It is Government policy that increased attention should be given to the quality (as well as the quantity/efficiency) of clinical care. To achieve this, it has set national standards through the National Service Framework for Mental Health (NSF—MH; Department of Health, 1999a) and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE).

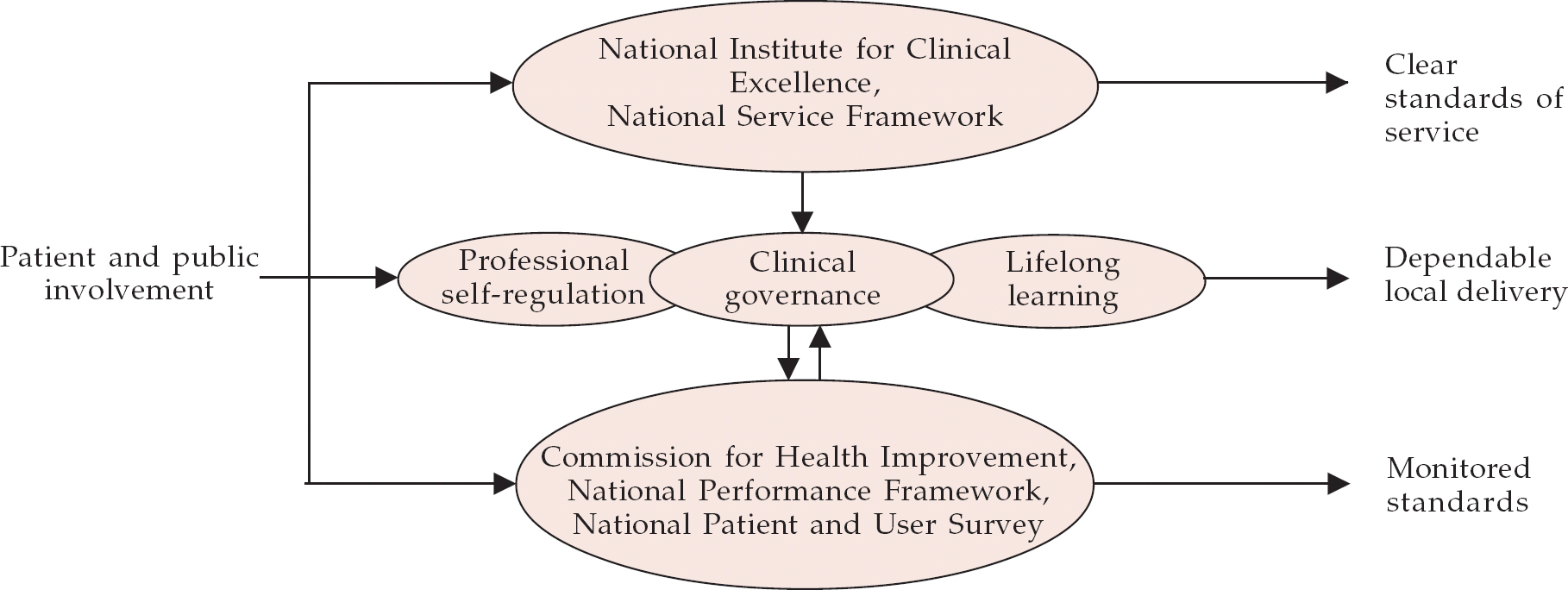

Clinical governance, lifelong learning and professional self-regulation are the methods by which the Government hopes to deliver these improved standards of care. The standards will be monitored through three new mechanisms: the Commission for Health Improvement, the National Framework for Assessing Performance and an annual National Survey of Patient and User Experience. There will be patient and public involvement at all stages of the process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The quality framework (Department of Health, 1999b )

NSF and NICE

The NSF—MH sets seven standards for mental health (Box 1). Some regional national health service (NHS) executives have supplemented the NSF—MH with a regional framework.

The functions of NICE are to: provide guidance to the NHS on the clinical and cost-effectiveness of treatments and technologies through rigorous review of available evidence; provide information to the NHS on audit methodologies; support national audit; and provide support for confidential enquiries.

Box 1. National Service Framework Standards for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999a )

-

1 Health and social services should: promote mental health for all, working with individuals and communities; combat discrimination against individuals and groups with mental health problems; and promote their social inclusion.

-

2 Any service users who contact their primary health care team with a common mental health problem should: have their mental health needs identified and assessed; be offered treatment, including referral to specialist services for further assessment, treatment and care if they require it.

