On May 12, 1983, New York City Ballet (NYCB) premiered Jerome Robbins's Glass Pieces, titled after its score by Philip Glass. The work was the first by a major ballet company to feature minimalist music. Its pulsing rhythms, cool performance demeanor, and grid-paper backdrop seemed to set out a bold new path for NYCB, which was reeling from the death of company founder George Balanchine. For decades, both NYCB and American ballet writ large had been dominated by Balanchine’s modernist style, grounded in his collaborations with composers such as Igor Stravinsky.Footnote 1 In choreographing Glass’s music, Robbins not only hitched the company’s wagon to a newly minted musical star, but he also established a way of making ballet for this post-Balanchine era. Although Robbins's choice of Glass maintained the centrality of contemporary music to the NYCB aesthetic, the shift from modernism to minimalism signaled a new direction for the ballet.

Most importantly, the change in music necessitated a profound shift in dealing with both time and subjectivity onstage. This happened on very small time scales, as the relentless pulse bound the dance to a machine-like pace, but it also happened on larger time scales, since minimalist music eschewed classical forms and thematic development. To deal with this new style of music, Robbins turned to the work of New York City's postmodern choreographers. In doing so, he created what I argue is one of the earliest works of contemporary ballet, a genre that has recently been labeled and explored in dance studies by Jill Nunes Jensen and Kathrina Farrugia-Kriel. This period of ballet dates from the early 1980s onward and is, in their words, “rooted in and resistant to tradition.”Footnote 2 Jensen and Farrugia-Kriel argue that it is difficult to define contemporary ballet aesthetically, in part because ballet has become global. I agree that contemporary ballet is multifaceted, but I believe that some trends can be identified, especially within a defined set of geopolitical boundaries. I argue that music holds one of the keys to understanding the stylistic shifts in North American and European ballet over the past 40 years. Many contemporary ballets in the United States, Canada, and Western and Central Europe are staged to minimalist or postminimalist music. Concerns around time and subjectivity, which arose first in Glass Pieces, are central to the genre today.Footnote 3

Glass Pieces also represents an early step on the surprising path that minimalist music took during the 1980s. Prior to the mid-1970s, minimalist music, like postmodern dance, was confined to small, avant-garde or visual-art venues and was associated with the U.S. counterculture. In the late 1970s, wealthy, high-status artistic institutions began staging works by minimalist composers, especially Glass and Steve Reich.Footnote 4 These high-status institutions, however, did not hold the same artistic and political philosophies as the minimalist composers working in loft spaces in the Village. Along with the move to Lincoln Center came a resignification of what postmodern artistic techniques could mean. Whereas previously minimalist music had helped postmodern choreographers create works that celebrated everyday movement and equality among dancers, for Robbins and other artists of the 1980s minimalist music created a sense of urban propulsion.Footnote 5 Robbins was not the first person to make this connection. Geoffrey Reggio's environmentalist film Koyaanisqatsi had done so a year previously.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, Glass Pieces reaffirmed the new ties between minimalism and the modern city. In the process, it established a way of hearing minimalist music that worked for the ballet.

In order to examine this transitional moment in ballet and minimalist music, I have combined archival research with interviews and analysis. In the archive, I have relied on Robbins's papers, including his written analysis of Glass's music. I also interviewed a number of the original cast members, including the work's lead soloists, Maria Calegari and Bart Cook. In addition to being a dancer, Cook was Robbins's longtime repetiteur for Glass Pieces and thus had insights into the choreographic process and the difficulties of staging the work. I have combined these sources with an analysis of Glass Pieces, particularly paying attention to the ways in which the choreography responds to elements in the music.

The Crisis at NYCB

Glass Pieces was, in part, a reaction to the passing of George Balanchine, whose death left an immense power vacuum at NYCB. Robbins began working on the ballet in late 1982 when Balanchine was ill and debuted it only a few weeks after his death on April 30, 1983. During these months, there was concern inside and outside the company about the future of ballet. Balanchine's obituary in the Washington Post remarked that “For many of those immersed in the dance world in recent decades, the idea of ballet without George Balanchine has seemed inconceivable.”Footnote 7 Cook said that, at the time, NYCB “sort of felt abandoned,” and Calegari echoed that the company was “lost.”Footnote 8 Much of the responsibility for the organization's future fell to Robbins, who had been one of NYCB’s leading choreographers since the 1960s. At the same time, there was a power struggle behind the scenes, as debate raged among board members and the company’s administrative director over who would succeed Balanchine. Robbins was one serious candidate, but his rival was Peter Martins, the golden-haired principal dancer whom Balanchine had started to mentor in his final years.Footnote 9

