Knowledge, both popular and scholarly, concerning the life of James Croll (1821–1890) has been accumulating slowly since his obituarists produced appreciations of his work. The early death notices were relatively meagre as regards his personal life. William Thomson (1824–1907; ennobled as Lord Kelvin in 1892), addressed the Anniversary Meeting of the Royal Society of London in 1891 and said:Footnote 1

Of all recent writers who have contributed so much to current scientific literature, probably no one was personally so little known as Dr. Croll. His retiring nature kept him for the most part in the privacy of his own home.

Croll's Geological Survey colleague John Horne (1848–1928) published his obituary in the pages of Transactions of the Edinburgh Geological Society and was to observe ‘[o]f his private life it may be truly said that ‘whatever record leaps to light, he never shall be shamed’.Footnote 2 Most usefully, it was Croll's lawyer friend, James Campbell Irons (1840–1910), who produced a substantial compendium of Croll's work (the ‘Memoir’), and its Preface recorded:Footnote 3

HAVING been one of the intimate friends who urged Dr. Croll to write an autobiographical account of his remarkable career, it fell to me to arrange the materials which he left for publication. Unfortunately, the autobiographical sketch was never completed…. This volume has been written with the hope that the life of Dr. Croll, recording the triumph over his early struggles, his scientific researches, which secured him a world-wide reputation as an original thinker, and his earnest belief in the Christian faith, may prove interesting. It may only be added that the entire proceeds of its sale will be handed to his widow.

The core aspects of Croll's life are known well enough.Footnote 4 He was born in rural Perthshire to a stonemason and crofter father, and despite ill health and inadequate schooling he managed to educate himself in the key sciences to such a level that he produced fundamental publications on astronomically-related aspects of climate change, other outputs in areas as diverse as electro-mechanics, oceanography, geology and glaciology, as well as books on theism and religious metaphysics. In 1876 alone, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, an honorary Doctor of Laws of the University of St Andrews and an Honorary Member of the New York Academy of Sciences, yet his work trajectory was hardly as elevated and included employment as a wheelwright, tea merchant, insurance salesman, janitor and office clerk. His life was plagued by medical problems and financial concerns.

Other papers in the current volume offer thorough assessments of topics associated with Croll's work. However, as Irons stated at the end of his magnum opus, ‘the man was greater far than his work.’Footnote 5 By laying emphasis upon selected components of the passage of his life, including some of the less recognised or less arresting features of his biography, this paper seeks to provide a personal context for an understanding of James Croll the man as well as James Croll the scholar of sciences and religion.

1. Family history

It seems clear from the early pages of the ‘Autobiographical Sketch’, dictated to his wife Isabella and contained within Irons's tome, that family history was important to Croll.Footnote 6 On its first page he recorded details of the time, date and place of his birth, his parents, father's occupation, surname changes and information on the hamlet of Little Whitefield in which he resided (Figs 1, 2). The first paragraph noted that the baptismal register for Cargill parish had enabled him to trace his (paternal) ancestors to the middle of the 17th Century.

Figure 1 The first page of the ‘Autobiographical Sketch’ (Croll Reference Croll and Irons1887; published in Irons Reference Irons1896, p. 9).

Figure 2 Map of Great Britain, showing the location of places in which James Croll lived or visited.

The known genealogy of Croll and his wife are depicted elsewhere in this volume,Footnote 7 but Figure 3 is a partial direct line pedigree chart, which includes his wife and brothers and extends back to approximately the first third of the 18th Century. There is no record of any children born to James and Isabella. Croll's brief move to Elgin as a tea merchant, where he met his wife, was perhaps influenced by the fact that his mother's family hailed from there (Fig. 2). Behind the bald facts displayed in family trees are, of course, the miseries and joys of any existence. James Croll's parents were both 40 years old when James, the second of four sons, was born on 2 January 1821. His older brother Alexander died aged ‘about ten years’ and the youngest, William, ‘died in infancy’; the death of Alexander ‘was a severe blow to my parents, especially to my father, who never afterwards regained his former vivacity of spirits’.Footnote 8

Figure 3 Direct line vertical pedigree chart for James Croll (shaded), including his siblings and wife. Abbreviations: b = baptismal or birth date; m = marriage date; d = death or burial date.

Croll considered himself to possess more traits from his father than his mother:Footnote 9

My mother was firm, shrewd, and observing, and gifted with a considerable amount of what is called in Scotland ‘common sense.’ My father was mild, thoughtful, and meditative, and possessed of strong religious and moral sentiments. This amiable disposition and high moral character made him greatly esteemed and respected. But he had the misfortune to possess a most anxious and sensitive mind…. I have often thought that, had I possessed some more of my mother's qualities, and less of some of my father's, the battle of life would not have proved so painful to me. When a boy, I was always proud to tell, when asked, who my father was; for the mention of his name generally commanded respect, and procured for me a kindly word, with the remark, ‘I hope that when you grow up you will be as good a man as your father.’

A joy for Croll was certainly his marriage:Footnote 10

On the 11th September 1848, I was married to my wife, Isabella, second youngest daughter of Mr. John Macdonald, Forres. The union has proved a happy one. She has been the sharer of my joys, sorrows, and trials (and these have not been few) for the past forty years. Her care, economy, and kindly attention to my comfort during the years of comparative hardships through which we have passed, have cheered me on during all my trials and sorrows.

His life-long concern for his wife extended until close to his death. Only seven weeks before that event, he asked his friend George Carey Foster (1835–1919), Professor of Physics at University College London, to solicit the Royal Society of London for a payment from their Scientific Relief Fund in order that Isabella might be better cared for financially (see section 6).Footnote 11 This approach was successful, and Mrs Croll was granted £100.Footnote 12

Croll's anxiety over money lasted throughout his life and was exacerbated by difficulties surrounding his gargantuan efforts to secure a bigger pension from the Exchequer (see section 6). However, census records suggest that he perhaps supported his hunchbacked brother David who had retired by 1871, and he employed domestic servants in 1861 (in Glasgow while employed at the Andersonian UniversityFootnote 13) and 1881 (in Edinburgh, the year after his retirement from the Geological Survey). The existence of a servant employed in 1861 (Mary McKenzie, age 15) somewhat belied Irons's observation that ‘his household in the humble home at the Andersonian University consisted of himself, his wife, and his brother. They managed their domestic affairs entirely within and by themselves…’.Footnote 14 The absence of a servant in the Croll household during the census for 1871 may have been compensated for by domestic efforts from both David (who had previously helped James Croll whilst at the Andersonian) and Isabella's 17-year-old niece, Anabella MacHdwald (sic. = Macdonald), who is recorded as a scholar and was the daughter of Isabella's brother William.Footnote 15 At some stage after 1881, Croll ‘had no alternative but to give up housekeeping and go into cheap lodgings’,Footnote 16 though this was not to be a final outcome.

