Introduction

To control the spread of coronavirus-19 (COVID-19), governments around the world imposed a range of measures to minimise close contact between individuals. The strictest measures included the enforced closure of shops, hospitality and entertainment venues, bans on mixing between households and non-essential travel, and curfews. Further guidelines included maintaining a 2-m distance between people not living in the same household, frequent hand washing, and the mandating of masks when visiting public indoor spaces. When these measures were followed by the public, they were reported to be effective at reducing virus transmission (Matrajt & Leung, Reference Matrajt and Leung2020). However, while high levels of compliance were observed in many countries during the pandemic (YouGov, 2021), there was some variation. For example, compliance has varied (1) by the type of behaviour being mandated (e.g. in the UK, some measures such as mask wearing were more closely followed than social distancing (IPSOS MORI, 2021; Wright, Steptoe, & Fancourt, Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021c; YouGov, 2021)), (2) over time (with evidence suggesting compliance levels decreased in the UK over time, especially as restrictions were lifted (Petherick et al., Reference Petherick, Goldszmidt, Andrade, Furst, Pott and Wood2021; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021c)), and (3) depending on individual characteristics (Moran et al., Reference Moran, Campbell, Campbell, Roach, Bourassa, Collins and McLane2021; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021c).

Indeed, a growing body of research has focused on this latter issue and sought to understand the characteristics that predict compliance with social distancing guidelines. Lower compliance during COVID-19 has been identified among younger people (Coroiu, Moran, Campbell, & Geller, Reference Coroiu, Moran, Campbell and Geller2020; Wright, Steptoe, & Fancourt, Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021a), those who are physically healthy (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021c), have higher incomes (Wright & Fancourt, Reference Wright and Fancourt2020), carers (Wright, Steptoe, & Fancourt, Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021b), and employed people unable to work from home (Denford et al., Reference Denford, Morton, Lambert, Zhang, Smith, Rubin and Yardley2021). Research from the COVID-19 pandemic and previous pandemics has also identified lower compliance among people who lack trust and confidence in their government (Bish & Michie, Reference Bish and Michie2010; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021b). However, while these studies offer some insight into the specific factors that influence compliance behaviours, there has been limited research into why some groups may be less compliant than other groups. There has also been limited in-depth qualitative enquiry to fully understand the potentially modifiable barriers and facilitators that individuals from different groups have faced in adhering to social distancing guidelines.

A small UK qualitative study conducted at the beginning of the pandemic found that participants experienced a sense of social and psychological loss, lack of trust in government, and a lack of clarity of communication of guidelines, although all participants reported high levels of self-compliance (Williams, Armitage, Tampe, & Dienes, Reference Williams, Armitage, Tampe and Dienes2020). The study, therefore, relied on participants hypothesising why other people may not be compliant. A second qualitative study explored the experiences of people on low incomes and people from Black, Asian, and other Ethnic Minority groups and identified a lack of clear messaging and guidelines that were open to interpretation, low perceived risk of catching, or transmitting the virus, and the need to receive or provide emotional support as reasons for breaking the rules (Denford et al., Reference Denford, Morton, Lambert, Zhang, Smith, Rubin and Yardley2021). Only one facilitator for adherence was identified: the need to protect vulnerable family members from the virus.

There is currently limited research explicitly drawing upon theoretical frameworks to help understand the psychological processes that might influence compliance with guidelines during a pandemic. Understanding these processes can help with the design of future interventions or public health campaigns aimed at increasing compliance behaviours. Theories such as the health belief model (Green, Murphy, & Gryboski, Reference Green, Murphy, Gryboski, Sweeny, Robbins and Cohen2020) and theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991) have traditionally focused on individual-level factors to explain health behaviours, and their explanatory power may be limited when studying barriers and facilitators to public health behaviours. The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behaviour (COM-B) model of behaviour (Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Francis, Islam, O'Connor, Patey, Ivers and Michie2017; Michie, van Stralen, & West, Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011) is an alternative theoretical framework that can help to explain the process of supporting or changing behaviours at the individual, social, and environmental levels. This model posits that an individual must have relevant psychological or physical skills (capability) and access to physical or social resources (opportunity) for a behaviour to occur. If these elements are in place, the individual is then supported to understand the need (reflective motivation) or feel the desire (automatic motivation) to enact the behaviour. For interventions to achieve effective behaviour change, one or more of these components should be targeted. Health psychology experts have used this model to identify interventions for increasing adherence to social distancing rules as part of a rapid response to early UK government policies (Michie, West, Rogers, et al., Reference Michie, West, Rogers, Bonell, Rubin and Amlôt2020). Suggestions included providing clear messaging about transmission risk and specific compliance behaviours, the use of media to promote positive messaging and a sense of responsibility to others, and the promotion of social approval for desired behaviours and disapproval for unwanted behaviours. A quantitative survey that used the COM-B model to assess barriers and facilitators to hygienic practices such as hand washing, identified reflective motivation as a key driver to compliance (Gibson Miller et al., Reference Gibson Miller, Hartman, Levita, Martinez, Mason, McBride and Bentall2020). However, to our knowledge, there has been no attempt to apply psychological theory to in-depth qualitative research that seeks to understand the conditions that might support or increase compliance with broader social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of this study was, therefore, to understand the barriers and facilitators to compliance with UK social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic and to use the COM-B model to map the underlying psychological processes influencing compliance.

Methods

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted as part of the COVID-19 Social Study (University College London Covid Social Study, 2021), which aimed to explore the psychological and social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults living in the UK. A phenomenological approach was taken, focusing on participants subjective experiences, meanings and changes in behaviour brought about by social distancing restrictions (Langdridge, Reference Langdridge2008). The study received ethical approval from the UCL Ethics Committee (Project ID 14895/005).

Participants were recruited through community organisations, social media, personal contacts, a study newsletter and website, and via partners associated with the UKRI MARCH mental health network. Potential participants contacted the research team via email if they were interested in taking part. Participants were purposively selected to take part based on their identification with one or more characteristics that potentially placed them at risk of poorer mental health and/or increased social isolation during the pandemic. This included people with mental health conditions, long-term health conditions, parents of young children, older (aged 70+), and younger (aged 18–24) adults. How the pandemic has impacted the mental health of each of these groups has been reported elsewhere (Burton, McKinlay, Aughterson, & Fancourt, Reference Burton, McKinlay, Aughterson and Fancourt2020; Dawes, May, McKinlay, Fancourt, & Burton, Reference Dawes, May, McKinlay, Fancourt and Burton2021; Fisher, Roberts, McKinlay, Fancourt, & Burton, Reference Fisher, Roberts, McKinlay, Fancourt and Burton2020; McKinlay, Fancourt, & Burton, Reference McKinlay, Fancourt and Burton2020; McKinlay, May, Dawes, Fancourt, & Burton, Reference McKinlay, May, Dawes, Fancourt and Burton2021). The current paper brings together these subsamples to explore barriers and facilitators to compliance with social distancing guidelines across different groups.

