Introduction

The scholarly literature on convict labor has been oscillating between economic and political explanations. According to the former, prisoners are put to work chiefly to generate surplus from unfree labor power. The state benefits from convict labor to decrease the administrative costs and to make profit, or to provide cheap labor to private enterprises. In either case, use of forced labor in prisons allows the sovereign to get rid of all privileges of free workers (bargaining power, political organizations, historically acquired rights). The power-oriented political explanations, however, oppose the profitability of convict labor and emphasize instead the organized violence of the state, the governmental strategies, and the creation of social control mechanisms. Disciplining the society may have economic ends (i.e., the repression of the working-class), but the immediate outcome of prison labor is not profit; in most cases, it is rather a financial burden to the state.Footnote 2

The labor-based prisons in Turkey from 1936 to 1953, however, evade both economic and political explanations. Even though these special prisons claimed profits every year, the numbers were far from being high enough to compensate the invisible organizational costs. Moreover, the profits made by the prisons were entirely distributed to the prison staff as bonuses; thus, there was no creation of surplus in the economic realm. On the other hand, the state of the Republic of Turkey never even intended to use prisons as an instrument for social control, at least until the 1950s when the penal system turned from employing the common criminals to incarcerating the political criminals. It is true that a certain moral character of the honorable and docile prisoner-worker was circulated in the national media, but this image was not limited to prisons and was dreamed of for all citizens (similar to the image of Stakhanov in Soviet Union). As an alternative explanation, this article proposes an institutional analysis of the labor-based prisons in Turkey. I will argue that the target of the convict labor system was neither the convicts nor the working class but the state department itself.Footnote 3 It was less a government that resorted to social control techniques and profit-maximizing measures than a state department that transformed (or mistook) itself to (as) a capitalist corporation with bureaucratic management.

Convict labor in Turkey has been underresearched in academic scholarship. Prisoner-workers have been mentioned only in passing in studies of labor history or penal history in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey.Footnote 4 The single academic study on prisoner labor is on prison workshops in the 2000s, while the only nonacademic work is Erol Çatma's book on prisoner-workers in the Zonguldak Coal Basin from the 1930s to the 1950s.Footnote 5 Additionally, the special labor-based prisons have never been mentioned in the literature, even though they covered one-third of the entire prisoner population in the late 1940s. As a result, convict labor has either been normalized as an ahistoric component of all prisons or been taken as an extreme case of forced labor in the mines. By examining archival materials in a systematic fashion, this article demonstrates that the labor-based prisons were first and foremost bureaucratic institutions, exceptional spaces which allowed the technocratic class to experiment with the ideal of the rational corporation, turning the prisons into internal colonial laboratories for modern rational capitalism, without being interrupted by real market forces.Footnote 6 In what follows, I will first tell the story of these special prisons and their legal status; second, via comparisons with other unfree laborers and nonworking prisoners, I will demonsrate the peculiar structural violence created by the prison administration; last, I will analyze in detail the remuneration system for the prison staff to delineate the corporate character of the labor-based prisons.

The Creation of the Labor-based Prisons and the New Penal System

The labor-based prisons (1936–1953) were the product of a special period in which capital faced serious shortage of steady labor force to fulfill the plans of industrial growth. These prisons were born when the bourgeoisie-state alliance started to intervene intensely in the labor market, and they died when an alternative reserve army was already created in the free labor world. The first half of the 1930s was characterized by the consolidation of state authority in the young nation-state thanks to the nascent collaboration between the military, the bureaucracy, and businessmen. On the one hand, the first five-year industrial plan (1934) and the establishment of two biggest state-run enterprises (Sümerbank in 1933 and Etibank in 1935) initiated the state-led capital accumulation in heavy industry. On the other hand, the private sector was regulated according to the needs of the bourgeoisie. The outcome of this process was the Labor Code of 1936, which stipulated a corporatist symbiosis among the state, bourgeoisie, and the workers, since the latter was deprived of any class-based rights.Footnote 7

Less known to labor historians is that the year 1936 also witnessed the creation of a brand new penal system in Turkey. The Penal Code of 1926 was comprehensively amended to the extent that the main framework of the 1936 version was to survive until the 2000s. In September 1936, Minister of Justice Şükrü Saraçoğlu (1933–1938) announced the new prison structure in parliament.Footnote 8 He stressed the burden of prisoners on the state budget and heralded the adoption of the most efficient and modern solution: making the convicts level their costs by working. The modern prisons in Europe had been visited by the inspectors of the Ministry; the available systems of punishment of the modern world had been evaluated.Footnote 9 Accordingly, “système progressif” (tedricî serbestî sistemi) or “stage system” (devre sistemi) was adopted into Turkey's penal structure.Footnote 10 In theory, the new progressive system was composed of four stages, starting with solitary confinement in cells. At each stage, the prisoner would acquire some privileges like transferring from the cell to the wards, working outside the prison, or the right to probation. In the last two stages, each working day would count four-third and two days—respectively—of the nominal sentence period. Each criminal was supposed to go through all four stages in the course of their imprisonment.Footnote 11

