INTRODUCTION

The unusually dry conditions in northern England in the summer of 2018 produced a substantial crop of new sites discovered through aerial photography. By chance, the Google Earth satellite image coverage for parts of Yorkshire has been updated with a set of images taken on 1 July 2018, during the drought. Amongst the numerous sites revealed in this imagery – often in areas where crop-marks are rarely visible – is a previously unknown Roman fort (fig. 1).Footnote 1

FIG. 1. Satellite image showing the Roman fort at Thirkleby, taken on 1 July 2018. (Google Earth image)

The site (SE 4718 7728) lies just to the west of the modern A19, on the southern side of the Thirkleby beck at its confluence with the Carr Dike stream, about 6 km south-east of Thirsk. It is situated on level ground at a height of about 32 m above sea level on the southern edge of the flood plain of the beck, which is clearly visible on the aerial images. A further narrow relict stream bed runs beside it to the south-east. These watercourses form part of the system that drains the flank of the North York Moors to the east and flows west into the river Swale just south of Topcliffe. The fort is thus located on the shoulder of land that runs along the foot of the uplands on the eastern side of the Vale of York, slightly above the lower ground of the Vale to the west. Both the modern A19 road and a Roman road (Margary route 80a)Footnote 2 follow this corridor.

THE SITE

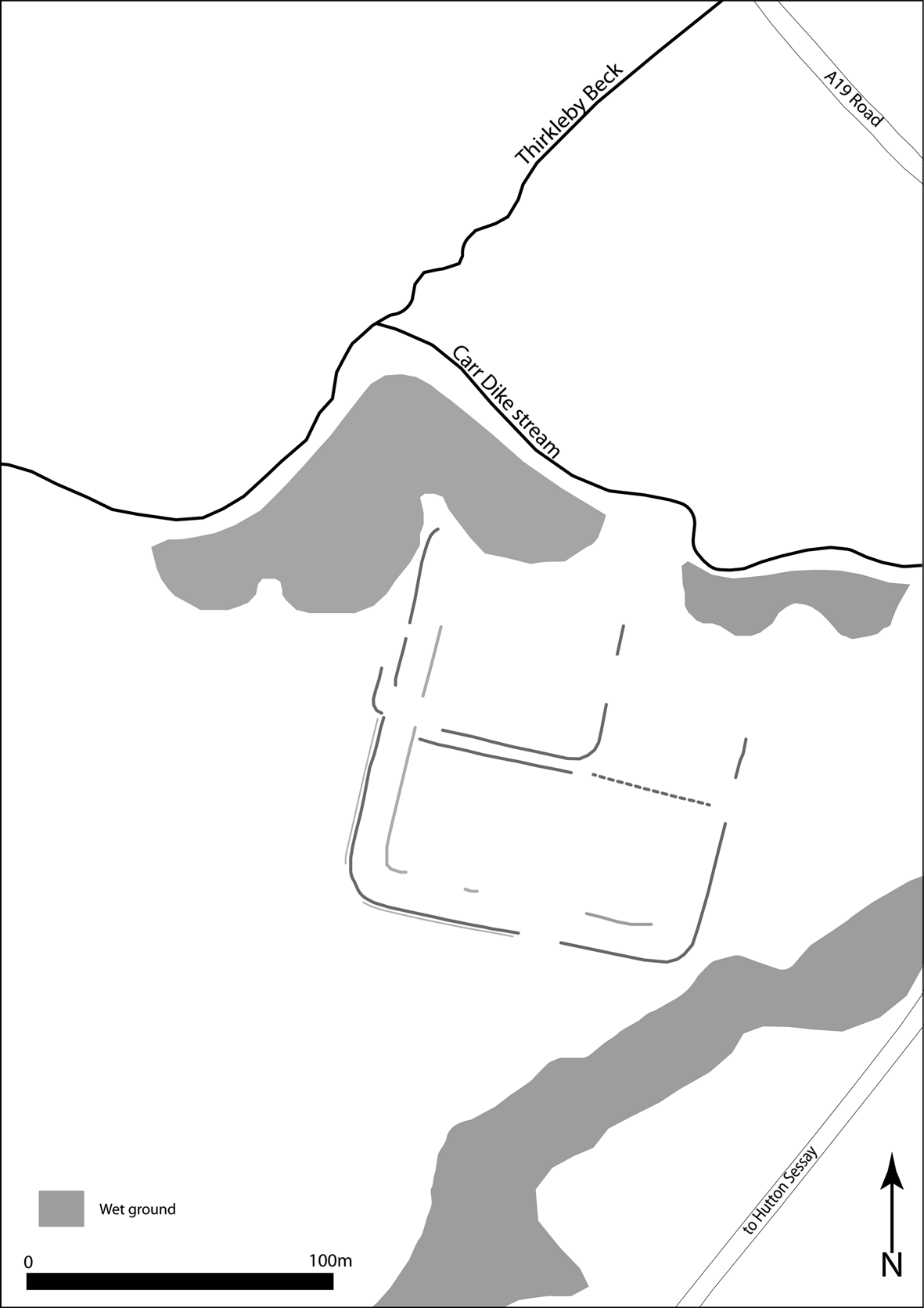

The aerial photo (fig. 1) shows a typical rectangular playing-card shaped outline of a fort with a main ditch, and fainter traces of the outer ditch on the southern and western sides, orientated at 13 degrees east of north. On both these sides, gaps for the gates can be seen. The eastern side of the fort is visible, but less clearly defined. The northern side is missing, presumably eroded by the beck, but the visible turn of its north-western corner allows its position to be estimated. There are faint traces of a gully that presumably defined the inner edge of the defences along their western and southern sides. This outline thus shows an auxiliary fort that measures c. 120 by 120 m (1.44 ha). This is comparable in size to Flavian auxiliary forts like Hayton and Elginhaugh, although smaller than that at Roecliffe.Footnote 3

