Introduction

Amid the complex landscape of divergent Christian traditions, the Church of England emerged from the turbulent political, theological, and ecclesial post-Reformation years with a highly distinctive DNA. This highly distinctive DNA resulted from a Church that had both embraced the Reformed tradition and yet had not fully forsaken its Catholic roots. It was this highly distinctive DNA that allowed the Church of England in the early nineteenth century to give birth to two highly distinctive movements: the Tractarian movement and the Evangelical movement.

The Tractarian movement was rooted in the Catholic tradition and gave rise to Anglo-Catholicism.Footnote 2 The Evangelical movement was rooted in the Reformed tradition.Footnote 3 The diverging paths of these two movements became consolidated and institutionalized through the development of independent theological colleges,Footnote 4 patronage societies to engineer the appointment of clergy to livings, and divergent trends in church architecture.Footnote 5 The strength and influence of these two movements has shifted within the Church of England throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. Although Evangelicals comprised a minority in the Church of England during the early part of the twentieth century, they consistently gained in strength and influence during the second half of the twentieth century. Saward properly captured the mood in the title of his book preparing for the 1988 Lambeth Conference, Evangelists on the Move.Footnote 6 By way of contrast, the heyday of the Anglo-Catholic Movement occurred in the years after the First World War, but declined during the second half of the twentieth century. Penhale properly captured the mood in the title for his book preparing for the 1988 Lambeth Conference, Catholics in Crisis.Footnote 7

Surface differences between clergy shaped in the Anglo-Catholic tradition and clergy shaped in the Evangelical tradition are still easy to observe in liturgical style and in liturgical dress, but underlying such surface differences are deeper differences in matters of doctrine and belief. Differences in matters of doctrine and belief hinge on different images of God, different understandings of the human condition, different visions of God’s salvific intentions for the human race, and different understandings of how the Church is called to share in God’s salvific activities. It is against such a broad theological and ecclesial landscape that it becomes meaningful to ask whether Evangelical clergy and Anglo-Catholic clergy read the Church of England’s response to the Covid-19 crisis against the same script, or whether in fact there were two distinctive Church of England readings of this response. First, however, the context needs to be set by locating the specific research question within a broader research tradition that has explored the impact of ‘churchmanship’ or ‘church orientation’ on Anglican clergy beliefs and attitudes.

Assessing the Correlates of Church Orientation

The key study that brought the impact of churchmanship or church orientation to become a focus for research within empirical theology is Kelvin Randall’s book, Evangelicals Etcetera: Conflict and Conviction in the Church of England’s Parties.Footnote 8 Drawing on data provided by 340 clergy ordained to stipendiary ministry in the Church of England and the Church in Wales in 1994, Randall makes two important contributions to knowledge concerning churchmanship or church orientation.

Randall’s first contribution to knowledge concerns clarifying the way in which churchmanship may be conceptualized and operationalized within empirical research. Randall built on earlier work by members of Francis’s research group who had proposed assessing churchmanship by means of one or more semantic differential scales as proposed by Osgood, Suci and Tannenbaum.Footnote 9 Examples of these earlier studies are provided by Francis and LankshearFootnote 10 and by Francis, Lankshear and Jones.Footnote 11 Randall invited his participants to identify their churchmanship by selecting a point on three 7-point semantic differential scales. The first scale was anchored by the two terms ‘Catholic’ and ‘Evangelical’. The second scale was anchored by the two terms ‘Liberal’ and ‘Conservative’. The third scale was concerned with assessing the influence of the Charismatic Movement. In this way three dimensions of churchmanship were clearly differentiated. The validity and utility of the Liberal-Conservative and Catholic-Evangelical scales was subsequently confirmed by independent analyses on samples of Church of England clergy and laity.Footnote 12