Robbins began his career as a ballet and musical theater dancer during the 1930s and 1940s. His breakout success as a choreographer came with the 1944 Fancy Free, to music by Leonard Bernstein, about three sailors on leave in New York City during World War II. Later that same year Bernstein and Robbins expanded the short ballet into the Broadway hit On the Town. The theme of modern life in New York City remained central to Robbins's work in both ballet and musical theater for the next decade and a half. This period culminated in 1957 with the musical West Side Story and a year later with the ballet New York Export: Opus Jazz. His work at NYCB during the later 1960s and 1970s, however, took a turn for the classical. Many of his most successful ballets for the company were abstract works choreographed to the music of J.S. Bach and Frédéric Chopin.Footnote 10

Glass Pieces thus represented a return to the themes of Robbins's earlier career but not necessarily a return to its artistic techniques. Instead, Robbins took inspiration from the city's Downtown artistic scene, where Glass had emerged as a major figure in the 1970s.Footnote 11 Prior to 1976, Glass was considered an avant-garde composer of moderate success. He wrote most of his music for his namesake Philip Glass Ensemble, which performed concerts in small venues like the FilmMakers’ Cinémathèque, the Public Theater, Queen's College, and the New School. In 1976, Glass created the opera Einstein on the Beach in collaboration with Robert Wilson, and it succeeded beyond all expectations. He followed up this work with two related operas on biographical subjects, Satyagraha (1980) and Akhnaten (1983).Footnote 12 In 1982, the composer released his namesake album Glassworks, which sold almost 200,000 copies in 5 years. In the same year, he also garnered attention for Koyaanisqatsi.Footnote 13

Robbins was well aware of Glass's newfound fame and had for a while been interested in his music. Robbins was friends with Wilson—they were both theater directors—and thus was present for the first, “friends only” performance of Einstein on the Beach. Indeed, Robbins was even involved in bringing the work to the Metropolitan Opera House following its European tour, and he likely saw Satyagraha twice: In the Netherlands for its premiere run and in the popular 1981 production at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.Footnote 14 In addition, Robbins regularly attended performances in the Downtown dance scene, where some choreographers used minimalist composition in their works.Footnote 15 In 1979, he donated $500 to help fund Dance, a collaboration between Glass, postmodern choreographer Lucinda Childs, and visual artist Sol Lewitt.Footnote 16 For all the composer's fame, though, the impetus for the collaboration actually came from Glass, who invited Robbins to direct the American premiere of Akhnaten.Footnote 17 The two artists met a number of times to discuss the production, but Balanchine's death and the succession problems at NYCB left Robbins without the time to direct an opera.Footnote 18 As a result, he turned down the opportunity but decided to use a selection of Akhnaten for a new ballet.

Time and Subjectivity in Ballet and Postmodern Dance

The opening of Glass Pieces places the ballet in a highly abstracted New York City. An organ and woodwinds play rapid alternating eighth-note runs and triplet arpeggios. In these opening seconds, Glass's music already challenges the traditional style of NYCB choreography as developed by Balanchine. Balanchine created most of his works either to modernist scores by composers such as Stravinsky and Paul Hindemith or to nineteenth-century scores by composers such as Pyotr Tchaikovsky and Johannes Brahms. Music's greatest role in this aesthetic was to regulate time. Balanchine relied on music to provide a clear pulse to unify his dancers, to suggest interesting rhythms, and to give large-scale formal structure to his works. This last point is particularly important because he favored abstract ballets. In Balanchine's works, musical form takes the place of narrative as a way of organizing the viewer's experience. As Balanchine himself put it, “Music puts a time corset on the dance.”Footnote 19

Because the music structures time in Balanchine's works, it also gives his abstract choreography a sense of subjectivity. As musicologists Naomi Cumming, Scott Burnham, and Susan McClary have argued, instrumental works can create a sense of character. Time is fundamental to this process. As a musical theme is altered and recollected over the course of the work and as it confronts other musical elements, these changes help create the sense that the theme is a musical person.Footnote 20 Balanchine's approach to dance–music relationships physicalizes this process. In his choreography, the tight interweaving of choreographic and musical form means that dancers often embody the work's musical themes.Footnote 21 Robbins also used this type of organization on and off in his works. From the first movement of his 1975 ballet In G Major to Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto in G, for example, appearances of the slower second theme are associated with either one of the two solo dancers dressed in white.

