Guerrilla: One who engages in irregular warfare especially as a member of an independent unit.

—Webster’s New College Dictionary

Thank you to the Gaus selection committee, my nominators, and APSA for this honor. I have used this opportunity to reflect on my career interest in “guerrilla government.” “Guerrilla government” is my term for the actions of public servants who work against the wishes—either implicitly or explicitly communicated—of their superiors. Footnote 1

“Fire the bastard!” I can still hear my boss yelling at me, instructing me to get rid of my most creative and passionate employee. I was 28 years old and the director of policy and planning for a state environmental agency, managing a staff of 50. My employee, earnestly dedicated to environmental concerns, had turned into a “guerrilla,” working clandestinely with environmental groups and the media, leaking data, and showing up at night-time public hearings blasting the governor and my boss for “caveman-era water policies.” He was seeking to accomplish outside the organization what he could not accomplish within the organization.

Guerrilla government is a form of dissent that is usually carried out by those who are dissatisfied with the actions of public organizations, programs, or people, but typically, for strategic reasons, choose not to go public with their concerns in whole or in part. A few guerrillas—like Edward Snowden—end up outing themselves as whistle-blowers, but most do not. Rather than acting openly, guerrillas often choose to remain “in the closet,” moving clandestinely behind the scenes, salmon swimming upstream against the current of power. Over the years, I have learned that the motivations driving guerrillas are diverse. Their reasons for acting range from the altruistic (doing the right thing) to the seemingly petty (I was passed over for that promotion). Taken as a whole, their acts are as awe inspiring as saving human lives out of a love of humanity and as trifling as slowing the issuance of a permit out of spite or anger. Guerrillas run the spectrum from anti-establishment liberals to fundamentalist conservatives, from constructive contributors to deviant destroyers. Guerrilla government is about the power of bureaucrats; the tensions between career public servants and political appointees, organization culture, and what it means to act responsibly, ethically, and with integrity in a public setting.

Most guerrillas work on the assumption that their actions outside their agencies provide them a latitude that is not available in formal settings. Some want to see interest groups join, if not replace, formal government as the foci of power. Some are tired of hardball power politics and seek to replace it with collaboration and inclusivity. Others are implementing their own version of hardball politics. Most have a wider conceptualization of their work than that articulated by their agency’s formal and informal statements of mission, but some are more freewheeling, doing what feels right to them. Some are committed to a particular methodology, technique, or idea. For some, guerrilla activity is a form of expressive behavior that allows them leverage on issues about which they feel deeply. For others, guerrilla activity is a way of carrying out extreme viewpoints on pressing public policy problems.

Guerrillas bring the credibility of the formal, bureaucratic, governmental system with them, as well as the credibility of their individual professions. They tend to be independent, multipolar, and sometimes radical. They often have strong views that their agency’s perspective on public policy problems is at best insufficient, at worst illegal. They are not afraid to reach into new territory and often seek to drag the rest of the system with them to explore new possibilities.

At the same time, guerrillas run the risk of being unregulated themselves. Sometimes they fail to see the big picture, promoting policies that may not be compatible with the system as a whole. Sometimes they are so caught up in fulfilling their own expressive and instrumental purposes that they may not fulfill the purposes of their organization. This is the dilemma of guerrilla government.

THREE THEORETICAL LENSES

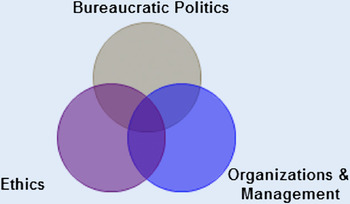

The great thinkers in the social sciences have for years grappled with guerrilla government under very different labels and in very diverse ways. There are three major theoretical lenses or vantage points from which to view guerrilla government that emerge from the social science literature; each offers a different type of understanding. The three lenses are bureaucratic politics, organizations and management, and ethics (see figure 1).

Figure 1 Guerrilla Government Theoretical Lenses

Bureaucratic Politics

The bureaucratic politics literature is vast and spans several decades. The key points about bureaucratic politics are that career public servants make policy through the exercise of discretion (Appleby Reference Appleby1949), and that public administration is a political process (Appleby Reference Appleby1949; Cleveland Reference Cleveland1956; Key Reference Key1958; Stein Reference Stein1952; Derthick and Quirk Reference Derthick and Quirk1985; Carpenter Reference Carpenter2001; Reference Carpenter2010). Moreover, bureaucrats and bureaucracy are driven by their own highly particularized and parochial views, interests, and values (Long Reference Long1949), and bureaucrats’ views tend to be influenced by the unique culture of their agencies (Halperin and Kanter Reference Halperin and Kanter1973). All bureaucracies are endowed with certain resources that career public servants may use to get their way: policy expertise, longevity and continuity, and responsibility for program implementation (Rourke Reference Rourke1984). Agencies and bureaucrats within agencies often seek to co-opt outside groups as a means of averting threats (Selznick Reference Selznick1949).

Two relevant literatures with different twists consist of writings on policy entrepreneurs and the politics of expertise. Policy entrepreneurs are “advocates who are willing to invest their resources—time, energy, reputation, money—to promote a position in return for anticipated future gain in the form of material, purposive or solitary benefits” (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2003, 179). Riccucci (Reference Riccucci1995) focused on “execucrat” policy entrepreneurs—career public executives who made a difference.