Randall’s second contribution to knowledge concerned documenting the difference between clergy identifying as Catholics and clergy identifying as Evangelicals across four main areas: personality, well-being, ministry priorities, and belief and practice. In terms of personality, assessed by the short-form Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised,Footnote 13 Evangelical clergy recorded higher extraversion scores and lower neuroticism scores. In terms of well-being, assessed by the Oxford Happiness Inventory,Footnote 14 no significant differences were found between Evangelical clergy and Catholic clergy. In terms of ministry priorities, using a new role inventory, Catholic clergy gave the highest priority to being a minister of sacraments and person of prayer, while Evangelical clergy gave the highest priority to being a preacher and person of prayer. In terms of belief and pastoral practices, marked contrasts emerged between Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy. For example, while 79% of Catholic clergy were happy to conduct baptisms for children from non-church families, the proportion fell to 45% among Evangelical clergy. While 61% of Evangelical clergy agreed that they have helped people become Christians this year, the proportion fell to 34% among Catholic clergy.

The Church Times Survey conducted in 2001 provided an opportunity to compare the attitudes and beliefs of 846 Catholic clergy and 366 Evangelical clergy who responded to the survey across 15 well-defined areas; Francis, Robbins and Astley reported that statistically significant differences were found across all 15 areas.Footnote 15 For example, in terms of creedal beliefs, 54% of Catholic clergy believed that Jesus’ birth was a virgin birth, compared with 93% of Evangelical clergy; and 41% of Catholic clergy believed that hell was a real place, compared with 83% of Evangelical clergy. In terms of sexuality, 82% of Evangelical clergy considered it wrong for men and women to have sex before marriage, compared with 33% of Catholic clergy; 85% of Evangelical clergy considered it wrong for people of the same gender to have sex together, compared with 36% of Catholic clergy; and only 5% of Evangelical clergy were in favour of the ordination of practising homosexuals as priests, compared with 44% of Catholic clergy. In terms of interfaith issues, 85% of Evangelical clergy believed that Christianity is the only true religion, compared with 40% of Catholic clergy; and 32% of Evangelical clergy were in favour of state-funded Islamic schools, compared with 54% of Catholic clergy.

A subsequent and more sophisticated analysis of the data from the 2001 Church Times Survey, reported by Village and Francis in their book The Mind of the Anglican Clergy,Footnote 16 confirmed the importance of churchmanship in shaping clergy beliefs, attitudes and practice, even after taking into account the effect of personal factors (age and sex) and psychological factors (extraversion, neuroticism and psychoticism). Continuing to draw on data from the 2001 Church Times Survey, three further studies illuminated more fully the effects of churchmanship among clergy and laity on homonegativity,Footnote 17 theological, moral and ecclesiastical issues,Footnote 18 and civic volunteerism.Footnote 19 Data from the 2013 Church Times Survey confirmed that churchmanship remained of considerable significance.Footnote 20

Research Question

Covid-19 took the world by surprise and took the world by storm. Decisive action was needed and decisive action was effected. In England the government imposed a lockdown on the nation on 23 March 2020. The following day the Church of England imposed a lock-up on all its churches. Churches were closed completely, even for private prayer, and even for the clergy. The problematic and potentially controversial nature of the Church of England’s response to the pandemic has been well documented and assessed by McGowan, drawing on materials now readily available in the public domain.Footnote 21 In his analysis of the Church of England’s response to the pandemic, McGowan suggested that:

The problems were immediate and obvious, except perhaps to the Archbishops and their immediate staff. Many worshippers, not just clergy, wanted to be connected with the spaces and places that meant so much to them. Members of the Church were now being offered alternative forms of prayer and worship, via technologies not always familiar or welcome, centred on clergy whose faces which had become personal avatars of worship. Without the context of stone and wood that spoke of a larger reality than personality or family, and reminded them of a past and future beyond the challenging present, this personalised corporate worship as never before. (p. 3)

McGowan’s analysis may reflect a view more prevalent within the Anglo-Catholic strand of Anglicanism than within the Evangelical strand of Anglicanism. If this were to be the case, the actions of the archbishops may have been more acceptable to Evangelical clergy than to Anglo-Catholic clergy and may have reinforced the mood of the 1980s that referred to Evangelicals on the move and to Catholics in crisis. The Coronavirus, Church & You Survey provides an opportunity to test this thesis.