Minimalist music provides a serious challenge to this way of organizing time and subjectivity in dance. The music changes only gradually, with long periods of stasis. There is little or no emphasis on thematic development. Sometimes there is no melody at all.Footnote 22 Relatedly, theorists have argued that minimalism avoids the type of subjectivity found in earlier modernist music. Keith Potter, for example, considers two of the fundamental traits of musical minimalism to be “the avoidance of previous notions of musical expression, in particular of music being in some sense about the composers themselves” and “the reconsideration of […] narrativity.”Footnote 23 Wim Mertens writes that minimalist music avoids teleology and thus narrative.Footnote 24

Although minimalist music's model of time and subjectivity contrasted sharply with the musical techniques harnessed by Balanchine, it dovetailed well with the methods used by postmodern choreographers. Postmodern dance, as defined by Sally Banes, was a genre of concert dance created in the 1960s and 1970s by a network of artists working around the Judson Dance Theater in New York. Banes tends to define the genre more through artistic networks than philosophy or style, but in general the postmodern choreographers were interested in egalitarianism, natural movement, and self-reflexive theatricality. One of the major goals of postmodern choreographers was to democratize dance by using ordinary movement and avoiding solo roles or virtuosity.Footnote 25 Yvonne Rainer, who was the major theorist of the movement, wrote an essay in 1965 in which she set out an aesthetic for, as she called it, “minimalist” dance. The cornerstone of the essay is a chart juxtaposing those aspects of traditional dance that postmodern choreographers could abandon and a series of techniques that they could use as substitutions. Rainer argues for the elimination of the “hierarchical relationship of parts,” along with “character,” “development and climax,” and “the virtuosic feat.” In their place, she argues for such techniques as “simplicity,” “human scale,” “equality of parts,” and “neutral performance.”Footnote 26

Postmodern choreographers rebelled against the close relationships between music and choreography in both ballet and modern dance. For some of them, music was a concern because it could lead to a sense of subjectivity, theatricality, or hierarchy, which they actively avoided in their works. Many drew from the ideas of choreographer Merce Cunningham, who avoided purposefully arranging simultaneities between his dance and its music. Indeed, in some of his mature works with partner and composer John Cage, each artist created his respective half only to an agreed-upon temporal duration, without any reference to the other's work. Any moment-by-moment interactions between music and dance were then the result of chance.Footnote 27 Many postmodern choreographers followed in Cunningham's footsteps, some going even further to push music out of their works, particularly as an organizing force. Several choreographers, including Childs, Simone Forti, Trisha Brown, and Douglass Dunn, staged works to partial or complete silence. Others used spoken language as a soundtrack.Footnote 28 Still others treated all music as interchangeable. For example, sometimes these choreographers would buy a stack of records and allow the stagehands to pick out which record to play—or even whether there would be music at all.Footnote 29 At one point Rainer even, perhaps jokingly, called herself an “unabashed music hater.”Footnote 30

For those postmodern choreographers who wanted to use music more actively but who had similar concerns about subjectivity, minimalist composition provided a solution. For example, almost all of Childs’ dance works of the 1970s were staged to silence. Her decision to collaborate with Glass and LeWitt for their 1979 Dance, and thus to use music and a backdrop at all, was considered a surprising return to theatricality and grandeur. Even Dance, however, still complied with the major tenets of Rainer's “minimalist” philosophy, aided in part by the minimalist nature of its score. Glass's music for Dance lacks thematic development, and Childs's dancers avoid expression and subjectivity. Every single dancer, male or female, performs the same step vocabulary and no dancer is singled out over the others.Footnote 31 In this work, as well as in her 1984 “Field Dances” for Einstein on the Beach, Childs uses organizational techniques similar to those of Glass but not always aligned temporally, so that the dance and musical phrases can match up in very large-scale structures but on a moment-to-moment level move in and out of sync with one another.Footnote 32 Other postmodern choreographers, including Laura Dean and Meredith Monk, composed their own minimalist scores to match their style of movement.Footnote 33

Postmodern Techniques Meet Ballet in Glass Pieces

Unlike the postmodern choreographers who inspired him, Robbins did not use minimalist music to create an egalitarian practice. Instead, he seems to have seen the techniques of postmodern dance as a symbol of the modern city. In Glass Pieces he interprets the everyday movement from postmodern dance as a sign of contemporary life. Postmodern dance, with its egalitarian ordinariness, is generally given to the corps de ballet. Their movement becomes a background to highlight the virtuosity and expressivity of the soloists. Minimalist music is used to suggest modernity and urbanism rather than democratization. Robbins also ties his dance steps to Glass's music in ways that suggested individual, even heroic, subjectivity.