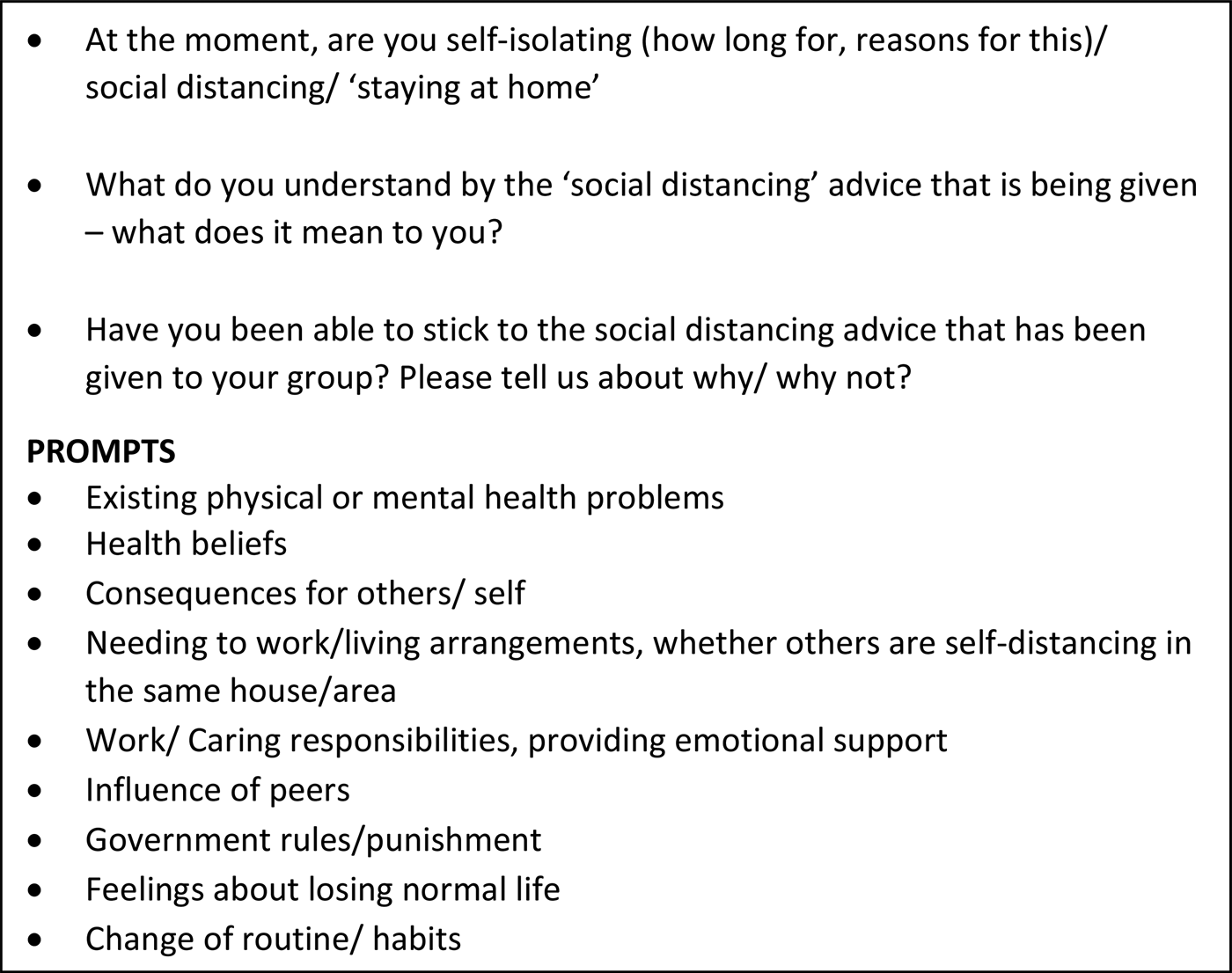

All participants received a study information sheet, provided informed consent, and completed a demographics questionnaire. Interviews were carried out by male and female researchers with backgrounds in social science, behavioural science and applied health research (AB, AM, AR, TM, RC, SE, and LB), public health (JD), and medicine (HA: a trainee medic, doctoral researcher). Interviews took place remotely via telephone or video call depending on participant preference and followed a topic guide designed to understand the impact of the pandemic and social distancing on social lives, mental health, and worries about the future. Questions and associated prompts on the potential barriers and facilitators to adherence to social distancing guidelines and associated restrictions were formulated using concepts from behaviour change theory (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). Participants were first asked whether they were self-isolating (i.e. whether they had symptoms of the virus or had come into contact with someone who had contracted it in the last 14 days), ‘staying at home’ (i.e. only leaving their homes for essential trips such as exercise or food shopping, either because this was mandated at the time or because they were shielding for themselves or someone else), or social distancing (i.e. going out but staying distanced from other people) and what they understood the social distancing guidelines to mean. They were then asked if they felt able to comply with the guidelines or not, and to elaborate on the reasons for their response (see Figure 1 for topic guide questions and prompts). After the interview, participants were offered a £10 gift voucher to thank them for their time.

Figure 1. Topic guide questions on social distancing guidelines

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by an external transcription company. Transcripts were checked for errors, de-identified and imported into NVivo12 for analysis. A combined approach of inductive and deductive analysis was undertaken in that an initial coding framework was developed using concepts from the topic guide and, as participants described new concepts, codes were added to the framework until no new codes were identified. Data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis following the six steps set out by Braun, Clarke, and Hayfield (Reference Braun, Clarke and Hayfield2019); firstly, AB read each transcript to familiarise herself with the data and then applied codes from the coding framework or assigned a new code to each line or paragraph of speech within each transcript. All transcripts were independently double coded by AB and one other researcher (JD, WF, TM, AM, or AR) who each met to discuss their overall impressions of salient topics within each section of text. Codes were then organised into initial themes and subthemes by AB to identify broad patterns of meaning across the data before being refined and checked that they corresponded to the research question. Themes were defined, named, and then mapped to domains of the Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Model of Behaviour (COM-B; Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011) and categorised as barriers, facilitators or both for compliance with social distancing guidelines. The research team met to review and discuss codes, themes and developing findings and to approve the final results.

