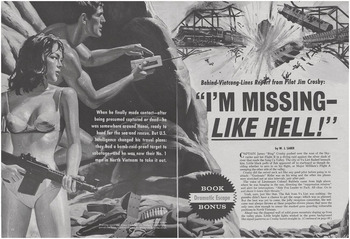

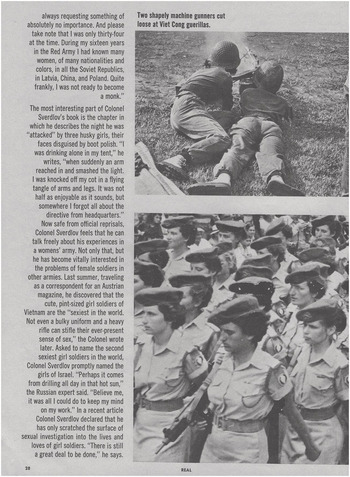

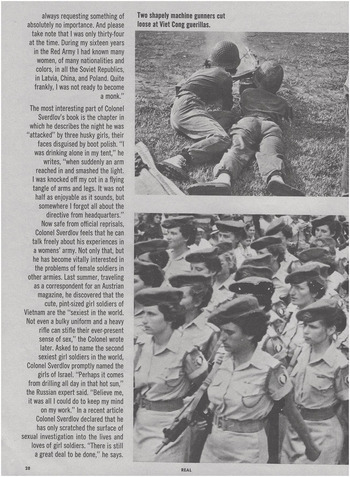

Above drowned mangrove swamps and mud-banked canals, a UH-1B Huey helicopter flies low to the ground, roughly 175 miles northeast of Saigon. An American pilot sits at the controls, the chopper circling around a lone, thatch-roofed hut. Captain Kok Quong, a liaison with the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) Rangers is on board. “It could be a Viet Cong arms or food depot,” he surmises. As the pilot lands to investigate, shadowy figures emerge from the reeds on both sides of the hut. A short, violent firefight ensues but the guerrillas flee, leaving Quong to recommend that his Rangers in an accompanying transport helicopter land, fan out, and make a sweep on foot and in rubber boats. The American aviator is skeptical – the VC never mass together to make large-scale offensives worthwhile. Still, they decide to pursue, and, over the next two days, the Rangers “bag” sixty-five Vietcong, thanks largely to this small US “Huey air force.” As Stag’s Carl Sherman reports, the Americans are a bright spot in a “long, discouraging war with the communists” that has been “dragging along for over eight, frustrating years … without making an appreciable dent in either the number or activities of the Viet Cong guerrillas.” It is January 1964.1

These frustrations continued long after American ground combat troops arrived in South Vietnam the following year. Like their ARVN counterparts, US soldiers and marines also would make assumptions about whether rural farmers were National Liberation Front (NLF) sympathizers or loyal government supporters. Worse, their combat experiences rarely lived up to dreams stoked by Cold War popular culture, where brave cavalry troopers always defeated the savage Indians. In Vietnam, the ambushes never seemed to end and, along the way, a “gook syndrome” became pervasive – to frightened Americans, all Vietnamese were “equally bad.” As their fantasies of heroic combat dissolved, GIs progressively viewed the war as an absurd, morally inverted misadventure. One exasperated soldier asked, “What am I doing here? We don’t take any land. We don’t give it back. We just mutilate bodies. What the fuck are we doing here?” Every year the war dragged on, fundamental questions like these became harder and harder to answer.2

If some young American men felt terrified and disillusioned by their combat experiences, surely among them were those who still hoped to prove their masculinity while in Vietnam. Many turned to local women in hopes of filling the void. Likely, military leaders realized this, one deployed officer noting how his in-processing briefings included subjects “from the current Viet Cong infrastructure to the common venereal diseases in Vietnam.” Another GI, who interviewed some 100 new arrivals in Cam Ranh Bay, found they had little to say about the war’s larger issues, as “the men’s personal concerns were mostly sexual.” As developed in the pulps, women were ripe for the taking in war-torn Asia, especially by the heroic warriors who occupied the country.3

In some veteran narratives, the male protagonist clearly triumphed as both heroic warrior and sexual champion. John “Doc” Bahnsen’s memoir – aptly titled American Warrior – fits this description well. Only fifty pages in, Bahnsen recounts how he left behind “four small kids and a faithful wife” in Georgia, swearing that he would never become involved with a “native woman.” “I broke that vow shortly after arriving in Vietnam,” he recalls. At a local bar, the young captain encounters Thach Thi Hung, the “Dragon Lady of Bien Hoa,” whom he seduces the very first night they meet. She is an “enchanting woman” and Bahnsen finds her “wise” beyond her twenty-five years. He tells Hung that he will not give up his family for another woman, “a fact incongruous with my behavior at the time, but no less the truth.” Bahnsen is quick to point out that Hung does not mind, since she thinks the American is “cute” and she has a “thing for pilots.” To no avail, the American aviator encourages a pregnant Hung to have an abortion, returning to the United States unsure “what she was gaining by having our child without me around to help.” Brave men rarely suffer war’s consequences.4

Yet what happened when Vietnamese women did not throw themselves at American GIs like they did in Bahnsen’s memoir or in men’s adventure magazines? According to popular understanding, all local women were ripe for the picking. One American psychiatrist who spent a year at the University of Saigon believed Vietnamese women had “the softest skin in all the Orient,” while a pulp writer supposed they were “among the most sensual in the world.” If so many US servicemen felt “impotent” from indecisive fighting against an elusive enemy, might they not gain a sense of satisfaction through the sexual conquest of women apparently hard-wired to please? Shrapnel and bullets exposed the weakness of human flesh. Perhaps sexually dominating the “most beautiful flowers” of Vietnam would reinforce one’s masculinity, a shield behind which to deal with war’s frustrations.5

The problem, of course, was that relatively few Vietnamese women acted according to male fantasies. Certainly, female prostitutes contributed to Senator J. William Fulbright’s assessment that Saigon had become “both figuratively and literally an American brothel.” But most Vietnamese were not the erotic seductresses of pulp illusion. Many young readers must have assumed that Asian women were available to them, overlooking the inherent racism within writers’ depictions of Saigon as a “slant-eyed Sodom.”6 American men were exceptional, so they imagined, and thus desirous. Likely, few GIs thought twice about their sexual aggressiveness, their hassling of women on Saigon streets, their demands for female attention, or their foul treatment of bar girls. Even fewer presumably considered how their sexual ultimatums might be an outgrowth of the anxiety and rage they felt from being locked in a stalemated war.7

In their unique way, men’s adventure magazines contributed to a culture which found it acceptable to engage in sexual aggression toward and violence against Vietnamese women. The causal links, of course, were never so neat. Reading macho pulps did not mean GIs inevitably committed rape in Vietnam. But the mags did provide rhetorical space for readers to think along the lines of sexual conquest, to deem all “Oriental” women as opportunities – for sex, for proving one’s manhood, for demonstrating power over the savage other. The pulps were a cultural, if not ideological lens through which American men viewed Southeast Asia, long before they ever deployed there. In adventure magazines, sexual coercion was normal, consent and female subservience assumed. Moreover, wartime apparently suspended any moral questioning over acceptable male behavior. Many GIs perceived both consensual sex and forcible rape as time-honored byproducts of war, either a “just reward” or inevitable “collateral damage.” For nearly two decades, the macho pulps had conveyed long-standing assumptions on these bonds between war and sex. Thus, soldiers arriving in Vietnam disembarked carrying high expectations alongside their olive drab duffle bags.8

When these expectations failed to materialize in an increasingly meaningless war, the resulting disappointments threatened to undermine GIs’ sense of manhood and identity. An inability to exercise control over the enemy had ruptured martial fantasies. On the largely unconventional battlefields of South Vietnam, many soldiers decidedly had not affirmed their masculinity. Far different from adventure mags, military heroism had proven frustratingly elusive. How many working-class soldiers then looked to sexual triumphs as a way to compensate, to regain their sense of superiority? When half of the pulp vision – the noble warrior – collapsed, it is plausible that many GIs turned to the other half – the sexual conqueror of foreign women – as a way to satisfy their psychological needs for control.9

At least soldiers and marines could prevail over the civilian population, or so was the hope. In line with such thinking, Vietnamese women became natural targets, Americans’ fears over losing control fostering sexually violent fantasies that might then be acted upon. The pulps surely encouraged such illusions. If an Asian woman was implicitly erotic, as the magazines reiterated year after year, did not the ability to overcome her sexual prowess, to satisfy her, demonstrate a “real” man’s masculinity? This must have fueled the imaginations of more than a few teenage readers-turned-soldiers. Of course, sexual violence and rape in war hardly center on satisfying the victim. Far from it. More often than not, these aggressive actions were (and are) blatant displays of power over individuals, if not entire societies. Vietnam proved no different, with immensely tragic results. Women were now squarely on the front lines of war.

