One of the defining features of the Donald Trump administration was its punitive immigration policies. Many of Trump’s prominent campaign promises outlined a comprehensively restrictionist immigration regime, including the further fortification of a wall along the Mexico-U.S. border, the implementation of a “zero-tolerance policy” that saw the separation of migrant children from their parents, and the return of aggressive enforcement by an “unshackled” Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.Footnote 1 Despite these measures and Trump’s own anti-immigration rhetoric that often implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) racialized Latina/o immigrants as threatening, Trump improved upon his 2016 performance and received an estimated 38% of the Latino vote in the 2020 election (Igielnik, Keeter, and Hartig Reference Igielnik, Keeter and Hartig2021). As Latina/o politics scholars noted in the aftermath of the 2016 election, the puzzle has focused less on Latina/o Republicanism itself and more on why so many Latina/os decided to vote “for this particular Republican candidate” (Jones-Correa, Al-Faham, and Cortez Reference Jones-Correa, Al-Faham and Cortez2018, 222).

One prominent explanation for recent changes in Latina/o voting behavior is Democrats’ underperformance with Latino men, as evidenced by exit polls showing Joe Biden winning just 59% of the vote among Latino men compared to 69% of Latinas (New York Times 2020). Although research has shown that Latinas and Latino men differ in terms of their political opinions and political participation (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014; Bejarano, Manzano, and Montoya Reference Bejarano, Manzano and Montoya2011; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998), little work has been devoted to exploring Latina/o gender differences in the policy area of immigration (for an exception, see Lavariega Monforti Reference Lavariega Monforti2017). Perhaps based on the presumption that Latina/o immigration attitudes differ more along ethnic lines or across levels of acculturation, scholars have been less attuned to the possible gender component underlying beliefs in this set of policies. An exploration of Latina/o gender differences in immigration policy is all the more urgent given Trump’s characterization of immigration as “my issue” and his frequently explicit attempts to frame border security as a “women’s issue” (Gypson and Presutti Reference Gypson and Presutti2018; Shear and Davis Reference Shear and Davis2019). Therefore, this study attempts to answer two research questions. First, to what extent do Latinas and Latino men differ in their immigration attitudes? Second, do aspects of intra-Latina/o heterogeneity such as ethnicity, generational status, and connections to immigrants differentially shape the formation of immigration attitudes among Latinas and Latino men?

This study proceeds by reviewing the literature on the Latina/o political gender gap and Latina/o immigration attitudes. I then outline a few a priori reasons why Latinas might be more liberal than Latino men on matters of immigration enforcement based on theories of gender socialization and the gender dynamics of Latina/o acculturation—the Latina/o gender hypothesis. Then, based on the Latina politics literature showing Latinas to be more engaged in cooperation with immigrants through community building and cultural maintenance, I test a research hypothesis that posits these predispositions exert a larger influence among Latinas and account for their greater liberalism on immigration enforcement policy relative to Latino men—the immigrant identity hypothesis.

Latina/o Immigration Attitudes

The immigration attitudes of Latina/os have traditionally been shaped by the immigration experience itself, but those born in the United States now make up a majority of this population. In fact, the foreign-born share of the U.S. Latina/o population has been steadily declining for the last two decades, from a high of 40% in 2000 to 33% in 2019 (Funk and Lopez Reference Funk and Lopez2022). Moreover, Latina/os have arrived in the United States at different times and under a unique set of rules, conditions, and contexts of reception. The diversity of the intra-Latina/o immigrant experience may be one reason why scholars have found that immigration attitudes serve as a source of internal discord within the U.S. Latina/o electorate (Castro, Félix, and Ramirez Reference Castro, Félix, Ramirez, Kreider and Baldino2015; de la Garza and DeSipio Reference de la Garza and DeSipio1992).

What does the field know about U.S. Latina/o views of immigration? Previous work has focused primarily on exploring the dynamics of the structural integration hypothesis, which contends that Latina/os’ immigration attitudes vary based on generational status (Abrajano and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009; Binder, Polinard, and Wrinkle Reference Binder, Polinard and Wrinkle1997; Branton Reference Branton2007; de la Garza and DeSipio Reference de la Garza and DeSipio1992, Reference de la Garza and DeSipio1996; Hood, Morris, and Shirkey Reference Hood, Morris and Shirkey1997; Newton Reference Newton2000). This explains why members of the immigrant generation are typically more sympathetic toward immigrants and supportive of pro-immigration policies, while U.S.-born Latina/os hold more restrictive immigration attitudes (Abrajano and Alvarez Reference Abrajano and Alvarez2010; Abrajano and Singh Reference Abrajano and Singh2009; Branton Reference Branton2007; Polinard, Wrinkle, and de la Garza Reference Polinard, Wrinkle and de la Garza1984; Rocha et al. Reference Rocha, Longoria, Wrinkle, Knoll, Polinard and Wenzel2011; Rouse, Wilkinson, and Garand Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010; Sanchez Reference Sanchez2006; Stringer Reference Stringer2016, Reference Stringer2018). Another key point of intra-Latina/o variation is national origin. Most studies have found that Latina/os of Mexican ancestry tend to hold more liberal immigration attitudes compared to Puerto Ricans and Cubans (Branton Reference Branton2007; Rouse, Wilkinson, and Garand Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010; Knoll Reference Knoll2012).