2. What's in a name?

The first sentence of the Autobiographical Sketch refers to Croll's family name: ‘My ancestors, who spelled their name Croil, and some of them, it would seem, Croyl…’. No more is said within the Sketch or the Memoir about the previous names and their evolution to Croll. Variations in naming resulting from illiteracy, phonetic spelling or preference were a commonplace in parish registers, censuses and other documents, and the International Genealogical Index recorded James's grandfather as Alexander Craill.Footnote 17

Fortuitously, first-hand evidence of Croll's name is provided by both him and his father in documents submitted to the Civil Service Commission concerning his recruitment to the Geological Survey of Scotland in 1867.Footnote 18 The documentation makes it clear that Croll's father spelt his name Croil and not Croyle or Crole (Croyle being the erroneous spelling of the Kirk Session Clerk). Croll became the preferred spelling of James and his brother David from the 1830s. As James went on to explain (letter dated 1 July 1867):Footnote 19

The foolish circumstance which led to the alteration from Croil to Croll was this: Upwards of thirty years ago, my younger brother and I, both of us then mere boys, took it into our heads, that as Croll and Croil were but different modes of spelling the same name, and that as the former mode was – to our young imaginations – the more elegant of the two, that we should adopt it in preference to the latter, which we accordingly did. In course of a year or two my father, to prevent confusion I suppose, began to follow our example and ever since, the family has always spelt the name Croll.

In case that any difficulties might in future arise from this somewhat imprudent change, I requested my father, before he died, to give me a written declarationFootnote 20 that I had changed the mode of spelling of my name from Croil to Croll.

Robinson proposes a further possible motivation for the name change – that the name Croil carried a derogatory association in eastern Scotland, signifying weakness, ‘a stunted person’ perhaps in relation to Croll's poor health, whereas Croll, in dialect terms, implied ‘reflection’.Footnote 21 Additionally, however, was the teenage Croll here thinking compassionately of his hunchbacked brother, an unspoken consideration to be weighed alongside childhood notions of elegance?

The foregoing sequence of names (Croil → Croll) does not conform with that on the Croll family headstone, which we are told ‘he had been at some pains to get erected himself’.Footnote 22 There the sequence reads Croyl → Croll (Croyl) → Croll.Footnote 23 As discussed elsewhere, the headstone likely dates from long before anything organised by James Croll, although he undoubtedly had the inscription augmented.Footnote 24

3. Homes

Apart from an attachment to his family history, the pages of the Sketch and Irons's Memoir also display some sense of place and contentment, with, for instance, Croll's mentions of the environs of his home parish, the walks in the neighbouring parish of Collace during ‘probably the happiest [year] in my life’Footnote 25 and rural walks after his evening meal when living in Morningside, Edinburgh. He was, though, an itinerant individual, and a study of his many addresses presents us with a timeline for his life (Table 1; Fig. 2) and a number of the buildings associated with him as homes or workplaces are still extant (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 Some extant buildings and locations associated with James Croll.

Table 1 James Croll: home addresses, other residential and work locations, and occupations.

1 Some street addresses may be work ones rather than homes.

2 Approximate unless specified otherwise.

3 As follows: BGS = British Geological Survey archives, Keyworth; Irons = Irons (Reference Irons1896), including Croll's Memoir of 1887; CSC = Civil Service Commission; Haslemere = Haslemere Educational Museum, Sir Archibald Geikie Archive; ICL = Imperial College London, Records of Thomas Henry Huxley Collection; JHU = Johns Hopkins University, Milton S. Eisenhower Library, MS 276; OB = Minute book, Andersonian Library, University of Strathclyde, 1860; RLF = British Library Royal Literary Fund, Loan 96 RLF/1/2220/1.

Addresses do not necessarily denote homes in the sense of a place in which to live and to feel comfortable. His geological colleague James Bennie recalled an excursion to Paisley where ‘[a]s we passed Glen Street, Mr. Croll, with a wistful look, said he once lived two years in that street, and liked it better than Glasgow’.Footnote 26 Croll was at his happiest work-wise while a janitor at the Andersonian College and Museum (Fig. 5) and unhappy as an insurance salesman in Leicester to which he was sent on transfer from Edinburgh by the Safety Life Assurance Company. It is difficult to know if his employments influenced his feelings of domestic satisfaction with both places, although it is reasonable to suppose that they did. Sojourns in Elgin and Devon represented efforts to regain his health, while stays in Manchester, London and Cambridgeshire were clearly for transit purposes. The relative lack of visits to the capital, in spite of the existence of reliable rail travel, his Fellowship of the Royal Society of London and meeting invitations, reveals a probable reluctance to travel much beyond familiar areas and an antipathy towards gatherings of learned societies (section 5).Footnote 27

Figure 5 Watercolour by John Alexander Gilfillan of the interior of the Andersonian Museum, ca.1831 (Archives and Special Collections, University of Strathclyde Library).

He seems to have lived in upwards of seven different properties after leaving Edinburgh in May 1881. Indeed, as Archibald Geikie (1835–1924), his employer at the Geological Survey of Scotland, was to remark: ‘You are quite a peripatetic philosophe, shifting your abode continually’.Footnote 28 Croll finally settled in Perth in the latter part of 1886, when, in his 65th year, he returned to his native county.

4. Health – a lifelong issue

Apart from an addiction to tobacco, which he managed to end, and as befits a sometime temperance hotelier, an abstinence from alcohol,Footnote 29 Croll had a lifetime of bodily challenges. There are numerous references to these in the Sketch, Memoir and various archival sources, primarily dealing with head, heart and elbow joint pain, but also mentioning problems with eyes, fatigue and other ailments. From the age of about six years he ‘became afflicted with a rather troublesome pain on the top or about the opening of the head, which prevented me being able, except in the heat of summer, to remain bareheaded.’Footnote 30 This was only a beginning as his own words display a mix of experiences and feelings concerning an assortment of maladies:Footnote 31

I unfortunately met with a mishap which has since entailed on me a considerable amount of pain and discomfort, and has disabled me all along for much physical exertion. One day, as I was exerting my whole strength in using a joiner's plane, while dressing a piece of wood, something suddenly appeared to give way about the region of the heart. Medical men have never been able to detect what is wrong. But ever since then, though my health and strength remained unimpaired, I durst not lift anything heavy, or attempt to run, or even walk fast….

It will naturally be asked why such want of success in life? Why so many changes, trials, and difficulties? There were several causes which conspired to lead to this state of things. The mishap to my elbow joint compelled me to give up the occupation of a joiner when a young man; and the inflammation which destroyed the joint five years afterwards had the effect of blasting my hopes in the way of shopkeeping. The main cause, however, and one of which I had been all along conscious, was that strong and almost irresistible propensity towards study, which prevented me devoting my whole energy to business. Study always came first, business second; and the result was that in this age of competition I was left behind in the race….

One evening in July of 1865, after a day's writing, I hurriedly bent down to assist in putting a few tacks into a carpet, when I experienced something like a twitch in a part of the upper and left side of the head. It did not strike me at the time as a matter of much importance; but it afterwards proved to be the severest affliction that has happened to me in life. Had it not been for this mishap to the head, all the private work I have been able to do during the twenty years which followed might have easily been done, and would have been done, in the course of two or three years. The affection in the head did not in any way affect my general health, neither did it in the least degree impair my mental energy. I could think as vigorously as ever, but I dared not ‘turn on the full steam.’ After this twitch a dull pain settled in that part of the brain, which increased till it became unbearable, if I persisted in doing mental work for any length of time. I was therefore obliged to do mental labour very quietly and slowly, for a short period at a time, and then take a good long rest. If I attempted to do too much in one day, I was generally disabled for a few days to come. Another consequence was this: before this affliction in my head, I could concentrate my thoughts on a single point, and exert my whole mental energy till the difficulty was overcome; but this I never could attempt afterwards.

