How does Latinx literature contribute to the portrayal of Africa when Latinx letters enters world literature? How can we excavate the South-South internationalism of Latinx writers toward political contexts in Africa when remnants of coloniality still shape anti-blackness in Latinidad? What will a focused examination on the effects of coloniality in Africa per their representation in Nuyorican poetry say about global Latinx writing?

These questions draw from the possibility of productive third world alliances in Latinx literary culture with decolonization in Africa to contest European colonialism, and at times specifically French epistemological coloniality. I build on my previous work about the hidden African archive in some of the most widely read authors of Latin American descent in the last fifty years. Such works constitute what I term a “Latin-African” literature, and hence a South-South framework missing from many configurations of Atlantic world, world literature, and postcolonial studies. For indeed, Latin America, and by extension Latinx literary culture, has remained absent in postcolonial studies in general, and African literary criticism in particular. This disconnect draws, in part, from what Monica Popescu argues is a “disassociative approach” between the postcolonial and Cold War studies that in fact ignore “the shaping element of the decolonizing struggles” even in postcolonial canonical writers, from Edward Said to Frantz Fanon.Footnote 1 This in turn has relegated Latin American concerns away from postcolonial considerations, ignoring the role of the Cuban Revolution, for example, in some of the most recognized postcolonial African writers.Footnote 2 Inverting this notion from Popescu, I would like to consider what happens when this Cold War context of African decolonization affects canonical writers of Latin American descent. This article will argue that a resulting Latin-African frame enriches South-South approaches to the postcolonial or transatlantic fields thus far neglected. Bridging Latinx writing and African decolonial histories, this article addresses Latinx representations of Africa when these both enter world literature and center the African liberation movement of the Cold War era but become entangled with Western domination.

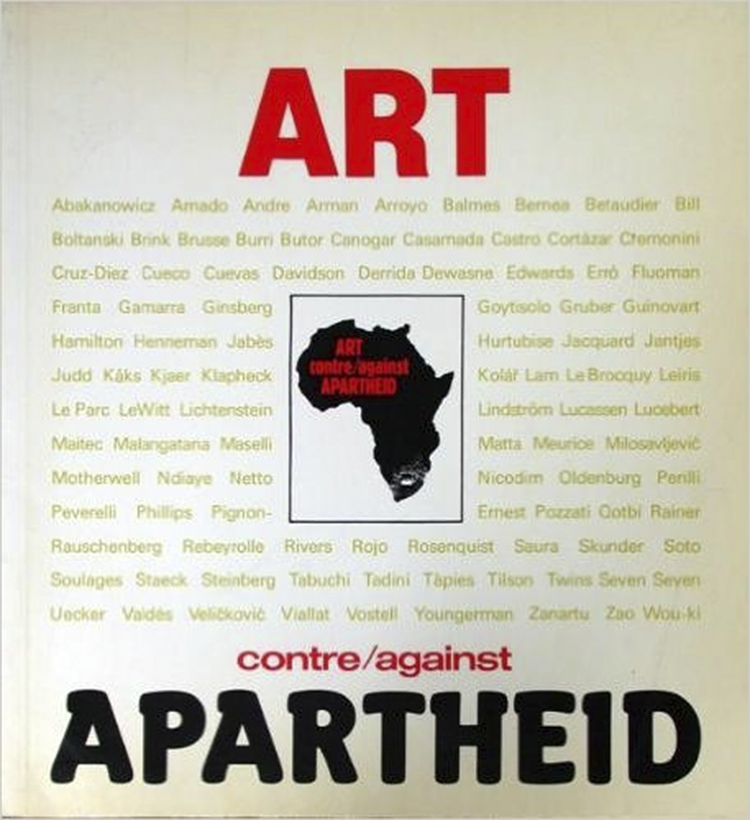

In this article, I focus on portrayals of very different contexts of African decolonization in the works of two renowned Latinx writers who are also Nuyorican poets: French colonialism in Miguel Algarín’s Morocco in the canonical anthology Nuyorican Poetry on one hand, and Sandra María Esteves’s rendition of the British and Dutch colony of apartheid South Africa for the French Art contre/against apartheid project on the other (fig. 1). In the case of Algarín, I read the ways the Orientalist evocations of the illicit sex trade of boys in Tangier attempt to enact a relational solidarity and how the Nuyorican observer comes into crisis when that third world alliance cannot be achieved. Regarding Esteves, I read her anti-apartheid poems and other internationalist works alongside Fanon and his decolonial reactions to French colonization of Algeria. In both cases, I am concerned with how Nuyorican poetic engagements with African self-determination, whether individual or collective, exhibit residues of what Fanon characterizes as a French hegemony in particular and a Western coloniality in general that could undergird—and undercut—the internationalist solidarity these poems exhibit discursively.