Glass Pieces is divided into three sections. Within each one, Robbins stages a different relationship between the groups of dancers—corps and soloists—and the music's time schemes (see Table 1).Footnote 34 In the first section, choreographed to “Rubric” from the album Glassworks, the corps uses the techniques of postmodern dance to act as everyday New Yorkers. In front of a graph-paper backdrop, the dancers walk haphazardly across the stage. They are dressed in costumes designed by Ben Benson to evoke a combination of practice outfits and low-key streetwear (Figure 1).Footnote 35 The corps follow Rainer’s plan, rejecting a hierarchical relationship of parts, phrasing, and development, and substituting everyday movement, neutral performance, equality of parts, and uninterrupted movement. They interact very little with the Glass score, and not at all with its pulse. Robbins instructed the dancers to look like commuters in Grand Central Station at rush hour.Footnote 36 In my interviews with the original cast, a number of dancers agreed that the experience onstage mimicked the experience of living in New York. In original cast member Jock Soto's words, “It's Times Square, it's the subway, people flying… and all the three thousand people that come to the theater, they're doing the same thing, walking quickly to get to a performance.”Footnote 37 Fellow original cast member Deborah Wingert emphasized how much Robbins instructed them move ever faster and faster; in fact, the dancers felt so harried that they joked that Robbins was telling them, “Don't rush—leave later and get there earlier.”Footnote 38

Figure 1. NYCB dancers in the opening section of Glass Pieces. Photographer: Paul Kolnik. Used with permission.

Table 1. Summary of Robbins's approach to pulse and long-form development in the three sections of Glass Pieces

Nevertheless, these are not Robbins’s only dancers. The soloists use the music in a more traditionally balletic way, with their steps timed to the pulse and individual movements matched to specific gestures in the music. About 40 seconds in, a woman in a metallic yellow unitard leaps onstage, her arms stretched up in a V as she bends her knees deeply. Robbins described the figure as “a steel angel from outer space.”Footnote 39 Only a few beats later, a man joins her and the two perform a virtuosic duet through the dispersing crowd. They stride forward in deep lunges over sections of music with rising eighth-note patterns, the lines in the music matching the dancers’ forward momentum. To the orchestra's swirling triplet arpeggios, the dancers perform tight turns, the circular motion mimicking constant upward and downward patterns in the score. Over the course of “Rubric,” as the soloists return, they are joined gradually by two other pairs. In each subsequent section, the soloists build on the movements of the previous ones, creating a sense of thematic development in the gestures.

On a larger formal scale as well, Robbins matches Glass's work, again drawing on the techniques of modernist ballet. In order to keep track of the score, Robbins created diagrams of the music's form on graph paper, primarily focusing on changes in the texture.Footnote 40 Each box in the grid represents one half note, approximately one count of the music in dancers’ terms. The diagram is structured so that each row has two sets of counts, usually adding up to four bars per row.Footnote 41 Each box is filled with a graphic pattern representing the musical texture being played at that moment. As an example, eighth notes grouped into rising slurred pairs are represented by an ascending dotted line. A wavy line represents a swirling triplet texture. This presumably allowed Robbins to keep the counts and their associated textures in mind, and it reveals some interesting patterns in the music, as when Glass plays with a back and forth between eighth notes and triplets at rehearsals six and seven (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Jerome Robbins's diagram of “Rubric.” (a) Philip Glass, “Rubric,” rehearsals six and seven. (b) Jerome Robbins's diagram of “Rubric,” copy provided by Bart Cook. (c) Close up of Robbins's diagram, rehearsals six and seven, copied by author for clarity. The far left numbers in squares indicate rehearsal numbers in the score. The circled eight refers to the grouping of counts for the section, as do the other eights distributed over the diagram. The free-standing 3 and 4 refer to the third and fourth set of counts for this block of choreography. (a) and (b) are from the personal collection of Bart Cook. Used with permission.

Altogether, Robbins's graph illustrates the large-scale form of the music as a repeating verse–chorus structure. The choreographer labeled the 32-measure section of music starting at rehearsal three with the word “chorus” and did not diagram its returns in the same level of detail. These chorus sections are characterized by triplet patterns in the organ and woodwinds, underneath which a pair of French horns play long two-note intervals. The long notes of the French horns create the sensation that this is possibly a melody, though if so, it is a very simple melody. Another phantom melody, almost the same as the horns, can be heard in the flute and organ parts. These phantom melodies are subjective, and they depend on the listener to pluck them out of the shifting textures.Footnote 42 I hear them strongly, however, in multiple different performances, and given that Robbins labeled these with the word “chorus,” I imagine that he heard something similar.

In the dance, the corps de ballet perform these choruses, whereas the verse sections are performed by the soloists. Over the course of “Rubric,” the corps moves closer and closer to the style of the soloists by adding more movement timed to the pulse of the music. In the second chorus, the corps performs a sudden unison turn in the middle of their hectic commute. Later they do a stutter step. When the musical chorus appears for the final time, it is expanded to forty-eight bars, tripling its length. In this conclusion, the corps dancers give up their unmetered walking for metered choreography. The soloists first perform a series of movements and then groups of the corps perform the same steps in canon. By merging the commuters into the more balletic style, Robbins reinforces the sense of formal closure at the end of the section and hints that his allegiance lies with the structural principles of ballet over those of postmodern dance.