We designed the Coronavirus, Church & You Survey throughout April 2020, in consultation with bishops, clergy and laypeople, and in dialogue with the Church Times, building on the successful collaboration experienced in the 2001 Church Times Survey and the 2013 Church Times Survey. This survey was designed to explore a number of themes, including: assessing institutional responses to the crisis; assessing responses of the local and national Church during the crisis; assessing the policy to lock up churches; assessing the role of churches in ministry and mission; assessing learning from the lock up for the future of churches; anticipating the longer-term impact for the parish system; embracing the digital future; valuing virtual communication; and thoughts about going back to an offline future.

The objective of the present paper, therefore, is to explore the extent to which clergy who identify with the Anglo-Catholic stream and clergy who identify with the Evangelical stream of the Church of England evaluate these issues in the same or in different ways. In other words, are Anglo-Catholic clergy reading the experience of Covid-19 against the same text as their Evangelical colleagues, or are they reading things differently? In formulating this research objective, we are aware of the rich diversity within both the Anglo-Catholic stream and the Evangelical stream of the Anglican Church. The precise research question, however, has been focused on exploring the overall differences between the two streams rather than on the diversity within each stream.

Method

Procedure

During April 2020 an online survey was developed using the Qualtrics platform. A link to the survey was distributed through the Church Times from 8 May 2020. The link was also distributed through a number of participating Church of England dioceses. The survey was closed 23 July 2020, by which time there were over 7000 responses. Although this survey attracted responses from laity, from outside England and from non-Anglican participants, the focus within the current analysis is on Church of England clergy within England.

Measure

The current analysis draws on three sections of the survey designed to assess attitudinal responses of the clergy toward nine sets of Likert-type items assessed on a three-point scale: disagree (1), not certain (2), and agree (3). The nine sets of items explored the following themes: assessing institutional responses to the crisis; assessing responses of the local and the national Church during the crisis; assessing the policy to lock up churches; assessing the role of churches in ministry and mission; assessing learning from the lock-up for the future of churches; anticipating the longer-term impact for the parish system; embracing the digital future; valuing virtual communication; and going back to an offline future.

Analysis

The present analyses were conducted on data provided by two specific groups of participants among the 748 Church of England full-time stipendiary parochial clergy who responded to the survey: 263 who self-identified as Anglo-Catholic and 140 who self-identified as Evangelical. For the purposes of this analysis attention is not given to the 345 clergy who occupied the Broad Church position between the two wings of the Church of England. The statistical significance of differences in the scores for Likert items reported by the two groups of clergy was tested using chi-squared analysis on 2 × 2 contingency tables, for which the three-point Likert scale responses were collapsed into two categories differentiating between agreeing and not agreeing.

Results and Discussion

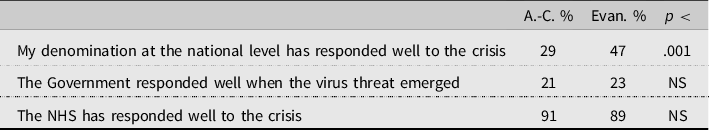

The first set of three items presented in Table 1 was designed to compare the way in which clergy evaluated the responses of three major institutions to the pandemic: the Government, the Church and the National Health Service. Here the data showed that Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy read the responses of the government and the National Health Service in the same light. Thus, 21% of Anglo-Catholic clergy and 23% of Evangelical clergy regarded the government as having responded well when the virus threat emerged; and 91% of Anglo-Catholic clergy and 89% of Evangelical clergy regarded the National Health Service as having responded well to the crisis. Where the difference emerged, however, was in the way in which these two groups of clergy read the response of the Church. While 47% of Evangelical clergy regarded the Church as having responded well to the crisis, the proportion fell to 29% among the Anglo-Catholic clergy. Here is the first indication that Anglo-Catholic clergy have felt more badly affected by the Church of England’s response to the pandemic.

