Adapazarı lived through this movement much earlier, in the morning of Turkey’s liberation, when the population of the country was just about to wake up to the magical impact of the revolution, to throw off its servitude and to stand up against yesterday’s bullies…. And this oppression and servitude not only existed in the people’s political life, but also in their economic life. My friend, you should also know that the women workers in the workshops of Adapazarı revolted against their bosses in a newly developing conscious movement. Footnote 1

Introduction

The above commentary quote was written during a series of strikes by women working in the silk industry in the region around Bursa, in what today is known as Turkey, summer into fall 1910.Footnote 2 The quote is remarkable for two reasons: it refers to women protesting against their employers in Adapazarı, a town situated to the northeast of the Sea of Marmara, and the source is a regional Armenian periodical. Although several scholars have written articles about the strikes in Bursa, none have hitherto referred to the female labor activists in Adapazarı. This is probably because information about the activists is lacking both in the Ottoman archives and in the Ottoman Turkish newspapers published in Istanbul, the main sources for most of the authors. However, since many of the silk factory owners and their workers in the Adapazarı region were Armenian, Armenian revolutionary organizations were actively involved in local labor activism there and wrote extensively about the bad working conditions and efforts to improve them in their own publications.

Using sources written in the languages of the main actors in the Ottoman labor movement is essential. The Ottoman Empire was a multi-ethno-religious state with many communities speaking several languages. Writing a comprehensive history of Ottoman society is impossible without grasping the complicated, intertwined histories of its many ethno-religious communities. For any historian, it is difficult to reach the voices of the nondominant; ignoring sources in their languages means that their voices remain largely unheard, which is also a problem in the study of Ottoman social and labor history.Footnote 3

Writing Ottoman labor history

Early studies on Ottoman labor history were written by Turkish academics who were actively involved in leftist movements, so for the most part they only briefly referred to it as an introduction to their accounts of Turkish, republican labor history.Footnote 4 In the 1980s and 1990s, historians like Zafer Toprak, Donald Quataert, and Erik Jan Zürcher became interested in the social history of the late Ottoman Empire.Footnote 5 The increasing availability of documents from the nineteenth and early twentieth century in the Ottoman Archives and the rich newspaper and periodical collections of the period allowed them to pursue the topic. These pioneers in turn inspired younger scholars, who explored three subfields within social history which are of particular relevance for this article: labor history, women’s history, and the history of the ethno-religious communities in the late Ottoman Empire.

From the 2000s onward, the three subfields were intertwined in studies by a new generation of scholars, such as Yavuz Selim Karakışla, Gülhan Balsoy, and Malek Hassan Abisaab, who published on women and/or gender of the working classes, and by Stefo Benlisoy who wrote on ethno-religious diversity within the context of labor history. Erdem Kabadayı, Kadir Yıldırım, and Can Nacar paid close attention to ethno-religious communities and women in their studies on workers in the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 6 So did Nicole van Os and Birten Çelik, who wrote about the Bursa strikes. Both also pointed to the involvement of Armenian revolutionary parties in these strikes.Footnote 7 While past scholars largely based their work on (Ottoman) Turkish and some foreign sources, Yaşar Tolga Cora and Hasmik Khalapyan included Armenian texts, while Stefo Benlisoy used Greek sources.Footnote 8

This article focuses on Armenian women working in the silk industry in Adapazarı between 1908 and 1912. We describe how the female workers established a union, how they bargained and struck for better working conditions, and how they became economic and political actors forcing other actors, most notably Armenian socialist organizations and factory owners, to take them into account. We explore how their multiple identities, as workers, as women, and as members of a particular ethno-religious community living and working in the Ottoman Empire, shaped their struggles. Thus, we aim to contribute to existing literature combining labor history with women’s history and the history of ethno-religious communities. The article adds to our knowledge of the labor movement and the strike wave which occurred after the Young Turk Revolution of 1908. It also provides background knowledge on a strike in Adapazarı in 1912 unreferred to by past scholars publishing on the post-1908 strike wave.Footnote 9

Sources

We utilize unused primary sources including Armenian language newspapers and houshamadyans. The language barrier, as well as anxiety about work on the social conditions of Armenians in the late Ottoman Empire due to the heated debates around the Turkish government’s denial of the 1915 Armenian genocide, has prevented scholars of Ottoman history from studying these sources. Armenian regional newspapers as well as those published in the imperial capital provide us with ample information on the Armenian communities which played an important role in local economic and social activities. Specifically relevant are the socialist or left-leaning papers of the Armenian political parties of the era. Their (local) correspondents minutely described the working conditions for laborers in sweatshops and factories in various towns and villages, as well as the activities of the local workers’ associations. The articles also displayed the power struggles among the different political groups active in the region. The “labor question” as they sometimes called it, became even more crucial in the context of the post-1908 era. The change of regime led to a widespread belief that everything, including the conditions of workers, could and would change as the introductory quote indicates.

Houshamadyans or memory books provide another source. These are mainly works of collective memory written by the survivors of displaced Armenian communities in the diaspora seeking to reconstruct the social, cultural, and political lives of the homelands they left behind.Footnote 10 The content and form varies depending on the sources used by the author or editor and their aim, ranging from descriptive narratives to statistics and lists. Houshamadyans cover a wide range of topics such as the activities of the political parties in their community, the working conditions in local factories or labor activism. Those compiled about the villages and towns around the Sea of Marmara, therefore, provide valuable information on several aspects of sericulture, a pivotal economic activity for many Armenian communities in that region. The houshamadyan by Minas Kasabian, a journalist and member of an Armenian revolutionary group, who investigated Armenian communities in the region extensively between 1910 and 1912, is of particular relevance.Footnote 11 In addition to these sources, we also explore French newspapers and commercial yearbooks, Annuaires Orientals du Commerce, from the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 12 They represent the view of those with vested interests in the local industry, such as foreign intermediaries and investors, and provide further context.