Figure 1. Cover of the original project Art contre/against apartheid. Photo by the author, 2021.

In overarching terms, I will also explain how a Western European coloniality affects the framing of the global south in Latinx studies. Even if other European colonialities exercise force over the poetry at hand, theoretically, this article focuses on French hegemony. An obvious bridge into French coloniality is the notion of latinité, a concept often used to denote the alleged Latinx ontology. “Latinidad” traces its origin to the early modern period of French westward expansion, as Walter Mignolo has long argued. This coloniality then extends to the decolonial period in Africa; efforts that Nuyorican poets once supported. In his influential study on Nuyorican writers, Urayoán Noel briefly mentions the Latinx internationalist vein of these writers as “decolonial.” Drawing from Mignolo’s “colonial difference,” he uses this term as a theoretical device applied to the Nuyorican context of social change in the United States, as opposed to a historical Cold War context in Africa.Footnote 3 I would like to expand from Noel’s “decolonial” frame to consider this notion as a poetic reaction to temporality. After all, “Decolonization,” Fanon writes, “is a historical process,” one that “can only … find its significance and become self coherent insofar as we discern the history-making movement which gives it form and substance.”Footnote 4 Thus, I will argue that these Nuyorican representations of a desired African liberation enrich but also complicate a Latinx allyship with the global south.

At the end of the twentieth century, the independence movements attempting to decolonize African regions, from the Congo to Algeria, evolved into civil wars that did not end until well into the current millennium. Remnants of this outlook perhaps pervade Algarín’s poem “Tangiers.” Although most of my analysis focuses on Esteves’s anti-apartheid poetry, I place her liberationist work alongside Algarín’s only poem privileging a North African region. In this widely anthologized poem, subtle evocations of Marxist liberation are extended to an abject people in Morocco. Paradoxically, however, this South-South solidarity pivots to frame Tangier through a poverty discourse. The Nuyorican poet rises above his Moroccan interlocutors due to his elevated socioeconomic status, casting into relief a distance that is traced back to a French Orientalism in North Africa.

By contrast, Esteves’s poem offers a different approach. The only woman to have broken into the male-dominated Nuyorican poets’ movement, Esteves is also the only Latinx writer to have contributed to the Arts Against Apartheid: Works for Freedom (1986) project, even though this participation has not been addressed in literary criticism. “Fighting Demons” published in Bluestown Mockingbird Mambo (1990) was one of the poems featured four years earlier in this international project. Originating from its French version, Art contre/against apartheid was launched in 1983 in Paris and then traveled the world. I focus on the project’s poem “Fighting Demons” because it serves as an important access point to Esteves’s draft poems in her archive (at Centro), within which I trace a poetic evolution with subtle influences of Fanon’s reaction to French colonization. Because this project framed Esteves’s antiracist internationalist poetry, it beckons us to revisit key moments when she drew on African political ideology and was thus in dialogue with other internationalist artists of her time, producing a South-South coalition we might term “Latin-African.” Finally, I will also consider Esteves’s Latin-Africa in conversation with the controversy that Jacques Derrida’s foreword for Art contre/against apartheid created. Derrida republished his essay “Le dernier mot du racism” from a 1985 special issue in Critical Inquiry edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. for Art contre/against apartheid. When this occurred, South African scholars Anne McClintock and Rob Nixon accused Derrida of neglecting accurate African referents and limiting his scope to the national. Their argument suggests that Eurocentric programming undergirds a project that, on the one hand, supports African self-determination but, on the other, paradoxically ignores African history. The issue that this controversy raises is crucial for how an African referent is portrayed in Latinx letters. The question that interests me most in the case of Esteves is, can this world stage enable an evident Latin-Africa to decolonize Art contre/against apartheid? More generally, how should we read African referents in Latinx literature in the world?

