Though Mackinder, then relatively unknown, was not mentioned, the politician who was discussed in the paper was another liberal imperialist, Charles Dilke, the author of Greater Britain (1869) and Problems of Greater Britain (1890). Ferguson expanded on Dilke's notion of the strategic significance of India for the “succour and supply of our Eastern possessions,” a quote from the second book, and asked about a specific point: “At what point on her vast coastline are the succour and supply to be made available?” The reply came immediately: “The Eastern Portsmouth should stand in the utmost south, an arm outstretched to succour. And the two should be made one by the railway—by the Indo-Ceylon Railway.”Footnote 64

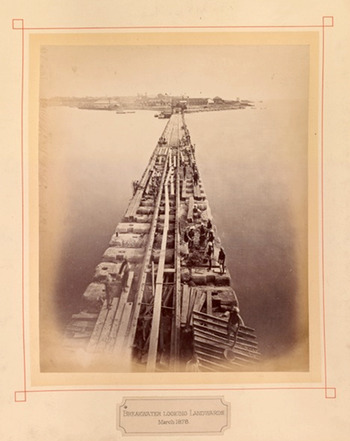

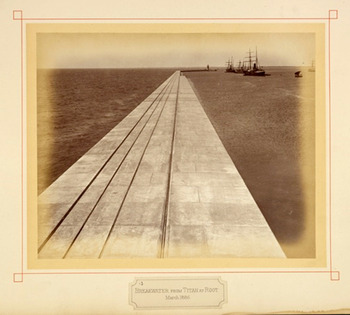

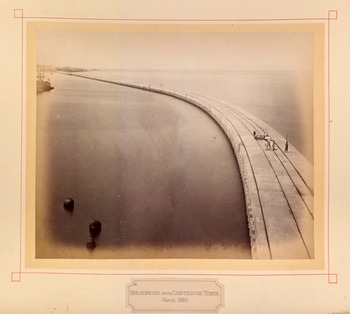

The idea of the outstretched arm is a suggestive segue into considering the building of the first breakwater. It was depicted as an arm in the water in an album bearing the title, “Colombo Harbour completed, 1885.” The copy at Cambridge University Library is inscribed “Sir W. C. Sergeaunt K.C.M.G. with Sir John Coode's compliments.” Coode (1816–1892) was the consulting civil engineer for the plans of the first breakwater, and Sergeaunt was Crown Agent to the Colonies. The album begins with the laying of the first stone by the Prince of Wales and ends with ships at the completed breakwater. The photographs are arranged chronologically by the date of their taking. “Breakwater during S. W. Monsoon, June 1879” shows a scene which became an unexpected staple of Ceylon in this period, with large waves breaking over the breakwater, showing the power of British industry to tame nature. Yet the importance of considering the use of lines in interpreting and literally deconstructing these images is best evidenced in “Breakwater looking Landwards, March 1878,” which together with “Breakwater from Lighthouse Tower, March 1885” and “Breakwater from Titan at Root, March 1885,” shows the emergence of a road into the sea, which is then connected by a railway that comes right up to it, shown in other images (figures 11–13). Here the breakwater overshadows the city of Colombo considerably. But who are the blurry men, standing at attention on the breakwater and hard at work on it? They are convicts, whose labor was paid for with 37½ cents (9d) per day to the Prison Department, compared with the going daily pay of 85 cents (1s 9d) per day for free labor in this period. In the first phase of the development of the harbor the convicts worked for eight hours in the monsoon season and twelve hours outside it to develop the port.Footnote 65

Figure 11 “Breakwater Looking Landwards, March 1878.” Source: GBR/0115/Y303C, Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

Figure 12 “Breakwater from Titan Root, March 1885.” Source: GBR/0115/Y303C, Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

Figure 13 “Breakwater from Lighthouse Tower, March 1885,” “Colombo Harbour, Completed, 1885.” Source: GBR/0115/Y303C, Royal Commonwealth Society Collections, Cambridge University Library.

