INTRODUCTION

Recent years have witnessed the rise of political forces questioning various aspects of democratic governance, opposing and undermining the liberal democratic order previously taken for granted. Governments of countries like Hungary and Poland have limited the autonomy of courts, undermined independent media, adjusted electoral rules to their advantage, and sought ways of insulating themselves from political opposition and critique. Hungary’s long-term prime minister, Victor Orbán, has explicitly spoken out in favor of “illiberal” democracy. A vibrant debate in the academic literature has addressed this democratic backsliding by focusing on post-communist experiences of eastern Europe, especially democratic transition, accession to the European Union (EU), and the associated economic strains (Bohle and Greskovits Reference Bohle and Greskovits2012; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2019). These arguments point to the role of democratic values, institutional contexts, economic development, and political agency of domestic actors. They suggest that democratization occurred halfheartedly, and in order to satisfy the accession criteria of the EU (Grzymala-Busse and Innes Reference Grzymala-Busse and Innes2003). Once accession was completed, eastern Europe was released from EU conditionality to chart its own course, and domestic elites were free to pursue their political goals unscrupulously (Bozoki and Simon Reference Bozoki, Simon and Ramet2019; Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018; Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018; Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020). This account, however, pays little attention to ethnicity.

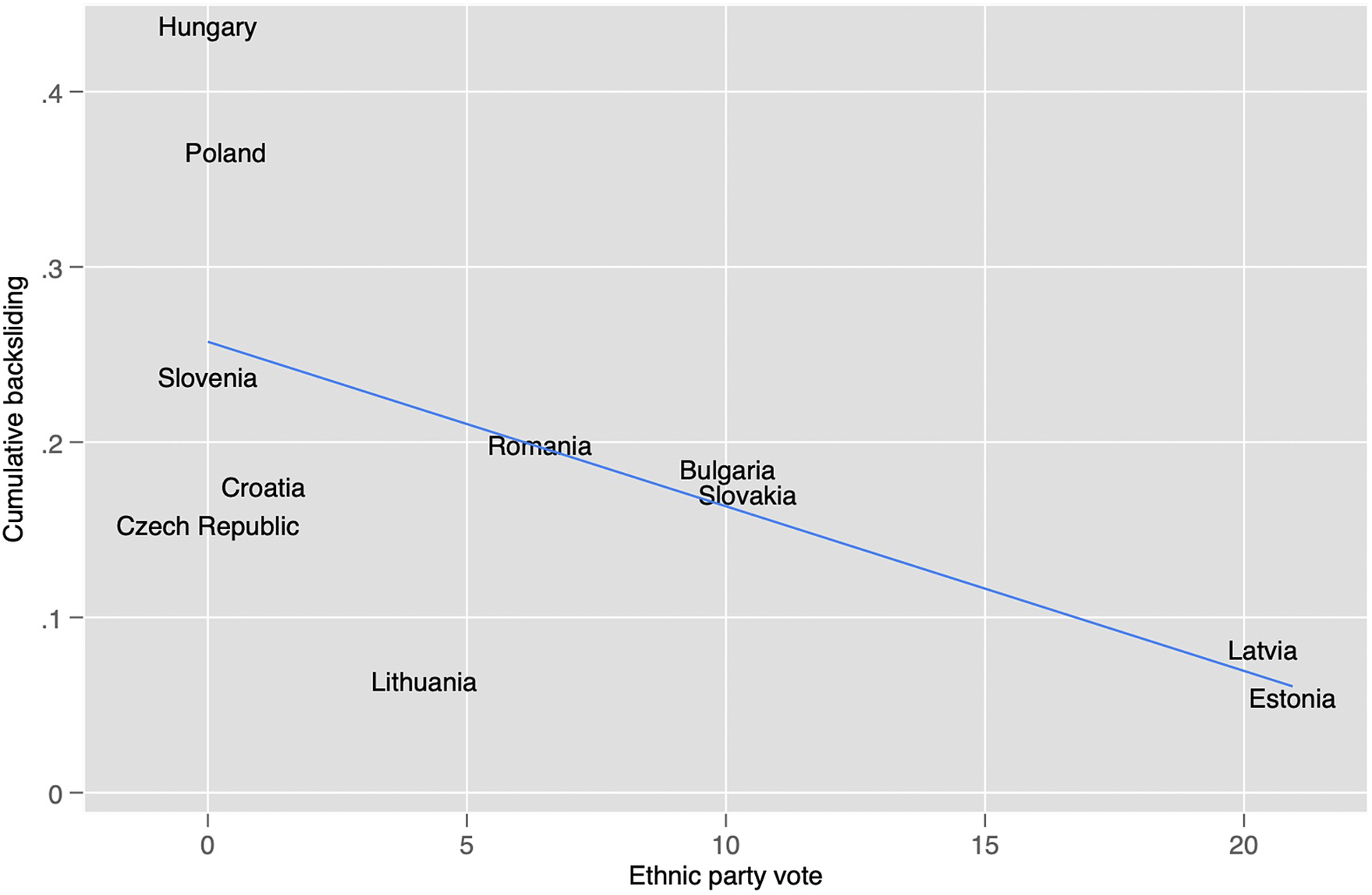

This article departs from a striking observation that backsliding occurs most prominently in societies without politically organized ethnic minorities. The most widely cited cases of democratic regression, Hungary and Poland, do not have significant, politically organized ethnic minorities. While these countries were the frontrunners of democratic transition and consolidation in the 1990s, today they are singled out as the leaders of democratic demise. Eastern Europe contains striking variance in the presence of ethnic mobilization. Countries such as the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary lack significant, politically organized minorities, whereas Estonia and Latvia contain significant ethnic minorities mobilized by parties seeking their vote. Figure 1 shows a strong negative correlation (

![]() $ r=-0.624 $

) between ethnic party vote share and democratic backsliding. Why is this the case?

$ r=-0.624 $

) between ethnic party vote share and democratic backsliding. Why is this the case?

Figure 1. Backsliding and Ethnic Mobilization

Note: Cumulative backsliding is the sum of all annual democratic regressions (negative differences) between 1990 and 2020 (V-Dem liberal democracy data).

This article argues that the presence of significant, politically organized ethnic minorities helps explain the diversity of democratic paths in eastern Europe over the past three decades. In societies where politically organized ethnic minorities play a role in the domestic political process, democratic institutions and practices tend to have stronger coalitions of pro-democratic supporters and remain better protected than in countries without politically organized ethnic minorities.

This is because ethnic groups without credible prospects of creating their own state or joining an ethnic kin state face a dual predicament. First, permanent ethnic minorities are confined to a state in which they form a minority and from which they cannot leave. Second, they share a distinct interest in preserving their group identity—generally rooted in culture, language, or religious practice. In this position, organized permanent minorities seek protection from the tyranny of the majority by aspiring for political rights and liberties. Ethnic minorities thus provide numerous, socially rooted electorates seeking rights and liberties. When mobilized, their influence is system shaping. Political parties seeking minority support that are able to successfully contest elections shape political competition, engaging issues of rights and liberties.

This article focuses on the role of three key political actors: mobilized ethnic minorities, constitutionally liberal parties actively seeking political pluralism, and illiberal parties asserting the primacy of ethnically defined dominant groups. In doing so, the article underlines the presence of a countervailing phenomenon of ethnic mobilization which induces support for rights and liberties among minorities and sections of the majority. Ethnic minority representatives search for cooperation with sympathetic majority political forces, bolstering constitutional liberal and moderate mainstream parties, inclining them toward constitutional liberalism, and generally fortifying the liberal pole of politics. This strengthened liberal pole is better able to counterbalance illiberals who are the dominant source of democratic backsliding everywhere. The presence of politically organized ethnic interests makes it harder for illiberals to gain monopolistic positions of power, and degrade democratic institutions and practices. In countries without ethnic mobilization, illiberals focus on other cultural issues related to, for example, religion and gender, national history, or migration. However, in the absence of politically mobilized ethnic minorities, the liberal opponents of illiberal forces are likely to be less socially rooted, less numerous, less focused of civil rights and liberties, and thus less able to constrain democratic backsliding.

