Expanding community care for people with mental illness, despite recent concerns (Reference CoidCoid, 1994), remains formal policy in most countries in the world. The initial development of this was through psychiatric policy initiatives (Reference MacmillanMacMillan, 1963), often buttressed by community nurses. However, the major thrust has been the development of multi-disciplinary community mental health teams (CMHTs), which focus assessment and care away from hospital settings and offer a range of interventions tailored to the patients' specific needs (Reference Thornicroft, Becker and HollowayThornicroft et al, 1999). This model of care, despite having a much lower profile than other models of community treatment, particularly assertive community treatment (ACT; Reference Stein and TestStein & Test, 1980; Reference Marshall, Lockwood and GrayMarshall et al, 1999) is now pre-eminent and is the common form of liaison with primary care (Reference Hafner and KlugHafner & Klug, 1982). Despite this de facto recognition, there have been no systematic views on the effectiveness of this approach, an omission that has been corrected by this review.

METHOD

A comprehensive search of the relevant literature was undertaken using electronic databases (Biological Abstracts January 1982-January 1997, EMBASE 1980-1997, Medline 1966-1998 and PsycLIT 1974-1997), SCISEARCH (Science Citation Index), reference lists, searching and personal contact. Full details of the search strategy are detailed elsewhere (Reference Tyrer, Coid and SimmondsTyrer et al, 2000). All randomised and quasi-randomised controlled trials of patients with severe mental illness (not formally defined in most studies, but defined here as “ a psychiatric illness of sufficient severity to require intensive input and regular review”) were included in the search. Using this definition it was assumed that at least half of the patients included would have a psychotic illness. For the purpose of the review, CMHT management was defined as generic care (i.e. care not supplemented by ACT, intensive case management or any other specific model) from a community-based multi-disciplinary team that provides a full range of interventions to adults aged 18-65 years with severe mental illness from a defined catchment area (Reference Thornicroft, Becker and HollowayThornicroft et al, 1999). Standard care was defined as the usual care in the area concerned, provided that this care was not furnished by another community team. In most circumstances this was found to be hospital-based out-patient care.

Procedure

Two of the authors (S.S. and P.T.), both independently and in parallel, studied the abstracts, titles and descriptor terms of all downloaded material from the electronic searches; illegible reports were discarded and the selected original articles were retained. To check the completeness of the electronic search, references cited in all included papers were examined and personal contacts were written to in order to identify any other studies that might be appropriate. The same authors separately evaluated the acquired studies and matched them with the inclusion criteria defined above. Agreement was evaluated by the κ statistic and if overall agreement was less than 0.75 (the level regarded as excellent by Reference Cicchetti and SparrowCicchetti & Sparrow, 1981) then the strategy of the selection was reviewed. Where disagreement occurred, a third reviewer (S.M.) was asked to resolve the dispute. When resolution was not possible, the study was added to those awaiting assessment and the authors were contacted for further data.

Outcome measures and analysis

The outcomes measured included:

-

(a) Death.

-

(b) Acceptability of management (measured by loss to follow-up, i.e. leaving the study early).

-

(c) General (global) improvement.

-

(d) Number of episodes of psychiatric hospitalisation and their duration.

-

(e) Psychopathology and social function.

-

(f) Costs.

Dichotomous and continuous data were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis because evaluation of CMHT management is suitable for a pragmatic approach. Because a wide range of instruments is available to measure outcomes in community care, it was decided to include data from instruments that have been published in a peer review journal in which the validity and reliability had been demonstrated to the satisfaction of referees. Because many of the outcomes of community care are not normally distributed, the following standards were applied to all data before they could be combined in meta-analysis: standard deviations and means of reportage in the paper were obtainable from the authors; and standard deviations when multiplied by 2 were less than the mean (otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of distribution) (Reference Altman and BlandAltman & Bland, 1996; Reference Parmar, Stewart and AltmanParmar et al, 1996).