If the breakwater could in this way serve as a form of cheap discipline for criminals, it also became a spectacle of early twentieth-century imperial tourism and one of the most circulated images of the port of Colombo. Colombo became a popular winter resort in the early twentieth century, challenging Egypt for business: two hundred tourists came in 1883, compared with 6,430 in 1905, and this excludes those who stayed only for a short transit.Footnote 66 In one night's online shopping on eBay, this author bought dozens of used and unused postcards of Ceylon from the early 1900s. This is a sign of the afterlife of early twentieth-century tourism.

Two almost identical postcards of the breakwater, both used in 1910, bear out this alternative gaze. The crashing of the wave on the breakwater in these cards is broadly similar to “Breakwater during S. W. Monsoon”: taming nature involved the visualization of both calm and stormy seas. One was posted from Colombo on 18 August to a Mrs. Kennedy of 36 Fleming Street, Mayport, Cumberland, England.Footnote 67 The sender, who signs off as E. K. Seb, writes of the “awfully hot” weather and says that they are on the way to Calcutta: “This Breakwater is a fine sight. We are laying alongside it.” The other postcard was not posted but is dated 10 January 1910 and simply notes how the breakwater is a must-see: “They say this is one of the sights of Colombo in the rainy and windy season”Footnote 68 (figures 14 and 15). While these postcards document how the image of the breakwater is significant to the message on the back, the image plays much less of a role elsewhere. To Mr. A. Jenner in Lancashire is sent a postcard dated 22 May 1914, just prior to the official start of the First World War, and titled “Nearing Naples”: “Just a line to show you I have thought of you during the voyage I can hardly realise that I am returning to the Homeland and all of you. Minnie.”Footnote 69 The exact same postcard was also sent to Miss Bridgeman of Kensal Rise by Rosa and posted directly from Colombo. This time the postcard functions as a Christmas card.Footnote 70 The image seems irrelevant and the message is not about a passage across the ocean and the prospect of reunion or being separated for a time. Instead, the card records the mundane happenings of life and normalizes the distance over which the correspondence is undertaken: “Glad you liked blouse. Would have left you my blue silk evening dress had I known it would have split to pieces so quickly out here. Have one in Rose Pink & black & white [?] now. Should love to have Xmas dinner with you all. Much love from Rosa.”

Figure 14 Postcard postmarked 19 August 1910, 9:15 a.m., sent to Mrs. Kennedy, 36 Fleming St. Mayport, Cumberland, England, from E. K. Seb, with black and white image titled “Colombo Breakwater.” Source: author's collection, purchased on eBay, 24 Aug. 2013.

Figure 15 Postcard dated 10 January 1910, signed “Be,” with black and white image titled, “Colombo Breakwater (S.W. Monsoon).” Source: author's collection, purchased on eBay, 24 Aug. 2013.

Postcards were bought by tourists making quick stops in Colombo while changing ships or waiting for their vessels to be prepared for the next leg. This means that they bear the marks of transit: though they arise from connection, in fact their use and reception suggest the opposite. Postcard images of Ceylon from this period were posted at sea and some in this sample are headed, “Red Sea, Apprg’ Suez,” or “Indian Ocean,” or “Bombay.”Footnote 71 Take, for example, a rather interesting postcard showing a young woman from Ceylon with a cigarette in hand.Footnote 72 It is annotated as follows: “July 18th. Arrived safely this morning after a nice passage. The S. S. Ortona is due to arrive at 8 a.m.” In an interesting coincidence, the card is postmarked Tuticorin as well as Colombo and was sent in 1907, the same year that Fisher arrived in Ceylon and traveled on to Tuticorin on the Ortona. These cards—when the message, image, and place of posting are put together—bear the marks of a great muddle, which can barely be unpacked. But this is precisely the claim that should be established: right up until their acquisition by this author, the postcards have been decontextualized, and circulated, over and again—circulation has led to disconnection.

