Between the 1880s and the 1970s, more than twenty-six million people emigrated from Italy, moving in significant numbers to either North and South America or to other European countries.Footnote 1 Waves of Italian migration to Australia occurred predominantly in the later period, especially from the 1940s onward, although it received only a small proportion of Italian migration overall—around 390,000 migrants between the 1940s and 1970s.Footnote 2 Yet despite what appears globally to be relatively limited movement from Italy, according to the most recent official estimate, Australia is reported to have the world's highest number of students (339,958) learning Italian, with 283,961 of these students in its primary and secondary schools.Footnote 3 In comparison, in other Anglophone countries such as the United States, to which almost 5.5 million Italians migrated between the 1880s and the 1970s, only 186,894 students are identified as learning Italian across all education sectors, with few elementary, middle, and high schools offering instruction in the language across the country.Footnote 4 In Canada, to which some 650,000 Italians migrated over the same period, there are currently around 37,375 students of Italian.Footnote 5

This comparison is not intended to suggest a direct correlation between Italian migration and the maintenance of the language by subsequent generations. Instead, it points to the complex, multifaceted intersection between language community and maintenance on the one hand, and language education policy and action on the other. Overall, the substantial study of Italian in Australia is a remarkable achievement, given its relatively small population (25.7 million inhabitants in 2021), and the more than seventy languages that school-aged students can study. This success reflects great efforts over decades to foster the study of Italian in Australian schools, as well as the more general societal acceptance of and value assigned to Italian language and culture. What is also striking about the teaching of Italian in Australia is its particular strength in primary schools, alongside a sizable presence in secondary schools. However, history shows that this widespread and normalized presence of Italian in Australian schooling was not always the case. How exactly this process, referred to as “mainstreaming” by Slaughter and Hajek, came to be and what was involved—especially in the primary sector—remains to be fully explored and understood.Footnote 6

While it is established that mainstreaming was, to a large degree, a process driven by Australia's Italian community and its supporters, we must also give consideration to the wider transformation of Australian society and of language education, influenced by the political imperatives of a succession of Federal and state level governments in the later part of the twentieth century.Footnote 7 From the time of initial colonization in 1788 and then again from Australia's federation as a single nation in 1901, the languages, cultures, and peoples of non-English-speaking communities, including First Nations peoples, were long subject to racist linguistic and political ideologies.Footnote 8 Only in more recent decades has significant progress been made in this area—including with respect to language education. The trajectory for the Italian language in Australia and the education system, however, provides a poignant contrast to the past, and an instructive illustration of how an immigrant language came to become one of the most widely studied languages in Australia.

There is an extensive range of historical research documenting the wider forces that have shaped the trajectory of language education (including the teaching of Italian) that inform this paper, including reference to earlier accounts, and analysis of policy texts and policy discourse that reflect the progressive accommodation of ethnic rights and the repositioning of language education, both nationally and at the state level in Australia. Ozolins's work on the politics of language in Australia, covering the period from the Second World War to the early 1990s, for example, provides a detailed documentation of governmental policies related to migration and language, and the role of the multicultural movement in shifting governmental and public perceptions toward “community” languages (i.e., languages with significant communities of speakers resident in Australia).Footnote 9 Several historical reviews have investigated multiculturalism, multicultural education policy, and multicultural education programs in Australia, as well as migrant education across the mid-to-late twentieth century.Footnote 10 This research generally focuses on community languages more broadly, as does research into the expansion of community languages in Australia since mass migration following the Second World War and language policy analysis over the same period of time.Footnote 11 With some important exceptions, there has been less historical analysis focused on the trajectory of Italian language teaching, and while Slaughter and Hajek's work provides a partially historical treatment of the mainstreaming of Italian at the primary and secondary levels of schooling, the data set it relies on is largely quantitative in nature, limiting its scope of analysis to program implementation and student uptake of the language.Footnote 12

A critical aim of this article is to cast a fresh eye on and understand more fully the history of Italian language education in Australian primary schools—particularly from the 1960s to the 1990s—by drawing on previous historical documentation and analysis, as well as on the extensive range of primary data that has been collected by governmental and non-governmental agencies over many decades. The synthesis and reconsideration of these data sources enables us to illustrate in a new light the variables that propelled the language into mainstream education, particularly in the government primary school sector. While we provide information about the Australian context more generally, much of our attention is necessarily on developments specifically in the state of Victoria. It is not only home to Australia's largest Italian community, but it has also always been at the forefront of government- and community- led initiatives in favour of language education in schools.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, developments in Victoria should also be seen as broadly reflective of changes more generally in Australia. As Slaughter and Hajek also point out, the decentralized federal nature of Australia's political structure has a negative impact on the ability of researchers to investigate and report on language education in Australian schools.Footnote 14 Each Australian state and territory is predominantly responsible for its own education system, which is then divided further into three educational jurisdictions—the dominant government (or state) school system, and the smaller Catholic and independent school sectors. At the same time, the Commonwealth government (also called the Federal government), based in the national capital Canberra, has also long played an important role through policy and funding in influencing developments in education across Australia, including with respect to language teaching.Footnote 15 In addition, Victoria is also a recognized leader in Australia with respect to the long-term documentation of language education provision, at least in state schools—a helpful fact which facilitates our research and explains our focus on the government sector.Footnote 16

In the following sections, we first provide a brief overview of Australia's changing demographic landscape since colonization, then explore how the strongly monolingual and monocultural views present in the Australian community and government have changed in response to postwar migration. These sections provide the context for the later parts that delve into language teaching and how the teaching of Italian spread from community language classes for Italo-Australian children in after-hours programs, to what were known as “insertion” classes, offered by community organizations in mainstream schools, and then eventually to the validation and full integration of language education more generally into the broader Victorian primary school curriculum. Our research documents the complexity of language-related policy and planning across times of societal transformation, including the drivers of educational change.