A Population at War

Even before American combat troops arrived in Southeast Asia, senior leaders in the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) realized that promoting a healthy relationship between the rural population and the Saigon regime would be crucial to defeating the communist insurgency. Success depended on local government being “responsive to and involving the participation of the people.” To MACV, this was the heart of the allied pacification program. Gaining control over the population surely mattered, but only as a stepping-stone toward the people voluntarily contributing to the political process. The Americans could partner in this development, but ultimately the population had to trust that its government was the legitimate entity in South Vietnam and committed to bettering the lives of all South Vietnamese.10

In many Americans’ eyes, however, that population seemed incapable of acting in a trustworthy manner. GIs regularly complained of locals being openly friendly yet secretly disdainful. Portable lie detector tests to evaluate “the loyalty of native troops” proved ineffective. Even women and children could not be trusted. Male noted how US troops would enter a village and question a young boy who insisted he spent all his time taking care of his mother and sisters. “Ten minutes later,” the mag related, “all hell breaks loose, with U.S. unit almost annihilated – and when they go looking for that ‘innocent’ kid they never find him.”11 Army nurse Winnie Smith remembered in her memoir taking care of a wounded Vietnamese girl with a 106 degree temperature. The on-call doctor was hardly sympathetic. “Let her die! She was probably tossing a grenade at our guys when she got shot.” When Smith protested, the surgeon doubled down. “She’s a gook! Bust your ass to save her life, and she’s likely to return the favor by blowing up another one of our guys.” If MACV leaders were hoping to nurture a democratic political process, they confronted major obstacles when so many individual Americans felt they were being “cheated” by the Vietnamese.12

Within this atmosphere of distrust, US and ARVN troops struggled mightily to gain an advantage, not just over enemy combatants, but over the population as well. While Americans castigated rural Vietnamese as being politically unsophisticated, local grievances mattered, thus facilitating the NLF’s attempts in constructing a shadow government that might contest GVN rule. Eliminating political competition, however, inescapably brought terror to villagers’ doorsteps.13 Stag underlined this point with an early-1967 photograph of a US marine surveying a dummy, lashed in a hangman’s noose, swinging from the roof of a deserted hut near Da Nang. The effigy represented “death to South Vietnamese leaders who cooperate with the Americans.” The social implications of such wartime terror were readily apparent. That same year, True ran a set of artist John Groth’s sketches, one of them depicting young boys watching while American GIs dug foxholes. “Solemn-faced Vietnamese children are omnipresent,” the caption read. “Only the very young ones ever smile. The children are old at 10.” Everywhere, it seemed, war-weary civilians might turn against their protectors at any moment, blurring the battlefield lines between democratic aspirations and communist intrigue.14

Undeniably, American soldiers worked hard to help build a stable South Vietnamese state as they sought to destroy their ally’s external and internal enemies. Nation-building and warfighting always were parallel efforts, and men’s magazines made sure to highlight the benevolent, modernizing efforts of these “gentle warriors.” In True, Malcolm Browne spotlighted one Green Beret sergeant who “could be ruthless in battle, but he could also spend a whole month’s pay to help out an impoverished Vietnamese family.” The following issue, Browne made note of a medic, sweat pouring “down the young soldier’s face as he found himself in war trying to save a woman’s life.”15 In other magazine offerings, navy technicians adopted children from Catholic orphanages, medics administered smallpox vaccines to Montagnard mothers, and “Warriors on Bulldozers” constructed vital transportation infrastructure. When US Army Captain Paul L. Miles, a “tanned and whip-thin” Rhodes Scholar from Metter, Georgia, oversaw operations at Cam Ranh Bay, the engineer officer was “working wonders with men who were mostly young, some of them just two months off the farm or away from the corner drugstore.” These citizen-soldier warriors might destroy, but the pulps hoped to show that they could build just as well.16

Yet inherent paradoxes existed within the simultaneous process of building while destroying. The South Vietnamese refugee population spiked in the wake of devastating military operations. Capitalism proved far more exportable than democracy, wreaking havoc on the local economy. If True Action was correct in 1967 that “the war has gone on too long and the people are sick of it,” then how could it ever be possible for Americans to win over the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people?17 Worse, any gains made in the political arena tended to be incommensurate with the damage inflicted by military operations, a destructive yet necessary component of the larger war effort. As frustrations mounted, counterinsurgency scholars of the day warned that the “pressure to meet terror with counterterror will at times seem irresistible, but to do so is to play into the guerrilla’s game… Brutality, fear, and the resultant social disorganization can only work for the guerrillas.” That may have been true, but as Americans increasingly adopted the motto “never trust anybody” as their best chance of survival, a supposedly ambivalent, if not hostile, population came more and more to be seen as an adversary rather than an objective.18

In such a wartime environment, where pulp readers were promised both power and pleasure, where the helping hand became a hand of destruction, it was not difficult for American soldiers to view sex as both an outlet and a weapon. If the people were hostile, might not GIs retaliate against women with threats and acts of sexual violence? As an instrument of war, rape long has been effective in terrorizing and humiliating the local population, an efficient tool to forcibly gain the compliance of civilians. It is hard to support assertions, however, that official US policy called for sexual violence against the Vietnamese population.19 Without doubt, at least some boot camp drill instructors assured recruits they could rape Vietnamese women. Once deployed, many soldiers and marines failed to question orders that led to them violating innocent civilians caught in the crossfire of war. Too often, commanders only lightly punished sexual assaults or looked the other way when their subordinates acted irresponsibly. Yet none of these transgressions resulted from command policy. Rape was not a sanctioned strategy for attaining US political objectives in Vietnam.20

Still, Americans did engage in sexual violence throughout much of the war. Part of this could be explained by “Orientalist” attitudes which depicted Asian women as “creatures of a male power-fantasy.” Surely, the macho pulps made clear that readers’ sexual fantasies were possible. For Men Only ran a photo spread of Maria Minh, “Mademoiselle from Saigon,” who was “one part French, one part Asian and two parts just terrific.” Male also published a story in which the half-French, half-Vietnamese Lilli-minh serves as the female protagonist.21 Yet Orientalism also rested on the belief that these women were not only licentious, but also culturally inferior, perhaps even subhuman. The European blood in Maria and Lilli’s veins no doubt made them more acceptable to ravenous Americans. These beautiful women, however, were still part of a “primitive” society, illiterate peasants cut off from “civilization” whose minds and morals had atrophied beyond saving. For GIs pursuing sexual release in a disheartening war, the Vietnamese “nymph” must have appealed as an alluringly easy target of their desires.22

While countless Americans saw Asian women only as objects, an inability to differentiate the real from the imagined also contributed to wartime sexual violence. In Vietnam, GIs engaged in a variety of sexual encounters – from consensual sex and commercial prostitution to forcible rape. In the process, many often failed to discriminate between “available” and “unavailable” women, frequently misconstruing violence with sex. One marine described a horrific scene in which members of his unit gang-raped a girl, the last man making “love” to her before shooting her in the head. In a similar episode, a soldier noted how the female victim “submitted freely” to rape so she would not be killed.23 These GIs’ descriptions suggest how cultural representations of sex and gender were being reproduced in Vietnam. The September 1966 issue of Stag, for instance, spoke in eerily similar terms. “When a woman cries before sex – especially if she’s new at it – it’s no sign she wants you to stop,” the magazine claimed. “Usually [it] means just the opposite and the tears only mean she’s a little ashamed of her own desire.” If men heard “yes” when women said “no” at home, what chance did a Vietnamese woman have who protested acts of sexual aggression in a time of war?24