-

3 Any individuals with a common mental health problem should be able to: make contact 24 hours a day with the local services necessary to meet their needs and receive adequate care; use NHS Direct, as it develops, for first-level advice and referral to specialist helplines or to local services.

-

4 All mental health service users on the Care Programme Approach (CPA) should: receive care that optimises engagement, prevents or anticipates crisis, and reduces risk; have a written care plan that includes the action to be taken in a crisis by service users, their carers and their care coordinators, advises the GP how to respond if the service user needs additional help, and is regularly reviewed by the care coordinator; be able to access services 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

-

5 Each service user who is assessed as requiring a period of care away from home should have: timely access to an appropriate hospital bed or place, which is in the least restrictive environment with the need to protect the patient and the public and as close to home as possible; and a copy of a written after-care plan agreed on discharge, which sets out the care and rehabilitation to be provided, identifies the care coordinator and specifies the action to be taken in a crisis.

-

6 All individuals who provide regular and substantial care for a person on the CPA should have: an assessment of their caring, physical and mental health needs, repeated at least annually; their own written care plan, which is given to them and implemented in discussion with them.

-

7 Local health and social care communities should prevent suicide by: standards 1—6 above; supporting local prison staff in preventing suicide among prisoners; ensuring that staff are competent to assess the risk of suicide among individuals at greatest risk; developing local systems for suicide audit to learn lessons and take necessary action.

Clinical governance

Clinical governance ensures that NHS organisations (specifically, their chief executives) are accountable for continuously improving and safeguarding the quality of their services by creating an environment in which excellence in care will flourish (Box 2).

Box 2 Components of clinical governance

Clear lines of responsibility and accountability for quality of clinical care

Comprehensive programme of quality improvement activities

Clear policies aimed at managing risk

Procedures to identify and remedy poor performance

Lifelong learning: continuing professional development

A First Class Service: Quality in the NHS sees lifelong learning (continuing professional development, CPD) as an integral element of clinical governance:

“Clinical governance needs to be underpinned by a culture that values lifelong learning and recognises the key part it plays in improving quality” (Department of Health, 1999b ).

It is intended that CPD programmes should meet the needs both of the individual and of wider service development within the NHS. The delivery of CPD is seen as the responsibility of a variety of stakeholders, including higher education providers, education consortia and the medical Royal Colleges.

CPD is seen as a valuable tool in attracting, motivating and retaining high-calibre professionals. A First Class Service continues:

“We support the identification of professional and service needs in a Personal Development Plan (PDP) developed by the individual health professional in discussion and agreement with colleagues locally. This should: take into account different learning preferences; clearly identify where team or multi-professional learning offers the best solution; and take full advantage of opportunities for learning on-the-job. Organisations will be encouraged to complement individual PDPs with organisational development plans.”

The College's educational strategy (available from the Postgraduate Educational Services Department, Royal College of Psychiatrists, 17 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8PG) states that:

“the transition from training to career grade is far from being the end of an educational process — it is merely a move from one stage of lifelong learning to another. CPD is the framework within which the College helps maintain the skills of today's and tomorrow's psychiatrists. CPD should complement practice-based learning and help all psychiatrists working in consultant and other non-training grades to remain interested in and stimulated by their work”.

The College has begun to develop a system of CPD that is flexible and sensitive to individual needs (Box 3). However, individuals must themselves identify their educational needs and preplan their educational programmes on the basis of their objectives, derived from the needs identified.

Box 3. The Royal College of Psychiatrists' role in continuing professional development (CPD)

Coordinating and providing CPD

Validating training courses

Certifying attendance at CPD-validated events

Monitoring the overall CPD programme for individuals

In 1995, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists carried out an educational needs assessment of their members (Reference MayneMayne, 1995). This confirmed an earlier finding that reading remained the most valuable educational resource. Attendance at conferences and meetings was highly valued and gave the opportunity to interact with peers. It was also seen by members as an efficient way of acquiring new skills and knowledge within a relatively short time. The preferred presentation styles identified in this study were workshops, seminars, expert lectures, case discussions and study groups. The two areas identified by most members as an educational need were the psychotherapies and the management of personality disorders. I would expect similar findings if such a needs assessment were carried out among our own College members.