When applying for entry to the Civil Service with the Geological Survey in Edinburgh, he had to furnish a medical opinion. His doctor in Glasgow had found:Footnote 32

that the left elbow joint is stiff from the effects of inflammation indured by previous injury otherwise he is at present in perfectly grand health. Notwithstanding the state of the joint he has the entire use of the arm and hands and [I believe him to be free from any physical defect or disease].

Croll's woes were compounded in 1880 when, in the Edinburgh office, he attempted to remove some maps from a drawer while standing awkwardly on some steps:Footnote 33

I unfortunately strained something about the region of the heart. The result was, that for months I was unable to walk about, or make any physical exertion…. Just at this time, I had been suffering rather badly from my old complaint in the head, and was at the time under the medical treatment of Professor Grainger Stewart.Footnote 34 This gentleman thought that it might be well to try what effect the external application of that powerful drug aconite might have in relieving the pain in the affected part of the head. His instructions were to apply a little of the aconite over the part when I felt the pain badly. I continued to do so for some time, but it had not the desired effect. One evening, after I had applied it once or twice, I all at once found that I had lost my power of speech, or rather, that I could only speak like a paralytic, in an unintelligible form. It is evident that this powerful poison had paralysed some of the nerves or muscles of the tongue or the lips. In course of a week or two I regained my speech, though even yet there are a good many words which I cannot pronounce.

As I was now disabled for duty both by head and heart, and as there was not much prospect that I should ever be fit for office work, it was considered advisable that I should resign.

Assuming that the loss of speech was due to the aconite rather than a stroke, then Croll was being treated with extracts of Aconitum spp. (Ranunculaceae family; cf. monkshood, wolfsbane), which has a long history of use in traditional medicine and poisoning.Footnote 35 Known side effects include cardiac arrhythmia and neurologic symptoms such as numbness of the mouth. Given its toxicity, it is perhaps no surprise that ‘the injurious effects of the aconite did not wholly disappear for several years’.Footnote 36

When attempting to claim additional pension payments following his early retirement, the medical certificates for Croll accentuated his health problems rather more than the supportive report provided for his Civil Service application. The one provided for the Geological Survey by Grainger Stewart was curt and sombre:Footnote 37

19. Charlotte Street.Footnote 38

Edinburgh.

Feby. 10th 1881

I hereby certify on soul and conscience that I have on many occasions examined Dr. Croll of the Geological Survey of Scotland, that he is suffering from disease of the circulatory and nervous systems of such a nature that there is no prospect of his being able again to perform the duties of his office.

When applying for financial support from the Royal Literary FundFootnote 39 in 1885, a brief medical report was provided by a Dr John Bower:Footnote 40

I hereby certify that I have known Dr Croll since shortly after his retirement from the Geological Survey; that he is not in a state of health to allow him to follow any occupation, and that, though able to write an occasional scientific paper with difficulty, it is altogether improbable that he will ever be able to add to his limited income by any literary exertion.

Given under my hand this 16th day of April 1885 at Perth N.B.Footnote 41

John Bower M.D., R.N. (Retired)

What is missing from his Sketch and the Memoir is any mention of what he claimed to have been a persistent ‘enemy’ in his youth – toothache. In a letter to his Geological Survey friend, Benjamin Neeve Peach (1842–1926), dated 10 October 1871, he commiserated:Footnote 42

I am sorry to hear that you are suffering from an old enemy of mine. When a young man I was annoyed for years with toothache until I thought of getting them stuffed.Footnote 43 Since then I never had toothache. By all means try the stuffing.

His health advice was also in evidence almost eight years later (1 July 1879):Footnote 44

My dear Peach,

…. The head is not much worse than ordinary but as writing is my greatest enemy I always take advantage of a willing pen when I can get it. You must take good care and keep within doors in wet weather. By all means try and avoid rheumatism….

The preceding quotation reveals Croll's willingness to benefit from the assistance of a scribe.Footnote 45 This is echoed frequently in Irons's Memoir where we learn that continued physical and mental tiredness led Croll to obtain ‘the services of a young man for an hour each evening, who either wrote for or read to him’, while his niece (Anabella Macdonald):Footnote 46

accompanied him, as my aunt was not able to walk any distance, and during our walks, should any thought occur to him on any of the subjects he was writing or thinking about, I had to write it down there and then, and sometimes I would grumble, as it was of no interest to me. He would add, ‘Well, if you don't, it may never occur to me again.’

In a letter to philosopher Shadworth Hodgson (1832–1912) dated 21 December 1887, Croll apologised for it ‘not being in my own writing’, while Hodgson commiserated with ‘I am sorry to see you are obliged to employ an amanuensis.’Footnote 47

His Congregational Church pastor friend David Caird recorded that:Footnote 48

One day he would listen to his amanuensis reading from a work of reference of criticism, and the next he would dictate a new paragraph of his own treatise. And this is but a faint indication of the difficulties and disadvantages under which Stellar Evolution and The Basis of Evolution were produced. That both books suffered from circumstances one can hardly doubt.

Only weeks before his death, Croll had writtenFootnote 49 to George Carey Foster with a request that his old friend seek funds from the Royal Society of London to help Isabella (see section 1), and explaining that having almost finished The philosophical basis of evolution:

…my health suddenly gave way, and I am now so weak as to be able to do little more than move about the house. The breakdown began as follows: I fell on the floor and lay insensible for above an hour; and when I recovered consciousness, I found I was not so strong either physically or mentally as formerly. I have since then had four or five cases of unconsciousness. What I am suffering from is a slow loss of power in the heart. This state of things will probably go on till the heart stops, an event which I am enabled to contemplate with the utmost composure, as it will be but the way of entrance to a better land.

The Death Register for Croll records that he died at 3.20 a.m. on 15 December 1890 from ‘Atheroma of vessels’ leading to ‘Cardiac syncope’;Footnote 50 in other words, an arterial build-up of plaque leading to the loss of blood to the brain and unconsciousness.

5. Awards, societies and attitudes to collegiality

5.1. Honorary memberships

In his Autobiographical Sketch of 1887, following mention of his accolades of 1876, Croll added:Footnote 51

I was afterwards chosen an Honorary Member of the Bristol Natural Society,Footnote 52 of the Psychological Society of Great Britain, of the Glasgow Geological Society, of the Literary and Antiquarian Society of Perth, and of the Perthshire Society of Natural Science. I had the honour of receiving from the Geological Society of London the balance of the proceeds of the Wollaston Donation Fund in 1872, the Murchison Fund in 1876, and the Barlow-Jamieson Fund in 1884.

One of the more intriguing of these is perhaps the Psychological Society of Great Britain. This only existed for the period 1875–1879 and seems to have collapsed as a result of some members straying away from the science of the mind into areas such as psychical research and the science of the soul.Footnote 53 In his Fourth Sessional Address to the Society, its President (Sarjeant Edward William Cox [1809–1879]) noted that ‘[o]ne of our Honorary Members,Footnote 54 Mr. James Croll, F.R.S., favoured us with perhaps the ablest papers [sic.] [e]ver read in this room on “The Psychological Aspects of Molecular Motion,” which all who did not hear should read’.Footnote 55 The Society's President read the paper on Croll's behalf and it was based closely on a paper he had written for the Philosophical Magazine.Footnote 56 Sarjeant's extended synopsisFootnote 57 quoted Croll's words:Footnote 58

Whatever may be one's opinions regarding the doctrine of Final Causes and the evidence of design in nature, all must admit the existence of the objective idea in nature.