Global Latinx Literature and the French Atlantic

In the last few decades, Latinx literature and literary criticism have evinced a global turn. Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Central America have become the locus of enunciation in much of contemporary Latinx literary production. Achy Obejas’s assessment of the Cuban-Angolan crucible at the end of the Cold War, Mario Acevedo’s critique of the Bush-era Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Cristina García’s interpolation of the civil wars in Iran and El SalvadorFootnote 5 tie the racialized experience of a Latinx population to US foreign policy in the global south. Latinx literary criticism, such as that of José David Saldívar, Ariana Vigil, or Ben V. Olguín delve concretely into how US invasions from Cuba or Nicaragua to Afghanistan or Vietnam shape the geopolitical literary space of Latinx writers. But when Latinx letters enter world literature, not only is this discursivity excised from the context of South-South dialogues, but a neoliberalized trend in distribution also essentializes much of Latinx literary output.Footnote 6 As a result, Latinx letters have either not featured in many world literature anthologies, or when they do, their critical internationalism is not meaningfully addressed. Instead, with the exception of a handful of scholars, Latinx writing in the global south is mostly eschewed, haunted by the eurocentric framing of “latinité.”

To begin unpacking the reasoning behind this excision, I propose we look to the origins of Latinidad as a framework. As Mignolo has explained, Latinidad signifies Latin Americans of European extraction, excluding those of Indian or African origin.Footnote 7 If a colonial Eurocentricity in Latinx studies shows traces of Spanish monarchy or a rigid, monolingual American framework, it is also undergirded by an understudied French variable brought to life in Raúl Coronado’s sweeping study, where he traces the racial and cultural aspiration to whiteness of nineteenth-century Texan Latinos who forged their imagined community based, in part, on the afterlife of French intellectual thought. Far from imagining themselves as belonging to Mexican culture, Coronado asserts that Mexico “remains affectively cool, an object to be possessed and not identified with” once these Latino forefathers become “Americans.”Footnote 8 Instead, these men evoked a Habsburg nostalgia for late scholasticism, with traces of French rationalism and skeptical scientific inquiry.Footnote 9 More recently, in the context of an emerging Cold War, and in another sweeping study, Olguín recenters the Fanonian instrumentality of materialist violence in the memoir of a Mexican American volunteer with the “quintessentially colonialist” French Foreign Legion.Footnote 10 He categorizes such complex membership as part of a Latinx experience of “violentology” (by which he means violence as a lived experience but also, in a Fanonian way, “violence as agency”).Footnote 11 This move aligns the Mexican American volunteer with a white French hegemony that is directly antithetical to assumptions of a Latinx resistance to Western imperialism.Footnote 12 Although Olguín argues that this dissolution of the familiar Latinx narrative into the violent and foreign might be conceived as “disturbing” and “bizarre,”Footnote 13 such archival discoveries from Coronado to Olguín reveal the arguably unintentional conclusion that the French Atlantic is a key participant in the porous and complicated textual world of Latinx expression.

In this regard, a framework informed by Fanon’s experience of French colonial violence in Algeria is pertinent to the context of US Puerto Rican writing in the Cold War era. After all, the Francophone Martinican thinker has been variously employed to understand a particular diasporic subjectivity. For example, both Marta E. Sánchez and Yolanda Martínez-Sanmiguel have read renowned US Puerto Rican writer Piri Thomas’s estrangement from self though a Fanonian lens.Footnote 14 They argue that there is something about coloniality—in this case modeled through the French coloniality that Fanon experiences—that renders the US Puerto Rican an exile in his own body by virtue of both the color of his skin and his language. Moreover, Martínez-Sanmiguel justifies this dialogue given the similar contexts of unrealized decolonization that both Puerto Rico and Fanon’s native Martinique experience;Footnote 15 and coincidentally both remain under the political sovereignty of their respective imperial powers. In the case of Algarín and Esteves, Fanon and his reading of African liberation through the lens of French colonialism in Algeria becomes central for considering their internationalist angle. For Algarín, I focus less on Fanonian ideology and more on the French colonial context in the region of Fanon’s dialectical interest: the region of North Africa and the resulting effects in Algarín’s negotiation with French Orientalism in Morocco. For Esteves, I am more interested in the rhetoric Fanon uses in Algeria, which he later connects to South Africa and other regions, similar to Esteves. Thus, if the aforementioned works open the door to reading a radical globality as an alternative model for assessing Latinx internationalism, I suggest focusing on an underappreciated French Atlantic. This unconventional comparativism reveals how internationalism—when partners across the global south supported their allies’ self-determination—preoccupied several Latinx writers during and after the Cold War era. But this article also considers what to make of their South-South solidarities in light of decolonial failure.