The Positioning of Italian(s) in Contemporary Australian History

Australia has always been a multilingual country, even before British colonization began in 1788. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Australian society consisted of a gathering of diverse cultural and linguistic communities, including Indigenous communities, and New Australians, who came predominantly from Great Britain but also from Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America. Although English has been the dominant language since colonization, there were hundreds of thousands of speakers of Indigenous languages at colonization, and by the 1860s, numerous immigrant languages had also been brought to Australia, with Irish, German, Chinese, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, French, Scandinavian languages, and Italian comprising the largest community languages at the time. The fate of these languages and language communities, however, has been inextricably linked to the policies and prejudices of Australian governments over many decades.Footnote 17

After the formal political federation of Australia in 1901, the building tensions between Germany and Great Britain leading up to the First World War saw Australia identifying even more strongly with the British Empire. In addition to anti-German and more general anti-foreign attitudes, marked racism against Asian migrants led to a strongly negative influence on Australian immigration policy and the banning of entry for non-European migrants through the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, better known as the White Australia policy.Footnote 18 For Indigenous First Nations peoples and their languages, complex and numerous processes that continued after 1901 including dispossession, the removal of Indigenous children from their families, and the explicit repression of languages, among other issues, have led to the loss of intergenerational transmission of many languages as well as, for a large number of those languages, the loss of first-language speakers.Footnote 19

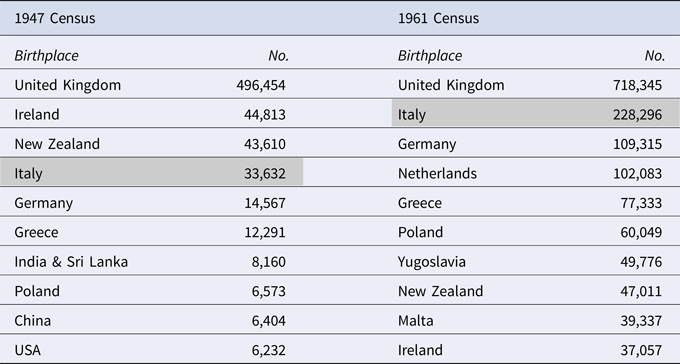

Non-English-speaking migrants also faced barriers linked to racism and discrimination that persisted well into the late twentieth century, and Italians were not immune from the same negative elements that many non-English speakers faced.Footnote 20 However, the journey for the Italian language in Australia has differed considerably from that of many other migrant languages. The language eventually found its way to general acceptance, despite years of political resistance and tensions, with the active support in the first instance of Italian Australians keen to promote inclusion and harmony through the sharing of cultures in a newly developing Australian identity.Footnote 21 The origin of this process can be traced, to a significant degree, to the period after the Second World War, when mass migration encouraged by Australian governments brought large numbers of unskilled migrants from across Europe to Australia for two reasons—to build up secondary industry, and to populate Australia as protection against a possible future invasion from Asia. As a result, the 1940s through the 1960s—and especially the latter two decades—saw the arrival of Italian migrants, in large number by Australian standards, who for many years formed the core of the largest non-English-speaking group in Australia.Footnote 22 To illustrate, Table 1 provides a breakdown of the top ten countries of origin of those born overseas between 1947 and 1961. By 1947, the Italian-born population was already the largest non-English-speaking community in Australia by birthplace, at 4.5 percent of the total overseas-born population. However, by 1961, the numbers of Italian-born had tripled as a proportion of the total overseas-born population (12.8 percent).Footnote 23 These Italian migrants were for the most part from Southern Italy and the Triveneto region in northeast Italy, and once in Australia, most of them converged on the capital cities of different Australian states. Melbourne, as Australia's main industrial center, became the destination for the greatest proportion of Italian migrants.Footnote 24

Table 1. Top 10 countries of birth for overseas born population—according to 1947 and 1961 national census.

Source: “Top 10 countries of birth for the overseas-born population since 1901,” Parliament of Australia. November, 2021, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1819/BornOverseas

Foreign, Migrant, or Other?