At another level, too, the circulation of these images is the product of capital. For instance, “Mount Lavinia Sea Coast, Colombo” is a color postcard printed in Saxony, and bears the following line: “Published by ‘The Travellers Mart’ 14 York Street & Baillie Street, Colombo.” It was only in the late 1920s that “The Travellers Mart,” which was in fact primarily a pharmacy, was taken into the proprietorship of M. D. Uduman, whose name appears on the card as holding the copyright, allowing it to be dated.Footnote 73 This shop was known for operating motoring tours and also held a telegraphic address. It sold “one of the largest and best selections of postcards in the island.”Footnote 74 Another postcard, also sent at Christmas, by Rosa to Mr. A. Bridgeman of Stoke Newington, was copyrighted by “The Colombo Apothecaries Co. Ltd,” indicating that postcards were sold by pharmacies in this period.Footnote 75 This also is an image of local catamarans, which needless to say are placed next to coconut trees: “These boats are made by natives they are so narrow you cannot get your feet in crosswise but have to put them in lengthwise of the boat. They are balanced on one side only by a heavy piece of wood. Run through the water like a train & would throw you in the water in two seconds until you get into the know of them. Love from Rosa.”

The state kept a close eye on the development of the post during this period and monitored the post's contribution to its coffers. By the early twentieth century, the dry statistics accumulated in the government's administration reports provide an indicator of how there was a boom in the postcards in circulation through Ceylon. As shown in table 1, above, the weight of mail dispatched to the United Kingdom alone, through multiple routes, went steadily upwards between 1897 and 1906. The P&O and Orient lines of steamships carried some of this mail, as did French and German steamers.Footnote 76 In 1901 it was reported that the weight in letters and postcards had increased by 124 percent in ten years. Since the state was more concerned with the weight of postage rather than units, it did not usually report on the number of postcards in circulation. However, in 1901 a breakdown was offered in the official reports: 689,106 postcards were sent from Colombo and 1,541,960 from “other stations” in Ceylon in the year under review. Meanwhile, 354,418 postcards were received from overseas.Footnote 77 This exponential growth of the visual market of connectivity points in turn to its sources in empire, capital, industry, and tourism.

Table 1. “Weight of Mails Despatched to the United Kingdom” (letters and postcards only and weights in pounds), Report of the Postmaster-General and Director of Telegraphy, 1906, CO 57/167, TNA.

THE INVISIBLE PORT OF COLOMBO

It is not only because of its association with the evils of high imperialism and bourgeois tourism that the evidence of connectivity deserves to be reconsidered and deconstructed. It is also because the language of connection can be racially blinded, in keeping with the thought of liberal imperialism. Mackinder's Social Darwinism allowed him to embrace an argument about skulls in defining the nature of the British race. He noted that the “long-skulled type” was surprisingly predominant in Britain: “No distinction whatever can be drawn in this respect between the most thoroughly Teutonic and the most completely Celticised districts.” He carried on that even “the Neolithic peoples of ancient Britain were of the long-skulled group.”Footnote 78 In his famous “Geographical Pivot” paper he favorably cited Edward Augustus Freeman, historian and supporter of Gladstone, who held that “the only history which counted is that of the Mediterranean and European races.” In commenting on this view, he added: “In a sense of course this is true, for it is among these races that have originated the ideas which have rendered the inheritors of Greece and Rome dominant throughout the world.”Footnote 79 In his own paper, Mackinder went on to explore the opposite view that the history of the non-European world counted, but only because of the threat that cultures outside Europe posed to Europe. Both forms of argument were imperialist ones that sought to prop up the British Empire by recourse to history.