In the second section of Glass Pieces, Robbins restructures the relationships between corps, soloist, and musical time. The score for this movement, the track “Façades” from Glassworks, is much slower paced than “Rubric.” Violas and cellos rock back and forth in triplet patterns, forming a melancholic and nonfunctional harmonic progression. Over cycles of this accompaniment, the soprano saxophones introduce a slow, yearning duet. One saxophone begins with long structural pitches and over the course of a few repetitions adds in faster runs. In the middle of the piece, the saxophones begin to interweave their melodies before fading back into slower material. Despite the somewhat increased surface motion in the middle section of the piece, the melody remains harmonically static and aching, bound by the repetitions of its initial, structural pitches.

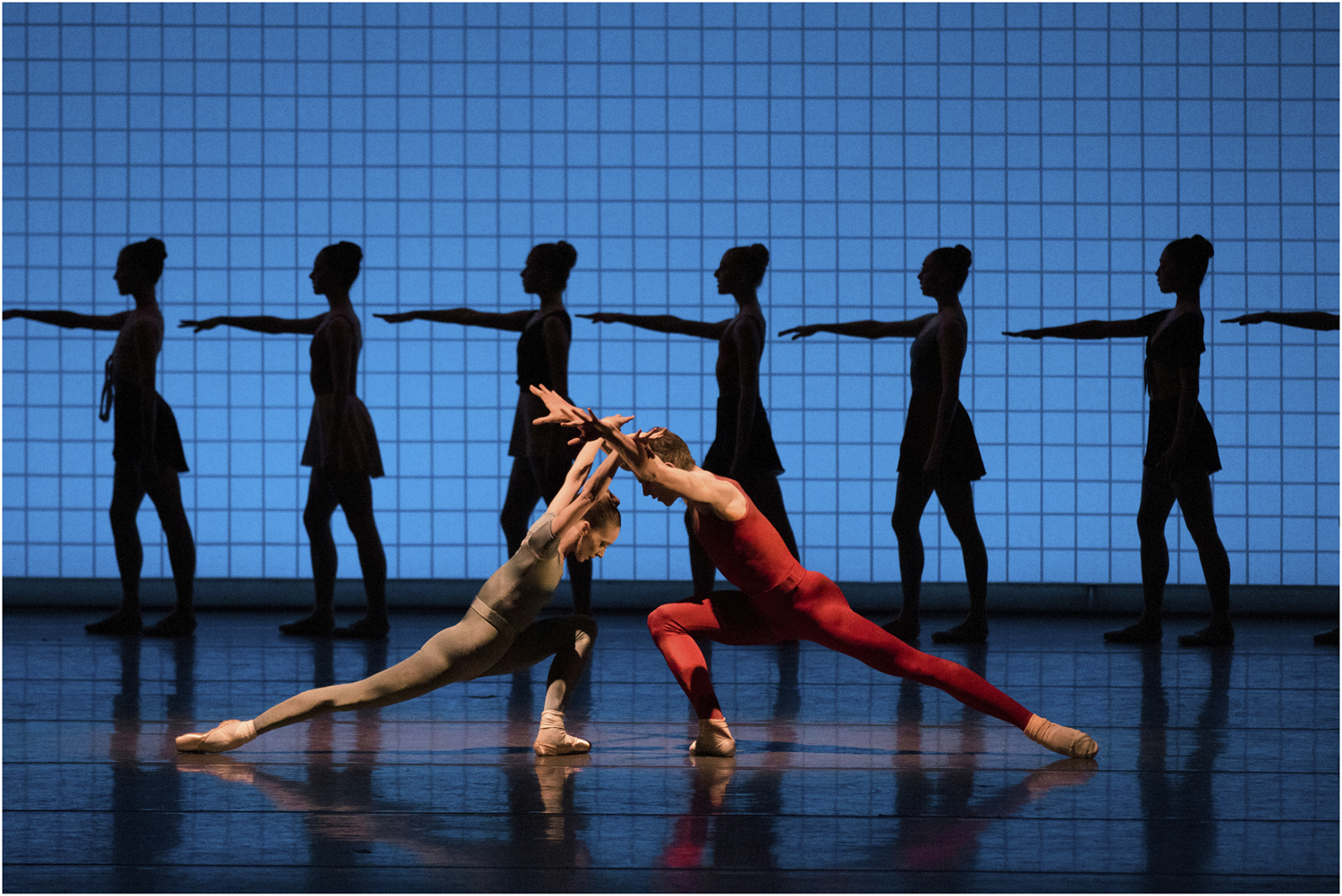

As in “Rubric,” Robbins juxtaposes a corps of dancers using more postmodern movements against soloists who maintain balletic movement. Unlike in the first section, it is the corps that is bound to the pulse this time, while the soloists are relatively free of it. The corps de ballet appears from upstage left. The lighting, designed by Ronald Bates, is a deep blue and the corps are backlit so that they appear only in silhouette. They halfheartedly bob forward in time to the music, sometimes turning to shuffle sideways and then reorienting themselves to trudge further across the stage (Figure 3). They perform the same exact steps over and over, only changing their arm movements, which drift up at the elbow in the fourth iteration of the step sequence and then up to their shoulders on the seventh. The choreography is slightly shifted during the middle of the section to ensure that the line is always onstage, moving slowly from left to right, until the lights fade to black at the end. Throughout, they continue both to perform rigidly in time with the pulse and to exhibit a lack of individual subjectivity. Indeed, as silhouettes performing in unison, it is impossible to distinguish any one of them as an individual. The effect is unsettling; the women seem to be simultaneously an assembly line and its products.Footnote 43

Figure 3. Maria Kowroski and Russell Janzen with the NYCB corps de ballet in section two of Glass Pieces. Photographer: Paul Kolnik. Used with permission.

The section's two soloists, on the other hand, have a much greater sense of subjectivity. Though they are still relatively passive in their facial expressions, their full faces and bodies are illuminated, and their choreography is expressive, even tender at times. Their duet is dominated by long drawn-out extensions and partnered lifts to match the long saxophone melody. The feeling of slow expansion is key to the soloists’ movements in “Façades,” even in moments of stillness. Calegari, the original female soloist, recalled that they exerted a great deal of effort to hold still in a dynamic manner.Footnote 44

In this section, Robbins merges postmodern dance specifically with the ballet blanc, a genre of nineteenth-century ballet in which the action takes place at night, often in the woods or in a dream. The dark blue lighting in “Façades” is similar to that used in the ballet blanc. The relationship between the soloists and corps is also the same; a central heterosexual couple is surrounded by dozens of women from the corps de ballet, whose movements echo those of the lead ballerina.Footnote 45 By merging postmodern dance with the ballet blanc, Robbins establishes a new meaning for the postmodern techniques of repetition and everyday movement. In postmodern dance, these techniques were strongly associated with an egalitarian and even feminist practice.Footnote 46 In “Façades” the same techniques become hierarchical, a way of differentiating the corps from the virtuosic soloists.

