Tiwanaku, located in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin, was the seat of one of the earliest states in the Andes (Figure 1). To understand the emergence of this high-altitude polity in the sixth century AD, it is crucial to engage with the preceding Late Formative period, which until recently has been a virtual cipher in the culture history of the region. There have been significant advances over the last 30 years (Hastorf Reference Hastorf, Silverman and Isbell2008; Janusek Reference Janusek and Yoffee2015a), but chronology remains a problem. The Late Formative is clearly a temporal and material “unit of cultural similarity” (Rowe Reference Rowe1962:40), but there is little agreement on its timing. What was the tempo of social and political change leading up to urbanization at Tiwanaku? How many generations of people experienced these changes (Roddick and Hastorf Reference Roddick and Hastorf2010:161)? It is currently difficult to answer these questions because of our wooden chronological scaffolding. Current chronological charts, or chronographics, suffer from weaknesses inherent in block-style period schemes (Roddick Reference Roddick, Swenson and Roddick2018). They are based on small collections of decorated pottery that tend to homogenize change over long periods and large regions (Kubler Reference Kubler1970). They privilege a “bird's-eye” perspective and evolutionary expectations, rather than explicitly engaging practices that produced decorated styles and localized depositional sequences (Burkholder Reference Burkholder1997:8–9; Roddick et al. Reference Roddick, Bruno and Hastorf2014).

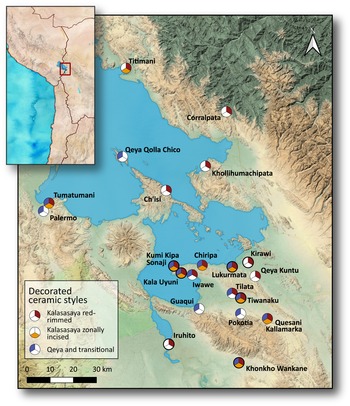

Figure 1. Map of sites with Late Formative decorated ceramic styles from excavated contexts (there are many other sites with decorated ceramics from surface collections). Symbols with a thick border indicate sites modeled in this article. Inset map is a Stamen watercolor map (http://maps.stamen.com). The base map was generated with void-filled SRTM data from the U.S. Geological Survey accessed in Google Earth Engine. The dark green to brown color ramp indicates elevation. The Lake Titicaca outline is modified from a shapefile from Peru's Ministerio del Ambiente (http://www.geogpsperu.com/). In two cases, a single symbol represents two adjacent sites: (1) Kumi Kipa and Sonaji and (2) Quesani and Kallamarka. Quesani has both Kalasasaya styles but no Qeya ceramics; the other three sites have all three decorated styles. (Color online)

There are currently three incompatible chronographics for the Late Formative period (Figure 2; see Korpisaari Reference Korpisaari2015). This period is still “the most problematic” (Bandy Reference Bandy2001:174) in the entire ceramic sequence, and for some, a “typological nightmare” (Plourde and Stanish Reference Plourde, Stanish, Isbell and Silverman2006:246). One source of confusion is that chronologies are based exclusively on decorated sherds, which are relatively rare. Excavated contexts typically have 5% decorated sherds, but some have none at all. Until recently there were only a handful of reliable Late Formative dates from two poorly documented excavations at Tiwanaku (Kidder Reference Kidder1956; Ponce Sanginés Reference Ponce Sanginés1993; see reassessment in Marsh Reference Marsh2012a). There are also taphonomic complications, because later occupations often disturbed Late Formative contexts (Roddick et al. Reference Roddick, Bruno and Hastorf2014). The best-known examples of Late Formative decorated styles are museum pieces of hazy provenience (Roddick and Janusek Reference Roddick and Janusek2018). Finally, Late Formative ceramic production and consumption were local affairs, resulting in considerable intersite variation (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003; Lémuz Aguirre Reference Lémuz Aguirre2001; Pérez Arias Reference Pérez Arias2013).

Figure 2. Late Formative chronographics proposed by Janusek (Reference Janusek and Kolata2003), Isbell and Knobloch (Reference Isbell, Knobloch and Young-Sánchez2009), and Knobloch (Reference Knobloch, Vranich and Stanish2013). Thicker lines indicate clearer divisions; grayscale gradients indicate divisions defined as a temporal range; dotted lines indicate vaguely defined divisions.

In this article, we draw on detailed excavations to develop a series of Bayesian models, a method that has been fruitfully applied throughout the Andes (e.g., Koons and Alex Reference Koons and Alex2014; Korpisaari et al. Reference Korpisaari, Oinonen and Chacama2014; Marsh et al. Reference Marsh, Kidd, Ogburn and Durán2017; Owen Reference Owen2005; Rick et al. Reference Rick, Christian Mesia, Silvia Kembel, Sayre and Wolf2009). After describing Late Formative decorated styles, we detail Bayesian models based on stratigraphic sequences of eight sites. We estimate the temporal limits of each decorated style with uniform phase models, which are the basis for an updated regional ceramic chronology. These limits estimate temporal “inflection points”—brief moments of change or “stoppages” when relationships between people and decorated vessels were significantly reworked and physically remade (Gosden Reference Gosden, Tilley, Keane, Kuechler, Rowlands and Spyer2006:430). As we show later in this article, our analysis reveals a centuries-long span in the early Late Formative with no deposition of decorated sherds, a possibility to which traditional approaches can be blind. Our approach eschews artificially homogeneous temporal blocks and highlights the need to use multiple material classes to build regional chronologies.

Late Formative Decorated Pottery

Archaeologists working in the Lake Titicaca Basin have constructed chronologies with several decorated ceramic types found across the southern part of the basin (Figure 1).Footnote 1 They define the Late Formative 1 phase (previously called Tiwanaku I) primarily by the presence of Kalasasaya red-rimmed vessels (Figure 3a–c), the most ubiquitous Late Formative decorated ceramic style. These small jars, ollas, vasijas, shallow bowls, and pedestal bowls— sometimes with handles—are decorated with red-slipped rims. The “classic” variants are thin-walled, well-fired vessels with fine pastes and burnished surfaces (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:41–42; Ponce Sanginés Reference Ponce Sanginés1993:56–57). Less-standardized local variants have the same form, decoration, and function, but they have thicker walls, coarser pastes, less regular decoration, and were fired at lower temperatures (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:74; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:43; Marsh Reference Marsh2016:15; Roddick Reference Roddick2009:257).