While Europeans were encouraged in the postwar period to migrate en masse to Australia, there was also an expectation that new arrivals would forgo their own cultures and languages and assimilate into Australian society as quickly as possible. A shift to English was strongly encouraged and the general view among Australians was that “if ‘they’ could only shed their language and culture and become like ‘us,’ there would be no problem.”Footnote 25 Thus, little support was offered to migrants and their children to maintain their languages, and these assimilationist policies had a detrimental impact, as non-English-speaking migrant families were actively discouraged from using their first language not only in the community but also in their homes.Footnote 26

An important assimilationist element of postwar migration to Australia by Italians and other non-English-speakers was the high uptake of Australian citizenship with its associated voting rights. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, increased community-based political activism against non-English-speaker disadvantage and exclusion, coupled with the sheer number of new arrivals, gave migrant communities unexpected political clout.Footnote 27 As a result, in the 1970s, there was a shift, first toward “a recognition of ‘the migrant problem,’ then of ‘migrant disadvantage’ (and of ‘disadvantage’ more generally) and, finally, the formulation of ‘multiculturalism’ and the beginnings of its implementation in practice.”Footnote 28 Gradually, the Anglocentric insularity and discrimination toward other languages and their speakers began to gradually abate.Footnote 29

Whether it had started with a genuine desire to help migrant communities or, as Foster and Stockley argue, “by a shrewd eye for the ethnic vote,” the ideological shift, which became known as “multiculturalism,” led to many changes in languages services for non-English-speaking migrants and in primary and secondary education.Footnote 30 The notion of multiculturalism encompassed several guiding principles, which Foster and Stockley describe as “equality of access, tolerance of and positive affirmation of ethnic and cultural diversity, mainstream and special ethnic provisions, and the need for wide consultation with and self-help among ethnic groups.”Footnote 31 As the belief that migrants and their children needed to lose their background language to become part of Australian society began to be questioned, community groups and migrant families started to express strong concerns that the younger generation would become unable to communicate with their parents.Footnote 32 These concerns, coupled with migrant communities’ increasing demands for the teaching of their languages in schools, led to community language policy becoming what Alcorso and Cope argue was “one of the most intensely political and contested areas of multicultural education.”Footnote 33

During this shift to multiculturalism in the 1970s and 1980s, Italians continued to represent the largest number of non-English-speaking overseas-born people recorded in the census. The community reached its peak in the 1971 census, with 289,476 people (11.2 percent of the overseas-born population) born in Italy. By 1981 the number of Italian-born had finally begun to decline, falling to 275,883 (9.3 percent). Nevertheless, the sheer number of Italian migrants, coupled with their locally born children, ensured that Italian remained the most widely spoken language, after English, in the Australian community for decades afterward.Footnote 34

From the mid-1970s, national and state policy initiatives started to focus on equity and social justice to support language maintenance, the teaching of migrant or community languages, and specialist English as a Second Language classes, changes that Clyne and Fernandez argue “would have profound effects on language-in-education policy and its delivery.”Footnote 35 This growing focus on migrant children and schooling intersected with significant, broader changes in language education in Australia. Traditionally, the teaching of languages in Australian schools had followed the British model, centering on a small number of languages, typically French, Latin, and German, taught to predominantly monolingual students.Footnote 36 Largely restricted to secondary schools, French and German were positioned as high-prestige languages and offered to students as “foreign languages.” In 1964, for example, the number of Australian secondary students matriculating in languages included French (17,455 students), followed by Latin (3,924), German (2,513), and then, in the distance, Italian (560) and a handful of other languages with very small numbers of enrolled students.Footnote 37

It is worth noting that at this time Italian was already somewhat exceptional, compared with other migrant languages, given its preexisting appeal, at least to parts of Anglo-Australian society, as a language of high culture. It had obtained a relatively early, albeit tentative, foothold in the Victorian secondary school sector in 1935 when Italian was introduced as a matriculation subject, the result of lobbying by the Società Dante Alighieri (see below), sympathetic academics, and other Italophiles.Footnote 38 Its students, well into the 1950s and early 1960s, were overwhelmingly from the Anglo-Australian middle class. The language would slowly, over time, enter some secondary schools in the government and Catholic education sectors and gain very limited traction as a matriculation subject by the 1960s.

It was also at this point in the 1960s that language teaching in schools reached a crisis point in Australia. With the mass expansion of the university sector and language study no longer a university entrance requirement, matriculation enrollment in languages began to plummet. As a result, the foreign language teaching profession was obliged to review the traditional teaching of languages (i.e., French and German) and redefine the curriculum in consideration of “the arrival of quite new forces and ideologies.”Footnote 39 The converging forces of demographic and educational changes provoked a series of shifting tensions in language education. Initially, these arose between French and other languages as the study of French declined. By the end of the 1970s, after persistent lobbying, several more European languages, in addition to Italian, had been integrated as matriculation subjects. Nevertheless, many foreign language teachers remained resistant to a more open approach that would welcome community languages.Footnote 40

Of increasing importance throughout this period was the growing recognition, by the Federal government in particular, of the presence of large numbers of children from a non-English-speaking background moving into schooling. This understanding can be seen in the Federal government report Teaching of Migrant Languages in Schools, which stated that “the social changes resulting from migration and the concentrations of certain language groups in schools have implications for school programs.”Footnote 41 The government recognized that in both primary and secondary schools, Italian had the highest concentration of background students when compared with other languages. Not surprisingly, this was most evident in Victoria compared with other Australian states such as New South Wales (NSW), South Australia (SA), and Western Australia (WA). The arguments in the report were supported by so-called ethnic affairs policies at Federal and state government levels that encouraged the introduction of community languages into primary and secondary schools, and support of teacher education to develop a qualified workforce to teach the languages. The road toward the greater integration of community languages into schools took many years and also involved a concerted effort on the part of academics, community members, and organizations, as well as other interested parties.Footnote 42 This part of the journey begins with an exploration of ethnic schools (now usually referred to as community language schools) as stepping-stones toward eventual mainstreaming.

