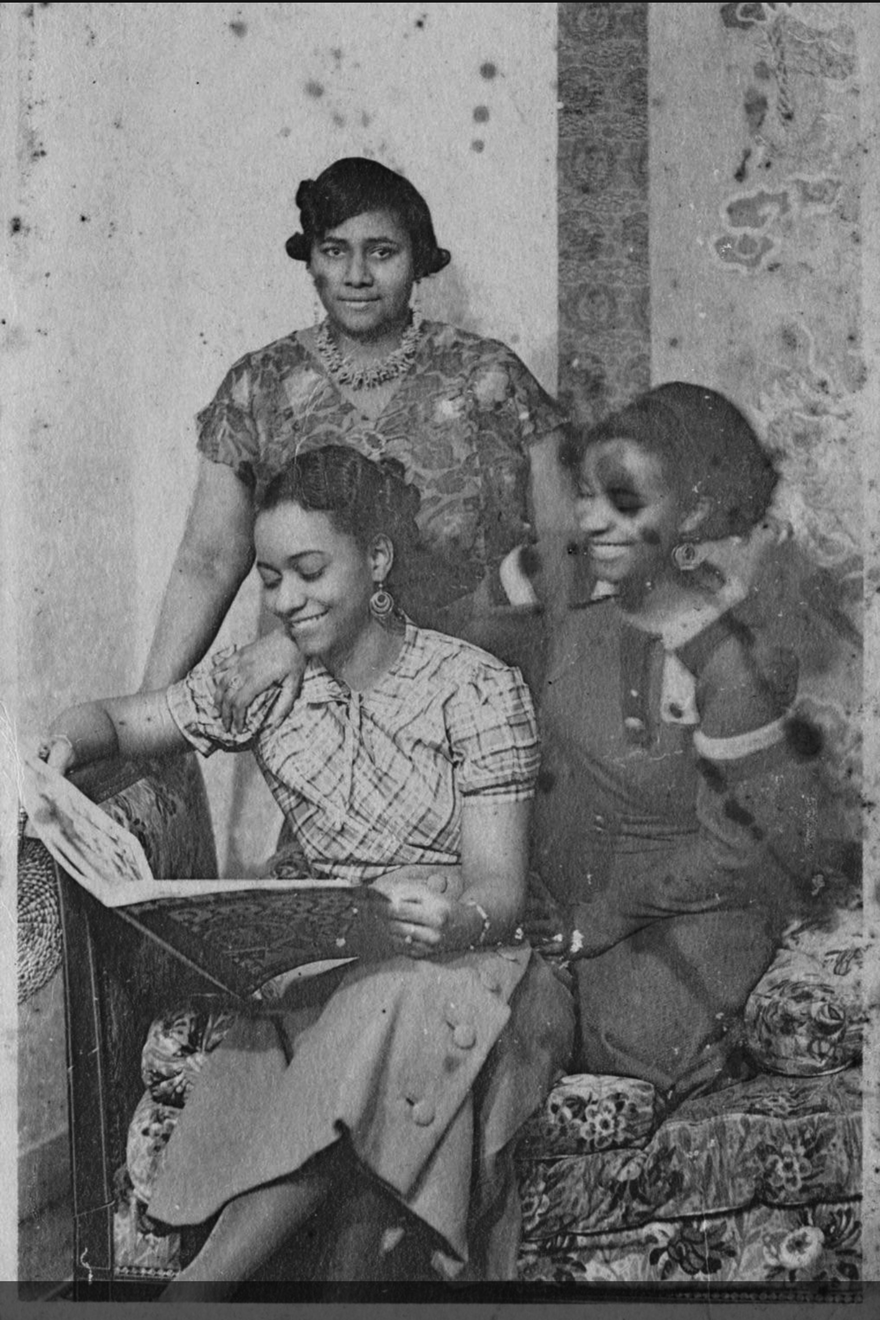

In July 2021, the weekly magazine of the French newspaper Le monde published a lavishly illustrated feature article on the Martinican intellectual, writer, translator, and editor Paulette Nardal, who is increasingly recognized as having played a central role in the international networks of black intellectual culture in the 1920s and 1930s (Hopquin). As the host, with her sisters Jane and Andrée, of an informal weekly salon in Clamart, a suburb of the French capital, and as the editor of the short-lived but influential bilingual journal La revue du monde noir (The Review of the Black World [1931–32]), Nardal served as a vital “intermédiaire culturel” (“cultural intermediary”; Fabre, “Autour de Maran” 170) between the many African American and anglophone Caribbean artists and writers who flocked to Paris between the world wars and their francophone African and Caribbean counterparts (fig. 1). The upsurge in French journalistic attention paid to these women “reconnues aujourd'hui comme défricheuses, à l'heure où des manifestants des deux rives de l'Atlantique crient que ‘les vies des Noirs comptent’” (“today recognized as trailblazers, at a moment when demonstrators on both sides of the Atlantic are shouting that ‘Black Lives Matter’”; Hopquin 35)Footnote 1 echoes the protests around racial justice and police violence that erupted not only in the United States but around the globe in 2020. But the coverage in Le monde, along with other recent profiles of Nardal in Libération (Bouniol) and La croix (Mormin-Chauvac) and a smattering of other publications—including a revelatory if roughly edited compilation of interviews with Nardal from the 1970s (Grollemund) and even (of course) a bande dessinée about the Nardal salon (Mormin-Chauvac and Macaron)—is also the product of an ongoing, at times agonized, transformation in the French discourse around race and public memory.