Figure 3. Kalasasaya (a–c) red-rimmed and (d–f) zonally incised ceramics from Tiwanaku, excavated in pit E-17 of the sub-Kalasasaya (Ponce Sanginés Reference Ponce Sanginés1993). Currently they are housed at the Museo Regional Arqueológico de Tiwanaku. (Photos by Andrew Roddick.) (Color online)

Kalasasaya zonally incised vessels (Figure 3d–f) are made with similar pastes and techniques as red-rimmed vessels but are more elaborately decorated (Roddick Reference Roddick2009:236). Ponce Sanginés (Reference Ponce Sanginés1993) defined this style based on a large cache of complete vessels from the deepest levels of Tiwanaku's Kalasasaya temple, the style's namesake. These vessels tend to have soft brown pastes, and some sherds have micaceous pastes. Exteriors are highly burnished with incisions delimiting zones painted in red, black, yellow, and white. The most common design is the triple-step motif, perhaps representing a mountain, but there are a variety of other designs (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:43). This style is extremely rare: in a surface survey of the Taraco Peninsula, Bandy (Reference Bandy2001:166) identified 12 zonally incised sherds in a sample of nearly 100,000.

Another Late Formative style is Thin Redware, defined by a few bowls at Lukurmata (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:65, 88, 269). Possibly similar bowls have been found at Tiwanaku (Bennett Reference Bennett1934:396–397; Marsh Reference Marsh2012b:388, 397), TMV-79 (Mathews Reference Mathews1992:71), and Khonkho Wankane (Marsh Reference Marsh2012b:284). For now, there are too few examples to define this style or its regional chronology; it may be specific to Lukurmata.

The Late Formative 2 style (previously called Tiwanaku III) is defined by the presence of Qeya vessels (Figure 4a–f). Wallace (Reference Wallace1957) described this quite heterogeneous style using a collection from the type site Qeya Qolla Chico on the Island of the Sun, the only site with a significant number of complete vessels (Bandelier Reference Bandelier1910:168–175; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:38–39; Seddon Reference Seddon1998:217–218). Qeya vessels include flaring-rim bowls (escudillas), drinking cups (reminiscent of later keros), and scalloped annular bowls (incensarios), sometimes with modeled feline heads. Pastes can be soft and light brown or micaceous. Decoration is black-on-red with a variety of geometric, zoomorphic, and anthropomorphic motifs, including the staff god. One subtype includes incised vessels (Bennett Reference Bennett1934:Figure 13; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:Figure 3.23). The Qeya style is known almost entirely from museum pieces in Tiwanaku, La Paz, Berlin, New York, and Paris. Although their provenience is unclear (Oakland Rodman Reference Oakland Rodman1994), most are likely from burial contexts. This diverse style is concentrated in the southwestern Lake Titicaca Basin (Figure 1; Mujica Reference Mujica, Masuda, Shimada and Morris1985; Stanish and Steadman Reference Stanish and Steadman1994), but related sherds have been found in the northern Lake Titicaca Basin. The style and its distribution are currently being redefined (Roddick and Janusek Reference Roddick and Janusek2018).

Figure 4. Qeya ceramics held by museums in La Paz: (a, c–f) Museo Nacional de Arqueología de Bolivia; (b) Museo de Tesoros Preciosos. Museum labels are (a) MNA-4, (b) Al/1158, (c) MUNARQ-152, (d) MNA-21, (e) MNA-12, and (f) MNA-254. Provenience is unknown for all six vessels. (Photos by Andrew Roddick.) (Color online)

Finally, transitional vessels (Figure 5) combine characteristics of Late Formative styles and Tiwanaku period Redwares (Couture and Sampeck Reference Couture, Sampeck and Kolata2003:228–232) such as proto-keros and early escudilla variants, which are known from multiple sites (Albarracín-Jordan Reference Albarracín-Jordan1992:148–151; Alconini Mujica Reference Alconini Mujica1995:78–81, 157–160; Bermann Reference Bermann1994:119, 147–148; Burkholder Reference Burkholder1997:177–179; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:49, 65–66, 88). The end of the Late Formative is defined by a regional explosion of iconic Tiwanaku Redwares (Figure 6) and the abandonment of all Late Formative decorated styles.

Figure 5. Transitional ceramics: (a) proto-escudilla from the Mollo Kontu sector of Tiwanaku; (b) Qeya-like jar sherds from Khonkho Wankane, context 12.13.5; (c) proto-kero with antler-like design from Lukurmata (floor of Structure 14; Bermann Reference Bermann1994:Figure 8.17b); (d) proto-kero from Qeya Qollo Chico (American Museum of Natural History); (e) proto-kero from Kala Uyuni (depositional Event KU-B237; Roddick Reference Roddick2009:Figure 9.21c); (f) proto-kero (Ethnologisches Museum Berlin). (Photos by Andrew Roddick and John Janusek.) (Color online)

Figure 6. Tiwanaku Redwares: (a) kero (type 3.2); (b) recurved tazón (type 4.4); (c) escudilla (type 5.3.1) from Lukurmata (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:Figure 3.50). (Photos by John Janusek.) (Color online)

Placing Decorated Assemblages in Time

Despite their rarity, decorated sherds continue to play the dominant role in Late Formative chronology. Stratigraphic sequences are consistent across the region: layers with Kalasasaya red-rimmed and zonally incised sherds are the deepest, then layers with only Kalasasaya red-rimmed sherds, then Qeya and transitional wares, and finally Tiwanaku Redwares (Bennett Reference Bennett1934:400, 450; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:38–40, 48; Marsh Reference Marsh2012c:180; Mathews Reference Mathews1992:100); however, this sequence is rarely complete. Initially, Bennett (Reference Bennett1934:399, 450) grouped all Late Formative styles as Early Tiahuanaco. Next, Carlos Ponce Sanginés (Reference Ponce Sanginés1981, Reference Ponce Sanginés1993) defined Tiwanaku I with both Kalasasaya varieties, Tiwanaku II with a lack of decorated pottery, and Tiwanaku III with Qeya vessels. Naming conventions presented further confusion, with Tiwanaku I and II merging into Tiwanaku I/II or, more simply, Kalasasaya followed by Qeya, which risked conflating rare decorated pottery with sociopolitical change (e.g., Browman Reference Browman1981:413; Mujica Reference Mujica, Masuda, Shimada and Morris1985:105).