The treatment of east European democratic transition and backsliding points to the particular ethnic makeup of these societies, but in contradictory ways. On the one hand, scholars consider the deleterious effect of historical ethnic heterogeneity inherited by eastern European countries, inducing problematic interactions between nationalizing states, ethnic minorities, and ethnic kin states (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996; Csergö and Goldgeier Reference Csergő and Goldgeier2013; Stroschein Reference Stroschein2012; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2010). More recent studies of backsliding highlight ethnicity as a destabilizing source of communal conflict undermining democracy (e.g., Berman Reference Berman2019; Kolev Reference Kolev2020; Shoup Reference Shoup2018). On the other hand, scholars point to eastern Europe’s lack of experience with ethnic diversity, given that these are traditionally countries of emigration, not immigration, as a source of anti-democratic sentiments (Krastev Reference Krastev2018; Rupnik Reference Rupnik2016). While it is true that eastern Europe lacks (particularly non-European) immigration, it is not true that eastern Europe uniformly lacks experience with ethnic diversity.

This article contributes to our understanding of ethnic mobilization as part of more complex causal patterns. First, ethnic mobilization emboldens nationalist backlash (e.g., Bustikova Reference Bustikova2019; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005) while simultaneously leading to coalitions between ethnic minorities and liberal actors. Although past works note such coalitions, they do not identify their theoretical implications. This article demonstrates the democratic potential of such coalitions, and thus the countervailing effect of ethnic mobilization and accommodation. Second, by focusing on constitutional liberalism, rather than liberalism generally, the article underlines its multidimensionality, whereby some cultural conservatives can be constitutional liberals. Ultimately, the article demonstrates that, while democratic development can be achieved in distinct ways, mobilized ethnic minorities provide particular democratic reinforcement due to their socially rooted political organizations in existential search for rights and liberties.

The article’s analyses focus on 11 eastern EU member states—an ideal testing ground for two reasons. First, their comparable experience of democratic transition and EU accession process ensure unit homogeneity. Second, their wide-ranging levels of ethnic mobilization provide variance on the key predictor. The finding that ethnic minority engagement in politics leads to better democratic outcomes in a region where ethnic politics is seen as broadly detrimental to democracy, is an important contribution with important theoretical implications.

The article first reviews the study of democratic transition and backsliding in eastern Europe. It then builds the argument about the role of ethnic minority mobilization as a bulwark in democratic politics. After discussing the methods, the article tests its theoretical propositions using statistical inference on quantitative data from 11 eastern EU members. To further highlight the validity of its argument and explore the mechanisms, the penultimate section carries out a qualitative comparison of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The final section serves as a conclusion.

UNDERSTANDING DEMOCRATIC BACKSLIDING

Democratic backsliding is the undoing of liberal democracy, a “deliberate” (Sitter and Bakke Reference Sitter and Bakke2022, 26), “state-led debilitation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy” (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016, 5). This article understands democratic backsliding as the formal decline of liberal democratic institutions and practices. That includes the dismantling of counter-majoritarian institutions, such as democratic checks and balances, particularly the judicial system, as well as the degradation of free and fair political competition rooted in equitable access to independent information (see Bakke and Sitter Reference Bakke and Sitter2022; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2019).

The study of democratic backsliding reflects the study of democratization, seeking to understand how relatively consolidated democracies could erode. The initial explanation of backsliding turned to reassess the process of democratic transition. The transitional tumult of the 1990s produced some initial success stories, particularly the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary, who managed to establish democratic constitutional orders, more or less stable party systems, and achieved democratic rotation in office relatively early. Other countries struggled in their transition, as elites deliberately undermined political competition, leading to “defective democracies” (Merkel Reference Merkel2004), or “competitive authoritarianism” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002). A number of scholars (e.g., Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2018; Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016; Innes Reference Innes2014) thus question the concept of backsliding, suggesting that liberal democracy had a tentative foothold in eastern Europe. Democratic achievements were predominantly institutional, and, given problematic communist legacies (Pop-Eleches and Tucker Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2017), illiberalism remained entrenched in the political mainstream (Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016). Backsliding thus was not so much a turn away from liberal democracy, as a realization of the lack of truly liberal democratic principles and practices underpinning politics in the region. Finally, some scholars consider backsliding as a natural part of democratic consolidation. Berman (Reference Berman2019, 384), drawing on European history, emphasizes “that achieving consolidated liberal democracy easily or quickly is extremely unusual,” and often proceeds through fits, starts, and failures. Bochsler and Juon (Reference Bochsler and Juon2020) provide empirical evidence showing mixed democratic outcomes, questioning the assumption of uniform democratic decline in eastern Europe.

The transition process overlapped with the process of accession to the EU. Through its conditionality, requiring above all the rule of law and protection of rights, the EU was able to exert significant pressure while providing a rallying point for democratic forces in the region (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005). The EU accession process, however, carried a heavy burden of legal and regulatory conformity which acceding countries simply needed to translate into national law. As Grzymala-Busse and Innes (Reference Grzymala-Busse and Innes2003) argue, this imperative foreclosed much public debate and ideological development in the region, leading instead to technocratic political competition and emptying out of politics (cf. Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2007; Innes Reference Innes2002; Rupnik Reference Rupnik2007; Rupnik and Zielonka Reference Rupnik and Zielonka2013; Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2014). Some scholars suggest that this process simply covered up significant illiberal tendencies that were continuously present even in mainstream politics (Cianetti, Dawson, and Hanley Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2018; Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2016). These were then able to resurface after the region attained EU membership and EU conditionality lost its effect, resulting in democratic backsliding, which is further reinforced by EU political processes and funding (Keleman Reference Kelemen2020).

The transition literature also highlights the role of socioeconomic frustrations as sources of democratic malaise (Bohle and Greskovits Reference Bohle and Greskovits2007; Reference Bohle and Greskovits2009; cf. Orenstein Reference Orenstein2001). Bohle and Greskovits (Reference Bohle and Greskovits2007, 455) suggest that “[p]ersistent deep social gaps combined with grave ideological and political divisions within elites prepared the ground for the rise of illiberals….”

The transition literature engages the question of ethnic politics and democracy, generally viewing ethnic heterogeneity as a problematic endowment, complicating democratic transition, and potentially fueling democratic decay. Ethnic identity provides group bonds (Hale Reference Hale2008) stabilizing political choice and behavior (Birnir Reference Birnir2007). This choice is, nonetheless, rooted in co-ethnic particularism, and is expected to detract from programmatic politics (Chandra Reference Chandra2004; Csergö and Regelmann Reference Csergő and Regelmann2017; Long and Gibson Reference Long and Gibson2015). Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1996) theorizes the “triadic nexus” between nationalizing states, ethnic minorities on their territory, and ethnic kin states, seeking to influence their neighbors. The interaction between these actors hinders democratic development and sustenance. While ethnic majority elites can scapegoat minorities to mobilize their support, and distract attention from other political issues (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005), politicians from ethnic kin states engage with extraterritorial minorities to further their own nation-building strategies (Csergö and Goldgeier Reference Csergő and Goldgeier2013). This engagement can provide ethnic minorities with resources, political, and cultural support (Jenne Reference Jenne2007; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2016; Reference Waterbury2021). Simultaneously, kin state engagement splits the minority’s loyalties between the kin state and the state of residence (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2020), threatening the minority’s unity (Jenne Reference Jenne2007), and undermining the possibility of minority–majority bargaining and cooperation within the state of residence (Kiss, Toró, and Székely Reference Kiss, Toró, Székely, Kiss, Székely, Toró, Bárdi and Horváth2018), ultimately compromising the agency and legitimacy of the minority leadership (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2021). Cianetti (Reference Cianetti2018) argues that Estonia and Latvia suffer from democratic hollowness rooted in ethnic majority technocracy and minority exclusion. Stroschein (Reference Stroschein2012, 237), however, also demonstrates that accommodation of minorities can lead to acceptance of “democratic institutions in which they are permanent minorities.”