While previous research has found that Latina/os are more likely to reject immigration restriction in comparison to whites (Buckler, Swatt, and Salinas Reference Buckler, Swatt and Salinas2009; Espenshade and Calhoun Reference Espenshade and Calhoun1993; Rocha et al. Reference Rocha, Longoria, Wrinkle, Knoll, Polinard and Wenzel2011), some Latina/os do express anti-immigrant sentiment. A key concept that explains the tendency among some Latina/os to engage in social distancing from immigrants, the sort that manifests in the form of anti-immigrant or restrictionist attitudes, is “selective dissociation” (Garcia Bedolla Reference Garcia Bedolla2003, Reference Garcia Bedolla2005). Selective dissociation describes the tendency observed primarily among U.S.-born Latina/os to exclude and marginalize Spanish monolingual immigrants because they feel that immigrants deemed “unacculturated” are responsible for inviting social stigma from the cultural mainstream. According to Garcia Bedolla (Reference Garcia Bedolla2005, 94), native-born Latina/os resort to selective dissociation out of a desire to present a more positive group identity, but creating this distance between themselves and immigrant Latinos “results in a decrease in group solidarity and cohesion.” Other scholars have used insights from qualitative research to explore the emergence and maintenance of intra-Latina/o group boundaries between native- and U.S.-born Latina/os. Jimenez’s (Reference Jiménez2007, 601) study of Mexican Americans in Kansas and California found them to be often ambivalent about increased Mexican immigration because restrictionist Mexican Americans “fear that the nativism Mexican immigrants attract leads to status degradation for all people of Mexican origin.” In a similar vein, Vega (Reference Vega2014) found that Mexican Americans classified as immigration restrictionists create “us” (American) versus “them” (foreigners) distinctions to justify violations of ethnic solidarity with Mexican immigrants.

Less is understood about the potential for gender dynamics to inform patterns of selective dissociation or other modes of intra-Latina/o social distancing. If the acculturation process is broadly associated with greater liberalization among Latinas (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014), then this ideological transformation may limit the adoption of restrictionist enforcement attitudes more for Latinas than for Latinos. Additionally, if (1) Latinas traverse social spaces like schools, churches, and neighborhoods where greater interaction with immigrants is more common and/or (2) occupy distinct labor market sectors associated with care work, then it could also be that opportunities for selective dissociation are further constrained (Donato and Perez Reference Donato and Perez2016; Ochoa Reference Ochoa1999, Reference Ochoa2000). By contrast, acculturation and social integration of Latino men in the United States may produce lower social costs to engaging in “selective dissociation” or adopting punitive orientations toward immigration enforcement. The role of socially constructed pressures to fulfill gendered expectations and their intersection with acculturation is discussed at greater length in the following section.

Theoretical Expectations

Theoretical expectations are subdivided into three broad categories and discussed sequentially from the broadest level of conceptualization to the most proximate. I begin with relevant theories of gender socialization, including social role theory, which broadly underlies attitudinal differences in this policy area. Then I look to insights from the Latina politics literature exploring the unique specificities of gender within the Latina/o acculturation process. Finally, I review studies examining gender differences in Latina/o attitudes on topics adjacent to immigration policy.

Gendered Socialization and Social Role Theory

What is the basis for analyzing the politics of U.S. immigration enforcement attitudes through the lens of gender? Despite the extensive literature about the role of gender in voting behavior and public opinion (for a review of gender gap literature, see Ondercin Reference Ondercin2017; see also Howell and Day Reference Howell and Day2000), few works in American politics research have outlined the theoretical basis for why men and women (regardless of race-ethnicity) might differ in their attitudes on this set of policies. Insights from social role theory (Eagly, Wood, and Diekman Reference Eagly, Wood, Diekman, Eckes and Trautner2000) provide a useful framework for explaining the greater liberalism on the part of women and greater conservativism on the part of men in certain policy areas. Social role theory holds that observed differences in behavior and attitudes are not the result of essentialized (biological) differences between the sexes but instead are attributable to socially constructed pressures to conform to gender norms. Social role theory’s application to the study of politics (for a review, see Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019) contends that social roles and psychological processes produce macro-level outcomes like differences in the political attitudes of men and women in their orientations to egalitarian political principles and to “compassion issues.” In this sense, the social pressure for women to fulfill gendered expectations or to exhibit female-coded traits based on their roles as “caregivers” and for men to adopt masculine-coded traits associated with their role as “providers” might produce different political attitudes.

Studies of gender differences in “compassion issues” have found that women are more supportive of policies benefiting marginalized groups such as social welfare spending for the poor, children, and the elderly (Shapiro and Mahajan Reference Shapiro and Mahajan1986). More recently, there have been efforts to disaggregate analysis according to race-ethnicity in order to “consider the effects of gender in conjunction with other key political identities” such as race, ethnicity, and class (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019, 174). Montoya (Reference Montoya1996) brought the first extensive focus on gender differences in public opinion between Latinas and Latinos and found that Latinas in the aggregate and across all national origin groups were more likely to favor egalitarian roles for women. A later study by Garcia Bedolla, Lavariega Monforti, and Pantoja (Reference Garcia Bedolla, Lavariega Monforti and Pantoja2007) strongly emphasized the magnitude of the Latina/o gender gap, finding Latinas to be more liberal than Latino men on three of the six issues examined (mother’s responsibility in the religious upbringing of their children, support for the death penalty, and support for gun control). A race-gender analysis across a range of “caregiving issues” (poverty/welfare, education/children, health care, and women’s rights) found that “Hispanic women particularly stand out as champions of these issues” (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2022, 175). Other work has questioned the magnitude of the Latina/o gender gap across a range of issues. Though Bejarano, Manzano, and Montoya (Reference Bejarano, Manzano and Montoya2011) found that Latinas were more egalitarian than men on matters related to childcare responsibilities, the political leadership capabilities of women, access to contraception, and equal pay, they noted that aggregate gender gaps and those across immigration generation were relatively modest.

Meanwhile, the application of marginality theory (Fetzer Reference Fetzer2000) would suggest that because women in society are subject to marginality or oppression from heteropatriarchal systems, such experiences may lead to greater sympathy for other marginalized or oppressed groups. The cultural relevance of the issue of immigration which features so prominently in the U.S. Latina/o community may add additional pressures to sympathize with vulnerable groups when the marginalized groups in question are predominantly undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers from Latin America. Therefore, the dual insights of social role and marginality theory may very well apply to this study of immigration attitude differences, since women (and Latinas specifically) might have multiple reasons for approaching the issue from a different perspective than Latino men.