The Wila Jawira Project, directed by Alan Kolata and Oswaldo Rivera in the 1980s and 1990s, conducted extensive excavation and survey at Tiwanaku and other sites. This project produced many radiocarbon dates, but surprisingly few from Late Formative contexts. As part of this project, Janusek (Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:37) built the first clear synthesis of decorated Late Formative styles, their stratigraphic relationships, and associated radiocarbon dates. He jettisoned Ponce Sanginés's labels in favor of a broader “Formative” terminology, but the phase definitions and dates are quite similar. Janusek suggests that during Late Formative 1A (200 BC–AD 250), Kalasasaya red-rimmed vessels were common and Kalasasaya zonally incised vessels were present but rare. During Late Formative 1B (AD 250–300), there was no decorated pottery. Finally, during Late Formative 2 (AD 300–500), Kalasasaya red–rimmed vessels were uncommon, and Qeya vessels were present.

Isbell and Knobloch (Reference Isbell, Knobloch and Young-Sánchez2009:188) proposed an alternative chronology based on iconographic patterns across the south-central Andes. They suggested that Qeya vessels and the Late Formative 2 phase came centuries later, AD 500–800. Although Qeya does represent a shift from “incised outlining to painted outlining of motifs” (Knobloch Reference Knobloch, Vranich and Stanish2013:211), we see this as an inadequate basis for redefining the phase. Treating Qeya as the only diagnostic style is problematic, especially because of its notable diversity and rarity; it may have even been a short-lived “aesthetic blip” in the regional sequence (Roddick and Janusek Reference Roddick and Janusek2018). The iconographic focus decontextualizes Qeya sherds from their provenience and, crucially, excludes other, much more common Late Formative decorated styles. In fact, only one radiocarbon date in the entire region has a reliable association with Qeya sherds (see the later discussion).

The principal cause of the differences between these two chronologies is the selection of radiocarbon dates. Janusek uses 23 radiocarbon dates, although many are not reliable (Marsh Reference Marsh2012a). In contrast, Isbell and Knobloch (Reference Isbell, Knobloch and Young-Sánchez2009) use only five dates (SMU-2118, NOSAMS-11306, Beta-91776, ETH-3177, and Beta-55490; see Supplemental Table 1 for corrected laboratory codes). These dates have medians of cal AD 460, 520, 590, 730, and 770, respectively, which lead them to suggest that Late Formative 2 began cal AD 500–550 and ended cal AD 700–750. Although their selection criteria are admirably stringent, the two latest dates are in fact associated with decorated sherds diagnostic of the Tiwanaku period, not the Late Formative (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:Chapter 12; Janusek Reference Janusek1999:117, Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:56).Footnote 2 In a more recent variant, Knobloch (Reference Knobloch, Vranich and Stanish2013) uses three dates (NOSAMS-11306, SMU-2471, and ETH-3177), again far too few dates to adjust the regional chronology.

It is time to reevaluate the Late Formative chronology. Ponce Sanginés's and Janusek's phases are defined by many unreliable dates that are statistically indistinguishable and have unclear material associations (Augustyniak Reference Augustyniak2004:32; Isbell Reference Isbell2004:216–218; Marsh Reference Marsh2012a; Mathews Reference Mathews1992:65). All prior chronologies are based on only two sites and define temporal limits based on impressionistic best fits of rounded probability distributions (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:47, 51; Knobloch Reference Knobloch, Vranich and Stanish2013). So far, regional chronologies have not taken advantage of the large sets of dates processed since the early 2000s, which are a significant part of our Bayesian models.

Methods: A Mixed Calibration Curve and Bayesian Models

First, we recalibrated dates to make them comparable (Supplemental Table 1), a necessary step that is not standard practice. Many researchers compare dates calibrated with recent curves to Janusek's (Reference Janusek and Kolata2003) chronology, which was calibrated with Stuiver and Pearson's (Reference Stuiver and Pearson1993) older curve. We use a “mixed calibration curve” (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013:722) that takes into account the unknown degree of mixture of atmospheric carbon from the Southern and Northern Hemispheres in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin (Marsh et al. Reference Marsh, Bruno, Fritz, Baker, Capriles and Hastorf2018). The mixed curve integrates both IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Warren Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffma, Hogg, Hughen, Felix Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Marian Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) and SHCal13 (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Hua, Blackwell, Niu, Buck, Guilderson, Heaton, Palmer, Reimer, Reimer, Turney and Zimmerman2013) and permits any mixture of the two curves, from 100% IntCal13 to 100% SHCal13. This approach eliminates the bias of specifying from which hemisphere carbon originates at the cost of slightly reducing the precision of probability distributions.

Next, we built Bayesian models based on stratigraphic relationships of contexts with decorated sherds and associated dates (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a). These site-specific Bayesian models allowed us to refine radiocarbon date probability ranges and interpolate ranges for contexts without dates, which notably increased the sample size of dates associated with Late Formative decorated sherds (Table 1). Finally, dates from the site-specific models were grouped in two uniform phase models and tested for outliers with a general outlier model. We manually removed outliers based on high probabilities of their being outliers (>5%) or low agreement indices (<60%; see Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b:1024). The boundaries of the models provide robust estimates of the first and last use of decorated ceramic styles.

Table 1. Counts of Dated Contexts with Kalasasaya Pottery Used in the Uniform Phase Models.

Note: Many other sites in the region have decorated styles from excavated contexts (Figure 1) but do not have reliably associated radiocarbon dates.