Table 1. Assessing institutional responses to the crisis

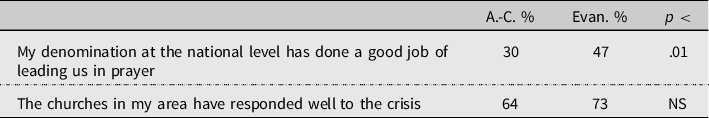

The second set of two items presented in Table 2 was designed to compare the way in which clergy evaluated the responses of the national Church and of the local churches during the crisis. Both groups of clergy rated the responses of local churches more highly than the responses of the national Church. At the same time, Evangelical clergy rated the responses of the national Church more highly than Anglo-Catholic clergy. Thus, while 30% of Anglo-Catholic clergy considered the national Church had done a good job of leading us in prayer, the proportion rose to 47% among Evangelical clergy. However, although 64% of Anglo-Catholic clergy considered that churches in their area had responded well to the crisis, and the proportion rose to 73% among Evangelical clergy, this difference was not statistically significant. Here is the second indication that Anglo-Catholic clergy have rated less highly the Church of England’s response to the pandemic.

Table 2. Assessing responses of the local and the national Church during the crisis

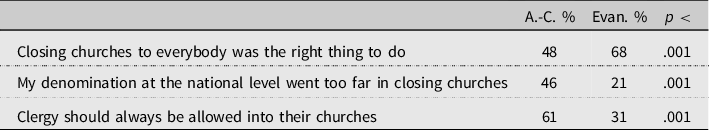

The third set of three items presented in Table 3 was designed to explore how clergy responded to the Church’s policy to lock up churches during the great national lockdown. Here the divide between Evangelical clergy and Anglo-Catholic clergy became very clear. While two-thirds of Evangelical clergy (68%) considered closing churches to everybody was the right thing to do, the proportion fell to just under half of Anglo-Catholic clergy (48%). While 21% of Evangelical clergy considered that the Church went too far in closing churches, the proportion rose to 46% among Anglo-Catholic clergy. While 31% of Evangelical clergy considered that clergy should always be allowed into their churches, the proportion rose to 61% among Anglo-Catholic clergy. Here is the third indication that Anglo-Catholic clergy have rated less highly the Church of England’s response to the pandemic.

Table 3. Assessing the policy to lock up churches

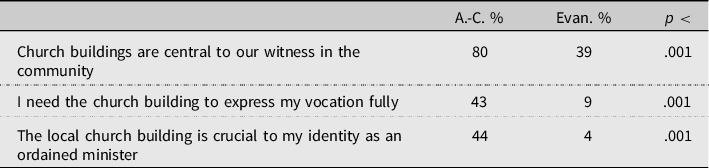

The fourth set of three items presented in Table 4 was designed to assess how clergy perceived the role of churches within the context of ministry and mission. Once again there was a clear divide between the views of Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy, with a much higher importance being attributed to churches by Anglo-Catholic clergy. While four-fifths of Anglo-Catholic clergy (80%) maintained that church buildings were central to their ministry in the community, the proportion fell to two-fifths of Evangelical clergy (39%). While 43% of Anglo-Catholic clergy maintained that they needed the church building to express their vocation fully, the proportion fell to 9% of Evangelical clergy. While 44% of Anglo-Catholic clergy maintained that the local church building was crucial to their identity as an ordained minister, the proportion fell to 4% of Evangelical clergy. Here are expressed some of the reasons for Anglo-Catholic clergy feeling more badly affected by the Church of England’s response to the pandemic.