It is recognised that CPD is likely to be central to any revalidation system and clinical governance framework, and that the College's role in CPD is likely to increase in view of the need to promote a more open identification of problems. Consequently, it is essential to ensure that there is appropriate identification of remedial educational requirements and adequate provision for addressing the identified needs.

Professional self-regulation

In January 1998, the General Medical Council (GMC) stated that specialists and general practitioners must be able to demonstrate on a regular basis that they are keeping up to date and fit to practice. However, at present only if complaints are made does a review take place to ascertain whether an individual should be removed from the Medical Register. There is therefore a move towards requiring clinicians regularly to provide evidence that they are competent and fit to practice, rather than relying on retrospective external evidence that they are unfit, as is currently the case. We must affirm good practice, encourage continual improvement and enhance trust in the medical profession.

The GMC and the medical Royal Colleges are committed to revalidation and are planning to have a blueprint available by May 2001. Revalidation will involve regular assessment to ensure that doctors are and remain competent. It is likely that these assessments will need to be tailored to individuals, as consultants carrying the same title and working within the same organisation may carry out very different work. It is likely that the assessment process will have three stages.

Stage 1 will be a local process, which should include local profiling of performance, periodic external peer review of the profiling process, a method of providing evidence leading to revalidation of the doctors' entry in the Medical Register and local remediation when this is necessary.

Stage 2 will involve assessment and support centres run jointly by the NHS and the medical profession. The medical Royal Colleges that provide professional standards relevant to each medical speciality should play a major role at this stage.

Problems that cannot be addressed at stages 1 or 2, or are considered to have implications for a doctor's registration, are referred to the GMC: this is stage 3 (Department of Health, 1999c ). The GMC has already agreed to tighten procedures relating to doctors who have been removed from the Medical Register. Doctors have to wait for 5 years (instead of 10 months) before they can apply for re-registration. The GMC's professional conduct committee also have powers to suspend indefinitely the right to reapply for restoration of a doctor who has twice failed to be restored to the Register. Doctors applying to be re-registered are required to provide evidence of knowledge and skills demonstrated through a formal assessment (Medical Act 1983 (Amendment) Order 2000).

The Royal College of Psychiatrists' revalidation steering group has agreed that revalidation is a registration function of the GMC, but that it could delegate certain functions (yet to be defined) to the medical Royal Colleges, although the GMC would retain overall responsibility and accountability.

A personal development plan (PDP) may contribute positively to appraisal and assist in professional self-regulation, especially if the process by which it was drawn up included robust peer review. In this context, it is important that such review be carried out by respected colleagues in the same field, and it may supplement appraisal by one's ‘line manager’, who should also be from the same professional background.

The British Medical Association's Central Consultants and Specialist Committee (CCSC) has drawn up a framework for revalidation which it will be presenting to the GMC (British Medical Association, 1999). The CCSC suggests that revalidation should be based on the GMC's (1998) guidance on good medical practice. It should not set out to establish new standards, but should aim to underpin the quality of medical care by ensuring that existing standards are complied with and underperformance minimised. It suggests that revalidation of consultants should occur through a combination of appraisal, audit, CPD and external peer review. It recommends that revalidation operate uniformly across the UK and be introduced simultaneously for all branches of the medical profession. Following discussions between the GMC and the medical Royal Colleges, it has been agreed that each College should prepare its own version of Good Medical Practice, as this will be the template used by the GMC for revalidation (see Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2000).

The Government has stated that self-regulation should have two broad functions (Department of Health, 1999c ). First, to determine which individuals should enter and remain members of a health profession at different levels and in different fields of practice. Second, to support health organisations in achieving high standards of quality by means of clinical governance at local level and of other structures and processes at national level. The five principles for effective self-regulation are shown in Box 4.

Box 4 Principles of effective self-regulation

Transparency

Accountability

Targeting

Consistency

Proportionality

Personal development plans

Extensive evidence emphasises the importance of needs assessment when designing and delivering adult education (Reference Curry and PutmanCurry & Putman, 1981; Reference SteinStein, 1981; Reference Davis, Thomson and OxmanDavis et al, 1992). Needs assessment can be defined as the objective determination of practice or learning needs. The literature also shows that when delivering an educational activity, didactic instruction alone is not sufficient. Activities that encourage participation, discussion and practice are considered to be more effective (Box 5).