Results

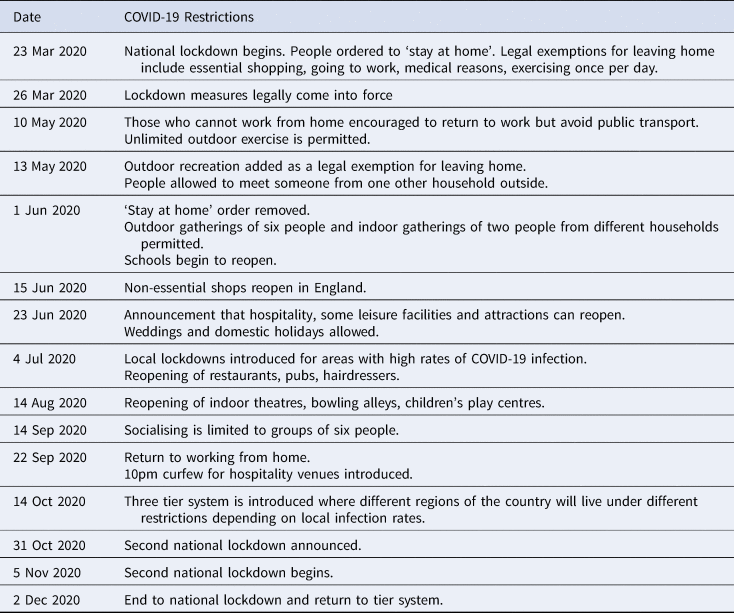

In total, 116 participant interviews were included in the analysis. Interviews took place between May and November 2020 and lasted on average 53 min. Twenty-six (22.4%) participants took part in an interview during a time of national lockdown in the UK (see Table 1 for a timeline of COVID-19 restrictions during the study period).

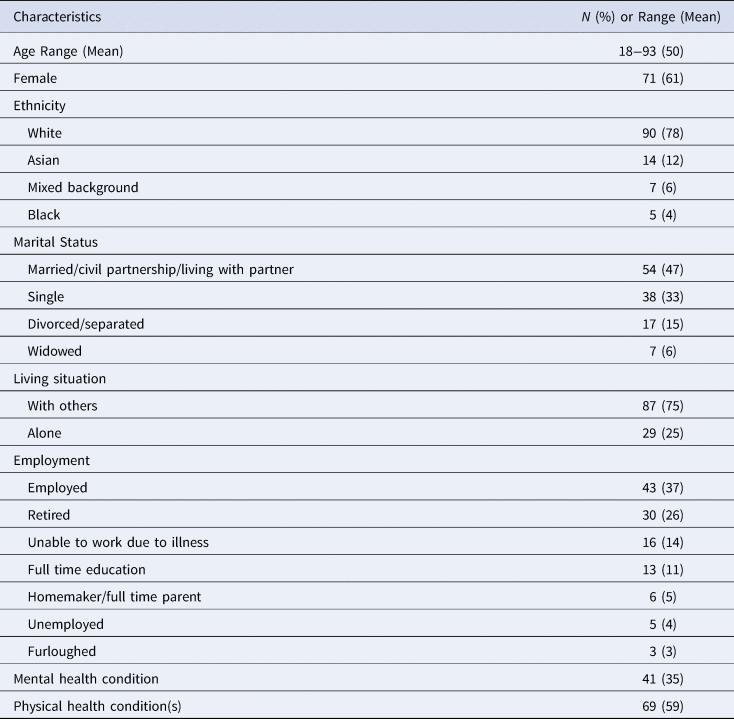

Participants were aged 18–93 years old (mean age = 50), predominantly female (61%), white (78%) and living with others (75%). Thirty-five percent of participants reported a diagnosed mental health condition and 59% reported one or more physical health conditions. See Table 2 for participant demographics.

a Restrictions were similar across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland; however, dates and precise details may vary.

b Brown and Kirk-Wade (Reference Brown and Kirk-Wade2021) and Institute of Government (2021).

Table 2 Participant Characteristics

Themes

Twelve themes influencing compliance with social distancing guidelines were generated from the analysis: five barriers, two facilitators, and five mixed barriers and facilitators. Most themes mapped to the COM-B domains of reflective motivation, physical, and social opportunity (see Table 3). Barriers to compliance included (1) inconsistent rules, (2) caring responsibilities, (3) a ‘wearing-off’ effect, (4) unintended consequences of control measures, and (5) the need for emotional support. Facilitators were (1) informational support and (2) social responsibility. Five themes acted as a facilitator for following the guidelines for some participants but were experienced as a barrier by others. These included (1) lived environment and shared spaces, (2) beliefs about the consequences of non-adherence, (3) influence of others, (4) availability of practical support, and (5) trust in government.

Table 3 Themes Mapped to COM-B Domains

a (B) = Barrier to compliance; (F) = Facilitator for compliance; B&F = Barrier and Facilitator for compliance depending on participant experiences and circumstances.

Motivation

Reflective Motivation

Compliance behaviours were mostly driven by reflective motivation with participants consciously evaluating the risks associated with contracting the virus. Participants reflected on their personal circumstances, experiences and social roles, and described their beliefs about what is right and wrong as influencing factors for compliance.

Beliefs about the consequences of catching the virus

Perceived risk to self

Older adults and people with health conditions were more likely to identify risks to their health and the perceived negative consequences of getting ill if they caught the virus as their primary motivation for following the social distancing advice. Many participants talked about their ‘fear of getting it’ or being hospitalised.

I'm really scared of getting it because … you know how everyone is like oh it's okay, they had underlying conditions. I'm like well great, that doesn't really fill me with confidence. So I think I probably would not survive if I got it so I'm trying to keep away from it (Female, aged 30–34, physical health condition).

Younger and healthy adults, however, perceived their risk of getting ill as low, and for some, this contributed to their decision to bend the rules, socialise with friends, and experience a ‘sense of normality’.