In his speech, Saraçoğlu also officially announced the founding of the first labor-based prison on İmralı Island in Marmara Sea, the news of which had been expected for a year. This island of ten square kilometers had been uninhabited ever since its Greek inhabitants were forced to move to Greece during the population exchange of 1923–1924.Footnote 12 In 1933, the ruling party (RPP) mentioned among its future plans the idea of creating an “agricultural colony” on İmralı Island.Footnote 13 On July 29, 1935, Cumhuriyet—the semi-official newspaper—publicized that the government was seriously considering building a new prison on İmralı to make prisoners work on the land.Footnote 14 By January 1936, fifty prisoners had been sent to the island, accompanied by an expert on agriculture, to start working in agriculture, fishing, and building the dormitories.Footnote 15 The initial progress was quite fast; by the time Saraçoğlu made his speech in September, the population of the island reached two hundred, and another agricultural prison was founded in Edirne.Footnote 16

The following decade in the life of the labor-based prisons, and particularly of the İmralı Colony, was an undisputable success story. The island's convict-worker population reached four hundred in 1937, six hundred in 1939, and nine hundred in 1941;Footnote 17 hence, it became a real “colonie penitentiaire.”Footnote 18 At the same time, in addition to the newly founded agricultural prisons in İmralı, Edirne, and Dalaman, the convict labor system was extended to the state-run factories and mining enterprises where the inmates were to work along with free workers. As a result, by the end of the 1940s, the prisoners were employed in the mines of Zonguldak, Tunçbilek, Keçiborlu, Soma, Maden, and Değirmisaz, in the prisonhouses of Eskişehir, Malatya, Isparta, and Ankara, in the factories of Karabük (steel) and Kayseri (textile—for women prisoners), and in the aforementioned three agricultural colonies. In 1949, approximately one-third of the entire convict population (seventeen thousand) was in the so-called new prisons or modern prisons (Asrî Cezaevi) or officially the labor-based prisons, sixteen in total.Footnote 19

The Dual Prison System—Part I: Structural Violence

In its entire lifetime (from 1936 to the early 1950s), the new penal system worked on the basis of a duality of “old” and “new” prisons. The four-stage progressive system was actually never implemented. In practice, there were only two stages: staying in the old prisons (all non-labor-based prisons) and working in the new labor-based prisons.Footnote 20 The original stage system was allegedly abandoned due to financial inabilities (to construct individual cells for each inmate was too expensive for a small economy).Footnote 21 However, I argue that the emerging duality was in perfect accordance with the broader bureaucratic project in which the prisoner world was divided into two spheres based not on (temporal) stages but on (functional) compartmentalization. The old prisons served as a deterrent in order to tame the working prisoners in the new labor-based prisons, whereas the latter served as an ideal to reach for those in the old prisons.

It was not compulsory to go to the modern labor-based prisons; in fact, it was a privilege.Footnote 22 The convicts of petty crimes, the recidivists, and the political criminals were excluded from the new prisons. For the rest, an age-limit (a maximum of thirty to forty years) and a restriction on the minimum remaining prison term (between one and four years) applied. Moreover, the forms filled out by prison administrators and physicians in each prison would indicate whether prisoners had shown “good conduct.”Footnote 23 Once transferred to the new prison, each working day counted two days of imprisonment, in other words, the remaining sentence was reduced by half. In addition, the prisoner-workers earned daily wages, and they did not stay in an actual prison building but in dormitories. If a prisoner-worker broke the rules (which was presented as “betrayal”),Footnote 24 he was sent back to the old prison, and all of his earned days and money were appropriated.Footnote 25

In consequence, the prisoner-workers and the reserve army of prisoners lived immensely different lives in two dissimilar institutional spaces. The ruinous situation of the old prisons was the recurrent subject of complaint in the reports of the regional congresses in 1933.Footnote 26 In 1940, 1945, and 1946 the deputies made visits to their electoral districts and wrote reports to the Ministry of Justice regarding the unhygienic conditions and primitive environment in the prison houses.Footnote 27 All old prisons were suffering from a lack of sanitary toilets, of sunlight, of modern buildings, and of sufficient space (in one case, six hundred to eight hundred convicts lived in an old church that had been converted into a prison). Among others, the typhus epidemic of 1943 hit the prisons so seriously that the Ministry sent steam cabinets to sanitize the clothes of the inmates.Footnote 28