Guerrilla government is a mutant cross-pollination of policy entrepreneur and the politics of expertise. The politics of expertise is a term used by Benveniste (1973), who examined why and how experts influence public and private policy. In an argument reminiscent of the one that knocked down the politics–administration dichotomy, Benveniste contended that so-called neutral experts (in the planning field in his study) are in fact involved in politics, and that “politics is never devoid of ideological content” (1973, 21). It is time to “shed the mask” of neutrality, Benveniste argued, and for professional public servants to admit that they are both experts and committed political actors.

Lewis phrased the same sentiment in a different way:

Among the many resources employed by public bureaucracies, professionalism and expertise are particularly significant…. When coupled with the ancient notion of the primacy of the state, they make for a formidable source of power. (1977, 158)

Lewis went on to point out that with this expertise comes specialized knowledge, professional norms, and prolonged attention to issues that outlive the attention that others in the political process can give. Hence, professionalized public bureaucrats have a capacity to initiate and innovate that is unparalleled in the political system.

Three great works spanning three different decades have tried to grapple intellectually with the dilemma of guerrilla government in three very distinctive ways. Kaufman in The Forest Ranger concluded, among other things, that despite attempts to forge a tightly run Forest Service and a nearly all-obeying forest ranger, “[i]n the last analysis all influences on administrative behavior are filtered through a screen of individual values, concepts, and images” (1960, 223). Hirschman in Exit, Voice and Loyalty (1970) outlined a typology of responses to dissatisfaction: exit (leaving, quitting, or ending the relationship), voice (expressing one’s dissatisfaction), and loyalty (faithfully waiting for conditions to improve). Farrell (Reference Farrell1983) added a fourth element to Hirschman’s work: neglect. Lipsky in Street Level Bureaucracy (1980) analyzed the actions and roles of “frontline” public servants, such as police officers and social workers, and argued that they are essentially policy makers. This phenomenon is built on two interrelated facets of their positions: relatively high degrees of discretion and relative autonomy from organizational authority.

These are just a few of the points made in the bureaucratic politics literature that are relevant to an examination of guerrilla government. The bureaucratic politics lens raises important questions concerning who controls government organizations; the accountability of public servants; the roles, responsibility, and responsiveness of bureaucrats in a democratic society; and the tensions between public servants and political appointees.

The bureaucratic politics lens raises important questions concerning who controls government organizations; the accountability of public servants; the roles, responsibility, and responsiveness of bureaucrats in a democratic society; and the tensions between public servants and political appointees.

Organizations and Management

Classic organization theorists such as Cyert and March (Reference Cyert and March1963), Emery and Trist (Reference Emery and Trist1965), Katz and Kahn (1966), Thompson (Reference Thompson1967), Lawrence and Lorsch (Reference Lawrence and Lorsch1969), and Aldrich (Reference Aldrich and Negandhi1972) all maintained that organizations both are shaped by and seek to shape the environment in which they exist. This “open systems” approach to understanding organizations maintains that organizations are in constant interaction with their environments, that organization boundaries are permeable, and that organizations both consume resources and export resources to the outside world. In other words, organizations do not exist in a vacuum.

This notion contrasts with traditional theories that tend to view organizations as closed systems, resulting in an overemphasis on the internal functioning of an organization. While the internal functioning of an organization is significant and cannot be ignored, it is essential to remember that all organizations “swim” in often tumultuous environments that affect every level of the organization. The open systems perspective is important when analyzing public organizations, and it is especially important when thinking about guerrilla government. Public organizations, such as those profiled in my research, seek to thrive in environments that are influenced by the concerned public, elected officials, the judiciary, interest groups, and nongovernmental organizations, to name just a few. Working with, and being influenced by, individuals and groups outside one’s organization has long been a fact of life for public servants (Brownlow Reference Brownlow1955; Gaus Reference Gaus1947; Stillman Reference Stillman2004; Wildavsky Reference Wildavsky1964). The modern offshoot of the open systems perspective is that of networked governance (Provan and Milward Reference Provan and Milward1995; O’Toole Reference O’Toole1997; Agranoff Reference Agranoff, Kamensky and Burlin2004; Agranoff and McGuire Reference Agranoff and McGuire2001).

Ethics

Ethics is the study of values and how to define right and wrong action (Cooper Reference Cooper2001; Reference Cooper2012; Menzel Reference Menzel1999; Van Wart Reference Van Wart1996). Scholars have analyzed personal ethics (Bowman and Wall Reference Bowman and Wall1997; Nieuwenburg Reference Nieuwenburg2014; Lavena Reference Lavena2016), organizational ethics (Zajac and Comfort Reference Zajac and Comfort1997; Van Der Wal Reference Van Der Wal2011; Andersen and Jakobsen Reference Andersen and Jakobsen2016); professional ethics (Cooper Reference Cooper2004; Christensen and Laegreid Reference Christensen and Lægreid2011; Fattah Reference Fattah2011; Menzel Reference Menzel2015; Peffer Reference Peffer2015; Downe, Cowell, and Morgan Reference Downe, Cowell and Morgan2016; Weimer and Vining 2016), regime values (Rohr Reference Rohr1988; Piotrowski Reference Piotrowski2014); and public service ethics (Bowman and Wall Reference Bowman and Wall1997; Brewer and Selden Reference Brewer and Selden1998; King, Chilton, and Roberts Reference King, Chilton and Roberts2010; Dur and Zoutenbier Reference Dur and Zoutenbier2014; Caillier 2015; Stazyk and Davis Reference Stazyk and Davis2015; Wright, Hassan, and Park Reference Wright, Hassan and Park2016).