For me it's just if I'm going to get something I know that I'm low risk, I know everyone I'm living with is low risk and I know that everyone I'm living with is happy to go out and be socialising in the way that I am (Female, aged 20–24).

Beliefs about the consequences of catching the virus were often shaped by participant experiences of being ill themselves or knowing someone who had been ill with COVID-19. For those who had lost loved ones or knew someone who had been seriously ill, beliefs about the negative consequences of catching the virus were heightened. Many participants, particularly older adults, described this as an influential factor for compliance.

I don't actually know anybody who has died of coronavirus, but some of my younger relatives have had it, and these are young healthy adults, very strong, and … it's taken them weeks to get over it. So, I have great respect for this virus (Female, aged 70–74).

Some participants, however, experienced minor symptoms following a suspected case of COVID-19, which made them feel more relaxed about the social distancing guidelines.

Having almost certainly had coronavirus, myself and my wife probably having had it back in March, and with the kids, 50/50, probably having been exposed and the consequences being relatively low for them, hopefully, even if they haven't had it yet, I think we are pretty relaxed. I think I will characterise it as an informed, relaxed compliance with the rules (Male, aged 40–44).

Others cited not having any direct encounters with the virus as a reason to bend the social distancing rules, despite acknowledging rising infection rates.

I think whenever I have spoken to my friends about it and we are like sod it, let's go and do this. We are just fed up with it now. I don't know anyone who has had it. I don't know anyone who has died. I don't even know anyone who knows someone who's had it, even though we are living in an area where we know it's quite bad and you can see the figures constantly going up (Female, aged 30–34).

Perceived risk to others

Most participants described adhering to the guidelines to protect loved ones, vulnerable people who they worked with, or vulnerable members of the public. For some, particularly younger people, keeping other people safe was their primary motivation for following the rules.

I'm more concerned about catching COVID and then passing it on to somebody that it would do more damage to (Male, aged 20–24).

Those providing support to or living with vulnerable family members or friends described a heightened sense of responsibility and took extra precautions to try and keep their loved ones safe.

Purely because my flatmate, she is a little bit older, and she has a lung condition. So I was very aware of, I don't want to go and get exposed myself and then bring it back to her. So I basically did stay away from people as much as possible, purely because I didn't want to be infecting her (Male, aged 25–29).

For others, protecting members of the public was just as important as protecting themselves and their loved ones.

The only worry I have is that it will come back. And also that my family should be protected. Not only my family but everybody's family for that matter (Male, aged 74–79).

Caring responsibilities

Some participants cited their social roles and the need to provide practical support to others, particularly vulnerable relatives, friends, or young children as a reason for being unable to adhere to the social distancing rules during lockdown.

The only thing that I was doing, which I technically wasn't supposed to do but it really wasn't something I could stop, was going to shop for my grandma. Shopping in itself wasn't a problem, but she was 45 min away which wasn't really allowed, and also I did have to go in the house with her to put the shopping down (Female, aged 20–24).

Some also described the need to provide emotional support in-person to friends or relatives who were lonely, grieving, or struggling with their mental health during lockdown.

I would stand in the driveway and talk to her, but I think, over time, she became really lonely and really depressed, so it reached a point where we realised it wasn't practical to do that. And I was the only person she saw … So we'd go and sit in the garden instead (Female, aged 30–34).

Parents with young children described multiple challenges when attempting to follow the social distancing guidelines, including communicating the rules to their children and controlling their children's behaviour in social situations.

My son, he accepts that, he does find it difficult if we meet people outside. He'll start off maintaining a bit of a distance, but young children automatically want to play (Female, aged 40–44).

Some parents also described concerns about the emotional impact that social distancing might have on their children. They considered their actions and behaviour based on the psychological consequences of social distancing alongside the perceived low risk of contracting the virus or of experiencing serious illness from COVID-19.

In terms of him seeing his grandparents and our families we haven't tried to say turn him away, don't touch him, keep your distance. Because to be honest we just feel like there's a balance there. And for him to be shunned in terms of physical contact from his close family I think is probably more damaging potentially given the level of risk of him and us catching it (Male, aged 30–34).

Social responsibility

Some participants, particularly older adults, described following the social distancing guidelines as their ‘civil duty’ in order to ‘do my bit’ as part of a collective societal response. People described feeling as though everyone was ‘in the same boat’ and experienced ‘a wave of solidarity’ especially during periods of lockdown.

I definitely felt this sort of collective thing in the initial lockdown in a sense of trying to do something together for everyone, for other people, for society. I definitely felt that and I found that quite motivating and quite focussed in a way (Female, aged 40–44).

Some participants also chose to comply with the rules to avoid the National Health Service (NHS) being over-burdened.

I don't want to burden the health service either because I've broken my leg falling or something like that. To support the NHS and to keep healthy. That to me was very clear, that this was our duty, if you like (Female, aged 70–74).

Trust in government

Many participants described a change in public attitude to the social distancing restrictions, and for some a change in their behaviour following reduced trust in the UK government's ability to manage the pandemic. Participants mostly described their response to the behaviour of the chief advisor to the UK government (Dominic Cummings) breaking lockdown rules in the early stages of the pandemic.

We decided that, no, sod it, we are going to the pub and meet, that we are going to see our children and grandchildren. If it's all right for one of the chief advisors of the government then it must be okay (Male, aged 60–64).

Conversely, some participants described continuing to practice caution, even when the government rules were being relaxed. Participants described not trusting the government's motivations for lifting the restrictions, and, as a consequence, they would continue to follow their own stricter social distancing guidelines.

So regardless of what the government says, I will be preferring my own guidelines. Because I prefer reviewing all the papers … and I know how serious this thing is … and I know the government takes a balance of economics and health, and a lot of what I've seen, a lot of the decisions are not made on healthcare, but made on economics (Female, aged 65–69, physical health condition).

Automatic Motivation

Automatic motivation acted as a barrier to compliance with social distancing guidelines, with some participants prioritising their own emotional needs over strict compliance with guidelines.

The need for emotional support

For some participants, particularly young adults and those who lived alone, the need to access emotional support outweighed the perceived risks associated with breaking the social distancing rules. This often involved going into other people's homes and ‘breaking the lockdown’ to meet with loved ones when they were ‘struggling’.

We've been naughty. I'm going to say it because I think it's important. I think if I'd been on my own for the entire time, and not seen anybody … I think from a mental health point of view, it's probably saved me. They come and pick me up in the car, take me to their house. We put the views that I'm not seeing anybody else, so it's going to be safe (Male, aged 40–44).