Algarín’s Morocco and the Question of Orientalism

Miguel Algarín was a founder of the Nuyorican poetry movement and the Nuyorican Poets Café on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. In fact, “Tangiers” was first published in Algarín’s 1975 anthology Nuyorican Poetry: An Anthology of Puerto Rican Words and Feelings, coedited with Miguel Piñero. It is precisely the specification of US ethnic identity in this anthology that creates intrigue in the inclusion of a poem like “Tangiers.” After all, unlike most of the poems in the volume, “Tangiers” is not about the Puerto Rican diasporic experience in New York or the American hemisphere. It is also the only poem that includes lines in French. Moreover, with very few exceptions (notably the poem “Viet-Nam” by Archie Martínez, for example) “Tangiers” features the actions taking place outside of political borders of the United States. Ideologically political as well, the poem attempts an internationalist perspective, as “Tangiers” seeks to mobilize a global leftist brotherhood with its antipoverty and antiracist rhetoric. Paradoxically, however, the poem also triggers memories of Orientalist fantasies in the poem’s portrayal of the sex trade of underage boys. But far from constituting homo-erotic voyeurism, the poet’s psychosomatic expression of illicit prostitution is underwritten by Euro-American Orientalist tropes in general, and French colonialism in particular. I am drawn, specifically, to Algarín’s inclusion of French in his usual Spanish and English code-switching. Especially as French is used in places in which he seems initially to perpetuate stereotypical colonialist tropes. At the end of my analysis, I explain how Algarín’s portrayal and ensuing identification with this abjection suggest an identity crisis—one that reflects a South-South engagement, however problematic this identification may seem at first.

Algarín’s poem “Tangiers” is inspired by the interzone of Morocco—a shared French and Spanish protectorate ratified in Paris on December 18, 1923—that became a mythical, bohemian space, attracting writers from Gertrude Stein to Truman Capote and the Beat poets. This international status ended in 1956, but Tangier continued to draw “suspect activities ranging from international monetary speculation and a black market in drugs to underage prostitution.”Footnote 16 Set during Algarín’s own visit to Tangier with his Nuyorican companions, it is precisely the scene of child sexual exploitation that interrupts the otherwise cheerful vagabond experience pervading the beginning lines of the poem. This is because when Algarín playfully announces he is going “down to the Kasba,” he immediately confronts “the hollering poverty/ of Tangiers where boys sell/ themselves for little more than/ a dollar’s caress.”Footnote 17 Later, the poetic voice even observes the illicit fantasy of “eyes anxiously raping a twelve/ year old crotch” as the willing victim of “the boy smiles.”Footnote 18 Indeed, Algarín and his fellow Nuyorican companions witness what Joseph A. Boone terms “a colonized Third World in which the availability of casual sex is based on an economics of boys.”Footnote 19 For Algarín’s poem reflects this economics of homoerotic flesh displayed in “beautiful boys approach/ beautiful boys go away/ beautiful boys approach/ beautiful boys go away/ all are for sale.”Footnote 20 This ebb and flow of availability dramatizes the unbridled excess and tragedy of underage prostitution in the global south seen through the eyes of a self-described “colonized Third World” Nuyorican poet. Although Algarín does not participate in the trade nor seek fulfilment from it, he remains coolly objective to it. As he reports that a price is placed on their bodies, “ten dirhams for this one/ twenty dirhams for the other,”Footnote 21 Algarín offers no other value judgment other than a comparison to sex exploitation in New York in “Tangiers is Forty-Second Street/ morality with an Orchard Street.” Soon after, a maimed boy, “un muchachito tuerto,” pleads to service him too, a “guilt trip” that only acquiesces to “a dirham” he fishes out of his pocket.Footnote 22

I will venture to say that this poem is one of Algarín’s most enriching, if not paradoxical contributions to the Nuyorican poetry movement: it not only provides a glimpse into the complex Nuyorican cosmopolitan experience—its internationalism—it also confronts the complexities of the US Puerto Rican as a member or ally of the global south and simultaneously foreign to it. I will begin by discussing the first paradigm in that, as an internationalist poem, “Tangiers” is not without its cosmopolitan complications. For example, the poem is notably undergirded by Euro-American Orientalisms. After all, from Edith Wharton’s travel narrative In Morocco, which endorsed French colonialism to the objectionable gay heaven celebrated in the 1950s work of William S. Burroughs (published in 1989 as Interzone), or the Spanish ethnographic portraits of José Tapiró y Baró and Mariano Bertuchi Nieto, an Orientalism runs the gamut from primitivizing Morocco to suggesting European intervention for its so-called lawlessness. These American and Spanish Orientalisms must exert an influence on Algarín’s poem and are the most legible axes for the Latinx experience. However, the much less discussed French axis in Latinx writing also carries some weight in the formation of North African imaginaries, especially as Algarín resorts to French in places in which he celebrates both the physical traits of these boys and also the allure of Tangier.