Table 4. Assessing the role of churches in ministry and mission

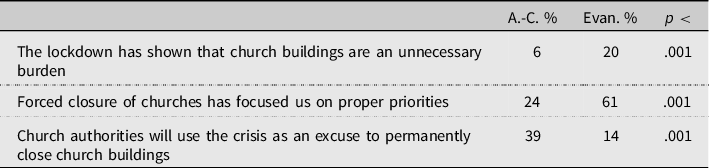

The fifth set of three items presented in Table 5 was designed to assess how clergy evaluated what could be learned from the lock-up for the future of churches. For Evangelical clergy the forced closure of churches had been read as a helpful experience: 61% of Evangelical clergy agreed that the forced closure of churches had focused them on proper priorities, but the proportion fell to 24% of Anglo-Catholic clergy. For 20% of Evangelical clergy the lockdown had shown that church buildings were an unnecessary burden, but the proportion fell to 6% among Anglo-Catholic clergy. At the same time, Anglo-Catholic clergy were more cynical than Evangelical clergy about how the current leadership within the Church would read the implications of the lockdown experience for church closures. Thus, 30% of Anglo-Catholic clergy endorsed the view that church authorities would use the crisis as an excuse to permanently close church buildings, compared with 14% of Evangelical clergy. Here is evidence that Anglo-Catholic clergy felt more under pressure from the Church of England’s response to the pandemic.

Table 5. Assessing learning from the lock-up for the future of churches

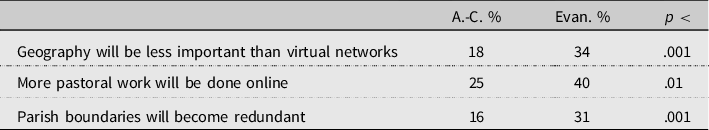

The sixth set of three items presented in Table 6 was designed to assess how clergy evaluated the longer-term impact of Covid-19 for the sustainability of the parochial structure of the Church of England. Here the data showed that Anglo-Catholic clergy remained more reluctant than Evangelical clergy to see the demise of the parochial system. While a third of Evangelical clergy (34%) suggested that, as a consequence of the pandemic, geography would be less important than virtual networks, the proportion fell to 18% among Anglo-Catholic clergy. While two-fifths of Evangelical clergy (40%) suggested that more pastoral work would be done online as a consequence of the pandemic, the proportion fell to 25% of Anglo-Catholic clergy. While nearly a third of Evangelical clergy (31%) suggested that parish boundaries would become redundant as a consequence of the pandemic, the proportion fell to 16% of Anglo-Catholic clergy. Here is evidence that Anglo-Catholic clergy remained committed to a style of parish ministry that the Church of England’s response to the pandemic may have rendered less sustainable.

Table 6. Anticipating the longer-term impact for the parish system

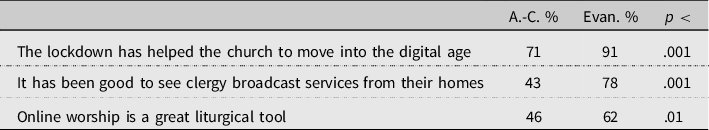

The seventh set of three items presented in Table 7 was designed to assess the attitude of clergy toward the sudden trajectory into the digital future. Once again the levels of enthusiasm for this transition were quite different between Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy. While 91% of Evangelical clergy read the lockdown as having helped the Church move into the digital age, the proportion dropped to 71% among Anglo-Catholic clergy. While nearly four out of every five Evangelical clergy (78%) agreed that it had been good to see clergy broadcast services from their home, the proportion dropped to just over two out of every five Anglo-Catholic clergy (43%). While 62% of Evangelical clergy valued online worship as a great liturgical tool, the proportion dropped to 46% among Anglo-Catholic clergy. Here is evidence that Anglo-Catholic clergy found the trajectory to online worship, enforced by the pandemic, less acceptable.