Internally, there is clear evidence for a pair of east–west ditches that run across to the middle of the fort, just to the south of the axis of the west gate (fig. 2). Here, there is a hint that they turn to run north, on a line just to the east of the axis of the south gate. Further east the approximate line of these ditches is continued towards the east gate by a single line of features: it is not clear whether these represent a ditch cut by plough furrows or a line of large post-pits. At first inspection these all appear to represent internal features within the fort, but their lack of alignment with the gate axes and the apparent continuation of the east–west ditch curving northwards across the west gate and continuing north instead suggest the presence of a second phase with a reduced-sized fort measuring c. 76 m east–west by perhaps c. 60 m north–south (0.45 ha) superimposed on the first (fig. 2). Such a subsequent fort might suggest that it had a longer occupation than some others in the region like Roecliffe and Hayton,Footnote 4 but similar to the early phases at Malton.Footnote 5 We may also note that the aerial photos do not reveal the Roman road, but do show slight evidence of ancient field systems and enclosures in the area to the west and south-west of the fort.

FIG. 2. Plot of the cropmarks showing the Roman fort at Thirkleby. (Drawing by Martin Millett)

THE FINDS

A metal-detecting survey of the site was undertaken by Paul KingFootnote 6 in December 2018 with the finds published on-lineFootnote 7 and reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS). The ‘metallic disk’ shown on the website is the base of a patera, which confirms the military character of the site.Footnote 8 The same illustration shows ten Roman coins, of which four have thus far have been identified and listed by PAS: three first-century issues and one of the mid-fourth century.

The first is a poorly preserved denarius of Vespasian (a.d. 69–79). It is badly corroded, but nonetheless appears, from the published illustrations, to exhibit considerable circulation wear. The second is a sestertius of Vespasian, the obverse sufficiently legible to date it tentatively to a.d. 71–78, but no more accurately than that. It is also substantially corroded, but again appears substantially worn. A third coin is fully identifiable as an as of Domitian, as COS XII (i.e. minted in a.d. 86), and it appears to be only slightly worn. The fourth coin is a reduced siliqua of Julian II (a.d. 360–63) that was minted at Arles in the period after Julian ceased to recognise Constantius II.