Most recent scholarship highlights the central role of agency in democratic erosion (Bozoki and Simon Reference Bozoki, Simon and Ramet2019; Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2021). Democratic backsliding is primarily associated with “the weakening loyalty of political elites to democratic principles” (Greskovits Reference Greskovits2015, 28), and growing political polarization rooted in cultural conflict (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2019). While backsliding can occur in the context of democratic transition and economic strife, it is carried out as an act—rhetorical, political, or legal—by political actors. These actors seek to establish “the institutionalization of hierarchical [and] state-dependent structures” that are controlled by the executive (Enyedi Reference Enyedi2016, 21). They build extensive clientelistic networks (Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018), with the aim of executive state and media capture (Sata and Karolewski Reference Sata and Karolewski2020; Surowiec and Štětka Reference Surowiec and Štětka2020). While elite perpetrators of backsliding differ in their level of cultural conservatism, they harness national, ethnic majority-focused populist imagery, engaging in what Jenne (Reference Jenne2018) refers to as “ethnopopulism” (cf. Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2019; Palonen Reference Palonen2018; Plattner Reference Plattner2019; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020). Vachudova (Reference Vachudova2020) stresses the flexible nature of ethnopopulism where the ingroup, “the people,” need not be defined solely as a nation, and similarly the enemy outgroup can adjust to new events. This is very similar to the illiberal actors that constrained democratic transition in some countries in the early-mid 1990s (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005). Ultimately, while divergent in their views of the economic and cultural aspects of liberalism, the elites and organizations undermining transition and fueling democratic backsliding uniformly oppose liberalism as a constitutional principle, as a correction of democracy seeking to avoid the tyranny of the majority.

This article follows Vachudova (Reference Vachudova2005) and uses the term “illiberal” to denote political parties that oppose liberalism as a constitutional principle—actors that undermine political pluralism by advocating majority rule rooted in flexible often ethnocentric conceptions of “the people” as the ultimate source of political legitimacy. This broader category includes contemporary “ethnopopulists,” as well as other anti-pluralist forces, such as the radical right or unreformed communists. The opposite of illiberals are constitutional liberals who actively seek political pluralism that accords political rights and civil liberties to all individuals, and pursue institutional checks and balances as well as the rule of law in order to constrain majority rule. While constitutional liberals are consistently active promotors of democratic principles, they may hold culturally conservative outlooks, as, for example, the Christian democratic SDKU coalition in Slovakia. Finally, ethnic parties are parties that explicitly or implicitly cater to particular ethnic groups that make up a majority of their electorate. It is important to note that this categorization leaves a significant residual category of moderate political parties that do not cater to ethnic minority interests, and are neither active champions of constitutional liberalism, nor of illiberal anti-pluralism, but may cooperate with either. The following section considers how ethnic mobilization can improve democratic development.

DEMOCRACY AND ETHNIC MOBILIZATION

One of the core balancing acts of democracy is finding an equilibrium between democratic majority rule and minority rights (Dahl Reference Dahl1956). The main constitutional principles of liberal democracy are thus counter-majoritarian arrangements limiting the potentially corrosive effects of democratic majority rule. No one has keener understanding—even if a latent one—of the tyranny of the majority than members of permanent minority groups. Permanent minorities face two important concerns. First, by definition of being permanent, they are “stuck” in a society in which they form a minority and cannot leave. Second, to the extent that they have coherent interests, these are likely to form continuous minority opinion, easily trumped by majority rule.

Ethnic groups often form such permanent minorities. They are permanent in the sense that their successful secession or irredenta is quite unlikely in most contemporary political contexts.Footnote 1 Furthermore, they share significant common political interests centering around their ability to preserve their group identity, often rooted in language, religious practice, or culture (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1995, 93). These aims set them permanently apart from the political interests of the majority. Consequently, minority concern for self-preservation through minority rights, and the necessary protection from the tyranny of the majority make ethnic minorities potential defendants of liberal democracy.Footnote 2

This is counter to most expectations. Ethnic minorities and ethnic politics are generally seen as problematic for democracy. Ethnicity, as an ascriptive characteristic, is viewed as a source of particularistic extremism, conflict, and democratic instability (e.g., Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Hug, Schädel and Wucherpfennig2015; Easterly and Levine Reference Easterly and Levine1997; Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin1996; Wucherpfennig, Hunziker, and Cederman Reference Wucherpfennig, Hunziker and Cederman2015). Even if ethnicity stabilizes political choice by leading group members to support their co-ethnics (Birnir Reference Birnir2007; Chandra Reference Chandra2004; Csergö and Regelmann Reference Csergő and Regelmann2017), it produces particularistic politics of belonging that detract from democratic, interest-based politics (Lynch and Crawford Reference Lynch and Crawford2011). While Berman (Reference Berman2019, 387) asserts that “[c]ommunal conflict …endemic in newly independent East-Central European countries, contribut[ed] to illiberalism and the rapid collapse of democracy” in the interwar period, many observers see contemporary ethnic heterogeneity in the region similarly detrimental to democratic construction (e.g., Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Offe Reference Offe1998). Broader literature studying ethnic heterogeneity and democratic outcomes largely finds no or negative effects of heterogeneity on democracy (Akdede Reference Akdede2010; Barro Reference Barro1999; Fish and Brooks Reference Fish and Brooks2004; Fish and Kroenig Reference Fish and Kroenig2006; Jensen and Skaaning Reference Jensen and Skaaning2012).

This article, however, argues that politically organized ethnic minorities may infuse politics not with group particularism, but with liberal democratic aims. When ethnic minorities cannot ensure their group survival through becoming a majority—by gaining independence or joining an ethnic kin state—they seek to protect their group identity through rights and civil liberties characteristic of a liberal democratic order. Under the conditions of permanent minority status, dominant ethnic representatives, whether they be explicitly ethnic parties, or other political formations seeking minority support, strive for cooperation with segments of the majority, and for the development of ethnically egalitarian policies. This political effort seeking equality, rights, civil liberties, and counter-majoritarian institutions bolsters constitutional liberal and moderate parties, restrains illiberals, the main actors of democratic backsliding, and reinforces liberal democracy.

Crucially, however, this effort is not inherent to ethnic minorities. It is undermined when circumstances present the possibility of ensuring group survival and support through other means. When ethnic groups have a realistic possibility of ending their minority status, they are likely to prefer it over remaining a minority (Meadwell Reference Meadwell, Paul and Hall1999). Certain group characteristics, particularly religious identity, weaken ethnic minority representatives’ commitment to liberal democracy. As I develop elsewhere (Rovny Reference Rovny2014), religious basis of ethnic group identity provide a conservatizing cross-pressure, attenuating liberal political aims rooted in minority status.

The presence of mobilized ethnic minorities provides a double-sided opportunity for ethnic majority political actors. On the one hand, illiberal actors may seek to garner support and shift political attention by scapegoating minorities (Bustikova Reference Bustikova2019; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005), whereas other majority actors may strive to systematically exclude ethnic minorities from politics (Cianetti Reference Cianetti2019; Schulze Reference Schulze2018). On the other hand, the presence of politically organized ethnic minorities provides an opportunity for liberal democracy in two elementary ways.

First, politically significant ethnic minorities, capable of mobilizing and organizing political forces able to successfully contest elections, strive for political representation either via multiethnic parties, or via specific ethnic minority organizations. They enrich politics with representatives seeking rights and civil liberties (Evans and Need Reference Evans and Need2002). Second, the presence of significant ethnic minorities increases political contestation over rights and liberties in general, also among majority populations. This polarization thus produces two countervailing forces. On the one hand, it emboldens an illiberal backlash among parts of the majority (Bustikova Reference Bustikova2019), and it simultaneously shores up some support for constitutionally liberal democratic politics among other majority voters on the other.

Consequently, the presence of politically organized ethnic minorities alters the political dynamics (Rovny Reference Rovny2014). Questions of rights become more hotly contested, strengthening illiberal opponents, as well as liberal proponents, while creating additional political opportunities for moderates. Majority mainstream parties face a broader set of potential partners, whereas parties seeking to represent ethnic minorities reinforce the search for rights and liberties. In societies, where ethnic minorities have been excluded from political competition, a segment of majority political actors faces a political opportunity in integrating, organizing, and mobilizing these minorities.Footnote 3 In short, the presence of mobilized ethnic minorities makes constitutional liberalism a more salient option in politics.

