The late nineteenth and twentieth centuries witnessed the unprecedented intensification of global connections and exchanges (as well as inequalities) following the spread of capitalism and colonialism. As Tani Barlow puts it, ‘colonialism and modernity are indivisible features of the history of industrial capitalism’.Footnote 1 In the past three decades, scholars across disciplines have further shown that colonialism, modernity, and capitalism are not monolithic temporal and spatial ventures.Footnote 2 Building upon the scholarship on the diverse forms and modes of colonial processes, this article explores how experiences of colonial modernity were constituted through global advertising by examining the marketing of Hazeline Snow, a medical-cosmetic product of London-based pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome Company (BWC), in early twentieth-century India and China. As a globally circulated medical-cosmetic commodity that showcased the advance of colonial modernity,Footnote 3 the transnational advertising of Hazeline Snow both responded to and fashioned changing notions of beauty, health, and race in the local markets. It thus offers an instructive window into the ways in which capitalism shaped yet also adapted to different colonial modernities. Tracing the lives and afterlives of Hazeline Snow, in two regions in Asia that were either under colonial domination (in the case of India) or experienced persistent fears and anxieties of being fully colonized (like China),Footnote 4 the empirical findings of this comparative study ultimately gestures towards a kind of ‘Asian modernity’ in the early twentieth century. This ‘Asian modernity’ was not derivative or imitative of the West alone, but was shaped by inter-regional commercial and ideological flows of goods and media and multiple forms of imperialism across Asia. The benefits of taking this comparative, commodity-centred approach are manifold: first, inspired by the colonial modernity framework, our broader conception of Asian colonial modernity continues to stress the need to situate the modernization project in China within the broader history of imperialism even though it was not subjected to the same form of colonialism as India.Footnote 5 Second, it emphasizes the significance of different colonialisms in the tensions between homogenization and heterogenization during the process of globalization.Footnote 6 Recent scholarship of consumer culture and advertising in India and China has addressed the dynamics between the ‘foreign’ and the ‘indigenous’, the ‘modern’ and the ‘traditional’, as well as the ‘global’ and ‘local’ in early twentieth-century commodity and urban culture.Footnote 7 As the ‘global’ and the ‘local’ have been widely acknowledged to be mutually constitutive and the line between the ‘modern’ and the ‘traditional’ never clear-cut, we contend that a generalized ‘West’ should not be treated as a synonym for the ‘global’ and highlight, in this article, the impact of different colonial processes in creating, maintaining, disseminating, and even subverting knowledge systems that were products of Asian as well as global exchanges. BWC’s marketing of the Hazeline brand in India and China had to contend with not only local manufacturers of similar toiletries and beauty products, but also faced challenges from Japan. Colonial influences of advertising and consumption came not just from Britain but also from imperial Japan’s construction of colonial modernity prior to the Second World War.Footnote 8 Using such a comparative lens and the practice of ‘multidirectional citation’ helps us to better understand the co-existence and competition of multiple and often mutually constitutive modes of colonial modernity across Asia.Footnote 9

Historians have certainly employed comparative methods to study the gendered nature of consumption, globalization, and modernity. The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group, for example, has used the Modern Girl figure who appeared in globalizing markets cutting across national boundaries to show ‘mutual influences and nonlinear circuits of exchange’.Footnote 10 Yet this exclusive focus on the Modern Girl figure also results in a blind spot: namely, her male counterpart, the Modern Boy. Shifting the focus from an advertising icon to a more commodity-centred approach uncovers distinctive gendered expressions of colonial modernity that have been previously overlooked. In Hazeline Snow advertisements, while the Modern Girl – be it Indian, Chinese, or European – was indeed a ubiquitous icon, we found ample examples of Chinese advertisements featuring young men and marketing specifically aimed at them.Footnote 11 Our attention to the Modern Boy is also where we divert from Barlow’s formula of colonial modernity: claiming that ‘men rarely figure into advertising’, the key point of Barlow’s colonial modernist frame was that the ‘other’ of the Modern Girl figure was not a man but the branded commodity itself.Footnote 12 While not denying the centrality of the sexualized female figure in modern commercial advertising, this focus on the girl-commodity/commodity-woman relationship as the epitome of modern consumer culture needs to be put to further empirical testing. Treating ‘race’, ‘beauty’, ‘femininity’, and ‘masculinity’ as inherently unstable concepts whose meanings were constantly in flux, we are interested in the historical emergence of such concepts in different colonial contexts. Bringing the analyses of Republican China and colonial India together into a comparative frame helps us to destabilize familiar terms by highlighting the historical – or in some cases, historically contingent – roots of their invention and evolution.

This article begins with a brief account of the history of BWC, followed by detailed analyses of the advertising history of Hazeline Snow in India and China, focusing on the commodification of science and beautification and depictions of race and gender in advertising campaigns. Our understanding of Asian modernity also considers multiple colonial visual orders that depict future possibilities in local and foreign advertising, including that of female and male embodiment and modern consumption and pleasures.Footnote 13 The analysis then teases out some of the ways in which consumers and local entrepreneurs responded to the Hazeline brand to show how ‘Snows’ became an Asian beauty product in their own right.

I

The global marketing of BWC’s Hazeline Snow, which first appeared on the market in 1892 as a medicinal skin cream, needs to be understood within the wider historical context of the expansion of capitalism and imperialism since the late nineteenth century. BWC was established in London as a pharmaceutical company by American pharmacists Silas Burroughs (1846–95) and Henry Wellcome (1853–1936) in 1880. Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries actively promoted science and its application in industry, yet commercial enterprises such as BWC faced certain prejudices. Professional practitioners objected to commercial-driven research, while some medical men saw new scientific developments as intruding on their traditional skills.Footnote 14 Despite such challenges, BWC opened a series of research laboratories in the late 1890s, quickly attaining the reputation of a commercial company conducting serious scientific research.

In various ways, British imperialism underpinned BWC’s guiding motto of ‘Science and Industry’.Footnote 15 Claiming that ‘Mr. Joseph Chamberlain has taught the nation to think Imperially – Burroughs Wellcome & Co. work Imperially’, BWC aimed to rival and surpass foreign pharmaceutical, in particular German, production.Footnote 16 To this end, Burroughs worked to construct a network of agencies and overseas trade until his death in 1895.Footnote 17 BWC’s commercial sponsorship of the Universal Races Congress, held at the University of London in 1911, further underlines how the commodification of imperial medicine was at the heart of the BWC project. While BWC’s souvenir pamphlet for congress participants expressed an idealistic universalism in its illustration of a handshake between ‘EAST’ and ‘WEST’ with a caption underneath stating that ‘a time shall come when all men shall meet as brothers’,Footnote 18 its marketing of colonial health commodities was deeply racialized. BWC pitched products such as first-aid kits to colonial travellers that would help the white European body stay healthy as they made ‘discoveries’ in ‘out-of-the-way districts’, thus espousing familiar messages about degenerative races and the dangers that European (and American) bodies faced in tropical locations.Footnote 19 Overall, BWC’s marketing practices aligned with how imperialists of the 1890s represented personal-care products as mediums through which English power could be extended into the colonized world.Footnote 20

BWC, at first, did not consider India and China to be promising markets. In 1882, Burroughs noted that potential consumers in both markets were small because of the (in)affordability of pharmaceuticals, prejudices against foreign medicine, and preferences for native doctors, priests, or ‘quacks’.Footnote 21 As a result of such scepticism, BWC initially targeted only the European population in India, such as government employees and missionaries, and distributed its products primarily via governmental networks.Footnote 22 On the other hand, some non-European populations in India did also use and recommend Hazeline products even though they were not the initial target consumer base. In her 1916 domestic manual Hifz-i-Sihhat (Preservation of health), the Begam of Bhopal, Sultan Jahan, for instance, had endorsed the brand to elite and middle-class women, many of whom would be under purdah (sartorial and spatial segregation). She recommended Hazeline Snow and Hazeline Cream be applied to provide care, cleanliness, and gloss to dry lips, highlighting the interdependency of conceptions of health and beauty and related usages.Footnote 23 As trade began to flourish in India at the turn of the twentieth century, BWC eventually opened its Indian branch in Bombay in 1912.Footnote 24 Advertisements for Hazeline products in Indian mass print first appeared in the interwar period. Early 1930s Hazeline advertisements, which explained that it should be used as part of a cultivated daily routine, generally only featured the product itself rather than situating Hazeline Snow alongside a Modern Girl (Figure 1).Footnote 25 It was not until the early 1940s that the Modern Girl icon began to occupy Hazeline Snow advertisements in the Indian press accompanied by a visual shift from heavy text to larger images.