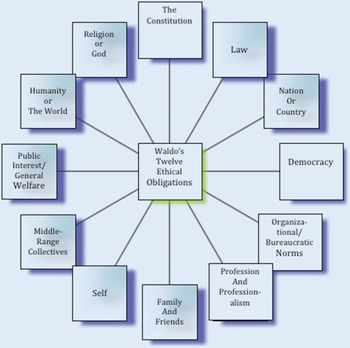

Waldo (Reference Waldo1988) offered a map of the ethical obligations of public servants, with special reference to the United States. His map is still relevant today, and it is especially applicable to the issue of guerrilla government. In his map, Waldo identified a dozen sources and types of ethical obligations, but cautioned that the list is capable of “indefinite expansion” (1988, 103), and that the obligations do not lend themselves to any prioritization.

Waldo’s 12 ethical obligations are presented in figure 2. The message of Waldo’s map of ethical obligations is that different public servants will be compelled by different ethical obligations. This makes iron-clad conclusions about whether guerrillas are right or wrong difficult at times. Compounding this analytical challenge is the “problem of ambiguity” in making ethical determinations (Cooper Reference Cooper2012; Dobel Reference Dobel1999; Fleishman Reference Fleishman, Fleishman and Moore1981; Rohr Reference Rohr1988).

Figure 2 Waldo’s Map of the Ethical Obligations of a Public Servant

SOURCES OF DATA AND METHODS

How does one study guerrilla government? I spent a year studying how scholars have pursued other “elusive subjects”—hidden populations that are hard to reach, where public acknowledgement of being part of the population is potentially threatening. I analyzed research on crack dealers, deviance in business organizations, sexual networks, HIV transmission, cigarette black markets in prisons, employee theft, workplace revenge, employee deviance, pirated goods, deception in weapons testing, unreported economy, and tax non-compliance. From these studies I gleaned and combined the following methods to study most of my guerrilla government cases: participant observation, structured interviews, unstructured interviews, stories people tell, self-completion surveys, and published sources.

EXAMPLES OF PREVIOUS CASES OF GUERRILLA GOVERNMENT

My research has detailed several case studies of guerrilla government. (For a more detailed treatment, see O’Leary Reference O’Leary2014). Consider the following:

-

• Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat stationed in Nazi Lithuania during World War II who clandestinely signed an estimated 10,000 visas to save the lives of Jewish refugees.

-

• Mark Felt, the second in command in the Federal Bureau of Investigation in the 1970s, whose secret leaks to reporters exposed the Watergate scandal and eventually brought down President Richard M. Nixon.

-

• The “Nevada Four,” three scientists from the US Department of the Interior and one from the Nevada Department of Wildlife, who successfully got a bill passed through Congress to dedicate water to the Nevada wetlands, legislation against which their superiors testified.

-

• Scientists in the Seattle Regional office of the US Environmental Protection Agency under the presidency of Ronald Reagan, who plotted a unified staff strategy behind the backs of political appointees and failed to implement orders with which they disagreed.

-

• Claude Ferguson, a ranger with the US Forest Service, who promoted and joined a lawsuit filed by environmentalists against his own agency because it allowed off-road vehicles in the Hoosier National Forest.

TWO NEW CASES OF GUERRILLA GOVERNMENT

Two newer cases of guerrilla government challenge my previous analyses and present a different side of guerrilla government: the cases of Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning and Edward Snowden. I will only briefly overview the Manning case here, since it is presented in detail in my 2014 book. And while I present more detail about the Snowden case in this article, it will be profiled in depth in the forthcoming 3rd edition of my book.

The Manning Case

US Army Private Bradley Manning leaked hundreds of thousands classified government documents to WikiLeaks. A brilliant high school student, a talented computer hacker, and a community college dropout, Manning joined the army in 2007 hoping to earn a PhD in physics through the GI bill. He was sent to Forward Operating Base Hammer near Baghdad in Iraq where he encountered massive quantities of sensitive information while on the job—some of it in classified databases not directly related to the mission of his unit. Manning later explained that in these databases he:

Saw incredible things, awful things … things that belonged in the public domain, and not on some server stored in a dark room in Washington D.C. . . . .A database of half a million events during the Iraq war … explaining how the first world exploits the third, in detail (Manning IM to Adrian Lamo, May 2010).

But it was a video that Manning found in the Judge Advocate’s online top secret directory of a July 12, 2007, Baghdad airstrike that was particularly disturbing to him. The video showed a US military helicopter firing on a group of men in Baghdad. One of the men was a journalist, and two other men were Reuters employees carrying cameras that the pilots mistakenly thought were anti-tank grenade launchers. The soldiers in the helicopter also fired on a van that stopped to help the injured members of the first group. In this second attack two children in the van were wounded and their father was killed. (This video may be viewed at www.collateralmurder.com.)

Manning downloaded hundreds of thousands of files on a compact disc, avoiding detection by keeping a serious face while humming and lip-synching “to Lady Gaga songs to make it appear that he was using the classified computer’s CD player to listen to music” (Shanker Reference Shanker2010). Soon after Manning returned to Baghdad in February, 2010, WikiLeaks began posting the documents that Manning gave them. Today Manning is serving a 35 year sentence in Leavenworth prison.

The Snowden Case

The second new case that pushes my guerrilla government research in a different direction concerns Edward Snowden who “used the higher-than-top-secret clearances of the user accounts of some top NSA officials” (Toxen Reference Toxen2014) to locate, study, and leak an estimated 1.7 million top secret documents. Snowden had access to these accounts because he created them as part of his job. He even modified these accounts in order to gain access to the data from his home computer.

