INTRODUCTION

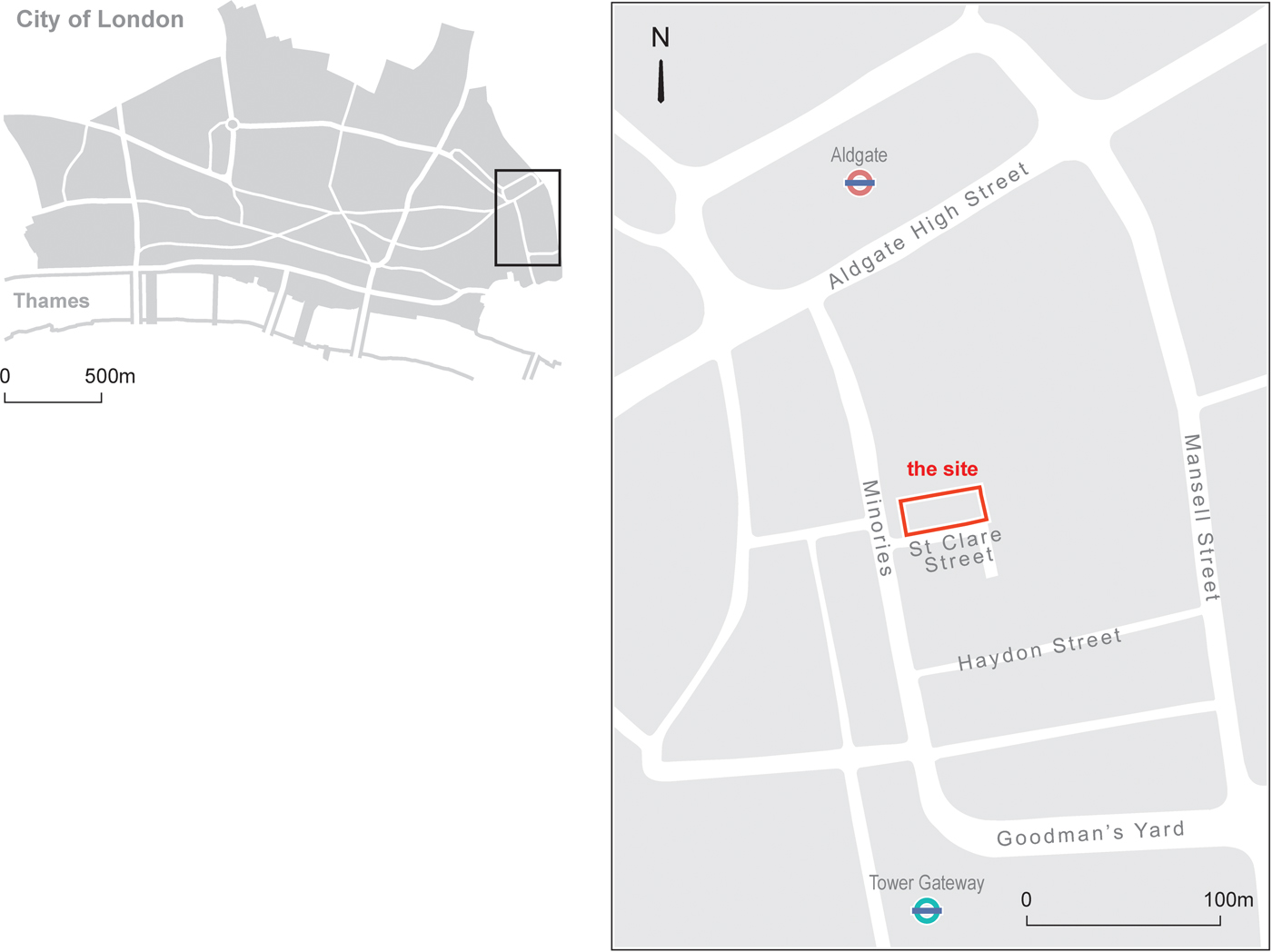

In the spring and summer of 2013 Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) undertook a developer-funded excavation of the site of 24–26 Minories, within the City of London, EC3N (site code: MNR12, NGR 533660 181065) (fig. 1). Redevelopment of the site comprised the demolition of a 1960s office block to make way for a 16-storey hotel by investor Aberdeen Asset Management and developer Endurance Land.

FIG. 1. Site location (scale 1:5,000).

On the last day of the excavations, the stone sculpture of an eagle and serpent was recovered from the fill of the roadside ditch in the south-east corner of the site. The sculpture was initially displayed in the Museum of London and published in the Corpus of Roman Sculpture from London and the South-East.Footnote 1 The purpose of this paper is to provide further information on the sculpture: the contextual background of the find, an in-depth discussion of the iconography of the sculpture and the results of the petrological examination.