Figure 1. ‘Hazeline Snow’, The Hindu, 22 Oct. 1930.

In contrast, BWC did not channel its products through the local Chinese government, possibly because British imperialism did not politically take hold in mainland China in the same way as it did in India. Instead, BWC in China launched mass media marketing campaigns from the beginning of its entry into the Chinese market. The company transformed its Shanghai depot into a branch in 1908, and, in the same year, advertisements for Hazeline Snow made a steady appearance in the Chinese press until the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937 disrupted its marketing campaign. Unlike in the domestic market, where BWC initially refrained from directly advertising to the British public to differentiate itself from suppliers of patent and quack medicine, BWC’s marketing strategy in China always aimed to engage with the urban reading public.Footnote 26 Like in India, early Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements featured only the product itself and adopted a text-heavy format, which was a common style in black-and-white Chinese newspaper advertisements in the early twentieth century (Figure 2).Footnote 27 Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements started to incorporate human figures into their advertising designs from the mid-1920s, decades earlier than the debut of the Modern Girl in Indian Hazeline Snow advertisements. The mass media marketing of Hazeline Snow in China proved to be quite successful. A Chinese reporter observed in 1918 that ‘due to the huge number of people in Shanghai using Hazeline Snow, it has been sold out everywhere for two months’.Footnote 28 It was so popular that ‘Snow’ became a generic term for a particular kind of vanishing cream (xuehuagao). Before the entry of Hazeline Snow into China, the term xuehuagao had never been used. The popularity of Hazeline Snow in colonial India similarly led to the emergence of generic ‘Snows’ there, which will be discussed further below.

Figure 2. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Shibao, 17 Nov. 1911.

BWC’s global marketing of Hazeline Snow hinged on the transformation of science into marketable commodities. ‘Science’ – defined by parameters set by development in Anglo-American and European regions (a generalized ‘West’) – was central to Hazeline Snow advertisements. In both India and China, BWC advertisements concentrated their efforts on protecting the brand name, relying predominantly on the brand’s history as a reliable, high-quality brand, and the authenticity and scientificity of Hazeline. The ‘stars’ approach was widely adopted in toiletries and cosmetics advertising in early twentieth-century India and China. From the 1930s in India, the glamour and appeal of early Indian stardom was combined with cultural elements as actresses were approached to endorse products such as Lux beauty soap and Pond’s creams, to the extent that Lux beauty soap became the complexion soap of stars.Footnote 29 Market researchers of Lever Brothers (LB), manufacturer of the popular Lux brand, observed a rise in the popularity of ‘Native Stars’ over European or American film stars.Footnote 30 The signing of Leela Chitnis in 1941 was a significant turning point for LB in the use of the star appeal of the Modern Girl.Footnote 31 Lux girls from the Indian film industry, later featuring in Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, suggest the wider trans-regional appeal of Indian cinema across the region.Footnote 32 Such companies also advertised localized models of preferred modern conjugality to appeal to the middle-class Indian housewife.Footnote 33 Chinese cosmetics entrepreneurs such as Chen Diexian similarly sought public association with high-profile Chinese film stars to boost the publicity of their brands.Footnote 34 BWC, however, adopted a more product-centred approach over the popular ‘star’ approach in many of its colonial markets. In India, unlike its London-based competitor Oatine Snow, which depicted dialogues between a woman and her husband as an admirer of her soft, beautiful, and fair skin, Hazeline only featured women (initially European, then increasingly Indian women from the 1940s) or centred the item (in a package, tube, or bottle) with accompanying text. Indian ad copy usually employed a language of product satisfaction and quality assurance – for instance, by using the term itminan, meaning satisfaction and assurance, in Hindi and Urdu.Footnote 35 BWC also aimed to reassure consumers of its credibility against imitations and other brands by transliterating the word ‘trademark’ into its vernacular advertising. In light of Hazeline Snow’s early success, this marketing strategy attempted to reinforce long-standing brand recognition of Hazeline as an authentic, high-quality product against a burgeoning market of ‘Snows’.

Chinese advertisements for Hazeline Snow similarly focused on its scientific superiority over domestically produced facial creams.Footnote 36 ‘Science’ became a crucial differentiator between genuine Hazeline Snow and imitations. Some Hazeline Snow advertisements devoted themselves solely to educating Chinese consumers about the inferiority of imitations, the importance of recognizing the Hazeline Snow trademark and, by extension, its scientific authenticity and authority. Chinese consumers were warned that ‘fakes’ would damage the user’s skin, and that authentic Hazeline Snow ‘embodied the essence of science’.Footnote 37 Although such advertisements explained neither what made Hazeline Snow ‘scientific’ nor the meaning of ‘science’, this reiteration of the scientific and supreme quality of Hazeline Snow was well received among the local audience. Books on the manufacturing of xuehuagao generally admitted, in a slightly frustrated demeanour, that most domestically made xuehuagao were not as high-quality as foreign brands such as Hazeline Snow and not yet able to compete with them.Footnote 38

This valorization of science is one moment that signalled some global synchronicity in the early twentieth century. As BWC gradually expanded into overseas markets beyond Europe, it accelerated the commodification of science in places like India and China through the global circulation and marketing of commodities. Yet BWC was just one of many foreign companies, and local actors did not simply react to and adopt knowledge systems developed in the ‘West’. These forms of knowledge did not spread smoothly from one site to another and find ‘vernacular’ forms. If ‘science’ in Hazeline Snow advertisements invariably referred to ‘Western’ science, the commodification of beautification varied more distinctively in India and China.Footnote 39 We now move to a close reading of the different priorities in Indian and Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements. While fair skin became a desirable beauty standard in both India and China (as well as in Britain), the interpretation of what ‘fairness’ means was rather different. The concept of fairness was much more heavily racialized in the Indian context than in China.