All normally distributed data were entered into the RevMan software (the Cochrane Collaboration Statistical Program), which allowed data to be combined for meta-analysis. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each study as well as for combined data.

RESULTS

A total of 1200 citations were found using the search strategy, of which 65 were judged to be relevant and full details of the publications were obtained. Of these, five satisfied the inclusion criteria: one from Australia (Reference Hoult, Reynolds and Charbonneau-PowisHoult et al, 1981), one from Canada (Reference Fenton, Tessier and StrueningFenton et al, 1979) and three from London, UK (Reference Merson, Tyrer and OnyettMerson et al, 1992; Burns et al, Reference Burns, Beadsmoore and Bhat1993a ,Reference Burns, Raftery and Beadsmoore b ; Reference Tyrer, Evans and GandhiTyrer et al, 1998) (Table 1). Of the remaining 60, 13 were rejected because they were trials based on specific forms of care such as ACT, 21 because they were not randomised trials, 25 because the interventions did not satisfy the requirements for CMHT treatment and one because the participant did not satisfy all the criteria for the review. The five studies included were reported in 15 journal articles, all published in peer review journals.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Methods | Participants | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia, 1981 | Allocation: sealed, randomly mixed envelopes | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (58), paranoid psychosis (12), mania (10), neurosis (7), other (28) | 1. Project team: multi-disciplinary ‘project’ team, drug treatment, counselling, training in social and basic living skills, family intervention, support and education, 24-h cover (n=60) |

| (CMHT=60; standard=60) | Follow-up: 12 months | Age:<40 years=78 | 2. Standard hospital care and follow-up (n=60) |

| Gender: 55 male. | |||

| History: 90 previous psychiatric contact | |||

| Setting: inner city | |||

| Canada, 1979 | Allocation: randomisation method not described | Diagnosis: schizophrenia, 42%; neurotic, 7.8%; other 30.3% | 1. Home care: multi-disciplinary team, drug and psychotherapy within family, clinical decisions by team consensus, referral to community agencies, 24-h cover (n=78) |

| (CMHT=78; standard=84) | Blinding: unclear, raters ‘independent of teams’ | Age: 85% 15-54 years | 2. Standard hospital treatment: follow-up after discharge (n=84) |

| Follow-up: 2 years | Gender: 65 male | ||

| History: 60% previous psychiatric contact | |||

| Setting: inner city | |||

| London, 1992 | Allocation: randomised, sealed envelopes, stratified by previous contacts with psychiatric services | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (38), mood disorders (32), mood disorders (32), neurotic (25), other (5) | 1. Early intervention service: multi-disciplinary team, open referral, swift response, case manager assigned, no 24-h cover (n=48) |

| (CMHT=48; standard=52) | Duration: 3 months | Age: median 32 years | 2. Standard hospital care, usually out-patient department (n=52) |

| Gender: 40 male | |||

| History: 51% previous psychiatric contact | |||

| Setting: inner city | |||

| London, 1993 | Allocation: randomised, using a random number sequence, before applying inclusion criteria | Diagnosis: psychotic | 1. Community treatment teams: multi-disciplinary community teams, home-based assessment within 2 weeks of referral, joint visits (n=94 ‘entering’ study) |

| (CMHT=150; standard=182) | Follow-up: 12 months | Age: mean=40 years | 2. Standard hospital treatment: usually out-patient department with occasional home visits (n=78 ‘entering’ study) |

| Costs of care | Gender: 75 male | ||

| History: 79 previous psychiatric history | |||

| Setting: inner city | |||

| London, 1998 | Allocation: sealed, randomly mixed envelopes | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (86), bipolar affective disorder (20), depressive disorder (24), other (25) | 1. Community team: multi-disciplinary community-based team, keyworker allocated, care plans, treatment at home/other appropriate setting (n=82) |

| (CMHT=82; standard=73) | Follow-up: 12 months | Age: 16-65 years | 2. Standard hospital treatment: care plans and reviews organised from hospital base (n=55) |