In following Mackinder's thinking out to the Indian Ocean, a similar interest in physiognomy and racial imagining appears in the work of Fisher. Though none of these encounters were photographed, the artist-photographer wrote to Mackinder of his experience aboard the Ortona before its arrival in Colombo. He provided a long description of one conversation with an elite Sinhalese doctor, and made excuses for this exchange: “There are several Cinghalese on board and knowing something of the feeling against native society I avoided talking much with them but in the last few days I have had several long talks with a Cinghalese doctor—the head physician at the chief hospital of Colombo and a man of wide culture and education. He is very thin and spare in appearance, whereas the others of his race on the Ortona are fatter and with much less refined faces.”Footnote 80

When he began to talk with the doctor Fisher had in hand a book written by the geographer and surveyor T. H. Holdich, a Royal Geographical Society member who wrote widely on India. The doctor was apparently quick to correct Holdich on the history of the British taking of Ceylon in 1796 and the administration of Ceylon. He directed Fisher to the Pali chronicles, including the Mahavamsa: “Ceylon is unique (says the Doctor) in that its annals and its old legends were reduced to writing at a very early period by a Government archivist and historian.” The conversation moved in this manner between Imperial Geography and Buddhist kingly narratives.

When Fisher arrived, he noted in surprise that one elite Sinhalese traveler was received by “a private launch,” and “Six little brown children in gay dresses were brought up the companion way and their Mother held quite a reception on the promenade deck.” This comment is a useful reminder of how the capitalist expansion of Colombo also profited elite Lankans who traveled through the port. If Fisher took an interest in the doctor, his depiction of more common laborers was a telling contrast. His Through India and Burmah with Pen and Brush (1912) begins aboard a ship crossing the Bay of Bengal. He writes of the laborers on board in impersonalized language: “tanks of live humanity”; “a Chinese puzzle”; “Ten chances to one that even if you did manage to avoid stepping on a body you slipped and shot into seven sick Hindoo ladies and a family of children.” He noted that for six first-class European passengers there were 1,700 “Asiatic” deck passengers.

Again, like with the doctor, Fisher's curiosity did get the better of him, and at times this sidestepped Mackinder's racialist views. He converses with a woman and discovers her marital situation and that she is going out to work on paddy fields in Burma; he discovers a Christian, whose husband has run away leaving her with three children in Madras, requiring her to take up work as a ayah [nursing-maid]; and he nurses a “little naked Hindoo baby … her hands like a Nautch dancer.” Despite these flashes of context and personalized relations, his discourse is still unmistakably racialized and structuralist: for instance, he discusses the “Mohammedan,” who was “very fat and greasy” with “one of his dog teeth long like a tusk.”Footnote 81 The image which brings this leg of the journey alive for the reader is an extraordinary example of de-individualization. It is titled: “They Could not Lie Down Without Overlapping.” The original in the Fisher archive, in vivid color, shows the bodies of these laborers in brown merging not only into one another but also into the vessel that carries them (figure 16). Only the blue sea beyond stands out in contrast.Footnote 82 If, following Mackinder, the British Empire had arisen from and raised itself above nature, the people it governed are here flattened out into a mass.

Figure 16 “Indian Coolies on board the Lindula in Bay of Bengal, crossing to work on Burma paddy fields.” Source: box III, RCMS 10, RCS, Cambridge University Library. This image was reproduced in black and white in Alfred Hugh Fisher, Through India and Burmah with Pen and Brush (London: T. Werner Laurie, 1911), 2.

The disjunction between the doctor and the laborers is useful in considering once again the experience of arriving at the port of Colombo. For beyond the visual traces that circulated with ease there was another history of the port, which only emerges in bureaucratized reports. The role of medicine is critical: because of the fear of disease, the port surgeon of Colombo gave regular reports on the sanitary character of the harbor. In these reports is evidence of the port's segregation, which took off in particular in the late 1890s with the spread of plague in India and the quarantining of suspected vessels. In 1896, 175 vessels were placed under quarantine on arriving in Colombo and had to fly the quarantine flag until passed; a Hospital Ship also served the port, where disinfection could be undertaken or sick passengers taken aboard. Footnote 83 By 1905, disinfection was undertaken “at the root of the breakwater” with “an Equifex disinfector [a boiler and three disinfecting chambers]” which was erected at that point alongside an Immigration Depot.Footnote 84 Quarantined vessels were also directed to Galle. The Bombay steamer was a particular target: all Bombay water was carefully emptied off the ship. Each individual on the Bombay steamer was allegedly inspected, their temperature taken, and “the state of the glands of his [sic] neck, groins and armpits” were examined. “Females are examined by a female examiner.” Traders in Bombay protested at the impact of the regime of quarantine on its trade with Ceylon, but the government held to its commitment, claiming that if plague arrived in Ceylon it would make impossible all of its trade with the wider world.Footnote 85