Conflating consensual sex with rape might also be seen as the result of American arrogance and disregard leveled toward a population immersed in war. While many US advisors gained a deep admiration for their Vietnamese comrades, innumerable GIs looked down upon local women, their roles as “hooch maids,” bar girls, and prostitutes only reinforcing soldiers’ condescension. Dependency on Americans to make a wartime living left these women with a stark dilemma. The war had forced many of them to engage in unseemly activities to help provide for their families, yet when they did, Americans found them objectionable, if not repulsive.25 Worse, the entire Vietnamese society appeared complicit. One US helicopter crew chief believed that children would “sell their mothers and sisters for a gang rape for enough piasters.” Not all, though, placed blame on the Vietnamese. A sympathetic pulp reader shared with Man’s Magazine how most Americans behaved overseas. “All the women here are easy game and I can buy your girl, wife or sister for a carton of cigarettes. With this GI attitude,” the letter writer argued, “no wonder American soldiers aren’t liked.” Here was the definition of misogyny – desiring someone you despised.26

As in so many Orientalist narratives, women’s voices remained silent. Likely, few Americans considered how Vietnamese families felt as their daughters interacted with outsiders. When Duong Van Mai fell in love with her future husband, Sergeant David Elliott, her father was “distressed by the shame,” declaring that if she married an American, “everyone in Vietnam would take [her] for a whore.”27 For those women in far crueler situations, forced to use their bodies as “bargaining chips” for food or money, the sexual debasement must have been excruciating. One account of the 1968 fighting in Hue details a female refugee offering sex in exchange for a C-ration meal. “There was no shortage of takers.” Similar barters took place in World War II, with both French and German women, suggesting many women in war viewed this trading of sex for food as a matter of life or death. This “entitlement rape” further blurred the lines for how some GIs thought about consensual sex and prostitution. If a woman sold her body to save herself and her family from starvation, how consensual was the sexual exchange?28

Arguably, not many American soldiers in Vietnam ever bothered to consider such troubling questions. For GIs growing up on the macho pulps, wartime sex was about satiating masculine needs, most certainly not an economic necessity for survival. Many Vietnamese women, though, approached sex from a far more dehumanizing perspective. Le Ly Hayslip’s harrowing memoir, for instance, is replete with sexual trauma, detailing how young women she knew made money by selling products like cigarettes and chocolate to American soldiers at basecamps. This eventually led to prostitution because the exchange garnered more money.29 GIs thus participated willingly in the commodification of women’s bodies, viewing prostitution as little more than a time-honored tradition of the Orient. The pulps long had made that notion clear, a trend continuing throughout the war. Given the supposedly inherent eroticism of Asian women, Americans like journalist Peter Arnett almost reflexively imagined that “heads of families did not think twice before routinely selling their daughters if they needed the money.” Of course, Vietnamese women, not American GIs, were suffering most from the burdens and moral injuries of this sexual capitalism.30

These ties between capitalism, consumerism, and sex were prevalent themes in Cold War adventure magazines. The experience of war in South Vietnam only buttressed impressions of seductive Asian women who “had something to gain” from the American presence. When a prostitute offered herself to a GI, did the proposition reinforce stereotypes from the macho pulps? Saigon after Dark author Philip Marnais described the GVN capital in 1967 as “a terribly lonely town for the average GI, and his loneliness is ruthlessly exploited by the city’s pimps and prostitutes.”31 Male ran a short piece the same year, noting one Vietnamese lawyer who was calling for a relegalization of prostitution, which had been outlawed by President Ngo Dinh Diem back in 1955. While the editorial praised how this change might cut down on the “skyrocketing” venereal disease rates in South Vietnam, it also highlighted a Pleiku brothel in which the “girls, all supervised by a matron, are able to take care of 100 to 300 soldiers a day – earning from $60 to $112 per month plus room and board.” Prostitution may have been relatively profitable, but these types of exchange must have been physically and emotionally devastating. Nor could they have contributed to Americans thinking very highly of Vietnamese women more generally.32

Of course, men’s magazines tended to focus on the exploits of US servicemen, not the psychological or physical injuries borne by Vietnamese women who may have lost a piece of themselves in the degrading solicitation of wartime sex. Rather, the pulps viewed prostitution as promoting men’s “rugged individualism,” an opportunity for soldiers to spend a night with “pretty tramps.”33 But what happened when a Vietnamese woman did not willingly give herself to an entitled American GI as the magazines had promised? Did her refusal lead to frustration, to resentment, and, in some cases, even to violence? In the world of men’s adventure, an Asian woman had one function – to sexually gratify the heroic warrior. When she declined to fulfill that purpose, popular notions of American manhood appeared to sanction men taking their allegedly rightful prizes regardless of consent.34

“War Culture”

In late January 1971, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) held a three-day event in Detroit to publicize war crimes and atrocities in Southeast Asia. Dubbed the Winter Soldier Investigation, the forum produced more than 200 allegations of criminal behavior on the part of American GIs. Lance Corporal Thomas Heidtman, formerly of the 1st Marine Division, reported seeing frequent instances of women with their clothes ripped, “just because they were female and they were old enough for somebody to get a laugh at.” One participant argued the war had devolved into an “atrocity-producing situation,” another maintaining that the deliberate and indiscriminate killing of civilians had become “standard operating procedure.” Sergeant Jamie Henry, who had served with the US Army’s 4th Infantry Division, testified watching two men take a young, naked Vietnamese girl out of a “hootch” and assuming “she had been raped, which was pretty SOP.” If men were supposed to demonstrate their heroism in war, to proudly embody American democracy abroad, these Winter Soldiers told a far less ennobling tale.35

Blame for these moral transgressions, to include wartime rape, reached far and wide. Some critics alleged that MACV’s pressure for high body counts to measure the number of enemy dead led to GIs embracing the “mere-gook rule” which deemed Vietnamese lives as cheap. Others blamed stateside drill instructors, whose hypermasculine training methods produced soldiers who wanted to “prove themselves as men by becoming killers.” Still others, like legal scholar Rhonda Copelon, have impugned war itself, which, she argues, tends to “intensify the brutality, repetitiveness, public spectacle and likelihood of rape.”36 Finally, there are those who level charges against the corrupt socializing influences of military culture. Duke University law professor Madeline Morris illustratively maintains that military organizations can foster the “acceptance, transmission, and elaboration of rape-conducive norms” that may lead to wartime sexual violence. Of course, any nation’s armed forces are an extension of the society which they serve, making it difficult to fully disassociate military norms from larger cultural ones. If Vietnam-era soldiers believed war gave them a license to rape, those expectations likely had some cultural underpinnings.37

Men’s adventure magazines occasionally demonstrated that combat, in fact, did hold the potential to erode one’s moral standards, a common refrain of GI memoirists from Vietnam. Back in 1952, with the war in Korea still raging, an article in Men suggested that when a combat soldier lost his senses, he became a “terrible, effective and vindictive killer.” Ten years later, the magazine showcased a World War II marine sergeant, Clark Kaltenbaugh, who undertook an “incredible revenge campaign” after losing buddies during hard fighting on Guadalcanal in 1942. For three years, the leatherneck battled across the Pacific in some of the most bitter operations of the entire war. When shipped home in July 1945, he had killed forty-three enemy soldiers.38

If the marine sergeant had become numb to so much killing, his successors in Vietnam would have understood the moral descent. Philip Caputo recalled members of his company passing “beyond callousness into savagery.” Army lieutenant James McDonough seemed to agree, describing war as “the absence of order; and the absence of order leads very easily to the absence of morality.”39 In both cases, the men under these officers’ command often seethed with revenge, as did Kaltenbaugh a generation before. Fear may have blurred the ethics of combat, but so too did anger. In one 1968 issue of True Action, a Vietcong raiding party overwhelms a South Vietnamese garrison and executes the local mayor and his three sons. The response is obvious, at least to the magazine: “To recover face for the American forces, the Viet Cong raiders must not be allowed to go unpunished.” Such storylines understandably sought to punish the VC aggressor, but they also put Americans, and their South Vietnamese allies, in a cycle of perpetual violence.40

