Introduction

Governments, their functions, and powers; their partisan (or non-partisan) composition; their relations with other constitutional bodies; and the processes leading to their formation and dissolution, are all topics extensively covered by political science research. The territorial composition of governments has instead received less attention (Dogan Reference Dogan1989a; King Reference King, Greenstein and Polsby1975). Recent works on territorial representation of ministers are mainly case studies or small comparative works devoted to federal or strongly decentralized systems (Dodeigne Reference Dodeigne2014; Kerby Reference Kerby2009; Rodríguez Teruel Reference Rodríguez Teruel2011). However, in the context of unitary polities, ministers are not supposed to represent territories. Nonetheless, it is self-evident that individual members of governments do have a territorial characterization. Like anyone else, prime ministers, ministers, and junior ministers have preferential attachments and ties to certain places. In many cases, they have explicit political ties to a particular geographical area, given that they might cover (or have covered) public offices in that area at the time of their governmental appointment. Moreover, in many countries, it is assumed that members of the government are also members of parliament and are therefore elected from a particular geographical constituency – and presumably concerned by its interests and demands. Considering that in modern parliamentary democracies both the legislative initiative and the implementation of laws rest, to a large extent, on the executive branch of power, it is safe to argue that territorial imbalances in the composition of governments may have a remarkable effect on how that power is exercised, and how resources are allocated among different areas.

In this article, we aim to shed some light on these aspects, with reference to the Italian case. To be sure, we are not the first to focus on the territorial configuration of ministerial positions in Italy. Most of the extant literature, though, focuses on the early decades of the Italian republic, the so-called first republic (Calise and Mannheimer Reference Calise and Mannheimer1983; Cotta Reference Cotta, Blondel and Müller-Rommel1988; Cotta and Verzichelli Reference Cotta and Verzichelli2002; Dogan Reference Dogan and Dogan1989b; Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli, Dowding and Dumont2009).Footnote 1 In the following pages, we will instead focus on the changes of the territorial representation of governments from 1976 to 2021, a period that covers the last decades of the first republic and the subsequent transformations of the party systems.

Beyond the existence of a number of studies dedicated to the earlier period, we think that there are some good reasons to focus our attention on the factors that are supposed to change the framework of territorial representation during the past 30 years. Three elements, in particular, deserve our attention: the first one, as said, is the collapse of the first-republic party system (started in 1992 and completed with the crucial elections of 1994) and the subsequent restructuring of a new pattern of political competition. We will see that new political actors emerging or gaining governmental status in this period have a role also in the territorial transformations of the executive branch. The second factor is the discussion around the notion of “federalism” and the changes in the organization of the state, from the new electoral laws for local representatives (1993) to the constitutional reform of 2001, that designed a new system of relations between the center and the periphery of the state (Baldini and Baldi Reference Baldini and Baldi2014; Caciagli and Di Virgilio Reference Caciagli and Di Virgilio2005; Roux Reference Roux2008). This is relevant for the change of career patterns leading from the periphery to the center of the state (Freschi and Mete Reference Freschi and Mete2020; Grimaldi and Vercesi Reference Grimaldi and Vercesi2018). The third and final factor concerns the frequent recourse, during the past three decades, to technocratic and nonpartisan ministers, due to the recurrent political crises and the increasingly declining appeal of the “party government” model (Verzichelli and Cotta Reference Verzichelli, Cotta, Pinto, Cotta and de Almeida2018).

In the following section, we will first briefly sketch the route of the territorial composition of Italian political elites in the long term, since the foundation of the unitary state. We will then focus on the new puzzles of territorial representation at the turn of the 21st century, proposing our expectations for the impact of the restructuring of the party system. In the final sections, we will bring empirical evidence of the transformations of ministerial elites in relation to territorial representation, and we will discuss our findings.

The Italian Ruling Class between Centripetal Forces and Territorial Representation

Italy turned 150 as an independent polity “only” in 2011, and it has spent most of this time as a unitary form of state (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2006). Indeed, the constitutional monarchy established after the 1861 unification prevented the introduction of strong devolutions of power, in the attempt to unify a very fragmented territory crossed by several social, cultural, and economic cleavages. The French model of the préfet (prefect) had been adopted by the Kingdom of Piedmont (and then by the unitary state) to control the centrifugal effect of the development of municipalities. Even the introduction of a meso-level administrative unit (later renamed provincia) did not determine a significant devolution, due to the persistence of strict central government controls on the acts of all the territorial governments.

Even more evidently, the Fascist regime, which developed between 1922 and 1925, strengthened the unitary nature of the Italian polity, conceiving the nationalist myth as a core instrument of the authoritarian belief system. More precisely, starting in its early years, the regime reduced the powers of local authorities, substituting the directly elected mayors with local sheriffs (podestà) appointed by the party and increasing the instruments of central control in the hand of the prefects. The effective results of the centralizing strategy of the fascist regime over its 20-year-long rule may be a matter of discussion (Corner Reference Corner2012). However, we can surely argue that the premises of a more modern territorial organization of the state, which emerged during the last decades of liberal Italy, were abruptly cancelled with the consolidation of the authoritarian regime.