The Role of Gender in Latina/o Immigration Acculturation

The second set of theoretical expectations for why Latinas might adopt more liberal (and Latino men more conservative) positions on immigration enforcement relates to gender socialization and its intersection with the dynamics of acculturation. Specifically, Hardy-Fanta’s (Reference Hardy-Fanta1993) foundational case study of Boston’s Latina/o community provides a useful lens through which to approach the gendered dimensions of immigration attitudes. Differences between Latinos’ and Latinas’ conception of politics as outlined by Hardy-Fanta (Reference Hardy-Fanta1993, 189) highlight how Latinas rely on relationships achieved through an “interpersonal, interactive process—building bridges and making connections between people” even across lines of citizenship status. Hardy-Fanta found Latina-led organizations to be the most actively engaged in the mobilization of immigrant community members and concluded that “it is Latina women, not Latino men, who best illustrate effective strategies for the development of citizenship by providing participatory experiences in politics for Latinos who are not legal citizens” (120).

Work by Ochoa (Reference Ochoa1999, Reference Ochoa2000) exploring Mexican American women’s patterns of resistance on behalf of and cooperation with immigrants in Southern California came to a similar conclusion as Hardy-Fanta. Ochoa demonstrated how Mexican American women of later generations engage in bridge building and solidarity work with Mexican immigrants through their greater participation in third spaces outside the home like schools, churches, and neighborhoods where the traversal of group boundaries with immigrants are more frequent. Ochoa’s (Reference Ochoa2000, 84) analysis of Mexican American and Mexican immigrant social relations showed how Latinas may be in “unique positions to make connections with immigrants that foster intraethnic solidarity.” Ochoa acknowledged that the Mexican American women in her study engaged in forms of resistance like publicly supporting Spanish-language instruction and bilingual education programs alongside Mexican immigrants in part because Latinas are often expected to be responsible for cultural maintenance and transmission within their families and communities.

The insights from Ochoa’s qualitative research have since been supported by quantitative analysis of Latina/o attitudes and the gender dynamics of the immigrant acculturation process. In her investigation of gender’s role in shaping the maintenance of pan-ethnic identity and the acquisition of American identity, Silber Mohamed (Reference Silber Mohamed2015, 45) found that Latinas are not only less likely than Latino men to strongly identify as “American” but also “significantly more likely to very strongly identify as Hispanic/Latino, and to express support for maintaining a distinct pan-ethnic culture.” The unique gendered dynamics of immigrant acculturation in the United States might also affect immigration attitudes. For one, research has found a unique interaction between gender and generational status in which a Latina/o ideological gender gap emerges as Latinas become more liberal and Latino men becoming more conservative with rising levels of acculturation (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014). Donato and Perez (Reference Donato and Perez2016, 112) suggested that the reason for Latinas’ liberalization may be their greater engagement with schools, the public sector, and nonprofit institutions, while Latino men’s conservatism might emerge through their greater involvement with private, for-profit institutions. Taken together, these insights from the Latina politics literature suggest that Latinas are more likely to view the prospect of increased immigration through a positive-sum (or additive) lens rather than through the lens of competition and conflict. If so, then Latinas could be more inclined than their Latino male counterparts to consider how native-born populations might benefit from increased immigration.

The Gender Component in Latina/o Immigration Enforcement Attitudes

A cursory review of the literature on gender differences in American public opinion finds that scholars have rarely examined gender differences specifically in matters of immigration, with most studies focusing on culture war issues or gender-coded policy domains. Therefore, another way to ground the expectations of this study is to rely on findings from previous empirical investigations about policy domains that share similarities with immigration policies and enforcement to supplement the inconsistent findings that emerge from the few examples that examine gender difference in Latina/o immigration attitudes.

There are reasons to suspect that U.S. Latinas might be more liberal, and Latino men more conservative, on the issue of immigration enforcement. First, immigration enforcement in the United States since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, has become increasingly militarized. Following the steady rise in the militarization of the Mexico-U.S. border since the 1990s (Nevins Reference Nevins2010) and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s association with the war on terror after 9/11, U.S. immigration enforcement now shares many characteristics with other masculine-coded domains,Footnote 2 including military intervention, foreign policy, and crime and punishment. For example, the contemporary language of immigration enforcement both at the nation’s borders and in its interior relies on displays of strength and the use of force to appeal to traditional forms of masculinity (Sampaio Reference Sampaio2014, Reference Sampaio2015).

Second, established gender gaps in support for the use of force or military intervention might spill over into immigration policy attitudes given that many of the current immigration enforcement policy “solutions” imply increased funds for militaristic approaches (more “boots on the ground” at the border), additional investments in surveillance technologies and militarization, and greater involvement from law enforcement agencies. For example, research has found that women are less supportive of force and torture (Huddy, Cassese, and Lizotte Reference Huddy, Cassese, Lizotte, Wolbrecht, Beckwith and Baldez2008; Lizotte Reference Lizotte2017) and more reluctant to support military force in general (Conover and Sapiro Reference Conover and Sapiro1993). VanSickle-Ward and Pantoja (Reference VanSickle-Ward, Pantoja, Brown and Gershon2016) identified a similar tendency among Latinas, who were found to be less supportive of U.S. military intervention in Iraq compared to their Latino male counterparts. These findings in the realm of foreign policy fit with the broad pattern originally identified by Garcia Bedolla, Lavariega Monforti, and Pantoja (Reference Garcia Bedolla, Lavariega Monforti and Pantoja2007), who demonstrated that Latinas exhibit lower support for “use of force” issues (death penalty and guns) in the domestic policy context. This strand in the literature showing Latinas’ greater disinclination to endorse policies involving the use of force might apply to the area of contemporary immigration enforcement which has come to share many traits of militarization.