Others described loneliness and the need to have physical contact with friends or have a conversation with ‘a checkout lady, man or the lady who was letting you go in (the shop)’ as the main motivating factor for leaving the house and bending rules around social distancing during lockdown.

I followed it religiously for seven weeks and it got to the point where I was just, not depressed every day but I was just thinking I don't have any motivation to work. I'm not sleeping at all. I've always been a touchy feeling person. I need someone to hug that isn't mum or dad (Female, aged 20–24).

Opportunity

Physical Opportunity

When the environments in which people lived were not conducive to social distancing, this created a physical barrier to compliance.

Lived environment and shared spaces

Home environment

Participants who had access to a private garden described this as an aid to following the social distancing guidelines, with less reason to leave the home for exercise or use shared public spaces.

I'm lucky in that I've got a small garden as well, so I can sit out in the garden and get fresh air and sunshine that way … I'm not stuck in a tower block like some people, so I'm lucky in that respect (Female, aged 50–54).

Participants who lived alone frequently described living in a naturally socially distanced environment ‘I live on my own, so I've got nobody else who's at risk in my household’. However, for those living with others, particularly older adults, students and those with physical health conditions, social distancing was particularly challenging. Some developed strategies such as creating ‘a daily rota’ for accessing shared spaces such as bathrooms and kitchens or socially distancing within the home.

The situation so far as he is concerned (is) that he is regarded as a key worker. He works for <Transport Company>. So, in fact, he social distances (from) me at home … Yes. He's worried about his old dad (Male, aged 80–84).

For others in high-risk categories and where family members did not have to go out to work, decisions were made between members of the household to isolate together to prevent virus transmission.

My wife basically started to work from home as well and started to isolate as well with me, because we took the decision to … I mean, we're not living in a mansion and it would have been virtually impossible for me to isolate from her (Male, aged 35–39, physical health condition).

Surrounding environment

Many participants described the importance of being able to access spacious public environments that supported their ability to socially distance from others. This included exercising or socialising in local parks and living in rural areas with access to the countryside and quiet spaces.

It's extremely easy to keep your distance because of where we live. We have such close access to fields and open woods and so on, and although other people are out walking as well, or running or cycling, everybody is keeping to maintain their social distance (Female, aged 70–74).

Some participants described reclaiming outdoor spaces that were normally reserved for private use or sporting activities.

We would drive along to this big golf course, and you could walk around that for hours and you wouldn't encounter anyone else. It wasn't like you were going to a park where there are lots of people and you were having to keep your distance (Female, aged 35–39).

For those living in built up urban environments, or in rural locations but needing to access essential items in town centres, complying with the social distancing guidelines was described as challenging.

I found it really difficult at the start, because we live two miles from the city centre, so it's a really built-up area. The pavements are very narrow. I tried to go for a run when the gyms had closed and it just isn't possible here without running in the road and nearly getting run over (Female, aged 30–34).

Making shared spaces safe

Some participants reported feeling comfortable and safe when accessing public spaces because venues were ‘monitoring how many people are coming in’, had ‘lots of sanitizers’, had marked ‘the floor with the two metre spaces’, had ‘implemented one-way systems’, and were enforcing people to ‘wear masks on the premises’. For other participants, however, these measures were experienced as confusing, counterproductive, absent, or ineffective.

They've added in these arrows, and half the people don't look at the arrows. They really don't care. And then half the people are caring about the arrows. So, it makes it completely pointless (Female, aged 30–34).

For a small number of participants, these additional measures were experienced as an annoyance and therefore acted as a deterrent for going out.

I just walked through a department store, and she says oh no you walked through the wrong way … and then there are arrows everywhere. I don't find anything pleasurable about that kind of experience. I'd rather just stay at home than go through all that (Male, aged 45–49).

Parents specifically reported challenges in socially distancing both for their children when they returned to the classroom and also when collecting their children from school:

The school implemented: you come in one gate and you go out the other gate, but that just meant that at the times people were coming in and going out, everybody was all bunched up really closely together rather than spreading out over certain exits and entrances (Female, aged 35–39).

Social Opportunity

Compliance behaviours were influenced by the views and behaviours of participant's social networks, as well as the observed behaviour of the public. The availability of practical support was a facilitator for compliance to guidance around self-isolation and the government's ‘stay at home’ campaign.

Influence of others

Influence of peers

A number of participants described the importance of friends and family who ‘were on the same page’ in following the social distancing guidelines. This was perceived as reinforcing in times of uncertainty.

We all have the same gripes and grumbles and values and outlook so it probably has helped reinforce what I naturally feel and naturally would do (Female, aged 40–44).

Some participants also described the importance of listening to other people's preferences which in turn influenced their own behaviour. For some young people, however, respecting their friends’ decisions sometimes reinforced engagement in behaviours that bent or broke the rules.

So it really depends who I'm meeting up with. I've got a very big divide between my group of friends. But yes, I'm kind of comfortable as long as my friends are comfortable being in closer proximity now (Female, aged 20–24).

For others, particularly young people, peer pressure from friends or family to socialise led to them bending the rules and this was sometimes described as a source of discomfort.

If you're the one who's sat out … then you don't get as much social contact, really. Just feel a bit pressured at the end to move in closer … It was just a bit uncomfortable, really because you want to stop the virus from spreading and I can imagine there were lots of people there as well, who were feeling exactly the same way, but it was social conformity (Male, aged 18–19).

For some participants, perceived pressure from others to comply with the rules or fear of being judged or criticised by others if they were seen to be breaking the rules influenced their compliance.

Had someone text round to say, ha ha, I broke the lockdown, I did this, there wouldn't have been praise for that, people might have criticised them or been negative towards them. So I suppose certainly keeping myself safe, keeping other people safe but also really feeling there was a social expectation to do so and not wanting to break that (Female, aged 35–39).

For people with physical health conditions, explaining to loved ones that they were shielding or uncomfortable with social contact became increasingly difficult as the pandemic continued. Some counteracted this discomfort by avoiding certain friends or family members.

We've got friends that get a bit over enthusiastic and there's a few people that we know that we wouldn't dare go anywhere near at the moment because we know they'd just forget and start hugging people (Male, aged 60–64, physical health condition).