Fig. 1. Paulette (standing), Lucy (on the left), and Jane Nardal at their apartment in Clamart, outside Paris (19 October 1935). Nardal Collection, Collectivité Territoriale de Martinique, Archives de Martinique.

At the end of August 2021, the French government announced that the remains of the legendary African American performer Josephine Baker would be interred in the Panthéon, the temple in central Paris that serves as the resting place of the eighty politicians, writers, World War II resistance fighters, and scientists considered to be the symbolic “héros de la patrie” (“heroes of the fatherland”; Beaumont). Baker will be the first woman of African descent and only the sixth woman to be so honored.Footnote 2 Some have proposed that Paulette Nardal should be recognized the same way, and an online petition to have her remains moved to the Panthéon has been accumulating signatures (“Paulette Nardal”). As alluring as such a prospect may be, offering the promise of public recognition for the accomplishments of a woman who is arguably one of the great black francophone intellectuals of the twentieth century, it may be worth pausing to consider the stakes and pitfalls of canonization.

Without even confronting the portentous question of the Panthéon, there may be reasons to hesitate before retroactively placing Nardal at the center of the edifice of Négritude itself. The impulse among some commentators to redress the overshadowing or occlusion of Nardal in the intellectual genealogy of Négritude raises a host of questions. It is one matter to make the case that Paulette Nardal should be understood as, say, a “pioneer”—as Nardal notably described herself and her sister Jane (Hymans 36)—clearing uncharted territory for what would emerge years later under the name of Négritude, or a “precursor” (Achille 291; Sharpley-Whiting, “Clamart Salon” 58), a “predecessor” (Geiss 318), a “harbinger” (Goebel 81), a “catalyseur” (“catalyst”; Ngal 50), a “Marraine” (“Godmother”; Smith 68),Footnote 3 or even “la négritude en action” (“Négritude in action”; Zobel 88). It is another matter entirely to contend, following the influential work of scholars including T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting and Shireen Lewis, that—because they were integral in creating the cultural and intellectual atmosphere that fostered the emergence of Négritude years later, or because they formulated some of the ideas that were “si brillamment exposées et soutenues par la suite” (“so brilliantly exposed and sustained subsequently”; Grollemund 96) by Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and Léon-Gontran Damas—the Nardal sisters should be recognized as “women of Négritude”: members of, even the originators of, the movement, even if their pioneering activities preceded the coining of the term. This corrective impulse can result in an oddly vindictive tone and questionable assumptions about intellectual property in some of the recent journalistic celebration of the Nardals, such as the article in Le monde, which opens by invoking the advent of “la négritude, un courant de pensée qu'Aimé Césaire et Léopold Sédar Senghor s'approprieront, effaçant le rôle essential de celles qui en furent les piliers” (“Négritude, a current of thought that Aimé Césaire and Léopold Sédar Senghor would go on to appropriate, erasing the essential role of the women who were its pillars”; Hopquin 32).

While the idea of Négritude “continues to engender and animate debates on the continent and throughout the diaspora with the same stubborn difficulty as pan-Africanism” (Jaji xi; see also Monga), it has never been clear that the term can be taken to refer to a singular and coherent literary or political “movement” in the sense of a cohesive, sustained collective project. As many scholars have pointed out, the difficulty—and, perhaps, no small part of the persistent charm—of Négritude is that it can refer to realms as various as poetics, philosophy, and politics (Irele; Diagne). Even within these realms, there are marked divergences, such as the stylistic and formal differences in the oeuvres of Césaire, Senghor, and Damas, the three writers most readily identified with literary versions of Négritude (Condé; Noland). According to Souleymane Bachir Diagne's judicious summary, “Césaire and Damas have put more emphasis on the dimension of poetic revolt while Senghor has insisted more on articulating Négritude as a philosophical content, as ‘the sum total of the values of civilization of the Black World,’ thus implying that it is an ontology, an aesthetics, an epistemology, or a politics.” In the realm of state politics, historians have noted the stark strategic differences in the approaches to decolonization pursued by Césaire and Senghor during their long political careers in Martinique and Senegal, respectively (Wilder). Nor is it readily apparent how we might locate Négritude as a movement through a set of institutional spaces or networks, aside perhaps from the journal Présence africaine and the publishing house of the same name in Paris (which it seems reductive to characterize as an elaboration of Négritude alone, in any of the term's senses),Footnote 4 or the series of prominent international writers’ conferences and artistic festivals sponsored by the journal in the 1950s (Bonner; Edwards, “Césaire”; Julien), or the various diasporic artistic festivals hosted by states including Algeria, Nigeria, and Senegal starting in the 1960s (Harney; Murphy; Wane; Vincent; Apter).