II

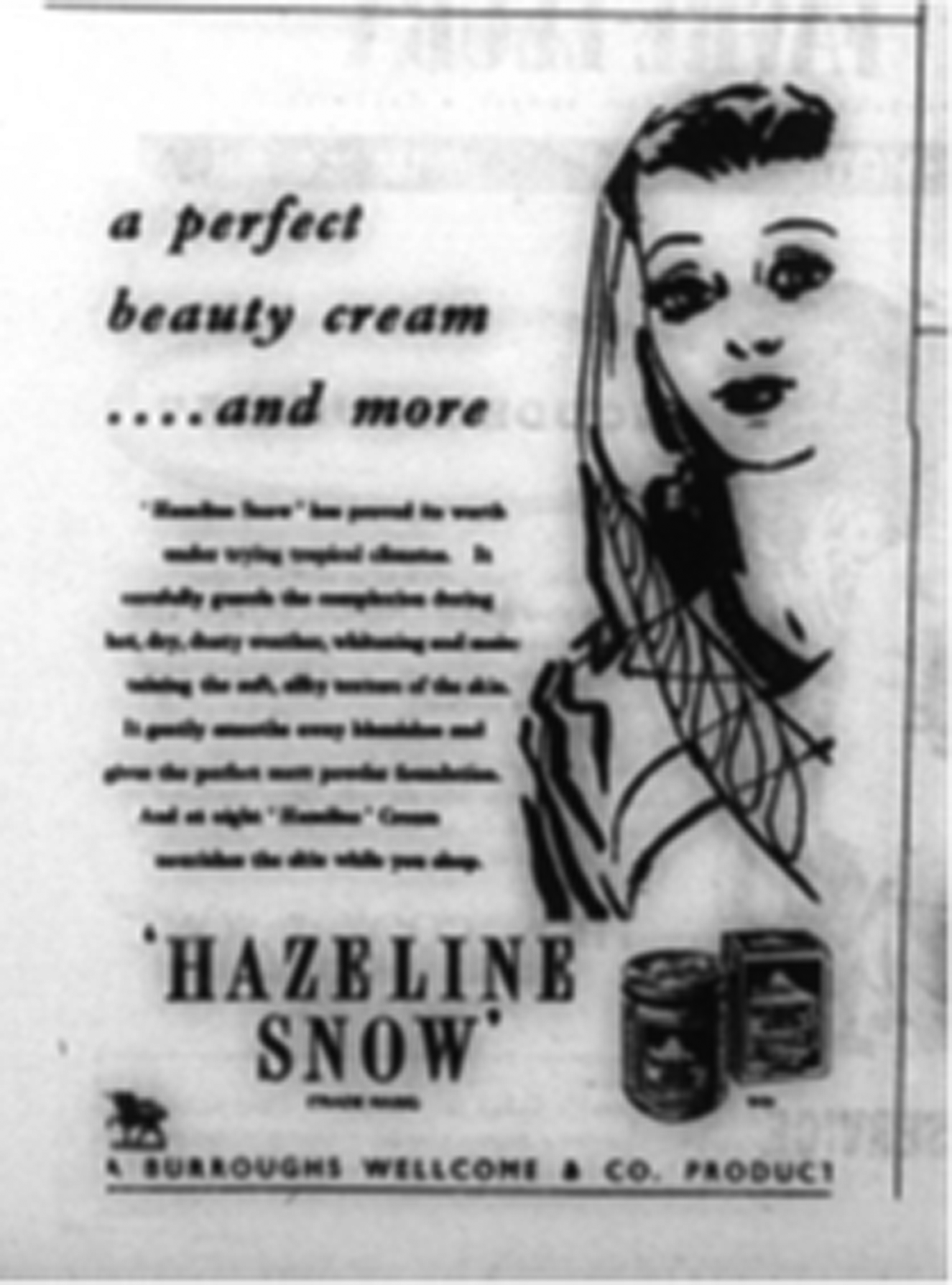

Though Hazeline Snow maintained its ambiguous identity between being a medical cream and a cosmetic cream, it was increasingly seen as a beautification product in Britain and its overseas markets.Footnote 40 By the 1930s, the language used in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements progressively gravitated towards its beautification function: in advertisements targeting the middle-class female consumer, Hazeline Snow was always called a ‘cosmetic product’. Figure 3, for instance, declared that Hazeline Snow was a non-greasy cosmetic cream that worked as a perfect powder base.Footnote 41 Similarly, in India from the 1920s, a new generation of urban middle-class consumers were ‘redefining parameters of the modern’ by responding to lifestyle goods in Indian markets.Footnote 42 By the late 1930s and 1940s, the Hazeline brand was consistently advertised in both English and vernacular language press across India as cosmetic creams and skin-whiteners (see Figures 4 and 5).Footnote 43 The shift towards branding Hazeline Snow as a cosmetic cream in India and China paralleled changes in the marketing strategies of Hazline Snow in Britain during the same period. In 1910s Britain, the Hazeline brand was initially proffered as medicinal products treating cuts and abrasions in promotional literature.Footnote 44 As the advent of toiletry lines increasingly supplemented the income of the chemist, BWC adopted a more active marketing strategy in domestic markets in line with developments in modern advertising.Footnote 45 In 1936, G. Valentine Howey, a marketing consultant, further urged BWC to increase publicity for Hazeline products.Footnote 46 Lamenting that it was a pity that ‘only the discriminating women and those connected with the medical world should know of the high qualities of these preparations – and the advantageous price’, Howey came up with advertising sketches that presented BWC as a high-quality manufacturer offering affordable, scientific beautification products to a wider female public.Footnote 47

Figure 3. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Xinwenbao, 3 Aug. 1933.

Figure 4. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Illustrated Weekly of India, 17 Dec. 1950.

Figure 5. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Illustrated Weekly of India, 20 Oct. 1940.

BWC’s marketing shift underscores the increased imperial obsession with complexion maintenance in the early twentieth century. From the late 1930s, Hazeline was more forcefully advertised to imperial ‘adventurers’ and colonial markets as a skin-lightening commodity attached to racially idealized beauty. The brand’s racialized messaging on health and beauty accentuated the lightening properties of the creams: ‘beautifying the skin, making it soft and white’ and ‘preserves tone and beauty’.Footnote 48 Howey’s advertising sketches of Hazeline similarly proposed to replace medical jargon and medical uses with labelling that emphasized the cultivation of ‘perfect skin’, and recommending it specifically for ‘nourishing and whitening’.Footnote 49 Hazeline Snow was marketed to white women travelling or living in colonized territories like South Africa as a complexion aid for remaining ‘white’ in the ‘blazing sunshine’.Footnote 50 It also became one of earliest cold creams to be sold in India as a skin-whitening product.Footnote 51 Although Hazeline Snow consisted of powdered Borax, Pyrol ‘G’, ‘Lusine’, ‘Hazeline’ Synthetic, water, alcohol, and a perfume named ‘Otto No. 80’, it did not contain explicit bleaching agents such as hydroquinone.Footnote 52 Such skin-whitening products were not new: an array of products had been used in Victorian England to attain a ‘natural English rose’ complexion.Footnote 53

Indeed, much of the imagery around lightening and whitening in cosmetic marketing had developed from the imperial conceptualization of darker skin tones as signs of racial degeneration. These tropes first appeared in advertising narratives for soap that associated cleanliness with progress and optimum ‘racial’ health with beauty.Footnote 54 Pre-war foreign advertising for personal-hygiene products in India appealed to the image of a modern, healthy nation. In India, marketing campaigns evolved from racialized portrayals of civilizing medicines and hygienic soaps to overt messages about ideal beauty and fairness during the 1930s and 1940s.Footnote 55 Lighter skin had not been the sole beauty ideal in pre-colonial India; for instance, white skin could also be associated with illness.Footnote 56 However, in colonial India, preferences for fairness and skin colour stratifications – tied to aesthetics of caste and class mobility – were exploited by foreign multinational companies who expanded their consumer bases in Indian markets based on conclusions drawn from market research about native practices.Footnote 57 Colonial ethnographers had often made assumptions about caste and colour with those from upper castes perceived to be lighter-skinned, and these assumptions were employed in a myriad of ways by foreign companies.Footnote 58 A report undertaken by J. Walter Thompson Company for the Pond’s company in India, Burma, and Ceylon in 1931, for example, claimed that ‘well-off’ Indian women paid ‘attention to their complexions…depend to a large extent upon their colour’ and identified different skin shades amongst various religious, caste, and classed communities, ranging from ‘fair’ and ‘olive’ to ‘tan’ and ‘very dark’.Footnote 59 Companies like Pond’s, LB, and BWC all incorporated acquired knowledge of the Indian body and customs in their localized advertising through the selection of specific languages, sartorial markers, and shaded renderings of women.

