1. Introduction

The motto of many US police departments is ‘to protect and serve.’ Yet much of the conversation on American policing highlights its predatory aspects (Davis, Reference Davis2021), including racial bias in policing (Reference DavisDavis forthcoming), police killings of unarmed civilians (Surprenant and Brennan, Reference Surprenant and Brennan2019), and militarization of municipal police departments (Coyne and Hall, Reference Coyne and Hall2018). The policing situation is especially dire on many of America's 300-plus Indian reservations. According to government data, which are believed to significantly underreport the rate of violence American Indians experience (Crepelle, Reference Crepelle2020), American Indians are victimized at rates comparable to cities with large urban populations such as Baltimore, Chicago, and Detroit. American Indian women are 1.2 times more likely to experience violence in their lifetime and 1.7 times as likely to experience violence in the past year as non-Hispanic white-only women. American Indian men are 1.3 times more likely to experience violence than non-Hispanic white-only men in their lifetime. The overwhelming majority of violence committed against American Indians in Indian country is at the hands of non–American Indians although crime in the United States is overwhelming between persons of the same race (Rosay, Reference Rosay2016). American Indians are also disproportionately killed by police, leading CNN to refer to American Indians as the forgotten minority in police shootings (Hansen, Reference Hansen2017).

Institutionalists have only modestly attended to policing on American Indian reservations. We remedy this by considering extending insights from Elinor Ostrom's research on community policing for reservation policing. Ostrom and her colleagues found that policing was more effective when organized at the neighborhood level, as opposed to at the metropolitan level, thus offering a polycentric alternative to the consolidation of municipal policing (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Parks and Whitaker1973, Reference Ostrom, Parks and Whitaker1978).

Subsequent studies have considered barriers to adoption of community policing, such as reliance of local police on federal funding, the militarization of police, and erosion of genuine public-private partnerships (Boettke et al., Reference Boettke, Palagashvili and Lemke2013, Reference Boettke, Lemke and Palagashvili2016), increasing attention of local police to federal priorities (Boettke et al., Reference Boettke, Palagashvili and Piano2017), and traditional notions of police roles that undermine efforts to reform policing (Skolnick and Bayley, Reference Skolnick and Bayley1988). Herbert (Reference Herbert2001) finds that broken windows (order maintenance) policing is more amenable to police culture and hence more likely to be adopted, thus offering insight into the cultural barriers to Ostromian policing. There are also tensions in empowering the ‘community’ to influence the police, as this may undermine the goal of objective rule enforcement (Stenson, Reference Stenson1993).

Beyond these challenges with implementing community policing, we highlight two issues with analysis of Ostromian policing. First, it is not clear from Ostrom's earliest work why neighborhood policing works better than metropolitan policing. Any level of policing can be subject to rent-seeking, bureaucratic incentives, and short time horizons (Boettke et al., Reference Boettke, Coyne and Leeson2011), including neighborhood policing. Second, federal, state, and municipal police forces allegedly implemented community-oriented policing starting in the 1980s (Kelling and Moore, Reference Kelling and Moore1988). The Office for Community-Oriented Policing Services (COPS) in the US Department of Justice envisions a consensus in policing around building police-community partnerships, problem-solving, and crime prevention (Fegley, Reference Fegley2021). Thus, it is necessary to develop a framework to assess ‘community policing’ that is not limited to comparing neighborhood policing with metropolitan policing, as well as to clarify more precisely the conditions why decentralization of policing improves policing services compared to more centralized policing regimes.

We introduce the concept of Ostrom-Compliant Policing to analyze community policing. While Elinor Ostrom developed original insights into community policing, she only later developed the design principles for self-governance. Ostrom's Understanding Institutional Design (2005) was published decades after the original studies of neighborhood policing and were based mostly on resource governance. Therefore, we update the knowledge gathered from Ostrom's later work to understand ongoing barriers to community policing, which we refer to as Ostrom-Compliant Policing. This allows us to be precise about what we mean by community policing (is the community policing effort Ostrom-Compliant?) and further, we can assess its consequences (does Ostrom-Compliance improve the quality of policing services?).

After we articulate the features of Ostrom-Compliant Policing, we use the framework to analyze policing in Indian country. American Indian reservations provide a unique opportunity for comparative institutional analysis of policing since any given reservation will fall into one of three categories: federal policing by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), policing by municipal jurisdictions, and tribal policing. Tribal policing is an especially interesting arrangement for the debate between polycentrists such as Ostrom and consolidationists who favor more centralized policing regimes. Tribal policing arises through a contract with a Nation and the BIA (called a Public Law 93–638, which authorized such agreements). PL 638 contracts move authority from the BIA to the tribes and are considered to be a move toward self-governance of policing.

We show that each of these policing regimes falls short of Ostrom-Compliant Policing. Though the finding that federal and state policing are not Ostrom-Compliant is perhaps unsurprising, tribal policing through PL 638 contracts also falling short is more surprising and highlights ongoing constraints on tribal self-governance as a significant barrier to reform. Our research thus complements earlier work finding that reliance of municipalities on federal spending undermines community policing by showing how federal rules can also obstruct Ostromian policing.

2. A history of policing in Indian country

Before 1800, American Indians relied on ‘traditional’ policing: formal rules, transmitted through custom, stories, and sacred songs, that were understood, accepted, and enforced by tribes.Footnote 1 Traditional policing included enforcement of laws based on personal or collective responsibility, including laws of revenge, which were in some instances enforced by appointed law enforcement officials (Luna-Firebaugh, Reference Luna-Firebaugh2007) or by appointed members of military societies (Meadows, Reference Meadows2002). These tribal police enforced the tribe's laws, such as those governing community hunts, and their roles were accepted as legitimate even though they were not codified by a government.