There is no doubt that, as Sharpley-Whiting notes (Negritude Women 16–17), in recounting the origins of their work in the environment of interwar Paris, Césaire, Senghor, and Damas tended to downplay and even to dismiss the significance of the Nardal sisters both as intellectuals in their own right and as key facilitators of spaces of cultural exchange among African diasporic writers and intellectuals.Footnote 5 Only decades later did they begin to “déchanter” (“change their tune”), to adopt a memorable riff from the work of Frantz Fanon.Footnote 6 Only in 1966 did Senghor “remember” to celebrate Nardal's role, naming her a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur of the Republic of Senegal.Footnote 7 Only in 1970 did Damas recall the enormous impact of Nardal's work as a translator (30) and emphasize that La revue du monde noir, even if fifty years later it “donne l'impression actuelle d'avoir été une revue assagie, une revue bourgeoise, n'en était pas moins nécessaire; car il faut toujours tenir compte des circonstances et du temps dans lequel les choses se déroulent” (“gives the impression of having been a chastened and bourgeois journal, was no less necessary; for one must always take into account the circumstances and the time when things are taking place”; 29). Only in 1979 did Césaire, in a cultural festival in Fort-de-France, proclaim that “il convient aujourd'hui de rendre tout spécialement homage” (“today it is appropriate to render special tribute”) to Nardal's work on La revue du monde noir (qtd. in Fabre, “Du mouvement” 149).

In the 1970s, as she was beginning to receive this belated recognition from the “fathers” of Négritude, Paulette Nardal reflected on her relationship to them in a wounded tone: “Césaire et Senghor ne se sont pas conduits vis-à-vis de moi d'une façon très correcte, alors qu'ils m'avaient connue à Paris sur ces sujets et estimaient que ce n’était pas la peine de mentionner mon action” (“Césaire and Senghor did not conduct themselves toward me in a manner that was very correct, when they had known me in Paris working on these subjects and judged that there was no need to mention my activity”; Grollemund 106). This frames the injury as a matter of willful negligence—a failure to give credit where credit is due.

Her most explicit argument that she and her sister Jane should be recognized as originators of Négritude came in a 1963 letter to Jacques Hymans, in which Nardal wrote, “[J]e me dois d'ajouter que Senghor et Césaire ont repris ces idées lancées par nous et les ont exprimées avec plus d’éclat et de brio. Nous n’étions que des femmes, de véritables pionnières. Disons que nous leur avons ouvert la voie” (“I owe it to myself to add that Senghor and Césaire took these ideas launched by us and expressed them with more flash and brio. We were but women, real pioneers. Let's say that we blazed the trail for them”; Letter).Footnote 8 In another unpublished text written in 1966, however, she frames the relationship in a rather different manner: “Nos idées ont été reprises par Césaire et Senghor et dépassées et symbolisées par la notion de ‘négritude’” (“Our ideas were taken up by Césaire and Senghor and surpassed and symbolized by the notion of ‘Négritude’”; Note),Footnote 9 seeming to emphasize the key ideological intervention of Césaire's neologism. Even if the ideas were the same, as Kora Véron writes in her recent critical biography of Césaire, “la manière de la dire fera la différence” (“the way of saying it will make all the difference”; 74).

More disturbing is the possibility that the failure of Césaire and Senghor to acknowledge Nardal's contribution was not just a personal slight of an erstwhile intellectual colleague and elder but instead a constitutive blind spot in the founding imaginary of Négritude.Footnote 10 In a 1967 interview, Césaire vehemently denied having been influenced by the Nardals or La revue du monde noir, even as he admitted that the journal introduced him to Harlem Renaissance poets including Langston Hughes and Claude McKay and acknowledged that it signaled “un bouillonnement dans le petit monde nègre de Paris” (“a ferment in the little black Parisian world”; Ngal 52). Puzzled at the vehemence of Césaire's “refus d'influence” (“refusal of influence”), the critic M. a M. Ngal ultimately attributes it to the “caractère trop peu ‘révolutionnaire,’ pas assez ‘nègre’” (“insufficiently ‘revolutionary,’ not ‘nègre’ enough character”) of the Nardals’ salon and of La revue du monde noir (52). But even if it is partly rooted in a rejection of Paulette Nardal's seeming political quiescence—as an intellectual who, despite her calls for racial consciousness, never overtly criticized the French empire—the “mépris” (“contempt”) Ngal notes in Césaire's tone (52) suggests an element of misogyny in what Sharpley-Whiting pointedly calls the “masculinist genealogy” of Négritude (Negritude Women 14).