After the breakdown of fascism, a mild regionalization was then contemplated by the 1948 constitution (Hine Reference Hine1993). However, once again, due to the strategic choices of the dominant governing party – the Christian Democracy – the implementation of such a constitutional feature was delayed for more than two decades. Only five regions representing multilinguistic and peripheral territories – the Alpine areas of Aosta Valley, Trentino–Alto Adige, and Friuli–Venezia Giulia; and the two largest Italian islands (Sardinia, Sicily) – were provided with a special status and could start electing their own representative assemblies.Footnote 2 During this last period, regional governments have become increasingly relevant in terms of powers and political visibility of their leaders (infra). Still, tensions have continuously emerged between them and the central government, and the never-ending debate about the future territorial organization of the political system has indeed gained strength since the 1990s (Basile Reference Basile2018). The recent pandemic crisis has highlighted once more the uncertainties of a “mixed” and asymmetric regional system, which tends to increase the sharing of policy responsibilities among the territorial governments, without pointing to a federal or, vice versa, to a genuinely unitary model.

On this basis, one may be tempted to conclude that the relevance of territorial politics should be somewhat limited in a country long portrayed as a strongly centralized political system. However, we know from all historical accounts that this is not true. In the old days of the constitutional monarchy, an incremental process of nationalization of territorial elites developed after the first phase of predominance of the leading group of leaders from the Kingdom of Piedmont, which had led the process of unification. Particularly, after the end of the Piedmont-based destra storica (historical right) parliamentary elite (1876), the liberals became a compound and indeed “national” group of rulers – a sort of coalition of rentiers (Farneti Reference Farneti1989) unifying the interests of aristocratic landowners from the deep South with the upper- and middle-class owners from other territories. The appointment of the Sicilian patriot Francesco Crispi (former republican, but then closer and closer to the Savoy monarchic design of unification) as prime minister in 1887 can be taken as the peak of this first process of national elite building.

The need to balance the interests of different segment of notables was perceived not from party or social organizations, but from some coteries of deputies and senators (the latter appointed by the king according to the Statuto Albertino, the constitution of the Italian monarchy) who tended to build a comprehensive area of ministerables across the two historical components of the left and the right of the liberal ruling class. The practice of trasformismo (Valbruzzi Reference Valbruzzi2014) was therefore a process of individual-level coalition building based, despite the relative institutional role of local politics, on the settlement among local elites. Territorial representation therefore used to play a crucial role, especially under some relevant cabinets – for instance, under the leadership of Giovanni Giolitti, who was appointed prime minister five times between 1892 and 1921.

The same can be said even concerning the period of consolidation of the fascist rule. The most accurate historical reconstruction of the political class of the regime (Musiedlak Reference Musiedlak2003) shows the incremental territorialization of the first circle of leaders included in the Gran Consiglio del Fascismo: the highest body of the Fascist National Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista [PNF]), which served as a sort of nonelective political institution. Over time, all those rulers who occupied relevant positions in the two-decade life of the Mussolini cabinet were somehow balancing the different territories. However, two differences characterize the territorialization of the fascist ruling class from the previous experience of “liberal Italy.” First of all, and obviously, this process was not the result of a free convergence of local representatives but the effect of a top-down organizational penetration of the PNF, whose elite had been dominated – before the March on Rome (October 1922) – by several figures from the northern area. Second, unlike what happened to the liberal elites at the end of the 19th century, it was the bulk of the central regions (where left parties opposing the regime had been more resilient) and not the southern part of the country that were to be “rewarded” by the long-term consolidation of the Fascist ruling class (Musiedlak Reference Musiedlak2003, 165).

After the end of the Fascist regime, a new territorial distribution of national rulers emerged during the first three decades of democratic regime, and it was reflected in the composition of the ministerial elite. This phase may be defined as that of predominance of the Christian Democracy (DC) (Calise and Mannheimer Reference Calise and Mannheimer1983). However, the DC itself was a compound entity, with “ideological factions” and territorial groups cross-cutting each other (Wertman Reference Wertman, Gallagher and Marsh1988). Therefore, if the preference vote (employed in the election of the lower chamber) was an instrument to set the “internal competition” among the DC candidates who represented the national factions in each constituency, the problem of a “parity norm” in ministerial representation emerged soon in the republican age, among the territorial areas where the DC had its electoral strongholds. Not surprisingly, in fact, the “unwritten rule n. 5” in the decalogue reconstructed by Mattei Dogan in his analysis of Christian Democratic ruling class formation in Italy (Reference Dogan and Dogan1989b, 119) states that “all regions should be represented in the government.”

The application of territorial representation among Italian ministers was, as Dogan argued, slightly different from the system used in other Western democracies, such as the balance of ministers among representatives of German Länder or Belgium regions and linguistic communities. Indeed, the geographical prescription was sometimes taking the “aspect of a distribution between baronages” (Dogan Reference Dogan and Dogan1989b, 133). The ministerial “barons” were, at the same time, leaders (or prominent people) of national factions but also territorial representatives. No one described it better than Dogan:

The regional leaders are, at the same time, leaders of factions at the national level. When a government is formed, the regional dosage and the factional dosage are inseparable. To give a ministerial portfolio to any faction means to bring the “baron” of that region into government, and vice versa

(Dogan Reference Dogan and Dogan1989b, 134).Later studies on the Italian ministerial elite (Amoretti Reference Amoretti2002; Verzichelli and Cotta Reference Verzichelli, Cotta, Müller and Strom2003) have enlightened the dissimilarities in the territorial “structures of opportunities” from one region to another, due to deeply different subcultural attitudes of Christian Democratic factions. The northeastern leaders of the party, for instance, were very connected to the associative and social fabric of the Catholic sphere (and also to the small farmers associations), whereas the Christian Democracy of the South was more inclined to represent the persisting power of landowner families and notables. The decline of the DC role within the Italian political system, starting in the mid-1970s, has been another relevant intervening variable to be taken into account. Indeed, the other parties of the Pentapartito coalition, which expressed two prime ministers between 1981 and 1991Footnote 3 , did not present the same level of territorial complexity and factionalism of the Christian Democratic Party.