Table 7. Embracing the digital future

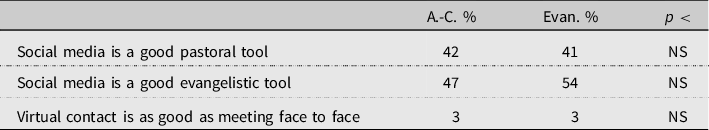

The eighth set of three items presented in Table 8 was designed to focus attention on virtual communication. Not only did the lockdown open up the challenge for online worship, but it also opened up the need to explore more intentional approaches to virtual forms of communication and pastoral care. Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy were much closer in their appreciation of virtual communication than they had been in their appreciation of online worship. Thus, two-fifths of Evangelical clergy (41%) rated social media as a good pastoral tool, and so did 42% of Anglo-Catholic clergy. Over half of Evangelical clergy (54%) rated social media as a good evangelistic tool, and so did nearly half of Anglo-Catholic clergy (47%). Only a very small minority of both groups of clergy read virtual contact being as good as meeting face-to-face: 3% of Evangelical clergy and 3% of Anglo-Catholic clergy. Here is evidence that, although Anglo-Catholic clergy were less inclined to endorse online worship, they were no less inclined to endorse forms of virtual communication.

Table 8. Valuing virtual communication

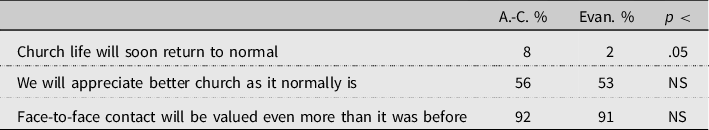

The ninth set of three items presented in Table 9 was designed to explore whether clergy anticipated a return to an offline future. Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy held similar views about a return to an offline future. The majority of both groups anticipated that, when there was a return to normal, face-to-face contact would be valued even more than it was before: 92% of Anglo-Catholic clergy and 91% of Evangelical clergy. Slightly over half of both groups anticipated that, when there is a return to normal, we would appreciate better church as it normally is: 56% of Anglo-Catholic clergy and 53% of Evangelical clergy. Slightly more Anglo-Catholic clergy (8%) than Evangelical clergy (2%) anticipated that church life would soon return to normal, but clearly this view was not shared by the majority of clergy in both groups. Here is evidence that Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy were equally keen to return to on offline future.

Table 9. Going back to an offline future?

Conclusion

In his editorial contribution to the Journal of Anglican Studies, McGowanFootnote 22 was critical of the Church of England’s response to the pandemic, arguing that the problems to this approach ‘were immediate and obvious, except perhaps to the Archbishops and their immediate staff’ (p. 3). The present paper has hypothesized that McGowan’s critique would find greater resonance with an Anglo-Catholic evaluation of the situation than an Evangelical evaluation. This hypothesis was then tested against data collected by the Coronavirus, Church & You Survey that enabled the responses of 263 Anglo-Catholic full-time stipendiary parochial clergy to be set alongside the responses of 140 Evangelical full-time stipendiary parochial clergy. The responses of these two groups of clergy were considered in relation to nine groups of items designed to capture the following themes: assessing institutional responses to the crisis; assessing responses of the local and the national Church during the crisis; assessing the policy to lock up churches; assessing the role of churches in ministry and mission; assessing learning from the lock-up for the future of churches; anticipating the longer-term impact for the parish system; embracing the digital future; valuing virtual communication; and thoughts about going back to an offline future. Four main conclusions emerge from these data.

The first conclusion is that Anglo-Catholic clergy felt less comfortable than Evangelical clergy with the Church of England’s leadership during the Covid-19 crisis. For example, 29% of Anglo-Catholic clergy considered that the Church of England at the national level had responded well to the crisis, compared with 47% of Evangelical clergy; and 30% of Anglo-Catholic clergy considered that the Church of England at the national level had done a good job of leading us in prayer, compared with 47% of Evangelical clergy.