Césaire famously defined Négritude as “une prise de conscience concrète et non abstraite” (“a concrete rather than an abstract coming to consciousness”), which, in the context of interwar Paris, meant coming to reject the “atmosphère d'assimilation” (“atmosphere of assimilation”) that engulfed Caribbean and African students and intellectuals (“Interview” 91). But Nardal's coming to consciousness was “concrete” in precisely this sense: when she first arrived, she recalled, “Nous étions étudiantes, complètement assimilées. … C'est en France que j'ai pris conscience de ma différence” (“We were female students, completely assimilated. … It is in France that I became conscious of my difference”; Grollemund 26).

It was coming to terms with her status as a black woman that catalyzed this realization, as Nardal writes in her most famous essay, “Éveil de la conscience de race” (“Awakening of Race Consciousness”). This point is highlighted in all the recent scholarship on Nardal's work; as Jennifer Boittin puts it succinctly, “Black women in Paris argued that their race consciousness was made possible by their gender” (167; see also Sharpley-Whiting, Negritude Women 75–78; Edwards, Practice 122–25). The problem is that Nardal's mode of coming to consciousness differs from that of Césaire and the other male students of the Négritude generation: as Eve Gianoncelli argues, Nardal possesses “une expérience du racisme et des moyens de la théoriser à la fois antérieurs et différents par rapport à eux, en tant que femme” (“an experience of racism and the means of theorizing that experience, as a woman, at once anterior to and different from those of the male students”; 289). One might go so far as to say that Césaire's Négritude is defined by an inability to admit female experience as a concrete means of a racial coming to consciousness.

The other troubling possibility is that there may be a direct link between this constitutive blind spot and the ways that the various versions of a Négritude poetics that come to mind rely on figures of black femininity that are abstracted from history—from the “prière virile” (“virile prayer”) of Césaire's Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land), which positions its male speaker as “l'amant de cette unique people” (“the lover of this unique people”; Cahier 49; Notebook 37), to Senghor's exaltation of a purely symbolic “femme nue, femme noire” (“naked woman, black woman”; “Femme noire” 270; “Black Woman” 8).Footnote 11 Simply appointing Nardal to the Panthéon of Négritude risks foreclosing a feminist critique of Négritude both from the perspective of intellectual and social history and from the perspective of literary aesthetics.

These concerns have been on my mind recently because Gianoncelli and I have been working, with the generous assistance of the Nardal and Achille families,Footnote 12 on a bilingual edition of Paulette Nardal's interwar writings, which will be published by Nouvelles Editions Place in 2022. Following the model of Sharpley-Whiting's indispensable edition of Nardal's articles in La femme dans la cité, the journal Nardal founded in Martinique in 1945, we have attempted to gather and make available as complete a corpus of her work from the 1920s and 1930s as possible. The approximately three dozen less-well-known items we have collected will expand the Nardal bibliography substantially.

The revised bibliography will have an impact on our sense of Nardal's development as a writer, most strikingly at two points: with the publication of a significant number of articles in 1930–31 (the period between her first published writings in La dépêche africaine and her founding of La revue du monde noir) and with the addition of an important group of works in 1936, when her thinking was shaped by her role as a pivotal figure in coordinating efforts among black intellectuals in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States to influence international debate in the wake of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. As early as the summer of 1935, she helped to found the Comité de défense de l’Éthiopie (“Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia”) in Paris, which served as a sort of clearinghouse for these efforts. After Mussolini's troops crossed the border into Ethiopia in October 1935, much of Nardal's writing and political activity over the following year was aimed at bringing attention to the Ethiopians’ plight.