Third, it may be the case that the change in migration flows to include the arrival of more women, children, and family units to the Mexico-U.S. border alongside exceptionally cruel Trump administration policies has magnified the potential for different attitudinal responses along the lines of gender. Regarding the change in arrivals at the southern U.S. border, one major trend of the last decade has been the growing number of child migrants attempting to enter the United States. According to one estimate, the number of unaccompanied children apprehended by U.S. Customs and Border Protection increased 17-fold between fiscal years 2008 and 2021 (TRAC 2022). The share of women, especially from Central America, migrating to the United States has also been rising. For example, the proportion of migrant women apprehended by both Mexican and U.S. authorities nearly doubled in both countries between fiscal year 2012 and fiscal year 2017, from 13% to 25% and from 14% to 27%, respectively (Hallock, Ruiz Soto, and Fix Reference Hallock, Soto and Fix2018). Not only does this mark a change in the actual composition of migrants, it also contrasts with the U.S. media’s tendency to significantly overrepresent Latino men as the stereotypical undocumented immigrant (Silber Mohamed and Farris Reference Silber Mohamed and Farris2020). Thus, the implementation of aggressive “zero-tolerance” policies targeting a rising share of Latin American women and child migrants may increase gendered social pressure among Latinas, who are expected to adopt female-coded responses like empathy and care to such harsh immigration enforcement policies.

The few studies that have paid some attention to the role of gender in immigration attitudes have arrived at conflicting conclusions. For many years, the consensus had been that Latino men and Latinas largely share similar positions on the issue of immigration (Binder, Polinard, and Wrinkle Reference Binder, Polinard and Wrinkle1997; Branton Reference Branton2007; de la Garza et al. Reference de la Garza, Polinard, Wrinkle and Longoria1991; Hood, Morris, and Shirkey Reference Hood, Morris and Shirkey1997; Knoll Reference Knoll2012), as bivariate and multivariate results yielded few significant gender differences. The first study to devote more significant attention to gender’s role in Latino immigration attitudes found Latinas to be more restrictive (Rouse, Wilkinson, and Garand Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010). Yet even Rouse and colleagues only found significant effects for Latinas’ greater immigration conservatism in two of their dependent variables: the cumulative pro-immigration scale and disagreement with the statement that “illegal immigrants help the economy.”

More recently, a series of studies have suggested a changing pattern in Latina/o immigration attitudes. For example, Lavariega Monforti’s (Reference Lavariega Monforti2017) examination of the Latina/o gender gap in the 2016 presidential election included an analysis of Latina and Latino issue positions on three policies: support for DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), support for immigration reform, and the degree to which immigration informed vote choice. Though her exploration was limited to the bivariate level, Lavariega Monforti (Reference Lavariega Monforti2017, 237) found that Latinas tend to “support DACA and immigration reform efforts more strongly than do their male counterparts.” In their study comparing opinions regarding opposition to the border wall between Latinos nationwide with those of Latinos residing in the border communities of south Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, Kim, Kim, and McNeely (Reference Kim, Kim and McNeely2022, 15) found a significant gender effect, but only in their analysis of the national Latino sample. Specifically, the authors found that nationwide (though not in the Rio Grande Valley), “Latinas are about 8% more likely to oppose a border wall than Latino males, all else equal.” These recent findings prompt a consideration of why Latino men might be exhibiting a greater tendency and Latinas a lesser tendency to endorse punitive immigration enforcement policies, which I outline in the next section.

Hypotheses

Based on the insights of social role theory, gender differences in Latina/o acculturation processes, and previous findings exploring intra-Latina/o gender differences in immigration attitudes and similar policy domains, I forward two hypotheses: the Latina/o gender hypothesis and the immigrant identity hypothesis. The Latina/o gender hypothesis simply tests for the presence of positional differences between Latinas and Latino men on the issue of immigration enforcement and policies toward undocumented immigrants.

H1: Compared to Latino men, Latinas will be less likely to express restrictive immigration enforcement attitudes.

Then, based on insights from the Latina politics literature showing Latinas to be more engaged in cooperation with immigrants through community building and cultural maintenance, I test the immigrant identity hypothesis, which posits that commonality with immigrants accounts for structural differences between Latinas’ and Latino men’s immigration enforcement attitudes. Immigrant commonality is measured using responses to the following question: “Thinking about issues like job opportunities, income and educational attainment, how much do you have in common with each of the following groups? Immigrants.”

H2: Commonality with immigrants will have a greater and more consistent impact on immigration enforcement attitudes among Latinas than Latino men, all else equal.

Data

To test the research hypotheses posed in the previous section, I analyze the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) because it includes a sufficiently large (n = 4,006) sample of Latina/o voters (Frasure et al. Reference Frasure, Wong, Barreto and Vargas2021). The Supplementary Material includes a bivariate analysis of Latina/o gender differences in immigration enforcement questions using the Cooperative Election Study (CES). However, because the CES is only fielded in English, the lack of Spanish-language surveys means that the CES Latino sample may be biased toward more acculturated Latinos. Therefore, I decided to use the CMPS as the primary data set for this analysis. Unlike the CES, which includes both pre- and postelection surveys (Ansolabehere, Schaffner, and Luks Reference Ansolabehere, Schaffner and Luks2021), the CMPS is a postelection survey collected in a self-administered online format between April 2 and August 25, 2021. A total of 688 Latino interviewees (23.43% of the weighted Latino sample) completed a Spanish survey.

