Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, a global pandemic. Two days later, the White House declared a nationwide emergency in the United States. Older adults were especially susceptible to COVID-19. While those aged 65 and over make up approximately 17% of the U.S. population, by late 2022, they accounted for 75% of COVID-related deaths.Reference Freed1 Actions taken to mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 protected older adults from COVID-19 but also led to profound social isolation, financial instability, and difficulties meeting basic needs and obtaining medical treatment.Reference Miller2

Among American adults 65 and over, an estimated 10% have dementia or disabling cognitive impairments.Reference Manly3 People living with dementia (PLWD) typically require high levels of care, much of which is provided by family caregivers. The pandemic stressed systems of caregiving for PLWD, and a growing body of literature shows this negatively impacted the wellbeing of PLWD and caregivers alike. Utilization and availability of support services for PLWD decreased.Reference Giebel4 Neuropsychiatric changesReference Canevelli5 and behavioral and psychological symptomsReference Cagnin6 increased for PLWD, and their physical health declined.7 Meanwhile, caregivers for PLWD experienced anxiety, depression, and stress,Reference Altieri and Santangelo8 as well as greater physical and psychological burdens.Reference Hwang9

Although researchers have examined the experiences of PLWD and their caregivers during the pandemic, these studies tend to focus on caregivers in either a community or a long-term care (LTC) setting, limiting the ability to compare dyads’ experiences across these distinct settings. Further, much — though not all — of this work was conducted internationally. Given that there were important differences between countries in public health responses to the pandemicReference Bollyky10 and in the health and social systems available to PLWD and their caregivers generally,Reference Bleijlevens11 there is an opportunity for more focused investigation of country-specific experiences.

Here, we report results from the COVID Caregiving Project, an interview study of American caregivers for PLWD. This research leverages qualitative methods to understand how caregiving relationships were disrupted by the pandemic and to examine how specific features of these relationships mediated this disruption.

To address these gaps, we report results from the COVID Caregiving Project, an interview study of American caregivers for PLWD. This research leverages qualitative methods to understand how caregiving relationships were disrupted by the pandemic and to examine how specific features of these relationships mediated this disruption. Based on these findings, we posit changes to policy and caregiving support interventions that focus on the wellbeing of both members of the caregiving dyad.

Methods

This interview study was reviewed by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt (Protocol # 843130). Interviewees gave verbal consent and received $20 on a ClinCard (i.e., a pre-paid gift card) as compensation. We assigned pseudonyms to afford participants anonymity and to provide continuity across quotations.

Scholars should assess how their own experiences and positions might contribute to their interpretations of individuals’ lived experiences. With this in mind, the research team was composed of members with diverse disciplinary backgrounds, including medical ethics, health policy, anthropology, philosophy, psychology, and gerontology; it included both research staff and faculty researchers.

Sampling and Recruitment

We used a purposive sampling approach to recruit interviewees. Recruitment emails were sent to 123 individuals from the Penn Memory Center Integrated Neurodegenerative Disease Database, a registry of Penn Memory Center patients and caregivers who consent to being queried about potential research studies. We targeted English-speaking adults who self-identified as the caregiver for a patient with a consensus diagnosis of “possible AD,” “probable AD,” or “mild cognitive impairment.” A caregiver was defined as someone who answered “yes” to at least two of the following questions: Do you assist the PLWD with basic activities of daily living (BADLs) such as feeding, grooming, bathing, dressing, and toileting or with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as managing finances, transportation, medication, shopping, or meal preparation? Do you assist the PLWD with decision making? Do you participate in the PLWD’s health care? The purposive sampling strategy sought to achieve balance between: (1) caregivers for PLWD residing in the community; and (2) caregivers for PLWD residing in LTC facilities. Additionally, we stratified our sample by caregiver gender and caregiver-PLWD relationship (i.e., spousal or non-spousal).

Data Collection

Semi-structured telephonic interviews, averaging 90 minutes, were conducted between August 2020 and May 2021 by one research coordinator (MA). The study interview guide (available on request) was developed by the authors and piloted with 3 caregivers, after which minor revisions were made. Interviews covered the following topics: (1) caregivers’ understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) caregivers’ economic, emotional, physical, behavioral, and health-related experiences during the pandemic; (3) the perceived effects of the pandemic on the PLWD; (4) if applicable, experience with hospitalization of the PLWD; and (5) if applicable, experience with death of the PLWD. Slight modifications were made to the guide depending on the PLWD’s place of residence. Demographic information about caregivers and PLWD was collected directly from caregivers.

Qualitative Analysis

Analysis began after data collection and followed a constructivist grounded theory approach.12 This approach recognizes that researchers are immersed in ongoing, contextually situated activities that motivate their research questions and provide them with preexisting theoretical orientations, but also emphasizes the need to let the richness of data push against these orientations. Audio recordings were professionally transcribed. NVivo (QSR International) was used to manage coding. Authors (EL, JC, CC, MK, KH, AP, JK, SS) independently reviewed a subset of transcripts to identify themes, then met to discuss these themes and formalized them in a codebook — a taxonomy for categorizing qualitative data.Reference Glaser and Strauss13 The codebook contained a mix of descriptive categories and interpretive categories.