The political earthquake that tore the Italian party system down in 1992–1994 also had an impact on the territorial patterns of representation. This is not surprising, given that one of the main actors of that restructuring – namely, the Northern League – was a party with a heavy territorial connotation at its core. To such transformations we turn our attention in the next sections.

The Territorial Representation of the Italian Ruling Class. New Puzzles?

An original dataset covering all the Italian governmental positions since the mid-1970s will help us to explore the evolution of territorial representation among the Italian ministers in the last decades. This will bring us (in the next section) to elaborate more in-depth on the explanations of such changes, based on conjunctural rather than structural factors.

The first and most obvious change brought about by the breakdown of the first-republic party system was the beginning of alternation in government. For the purpose of this work, this means, in particular, that parties with new territorial specificities had access to executive positions for the first time. On the one hand, the Northern League became a relevant actor at the beginning of the 1990s. This party crossed the executive threshold in 1994 (cabinet Berlusconi I), and it returned between 2001 and 2006 and between 2008 and 2011, still as a minor partner of Berlusconi’s center-right coalition government. In 2018, the new League, led by Salvini, although it lost in part its territorial specificity, became the first party of the center-right cartel and joined a postelectoral coalition government together with the Five Star Movement. Finally, in 2021, it joined the grand coalition supporting the Draghi government. Overall, we can count 10 years of governmental presence of the (Northern) League during a period of 27 years.

In addition, the post-communist Party of the Left Democrats (PDS), later on renamed Left Democrats (DS), gained access to the executive for the first time in the 1996–2001 legislative term, with the cabinets led by Romano Prodi, Massimo D’Alema, and Giuliano Amato. Then, the center-left was in again power in the short 2006–2008 legislative term, during which its main components (Left Democrats and “the Daisy”) gave birth to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party was the main partner of the coalition government also in the 2013–2018 period, and it finally started supporting the Conte II cabinet as of 2019, as a partner of the Five Star Movement, before forming part of the Draghi government in 2021.

Although present in the whole country, the Communist Party (until the 1980s) and its successors have remarkably strong territorial roots in the central regions, especially Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany (the so-called Red Belt), where they have controlled the local branches of government for decades and systematically obtained their best electoral results. Our question about the endurance of the traditional parity norm may be formulated as the possible effect brought about by the access of these parties to governmental coalitions. To put it in other words, we may formulate the following expectation:

Expectation 1: The access to government of parties with strong territorial ties (Northern League on the right, and heirs of the Communist Party on the left) has resulted in an overrepresentation of northern and central regions among ministerial personnel.

The emergence of the Northern League in the 1980s is linked to another development of Italian politics in the two decades that followed. As mentioned in the introduction, significant steps toward a federal organization of the state have been made since the mid-1990s. Even though several authors have underlined its inconsistencies and limitations (Baldini and Baldi Reference Baldini and Baldi2014; Roux Reference Roux2008), the unitary form of Italy has been challenged in many ways. Administrative decentralization has empowered the subnational levels of government (the so-called Bassanini laws, 1997), a constitutional reform was passed in 2001 devolving new powers to the regions, and elements of fiscal federalism were introduced in 2009, granting regions the power to establish an autonomous taxation (Massetti Reference Massetti2012). More relevant to our argument, subnational political elites were empowered through a series of electoral reforms concerning both the regional and local level of government. In particular, the direct election of mayors (since 1993) and regional presidents (since 1999) helped to build a new set of political actors with wider recognition. In one way, that could mean that several local or regional politicians may use this political capital as a springboard for national political ambitions. The transition experienced by Matteo Renzi from the position of mayor of Florence to that of prime minister is certainly the most impressive example. On the other hand, however, the emergence of attractive subnational alternatives to the traditional upward career trajectory could mean that an increasing number of politicians prefer to invest in the municipal or regional arena (Borchert Reference Borchert2011). The perspective of a stable executive office at the local or regional level, which is now the rule, can definitely be an attractive asset when compared to the traditional instability of national cabinets. The comparative research in this field, however fragmentary, shows that in regionalized political systems (such as the postdevolution UK or Spain), executive positions at the regional level tend to become increasingly attractive and result in alternative career paths — that is, separate circuits where politicians choose between a national and a regional political career, with only occasional transitions between these two circuits (Botella et al. Reference Botella, Teruel, Barberà and Barrio2010). A similar pattern of growing distance between the subnational and the national political arenas has been found for legislative offices (Stolz Reference Stolz2011; see Tronconi Reference Tronconi, Best and Higley2018a for an overview of the literature). The above discussion can be summarized by the following expectation:

Expectation 2: Since the mid-1990s, the federalization of Italy and, consequently, the availability of attractive executive offices at regional and local level, have made ministerial positions less interesting for politicians with political experience at the subnational level. This is because regional and local careers are considered desirable per se, and they are viewed not only as a springboard to acquiring national positions.