Snowden, now 33 years old, is the son of civil servants. His father was in the Coast Guard and his mother still works as a clerk for the US District Court in Baltimore. Snowden never completed high school, dropping out in 10th grade, despite being called “brilliant” (Reitman Reference Reitman2013) but eventually received his GED. He has also been called an “IT wiz” and an “IT genius” (Reitman Reference Reitman2013). Like Manning, he went to community college but never completed a degree. Like Manning, he joined the Army at a young age, but was discharged (after breaking both of his legs). His first job after the Army was as a security guard at an NSA facility located at the University of Maryland; he then was hired by the CIA to work on IT security. At age 24, he was stationed in Geneva, Switzerland where he worked with the CIA for three years then took a job as a private contractor working first for Dell, and then for Booz Allen Hamilton, an American management-consulting firm that specializes in technology and security. In 2013, Snowden was located in Hawaii, doing NSA work as a Booz Allen Hamilton employee, when he stole the documents he leaked. He carried this out through several covert actions of deception. An internal NSA memo released on February 10th, 2014, described Snowden’s actions as follows:

A NSA civilian admitted to FBI Special Agents that he allowed Mr. Snowden to use his . . . Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) certificate to gain access to classified information on NSANet: access that he knew had been denied to Mr. Snowden. Further, at Mr. Snowden’s request, the civilian entered his PKI password at Mr. Snowden’s computer terminal. Unbeknownst to the civilian, Mr. Snowden was able to capture the password, allowing him even greater access to classified information. The civilian was not aware that Mr. Snowden intended to unlawfully disclose classified information. (Verble Reference Verble2014, 15).

Snowden worked undetected behind the NSA security wall for three months then used web crawler software to catalog and organize all the information. The documents were stored on a simple USB flash drive, which is banned inside the NSA (Verble Reference Verble2014). Snowden turned all 1.7 million files over to hand-picked “friendly journalists” at the Guardian and the Washington Post—“the most serious compromise of classified information in the history of the US intelligence community” according to former CIA deputy director Michael Morell (Reitman Reference Reitman2013).

Snowden said he leaked the confidential information because he was shocked by excessive NSA surveillance of Americans. In particular, he was stunned by the NSA policy of “Collect it All,” “Process it All,” “Exploit it All” “Partner it All,” “Sniff it All” and “Know it All” where the NSA collected and stored Facebook, Google, telephone call and other internet activity information from nearly all individuals living in the United States. Programs designed for “warfront” were used on “homefront” (Reitman Reference Reitman2013) and NSA lied to Congress about it. “Anyone can spy on just about anyone,” Snowden concluded, through phones, computers, and tablets (Reitman Reference Reitman2013). Snowden, who now resides in Russia to evade prosecution in the United States, has been called a whistleblower, a patriot, a traitor, a leaker, a coward, and a hero.

Snowden, who now resides in Russia to evade prosecution in the United States, has been called a whistleblower, a patriot, a traitor, a leaker, a coward, and a hero.

Before approaching journalists, Snowden studied the case of Private Manning and deliberately chose not to work with WikiLeaks. “I don’t desire to enable the Bradley Manning argument that these were released recklessly and unreviewed,” Snowden later said. “I carefully evaluated every single document I disclosed to ensure that each was legitimately in the public interest. There are all sorts of documents that would have made a big impact that I didn’t turn over, because harming people isn’t my goal. Transparency is” (Reitman Reference Reitman2013).

While Snowden at first worked clandestinely against the wishes of his superiors, eventually he chose to out himself. After passing the data to journalists, Snowden transmitted a video via social media explaining what he did and why. “I have no intention of hiding who I am because I know I have done nothing wrong,” Snowden said in an interview (Greenwald, MacAskill, and Poitras Reference Greenwald, MacAskill and Poitras2013). Defending his actions, Snowden cited Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “I believe in the principle declared at Nurenberg in 1945: ‘Individuals have international duties which transcend the national obligations of obedience.’ Therefore individual citizens have the duty to violate domestic laws to prevent crimes against peace and humanity from occurring” (Tavani and Grodinsky Reference Tavani and Grodzinsky2014, 10).

Snowden also cited the US Constitution: “The 4th and 5th Amendments to the Constitution of my country . . . forbid such systems of massive, pervasive surveillance. While the U.S. Constitution marks these programs as illegal, my government argues that secret court rulings, which the world is not permitted to see, somehow legitimize an illegal affair” (Tavani and Grodinsky Reference Tavani and Grodzinsky2014).

Comparing the Cases

As mentioned, both Manning and Snowden were college dropouts and low level employees. Both are considered computer “geniuses” who initially largely worked alone as guerrillas. They have been called part of the “post terror generation” (New York Times Editorial Board 2015) with a Gamer’s view of the world (Reitman Reference Reitman2013). They both wanted to beat the bad guys—the US government—through the internet where “the rules do not apply” (Reitman Reference Reitman2013). They both expressed shock at finding information that they thought the world deserved to see.

In contrast, the previous cases of guerrilla government I analyzed all concerned either highly educated or highly placed government administrators, long term career public servants who described themselves as “banging their heads against the wall” for years, unable to change government policy. They all had a sophisticated knowledge of their subject matter, often the bio-physical sciences—but a lack of political knowledge.