Using the codebook, two authors (CC, MK) double coded a subset of 10 transcripts and met regularly during this process under the supervision of EL and JC to compare their coding, discuss discrepancies, and refine the codebook to rectify ambiguities, eliminate redundancy, and increase comprehensiveness. Having developed a refined codebook and agreement on its use, CC and MK then single coded the remaining transcripts. Once this initial coding was complete, CC and MK performed focused coding.14 Focused coding identified codes most pertinent to our research questions and developed connections between those codes. Finally, the full team met regularly to undertake explanation development in an abductive processReference Tavory and Timmermans15 informed by prior literature on relevant topics. We posited explanations for the patterns identified in coding, inductively examining these potential explanations to assess their degree of support from the data, and iteratively revised them until we arrived at an explanation best supported by our findings. During explanation development, the team concluded that sufficient data had been collected to ensure theoretical saturation16 — the point at which the addition of new data does not alter the explanation being developed.

Results

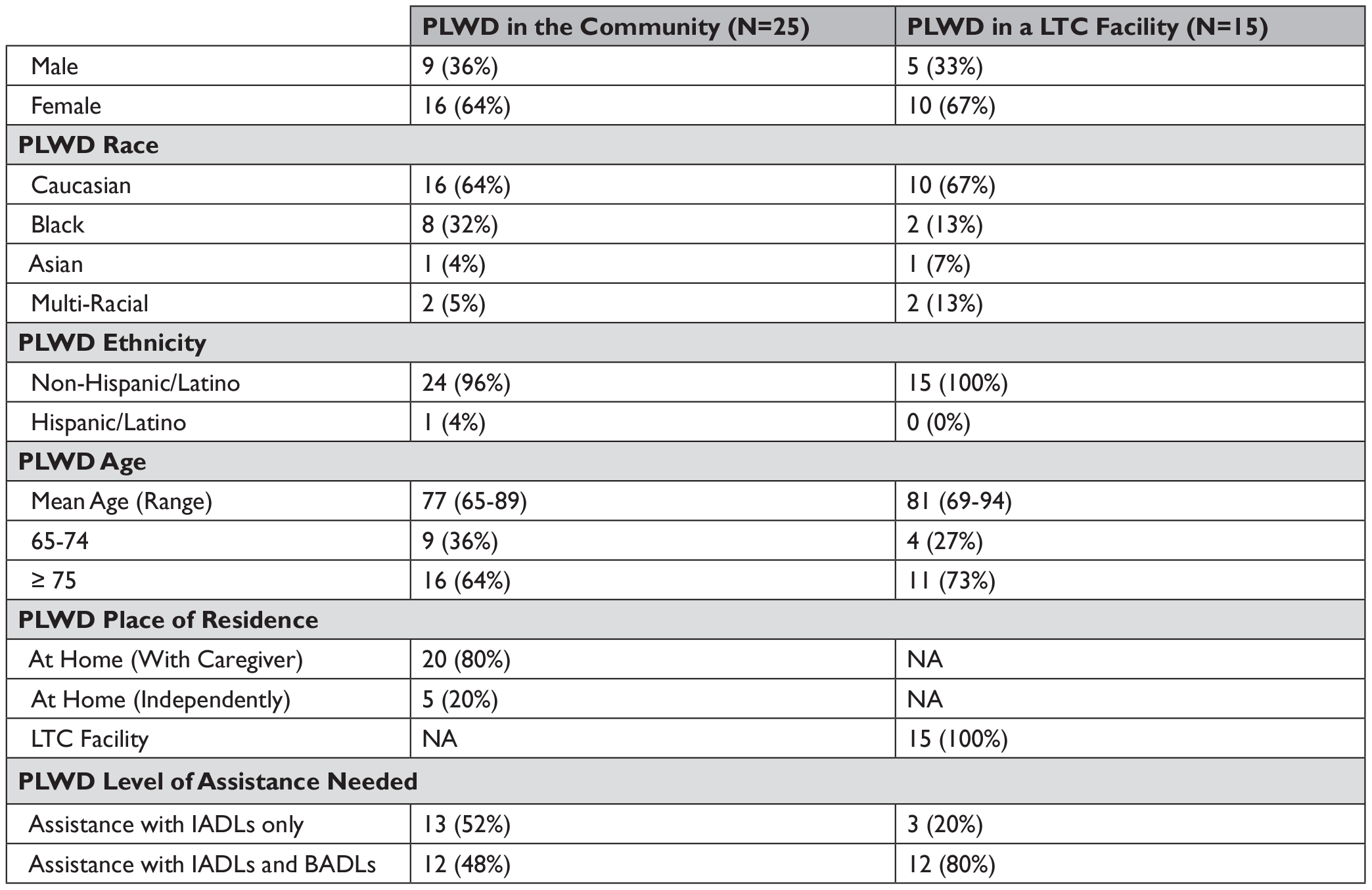

We interviewed 40 caregivers: 25 caring for community-dwelling PLWD and 15 caring for PLWD residing in LTC facilities. Characteristics of the caregivers and PLWD are displayed in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1 Caregiver Characteristics

Table 2 PLWD Characteristics

We first describe pre-pandemic caregiving routines and COVID-19 precautions adopted by caregivers. We then identify three pandemic caregiving trajectories — or pathways — evident in our interview data: (1) continuity between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods; (2) disruption characterized by isolation with a PLWD in the community; and (3) disruption characterized by isolation from a PLWD in a LTC facility. Caregivers on both of the “disrupted” trajectories reported negative consequences for their wellbeing, the wellbeing of the PLWD, and the caregiver-PLWD relationship.

Pre-Pandemic Caregiving Routines

Most caregivers described having well-established routines before the pandemic. They characterized their responsibilities as demanding but generally manageable.