– as well as abbreviated text, which he hoped presented ‘a faithful outline of his [Croll's] argument’Footnote 59 and, in part, derived from a longer section in Croll:Footnote 60

Natural selection will not explain this objective idea. Mr. DARWIN'S theory cannot, from its very nature, explain the mystery of the organic world. He does not trace the directing cause of molecular motions.

But then he finished by confessing ‘[i]t may be permitted to us to draw the conclusion from this admirable paper’ and:Footnote 61

Then come the questions:

What is this Intelligent determining power? GOD.

What is this underlying formative force that moves and moulds matter? SOUL–SPIRIT.

These are words with which Croll may have agreed, but he is unlikely to have considered using them in a scientific paper.

The statement (above) that he was ‘afterwards chosen an Honorary Member…of the Glasgow Geological Society’ is not quite correct. In the Proceedings for the Year 1866–1867 of the Society we read that ‘James Croll, Anderson's University, was elected an honorary associate’.Footnote 62 In the list for 1888, he was still an ‘honorary associate’,Footnote 63 while the likes of Archibald Geikie, Henry Bolingbroke Woodward (1832–1921), William Thomson and Edward Hull (1829–1917), a ‘hard-working man of shallow intellect’,Footnote 64 all of whom signed his nomination form for the Royal Society of London, were honorary members of the Geological Society of GlasgowFootnote 65 as, indeed, was Matthew Forster Heddle (1828–1897), the geologist at the University of St Andrews, who had proposed Croll for the honorary degree of LL.D. in 1875.Footnote 66

The available records of the Literary and Antiquarian Society of Perth, archived at the Perth Museum and Art Gallery, seem to contain no records of Croll. The Society itself was founded in 1784Footnote 67 and survived until 1915. It only produced one issue of its Transactions in 1827.Footnote 68 The Perthshire Society of Natural Science, founded in 1867, has few mentions of Croll in its various publications released under a mixture of titles (with permutations of Proceedings and Transactions of the Perthshire Society of Natural Science, covering, stutteringly, the period since 1870, alongside the Scottish Naturalist since 1871).Footnote 69

5.2. Financial support from the Geological Society of London

Croll was never a Fellow of the Geological Society of London,Footnote 70 yet he benefited financially from three awards from named society funds – the Wollaston, Murchison and Barlow–Jamieson. Events surrounding the first of these are deliciously described by Andrew Crombie Ramsay (1814–1891), Director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, in a letter to Archibald Geikie:Footnote 71

LONDON, 11th January 1872.

MY DEAR GEIKIE – Yesterday in the Council of the Geological Society I proposed Croll as a proper man to receive the Wollaston Fund for the year…. The President and others hailed my proposition. One objection raised was that Croll's researches involved no personal expense. PrestwichFootnote 72 and I thought that of no importance; but nevertheless if you can tell me anything on that score I shall be doubly armed –

And on the top of opportunity,

Quell the base scullion rogues, whose envy dull

Would squash the light of Genius, and instead

Display a dirty, spluttering, farthing dip,

And swear that 'tis the sun.

So look alive, my pigeon, and help in this good cause…. – Ever sincerely,

A. C. RAMSAY.

It is impossible to know whether the dissenting voice of the envious ‘base scullion rogue’ was a result of monied snobbishness. At the Annual General Meeting of the Geological Society on 16 February 1872, the President, Joseph Prestwich, tasked Andrew Ramsay with communicating the good news to James Croll, who was not present:Footnote 73

Professor RAMSAY, –The Wollaston Fund has been awarded to Mr. James Croll, of Edinburgh, for his many valuable researches on the glacial phenomena of Scotland, and to aid in the prosecution of the same. Mr. Croll is also well-known to all of us by his investigation of oceanic currents and their bearings on geological questions, and of many questions of great theoretical interest connected with some of the large problems in Geology. Will you, Prof. Ramsay, in handing to Mr. Croll this token of the interest with which we follow his researches, inform him of the additional value his labours have in our estimation, from the difficulties under which they have been pursued, and the limited time and opportunities he has had at his command.

Ramsay:Footnote 74

…thanked the President and Council in the name of Mr. Croll for the honour bestowed on him. He remarked that Mr Croll's merits as an original thinker are of a very high kind, and that he is all the more deserving of this honour from the circumstance that he has risen to have a well-recognized place among men of science without any of the advantages of early scientific training, and the position he now occupies has been won by his own unassisted exertion.

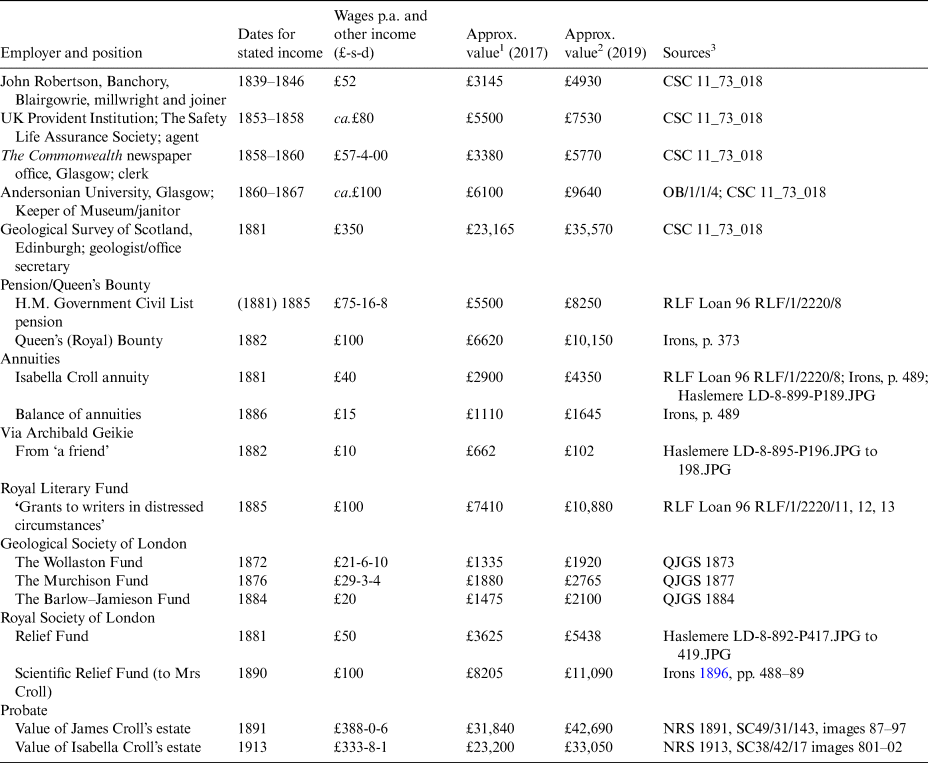

The Fund awarded to Croll was £21 6s 10d,Footnote 75 equivalent to as much as the considerable sum of £1920.00 at the present day (Table 2).

Table 2 Levels of income from selected employments and other sources for James and Isabella Croll, including probate (confirmation).

2 https://www.measuringworth.com/ (real worth option).