The need to regiment the corps dancers in “Façades” provided the inspiration for the work's grid paper backdrop. During rehearsal, the corps dancers struggled to remember their steps, which contain a number of small but noticeable changes within a highly repetitive framework. Moreover, Robbins played with multiple different versions of the step pattern during the choreographic process, and many dancers had difficulty keeping track of them. Getting it wrong could incur the choreographer's legendary rehearsal anger.Footnote 47 In order to help the corps remember their choreography, Cook made a graphical representation of their part and projected it onto the wall behind the dancers so that they could look at it during rehearsal. When Robbins saw this, he was struck by the image of the corps dancing in front of the graph paper and decided to use a similar graph pattern as the backdrop for the entire ballet.Footnote 48

As a result, the ballet takes place almost literally within a graphical representation of the music and choreography. In making this choice, Robbins followed the example of other minimalist artists, musicians, and choreographers. Childs, for example, whose work Robbins knew well, used grid paper to draft her dances. For her 1979 Dance, which juxtaposed a filmed and live version of the same choreography, designer Sol Le Witt projected a wide grid on the film version.Footnote 49 The grid also reflects Glass's music of the 1980s, what Kyle Gann calls “grid postminimalism,” a style of postminimalism that placed “every note on a semiquaver or quaver grid.”Footnote 50 Like Balanchine's metaphorical corset, the grid is also a technology of discipline. However, although corsets discipline individual bodies, grids discipline larger and often more ineffable things: populations, traffic patterns, large spaces, even information. In this case, the backdrop literally helped order the bodies of the corps de ballet.

The grid in Glass Pieces also suggests a larger scope of control, a technology that disciplines not only the bodies of the dancers onstage but all of the modern city. Indeed, the “grid” has specific resonance in the context of New York City, which is famously built on a grid pattern of streets. It seems likely Robbins's decision to use the grid paper as the ballet's backdrop was supposed to resonate specifically with New York. As such, he may have been drawing on the imagery in Koyaanisqatsi. During the second half of the film, in a section called “The Grid,” Reggio sets Glass's music under time-lapse footage of modern cities, emphasizing fast-moving traffic patterns and bright neon lights.Footnote 51 By setting his footage of urban traffic to the sounds of Glass's music, Reggio became one of the first artists, or perhaps the very first, to associate minimalist music's grids with modernity and machines.Footnote 52 In the years since, this association has become very commonplace in film and television. In 1983 when Robbins staged Glass Pieces, however, it was still a very new idea.