Life in the labor-based prisons, however, was represented in total contrast to the conditions of the old prisons. The İmralı Island Prison, in particular was turned into a dream-world for the new penal regime. Over the years, many ministers of justice (once even the president) made ceremonial visits to the island, accompanied by journalists and politicians; many columnists publicized the experiment in the national papers.Footnote 29 In the 1940s, hundreds of law students made research trips to the island and prepared reports and monographs. In one instance, Professor Sulhi Dönmezer stayed for ten days on the island in order to investigate its autarchic economy.Footnote 30 Even high school students and teachers were brought to this symbol of modern life.Footnote 31 Visitors were amazed by the freedom enjoyed by the prisoners in this setting without handcuffs or prison bars. Economist and bureaucrat Vedat Nedim Tör found here the essence of an ideal life and even wrote a play entitled The Men of İmralı.Footnote 32 Cambridge Professor Clive Parry, after his visit, published an article on İmralı and wrote: “I have no hesitation in saying that the Imrali penal settlement is the finest thing of its kind which I have seen in any country.”Footnote 33

There is no evidence to suggest that these representations of the ideal docile convict-worker were simply ideological fabrications. In fact, albeit probably exaggerated, this relatively better-off life in the labor-based prisons was a direct outcome of the dual structure of the prison system, which divided the prisoner pool into a reserve army (in the old prisons) and a labor aristocracy (in the new ones). There were lower levels of brutality in the new prisons, not necessarily because of humane ideals, but because of the threat of being sent back to the old prison in which the reduction of sentence by half would cancelled. In that sense, there was no “job security.” Contrary to generic prison regulations (for example, of the Ottoman period), which on paper forced all prisoners to work (without any success, ever), this dual system creatively established a miserable nonworking space and a privileged working space so that the structure itself enforced voluntary laboring. Hence, “being fired” was a real threat in the new prisons. On İmralı Island, for instance, 443 prisoners (out of 4,889) were sent back to the old prisons between 1935 and 1947 for various disciplinary reasons, and among the 19 escape attempts, 16 were captured and sent to the old prisons with heavier sentences while the other three died.Footnote 34

The effect of the structural violence created by the dual prison system was also observed in the Zonguldak coal mines.Footnote 35 The case of the mines is particularly illuminating because it gives an opportunity to compare the situation of the prisoner-workers to other forced-laborers who were employed in the coal basin under the Compulsory Labor Regime enforced during World War Two. The Compulsory Labor Regime was the response of the state to the so-called “labor problem,” which had prevailed since the early 1930s. In a nutshell, the labor problem denoted the lack of a steady labor force (not to the lack of a labor force).Footnote 36 Many male villagers used to work in the mines and in other factories for a short time in order to earn some cash; however, since they kept being connected to their village economy and household or had opportunity to change their job, they did not compose a full-fledged working class, an enduring labor force attached to one single factory.Footnote 37 Thus, the labor turnover rates were high: It was 68.3 percent in the Karabük iron factory and 24.7 percent in Ergani copper mines in 1941. In the Ereğli coal mines basin, a worker spent fourteen days per month on average in the mines in 1936. Absenteeism prevailed, too: For example, in Guleman East Chromes, in July of 1943, only 116 of 402 workers showed up every day (30 days).Footnote 38

Accordingly, the new National Protection Law (1940) allowed the government to take extraeconomic measures over workers during the extraordinary war years. The relevant articles of the law were immediately implemented in February 1940 with a decree that constituted compulsory labor regime at the Ereğli coal basin, and the sanctions were toughened in 1942 with another decree.Footnote 39 Numbers demonstrate the inordinate system: In 1948, of 27,000 workers in the basin, only 5,000 (18 percent) were free workers; the others were conscribed from men living in the Zonguldak region. Of these compulsory workers, 5,000 were steady workers, and the remaining 15,000 were working alternately for one and a half months. In addition, there were 1,000 to 1,500 soldiers and 1,261 prisoners working in the mines.Footnote 40 Apart from mines, the forced labor regime broadened to include construction of public works (roads, bridges, railroads).Footnote 41 In sum, what war mobilization in 1940 aimed to accomplish was to secure a fixed worker supply for the growing state-run enterprises.