Caregivers for PLWD living in the community typically adhered to a daily schedule structured around completing the PLWD’s activities of daily living (ADLs), a category that includes both IADLs and BADLs. This was exemplified by Diane, who described a typical morning readying her husband for his adult day program: “I would … get him washed and get him dressed. And you know, take him out into the living room and get him his coffee and his medicines.” After describing the rest of her typical day, she concluded, “[T]hen the next day, start all over again.” Caregivers often noted that they would use periods when the PLWD had other sources of care — like an adult day program — to address their own needs, such as exercising or running errands.

Caregivers for PLWD in LTC facilities also described highly routinized care, often detailing how many times a week they visited and how long these visits usually lasted. They provided specific details about both the timing of visits and their activities during those vists. For example, a daughter described visiting her mother:

[T]hree times a week … I would go at lunchtime, and I would help her with her meal and I would usually stay and visit another half hour to an hour, depending. … She likes poetry and short stories, so I would read to her.

These well-established visiting routines reflected, in part, the PLWD’s needs. For instance, many caregivers planned their visits around mealtimes to assist with feeding. Hazel explained that, because her husband had trouble eating, she would “maybe just turn the plate around, push something around a little, help him, you know, get something on a fork.” Additionally, caregivers assisted with “chores, like laundry and sewing a button back on” as well as grooming tasks such as trimming fingernails or shaving faces.

Pandemic Onset

Caregivers understood the COVID-19 pandemic as a serious health crisis. Most described themselves as cautious and many reported fear and anxiety. Caregivers did not want to fall sick for their own benefit, but they also stressed that maintaining their health was essential if they were to continue caring for the PLWD. For example, Gina asked, “If something happens to me, who’s gonna care for [my mother]? [W]hen the sole responsibility relies on you, what happens if you go down?” Further, caregivers did not want to bring the SARS-CoV-2 virus “back home” to the PLWD and get them sick.

Caregivers in both community and LTC settings adopted measures to protect themselves and the PLWD from COVID-19; the two most common were masking and social distancing. Many of these measures were self-initiated rather than the consequence of municipal or state public health directives. Wendell, a man caring for his wife in their home, spoke to the importance of personal responsibility: “You are your own safety man. Regardless [of] what anybody tells you, you are your own safety man.”

Pandemic Caregiving

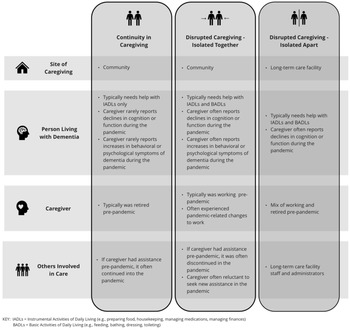

We identified three pandemic caregiving trajectories or pathways; while one is characterized by continuity between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, the other two are characterized by disrupted caregiving patterns and practices, though the mechanism of disruption varied with the PLWD’s place of residence. Figure 1 provides an overview of dyads on each trajectory. These trajectories are not mutually exclusive; select PLWD-caregiver dyads began on one trajectory and transitioned to another trajectory — most often when the PLWD was moved from a LTC facility into the community or vice versa. Most caregivers, however, remained on their initial trajectory.

Figure 1 Overview of the Three Pandemic Caregiving Trajectories

continuity in caregiving

Just over half of the 25 caregivers for community-dwelling PLWD reported that pre-existing caregiving routines were not substantially disrupted by the pandemic. For instance, one caregiver said, “I don’t think there has been that much of a change for [my husband and me].” She explained, “We had our own little … routine, … things I know keep him sorta stable, so I don’t wanna … change that.” Caregivers on this trajectory tended to be caring for PLWD who required assistance with IADLs only, and most reported no worsening of either the PLWD’s cognition and function or behavioral and psychological symptoms in the pandemic. Many of these caregivers were already retired, insulating them from pandemic-related work and financial changes.

Caregivers on this trajectory usually maintained pre-pandemic levels of formal or paid care and informal supports such as assistance from family members and friends in the pandemic, which meant that the level of help the caregiver provided to the PWLD remained steady. For instance, David denied that the pandemic had a “big impact.” He visited his mother daily in her own home but observed that “even if there wasn’t a virus, I would still be here daily.” David described his mother’s home health service as “consistent” apart from “some minor interruptions.” Similarly, Beverly maintained her routine of taking the train to see her sister: “[S]he has a home health aide from 8:30 to 6:30 Monday through Saturday, and Sunday I come.”

These caregivers did not feel as burdened by their caregiving responsibilities as others; several even rejected outright the idea that caregiving was burdensome. Beverly said, “I don’t feel it’s a burden. … [I]n some ways, I weirdly think, ‘So, this is what my purpose was.’” A husband on this trajectory explained, “[T]here’s very much satisfaction in caregiving. … Very much love and compassion and concern in caregiving. It’s a very strong, powerful feeling. It’s not a burden at all.”

Although some caregivers on this trajectory missed seeing friends and family due to social distancing, others described their pre-pandemic social life as limited and found, as a result, that the pandemic had not materially changed their social interactions. Wendell stated, “I don’t have a lot of friends, I never liked a lot of friends.” David noted that his social circle consisted of “my mother, my wife, and myself … [B]ecause our activities were limited anyway [pre-pandemic], … there really wasn’t much to get down about” as a result of social distancing measures.