This systemic liberal brace is absent in societies lacking organized ethnic minorities. Illiberals in countries without organized ethnic minorities mobilize around other issues, such as religion and questions of gender equality in the case of Poland, or national history and migration in the case of Hungary. Indeed, the migration wave which passed through eastern Europe in 2015 provided much rhetorical fodder for illiberals even in countries with limited immigration and low ethnic diversity. However, countries without politically significant ethnic minorities do not possess structured electoral groups united by an existential need for equality, rights, and civil liberties. More homogeneous societies are less polarized over questions of democratic rights, and are thus less likely to develop significant political forces ready to defend them. Without organized ethnic minority parties seeking rights and liberties, countries lack the structural boost for their moderate and liberal forces. Here, moderates lack potential pro-rights partners, and liberal forces are less willing and able to neutralize illiberals, and prevent democratic backsliding.

Let us consider the specific mechanisms. Organized ethnic interests bolster the constitutionally liberal pole of politics. Ethnic parties are particularly useful partners for two reasons. First, ethnic minorities tend to form relatively cohesive electorates that consistently support their political representatives (Birnir Reference Birnir2007) and are less likely to punish them for government participation (Aha Reference Aha2021). To the extent that ethnic parties mobilize a numerically significant part of the population, the electoral support this represents may be crucial for election outcomes and potential government formation.Footnote 4 Second, ethnic minority parties are easy government partners who focus on their aims of minority rights, with often weaker economic agenda, and without being an electoral threat to mainstream government parties (Aha Reference Aha2019; Zuber and Szöcsik Reference Zuber and Szöcsik2015). Third, given their coalition flexibility, ethnic parties striving for rights and liberties can act as a liberal corrective for both left- and right-wing moderate parties. As such, mobilized ethnic minorities can lend significant electoral support to constitutional liberals and aid moderation of mainstream political actors across the political spectrum, becoming a systemic buttress of liberal constitutional principles.

The presence of mobilized ethnic minorities thus provides a dual boost to constitutionally liberal parties. It furnishes relatively easy partners in the form of ethnic minority representatives. Furthermore, through increased polarization of majority electorates over questions of rights, it supplies some liberally inclined majority voters, opposed to illiberals.

H1: The presence of mobilized ethnic minorities improves the electoral chances of constitutional liberals.

Greater electoral strength of constitutional liberals provides important democratic correctives. First, the presence of electorally more viable constitutionally liberal parties is likely to translate into their higher parliamentary representation, providing stronger coalition partners for mainstream parties, reducing their political reliance on illiberals. Second, an increased presence of constitutional liberal voices in parliament and in the polity as a whole is likely to have a nonnegligible impact on political debate, limiting the normalization of anti-pluralist themes.

The most significant source of democratic backsliding is the active erosion of democratic institutions, practices, and norms by illiberal forces (Palonen Reference Palonen2018; Plattner Reference Plattner2019; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020). The presence of politically mobilized ethnic minorities blunts their ability to do so. Ethnic mobilization leads to political polarization over rights and liberties. This strengthens illiberal appeal among some parts of the majority, engendering a radical backlash (Bustikova Reference Bustikova2019). Simultaneously, illiberals face greater limits in societies with politically mobilized ethnic minorities. Members of ethnic minorities are naturally highly unlikely to support majority illiberals, which removes a segment of their potential electoral support. Furthermore, ethnic mobilization produces competition over rights and liberties and engenders a constitutionally liberal political pole, boosting liberal presence in public debate. In short, while ethnic mobilization may embolden illiberal mobilization, it concurrently constrains its democratically corrosive systemic impact. This occurs via the electoral strength of ethnic parties, as well as via the electoral strength of constitutional liberals that are electorally stronger and have political parters among ethnic representatives in societies with mobilized ethnic minorities (as per H1).

H2: Electoral strength of ethnic parties attenuates the negative effect of illiberal forces on democracy.

H3: Electoral strength of constitutional liberals attenuates the negative effect of illiberal forces on democracy.

Importantly, in societies with mobilized ethnic minorities, it is the combined strength of ethnic parties and majority constitutional liberal parties that constrains the negative impact of illiberal forces on democracy.

H4: The combined electoral strength of ethnic parties and constitutional liberals attenuates the negative effect of illiberal forces on democracy.

Finally, ethnic mobilization and electoral success makes it possible for ethnic minority government inclusion. The presence of ethnic minority representatives in government acts as an important fetter to democratic erosion. As seekers of minority rights that require the constraint on the rule of the majority in the form of institutions, laws, and norms of equality, ethnic minority parties are likely to oppose or at least limit the dismantling of counter-majoritarian institutions and democratic practices when they are in government. At times, ethnic minority representatives may collude with majority forces, including illiberals, seeking pork via corruption. However, the search for pork does not prevent the search for principles. Even in cases of corrupt collusion, ethnic minority representatives are likely to favor rights and liberties central to their constituents, constraining various backsliding attempts of their coalition partners.

H5: Ethnic party government participation improves democracy.

Ethnic minority political mobilization thus underpins democracy by strengthening the liberal pole of politics in the form of ethnic representatives and constitutionally liberal parties that can limit the ability of illiberal forces to degrade democracy. Ethnic mobilization is not the sole source of democratic resilience, as democratization and democratic decay may follow distinct trajectories and depend on more complex patterns of causation involving actors, institutions, and historical legacies (e.g., Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021). The particular strength of ethnic minority mobilization lies in the social rootedness of ethnic minority interests, and thus of the political actors that mobilize and represent them. The almost existential search for rights and liberties in order to survive as a distinct group endows minority representatives with more stable electorates determined to deepen pluralism and constrain majority rule. The following section sets out the data and methods used to test these theoretical expectations.

DATA AND METHODS

To test the above hypotheses, this article uses a mixed methods approach. First, it analyzes quantitative data from 11 countries in eastern Europe: Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. These eastern members of the EU provide an ideal testing sample due to their variance in democratic backsliding, as well as in the mobilization of ethnic minorities. Since they are currently EU members, this selection controls for EU accession conditionality and its removal. These 11 countries have the same context conditions and causal homogeneity ideal for comparison. Second, to complement the statistical analysis and provide deeper understanding of within-case processes, this article turns to the cases of the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005). These two countries share a number of similarities that make them least likely to show marked differences in democratic development. Simultaneously, they differ in a number of ways. While the Czech Republic does not have any significant ethnic minority parties, Slovakia, home to a sizable Hungarian minority, has had a number of political organizations explicitly serving minority interests. The case analysis traces the democratic development of the two countries since 1990, and leverages the variation in the presence of mobilized ethnic minorities across the cases (Waldner Reference Waldner2012). This isolates the processes through which ethnic minority action influences democratic development in the context of other factors.