So what? big data

One notable and very important factor in the Manning and Snowden cases is the sheer enormity of data they stumbled upon and the relatively easy access they had to those data. This raises several important questions that bridge the traditions of public administration and political science including the following: Has the administrative state become the “national surveillance state”? (Balkin and Levinson Reference Balkin and Levinson2006; Balkin Reference Balkin2008). Have surveillance tools become the new tools of government? Have we created a “culture of intrusion” where we have become “privacy complacent” (Reitman Reference Reitman2013)? (See Kernaghan Reference Kernaghan2014, for a discussion of value conflicts inherent in big data. See Roman Reference Roman2015, for a discussion of e-government ethics.)

So what? hyper social media

Another important factor of the Manning and Snowden cases concerns the use of social media on a global scale. Social media have become both a source of data for the NSA and a source of power of government guerrillas. “Going viral” is now a badge of honor to many. Further, on social media, the guerrilla controls his or her image and message with the focus often being on the heroic individual. Complicating this issue is the fact that there is relatively easy entry and access to social media, without filters and quality control.

So what? contracting out

The Snowden case yields important questions about contractors and guerrilla government. More than 500,000 private contractors have top secret clearance in the United States, and often times other private contractors conduct the background checks on these contractors. As a contractor, Snowden had greater access to top secret documents than he had as a career bureaucrat.

I have written about contractors and guerrilla government previously. In my work on the NASA Return-to-Flight Task Group following the Columbia space shuttle accident (O’Leary Reference O’Leary2014, chapter six) two astronauts leading the commission initially refused to release information to the public that would reflect negatively on NASA. A minority subgroup of which I was a member protested and developed a plan coordinated by a former director of the Congressional Budget Office. The plan was for the contractors who staffed the committee to leak our minority report to the public. They were selected after hours of clandestine discussions because they would be done with their work and gone in a week. At the same time, we spent hours discussing how we would protect the career NASA civil servants. The contractors agreed and even helped develop the plan. (Fortunately the two astronauts changed their mind and the plan was never implemented.) This raises a hypothesis concerning whether guerrilla government activity is more easily implemented by contractors than career civil servants under certain circumstances?

ETHICAL OR INSUBORDINATE?

Taken as a whole, the incidents of guerrilla government profiled in my research illustrate several common themes concerning the power of career public servants that cross policy and temporal lines. The themes also yield implications for public policy, public management, ethics, and governance. The major themes represented in these cases and others like them may be categorized into different harsh realities.

Harsh Reality #1: Guerrilla government is here to stay.

The cases highlighted in my research capture the actions of, and the methods used by, career public servants to affect the policies and programs of their bureaucracies from outside their organizations. These cases present a useful contrast to the stereotype of the government bureaucrat who is interested only in a stable job, few risks, and a dependable retirement. As the classic bureaucratic politics literature so aptly communicates, for better or for worse, bureaucrats and bureaucracies—whether it is your local post office, the state division of motor vehicles, or the US Department of the Interior—are immensely powerful. This is a fact of life in the open systems and open organizations of public management. While the intensity of guerrilla government activities will ebb and flow, guerrilla government itself will never completely disappear.

Harsh Reality #2: Guerrillas can do it to you in ways you’ll never know.

There are as many techniques of guerrilla government as there are guerrillas. Here are a few examples. (For additional examples, see O’Leary Reference O’Leary2014.)

-

• Obey your superiors in public, but disobey them in private

-

• Ghost-write letters, testimony, and studies for supportive interest groups

-

• Fail to correct superiors’ mistakes—let them fall

-

• Neglect policies and directives you disagree with—stall

-

• Fail to implement orders you think are unfair

-

• Hold clandestine meetings to plot a unified staff strategy

-

• Secretly contact members of Congress and other elected officials, as well as their staffs, in an effort to cultivate them as allies

-

• Build public–private partnerships

-

• Build partnerships among entities at all levels of government

-

• Forge links with outside groups: other professionals, nongovernmental organizations, concerned citizens

-

• Cultivate positive relationships with the media; leak information to the media, from informal tips to formal press releases

-

• Cultivate positive relationships with interest groups

These are all methods utilized by dissatisfied public servants to address perceived wrongs and to influence their organizations’ policies about which their superiors might never know.

How does one know when a government guerrilla is a canary in the coal mine who needs to be listened to, or a delusional single-issue fanatic?

Harsh Reality #3: All guerrilla activity is not created equal.

How does one know when a government guerrilla is a canary in the coal mine who needs to be listened to, or a delusional single-issue fanatic? We all know the negative stories of guerrillas within metropolitan police departments whose view of policing are at odds with their department, but believe they are promoting the public interest in crime control.

While it is undeniable that government guerrillas as public servants must be accountable and responsive to the public, it is sometimes difficult to sort out the “ethical” guerrillas from the “unethical” guerrillas, the guided from the misguided. For example, what or who, exactly, is “the public” in these instances? Possible “masters” that a public servant might have include the public as interest group, the public as consumer (of government products), the public as represented by an elected official, the public as client (served by “street-level bureaucrats”), and the public as citizen (Frederickson Reference Frederickson1991).