Starting in the early 19th century, some tribes began to replace traditional policing with codified law enforcement institutions, including Lighthorsemen (elected law enforcers and adjudicators), sheriffs, marshals, and constables, based on concepts introduced to Indians during colonial times through, for example, intermarriage of Indians and Europeans. To an extent, these changes were functional: increasing populations and interactions between non-Indians and Indians on Indian lands required policing institutions to evolve. For example, the Lighthorse police force of the Cherokee initially dealt with petty crimes and horse theft with jurisdiction later expanding to major crimes (robbery, murder, and rape) along with crimes against public order, including public intoxication. The Lighthorse combined the roles of sheriff, judge, jury, and executioner, often using violence to enforce the laws (Blackburn, Reference Blackburn1980). By the mid-19th century, each of the largest tribes had begun the gradual replacement of laws of clan revenge with codified policing institutions (Karr, Reference Karr1998).

After the Civil War, the federal government asserted authority over reservation policing in the hopes of assimilating Indians into white culture. The establishment of reservation police and judges, staffed by BIA administrators with little experience in Indian country, along with government programs to destroy tribal culture (especially boarding schools and allotment of land), were part of federal policy to civilize Indians (Hagan, Reference Hagan1966). Federal policing policies also involved a divide-and-conquer. The BIA selected Indians from different bands to police a reservation. This exacerbated conflict between tribes that emerged because the government habitually forced tribes with no shared history or culture to live together on reservations (Dippel, Reference Dippel2014). The BIA relied heavily on coercion to bring Indians into this system, including by withholding tribal annuities when tribes failed to enforce federal laws as the BIA demanded even though many reservation Indians were already starving (Hagan, Reference Hagan1966). Given these incentives, Indians began to adopt the policing institutions preferred by the federal government. Further, the BIA police broke allegiances among Indians. For example, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, leaders in the struggle for Indian self-determination, were killed by BIA police.

The government experimented with alternative policing arrangements on reservations, including partnerships with state and federal governments. For example, the government provided the Navajo Nation with some autonomy over-policing. After the Long Walk – the violent deportation of Navajo from Arizona to New Mexico – and internment of the Navajo people at Camp Bosque Redondo from 1864 to 1866, soldiers initially hoped to force the roughly eight thousand Navajo who had survived the 400-mile trek to live together with the Apache. They eventually allowed the Navajo to police themselves, provided their leaders agreed with the federal government to recruit one hundred young Navajo warriors to be led by war chief Manuelito to police Navajo accused of livestock raiding. The Navajo police were perhaps too effective, for crime decreased so much that they were disbanded in 1873 (after only a year in operation); when they were reinstated in 1874, they were paid out of tribal annuities rather than with additional funding from the federal government (Jones, Reference Jones1966).

In 1878 Congress approved the establishment of the federal Indian police and by 1890 nearly all reservations had them. The difference was that in contrast with tribe-created reservation policing, which relied heavily on the financial support of tribal members, the new federal Indian police forces received allotments for themselves and their families. They were expected to be ‘civilized’ (hard working and abstaining from drinking), wear uniforms, and curtail the tribal chiefs' prerogatives and advance non-Indian law, for which they were provided better pay and armed with revolvers (Hagan, Reference Hagan1966). The laws they enforced included assimilationist policies, such as attendance in boarding schools and abiding by the criminal codes established by the government, many of which were inconsistent with tribal customs.

The complicated jurisdictional rules governing reservation policing emerged during this period. The Supreme Court's decision in the 1883 case Ex Parte Crow Dog, in which a Brule Sioux member killed a tribal chief, disavowed federal jurisdiction over reservation crimes involving only Indians.Footnote 2 The traditional Sioux punishment of restitution was deemed too light; accordingly, Congress responded by passing the Major Crimes Act in 1885, based upon the notion that tribes were incompetent to punish ‘major crimes’ (Washburn, Reference Washburn2005: 798–799). This was one of the first major steps in removing certain crimes from the control of Indians. In addition, the Dawes Act of 1887, which opened Indian reservations up to white settlers, resulted in tribes losing 90 million acres of land and caused ‘checkerboarding,’ or alternating and interspersed tracts of land under tribal and state jurisdictions. Checkerboarding would later contribute to confusion over which agencies have authority over crime, as well as create opportunities for criminals to evade Indian police by fleeing from their jurisdictions.

The number of Indian police dropped from 900 in 1880 to 217 in 1925, and by 1948, the federal budget allowed for only 45 funded Indian police officers (Luna-Firebaugh, Reference Luna-Firebaugh2007). The government responded with Public Law 83–280 (PL 280), which in 1953 transferred criminal jurisdiction from the federal government to California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Wisconsin, and later Alaska. PL 280 enabled other states to unilaterally assert jurisdiction over the reservations within their borders. Law enforcement issues continued unabated as lack of political constraints meant these states rarely did anything (Dimitrova-Grajzl et al., Reference Dimitrova-Grajzl, Grajzl and Guse2014). The tribes and states not included under PL 280 continued to receive little federal law enforcement assistance.

In 1963 over one hundred Indian police officers were added to the BIA payroll; in 1969 the Indian Police Academy was established. As the tide shifted toward self-determination, tribes began to take over certain enforcement functions from the BIA with the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (also known as PL 93–638) and the Self-Governance Act of 1994 (Luna-Firebaugh, Reference Luna-Firebaugh2007).

3. Current policing regimes in Indian country

Currently, Indian country consists of 56 million acres of land owned by Indian communities or the federal government in trust in the United States, mostly located west of the Mississippi. The largest of the 574 federally recognized tribes is the Navajo Nation, with 330,000 citizens and an area of 27 thousand square miles in parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. There are over two hundred tribal police departments.

The three basic types of policing arrangements in Indian country are federal, state, and tribal policing (see Table 1). Under federal (or BIA) policing, police officers assigned to specific tribal lands are BIA employees who are part of the BIA law enforcement division. BIA officers are responsible for investigations, with local BIA supervisors appointing commanding officers who then manage the patrol division. Thus, there is no formal role for tribal communities in the BIA organizational structure. BIA police have federal police union protections and their funding is determined by Congress.