| History:>1 admission in the past 3 years | |||

| Setting: urban |

Deaths from all causes

Four out of the five studies had fewer deaths in the standard care group. Although the small numbers in individual studies seldom provoked comment, collectively they amounted to a difference that was significant (Fig. 1): 1.7% of people treated by CMHTs died during the course of the studies, compared with 3.8% of the control group. This difference was even greater when deaths by suicide or suspicious circumstances were compared (OR=0.32; CI 0.09-1.12). Deaths due to physical causes also were less frequent in the CMHT group, but not to a marked extent (OR=0.63; CI 0.22-1.82).

Fig. 1 Comparison of community mental health team (CMHT) management and standard care with respect to death as an outcome. When the boundaries of the diamond-shaped lozenge do not cross the vertical line, there are significant differences between the two models of care.

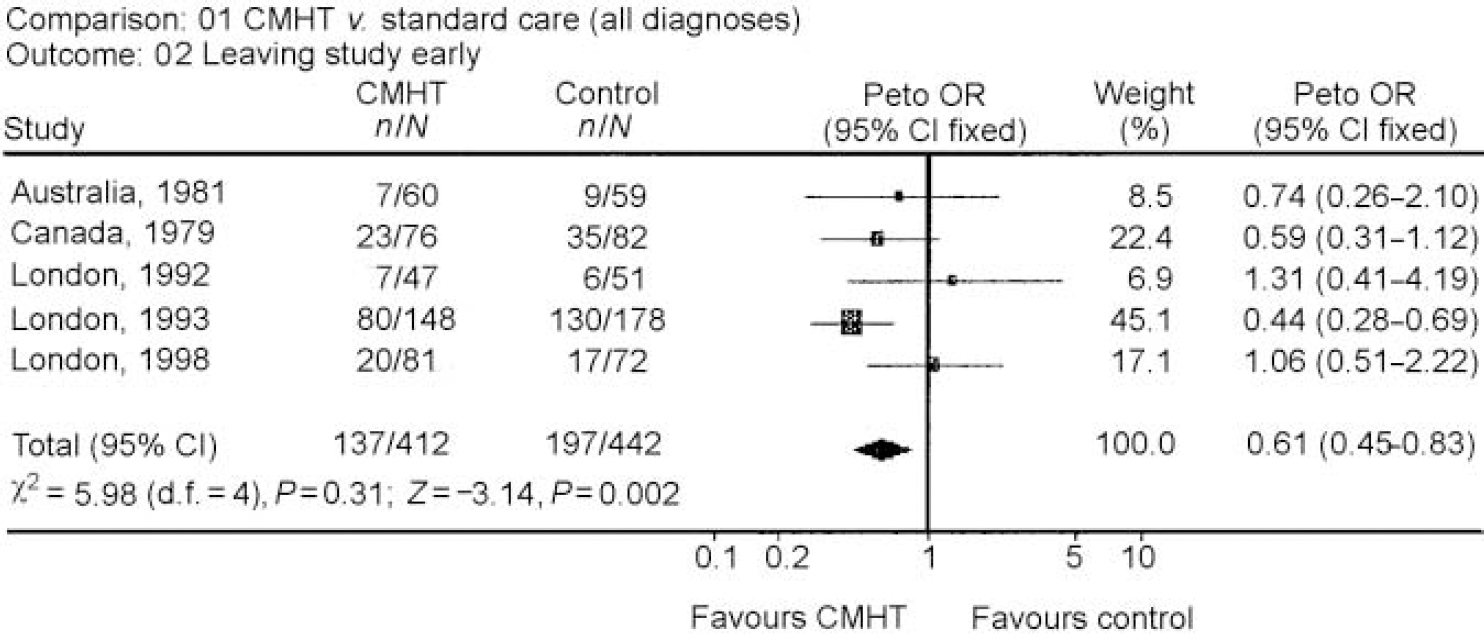

Leaving the study early

All of the five studies provided data. Results relating to the 854 people showed that a significantly smaller proportion (33%) dropped out of CMHT management early compared with 45% in those receiving standard care (OR=0.61, CI 0.45-0.83) (Fig. 2). Individuals dying of natural causes were excluded from this outcome measure.