The supposed decrease in the local political background of ministers brings to our attention another, more general phenomenon – namely, the decreasing role of parties in the recruitment of governmental personnel and the growing relevance of technocrats in Italian politics. The end of the so-called first republic was the most spectacular result of a crisis of parties that had its origins at least one decade before (Cotta and Isernia Reference Cotta and Isernia1996; Morlino and Tarchi Reference Morlino and Tarchi1996). One of the most enduring legacies of that crisis is the process of de-parliamentarization of the minister personnel (Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli, Dowding and Dumont2009; Verzichelli and Cotta Reference Verzichelli, Cotta, Pinto, Cotta and de Almeida2018). In particular, a robust number of technocrats or nonpartisan ministers have been selected since the early 1990s to fill the gaps of credibility and policy expertise of the core members of the national ruling class. The crisis of parties has become, in other words, a crisis of party government. To be sure, Italy is not the only country to witness this kind of development (Costa Pinto, Cotta, and Tavares de Almeida Reference Pinto, António and de Almeida2018; McDonnell and Valbruzzi Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014), but this country is certainly exceptional in the frequency of technocratic governments and the frequency with which nonpartisan ministers have been selected also in “ordinary” governments. When the selection of nonpartisan ministers becomes the rule, instead of an exception, the territorial composition of governments may also be affected. Technocrats, by definition, are recruited on the basis of their specific knowledge in a policy area, or their reputation in the international community. This has especially been true for economy ministers facing difficult negotiations with their European counterpart – first when joining the European currency, and then during the subprime crisis and its aftermath in the last decade – but technocrats have also been appointed in many instances to join politically led governments. Examples of this are in the Ministry of Justice (Giovanni Maria Flick during the first Prodi cabinet and Annamaria Cancellieri during the Letta cabinet), Education (Tullio De Mauro during the second Amato government), Interior Affairs (Luciana Lamorgese in the second Conte cabinet), Environment (Sergio Costa in the two Conte cabinets), and others.

In general, what we want to stress here is that although partisan ministers can be more or less linked to a specific territory, the appointment of technocrats necessarily follows a nonterritorial logic. Even when some technocrats pursue a career as elected representatives after their initial ministerial appointment, they can do so by virtue of their expertise, more than their territorial connections.

Expectation 3: Beyond the instances of wholly technocratic governments, the increasing recruitment of technocrats in ministerial offices after the end of the first party system (1992–1994) has weakened the territorial representativeness of cabinets.

In the following pages, we will investigate these expectations with reference to the 20 regions of Italy. Given the country under investigation, however, it is advisable to bring the macroterritorial North-South divide into the picture. The socioeconomic differences between these areas are indeed the most macroscopic divide of Italy since its unification, and this continues to be an unsolved problem, with many implications also in the political realm.Footnote 4

Long-Term Patterns of Territorial Representativeness of the Italian Government

To test the validity of the above expectations, we have assembled an original dataset by collecting the regional origins of all of the members of Italian governments from 1976 (Andreotti III government) to 2021 (Draghi government). This data will allow us to run a diachronic analysis covering the final period of the so-called first republic – the one less dominated by the Christian Democratic elite – and the following period, including the governments of the age of bipolar alternation (Cotta and Verzichelli Reference Cotta, Verzichelli, Müller and Strøm2000) and those formed after the economic crisis of 2008–2011, when the Italian party system moved to a tripolar format at both national and regional levels (Chiaramonte and Emanuele Reference Chiaramonte, Emanuele, Chiaramonte and De Sio2014; Tronconi Reference Tronconi2015). As we have said, we are first interested in describing the (regional) geopolitical representation of the national rulers. For this reason, we rely on the “region of birth” of all the officeholders instead of the “region of election,” which can be measured only in the decreasing number of national rulers with a parliamentary background (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017).Footnote 5

Figure 1 describes the trend of two indicators of our dependent variable. The bars represent the number of regions with no ministerial representation in each government. The line reports an index of disproportionality measuring the proportion between the distribution of population and the distribution of ministerial spoilsFootnote 6 .

Figure 1. Territorial Disproportionality of Italian Members of Governments

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

A first look at this picture leads to two general comments. First of all, the low level of disproportionality of the period 1976–1994 (which confirms the analyses briefly reviewed above) has been challenged at different moments after the end of the classic Italian partitocrazia. Technocratic or technocratic-led governments (McDonnell and Valbruzzi Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014) or even other governments with a high density of nonpartisan ministers are those more evidently breaking the unwritten rule of regional representationFootnote 7 . However, the governments of the period following the age of alternation (after the crisis of Berlusconi IV cabinet) have been regularly characterized by a relatively high degree of disproportional regional representation.

We have calculated the same indicators taking into account only ministers (figure 2). Obviously, the lower number of cases in this figure results in less clear evidence and a more erratic pattern. However, the overall trend remains the same: relative stability of the territorial representation of ministers during the first republic replaced by a clear lack of representation when technocratic governments have been formed. In addition, governments formed after 2013 are less representative than their predecessors, although this evidence certainly needs further confirmation.

Figure 2. Territorial Disproportionality of Italian Members of Governments (Senior Ministers Only)

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

If we look at the pattern of territorial representation of the Italian ruling class in terms of macroregional distribution (figure 3), we discover that the balance between northern and southern representatives has not changed a lot over the years. However, two pieces of evidence emerge: the “anomaly” of the low presence of representatives of southern Italy during the phase of the crisis (at the end of a phase of increasing representation of southern regions) and, on the contrary, the peak of success of southerners during the Conte II government formed in 2019. We will come back on these outliers later.