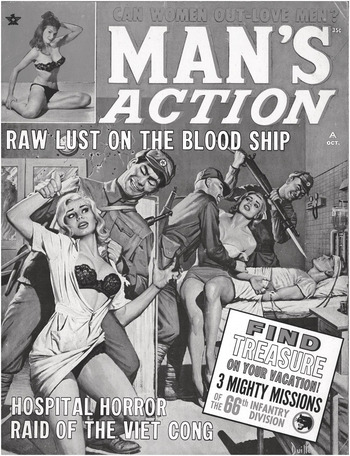

Fig. 5.1 Man’s Action, October 1964

The language of violence used by Vietnam-era soldiers mirrored that in the macho pulps. GIs spoke of having a “sense of power” and a “sense of destruction.” Many admitted they enjoyed the act of killing, one marine clearly working through the psychological wounds of war as he shared his story. “I really loved fucking killing, I couldn’t get enough,” the veteran recalled. “For every one that I killed I felt better. Made some of the hurt went away [sic].” Adventure mags seemed to reinforce the ease with which GIs slipped into a “primitive state of mind.”41 A Korean War vet wrote a personal account for Action, divulging that he had gone “kill-crazy” after Chinese troops had killed his half-brother. In “Blood Feast in the Hürtgen Forest,” Battle Cry published the tale of an American sergeant who “loved to fight” and “lived to kill Krauts,” the NCO’s idea of fun apparently being to grab extra ammunition and go “Kraut-hunting.” When Man’s World ran a 1967 story of a “go-it-alone guerrilla demon” who fought a “no-holds-barred private war that left the occupied Philippines littered with Japanese corpses,” the locale and enemy easily could have been moved to South Vietnam without altering the plotline in any significant way.42

Indeed, the March 1968 massacre at My Lai exemplified the murderous violence inflicted upon a war-weary population. Debate endures over whether the killing of roughly 500 noncombatants was an aberration or emblematic of US military operations in South Vietnam. Still, language similar to what readers might find in the macho pulps resonated throughout testimonies of the horrific episode. One soldier in the infantry company committing the atrocity, while not firing his own weapon, believed his peers had decided the “epitome of courage and manhood was going out and killing a bunch of people.”43 Another veteran spoke of the killings as “scratching an itch,” just something that veterans in Korea and World War II had done only a few decades earlier. That soldiers viewed Quang Ngai province as hostile “Indian Country” only heightened their sense of anxiety. Lieutenant William L. Calley, Jr., the only officer convicted of wrongdoing, recalled his fear that tragic day – “nearly everyone had it. And everyone had to destroy it: My Lai, the source of it.”44

Without question, Calley failed miserably as a leader at My Lai by not enforcing distinctions between combatants and civilians. He participated in the murders as well, compounding moral deficiencies that became apparent only after the story broke publicly in late 1969. Yet the episode may have rung familiar to pulp readers. Like Sergeant Kaltenbaugh’s “revenge campaign,” Calley’s men were seeking payback after their unit sustained casualties in the weeks leading up to the massacre. Audie Murphy, an adventure mag hero himself, said he was “distressed and shocked” over the guilty verdict imposed upon Calley. Evoking “kill-crazy” phraseology, the convicted lieutenant acknowledged not seeing old men, women, and children in Son My village, simply the “enemy.” Once more, the pulps did not initiate this kind of violence. But they did aid in promoting a narrative framework in which the violence against foreign peoples made sense to the perpetrators.45

In pop culture combat stories, the enemy warranted little quarter and even less sympathy. (Such was the outcome of underlying racial and cultural conditioning.) Given the problems of differentiating between friend and foe in Vietnam, no wonder GIs held an indifferent, if not hostile, attitude toward the population. Marine Lieutenant Lewis B. Puller, Jr. remembered being “deeply offended by the notion that the hideous atrocities committed by Calley and his men were commonplace.” But soldier testimonials suggested that the mindsets underpinning the My Lai killings were not so exceptional.46 GIs recalled kicking pregnant women, shooting children, burning “hooches,” and not considering rural farmers even people. Stag noted in early 1967 that GIs were griping when placed in defensive positions protecting the population. “They feel they should be in combat – killing Cong.” Unless leaders stepped in to draw a line, army lieutenant James McDonough declared, men would gradually, but directly, move from stealing sodas to raping young women.47

Puller surely was correct in arguing that the men he led in combat were “like any cross section of American youth, capable of good and evil.” It seems worth considering, though, how GIs who committed evil deeds may have judged them normal given the wartime setting. What made killing or raping civilians immoral at home yet acceptable in Vietnam? If a “war culture” had desensitized men into accepting violence as ordinary, preexisting sociocultural dynamics must also have eased men into thinking along such lines. For decades, the postwar pulps had linked American manhood with power – physical, social, economic, and military power. In Vietnam, when combat failed to deliver ways of realizing that power against an elusive enemy, armed soldiers at least might find meaning by exercising dominance over a frightened population. As one veteran pronounced, “A gun is power. To some people carrying a gun constantly was like having a permanent hard on. It was a pure sexual trip every time you got to pull the trigger.” The best of the pulp writers could not have said it better.48

Of course, none of these American GIs operated in a moral vacuum, and both pulp writers and veteran memoirists made sure to highlight the barbarism of the Vietcong. The October 1964 issue of Man’s Action included a story of an American doctor who joins a Vietnamese medical mission. Two “stunning” female nurses are part of the team, one of whom already has been sexually assaulted by the VC. When the same communists raid the doctor’s hospital, they forcibly strip the women and kill a man before being subdued by our hero. In another 1966 tale from Man’s Life, a South Vietnamese militia soldier comes across the ghastly remains of a local village wife who had been raped by five Vietcong and then bayoneted to death. McDonough’s memoir recounts a similar scene in which his platoon encounters a dead village elder, her breasts “half-severed from her body” because she had taken in children “whose parents had been scattered by the war.” He and his men are left grieving over this “particularly grotesque” act of violence. Critics might have claimed that the VC were far more selective in their use of terror, but such arguments persuaded neither American GIs nor long-suffering South Vietnamese, who grew tired of the Vietcong’s annual demands for more taxes and manpower. In this grinding war of military and political attrition, malevolence could be found in spades on either side.49

In such a guerre sale, winning over an understandably reluctant population was immensely difficult. Village and hamlet leaders often entered into tacit agreements with each side in hopes of riding out the storm. Americans, particularly those engaged in pacification efforts, surely did their best to assist local communities and persuade local residents into supporting the Saigon regime, either through rural construction projects or by medical assistance programs. On occasion, the pulps took notice. Male credited gentle GIs who, “very quietly, have shown themselves to be more generous and compassionate in Viet Nam than any other fighting group in history. When they get food packages from friends and relatives in the States, their first impulse is to distribute this to the Vietnamese needy.” Yet Americans remained wary of civilians caught between two competing political entities, one advisor believing that the VC “shrewdly were getting the better of the bargain” because of the population’s lack of confidence in the GVN. For all the effort put into winning hearts and minds, the impact appeared minimal at best.50

In some measure, the pacification effort simply could not overcome American attitudes that had been reproduced for years in the postwar pulps. The magazines had claimed that real men were superior, in every way. Those presumptions settled into the lexicon of the American war in Vietnam, ultimately helping inspire fear and hatred of the population itself. Colonel David H. Hackworth recalled that men in his battalion not only considered ARVN soldiers thieves and “lazy bastards,” but their contacts with the people came from dealings with the “dregs of Vietnamese society – corrupt soldiers, bar girls, whores, pimps, hustlers, dope peddlers and clip-joint operators.”51 Another infantryman admitted that “the death of any Vietnamese, not just the enemy, was looked upon with no more pity than a hunter gives his prey.” Neither of these commentaries suggested much sympathy with civilians who daily had to prove, sometimes to both sides, they truly were noncombatants. Adventure magazines may not have been a cause of the war culture in Vietnam, but a parallel language certainly was present as Americans interacted with a population many judged as completely inferior.52

If macho pulps inspired a sense of cultural, if not racial, superiority, they also encouraged the fantasy, which had been built up over more than a decade, that sex was a vital part of war. Vietnam seemingly proved no different. Man’s Illustrated reported in early 1966 that there were “damned few complaints from GI’s about bedroom cooperation from the local belles.” The only “gripe,” readers learned, was that “formerly sheltered Vietnamese gals haven’t much imagination. That’s why a couple of enterprising noncoms have imported a half-dozen doxies from Japan – to teach the Viets a few tricks.” One year later, Man’s Magazine erroneously informed their subscribers of the GVN’s efforts in setting up “red light districts,” specifically catering to US servicemen, in major cities like Saigon and Da Nang. These locales, however, paled in comparison to the port city of Alongapo, in the Philippines’ Subic Bay. According to True Action, this favorite spot of the US Navy had 20,000 residents in the town, 17,500 of whom were prostitutes. Surely, pulp readers would be hard pressed to find a small town back home where nearly ninety percent of the population existed only to pleasure American men.53