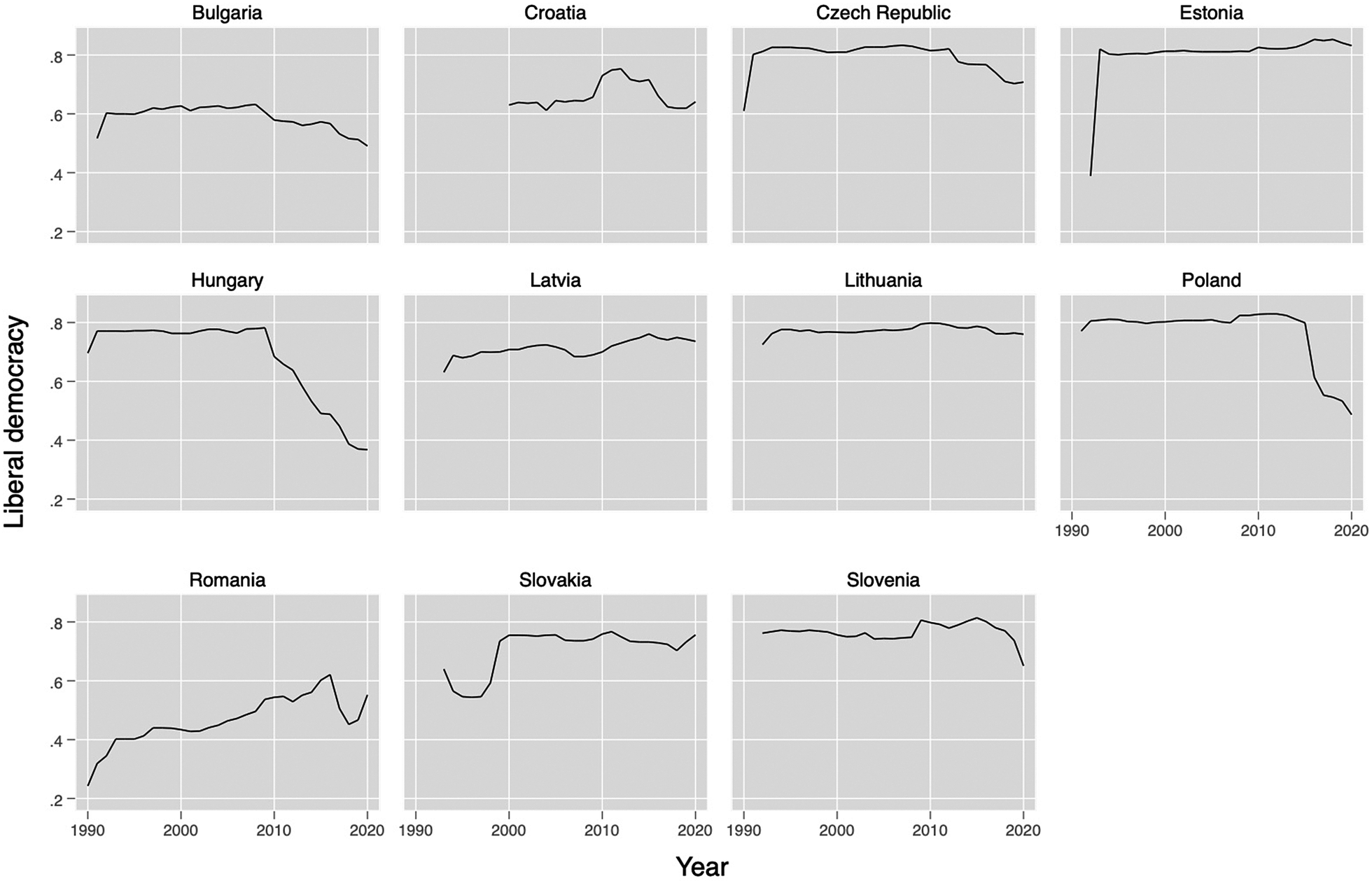

The article focuses on democratic backsliding as the decline of liberal democratic institutions and practices. The dependent variable is thus operationalized as the deviationsFootnote 5 in democratic scores using the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) measure of liberal democracy, which focuses on “constitutionally protected civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances that, together, limit the exercise of executive power. To make this a measure of liberal democracy, the index also takes the level of electoral democracy into account.” (V-Dem 2020, 43). As a robustness check, the Supplementary Material compares this measure with the complete set of V-Dem measures and reestimates the key results with this alternative operationalization. The results are substantively identical. Figure 2 demonstrates the level of liberal democracy across the 11 countries over time. Showing the initial levels of democracy from the early 1990s until the 2000s, as well as the gradual democratic backsliding in some of the well-documented cases, such as Hungary and Poland, it lends face validity to this operationalization. The V-Dem measure is considerably more nuanced than alternative measures, such as Polity and Freedom House (see Section A.2 of the Supplementary Material for details).

Figure 2. Liberal Democracy

Illiberal parties and constitutional liberal parties are identified with the use of the V-Party dataset and its measure of anti-pluralism. The detailed list of illiberal parties is listed in Table A3, constitutional liberals are listed in Table A4, and ethnic parties are listed in Table A5 in the Supplementary Material. The Supplementary Material provides extensive details about these party classifications (A.4), considers alternatives (A.5), and carries out extensive additional tests (A.6), demonstrating the robustness of the results to various party-type specifications.

In order to test H1, I compare the vote share for constitutionally liberal parties across countries with and without ethnic mobilization, operationalized as countries without significant ethnic minorities (the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland) versus those with significant ethnic minorities (Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia). In order to test H2–H5, the analyses model the level of democracy through a time-series cross-section. This analysis of country-years predicts the deviations in democracy as a function of the vote share for illiberal parties in interaction with ethnic vote share, constitutionally liberal vote share, and their combined vote share, as well as ethnic party government participation.

The data for vote share and government participation are obtained from the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2019). The analysis controls for GDP per capita (World Bank), income inequality (Solt Reference Solt2020), unemployment levels (World Bank), quality of government (QoG), and EU membership. Missing data have been imputed using within country temporal linear interpolation and extrapolation.

This analysis turns to fixed-effects estimation to deal with unit effects capturing specific country characteristics, particularly historical development and institutions, and includes country-clustered robust standard errors to address potential within-country dependence. The estimated models are:

$$ {y}_{it}-{\overline{y}}_i={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\beta \left({\mathbf{X}}_{it}-{\overline{X}}_i\right)\times \left({\mathbf{Z}}_{it}-{\overline{Z}}_i\right)+\gamma \left({\mathbf{C}}_{it}-{\overline{C}}_i\right)+\delta {\mathbf{T}}_t\\ {}+\hskip2px \left({a}_i-{\bar{a}}_i\right)+\left({u}_{it}-{\bar{u}}_i\right).\end{array}} $$

$$ {y}_{it}-{\overline{y}}_i={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\beta \left({\mathbf{X}}_{it}-{\overline{X}}_i\right)\times \left({\mathbf{Z}}_{it}-{\overline{Z}}_i\right)+\gamma \left({\mathbf{C}}_{it}-{\overline{C}}_i\right)+\delta {\mathbf{T}}_t\\ {}+\hskip2px \left({a}_i-{\bar{a}}_i\right)+\left({u}_{it}-{\bar{u}}_i\right).\end{array}} $$

Here, the dependent variable

![]() $ {y}_{it}-{\overline{y}}_i $

is country-demeaned liberal democracy.

$ {y}_{it}-{\overline{y}}_i $

is country-demeaned liberal democracy.

![]() $ ({\mathbf{X}}_{it}-\overline {{\mathbf{X}}_i}) $

is the deviation of illiberal vote share from its country-specific means.

$ ({\mathbf{X}}_{it}-\overline {{\mathbf{X}}_i}) $

is the deviation of illiberal vote share from its country-specific means.

![]() $ ({\mathbf{Z}}_{it}-{\overline{Z}}_i) $

is either the demeaned ethnic, constitutional liberal, or their combined vote share.

$ ({\mathbf{Z}}_{it}-{\overline{Z}}_i) $

is either the demeaned ethnic, constitutional liberal, or their combined vote share.

![]() $ ({\mathbf{C}}_{it}-{\overline{C}}_i) $

is a matrix of time-variant control variables, again demeaned to consider their over-time deviation from country means.

$ ({\mathbf{C}}_{it}-{\overline{C}}_i) $

is a matrix of time-variant control variables, again demeaned to consider their over-time deviation from country means.

![]() $ {a}_i $

is the unobserved unit effect, which reduces to zero, and

$ {a}_i $

is the unobserved unit effect, which reduces to zero, and

![]() $ {u}_{it} $

is random error.

$ {u}_{it} $

is random error.

![]() $ {\mathbf{T}}_t $

controls for time, absorbing any over-time trend variance, leaving the residual variance trend-free.

$ {\mathbf{T}}_t $

controls for time, absorbing any over-time trend variance, leaving the residual variance trend-free.

In order to assuage any concerns about this model specification, the Supplementary Material reports a number of alternative models. Section A.7 of the Supplementary Material includes random country intercept multilevel specification, estimations with an alternative dependent variable, estimation including a lagged dependent variable, specifications including year fixed effects, and bootstrapped standard errors. Section A.8 of the Supplementary Material further reports results of models that remove outlying countries—Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, and Poland—controls for the pluralism of other political parties, and controls for lagged dependent variable and country and year fixed effects. These results provide the same substantive conclusions as the main model. The following section carries out these analyses and reports their results.