Table 1. Three types of policing arrangements on American Indian reservations

a Each regime is an archetype, as any given reservation involves some extent of policing by reach regime, though as a matter of statute and law, the regimes are considered distinct.

Significantly, there is a general community-based program within the BIA policing structure. The DOJ's COPS Office has a tribal policing initiative to facilitate community policing on reservations. One of its efforts is its collaboration with Minnesota tribes to address the opioid crisis, which affects American Indians disproportionately. Through a $1.4 million grant from the COPS Office, the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) established the Minnesota Anti-Heroin Task Force to help local agencies in Indian country disrupt the flow of heroin into Minnesota and investigate overdose-related deaths. Since its formation in February 2018, the BCA has entered into cooperative arrangements with 39 agencies, including six of Minnesota's sovereign nations.Footnote 3 Other programs include the DOJ's Tribal Access Program for National Crime Information, which disbursed $1.5 million in 2019 to provide better information access (and technology access) to tribes to better report and access national crime databases.Footnote 4

States generally have jurisdiction over Indian-country crimes if the victim and offender are both non-Indians. The exceptions are federal crimes, where the BIA has authority. PL 280 originated during the federal government's tribal termination era, which hoped to reduce federal expenditures by eliminating reservation legal status. Its defining feature is that it places a reservation under the rules of the state police. In PL 280 mandatory jurisdictions, the tribes have no say in whether the state has ultimate authority over-policing. In PL optional jurisdictions, the tribes exercise a choice to remain part of the state's policing institutions. Though the rationale for PL 280 was to prevent ‘lawlessness’ in Indian country, it is best understood as part of the federal government's effort to replace separatist policies with ones of assimilation and destruction of Indian institutions that characterized much of federal policy since the 1930s (Hall, Reference Hall1989). It has failed to do so because of inadequate funding for reservation law enforcement and lack of incentive to police reservations (Dimitrova-Grajzl et al., Reference Dimitrova-Grajzl, Grajzl and Guse2014; Goldberg and Valdez, Reference Goldberg and Valdez2008). President Nixon ended the termination policy in 1970. However, PL 280 continued even as the United States attempted to reform relations in Indian country. Nominally, PL 280 was designed to address lawlessness,

Under tribal policing based on PL 93–638, tribes govern their police force: the tribal government decides the rules governing its police force, as well as hires and fires police. Tribal policing is funded in several ways: by the federal and tribal governments, by block grants from the federal government, or by the tribes themselves. Tribes that fund their own police under PL 638 have the greatest degree of autonomy, though fewer than five reservations do so (Goldberg and Valdez, Reference Goldberg and Valdez2008). Generally speaking, tribal policing comes closest to the realization of the polycentric vision of local policing, as the governance unit with primary authority - in this case, the tribe – is more closely linked (as far as local accountability and control are concerned) to those who use policing services than BIA or state policing.

4. Ostrom-compliant policing

The replacement of traditional policing by federal police was part of a broader consolidationist theme in the development of American policing from the time the early metropolitan police departments replaced night- and day-watches (volunteer policing) starting in the 1830s. Consolidation continued gradually until nearly every major municipality had a formal police department by the turn of the 20th century. Subsequently, the consolidationists' arguments found some support in research by Wilson (Reference Wilson1978), whose research on police bureaucracies found that centralization of policing services is acceptable given the right training.

Research on community policing in the 1970s found that neighborhood policing (small and medium-sized departments) is more effective in providing services: victimization rates are lower, police response times faster, and citizen evaluations more favorable than in larger police agencies (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Parks and Whitaker1973). Ostrom and Whitaker (Reference Ostrom and Whitaker1974) found neighborhood policing performed better than municipal policing even when neighborhood departments commanded a small fraction of the per capita resources of the metropolitan department.

Subsequently, Elinor Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990, Reference Ostrom2005) discovered eight design principles for successful self-governance. Though initially developed by consideration of resource commons, these design principles have been used to understand self-governance more broadly and to explain and understand collective outcomes as a result of individual decisions, with emphasis on the significance of rules (or institutions) as shaping these outcomes (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2011). These principles include the following:

-

P1. Jurisdictional clarity

-

P2. Fit of rules and services to local conditions

-

P3. Participatory decision-making

-

P4. Community monitoring

-

P5. Graduated sanctions

-

P6. Conflict resolution mechanisms

-

P7. Recognition of community rights to organize collectively

-

P8. Nesting within larger networks

In what follows, we adapt each design principle to policing. A policing regime that satisfies each is ‘Ostrom-Compliant.’ Thus, a policing organization at any level can implement what it calls community policing, but it may or may not be Ostrom-Compliant. In the discussion that follows, we link the design principles to each policing regime, as well as derive implications for how each type of policing regime aligns with each of the design principles. Generally speaking, the idea is that policing services will improve when they perform better on each of the dimensions, and that those that come closest to Ostrom-Compliant Policing will have the highest quality of policing services.

The first feature of Ostrom Compliance is clear jurisdictions for police (P1). Polycentrists prioritize multiple jurisdictions providing police services, though the success of a police force at any level (local, state, federal) in providing services depends to an extent clear authority in specific areas. Jurisdictional ambiguity can result in police shirking on their core functions and reduce citizens' ability to link budgets to police performance.

Police processes and procedures for police patrols should also reflect local demands and fit with local conditions (P2). The conventional public finance model of public services presumes that citizen mobility increases the dynamic fit between services provided and community demands (Buchanan and Goetz, Reference Buchanan and Goetz1972). One reason why policing at smaller scales is considered desirable is police need to understand their neighborhood, get to know people, and earn their trust to effectively serve neighborhoods (Duck, Reference Duck2015).