Veterans imitated this demeanor in their own recollections of the war. One USAID officer spoke of the problems communicating and having a “real” relationship with Vietnamese women. “So you just tried to screw a lot, and you could do that in Saigon very easily.” Lewis Puller wrote home to his wife of the “all-consuming horniness of lonely warriors,” perhaps offering a reason why some female American nurses serving in Vietnam felt like a “commodity” simply because they were women.54 The implications of regarding Vietnamese as little more than whores or thieves could be seen in expressions reminiscent of adventure magazines. Journalist Michael Herr recalled the same, “tired” sexual remark every time an American GI came across a dead woman. “No more boom-boom for that mama-san.” What was it about American culture and its historic attitudes toward women that made men susceptible to this type of thinking?55

Perhaps there is no better illustration of the pulps’ cultural influence than the fact that unit newspapers in Vietnam replicated, almost precisely, adventure magazine formats. These semi-official publications could be found in almost every major command – the 25th Infantry Division’s Tropic Lightning News, the 12th Combat Aviation Group’s Blackjack Flier, and IV Corps’ Delta Dragon. Each week, these broadsheets would highlight the fighting prowess of American GIs and include a cheesecake girl ready for pinning up in any makeshift barracks. An August 1968 issue of Tropic Lightning News read like a full-blown stag magazine. The cover page highlighted a successful recon mission, “Wolfhound Fists Fix Fleeing VC,” that ended up in a face-to-face fist fight with six “panic-stricken” Vietcong. A few pages in, readers could delight in “White Warriors Wipe Out Snipers in Village Cordon,” before gazing upon that week’s “Tropic Lightning Girl.” As the caption under the bikini-clad blonde read, “Her name is unknown to us but then, is it really that important?”56

Far from an anomaly, Tropic Lightning News competed with other pulp-emulating command newspapers. The 6 March 1968 publication of the 1st Cavalry Division’s Cavalier, comparable to other issues, contained all the adventure mags’ long-standing tropes. The cover page trumpeted a recent operation in which one brigade “scored” 2,454 enemy kills, showcased Medal of Honor recipient Lewis Albanese, and ran a story on a military police unit that adopted a local orphan. Inside, the paper lavished praise on a Silver Star awardee, while displaying a photo of a pin-up girl in a short, fishnet miniskirt. Not to be outdone, the Americal Division’s Southern Cross followed suit with stories on the “Brave and Bold” killing nearly 100 NVA troops alongside photos of cheesecake girls in scanty bikinis. A story on “tunnel rat” William Hanks noted how the young specialist had discovered a pin-up photograph of model Chris Noel in an enemy foxhole. Apparently, GIs were “not the only ones who appreciate the American way of life.”57

Perhaps extolling the virtues of American women – similar to The Manchurian Candidate’s bar scene – helps explain why so few of these pin-up girls were Vietnamese. At home, the pulps exposed the secrets of passionate Asian women, apparently ready to please upon command. In Vietnam, however, GIs flipping through their unit newspapers seemingly preferred white American or Australian models. Conceivably, such inclinations implied that GIs found sexual pulp fantasies as fraudulent as combat stories. If Asian women were so desirable, why the focus on cheesecakes back home? An April 1970 edition of the Pacific Stars and Stripes proved a rare exception, its color cover spotlighting Miss Tuyet Huong, posed seductively in a red, white, and blue floral bikini, her eyes dark with heavy mascara. “Song Birds” like Miss Huong might still tantalize as the American war was winding down, but depictions of Vietnamese women surfaced only occasionally in the command weeklies. Like combat, it seemed, the Asian seductress was failing to deliver on the promise of Vietnam being a man-making experience.58

One alternative remained. For years, men’s adventure magazines had reinforced the links between race, gender, and militarized masculinity. Not surprisingly, many Americans in South Vietnam saw themselves as selflessly fighting a war on behalf of a downtrodden people. They were there to help defend against the evils of communism. To some GIs, however, their wartime sacrifices allegedly sanctioned a sense of sexual prerogative, with local women a reward for martial exertion. Male privilege ran through the core of pulp offerings. So too did ideas on battlefield domination and sexual entitlement. We should not be startled, then, when American GIs conflated the two. As one veteran tellingly recalled, “I enjoyed the shooting and the killing. I was literally turned on when I saw a gook get shot.”59

How many of those young men disappointed by the inability to prove their manhood on the field of battle, yet aroused by the incessant killing, shifted their sense of entitlement toward the Vietnamese population? In their quest to dominate someone, anyone, might not an avowedly submissive Asian woman fulfill their needs? In such a scenario, a “friendly” South Vietnamese woman could serve just as capably as a female defender of the NLF. In either case, the environment was rich with potential for sexual domination and violence based on popular notions of race, place, and gender.

Rape as More Than a Weapon

Philadelphia native Timon Hagelin served in a Graves Registration platoon, an army unit charged with processing Americans killed in action. He had no experience with such grim duties, arriving to Vietnam in August 1968 as a shoe repairman. Hagelin quickly made friends with his company mates, “basically nice people,” he recalled. One night while walking on base, the logistics specialist heard cries of help from a Vietnamese woman. As he approached, one of his friends “punched this chick on the side of the head.” Hagelin then watched in disbelief as seven GIs “ripped her off.” The gang rape left him incredulous. “I know the guys,” he remembered, “and I know basically they’re not really bad people, you know. I couldn’t figure out what was going on to make the people like this do it. It was just part of the everyday routine, you know.”60

The notion of wartime rape as routine is a common thread running through Vietnam War memoirs and veteran narratives, suggesting that in war, good people do bad things. Hagelin’s incomprehension of the motives behind the sexual assault he viewed is instructive. Why did “basically nice people” engage in sexual violence? Were they deprived of sexual intimacy on an overseas army base and simply needed physical stimulation? Did they seek to punish the young Vietnamese woman, somehow holding her responsible for their deployment far from home? Or were they seizing upon what popular culture long had promised them, the sexual gratification of an exotic Oriental woman? Perhaps some assailants among the seven men did not even consider why they were raping, merely bowing to pressure so as not be isolated from their peer group.61

Regardless of their individual motives that evening, the rapists had acted out a violent form of aggressive masculinity, one tied directly to power and dominance. By imposing themselves on a young woman, they had weaponized their own bodies. So too did macho adventurers in men’s magazines. Pulp heroes were forceful, uncompromising, and mercilessly virile. They didn’t just engage in sex. They conquered their prey. In the process, the pulps never definitively drew neat lines between consensual sex, prostitution, and outright sexual assault. It is clear, however, that such a sexual continuum in war rested on the exploitation of women’s vulnerability, whether physical or economic. On one end of this spectrum, pulp readers might view wartime rape, prostitution, and sexual harassment. On the other, they could read stories of “duration wives” or ongoing relationships with local women. The thread tying together this spectrum was a view of women caught in war as available and the ideal American man as both strong and aggressive.62

This veneration of aggressive masculinity, central to the glorification of both war and sexual conquest, often could be found in instances of wartime rape, what Susan Griffin called “the perfect combination of sex and violence.” If the war in Vietnam was a contest over power and control, then soldiers might use rape, in some instances, as a way to exhibit dominance over the local population. Simply put, the brutalization of a largely rural society could take forms beyond just napalm strikes or search-and-destroy missions. In cases where rape was not just an “opportunistic perpetration of sexual violence,” to quote Sara Meger, might it instead be an instrument of policy?63

Some critics have suggested that gang rapes were a “horrifyingly common occurrence” during the war, in part, because American soldiers and marines carried out a systematic, deliberate command policy of violence against the Vietnamese population. No evidence exists, however, that MACV’s leadership viewed rape as part of its wartime arsenal, suggesting that the motivations for committing sexual violence were far more complex than the result of overt command influence. Surely some GIs, viewing women as symbols of their local villages, considered the rape of female communists, real or perceived, as a way to prove their masculinity while suppressing communist activity in one fell swoop. But this seems far different than senior commanders calling for sexual violence as a means of targeting the population.64

Complicating any evaluation of incentives is the difficulty in accurately assessing how many rapes actually occurred in Vietnam. Many GIs never reported these crimes – nor did all of the female victims – one lieutenant sharing that if he brought his soldiers up on charges, it would have required unit members to testify against one another and thus “tear the platoon apart.” Some servicemen were more comfortable admitting to killing rather than rape, while higher-level commanders often refused to acknowledge their subordinates’ capacity for sexual violence. Good-hearted, young American boys simply did not engage in such ravenous behavior.65