The sculpture comes from within the cemetery located east of the Roman town and is an important addition to the body of religious and funerary stone sculptures from London. While there is ample evidence for funerary structures such as mausolea and monuments, freestanding sculpture from the eastern cemetery, and indeed the London cemeteries as a whole, is rare.Footnote 2 In the late third and fourth centuries considerable robbing of funerary monuments took place for incorporation into the late Roman defences. London's cemeteries provided a local and immediate source of cut stone, perhaps from tombs and monuments that had long since been unattended. These include the tombstone of a young girl, Marciana, recovered from Bastion 4 at Crosswall, Vine Street,Footnote 3 near the southern limit of the eastern cemetery, and part of the funerary inscription from the tomb of the first-century procurator Julius Classicianus, found in the bastion at Tower Hill.Footnote 4 The tomb is likely to have been located in the eastern cemetery, though its precise location is, of course, unknown. The distinct advantage of the Minories eagle is that it is stratified and likely to have been situated locally.

The remarkable state of preservation of the eagle makes it one of the best examples of sculpture surviving from Roman London but it is extremely fortunate that it has come down to us at all. Only two sections of the ditch survived in the central and south-eastern part of the site, the rest having been removed by medieval and post-medieval cesspits and cellars or modern basements and piling which destroyed large areas of the Roman sequence.Footnote 5

THE CONTEXT OF THE FIND

The site is located some 200 m east of the third-century a.d. Roman city defences on the route of the cemetery road (fig. 2). The eastern cemetery is thought to have been established around the end of the first or beginning of the second century a.d. and continued in use into the fifth century.Footnote 6

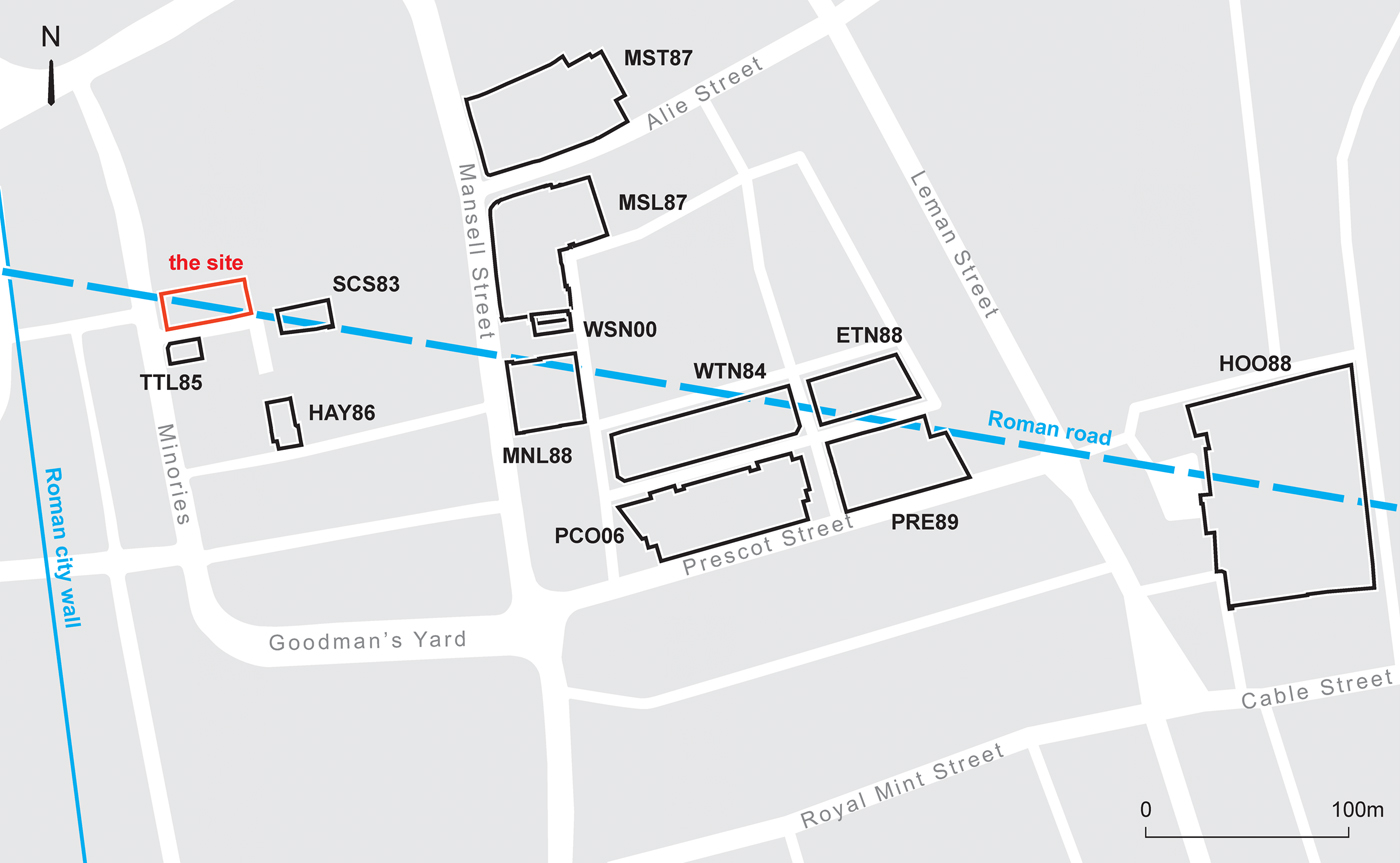

FIG. 2. The location of MNR12 in relation to sites excavated in the cemetery east of the Roman city along the course of the access road (scale 1:5,000).