Caregivers on this trajectory also tended to accept things as they were. Wendell, for instance, emphasized, “You know, you just gotta do what you gotta do.” He added, “I’m not a person that lives by emotions. I look at reality, what causes things, and I prepare for ‘em. I don’t let things catch me off balance.” Reflecting on the pandemic, a woman caring for her husband asserted, “It is what it is. … [T]his is something we have to deal with and if you wanna get through it, you just have to take it one day at a time.”

disrupted caregiving – isolated with the plwd

The remaining caregivers for community-dwelling PLWD, just under half, experienced disruptions in their caregiving routines, accompanied by intensification of the demands placed on them. This intensification appeared driven by at least three categories of pandemic-related changes: changes in the mix of formal and informal caregivers, changes in work, and changes in the PLWD’s care needs. Most caregivers on this trajectory reported experiencing more than one of these changes.

First, caregivers on this trajectory often forewent or lost supplementary sources of care for the PLWD, such as adult day programs, home health aides, or care from other family members and friends. Some declined supplementary care in order to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure; others lost formal care when public health measures shuttered service providers. Some caregivers, like Diane, both declined and lost other sources of care. She explained:

[T]here’s no daycare [anymore] and I was reluctant to hire, say, an agency as a caregiver … because I don’t know … I mean, I assume that they test their employees [for COVID-19]. But on the other hand, I didn’t wanna take any chances.

Absence of supplemental care support required caregivers to increase both the total time spent in caregiving as well as the range of caregiving tasks performed.

Second, caregiving intensification resulted from reconfigurations of work. A majority of caregivers on this trajectory were still in the workforce when the pandemic began. Pandemic-related job changes — like a shift from in-person to remote work — resulted in caregivers spending more time overall in proximity to the PLWD, often while juggling job-related responsibilities. A woman caring for her mother said, “I had to work from home. … Because of COVID, we are all up underneath each other most of the day.” Paul felt fortunate that he could do his job “from home online” but found it stressful to be “working and also at home” with his husband, who had previously spent his days home alone.

Several caregivers exited the workforce at the start of the pandemic; they reported a particularly pronounced intensification of caregiving. Their experiences illustrate how the loss of supplementary care and job changes could interact to increase demands on caregivers. For instance, having lost her husband’s adult day program and feeling reluctant to hire a home health aide, Diane felt compelled to retire earlier than she would have had there not been a pandemic. For Diane, work had been “sort of my form of respite, you know.” While she had caregiving responsibilities before, “it wasn’t 24/7 like it is now.” Gina was laid off: “If this wasn’t COVID, I’d have a job right now and balance, and she’d have her care, and we’d have all these other partners [home health aides] that, you know, would be helping us out.” She finished, “[T]here’s no respite for me.” The economic consequences of exiting the workforce were a further source of strain on caregivers, like Gina, who worried about making ends meet.

Third, caregivers on this trajectory perceived increases in the PLWD’s needs during the pandemic. Pre-pandemic, many of the PLWD already required help with IADLS and BADLs; had pronounced behavioral or psychological symptoms, such as agitation, depression, or shadowing; or both needed help with ADLs and had behavioral or psychological symptoms. As a result, caregivers felt compelled at baseline to watch them “like hawk[s].” Many caregivers speculated that the pandemic had “rushed” the PLWD’s “progression” along the dementia trajectory, further ratcheting up care needs. June, for instance, questioned: “Would my husband have deteriorated so without COVID? You know, I doubt it … but I’ll never know, will I?” She concluded, “[M]y life is just shittier.”

Due to some or all of these three changes, caregivers on this trajectory reported an intensification of caregiving responsibilities, and many described difficulty adjusting to their evolving role. Feelings of frustration and powerlessness were most prominent amongst caregivers reporting the sharpest intensifications. Caregivers expressed this powerlessness as feeling not just “burdened” but “burnt out.” This affected their sense of self and of their relationship with the PLWD. For instance, Paul confided,

I have really had to change my sense of relationship [with my husband]. … I don’t know that it’s necessarily because of COVID. I mean, that just sort of exacerbates everything. … I had a really bad day a couple of days ago. … I was looking at myself and feeling like an unpaid caregiver. And that seems to be the bulk of our relationship. … [I]t’s taken a toll on our relationship and really changed the dynamics.

Likewise, Diane described herself as her husband’s “nurse, not just wife. … And then COVID hit. … I got entrenched in that caregiver role.”

Caregivers on this trajectory often described having little or no social engagement with individuals other than the PLWD and characterized this as a change from the pre-pandemic period. Gina reported that, although she’d had adequate support pre-pandemic, there were now “no family visitors … no friends stopping by.” She described herself as “depressed” and elaborated: “I’m not typically a depressed kind of a person, but I feel isolated. … [M]y support network, it’s, kinda, like, gone. … [M]y own personal life … gone.” She summarized, “My whole identity is, like, gone.” Some caregivers identified online caregiver support groups as a source of engagement, while others missed participating in support groups disbanded by the pandemic.

Negative feelings precipitated by intensified caregiving could, at times, influence interactions between the caregiver and PLWD. For instance, June desired — but did not feel it was safe — to hire an aide to assist with her husband’s mounting care needs and recognized their daughter’s ability to assist with caregiving was quite limited. June reflected:

I’ve lost my temper more because it’s frustrating, … obviously I know it’s not my husband’s fault when he gets aggressive, or he doesn’t really get [directions] … I’m tired of it, so then I’ll get more insistent, and then he gets more aggressive, which is so stupid.

Caregivers felt guilty for “losing their cool” or, as Paul put it, for being “a lot more irritable and perhaps impatient” with the PLWD. Describing herself as “at the breaking point right now,” one daughter worried, “I don’t want the last couple of years of [my mother’s] life to be, oh, those were the two or three years that I fought her every moment we were together.”