Fig. 2 Comparison of those leaving the study early (loss to follow-up) with community mental health team (CHMT) management and standard care.

Hospitalisation

The mean duration of psychiatric hospital admissions showed that less time was spent in hospital following CMHT management (Table 2) but the data were not homogeneous (χ2=21.3, d.f.=3, P < 0.001). This is mainly because one study (Reference Hoult and ReynoldsHoult & Reynolds, 1984) randomised patients at the point of admission to hospital and, as there were no special provisions to prevent admissions in the standard care group, 56 of the 58 patients concerned were admitted. However, the duration of hospital treatment was also significantly less in patients from CMHT management in other settings and, despite the skewed data, it is reasonable to conclude that such management reduces hospital stay.

Table 2 Comparison of community mental health and standard teams in use of psychiatric beds

| Duration of hospital care (mean bed days) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Community mental health team | Standard |

| Australia, 1981 | 8.4 (s.d. not available) | 53.5 (s.d. not available) |

| Canada, 1979 | 14.5 (s.d.=35.7) | 41.7 (s.d.=50.3) |

| London, 19921 | 1.2 (s.d.=3.6) | 9.3 (s.d.=20.1) |

| London, 1993 | No data available | No data available |

| London, 1998 | 27.9 (s.d.=53.9) | 28.7 (s.d.=49.3) |

Clinical psychopathology and social functioning

The results of the five studies are shown in Table 3. Because studies used different rating scales and these showed larger than acceptable standard deviations, it was not possible to combine these in a meta-analysis. However, the data taken separately suggest no convincing differences in favour of either form of management for clinical symptoms or social functioning.

Table 3 Mean psychiatric symptoms and social function at end of studies (ranging from 3 to 12 months)

Costs

In all five studies the total cost of care was less for those treated with CHMT management (Table 4). Because of the gross skewing of data it was not possible to use meta-analysis to combine the data, but all studies reported lower costs with CMHT management, with differences of between 12 and 53% across the five studies. Because these differences are substantial, it is fair to conclude that the published studies showed clear evidence of CMHT management being cheaper than standard care, even allowing for the limitations of the data across a span of 17 years.

Table 4 Mean costs of care over duration of studies ranging from 3 to 12 months (markedly skewed data cannot be combined by meta-analysis)

| Study | Mean cost (0-12 months)1 | Percentage mean saving with CMHT | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMHT | Standard | |||

| Australia, 1981 | £ 2225 | £ 2845 | 22 | Reference Hoult and ReynoldsHoult & Reynolds, 1984 |

| Canada, 1979 | £ 1468 | £ 3068 | 52 | Reference Fenton, Tessier and StrueningFenton et al, 1979 |

| London, 1992 | £ 1167 | £ 2500 | 53 | Reference Merson, Tyrer and CarlenMerson et al, 1996 |

| London, 1993 | £ 1429 | £ 1696 | 16 | Reference Burns, Raftery and BeadsmooreBurns et al, 1993b |

| London, 1998 | £ 16 765 | £ 19 125 | 12 | Reference Tyrer, Evans and GandhiTyrer et al, 1998 |

DISCUSSION

Benefits of CMHT management

The results of this review show that CMHT management is effective in comparison with standard care with respect to acceptance of treatment, reduction of hospital admissions, maintaining care, reducing death by suicide and suspicious circumstances and in reducing costs. Although changes in psychopathology showed no difference between CMHT management and standard care, there are no outcomes for which standard care is superior to care delivery from a CMHT.