From the 1940s, Indian advertisements for Hazeline Snow increasingly targeted women to draw them into narratives of modern fair beauty. After Indian Independence in 1947, Burroughs Wellcome & Co. (India) Ltd was registered under the Indian Companies Act of 1913 with Wellcome Foundation Limited as the principal shareholder, and the Bombay branch of Keymers (of London) was employed for product and press advertising.Footnote 60 The Bombay office pushed for the incorporation of Hazeline Snow’s use ‘as a powder base, and the effect if its whitening the skin’ into new packaging panels because of their ‘particular appeal in this territory’.Footnote 61 However, narratives of fairness continued to be the subject of much discussion between the London and Bombay offices because of the prevailing importance of Hazeline Snow in the Indian market. In 1950, John Curtis and Mr Billeness, who were based in London, deliberated with Mr Donninthorne from the Bombay office about the best illustrations from the ‘racial type angle’.Footnote 62 The main criticism of Keymers was that they ‘Anglicised drawings of Indian girls, emphasising features that the European considers attractive’.Footnote 63 Figure 6 showcased such a racially ambiguous Modern Girl in Indian Hazeline Snow advertising. It appeared in an Urdu-language film magazine in 1957 and the caption promised beauty and elegance (haseen) to its user. Unlike the Modern Girls in Figure 4 and Figure 5 who were draped in dupattas (scarfs), bindis, and modern saris characterized by glamorous simplicity, this Modern Girl was fair but had no visible Indian markers: she was depicted without a dupatta and wearing sunglasses.Footnote 64 This deliberation indicates that there was a real musing over the kind of racialized beauty ideals that would appeal to Indian consumers. Overall, anglicized Indian Modern Girls were not always the most popular icon in advertising: the prevailing trend in Hazeline advertisements across the 1950s was to depict fair or light brown – depending on the colour of printing paper – Indian women.Footnote 65

Figure 6. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Shama, 19 Jan. 1957 – permission from the British Library.

In contrast, the Modern Girls in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements always looked ‘Chinese’, even though they had much in common with fashions elsewhere in the world and echoed the generic Modern Girl aesthetic during the interwar period, which consisted of ‘an elongated, wiry, and svelte body’ that was ‘excessively refined’.Footnote 66 They usually have monolid eyes, which at the time was a stereotypical marker of East Asian descent, and either wore May Fourth-style aoqun (jacket-blouse worn with skirt), as in Figure 7, or qipao (Figure 3); both were distinctively Chinese styles of garment in the early twentieth century.Footnote 67 Clothes with distinctive cultural references functioned not only to reinforce the cultural and national identities of the Modern Girls, but also to locate both the Modern Girls and the advertised product within a modern-yet-familiar framework. BWC clearly adjusted images in its Hazeline Snow advertisements in China and India to appeal to local customs and presented both Chineseness and Indianness as being fully compatible with a modern femininity that was closely tied to the consumption of mass-produced, globally circulating beautification commodities.

Figure 7. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Shenbao, 4 June 1926.

While fair complexion was a hallmark of feminine beauty across Asia, including in Japan,Footnote 68 the association between fairness and racialized notions of beauty in Chinese advertisements was not as intimately underpinned by European colonial endeavours as the discourse of fairness and femininity in colonial India. Western notions of racial categorization were widely circulated in China following its increased contact with foreigners since the late nineteenth century. Even Chinese elementary school students would encounter race theories and particularly a hierarchical view of different races in their textbooks, one that often ranked the ‘black’ race at the bottom and the ‘yellow’ race, which the Chinese belonged to, temporarily below the ‘white’ race.Footnote 69 While the black race was generally characterized as the ‘inferior’ race in such textbooks, in the Chinese context, darker skin tones – or in other words, skin tone variations within the so-called yellow race – were not tightly linked with racial degeneration. As the Modern Girl Around the World Research Group has observed, the discourse of fairness in Chinese cosmetic advertisements did not ‘explicitly reference European or Euro-American Racial whiteness’ and, like in India, imperial ideologies of white racial superiority often intersected with pre-existing skin colour preferences.Footnote 70 Fair skin has long been a class marker in the pre-colonial Chinese aesthetic value system, as it distinguished the upper class from the peasant class who had to labour under the sun and subsequently had tanned skin.Footnote 71 Moreover, although Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements claimed that it could keep the skin ‘fair and soft’ (bainen), Hazeline Snow was not marketed as a skin-whitener in China and fairness was not the sole criterion for healthy and beautiful skin. Chinese interpretation of beautiful skin often valorized skin’s radiance, smoothness, softness, and a rosy complexion.Footnote 72 In Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements, the word bai (white/fair) did not appear as frequently as words such as jiao (tender/delicate), run (well-moisturized), ruan/nen (soft), and yan/mei/li (stunning/enchanting/gorgeous).Footnote 73 Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements also regularly stressed its function to restore and maintain the ‘natural beauty’ of skin.Footnote 74 While a Chinese female consumer praised that after using Hazeline Snow ‘the yellowish colour on my face disappeared’, she also stressed that ‘now the bright rosy light shines, and the skin becomes smooth’.Footnote 75 Nor was this undesirable ‘yellowish colour’ a reference to the yellow/Chinese race – according to this woman, her countenance ‘became yellow and thin’ owing to overwork, which was likely a reference to traditional Chinese medicinal beliefs that connected a yellow complexion with deficiency of spleen qi (vital energy).Footnote 76

As Hazeline Snow emerged as a modern and scientific beauty product globally in the early twentieth century and fairness became a globally accepted beauty standard, it also becomes clear that pre-colonial concepts of beauty became entangled with colonial racial hierarchies in distinctive ways. In India, racialization of caste was central to the discourse of modern fair beauty ideals, and there were visible tensions between foreign corporations’ assumptions of racialized beauty and the fair yet undoubtedly Indian beauty ideal preferred by the local audiences. A racialized beauty standard, on the other hand, did not feature as prominently in contemporary Chinese valorization of fairness. Such differences in the character of colonial modernity matter, as they suggest that local actors played a significant role in the formation of vernacular understandings of beauty. To further explore the dynamics between the global and the local, we proceed to examine a long-neglected aspect of gendered beauty standard – namely, the representation of men in cosmetics advertising.

III

One of the biggest differences between BWC’s Hazeline marketing in India and China was gendered portrayals of consumers. Notably, Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements featured ‘self-possessed’ men. Figure 8, one of the first Hazeline Snow advertisements to feature the individual male consumer, depicted a young man who wore a traditional Chinese gown, holding a jar of Hazeline Snow in one hand and stroking his chin with the other, a gesture that was reminiscent of the Modern Girls in Hazeline Snow advertisements.Footnote 77 Women unsurprisingly remained the most commonly used icon in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements, yet men appeared frequently too: Figure 9 appeared seventeen times in the popular Shanghai newspaper Xinwenbao between November 1931 and August 1932.Footnote 78 While the ‘girl and mirror’ ensemble became a key element of the Modern Girl icon in the interwar period, this imagery of man and mirror demonstrates that the Modern Girl did not have exclusive claim to consumerist modernity.Footnote 79 Like the Modern Girls in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements, these well-groomed young men wore distinctively Chinese clothes to reinforce their Chineseness. The fact that they wore Chinese gowns rather than Western-style suits sets them apart from the contemporary Japanese modan boi (Modern Boy) in commercial and film culture, who was defined by his love of ‘Western fashion, trendy hairstyles, and consumption and leisure practices associated with notions of modernity’.Footnote 80 Yet the young men in Hazeline Snow advertisements were part of the trope of the Chinese Modern Boy (modeng qingnian) between the 1920s and 1930s, who, although often appearing in Western fashion, also wore exquisite Chinese clothing and enjoyed conspicuous consumption.Footnote 81

Figure 8. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Shenbao, 28 Aug. 1926.