Armenian socialist activism and the labor question: The Hnchagyan and The Hay Heghapokhgkan Tashnagtsutiwn

The socialist labor movement in the Ottoman Empire started in Thessaloniki around the turn of the twentieth century. The majority of those organizing workers and spreading socialism were Christians and Jews.Footnote 13 The groups involved in socialist activism in the late Ottoman Empire also included two Armenian revolutionary groups: the Hnchagyan and the Hay Heghapokhagan Tashnagtsutiwn (usually referred to as Tashnaks).

The Hnchagyan (Bell) Revolutionary Party, which was founded in 1887 in Geneva by a group of Armenian students from the Caucasian provinces of the Russian Empire, was one of several revolutionary groups active in the Ottoman Empire in the period leading up to the 1908 revolution. Their goal was to improve the living conditions of their Armenian brethren in the Ottoman Empire by establishing a politically independent Turkish Armenia in the eastern regions of modern day Turkey, which would eventually also include Russian and Persian Armenia. In addition, they sought to create a socialist society under a democratic government, not only in a new, independent Armenian republic, but universally. For this, they deemed that participation by peasants and workers in the party’s revolutionary activities was essential. The Armenians in the broader region, therefore, had to be led on the “road to socialism” through propaganda, agitation, and terror. Instrumental for this, they felt, was, a network of branches of the Party in, particularly, the Central and Eastern provinces of Anatolia.Footnote 14 Another, contemporaneous revolutionary group was the Hay Heghapokhagan Tashnaktsutiwn (Armenian Revolutionary Federation [ARF]). The ARF was a federation of activist Armenian groups which joined forces in 1890, initially including the Hnchagyan. The ARF, however, sought democratic reforms for Armenians within the Ottoman polity. As a result, the Hnchagyan split off in 1891. In 1896, moreover, a dispute occurred within the Hnchagyan; those who favored abandoning socialism as a leading principle separated to form the Veragazmyal Hnchagyan (Reformed Bell). Despite efforts to overcome their differences, the two continued to exist as separate organizations until the 1910s.Footnote 15 In the meantime, the ARF joined the Second International, becoming one of the Ottoman socialist voices abroad.

Following the 1908 revolution, both the Hnchagyan and the ARF became legal, the former was renamed the Ottoman Social-Democrat Hnchagyan Party (SDHP), whereas the ARF continued under the same name. Both parties were critical of the poor working conditions for factory workers and artisans and improving their situation formed part of their goals and party programs. The ARF wanted reduced working hours, the introduction of lunch-breaks, regular payment of wages, the abolishment of night shifts for women and teens, and a ban on child labor, as well as insurance for workers, free health services, superintendents elected by the workers, and co-participation in the administration of factories.Footnote 16 Meanwhile, during its assembly in Istanbul in 1910, the SDHP decided to carry out research into the conditions of the workers, form special units to write bylaws for workers’ unions taking into account local conditions, put workers’ issues on the agendas of the responsible bodies of the party and try to get them on the agenda of the Ottoman parliament. Furthermore, they wanted to establish party-guided workers’ unions everywhere with the party administering their publications and agents, and to establish a special unit within the party which would be responsible for the “labor question.”Footnote 17

The newspapers Azadamard (Battle for Liberation) and Abaka (Future), were the mouthpieces of the ARF and SDHP respectively, and local periodicals such as the weeklies Yergir (Country), published in Adapazarı by the SDHP and Biwtania (Bithynia), published in Izmit and associated with the ARF, regularly featured articles on the poor working conditions demanding improvement, while they also reported on the post-1908 strikes.

While the SDHP, Veragazmyal Hnchagyan, and ARF were primarily focused on increasing their influence in Cilicia and central and eastern Anatolia, areas relatively densely inhabited by Armenians, they did not ignore other regions with large Armenian populations.Footnote 18 One of these regions was located around the Sea of Marmara, where, over centuries, a large number of Armenians had settled in “a continuous string of villages that stretched from the Black Sea coast through Adabazar and Ismit to Bursa,” and where a significant labor force had formed due to the development of the silk industry.Footnote 19