Ethnic / Community Language Schools

From as far back as 1857, some migrant communities had organized teaching in one form or another in their own languages, often alongside English. However, by the First World War the government, through the White Australia policy, had largely eliminated these efforts. They began to re-emerge in the 1960s and 1970s in the renewed form of ethnic schools—that is, after-hours language programs organized by migrant communities to support language maintenance.Footnote 43

Such schools were particularly prominent in Victoria and NSW, the two most populous states. By 1980 these two states were reported to have the highest enrollments and, respectively, Footnote held 46 percent and 29 percent of ethnic schools (including those teaching Italian) across all Australian states and territories (see Table 2).

Table 2. Estimated numbers of ethnic school and enrollments across States and Territories in Australia in 1980.Footnote 44

Source: Brian Bullivant, “Are Ethnic Schools the Solution to Ethnic Children's Accommodation to Australian Society?” Journal of Intercultural Studies 3, no. 1 (1982), 17-35, https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.1982.9963196

In 1981, through the Ethnic Schools Program established by the Federal government, approved ethnic school organizations received per capita funding of AUD$30 to help them support their efforts for language maintenance.Footnote 45 For a two-year period, the funding was allocated to ethnic organizations providing supplementary language programs for education-related purposes such as teacher salaries, curriculum and material development, equipment, and facilities rental.Footnote 46 While all states indicated their support for ethnic schools, only four states—NSW, SA, Tasmania, and Victoria—provided additional funding.Footnote 47

In Victoria, the task of providing community-led assistance to Italian migrants was taken up by, among others, the Melbourne-based Co.As.It. (Comitato Assistenza Italiani / Italian Assistance Association), an independent organization established in 1967 by Italo-Australians to support and strengthen cross-generational family ties as Italians integrated into Australian life. A key part of its activity was the delivery of language classes, initially offered in 1968 as “free Saturday classes for primary students of Italian background.”Footnote 48 Supported by financial assistance from both the Italian and Federal governments beginning in 1971, the classes were designed “to keep the Italian language alive in families of Italian origin to enable communication and understanding between the generations.”Footnote 49 The out-of-hours classes were offered in suburbs with high geographical concentrations of Italian speakers, and, owing to increasing number of parents wanting their children to learn Italian, there was marked growth in enrollment in the first three years of funding (see Table 3).

Table 3. Co.As.It. Italian language program, comparative figures, 1971-1973.

Sources: Co.As.It., Italian Assistance Association, annual reports from the years 1971-1973, Co.As.It. Historical Society Library.

Although enrollment grew quickly, there were several challenges in the provision of classes through ethnic schools. Even though many parents of children attending them felt they had a place alongside mainstream schools, and educational officials acknowledged the unique benefits of these classes, others in the Australian community considered them harmful and viewed the ethnic organizations’ efforts with some distrust.Footnote 50 Moreover, classes were often held in mainstream school settings, which rented out the space outside of regular school hours, and for some, “ethnic schools [were] often regarded as unwelcome intruders.”Footnote 51 Within classes, observers identified a range of pedagogical issues such as the frequent reliance on unqualified teachers, and the use of textbooks and teaching methods that were not up-to-date and were unsuitable for the Australian context. In addition, students were not always enthused given that classes were run after hours and on weekends.Footnote 52

While ethnic schools provided an opportunity for all language communities, and at times were the only means to teach a particular language, each ethnic community embarked on this teaching journey differently. For some groups, especially the Italian community, the limitations under which ethnic schools operated was an important stimulus to pursue alternative forms of delivery that brought languages closer to the mainstream.

Learning Italian in School—Insertion Classes

By the early 1970s, Italian organizations, with Italian government support, began to innovate by offering “insertion” classes: targeted language classes that were held in mainstream schools during the day.Footnote 53 Insertion classes were originally seen as additional to the standard curriculum, and in the first instance targeted children of Italian origin. While the undersupply of a suitably qualified teacher cohort was problematic, especially in the earliest phase, the introduction of insertion classes was a critical step in gaining a permanent foothold for Italian in the standard instruction of day schools. Very quickly, in a step supported by the Italian community, there was a push for Italian classes to be opened up to all students, not just those from an Italian background.Footnote 54 This was seen as “a move to bring the Italian community and the Australian school closer together.”Footnote 55 As a result, Italian classes, by agreement with principals and educational authorities, were soon offered during school hours to whole classes of students, not just to children of Italian origin.Footnote 56

Insertion classes were delivered for the most part by Italian organizations with experience and capacity in language teaching, most notably in Victoria through the Società Dante Alighieri and Co.As.It., although other organizations for a time also offered similar Italian classes in Melbourne and elsewhere in Victoria, including the Associazione Figli d'Italia, the Italo-Australian Foundation, and some of the many Italian social clubs.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, Co.As.It. and the Società were responsible for delivering between 80 and 90 percent of Italian insertion classes in the 1970s.Footnote 58