ETHNIC MOBILIZATION AND DEMOCRACY

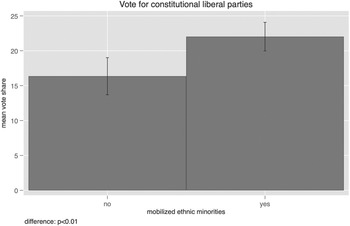

H1 expects that the presence of politically mobilized ethnic minorities improves the electoral chances of constitutionally liberal parties. To assess this, I consider the vote shares of constitutionally liberal parties across societies with and without politically mobilized ethnic minorities. The result, together with a test of the difference, is summarized in Figure 3. The figure demonstrates that constitutionally liberal parties receive approximately 16% of the vote in countries without mobilized ethnic minorities, whereas they receive approximately 22% of the vote in countries where ethnic minorities organize and compete politically. This important difference is statistically significant. This result provides a confirmation that ethnic mobilization associates with increased support for the constitutionally liberal pole of politics.

Figure 3. Ethnic Mobilization and Constitutional Liberal Vote Share

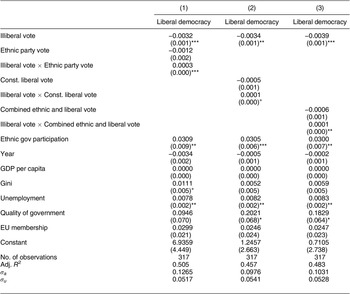

In the next step, I turn to assess democratic performance as a function of illiberal, ethnic, and constitutionally liberal vote share, and ethnic party government participation using time-series cross-sectional analysis. The analyses are reported in Table 1. First, all three models in the table demonstrate the significant negative effect of illiberal vote on liberal democracy, highlighting the corrosive effect of illiberal party strength. The interaction effect in Model 1 shows that ethnic vote share increase moderates the negative effect of illiberal electoral success on liberal democracy, supporting H2. The interaction effect in Model 2 shows that constitutionally liberal vote increase weakly moderates the negative effect of illiberal electoral success on liberal democracy. Given that this effect is only significant at the 0.1 level, it lends insufficient support to H3. The interaction effect in Model 3 shows that the combined vote of ethnic and constitutionally liberal parties strongly moderates the negative effect of illiberal electoral success on liberal democracy, supporting H4.

Table 1. Time-Series Cross-Sectional Analysis of Liberal Democracy

Source: V-Dem, ParlGov, Solt, QoG, and World Bank. Note: Country fixed effects with country-clustered robust standard errors.

![]() $ {}^{+}p<0.10 $

,

$ {}^{+}p<0.10 $

,

![]() $ {}^{*}p<0.05 $

,

$ {}^{*}p<0.05 $

,

![]() $ {}^{**}p<0.01 $

, and

$ {}^{**}p<0.01 $

, and

![]() $ {}^{***}p<0.001 $

.

$ {}^{***}p<0.001 $

.

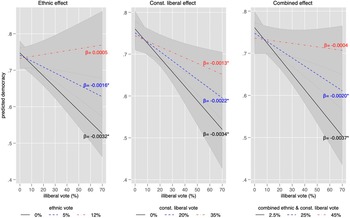

To better demonstrate these interaction effects, Figure 4 shows how the negative effect of illiberal vote share on democracy is moderated by ethnic vote share (left panel), constitutional liberal vote share (middle panel), and combined ethnic and constitutional liberal vote share (right panel). The greater the vote share for ethnic and constitutionally liberal parties, the weaker the negative influence of illiberal vote. The figure underlines the strong moderating effects of ethnic vote share, and combined constitutional liberal and ethnic vote share, while the moderating effect of constitutional liberal vote share alone is weaker. This is consistent with the expectation that ethnic parties are more existentially concerned with rights and liberties even than constitutional liberal parties of the majority while showing their powerful combined effect.

Figure 4. Predicting Democracy as a Function of Vote Shares

Note: All control variables held at their mean, except EU membership=1 and ethnic gov participation=0.

*Partial slope significant at the 0.01 level.

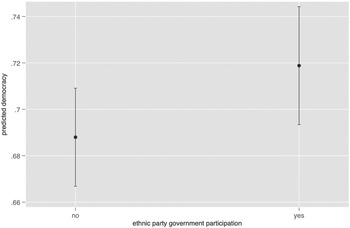

H5 finally asserts that ethnic party government participation improves democracy. This hypothesis is supported in all models of Table 1, showing a significant positive effect of ethnic party government participation. Figure 5 based on Model 1 underlines this positive effect. When ethnic parties participate in government a country’s democratic score is significantly higher.

Figure 5. Predicting Democracy as a Function of Ethnic Parties in Government

Note: All control variables held at their mean, except EU membership=1. Difference in predicted values is statistically significant (

![]() $ {\chi}^2=12.55 $

,

$ {\chi}^2=12.55 $

,

![]() $ p<0.000 $

).

$ p<0.000 $

).

The following section considers the dynamics connecting ethnic mobilization with democracy by comparing the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

DEMOCRATIC DYNAMICS IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC AND SLOVAKIA

This section complements the above quantitative study by providing a within-case analysis of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, tracing the processes that link ethnic minority mobilization and democratic resilience. Owing to their common history, the countries largely share similar constitutional and institutional makeup, which makes them unlikely to show marked differences in democratic dynamics. The two countries differ in some respects. Historically, the Czech lands became highly industrialized, urbanized, and secularized by the early twentieth century, whereas Slovakia remained more rural, agricultural, and religious. Further, today, the Czech Republic possesses an additional layer of checks and balances in the form of an upper chamber of parliament, not present in Slovakia. Both the historical and institutional endowments suggest that, if any differences should be found, it is the Czech Republic that should be the more auspicious ground for a resilient democracy. The Czech lands experienced major ethnic cleansing in the form of the Holocaust, as well as expulsions of its German-speaking population in 1945 and 1946, leaving the Czech Republic without politically mobilized minorities. Slovakia, on the other hand, experienced the Holocaust, but maintains a significant Hungarian minority which makes up approximately 10% of the population.Footnote 6

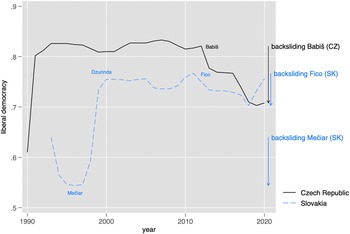

Figure 6 depicts the democratic paths of the two countries. It demonstrates a rapid democratization of the Czech Republic in the early 1990s, benefiting from its favorable historical endowments. Slovakia experiences initial backsliding under Vladimír Mečiar, but catches up rapidly in the late 1990s with the government of Mikuláš Dzurinda. In the 2010s, both the Czech Republic and Slovakia experience backsliding under illiberal leadership of Andrej Babiš and Robert Fico, respectively. Strikingly, Czech backsliding under Babiš is significantly greater than the Slovak one under Fico, as the arrows depicting the magnitude of backsliding on the right side of Figure 6 show.

Figure 6. Liberal Democracy in the Czech Republic and Slovakia

Source: V-Dem data. The arrow length depicts the magnitude of backsliding.

Swift Czech democratization in the early 1990s is driven by the constitutionally liberal Civic Forum (OF) closely tied to Václav Havel. The nascent party system, which effectively excludes the unreformed communist party, focuses around socioeconomically dominated competition between moderate center-left Social Democrats (ČSSD) and center-right Civic Democrats (ODS) rooted in class interests (Mateju et al. Reference Mateju, Rehakova and Evans1999). While these two parties stabilize Czech democracy, they also seek to limit political competition to their benefit.Footnote 7 Slovakia struggles since its independence in 1993. The illiberal government of Vladimír Mečiar’s Movement for Democratic Slovakia (HZDS) carries out only partial reforms and establishes an illiberal regime (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005). In line with expectations of the ethnic politics literature, Mečiar focuses on national state building, utilizing ethnic scapegoating aimed at the Hungarian minority to maintain his support (Haughton Reference Haughton2014; Haughton and Fisher Reference Haughton and Fisher2008). Simultaneously, the Hungarian minority mobilizes. Initially, their effect is limited due to their political fragmentation into three parties. Their aim, nonetheless, is to achieve a “pluralist democracy” in Slovakia (Csergö Reference Csergő2002, 8). Their search for pluralism is reflected immediately in their attempt to change the new Slovak constitution to include a civic conception of statehood open to all minorities by amending the constitutional preamble to refer to all citizens of the Slovak Republic. In the context of Mečiar’s deepening illiberalism in the mid 1990s, and with the aid of EU accession (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005), the opposition begins to coordinate. Mečiar seeking to undermine opposition coalitions passes an electoral law that induces Slovak democratic forces to unite into two cooperating blocks. The Slovak Democratic Coalition (SDK), led by Mikuláš Dzurinda, unites center-right Slovak parties seeking democratization. The Party of Hungarian Coalition (SMK) gathers the three ethnic Hungarian parties that broadly share an opposition to the current national conception of the Slovak state, support multiculturalism, and are deeply committed to restoring democratic rule of law in Slovakia (Mihálik and Žúborová Reference Mihálik and Žúborová2016).