Even though both compulsory work and prisoners’ work are forms of unfree labor, the structures of force and legitimacy were in complete contrast. Peasants under the yoke of compulsory labor regime tried their best to frustrate the implementers.Footnote 42 Every one out of ten forced workers succeeded in running away from Ereğli coal basin (9.7 percent in 1942 and 10.7 percent in 1943).Footnote 43 Villagers made use of the infrastructural incapacity of the state to escape this “collective conviction-psycho”Footnote 44 in the mines. Compulsory labor regime, seen as drudgery, had no legitimacy at all, and the forced workers had every reason to sabotage the system. This was, however, not true for prisoner-workers. Although the official declaration that the prisoner-workers in Ereğli/Zonguldak mines were working “like sheep”Footnote 45 should not be accepted without reservation, substantial evidence exists regarding the submissive attitudes of the convicts. In 1939, the official inspectors reported that prisoners and free workers work together without having any coordination problem. It was testified in 1994 by one of the workers, Sabri Eyüp Demir, that the prisoners’ working conditions had been “very good; they had no difference from us.” The prisoners were, it was reported, not only hard-working but even more productive than the free workers.Footnote 46 The 1949 observations of Gerhard Kessler, professor of sociology and social policy, supported the reports:

Because every day spent in the pits is regarded as two days of confinement and because their life in mine basin is freer than that in the prison, they are ready to tolerate everything in order to spend most of their sentence here; they constitute the most obedient part of the work force.Footnote 47

Hence, desertion was considerably rare among the prisoners in comparison to the compulsory labor force. Demir, the above-mentioned worker, said, “I didn't hear [any escape affairs]. Their concern was to finish the sentence, and go away.”Footnote 48 Erol Çatma, historian of the coal basin, concluded that the convict workers were in general quite content, and they attempted to run away only when they were afraid of being sent back to the old prisons. The common reason of sending them back was sickness, which turned the convict into a useless burden for the enterprise.Footnote 49 Of significance is the fact that while being hospitalized meant for forced workers at least a temporary escape from the mines, it was a disaster for the convict workers. For them, the alternative to the mines was not being sent back to their village, but to the old prisons. Nevertheless, epidemics such as syphilis, malaria, and typhus were widely seen in the basin due to the impact of war and the absence of public health measures.Footnote 50 Thus, the attempts of hospitalized prisoners to escape turned into a serious problem to be related by the public prosecutor of Zonguldak to the minister of economics.Footnote 51 The penal system based on labor caused “the abandonment of unproductive prisoners to the margins of penitentiary life.”Footnote 52

In conclusion, the dual-prison system had a peculiar structural effect on convict workers’ attitude in the workplace. Both in the agricultural prisons like İmralı Island and in the mining zones of mixed labor like the Zonguldak coal basin, prisoners worked under threat of being “fired”—that is, of being sent to miserable conditions for a reduplicated period of time. It was not only in the propaganda of the national press that the degree of physical violence in the new prisons was considerably low; similar to the rules of free labor market, without any workers’ rights, oppression was shifted from workplace to the general labor structure. In the compulsory labor regime, however, violence was extensively observed, as “firing” was not an option. In other words, forced workers had nothing to lose for being subversive, but the prisoner-workers had something to lose, which made them work voluntarily even more than the free workers. While debates in the literature previously focused on whether (and how) unfree forms of labor contributed to or impeded the development of capitalism,Footnote 53 scholars have now turned away from a rigid dichotomy between free and unfree laborFootnote 54 and have instead proposed “a multiplicity of forms of exploitation.”Footnote 55 The dual structure of the penal regime in Turkey in the 1930s and 1940s complicates the free/unfree dichotomy by highlighting a particular form of unfree labor, which differed not only from the compulsory labor regime in Turkey, but also from other convict labor cases like chain gangs and prison industrial complexes.

The Dual Prison System—Part II: Bureaucratic Corporation

The dual structure of the penal system in Turkey did not simply consist of new regulations and orders; prisoners’ lives were not governed by abstract principles or by stamped papers only. In fact, the division of the convict labor pool into a reserve army and a privileged unfree working class corresponded to a crucial (albeit less visible) division at the institutional level, too. In this section, I will examine the institutional structure of the prison administration and the corporate economy of the prison staff. As Alex Lichtenstein remarked only a few years ago, studies of convict labor have paid less attention to “the history of the labor of the keepers rather than the kept.”Footnote 56 By analyzing the prison system at both levels, this article aims to bring together the convicts’ and the staff's institutional experiences. In the following paragraphs, original archival data will be used to uncover the remuneration system for the prison staff. I argue that the labor-based prisons were experimental laboratories which were used to create a rational capitalist corporation under auspices of the state department.