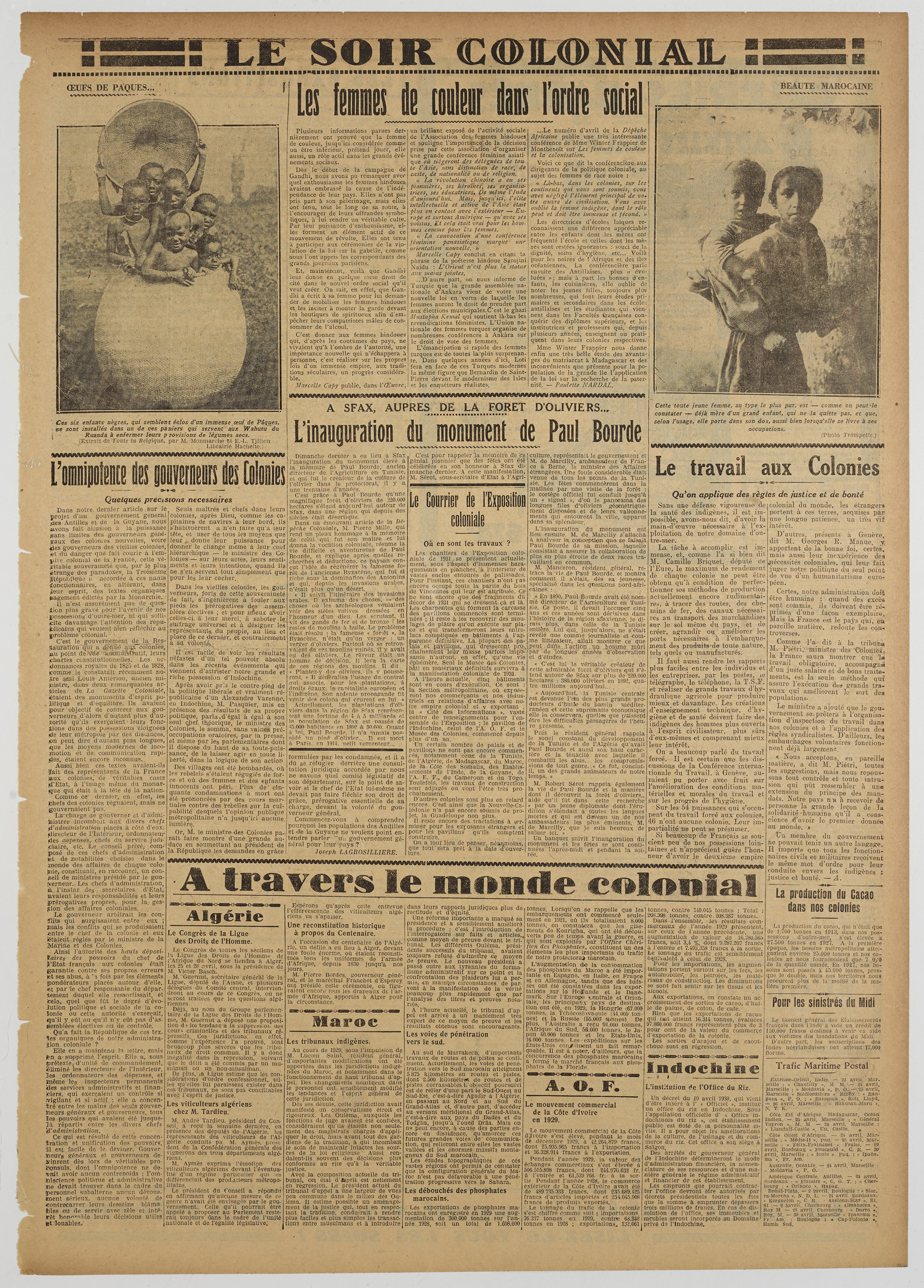

At the end of 1929, Nardal was hired as a journalist at the Parisian newspaper Le soir specifically to contribute to its weekly “Colonial Page,” which included articles on current events, politics, and culture across a surprisingly broad range of European colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean (fig. 2). She later credited the Martinican socialist legislator Joseph Lagrosillière (for whom Nardal went on to work as a parliamentary secretary) with introducing her to the journalist Ludovic-Oscar Frossard of Le soir, who, as she puts it, “m'a appris à fabriquer un article” (“taught me how to construct an article”; Grollemund 85). A smattering of her articles in Le soir have been considered recently by scholars such as Annette Joseph-Gabriel, who discusses one of the pieces in Nardal's four-part series on “L'Antillaise” (“The Antillean Woman”; 66–67), and Gianoncelli, who traces the shifts in Nardal's writing on feminism across a handful of articles (124–29). But there is much more material to be considered here: Nardal published nearly two dozen articles in Le soir in the spring of 1930.

Fig. 2. A page from Le soir colonial featuring Paulette Nardal's article “Les femmes de couleur dans l'ordre social.” Reproduced with the permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

It appears that Nardal was assigned a sort of apprentice duty at first: she penned a weekly overview of “actualités coloniales” (“colonial current affairs”). But this seemingly perfunctory assignment granted Nardal an arena in which to read widely across ostensibly disparate areas of print culture and to develop as a thinker by making unexpected connections. Her initial columns carry a subtitle indicating their purview (“Livres, revues, articles de presse” [“Books, Journals, Press Articles”]), but the categories change and accumulate over time as she gradually revises and expands the scope of materials she surveys, coming to include “actualités” as varied as art exhibitions, African dance, and “talkies” (Hollywood sound films). In a manner not unlike that of the “Mythologies” columns Roland Barthes published in Les lettres nouvelles and France-observateur in the 1950s (and eventually collected in his classic book Mythologies), Nardal undertakes a critique of periodical print culture from within periodical print culture, subtly exposing and contesting the parameters of what we might call (after Antonio Gramsci) colonial “common sense” (Gramsci 173). She claimed self-deprecatingly not to have had a formal “political education” (Grollemund 87), but these columns amounted to a training ground in the sphere of colonial politics in which Nardal was guided above all by what she intriguingly calls her “intuition,” as she allowed herself to “suivre la pente de mon tempérament” (“follow the slope of my temperament”; Grollemund 30).