3 As follows: CSC = the National Archives of the UK (TNA), CSC 11/73, p. 018; Haslemere = Haslemere Educational Museum, Sir Archibald Geikie Archive; Irons = Irons (Reference Irons1896); NRS = National Records of Scotland – Wills and Testaments, Lanark Sheriff Court, images 801–802; OB = minute book, Andersonian Library, University of Strathclyde, 1860; QJGS = Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society; RLF = British Library Royal Literary Fund, Loan 96 RLF/1/2220.

On 18 February 1876, Andrew Ramsay was again empowered to convey an award to Croll by the President of the Geological Society, John Evans (a signatory for Croll's Royal Society of London nomination):Footnote 76

Professor Ramsay, –

Will you convey to Mr. Croll the Balance of the proceeds of the Murchison Fund, and at the same time express the hope of the Council of this Society that it may prove of service to him in the prosecution of those studies with which his name has been so long and so honourably associated.

His researches on Ocean Currents, on Glacial Phenomena, on the bearing of the latter on Geological time, and of both upon Climate, were generally known and appreciated, even before the appearance last year of his work on Climate and Time, in which the results of his studies are so carefully and ably expounded.

The author of that book would be the last to regard the subjects of which it treats as being all now definitely settled, and requiring no further investigation; and it is in the hope that his inquiries into the phenomena of glaciation, and into the physical causes conducing to extreme modifications of climate may be still further prosecuted, as well as in recognition of the valuable past labours of Mr. Croll, that the Fund which I place in your charge has been awarded to him.

Professor RAMSAY, in reply, said:

Mr. President, –

In returning thanks on behalf of Mr. Croll, I have no need to enlarge on the merits of a man so well known to geologists by his numerous memoirs, and now especially by his remarkable work, ‘Climate and Time;’ and though on a range of subjects so wide it is not to be expected that there should be no opponents to some of his views, there can yet be no doubt that the ability which he has displayed commands the universal respect of men of science and the adherence of not a few.

The Murchison Fund for 1876 carried a value of £29 3s 4dFootnote 77 – up to £2765 in ‘real wealth’ terms. This award alone would have been more than sufficient to cover the combined fees for his honorary LL.D., entrance to the Royal Society of London and his first annual subscription in the same year.

Croll's final recognition from the Geological Society of London came in the form of the Barlow–Jamieson Fund, which he shared in 1884 – his co-recipient being Charles Léo Lesquereux, a Swiss palaeobotanist who worked on the palaeofloras of Europe and North America.Footnote 78 Both workers received £20. The then President of the Geological Society, John Whitaker Hulke (1830–1895), surgeon and geologist, recorded:Footnote 79

The Council, in recognition of the value of Dr. James Croll's researches into the ‘Later physical History of the Earth,’ and to aid him in further researches of a like kind, has awarded to him the sum of £20…. Dr. Croll's work on ‘Climate and Time in their Geological Relations,’ and his numerous separate papers on various cognate subjects, including ‘The Eccentricity of the Earth's Orbit,’ ‘Date of the Glacial Period,’ ‘The Influence of the Gulf Stream,’ ‘The Motion of Glaciers,’ ‘Ocean Currents,’ and ‘The Transport of Boulders,’ by their suggestiveness have deservedly attracted much attention. In forwarding to Dr. Croll this award, the Council desires you to express the hope that it may assist him in continuing these lines of research.

The response came from Thomas George Bonney (1833–1923), Professor of Geology at University College London:Footnote 80

Mr. President, –

I have been charged by Dr. J. Croll to express to the Society his regret that his weak health and the great distance at which he resides prevent him from being present in person to-day to receive this award. He desires me to express his deep sense of the honour which is done to him in this renewed mark of the appreciation of his work, and he gives us the cheering news that though still at times suffering, he is now able to do a little work, a proof of which, in a paper on Mr. Wallace's remarks on the theory of Climate,Footnote 81 reached me yesterday. Deeply though I regret Dr. Croll's absence, I feel honoured in representing a man who has done such original suggestive and valuable work.

5.3. Collegiality and learned societies

It would seem that these accolades were based on Croll's written words rather than any standing attendant upon scientific meetings. He displayed an aversion to the communal gatherings characteristic of learned societies. His absence from these Geological Society events is instructive in this regard, as were his decisions to decline invitations to lecture at the Royal Institution in 1871 and the Victoria Institute in 1874.Footnote 82 This applied especially to the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In the Autobiographical Sketch, Croll mentioned the head pain which dogged his life and that

Another thing I was obliged to adopt, was not going out to public meetings or to dinner or evening parties…. During the thirteen years I was in Edinburgh, I remember of being only twice at a scientific meeting, and once at a concert.Footnote 83

This echoed the contents of two letters sent to friends where he is rather more expansive and open. The first was sent to the Rev. Osmond Fisher (1817–1914), a clergyman, geologist and early proponent of the liquid interior of the Earth, orogenesis and continental drift.Footnote 84 On 28 August 1871, Croll confessed:Footnote 85

I did not, however, attend any of the meetings or excursions of the British Association. There are several reasons for that. One is, I had exhausted my holiday time, and could not well leave the office. My chief reason, however, was that I dislike all such public displays. The truth is, I have very little sympathy with the leading idea of the British Association, viz., that science is the all-important thing. I don't believe anything of the kind. There are more noble and ennobling studies than science. You can hardly expect one who has devoted twenty years of the best part of his life to the study of mental, moral, and metaphysical philosophy to have much sympathy with the narrow-mindedness of the British Association.

Philosophy is just as real a part of human knowledge as science; and the time is, I trust, not far distant when this will be universally recognised.

This message is reiterated, though with greater candour, when Croll wrote to his lifelong friend the Rev. Dr James Morison (1816–1893), founder of the Scottish Evangelical UnionFootnote 86 following Morison's expulsion from the United Secession Church – demonstrably a man with form during a period when Scottish sect-making was not unusual. The letter from Croll was dated 17 August 1876:Footnote 87

…. The older I grow, the more disinclined I feel to go out to public meetings of any sort.

I have not been at a scientific meeting for upwards of half a dozen of years. The real truth is, there is a cold materialistic atmosphere around scientific men in general, that I don't like. I mix but little with them. There is, however, indication of a reaction beginning to take place towards something more spiritual in science; and the day, it is to be hoped, is not far distant when religion, philosophy, and science will go hand in hand.