In 1936, as seen above, the minister of justice announced the new penal system as well as the founding of the first labor-based prison on İmralı Island. Nevertheless, the new system did not have any institutional basis (i.e., the new prisons were still governed together with the old ones) until two years later.Footnote 57 In 1938, under code no. 3500, a new bureaucratic body entitled the General Directorate of Prison Houses (Cezaevleri Umum Müdürlüğü) was established. Similar bodies had existed before under different names (for instance in the Ottoman period); the real contribution of the 1938 law was the new dualist bureaucratic structure. The directorate was divided in two: The “Second Division” was to be responsible for hundreds of prison houses except for the new labor-based ones, whereas the “First Division” managed the labor-based prisons only (these numbered only a few at the time, and at most sixteen prisons in later years). Moreover, the director of the First Division was to serve at the same time as the vice director of the general directorate.Footnote 58 In other words, from then on, the labor-based prisons meant not only a privilege for the prisoners, but also an upward movement in the administrative hierarchy for the directors and the rank-and-file staff.

The 1938 Law, however, brought about much more than a simple division of labor between two state departments. Careful examination reveals that the First Division was not only separated and elevated from the Second Division, but it was also furnished with two unprecedented legal and economic privileges. First, Article 6 of the Law assigned legal personality to the First Division (but not to the Second Division). Second, the labor-based prisons were ordered to finance the maintenance of the prisons (food, utilities, constructions, and wages) from their circulating capital, which was to consist of allocations from the state budget and profits made on the sales of the prison products.Footnote 59 As a result, a legally and economically autonomous body was created under the state department to govern the convict labor business. I argue that this new body, called the First Division, functioned as a bureaucratic corporation.

According to Max Weber, the legal concept of “modern corporation” was one of the prerequisites for the development of modern rational capitalism. The distinctive feature of modern corporations was their internal functioning as modern bureaucratic administrations. Based on his observations of the state system in the United States, Weber concluded that the idea of a fundamental difference between private business relations in the market and state's economic activities was an artificial European concept. Instead, he emphasized the similarities between the two, and singled out the modern bureaucratic administration as the fundamental mechanism of rational capitalism, both in private enterprises and in state departments.Footnote 60 Accordingly, Weber identified three conditions a modern corporation has to meet: First and foremost, it must have legal personality (“the complete separation of the legal spheres of the members from the constituted legal sphere of the organization”).Footnote 61 However, this was not a sufficient condition because in his categorization “endowments” and “institutions” (like schools, state hospitals, and prisons) had legal personality, too.Footnote 62 Second, corporations must have their own capital, namely the circulating capital in the case of labor-based prisons. And third, which is most crucial here, modern corporations must distribute capital shares to their members.Footnote 63 In the following paragraphs, I will show that the third condition was also met by the labor-based prisons in Turkey. Using yearly budgets and the remuneration tables, I conclude that the bonuses given to the prison staff from the circulating capital were systematized to the extent that a regular capital distribution system emerged.

Scholars working on unfree labor have recently called attention to the use of incentives in forced-labor regimes. Especially during periods of labor scarcity, even the well-known brutal penal regimes like the Soviet camps fell back on rewards in order to keep production levels high. The Main Administration of Soviet Prison Camps (Gulag) not only introduced the same compensation system as in Turkey (one day working for two days of prison term) but also implemented a system of “monetary rewards” or “bonus remunerations,”Footnote 64 bringing about “an array of punishment and reward.”Footnote 65 In the nineteenth century U.S. context, Goldsmith has pointed out the extra payments, privileges and compensations used to encourage the prisoners.Footnote 66 And, Salvatore, writing on the prison reforms and working classes in nineteenth century Brazil, asserted that in periods of labor scarcity “coercion always appeared to be accompanied by various types of incentive” and “contractualism [and market culture] tends to pervade relations of power, even those previously based upon coercion.”Footnote 67 In Turkey, too, prisoner-workers were given incentives in different ways. Reducing the prison term by half and receiving wages for work were, as already mentioned, the most important privileges. In addition, the premium by-laws promised to convicts extra wages for overtime work.Footnote 68