It is notable that although the dancers may have been mimicking the motions of New York City commuters, they themselves did not look like any type of cross section of the city: All young, highly athletic, and overwhelmingly white in a city with a racially diverse population. As dance scholar Rebecca Chaleff argues, postmodern choreographic interest in ordinary bodies paradoxically meant that they almost exclusively created works for white dancers, because they saw white bodies as unremarkable.Footnote 53 This is all the more jarring in face of the fact that, as both Brendan Dixon Gottschild and Thomas DeFrantz have argued, the “cool” detached aesthetic central to modernist ballet, postmodern dance, and contemporary ballet alike comes from Black dance forms, as observed by white choreographers.Footnote 54 In using these ordinary movements with his largely—though not exclusively—white cast, Robbins reaffirmed the ways that whiteness was seen as ordinary.

In fact, Robbins's ballet only breaks out of its self-conscious modernity in the third section through the balletic language of exoticism. The music in this section, “Akhnaten,” comes from the opening funeral scene of Glass's opera of the same name. The score uses exoticist tropes to evoke an ancient Egyptian setting.Footnote 55 It features loud, exposed drumming, which was unusual for Glass's style, and, in his own admittance, totally unrelated to ancient Egyptian music. Instead it creates, in Glass's words, “‘our’ Egypt” (quotation marks in original); an imagined version that appeals to Western imaginations.Footnote 56

Robbins's choreography matches the exoticism of the music. “Akhnaten” opens with a solo for single male dancer running in a wide circle around the stage, as Glass's drums pulse in the background. The soloist that Robbins chose for this moment was Soto, a dancer with Navajo and Puerto Rican parents, and his Native American heritage seems to have played a role in his selection.Footnote 57 As Soto described it in our interview, during the rehearsal process, Robbins grabbed his hand and pulled him to the front corner; Soto was worried that he was in trouble and that Robbins was walking him out of the hall. Instead, Robbins had him run around the stage in a wide circle. Afterward, someone mentioned to Soto that it was a powerful moment because of the dancer's heritage and because at the time Soto had, in his words, “pretty long hair.”Footnote 58 Other dancers I spoke to about the ballet also mentioned this solo as a special moment because of Soto.Footnote 59

When the soloist has finished circling the stage, he is joined by two other men, and for another few minutes “Akhnaten” features only male dancers. They pulse in wide lunges, smack their chests, and swing their arms while running, dancing with the inelegant athletic effort that is associated with exotic male characters in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century ballets.Footnote 60 Robbins also attempts to draw from ancient Egyptian art by playing with a two-dimensional type of body positioning (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Unusual reference to Egyptian artistic figures in ballet. Note the head tilt to the side, with the torso facing the audience. NYCB dancers in Glass Pieces, section three. Photographer: Paul Kolnik. Used with permission.

Section three also offers the thematic and musical structure closest to that of modernist ballet. In the beginning, Robbins introduces a few key choreographic gestures—running in an exaggerated bent-over position, jumping forward onto the heel while kicking the back leg up, and holding one hand to the chest with both wrists sharply bent. These are combined and developed over the course of the movement. In other words, this third section features the type of linear thematic development characteristic of Balanchine's and Robbins's earlier work. The choreography in the “Akhnaten” section is also matched to the pulse of the music, though in much less rigid ways than the corps movement of “Façades.” Altogether, the combination of group unity and development gives a sense of group subjectivity: That these are identifiable characters but all as one unit, not as individual people. The effect is very different from the mass disorganization of the corps in the first movement or the assembly line in the second movement. The corps seemed to have appreciated it, particularly the men in the corps, who at NYCB often get much less active dancing than the women.Footnote 61