Results: Bivariate

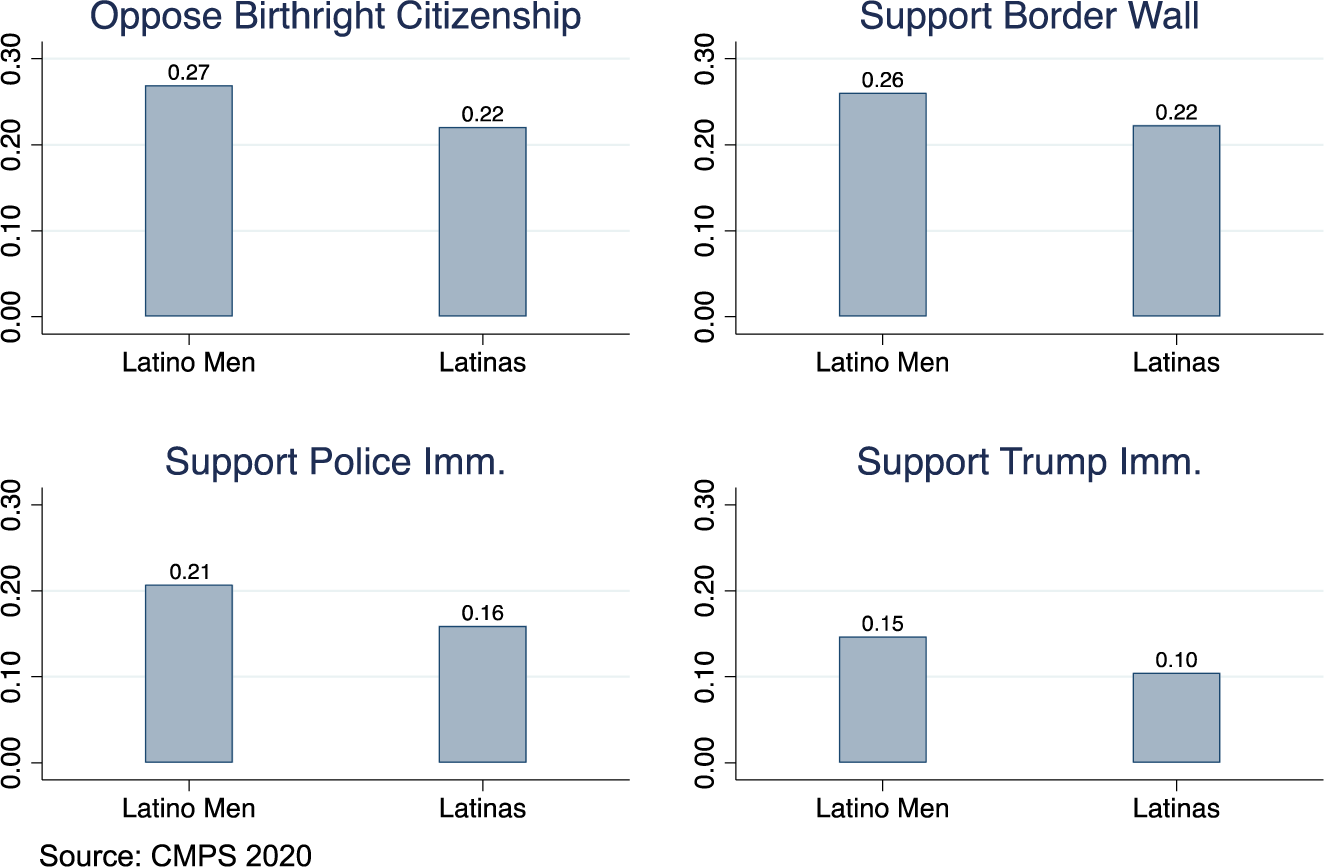

Table 1 displays the share of the Latino men and Latinas in the 2020 CMPS who express conservative immigration enforcement attitudes. The results from difference of means tests between Latinos and Latinas show initial support for H 1 at the bivariate level. Evidence suggests the presence of an empirically meaningful gender gap across all five of the CMPS immigration enforcement questions, with Latino men significantly more likely to hold restrictive positions. Overall, about one-third of Latino men compared to about one-quarter of Latinas report the more conservative issue position. In the CMPS sample, the gaps between Latinas and Latinos in this policy area range from 4 to 9 percentage points, with the largest gap observed in the question asking about support for “President Trump’s immigration policies, including deportation, detention and how the US treats people seeking asylum.” Analysis of the CES 2020 sample (see Table A1 in the appendix for the CES 2020 results) also provides initial confirmatory evidence for H 1 , as Latinas are less likely to adopt the pro-enforcement and restrictionist position than Latino men by a range of 7 to 11 percentage points.

Table 1. Gender gaps in restrictive immigration attitudes among Latina/os (percent)

Notes: Cell entries represent percentages of respondents. All percentages were derived using weights (CMPS “weight”). The “oppose amnesty” question was asked of a randomly selected half of sample respondents.

* p < .05.

Results: Multivariate Regression

Having established initial bivariate level support for a gender gap in immigration attitudes between Latinas and Latinos, I turn to multivariate analysis to test whether gender differences persist after controlling for a range of factors that might also influence these positions. The multivariate regression analysis proceeds in two sections: the first section tests whether being Latina rather than Latino is associated with more liberal immigration positions net of other factors as represented by H 1 , the Latina/o gender hypothesis. The second set of models tests for the immigrant identity hypothesis, which considers whether the factors that influence Latina and Latino immigration attitudes are different.

In addition to the key independent variable for gender, the multivariate analysis controls for a standard set of demographic factors (ethnic ancestry, generational status, age, educational attainment, income, Evangelical identity) and political variables including ideology and partisanship. Importantly, the CMPS dataFootnote 3 allows for testing key aspects of Latina/o’s immigrant identity and their self-reported level of commonality with “immigrants” (see the appendix for variable coding).

Table 2 displays the results from a series of logistic regressions conducted on the same five 2020 CMPS questions included in Table 1 (support for greater police involvement in matters of immigration, support for Trump immigration policies, support for border wall funding, opposition to birthright citizenship for the children of noncitizens, and opposition to amnesty). For ease of interpretation across the models, coefficients are presented as exponentiated odds ratios (O.R.), such that significant values above 1 denote positive relationships and values below 1 denote negative relationships between independent and dependent variables.

Table 2. Logistic regressions predicting restrictive immigration attitudes among Latina/os

Notes: Exponentiated coefficients; standard errors in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Source: CMPS 2020.