Armenians in Adapazarı

The town of Adapazarı

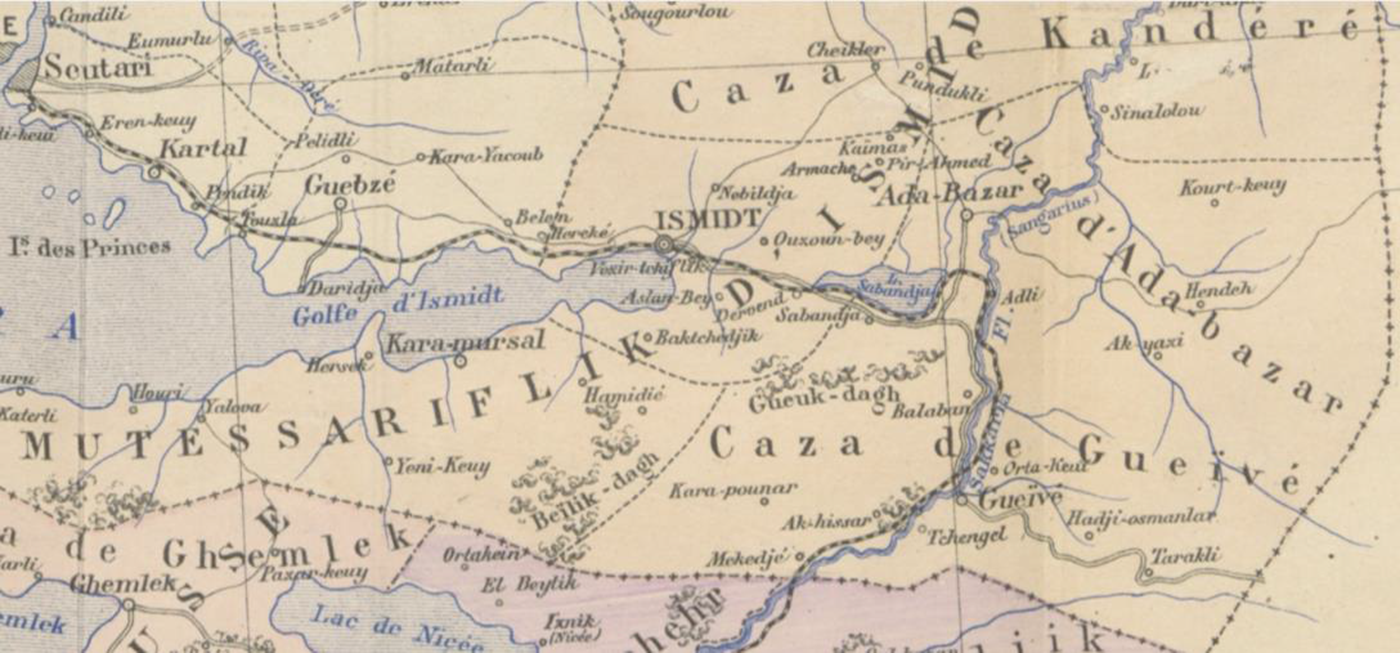

Adapazarı was a town and the administrative center of a district with the same name within the region of Izmit situated northeast of the Sea of Marmara (Figure 1). The district was known for its production of timber, potatoes, tobacco, and silk. The extension of the railroad network into the region enhanced its economic relevance. Such major infrastructure projects took place through the mediation of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration (OPDA), an institution which had to ensure that the Ottoman Empire would pay off the debts it had accumulated in the nineteenth century with its European and local creditors.Footnote 20 To this end, the OPDA collected the taxes on tobacco and silk, amongst other items.Footnote 21 From 1886 onward, the OPDA was actively involved in the expansion of sericulture in the region. The increasing economic relevance of the region in general and Adapazarı in particular was also demonstrated by the opening of a branch of the Ottoman Bank in the town in 1907 and by its growing population.Footnote 22

Figure 1. Part of a map of the Province of Hüdavendigar (from Vital Cuinet, La Turquie d’Asie: géographie administrative, statistique, descriptive et raisonée de chaque province de l’Asie-Mineure, 4 vols, Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1890–95, vol. 4, 1894, iv). Adapazarı (Ada-Bazar) is located to the east of Ismidt (İzmit).

Population

In Ottoman cities and towns, some neighborhoods comprised of a mixed population; others were predominantly inhabited by one community and situated around a mosque, synagogue, or church. In Adapazarı, Apostolic Armenians were concentrated in parishes situated around their four churches, while Protestant Armenians had their own church.Footnote 23

Population figures for specific years at local level are unreliable. According to the Annuaires Orientals for 1891, 1909, and 1912, the population of Adapazarı hardly grew during the period. Among the some 25,000 inhabitants, about 9,000 were Turkish/Muslim and about 10,000 were Armenian.Footnote 24 Vital Cuinet, the general secretary of the OPDA, and Minas Kasabian, correspondent and houshamadyan author seem to have relied on the same information in their publications in 1894 and 1913, respectively, as they offer similar figures. Cuinet, however, refers to a population of 12,300 Muslims, adding the more than 3,300 “émigr’és” or “refugées” mentioned in the Annuaires to the local Muslim count.Footnote 25 In the Annuaire Oriental of 1914, the figures were updated: the population had grown to 35,000, with 13,500 “Turks” and 14,500 Armenians.Footnote 26 Sarkis Karayan, who tried to establish the number of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire on the eve of the 1915 genocide, estimated that Adapazarı had about 20,000 Armenian inhabitants but pointed out that the sources were not very straight forward.Footnote 27

Historian Kemal Karpat quotes considerably higher numbers in his study. The reason is probably that the Annuaires provided figures for the town itself, while the census data he used were for the entire district, including surrounding villages, which were predominantly inhabited by Muslims. The figures also show considerable population growth between 1881/1882 and 1914, to a total of 102,000 in 1914 from 54,000 in the 1881/1882–1894 census. During this period, however, the proportion of Armenians decreased to 16 percent from 26 percent due to the influx of Muslim refugees from the Caucasus and, later, the Balkans.Footnote 28

Many Armenians in the area were involved in the production and trade of silk. The majority of the filatures in Adapazarı were owned and run by Armenians who themselves employed mainly Armenians.