Just as importantly, the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) system prejudiced the rights of Americans over Vietnamese. As in the pulps, legal procedures were not attuned to protecting local women or even hearing their stories. In one graphic example, military authorities detained a twenty-year-old Vietnamese woman who later claimed she had been raped by ten US soldiers while being held in detention. Investigators questioned the “alleged victim,” who could only tentatively identify two of her assailants. Later, she indicated that “she was not sure,” and the case was summarily closed on account of there being “insufficient evidence to substantiate” her claims. Like the mistrusted native women in the postwar pulps who never had the chance to speak for themselves, the victims’ silence undergirded male narratives of wartime sexual conduct. As a result, GI assailants might view rape as a tolerable, routine act with little fear of legal consequences.66

Deficiencies within the UCMJ system are equally apparent in the low numbers of allegations and convictions reported by the Department of the Army, the only service to keep count of its war crimes cases. According to one source, court-martial convictions involving Vietnamese victims between 1965 and 1973 included only twenty-five instances of rape committed by army soldiers and sixteen by marines. It is impossible to say how accurately these figures represented the true levels of sexual violence in Vietnamese. Yet insights can be gained by the case of a GI who was tried by a general court martial for raping a thirteen-year-old Vietnamese girl while interrogating her as a VC suspect. He was sentenced to a dishonorable discharge and confinement with hard labor for twenty years. Upon appeal, however, his sentence was reduced to just one year. In all, he served only seven months and sixteen days in confinement. Thus, in rape allegations, convictions, and sentencing, the US military legal system clearly privileged the American assailant over the Vietnamese victim.67

The potential for such outcomes to legitimize acts of sexual violence in some men’s minds rose with every dismissed allegation or light punishment. From an organizational perspective, then, military legal proceedings inadvertently helped make this type of violence acceptable, or at very least understandable, to GIs who fell under UCMJ authority. Still, this ethos did not simply appear out of thin air. The legal system’s treatment of violence against women must have had encouragement from some cultural inputs back home. To blame the “pressure cooker” of combat as the sole reason for incidents of rape, a way for men to satiate their sexual desires in a stressful wartime environment, arguably misses the ways in which perpetrators understood themselves and their actions. Gender norms were imparted to male servicemembers long before they joined the armed forces. It seems vital, therefore, to examine how culturally produced representations of sex and violence helped shape GI behavior among the Vietnamese population.68

For working-class warriors serving in South Vietnam, the pulps embodied the macho outlook of these cultural representations. The pulps were among the most widely read cultural products of the Cold War era, and the powerful ideas about American manhood which they expressed surely resonated with GIs. In terms of sexual violence, their influence actually may have increased during the war because of fewer restraints on soldiers’ fantasies and behavior, the easy access to weapons, and an active participation in violence more generally.69

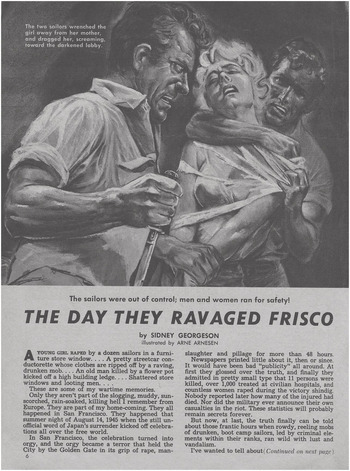

Indeed, within men’s magazines, rape seemed part of the adventure. In April 1959, Sensation quoted novelist George Moore’s 1888 Confessions of a Young Man, which claimed that “Nature intended woman for the warrior’s relaxation.” That same year, Valor included a story of the Wild West in which “Handsome Hank’s special talents were for raping banks of their money and robbing women of their virtue. Sometimes,” the pulp declared, “he combined the two sports.” Of note, the outlaw preferred married women because there was an “added thrill of danger.” Big Adventure’s first story in its June 1961 issue began with a young female being raped by a dozen sailors in a San Francisco store window. The accompanying illustration by Arne Arnesen is frightening, a grimacing woman in the clutches of two men, one of them wielding a knife, as they tear her clothes and drag her away from her mother.70

Fig. 5.2 Battle Cry, July 1959

In “The Strange Case of the Stagecoach Rapist,” Sir! magazine noted in the story’s tagline that Sam Carlisle had “terrorized half the women of the Old West – while the other half waited hopefully to be waylaid and seduced by the handsome, well-educated and debonair outlaw.” If the pulps were correct, might not Vietnamese women also secretly be hoping that American soldiers would seduce them as well? Finally, in an offering from Man’s Action on a “deadly rape gang sadist,” a group of rapists who terrorize women get away with it “because the poor women were too scared or ashamed to go to the police.” Here, life imitated art as victims of sexual assault in Vietnam frequently did not come forward for fear of shaming their family. If Mai Elliott’s father was disappointed she had entered into a consensual relationship with an American, how would other family patriarchs react, daughters feared, if they had been forcibly taken by a foreign soldier?71

At least one pulp mag took on the matter of GI rapists directly. In October 1956, True War asked the question if military uniforms really did make “sex fiends out of innocent boys.” Was military service a “brutalizing influence” that made men “wantonly attack women and girls”? Writer Kenneth Towne offered a laundry list of GI sexual deviancy, from assault to rape and murder, before concluding that the “American serviceman is far from being either a rapist or a sex degenerate.” Towne noted that military sex crime rates were far lower than civilian ones and suggested that the media was to blame for highlighting the “GI Slayer” angle because “it sold a lot of papers.” Worse, the story concluded, the problem intensified overseas as women falsely accused servicemen of rape or sexual assault so they could “obtain money or force their GI boy friends to marry them and thus obtain a U.S.-style meal ticket.” Rape might be inevitable – “boys will be boys,” Towne noted – but the uniform was not to blame.72

While the True War story problematically impugned media outlets and foreign women, Towne stood on firmer ground when arguing that military culture alone did not lead to men becoming rapists. Larger cultural influences were at play. Without question, military socialization processes bred a sense of hypermasculinity among some servicemen, a contempt for women that was part of a long tradition within the armed forces. Yet contemporary understandings of sexual violence, replicated in the macho pulps, suggested a much deeper misinterpretation, well outside military channels, of what rape actually meant.73

In line with Cold War ideas on sexual relationships, men’s magazines intimated a cavalier attitude when it came to nonconsensual sex. One reader from Albany wrote to Bluebook arguing that “a woman can’t be raped unless she’s drugged, tied down or threatened with bodily harm.” A pulp writer for Men was incredulous that a wife in California attempted to charge her husband with rape. Worse, he claimed, “statutory rape” could be a “dangerous trap” if an underage woman, though a “quivering bundle of eager acquiescence,” proved to be a single day short of the legal age of consent.74 The same magazine ran a story which reasoned that “rape is by definition impossible when a girl is more than willing.” As in so many articles, men might be excused for their reactions, given that they were preyed upon by passionate female thrill seekers. One 1969 story in Man’s Life claimed that women who openly solicited a man occasionally made “themselves available for rape!” Women like this had goaded men into attacking them.75

Transported to Vietnam, these sexist mindsets flourished in locales where unofficial base brothels suggested that military leaders were sanctioning, if not institutionalizing, wartime prostitution. Long-standing civilian and military attitudes melded together in Vietnamese brothels. One letter writer to Male, likely speaking for many men in the mid 1960s, claimed that “a certain percentage of women are born prostitutes and nothing in this world will ever change them.”76 Other popular assumptions maintained that war hypersexualized men, which might lead to rape, and thus the need for prostitutes so warriors could “let off some steam.” Sex, it appeared, was the perfect distraction from combat. Even military tradition factored in, one World War II veteran remembering that some sixty percent of the men in his company had relations with “professional prostitutes or pick-up girls.” Nowhere did sex advocates consider how an industry built upon gratifying American lust might affect South Vietnamese social values.77

Nor did such discussions contemplate the degradation to the local Vietnamese women who were performing “basic services” in support of local economies outside US military bases. One account maintained there were 400,000 prostitutes at the height of American occupation, nearly one for every GI. While dubious, the claim rested on an incontestable truth. Sex sold. As one Saigon official candidly explained, “The Americans need girls; we need dollars. Why should we refrain from the exchange?” This commodification of women’s bodies had roots in earlier wars, Male noting in Korea the “growing practice of occupation troops ‘buying’ their own girls.” In war zones across Asia, it appeared, US servicemen were exercising a level of control over local women unheard of back home.78