There was variation in how caregivers on this trajectory characterized the benefits and burdens of pandemic caregiving. Some saw no benefits. Asked whether she experienced positive effects of being her husband’s caregiver, June replied, “I know … I could make up a story about how … we grew closer and this and [that.] … No, the answer is no.” These caregivers worried that their inability to find a silver lining made them “sound like a horrible person.”

Other caregivers enumerated benefits even as they acknowledged hardships. Gina, for instance, was proud that she cared for her mother in the face of numerous challenges; she asserted that the pandemic had “taught me that I’m stronger than I thought.” Moreover, she noted that the pandemic “gave me … the chance to spend more time with her. And I don’t regret it for one second because when she’s not here, I’ll have all the memories that we created together.” Extra time with the PLWD and the satisfaction of knowing the PLWD was well cared for were commonly cited as positive aspects of pandemic caregiving.

disrupted caregiving – isolated from the plwd

The remaining caregivers — all caring for PLWD in LTC facilities — reported that their caregiving had been disrupted by visitor restrictions intended to protect facility residents and staff. Caregivers appreciated the importance of these restrictions but found it “very difficult” to be cut off from the PLWD. Lois observed that her husband’s LTC facility had “been pretty rigid about following the [COVID-19] protocol. … I’m glad that it’s worked out well, but it’s hard going through that.”

A minority of these caregivers welcomed visitor restrictions as a break from pre-pandemic caregiving routines. Jeff admitted, “I’ll be selfish here. … I would go over there twice a week [pre-pandemic]. And [I] didn’t have to do that anymore. Love my father to death, but you know what, it was one less thing … to do.” Before the pandemic, Hazel had visited her husband “just about every day.” Like Jeff, she found visitor restrictions to be “a little bit of a relief. … In the very beginning it did feel like I could … take a breather.” However, Hazel clarified, “I don’t wanna, you know, make it sound like, ‘Oh, it’s not so bad.’ It is really bad, you know, that you can’t be with a person.” For Hazel and others like her, the initial sense of reprieve gave way to feelings of powerlessness and anxiety as restrictions continued.

Many caregivers spoke directly to the importance of touch and expressed sadness that visitor restrictions had severed this connection to the PLWD. Hazel explained,

[A] sense of touch was really important in our relationship, and that’s missing, and I would love to be able to put my arms around [my husband]. Yeah, touch his face, everything, kiss him. Used to tell him, ‘You just married me for sex, that’s all.’

Even as caregivers were allowed back into LTC facilities, lack of touch persisted in troubling ways. Cliff, a man caring for his wife, described himself as part of “a huggin’ family” before relaying a story in which he was briefly permitted to visit his wife only to find that the LTC facility staff wouldn’t allow him to “physically touch her or anything.” Lois described how a staff member “flew across” the room and yelled at her — “Don’t touch him, you can’t touch him!” — after she patted her husband’s shoulder during what was meant to be a socially distanced visit. This distressed Lois and “totally panicked” her husband.

The meaning of touch was further underscored by the handful of caregivers who lost their loved one during the pandemic. After not seeing her husband for months, Shirley was allowed into the LTC facility as her husband was actively dying. She climbed into his bed and:

I held his hand because … we held hands all the time. And he grabbed my hand. … And I said, ‘I’m going to stay with you until you found your home.’ But by the next day, … he couldn’t grasp anymore. His hands were becoming stiff. … So I just held him. I wrapped my arm around him. … [H]e died peacefully, I think.

In contrast, Tony’s wife died alone, which complicated Tony’s grieving process. He explained that he had “planned it for many, many years that when [she] was imminently going to pass, that I’d be able to see her, hold her hand and all that. And … I couldn’t do that.” Tony lamented, “[T]his damn disease, this damn virus … kept me from being with my wife when she passed” even though she did not have COVID-19.

Caregivers who could not be in-person with the PLWD sought alternative means of connection. One option was to call the PLWD, and many caregivers expressed a preference for video calls via platforms like FaceTime or Zoom. Tony spoke positively about FaceTime calls with his wife, saying “even though I couldn’t get to see [her] in person, I could get to see her, and I could hear her, and I could talk to her.” Yet, cognitive impairment could be an obstacle to such communication. Oscar speculated that his wife “wouldn’t know to speak on the phone” due to being “in the advanced stage of dementia.” Shirley’s husband “had no clue what this little black thing [an iPhone] they were putting in his face [was].”

The ability to speak with the PLWD was generally dependent on LTC facility staff initiating outgoing calls and connecting incoming ones. Tony related the story of a friend whose wife lived in a LTC facility “that never used technology to allow … caregivers to see their loved one.” He concluded: “I think that’s unconscionable. There is no excuse for not using the technology that you have available, unless you’re trying to hide something.” Cliff expressed substantial frustration that staff did not do more to facilitate calls; on occasions when Cliff’s video calls were successfully connected, he often noted changes in his wife’s appearance that prompted worries about the adequacy of her care.

At many LTC facilities, staff would bring residents to a window to visit safely with family on the other side of the glass. As with calls, the appeal of “window visits” was somewhat dependent on the PLWD’s cognition. One caregiver found window visits were “not as good as I thought [they] w[ere] going to be, but then I guess I was being unrealistic about the whole situation. … I’m not even sure [my husband] knows who I am any longer.” In contrast, Shirley valued window visits, as she believed — due to a familiar hand gesture he made — that her husband still recognized her in the days before his death. For most caregivers, window visits were a poor substitute for in-person visits. Jeff was an exception. Even after visitor restrictions relaxed, his preference was to continue window visits with his father and avoid the LTC facility’s COVID-19 testing requirements: “I’ll be honest with you, part of it’s selfish. … I’m a busy person.”