The second conclusion is that Anglo-Catholic clergy felt considerably more disenfranchised than Evangelical clergy by the policy to lock-up churches. While 68% of Evangelical clergy agreed that closing churches to everybody was the right thing to do, the proportion fell to 48% among Anglo-Catholic clergy. While 31% of Evangelical clergy argued that clergy should always be allowed into their churches, the proportion rose to 61% of Anglo-Catholic clergy. Anglo-Catholic clergy were also more suspicious about the longer-term intentions of the Church. Thus, 39% of Anglo-Catholic clergy felt that church authorities would use the crisis as an excuse to permanently close church buildings, compared with 14% of Evangelical clergy. The issue at stake is that Anglo-Catholic clergy see the sacred space of the local church as central both to their own identity as priests and to Christian witness in the community. Thus, 44% of Anglo-Catholic clergy maintained that the local church building is crucial to their identity as an ordained minister, compared with 4% of Evangelical clergy; 80% of Anglo-Catholic clergy maintained that church buildings are central to our witness in the community, compared with 39% of Evangelical clergy.

The third conclusion is that Anglo-Catholic clergy were more attracted than Evangelical clergy not only to the sacred space of the parish church, but also to the local place of the parish system. Thus, Evangelical clergy were twice as likely as Anglo-Catholic clergy to envisage that the longer-term impact of Covid-19 would mean that parish boundaries would become redundant (31% compared with 16%). Evangelical clergy were also twice as likely as Anglo-Catholic clergy to envisage that the longer-term impact of Covid-19 would mean that geography would be less important than virtual networks (34% compared with 18%).

The fourth conclusion is not that Anglo-Catholic clergy are more reluctant than Evangelical clergy to enter the digital age, but that they do not conceptualize online worship as an adequate substitute for meeting in the local place (the parish) and for celebrating in the sacred space (the parish church). Thus, Anglo-Catholic clergy are just as likely as Evangelical clergy to rate social media as a good pastoral tool (42% and 41% respectively), and Anglo-Catholic clergy are almost as likely as Evangelical clergy to rate social media as a good evangelistic tool (47% and 54% respectively), but Anglo-Catholic clergy are considerably less likely than Evangelical clergy to rate online worship as a great liturgical tool (46% and 62% respectively).

Underlying these four key differences in the ways in which Anglo-Catholic clergy were reading the Church of England’s response to the Covid-19 crisis differently from Evangelical clergy are core principles that shape the Anglo-Catholic view of the nature of God, the Anglo-Catholic view of the human condition, the Anglo-Catholic vision of God’s salvific intentions for the human race, and the Anglo-Catholic grasp of how the Church is called to share in God’s salvific activities. In spite of the fundamental internal dispute that separates the path of the two groups styled Forward in Faith and Anglican Catholic Future (concerning the ordained ministry of women), in her introduction to the recent collection of essays, God’s Church in the World: The Gift of Catholic Mission, Lucas argues that faithful Catholic Anglicans are united in their devotion to Catholic piety and practice, and to the parish as the Anglican way of being God’s Church in the world. In her introduction, Lucas spells out this vision in the following way:

The Catholic tradition of the Church of England is missional ab initio, formed by a conviction that the presence of Christ in the Eucharist intensifies and motivates an awareness of the sacramental presence of Christ in the world – God’s Church in God’s world exists for the sake of the Missio Dei, the sending of the loving God into his creation in the Son, and its continuation, through the Holy Spirit, in the life of the Church.Footnote 23

No wonder, then, that Anglo-Catholic clergy felt more disenfranchised by the Church of England’s national response to the Covid-19 crisis, that, from their perspective, may have seemed to undervalue the significance of local place (the parish) and of sacred space (the parish church). It is these specific matters that may have seemed less troublesome to Evangelical clergy, and less immediately obvious to the archbishops and their immediate staff.

Although the present study was established specifically to contrast the ways in which Anglo-Catholic clergy and Evangelical clergy read the Church of England’s response to the Covid-19 crisis, there are within these data core pointers regarding the influence of these two streams of church tradition within the contemporary Church of England. The observation that the national church leadership so clearly assumes an Evangelical way of managing church life and of shaping a future for the Church, places the Anglo-Catholic wing under greater pressure and marginalizes the Anglo-Catholic voice. The title of Penhale’s (1986) book, Catholics in Crisis, may have been descriptive of the way in which he saw things in the 1980s, and at the same time prophetic for the development of the Church of England into the third decade of the twenty-first century.