Filateurs and filatures

It is unclear when the first filature was established in Adapazarı. One of the first references in the Ottoman archives dates to the early 1860s when a certain Artin, Harutyun in Armenian, received permission to establish a filature.Footnote 29 Other archival documents deal with a dispute around a filature owned by a woman, Lutsika, and managed by a man named Hampar[t]sum in 1868.Footnote 30 When the Minister of Agriculture, Nuri Efendi, came to Adapazarı in 1886, he visited a filature owned by a “Hadji Foti.”Footnote 31 This probably was the only filature owner in Adapazarı referred to in the Annuaire Oriental of 1891, Photi Panayotidi, an Ottoman Greek and one of the two filatures with, according to Cuinet, a total of 130 workers in Adapazarı in the early 1890s.Footnote 32

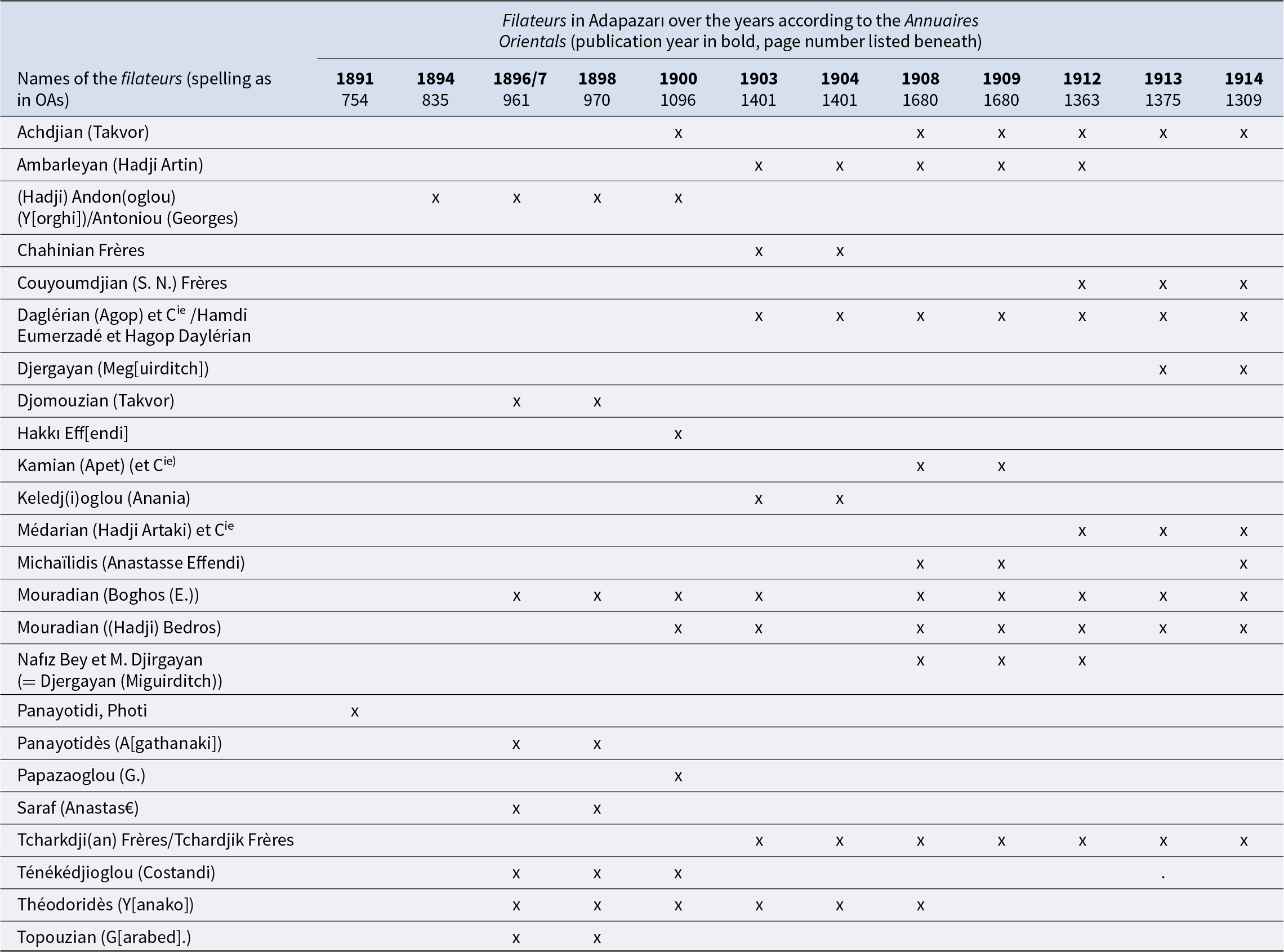

The figures in the Annuaires Orientals over the period 1891–1914, as listed in Table 1, do not always match those in other sources. The reason may be that the Annuaires Orientals listed the names of the filateurs, rather than of filatures. Filateurs were the entrepreneurs engaged in reeling silk; they could just be owners or also actually operating the facility. Moreover, as we can see from the sources, sometimes workplaces may have been listed which were laying idle. So, while there were ten to eleven filatures according to the Ottoman Turkish Malumat (Knowledge) by 1900, the French Moniteur des soies mentioned fourteen filatures and the Annuaire Oriental of that year listed only eight.Footnote 33 The francophone newspaper Stamboul refers to the owner of a filature, M. Saprichyan, who was acquitted after being accused of insurance fraud for setting fire to his filature in 1905.Footnote 34 However, Saprichyan does not appear on any list of names in the other sources. Régis Delbeuf, who visited the region in 1906, counted ten filatures (Table 2).Footnote 35 The Annuaires Orientals of 1908 and 1909 mention eleven and nine filatures, respectively.Footnote 36 Revue commerciale du Levant, the monthly bulletin of the French Chamber of Commerce in Istanbul, provides different numbers: eleven filatures in 1908, of which eight were powered by steam and three by men, and fourteen (with a total of 659 basins) in the production season of 1909/1910.Footnote 37 According to Kasabian, who reported on the years 1910–1912, there were ten active spinneries; five had closed down.Footnote 38 The Annuaires Orientals of 1912, 1913, and 1914 list nine, eight, and then again nine filateurs, respectively, while according to Stamboul, only half of a total of twelve existing filatures were in production in August 1913.Footnote 39

Table 1. Filateurs in Adapazarı according to the Annuaires Orientals of 1891–1914

Table 2. Filature owners and operators, trademarks, and number of basins and workers in Adapazarı according to Delbeuf and Kasabian

The names of the owners of filatures in the town over the years, as listed in various sources, can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

Workers in the filatures

Kasabian is the only source with a detailed list of workers in the filatures based on gender and ethno-religious background (see Table 2). Laborers in the Adapazarı filatures were predominantly female and Armenian, though some filatures (also) employed Greek women. The males employed were predominantly Armenian, too. The reasons to employ women in particular for reeling silk have been listed by van Os—the work required nimble fingers and dexterity, women could be paid lower wages, and they were expected to be more docile.Footnote 40 X. Dybowski, writing for the periodical of the French Chamber of Commerce in Istanbul, described three categories of female laborers working in the filatures in Adapazarı:

Small girls of 11 to 14 years were responsible for finding the end of the filaments of the cocoons and for preparing the work for the actual silk reelers. One of them each suffices for two basins, that is for two reelers. They earn between 1 and 1.5 piasters per day. The reelers [earn] between 2.50 and 5 or even 6, but this is exceptional. It is unnecessary to say that the laborers who get 5 piasters form a minority. The third category consists of women responsible for making the hanks [= a reel of 1000 meters]Footnote 41, the packaging, for weighing of the raw silk produced by every reeler every day, and for determining the quality. The reelers who distinguish themselves with more refined and important work can, but this is again exceptional, receive a bonus of 10, 20 or 30 paras per day. The laborers of the third category generally get 5 piasters. They are limited in numbers.Footnote 42

The author found the salaries relatively low for the 16 hours the women worked per day under such bad circumstancesFootnote 43 and told how

[t]hey are very tired and cannot wake up in the morning, or rather night in the winters, so a man is charged to go and wake them up, to bring them in groups to the filature, and to bring them home in the evening, or rather night again.Footnote 44

He concluded that the situation was not tenable. Female laborers in Bilecik had gone on strike before, he wrote, forcing the factories to close and ultimately resulting in an increase in pay for the workers.Footnote 45

Organizing the workers, organizing women

It is unknown whether the Hnchagyan, Veragazmyal Hnchagyan, or ARF were involved in this early strike in Bilecik, but they had been active in the East Marmara region, including Adapazarı, from the late nineteenth century onward.Footnote 46 Moreover, Kasabian refers to the existence of a number of active women’s organizations in Adapazarı. Their members were, in general, engaged with education and relief work, and belonged to the local elite.Footnote 47 However, one of them was different: the Adapazarı Medaksi Kordzaworagan Miutiwn (Adapazarı Silk Workers’ Union [AMKM]).

The AMKM and interparty struggle in Adapazarı

The union was founded in September 1908 only two months after the revolution.Footnote 48 Kasabian, who refers to the organization as the AMKM listed its goals as follows:

To protect and spread its members’ economic and class interests and to assist in its’ [sic!] educational development. The means to be used:

a. To gain the greatest increase in daily wages for its members and to determine the lowest daily wage

b. To regularize the hours worked and working conditions

c. To improve its’ [sic!] members economic and health states

d. To provide assistace [sic!] to those members who are out of work or poor or to find work for them

e. To promote a spirit of solidarity and reinforce it among the women workers, without regard to race or religion

f. To create means to educate the intellectual capacity of the women workers (libraries, lectures etc.)

g. To prevent the employment of girls under 14 years old in factories

h. To announce a strike, if necessary, at the same time as assisting the women workers to successfully achieve results in their economic strugglesFootnote 49

Nerses Papazyan, an active ARF member and political activist who was killed in 1915, claimed in one of his long articles in Azadamard that the women established the AMKM encouraged by ARF leaders. Despite this, and despite the fact that the union used the ARF newspaper as one of its means of communication, the AMKM claimed to be nonpolitical and “free to accept help from the existing socialist revolutionary parties [in plural, italics are ours].”Footnote 50 As for its membership fee, which was set at a very reasonable one kurush monthly, 40 percent was used for strike action, a similar portion to promote the union’s interests by setting up profit-making enterprises, and the remaining 20 percent for daily expenses.Footnote 51

A few weeks after the AMKM was established, workers in two factories in Adapazarı went on strike demanding higher pay. Although an article about the strike in Servet-i Fünun does not refer to the AMKM, it seems likely that they were involved in this action. By that time, women workers in different factories in Adapazarı had already been organized.Footnote 52