The excavations revealed the course of the cemetery road and its north-flanking ditch running roughly on the east–west alignment projected from nearby sites.Footnote 7 The road appears to have been in use by a.d. 69–96 judging from the finds recovered in its associated north-flanking ditch and remained in use until the fourth century. The first-century road is contemporary with a small number of gullies and ditches which may have divided the cemetery area into burial plots, as seen elsewhere in the cemetery,Footnote 8 but only a small cluster of pits and dumps survived within their boundaries (fig. 3).

FIG. 3. The site in the second century a.d. showing the location of the eagle sculpture in the roadside ditch (scale 1:400).

The ditch was recut on two occasions: firstly at the turn of the second century and a second time before the mid-third century. Following the backfilling of the first-century ditch, a square mausoleum or funerary monument with stone foundations was built up against its north bank. Nearby lay the chalk-lined burial of an adult female, perhaps located together with the mausoleum in a roadside family plot. The latest inhumation on the site was the late Roman burial of a young adult dated a.d. 250–400. Further details of these burials are discussed in the online supplementary material, where the Roman narrative is presented together with a description of the ceramics, finds and environmental material.

The eagle-and-serpent sculpture was recovered from the fill of the late first-/early second-century roadside ditch (fig. 3). The eagle was carefully placed in the ditch and covered with a thick sandy deposit; a small contemporary group of ceramics dates the deposition of the sculpture to the period a.d. 120–60. The date of the associated finds suggests that the sculpture was buried not very long after it was carved. Some effort was made to dispose of it carefully, though there is nothing to suggest that the sculpture and these items were deliberately placed together.

THE MINORIES EAGLE: A MASTERPIECE OF SOUTH COTSWOLD SCULPTURAL ART By Martin Henig

The eagle <S 1> (figs 4–8) is carved in the round, though the rear of the sculpture lacks the careful detailing of the front, and the eagle's wings are somewhat curved on the upper side, which suggests that it fitted into a niche.Footnote 9 The right wing was broken off at the time of discovery and the left eye of the bird has sustained slight damage. Height: 0.66 m; Width: 0.55 m (including wings); 0.46 m (without wings); Depth: 0.23 m.

FIG. 4. Front view of the eagle and serpent sculpture <S 1>, height 0.66 m.

FIG. 5. Back view of the eagle <S 1>, showing the outline of the serpent, height 0.66 m.

FIG. 6. Side detail of lower left (facing) to show the curving tail of the serpent and the claws of the eagle.

FIG. 7. Detail of the chest feathers showing imbrication.

FIG. 8. Detail of the serpent's head with tongue.

The statue depicts an eagle, with wings partially spread, shown frontally but with its head turned in profile to the left. It has powerful talons with three segmented toes on each foot in front, each with a claw which clutches the low base on which the bird is mounted. The eagle firmly clasps a very long, writhing serpent in its beak.

On the front both bird and snake are meticulously carved in a yellowish oolitic Cotswold limestone (see Hayward, below). The eagle's plumage consists of feathers of varying length and profile. There are short ovoid ones with prominent central spine in the region of the neck which rather resemble the imbrication which is often to be seen on column shafts, so called from its resemblance to overlapping roof-tiles, reminiscent in form of the laurel leaves on the bolsters of Classicianus’ near-contemporary tomb monument.Footnote 10 Their length increases lower down and especially in the wings which terminate in long slightly curving pinions. Their rich texture is characteristic of the Flavian-Trajanic period and may be compared with the masterly carving of the wings of the Colchester sphinx or the wings in the hair of the gorgon on the pediment of the Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath.Footnote 11 While the body of the serpent is less detailed, its expressive head and exaggeratedly forked tongue, so suggestive of malice, is the creation of a very accomplished sculptor. There has been no attempt to detail the back of the sculpture, either to indicate the eagle's plumage or the writhing body of the snake, though the body of the snake is portrayed winding under the eagle's left wing, with its head and neck emerging only to be seized by its adversary.

The sculpture appears somewhat curved seen from the back probably to allow it to fit snugly in an alcove or niche. The sculpture stands on a low rectangular base. Comparison may be made with the low base of the much later, third-century sculpture of a boy from Westminster carved from a French limestone, which was most probably likewise a funerary sculpture from within a mausoleum.Footnote 12 It is probable that the eagle would have stood upon a plinth, perhaps containing a receptacle for the ashes of the deceased in a setting similar to that in the tomb of Sabinus Taurius at Isola Sacra.Footnote 13 An inscription commemorating the deceased might well have been affixed to this stand.