Given contemporary narratives of the duplicitous seductress, pulp readers likely were not surprised to find that these Asian prostitutes failed to have much loyalty to their American customers. According to Man’s Conquest, intelligence reports were unnecessary for tracking the enemy’s progress in South Vietnam. “Whenever the Viet Cong is on the offensive, the price of paid sex in Saigon temples of pleasure drops 50%. Even the free stuff is easier to get when times get tough at the front.”79 No wonder that veterans spoke of Vietnamese women in demeaning terms. One Special Forces officer wrote of judging a “pubic hair contest” to find out who among two “Eurasian girls,” both “strikingly beautiful,” had more French blood in them. Another vet recalled “playing around with Vietnamese girls who just wanted our money” and shaking their heads until lice fell out. As in earlier stories, the female voices were inaudible, though it is not hard to imagine these women feeling humiliated by their interactions with American GIs.80

While it is doubtful that many young men arrived in Vietnam premeditating acts of rape, they nonetheless were primed to envisage how their fantasies of sex with an “Oriental” woman might play out in real life. Erotic pulp stories certainly enticed. In adventure mags, Americans had sex with “wild and wacky” Korean women, met the “fabulous bare-breasted beauties of Bali,” and found that in most of Polynesia, girls were “essentially willing.” Man’s Magazine printed a 1966 story of a virgin soldier lured in by “Juicy Lucy” and her “seductive slant eyes,” the “pussy cat” ultimately working on the frightened lad with “loving devotion and skill.”81 From tales like these, young pulp readers heading to Vietnam had been conditioned to fantasize about the exotic Orient for years. But what happened when these dreams never materialized? Did servicemen see a lack of options for paid or consensual sex as a rationale for forcibly committing rape? Not all areas where US soldiers operated in South Vietnam offered the chance to barter with prostitutes or meet with women untouched by war’s devastation, yet many of those GIs expected to be sexually gratified regardless.82

Of course, consensual sex and rape were far from equivalent acts. Linking them together, however, was GIs’ widely held view of the Vietnamese female body as available. In this way, gender and Orientalism combined, in potentially dangerous ways, so that local women were seen as lesser, sexually loose, and thus “rapeable” by the masculine American warrior. When Stag mentioned that Montagnard tribesmen of Vietnam’s central highlands had become “blood brothers” with US soldiers and given them “free rein with the available women of the village,” what message did that send to pulp readers?83 Not surprisingly, GIs spoke in analogous terms. They took time off to engage in “intercourse and intoxication” and “balled chicks” because they were “forcibly willing – they’d rather do that than get shot.” An army investigation found that a helicopter crew in Vinh Long province had landed, shoved a Vietnamese woman onto the bird, and forcibly removed her clothes. While she denied having been sexually assaulted – raising questions about how the investigation proceeded – the fact that Americans could swoop in from the sky and seize female prey offers painful insights into the power differentials between US servicemen and Vietnamese women.84

A process of dehumanization coincided with such actions, perhaps helping explain them. Veteran memoirs are replete with language portraying Vietnamese as subhuman “gooks.” As one vet testified, “When you shot someone, you didn’t think you were shooting at a human.” Another explained that “no one sees the Vietnamese as people. They’re not people. Therefore it doesn’t matter what you do to them.”85 What some soldiers did could be horrific. Tales abound of GIs ripping off women’s clothes and stabbing them in the breasts or thrusting rifles and entrenching tools into their vaginas. One private recalled watching a fellow soldier interrogate a suspected VC woman after a comrade had been killed in an ambush. The burly American stood over his naked victim, her legs held apart, screaming at her. “Cunt! Whore! You gonna die, oh, you gonna die bad, Mama-san!” Murdered in gruesome fashion, the woman’s screams offer the only hint that she actually might be a human being capable of feeling pain.86

Brutalizing the Vietnamese made national headlines when the My Lai story broke in 1969, but military legal documents confirm that the sexual violence committed by Calley’s men was not an isolated act. Army investigators found that approximately twenty women were raped at My Lai, some girls as young as thirteen. As Calley himself recalled, “I guess lots of girls would rather be raped than be killed anytime. So why was I being saintly about it.”87 In other rape cases, though, similar attitudes emerged, not just from perpetrators but from investigators as well. When two women forcibly were taken from their village by US marines and raped, they remembered three Americans watching the assault from only ten meters away. Not unusually, the Vietnamese had difficulty positively identifying their assailants. Worse, the examining physician at the local US hospital claimed that both women had previously had sexual intercourse and he therefore discounted their stories since they were not virgins before the assault. Investigators summarily closed the case file. In such a hostile environment, women had little chance of defending themselves, physically or otherwise, from American GIs intent on doing them harm.88

While these acts were neither officially orchestrated nor a centerpiece of MACV strategy, they still created disorder within South Vietnamese society. In this narrow sense, some GIs likely considered rape a standard part of war. The postwar pulps certainly included stories where soldiers had incorporated sexual violence into their battle plans. An autobiographical account in Real War featured a US Army nurse who had been captured and raped by the Japanese during World War II. (Only five pages later, readers could delight in a photo spread of a cheesecake girl in various stages of undress.) By the midpoint of the American war in Vietnam, adventure mags often ran stories of the Vietcong raping and killing innocent South Vietnamese women, quietly avoiding reports of hometown GIs acting in similarly brutish fashion. The message, though, seemed clear – sexual violence was an inherent part of war.89

Moreover, since the pulps argued that US military leaders kept “our boys woman-hungry,” readers likely would have expected frustrated GIs also to consider rape as an act of revenge. Could taking a Vietnamese woman by force avenge those American nurses despoiled by Asian men in World War II? Or, more tangibly, the life of a comrade recently killed in battle? When local villagers kept silent after US troops sustained casualties, for fear of retribution, how many American soldiers assumed that vengeance was theirs to take?90 With ambushes the hallmark of this war without front lines, raping a woman might be a chance to exact payback, but also a way to regain a sense of power in an unsettling war. In the process, rape could be viewed as an attack not just on a female body, but on the Vietnamese “body politic” as a whole. When William Calley claimed that “inside of VC women, I guess there were a thousand little VC,” he expressed widespread anxieties that all Vietnamese women, regardless of their support for communism, were both the enemy and vessels of a toxic ideology.91

Still, not all wartime rapes were linked to the larger ideological struggle. In some cases, young men, feasibly terrified by the act of rape, nonetheless performed out of peer pressure. Within a cohesive group setting, squad mates might be more willing to carry out adolescent aggressiveness toward women. Or, fearing being labeled a homosexual, they could bond with their comrades in a presumably masculine endeavor. Sexual violence, in this manner, became a rite of initiation. As one officer in Vietnam shared with a journalist, “Add a little mob pressure, and those nice kids who accompanie[d] us today would rape like champions.”92 Daniel Lang’s 1969 Casualties of War centers on such an incident. In late 1966, a US infantry squad on a recon mission abducted a young Vietnamese woman, Phan Thi Mao, and four soldiers raped her in turn before killing her the next day. When one GI, “Eriksson,” objects, he is derided as “queer” and “chicken” by his peers. Additionally, after Mao’s rape and murder, a squad mate tells him to “relax about that Vietnamese girl… The kind of thing that happened to her – what else can you expect in a combat zone?” With the perpetrators ultimately being tried under court martial, the gang rape suggests they are not heroic warriors but brutal boys capable of abhorrent acts.93

The act of rape, however, cut both ways. A young GI could exhibit sexual power over a Vietnamese woman, but he also might betray his inability to measure up to the men depicted in adventure magazines. Power differentials clearly were at play. Rape tangibly demonstrated that a woman had been vanquished by a superior power. In Vietnam, however, fear and insecurity impelled many GIs to lash out against the Vietnamese population. Of course, they often did so with a sense of immunity, as gang rapes suggested that neither culprit nor witness had much to fear.94 Still, men worried they might flunk their supposed test of manhood. One specialist in the 4th Infantry Division expressed his anxieties that he couldn’t “get it up to do it” with a prostitute “because you’re not even excited.” His reasons covered a wide gamut: she was young, not “really attractive,” and did not speak English. He also feared contracting venereal disease. When Male claimed in 1967 that GIs attracted to Vietnamese women tended to be “sexually hung-up and frightened,” did soldiers either purchasing sex or raping women question their own sense of masculinity or the possibility they might be “embittered at certain aspects of American life”?95