Nevertheless, in their emphasis on incentives in the forced-labor regimes, scholars have not paid much attention to the incentives given to the prison staff. As early as 1936, as soon as production started in the new prisons, the Ministry of Justice determined to remunerate those who had made a substantial contribution in founding the new system practically. The Republican Archives of Turkey include invaluable documents that display the lists of names and rewards for each labor-based prison and for each position in a prison for various years. These charts allow us to go beyond the prescriptions of the regulations and by-laws and to reach an understanding of how the system worked on the ground. In 1937, right before the promulgation of the above-mentioned code, the director and three employees of Ankara Printing Prison were remunerated 125 and 100 liras, respectively, for their overtime work in the preceding year, during which the prison had made 3,000 liras in profit.Footnote 69 The following year, beside the staff, two inmates (the workshop chief and the stockroom officer) earned 150 liras, respectively, in bonuses whereas the director's reward was increased to 200 liras. The public prosecutor of Ankara, too, was granted 250 liras for his efforts related to the Printing Prison, the circulating capital of which was the monetary source of the bonuses.Footnote 70

In order to comprehend what these amounts meant, we need to take the real wages into consideration. In 1938, the monthly salaries of the general director of the prison houses and of the directors of the first and second divisions were one hundred, seventy-five, and fifty liras, respectively (another proof of the privileged position of the First Division).Footnote 71 The general director's salary remained one hundred liras also in the following years (at least until 1944).Footnote 72 Having stated that, Sakıp Güran, the vice director of the prison houses and the director of the First Division, was given 200 liras in 1941 and 250 liras in 1942 for his extra efforts in the improvement of the labor-based prisons.Footnote 73 These numbers indicate that the incentives in question were significant contributions (around twenty-five percent of the annual salary) to the income of administrators in the First Division. On a separate note, these bonuses were distributed from the circulating capital not of a specific prison, but of the first division. In other words, the structure of the First Division consisted of one headquarters with its own capital and a group of individual departments (each labor-based prison) with their own circulating capitals, each of which was responsible for the incentives in its own jurisprudence.

The system worked also for the rank-and-file members of the bureaucracy. For example, in İmralı Agricultural Prison, Ahmed and Ali, both having twenty liras primary salary, earned an extra two to three liras in 1937.Footnote 74 Perhaps the intermediaries, however, deserved more credit, as any profit-making organization needed network managers to sell the products. For example, the Isparta New Prison was specialized in carpet weaving. Due to the high cost of using an outside agent to market the carpets, the administration decided that Sadık Bener, the stockroom officer of the Ministry of Justice, would take on the task of marketing. The carpets were sent to the Ministry in the capital city and were sold there by Bener to costumers, either by cash payment or by installments. In return for his labor, 200 liras was allocated to Bener from the circulating capital of Isparta New Prison in 1941.Footnote 75 The practice continued in the following years. In 1945, the amount of bonus money was increased to 300 liras. In 1950, another employee, İsmail Uzgören, replaced Bener, but the intermediary position of the officer in the Ministry did not change. Uzgören received bonuses until 1953, the year he gained 400 liras for the sales of carpets from Isparta and Sivas Prisons.Footnote 76

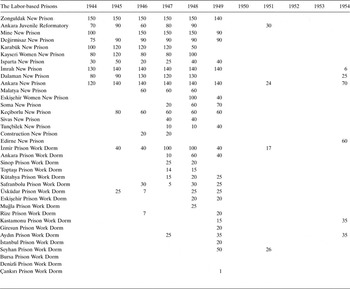

The reader may have noticed that the monetary rewards so far evaluated were only one-time payments in the end of each budget year. Thus, they were incentives but not capital shares as expected in a corporation. In 1943 to 1944, though, a seemingly slight change in the managerial structure of the labor-based prisons transformed the reward system crucially: It allowed that the monetary contributions would be distributed as additional monthly wages. According to the 1943 amendment to the Code No. 3500 of 1938, those prison staff who worked overtime or stayed in the prison over night were to be paid a monthly share from the profit of the prison in the preceding year.Footnote 77 In 1944, this time an ordinance from the government announced that the representatives, officers, and employees in prisons with circulating capital (namely the labor-based prisons under the First Division) would be paid an extra monthly wage if they spend “some nights” in the prison on business. The amounts of the payments were to be registered to the forms attached to the ordinance.Footnote 78 In practice, the ambiguous wording, “some nights”, was used on behalf of a comprehensive system in which every employee of each prison got an additional monthly wage in proportion to his rank and the profit of the prison where he worked. The wage and budget tables of each labor-based prison between 1943 to 1944 and 1952 to 1954, compiled from the yearly financial reports of the prisons, allow us to see the real economy of the prison camps (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table One The Net Profits of the Labor-based Prisons

*PMRA File: 21–76. **PMRA File: 21–44. ***Computer calculation.