The Melbourne branch of the Società Dante Alighieri (also known locally as the Dante Alighieri Society) was established in 1896, the first outside Italy. It brought together Italians and anyone with a strong interest in Italian language and culture. Already experienced in adult teaching, the Society for a time delivered both after-school and insertion classes for children. The Society was, in fact, first to offer an insertion class in Italian (which it labeled formally as “corso d'inserimento”) to primary school children in Victoria, in 1971 at St. Gabriel's, a small Catholic primary school in Melbourne's northern suburbs. The initiative also appears to have been the first of its kind in the world to be supported by a new Italian law (Legge 153/1971) that allowed for the material support and funding of supplementary Italian language and culture courses for children of Italian descent attending local primary and early secondary schools.Footnote 59

This innovation, quickly adopted by many other schools, especially in the Catholic school system, was such a success that in addition to its many after-hours classes, by 1978 the Society offered seventy-eight insertion classes to 1,963 primary students. For a short period, it saw itself as leading the process of mainstreaming Italian in schools.Footnote 60 Unfortunately, the situation was untenable, given the huge cost of the Society's teaching programs. Severe financial restrictions caused by the rapid expansion of its insertion classes, coupled with repeated delays in receiving promised funds from the Italian government, led quickly to major conflict within the Society's governing committee, which voted as early as 1974 to remove the Society from all teaching to primary school students. The vote was, however, disregarded and it continued for a time to provide such teaching. Unfortunately, the financial situation remained so persistently difficult that a definitive and final decision to exit the field was made in December 1978.Footnote 61 The Society's after-school and insertion activities were taken over in 1979 by the newly established Italo-Australian Foundation, which in time merged with Co.As.It. The latter continues to this day to provide a wide range of services, including supporting the teaching of Italian in day schools.Footnote 62

By 1973, Co.As.It. had also begun offering insertion classes, alongside its after-hours programs. Beginning in two schools where 90 percent of students came from an Italian background, these classes also included a small number of students of language backgrounds other than Italian.Footnote 63 In 1974, a total of 1,685 students attended Co.As.It.'s insertion and after-school Italian classes, of which 93 percent of students were of Italian descent.Footnote 64 As the education program expanded to include more insertion classes, the number of students from other backgrounds attending them also grew. In 1975, the number of students learning Italian in Co.As.It. programs had increased from 1,685 to 1,880. This number included 570 students, of whom only 298 were of Italian descent, in insertion classes.Footnote 65 Mounting community demand for the teaching of Italian meant a steady growth in the number of both after-hours and insertion classes, leading to 2,000 students enrolled in 1976, and rising quickly to some 5,000 students in 250 classes in 1980 (see Figure 1).Footnote 66

Figure 1. Number of students in Co.As.It. classes, 1971-1980.

Sources: Co.As.It., annual reports 1971-1972; Kringas and Lewins, Why Ethnic Schools?

Increasing Prestige for Languages Education

While financial support for the delivery of Italian classes had initially been provided only by the Italian government through annual grants, in 1976 Co.As.It. also began receiving funds from both Federal and state governments.Footnote 67 Federal government grants ensured that the number of students and classes continued to grow, and the funding that was provided for the first time in 1981 by the Commonwealth Schools Commission helped Co.As.It. to “offer Italian classes during school time, free of charge.”Footnote 68 This combination of free insertion classes, coupled with an increasing emphasis on offering the language to all children, regardless of background, provided two critical elements that facilitated the massive expansion in the number of classes run by the organization.Footnote 69 However, as early as 1976, given the expanding number of students and concern about the associated financial burden, Co.As.It. had begun to question whether the type of services it was offering as a volunteer agency would be better delivered by the government instead, and continued to lobby the Victorian state government for it to implement a policy on community languages teaching in schools.Footnote 70

The considerable expansion in the number of insertion classes meant that in one year alone from 1980 to 1981, the number of Italian students in Co.As.It.'s insertion and after-school programs in Victoria had more than doubled from 5,000 to 11,000. As Figure 2 shows, there was even more exponential growth in 1982, to 22,623 students. The locations of insertion classes also expanded to eighty-one state and Catholic primary schools in metropolitan and country areas. This provision was so successful in reaching Italian children in schools, it had the tangential effect of reducing demand for after-hours teaching; in 1981 Co.As.It. delivered 120 “Saturday classes” in sixty-two locations to just some 2,000 students, falling to 1,503 students by 1983.Footnote 71 Remarkably, by this time 70 percent of students in its insertion classes were not of Italian background, with growth continuing at a substantial rate, increasing to some 25,000 students.Footnote 72

Figure 2. Number of students in Co.As.It. classes, 1981-1983.

Sources: Co.As.It., Italian Assistance Association, annual reports from the years 1981, 1982, and 1983, Co.As.It. Historical Society Library, Carlton, AUS.