Figure 3. Percentage of Southern Government Members

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

Note: Northern regions include Valle d’Aosta, Piemonte, Liguria, Lombardia, Trentino–Alto Adige, Friuli–Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, Toscana, Umbria, and Marche. All the other regions are considered southern.

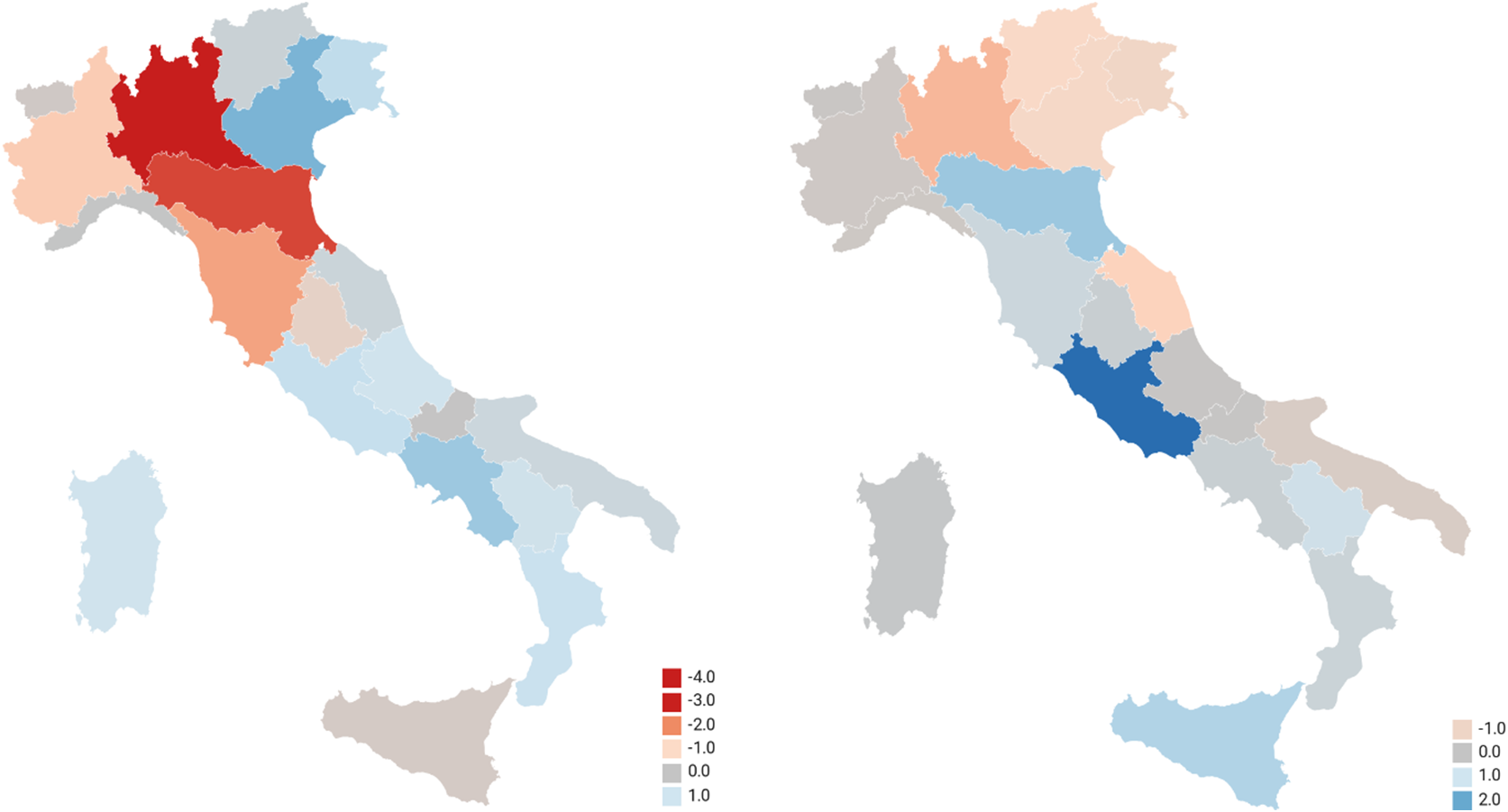

To sum up our descriptive analysis of the dependent variable, we produced the choropleth maps of regional representation of the Italian ministers during two periods: 1976–1994 and 1995–2021 (figure 4). The different colors reproduce the deviations between the distribution of population and the average percentage of government members who were born in each region. The spread of “neutral” territories (in gray in the maps, showing a representation close to perfect proportionality) is patent, especially during the final phase of the first republic, when about a half of the Italian regions look perfectly represented by the ministerial elite, whereas a few of them were clearly underrepresented – in particular, a “red region” such as Emilia-Romagna and a rich region such as LombardyFootnote 8 . The following period looks a little more complicated: the regions from the old Red Belt were more represented after the entrance in the government of leftist parties, but Sicily also shows a relatively higher proportion of ministerial personnel. The most evident case of gain, however, has been that of the region of Rome. Such a phenomenon may be presented as a paradox: the government marked by the peak of success of two northern center-right leaders such as Silvio Berlusconi and Umberto Bossi, indeed, has expressed a growing representation of southern ministerial personnel.