The 4th Infantry Division soldier’s fear of sexually transmitted diseases also alluded to the disquiet Vietnamese women provoked despite their sexual subordination. For years, the macho pulps had told readers that Asian women were both desirable and dangerous. Japanese doctors had experimented with “the use of diseased native women to incapacitate American troops.” In Korea, female camp followers carried “guns and grenades for Gook guerrillas” in the hills.96 By the 1960s, it seemed young soldiers had much to fear. For Men Only claimed in late 1966 that the Vietcong were “planning autumn terror attacks on beaches where GIs sunbathe, using lithe Frog Girls who’ll swim in with promises of fun, but carry explosive packs in their bikini tops.” The following year, Man’s World alleged that a “top VC jungle fighter” was, in fact, “a former Saigon brothel girl who fights with two tommy guns and carries grenades in her bra.” Female bodies could be toxic vehicles of STDs, but communist women’s sexuality also afforded them the chance to deploy weapons into the very core of the American war effort.97

These pulp narratives reappeared in veterans’ memoirs and even military legal documents. Vet John Ketwig recalled how the more seasoned GIs would warn “new arrivals against falling asleep after sex, for fear of castration.” In imagery evoking the myth of vagina dentata, rumors thrived of Vietnamese women hiding razors in their “sex organs” and castrating their male victims. One official army investigation interrogated an American platoon that had captured a Vietcong nurse and decided to rape her. The lieutenant, “in deference to his rank,” was afforded the first opportunity but “sustained injuries caused by a razor blade concealed in [her] vagina… Immediately thereafter, members of the platoon shot and killed the Viet Cong nurse.” While investigators could not substantiate the allegations, stories like these proliferated. As one marine who found such razor blade stories plausible recalled, “Vietnamese women were made into objects of fear and dread, and it was easy to feel angry at them.” To GIs like this, regardless of the “physical logistics” required by blade-carrying femmes fatales, evil women were out to castrate any American who let his guard down. 98

Given women’s castrating potential – did this not inspire fear at home, as well? – some GI rapists arbitrarily dismissed their victims as prostitutes who, because of their sex work, merited few, if any, protections. Deemed a “VC whore,” any casualty of rape could be judged by wrongdoers as deserving of their fate. Unquestionably, Vietnamese women, often because of the disruptions of war, were available as prostitutes or entered into the GI world as bar girls or entertainers. For alienated American men, however, these distinctions mattered little. Even Lieutenant Calley reported that a man in his platoon assaulted a prostitute after she refused to have sex with every member of the unit, twice, for what he initially paid her. The pulps may not have inspired this type of viciousness, but both in magazine fantasies and in the reality of Vietnam, the lines between sex and violence had blurred beyond recognition.99

For those soldiers with ambitions of power, fueled by the larger pulp fantasy, the heroic warrior became ever more indistinguishable from the sexual conqueror. Likely, many soldiers took full advantage when presented with opportunities to be seen as either, their language clearly reflective of Cold War macho mags. One helicopter pilot shared with journalist Michael Herr the exhilaration of flying above enemy bunkers, “like wasps outside a nest.” “That’s sex,” the captain said, “That’s pure sex.” For those infantrymen on the ground, though, who might not achieve such delight in heroically combatting their North Vietnamese or southern insurgent enemies, the chance to perform as sexual conquistador may have seemed within much closer reach. Such aspirations, in fact, may have been more likely than being the true action hero as depicted in the magazines. In a war fought among the population, Vietnamese women were far easier targets than battle-hardened NVA or VC troops.100

Yet not all sexual assaults occurred on the front lines or even just against Vietnamese women. Support troops ventured into brothels and committed rape just as did infantrymen, one “REMF” titling an entire chapter in his memoir “Fornication.” American women equally could find themselves targets. Nurse Linda McClenahan recalled that her compound’s high fences, lined with barbwire, and security guards were “not for protection from the VC, but to keep us separate from the gentlemen in the late hours of the evening.”101 In Nam, Mark Baker related the story of a GI who encounters an American Red Cross Donut Dollie on one of the massive US military bases. When she offers the soldier a cookie, he crudely replies “Fuck the cookie. I want your pussy.” Frustrated – “You couldn’t get them,” the GI grumbles of the female volunteer – he soon after ventures into his platoon sergeant’s “hooch,” where he is unable to recognize his own reflection in the mirror. “I was looking at a stranger. I’d changed. I’d never seen myself before.” Perhaps the war had transformed him, yet the misogynistic language of this vulgar episode had far deeper roots within pop culture renderings from the Cold War era.102

If both American and Vietnamese women felt defenseless against GIs’ sexual aggression, so too did the Saigon government, which wrestled with its inability to protect the population. Any expansion in prostitution did little to curb the rapes of women, indicating that sexual violence was not simply about sexual gratification. Once more, though, powerful differentials came into sharp relief. While GVN leaders seemed incapable of safeguarding their people, this humiliation extended to men serving in the South Vietnamese armed forces as well. ARVN soldiers long had suffered the brunt of American contempt. The sexual exploitation of Vietnamese women only reinforced GI disdain, one veteran dismissing many of his supposed allies as “fucking queers.” Stag also weighed in, noting how local men were complaining that US troops had “caused the prices paid to prostitutes to go into orbit. A native doesn’t stand a chance when a fat-cat G.I. comes to town.” Such views exposed a harsh yet contradictory reality. Americans were physically abusing Vietnamese women, but when local men could not protect them, those same men were judged deficient by the very perpetrators exploiting women in the first place.103

This mistreatment at the hands of American GIs left countless Vietnamese resentful. They blamed foreign troops not only for inciting sexual violence but also for distorting sexual politics inside South Vietnam. Both unwelcomed imports held the potential to tear apart the social fabric of a largely traditional, patriarchal society. Of course, hard fighting in a stalemated war did not help matters. For at least some Vietnamese men, feelings of masculine inadequacy, outside the gaze of Americans, must have been generated by these political and military upheavals. It seems few US servicemen considered the long-term consequences of these local sentiments. Rather, pulp stories on “duration wives” or the “wild rise in VD rates and a lot of ‘red-headed’ babies being born out of wedlock” left the impression that virile American fighting men had easy access to Asian sex whenever they desired it.104

If Saigon had been turned into a “large whorehouse,” as some GIs believed, then the wartime American presence had done more than just threaten the moral society of South Vietnam. The US occupation also left behind deep psychological scars. As the final American troops withdrew from a still ongoing war, President Nguyen Van Thieu sullenly told his advisors that Nixon no longer wanted an “ugly” and “old mistress hanging around.” This gendered language clearly demonstrated Thieu’s resignation with the subordinate relationship he maintained vis-à-vis the United States. Yet it also alluded to a far deeper sentiment. A feminine, emasculated state no longer served its purpose for a dominant, more masculine nation.105

While the term “mistress” tellingly has no male equivalent, it suggested that Americans had simply used South Vietnam for sexual gratification, a way to help fulfill the fantasy of war as a man-making experience. Yet the reality of Vietnam indicated that sex purchased or seized did not transform boys into men. Nor did the logic of macho fantasy play out in real life. As Viet Thanh Nguyen astutely asks, “If war makes you a man, does rape make you a woman?” In Vietnam, neither proved the case. Like the war itself, rather than inspire tales of heroism and valor, prostitution and rape instead degraded and corrupted. In its final iteration, the pulp fantasy had failed to deliver.106

The Long-Haired Warriors Fight Back

Bui Thi Me was born in the southern province of Vinh Long in 1921. She married at nineteen and joined the revolutionary movement in 1955, soon after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. While taking part in the revolution for Vietnamese unification and independence, she birthed four sons, each enlisting as “patriotic soldiers” in 1967. Three were killed during the American war, the fourth seriously wounded. In 1995, Ms. Bui received the title of “Vietnamese Heroic Mother,” an honor signifying that women were not simply passive victims in war or damsels in distress as seen in so many men’s adventure magazine stories. Rather, women warriors had an extensive history in Vietnam, dating back to the very beginning of the country’s history. By the middle of the twentieth century, they had become an integral part of a revolution aiming for Vietnamese independence, active agents in a struggle for liberation from past injustices.107