One of the lines that leaves a lasting impression in the poem is when Algarín code-switches among Spanish, English, and French. For example, his love offering to Tangier in Spanish “Tangiers yo ya te quiero”—recalling “Aquí te amo” from Pablo Neruda’s eighteenth verse of love—turns to French in “estoy enamorado d’être ici/ dans le nord d’Afrique/ dans la ville la plus belle/ que j’avais jamais vue.” Footnote 23 Algarín’s embrace of Tangier as the most beautiful city he has ever seen suggests an equally accepting embrace of its marginalized subjects despite their abjection as pawns of an illicit sex trade. In fact, Noel offers that this linguistic shift is a mechanism to “find the language of the interzone that links Tangier to the Lower East Side,”Footnote 24 a form of solidarity I will come back to at the end of this analysis. This switch from English and Spanish to French, however, also marks the particularly French visualization of this boy as exotic: “Tangiers your children are les/plus beaux du monde.” Footnote 25 The positivity here echoes that of Burroughs when he terms Tangier a “sanctuary of noninterference.” Footnote 26 Boone notes that this queer “haven” nevertheless “allowed a level of sexual exploitation potentially as objectionable as the experience of marginalization and harassment that sent these Western voyagers abroad in the first place.” Footnote 27 The same Tangier that Burroughs thus finds utopic is less so for Algarín, and yet, these exploited beautiful boys and the French parlance Algarín’s poem offers, like male prostitution, are specifically informed by the nineteenth- to twentieth-century French portrayals of the “Orient.”

France’s colonial conquest of North Africa began with the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt in 1798 and ended with the Algerian War in 1962. In between, as Said famously noted, the complex legacy of French Orientalism continues to haunt contemporary idealization and imaginaries of what was termed “the Maghreb.” Morocco in particular came under France’s domain when a French delegation marched into the region in 1832 to seek the sultan’s neutrality for what would become the seizing of Algeria in 1834. Eugène Delacroix accompanied this delegation and an Orientalism ensued.Footnote 28 Morocco’s so-called “strangeness” in particular was solidified in the travel writing of Pierre Loti in 1890 with Au Maroc, as others joined the ranks.Footnote 29 From the nineteenth century forward, as Said notes, French literary representation “associates the Orient with the escapism of sexual fantasy.”Footnote 30 Gustave Flaubert in particular uses “Oriental clichés” from harems to slaves or dancing girls and boys, to solidify that an “association is clearly made between the Orient and the freedom of licentious sex.”Footnote 31 The comment suggests or even justifies an invitation for a French civilizing mission,Footnote 32 conveniently overlooking that it was European coloniality in general—and French imperialism in particular—that made Morocco licentious in the first place. Notably, under the Spanish protectorate, prostitution also became a recognizable trope in Morocco. Since the early 1920s, brothels in Tangier specifically were not only staffed by Spanish women, they catered to Spanish men, who also became “narrators of sexual tourism.”Footnote 33 And yet, as Camila Pastor de Maria Campos notes, while the Spanish exploited the system of prostitution, the French colonial system set the groundwork for its implementation:

In French Morocco, professional prostitution was the product of colonial administration in two distinct ways. First, through the strangling into disarray of an earlier landscape of commercial sex anchored in the institutions of slavery and entertainment. And second, through deliberate implementation of the metropolitan system of regulated prostitution throughout colonial territories, professionalizing and segregating women into prostitutes.Footnote 34