Models were implemented in OxCal 4.3 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a). Modeled dates and boundaries are presented in italics. In the text we include the medians, 95% probability ranges, and the name of the event in each model (see Supplemental Tables 1–11). Dates are rounded by 10 years. Except where noted, all models and dates have agreement indices of at least 60%, which is a threshold similar to the 5% confidence level in classical statistics (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a:356). Future research will update these probability ranges with improved calibration curves and Bayesian models, which we encourage by presenting the OxCal files in the supplemental materials. Bayesian models are particularly necessary for refining the chronology of the short Late Formative, which has a growing set of dates with highly overlapping probability distributions. Without Bayesian models, additional dates will blur rather than clarify temporal trends. Sets of dates are often presented as summed probability distributions, which is a popular but statistically weak method. Instead, we use more robust kernel density estimate (KDE) plots (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017).

Bayesian Models for Eight Late Formative Sites

We built Bayesian models of phases and sequences based on depositional sequences and Harris matrices at all eight Late Formative sites that have well-documented stratigraphies and radiocarbon dates: Tiwanaku, Lukurmata, Kirawi, Khonkho Wankane, Iruhito, Kumi Kipa, Sonaji, and Kala Uyuni (Figure 1; see details in Supplemental Data and Supplemental Tables 2–10).

Tiwanaku

Tiwanaku is the preeminent site in the region, with a current surface component of 3.84 km2 (Lémuz Aguirre Reference Lémuz Aguirre2004:12). We used published Bayesian models of Late Formative contexts that reassessed prior excavations (Marsh Reference Marsh2012a). These models include a refined date for a cache of 24 complete decorated vessels, of which 11 were zonally incised (Ponce Sanginés Reference Ponce Sanginés1993:55). Another three dates are from Kk'araña, a domestic sector north of the ceremonial core, including one associated with a wide-mouthed cup, a rare form among zonally incised vessels (Marsh Reference Marsh2012c). Finally, we made a uniform phase model of 29 dates associated with Tiwanaku Redwares and one date associated with transitional ceramic styles from the Putuni sector (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:Table 3.1; Yaeger and Vranich Reference Yaeger, Vranich, Vranich and Levine2013:139). Three pairs of dates from the same contexts were combined, but this model does not otherwise include stratigraphic relationships.

Lukurmata

Lukurmata is a ceremonial center on the southern shore of Lake Titicaca. We modeled the sequence of domestic occupations on the site's main ridge. The earliest decorated style found there is Thin Redware (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:59–65), followed by the only occupational contexts with Kalasasaya red-rimmed sherds at the site. There are a few incised sherds in these early levels, but it is not clear to which style they belong. Next, residents again deposited Thin Redware sherds in Structures 7–10, a style that was apparently not used at other sites. Next, three successive occupations had a diversity of Qeya-style sherds, which were more common than elsewhere at 8% of sherds (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:119, 135, 144). Structures 22–24 represent the third and final occupation with Qeya sherds. This occupation, with both Qeya and Tiwanaku Redwares, marks the inflection points between the two styles (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:143–148). There were a number of dates associated with Redwares at the site, but they were excluded because they had a minor effect on the modeled result.

Kirawi

Kirawi (CK-65) lies east of Lukurmata in the Katari Valley and is an important site in Tiwanaku's breadbasket (Janusek and Kolata Reference Janusek, Kolata and Kolata2003, Reference Janusek and Kolata2004). There are three dates associated with Kalasasaya red-rimmed sherds, but there was not enough information to construct a model with undated contexts. This site has the latest date associated with red-rimmed vessels in the region (Beta-91776). This may reflect different timings associated with the changing production of decorated styles across the region (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:51–52), the use of heirloom vessels by later generations (Roddick Reference Roddick, Swenson and Roddick2018), or it may simply be a statistical anomaly: its two-sigma range overlaps with earlier dates. Despite the short distance to Lukurmata, no Qeya vessels were recovered at Kirawi.

Khonkho Wankane

Khonkho Wankane, located 28 km due south of Tiwanaku, is the only site other than Tiwanaku with Late Formative monumental architecture (Figure 1; Janusek Reference Janusek2015b; Marsh Reference Marsh2016). Bayesian models are based on Smith's (Reference Smith2016) detailed sequence of construction events, which effectively constrains the 24 dates from the site. We updated the model of Khonkho Wankane with four previously unpublished dates. Eleven dates are associated with Kalasasaya red-rimmed sherds, which were recovered throughout the primary occupation of the site (3.6% sitewide and 5.5% in domestic areas, by sherd count) but were absent during the earliest phases.

Other decorated styles were present but rare. On an occupation floor (context 12.71.2.F2), researchers found 10 Kalasasaya zonally incised sherds from a single jar with geometric designs painted in dark gray and dark red. Near one of the sunken courts, architectural fill contexts overlaying earlier wall foundations included two sherds from a single proto-kero (context 1.15.3) and a sherd from a Qeya-like jar (context 1.3.5). A nearby context (1.10.2) was dated, but the stratigraphic association with the decorated ceramic sherds was not clear, so this date (AA-66948) was not included in the Bayesian model. In other sectors of the site, excavators recovered a Qeya incensario with a modeled feline head (context 4.19.12) and seven sherds from a Qeya-like jar with a black-and-red geometric design (context 12.13.5; Figure 5b).

Iruhito

West of Khonkho Wankane, Iruhito stretches along the bank of the Desaguadero River (Pérez Arias Reference Pérez Arias2013; Smith and Janusek Reference Smith and Janusek2014; Smith et al. Reference Scott C., Arias, Arias and Janusek2017). The only Late Formative decorated ceramic sherds at the site were two to three Kalasasaya red-rimmed sherds from a burial context (415.5). The site was occupied during the Formative and Tiwanaku periods, but there may have been an occupational hiatus for much of the Late Formative.

Kumi Kipa

Kumi Kipa is a large 14 ha site on the Taraco Peninsula (Bandy Reference Bandy2001:102, 177, 182). The Late Formative context KK-ASD 1 provided two radiocarbon dates in association with Kalasasaya red-rimmed and zonally incised pottery. The depositional events were modeled as two short parallel sequences. Excavations recovered eight Qeya sherds (Events A22 and A24), but there are no associated dates.

