Three Asian great ape species occur in Sumatra and Borneo: Pongo abelii and Pongo tapanuliensis (Nater et al., Reference Nater, Mattle-Greminger, Nurcahyo, Nowak, De Manuel and Desai2017) in northern Sumatra and Pongo pygmaeus in Borneo. The latter has three subspecies: the north-western Bornean orangutan Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus, the central Bornean orangutan Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii and the north-eastern Bornean orangutan Pongo pygmaeus morio (Groves, Reference Groves and Yeager1999, Reference Groves2001), all of which are categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Ancrenaz et al., Reference Ancrenaz, Gumal, Marshall, Meijaard, Wich and Husson2016). Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus is restricted to the upper Kapuas River in West Kalimantan (Indonesia) and Sarawak (Malaysia). It has the smallest population of the three subspecies, with a total of 3,000–4,500 individuals (Wich et al., Reference Wich, Meijaard, Marshall, Husson, Ancrenaz and Lacy2008) of which there are c. 1,300 in Sarawak (Ancrenaz et al., Reference Ancrenaz, Gimenez, Ambu, Ancrenaz, Andau and Goossens2005; Ancrenaz, Reference Ancrenaz2006; WWF Malaysia, 2018). Bornean orangutans are known to live in primary and secondary forests and are typically found in peat-swamp forest and lowland dipterocarp forest at < 500 m altitude (Rijksen & Meijaard, Reference Rijksen and Meijaard1999). Only an estimated 25% of orangutan populations live within protected areas (Singleton et al., Reference Singleton, Wich, Husson, Stephen, Utami-Atmoko and Leighton2004; IUCN, 2012).

Most orangutan range remains poorly documented, and updating and expanding baseline data, especially in unprotected areas such as limited production forests (forests in which there is selective logging) and production forests, is essential (Wich et al., Reference Wich, Gaveau, Abram, Ancrenaz, Baccini and Brend2012). The rate of deforestation in Kalimantan is increasing, threatening orangutan habitats. Improved management is thus needed for conserving orangutan populations outside protected areas by involving all stakeholders, developing and implementing best management practices, and working with local communities to avoid or mitigate negative human–wildlife interactions.

Two protected areas, Danau Sentarum Wildlife Reserve and Betung Kerihun National Park, in the upper Kapuas watershed, were home to relatively large populations of the Bornean orangutan until the 1990s (Meijaard et al., Reference Meijaard, Dennis and Erman1996). However, during 1973–1997 almost 30% of habitat disappeared in and around Danau Sentarum Wildlife Reserve (Russon et al., Reference Russon, Meijaard and Dennis2000) and it is likely that the orangutan population in this area has declined. Orangutans are, however, still commonly encountered in the unprotected areas of Sungai Palin and Nanga Awen, which lie between Danau Sentarum Wildlife Reserve and Betung Kerihun National Park (Fig. 1), although anecdotal evidence suggests that the number of orangutans in these two areas has fallen as a result of forest degradation.

Fig. 1 Sungai Palin and Nanga Awen, indicating the location of the transects used to survey for orangutan nests in limited production forest and peat swamp forests, in Kapuas Hulu, west Kalimantan, Indonesia.

In October 2017 we conducted orangutan population surveys in peat-swamp forests that are limited production forests under the authority of the local forest department of Kapuas Hulu and the local community of Nanga Lauk village. We established five line transects (0.6–1.2 km long, with a total length of c. 4.5 km) from the bank of the Palin River in Sungai Palin towards peat-swamp forests (Fig. 1). We counted orangutan nests along these transects in 5 days of survey walks, each with two observers.

A previous survey, using the the same method, undertaken in 1991 in Nanga Awen, c. 20 km away from Sungai Palin in the same landscape, recorded orangutan nests along three transects (1.0–1.2 km long, with a total length of 4.3 km). Here we also analyse these previously unpublished data, to determine orangutan density in August 1991 as a reference point for comparison with our 2017 survey.

In both 2017 and 1991 the perpendicular distance of all nests visible from each transect was measured with a tape. Density estimates for both sets of data were computed using the signed nest-count technique (Schaik et al., Reference Van Schaik, Azwar., Priatna, Nadler, Galdikas, Sheeran and Rosen1995). We used Distance 6.0 (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Buckland and Rexstard2010) to estimate the effective strip width and thus determine the survey area and estimate nest density in both Sungai Palin and Nanga Awen. Distance uses a detection curve to estimate detectability (Buckland et al., Reference Buckland, Anderson, Burnham and Laake1993) as a function of the perpendicular distance of nests from the centre of the transect (Cattau et al., Reference Cattau, Husson and Cheyne2014). We calculated nest density as Dn = n/L2w, where Dn is nest density, n is the number of nests counted on a transect; L is transect length (in km), and w is the effective transect strip width (measured in m, converted to km), and orangutan density was calculated as Do = Dn/prt, where Do is orangutan density, p is the proportion of nest builders, r is daily nest production rate per orangutan and t is nest decay rate (Russon et al., Reference Russon, Erman and Dennis2001; Morrogh-Bernard et al., Reference Morrogh-Bernard, Husson, Page and Rieley2003; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Knott, Pamungkas, Pasaribu and Marshall2005; Van Schaik et al., Reference Van Schaik, Wich, Utami and Odom2005). We used values of p = 0.85, r = 1.0 and t = 202, determined in studies (Ancrenaz et al., Reference Ancrenaz, Calaque and Lackman-Ancrenaz2004) at sites with a similar habitat type and disturbance level to our survey area (peat-swamp forest of Lower Kinabatangan and surrounding areas in Malaysia; Ancrenaz et al., Reference Ancrenaz, Gimenez, Ambu, Ancrenaz, Andau and Goossens2005).