Observing the public's behaviour

Participants described observing other people's behaviour within their local communities with mixed perceptions. For some, particularly older adults or those living in smaller rural communities, participants described the public respecting the rules and keeping a safe space from one another.

There's the 2 m distance, which most people are very, very good about. We do stop and talk to people that we know, but we will always stay a couple of metres away. Everyone is being absolutely brilliant about that actually (Male, 45–49).

For others, particularly those living in urban areas and parents during school pick up times, observations of the public's behaviour were less favourable. ‘Other people’ were described as a reason for not being able to socially distance. This resulted in feelings of anger and frustration and admissions that observing others breaking the rules influenced a reduction in compliance or increased the temptation to break the rules.

It was a little bit galling to see neighbours with their families popping in and out. And yet we're not in that position and if our families had been nearby maybe that temptation would've been huge (Female, aged 35–39).

Availability of practical social support

A key facilitator for following the social distancing guidelines was the availability of practical support for accessing food or medication. This support came in many forms including online food shopping and deliveries, local shop and pharmacy delivery services, local council initiatives, government food packages (set up in response to the pandemic), as well as support from friends and family.

We have a local group that will pick up prescriptions, and also deliver food, as well. I've been pretty firmly self-isolated, yes, and I continue to remain that way (Male, aged 80–84).

For some participants however, online shopping was impossible to organise due to high demand for delivery slots. Parents, in particular, found adhering to the guidelines difficult either because they had to regularly provide food for their family and were therefore unable to minimise visits to the shops, or because they were unable to access practical support during times of self-isolation when a member of the family was unwell.

Because I've got four children … so, we had to go shopping every single day without fail…a loaf of bread lasts one day, milk lasts one day. So, because there was limits on things, we had to go every single day to the shops, which felt really wrong because it felt like we were doing the wrong thing. But we also had to do it because it was essential (Female, aged 30–34).

Capability

Psychological Capability

When social distancing information and resources were perceived as confusing or conflicting, this created a psychological barrier to compliance. In contrast, access to clear advice from trusted sources acted as a facilitator for compliance. A small number of participants described times where they had seemingly misinterpreted the social distancing guidelines or that some of the control measures had led to a false sense of security and reduced their compliance. For others, the length of time that social distancing measures were in place acted as a barrier to remembering to follow the social distancing rules either due to forgetting or reduced risk perception over time.

Inconsistent rules

When government social distancing rules were simple and consistently applied to the UK population (e.g. in times of national lockdown or when clear guidance was issued to people who were clinically vulnerable to stay at home), participants described finding the advice easier to follow. When the rules began to be relaxed following the first lockdown, for example when different rules were introduced within different parts of the UK or when the rules were tightened in response to the evolving situation, many participants described ambiguity, confusion, and being unable to keep up.

Since they've started changing it, god knows. Nobody's got a clue. It changes every day, because ministers have got to stand up and have something to announce, so how would anybody know? There's no time for it to embed (Female, aged 65–69).

Some participants found the language used by the government to describe different elements of social distancing confusing, with terms such as ‘stay alert’ being described as ‘too vague’ and confusion over distinctions such as ‘shielding’ and ‘self-isolating’ making it ‘hard sometimes to know what is meant by what term’ and therefore what they should do.

It infuriates me as somebody who works in education, the style of communication that we received from the government. Often messages that are full of difficult vocabulary, idioms, colloquialisms, that I suspect quite a lot of first-language speakers of English wouldn't always follow, let alone speakers of other languages (Female, aged 34–39).

For some participants, elements of the government guidance were experienced as contradictory, leaving people feeling unable to carry out appropriate behaviours. For example, people with health conditions were advised to shield, but people whom they lived with ‘can carry on as normal and we can't … that doesn't make sense to me’. Similarly, for parents of young children, this conflict was often described in the context of children having to follow more relaxed rules in school compared to outside of school, which in turn meant that parents did not feel their own strict compliance was necessary, leading to them taking a more relaxed approach to social distancing.

I think there is a sense that because kids have been allowed to go to school, it's almost like well, they are allowed to spend the day with however many other kids. So, I think there is a little bit of turning a blind eye or ignoring the detail of that rule from me and the people we see (Female, aged 40–44).

Informational support

In contrast to the barrier of inconsistent rules, participants described seeking out and following advice and prompts from external sources to increase their understanding of the rules. These sources included friends, family, and health professionals, as well as the government and scientific advisors. This approach was particularly mentioned by people who reported trying to weigh up the risks of participating in specific activities once lockdowns eased.

I've got one friend who knew the rules better than I did at one point, because I was not thinking about it. And she was, we can't do that …. and that's how complicated it got (Female, aged 40–44).

For those with existing health conditions and older adults told to shield, healthcare professionals were a valuable and trusted source of advice, and often provided simple, clear instructions with little room for interpretation.

And I think the other part of that for me is that my mum and my girlfriend are both following the same advice that I follow, which for now has been super easy because everyone medically, all my doctors are saying, just don't go near anyone. We can do that. That's easy (Male, aged 35–39).

Some participants actively sought out scientific advice and often found this easy to follow, reassuring and memorable, particularly when it contained interesting facts or instructions.

There was an expert on one of the programmes that said that the best way to think of it was to act as if you've got it. And you're trying not to give it to anybody else, and if everybody does that then it should help. And so I was quite conscious of that at the time (Male, aged 45–49).

For those shielding because of health conditions, being able to reference the government advice was helpful for reinforcing their decision to strictly adhere to the guidelines to family and friends.

There's a social pressure of other people who don't expect you to be following it, so the fact that it was government advice definitely helped with that. It helped me to be able to say to other people, no I'm shielding I can't come and meet you to do that, or you can't come round. So that officialness has helped me reinforce that message to other people (Female, aged 40–44, physical health condition).

Unintended consequences of control measures

A small number of participants described specific virus control measures as counterproductive. The concept of test and trace was used by some participants to socialise with their close contacts without distancing, because if someone contracted the virus, they would be able to inform one another and self-isolate.

My thinking is that if it's somebody who has always been in our close circle and we can trace them and we know what they are up to and they know what we are up to, then the social distancing doesn't necessarily happen (Female, aged 40–44).

For some participants, particularly young adults, wearing a mask mitigated the perceived need to maintain social distancing.

I think the introduction of the mask is another component which makes that distance maybe a bit less stark, so you put a mask on to compensate (Female, aged 20–24).