Meanwhile, the Victorian state government was also becoming increasingly active in the area of community language education. In 1979, the Victorian Department of Education had created the Victorian Advisory Committee on Migrant and Multicultural Education (VACMME) to provide advice about migrant education and to make recommendations to the minister of education about curriculum projects, teacher training, and materials.Footnote 73 A nominee from Co.As.It. was appointed as the Italian community representative on VACMME, and in 1980, Co.As.It. signed the first of four memoranda of understanding with the Victorian Department of Education for the teaching of Italian in schools.Footnote 74 The success of the support by the Italian and the broader Victorian community toward the inclusion of Italian language programs resulted in the teaching of Italian in Victorian schools becoming the largest program outside of Italy, a remarkable achievement in such a short period of time.Footnote 75

To foster long-term opportunities in community language education across the board, stakeholders also recognized the need to improve the quality of delivery of language programs. Among the several promising strategies they identified were the development of standards regarding the quality of education, with funding and support services offered to enable ethic schools to improve their operations; the establishment of minimum qualifications for teachers with the provision of pre- and in-service teacher training programs to improve pedagogy; improved employment conditions; and the development of curriculum guidelines and materials, which became a shared responsibility between providers such as Co.As.It. and the Victorian Department of Education.Footnote 76

The Integration of Community Languages in Victorian Primary Schools

Over many years, lobbying for the introduction of community languages into the standard curriculum was taken up by many individuals and groups—from academics, linguists, and teachers to language associations and professional and community organizations.Footnote 77 Public meetings, such as the one organized by the important Italian community organization FILEF in Sydney in November of 1982, offered opportunities for dialogue between the Italian and broader communities, and fostered agreement and support for the teaching of Italian in day schools.Footnote 78 A key motivator for the supporters of the mainstreaming of Italian and other languages in government schools was the potential of language and cultural study to combat both racism and the pernicious belief that migrants should be forced to assimilate.Footnote 79 Moreover, mainstreaming was deemed important because it would provide opportunities for community participation and renewal of curriculum content and teaching methods.”Footnote 80 However, regardless of the Italian community's and Italian government's support for the mainstreaming of Italian, its realization was heavily dependent on the ability of different Australian governments (state and federal) to address rapidly changing community needs and wishes, and to manage the complex challenge of supporting community language teaching and language education more broadly in a detailed and comprehensive manner.Footnote 81

These endeavors came fully to the fore in Victoria in the 1980s through multiple policy documents. First, a series of six Victorian Ministerial Papers, originally issued in 1982, focused on collaborative and active ways in which social and educational disadvantage could be redressed. These papers detailed the type of education Victorian schools should provide and, importantly, included recommendations to enable students to “acquire proficiency in another language used in the Australian community.”Footnote 82

In 1982, the Community Languages Implementation Committee was also established with a remit to implement policy and support the teaching of languages in Victorian government primary schools as part of schools’ curriculum.Footnote 83 This was a significant change from the traditional position that dominated until the 1970s, whereby language teaching was seen as the domain of secondary schools. Despite the growing number of insertion classes in primary schools, language teaching was still considered an external add-on at the primary level for which they had no staffing or curricular responsibility.

Matters finally changed in 1983 when the Victorian government announced the appointment of fifty community language (CL) teachers in primary schools.Footnote 84 These teachers were employed through state funding as supernumerary teachers—that is, they were employed, above normal staffing loads, to teach a range of languages in Victorian government primary schools.Footnote 85 This was a considerable innovation and a critical step toward the full mainstreaming of community languages, such as Italian, in primary schools, and a significant departure from the provision of insertion classes and their teachers by community organizations, with funding sourced from different governments (e.g., state, Federal, and Italian).

Along with providing guidance and recommendations for school communities, Victorian policy documents also identified issues faced by schools offering language programs, including Italian ones. The 1984 Discussion Paper commented on the differing needs of student cohorts and the need to develop a trained language teacher workforce and curriculum materials. It also identified a range of recommendations to scaffold the burgeoning programs.Footnote 86 For example, due to the lack of accredited tertiary courses for training primary level teachers of Languages Other Than English, or LOTEs, the Education Department established the Languages Accreditation Committee as an interim measure, which, from 1984 to 1990, accredited primary teachers in the respective languages they taught, pending the availability of suitable courses.

Victorian government policy initiatives continued to drive the general expansion of language education. In 1985, a clearly articulated policy goal in the Report to the Minister for Education stated that “by the year 2000 a continued study in one or more languages [will have become] part of the normal educational experience of all children.”Footnote 87 In addition, in 1986, affirming that “all students should be able to communicate competently in a language or languages other than English,” policy guidelines developed for Victorian school communities advocated for a multicultural perspective, positioning languages as central to learning and supporting a rapid increase in language programs in primary schools.Footnote 88

The years of activity in favor of Italian insertion classes and the community's long-term desire for their full integration into normal schooling meant that experienced Italian teaching staff were already available and well prepared to take part in this desired expansion.Footnote 89 Table 4, which outlines language provision in Victorian state primary schools in 1985, is revealing on this point: Italian was the only language offered in insertion mode. With the appointment of additional primary school CL teachers in the same year, Italian was now also taught in 37 of the 108 state primary schools offering their own language programs in Victoria.Footnote 90 This figure is only a little less than the forty-three Italian insertion programs in the same sector.

Table 4. Language programs in Victorian primary schools, 1985

Sources: State Board of Education and MACMME, Report to the Minister for Education, 25-26.