Even when the outcome of guerrilla government activity is beneficial, the ethics of guerrilla government actions can be difficult to sort out. Take the “Nevada Four”—the three scientists from the US Department of the Interior and one from the Nevada Department of Wildlife, mentioned previously, who led a clandestine environmental war to save the wetlands in the state of Nevada and successfully got a bill through Congress—legislation against which their superiors testified. Did they act in a manner that can be deemed accountable and responsive to the public? Yes and no. All government organizations are to implement the will of the people as mandated by legislation enacted by elected representatives. Yet, in the Nevada Four case, by not being constrained by their agencies’ interpretations of congressional and state will and promoting new wetlands legislation, the Nevada Four promoted innovative policies that, in the end, also must be seen as the will of the people, as they eventually were enacted by Congress and approved by the people of Nevada in a referendum. Both sets of legislation were supported by the public: interest groups, consumers, elected representatives, clients, and citizens. At the same time, both sets of legislation were opposed by differing factions of the same public. Similarly, the Seattle EPA staff were there to serve the public interest, but they also were there to serve the Regional Administrator against whom they fought. In the same fashion, concerned citizens wrote newspapers both condemning and praising Claude Ferguson, the career public servant mentioned previously, who sued the Forest Service.

The latest cases are more challenging to sort out. Many say that Manning and Snowden, who had taken oaths of allegiance to the United States, are traitors to their country. There is no reason, the argument goes, why they needed to leak hundreds of thousands of documents in order to dissent: there were other avenues they could have pursued. Some of the leaked data ended up in the hands of terrorists and countries that are not friendly to the United States. Manning’s leaked documents can be traced to a loss of lives. (See O’Leary Reference O’Leary2014, chapter five for a greater discussion.)

In contrast are those who argue that Manning and Snowden are similar to conscientious objectors, righteously exposing the truth. One political scientist maintains that Snowden in particular is a model of civil disobedience. Likening him to Thoreau, Ghandi, and King, Scheurerman (2014; 2016) maintains that Snowden’s example can help us advance liberal and democratic ideas about what it means to act ethically.

Examining this phenomenon through the lens of Waldo’s 12 competing ethical obligations, it is important to note that the guerrillas I have studied clearly did not see their allegiance, accountability, and responsiveness to their organizations as their first priority. In fact, the comments of the guerrillas I studied make it clear that they consider organizational pressures barriers to “doing the right thing.”

The paradox of this situation can be seen in the fact that the Nevada Four felt they had to “embarrass the government” to achieve their goals, when they were, of course, the government. The Seattle EPA staff felt they had to do an end-run around the government, yet they were the government. Claude Ferguson had to sue the government, when he was in fact part of the government. Bradley Manning felt that he needed to expose the atrocities of war inflicted by the US government, yet he is part of that government: the US Army. Eric Snowden felt he needed to expose the overreach of US government surveillance, yet he did so by overreaching himself, going behind the NSA security wall—at times in his apartment on his home computer—undetected for three months to view and gather data for which he had no clearance. In the end, their commitment can be seen neither to organization, nor to the public as interest group, the public as consumer, the public as elected representative, the public as client or the public as citizen. Rather, their commitments were to their own personal interpretations of the public interest, profession and professionalism, self, sometimes even to nation, and humanity.

Harsh Reality #4: The combination of big data, hyper social media, and contracting is likely to increase the incidents of guerrilla government.

Big data plus social media plus contracting may equal the perfect guerrilla government storm. It is a fact of modern life that our governments are collecting more data at every level, and electronic access to those data is difficult to regulate. Tied in with this is the relative easy entry and access to social media, without filters and quality control, to disseminate those data. Finally, guerrilla government activity might be more easily implemented by contractors than career civil servants under certain circumstances.

Harsh Reality #5: Most public organizations are inadequately equipped to deal effectively with guerrilla government.

My research has shown that there are at least four primary conditions that tend to yield situations that encourage the festering of guerrilla government activities. These may occur alone or in combination with another:

-

• When internal opportunities for voicing one’s dissent are limited or decline

-

• When the perceived cost of voicing one’s opposition is greater than the perceived cost of guerrilla government activities

-

• When the issues involved are personalized or the subject of deeply held values

-

• When quitting one’s job or leaving one’s agency is seen as having a destructive (rather than a salutary) effect on the policies of concern.

Why did Snowden not work with his superiors or go the whistle blower route from the beginning? As a full time CIA employee, Snowden received a critical note in his personnel file for pointing out a glitch in software he was using, which dashed his chances for promotion. He learned that “Trying to work through the system…would only lead to punishment” (Reitman Reference Reitman2013). Snowden also studied the case of Thomas Drake who pursued the whistle blower route by providing information to Congress and to the Baltimore Sun about post-9/11 surveillance programs and mismanagement at the NSA. Drake was eventually indicted under the 1917 Espionage Act for mishandling classified material although the government’s case against him eventually was dropped. Drake lost his job, his savings, and his reputation. Today he works in the Apple store in Bethesda. This is what happens when you work through the system, Snowden learned.

Harsh Reality #6: The tensions inherent in guerrilla government will never be resolved.

The dilemma of guerrilla government is truly a public policy paradox: There is a need for accountability and control in our government organizations, but that same accountability and control can stifle innovation and positive change. Put another way, there is a need in government for career bureaucrats who are policy innovators and risk takers; at the same time, there is a need in government for career bureaucrats who are policy sustainers. Hence, the actions of the government guerrillas studied in my research are manifestations of the complex environment in which our public managers function, and every public manager needs to be aware of this.