Box 5 Components of effective adult learning

Needs assessment

Direct experience of the learning task

Feedback and experience of the results

Review and reflection

Conceptualisation

Testing out in the real world

As stated above, attendance at conferences and meetings is highly valued (Reference MayneMayne, 1995). When preparing educational activities, conference organisers need to be mindful not only of their educational content, but also of the method of delivery. An unscientific look at the Royal College of Psychiatrists' programmes and Faculty conferences over the years shows a shift towards participatory activities. My own experience, however, is that many intended workshops end up being small group lectures.

Literature on adult education also shows that the two most important factors that affect learning are motivation, whether internal or external, and feedback confirming success rather than failure (Open University, 1994). Feedback that confirms or highlights failure tends to demotivate.

For a PDP to be effective, it must therefore include an element of needs assessment in which the participant directly takes part in identifying his or her own needs. Once identified, these needs should form the basis for setting clear learning objectives. There must also be the opportunity for discussion and feedback.

Setting clear learning objectives can be a difficult task. They must be set in the context of a job plan that takes into account the employing organisation's aims and objectives. However, there should also be personal objectives, consistent with, although not dependent on, other strategies within the organisation. The learning objectives should be specific, measurable, attainable, resourced and time-limited (SMART). They should also be challenging, interesting and valuable. Common problems associated with lack of achievement in meeting objectives or making progress in attaining educational or career goals are that the objectives set are vague and non-specific, cyclical (revisiting old ground), uninformed (because they are not needs-based), unmonitored and do not take into account changing circumstances. Feedback and review are essential to avoid these pitfalls.

Needs assessment is an integral component of a good PDP and effort must be taken to do this properly and to get honest feedback. We all have a tendency to prefer doing the things we enjoy and are probably very good at and to avoid areas in which we need help.

Box 6 shows the essential components of a PDP and areas to consider when devising one.

Box 6 Personal development plans (PDPs)

Essentials of a PDP

Based on needs assessment

Clear learning objectives, which are:

Specific

Measurable

Attainable

Resourced

Time-limited

Allow for discussion and feedback

Areas to consider in devising a PDP

Job-specific training and educational requirements: needed to carry out one's job effectively

Continuing development within one's job/role: take into account future developments and changes of role

Personal development needs: may be independent of one's current role

Some consultants may have job plans that clearly state and define their tasks and objectives and the context of the job in terms of the team and organisation in which they work. However, this is probably the case for only a minority of us. Most of us have jobs that are too complex and dynamic for this to be practical: even if we did have such a job plan when we started, it is almost certainly now out of date.

A PDP is more than a job plan, and it is essential for personal development. Medical directors and other medical colleagues acting as line managers have an important role in helping with the needs assessment for some components of an individual's PDP (e.g. job-specific issues), and in supporting and reviewing PDPs and the resources required; they also have a role in prioritising the job-specific objectives. However, I believe that they should not be in a position to direct all aspects of a PDP; indeed, there may be some areas that an individual wishes to keep private.

Even if one has a good idea of what a PDP is and what one should include in it, it can still be difficult to produce. One method of identifying the SMART objectives and defining the PDP's aims is to ask a series of questions, such as:

-

1 Where am I now?

-

2 Where do I want to be in x years' time?

-

3 How do I get to where I want to be?

-

4 What resources (government policy, key individuals, training opportunities, etc.) could help me?

-

5 What is hindering/may hinder me from getting there?

The key is to focus on questions 2 and 3 and not to get bogged down in question 1. Use clinical governance, the NSF and other policies and initiatives to strengthen your voice and to underpin your PDP.

Box 7 shows the basic notes and documentation relating to a PDP that must be kept for reference to ensure that all stages of the process (i.e. needs assessment, setting of objectives, strategy for meeting objectives and review) can be achieved. It is likely that some objectives will take longer to achieve than others and also that some will be more urgent or important than others. It is important to reflect this when looking at the strategy (CPD) for meeting ones objectives.

Box 7 Minimum data set for PDPs

Name

Dates of reviews

Attendees at reviews

SMART objectives (1—3)

Strategy for achieving objectives (educational activities, resources, time limit)

Measure of success

Discussion and feedback are essential in personal development planning. One way of providing them is through mentoring. Little has been published on mentoring or on the evaluation of mentoring programmes, although both mentors and those they advise (whom I shall call ‘mentees’) seem to benefit from the relationship. There is some evidence that mentoring may specifically aid learning (Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education, 1998). The term mentoring, however, has many meanings and its concept overlaps with other roles, for example that of counsellor, supervisor, buddy, tutor, appraiser and even assessor. There is also some antipathy to the term itself. The most common model for mentor is that of a critical friend, trusted and respected peer or more experienced colleague who enables personal and professional development. It is extensively used among professionals outside medicine and is often used with undergraduate and postgraduate students, high-fliers and for people in transition.

The Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education (SCOPME) set up a working group on mentoring (SCOPME, 1998). It believes that mentoring should be a positive, facilitative and developmental activity, that should not be related to or form part of organised systems of assessment or performance monitoring. It should be an integral part of the overall provision of personal, professional and educational support for doctors and dentists. This support is seen as a prerequisite for learning, enhanced quality of education and professional development, and thus for improved professional performance.

The primary requirements for an effective mentor/mentee relationship listed by SCOPME are shown in Box 8.

Box 8 Requirements of an effective mentoring relationship

Mutual commitment and respect

Early negotiation of explicit relationship boundaries

Formally planned, but informally conducted sessions

Absolute confidentiality

Mentees who can and should be mentors for others

Voluntary participation

Mentors who are not the direct line manager of the mentee

Vigilance for signs of a dysfunctional relationship: overdependence, abuse of power, destructive criticism, excessive direction, inappropriate emotional attachment and cross-gender power play

It is important to recognise that it will take time for mentoring to be effective and constructive. Mentors will require training and ongoing support. SCOPME identified a number of potential problems, including the direct and indirect financial costs of effective mentoring, mentor fatigue, the ‘toxic’ mentor and the rejected mentee.

An alternative to the individual mentor/mentee relationship that provides for discussion and feedback is the development of mentoring groups consisting of six to eight individuals. These have been tried by forensic psychiatrists in the north-west of England, who thought them more supportive and less intimidating than one-to-one relationships. However, their groups disbanded because of lack of a supportive infrastructure. Some general psychiatrists in the north-west also formed learning sets as a way of meeting and providing support. Neither of these attempts has generated published reports. All such groups require persisting commitment from their members, and one way of encouraging this might be to attach it to already established and well-supported educational and peer activities, for example Royal College of Psychiatrists quarterly meetings and workshops.

The reduction in the working hours of junior doctors might have resulted in a reduction in clinical experience for the trainee, especially in specialities where a significant proportion of clinical work stems from emergency referrals. In psychiatry, this may not be such a problem. However, with the tighter contracts for specialist registrar training, junior doctors may become consultant psychiatrists with less clinical and other relevant experience than in the past. Under such circumstances, CPD and in particular some form of mentorship will, I think, be crucial to support newly appointed consultants.

There is currently much discussion and debate within the medical profession on self-regulation, and there are likely to be changes in the role of the medical Royal Colleges in relation to this and to CPD. I believe that PDPs will play an integral role in self-regulation and in ensuring and maintaining good-quality and improving clinical care. The Royal College of Psychiatrists needs to decide how prescriptive and directive it wishes to be in relation to the process of personnel development planning. The College's strategy to support PDPs must be flexible, but robust enough to carry the confidence of the profession, the public and the government.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Clinical governance:

-

a is about improving quality of health care

-

b is about improving efficiency of health care delivery

-

c is the responsibility of a trust's chief executive

-

d requires the active participation of practising clinicians

-

e requires effective risk managment.

-

-

2. Personal development plans:

-

a are the same as job plans

-

b should be discussed with the medical director

-

c can be imposed by the medical director

-

d should be reviewed annually

-

e should be needs based.

-

-

3. Factors that affect adult learning include:

-

a direct experience of the learning task

-

b feedback and experience of the result

-

c method of delivery

-

d having a basis in needs assessment

-

e clear application for the participant.

-

-

4. Professional self-regulation:

-

a needs to have the confidence of the public

-

b does not involve non-doctors

-

c includes revalidation

-

d requires changes to the current process

-

e must be strictly confidential.

-

-

5. Concerning revalidation:

-

a CPD is important in any revalidation

-

b the College is likely to have a role in it

-

c it does not require peer review

-

d the GMC will be involved at an early stage

-

e it is a registration function of the GMC.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| a | T | a | F | a | T | a | T | a | T |

| b | F | b | T | b | T | b | F | b | T |

| c | T | c | F | c | T | c | T | c | F |

| d | T | d | T | d | T | d | T | d | F |

| e | T | e | T | e | T | e | F | e | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.