Eagles were pre-eminently the cult bird of Jupiter and the much smaller (and less well-executed) carvings of eagles from the Gloucestershire Cotswolds, from Cirencester, Somerford Keynes and Spoonley Wood, all very probably accompanied images of the god.Footnote 14 A Purbeck marble sculpture of an eagle, shown facing and carved in relief, was excavated at the mid-first-century fortress of legio II Augusta at Exeter and is probably of Neronian date. The bird is depicted frontally and unfortunately now lacks its head and lower legs, but the plumage is skilfully delineated.Footnote 15

Fully in the round and much smaller than these, albeit as finely detailed as the Minories eagle and of about the same date, is the cast copper-alloy eagle from the site of the Basilica at Silchester, in a context which can now be dated no later than the early second century (fig. 9a).Footnote 16 The wings of this eagle were spread above its back, probably extending above its head, but though its stance may have been a little different from that of the Minories eagle, the rich plumage suggests it was a product of the same Neronian-Flavian period. It is probable that the Silchester eagle was an attribute of a half-length statue of Jupiter, represented either standing or seated, possibly perched upon his hand or standing by his side. It most probably graced a shrine within an important public building, perhaps a predecessor of the Hadrianic-Antonine basilica.

FIG. 9. Four comparative images for the eagle or eagle and serpent: (a) the Silchester bronze eagle (© Reading Museum (Reading Borough Council)); (b) eagle and snake statue from Khirbet et Tannur, Jordan (Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio, USA; © Bridgeman Images); (c) Hercules strangling the serpents as a child, from the Casa dei Vettii, Pompeii c. a.d. 50–79 (fresco) (Pompeii, Italy; © Bridgeman Images); (d) small silver unit of Tincomarus; the reverse depicts a spread eagle and rearing snake (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

Although the eagle associated with Zeus/Jupiter is conventionally identified as the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), it is probable that in this case the eagle is in fact the Short-toed Eagle (Circaetus gallicus) which prefers a warm, dry climate and currently occurs in southern France, Spain, Portugal, North Africa and around the Mediterranean and formerly also in Western Europe (though not Britain) and eastwards to India. This species feeds very largely on reptiles with a preference for snakes, particularly non-venomous species.Footnote 17

There is only one other sculpture known to the author of a freestanding eagle entwined by a serpent from Britain, a fragmentary carving from Somerset originating from either the Keynsham or Somerdale villa.Footnote 18 Although Cunliffe and Fulford recognised the snake, it was left to Anthony Beeson to note that the snake was curled around the eagle.Footnote 19 He saw it as an insular version of two Nabataean statues from Khirbet Tannur and Zaharet el-Bedd in Jordan on the extreme east of the Empire, which differ from the Minories statue in that the eagle in these instances is not about to eat the snake which there represents an aspect of the Nabataean solar deity Zeus Hadad (fig. 9b).Footnote 20 Shortly after the Minories eagle was discovered, Beeson immediately published a further short paper pointing out the similarity of the Minories eagle to those from Jordan and suggesting that, as in those sculptures, the snake was to be regarded as beneficent and that ‘the Minories eagle should be seen as victorious not against evil but against the underworld that the snake represents, and where mortal souls were expected to go after death’.Footnote 21 Here he is surely wrong, at least iconographically, for the Minories eagle is surely about to kill and perhaps eat the villainous-looking, fork-tongued snake, though it is more than likely that the Minories eagle and the later Nabataean variant had a common, probably Augustan, prototype of the later first century b.c. The Minories sculpture would appear far more ‘classical’ as an image, closer in detail and in date to that prototype which takes its place in a long sequence of images of an eagle (the symbol of the chief of the gods, Zeus or Jupiter) in conflict with a serpent (here representing death and evil forces). Csaba Szabó has provided plausibility to such an interpretation by pointing out a dedication to Jupiter from Apulum (Alba Iulia) in Dacia reading:

I(ovi) o(ptimo) m(aximo) / Aur(elius) Marinus / Bas(s)us et Aur(elius) / Castor Polyd/i circumstantes / viderunt numen / aquilae descidis(s)e / monte supra dracone(m) / res validavit / supstrinxit aquila(m) / hi s(upra) s(cripti) aquila(m) de / periculo / liberaverunt / v(oto) l(ibentes) m(erito) p(osuerunt). Footnote 22

With slight emendation po(ntem) Lyd/i for Polyd/i, it might be translated:

To Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Aurelius Marinus Bassus and Aurelius Castor, standing by the bridge of Lydus, saw the numen (‘divine spirit’) of an eagle descend from the mountain upon a draco (serpent). But the strength of the snake was so powerful that it overcame the eagle. Those inscribed above freed the eagle from danger and freely set this up in fulfilment of a vow.Footnote 23