Croll's animosity towards the British Association for the Advancement of Science might seem surprising. It was more inclusive than the Royal Society of London and allowed women to attend its meetings which took place in a different city every year. Croll was here declining to attend the Edinburgh meeting of 1871 and the Glasgow one of 1876. He had communicated two papers to its meeting in Cambridge in 1862,Footnote 88 but two invitations – one from the polymath Francis Galton (1822–1911) – to attend the Brighton meeting in 1872 and to contribute to discussion on ocean currents within the Geography Section,Footnote 89 met with rebuttal from Croll on the grounds of his health. Another reason may have been the planned presence there of William Benjamin Carpenter (1813–1885), who was also to be President that year of the Association. As it happened, Carpenter did not speak within the Geography Section, but he did deliver a paper within the Heat sub-section of the General Physics Section titled ‘On the general oceanic thermal circulation’ and another in the Geology Section ‘On the temperature and other physical conditions of inland seas, in their relation to geological enquiry’.Footnote 90 He also alluded to ocean research and the forthcoming Challenger expedition in his florid Presidential Address.Footnote 91 There was no mention of Croll in the available text from the British Association Report,Footnote 92 though Carpenter's intemperate reactions to the criticism of his ideas by Croll from around this time were evident elsewhere.Footnote 93

Apart from issues of health and a distaste of certain scientific people and gatherings, Croll professed that ‘[a]lmost from boyhood I had a love for retired, solitary walks in the country. On these occasions I can enjoy a congenial companion, but I would rather be alone to meditate’.Footnote 94 It seems likely that these inclinations, his modesty and perhaps his declaration, late in his life, of being ‘only a plain, self-educated man’Footnote 95 reflected a lifelong lack of confidence in his educational background. This may well have mystified some, academic or otherwise. Henry William Bristow (1817–1889), Director of the Geological Survey for England and Wales, wrote to Croll in 1877 indicating that he intended to gather those papers of his in his possession and ‘get them bound together in one goodly volume’; furthermore, he solicited Croll's photograph, which he would be ‘very glad to add to my own gallery of British worthies’.Footnote 96 Just over a decade later, Sir Robert Stawell Ball (1840–1913), then Professor of Astronomy at Trinity College Dublin and Astronomer Royal for Ireland, wrote to Croll that he felt ‘much honoured by you having chosen me as the one you have applied for an answer to your query.’Footnote 97 Prior to these, the Rev. John Cunningham Geikie (1824–1906), a writer of popular religious books, wrote to Croll having read his paper on molecular motionFootnote 98 ‘with equal delight and instruction’:Footnote 99

Why don't you come to the front more? A man with your brain and power of expression might do pretty much what he liked in making a name for himself in scientific matters, and in serving his day.

One can only guess at Croll's reactions to adulation – perhaps discomfort rather than any satisfaction that he took from some of the academic honours accorded him?Footnote 100

6. Money, pension and controversy

Money problems – real or imagined – run through Croll's life story and have been mentioned above (section 1). His various salary levels for which information is available (Table 2) show a progression, other than for an interlude with The Commonwealth newspaper, culminating in what would be considered a very reasonable income (£350 p.a.), for the time, in the offices of the Geological Survey. The average salary for an adult male clerk in the UK during the 1880s was in the order of £50 p.a.Footnote 101 As we have seen in the census records for 1861 and 1881 – though not an unusual event – the Croll's were able to afford domestic help and in 1871 they seem to have been supporting both Croll's brother David and his wife's niece Anabella. This is somewhat at odds, for his time in Glasgow at least, with his perception that ‘[m]y salary was small, it is true, little more than sufficient to enable us to subsist.’Footnote 102

Croll's early retirement at the age of 60 years brought a sharp reduction in his annual income to £75 16s 8d along with a £40 p.a. insurance annuity he had settled upon his wife (see below and Table 2). His pension represented 13/60ths of his salary with no allowance being made for his forced retirement occasioned by ill health. Greater generosity had been shown to two assistant geologists with the English and Irish Surveys who had been disabled for duty around the same time and this clearly rankled with both Croll and his biographer. Archibald Geikie drew up a memorial (a statement of facts as the basis of a petition) in 1881 on his behalf, which was signed by a substantial number of leading dignitaries, politicians and scientists. The memorial was submitted to William Ewart Gladstone, the Prime Minister, in the hope that Croll would be granted an enhanced pension from the Civil List. This was not successful, although he was granted £100 from the Queen's (or Royal) Bounty, an obscure source of income under the patronage of the Prime Minister.

In 1883, another effort was made ‘by my friends’Footnote 103 to secure more retirement income – though clearly with much letter writing on the part of Croll and advice from Irons.Footnote 104 The second memorial, with even more supporters (153 vs 128), was presented to the ‘Lords of the Committee of the Council on Education, Science and Art Department’. There was a large measure of overlap of individuals between the two submissions. Writing to Irons on 3 January 1883, Croll had cautioned, ‘[w]e must not append too many names, but first-rate what there are. A lot of commonplace men would weaken the memorial.’Footnote 105 The lists of supporters for these two efforts are extraordinary. Taking the 1883 memorial and treating the following numbers as minima,Footnote 106 there were five peers, 13 knights, 35 Members of Parliament, 12 Chancellors, Vice-Chancellors or Principals of universities, 74 professors, 85 and 30 Fellows of the Royal Societies of London and Edinburgh, respectively, and 12 Presidents or Vice-Presidents of both national academies and other major learned societies. Of special note is the Poet Laureate Alfred Tennyson (1809–1892) who had interests in geology, biology and evolution,Footnote 107 the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) and the forthcoming Prime Minister, the Third Marquess of Salisbury. In terms of academic disciplines represented by signatories, these included 19 geologists, 19 members of the medical profession, nine each of physicists, chemists and biologists and six astronomers. Wallace had written to Croll on 13 January 1883, declaring that ‘I have much pleasure in signing your memorial, and sincerely hope you may be successful, as 1 think you have been very badly treated.’Footnote 108 This second approach was even less successful than the first and Croll was granted nothing.

Why was Croll unsuccessful? Irons offers a range of acerbic commentary:Footnote 109

the shabby behaviour of the British Treasury towards one of its servants; while favourable treatment was meted out to the English and Irish assistants (‘two inferior men…who had not a tithe of the claim to recognition which he had’); the Scotch geologist…the most eminent scientist on the staff of the Geological Survey Office, was, by her Majesty's Treasury, ruthlessly plunged into poverty; Probably, had Croll been a popular retailer of other men's scientific discoveries, a studious member of a foreign royal family, or a well-recommended, although already highly-paid public servant, he would have received a liberal allowance from the Civil List; but…the British Treasury thought fit to refuse him his just reward, and left him and his wife to subsist, or rather starve, on a beggarly allowance of £75 per annum.

Perhaps most surprising for a lawyer was Irons's virtually libellous naming of a supposedly central culprit:Footnote 110

…it is believed that for this, as for other facts, there was a cause. It has been hinted that a somewhat popular scientist, some of whose current theories Dr. Croll had vigorously and too successfully assailed, had prejudiced the Prime Minister [Gladstone – for the first memorial] against his assailant. We cannot for a moment believe that the Premier would listen to any paltry, untrue, and absurd charge of agnosticism or atheism brought against Dr. Croll; but we do sadly fear that he did not himself understand his brilliant contributions to geological science, and that, in an evil hour, he listened to the detractions of a prejudiced, or, perhaps, even spiteful man. Accordingly we are persuaded that the appeals made to the Government on Dr. Croll's behalf were never fully considered on their merits.

This is clearly an allusion to William Carpenter, with whom Croll had conducted the heated debate on ocean currents (section 5). Carpenter's religious beliefs emphasised actions of God as observable but not necessarily fathomable by empirical, inductive study. This was in opposition to Croll's belief in the existence of physical principles, albeit set in train by divine action, and capable of being elucidated by intellectual process. Unlike Croll, Carpenter was an establishment figure – Professor of Physiology at the Royal Institution, subsequently Registrar of University College London, President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science for 1872 and appointed as Companion of the Order of the Bath upon retirement.Footnote 111

Whatever the reasons behind Croll's failure with his memorials, some financial assistance was forthcoming. While living in Hamilton, Lanarkshire, he applied to the Royal Literary Fund. In a letter dated 20 April 1885 outlining the case for an award, Croll reiterated his medical afflictions, but also provided some interesting information:Footnote 112

…owing to disease of the heart, paralysis, and pain in the head, from which I have long been suffering…I memorialized the Committee of Council on Education for an increase…[who] recommended it…but the Lords of the Treasury declined to alter their award.