On September 20, 1909, two female union officials, Aghavni D. Antrosyan (chair) and Yevkine Gdradzyan (secretary), invited members to a general assembly to celebrate the union’s first anniversary and to present its accounts.Footnote 53 The tone of the invitation was rather defensive; it included a response to “certain people who have been trying to dismantle our union from the day of its foundation through baseless claims” that the AMKM misused its funds. Some members wanted to resign from the union demanding a refund of their membership fees. This was bluntly refused.Footnote 54

Although the AMKM was clearly connected to the ARF, the political group did not directly control the union. This gave the union room to organize in the direction members wanted, but also occasionally led to criticism from the party. While Papazyan described the AMKM as a model union for organizing women workers in his articles in Azadamard, he also highlighted its shortcomings and provided a blueprint for future success. He claimed that workers had been positively influenced by continuous calls from the revolutionary parties after the 1908 revolution, which resulted in about 900 Armenian girls and women working in various workplaces forming several associations which united under one board.Footnote 55 Addressing his “worker-sisters” in the AMKM, Papazyan underlined, however, that the workers made some mistakes due to their inexperience. They had acted overhastily in trying to achieve their goals like “all formerly disenfranchised naturally act (…) when they open their eyes and see the horizon of rights for the first time.”Footnote 56

He also accused several unnamed actors of actively opposing the formation of the union to serve their own interests, while benefiting from the inexperience and lack of class consciousness among the female workers. Failing to make the union cease its work, they attempted to sabotage its expansion, he stated.Footnote 57 He was likely referring to the factory owners and to the Hnchagyans in the region who challenged the union as shown below.

The reason for emphasizing the inexperience and subsequent problems of the AMKM in the ARF newspaper was probably because the party wanted to take the lead in directing workers’ unions to a more conscious, organized and extensive struggle. Papazyan emphasized that the prosperity of the wealthy was the result of the labor of those who worked, indeed it was theft. To fight this injustice, they had to emulate the prosperous; if they organized to pass laws, the workers should organize as well. According to Papazyan, the first step was the creation of a class in itself: that is, the creation of conscious workers through education who would understand the socialist struggle. Furthermore, workers should teach each other to unionize, stand up to the factory owners and support each other. Moreover, they should work to solve any problems among laborers and between themselves and factory owners as quickly as possible. He added that organizations such as the AMKM needed sufficient financial means to survive, so paying membership fees was important. And, finally, the organization and its activities should be formalized, i.e. established according to the new Law on Associations (Cemiyetler Kanunu) which was issued in August 1909, in order to gain more power in the future.

The workers’ associations should include workers of different ethno-religious communities. Getting organized this way would create, according to Papazyan, a strong base for future demands, including the first, minimum demand, that of an eight-hour work day. Solidarity and co-operation among workers in larger umbrella unions would lead to “the real victory of revolution, carrying the banner of the reality of socialism … instead of minimum demands.”Footnote 58

In another article, Papazyan provided detailed information regarding the history of the AMKM. He differentiated between the some 20 organizers of the union and around 900 workers who organized in different associations throughout Adapazarı at one time. Papazyan argued that the members of the AMKM were easily influenced by anti-union propaganda, which specifically targeted its ties with the ARF. He claimed that the great aghasFootnote 59 were particularly anti-union. They had hired some men to convince women workers to withdraw their support from the AMKM. They told the women that their money was used by the ARF rather than the AMKM and that the authorities had already passed rules to regulate daily working hours and salaries, which was not the case.

Most women indeed withdrew their support, thus undermining the early successes of the union, such as an agreement with factory owners regarding shorter working hours and higher pay. The workers opposing the union tore down the new rules, which had been posted on the walls of the filatures to inform the workers. When the AMKM called for the general assembly mentioned above, only a few members, all anti-union, showed up. Thus, the relatively strong position of the union was jeopardized and it lost its leverage vis-à-vis the workshop owners. By the time Papazyan’s history of the AMKM was serialized in the newspaper, union membership had bounced back, though. There were 250 members and the union treasury held 40 liras. Papazyan hoped that union leadership, together with approximately twenty active members, would continue the struggle and succeed in expanding the AMKM.Footnote 60

As mentioned, the expectations for the new constitutional regime were high. Papazyan stated that he hoped that the new parliament would pass laws related to the organization of the workplace. Only through solidarity and organizing “would [workers] reach the rights of a free person and an Ottoman citizen.”Footnote 61 He also warned workers against getting involved in interparty struggles to the detriment of their interests. While Papazyan regarded anti-union struggles to be a lack of class consciousness, we may interpret them differently: as women workers’ agency in organizing their own union, consciously balancing rival political organizations thus creating support for their own, gendered cause instead of that of the party.

The competition between rival political parties was central to the fate of the AMKM and probably many other workers’ unions and associations during the period. The struggles between the ARF and the SDHP, partly due to the former’s close ties with the Committee of Union and Progress, also affected local power balances. The parties were critical of each other’s involvement in the workers’ movement and unions and tried to sabotage each other’s activities. The antipathy was felt in the workshop and visible in party publications. Factory owners skillfully exploited the interparty rivalries. Kasabian wrote about how one of the local aghas confessed to inviting the Veragazmyal Hnchagyan to set up a group to compete with the other parties. Thus, they succeeded in undermining worker solidarity, weakening the power of the female silk workers and the revolutionary parties.Footnote 62

In July 1910, less than two weeks before the large strike in Bursa started, Yergir, the SDHP weekly, published a letter describing the wretched working conditions in the filatures and, more interestingly, called for the establishment of associations in each filature and a general union as an umbrella organization “by people who know what they are doing.”Footnote 63 While the proposal reminds us of the one made by Papazyan nine months earlier, it includes an overt sneer at the still active AMKM.