The theme of an eagle overcoming a snake is, in any case, a very ancient one, invariably with the same significance; it is represented, for example, on staters of Elis which controlled the great sanctuary of Olympian Zeus at Olympia, where an eagle is depicted flying with the snake coiled around it but firmly clasped in its beak, and on a silver didrachm of Acragas in Sicily dated to the late fifth century b.c., where it descends upon a writhing serpent.Footnote 24 Dating from the Roman period, but in its fluidity of conception surely in a Hellenistic tradition, is the marble sculpture of an eagle standing upon and overpowering a writhing snake in the Naples Museum datable to the first century b.c. or early first century a.d.Footnote 25 This is very much the type of the image on an intaglio moulded in light blue glass excavated from the site of St Martin-le-Grand, City of London.Footnote 26 Among later second-century glyptic examples of the conflict of eagle with serpent are spirited renderings on a nicolo intaglio in a silver ring with a gold collet found near Wotton-under-Edge and now in Gloucester Museum and a red jasper in the Ashmolean Museum of unknown provenance, both of second-century date and in both of which, as on our sculpture, the snake seems to rear up in order to face its adversary.Footnote 27

The Augustan prototype for the eagle itself is encountered on coins, for instance a bronze quadrans of Augustus c. 10 b.c.Footnote 28 The type is equally familiar from many media including gems, such as an example from Ham Hill, Somerset; sometimes these intaglios are of the ‘eagle-and-standards’ type, exemplified by one from Hod Hill, Dorset — both of the mid-first century a.d.Footnote 29 Of especial interest, as pointed out to me by Guy de la Bédoyère, is the eagle figured upon a painted panel from the House of the Vettii at Pompeii, where the eagle (which is somewhat sculptural in appearance) is perched on the altar overlooking the infant Hercules who is portrayed in the act of strangling two serpents.Footnote 30 Although mythologised, the meaning is surely the same; Jupiter as the eagle, or here through his son Hercules, is portrayed as overcoming the evil forces of the world (fig. 9c).

Of particular interest because they are from the North-Western provinces and from funerary contexts — probably both stood upon second-century burial mounds — are two sandstone statues of eagles with wings partially displayed, standing upon globes and at the same time overpowering serpents; both come from the Treveran region, respectively from Wederath and Siesbach im Hunsrück.Footnote 31 The quality of the Minories sculpture, surely one of the very best pieces of Cotswold sculpture to have survived, must have graced an important tomb.

Among other coin issues depicting eagles overpowering serpents, especially notable in our context is the group of small silver coins struck for the Atrebatic king Tincomarus, who was almost certainly a Roman client, in the late first century b.c. (fig. 9d). These are unique, and without direct Roman prototype, in that the serpent rears up to face the eagle.Footnote 32 Coins struck for two of his successors in southern Britain, Epaticcus and Caratacus, both depict an eagle and a snake, but here the eagles are shown more conventionally as already victorious over it.Footnote 33 The political meaning of these coins is evidently the same as the well-known denarii struck by Julius Caesar which portray an elephant trampling a serpent.Footnote 34 It is self-evident that in general terms the image likewise signifies good overcoming evil, or is a metaphor for the Roman Empire triumphing over barbarism. A similar meaning may be attached to gems which portray a bull above a serpent, such as the example from Tilurnum in Dalmatia in which the bull may represent a legion, probably VII Claudia pia fidelis or VII Augusta, both stationed in Dalmatia in the late first century b.c. and early first century a.d.Footnote 35

The sculpture would appear to have come from a significant tomb, probably of Flavian date or a little later, in the important Minories cemetery. It is plausible, bearing the Atrebatic coins in mind, especially issues of Tincomarus, that it was actually a tomb of a member of his family. Bearing in mind its probable date, there might be a reference to the defeat of the Boudiccan revolt, for Togidubnus, the client king, and presumably the rest of the family were on the Roman side in the conflict.Footnote 36 It is significant that the eagle was laid to rest very carefully in the ditch, which does not suggest any kind of damnatio memoriae.

This is one of the finest and earliest examples of work by a Cotswold sculptor to have come down to us. In quality it bears comparison with the Bath pediment to which allusion has been made above in connection with the representation of feathers. Hayward rightly draws attention to the spirited portrayal of a lion mastering a stag reused in the Camomile Street bastion which, although sadly battered, was clearly a magnificent piece.Footnote 37 A third very impressive animal study is the seated boar from Bath, with its imaginatively patterned pelt and bristling mane, evidently a version of a late Hellenistic or Augustan prototype and most probably late first-century.Footnote 38 Hayward additionally mentions two early tombstones of undoubted excellence, but these seem to me to be rather more formal productions, perhaps to be assigned to a military workshop. Other Cotswold works displaying comparable skill and originality appear to be later in date, among them the statue of Mercury from Uley, Gloucestershire, and the statue believed to portray Apollo Cunomaglos from Bevis Marks, London, both of which are of second-century date.Footnote 39