In addition to missing the social and physical aspects of visits, caregivers noted their inability to assist the PLWD with IADLs and BADLs; they were generally eager to resume helping. Shirley asserted that she hadn’t placed her husband in a LTC facility “because I don’t want to take care of him anymore.” Although her husband had passed away by the time of her interview, she speculated that “if [other caregivers] have to go through a rigorous time” to get into LTC facilities, they would gladly do it. Many caregivers isolated from the PLWD echoed that sentiment.

Caregivers reported that the loss of their informal care contributions adversely affected the PLWD’s wellbeing. For instance, without Hazel’s assistance, her husband “lost weight during the lockdown because [the staff at the LTC facility] weren’t helping him eat.” Several caregivers expressed concern about staff turnover, suggesting it compounded the negative effects of visitor restrictions on residents’ care and speculating that remaining staff were shouldering “more and more work.” Some caregivers acknowledged that LTC facility staff were also dealing with significant challenges of their own in the workplace and personal lives. Tony said, “[In] hindsight, expecting the employees to be giving the same level of care during a crisis as the person [with dementia] received before [COVID-19], … it’s expecting too much.”

In the absence of in-person visits and in light of the notable limitations of calls and window visits, LTC facility administrators and staff became caregivers’ primary sources of information about what was happening in the facility generally and with the PLWD specifically. Perceptions of communication quality varied. Some caregivers reported that facility administrators and staff were “responsive” to their inquiries, and this was associated with less caregiver worry and greater trust. For instance, Jeff “didn’t feel like they kept any information away from me. … If I ever had a question, I just called them, and they were very transparent. … [T]hey did a good job with their outreach too.” He said he “never once [had] a concern, never” that his father was getting the care he needed.

Prior to the pandemic, caregivers for PLWD across community and LTC settings described highly routinized caregiving, with established routines contributing to the wellbeing of both members of the PLWD-caregiver dyad. With the pandemic’s onset, caregivers took and were subject to measures to keep themselves and the PLWD safe. For a majority, these measures upended established routines. We identified three caregiving trajectories: (1) continuity in caregiving between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods; (2) disruption in caregiving characterized by isolation with a PLWD in the community; and (3) disruption in caregiving characterized by isolation from a PLWD in a LTC facility. Caregivers on the latter two trajectories reported considerable distress.

In contrast, many caregivers described LTC facility administrators and staff as “not very communicative” or even evasive. Poor communication exacerbated caregivers’ sense of disconnection from the PLWD, as they didn’t “really know what it’s like inside those walls.” It was also associated with greater caregiver anxiety and lower trust in the LTC facility. Despite his sympathy for staff members, Tony was frustrated by the lack of communication and exclaimed, “I have a legal right to know what the devil’s going on.” Lois explained, “I don’t feel like I’m getting all the answers, at least, answers that would satisfy me.” Cliff asserted, “We’re flyin’ blind. … Information has always been very sketchy.” He stated that, in the absence of visitor restrictions, he would have frequently visited his wife’s LTC facility; this would have allowed him to be “in [their] faces and … [and] find out exactly what was goin’ on.”

In extreme cases, caregivers’ concerns about quality of care precipitated changes in the PLWD’s living situation during the pandemic. Hazel, for example, transferred her husband to a new LTC facility after concluding that the first facility was “horrible.” Cliff brought his wife home after determining that “we can do better.”

As visitor restrictions lifted and caregivers reentered LTC facilities, many found the PLWD’s mental and physical status had “declined precipitously.” Caregivers attributed these declines, in part, to the lack of visitors over the preceding months as well as to residents being isolated in their rooms. After an extended time apart, typically measured in months, losses of cognition and function were starkly apparent to caregivers. Oscar speculated that “it affected [my wife’s] cognition … the couple of months that I didn’t see her.” He said, “[W]hen I did see her … I think she had trouble realizing that I was her husband.”

The majority of caregivers on this trajectory had difficulty identifying any positive aspects of their experience. Oscar asked: “How could anybody be positive when their wife is in an institution with dementia?” The few who identified positives often focused on the fact that the PWLD was, despite the threat of COVID-19, still alive. For example, a daughter said of her mother, “[S]he’s still here, which is … a raw blessing … So many, you know, have left here.”

Discussion

This study explored the ways that relationships between American caregivers and PLWD were impacted by the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, caregivers for PLWD across community and LTC settings described highly routinized caregiving, with established routines contributing to the wellbeing of both members of the PLWD-caregiver dyad. With the pandemic’s onset, caregivers took and were subject to measures to keep themselves and the PLWD safe. For a majority, these measures upended established routines. We identified three caregiving trajectories: (1) continuity in caregiving between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods; (2) disruption in caregiving characterized by isolation with a PLWD in the community; and (3) disruption in caregiving characterized by isolation from a PLWD in a LTC facility. Caregivers on the latter two trajectories reported considerable distress.

Previous studies on caregiving in the pandemic have established that public health measures were associated with worsening symptoms for PLWD and increased caregiver burden. Our study adds to the literature by providing context for these findings and further characterizing disruptions to caregiving that contributed to negative outcomes.

Notably, the mechanisms of disruption differed based on where the PLWD lived. In the community, caregivers and PLWD were forced physically closer. In contrast, where PLWD lived in LTC facilities, caregivers and PLWD were kept physically apart. In what follows, we explore these different mechanisms and suggest changes to policy and practice. Importantly, our findings suggest that a “one size, fits all” approach will be ineffective, as different mechanisms of disruption require distinct remedies.