Moreover, and more specific to Algarín, male prostitution was confined to French Morocco. As Pastor de Maria Campos notes, even advertisements for gay sex tourism in Northern Africa was targeted toward French travelers and was completely bypassed in Spain.Footnote 35 In fact, “Morocco has also served as a mecca for the gay and bisexual literati vacationing in North Africa—many clustered around Tangier’s famous resident Paul Bowles.”Footnote 36 From French writer André Gide’s l’Immoraliste (1902) to Moroccan Mohammed Mrabet’s Love with a Few Hairs (1967), as Boone has shown, literature undergirded by French coloniality perpetuated the stereotype of the Moroccan boy as a sexual object. At the same time, the sexually exploitative space that haunts Algarín’s Tangier dealt with a linguistic colonization of the French language that is of notice. Anisse Talahite explains that “[t]he more recent history of North Africa saw the birth of a new literature that originated from the experience of French colonialism in the former colonies of the Maghreb.”Footnote 37 Because of the overwhelming gravity that French colonial rule inflicted, even “Francophone Maghrebian writers deal with the contradictions and dualities of modern Arab societies by adapting the French language to their own world view,”Footnote 38 a method that Algarín will also share. With recourse to French linguistic expression, Algarín’s sexually exploited boys in his poem further the argument that certain forms of French coloniality, like Euro-American Orientalism, have yet to be derooted from Latinx writing. After all, many of the forms of adulation and simultaneous exotization in his poem—the boys are “le plus beaux du monde” and “the boys parade themselves— / the older queen exhibits a skin”Footnote 39—recycle the very same Orientalisms described previously, undercutting the poet’s desired South-South solidarity.

Perhaps the reason Algarín employs this Orientalism is because he desires to see himself in the Moroccan subject and enters into crisis when he cannot. Thus, addressing the paradigm of South-South identification and its complications, Algarín’s desired relation to the Moroccan boys is akin to portrayals of Moroccans in a Brazilian telenovela (“soap”) that Waïl S. Hassan has theorized. For him, these Orientalisms in the global south point of Brazil read as an “anxiety about Brazil’s own cultural identity as a postcolonial nation that differentiates itself from the erstwhile ‘mother country’ of Portugal.”Footnote 40 For the US Puerto Rican in Algarín, on the other hand, his center of gravity rotates through Euro-American or French Orientalisms, but his global south solidarity is further precluded by an identification with the United States. To put it differently, Algarín’s Orientalisms are certainly mediated by Euro-American discourse, but he must also contend with his simultaneous marginalization and privilege that comes from being a US citizen. In the process, the poem seems to both resist Western binaries while simultaneously falling prey to them. For example, the moment the poem shifts to French, the poetic voice, as Noel offered previously, attempts to relate to the Moroccan. Yet, he is prevented from doing so by his socioeconomic class difference. The lines “I love the happy tyranny of being/ attacked on all sides for my/ American connection ‘les dollars’”Footnote 41 are surprising and perhaps a little unsettling unless we read it as an ironic expression of socioeconomic contrast. Momentarily, when the “boy’s imploring hustle” is described as the catalyst for “sending our/ hands into our pockets searching/ for a dirham to leave our consciousness/ clean, to buy us freedom” Footnote 42 is both anxious and empathetic, yet still displays an inevitable feeling of privilege. The line that immediately follows, “we are head to mouth Nuyoricans/ suddenly made rich by greater poverty,”Footnote 43 similarly expresses the anxieties and simultaneous slippages into coloniality, as the poet’s binary system places Tangier on the lower echelon of that hierarchy. Although the poetic voice does not bask in his higher socioeconomic status, the distance between the observing American and the observed Moroccan haunts the poet.

Cementing that distance further is the fact that the onlooker poet observes the “many maimed men” and “hungry young boys” from the vantage point of a café, sipping on “café crème” and offering “dirhams” to the “endless/begging” that is now constitutive of the imagined Morocco of countless other Euro-American fantasies.Footnote 44 Although Noel has read Algarín’s vantage point as “privileged,” calling it an “irony” that Algarín is “occupying the role of the American expatriate in Tangier given his own Nuyorican identity,”Footnote 45 what is also ironic is that the hypervisibility of poverty here is similar to the stereotypical representations of New York poverty in Oscar Lewis’s La Vida: A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty—San Juan and New York (1966), which Noel critiques.Footnote 46 As the discourse of poverty and a US American self-differentiation collide in the poem, this marked socioeconomic distance is not a critique of Algarín but a notable expression of anxiety: an unreachable empathy in the South-South axis. For even if Moroccan difference “reconnects [Algarín] to his own colonial history,” Footnote 47 Tangier cannot be separated from the very poverty discourse that once problematically ensconced Puerto Ricans in Lewis’s infamous ethnography.