PETROLOGY OF THE SCULPTURE By K.M.J. Hayward

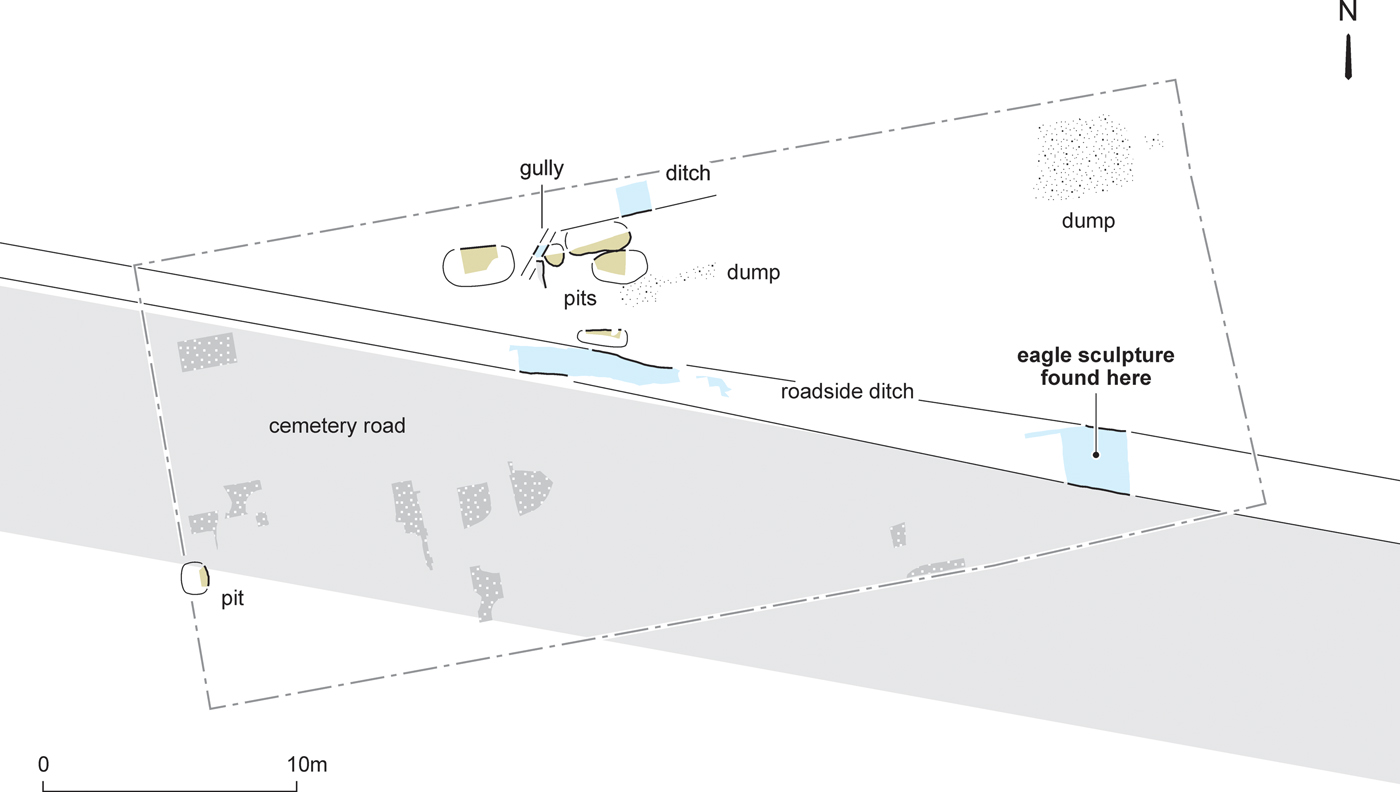

Hand specimen and thin-section petrographic analysis was conducted during 2014Footnote 40 and 2015Footnote 41 in order to determine what type of limestone the eagle was made from and where possible to determine its geological source. Initial visual inspection of the sculpture determined that it was carved from oolitic limestone (shelly) of the south Cotswolds. In hand specimen, the sculptural surface of this hard fine cream-white (2.5 Y8/1) to pale-yellow (2.5 Y8/2) limestone is pitted with small (0.5–1 mm) hollowed ooids together with yellow and grey oyster fragments, and very occasional pink ferroan calcite that belonged to echinoid plates and a small calcite vein or watermark. Together, these features are characteristic of building stones from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) limestone scarp face of the south Cotswolds, specifically between Cirencester and Bath.