In an interview decades later, Damas recalled that the loosely knit groupings of black students and intellectuals in the metropole in this period were not only reading African diasporic papers; they voraciously consumed the full spectrum of what was available. Le monde, L'humanité, La revue mondiale, Les nouvelles littéraires, Gringoire, Candide, Le libertaire, L'onirique: “tous ces journaux se complétaient” (“all these newspapers complemented each other”; 30), he said:

[N]ous les lisions tous, nous les “futurs” de la négritude, nous lisions tous ces journaux et nous nous les repassions. Nous ne pouvions pas tout acheter, mais nous désignions deux ou trois personnes pour en acheter trois ou quatre par semaine et, en fin de semaine, nous faisions une espèce de relevé de presse collectif pour nous permettre de savoir où nous allions, sachant d'où nous venions et ce que nous voulions faire. (30)

We read them all, we the “future generation” of Négritude, we read all these papers and we passed them among ourselves. We couldn't buy everything, but we would designate two or three people to buy three or four every week, and, at the end of the week, we would produce a sort of collective press summary to let us figure out where we were going, knowing where we were coming from and what we wanted to do.

In other words, Nardal was engaged in a mode of writing that allowed her to formalize and publicize the more ad hoc kinds of autodidacticism that were a hallmark of her milieu. As Gianoncelli observes, it is crucial that Le soir did not impose a template or a protocol, but instead afforded her enormous leeway for experimentation: “c'est la relative instabilité des norms du milieu journalistique qui en font un espace ouvert, accessible aux sujets altérisés comme elle, et dans lequel elle peut s'exprimer de différentes manières” (“it is the relative instability of the norms of the journalistic milieu that makes it an open space, accessible to othered subjects such as Nardal, and in which she is able to express herself in different ways”; 271).

Here is my translation of the opening paragraphs of one of the early columns, “Actualités coloniales: Un peu de tout” (“Colonial Current Affairs: A Little of Everything”), from 10 February 1930:

One often hears jokes about black schoolchildren docilely repeating after their teacher: “Our ancestors the Gauls …”—which isn't so funny, in the end, when it occurs to one that, in the Antilles, the race is thoroughly mixed and, despite the “inextricable” blends that Paul Morand describes with regard to Aframericans, Antilleans of color do often have some Norman ancestry in their genealogy.

However, the joke indicates a certain illogicality, which is demonstrated in imposing the history of the metropole as the sole legitimate area of study for colonized peoples. […]

In Martinique, we received a purely Latin education. Even before we came to France to finish our studies, we thus felt linked to the French by a true spiritual kinship. Unfortunately—or fortunately, for us—differences were made apparent by our stay in the metropole. More maladroit than malevolent, people made us feel on many occasions that despite all our shared heritage, they did not grant us full belonging in the great French family from a spiritual point of view. When a greater culture has developed a sharper sensitivity in you, certain subtleties escape you all the less.

In this way we came to turn toward the past of our race, in order to find there for ourselves themes, if not of pride, then of faith in its future. Why weren't we taught the history of our country, or of our race? We felt ashamed not to know the African past, just like the first metropolitan French visitor …

This is why the words spoken in the Chambre des Députés by M. Varenne on the subject of education in Indochina struck me as containing a certain portion of truth with regard even to the old colonies in the Caribbean. The Annamites, he said in short, have a past and a fatherland: it is because we too often make them forget it that some of them forget their duties toward France. […]Footnote 13

The closing detour is characteristic: without ever openly criticizing the French empire, Nardal looks comparatively across colonial contexts—shifting her gaze from Martinique to Indochina within the French empire, and elsewhere considering various locations in the British empire, especially India, as well as in the United States—as she considers the role of “les femmes de couleur” (“women of color”) under colonialism (“Femmes”). What emerges through this contrapuntal thought is “un souci internationaliste” (“an internationalist concern”) with the position of women in the contemporary global order (Gianoncelli 128). In this sense Nardal's work is a notable realization of something the historian Michael Goebel has argued was specific to the migrant milieu of interwar Paris:

[I]t was the common presence of people of very divergent provenances that accentuated the global inequalities of legal situations, social profiles, and political goals. Heightened awareness, often through comparisons and extrapolations from one case to another, helped enable new forms of thinking because interstices cracked open room for experimentation and alternative ideas, as well as practical leverages. Fissures, discrepancies, and disconnects made the imperial order appear less natural, thereby engendering a more profound questioning of the status quo of global power relations. (9–10)

A number of scholars have noted that Nardal's October 1935 article “Levée des races” (“The Rise of the Races”) marks a significant shift in her political perspective as a result of her activism around the Italo-Ethiopian conflict (Boittin 162–64; Umoren 37–43; Gianoncelli 280–81). The three articles she published in an obscure Catholic journal, La revue de l'Aucam, in the spring and summer of 1936, after a speaking tour through Belgium, are even more remarkable in this respect. The Italo-Ethiopian conflict, Nardal writes in one of her pieces, “avait arraché la grande masse des Noirs à son indolence et à son insouciance. Avec l'incursion des Italiens en Abyssinie, le souci de l'avenir de la race est entré dans le champ des préoccupations des Noirs” (“wrenched the great Negro masses out of their indolence and insouciance. With the incursion of the Italians into Abyssinia, a concern for the future of the race has entered among the preoccupations of Negroes”; “Conflit” 256). She adds that “des signes d’émancipation de la pensée apparaissent dans certaines colonies, des communistes diraient, d'esprit critique” (“signs of the emancipation of thinking are starting to appear in certain colonies imbued, as the communists would say, with a critical spirit”; 258).