I want to be clear that Algarín does not taunt his Moroccan interlocutors with his superior socioeconomic position vis-à-vis the underserved in Tangier. Moreover, I do not wish to align with politics of positive imagery or subscribe to the notion that a negative portrayal of perceived otherness here might spread expectations of underdevelopment, as Aarthi Vadde warns against in her urgent study on internationalism.Footnote 48 What I have been arguing, rather, is that there is a French mediation that adds to Algarín’s perception of Tangier that is later complicated by the social mobility conferred to him by his US American citizenship. Euro-American imperialisms become entangled and later concealed in expressions of the poem that complicate Algarín’s discursive allyship with the global south. This happens despite the fact that African decolonization movements and their leaders, Leopold Sédar Senghor, Agostinho Neto, and Patrice Lumumba,—poets like Algarín—spurred the Nuyorican poetry movement.Footnote 49 In other words, Algarín was no stranger to these forms of decolonial African nationalisms, but his “Tangiers” is in these lines precluded from representing discursively what Algarín desired ideologically. But to dismiss these slippages and ignore the globalities that simultaneously complicate and enrich Latinx writing is a mistake. After all, as Olguín argues that “at least since the 1930s” Latinx people and their writing have been producing a “global Latinidades” model overlooked in ethnic studies and only rendered “implicit” in its theorization.Footnote 50 Although I am not arguing for a “global Latinidades” model here, what I do want to point out is how the general and particular idealizations of the international—via Morocco in this case—for Algarín are unique; a uniqueness that stems from its unrepresentability and erasure from South-South theory, global south studies, or Latinx literary critique. This is because what Algarín proposes beyond the veneer of exoticism and distance is rather a Latin-African model of relation or a South-South relation sorely undertheorized to date.

In Algarín’s representations of Morocco, there is something distinct from those of the global north, aligning with Latin American representations but also differing from them. This can be perceived in the fact that Algarín’s South-South perception transforms into a Latin-African one. For indeed, as Anne Garland Mahler has contended, when Algarín reads the abjection of the US Puerto Rican into the Moroccan, he asserts a “mutual exploitation and objectification.”Footnote 51 In “Tangiers” the singularity of the sex trade of boys and their equally distinguishable abjection brings the poet into the realization that this Orientalism is quite familiar. If “Nuyoricans/ suddenly made rich by greater poverty” feel distanced, the poet suddenly remembers his own abjection. “… but wait!/ Tangiers, our inner-city jungles” the poet remarks “match yours and they are equally/ poor, dirty, misunderstood, desperate/ and we are struggling, hustling men/ just like your boys.”Footnote 52 The Moroccan cityscape opens up to New York City, as New York too is seen through the lens of poverty. If Hassan has read Brazilian representations of Moroccans as denoting neither “negativity or inferiority” and are “a function of leftist critique that seeks to disrupt common assumptions,”Footnote 53 here too Algarín disrupts a common assumption on the left. Differently, however, Algarín embraces abjection just like he neither judged nor condemned the boys, who, through no fault of their own, were confined to a structural sex trade. He embraces such abjection because he sees these marginalized subjects, like himself, as the revolutionary underdogs: “just like your boys/ but we exist inside the belly of the/ monster, we are the pistons that/move the roughage through Uncle/ Sam’s intestines.”Footnote 54 Existing as the Fanonian “wretched of the earth,” Algarín does make a distinction that he lives “in the belly of the monster” readapting a well-known José Martí phrasing. Arguably he conveys that although the level of exploitation is not the same, the political identifier of a third world politics unites them on opposite ends of an Atlantic colonial continuum. In other words, although Algarín is pulled between Latin American and North American forces of identity, he now also identifies with the Moroccan subject, as the poem turns again to French: “a revolutionary is un merchand ambulant,/ a revolutionary is a petit taxi.”Footnote 55 This discourse notably extends a leftist solidarity, made apparent in the Marxist tones of the term “revolutionary” and working-class trades. All the same, there is a lamentation for this abjection in “Tangiers your children are les/ plus beaux du monde and yet/ they scurry down your gutter-alleys,” Footnote 56 where Algarín takes notice of the tragic irony of unending colonialism. The same irony is felt in their linguistic cosmopolitanism, in which despite their notable polyglot ability (“Tangiers your bleeding children speak/ three, four, five languages before/ they’re five years old”), “they hustle the cracks of the streets”. The poem’s final overture to global south solidarity reaches its climax when Algarín concludes that the only difference between Nuyoricans and Arab Moroccans is “THE DIRECTION IN WHICH THE WIND BLOWS.”Footnote 57