Isolation with the PLWD

The majority of caregivers brought into greater proximity to the PLWD by the pandemic reported struggling to adjust to the intensification of care demands. This is consistent with the concept of role strain or difficulty meeting the demands of the caregiving role.Reference Rozario, Morrow-Howell and Hinterlong17 Role strain is moderated by factors such as preparedness — a caregiver’s perceived readiness for caregiving tasks — and predictability — how well the caregiver can anticipate the PLWD’s needs and changes in the caregiving situation.Reference Yang, Liu and Shyu18 Preparedness and predictability appear relatively lower among caregivers who reported disruption compared to those who reported continuity in caring for a community-dwelling PLWD. Role strain is understood to have various effects, two of which we highlight here.

First, role strain can negatively affect caregivers’ wellbeing. Unrelieved, it can lead to a combination of physical, mental, and emotional symptoms characteristic of burnout.Reference Almberg, Grafström and Winblad19 In fact, several caregivers in our study described themselves as “tired” or “burnt out” by pandemic-induced changes in their caregiving patterns. Role strain can also have deleterious effects on one’s sense of self, including self-esteem and perceived self-efficacy. Role engulfment describes an expansion of caregiving activities “to a point where they have, in effect, restructured and largely taken over the life of the person providing care, displacing or reducing previous activities and involvements.”Reference Skaff and Pearlin20 We saw evidence of role engulfment amongst caregivers reporting the greatest intensification of caregiving in the pandemic. For some, this felt like a loss of self; several caregivers in our sample described feeling that their identity had been fundamentally altered or even lost in the pandemic. Our findings are consistent with prior research showing that a lost sense of self is predicted by problem behaviors or the quantity of ADLs needing attention both generally21 and in the pandemic.22 Socialization with friends and employment protect against role engulfment,23 but in the pandemic, such outlets were not readily available to many caregivers.

Second, role strain negatively affects the wellbeing of PLWD.Reference Etters, Goodall and Harrison24 Caregivers in our sample acknowledged negative effects of role strain on their interactions with PLWD, such as being short tempered. None described situations concerning to us for elder abuse. Yet, abuse of older adults increased around the world, including in the United States, in the pandemic.Reference Makaroun, Bachrach and Rosland25 This trend is particularly concerning as such abuse is thought to be systematically underreported. Known risk factors for being abused include cognitive impairment, social isolation, frailty, and dependence on others for care.26 Caregiver strain is also associated with increased likelihood of abuse.Reference Reay and Browne27 Thus, our data deepen understandings of how public health measures meant to protect older adults from COVID-19 had the unintended consequence of substantially increasing their vulnerability along other dimensions.

As in other studies,28 we found that not all caregivers who experienced intensified caregiving regarded the experience as wholly negative. Some perceived selected aspects of the experience, such as more time with the PLWD and opportunities to make memories, as beneficial. Others described a kind of personal enrichment or character building — for example, finding inner strength — that is consistent with role gain. Caregivers’ appraisals of role strain and role gain are understood to be independently associated with caregiver wellbeing.Reference Rapp and Chao29 Thus, our findings underscore the importance of helping caregivers mitigate the objective demands of their role while also helping them to positively frame their interpretation of these demands and of their abilities to meet them.

Policies and programs that support caregiving are essential to reducing objective demands on caregivers; caring for a PLWD was known to be difficult and burdensome even before COVID-19.Reference van den Kieboom30 These policies and programs should include training to equip caregivers with skills and strategies to maintain a PLWD at home; generous workplace leave policies to ease the dual burdens of work and care; and increased access to respite care to allow caregivers to maintain their own health and wellbeing. Role gain may be enhanced through referrals for social work or caregiver support groups,31 which were helpful to some caregivers in our sample. It is, however, important to recognize that current U.S. payment models typically do not support delivery of services like counseling and coaching for unpaid caregivers, and often will not pay for interventions delivered by social workers.Reference Boustani32 (At the Penn Memory Center, where this research was conducted, the social work team is supported by philanthropy.) New payment models must be developed to support evidence-based, collaborative dementia care models that foster the wellbeing of the PLWD and reduce stain on caregivers. We caution, though, that care must be taken not to overemphasize role gain, which would result in displacing responsibility onto individuals facing crises. Policies should ameliorate the myriad structures that make caregiving objectively difficult, not simply demand that caregivers be “resilient.”

Isolation from the PLWD

COVID-19 ravaged LTC facilities, leading to thousands of COVID-19 cases and deaths among residents and staff.Reference Grabowski and Mor33 Many facilities reacted by banning or severely restricting visitors. Such measures kept family caregivers out, potentially undermining care for PLWD.34 This eroded PLWD-caregiver relationships, with physical and emotional repercussions for both members of the dyad. We hypothesize several reasons for this.