Inherent in this paradox are many perennial clashing public administration tensions and issues. These tensions include the need for control versus the perceived need to disobey, the need for a centralizing hierarchy versus the need for local autonomy, and built-in tensions in the organizational structures and missions of organizations themselves. In the Snowden case, there are several unique tensions. These include national security versus civil liberties, privacy and transparency versus public safety, the need for greater NSA restraint versus the need for security and diplomatic advantage. Also at tension were the “overreaching and intrusive federal government” versus “the methods and intentions of Mr. Snowden…who did not just innocently stumble upon a treasure trove of documents detailing surveillance” (Byman and Wittes Reference Byman and Wittes2014). Finally, at tension is the desire for efficient government versus needed changes to reign in the NSA that will make the agency “less agile” (Byman and Wittes Reference Byman and Wittes2014).

To whom are these career public servants accountable? To whom are they to be responsive? Whose ethical standards are they to follow to gauge whether their own behaviors are responsible?

ADVICE FROM THE PROS

Assuming that guerrilla government is significant and should be a last resort (or near last resort) of dissenters, what might be done to reduce it? One possible answer lies in the training of new political appointees entering government for the first time at significant organization levels. A mandatory two-day (minimum) training course is necessary, including explaining their own subordination to the rule of law, constitutional requirements, the nature of legislative oversight, the desirability of working with career employees, and what it takes to lead in public agencies. My research concludes that guerrilla activity may be promoted by foolish moves by political appointees who think they have a mandate based on rhetoric uttered by a president while on the campaign trail and who think that career public administrators should be, and will be, the robotic implementers of the will of their superiors. Political appointees, as well as other high-level administrators, need to know that their capacity to destroy new ideas is as great as their capacity to create them.

My research concludes that guerrilla activity may be promoted by foolish moves by political appointees who think they have a mandate based on rhetoric uttered by a president while on the campaign trail and who think that career public administrators should be, and will be, the robotic implementers of the will of their superiors.

Of course, there will always be times when public managers will have to quash negative guerrilla government. Examples include, but are not limited to, when rights are in danger of being violated, laws are broken, or people may get hurt. Yet scholars who have studied empirically whether career public servants “work, shirk, or sabotage” find that bureaucrats in the United States largely are highly principled, hardworking, responsive, and functioning (Brehm and Gates Reference Brehm and Gates1997, 195–202; see also Feldman Reference Feldman1989; Golden Reference Golden2000; Goodsell Reference Goodsell2004; Wood and Waterman Reference Wood and Waterman1991; Reference Wood and Waterman1994). Hence, when there are incidents of guerrilla government, managers need to view them as potentially serious messages that need to be heard. Thus, part of the training of political appointees, as well as other public managers, should be the communication of the conclusion that our first line of defense can no longer be dismissing government guerrillas as mere zealots or trouble makers. This perspective acknowledges the central importance of dissent in organizations. (See O’Leary Reference O’Leary2014 for a discussion of dispute system design as a way to address guerrilla government.)

I surveyed members of the National Academy of Public Administration, an independent, nonpartisan organization chartered by Congress to assist federal, state, and local governments in improving their effectiveness, efficiency, and accountability as well as some of the veteran managers on the NASA Return-to-Flight Task Group that I served on after the Columbia space shuttle accident. I asked them about the value of dissent in organizations. Of the 216 current and former managers who responded, 213 indicated that dissent, when managed properly, is not only positive, but essential to a healthy organization. Dissent, they told me, can yield a diversity of viewpoints, promote positive change, encourage rigorous thinking, catalyze innovation, prevent catastrophes, promote a more positive workplace, and could increase employee satisfaction.

Consider this observation by Sean O’Keefe, former administrator of NASA: “Embracing dissent means inviting diversity of opinion from the people around you. My first rule is to never surround myself with people who are just like me. My second rule is to always insist upon someone voicing the dissenting opinion. Always.”

Here are the top six suggestions for managing guerrilla government from the seasoned managers I surveyed:

1. Create an organization culture that accepts, welcomes, and encourages candid dialogue and debate. Cultivate a questioning attitude by encouraging staff to challenge the assumptions and actions of the organization.

More than 200 of the 216 managers who responded to my survey emphasized that dissent, when managed well, can foster innovation and creativity. In particular, dissent can help generate multiple options that might not normally be considered by the organization. Managers should think of dissent as an opportunity to discuss alternative notions of how to achieve a goal. Cultivating the creative aspects behind dissent can lead to greater participation, higher job satisfaction, and, ultimately, better work product, the managers told me.

2. Listen.

More than 200 of the 216 managers who responded to my survey cited listening as one of the most important ways to manage dissent. This means listening not only to the actual words being said, but also what is behind the language of dissent. This also means communicating that one is looking for the best solution, then tuning into the underlying reasons for, or root problems of, the dissent.

As Karl Sleight, former director of the New York State Ethics Commission put it, “The hallmark of a strong leader is to be a good listener. Not just hear the dissent, but to probe it, evaluate it, challenge the underpinnings (without discarding it out of hand), and make a reasoned decision on whether the dissent has a viable position. The value of simply paying attention to dissent should not be underestimated. If the members of the organization know that the leader is comfortable with his/her leadership position, so to allow (even embrace) differing points of view, dissent can breed loyalty and a stronger organization. Obviously, the converse is also very true.”