…I have to pay assurance premium, subscription to the Royal Society, and some other burdens…. This [income], I find, barely meets the necessities of life…. I may state that my writings have never afforded me a source of income…on the whole, have proved a loss rather than a gain to me.

It is intriguing to learn that the Council had supported his case and that he felt the subscription to the Royal Society (£4) was a necessity in retirement – the need for such imprimatur stayed with Croll to the end of his life.Footnote 113 One of his advocates to the Literary Fund was Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817–1911), Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew:Footnote 114

The remarkable researches and writings of this author, are so well known and so highly appreciated…though strictly scientific, they have so wide a grasp, and throw so novel and important a light on the history of our planet – (far beyond the ‘prehistoric’ and ‘geological’) …

Mr Croll's circumstances are harrowing in the extreme and a source of great and continued anguish to all his friends.

…Dr Croll…a most honourable and original thinker and writer, the result of whose labours, like those of Mr Darwin, I find referred to in the lightest as well as the more solid literature of the epoch.

Notwithstanding the fact that Hooker was a sponsor in Croll's nomination for Fellowship of the Royal Society and a great friend of Darwin, this constituted a persuasive endorsement. Another reference was submitted by his former employer, Archibald Geikie, ‘as one of the Stewards of the Fund this year’ and who wished to support the application ‘as strongly as I can’.Footnote 115 Although positive, and perhaps hinting at the encouragement Croll may have received in applying to the Fund, Geikie's letter was formulaic. It was dated 11 May 1885 and it presumably arrived on or close to the date of the funding committee's deliberations given that Croll was notified of his award of £100 by letter on 15 May 1885.Footnote 116

Irons notedFootnote 117 that for five years Croll had moved about:

from place to place in an unsettled condition, with no permanent home…. Having during the time obtained, through the kindness of friends, a little increase to his income, he…naturally gravitated to the quiet, ancient city of Perth, near his own native place, and was fortunate in obtaining a lease of a comfortable house in the suburbs of the city. At the end of the summer of 1886, he accordingly took up his permanent abode there.

The sources and amounts of the assistance that enabled his resettlement in Perth are largely anonymous. Several years prior to this, however, Archibald Geikie wrote in a letter to Croll:Footnote 118

I enclose [–] a cheque for £10 from a friend who desires his name to be concealed. He begs me to entreat your acceptance of it and says that I am to let no one know anything about this trade, adding by way of joke – ‘say it comes from a Yankee publisher as conscience money for stealing one of his [–]’!!

There would also appear to have been helpful support from both Geikie and Joseph Hooker:

Dear Sir Joseph Hooker

Some time ago you spoke to me of the interest you took in poor Dr. Croll. I hear this morning that he is doing his utmost to get as much money together as will enable him purchase an annuity of £40 or £50 and that he has been to some extent successful….Footnote 119

My dear Croll

…. The Royal Society to show its sympathy with you has cancelled your annual subscription. This is done in the most sympathetic and kindly way, and you may accept the proposal without in the least losing your self-respect.

Lastly, I have made application to the Scientific Relief Fund of the Royal Society for a grant in your favour and I have a very kind and hearty letter from HuxleyFootnote 120 about it this morning…. I have been in communication with Sir Joseph Hooker about these various matters. He has accounted[?] himself most chivalrously on your behalf….Footnote 121

Only a matter of days after Croll's death, his lifelong friend George Carey Foster was able to inform Isabella that the Royal Society Scientific Relief Fund Committee had awarded her £100.Footnote 122 It is unknown whether this considerable success (Table 2) was repeated in 1897 when Irons received a dictated ‘private’ letter from 10 Downing Street from Arthur James Balfour, First Lord of the Treasury in the Marquess of Salisbury's government and a future Prime Minister.Footnote 123 Balfour was ‘glad to consider whether anything ought to can be done for Mrs Croll.’ The strikethrough of the word ‘can’ is perhaps an inadvertent survival of the letter-writing process (i.e., the person taking dictation did not wish to rewrite the letter, and/or Balfour, if he was aware of the revelation, did not think it important enough to obscure) and it provides an insight into the possible lack of intent on the part of its author.

The value of the estates upon death from both James and Isabella (Table 2) do not necessarily reflect liquid assets, although in the case of Isabella, then resident in Lanark, it was close at £318 8s 1d. For James Croll the figure was £260 13s 0d. The balance in both cases consisted of furniture, other than £5 for James's ‘interest in the copyright of his literary works’. The cash available to Isabel upon her husband's death was about three and a half times the value of his annual pension.

7. Friendship and sentiment

James Croll may have experienced money problems, but ‘[o]ut of his scanty means he liberally gave to relieve distress’.Footnote 124 This would be consistent with the view that ‘[f]ew men more thoroughly enjoyed the society of friends’Footnote 125 and that ‘[h]e was warmly affectionate, strongly attached to relatives and friends.’Footnote 126 He himself does not say much about friendship other than telling us that ‘Mr. David IronsFootnote 127…proved to be one of the kindest friends I have ever met with in life’ and, as already seen, that ‘[t]he union [with his wife] has proved a happy one. She has been the sharer of my joys, sorrows, and trials’.Footnote 128

We do learn that he had ‘a modest, shy, dry, and almost speechless manner, except on occasions when he was drawn out by congenial conversation among real friends’, and he certainly maintained the ‘faithful’ friendship of George Carey Foster, ‘a constant correspondent’, as was Andrew Ramsay who ‘never lost any opportunity of doing Croll a good turn.’Footnote 129

Extended reminiscences are provided by two church ministers. The Rev. George C. Baxter of the Free Church in Cargill wrote:Footnote 130

Our connection arose from his belonging to this district. In making one of his visits to this scene of his earlier years, his affection for which he never lost, he called on me here at the manse, and from that time he was accustomed every year, during the two or three years preceding the last seven of his life, to come and spend a day with me, visiting the scenes of his childhood. These days were to me days of great enjoyment, both from the kindliness and geniality of nature characterising Dr. Croll, and from the originality, intellectuality, and power attaching to his conversation. I can still recall the interest of his various references to the great theory of the secular changes, the interest attaching to his description of the Glacial period, and its effects on this locality in particular. I can remember how passionately he declared his preference for metaphysics over physics, and his intention, if spared, to return to what he called his first love, and the intimation he made to me of his being at that very time engaged on a study of Kant, with a view to ultimate publication of his views…. He was wont to revisit, at such times, the cottage still standing, in which he spent the years of his childhood and earlier manhood. Looking round with searching eyes on the old familiar walls, I remember his remarking, as his eye fell on the window of the chamber, ‘And there are the very shutters I made with my own hands’; and, stepping up to them, he opened and closed them fondly. A mantelpiece of wood also that remained from these days, and was an original contrivance of his for suspending the ‘crusie,’ [oil lamp] he pointed to with loving interest and remarked on its survival…. At another time, on my asking if any of his old playmates and friends remained in the village whom he might go and see to revive old memories, he inquired after several, all gone, till at last he mentioned the name of Robert Young, an intelligent tailor still surviving in Wolfhill. I said, ‘Robert is yet alive, we will go and see him.’ On arriving at the door of the house, it was opened to my knock by Robert himself. I pointed to Dr. Croll and said, ‘Do you know this gentleman, Robert ?’ ‘No,’ he said hesitatingly, ‘I do not.’ ‘This is Dr. Croll,’ I said. ‘Ay, ay?’ he at once responded, his eyes sparkling with delight. ‘Jamie Croll, Jamie Croll’; and the two proceeded to live over again the days of their boyhood….