Figure 4. Regional Under/Overrepresentation of Government Members before and after 1994 (percentage points)

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

Explaining Diachronic Deviations from Regional Proportional Representation

The first expectation we put forward above deals with the territorial specificities of political parties, and particularly with the fact that parties with strong territorial linkages (the Northern League and the post-communist parties) reached the governmental threshold in the mid-1990s. In table 1, we disaggregate the territorial composition of governments by party, or party family, where the low number of ministerial appointments required an aggregation of data. Here, we can see how the homogeneous balance in the territorial representation of governmental personnel – typical among the old cohorts of Christian Democratic ministers – has been evident in all of the political delegations during the old days of the first republic. Conversely, the distinct elements of the two coalitions alternating in government between 1996 and 2011 have presented somewhat different patterns. In the center-left camp, the heirs of the Communist party show a predominance of ministerial elites from the northern and central regions, whereas the Catholic component of the coalition recruited a majority of governmental positions among its southern politicians. Another pattern of asymmetrical distribution appears when one looks at the distribution of the center-right cabinet ministers, which has to balance the “natural” territorial profile of the Northern League personnel. But although the Catholic parties and the post-fascist ones tend to overrepresent the South, Berlusconi’s party – Forza Italia (Go Italy!) – looks like a full-fledged national actor. Indeed, it shows the lowest disproportionality index – even lower than that of the DC. Such distribution is an effect of the personalistic nature of Berlusconi’s party (McDonnell Reference McDonnell2013; Raniolo Reference Raniolo2006): a light and nonterritorial organization (Diamanti Reference Diamanti2009), which, especially during its golden age (2001–2008), has been able to attract several territorial leaders from preexisting parties. These latter constituted a robust net of local and regional references and, in the end, the core of the parliamentary and ministerial “nomenclatura” of a strongly personalized (and quasi-“patrimonial”) type of political party – that is, a regional representation of the national ruling class quite similar to the old Christian Democracy but under a completely different form of leadership.

Table 1. Measure of Disproportionality and % of Southern and Northern Cabinet Members by Party

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

The attempt of Berlusconi to merge Forza Italia with other parties from the coalition under the broader Il Popolo della Libertà (People of Freedom, 2008) did not work due to the diminishing reputation of the leader and to the rising conflicts on European integration, immigration, and other crucial issues. But one of the most patent lines of division between Forza Italia (Berlusconi’s party took back its original name in 2013) and the other radical right and Catholic parties of the center-right is the different territorial distribution of their political elites. As the table shows, the latter actors are much more “southern” than Forza Italia, thereby producing a rather complicated system of regional representation at the ministerial level (the League still mainly in the North, the “right radicals” in the South, and the “liberals” more or less spread all along the territory).

A polarized distribution of the coalition government ministers, depending on their party affiliation, seems to remain during the age of the tripolar party system after 2013. In particular, this applies to the two “hybrid coalitions” following the 2018 elections. But some caution is necessary here because we can only rely on two observations. Indeed, the two populist parties forming the first Conte cabinet in 2018 (the League and the Five Star Movement [FSM]) maintained a separate pattern of ministerial selection: although Salvini’s League – notwithstanding its process of nationalization and some electoral successes in southern regions – remains a party dominated by a northern ministerial elite, the FSM clearly looks anchored to a bulk of southern ministerial representatives. When the Conte II government was formed in 2019, the center-left Democratic Party (PD) took the place of the League as a coalition partner of the FSM. The approach of the latter (and dominant) party did not change, whereas the PD opted for a territorially balanced ministerial team. Therefore, we understand why the Conte II government has the highest level of southern personnel of the whole post-1994 era.

The analysis based on the region of origin of ministers helps to illuminate the difference between the clear pattern of territorial representation of the past, compared to the fragmented patterns of the recent period. It also highlights some intriguing paradoxes of our time: both the League and the FSM have a nationwide structure, but the former still clearly overrepresents the North, whereas the latter shows an evident overrepresentation of the southern part of the country. We find no other cases of territorial disproportionality of such magnitude. In the case of Salvini’s League, we can explain this phenomenon as an effect of organizational inertia. Although Salvini has made an effort – to some extent, a successful one – to transform the Northern League into a nationwide political force, its political class has not yet absorbed this transformation. The resilience of its ruling elite (especially its Lombardy segment) and the persisting gap in its electoral strength in northern and southern regions explains why its ministerial appointments keep being strongly unbalanced. The FSM has a more recent history and one based on digital infrastructures and an open refusal of territorial structuring until very recently (Tronconi Reference Tronconi2018b; Bordignon and Ceccarini Reference Bordignon, Ceccarini, Ceccarini and Newell2019). The predominance of a southern ministerial elite, in this case, reflects its stunning electoral success in the southern regions in the 2018 elections.

Table 1 unveils another interesting point. Nonpartisan experts were a tiny minority in the cabinets formed between 1976 and 1994 (26 out of 1,436), but their presence has grown to 168 (out of 1,187) in the following period, confirming our third expectation. This aspect can be further explored in figure 5, where we move our attention to career paths of senior and junior ministers. Here, our second and third expectations can be assessed. In the first place, different and somehow complementary points of view on the concept of “localness” of governmental elites can be adopted by looking at career paths of politicians, beyond their place of birth. Being (or having been) involved in the local or regional institutions signals a connection with local interests and demands that goes beyond the mere – but still significant – fact of being born in the same territory (Marangoni and Tronconi Reference Marangoni and Tronconi2011). Therefore, the columns in figure 5 show the percentage of governmental officeholders who have been previously elected at the local and/or regional institutional level. Parliamentary experience at the national or EU level is also displayed (shaded area) as an indication of the share of the ministerial elite with a national political background as opposed to a technical one.