Results show strong support for

H

1

, as Latinas are statistically less likely to express the restrictive position than Latino men in four of the five immigration enforcement questions. The variable for Latina is most strongly associated with a lower likelihood of support for involving police in immigration enforcement (O.R. 0.73, p

![]() $ \le $

.001) and support for Trump’s immigration policies (O.R. 0.68, p

$ \le $

.001) and support for Trump’s immigration policies (O.R. 0.68, p

![]() $ \le $

.001), which suggests that Latinas are especially disinclined to encourage greater surveillance of immigrants and the most aggressive postures toward the undocumented and asylum seekers relative to Latino men. Supplementary analysisFootnote

4 contained in the methodological appendix (see Table A2) also shows that Latinas are statistically less likely to adopt the restrictionist and pro-enforcement position than Latino men across all seven models. These findings comport with Ochoa’s qualitative insights suggesting that Latinas are more likely to engage in intergenerational bridge building activities with immigrants. In explaining why Mexican American women tended to align themselves with Mexican immigrants, Ochoa (Reference Ochoa2000, 95) states that women reported “situations where they have countered anti-immigrant or anti-Mexican sentiment or have provided assistance to immigrants” by “using their positions as neighbors, school employees, and church members to make connections with immigrants.”

$ \le $

.001), which suggests that Latinas are especially disinclined to encourage greater surveillance of immigrants and the most aggressive postures toward the undocumented and asylum seekers relative to Latino men. Supplementary analysisFootnote

4 contained in the methodological appendix (see Table A2) also shows that Latinas are statistically less likely to adopt the restrictionist and pro-enforcement position than Latino men across all seven models. These findings comport with Ochoa’s qualitative insights suggesting that Latinas are more likely to engage in intergenerational bridge building activities with immigrants. In explaining why Mexican American women tended to align themselves with Mexican immigrants, Ochoa (Reference Ochoa2000, 95) states that women reported “situations where they have countered anti-immigrant or anti-Mexican sentiment or have provided assistance to immigrants” by “using their positions as neighbors, school employees, and church members to make connections with immigrants.”

Figure 1 displays the predicted probabilities of reporting the conservative position on matters of immigration enforcement using a prototypical respondent setting all continuous variables at their mean and dichotomous variables at their modal values, except for gender. The results for these otherwise identical Latino men and Latinas show that Latinas are 4% to 6% less likely to harbor the restrictionist position on immigration enforcement policies.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of reporting the conservative/restrictionist position on immigration enforcement and attitudes toward undocumented immigrants among Latino men and Latinas. The figure includes only models from Table 2 in which differences between Latino men and Latinas were statistically significant. Predicted probabilities were derived with all continuous variables held at their means and dummy variables held at their modal outcomes, except gender. The prototypical respondent is one of Mexican ancestry, first-generation immigrant, not a college graduate, reported an income level, reported a partisan identity, reported an ideology, and does not identify as “born-again.”

Table 2 also shows that greater commonality with the immigrant community (statistically significant in three of the five models) is negatively associated with restrictive immigration attitudes. Whereas being Latina and expressing greater commonality with Latino immigrants are significantly and negatively related to support for more police involvement in immigration, Trump’s immigration policies, and the border wall, the variable for Latina is also significant for predicting less opposition to birthright citizenship, whereas immigrant commonality is not. Moreover, the negative relationship between being Latina and support for the use of the police in matters of immigration is stronger (p

![]() $ \le $

.001) compared to the negative relationship with commonality with immigrants in the same model (p

$ \le $

.001) compared to the negative relationship with commonality with immigrants in the same model (p

![]() $ \le $

.05), demonstrating that gender is a stronger and more consistent factor in shaping immigration attitudes than a Latina/o respondent’s level of solidarity with immigrants.

$ \le $

.05), demonstrating that gender is a stronger and more consistent factor in shaping immigration attitudes than a Latina/o respondent’s level of solidarity with immigrants.

What is more, the gender effect persists even after controlling for a host of other factors that the models suggest also influence immigration attitudes among Latina/os, including ethnic ancestry, generational status, and one’s reported sense of commonality with immigrants. In terms of differences among Latina/o respondents according to ethnic ancestry, I find that Cuban and South American respondents display a greater tendency (two of the five models) to adopt the restrictionist attitude relative to Latina/os of Mexican ancestry, who serve as the excluded reference category. On both occasions, Cubans and South Americans are more likely than Mexicans to support Trump immigration policies and the construction of the border wall. The result for Cubans follows the well-established tendency among Latina/os of Cuban ancestry to adopt more conservative policy positions compared to non-Cuban Latina/os. Puerto Ricans are more likely to support border wall construction, and respondents reporting an ancestry in Spain or some other Latina/o ancestry are more likely to oppose birthright citizenship (relative those with ancestral roots in Mexico). These findings are generally in keeping with previous literature finding that Latina/os of Mexican descent are generally more liberal on matters of immigration (Branton Reference Branton2007; Knoll Reference Knoll2012; Rouse, Wilkinson, and Garand Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010) and that they displayed unique levels of politicization in the 2016 election in response to Trump’s overtly racist attacks directed toward immigrants from Mexico (Garcia-Rios, Pedraza, and Wilcox-Archuleta Reference Garcia-Rios, Pedraza and Wilcox-Archuleta2019).

Insofar as generational status differences are relevant for immigration enforcement among Latina/os, those of the third and later generations are more likely to hold restrictionist attitudes compared to first-generation immigrants. The variable for third generation is statistically significant in all the models except for opposition to birthright citizenship, whereas the variable for denoting respondents of the second generation is statistically significant for its positive association with opposition to amnesty (relative to the foreign-born). The findings regarding generational status differences underscore the extent to which distance from the immigrant experience influences Latina/os views of present-day immigration politics. It also suggests that the transition from the second to the third generation (in other words, the difference between having at least one foreign-born parent among the U.S.-born) is more influential in shaping Latina/o immigration attitudes than the difference between the first and the second generation.