Citizen participation in changes in rules governing police is necessary for the rules to reflect changing priorities of communities (P3). One reason to encourage participation is because it contributes to trust in those institutions (Tyler, Reference Tyler2003). Citizen participation in rules, such as through a referendum on police reform, is also presumed to increase the chances that the rules governing policing reflect citizen preferences.

Communities require mechanisms to monitor police (P4). Police quality and performance are not technical issues that can be assessed apart from citizen evaluation (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1973). Monitoring through citizen evaluations is necessary to know whether citizens are satisfied with police services and their experience with police (Bayley, Reference Bayley1994).

The presence of graduated sanctions for violations of rules for both police who violate rules and with police as they make decisions about arrests (P5). Police inevitably violate processes and procedures. Issues arise when sanctions are too severe or too lenient. The ability to enforce rules is often obstructed by police unions, which undermine the ability of police administrators to sanction officers (Fegley, Reference Fegley2020). Police unions, even with the implementation of community policing, could undermine the ability to impose appropriate sanctions on police and hence undermine the quality of policing services. On the other hand, police discretion is also inevitable, and greater ability for police to use discretion in the arrest decision can improve policing outcomes in communities (Moskos, Reference Moskos2009). In Ostromian language, discretion enables graduated sanctions by allowing police to mete out more appropriate punishment.

Besides graduated sanctions, the quality of policing is expected to depend on the presence of low-cost channels to resolve disputes between policing and citizens (P6). For individuals, holding police accountable can entail high legal costs and be time-consuming, as delays in the legal system often mean it takes years to resolve conflicts. The emergence of more effective and rapid ways to address disputes arising from citizen-police interactions is critical for communities to hold police accountable. Smaller departments may have more opportunities for police officers to get to know people or for citizens to get face time with the police chief, thereby building trust in policing institutions (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Parks and Whitaker1973: 428). Since many complaints received by police departments are about officers' behaviors that do not violate policy and therefore are not subject to official sanction, having an informal means for citizens to voice concerns with the police can increase trust and cooperation with the police (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, La Vigne, Jannetta and Fontaine2019).

Design principle P7 is community autonomy to govern policing. In a polycentric policing system, citizens at lower levels require autonomy from higher levels of authority to decide on the rules governing their police through a deliberative process. From this perspective, polycentrism is less a question of decentralization versus centralization than of meaningful autonomy of local units to make decisions about their community (Wagner, Reference Wagner2005).

The final design principle is nested governance (P8). In Ostrom's framework, this principle requires preserving community autonomy from higher levels of government within a nested system (Kashwan and Holahan, Reference Kashwan and Holahan2014). For policing, this reflected explicitly in community autonomy over-policing. Thus, given that the polycentric enterprise provides for community autonomy, information flows within the network influence the quality of policing. Police bureaus are a layer of bureaucracy in a polycentric system with several layers, and so autonomy of the most local levels is critical, as is the accountability of police to citizens. Since police operate at multiple levels – city or town, county, state, and federal – the quality of information flow among these levels of government, and the strength of networks of association, are expected to influence the quality of policing.

Though not a design principle, the Ostromian framework has long considered trustworthiness and institutions that reward honest behavior as contributing to more successful collective action (Ostrom and Ahn, Reference Ostrom, Ahn, Svendsen and Svendsen2009). In application to policing, racial differences in trust can influence whether citizens are willing to cooperate with the police (Tyler, Reference Tyler2005) and reforms that improve trust can encourage voluntary compliance with law and cooperation in fighting crime (Tyler, Reference Tyler2011). Trust is expected to influence community participation in rule change (by overcoming collective action), monitoring of police (as such monitoring requires some degree of trust in the system to participate), and dispute resolution, which depends in part on trust in institutions. Trust is also likely to influence relations among policing units in a nested system. Our expectation, which we do not explicitly consider here and note for future research, is that policing regimes that come closer to Ostrom-Compliant Policing will generate more trust in police.

5. Assessing Ostrom-compliant policing on reservations

5.1 Federal policing

BIA policing is to an extent centralized. The COPS program attempts to implement community policing by enabling tribes more control over policing (thus achieving something of a hybrid system of policing). Here, we consider how some of the features of BIA policing undermine prospects for implementation of community policing via COPS. The BIA has moderately clear jurisdictions (P1), though the borders of a nation are not always clear, as the 2020 Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma shows. For a century, people assumed there were no reservations in Oklahoma. However, McGirt held that there are reservations, which has led to jurisdictional chaos by calling into question much of federal policing and prosecutorial authority in Eastern Oklahoma (Reference CrepelleCrepelle forthcoming). On this margin, we expect the institutional features of BIA policing to improve policing services, as the jurisdictional fit is relatively clear.

Fit with local conditions (P2) is an issue since BIA command structures are such that supervisors and agents are not necessarily in touch with local realities, though some efforts have been made to improve fit. Kettl (Reference Kettl2014) considers several reforms along these lines. In mid-2008, residents of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in the Dakotas had a violent crime rate six times higher than the national average. Residents had such little confidence in the BIA that they were not even reporting crimes. The BIA worked out metrics for success with the Office of Management and Budget. The Department of Interior focused on four reservations with a goal of a 5% reduction in violent crime. The reservations – the Sioux's Standing Rock Reservation, the Chippewa Cree Tribe's Rocky Boy Reservation in Montana, the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico, and the Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes' Wind River Reservation in Wyoming – achieved a 35% crime reduction. Kettl claims it was because the BIA associate director for field operations, Charles Addington, directed the agency to collect data on crime – which were then used to redeploy police using predictive-policing methods to preempt crime – and to work with tribal leaders to establish trust between the tribes and the federal government. The federal government has also in some instances responded to gaps in state policing. For example, the Yakima Nation pleaded for federal help when the Washington State Patrol decided to stop policing the reservation due to the confusing checkerboard of the jurisdiction (Hudetz, Reference Hudetz2020). Accordingly, on this margin, our expectation is that that the quality of policing will decline, given the lack of clear accountability.