Sonaji

Sonaji is located just a few hundred meters from Kumi Kipa and has a Late Formative surface component of 6.75 ha (Bandy Reference Bandy2001:177, 182). The site is defined by a sequence of terraces, including a deep excavation of occupations from the Middle Formative to late Tiwanaku phases. We built two parallel models for the middle and upper terraces at the site, which comprise eight depositional events associated with Kalasasaya red-rimmed and zonally incised sherds. There is no radiocarbon date for Event A265, which includes the only Qeya sherd at Sonaji.

Kala Uyuni

Kala Uyuni, located 4 km from Sonaji, was one of the region's principal Late Formative centers (Bandy and Hastorf Reference Bandy and Hastorf2007) and has a surface component of 14.75 ha (Bandy Reference Bandy2001). The Early and Middle Formative occupations were ritually closed before Late Formative inhabitants constructed a new platform (Roddick et al. Reference Roddick, Bruno and Hastorf2014:146–148). We built Bayesian models for three of the sectors. The area west of KU-ASDs 2, 4, and 5 included ceramic production tools and a burial with a complete Kalasasaya red-rimmed bowl (Roddick Reference Roddick2009:122, 210, Figure 9.9b). KU-ASD 2 and KU-ASD 5 were occupied in the earlier and later Late Formative, respectively. Outside KU-ASD 5, excavators found an unusually complete sequence of rare decorated styles: Kalasasaya zonally incised (Event B271), a transitional proto-kero (B237; Figure 5e), a Qeya vessel with a modeled feline head (B235), the only two Qeya sherds from this site, and finally Tiwanaku Redwares (Roddick Reference Roddick2009:121, 343, 372, 434, Figure 5.3, Figure 9.21c).

Bayesian models of these eight sites rely on detailed stratigraphic relationships to constrain probability ranges. The fine-grained nature of the excavations allowed us to reduce the probability ranges of dates associated with decorated ceramic sherds and also interpolate the timing of undated events. Both types of dates are included in the uniform phase models, which estimate the temporal inflection points of each style.

Results: Uniform Phase Models of Decorated Ceramic Styles

In the uniform phase models, probability distributions of individual dates are refined by (1) the mixed calibration curve, (2) site-specific stratigraphic relationships, and (3) the assumption that the events belong to the same ceramic phase, based on the fact that they all are associated with the same decorated style. We experimented with many models, including models without stratigraphic constraints or interpolated dates. We also made models of the few Qeya dates. All of these models produced very similar results, though usually with large error ranges. Another preliminary model assumed the regional sequence of styles: Kalasasaya red-rimmed, Qeya and transitional, and finally Redwares. Although this model produced more precise boundaries, it requires the assumption that this sequence holds at every site with no temporal overlap between styles. While stratigraphic sequences support this assumption, we prefer the style-based models that do not require it. To create the final models (see the supplemental materials), we exported and grouped posterior probabilities from the site-specific models into two uniform phase models. The first is for both Kalasasaya styles (Figure 7; Table 1), with zonally incised sherds modeled as a subphase within the more extensive phase of red-rimmed sherds. The second model is for dates from Tiwanaku associated with transitional vessels and Redwares. Thin Redware, Qeya, and transitional styles had too few associated dates to build style-specific models. Because these models are built to reveal regional trends, there could be individual exceptions.

Figure 7. Starting (green, on the left) and ending (red, on the right) boundaries for uniform phase models for dates associated with (a) Kalasasaya red-rimmed and (b) zonally incised sherds. Gray curves (middle) show KDE plots that summarize the temporal density of dated events. Crosses and bars show the median and 68% probability ranges of the boundaries. The three rows of crosses below the curves show the medians of dates when modeled by stratigraphy and then as a phase, modeled only by stratigraphy, and only calibrated (unmodeled). (Color online)

Kalasasaya Red-Rimmed and Zonally Incised Sherds

In all contexts with Kalasasaya zonally incised sherds, red-rimmed sherds are also present, which is a significant depositional pattern repeated throughout the region. This may be because (1) sherds of the two styles can come from a single vessel (see Figure 3) or (2) vessels of both styles were deposited together. Stratigraphic sequences show that red-rimmed vessels continued to be used after zonally incised sherds dropped out of the regional assemblage. At Kumi Kipa, Sonaji, and Kala Uyuni, there were 38 depositional events with both styles: 214 red-rimmed and 54 zonally incised sherds, with an average ratio of 4:1.

A single model was created for both styles, which groups all dates in an overall phase that includes a subphase for contexts with zonally incised sherds (Figure 7; Supplemental Table 11). The model included 27 contexts with radiocarbon dates and an additional 17 contexts with interpolated dates. Three outliers were removed—two early (context ASD 2 from Sonaji, which has both Kalasasaya styles, and 415.5 from Iruhito) and one late (the Level 8 context from Kirawi). A total of 41 depositional events from seven sites provide a robust estimate of the regional timing of Kalasasaya red-rimmed vessels. The starting and ending boundaries are cal AD 120 (median; 60–170; 95% probability; Start Kalasasaya, both styles) and cal AD 420 (median; 380–470, 95% probability; End Kalasasaya red-rimmed). This style was probably made and used by around 10 generations, an estimate based on the medians and cross-cultural generation lengths of around 30 years (Fenner Reference Fenner2005).

Janusek (Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:54) suggests that Kalasasaya red-rimmed vessels became less common over time and there was a brief phase without decorated pottery, but a KDE plot of the associated depositional events shows continuity over time (gray curve in Figure 7a). The analysis also suggests that the absence of decorated sherds is not a reliable temporal indicator (Burkholder Reference Burkholder1997:166–172; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:44; Mathews Reference Mathews1992:74–76). Instead, it likely reflects strong intrasite spatial variation in decorated sherd frequencies (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:72; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:46; Marsh Reference Marsh2016:320).