In these articles, there is a notable shift in Nardal's tone. “J'avais toujours cru” (“I had always believed”), she continues in the same piece,

que la forme du régime politique de la nation conquérante devait rester indifférente aux peuples colonisés tant que ceux-ci n'auraient pas atteint le niveau de civilisation de leurs métropoles. Mais les évènements actuels m'ont démontré mon erreur, les peuples colonisés étant à la fois l'enjeu et les victimes de la lutte des trois régimes politiques qui se disputent actuellement l'hégémonie du monde, à savoir, le fascisme, le bolchevisme et la démocratie. (260)

that the form of the political regime of the conquering nation should remain indifferent to colonized peoples up to the point when the latter had attained the same level of civilization as their metropoles. But current events have shown me my error, as colonized peoples are at once the stakes and the victims of the struggle among three political regimes that today are disputing the hegemony of the world—that is, fascism, bolshevism, and democracy.

In 1932 Claude McKay wrote a letter from Tangiers to Nancy Cunard, who was gathering material for her monumental 1934 Negro Anthology. McKay recommended that Cunard contact Nardal in France, saying that “she could be useful,” but adding with his usual brusque humor, “I do not know if I have to specify that you had better not hold too leftist a language.” But Nardal's writings about the Italo-Ethiopian war document a political mind in flux—not in the throes of conversion, but grappling openly with what she termed the “psychological repercussions” of Marxism among populations of African descent. It is an unexpected Nardal. Here is a passage from another of the articles in La revue de l'Aucam:

In one of the meetings organized in Paris by the Negro associations in support of Ethiopia, I heard an orator say, “Ethiopia must be given to Italy, because Italy is suffocating. Very well. If so, I do not see why, in France, poor families with numerous children living in cramped and insalubrious housing do not say to those who are in better circumstances, ‘I don't have enough space at home. You have plenty of unused rooms and you don't have children. So I'm moving in with you, and I'm going to seize everything you have to which I would thereby afford a real utility.’”

Such reasoning is in itself irrefutable. It is this sense of justice that has all the black populations of the world standing at Ethiopia's side.

The present conflict has moreover had the effect of making the Negro reflect on his condition in relation to the white race. The most loyalist and the most assimilated of these Negroes have not been able to hold themselves back from revising certain of their judgments. Such a convinced radical wonders whether it isn't the communists who are right after all. As soon as hostilities break out, such a student, previously indifferent to political questions, seeks to join the socialist party. The black Marxists are winning. (“Races” 141)Footnote 14

Sharpley-Whiting has suggested that the “next frontier” in Nardal scholarship will be “more in-depth probing of the soeurs Nardals’ creative literary output” (“Clamart Salon” 60). This may not be a question of emphasizing her fiction over and against her nonfiction, however, but instead of attending to the complex ways her experimental ethos as a writer working across multiple venues in the interwar period involved a productive blurring of generic lines, particularly among fiction, memoir, political commentary, and cultural reportage. Interestingly, it may be in this respect that Nardal's writing is most compellingly engaged with the stakes of Négritude as a poetics, if we follow Carrie Noland's astute observation that in its experimentalist bent, “[N]egritude may be seen to stand at the cusp … between two distinct moments in the evolution of poetics, exemplifying for some the depersonalization and disembodiment that occurs in an ‘aesthetic regime’ while ushering in for others a new valuation of the author and his or her presence in the text” (6).