There are few opportunities for tribal citizens to participate in rule change under BIA policing (P3). Part of the reason is decision-making is governed by Congress. Thus, links from the tribe to meaningful change would go through the highest levels of government, where tribal influence is questionable at best. Institutional studies of tribal-federal relations have generally portrayed the federal government as largely unresponsive to tribal demands (McChesney, Reference McChesney1990). Tribes sometimes have relationships with the federal government that provide them with greater influence. Since BIA agents are employed by the federal government, tribes have no direct control over the BIA administration. Our expectation is therefore declining the quality of policing services.

Community monitoring is not clearly provided for by the BIA (P4), though citizens have some opportunity to report concerning behavior by BIA police. To our knowledge, there is no ongoing survey of citizen satisfaction with policing in BIA jurisdictions. Absent such mechanisms, our expectation is that the quality of policing will decline.

BIA police are sanctioned by federal rules. They also have federal union protections. This all but ensures that sanctions will be challenging, let alone graduated sanctions (P5). The issues with police accountability in the US apply both to federal and state police, and both suggest a lower quality of policing services.

Regarding P6, BIA falls short – dispute resolution is costly and time-consuming. The BIA has an internal-affairs division that investigates complaints against BIA officers and the Office of the Inspector General serves as a watchdog of the BIA and other agencies in the Department of the Interior. Since these disputes involve a federal agency, they are typically costly and time-consuming. Dispute resolution with municipal police departments is notoriously time-consuming, and tribal policing is far from immune to these same sorts of bureaucratic challenges. Absent such processes, our expectation is that the quality of policing services will suffer.

Regarding P7, community autonomy, BIA policing is largely inconsistent with the autonomy of tribes. The background for considering community autonomy is that tribal sovereignty is subject to the plenary power of Congress to take it away, as the Supreme Court holds. Subjugation is the defining feature of this public law legal regime (Blackhawk, Reference Blackhawk2018). Through legislation and regulations, the BIA denies tribal sovereignty. A perhaps more fundamental limitation involves authority over crimes committed by non-Indians. The federal government has a trust responsibility to the tribes, but in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978) the Supreme Court said tribes do not have criminal jurisdiction over non-Indian perpetrators. Thus, tribes have no authority to prosecute non-Indian offenders even if the crimes occur in Indian country; the result is a sort of immunity that diminishes safety. Though autonomy is not inherently going to result in improvements in outcomes, the expectation of polycentrists is that falling short on this margin will lower the quality of policing services.

Regarding P8, for each system, information flows between agencies are an issue. Several DOJ projects attempt to provide tribes with funds that would upgrade their systems to improve information flows. Such improvements can enable predictive policing, which is associated with reduced crime rates. Sovereign police departments also require information flows, as they benefit from access to national crime databases. From this perspective, much of federal policing could be top-down, including the COPS system, and hence inconsistent with sovereignty, even though there are efforts to improve information flows from tribes to government. Hence, our expectation is that on this margin, BIA policing outcomes will suffer.

5.2 State policing

PL 280 jurisdictions are reasonably clear (P1) in that state police have jurisdiction over all crimes against all people on all land (BIA does not have jurisdiction off reservation, which is a state power). For PL 280 jurisdictions, issues arise over whether laws are civil or criminal, and tribal citizens may be exempt from certain crimes, including crimes where the tribes assert sovereignty, though the types of crimes in this category are relatively minor and only come up in rare circumstances. Some municipal police departments have moved more explicitly toward community policing, as we discuss in the Muckleshoot example in Section 6, though even then, the extent to which institutions are a fit with local communities (P2) are questionable in PL 280 jurisdictions, as an ongoing concern in these areas is that the police are not responsive to tribal demands. Thus, while P1 suggests PL 280 policing may farewell (given jurisdictional clarity), the lack of fit with local communities is expected to reduce the quality of policing services.

Tribal citizens are also citizens of the state where their reservation is located, so they have opportunities to participate in the governance of reservation policing (P3). PL 280 policing is governed by municipal rules and local policing policies, which typically are subject to change by mayors and city councils, over whom tribal members have little influence. There are exceptions, as some tribes have good relations with nontribal governments. But in general, our expectation is that on this margin, the quality of policing will decline as a result of limited opportunities to participate directly in the governance of police.

Nor are there clear opportunities to monitor police (P4), though some of the community policing initiatives discussed above attempt to provide some progress in this area. State statutes and police unions reduce the ability of police administrators to impose graduated sanctions (P5) (which can include verbal and written reprimands, mandated training, suspension without pay, and termination) by giving officers the ability to appeal disciplinary decisions to arbitrators, who often reverse those decisions (Fegley, Reference Fegley2020; Rushin, Reference Rushin2019). Together, our expectation is that weakness on both of these margins will result in lower-quality policing.

Regarding P6, resolution of conflict with police is costly, and litigious. Unions reduce the ability to resolve conflicts, as they insulate police. Compared to reservation policing, both state and federal policing are expected to have lower-quality policing because of the higher costs of dispute resolution.

Like BIA policing, community autonomy is limited under PL 280, which is predicated on the view that public administration works best through assimilating Indians into state institutions (P7). Each of the limits to accountability that impair the ability of municipal police administrators to punish deviant behavior on their force also affects their ability to do so when the police kill residents of Indian reservations. One of the challenges to the nested system of governance (P8) is that there are often unclear lines of communication between tribes and police. In addition, the nature of PL 280 involves limiting tribal autonomy over-policing. As a consequence, P7 and P8 imply lower-quality policing under PL 280 arrangements.