First, caregivers for PLWD serve as “an invisible workforce” in LTC facilities, helping with tasks such as feeding and grooming.Reference Coe and Werner35 Visitor restrictions increased unmet care needs at a time when LTC staff were already under considerable stress. PLWD may be particularly susceptible to changes in care delivery. This is consistent with findings that COVID-19 was associated with excess mortality among Medicare enrollees with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias living in nursing homes, even in areas with very low COVID-19 infection rates.Reference Gilstrap36

Second, loss of family oversight may have lowered the quality of care received by PLWD. Unfortunately, the quality of nursing home care is a longstanding challenge. Despite numerous state and federal initiatives, “low quality and understaffing remain endemic” in the United States.Reference Konetzka37 Caregivers in our sample were understandably worried about conditions inside LTC facilities, particularly when there was a perceived lack of transparency. Some described in-person visits as a means of holding staff accountable for high-quality care and lamented the loss of this oversight mechanism. Their intuitions are consistent with research showing that having no visitors is associated with worse care quality for nursing home residents with advanced dementia.Reference Grabowski and Mitchell38

Finally, social isolation can be harmful to health when prolonged.Reference Plagg39 Caregivers attributed PLWDs’ cognitive and functional losses — including the inability to recognize the caregiver — in part to a lack of visitors. Pre-pandemic, caregivers’ visits included activities, like reading poetry and hugging, that tethered the PLWD to their ‘old self.’ These activities and intimacies have benefits for PLWD wellbeing, but also moral value in affirming identity, promoting dignity, and supporting the PLWD-caregiver relationship as memory slips away.

It is important, moving forward, to acknowledge the medical and moral value of informal caregivers in LTC facilities and to find ways to actively support them in fulfilling their desired roles in the lives of PLWD. This will require better enumerating and, subsequently, better balancing the risks and benefits of ostensibly protective measures like visitor restrictions. Restrictions may at times be unavoidable; however, they should be time-limited and, when possible, include carveouts for particularly vulnerable groups such as individuals who are dying or who need assistance completing BADLs. Contrary to what happened across much of the United States,Reference Halley and Mangurian40 caregivers should be prioritized for receipt of interventions like vaccines and supplies like personal protective equipment that make it safer for them to continue or to resume caregiving in public health emergencies. Looking beyond such emergencies, our findings underscore the importance of continuing efforts to improve nursing home quality and of identifying better means of protecting and advocating for PLWD who are unbefriended (i.e., who lack capacity and have no family members or surrogate decision makers) and, therefore, particularly vulnerable to poor care and poor outcomes.Reference Chamberlain41

When caregivers cannot be with the PLWD in person due to visitor restrictions or personal circumstances, meaningful alternatives to maintaining dyadic relationships should be identified. Many caregivers hailed the use of technology — such as Zoom or FaceTime — as a means of fostering connection. Moreover, even when it was difficult to have a meaningful conversation, video calls afforded the caregiver a welcome chance to see the PLWD and gain insights into their physical state. But technology alone is insufficient to bridge the gulf between caregivers and PLWD. As others have also recognized, PLWD have limited abilities to use phones or other communications technology and will generally require assistance.Reference Kyler-Yano42 Technology needs to be delivered in the context of adequate supports, such as orienting a PLWD to the screen and coaching them through a call. Though this can add work for LTC facility staff, its benefits likely justify associated burdens; it could promote increased interaction between residents and families, as well as promote trust in LTC facilities’ quality of care.Reference Roberts and Ishler43 LTC facility administrators should ensure adequate resources and institutional policies to foster these connections.

Communication between caregivers and LTC facility administrators and staff is also important, as it allows families to monitor and advocate for the PLWD, fulfilling aspects of their desired roles.44 Although administrators have described spending additional time communicating with caregivers in the pandemic,45 many caregivers we interviewed felt communication with administrators and staff was inadequate. A perceived lack of transparency was associated with caregiver anxiety and could fuel the caregiver’s mistrust or reinforce their distrust in the LTC facility. Our data suggest that facility-, resident-, and family-level attributes all affect the level of family involvement in a PLWD’s care; among these, a facility’s approach to communication with caregivers is among the more readily modifiable. LTC facility administrators should develop and implement robust and proactive communication plans — not limited to emergencies — because evidence shows that “constructive staff-family relationships depend on communication” and that communication has positive effects for LTC facility residents, family caregivers, and staff.46

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the study population was limited to caregivers for PLWD who had well-defined diagnoses and were seen at one memory center in the Mid-Atlantic where patients and families are generally socioeconomically stable and receive support from the memory center. The responses elicited may not reflect the views of caregivers more broadly. Second, during recruitment, some caregivers declined to participate because they did not have enough time. This may bias our findings towards describing a more favorable experience for caregivers during the pandemic. Our study thus likely underrepresented people who were particularly overwhelmed. We did not interview PLWD but rather relied upon caregiver reports; thus, our perspective on the PLWD-caregiver relationship is derived from caregivers’ perspectives. Finally, caregivers were interviewed once during an evolving public health crisis; the experiences are highly inflected by when they were interviewed.

Conclusion

PLWD were protected from COVID-19 by public health measures and institutional policies, but at what cost? PLWD are vulnerable in a multitude of ways; steps taken to address some aspects of vulnerability may inadvertently increase vulnerability along other dimensions. Disrupted care resulted in suffering for many PLWD and their caregivers, though the causal mechanisms varied depending on whether the pandemic forced the dyad members together or apart. In and beyond the pandemic, it is essential to develop policies and interventions that center care structures and supports on the dyad to maintain the wellbeing of the PLWD and to promote the wellbeing of the caregiver.

Note

This work was supported by the Thomas G. Roberts, Jr., M.D. and Susan M. DaSilva, D.N.P. Giving Fund, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54AG063546, which funds the NIA Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s Disease and AD-Related Dementias Clinical Trials Collaboratory (NIA IMPACT Collaboratory), and NIA P30-AG-072979. Dr. Largent is supported by the NIA (K01-AG064123) and a Greenwall Faculty Scholar Award. Dr. Stites is supported by the Alzheimer’s Association (AARF-17-528934) and the NIA (K23-AG-065442). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.