These precautionary measures also took on a bureaucratic form as arrivals were questioned intensively, “as to their whereabouts in India, their accounts of themselves being verified by reference to their diaries or to papers” in their possession. Some who failed these tests were sent back to India. In the end, the Colombo government appointed a medical officer in Tuticorin, so that the paperwork was put in order before laborers docked in Colombo. This general concern with diseased laborers spilled over into a strict regime of regulating the arrival of laborers generally, who, the Port Surgeon noted, were “removed at once upon arrival” to a depot where they were fed and washed and their clothes disinfected. The laborers were treated as objects of manipulation that needed to go through a process of preparation for labor on the plantations: “The coolies, thus clean and refreshed, are entertained and sent on direct to the camp at Ragama [nine miles from Colombo], where they remain in the charge of immigration peons until they can take suitable trains for their respective stations.”

The invisibility of the arriving coolie, taken away directly from the breakwater, is also evident in the fact that Indian laborers arrived at particular times, between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m.Footnote 86 This is in keeping with the argument recently mounted by Valeska Huber for the building of the Suez Canal: she asserts that the canal did not create free movement and mobility so much as it channeled mobility, meaning “the differentiation, regulation and bureaucratization of different kinds of movement.”Footnote 87

The further development of the port of Colombo in the late 1890s and early 1900s effectively emptied it of “native vessels,” a further spatial evacuation. This is why Fisher had to go outside the harbor to get his photograph of fishing vessels. This resulted from the birth of a separate Fishery Harbour in Mutwal in 1902, close to where a concentration of fishermen lived. The historian K. Dharmasena writes, “It provided the Mutwal fishermen with a beaching area three times as big as that area occupied in the harbour.”Footnote 88 This may be true, but running through the papers connected to the administration of the port are complaints about delays in unloading and loading cargoes, and also bids to move the “coal and all the noise and dust far away from the business portion of the town [near the port] and to the neighbourhood where the labourers live.”Footnote 89 Thus the expatriation of fishermen, alongside these other complaints and invectives, arose from a sense that local people were taking up too much space—and this includes visual space—in the new port. Their noise, their presence, and the material they worked with at the port—their boats and the coal—were better made invisible. Tellingly, the dominant motif in the visual culture of the port, which picked up on the Lankan body, did not pertain to coaling or loading or unloading cargoes. The image that recurred was that of “diving boys”: Tamil men diving into the water to retrieve coins thrown into it by watching tourists and visitors. Fisher had this image in his own album and described the divers to Mackinder, and another image was reproduced in the Graphic of 1887, including an inset of “the web-foot of a diving boy.” The periodical article noted, “One of their favourite resorts is inside the Colombo breakwater, where they may be seen struggling and fighting for the possession of any small coins which may be thrown to them.”Footnote 90 So despite the heavy use of labor to make the port and colony work, Lankans at the port are here naturalized and visualized for crude entertainment.Footnote 91

These are the signs of the evacuations brought about by connectivity. The dominance of imperialism and capitalism over the making of connectivity in the high age of empire necessitated the commodification of non-European human beings. This program of racialization took on a particular intensity at the very “nodes of the network,” in the port of Colombo itself. Such an argument tears the connections wrought by the port apart into radically fractured and mutually unobserved passages through it.