Before discussing the implications of these positive conclusions, it needs to be acknowledged that the studies do not necessarily reflect the exercise of both of these models of care in practice. The Australian study had a specific research focus, and in all studies there was a level of enthusiasm for community care in the mental health teams that could well be greater than the average for such services. However, there is no evidence that enthusiasm alone has any significant impact on the care of patients with severe mental illness, and the inclusion of patients in any research study tends to be associated with a Hawthorne effect that applies across all treatment arms. In recent years the practices employed by the CMHTs in this study have been more widely spread and are generally becoming the norm.

Effects on psychiatric bed use

The evidence that duration of psychiatric care is reduced with CMHT management is strong but not overwhelming. The figures lie between those studies, mainly published in the USA, that suggest that the ACT model has a major impact on reducing admissions (Reference Marshall, Lockwood and GrayMarshall et al, 1999) and formal case management (allocation to a formal process of regular assessment and review), which creates the opposite effect with greater hospital admissions (Reference Tyrer, Morgan and Van HornTyrer et al, 1995; Reference Marshall, Gray and LockwoodMarshall et al, 1998). The results also need to be tempered with some caution. The findings apply only when sufficient beds are available for admission. When there is a significant shortage of beds, as in the later study (Reference Tyrer, Evans and GandhiTyrer et al, 1998), admissions were still reduced but the duration of hospital admissions may become longer because of the disruption created by transfer of patients to distant hospitals. The lower rate of drop-out from care with CHMT management supports the findings of case management (Reference Marshall, Gray and LockwoodMarshall et al, 1998) and assertive approaches (Reference Marshall, Lockwood and GrayMarshall et al, 1999) and is perhaps partly expected, because one of the main functions of such teams is to maintain contact with patients and to see them in settings that are most appropriate for their care, including home treatment.

Cost-effectiveness and reduced deaths

The lower use of in-patient services is probably the main reason for the reduced cost of CMHT treatment (Table 4). Indeed, the savings here are substantial because a very large amount of money is saved by preventing relatively few admissions and it is perhaps this reason that has led to much of the savings created by the closure of mental hospitals not being transferred to acute services, where they appear to be most needed (Reference Lelliott, Sims and WingLelliott et al, 1993). The finding that CMHT management may reduce suicide and deaths under suspicious circumstances is of particular interest in view of the perceived failings of community care in some parts of the world, in particular the UK, where its failure has been stated clearly by government (Department of Health, 1998). Largely because of incorrect and tendentious reporting by the media, the policy of ‘care in the community’ for people with severe mental illness has become associated in the public mind with professional neglect and increased rates of homicide and suicide. It appears from our data that good CMHTs have the opposite effect and that if we are able to provide adequate resources then these serious adverse consequences arise rather less often than in other settings.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Community mental health team (CMHT) management is a cost-effective method of delivering care for people with severe mental illness because, compared with non-team care, it delivers similar clinical outcomes at reduced cost.

-

▪ Deaths from suicide and suspicious circumstances are reduced by CMHT management compared with standard hospital-oriented care and this should be taken into account when attribution of blame is made for such tragic events in community settings.

-

▪ Loss to care through drop-out is less with CMHT management then with standard care, probably because it is more acceptable to patients, and is therefore likely to grow further in importance.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The numbers of deaths in the studies was small and further studies are needed to determine whether this finding is robust.

-

▪ The review did not address the therapeutic activity of the CMHTs and endorsement of this approach is clearly dependent on sufficient skills being available within the teams to provide optimal interventions.

-

▪ Two of the reviewed studies were aimed specifically at avoiding hospital admission and so the findings of reduced bed use need to be tempered with caution.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Information presented here has been available since 1997 in the Cochrane Library, in a review entitled ‘Community mental health teams (CMHTs) for people with severe mental illnesses and disordered personality’. We thank colleagues in the Cochrane Library, particularly Clive Adams and Nancy Owens, for their help in this review. A grant was received from the North Thames R&D Responsive Funding Group.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.