Figure 5. The Political Experience of Government Members, at Subnational, National, and EU Levels

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

The figure illustrates a decreasing impact of local elective background, in line with our expectation, that is only partially compensated by a growth of ministers and junior ministers with political experience at the regional level. Admittedly, beyond the exceptional cases of the Dini and Monti cabinets, the sharpest decrease is related to the most recent governments (Conte I and II and Draghi). However, in a long-term perspective, we should acknowledge that the percentage of cabinet members with a local or regional political experience was always close to or above 70% until the beginning of the 1990s, whereas it has rarely been above 60% in the last three decades. Interestingly, the cases where the 60% threshold is overcome all belong to center-left governments (D’Alema II, Amato II, Prodi II, Renzi, Gentiloni). This can be explained by not only the traditional electoral strength of leftist parties in local elections but also the persistence of a traditional pattern of recruitment of the heirs of the Communist and Christian Democratic political organizations, where some elective experience at the subnational level was considered as an almost inevitable stepping stone for political ambitions at the national level.

Figure 5 also displays information about the broader trend of the reduction of political experience of Italian ministers due to the gradual inclusion of technocrats and nonpartisan rulers (Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli, Dowding and Dumont2009). Obviously, the technocratic governments of the past three decades contribute to the overall trend, but even some groundbreaking political executives (Berlusconi I in 1994, Prodi I in 1996) show a significant reduction of such an indicator. The two fully technocratic governments led by Dini and Monti emerge again as outliers (as seen in the two cracks in the gray area of figure 5), but it is interesting to note that, after those experiences, the percentage of ministers and junior ministers without a national or European political background does not go back to the previous situation. Nonparliamentary ministers were exceptional until the 1980s, but they were constantly above 10% after the Dini government, and close to or above 20% after the Monti government.

In table 2, the above discussion is summarized. The cross-tabulation compares four simple groups of “territorial constituency” experiences: parliamentary and subnational experiences, only parliamentary experiences, only subnational experiences, and no experience at all.

Table 2. Territorial Constituency Experiences of the Members of Italian Governments (%)

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

Note: for 1976–1994, N=1295; for 1995–2021, N=1190

The most interesting change over time is the increase of the “no experience” category, which used to be residual in the first republic, reaching 18.4% of the total number of rulers in the past three decades (we may easily overlap this category with that of pure technocrats). This entails a significant decrease of rulers with a territorial background (from 65% to 55.8%) and even a modest diminution of those presenting only the classical parliamentary background.

Territorial Representation within the National Ruling Class: An Assessment of Findings

It is time to wrap up and provide some general implications. The data we have presented so far shows that there is no dramatic change in regional representation between the final period of the first republic and the past three decades (figures 1, 2, 4), nor is there a strong trend in the direction of representing the North of Italy to the detriment of the South (fig. 3), as one might suspect, after the rise of the Northern League and the involvement in government of the heirs of the Communist Party. Consequently, our first expectation is not confirmed by the data. Paradoxically, during the period following the emergence of the Northern League, Veneto – one of the core regions of the Padania – loses weight in the Italian government. That basically means that the northeastern patrons from the old DC were more efficient than the Northern League in projecting their constituency to the national government.

Under Salvini, the original regionalism of the League has been replaced by new nativist and nationalist messages (Albertazzi, Giovannini, and Seddone Reference Albertazzi, Giovannini and Seddone2018). Although we have been able to detect a moderate nationalization also in terms of ministerial elites’ recruitment, with some 15% of cabinet members from this party being selected from southern regions (table 1), the core constituency of the party is still located in the North. Table 1 clarifies why the Northern League on one side and the post-communist parties on the other did not modify the overall territorial representation of the ministerial elite. In center-right coalitions, the presence of northern ministers belonging to the League is balanced by the post-fascist representatives and the heirs of the Christian Democrats, who are mostly southern. The same happens within center-left coalitions, where centrist post-DC parties bring a substantial southern representation in government, compensating for the ministers from the North and from the “Red Belt.”

Unlike the first expectation, our second and third expectations are confirmed. The growing importance of a circuit of local and regional recruitment created an alternative to the usual career path that goes from the local experience up the ladder to the most prestigious ministerial offices. We certainly need further qualitative investigations to assess the rationale behind career decisions of local elected officials, and particularly their decisions whether or not to try to run for national positions. However, from the available evidence, it seems that in many cases, the offices of mayor or regional president represent the highest point of a career entirely spent in the local arenas. Cases such as the one of Matteo Renzi, rising from the mayorship of Florence to the office of prime minister, may certainly attract the attention of observers, but they seem to be exceptional.

The decrease of ministers and junior ministers with local political experience has another, more subtle, explanation. Political parties are less and less efficient as agencies of elite recruitment. Serving in local and regional offices before attempting a national career is the typical route of partisan politicians, who have an opportunity to become rooted in their own territorial constituency and use this as a springboard for attaining higher offices. Moreover, parties may use this initial experience as a test of the loyalty and reliability of their potential candidates. In the last decades, however, this “internal” career path has become less frequent. Instead, lateral entries to executive offices, which used to be occasional, are now common. This brings us to our third expectation, given that the presence of policy experts without any previous political experience has in part replaced party politicians in ministerial positions.