In its subsequent issue, Yergir published a small item about a group of AMKM members who had allegedly contacted the publication to voice their concern about possible misconduct by one of their leaders and inquire about the whereabouts of fees paid.Footnote 64 This was a hardly veiled attack on the ARF as it was affiliated with the AMKM. Printed on the same page was a piece on women workers in Kurtbelen in the neighboring district of Nicomedia (Izmit) who had gone on strike and gained certain rights. It accused a member of the local ARF branch of infiltrating the ringleaders of the strike, “sneaky like a snake,” and of taking bribes from the factory owner. The two articles thus show how the two Armenian revolutionary parties tried to use the women workers as pawns in their rivalry.Footnote 65

AMKM leaders responded immediately to the claims in a letter to the competing publication, Biwtania, though. Workers and former members of the union could ask for an audit of the union’s finances if they wanted, not Yergir, they wrote. Furthermore, they criticized Yergir for not supporting the union in the past when it was under attack by different groups and had lost some of its former power. It was only from the ARF that the union had received and would continue to receive support, they added.Footnote 66

After the strikes in Bursa began in the summer of 1910, Biwtania published a letter from Adapazarı by a certain Norayr. The author claimed to be well-informed about the conditions of workers in the district and added that the labor struggle in Adapazarı had begun as early as briefly after the Young Turk Revolution of 1908. What was taking place in Bursa, he wrote, actually reminded him of the earlier struggles in Adapazarı.Footnote 67

In his letter, Norayr attacked the SDHP vigorously. He accused it of collaborating with capitalist factory owners and weakening the AMKM. According to Norayr, the SDHP had declined a call for cooperation from the union to launch its own workers’ association instead, an act not in the interest of the silk workers, but rather of the party. Allegedly, an SDHP member tried to dismantle the AMKM and replace it with a pro-SDHP union.Footnote 68 The accusations reflect the ongoing interparty contest during this period of labor activism in which the SDHP had taken the lead in the mass-strikes in Bursa.Footnote 69 By reminding the readers of the ARF’s role in earlier struggles in Adapazarı, and by attacking the SDHP, the author hoped to generate support for the ARF at a time it was seemingly losing ground to the SDHP.

Following these recriminations in Yergir and Biwtania, the ARF’s Azadamard informed its readers that the AMKM was not dismantled and still had more than seventy members. It was, moreover, writing its bylaws and would share them with workers soon.Footnote 70 Subsequently, the sources are silent about the AMKM and labor activism in Adapazarı for about a year. In the summer of 1911, however, the AMKM was revitalized under the name Adapazarı Medaksi Panworuhineru Arhesdagtsagan Miutiwn (Artisans’ Union of Women Silk Workers (AMPAM)). The new union, usually referred to as the Women Workers’ Union, was closely affiliated with the ARF. Why the union had to be reformed remains unclear. Was it due to the interparty struggles of a year earlier, to the allegations of fraud and mismanagement, or was it a hostile takeover by the ARF to gain more control over the union and to reduce the agency of the women involved? Or was it because the union referred to in the newspapers as AMKM was originally just a union for workers in the silkworm houses as Kasabian implied? And was the new name introduced to do justice to its actual, broader membership?

The AMPAM continued to represent the women workers and voice their demands. Following the union’s general assembly in mid-May 1911, members listed existing challenges and shared their solutions with the public. A major problem was the lack of transparency. The AMPAM wanted the filature owners to pay the workers every two weeks instead of at the end of the season and to pay set daily wages, which would be announced in the first month of the year instead of wages based on production. Furthermore, they wanted the working day to start only after sunrise and to be limited to ten hours, including two and a half hours of break time. All the demands matched those of the ARF.Footnote 71

In 1912, the owners of the Matatyan-ArapzadeFootnote 72 silk spinning factory declined to pay ninety-six workers their full salaries claiming that the workers had not met their production quotas. This happened at Easter, an important religious holiday for Orthodox Christians, when extra money was spent on new clothes and food. It was the perfect opportunity for newspapers to draw attention to the issue with emotional stories. The company owners stated that they would pay 50 liras rather than the 97.5 liras they owed the workers due to the low production levels. The AMPAM, which by that time had about ninety members according to Kasabian, called this an illegitimate cut and in contradiction to the workers’ registers from mid-January. The incident shows that although the factory owners had agreed a year earlier to meet the demands of the union—determining the salaries in January, the creation of registers and, above all, fixed daily wages instead of production quotas—they did not always comply. The AMPAM entered into negotiations with Hacı Artaki Matatyan, who dismissed the union representatives by stating that they would be responsible for the outcome of their actions. When the AMPAM took the issue to the local governor, Matatyan’s “Turkish partner,” Sait Arapzade, made a bold statement about the potential consequences of a strike. He threatened that it would only increase the number of Armenian beggars most of whom would end up in brothels. By staying silent Madayan endorsed his partner’s words, the correspondent for Azadamard felt.Footnote 73

A month later Azadamard reported two different narratives on the outcome of the conflict. According to the first one, the women workers, “some of whom were members of the union,” went on strike the month before and had taken the case to court. Subsequently, Matatyan had submitted a large part of his debt to an ARF representative together with a written pledge that he would pay the remaining sum upon the end of the strike. According to the Azadamard correspondent, the lesson to be learned from this incident was that “women workers should know that their victory was a result of their unionization and that they should strive to fortify it.”Footnote 74