CONCLUSION

By 1900, lying beyond the port of Colombo was a complicated and busy city whose social makeup was changing rapidly and where new ideas were brewing among local elite intellectuals. One striking feature of these years was the dominance of non-Sinhalese residents in the city: in 1911 and 1921, the Sinhalese counted for 39 and 35 percent of the people of Colombo, respectively.Footnote 92 There were large numbers of Indian Tamil migrants, Boras, Sindhis, Parsis, Afghans, and Chinese too. Mark Frost is perhaps right to read the heterogeneity of Colombo as indicative of its central place in the Indian Ocean World, and as a sign of its inclusive cosmopolitanism. Such cosmopolitanism, he argues, was championed by the city's bilingual intelligentsia, who adopted Western modes and customs and stitched them together with religious revivalism, temperance, and an interest in the vernacular, and set up new reformist bodies and associations that kept narrower communal nationalism at bay.Footnote 93 Yet there is another, more physical, way of reading the city of Colombo in this period and this comes directly from the port side. For the growth of the port led to a reorganization of the capital: a significant segment of the fort and the area north of Colombo became unbearable to its middle-class and Burgher residents. They moved their pretty mansions south to escape the coal, the noise, and the shops that sprung up to cater to the traffic through the port. In their place arose the slums or “tenement gardens.” Thus developed a differentiated city: on one hand, the richer and greener south and its prized district of Cinnamon Gardens (today's wealthy Colombo 7), and on the other, the poorer north. As one important work on the social history of Colombo holds, the rentiers of these slums were the very people who moved south to better dwellings: “Here in these poverty stricken residential environments one had the foundations for the growth of discontent and the development of working class solidarity.”Footnote 94 Port workers were central agents to the working-class strikes that began to occur by the 1920s: in 1919 the workers of the Harbour Engineers' Department petitioned for an eight-hour day, and the next year five thousand coal “coolies” struck. In 1927, thirteen thousand harbor workers followed suit, five thousand of them coalers.Footnote 95 The divided history of the port becomes here a mirror to the history of the segregated city and the history of class and identity more generally.

Yet is the resonance between contemporary vocabulary and that of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries indicative of a direct relation? For Duncan Bell, a scholar of international political thought, “Today's language of globalization, replete with claims of radical novelty and the ‘annihilation of space and time,’ often simply replicates the way in which the late Victorians interpreted the dynamics of global politics.”Footnote 96 For Bell, the decades at the end of the nineteenth century saw intellectuals borrowing from organicism and the powers of technology to posit a universal empire, which defeated nature and aimed for global reach. Joanna de Groot's recent account of the history of Imperial History in Britain falls in line with this argument. She suggests that histories at the century's turn straddled a wider cultural and popular sphere, while foregrounding a racial view of the critical significance of settlement.Footnote 97 Anthropology, in turn, was increasingly concerned with salvaging the disappearing traces of indigenous peoples, while turning in on British society as an ethnographic site.Footnote 98

While there was a techno-scientific and capitalist specificity to the imperial dreaming of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the global had prior incarnations. The Enlightenment had its own sense of “universal history,” and romantic and stadial views of nature and culture from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries continued to reverberate down the decades into debates about evolutionism. Looking into the twentieth century, the rise of nationalism, decolonization, and the spheres of influence of the Cold War meant that grand visions for a global polity and global connectivity could only have fleeting life. Notions of pan-Asianism, pan-Africanism, or pan-Islam were broken down by concepts of nation, territory, and their relations, in turn, to national historiography, localized fieldwork, or indeed area studies.Footnote 99 The definition of the “Third World” and dependency theory demarcated the “West” from the “rest.” The “British World” is itself now a distant dream. Despite these transformations, the “global” has risen once again in the humanities, borrowing from the technical possibilities of the contemporary world, and its key metaphors such as “network” and “web.”Footnote 100

As a contribution to the historicization of globalization, the present essay is unusual in its attention to visual artefacts alongside imperial ideas and commercial and technical projects. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw a transference of vocabularies and modes of vision. Visual anthropologists and historians of colonial photography are now turning away from an emphasis on photography's indexicality and usefulness for governmentality. This is especially evident in the important work of the South Asianist Chris Pinney, who argues for “eradicable surfeit”: “however hard the photographer tries to exclude the camera lens always includes.”Footnote 101 Pinney points to the surface effects of photographs, or in other words how photographs provide space for vernacular modernisms and de-perspectivalized and de-narrativized rejections of colonial vision. Beyond these intellectual critiques of photography, colonial images, including those from Sri Lanka, can be consulted online or purchased on eBay. They have entered an age of digital spectacle and global marketing. In the words of Lucie Ryzova, they are “orphaned images … like ghosts devoid of any material identity,” entries in databases organized according to image content rather than the indicators of the social context of their origin.Footnote 102 The photographs that have been examined here are of a specific genre. They are of colonial technological advance and are speedy reproductions of the creation of speedy mobility. They come from a time that parallels our own, with its new forms of circulation and a sense of the collapse of distance.