While the Rev. David Caird of the Congregational Church in Perth recounted:Footnote 131

One other thing I should like to add. In the closing months of his life Dr. Croll found great delight in going back by way of reminiscence on his early days. He spoke with deep gratitude of his home, of the faith and devotion of his father, of the wise and gracious Providence that had shaped his own destiny, of the love of many friends which had ever been to him a sacred treasure…there comes back with a strange, deep pathos the memory of a forenoon when he went for the keys of the old building in Mill Street, and, opening it with his own hand, went and sat for a little while in the seat in the gallery which his father used to occupy when he himself was a boy. Nor was this mere sentiment. It was one of the last acts of a true man who loved to trace back to its source the main stream of influence which had made him what he was….

The Rev. Osmond Fisher was to say of Croll that ‘[d]uring an intimate acquaintance of over forty years, the writer never once saw his temper even ruffled’,Footnote 132 but Croll felt moved to write less charitably to George Carey Foster concerning his oceanographic adversary (sections 5.3 and 6):Footnote 133

When you find leisure to read my reply to Dr. Carpenter, I need hardly say that I shall feel glad to get your opinion on the subject in a few lines. You may rest assured that I shall never follow Dr. C.'s example, and blab out to the world what my scientific friend may think of my views. If they cannot stand without such subterfuge, let them go to the four winds of heaven.

A milder reaction to a perceived misconception is contained within an account of an excursion on 20th April 1867 to Blairdardie Clayfields, Glasgow, recounted by his geologist friend James Bennie:Footnote 134

The day was fair, but not bright, the sky being full of loose watery clouds which threatened rain perpetually…. As Mr. Croll had a horror of rain, and would not go out in it, I was frightened throughout the day by every dull blink that occurred…I found Mr. Croll's ‘crack’ good, quiet, undemonstrative, but full of pith and power. I cannot remember half of what he said, but the impression that remained was that he was a close observer and deep thinker on those objects he had seen or those subjects he had thought upon, but he was not cosmopolitan in the extent of objects nor encyclopædic in the range of subjects, as, indeed, in this age, when knowledge fills the earth as the waters fill the sea, nobody can be…. Having Mr. Croll with us, our talk naturally drifted in his direction; and we discoursed of the eccentricity of the earth's orbit and its climatic effects as intelligently as we could…. Mr. Mahony quoted some London review or paper in which Mr. Stone was alone spoken of as having calculated the eccentricities, when Mr. Croll said in the quietest tone possible that it was an error, and that instead of Stone the paper should have said Croll, meaning thereby that it was himself that had done what Mr. Stone was getting credit for….

No passion was evinced, no jealousy was disclosed, no chagrin even seemed felt by him at his honour being given to another. But, as if he was simply correcting an error in arithmetic or a lapsus linguæ he substituted his own name for that of the other, and it was done.

…according to Mr. Croll, Leverrier had appropriated without acknowledgment the discovery of a comet-like orbit for the meteoric bodies which have a periodic term of 33 years, giving it forth as his own entirely, whereas it had been discovered or elaborated by a Roman astronomer some time before.

Impressions of Croll's relationship with a friend and work colleague are provided further by his correspondence with Benjamin (Ben) Peach. In a series of letters spanning the period August 1870 to March 1878, we can see a light-hearted side to Croll:

I am certainly the laziest fellow on the face of the earth for I have not yet gone to see the shell mound.Footnote 135

To open the eyes of yo[ur] post man I have sent the maps round the biggest stick I could find.Footnote 136

I was not a little surprised at your announcement of Etheridge's marriage. He is hardly so open minded as most English men or I should have heard something of it.

Is it true that our friend Skae is to be married shortly? I heard something to that effect. It is time that Horne and Jack were looking out!

…I should be glad to do a little for you. I sometimes run out of work for the office.Footnote 137

Many many thanks for your kindness. Your report is all that could be wished for or required. Thanks for your kind inquire. I am still grumbling away as usual.Footnote 138

I am very sorry to hear that Mrs Peach has been so poorly. I had not heard of her illness. I am glad however to see by your letter that she is improving. Take care of east winds.

Thanks for your kind enquiries after my health. I am pretty well although still grumbling away about my old enemy.Footnote 139

Finally, Irons reported a visit made by a Mr Paton to Croll two days before he died. The effort of speaking:

brought on a fit of coughing, to relieve which he was getting whisky in teaspoon measures. In that connection he made almost the only little joke I ever heard him utter. ‘I'll take a wee drop o’ that,’ he said. ‘I don't think there's much fear o’ me learning to drink now!’Footnote 140

8. Conclusions

As well as eulogising Croll, James Campbell Irons ended the main section of his memoir with a statement that he was ‘one of nature's noblemen’.Footnote 141 The biographer saw this as a paean to Croll's combination of such characteristics as intellect, generosity, industry, faith and serenity in the face of lack of privilege and his infirmity and misfortunes. This paper has not sought to provide an adulatory account of Croll, but rather to examine selected areas of his life. These contribute, arguably, to an understanding of Croll as a person and look beyond the areas of science and religion addressed elsewhere in this volume.

It seems clear that Croll was grounded geographically, historically and spiritually in his home area and that the course of his life was reflected strongly in such influences. An advantage of self-education and independence of thought was a willingness to think things through from first principles. Scientifically at least, this resulted in novel critiques and findings and their wide appreciation by the ‘natural philosophers’ of the day. The achievements which brought him recognition from the world of science did not translate, in his mind, into institutionally mediated financial reward from the State. In addition, his experience of lifelong poor health must have acted as a constant, debilitating burden, which, accentuated by perceived financial woes, were made bearable by the support of his wife and his deep faith.

It would appear that Croll felt most comfortable with his family, religious friends and work colleagues who seemed to hold him in awe and esteem. Those colleagues were primarily field geologists, empirically orientated and not theoreticians. For many years he held the admiration of renowned men of science, but he obviously found learned societies and opponents of his scientific ideas sometimes unpalatable. He was not a clubbable individual and he avoided such associations in favour of those with a religious bent and with whom intellectual engagement was primarily via his writings. Life may have thrown up ‘trials and sorrows’,Footnote 142 but it seems clear from the affection and respect accorded him that many looked upon James Croll as a ‘man greater far than his work’.

9. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following for assistance with archival services: British Geological Survey, Keyworth (Andrew L. Morrison); the British Library (Western Manuscripts); Andersonian Library, Archives and Special Collections, University of Strathclyde (Anne Cameron); The National Archives, Kew (Paul Johnson); Haslemere Educational Museum, Sir Archibald Geikie Archive (Robert Neller); Imperial College London, Records and Archives; Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Johns Hopkins University (James Stimpert). Jamie Bowie (Aberdeen) is thanked for cartographic assistance. We are grateful for comments from Ian Ralston and Caroline Wickham-Jones, which encouraged us to clarify various points in an earlier version of the paper.