Table Two The Extra Monthly Wage of the Directors of the Labor-based Prisons*

*Source: PMRA File: 21–44 and 21–76.

According to these registries, the rank of the staff was decisive in the determination of the extra salaries. More importantly, the extra wage was no longer given to individuals but was distributed according to their position. At the İmralı Agricultural Colony, for instance, thirty people/positions on the list of 1944 covered the entire prison staff from the bottom up: the director, guards and head guards, secretaries, chiefs of carpentry, chiefs of construction work, chiefs of fishing, and chiefs of shoe making, the administrative officers, captains, doctors, and the other health employees. The highest extra wage was the director's (130 liras), and the lowest was the guards’ (15 liras). The total amount of the extra payments was 13,620 liras for the year of 1944 (approximately 1,150 liras per month). This amount was paid from the profits of the establishment in the preceding year, which was 151,743 liras and 53 piaster in total for 1943 (approximately 9 percent).Footnote 79 The proportion of the extra payments to the total profit varied; for example, only 4,200 liras from 80,732 liras were distributed in Karabük Iron-Steel Factory/Prison (approximately 5 percent), while at the Kayseri Textile Factory/Prison for Women 3,300 liras were expended of 13,355 liras (approximately 25 percent).

In 1945, similar forms were received from prisons with circulating capital at the request of the government. The only difference was the addition of the Malatya and Keçiborlu mines as new prisons. Moreover, the İzmir and Üsküdar Prison work dorms were added to the list.Footnote 80 In 1946, the work dorms of Rize and Safranbolu Prisons and the construction of the new prison appeared on the charts in relation to the remunerations given to the staff of the prisons with circulating capital.Footnote 81 It should be evident to the reader that these are not newly-founded prison buildings nor hitherto nonexisting workshops. Except for the agricultural ones, the labor-based prisons in Turkey were not specialized facilities designed exclusively to run convict labor in profit-making activities. They were rather conceptual structures defined by the legal functions they imposed on prison management. The fact that between 1945 and 1954 additional prisons were placedon the list of new prisons does not signify an increase in the use of convict labor or in the number of work dorms. It rather tells us how the administrative jurisprudence of the First Division grew by endowing the working places in or out of the prisons with circulating capital, legal personality, and profit shares to the staff. The concept of convict labor signified not only the exploitation of prisoners’ labor but also—perhaps even more than that—the transformation of ordinary state departments to bureaucratic-rational capitalist corporations. The story of convict labor in the Republic of Turkey is in fact the story of the First Division: its foundation, its proliferation and diffusion, and its demise.

The best way to trace the colonizing attempt of the First Division and the resistance it encountered is to look at the conflict between the Ministries of Justice and Finance. To earn the right to extra monthly payments, the Ministry of Finance remarked in 1945 that the prison staff had to stay late all days of the month (work overtime every day); the nights spent outside of the prison should be deducted from the monetary reward. The Ministry of Justice criticized this interpretation on the ground that the labor-based prisons should be promoted, and such restrictions were needless and undermined the purpose of establishing these new prisons. The amendment (1943) had been active only for two years, and the profits of the new prisons had already increased from 202,823 liras in 1942 to 531,527 liras in 1944. Moreover, the Ministry of Justice continued, any deduction based on daily calculation did not make sense because in essence, a monthly wage system was implemented.Footnote 82 The reaction of the Ministry of Finance reflected the logic of the traditional system of state employment where the employees had a stable salary, and earning remunerations or other kinds of intensives were extraordinary and particularistic by definition. However, for the First Division, the so-called extra payments were actual profit shares that were meant to integrate the employee into the profit-making business of the department (prison).

In 1946 and 1947, the Ministry of Finance raised similar criticisms and interrogated the increase in the extra wages of some directors; the numbers were considered unnecessarily high. The minister of justice defended the system, again, by referring to the importance of the incentive policy and the promising profits of the prisons.Footnote 83 Insistently, the Ministry of Finance sent in similar reports in 1949, but the winner was again the Ministry of Justice.Footnote 84 Only in 1951 did the Ministry of Justice concede its privileges and accept that the employees should stay all nights of a month in prison in order to be assigned a premium based on a monthly wage.Footnote 85 In 1954, the Ministry repeated the same obligation in its report to the Prime Ministry.Footnote 86 The charts of extra payments also testify that the unique system of labor-based prisons vanished silently in the beginning of the 1950s.