Six further Roman coins appear, together with the finds noted above, on the same online illustration of material from the fort area; three of them are perhaps further late first-century dupondii or asses and the remaining three are perhaps late third- or fourth-century bronzes. In addition to this, PAS lists 21 coins from the parish of Thirkleby with Osgodby, comprising the four coins detailed above plus: two denarii, of Hadrian (a.d. 118) and Faustina II (a.d. 145–61); the core of a counterfeit denarius of Severus Alexander (a.d. 222–35); two probable Radiate copies of a.d. 270+; an antoninianus of Carausius (a.d. 286–93); six issues of the House of Constantine (ranging from a.d. 316 to 341); three Fel Temp Reparatio coins of Constantius II, a.d. 353–58 (two regular and one a copy); and an illegible bronze. It is doubtful, however, whether any of these additional 17 coins can be associated directly with the fort, and in the absence of further information they should probably be regarded as stray later finds that relate to other activity, perhaps that indicated on the aerial photographs or associated with the nearby Roman road.

The numismatic dating evidence for the fort is thus at present rather slight, but the Flavian coinage suggests a foundation of that period, perhaps during the latter part of the reign of Vespasian (with Hayton providing a possible parallel). The issue of Domitian provides the most definite evidence; the little-worn nature of the coin implies its deposition in the late 80s or 90s, while the worn natures of the other Flavian coins hint at the possibility of a continuation into the early decades of the second century (paralleling, for example, Stamford Bridge and Malton).

The silver coin of Julian is perhaps a hint of a later, fourth-century, phase of activity, but the current lack of appreciable numbers of late third-century coins appears to preclude any suggestion of continuous occupation throughout the Roman period.

DISCUSSION

As noted by Pete Wilson, until now there have been no fort sites located along the route of the Roman road that runs up the eastern side of the Vale of York (fig. 3).Footnote 9 This road departs from that connecting Brough-on-Humber to York at Barmby Moor, crossing the river Derwent at Stamford Bridge, then following the Vale of York northwards, crossing the river Tees near Middleton St George and continuing north via Sedgefield to join the other main road north at Durham. The only other known Roman fort on this route lies at Stamford Bridge. This is poorly understood, but likely to have been occupied from the Flavian period until c. 120.Footnote 10 This contrasts with the route along the western side of the Vale of York where Flavian forts are known or confirmed at Newton Kyme, Roecliffe and Catterick.Footnote 11 The absence of military installations on the route along the eastern side of the Vale of York arguably implies that it was of less strategic significance than that along its western side.

FIG. 3. Map showing the location of the Thirkleby fort in relation to sites mentioned in the text. (Drawing by Rose Ferraby)

The conventional account of the Roman conquest of this region envisages the Roman army moving progressively north from c. 70/71.Footnote 12 However, this seems increasingly difficult to accept, especially given the clear evidence for Roman activity in the Tees valley at an earlier date. On this basis, it has been suggested that the conquest may have progressed up the valleys from the coast, with the intervening areas only later annexed.Footnote 13 This raises the question of the context for the newly discovered fort at Thirkleby.

In the absence of refined dating evidence, it is worth noting how its geographical location fits into the general pattern of military occupation. In addition to lying on the north–south route on the eastern side of the Vale of York, it is also located just to the north of the east–west route that gives access eastwards into the Vale of Pickering via the Holbeck valley. There was a fort at Malton in the middle of the Vale of Pickering from at least the late first century down to c. 120,Footnote 14 and we now have good evidence for a road linking Aldborough to MaltonFootnote 15 that must presumably have passed very close to the fort at Thirkleby. There is also strong evidence for a major trading settlement at Aldborough from as early as 70, and Isurium was arguably established as the civitas centre of the Brigantes in the later first century.Footnote 16 This might suggest that the route eastwards to Malton was of greater significance than has hitherto been considered. Furthermore, this connects to a longer-distance route across the Pennines via Ilkley and Elslack to Ribchester. The position of the fort at Thirkleby at the intersection of this route with that running up the Vale of York may be the key to its location. It may also be significant that the longer-distance route that links across the Pennines via Ilkley and Elslack to the key Roman centre at Ribchester passed through a region where lead and silver production is attested from as early as 81.Footnote 17 The newly discovered fort at Thirkleby may thus provide a further indication that this trans-Pennine communication route was key in the development of northern Britain in the first century.