In the years that immediately followed, the positioning of languages in education continued to advance, with the LOTE Framework P-10 placing languages on a par with other curriculum areas.Footnote 91 These efforts at the state level were strongly supported by the Federal government's formal adoption in 1987 of the National Policy on Languages (NPL).Footnote 92 The first multilingual language policy in the English-speaking world, the NPL had as one of its goals the broad provision of language education (including community languages) to all students in Australian schools.Footnote 93

To meet the needs identified at policy and planning levels, a variety of locally appropriate teaching and learning resources were developed across Australia. While significant progress was made in relation to curriculum materials, it became clear that the success of programs was predicated on the continuing commitment of staff and, owing to the competitive nature of school funding, it could be a hit-or-miss process.”Footnote 94 This notwithstanding, as more state government primary schools began to deliver languages programs, the number of teachers appointed to teach languages in primary school continued to grow and, by 1987, a total of 130 CL teachers were appointed and directly funded by the Victorian Department of Education. The largest proportion of these teachers (equivalent to 46.5 persons, or almost 36 percent) consisted of those assigned to teach Italian in forty-seven state primary schools.Footnote 95

While Australian states and territories remained primarily responsible during this time for funding and implementing policies to expand language programs in their schools, they also received specific financial support through two Federal programs. Initially under the auspices of the 1987 National Policy on Languages (NPL), the Federal government provided limited funding support to languages in schools through the Australian Second Language Learning Program (ASLLP). In a sign of things to come, in an effort to increase what was known as “Asia literacy” in Australia, the Federal government also began to target the specific provision of Asian languages through its Asian Studies Program, which commenced in 1988. Its goal was to ensure “all Australian school children have access to the study of Asian languages by the year 2000 [and] the study of Asia becomes part of the core program in Australian schools by 1995.”Footnote 96

Given all the drivers and initiatives identified to this point, the expansion of language program provision in primary schools began to take on new momentum and new dimensions by the start of the 1990s. This was so much the case in Victoria that the Victorian state government began to formally document program and enrollment information on a regular yearly basis from 1991. The first LOTE Report indicated that in 1991, 24 percent of all government primary schools were delivering languages programs, a significant increase on the 14 percent reported for 1989. Of the 370 provider schools in 1991, 155 had programs run internally with supernumerary teachers; seventy-five of these programs involved Italian. Sixty schools had insertion programs, fifty-eight of these specifically for Italian. A further 168 schools delivered language programs under other local arrangements, which included the sharing of teachers with other schools (including secondary) and the use of community volunteers or telematics (learning through technology). Of all the languages taught in primary schools in 1991, Italian had by far the largest number and proportion of students—31,178—a remarkable 54 percent of the total enrollment, a record percentage that has never been matched in Victorian government schools by any language since.Footnote 97

Competing Forces, Eppur Si Muove (and Yet It Moves)

However, by 1991, the focus of the Federal government had shifted somewhat away from community languages, toward an increased emphasis on English literacy and even greater engagement with Asia. As a result, the new Australian Language and Literacy Policy (ALLP), which replaced the NPL, again identified Asian studies and the study of Asian languages as priority areas for Federal funding, while still providing some funding for languages more generally.Footnote 98 This strong regional focus would lead eventually in 1994-1995 to a new national, long-term initiative to implement the teaching of Asian languages and studies through the National Asian Languages and Studies in Australian Schools (NALSAS) Strategy. All education authorities were part of this initiative, and the Federal government allocated yearly funding of approximately $30 million until the end of 2002.Footnote 99

Competing policy interests at state and Federal levels had to be managed carefully. The Victorian government, while partly acknowledging the Federal government's desired policy shift and funding incentive, continued to also advocate strongly for its diverse communities. The establishment of the Ministerial Advisory Council on Languages Other Than English (MACLOTE) in 1993, and subsequent LOTE Strategy Plan, served to demonstrate the Victorian government's commitment to the teaching of languages, and set priorities and directions for the short and long term. Stating an overall goal to achieve growth in language teaching, the Victorian government recognized “Australia's past neglect of the study of languages other than English in general, and Asian languages in particular.”Footnote 100

Nonetheless, it also aimed for a balanced approach to language teaching, favoring neither European nor Asian languages. As a result, when each state was asked by the Federal government to identify eight priority or key languages for specific funding purposes, Victoria's choice of Chinese, French, German, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Greek, and Vietnamese was “based on present demand and enrolments and is a reflection of community interests and consensus.”Footnote 101 But even this selection was carefully framed within a larger, state-based policy setting that favored a plurality of languages.

Table 5 lists and compares the number of internally run, face-to-face programs in these priority languages from 1991 to 1996. It illustrates the rapidly expanding and changing shape of language instruction in Victorian primary schools, balancing Federal and state-based imperatives for the rapid expansion of language education. Notably, in 1991 Italian had a significant head start. In addition to there being fifty-eight insertion programs (see Table 6), fully half of the relatively small number (n=150) of primary school-run priority language programs involved Italian. By 1996, the number of all such programs had increased more than sevenfold to 1,121 in only five years. The otherwise remarkable quadrupling in the number of schools offering such programs in Italian (increasing to 325) in that period was overshadowed by the truly exponential growth in the provision of Asian languages, in particular Indonesian and Japanese—which occurred in large part because of strong federal incentivization. By 1996 expansion of language programs across the sector was practically complete: almost 97 percent of all primary schools now provided at least one language program in some format, e.g., through internally run and insertion classes.Footnote 102 Overall, Italian still remained the most commonly taught language, available in 24 percent of primary schools.