Figure 9. ‘Hazeline Snow’, Xinwenbao, 20 June 1931.

The appearance of the Modern Boy in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements was linked to Hazeline’s branding as a product suitable for both sexes. Early Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements usually mentioned in passing that it could be used by men as an after-shave cream.Footnote 82 The language used in these advertisements was decisively gendered: those appealing specifically to men always downplayed the product’s beautification function by avoiding terms such as ‘cosmetic cream’ and, instead, emphasized its supreme quality and incomparable benefits.Footnote 83 Figure 9, for instance, invoked terms with visible masculinist connotations such as ‘upright men’ (gonggong nanzi) and ‘comfortable and clear’ (xuanlang).Footnote 84 It adopted the ‘commercially viable new-style classical Chinese’, and carefully erased words that conventionally denoted feminine beauty, such as jiaren (beautiful women) and jiaoli (delicately beautiful), which often appeared in Hazeline Snow advertisements targeting women.Footnote 85 Nor did advertisements targeting men invoke the discourse of the fair beauty ideal, despite fairness being a mark of handsome men in imperial Chinese culture. As Song Geng has observed, the image of caizi (fragile scholar), ‘with his jasper-like face, white and tender skin, and rosy lips’, remained the ideal male body in popular romanticism since the Six Dynasties (roughly third to sixth centuries).Footnote 86 Chinese Hazeline Snow advertising’s departure from this pre-modern gendered beauty standard thus reinforced a binary view of modern masculinity and femininity: that different sexes used Hazeline Snow for different purposes. For women, while feminine beautification intertwined with the notion of healthy skin, Hazeline Snow advertisements played more explicitly into the importance of feminine beautification by creating a reciprocal causation between feminine beauty and feminine health. Its narrative of male grooming, on the other hand, predominantly stressed physical comfort and health to avoid undermining its user’s masculinity. It encouraged Chinese men to join a global consumerist modernity centred around self-cultivation and self-care, though it was a discourse that was deliberately dissociated with feminine beautification.

If we locate the Chinese case in the global context, it is striking that contemporary Hazeline Snow advertisements in Europe and India seldom used the image of a self-grooming man. This is not to say that the Hazeline brand did not target the male consumer elsewhere outside China. The narrative of the universal benefits of Hazeline Snow to both sexes also appeared in English-language promotional materials.Footnote 87 Figure 10, for example, featured a young man (who adopted the classical hand-on-the-chin, product-in-the-other-hand pose) alongside female consumers of Hazeline Snow. Yet this was an exception, whereas in the Chinese case the Modern Boy image appeared repeatedly in newspaper advertising.Footnote 88 In India, while Hazeline Snow was not directly advertised to urban men, BWC considered marketing it to male consumers as part of a family package as they became cognisant that Hazeline cream had been used by men for shaving.Footnote 89 Within the Indian context, the potency of advertising for men had focused on connections between masculinity, hygiene, and vitality through the consumption of patent medicines, health foods, and branded soap.Footnote 90 The advertising and consumption of such products, including food tonics like Sanatogen and Kalzana, tapped into the enduring colonial stereotype of the weak Indian male in parts of the subcontinent such as the ‘effeminate Bengali’.Footnote 91 This representational stereotype, however, was not leveraged in adverts for ‘Snows’ and beauty related products. Instead, family personal-care packages were conceptualized by numerous marketers, local and foreign, to capitalize on the discerning, reforming Indian family. For instance, Erasmic’s Himalaya Bouquet brand advertised a ‘Snow’ for female use alongside talcum powder for men.Footnote 92 Nonetheless, the Modern Boy in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements still stood out as a rare case that spotlighted the individual male consumer independent from the family as a consumption unit.

Figure 10. ‘Hazeline Snow’ window display (1936) – permission from the Wellcome Library.

While advertisements are not straightforwardly indicative of actual consumption practices, there is evidence suggesting that Hazeline Snow and other ‘Snows’ (xuehuagao) were used by both women and men globally in the early twentieth century. A short essay published in the Chinese newspaper Libao, for instance, depicted the routine use of xuehuagao as an after-shave cream at the barbershop.Footnote 93 Consumers also used Hazeline Snow in ways unexpected by BWC. While BWC advertised it as an after-shave, it noted that male consumers in Egypt had reported that they used it ‘in place of soap-lather for shaving’.Footnote 94 However, BWC refused to further commit themselves to market Hazeline Snow as ‘a shaving cream in all cases’, as the company believed that the use of Hazeline Snow as a shaving cream depended on the individual’s skin and hair conditions and shaving frequency.Footnote 95

BWC was willing to extend certain liberty to its representatives in different parts of the world in terms of the marketing of Hazeline Snow. On the issue of whether to advertise Hazeline Snow as a shaving cream or only as an after-shave for men, BWC concluded that they would ‘leave the matter in representatives’ hands for tactful handling as opportunity occurs’.Footnote 96 These BWC representatives often worked alongside local employees, which was unsurprising – in the early twentieth century, it was common for foreign companies to rely on local intermediaries to advance their business in Asian markets. The British–American Tobacco Company, for example, employed Chinese commercial artists such as Zhou Muqiao to design its calendar poster advertising in China.Footnote 97 For BWC in India, it was standard practice to ‘find a well-educated native student’ to assist with Indian translations and BWC was particularly concerned with the difficulties of translating English medical terms into the vernacular.Footnote 98 It is worth clarifying that London-based agents were closely involved with Indian advertising: although Indian agents were hired, it was not until 1946 that London’s Overseas Division conceded to Bombay the ‘privilege of preparing locally the settings for these advertisements’ – albeit with continued feedback – due to errors made in vernacular-language newspaper advertising.Footnote 99 In BWC’s Shanghai branch, Chinese employees were hired as assistants to the foreign representatives, stenographers, typists, writers, and translators, including a certain Dr Ts’ao who was responsible for translation and advertising.Footnote 100 While their Shanghai staff lists did not include any painters, BWC did hire Chinese artists to design their calendar posters for the Chinese market from the late 1900s.Footnote 101 As BWC was not a client of the major advertising agents in Shanghai (the Carl Crow Inc., the Millington’s Agency, and the China Commercial Advertising Agency that represented other household names such as Pond’s and LB in China), it seems highly likely that the Shanghai branch formulated its own ad copies, even though external artists may have been hired to design the visuals.Footnote 102 The Shanghai branch was given considerable leeway as to how it marketed Hazeline Snow in China, especially in comparison with the tighter control the London office imposed on the Bombay office. No archival evidence indicated that the Shanghai branch received marketing instructions from the London office; quite the contrary, it requested the London office drop the mention of tube packaging in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements.Footnote 103

The Modern Boy in Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements therefore was not simply a reincarnation of the colonial stereotype of effeminate Asian men. Late nineteenth-century Chinese intellectuals were keenly aware of the racialized colonial stereotypes of the effeminate Confucian literati and the ‘Sick Man of Asia’ trope, yet they reappropriated this colonial logic to create a martialized masculinity that worked towards re-masculinizing Chinese men by repudiating the allegedly ‘effeminate’ features of Chinese men and reinforcing ‘hard’ features captured by colonial stereotypes.Footnote 104 While the Hazeline Snow Modern Boy, with his beardless smooth face and traditional Chinese gown, visually resembled the colonial stereotype of effeminate scholar, BWC Shanghai’s ad copies, as discussed above, actively attempted to dissociate Chinese young men using Hazeline Snow from the accusation of effeminacy. Moreover, the Chinese Hazeline Snow Modern Boy had many similarities with the equally beardless and fair skinned European male consumer in Figure 10, who might well be deemed ‘effeminate’ by contemporary European standard.Footnote 105 BWC did not intentionally create an exclusive association between Chinese men and male effeminacy based on racialized colonial gender stereotypes. Rather, we argue that the Hazeline Snow Modern Boy was an alternative Chinese interpretation of beauty, health, femininity, and masculinity that was connected, but not identical, to knowledge systems originated in the ‘West’.