The presence of mobilized ethnic parties in Slovakia strengthens the constitutionally liberal pole in the country. The 1998 watershed elections see the victory of the constitutionally liberal SDK. Dzurinda forms a government with the Hungarian SMK; a government described as “one of the most staunchly prodemocratic pro-Western governments in the region” (Deegan Krause Reference Deegan Krause2003, 69). The government sets out rapid reforms, passing extensive democratic and minority rights legislation (Csergö Reference Csergő2002). With 20 MPs and 3 ministers, SMK has a very strong position in the government, and its leaders are evaluated as “among the most competent and professional of its members” (Deegan Krause Reference Deegan Krause2003, 78; Kopa Reference Kopa2008). The cooperation of constitutional liberals and ethnic parties boosts Slovakia’s democratic performance under Dzurinda’s leadership, as depicted in Figure 6, supporting the hypotheses of this work.Footnote 8

The 2000s see a period of democratic right-wing governments with consistent participation of constitutional liberal and ethnic minority parties. The liberal pole of Slovak politicsFootnote 9 is relatively organizationally volatile (Mesežnikov and Gyarfášová Reference Mesežnikov and Gyárfášová2018). However, it is significantly emboldened by the salience of issues concerning rights and liberties, as well as by the cooperation with the Hungarian SMK starting in 1998, and continuing throughout the 2000s in government and in opposition.

Conversely, the Czech party system shows weaker presence of constitutionally liberal political forces. As the major ČSSD and ODS embark on cartelized cooperation (Klíma Reference Klíma2015), which tempers democratic performance from the late 1990s onward, minor constitutional liberals have limited ability to react, as the landscape is made up of rather ephemeral organizationsFootnote 10 that appear and disappear frequently (Havlík and Voda Reference Havlík and Voda2016), and their electoral support is generally lower than in Slovakia. In the Czech case, it is the Senate that has played a limited role of a constitutional watchdog (Pehe Reference Pehe2018).

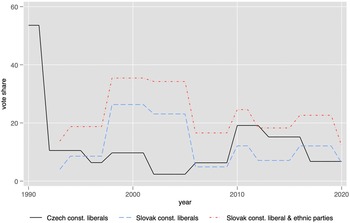

Figure 7 traces the electoral support of constitutionally liberal and ethnic forces across the two countries. The Czech case shows a high vote for constitutional liberals only in the early transition period. It increases again in the 2010s thanks to the rise of TOP09, whose electoral success is, however, short-lived. Slovakia shows the important electoral spike of constitutional liberal forces in the SDK coalition in Slovakia around 2000, associated with democratic restoration. Importantly, the combined support for constitutional liberal and ethnic parties in Slovakia is consistently higher than that for Czech constitutional liberals, who have no mobilized ethnic parties to cooperate with.

Figure 7. Vote Share of Const. Liberal and Ethnic Parties in the Czech Republic and Slovakia

Source: ParlGov data.

In the 2010s, both countries experience democratic erosion with the rise of new illiberal forces—Andrej Babiš’s movement ANO, which joins the Czech government in 2013, and Robert Fico’s SMER party which gains an unprecedented absolute majority in the Slovak parliament in 2012. Both parties are less illiberal than their Hungarian or Polish counterparts; however, both parties combine anti-pluralist state capture with ethnocentric populist rhetoric. SMER, a break-away from the social democratic party, initially focuses on socioeconomic topics (Haughton Reference Haughton2014; Haughton and Rybář Reference Haughton and Fisher2008). Over time, however, SMER swings toward a confrontational style of politics (Stanley Reference Stanley2011). After its 2012 landslide victory, SMER turns to state capture and undermining of the justice system while utilizing ethnic rhetoric especially in the context of the 2015 refugee crisis (Bútorová and Bútora Reference Bútorová and Bútora2019; Mesežnikov and Gyarfášová Reference Mesežnikov and Gyárfášová2018).Footnote 11 Similarly, while Babiš’s ANO originally presents itself as a liberal party, it “capture[s] state administration and policymaking” (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020, 318) while using “fear of refugees and Muslims to create a sense of external threat to Czech national identity” (Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018, 282).

In the Czech Republic, the possibility to constrain the illiberalism of Andrej Babiš’s ANO is slender, as the constitutionally liberal political pole is weak and there are no mobilized ethnic parties. While the system of checks and balances is bolstered by the presence of the Senate, an illiberal president Miloš Zeman cooperates with Babiš and undermines liberal forces. The Greens and other constitutional liberals are decimated by internal struggles or scandals, and consequently, the only possible corrective to the populist ANO is the mainstream ČSSD. ANO first enters government as a junior coalition partner of the larger ČSSD in 2013, eventually winning the 2017 election and coming to dominate Czech politics. While ČSSD seeks to constrain ANO’s illiberal tendencies, the party’s ability to do so is limited. First, ČSSD does not support a specific constituency whose interests are directly served by the maintenance of political pluralism and civil liberties. Second, ČSSD does not control the crucial ministry of justice, allowing ANO to eventually nominate a justice minister seen as protecting Babiš’s interests. Finally, the party experiences longer-term internal tensions between a liberal wing and a nationalist conservative wing, with the latter rising into prominence, constraining the liberal corrective capacity of the party (Dawson and Hanley Reference Dawson and Hanley2019). Only after the establishment of Babiš at the head of Czech politics does the Czech Republic witness the mobilization of constitutionally liberal political forces primarily in the form of a civic movement “Milion chvilek pro demokracii”Footnote 12 organizing mass demonstrations, leading to Babiš’s electoral defeat in 2021.

The situation in Slovakia is different. SMK’s longtime leader, Béla Bugár, founds a new explicitly interethnic political party, Most-Híd, meaning “bridge” in Slovak and Hungarian. Core party values are those of a modern liberal party: interethnic cooperation, protection of democracy and of individual rights of all citizens, including gender equality, and nondiscrimination of sexual minorities (Most-Híd N.d.), and a focus on concerns of all minorities in Slovakia, including the most disadvantaged Roma (Mihálik and Žúborová Reference Mihálik and Žúborová2016). The party becomes an important force, obtaining more than 8% of the vote in 2010 and entering the Radičová government.

In 2016, Fico loses significant electoral support, but SMER remains the largest party in parliament. Furthermore, two explicitly anti-system radical right partiesFootnote 13 enter parliament, making it impossible to form a government without SMER. In this situation, the constitutionally liberal Most faces a dilemma of whether to join a government with SMER and the nationalist SNS or not. The party’s response is perhaps typical of ethnic minority parties, who tend to see the access to office as a means for gaining support and benefits for their ethnic electorate (Aha Reference Aha2019). In 2016, Most feels that SMER and SNS would cause explicit harm to ethnic interests, especially given the growing presence of radical nationalism in parliament, and that Most could act as a guarantor of basic rights more effectively in a governing position (Interviews 3, 4, and 6).

How does Most maintain democratic principles in the difficult coalition with SMER and SNS? Most approaches coalition building with narrow, but clearly defined, and democratically crucial demands established in the coalition agreement, and reflected in the ministerial portfolios the party controls (Government of Slovakia 2016, Interview 6). While Most naturally focuses on minority language and culture, and regional development of southern Slovakia, disproportionally inhabited by ethnic Hungarians, the party also engages with issues of rule of law, which becomes a specific chapter in the coalition agreement (Government of Slovakia 2016, Interview 3).Footnote 14

In the area of rule of law, Most controls the ministry of justice, headed by a leading Most politician of Slovak ethnicity, Lucia Žitňanská. She actively pushes reform of the legal environment in the country, such as creating a hearing for constitutional judges, passing an amendment extending the legal response against political extremism (Zákon č. 316/2016), or creating a new law on the transparency of public financing (Zákon č. 315/2016). Unlike Most’s activity concerning minority language and culture, its enhancement of the rule of law leads to direct conflict with SMER and SNS (Interview 3). An academic observer suggests that Most played “a corrective role” in the government, with Béla Bugár being a “pillar of democratic direction” (Interview 2). This suggests that, though clearly constrained and at times perhaps complicit, Most manages to meaningfully moderate the illiberal tendencies of the SMER government, supporting H5.