The Kalasasaya zonally incised subphase comprises 10 contexts from four sites: Tiwanaku, Kumi Kipa, Sonaji, and Kala Uyuni. It has the same starting boundary as the overall Kalasasaya model. We opted to exclude an ending boundary for this subphase because this created models with unexpectedly low agreement indices, short spans, and late starting boundaries. Instead, a query with the Last command suggests that the end of the subphase was near AD 240 (190–340, 95% probability) from the model with the highest overall agreement index (111%). We attempted a series of other models, which all resulted in median ending boundaries between cal AD 200 and 250 with 95% error ranges of 130–150 years. Nine of the 10 dates in the subphase have medians of cal AD 190 or earlier, whether modeled or not, but three contexts with zonally incised sherds fall much later, so we excluded them from the subphase. The model estimated their medians at cal AD 250, 300, and 340 for contexts from Kk'araña (AA-89413), Sonaji (Event A52, A54, A57, A59), and Kala Uyuni (Events B9, B10, B16, B17, B57, and B78), respectively. The 95% probability ranges overlap with the rest of the dates from the zonally incised subphase, so they could simply be statistical outliers. Nevertheless, we cannot confidently exclude other potential issues such as imprecise association with very few zonally incised sherds, taphonomic disturbance, or the possibility that a few people in the region produced or curated these vessels much later than others. The KDE plot of this subphase shows that the majority of associated events fall within a century of the starting boundary for all Kalasasaya sherds (Figure 7b), but there are exceptions. An improved Bayesian model of this subphase will require additional radiocarbon dates and refined stratigraphic models. The style seems to have been in use for around four generations, a short lapse that helps explain its rarity.

Qeya

Qeya sherds are known from six of the sites modeled here (they have not been recovered at Iruhito or Kirawi). At most of these sites, there are less than around 10 Qeya sherds out of many thousands of sherds from carefully excavated contexts. The important exception is Lukurmata, where Qeya sherd counts reached 8%. Our only directly associated date is from Lukurmata's Structure 16 (SMU-2118; Bermann Reference Bermann1994:57, 103),Footnote 3 but the site's Bayesian model was able to estimate dates for three depositional events with Qeya sherds, which have medians of cal AD 420, 440, and 530. We excluded dates from Tiwanaku (Hv-18) and Khonkho Wankane (AA-66948) from the models because of ambiguous associations with Qeya sherds (see details in Marsh Reference Marsh2012a:211), although they have similar medians: cal AD 430 and 520, respectively. There are too few reliable dates to build a model for Qeya sherds, so we prefer dating these sherds based on their consistent stratigraphical location, above both Kalasasaya styles and below Tiwanaku Redwares.

Transitional Vessels and Redwares at Tiwanaku

Transitional vessels have only one associated radiocarbon date (NOSAMS-11360) from the earliest occupation of the Putuni elite residential area at Tiwanaku (Couture and Sampeck Reference Couture, Sampeck and Kolata2003:228–232), with a median of cal AD 520. This median is similar to those associated with Qeya sherds, which support the relative stratigraphic dating of Qeya and transitional styles: they were contemporaneous, they postdate Kalasasaya red-rimmed pottery, and they predate Redware styles. Because Qeya and transitional sherds are so rarely excavated, it may be fruitful to consider thermoluminescence dates on sherds from survey and museum collections.

The site models for Tiwanaku and Lukurmata independently estimate the inflection point between Qeya and transitional styles and Redwares. The results are strikingly similar: at Tiwanaku the inflection point is cal AD 590 (median; 500–660, 95% probability; Start Redwares); at Lukurmata it is cal AD 590 (median; 420–760, 95% probability; Structures 22–24). The inflection point at Tiwanaku is more precise, so we use it as our current best estimate of the earliest appearance of Redwares in the region.Footnote 4 A preliminary model showed a minor reduction in the probability ranges by assuming that the inflection points at both sites were synchronous, but we chose not to make this assumption. Future research could refine the Redwares chronology with dates from other regional sites, which all have later dates for contexts with Redwares (e.g., Augustyniak Reference Augustyniak2004; Bauer and Stanish Reference Bauer and Stanish2001; Isbell and Burkholder Reference Isbell, Burkholder, Isbell and Silverman2002; Korpisaari and Pärssinen Reference Korpisaari and Pärssinen2011; Mathews Reference Mathews1992; Pérez Arias Reference Pérez Arias2013; Seddon Reference Seddon1998).

Discussion: A Revised Decorated Ceramic Chronology

We can now update the chronology of decorated pottery from the Late Formative (Figure 8; Table 2). Instead of the traditional block format and its limitations, we use inflection points to mark discontinuities or “stoppages” in aspects of ceramic production, moments when novel decorations may have played a role in a coeval restructuring of social relationships. Lake Titicaca Basin archaeologists have long believed that ceramic producers and consumers participated in such ruptures—after all, they are the implicit basis of the chronographics we are engaging here. Our focus on inflection points helps us locate the times when preferences in the decoration of pottery shifted, perhaps in tandem with other cultural practices and traditions. The improved precision of Bayesian models moves our chronological resolution closer to an anthropological timescale of generations and the people who made, used, and discarded decorated pottery (Roddick and Hastorf Reference Roddick and Hastorf2010:161; Roddick et al. Reference Roddick, Bruno and Hastorf2014).

Figure 8. Summary of proposed phases (top line of text) based on inflection points in Late Formative decorated ceramic styles (second line of text). The bars with arrows indicate the medians and 68% probability ranges of the inflection points between phases, as defined by the boundaries of uniform phase Bayesian models. Bottom, in blue, the same inflection points are shown as probability curves with the medians as crosses and the 68% probability ranges as bars below each curve (Table 2). The curves do not represent the rising and falling popularity of the styles but instead the temporal uncertainty of each inflection point between each style (the wider the curve, the less certain), as defined by the horizontal axis. The larger the area under the curve, the greater the probability it includes the true date. For the initial use of Redwares, the figure shows the inflection point at Tiwanaku; the curve from Lukurmata is centered at the same point but much wider. Thin Redware was excluded because it does not seem to have a regional chronological trend. The founding of sites and major construction projects are concentrated in the late first and early second centuries AD, slightly before the earliest use of both Kalasasaya decorated styles. Site abandonments tend to be in the first half of the fifth century AD, shortly following the latest use of Kalasasaya red-rimmed ceramics. There are no chronological bars for site foundings and abandonments because the temporal ranges have not been precisely defined. (Color online)

Table 2. Inflection Points in Decorated Pottery during the Late Formative.