Conclusion

By the end of the 1940s, the problem for capital was no longer the shortage of labor. The topic of the day was immigration to the cities and the new jobless masses. Employing prisoners was becoming an annoying idea—almost an insult to the thousands who lived in the streets in miserable conditions. These concerns began to be expressed by the representatives in the parliament in 1949. The audience was told that many juvenile criminals were planning to kill someone when they reach the age of eighteen just in order to go to İmralı to live a “prosperous life.”Footnote 87 In 1950, the comfortable life on the island was pointed out again, and it was argued that these prisons did not have a deterrent function anymore.Footnote 88 In 1951, an MP claimed that the reduction of a sentence by half encouraged even innocent people to commit a crime.Footnote 89 The same concern was repeated in 1952: The penal system and the new prisons functioned as an abetment to crime.Footnote 90 İmralı Island was once again the symbol of the special system, but this time it was represented as a place of luxury and was used for attacking the notion of the employment of prisoners. As a result, the Penal Law was significantly amended in 1953. Among other new harsh measures (at one time, the reintroduction of whipping under consideration), the new law silently nullified the incentive of sentence reduction in the labor-based prisons. Moreover, the share of the first stage in the old prisons was lengthened.Footnote 91 In other words, the peculiar convict labor system was abolished in 1953 though it would remain in name until 1960.

The labor-based prisons in Turkey were products of a special conjuncture and a peculiar mindset. They were first and foremost institutional—rather than economic or political—experiments of the Republican state elite. The managers of the First Division and of the most important labor-based prisons were intellectuals of their age; they believed in state capitalism, in middle-class ideals, and in the evils of market economy. They did not see any paradox in the combination of a highly bureaucratic state apparatus and the development of capitalism. In fact, they tried to realize the dream of capitalism by turning the state itself into a corporation that was exempt from all the idiosyncrasies of the free market. The director of the İmralı Agricultural Prison from 1941 to 1942 was Esat Adil Müstecaplıoğlu, who would found the Socialist Party of Turkey in 1946, would be arrested and put on trial after the party was banned and dissolved, would found it again in 1950, only to be arrested and put on trial once again.Footnote 92 The most influential director of İmralı Prison and one of the ideologues of the labor-based prisons, İbrahim Saffet Omay, was not a socialist but a furious opponent of the free market. In 1991, he published a harsh public letter against the contemporary minister of justice who had announced plans to collaborate with the private companies for the use of prisoners’ labor. Omay reminded his readers of the “great” accomplishments on İmralı fifty years ago and critically wrote that the privatization of the prison-work would result in unjust exploitation of the prisoner as cheap labor.Footnote 93

In this article, I showed that the penal system in Turkey was reorganized in 1936–1938 into a dual structure that divided both the prisoners’ pool (Part I) and the prison staff, including the directors, (Part II) into two different institutional universes. For the latter, the First Division was everything that a transnational corporation is for white-collar professionals today: dynamism, modernity, higher salaries, smart business, and even high morals. It was designed as a rational-bureaucratic corporation against the uncontrolled, greedy “business” world. This dream could, of course, be realized only under the monopoly of violence of the state, for which prisons were the best places. On the prisoners’ side, those in the labor-based prisons were privileged. This does not mean that the workers were not exploited: they certainly were, more than those in the old prisons. In fact, the structural violence of the system lies here: The labor-based prisons were totalitarian institutions, not because they made prisoners work by force, nor because they treated them in a violent way, but because they made prisoners choose to go to the new prisons and work there.

To conclude, the government of Turkey did not make a considerable profit from the labor-based prisons from the 1930s to the 1950s, nor did the prisoner-workers later turn into docile members of a stable working force in free life. Convict labor in Republican Turkey cannot be explained from the perspective of labor exploitation; the special labor-based prisons “result[ed] not from profit-seeking but state-crafting,” to use Wacquant's words.Footnote 94 I agree with Wacquant that Weber and Bourdieu, rather than Marx or Fanon, help us understand the phenomenon of convict labor because it is primarily a political institution, rather than a way to exploit the labor of the poor. I would add that the labor history of convict workers in Republican Turkey should take its theoretical inspirations from more recent literatures on neoliberal capitalism and on rank-and-file ideology in modern transnational corporations (rather than from works on chain gangs and prison camps). The workers in the new prisons were privileged in a very precarious way simply because of the existence of the old prisons (and of the reserve army of prisoners there) as a threat.Footnote 95 In this world that lacked unions and any opportunity to organize, it was so easy to fall back to the old prisons; prison-laborers had to work hard, voluntarily, to stay out of them. Thus, I believe, in addition to Weber and Bourdieu, we need to take into account theoreticians of precariousness and affective labor (like, to name only two, Sennett and Berlant) in order to understand the ideologies held among the members of the First Division.