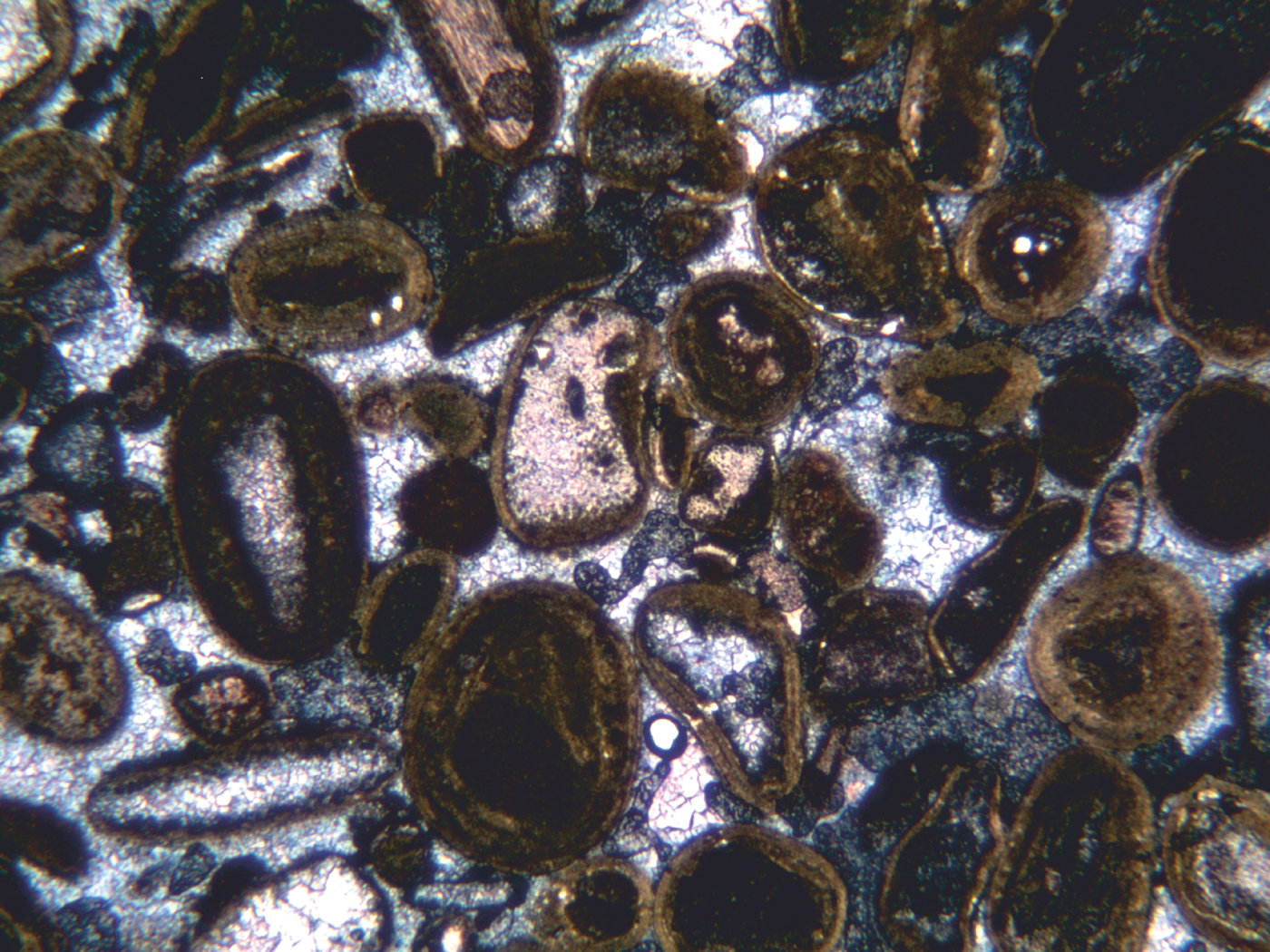

In order to reinforce and refine characterisation, a prepared thin-section (fig. 10) of the limestone was compared with a petrographic reference collection of slides obtained from 150 freestone outcrop samples and early Roman sculptural samples collated from earlier research.Footnote 42

FIG. 10. Photomicrograph showing textural, chemical and palaeontological character of the limestone eagle and serpent <S 1>. Cross Polarised Light. Stained Alizarin Red C and Potassium Hexocynoferrate to pick out variability in colour between ferroan and non-ferroan calcite (field of view 4.8 mm).

A photomicrograph (fig. 10) of the section not only verifies a bio-oosparite limestoneFootnote 43 from a south Cotswold Middle Jurassic source but illustrates some important textural, chemical and palaeontological similarities with samples taken from other examples of religious and funerary sculpture from late first-century London and Cirencester prepared and analysed in this way. In particular, it bears a striking petrological affinity with the rock used in a tombstone of a Flavian-Trajanic officialis Footnote 44 and part of a probable early funerary sculpture depicting a lion overcoming a stag,Footnote 45 both from Arthur Price's 1876 excavationsFootnote 46 near Bastion 10. Similarly, the material is comparable to the Claudio-Neronian Sextus Valerius Genialis auxiliary tombstone from Cirencester.Footnote 47 Like the eagle, these three examples have the same round ooids coated in a thick brown iron oxide matrix, a high blue-ferroan content and fine microcrystalline cement, indicating a common source. The closest match is to Bibury stone, just 6 miles east of Cirencester.

This material is by far the most common stone type in use in late first- to second-century religious and funerary sculpture in London, having been identified in 40 examples,Footnote 48 as well as at sites closer to the source along the Jurassic ridge at Cirencester. What is particularly interesting is how similar its petrology is to a small group of high-quality early funerary monuments from London which were reused nearby in Bastion 10. The golden yellow lion overcoming a stagFootnote 49 is probably only second in terms of its stylistic quality to the eagle and also depicts a similar scene of the ravening power of death. As a group these materials would have adorned the extensive cemeteries to the east of the Roman city of London.