Note : Dates are calibrated medians with 95% probability ranges in parentheses, as shown in Figure 8.

Initial Late Formative

The Initial Late Formative is a long phase of around 12 generations. This poorly defined phase began at the end of the Middle Formative around 250 BC, a rough date suggested by Bandy (Reference Bandy2001:118) that agrees with our preliminary Bayesian models. At this time, ritual spaces were closed as part of a rupture in depositional and ceremonial history (Roddick et al. Reference Roddick, Bruno and Hastorf2014:148). Because the phase has almost no decorated ceramic sherds and very few dated occupations, it has been difficult to identify in excavations. The lack of a pattern may reflect a substantial shift in potting practices and settlement patterns. It may also reflect excavation choices or accidents of sampling decisions, although some excavations have specifically targeted these centuries (Bandy and Hastorf Reference Bandy and Hastorf2007; Ponce Sanginés Reference Ponce Sanginés1993). It seems that during this long span, there was virtually no decorated pottery made or imported in the region. Recently available dates from Iruhito will further clarify this phase, but the associated occupations do not have decorated ceramic sherds (Smith et al. Reference Scott C., Arias, Arias and Janusek2017).

Toward the end of the Initial Late Formative, in the first century AD, Lukurmata was founded, and residents used and discarded Thin Redware, the only decorated pottery associated with this phase at any site. Next, there was a surge of construction activity and residential mobility in the late first and early second century AD. Major Late Formative sites—Tiwanaku, Lukurmata, Khonkho Wankane, and Kumi Kipa—were founded, and at previously inhabited Sonaji and Kala Uyuni, people built new civic spaces. These contemporaneous changes seem to be the beginning of a major regional social reorganization that has not yet been dated precisely. Future research might address this dating using Bayesian models of construction events (see Smith Reference Smith2016; Yaeger and Vranich Reference Yaeger, Vranich, Vranich and Levine2013).

Late Formative 1 and 2

Late Formative 1 began with a “decorative bang” in ceramic style. Two new varieties of Kalasasaya decorated pottery were made for the first time (Figure 3), a major innovation following centuries of potting without decoration. After this rupture in potting practices, Kalasasaya red-rimmed vessels appeared at nearly all sites in the region (Figure 1), including sites where they were only present during a single occupation (Lukurmata, Iruhito, and Iwawe). Our best estimate for the beginning of Late Formative 1 is cal AD 120 (median; 60–170, 95% probability; Start Kalasasaya, both styles).

Our data suggest we can finally abandon Janusek's (Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:45) proposed Late Formative 1B, a short subphase defined by an absence of decorated pottery (Marsh Reference Marsh2012a:214; Mathews Reference Mathews1992:65; Roddick Reference Roddick2009:170). The KDE plot of Kalasasaya red-rimmed vessels (the gray curve in Figure 7a) shows that these vessels were used throughout Late Formative 1 and 2. During Late Formative 2's six generations, there was a notable absence of complex, colorful designs that are featured in earlier Kalasasaya zonally incised and later Qeya and transitional styles.

Our tentative estimate for the transition between Late Formative 1 and 2 is based on the final deposition of most contexts with Kalasasaya zonally incised vessels around cal AD 240 (median; 190–340, 95% probability; Last Kalasasaya zonally incised). This change in decorated pottery may correlate with other shifts in material practices between Late Formative 1 and 2, a potential focus of future research. There are shifts in Mocachi monolith styles (Browman Reference Browman1997; Marsh Reference Marsh2012b:88–98; Ohnstad Reference Ohnstad2011), undecorated pottery (Bandy Reference Bandy2001:170–173; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:51–54; Lémuz Aguirre Reference Lémuz Aguirre2001:162–169; Marsh Reference Marsh2012b:225–227; Roddick Reference Roddick2009:164–165, 226–228), ceramic buttons, basalt hoes, projectile points, pyro-engraved bone tubes, and quicklime blocks (Bennett Reference Bennett1934:425, 451; Bermann Reference Bermann1994:72; Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:54; Marsh Reference Marsh2012b:157–160, 212–214; Mathews Reference Mathews1992:102–103; Roddick et al. Reference Roddick, Bruno and Hastorf2014:151; Smith and Pérez Arias Reference Smith and Arias2015:110–113).

Terminal Late Formative

The Terminal Late Formative is marked by the deposition of Qeya and transitional styles. Their stratigraphic position lets us infer that they were used no earlier than the end of the Kalasasaya style, cal AD 420 (median) and no later than the earliest Tiwanaku Redwares, cal AD 590 (median), a span of five to six generations. The few dates we have for Qeya and its transitional styles have medians that fall in this range.

These rare styles emerged during a time of “stylization” when potters produced vessels with denser iconographic elements and more of them (Roddick Reference Roddick2009:393–394). Design style, technological choice, and consumption practices may have been entangled with a widespread redefinition of group identities (Janusek Reference Janusek and Kolata2003:54). The diversity of decorated ceramic styles at this time is consistent with a rapid social reorganization and high residential mobility (Mathews Reference Mathews1992:131). Terminal Late Formative occupations at Lukurmata were the first to include hallucinogenic paraphernalia and imported ceramic styles, sodalite, obsidian, and marine shell (Bermann Reference Bermann1994:145–147). At the same time, Tiwanaku became the paramount destination for migrants who began to flood into the burgeoning city (Bandy Reference Bandy2001:196–198, Reference Bandy, Vranich and Levine2013; Marsh Reference Marsh2012b:446–456; Mathews Reference Mathews1992:131–139). The immigrants probably included people from Kala Uyuni and Khonkho Wankane, major settlements that were abandoned during this phase. These immigrants’ lasting impact on Tiwanaku can be seen in the strong material continuity in architectural orientation, monolith iconography, temple layout, design of drainage canals, astronomic alignments, utilitarian pottery, and domestic practices (Janusek Reference Janusek2015b; Marsh Reference Marsh2012b:471–479).