This development shatters in the context of the murder of journalist Ján Kuciak, investigating connections between prime minister Fico together with other key SMER politicians and organized crime in February 2018. This fuels a major public outcry, eventually leading to Fico’s resignation. Most faces a second dilemma whether to stay in government or not. The party is divided between younger and urban liberals wishing to leave government, while the elites from the southern regions vote to stay in government (Interviews 3–5). Most’s continuation in a delegitimized SMER government beyond 2018 has disastrous consequences. It obliterates Most’s prior achievements, and leads to the party’s electoral collapse in the 2020 elections (Interview 2). While Most meaningfully corrects the government prior to 2018, in the aftermath of Kuciak’s murder, Most’s presence in government seems purely self-serving.

The exogenous shock of Kuciak’s murder changes the government participation calculus dramatically, but many of Most’s traditional ethnic representatives are unable to understand and adapt. This suggests a vulnerability of ethnic minority office seeking strategy. Simultaneously, while Most could not entirely limit various corrupt practices, it is clear that prior to 2018, Most, as a significant pluralist political force, manages to moderate various illiberal tendencies of the SMER-led government, particularly through its work on minority language rights, and rule of law, lending support to H5.

This analysis highlights various corrective mechanisms through which ethnic Hungarian representatives support democratic development in Slovakia. These are: liberal role in constitution-making; active participation in liberal democratic coalitions; raising the salience of rights issues; seeking interethnic collaboration in a liberal party (Most); and joining illiberals in government to provide internal constraint by controlling key portfolios. This underlines why Slovak democratic backsliding, clearly accelerated by Fico’s 2012 government, is overall less precipitous than that of the Czech Republic which does not have any significant minority parties, and whose constitutionally liberal forces are more easily marginalized by the rise of illiberalism (see Figure 6).

CONCLUSION

Democratic backsliding undermines democratic achievements, as well as academic expectations of unidirectional democratic consolidation. The literature identifies illiberal forces as the core culprit of democratic backsliding, as they erode democratic institutions, practices, and norms. This article corroborates the negative role of illiberals while identifying its potential antidote—politically mobilized ethnic minorities. The democratic consequences of ethnic politics have not received adequate academic attention, as most literature expects ethnicity to be a particularistic nuisance at best, and a source of violent conflict at worst. This article, however, argues that politically mobilized ethnic minorities can be an important source of democratic support. As potentially permanent political minorities, ethnic minorities seek to ensure their group survival and basic rights through a pluralist political order that restrains the tyranny of the majority. When these minorities are sufficiently organized to build parties capable of winning elections and becoming political partners, their presence bolsters liberal democratic politics, and limits the ability of illiberals to undo democracy.

This article demonstrates that mobilization of ethnic minorities improves the political opportunities of constitutionally liberal forces. The presence of mobilized ethnic minorities increases the contestation over minority rights, which emboldens nationalist appeals opposed to minority rights among a segment of the majority population (Bustikova Reference Bustikova2019) while simultaneously amplifying the support for constitutionally liberal politics and parties. Representatives of ethnic interests seek minority–majority cooperation that can erect a bulwark against democratic erosion. This cooperation is enabled by the political flexibility of ethnic representatives, able to support both left- and right-wing moderates. This political flexibility due to their focus on mostly noneconomic issues makes them relatively easy coalition partners. Consequently, they can provide democratic moderation in a wider scope of situations, even in partnership with potentially undemocratic incumbents, as the case of Most in Slovakia underlines. An existence of such flexible democratic corrective is less likely in societies that lack organized ethnic parties. Majority constitutional liberals can oppose illiberal incumbents in the absence of mobilized ethnic minorities, as shown, for example, by the 2019 mayoral election in Budapest, the 2020 women’s protests in Warsaw, or the 2021 elections in the Czech Republic. This article, however, demonstrates that the democratic correction in the absence of mobilized ethnic minorities is generally weaker than it would be in their presence.

This article highlights that constitutionally liberal and, particularly, ethnic minority parties play a key role in reinforcing liberal democracy by weakening the corrosive effect of the illiberals, who are the key source of democratic backsliding. Parties supporting ethnic minorities limit the electoral reach and coalition potential of illiberals, who are unlikely to make electoral inroads among ethnic and liberal voters. Countries with mobilized ethnic minorities witness antidemocratic nationalism, as the case of Slovakia demonstrates, but the illiberals are more likely to be restrained. In the presence of mobilized ethnic minorities, illiberals are unlikely to dominate politics unchecked for over a decade, as is the case in Hungary which lacks significant, politically organized minorities. At times, ethnic representatives join in governments with illiberals. They enter these difficult coalitions out of self-interest, in order to constrain the erosion of minority rights. In doing so, ethnic minorities curb the antidemocratic predilection of their illiberal coalition partners.

The democratic influence of ethnic minorities is not unconditional. It is likely to be undermined when ethnic minority representatives see alternative avenues to political control, resources, and group security. Ethnic mobilization is thus a contextual factor that may embolden constitutionally liberal politics and limit the illiberal.

The argument of this article that politics of organized ethnic representation can boost democratic resilience is an important contribution to our understanding of democratic backsliding, adding explanatory power to previous accounts focusing on the role of illiberal forces. Furthermore, the findings that ethnic minority representation can infuse politics with liberal democratic aims is an important contribution to the sizable literature that sees ethnicity as largely particularistic, detrimental to ideological political competition, and leading to normatively negative outcomes. This article underlines the possibility that ethnic politics produce ideological content of contestation that explicitly strengthens democracy.

The fact that this article finds significant pro-democratic effect of ethnic politics in contemporary eastern Europe is remarkable, as it should not be the case. Indeed, ethnic politics is said to be detrimental to democratic functioning in general, and to the democratic development of eastern Europe in particular (e.g., Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995). This article argues and demonstrates otherwise. It is possible that the democratic influence of mobilized ethnic minorities is particularly auspicious in the conditions of contemporary eastern Europe. Having reached relatively high levels of development, having generally moderate to low levels of interethnic conflict, being at least nominally held to democratic standards by the EU which has provided important normative and legal bases for ethnic minority rights, socializing majority and minority politicians alike, the eastern European experience may have some idiosyncrasies. Nonetheless, the illustration that ethnic mobilization associates with democratic improvement anywhere is a crucial finding. Examples of ethnic minorities seeking democratic representation, equal rights, and multicultural cohabitation exist further afield. For example, the Kurdish Democratic Party of the Peoples (HDP) in Turkey (Selcuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020), or indigenous movements mobilized for constitutional changes in Latin America (Van Cott Reference Van Cott2000), suggest a broader applicability of the results of this article. Further research should consider the scope of this argument beyond eastern Europe, studying the conditional nature of ethnic claims across broader contexts.

Permanent ethnic minorities have much to gain from a liberal democratic order that ensures basic rights, liberties, and equality to all. Politically organized ethnic minorities thus tend to oppose democratic backsliding likely to undermine their basic security and ability to exercise their distinction, be it their phenotype, language, religion, or culture. The presence of organized ethnic minorities tends to provide a democratic bulwark able to limit democratic backsliding.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542200140X.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the APSR Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FUAARK.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by the Center for European Studies and Comparative Politics and the SAB grant of Sciences Po. I would like to thank Simon Bornschier, Zsuzsa Csergö, Marianna Dudášová, Zsolt Gál, Emiliano Grossman, Olga Gyarfášová, Florence Faucher, Filip Kostelka, Isabela Mares, Nonna Mayer, Jonathan Polk, James Stimson, Milada Anna Vachudova, Natasha Wunsch, Christina Zuber, and three anonymous reviewers for their help and constructive comments. Particular thanks for their support go to my family: Allison, Martin, and Julia Rovny.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the Scientific Advisory Board grant of Sciences Po, 2019.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the Sciences Po Research Ethics Committee. The author affirms that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.