On the basis of the data aggregated in tables 1 and 2, we can create a tentative summary (figure 6), which resembles a possible map of party “delegations” in government. Here, we summarize two dimensions of the territorial representation of ministerial elites, discussed in detail in the previous pages. The first dimension deals with the level of disproportionality of regional representation of parties. The second consists of the different types of territorial constituency experience that may be predominant within a given party delegation. In this map, parties located near the top-right corner combine these two types of territoriality – that is, parties bringing in government politicians from a specific territory and with a strong political background at the local level. Near the bottom-right corner, we identify parties that have an evenly spread distribution of cabinet members but a strong presence of experienced local politicians. As we move toward the left, we find nationwide parties that bring to government many national politicians or technocrats – that is, the two types of nonterritorial ministers. Finally, in the top-left corner, we have parties with a specific territorial focus and predominantly national or nonpolitical governmental delegations.

Figure 6. Mapping the Prevalent Attitudes of Territorial Representation of the Italian Parties (1976–2021)

Source: CIRCaP Italian Ministerial dataset (Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli Reference Martocchia Diodati and Verzichelli2017)

Note: in blue, the parties from the first republic.

The parties from the first republic (in blue in figure 6) look much closer to each other (this reflects the higher homogeneity in our data). In short, if the Christian Democratic rulers were typically characterized by local experiences and low levels of regional disproportionality, the smaller parties were less close to the territorial “parity norm” but kept recruiting ministers with strong political backgrounds (especially at the national level).

In the second republic, the Democratic Party, including politicians from post-Communist and post–Christian Democratic elites, is close to the bottom-right corner, although its level of territorial homogeneity is more unbalanced than the old Christian Democrats. However, if one looks at the truly original parties of the second republic, the most innovative patterns of territorial representation emerge. The League, especially in the original Northern League version, presents a high percentage of “local politicians” and a totally disproportional representation of national rulers. At the opposite pole, Forza Italia presents a ministerial elite much less oriented to the territorial background (and therefore made of national politicians) and more balanced among the regions. This justifies the label of “party without territory,” which Ilvo Diamanti (Reference Diamanti2009) has often used to describe it, to highlight the difference separating this organization from the parties of the first republic and the Northern League. As we have noted above, it shares with the DC an evenly spread distribution of governmental elites, but although the latter was, in a sense, the sum of factions with a strong local connotation, Forza Italia does not have a similar territorial rootedness. The FSM shows another peculiar territorial trait: nonpartisan expertise is overrepresented, and territorial representation is heavily skewed toward southern regions. The governmental involvement of this party is too recent to give conclusive assessments. For the time being, we are only able to note that a strong presence of “nonpolitical politicians” is typical of recently established parties before a more usual path of elite recruitment consolidates (Tronconi and Verzichelli Reference Tronconi, Verzichelli, Chiaramonte and De Sio2019).

Two trends have surfaced from our data: (1) the increase of government personnel with a technocratic – instead of political – background, and (2) the decline of government personnel having previously held local and/or regional offices. Moreover, we have noted how these trends have varied across parties, with variations becoming more extreme in the last three decades as new and organizationally innovative parties have emerged.

These transformations have taken place (or are, indeed, taking place) at the intersection of two broader political phenomena. On the one hand, political parties have significantly changed their internal organization and procedures – from the role of rank-and-file members to the selection of leaders; from their communication strategies to the relations between elected officials and interest groups. The list of relevant changes could be much longer than this. Among other aspects of these complex transformations, a central one pertains to the way parties “control” the career trajectories of their activists. In traditional mass bureaucratic parties, it was rare to be elected to the national parliament without having acquired some experience (and demonstrated loyalty) at the local level, and even rarer to become minister without being a member of parliament. Nowadays, however, it is much more common for parties to select candidates to the highest offices outside the party itself. This transformation can be interpreted as a result of the legitimacy crisis of parties. Those linkages with civil society that were once considered obvious, now need to be reaffirmed through the selection of people who are external to the party organization. Bringing into parliament, and into government, representatives of the worlds of culture, economy, the media, and sport can be a way to show the ability of the party to attract the most dynamic social forces.

On the other hand, party government has changed as well – in particular, the “partyness of government.” In a traditional vision of the functioning of government, parties are considered as principals of the executive power (when they are part of the government or governing coalition). In recent times, this linkage between parties (principals) and government (agent) has weakened. As part of the process of “prime-ministerialization” of politics (Dowding Reference Dowding2013), executive leaders now enjoy a degree of autonomy in selecting and deselecting their ministers and junior ministers that was unknown in previous political eras. This increasingly opens spaces for the selection of nonpartisan personnel because that individual may be thought to be more loyal to the prime minister than to the party of belonging. Or, that person may be perceived as being more authoritative in supranational negotiations with his/her peers, or more able to relate to the bureaucracy or to the interest groups that are relevant in a certain policy area.

The general trends that we have sketched here certainly need to be tested in comparative studies to see if and how far they can travel across countries. Nonetheless, our work, based on the Italian case only, shows that a long-term process of transformation of the selection of governmental personnel is underway, and one of its (provisional) results is the weakening of the territorial representativeness of ministerial elites.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors of the special issue and two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments on a first draft of this article.

Disclosures

None.