Table 5. Number of Victorian government primary school offering department-supported face-to-face programs in eight key languages, 1991-1996.

Sources: DSE, Languages Other Than English in Government Schools, 1991-1996. DSE, Languages Other Than English, 1991-1993, 1995; DSE, Languages Other Than English, 1994 (Melbourne: DSE, 1995); DSE, Languages Other Than English, 1996 (Melbourne: DSE, 1997).

Table 6. Number of government schools teaching Italian by mode, 1991-1996.

Sources: DSE. Languages Other Than English in Government Schools, 1991-1996.

During this period, changes to language education staffing and funding also occurred. With regard to supernumerary CL teachers, it had been anticipated by the Victorian government that, in the long term, it would be “unlikely that it will be possible for such provision to be made at the primary level indefinitely,” and so, at the end of 1993, supernumerary staffing was discontinued and replaced by a new LOTE Special Needs allocation.Footnote 103 A further change occurred in 1996 whereby all schools were now directly and regularly funded to offer and staff their own language programs as part of their regular curriculum and staffing: the teaching of a broad range of languages was technically now properly integrated into the Victorian primary school education system. In practice, there was still some hesitation, and Co.As.It. continued to provide some insertion classes (see Table 6).

While policy directions, changes to funding, and the targets set by the LOTE Strategy Plan were important drivers in terms of mainstreaming languages including Italian, a further contributing factor was the introduction of the technology-based Primary Access to Languages via Satellite (PALS) programs. Originally piloted in 1994 to deliver Italian and Indonesian language instruction through television-based interactive programs to students in Year 5 and 6, they offered opportunities for schools to either supplement their existing face-to-face teaching or enabled schools that would not have been able to teach Italian or Indonesian directly to do so.Footnote 104

The relative impact of all these factors on the teaching of Italian is illustrated in the increase or decrease in the different modes of delivery in the period 1991-1996. Trends outlined in Table 6 show the rise in the number of Italian programs delivered face-to-face, and which, in 1996, reached the highest number ever achieved for instruction of the language in Victorian government primary schools. With Italian being the language most frequently selected, the opportunities afforded by the PALS broadcasts further increased the delivery of Italian programs in primary schools, which reached its peak in 1996 before the PALS programs were terminated at the end of 1999.

The shifting nature of program types encapsulates a significant turning point for the study of Italian in Victoria. The progressive disappearance in the number of schools offering Italian through their own initiatives (e.g., parent volunteer programs) is explained by the introduction of the PALS programs and by the change in government arrangements that now provided guaranteed funding to support schools’ internal staffing of languages programs. Similarly, the number of insertion classes, pivotal in ensuring the position of Italian within the primary school curriculum, decreased during the 1990s and was then no longer noted in the data after 2002.Footnote 105 From this point on, by agreement with the Victorian government, the insertion mechanism was no longer used, and all Italian programs in Victorian state primary schools were now fully mainstreamed—a remarkable achievement—three decades after the first insertion class in 1971 in any Victorian school.

Concluding Comments

For many decades after the Second World War, the Italian community was the largest non-English-speaking migrant group in Australia. The size of the community, coupled with strong support from organizations such as Co.As.It. and the Dante Alighieri Society, from the Italian government as well as from within the Italian community itself, was undoubtedly advantageous with respect to moving from an ethnic school model of after-hours language teaching to the wider acceptance of the teaching of Italian.

The mainstreaming of Italian in schools, however, was not a simple linear process. Instead it involved numerous significant steps including: a leveraging of possibilities and opportunities; the effective use of funding mechanisms; adept movement across educational spaces; and a desire by community members and organizations to allow non-Italian Australians to engage deeply with their language and culture. Concurrent drivers, alongside these factors, included progressive change in societal and governmental views toward multiculturalism and the teaching of languages in Australia, as illustrated through the introduction of numerous policy documents and initiatives as well as changing policy discourses. The analysis also highlights the tensions between state and Federal policy-making. This was illustrated by the progressive policy-making on the part of the Victorian state government in its support of community language education, establishing strong foundations for prioritizing the learning of a wide range of languages, including Italian, in the state of Victoria. As a result, even when the Federal government initiated a push for the preferential treatment of Asian languages, the inclusive practices of the Victorian state government in particular helped to protect the hard-earned gains of the Italian community and its supporters in Victoria.

By drawing on detailed historical analysis of earlier accounts, policy texts and discourse, and broader societal movements, as well as on a new analysis of primary data recorded by a range of governmental and non-governmental entities, we have been able to develop a renewed and fuller understanding of the progressive mainstreaming of Italian language education in Australian schools. In doing so, we have illustrated the complex interaction between community aspirations, activism and activity, and policy development and implementation by different levels of government in an Australian context.

Looking forward, a comparative analysis of political and social developments, as well as of changes in language policy and language education across different Anglophone nations that have all received large numbers of Italian migrants, would allow us to build a deeper understanding of the drivers that have mitigated for and against the positioning of Italian in education systems across the English-speaking world.