It is also worth noting that the Modern Boy co-existed with a wide range of masculine ideals in early twentieth-century China and never became the prevailing masculine model. His modernness was linked to his consumption of mass-manufactured foreign commodities, which differed significantly from popular masculine ideals that either emphasized martial prowess (wu) and physical strength,Footnote 106 the need to serve the nation through technology and industrial production,Footnote 107 or a reconfigured May-Fourth intellectual/literati (wen) masculinity that combined romantic sensibility with Western knowledge of love, science, and freedom.Footnote 108 Although Chinese Hazeline Snow advertisements tried to present consumption as at once masculine, modern, and Chinese, a considerable amount of Chinese urban audience did not subscribe to this interpretation of modern masculinity. Chinese social commentaries often mocked Modern Boys who used xuehuagao: a military adviser urged youth not to ‘pay too much attention to xuehuagao but to their beards’, with beards being a symbol of manliness; and another piece commented sarcastically that ‘after foreign goods flooded into China, we saw Modern Boys…wearing three layers of xuehuagao, their face as white as walls’.Footnote 109 Just like how the Modern Girl, often perceived as the opposite of the political-minded and moral New Woman, was portrayed as the personification of consumerist and subsequently negative ascriptions of modernity, the Modern Boy who indulged in materialism was seen as being ‘effeminate’, ‘fake modern’, and the antithesis of the authentic modern New Youth.Footnote 110 As the threat from imperial Japan became ever more evident in 1930s China, rising tides of Chinese nationalism rendered this Modern Boy masculine model increasingly undesirable among urban educated Chinese, for he embodied everything that was deemed detrimental to the national rejuvenation project: the blind admiration of Western commodities and subsequent lack of enthusiasm for domestic products, frivolousness, and effeminacy.

Sebastian Conrad has made a compelling argument in a different context that ‘the uneven process of global integration generated debates at the interplay of masculinity, strength, beauty, health and nationalism in many places’.Footnote 111 The Chinese Modern Boy and the various Modern Girl figures in Chinese and Indian Hazeline Snow campaigns showcased perfectly how ‘the uneven process of global integration’ resulted in different expressions of colonial modernity. The discourse of modern fairness in Indian Hazeline Snow campaigns played into both imperial and local anxieties over racial degeneration, whereas Chinese advertisements reflected a deeper concern and ongoing negotiation of the relationship between masculinity and consumerist modernity. BWC’s marketing had to adapt flexibly to local conditions, and the advance of colonial capitalism crystallized in BWC’s overseas expansion did not necessarily result in homogenizing understandings of race, beauty, femininity, and masculinity. Although a further analysis of the reasons for such semiotic divergence is beyond the scope of this article, the cases analysed here effectively illustrate the limit of the diffusionist model premised on the dissemination of Western knowledge to the rest of the world. As we shall see, ‘Snows’ became a product of its own right whose meanings were constantly altered in response to evolving global and local challenges.

IV

Though originating from Hazeline Snow, other ‘Snows’ were taking on new socio-cultural lives of their own amongst manufacturing and consuming interlocutors across Asia.Footnote 112 They transited from being associated with a specific company to becoming a particular kind of skincare commodity and, in South Asia, specifically identifiable as skin-lighteners. After the First World War, German, Swiss, and American companies and local entrepreneurs began to compete with British firms like BWC and LB.Footnote 113 The popularity of BWC’s branded products meant that imitations of names, images, and motifs were rife. Many Indian businesses, for instance, appropriated the use of ‘ine’. Across the 1920s and 1930s, Henry Wellcome attempted to tackle irregular trade laws by assigning powers of attorney to foreign ‘resident representatives’ in various port cities including Bombay, Shanghai, Cape Town, and New York.Footnote 114 These representatives were tasked with investigating and legally contesting fraudulent imitations, such as disputing The Premier Chemical Works (Calcutta) who named their product ‘Hazelene Snow’ and Lia Chemical Works (Shanghai) who used the Hazeline Snow design to advertise a simulated product in English and Chinese.Footnote 115 Between 1917 and 1937, BWC pursued at least fifteen cases of fraud and trademark infringement in Asian markets including in India, China, Japan, and Formosa.Footnote 116 Companies like BWC and LB also lobbied their governments to utilize legal institutions and diplomatic channels to globally police fraud.Footnote 117 The growing demand for vanishing creams and the unrelenting concern for ensuring that consumers were not confused by names nor buying products elsewhere demonstrates the profitable landscape of beauty creams in the transnational personal-care marketplace.Footnote 118 BWC’s concern for sustained trademark and brand recognition thus was a response to the proliferation of imitations since the interwar period as well as the emergence of other ‘Snows’.Footnote 119