Wearing-off effect

Most participants described following the social distancing guidelines in the early stages of the pandemic when the first lockdown was announced, however some reported that the longer the restrictions continued, the less likely they would be to continue to comply due to fatigue.

Now I think a lot of people including myself have fatigue and even though we know we shouldn't we kind of started toeing the boundaries just because it kind of feels like this should be over by now even though it obviously isn't (Male, aged 20–24).

Other participants described ‘adapting’ or ‘adjusting’ their behaviours and ‘becoming more comfortable with it’ or ‘forgetting’ about the social distancing rules as time went on.

I think everyone's relaxed a little bit. You get used to it, don't you? A little bit like a soldier on the battlefield. When they first go into it it's absolutely terrifying, but after a while the senses are dulled somewhat, and you get used to the fact that there's this risk floating over you (Male, aged 45–49).

Discussion

Participants identified a range of barriers affecting their compliance with UK social distancing guidelines, including inconsistent messaging, practical and emotional caring responsibilities, feelings of fatigue and reduced perceptions of risk over time, the need to access emotional support, and control measures leading to a false sense of security. Facilitators for compliance included advice and prompting from trusted sources and feelings of civic duty. The majority of identified themes were dependent on participant experiences and circumstances as to whether they acted as a barrier or facilitator to compliance. These included environment and shared spaces, beliefs about the consequences of non-compliance, influence of peers, family and the public, availability of practical support, and lack of trust in government. Reflective motivational factors largely drove compliance behaviours, with psychological capability and social opportunity also important influencers. Factors related to automatic motivation, physical opportunity and physical capability were less frequently described.

Our findings are consistent with previous research, which identified lower compliance in people with caring responsibilities (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021b), younger adults (Coroiu et al., Reference Coroiu, Moran, Campbell and Geller2020; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021a), and physically healthy individuals (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021c). However, our study helps to explain why these groups may have been less likely or able to comply. For example, younger and healthy adults perceived their risk of serious illness from catching COVID-19 as low, which, for some, influenced reduced compliance. Younger people were also more likely to describe the need to access emotional support as a reason for breaking social distancing guidelines. Our findings also provide support to previous qualitative work conducted with specific groups (Denford et al., Reference Denford, Morton, Lambert, Zhang, Smith, Rubin and Yardley2021) and in the early stages of the pandemic (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Armitage, Tampe and Dienes2020), which identified lack of trust in government and unclear communication of guidelines as barriers to compliance, as well as the need to protect vulnerable people as a facilitator. Perceptions of risk of illness from COVID-19 have also been previously reported as a facilitator for compliance (Coroiu et al., Reference Coroiu, Moran, Campbell and Geller2020; Dryhurst et al., Reference Dryhurst, Schneider, Kerr, Freeman, Recchia, van der Bles and van der Linden2020) and our findings highlight that these perceptions operated at three levels; risk to self, risk to immediate family or friends, and risk to the public. It is also plausible that the factors identified in our work interact, for example, advice and information on reducing virus transmission from a trusted source may lead to increased perceptions of risk, which in turn may increase compliance (Dryhurst et al., Reference Dryhurst, Schneider, Kerr, Freeman, Recchia, van der Bles and van der Linden2020).

Our findings also align with previous work on how social factors can be used to understand behaviours in national emergencies (Bavel et al., Reference Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara and Willer2020) and lead to health outcomes more generally. First, social cohesion has been identified as an important facilitator for collective self-organisation, occurring as a result of shared experience in the face of adversity (Drury, Reference Drury2018; Drury, Cocking, & Reicher, Reference Drury, Cocking and Reicher2009). Participants in our study described a sense of social responsibility to others as a motivating factor for compliance. However, this was sometimes undermined by perceptions that others were not following the rules. Second, there is an established body of evidence supporting the relationship between social support and improved health outcomes (Reblin & Uchino, Reference Reblin and Uchino2008; Umberson & Karas Montez, Reference Umberson and Karas Montez2010). Our study lends support to this relationship, specifically in the context of compliance behaviours. Participants highlighted the importance of social distancing advice and prompting from family and friends (informational support) for following the rules, the provision of essential items to enable vulnerable people to self-isolate or shield (practical support) and, conversely, the need to access emotional support as a barrier to compliance. Third, social conformity and peer pressure have been identified as a driver for increased compliance during the pandemic (Tunçgenç et al., Reference Tunçgenç, El Zein, Sulik, Newson, Zhao, Dezecache and Deroy2021). However, our research also highlighted the potential negative influence of peers, particularly among some young people who described conforming in social situations that were not conducive to social distancing. Previous work also suggests that people underestimated the risk of interacting with ingroup members during the COVID-19 pandemic because they trusted them more (Cruwys et al., Reference Cruwys, Stevens, Donaldson, Cárdenas, Platow, Reynolds and Fong2021).

While there is evidence that limited access to outside space negatively impacted mental health during the pandemic (McCunn, Reference McCunn2020), the influence of the environment on people's ability to comply with social distancing guidelines has been explored less by comparison. People living in urban environments have reported lower compliance than those in rural communities (Fancourt, Bu, Mak, Paul, & Steptoe, Reference Fancourt, Bu, Mak, Paul and Steptoe2021) and our findings offer new insights into the challenges associated with navigating shared living spaces, particularly for groups identified as clinically vulnerable, and in busy urban environments, even when shops and entertainment venues attempted to implement measures designed to support social distancing.

The concept of behavioural fatigue has been challenged by researchers as poorly defined, lacking empirical evidence (Harvey, Reference Harvey2020; Michie, West, & Harvey, Reference Michie, West and Harvey2020), and was perceived as controversial when used at the start of the pandemic to justify delaying lockdown (Mahase, Reference Mahase2020). Longitudinal studies have, however, identified a reduction in compliance over time (Petherick et al., Reference Petherick, Goldszmidt, Andrade, Furst, Pott and Wood2021), albeit in a minority of people (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Steptoe and Fancourt2021c). Similarly, a small number of participants in our study, particularly parents, people with physical health conditions and younger adults described a reduction in compliance due to fatigue. However, participants predominantly described a range of other reasons for reduced compliance, including seeing figures in positions of authority breaking the rules echoing previous research (Fancourt, Steptoe, & Wright, Reference Fancourt, Steptoe and Wright2020), forgetting the rules over time and a dilution of perceived threat of the virus over time. As such, our results do not necessarily suggest that fatigue itself is a driver of declines in compliance behaviour.