5.3 Tribal policing

Jurisdictional clarity (P1) is a severe challenge to tribal policing, which severely limits tribal police to operate even with a 638 contract (Reference CrepelleCrepelle forthcoming). Tribes can only assert criminal jurisdiction over Indians; they can only prosecute non-Indians under the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act. When a non-Indian victimizes an Indian within Indian country, the federal government has criminal jurisdiction. If a non-Indian victimizes a non-Indian in Indian country, the state has criminal jurisdiction. According to a report by the Indian Law and Order Commission, the situation on reservations is a jurisdictional maze and the antithesis of effective government (Eid, Reference Eid2013). Since the authority to arrest anyone is typically tied to prosecutorial power, tribal police cannot arrest non-Indians unless the tribal police have federal authorization through a special law enforcement commission or a cross-deputization agreement with the state or local government. Basing arrest authority on Indian status requires a determination of Indian status, and different federal courts use different tests to determine who is an Indian, which can take months (Crepelle, Reference Crepelle2018). Nor are the boundaries of Indian reservations always clear, as revealed by the McGirt decision. Jurisdictional uncertainty creates incentives and opportunities for criminals to cross reservation borders in order to avoid justice. For example, non-Indians attempt to dodge tribal jurisdiction by asserting they committed a battery against an acquaintance rather than an intimate partner. Since US Attorneys often ignore domestic violence cases, non-Indians were essentially free to abuse their Indian wives and girlfriends (Crepelle, Reference Crepelle2020).

Tribal policing has the clearest fit with local conditions, as tribes have the most control over their police force and the rules governing police (P2). However, fit with local conditions can only apply to a narrow range of crimes, given jurisdictional rules limit tribal authority over many kinds of crimes. Thus, while lack of jurisdictional clarify implies a lower quality of policing services even under sovereign tribal contracting to provide policing services, fit with local conditions is a margin where we expect improvements in policing.

Both P3 and P4 imply higher quality of policing services. Under tribal policing, the tribes determine the rules governing police, and so there are opportunities to participate in rule change (P3). Since tribal governments vary substantially, the extent to which tribal governments are responsive in providing opportunities for rule change will vary locally, though in general there is more local control over rules – most tribes are small, and so local control over rules means that the influence of any given voter will be much greater than in a municipality. However, the federal government, by asserting substantial jurisdictional authority over tribes, ensures that many rules that affect crime on reservations are beyond the scope of tribal self-governance. PL 638 policing provides greater tribal autonomy (P4). In certain realms, tribes have meaningful autonomy in making laws and staffing their police departments.

Regarding community monitoring (P5), we are unaware of any tribes with ongoing citizen surveys conducted to assess their police force (though with several hundred tribes, it is certain that many, if not most, have in place some mechanisms to monitor tribal policing). The available evidence from interviews with members of tribes that opted into tribal policing contracts suggests that citizens find tribal police more accessible, and are better able to communicate their concerns to them, than under BIA or municipal policing (Wakeling et al., Reference Wakeling, Jorgensen, Michaelson and Begay2001). On this margin, our expectation is improvements in policing services compared to the other policing regimes.

Graduated sanctions (P6) and low-cost dispute resolution (P7) are possible on reservations, given union constraints are not as binding. Similar issues that undermine information flows for BIA and state policing affect tribal policing (P8) and may be exacerbated given the dependence of tribes on the federal government for assistance in policing given the jurisdictional ambiguities outline above. Thus, on these dimensions, our expectation is that the institutional rules provide some advantages for tribes that assume greater policing responsibilities, though lack of information flows as well as ongoing dependence on the federal government imply a lower quality of policing services Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of policing regimes on the design principles for community policing

6. Crime and punishment on reservations

6.1 Does consolidation fail worse?

Ultimately, a key question is what explains the quality of policing services on Indian reservations. Our expectation is that Ostrom Compliance will improve policing outcomes. The discussion above indicates how well each regime fares on each dimension, with resultant implications for policing. But there are government failures associated with polycentric policing. Here, we consider some of these potential challenges, in particular, what Boettke et al. (Reference Boettke, Coyne and Leeson2011) refer to as that argument that ‘consolidation fails worse’ than polycentrism.

Boettke et al. (Reference Boettke, Coyne and Leeson2011) explain contend that the idea consolidation fails worse (than polycentrism) is not entirely satisfactory unless we can explain why consolidation fails worse. The reason why consolidation fails worse is precisely because it is not Ostrom-Compliant. Thus, we would expect – for reasons notes – that tribal policing will not fail as badly as the other regimes, though our expectation is that each is expected to contribute to poor policing outcomes.

This is a significant distinction since there it is often presumed that tribal policing is superior, or that BIA policing, with the right modifications, can improve dramatically policing outcomes. Our contention is that the extent to which each works depends on Ostrom Compliance, and that none of the three major regimes are in general Ostrom-Compliant. Still, what is clear is that tribal policing comes closest to Ostrom-Compliant Policing and so our expectation is that tribal policing will fare better than the others in terms of the quality of policing services, as well as in overall crime rates. In what follows, we consider the available evidence of policing outcomes across each regime, as well as the available crime data on policing, though for reasons we note, the use of such data in analyzing Indian country policing comes with a number of caveats.

6.2 BIA policing and the quiet crisis

The available evidence suggests that BIA is not providing the policing services needed by tribal communities. One important issue is funding. In 2003 a US Civil Rights Commission report referred to low spending on reservations as ‘the quiet crisis.’ In 2018, a decade and a half after the commission publicized the quiet crisis, it again decried the low levels of funding, this time with the theme of ‘broken promises’ (Office of Civil Rights Evaluation, 2018). In response, the DOJ in October 2019 announced $273.5 million in grants to support crime reduction on American Indian reservations – or around half a million per reservation, on average.Footnote 5