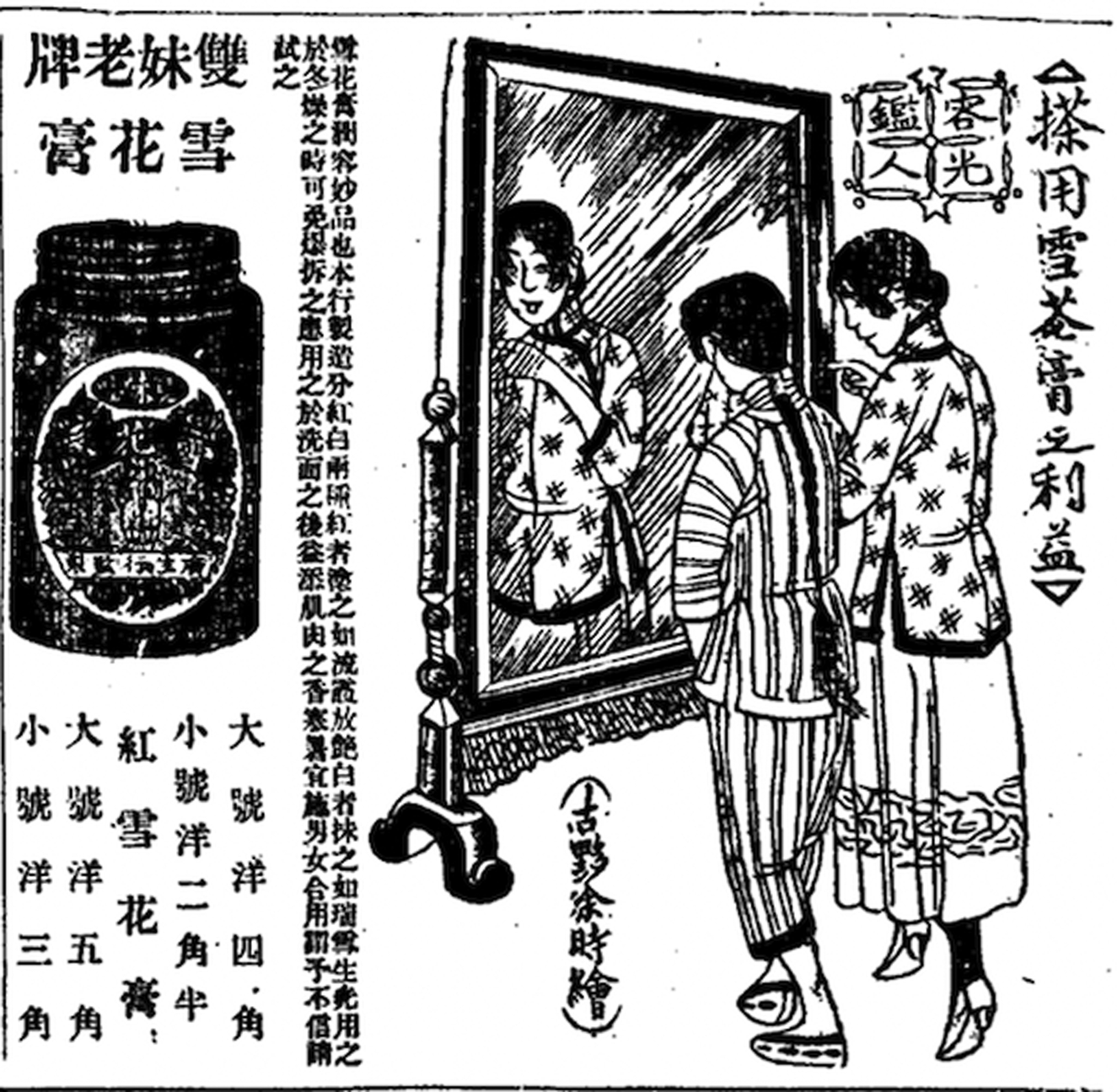

In India, cheaper local ‘Snows’ such as Cosmoline Snow, Raja Snow, and Pearline Snow competed with foreign ‘Snows’ like Oatine Snow and BWC’s Hazeline Snow.Footnote 120 In 1945, BWC raised concerns about the increased advertising for Afghan Snow and Hindustan Snow.Footnote 121 In Republican China too, Hazeline Snow faced competition from cheaper local brands such as Xiangya xuehuagao, Xianshi xuehuagao, and most notably, Two Girls Snow (Shuangmei xuehuagao), which was manufactured by the Hong Kong-based company Kwong Sang Hong and first appeared in the Chinese market in the mid-1910s (see Figure 11).Footnote 122 Japanese ‘Snows’ like Lait Snow and Double Beauty Snow (Shuangmeiren xuehuagao) were also proffered as modern beauty products in the Chinese market, especially in the north-east region where Japan extended its imperial influence.Footnote 123 The similar brand names of Two Girls and Double Beauty did raise questions about whether the former was a knockoff of the latter. However, no conclusive evidence, such as trademark infringement disputes, indicated that this was indeed the case. Japanese imitations of Hazeline Snow such as Artlino Snow, on the other hand, were circulated not only in its domestic market, but also in India and China.Footnote 124 Such inter-Asia exchanges remained a key feature of the early twentieth-century medical-cosmetic India and Chinese markets.

Figure 11. ‘Two Girls Snow’, Shenbao, 14 Jan. 1918.

Local ‘Snows’ became popular amongst colonial consumers because of profound economic concerns and suspicions around imports across various Indian and Chinese consuming publics. Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati, and Urdu domestic manuals and women’s periodicals warned readers about buying bakwas (nonsense) in the bazaar which could cause nuksaan (damage).Footnote 125 In Sultan Jahan’s Hifz-i-Sihhat, Hazeline creams were endorsed alongside homemade concoctions against harmful shop-bought powders.Footnote 126 Although aspiring middle-class Indian households spent on fashionable items as performances of wealth, they also mediated rising prices and nationalist rhetoric around the boycott of foreign goods which endorsed Indian-made products.Footnote 127 In China, localized endeavours similarly harnessed the language of ‘authentic’ versus ‘fake’ or ‘native’ (guohuo) versus ‘enemy’ products (dihuo) to assuage anxieties about false items and foreign goods, which helped Chinese businessmen to gain a foothold in the modern beauty business.Footnote 128 The disruption in production and transportation during the Second World War also helped local competitors to occupy more market shares that previously belonged to BWC. In India, import restrictions on pharmaceuticals meant that Bombay House had to exist on home manufacturing and sales of Hazeline Snow.Footnote 129 While in China, wartime difficulties in obtaining Hazeline Snow gave competing Chinese brands an opportunity to promote their own products. Heiren (‘Darkie’) Toothpaste Company, for instance, stated in a 1943 advertisement for Darkie Cream (heiren shuang), that ‘it is difficult to get “Hazeline Snow” from the market, and Darkie Cream is the only suitable substitute’.Footnote 130 Reinforcing that the quality and smell of Darkie Cream and Hazeline Snow were similar, Darkie advertisements also highlighted that it was much cheaper than Hazeline Snow.Footnote 131 Strikingly, this Chinese rival product of Hazeline Snow would adopt a brand name that literally translated as ‘black man’ and a brand image that contained a smiling Black man while simultaneously emphasizing its skin-whitening function (Figure 12).Footnote 132 The Black figure may well be a subtle take on a ‘before use’ image as he was portrayed alongside a fair woman, but it also suggests a rare unconventional and playful take on the discourse of fairness beauty in China, one that disrupted the conventional advertising formula which typically featured fair beauties to emphasize the benefits of the product.

Figure 12. ‘Darkie Cream’, Shenbao, 10 Oct. 1941.

Unlike many Hazeline Snow-inspired Chinese variations, Indian ‘Snows’ such as Afghan Snow and Erasmic’s Himalaya Bouquet Snow frequently incorporated ethno-regional ideals and racialized histories into advertising narratives from the 1930s. Naming complexion creams ‘Snow’ and the use of mountain and snow imagery proved popular in their associations with lighter and whiter skin. One company, Mehta Bhuta & Co. of Bombay, had to apologize to BWC for simulating the style of Hazeline Snow’s ‘predominant use of snow-clad mountain’.Footnote 133 BWC’s Bombay office was certainly keen to continue to capitalize on the recognizability of the snow-capped mountain to ‘the illiterate Indian’ through the introduction of another packaging panel displaying the mountain motif.Footnote 134 In trans-imperial commodity advertising, mountains were recognizable as racialized entities linked to imaginings of northern climates, racialized genealogies, and beautiful bodies.Footnote 135 Mountain imagery also evoked Indian hill stations frequented by the British colonial community and wealthy Indians as sites of leisure in colonial and post-colonial India, the pervasive pull of which ‘spilled out of the boundaries of India itself’ in popular culture.Footnote 136 Many Indians, both Hindu and Muslim, continue to invoke and envisage mountainous northern regions as inhabited by a beautiful, strong, lighter-skinned ‘race’ marked as such by cooler climates that enabled aesthetic superiority and vitality.Footnote 137 These enduring racialized, caste-based imaginaries were based on the representations of so-called martial races, which referred to peoples who were marked out as physically stronger by British ethnographers including Punjabis, Pathans, Jats, and Sikhs.Footnote 138 Mountain imagery thus invoked regionalized class aspirations in which ‘Snows’ became a recognizable, acquirable commodity associated with nature and the natural, supposed historical genealogies, and gestured to class mobility.