By using exoticism to free his dancers from modernity, Robbins taps into a phenomenon pinpointed by musicologist Phil Ford in his article “Taboo.” In his research on 1950s exotica, Ford argues that exoticism functioned as a way for people living in a self-consciously modern society to express their longing for an imagined other world. Indeed, by indulging in this longing, exotica listeners were not only able to maintain their sense of a modern self, but also to strengthen it. Moreover, as Ford argues, members of the 1960s counterculture were equally obsessed with this exotic escapism, despite their own self-proclaimed horror of it. In other words, as Ford and others have pointed out, exoticism reinforces, even creates, modernity.Footnote 62 “Akhnaten,” for all its seeming incongruity with the first two sections of Glass Pieces, does the same work as the rest of the ballet. It creates an exotic escape valve from the self-conscious modernism of “Rubric” and “Façades,” and in doing so reinforces the sense of modernity present in the first two sections. It allows the viewer to indulge in the same fantasy as 1950s exotica, and as the Rite of Spring before that, and La Bayadère before that. It is a fantasy of being a person in another world; one who does not need to rush to the subway in order to get to work and perform a grindingly repetitive job. In creating this fantasy, however, “Akhnaten” reinforces the difference between this imagined world and the present. The lights go down on the dancers stretching their arms to the sky in group triumph, and the audience applauds with wild abandon. Then they go back out onto Lincoln Center Plaza and rush to catch their subway train, perhaps just a little more conscious of the modern nature of their lives.

Glass Pieces and the Creation of Contemporary Ballet

Glass Pieces was a turning point for Robbins, the company, and ballet more broadly. It demonstrated that NYCB could move past Balanchine and create a new style that vividly depicted present-day New York. Clive Barnes wrote in his review of the ballet “[Robbins] is a poet of the instant.”Footnote 63 The opening performance was greeted by tremendous applause. Calegari and Cook, too, described the sense of relief they felt at the ballet’s premiere. Cook said that “after the tragedy of losing our captain [Balanchine]” he felt that there was a sense that “this [was] a big success and we [were] safe.”Footnote 64 When the company took Glass Pieces on a European tour later that year, International Herald Tribune critic David Stevens remarked that the entire program was “a kind of manifesto, a promise of continuity and a commitment to renewal.”Footnote 65

This shift in form and style helped set the stage for contemporary ballet. In the following two decades, choreographers at NYCB and elsewhere turned again and again to minimalist and postminimalist music, though Robbins himself used the style only once more, in the markedly less successful 1985 ballet Eight Lines to Steve Reich's 1983 Octet.Footnote 66 Although this trend dropped off slightly in the 2000s, it returned in the 2010s, particularly as NYCB strengthened its ties to the indie classical scene in Brooklyn.Footnote 67 Today, North American and European ballet stages are dominated by minimalist and postminimalist music, from Akram Khan's collaboration with Jocelyn Pook for English National Ballet to Justin Peck's choreographic debut at NYCB to music by Glass.

The genre of contemporary ballet has continued to rely not just on minimalist music but on the interpretation of minimalist music as the sound of modernity. New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff reacted particularly strongly to the premiere of Glass Pieces in 1983, writing in her review that “It is a picture of our systematized times—the electronic age, the computer age. And it is always, through its very formal structure, a metaphor for the human striving to survive this systematization, itself self-willed by humans.”Footnote 68 That sense of systematization is closely related to the interplay between dance, music, and time in Glass Pieces. The grid that surrounds the ballet represents the undifferentiated time within Glass’s music: Relentlessly even in pulse, relentlessly non-developmental in theme. There is something terrifying about the depiction of human civilization as a grid, about the endless undifferentiated squares that are the backdrop to Glass Pieces. They speak to the more disturbing side of postmodern dance, the notion that there is an average human who can be smoothed out like a statistic.

However, Glass Pieces demonstrates not just one impulse from minimalist music but two. One impulse leans toward anonymity: the desubjectified masses of postmodern dance. The other leans toward heroic subjectivity, embodied in the soloists of the first two sections and the corps in the third section. As the dancers move inside the grid, they alternately align themselves with its time structures absolutely—Kisselgoff’s systematization—or move away from it to produce some other sense of subjectivity. By claiming a similarity between all humans, Robbins leans in the same direction as the postmodern choreographers did, asserting that every human is equally ordinary and thus equally deserving of attention. At the same time, by reasserting hierarchy he also leaves space for audiences to feel their own subjectivity in the ballet. Wingert noted that “Façades” could reflect a positive sense of anonymity in New York: “you can walk out on the street and never run into someone you know … [W]e're all part of the same energy and structure and culture and life but we each have our own … protection, that's why we live here so that we can be what we want to be.”Footnote 69

Minimalist music created the space for both the anonymization and the celebration of the individual in contemporary ballet by facilitating two different types of hearing. In one, the listener notices the music as a marker of long sections of time but does not pay close attention to its contents, letting the sound wash over them. In the other, the listener attunes to small changes over time, to emergent melodies, and to the driving pulse. Because of the contrast between these two different positions, the audience can choose to move back and forth between the two, mimicking the experience of moving through a subway station at rush hour, both a cog in a mindless machine and an individual hurrying toward a train.

Anne Searcy is an Assistant Professor of Music History at the University of Washington. Her book, Ballet in the Cold War: A Soviet-American Exchange was published by Oxford University Press in 2020.