BIA policing also promises false hope to many reservations. Tribes are continually confronted with vulnerability to shirking by the federal government as policing on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Montana during the COVID-19 pandemic shows. The BIA assigns only a few federal law enforcement officers in a nation of 690 square miles. According to the BIA, there should be at least 19 law enforcement officers on the reservation, but an average of six had been assigned in the years before the pandemic (with sometimes only one officer on duty), leading the tribe to sue the BIA (Aadland, Reference Aadland2020). The jails in many communities are not even staffed because they are not used. Once COVID-19 hit in April 2020, the BIA decided to only make arrests for violent crimes (murder, rape, and serious assaults). The lack of policing led tribal leaders to institute tribal policing. The result was the formation of the Northern Cheyenne People's Camp, with policing provided by the Northern Cheyenne Traditional Military Societies. The military societies initially ran checkpoints, halted vehicles, and asked drivers from outside Montana to pass without stopping; they then expanded their authority to include policing the tribe with the aid of traditional punishments, including whippings with a chokecherry switch. Waylon Rogers, a member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribal Council and supporter of the Northern Cheyenne People's Camp, said, ‘This is effectively a lawless land. People know that there's no consequences. Crimes that were taboo are now normal, and they feel like some kind of invisibility for them’ (Hamby, Reference Hamby2020).

The Cheyenne addressed their challenges without relying on the federal government, which provided neither supplies nor wages. It was also extralegal, and perhaps illegal given the whippings. In this regard, it is reminiscent of Ellickson's (Reference Ellickson1991) ethnography of how ranchers settle disputes in California, which included as the most severe penalty castration of wayward bulls owned by ranchers who continually failed to control their cattle. Castrating a bull was not a legal way to resolve disputes and was not often used. Thus, it would be interesting in learning more about how the Northern Cheyenne policing worked in practice, and whether these tactics were used, or if the threat was enough to deter certain types of behavior.

6.3 State policing: an improvement?

Policing by the states is more decentralized than the BIA, which has led some to contend that it is effective. Anderson and Parker (Reference Anderson, Parker and Klick2017) suggest that decentralization of policing, in particular moving from federal to state control, improved certain aspects of civil law on reservations. However, the most thorough studies of the effect of PL 280 on crime find that it has been ineffective (Goldberg and Valdez, Reference Goldberg and Valdez2008).

One noteworthy attempt at community policing under PL 280 is the Muckleshoot Tribe of King County, Washington, which has its own police department made up entirely of King County Sheriff's Office (KCSO) deputies, which was established by a contract in 1999 under PL 280 when the tribal council decided to form an independent, nontribal law enforcement agency using federal grant funds.Footnote 6 The tribal police force seeks to engage in proactive, problem-solving policing and to develop interpersonal relations and build trust through communicating with the Law and Order Committee of the Muckleshoot Tribal Council. According to KCSO, the relationship allows for operational efficiencies; for example, the KCSO provides support for investigations and for a bomb, SWAT, air-support, and 911 functions that the tribe alone could not support (Sotebeer, Reference Sotebeer2013). To date, there has not been any specific analysis of every effort to implement community policing along these lines on PL 280 reservations, which is an important area for future research.

6.4 The case for tribal policing

Wakeling et al. (Reference Wakeling, Jorgensen, Michaelson and Begay2001) provide several case studies of reservation policing, which we briefly summarize. The Tohono O'odham Nation in Arizona (at the time of their study, the Nation had 14,000 members living on 2.9 million acres of land) signed a 638 contract in 1982. Despite advantages from a strong tribal culture and direct tribal control of the police department, the tribal police had poor record-keeping, reducing the ability to hold officers accountable for negligence. What emerged was a mismatch between community priorities and perceptions of the role of police in community life – police prioritized countering bootleggers and drug smugglers rather than low-level problems that had previously been settled at the village or district level. As a result, citizens established a quasi-official ranger program, administered at the district level, that ended up being more responsive to citizens' demands than the police department.

The second case study is the Gila River Indian Community, located immediately south of Phoenix, Arizona, with around 12,000 enrolled members at the time of the study. Proximity to Phoenix led to many ‘urban’ problems in the community, including youth gangs and some of the highest rates of crime in Indian country. In the 1970s, the tribe created two additional entities to improve policing because they found the BIA ineffective, including rangers (who policed the vast off-road areas) and reserves (who served as backups to BIA police). In the mid-1990s, the tribe assigned a commission to begin the process of a 638 contract, but progress was hindered by a lack of administrative assistance from the tribal government and unresolved debates over the direction and leadership of the 638 departments. The research team found records in disarray during this time, and problems resulting from a series of short-term BIA captains.

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes live in the Flathead Indian Reservation in northwestern Montana, with their initial 22 million acres from the early 1800s mostly lost to the Hell Gate Treaty of 1855 to homesteaders but had only around 4,100 tribal members and 18,000 non-Indians living on the reservation by the time of the study, thus creating substantial management challenges given the large territory. By the mid-1990s, the BIA had very little presence and the tribe was operating effectively under a self-governance contract. As of 1996–1998, the tribe had a police chief who served for 25 years, with 17 sworn positions. Despite having a well-run department, the tribe was unable to take advantage of many opportunities to improve institutional linkages between police and prosecutors. Another challenge was that after a retrocession agreement was signed that returned authority over certain misdemeanors back to the tribes, citizens made more demands on the police, though the increase in demand reflected citizens' trust in police.

The fourth reservation Wakeling and colleagues visited was the Three Affiliated Tribes (the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) in the Fort Berthold Reservation in west-central North Dakota, which had approximately 4,000 members living on the reservation in the mid-1990s on about a million acres of mostly field and prairies with a modest gambling enterprise. This was at the time a BIA-managed split department with BIA officers along with tribal officers funded through COPS grants. COPS officers had a clearer role in policing, and they were effective in their jobs, but there was little correspondence between the department's conception of its role in the community and the community's perception of the role, with tribal members focusing the desire for police to employ methods based on tribal values and culture, to preserve and extend tribal values. Interviewees brought up the Black Mouth Society – an association in which older, courageous males played a central role in maintaining order during pre-and early reservation life, where behavior was enforced simply by the threat that people would tell the Black Mouths. Federal officers, who liked their federal pensions and job security, described their mission mostly in conventional law and order terms and did not see 638 as an opportunity to redefine the role of police and community life.