Two days later, on May 16, 1912, Azadamard published a letter by Ovsanna Bursaleyan and Baydzar Yazeceyan, the (female) secretary and chair of the Women Workers’ Union, respectively, dated April 24, 1912. The Azadamard editors indicated that they decided to publish the letter in reaction to an article in an unidentified Istanbul newspaper in which the factory owner, Matatyan, defended himself. He tried to justify the wage-cuts by claiming that he, as owner, had agreed to pay the workers based on their production rather than fixed daily wages. According to Bursaleyan and Yazeceyan, this was a blatant lie since, as they claimed, set daily wages had been the only type of work contract throughout the city. The union leaders added that following an invitation from Matatyan, a representative committee “in the name of the Board of the Women Workers’ Association (not in the name of the ARF)” had negotiated with the workshop owners.Footnote 75

The first piece in Azadamard highlighted that the factory owner had made the payment to the ARF representative, whereas the letter emphasized the agency of the union in the negotiations. This raises the question why the letter was published, seemingly, more than three weeks after it was written. It may be that the letter was dated according to the Gregorian calendar. In this case, the date was not actually April 24, but May 7, 1912. This would, however, still have left sufficient time for it to reach the desks of the Azadamard editors well before the publication of the first piece on May 14. In addition, it is unclear to whom the letter was addressed. Was it sent to the offices of Azadamard or to local union members for information or, for example, to the local ARF committee? In the latter case, it is possible that it reached the Azadamard offices indirectly and with some delay. A third reason may be that the letter arrived well before the publication of the first article, but that the editors initially declined to publish it, only to change their minds afterward. Although we will never know for sure, this change of heart might well have occurred after some pressure by AMPAM leaders who may have wanted to claim their share in the success. If we put the victory of the women workers and the role of their union aside for a moment, publication of the news about a partial payment by Matatyan before the publication of the letter by the union leaders relegated their voice to a post-factum summary of the events, as if it was not an important moment in a long-lasting labor struggle. The women workers’ agency which was initially denied, was thus yet acknowledged with the publication of their letter, even if this was only two days later.

Conclusion

With this article, we aim to contribute to the labor history of the multi-ethno-religious Ottoman Empire by focusing on Armenian women workers and revolutionaries in the East Marmara region. We show not only how Armenian women working in the silk industry were actually more organized than previously described, but also how they interacted with the Armenian revolutionary parties trying to organize the towns and villages of the region, all the while competing for influence. In doing this, their attitude toward the labor issue was often both idealistic, based on relevant articles in their party programs and at the same time pragmatic; they bolstered their position within the Armenian community, sometimes at the expense of the groups and peoples with whom they should have been collaborating with.

Focusing on the activities of women working in the silk industry in particular in Adapazarı, we show that the series of strikes in the summer of 1910 in Bursa and its environment were not a singular, isolated event, but rather part of broader female labor activism in the region which started at least as early as 1908. Historians of the late Ottoman labor movement have paid plenty of attention to female workers who actively fought for better working conditions and higher pay through striking. The case discussed in this article shows, however, that the Armenian silk workers in Adapazarı were not just individuals striking for their rights, they were firmly organized and, therefore, at times able to negotiate without having to walk out of the workplace.

We discuss the intricate relationship between the union and the Armenian socialist parties active in the region in their struggle for better work conditions and how the union, despite presenting itself as independent, eventually could not escape being entangled in the ARF’s sphere of influence. As such it became subject to interparty struggles. The Matatyan-Arapzade case showed, however, that the women were not simply tools in the hands of patriarchal bureaucrats and activists, as the ARF tried to present them in their newspaper Azadamard, but well-organized and publicly visible actors pushing their own gendered agenda. Thus, for the activism of Armenian silk workers in Adapazarı, both in the form of strike activism and in the formation of labor associations and unions, one’s gender and ethnicity were relevant factors alongside being a laborer.

The article could not have been written without the use of Armenian sources. As Çelik and van Os pointed out, the involvement of Armenian socialists in the worker’s movement in the large strikes in Bursa in 1910 was evident. Neither of them, however, used Armenian sources, although Çelik referred to the translation of an article from Azadamard published in an Ottoman Turkish, socialist periodical.Footnote 76 Through the Armenian sources used for this article, it becomes evident that this was certainly also the case in Adapazarı: Armenian socialist parties were a major factor in the local labor movement. The letters written by the female union leaders and sent to Azadamard and Biwtania, as limited in content as they are, as well as the articles written by local male socialist correspondents, provide us with a unique insight into not only the struggle between unionized women and revolutionary men, but also the interparty strive. While they thus inform us on this hitherto unexamined case of labor activism in Adapazarı, further research in the archives of the ARF and the Hnchagyan might provide us with more details on the intricacies of these struggles. One caveat: using predominantly Armenian language sources entails similar risks as singularly using Ottoman sources—namely the potential loss of perspective on the wider spectrum of interethnic collaboration and competition among workers.Footnote 77

Still, the picture of Ottoman social and labor history will increasingly become more complete by using these sources and writing these partial histories.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Armenian Communities Department of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation for this research. We would also like to thank Erik Jan Zürcher and Dzovinar Derderian and the anonymous peer reviewers for their comments.