As expected, ideology and partisanship were significant predictors of immigration attitudes. Movement on the 7-point ideology and partisanship scales, toward more conservatism on the former and movement toward stronger Republican identification on the latter, are positively associated with embracing the restrictive position across all five dependent variables. While previous literature has found economic self-interest to be largely unrelated to immigration attitudes (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014), I find that increasing incomes among Latina/os is significantly associated with support for Trump’s immigration policies and greater opposition to automatic birthright citizenship for the children of noncitizens.

Next, I examine structural differences between Latina and Latino immigration attitude formation. To do so, the same set of CMPS models were run separately among Latinas and then Latinos to test whether certain factors influence immigration attitudes more among one group. As a reminder, H 2 stipulates that immigrant commonality would have a greater impact on Latina immigration attitudes. This expectation was based on insights about Latinas’ tendency to engage in community building and cooperation across differences in generational status and from social role theory’s suggestion that women are socialized to draw upon communal traits (such as caring, kindness, and empathy) more so than men especially with vulnerable populations such as undocumented immigrants and asylums seekers.

Tables 3 and 4 display results from a split-sample analysis among Latinas and Latino men, respectively. I find partial support for H 2 , which posited that feelings of commonality with immigrants would be a stronger and more consistent predictor of immigration enforcement attitudes among Latinas compared to Latino men. Although rising self-reported commonality with immigrants is negatively associated with immigration restrictionism among both Latino men and Latinas, the variable only attains statistical significance in one of the five models among the former (support for Trump immigration policies), whereas it attains statistical significance in three of the five models among the latter (support for Trump immigration policies, support for construction of the border wall, and opposition to amnesty for undocumented immigrants). I acknowledge that these results should be interpreted with caution since a statistically significant coefficient in one model does not mean the difference between the effect among Latinas and Latinos is meaningful. Therefore, these findings provide only suggestive evidence that Latinas’ immigration enforcement attitudes are more firmly tethered to a sense of unity and solidarity with immigrants in society and opposition to punitive immigration measures.

Table 3. Logistic regressions predicting restrictive immigration attitudes among Latinas

Notes: Exponentiated coefficients; standard errors in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Predictor variable for Dominican in “oppose amnesty” model was dropped due to lack of variation.

Source: CMPS 2020.

Table 4. Logistic regressions predicting restrictive immigration attitudes among Latino men

Notes: Exponentiated coefficients; standard errors in parentheses. * p < .05; ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Source: CMPS 2020.

Figure 2 displays the predicted probabilities of Latinas support for Trump’s immigration policies and support for the border wall position for a prototypical Latina respondent after setting all continuous variables at their mean and dichotomous variables at their modal values, with the exception of commonality with immigrants. The results indicate that changing a Latinas’ commonality with immigrants from the minimum to maximum level is associated with a 6 percentage point decline in the probability of adopting the restrictionist opinion.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of reporting the conservative/restrictionist position on the questions asking about support for Trump’s immigration policies “including deportation, detention and how the US treats people seeking asylum” and support for “$25 billion on border security, including building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico” among Latinas according to levels of commonality with immigrants. Predicted probabilities were derived with all continuous variables held at their means and dummy variables held at their modal outcomes, except Latinas’ self-reported commonality with immigrants. The prototypical respondent is one of Mexican ancestry, first-generation immigrant, not a college graduate, reported an income level, reported a partisan identity, reported an ideology, and does not identify as “born-again.”

Intercultural differences according to national origin are also shown to be somewhat distinct between Latinas (Table 3) and Latino men (Table 4). First, the effect of ethnic ancestry is shown to be most pronounced on the topic of support for the construction of the border wall especially among Latinas, with Cuban, Puerto Rican, Dominican, and South American Latinas all more likely to support this policy compared to Latinas of Mexican origin. By comparison, only men of Cuban descent are distinct in their greater level of support for this measure. Furthermore, Latinas of Cuban ancestry register as measurably more conservative in two of the policies compared to just one in the model limited to Latino men. The positive relationship between Cuban ancestry and support for the border wall is stronger in the Latina model (O.R. 1.92, p

![]() $ \le $

.01) than it is in the model for Latino men (O.R. 1.83, p

$ \le $

.01) than it is in the model for Latino men (O.R. 1.83, p

![]() $ \le $

.05).

$ \le $

.05).

Second, although the control for Puerto Rican does not attain statistical significance in any of the models for Latino men, Latinas of Puerto Rican descent are more likely to support construction for the border wall compared to their counterparts with Mexican ancestry. Interestingly, however, Latinas of both Puerto Rican and Cuban ancestry are shown to be less likely to oppose amnesty for the undocumented compared to Latinas of Mexican descent in the excluded reference category. Although this result is somewhat unexpected, I interpret it by speculating that Cuban and Puerto Rican women may justify their desire for limiting new unauthorized entries with flexibility elsewhere for unauthorized immigrants already present in the United States who display their law-abiding background for earned citizenship. This dynamic would suggest that Latinas of Cuban and Puerto Rican ancestry may display a greater inclination to differentiate between what scholars refer to as “stock” (non-naturalized immigrants already present in the country) and “flow” (future arrivals of foreigners seeking to enter and live in the country) and to show greater tolerance for the former rather than the latter (Margalit and Solodoch Reference Margalit and Solodoch2022). Alternatively, Latinas of Cuban and Puerto Rican ancestry may display a greater inclination to accepting amnesty provisions contingent upon harsher border enforcement measures.

A third notable finding regarding national origin differences from the analysis of Tables 3 and 4 is that Latinas of South American descent show a predisposition toward greater immigration restrictionism compared to Latinas of Mexican descent in the questions regarding support for Trump’s immigration policies and the border wall construction. Research has only recently begun to unpack the political attitudes of some South American Latina/o communities in the United States (see Ocampo and Ocampo Reference Ocampo and Ocampo2020), but more research is required to fully understand these growing populations.