These case studies further illustrate challenges to Ostrom-Compliant Policing. Even with 638 contracts, there remain substantial challenges on reservations, including what could be termed government failures with tribal policing (some of which reflect policing culture). Or as we describe it, these cases suggest that consolidation through BIA policing fails worse and polycentrism is an improvement.

6.5 What tribal crime data say (and don't say)

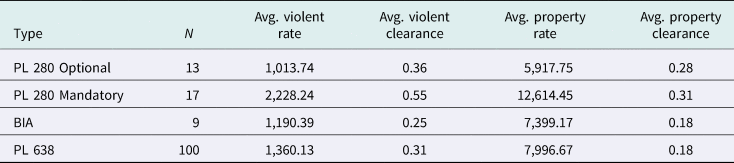

We collected available data on violent and property crimes and their clearance rates, from 2006 to 2019. According to the FBI, an offense is ‘cleared’ either by arrest or by ‘exceptional means,’ under which there is sufficient evidence to arrest a suspect and authorities know the suspect's location but something outside of the authorities' control prevents them from arresting the suspect, such as the suspect's death.Footnote 7 Clearance rates are the average number of crimes cleared/average number of crimes reported. One interpretation of clearance rates is that higher rates mean that policing is more effective, as there are more charges associated with crimes. Table 3 presents average violent crime and property crimes are reported as incidents per 100,000 population for four categories of policing: PL 280 optional, PL 280 mandatory, BIA, and PL 638. The data are presented as arrests per 100,000 because that is how they are presented in the FBI crime database. These data are presented this way for all communities, including those with small populations (as most tribes have), to provide a basis for comparison across all tribes.

Table 3. Crime by reservation policing jurisdiction

Source: FBI UCR and US Census Bureau American Community Survey.

There are important caveats with these data. First, there are years with zero cleared crimes followed by huge jumps, which may reflect an incoming police chief who wants to clear crimes from the books. Second, there are large outliers in the PL 280 data, with high crime rates that do not make much sense. Third, the BIA does not appear to report statistics as well as other reservations. Fourth, underreporting is an issue. Based on several DOJ and FBI reports, Indian victims often do not trust state or federal authorities and do not often report crimes, especially sexual assault (Crepelle, Reference Crepelle2016). One problem is that many Indian country residents find law enforcement pointless, as they do not expect that the authorities will help them (Crepelle, Reference Crepelle2020).

With these caveats in mind, the data in Table 3 show that rates of violent and property crime are higher on PL 280 mandatory jurisdictions (again, the rate per 100,000 is used so that the tribes are comparable). If the rationale was to prevent lawlessness, PL 280 has not been a success. BIA and PL 638 are comparable as far as average crimes, though the latter provides for greater sovereignty and hence would be desired from that perspective. Clearance rates are more challenging to determine, though the highest clearance rates are on PL 280 mandatory jurisdictions, which suggests that while state-mandated policing does not prevent lawlessness, there are more charges associated with arrests.

Our interpretation of this is that there is no obvious improvement with centralization, as BIA policing has many issues. However, there is some evidence that PL 638 is more effective than PL 280 policing, which aligns with previous research critical of PL 280. The data on clearance rates are indicative of the challenges in measuring successful policing, as they indicate that PL 280 may result in more charges associated with arrests. As far as an explanation, these data are consistent with our argument that regardless of the policing regime, Ostrom Compliance is currently frustrated on all tribal policing regimes. These barriers to meaningful community policing can explain why the crime rates on reservations remain high, even in those policing arrangements where tribal governments assert the greatest degree of sovereignty.

7. Conclusion

We introduced the concept of Ostrom-Compliant Policing, apply it to Indian country policing. We found that tribal policing is the most decentralized policing arrangement but that it is not Ostrom Compliant. Community opportunities to participate in the rules governing police, some semblance of autonomy, and opportunities to discipline police are all greater in tribes. However, jurisdictional complexity reduces the quality of policing services on tribal reservations. The COPS program administered by the BIA attempts community policing, though with such programs there remain few opportunities for tribes to participate in the rules governing the police, jurisdictional issues remain, and BIA police are by and largely unaccountable to tribal citizens or their rules.

The issues with policing on reservations have led to the question of whether institutions such as PL 280 are appropriate for 21st-century policing (Goldberg and Champagne, Reference Goldberg and Champagne2005). In theory, PL 280 could have all states implement community policing, but our analysis suggests that lack of accountability would be an issue. The example of the Muckleshoot Tribe, where tribal citizens appear to have real control over a police force, is promising, though for reasons noted, attaining Ostrom-Compliant Policing in any PL-280 jurisdiction remains challenging as a result of jurisdictional issues and an overall lack of opportunities for tribal citizens to participate in the governance of municipal policing regimes.

Studies of municipal policing have found that increases in federal funding undermine prospects for Ostromian policing (Boettke et al., Reference Boettke, Lemke and Palagashvili2016). In the summer of 2020, defunding police emerged as a significant issue. A legitimate concern in Indian country is insufficient funding for tribal policing. Our analysis suggests that even with increases in funding, Ostrom-Compliant Policing confronts substantial obstacles on American Indian reservations. To the extent tribes desire Ostromian policing, a realization of this vision requires changes in the rules of the game.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Center for Governance and Markets at the University of Pittsburgh, the Institute for Humane Studies, the Charles Koch Foundation, and the Campbell Fellows Program at the Hoover Institution. For useful conversations on policing in Indian country, we thank Eric Alston, Terry Anderson, Peter Boettke, Dominic Parker, Wendy Purnell, Peter Moskos, and participants in the “Campbell Fellows Research on Renewing Indigenous Economies” workshop hosted by the Hoover Institution, October 11-12, 2021. For insights into the Ostromian design principles we are grateful to Paul Dragos Aligica.