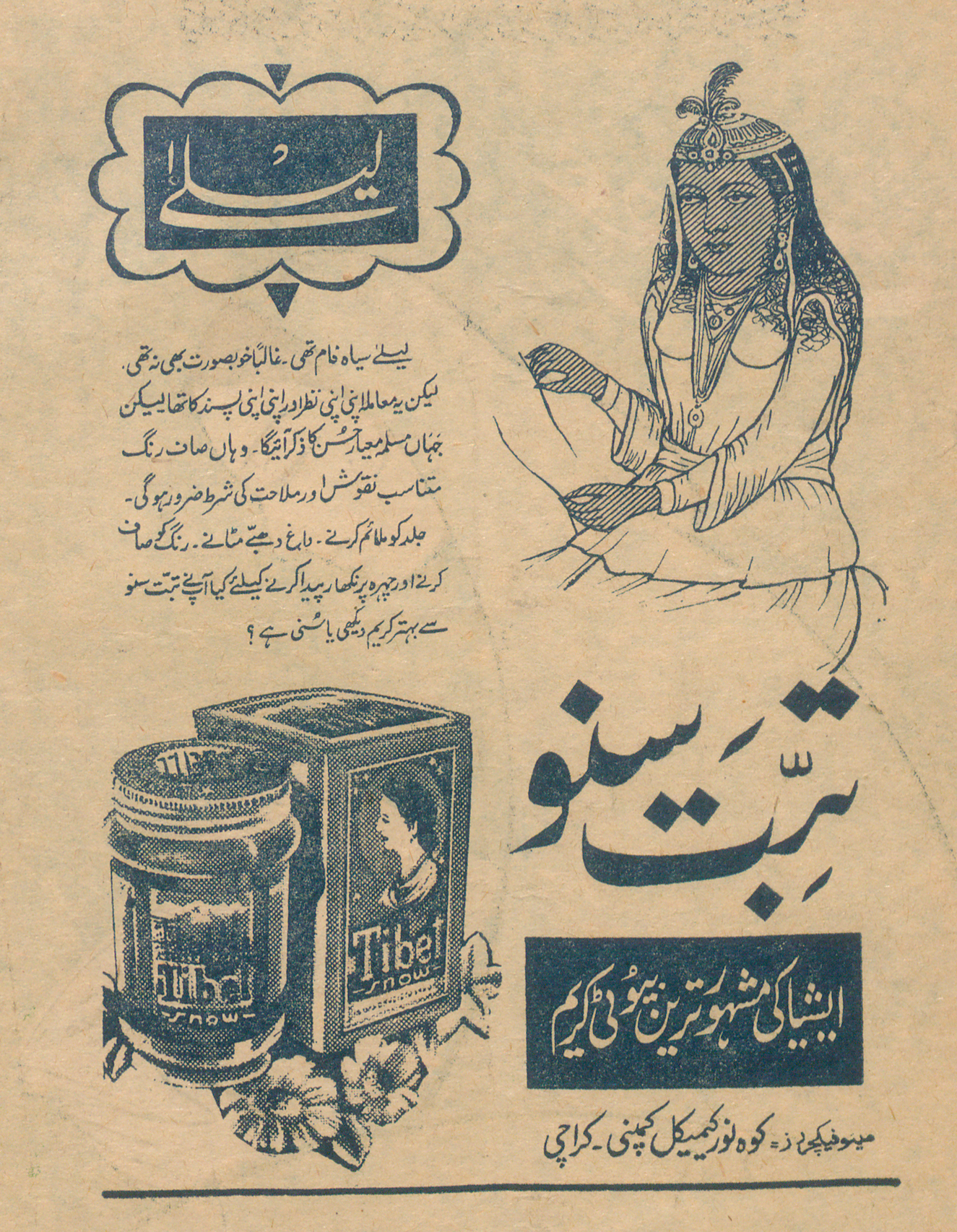

The trope of racialized fairness continued to play a significant role in the localized ‘Snows’. Tibet Snow, a ‘Snow’ that targeted predominantly Muslim women in Urdu-language Ismat, a popular women’s periodical that shifted publication from Delhi to Karachi in newly formed Pakistan, was one such example. Figure 13, a 1955 advertisement of Tibet Snow, depicts a dark-skinned woman who signals a ‘before use’ image in comparison to the fairer-skinned lady on the boxed product packaging. The Karachi-based manufacturers, Kohinoor Chemical Company, drew readers into the affective story of Laila who was ‘approaching the colour of black, probably was not beautiful either’. While the advertisement indicated that beauty was based on individual preference, it also reminded women of a supposed Muslim criterion of beauty, that of saaf rang, denoting clean or cleansed, but also translating as white colour.Footnote 139 Capitalizing on similar lexicons of colour, an enterprising Calcutta-based upper-caste duo, Sharma-Banerjee, tapped into associations of cold and snow with fairness in their advertising for Himani Snow. Amongst a multitude of meanings in Indian languages, Hindi and Bengali translations for himani include snow and cold. Addressing the ‘educated tasteful ladies of Bengal’, one advertisement assured readers that ‘the heat of the sun during the day will not affect [their] face’ if they used Himani Snow.Footnote 140 ‘Tibet’, ‘Afghan’, and ‘Himani’ were strategic naming choices that harnessed the racialization of religion and regionality, whether by reinforcing caste-based assumptions amongst elite Bengali women or the genealogies of elite Muslims across and beyond inter-Asia.

Figure 13. ‘Tibet Snow’, Ismat, Sept. 1955 – permission from the British Library.

BWC, informed by local agents, responded to some of these broader concerns in their advocation of authenticity and quality assurance whilst also trying to protect their brand from the spectre of imitation. Ultimately, though, ‘Snow’ was no longer the preserve of BWC, and the company was a victim of its own success. As a popular, enviable, imitable cold cream on Asian markets, the ‘Snow’ brand became an entity of its own. Branded ‘Snows’, essentially, became a localized, generic Asian beauty product. BWC’s marketing had shifted from an emphasis on medicinal uses to focus on consumer-centred, female preferences for modern complexion aids. However, this transition in India and China came with its own challenges in a competitive global market and competition from local entrepreneurs who were able to harness BWC’s modern racial health messaging alongside relevant cultural touchpoints of caste, religion, gender, and class as well as nationalist sentiments.

V

In the early twentieth century, BWC’s Hazeline Snow, like its foreign multinational competitors, sold a modernity based on female-centred glamour that had a global appeal to its Indian and Chinese consumers. The valorization of ‘science’ behind the product and its role in enhancing appearances remained a common thread in the global marketing of Hazeline Snow. Yet notions of ideal beauty were different in various Asian contexts. Fairness, for instance, while becoming a key feature of ideal beauty in both contexts, attained a more intimate connection to European racialized understandings of whiteness and caste-based assumptions about skin colour in India than in China. Whilst BWC attempted to localize images of a Modern Girl aesthetic based on the cultivation of a feminine, healthy beauty, predominantly depicted by fair skin, the Modern Boy was only depicted to Chinese consumers as a separate consumer base. These nuanced differences in the advertising of Hazeline Snow in China and India gesture towards the varying depictions of Asian modernity on marketing practices within a colonial framework and further reveal the limits of a diffusionist model premised on the expansion of Western modernity. This article has documented not simply national/regional practices and cultural differences as opposing forces to a hegemonic capitalist colonial modernity – Western modernity – but also has demonstrated that BWC’s capitalist expansion was not destined to succeed but had to adapt flexibly to different contexts and compete with local nationalist capitalist forces and other colonial capitalist interests. Within these local contexts, the meaning of being modern was constantly reinvented via this entanglement of global transformations and local conditions.

BWC’s global advertising of Hazeline Snow acutely demonstrates the ways in which pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies attempted to anticipate needs and sell new but familiar products to specific consumer constituencies. In the case of Hazeline Snow, the cosmetic became too familiar. Facing increased transnational competition as ‘Snows’ became a product in their own right, BWC certainly became more perturbed about consumers not being able to ‘distinguish between the genuine and the spurious article [imitation]’ than about ‘Snow preparations…because they do not pretend to be Hazeline Snow’.Footnote 141 Chinese and Indian manufacturers and consumers quickly saw ‘Snows’ as a familiar, modern beauty commodity in the early twentieth-century inter-Asian marketplace. Multiple colonial modernities functioned inter-regionally across Asia, impacting the ways in which local and nationalized goods and advertising images were produced and engendering a specific kind of Asian modernity. Such connections across Asia could be taken further in future scholarship, especially the role of imperial Japan in influencing Indian and Chinese consumer markets.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.