In light of recent research into the petrological and geochemical character and source of mid-first- to early second-century tombstones, architectural fragments and religious sculpture from London,Footnote 50 south-central Britannia,Footnote 51 Germania InferiorFootnote 52 and Aquileia,Footnote 53 we are beginning to understand more about the range of materials in circulation at the time that this sculpture was being carved.Footnote 54 As is the case elsewhere in London and Colchester, the best quality limestones, including golden yellow and white continental and native freestones, were used early on in the province's development. These materials also provided some of the best examples of carving at any time during the province's history. The need to display and mimic white polished marble in high-quality native and continental Jurassic limestone is a theme revisited time and time again in funerary sculpture from London and south-east England. It also shows just how much was known about the extent and detail of the Middle Jurassic Freestone resource so soon after the conquest. The eagle merely represents the finest example, so far, of this group from London.Footnote 55

DISCUSSION

The exquisitely carved statue of the eagle and serpent represents one of the finest and earliest examples of freestoneFootnote 56 sculpture from the London cemeteries and indeed from Roman London.Footnote 57 Its burial in the roadside ditch suggests that the high-status tomb or mausoleum in which it was housed was located on or close to the site. To date, few first-century structures of either wooden or masonry construction have been found.Footnote 58 At the nearby site of 9 St Clare Street a late first- to early second-century inhumation burial may be contemporary with an adjacent stone-lined tomb, though this was undated.Footnote 59 The majority of these structures are dated post-a.d. 120, though the existence of earlier monuments is inferred from architectural and sculptural fragments found residually in second-century contexts, such as the fragments of inscribed marble slabs from 9 St Clare Street.Footnote 60

The burial of funerary and religious sculpture is a phenomenon that is well documented in the London area. A group of stone sculptures including fragments of an altar, a tombstone, three deities and a small stone chest topped with a reclining female figure was recovered from a late Roman well under Southwark cathedral.Footnote 61 The pieces probably derived from a funerary mausoleum and signs of burning on one of the pieces and the possible mid-fourth-century date of their deposition may have been the result of Christian iconoclasm.Footnote 62 An example more pertinent to the Minories eagle comes from the group of oolitic limestone sculpture found within a roadside ditch within a walled cemetery along Great Dover Street in Southwark.Footnote 63 The bearded head, possibly of a river god, and a moulded stone cornice probably adorned one of the funerary monuments which had fallen into disrepair by the third century.Footnote 64 In both these instances, it seems that the monuments which housed them were destroyed or were no longer in use.

The cemetery area in the site and its environs does not appear to have been densely exploited in the first and second centuries. Since the need to release space for new interments does not seem to have been the determining factor, it is not clear why the mausoleum would have been destroyed. Given the condition of the Minories eagle and the fairly short time from when the sculpture was carved to its deposition in the ditch, perhaps an alternative explanation for its burial should be sought. The remains of the mausoleum may await discovery close to the site but ultimately it is not possible to determine the circumstances behind the burial of the sculpture.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL: CONTENTS

For supplementary material for this article please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X17000010.

Note: the Supplementary Material includes online figs 1–14 and Tables 1–2.

section 1: Introduction: the site and its setting D1–2

section 2: First-century a.d. land use and the establishment of the cemetery road c. a.d. 50–100 (Periods 1 and 2) D3–5

section 3: Second-century development of the site c. a.d. 100–60 (Period 3) D5–11

section 4: The late second-century development of the roadside cemetery a.d. 160–400 (Period 4) D11–13

section 5: Discussion D13–14

Bibliography D19

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) would like to thank Scottish Widows Investment Partnership Property Trust and its development partner Endurance Land for generously funding the fieldwork, post-excavation analysis and publication of this site and McAleer & Rushe for their support throughout the fieldwork. We would also like to thank Kathryn Stubbs (Assistant Director Historic Environment, City of London) for assistance and guidance throughout the project. Thanks are also due to Simon Davis the MOLA site Project Officer and the MOLA field team for their efforts on site. MOLA project management was undertaken by Louise Davies and post-excavation management by David Bowsher. Thanks to the following MOLA specialists for their contributions to the post-excavation programme: Charlotte Burn (pottery), Angela Wardle and Michael Marshall (accessioned finds), Ian Betts (building material), Don Walker (osteology), Alan Pipe (faunal remains) and Karen Stewart (botany). The graphics were produced by Sarah Jones and Carlos Lemos and the photography by Andy Chopping. Martin Henig would particularly like to thank Penny Coombe and Francis Grew for discussing the sculpture with him, and also Alan Pipe for suggesting the species of eagle represented here. Gratitude is expressed to Csaba Szabó and Guy de la Bédoyère for providing references which help to elucidate the meaning of the image. Kevin Hayward would like to thank John Jack (SAGES), University of Reading, for the preparation of the petrological section.