Finally, this study highlighted the issue of individuals deciding on what constituted safe behaviours themselves rather than following official guidance. The occurrence of ‘risk compensation’ (Peltzman, Reference Peltzman1975) hypothesises that individuals may offset one risk-reducing behaviour with another risky behaviour and has been influential in debates during COVID-19 such as whether to make the wearing of masks in public places compulsory (Mantzari, Rubinv, & Marteau, Reference Mantzari, Rubin and Marteau2020). Our study highlights that such risk compensations did occur among a minority of participants, including mask wearing mitigating the perceived need to keep distance from others, as well as track and trace being identified as a safety net for people known to one another to meet in person. However, further research is needed to determine whether such risk compensation has a major impact on virus transmission or whether the trade-offs that individuals make do still help to reduce transmission.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the largest in-depth qualitative study to explore reasons for compliance with UK social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected across different stages of the pandemic, enabling capture of a range of experiences as restrictions were eased, adapted, and tightened. Single interviews are limited in capturing potentially fluctuating compliance to guidelines over time, but we did ask participants to reflect on their compliance behaviours at different stages of the pandemic. We conducted video call or telephone interviews and predominantly recruited people using online methods such as social media, websites, and electronic newsletters. While this enabled us to disseminate information about the study widely across the UK and collect data safely amid restrictions, it also may have meant that those without access to the internet were excluded from taking part. Some participants may have felt social pressure to provide socially acceptable answers and may have been reluctant to talk about instances of reduced compliance with the guidelines. Previous research also suggests that participants may be more likely to exhibit social desirability bias when being interviewed via telephone as opposed to face-to-face (Holbrook, Green, & Krosnick, Reference Holbrook, Green and Krosnick2003). While we were unable to compare social desirability responses in telephone versus video call interviews in our study, participants did report both barriers and facilitators to their compliance behaviours across the interviews we conducted, suggesting an overall willingness to discuss non-compliance.

There are also some important limitations to our sample; we did not collect socioeconomic status of participants, and most participants (63%) were not currently working, with the majority of those who were, being supported to work remotely or flexibly when restrictions were relaxed. It is important to acknowledge the influence of the in-person working environment on people's ability to comply with the rules and in a concurrent study exploring the impact of the pandemic on wellbeing among non-healthcare key workers, participants described several environmental challenges to social distancing in the workplace. These included an initial lack of personal protective equipment, inadequate cleaning practices and working in confined spaces that were not conducive to maintaining distance between colleagues (May, Aughterson, Fancourt, & Burton, Reference May, Aughterson, Fancourt and Burton2021).

Implications for Policy and Practice

We identified a number of barriers as well as factors that facilitated compliance with social distancing guidelines that could be used to guide future pandemic-related policy decisions and interventions. Our results suggest that interventions should be designed primarily to increase and maintain individual motivation to comply, alongside emphasising collective action (Carter, Drury, Rubin, Williams, & Amlôt, Reference Carter, Drury, Rubin, Williams and Amlôt2015). Participants told us that government messaging was most effective when it was clear, concise, and focused on the wider societal impact of individual compliance behaviours. Providing examples of people within local communities complying with the rules and praising the public for following the rules may also encourage others to follow and reduce the impact of negative peer pressure (Andrews, Foulkes, & Blakemore, Reference Andrews, Foulkes and Blakemore2020).

Beliefs about the consequences of the virus was a key driver for compliance, therefore social distancing recommendations could incorporate more direct messaging about the risk and consequences of infection, particularly among younger adults. Research suggests, however, that while effective in some scenarios, inducing fear to encourage compliance may lead to defensive reactions if people do not feel confident or able to deal with the threat (Witte & Allen, Reference Witte and Allen2000). Messaging about risk, therefore, also needs to be accompanied by clear and consistent advice and instruction from trusted sources (e.g. scientific advisors, healthcare professionals). Insights from pandemic responses in countries where infection rates have so far been brought under control suggest that their success was, in part, due to visible leadership guided by scientific expertise which resulted in public trust in government and a collective response (Wilson, Reference Wilson2020).

We identified a need for tailored interventions to enable people in particular circumstances or with specific responsibilities to comply with social distancing rules. For those with caring responsibilities or those living alone or who required emotional support, the initial guidelines may have been too restrictive, resulting in bending or breaking of the rules. Our findings also suggest that parents, people with health conditions and young people may be at particular risk of experiencing pandemic fatigue. Strategies that minimise harm among these groups such as allowing people to socialise in small groups and acknowledging the hardship that people may be experiencing as well as providing appropriate emotional, financial, and social support opportunities may help to reduce fatigue among populations (World Health Organisation, 2020). The introduction of support bubbles, whereby individuals living alone or parents with young children were able to form an extended household with one other person or family, were described as a lifeline for many who were struggling with their mental health (Burton et al., Reference Burton, McKinlay, Aughterson and Fancourt2020; Dawes et al., Reference Dawes, May, McKinlay, Fancourt and Burton2021), suggesting that this intiative should continue to be implemented and prioritised if social distancing restrictions continue. Finally, the environments in which people live and the public spaces that people use need to be made as amenable as possible to social distancing. Clear signposting and messaging within these environments, as well as the enforcement of basic social distancing rules by organisations and services is required.

Conclusion

Our study provides an in-depth understanding of why individuals found it challenging or easy to comply with government social distancing rules during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through mapping the responses to a behaviour change framework, this study has identified a range of factors that could be used to inform government communication strategies and public health measures to improve compliance. While some of these factors depended on individual circumstances as to whether they were experienced as a barrier or a facilitator, reflective motivation was clearly an important driver for future compliance behaviours, as were psychological capability and social opportunity. Interventions to encourage compliance should consider the provision of practical, emotional, and informational support to drive behaviour change, alongside strategies that maintain motivation to comply and optimise feelings of social cohesion.

Acknowledegments

We would like to thank Dr Louise Baxter for support with recruitment and interviews and Dr Rana Conway, Henry Aughterson, and Sara Esser for conducting participant interviews. The research team are also grateful for the support of a number of organisations with their recruitment efforts including the McPin Foundation, Alzheimer's Society, Age UK, HealthWise Wales, Arts Beyond Belief, Taraki, NCRI Consumer forum, Third Aid Project, Yorkshire Cancer Community, Asian Women Cancer Group, Asthma UK, and MQ, and to all of the participants who took part in the study.