The end of the Terminal Late Formative is marked by the initial use and deposition of Tiwanaku Redwares, which replaced previous decorated styles at around cal AD 590 (median). This marks a watershed in ceramic decoration, as well as in culinary and feasting practices, as the “hospitality state” blossomed and the population of Tiwanaku boomed (Bandy Reference Bandy, Vranich and Levine2013; Goldstein Reference Goldstein and Bray2003:158). A refined chronology paves the way for more nuanced questions on the relationships between decorated pottery, specialized ceramic production, and political change.

This initial Bayesian effort at a refined chronology leads to a range of productive reconsiderations of previous excavation and survey data. For example, the timing of Bandy's (Reference Bandy2001) population and growth indices, which are based on surface distributions of decorated pottery, could be reassessed with the inflection points defined here. Building on Isbell and Knobloch's efforts to explore larger-scale iconographic shifts, we might begin to reconcile chronologies in adjacent regions such as the northern Lake Titicaca Basin, Wari sites in Peru, and Tiwanaku sites in central Bolivia and on the western slope of the Andes. Such comparisons would help clarify the timing, speed, and nature of social interactions and movement across the central Andes.

Conclusion

Recently processed radiocarbon dates and Bayesian models allow us to estimate inflection points of Late Formative decorated ceramic styles in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin (Figure 8; Table 2). After the end of the Middle Formative around 250 BC, we identify a conspicuous gap with almost no decorated ceramic sherds that we call the Initial Late Formative. The first inflection point in decorated pottery marks the start of Late Formative 1 around cal AD 120 (median), when Kalasasaya red-rimmed and zonally incised vessels were made and used for the first time throughout the region. The next inflection point is between Late Formative 1 and 2 and marks the final production and use of Kalasasaya zonally incised pottery around roughly cal AD 240 (median). The Formative Kalasasaya red-rimmed pottery, the most ubiquitous decorated style in the region, continued in circulation until around cal AD 420 (median), when the Terminal Late Formative began. After this date, ceramic variability intensified as Qeya and transitional wares defined decorated assemblages until the earliest production of Redwares at Tiwanaku around cal AD 590 (median).

The inflection points defined here provide temporal anchors that should continue to be refined with additional dates, improved models, and chronologies of other material classes. We suggest that these models make the best of currently available data, although we recognize the limitations of defining a period with a single material class. Future efforts should be explicit about what material classes and dates are being used to define phases before making inferences about social change. Because this chronology is based on a robust methodology and a large, updated database, we hope it marks a step forward in alleviating confusion that arose from previous chronologies and is a solid foundation for future refinements.

The Late Formative is a crucial period in the cultural history of the Lake Titicaca Basin, which witnessed the rapid social changes that accompanied the emergence of the Tiwanaku state. The Late Formative continues to be a challenging period to document, but we hope that in this article we begin to repair its reputation as the “most obscure, complex, and poorly understood period” of the region (Lémuz Aguirre and Paz Soria Reference Lémuz Aguirre and Soria2001:105; translation by the authors). With an improved chronology of decorated pottery, future research can refine the chronologies of other material practices and begin exploring more subtle shifts across the social landscape.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this article to two scholars who provided watershed contributions on the ceramics of the southern Lake Titicaca Basin. Dwight Wallace and our co-author John Janusek passed away in October 2019 as we finalized this manuscript. Research at Khonkho Wankane and Iruhito was generously supported by the Curtiss T. and Mary G. Brennan Foundation, Vanderbilt University Discovery Program, Howard Heinz Foundation, National Geographic Society (7700-04), the National Science Foundation (BCS-0514624), Sigma Xi, Franklin & Marshall College, the University of California, Riverside, and the University of California, Santa Barbara. Research at Sonaji, Kumi Kipa, and Kala Uyuni was supported by the National Science Foundation (BCS-0631282 and BCS-0321720), Tinker Travel Grants, the Lowie-Olsen and Stahl Foundation, and the University of California, Berkeley. Excavations at Kk'araña were funded by a Fulbright–Hays grant (P022A070024). Thank you to all the members of Proyecto Kala Uta, Proyecto Jach'a Machaca, and the Taraco Archaeological Project. There are no conflicts of interest. This article has benefited from ongoing discussions and a lively exchange of unpublished theses and reports with Carlos Lémuz Aguirre, Matthew Bandy, José Capriles, Antti Korpisaari, Arik Ohnstad, Adolfo Pérez Arias, Maribel Pérez Arias, Luis Viviani Burgos, and Jennifer Zovar. Alex Bayliss, Andrew Millard, Bruce Owen, and Christopher Bronk Ramsey patiently responded to the first author's questions on OxCal's syntax. The Bayesian models were improved by Ray Kidd's persistent error checking and experimentation. Two reviewers offered highly constructive criticisms. We are grateful to all of these individuals. All errors of fact and interpretation are our own.

Data Availability Statement

The radiocarbon dates and Bayesian models in the supplementary materials are also available from the data repository of the University of California at https://doi.org/10.6078/D1QD66.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2019.73.

Supplemental Table 1. Calibrated dates.

Supplemental Table 2. Tiwanaku LF.

Supplemental Table 3. Tiwanaku Redwares.

Supplemental Table 4. Lukurmata.

Supplemental Table 5. Kirawi.

Supplemental Table 6. Khonkho.

Supplemental Table 7. Iruhito.

Supplemental Table 8. Kumi Kipa.

Supplemental Table 9. Sonaji.

Supplemental Table 10. Kala Uyuni.

Supplemental Table 11. Kalasasaya ceramics.

References Cited for Supplemental Table 1.

All_sites_stratigraphy OxCal code.txt

Kalasasaya both styles OxCal code.txt

OxCal models and priors (This folder contains 59 files. To produce the results in this folder, we first ran the model “All_sites_stratigraphy.” Next, we exported probability distributions as individual prior files and saved them to the same folder. Finally, we ran the model “Kalasasaya both styles,” which uses these prior files. To avoid rerunning the analysis, the models’ results can be uploaded and viewed in OxCal (the files with these extensions: js, oxcal, log, and txt).