We observed a total of 76 orangutan nests along a total of 4.5 km of transects in Sungai Palin, and 71 nests along a total of 3.4 km of transects were observed in Nanga Awen. Mean nest densities were 222 ± SE 82.14 and 499 ± SE 162.43 per km2 in Sungai Palin and Nanga Awen, respectively (Table 1). The density estimate for Sungai Palin in 2017 is slightly lower than that for Nanga Awen in 1991 (Table 1), suggesting that orangutan density may have halved between these dates and that the orangutan population outside protected areas remains relatively low. The building of new roads is one of the threats to the orangutan subpopulation on Sungai Palin (Local people, pers. comm., 2017).

Table 1 Effective strip width (± SE), Akaike's information criterion (AIC), % coefficient of variation (CV), mean density of orangutan nests (± SE, with 95% CI) and estimate of mean individual density (with 95% CI) in peat swamp forests of Sungai Palin surveyed in 2017, and Nanga Awen surveyed in 1991.

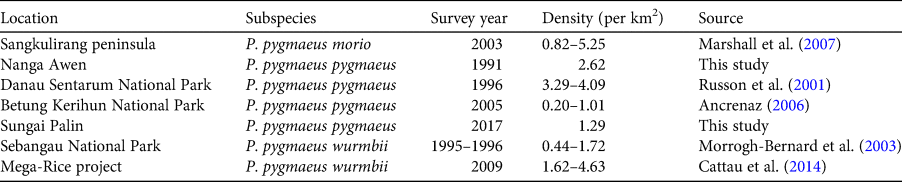

Estimated orangutan density in Sungai Palin is lower than in the peat-swamp forest of Danau Sentarum National Park and the peat-swamp forest of the former Mega-Rice project in central Kalimantan, higher than that in the lowland and hill lowland forests of Betung Kerihun National Park, but similar to that in Sebangau National Park (Table 2). Many factors influence orangutan density in disturbed forests, including food availability, connectivity between forest remnants, and whether orangutans can survive after habitat loss. The logging concession in the area of Nanga Lauk village has been inactive since at least 2003 (Local people, pers. comm., 2017), and there are no reports of local people hunting orangutans in the Nanga Lauk forest area, even though orangutans sometimes take honey from local beehives (Local people, pers. comm., 2017).

Table 2 Summary of information available on the density of the three Bornean orangutan subspecies, based on nest count surveys.

Protection forests surrounding the Sungai Palin and Nanga Awen landscape are under the jurisdiction of the district forestry agency, but are managed by the local community as the Nanga Lauk Village Forest (Hutan Desa). The community is allowed to extract non-timber forest products only. This initiative to include the local community in managing forest land has helped to protect the orangutan, as evidenced by the fact that logging ceased in 2003. The people of Nanga Lauk plan to expand the area of this Village Forest (Damayanti et al., Reference Damayanti, Hanjoyo and Berry2016).

More detailed surveys of the orangutan and its habitat are required in this area, so that the orangutan population can be appropriately managed. As Sungai Palin and Nangan Awen lie between Danau Sentarum Wildlife Reserve and Betung Kerihun National Park, awareness amongst the local communities of the importance of the orangutan population outside these protected areas is essential to help maintain connectivity between the orangutan populations.

Our surveys and calculations of orangutan density form a baseline for monitoring this orangutan population and for informing conservation action and management of non-timber forest products in the watershed landscapes of Sungai Palin. The orangutan population in the landscape of Sungai Palin, Nanga Awen and surrounding areas shold be a priority for community-based conservation.

Acknowledgements

We thank LTS International for giving AY the opportunity to survey orangutans in Sungai Palin peat land forest while he conducted a biodiversity survey in Nanga Lauk Village Forest for the ADB-funded project Sustainable Forest and Biodiversity Management in Borneo, Fauna & Flora International, UK, for the data from the 1991 surveys in Nanga Awen, the Nanga Lauk community, especially Simon, Hamdi and Yosep who helped us in Sungai Palin, and Chaerul Saleh and I Made Wedana, the orangutan survey team in Nanga Awen.

Author contributions

Study design and field work: AY; data analysis: AY; writing: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research did not involve human subjects, experimentation with animals or collection of specimens, and abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.