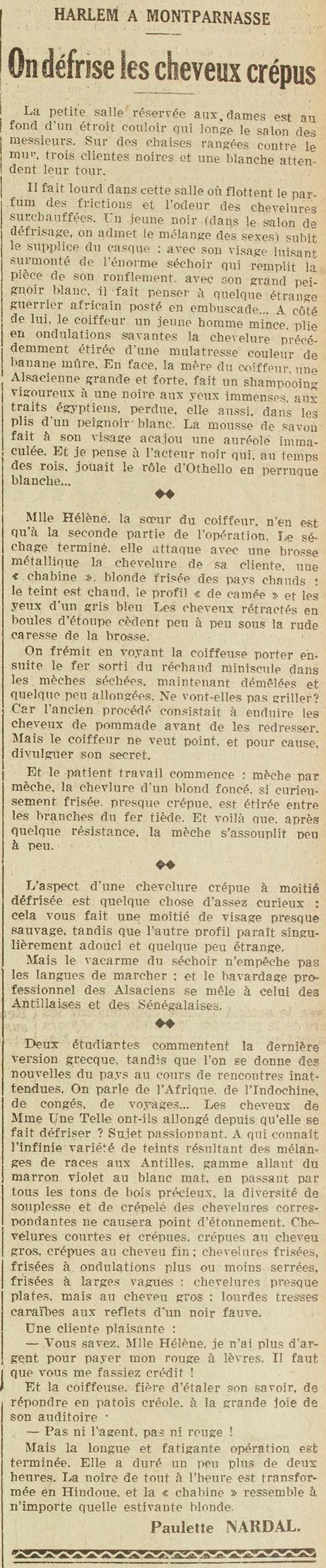

Here is my favorite of Nardal's amphibious pieces, “Harlem à Montparnasse: On défrise les cheveux crépus” (“Harlem in Montparnasse: We Straighten Nappy Hair”), published in the newspaper Candide in July 1935 (fig. 3):

The little room reserved for women is at the end of a narrow hallway running alongside the men's salon. Seated in a row of chairs against the wall, one white and three black women await their turns.

The air in the room is heavy with the scent of scalp massages and the odor of overheated hair. A young black man (in the hair-straightening salon, there is mixed admission of the sexes) suffers the torture of the hair dryer: with his gleaming face covered by the enormous helmet that fills the room with the sound of his snoring, wrapped in a great white gown, he brings to mind some strange African warrior poised for ambush … Beside him, the hairdresser, a thin young man, folds in knowing waves the previously stretched-out hair of a mulatresse the color of a ripe banana. Across the room, the hairdresser's mother, a tall and strong Alsatian woman, gives a vigorous shampoo to a black woman with immense eyes and Egyptian features, who is similarly lost in the folds of a white gown. The soapsuds give her acajou face an immaculate aureole. And I think of the black actor who, in the era of kings, played the role of Othello in a white wig …

* * *

Mademoiselle Hélène, the hairdresser's sister, has only reached the second part of the operation. The drying session finished, she wields a metallic brush to attack the hair of her client, a “chabine,” a curly-haired blond of the tropics: sultry complexion, profile like a relief carving, and blue-gray eyes. The hair, retracted into balls of oakum, yields little by little under the rude caress of the brush.

One shudders to see the hairdresser next take the hot iron out of a miniscule warmer and apply it to the dry strands of hair, now untangled and more or less stretched out. Won't they roast? The old procedure consisted of coating the hair with pomade before straightening it. But the hairdresser doesn't want to divulge his secret, and for good reason.

Fig. 3. A clipping from Candide featuring Paulette Nardal's article “Harlem à Montparnasse: On défrise les cheveux crépus.” Reproduced with the permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

And the patient labor begins: strand by strand, the dirty blond hair, so curiously curly, almost kinky, is stretched out between the tongs of the warm iron. And in this fashion, after some resistance, each strand relaxes little by little.

* * *

The look of a half-straightened head of nappy hair is something rather curious: it makes half your face look almost savage, while the other profile seems oddly softened and hardly strange at all.

But the din of the hairdryer doesn't keep tongues from wagging: and the professional chatter of the Alsatians mixes with that of the Antillean and Senegalese women.

* * *

Two female students swap comments about the latest Greek translation assignment, while other clients who have run into each other unexpectedly share news from the home country. People talk about Africa and Indochina, about vacations, about trips. … Did the hair of Madame So-and-So settle down after she got it straightened? An engrossing topic. For anyone familiar with the infinite variety of skin colors resulting from the race mixtures of the Antilles, ranging from violet brown to matte white and passing through all the shades of precious woods, the diversity of the pliability and nappiness of the corresponding hair is no cause for surprise. Short, kinky hair with thick curls or thin; hair that is curly with more or less dense undulations, or in broad waves; hair pressed down flat but with fat locks; heavy Caribbean tresses with hints of reddish black.

One client jokes:

— You know, Mademoiselle Hélène, I don't have any more money to buy my lipstick. You've got to put me on credit!

And the hairdresser, proud to display her knowledge by replying in Creole, to the great delight of her audience:

— No money, no lipstick!

But the long and tiring operation is finished. It has lasted a little more than two hours. The black woman from a little while ago has now been transformed into a Hindu, and the “chabine” looks like any other blonde ready for a night out on the town.Footnote 15

Giving space in this column to selections from Nardal's lesser-known articles is an attempt to follow one of the most impactful areas of her intellectual practice, her work as a translator. It is also a way to pay tribute to the aspect of her work that has received perhaps the least attention: her role as an editor (shaping the content and ordering of periodical issues in ways that go beyond her own writing). Looking for sources in the papers of Eslanda Robeson, one of Nardal's many contacts among the African American intelligentsia, the historian Emily Musil discovered Nardal's 1930 press card from Le soir (21). It is worth noting that the press card identifies her neither as a journalist nor as a translator, but instead as a contributor with an editorial role: “Mademoiselle Paulette Nardal, Rédactrice.”