3. Understand the formal and informal organization.

The majority of managers who responded to my survey emphasized that leaders must understand the organization both formally and informally. Terry Cooper explains the importance of this concept for ethical decision making:

Complying with the organization’s informal norms and procedures is ordinarily required of a responsible public administrator. These are the specific organizational means for structuring and maintaining work that is consistent with the organization’s legitimate mission. Because not everything can be written down formally, and recognizing that informally evolved norms give cohesion and identity to an organization, these unofficial patterns of practice play an essential role. However, at times these controls may subvert the mission or detract from its achievement, as in goal displacement. A truly responsible administrator will bear an obligation to propose changes when they become problematic for the wishes of the public, inconsistent with professional judgment, or in conflict with personal conscience. It is irresponsible to simply ignore or circumvent inappropriate norms and procedures on the one hand, or reluctantly comply with them on the other. (2012, 256–57)

The informal organization may be more difficult to identify, but it is often the environment within which dissent grows and develops. Dissent coming from the informal organization may be solely a sign of some disgruntled employees or it may be a legitimate, telltale sign of a significant issue within the organization. Dissent becomes productive when the members of the organization recognize and believe that the leaders are honestly concerned about them and are willing to work on making positive changes. At the same time, dissenters must also recognize that the structure of some organizations will prevent the type of change they hope to see (paramilitary organizations, for example).

4. Separate the people from the problem.

More than half of those who responded to my survey emphasized the need to approach issues on their merits and people as human beings. Put another way, don’t make it personal and don’t take it personally. Fisher, Ury, and Patton (1991) reinforced this idea in their best-selling book Getting to Yes, in which they advise managers to separate the relationship from the substance, deal directly with the people problem, and strive to solve the problem collaboratively.

A contracting officer at the Environmental Protection Agency put it this way: “Leaders must listen beyond the words and tone of the dissenters as sometimes their message is simply delivered the wrong way, and the message itself is valid. Leaders must try to understand where the dissenters are coming from; this shows respect for people and that can go a long way. When leaders handle dissent with respect, professional courtesy, and when necessary, the decision to ‘agree to disagree,’ people at least know they have been heard, which sends powerful messages that the employees can speak out and will be heard.”

5. Create multiple channels for dissent.

Many of the more seasoned managers who responded to my survey emphasized that it is important to realize that dissent happens in every organization. Therefore, if managers create a process that allows for dissent, employees will feel they can express their views and disagreements may be channeled into something productive. If dissent is stifled, this will only cause resentment. Set up a regular process to receive dissent. Be accessible. Have an open-door policy. Insist that employees come to you first. Allow employees to dissent in civil discourse in group meetings or in private through memos or conversations; some people who have great ideas that challenge the status quo do not like to display them publicly. A former director of the Office of Resource Management in the US Department of Energy put it this way: “Set up a regular process to receive dissent. Lay the ground rules for civil discourse. Actively listen to it. Act upon it and follow up to ensure that there was action.”

6. Create dissent boundaries and know when to stop.

“Dissent is important,” Sean O’Keefe told me, “but a leader has to know when to say ‘enough.’ If taken too far, dissent can be like pulling the thread of a sweater too long and hard… eventually the sweater unravels.” To illustrate this point, O’Keefe talked about his order to his staff and his promise to Congress after the Columbia space shuttle disaster. He ordered the implementation of every one of the 15 items labeled by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board before another space shuttle was launched. There were dozens of discussions between and among the staff about his forcing them to comply with all 15 points, with plenty of dissenters. Some staff wanted to implement some of the items, but not all. Many argued about the wisdom of the board’s recommendations themselves. But in the end, O’Keefe determined that in order to ensure a safer space shuttle program, he had to order that all 15 items be implemented—end of discussion.

CONCLUSION

Based on these cases, important questions emerge that potential government guerrillas should ask themselves before deciding whether to go the guerrilla government route:

-

• Is the feared damage immediate, permanent, and irreversible? Are safety and health issues involved? Or is there time for a longer view and a more open strategy?

-

• Am I adhering to the rule of law?

-

• Is there a legitimate conflict of laws?

-

• Is this an area that is purely and legitimately discretionary?

-

• Were all reasonable alternative avenues pursued?

-

• Would it be more ethical to promote transparency rather than working clandestinely?

-

• Would it be more ethical to work with sympathetic legislators before turning to media and outside groups?

-

• Am I correct?

At its best, the joint tradition between public administration and political science links theory and practice. Guerrilla government is a perfect example of an enduring challenge that benefits from this tradition, yet will remain a difficult area to sort out. It is a fact that all guerrilla activity is not created equal. How we decide which behavior is legitimate and which crosses unacceptable boundaries could be one of the most important questions of our time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Zach Bauer is thanked for his research assistance. George Frederickson, David Rosenbloom, Andrew Osorio, Misty Grayer, and Cody Johnson are thanked for helpful comments on a previous draft of this essay.

The National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity (www.FacultyDiversity.org) created a mentoring map that tells each of us that we need over 60 mentors in 16 categories throughout our lives. I have had all of that in my career, and more, and I am grateful. I am particularly appreciative of the excellent PhD education I received at the Maxwell School of Syracuse University under the direction of David Rosenbloom and Patricia Ingraham. Among my many role models who have demonstrated quality scholarship and leadership in the field are George Frederickson, Beryl Radin, Barbara Romzek, David Rosenbloom, Jim Perry, and Patricia Ingraham; all have also opened doors for me. I have worked with over 100 insightful coauthors who have pushed my thinking and made my work better, most recently Bob Durant, Dan Fiorino, David Rosenbloom, Lisa Bingham and Kirk Emerson. I am also indebted to the excellent colleagues I have had at Indiana University, Syracuse University, and most recently the University of Kansas. Last but not least, my husband, Larry Schroeder and our daughter Meghan have kept me sane and humble. Thank you.