Proximity to the immigrant experience also serves as another point of differentiation between Latinas and Latino men. Whereas second- and third-generation Latino men are more likely to express the conservative opinion compared to foreign-born Latino men in one instance (opposition to granting amnesty), generational status differences are statistically meaningful cleavages among Latinas in two of the five models. Specifically, U.S.-born Latinas of both the second and third generations are more likely to support greater police involvement in immigration enforcement and are more likely to support Trump’s punitive immigration policies. This suggests that while on whole Latinas may be less likely to harbor restrictionist immigration attitudes compared to Latino men and are more influenced by their sense of commonality with immigrants, their policy positions may be slightly more contingent upon differences in generational status relative to their male counterparts.

Controls capturing the effect of socioeconomic status and class dynamics in relation to immigration attitudes appear to be less impactful for the attitudes of both Latinas and Latinos. For one, the variable for a college degree is not significant in any of the models for Latino men and a negative relationship between a college education and support for the border wall is the only one that attains statistical significance among Latinas. When economic status is associated with immigration restrictionism it is those Latinas and Latino men of higher incomes who are shown to be more in favor of Trump immigration policies and more opposed to birthright right citizenship, respectively. This suggests that arguments linking economic vulnerability of lower- and working-class Latinos with anti-immigrant sentiment receive little empirical support.

Lastly, I find that the immigration attitudes of both Latinas and Latino men are profoundly influenced by both ideology and partisan attachments. Though perhaps somewhat less surprising, ideological conservatism and stronger Republican identities among Latinas and Latinos are strongly associated with support for more punitive immigration enforcement measures. Movement on the ideological scale toward greater conservatism was statistically significant and positive in all five models for Latinas and in four models for Latino men (opposition to birthright citizenship the lone exception), while movement on the 7-point partisanship scale toward deeper Republican attachment was significant in all five models for Latino men and in four models for Latinas (all but opposition to amnesty). This suggests though conservative beliefs and association with the Republican Party are deeply intertwined with punitive immigration enforcement policies even among Latina/os, policies meant to incorporate undocumented immigrants with deeper ties to the United States may be the one area in which ideological and partisan identities are somewhat less predictive.

Discussion

This study contributes insights to the field of Latino politics, which has been grappling with the significance of the levels of support that Trump garnered among Latinos (Jones-Correa, Al-Faham, and Cortez Reference Jones-Correa, Al-Faham and Cortez2018). The fact that Trump secured roughly a quarter of the Latino vote in 2016, then likely increased his share to about a third of all Latinos in 2020, all the while delivering stridently anti-immigrant policies, posed a puzzle for scholars. A popular media narrative that arose during the lead-up to the 2020 election was that Trump’s popularity among Latina/os was driven at least partly by Latino men who gravitated to the candidate’s macho bluster (Medina Reference Medina2020), but an analysis of sexism’s impact “failed to detect differences” between Latino men and Latinas (Hickel and Deckman Reference Hickel and Deckman2022, 15). In their review of literature following the results of the 2016 election, Jones-Correa, Al-Faham, and Cortez (Reference Jones-Correa, Al-Faham and Cortez2018, 216–17) noted that although scholarship has established that Latinas and Latinos exhibit different political attitudes and behaviors, the field still needs a “better understanding of the mechanisms underlying these differences.”

Despite the range of literature on the gender gap in public opinion, comparatively few studies, whether studying gender differences broadly or Latina/os only, have focused specifically on the potential gender component to immigration attitudes. Given that Abrajano and Hajnal (Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015) found immigration policy attitudes to be the most powerful issue driving whites’ desertion from the Democratic Party since the 1980s, it is reasonable to suspect that immigration politics has also exerted an influence on the voting patterns of other groups including Latina/os. The analysis herein has tried to provide some advancement for the field of Latino politics as well as for scholars exploring the intersection of gender and race-ethnicity in public opinion.

To summarize, I formulated a set of expectations based on theoretical frameworks from social role theory and from insights about the gender dimensions of Latina/o acculturation processes. Building on work from the Latina politics literature showing that Latinas are more likely to engage in solidarity work with immigrants and have a greater desire for cultural transmission and the maintenance of pan-ethnic identity, I tested two hypotheses. I found strong support for the Latina/o gender hypothesis, which postulated that Latinas would adopt more liberal immigration attitudes relative to Latino men. I also found some support for the immigrant identity hypothesis pertaining to structural differences in the underlying factors animating the immigration enforcement and immigration restrictionism opinions of Latinas and Latino men.

One limitation of this study is that it is based on cross-sectional data, and although findings were checked for robustness using an alternative data set, future work should extend this line of inquiry using different methodological approaches. Panel data tracking respondents over time and/or qualitative evidence would likely add further insights about why individuals adopt or change their attitudes in response to real-world politics or in this case, migration flows and policies. For example, one potential factor leading to a gender attitudes gap in Latina/o immigration attitudes (and gaps among other groups) could be in response to the changing nature of U.S. migration flows. Specifically, U.S. migration flows have been increasingly comprised of unaccompanied migrant children, with images and news stories of asylum seekers and those in immigration detention facilities including a greater number of minors. This marks a change from the prototypical immigrant as a working-age single male that dominated the images of U.S. migration for many decades (Silber Mohamed and Farris Reference Silber Mohamed and Farris2020). Therefore, one possibility is that recent measures of immigration attitudes may magnify gender differences as the collective understanding of who the target population is has changed. Insofar as unaccompanied migrant children or family units represent a change in the “target population” (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993), it could be that women have felt more pressure to adopt empathetic and thus gender-conforming responses to immigrants. The mixture of uniquely punitive policies under the Trump administration like the family separations that occurred during the summer of 2018 combined with more images of migrant children and infants might have exacerbated attitudinal differences across genders.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X23000326.

Competing interest

The author(s) declare none.