While photographs such as these bear the marks of colonial ideology, they cannot be taken simply as indicators of governmentality, or as an effect or a cause of colonial politics. Rather, colonial photographs harmonize with the metaphors and imaginaries of colonial intellectual disciplines and the markets and finance that sustained empire. They sit together with this broader field of visual production that was critical for envisioning the globe at that time. It is apposite to reconsider colonial photographs as having an equivalent surface effect to that which Pinney charts for subaltern engagements with photography. For the case of the port of Colombo, circuitry and connection “leaked out” as a mode of sight across images, texts, and commercial agendas. Reproduction across forms accentuated the aura of the infrastructure of connection, railways, steamships, and breakwaters.Footnote 103 The lure of the global is apparent here as also the density that is created by the layering of different types of materials, the infrastructure, its global financing, and the imaging of universalist projects.Footnote 104 More work on paths of consumption will make it is possible to trace in even finer detail the means whereby the metaphors of the global spread. Yet attention to the creation and consumption of connection should not lead us to forget its decontextualizing character. Even though Mackinder and his agents aimed for a global view, connections displaced and evacuated: out of the space of the port, beyond the frame of photographs, and in the organization and theorization of intellectual disciplines.

For Mackinder and his colleagues Fisher and Guillemard, points like ports were important for geographical recalibrations, from which the whole world could be reimagined. This was a Social Darwinist and liberal imperialist ideology, according to which humans were products of nature until they rose above it. There was high investment of all kinds in the development of the port of Colombo, such that the circulation and connectivity wrought here was powerful and speedy; it linked traders to tourists, the press to the postcard shop, and the governing elite to the high theorists of empire and their agents. This intersection of interests makes it possible to relate the visual, political, economic, and intellectual makeup of connectivity.

It is telling that one of the most controversial projects undertaken by the government of Sri Lanka, headed by Mahinda Rajapaksa, who left power in 2015, was the building of a new port in his home district in Hambantota, in the extreme south of the island. It was constructed with Chinese investment and Rajapaksa named it after himself.Footnote 105 The agenda was to make cargo ships stop for refueling in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Given this analysis, Rajapaksa's project may be interpreted as intended to reverse the rise of Colombo under British colonialism and to take up the legacy of the port of Galle, which Colombo had killed off in the period examined in this paper. It was a return to the Sinhala south in the aftermath of the end of the ethnic conflict. While Indian observers worried about China's growing involvement in Sri Lanka and its use of Hambantota as one of its “string of pearl” ports, the Rajapaksa regime vociferously denied this accusation and held that India had not objected to this program of development. The island and its ports have thus fallen into the Cold War between India and China in the Indian Ocean. Rajapaksa's building of a port also highlights how an ardently postcolonial regime, suspicious of the West, saw the construction of a port as platform of further legitimacy. This legitimacy took a few shocks: criticisms were aired in Sri Lanka that Hambantota was an ill-chosen port. A huge rock on the seabed impeded progress with the works and had to be blasted away. Just as with British Colombo, the placement of the port has not followed nature, but has instead tried to rise above nature. It was a bid to make connections do political and economic work.

The heavy freighting of colonial connection is such that it continues to resonate and live in our world of technological mobility, and postcolonial as well as transnational politics. The scholar may and should write about connectivity, but this paper has been an attempt to destabilize and interrogate its bases and crevices. Having done so, it is possible to think again about the strengths and omissions of connected histories.