Consistently, the poem features ebbs and flows of Orientalism and insistence on poverty, while also affirming a working-class solidarity and relation. While in conflict, these contradictions speak to the crisis of South-South identification when both global south subjectivities are mediated through Western discourses. As a result, the South-South expressions in Algarín remain complex, less identifiable, categorizable, and thus passed up. Such a trend is echoed in other recent scholarship in both American and African studies, in which complex representations of othering in the global south express an undefinability, which in turn renders them subversive and worthy of discussion.Footnote 58 An analysis of Algarín joins these notable works, suggesting that despite the poem’s subtle if unintended traces of Western economic superiority and Orientalist presences, the poem also accomplishes an undertheorized internationalist gesture. But as will become clearer in the case of Esteves, these contradictions are nevertheless Latin-African, attempting to decenter even the ways we think across South-South axes.

Sandra María Esteves’s Fanonian Poetry against Apartheid

If Algarín’s internationalist reach featured Tangier, Morocco, in North Africa, Esteves’s poem travels to the south end of the continent to focus on a very different context of European colonization: the former British and Dutch colony of apartheid South Africa. In what follows, I read the internationalist poems of Sandra María Esteves, the “godmother of the Nuyorican poets,” alongside her participation in the Art contre/against apartheid collective; an art project that began in France with a November 1983 exhibit that later traveled the world. In doing so, I show how Esteves’s work shores up not only art methods she shares with other internationalist artists, including one who participated in the original Art contre/against apartheid project, but also a Fanonian ideology. Different from Algarín, Esteves’s work does not focus on French colonization, but does engage in Fanon’s third world philosophy. As Fanon uses French colonialism in Algeria as an example that connects to the rest of colonized Africa in his “international colonialism,” Esteves champions this internationalist method. In her archive, a draft of a poem that would become “From Fanon” was initially entitled “We,” and in reading these two poems together, their evolution suggests a Fanonian third world philosophy that contests French colonial violence. This poem literarily uses then the ideas from “From Fanon” to extend into other examples of colonialism such as that of South Africa. This poetic evolution also explains how a Fanonian ideology shaped her internationalist work, from her poems in Art Against Apartheid to others in her archive that later became part of Yerba Buena (1980). At the end of this article, I conclude by considering what to make of the fact that her internationalist work is contained in a project like Art contre/against apartheid that is itself mired in controversy. This controversy stems from the accusation that Derrida’s foreword for the project mischaracterizes the roots of South African apartheid.

With support from the United Nations, Art contre/against apartheid was curated by Spanish artist Antonio Saura and French artist Ernest Pignon-Ernest of the Association of Artists of the World against Apartheid. It sponsored eighty-five of the world’s renowned artists and writers, including Latin American representatives Julio Cortázar, Jorge Amado, and Wifredo Lam. Esteves contributed the poems “Fighting Demons” and “It is Raining Today” to a 1986 version, renamed Art Against Apartheid, which included a preface by Alice Walker.Footnote 59 Relating African self-determination to the US fight for civil rights, this collection brought the anti-apartheid struggle into the center of US politics. For her part, Esteves’s “Fighting Demons,” the featured poem for the project, enters world literature through a representation of South Africa in Latinx poetry that connects the exploitation in East Harlem and the South Bronx with spaces like Soweto and Sharpeville, South Africa, along with other international locales. “Fighting Demons” is not usually identified with this project, but rather as poem included in her arguably most successful collection, Bluestown Mockingbird Mambo, which draws on blues, jazz, and mambo.Footnote 60 In this regard, “Fighting Demons” as part of this whole is often read as underscoring the local identity of Nuyoricans. And yet, the poem reflects on her own experience of oppression at home to link this struggle with apartheid South Africa. This framework in her work is unexamined, even though early critics like Nicolás Kanellos to, recently, Karen Jaime mention in passing that Esteves’s purview encompasses “worldwide” oppression beyond “ethnic and cultural belonging.”Footnote 61 This ideology was mediated by her lived experience in East Harlem, a site of enunciation for Black South African rights since 1946, which proved decisive in honing Esteves’s leftist yet localized ideology as the bedrock for the Young Lords. Not only did Harlem become “the center of the [Young Lords] group’s most iconic interventions,” as Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé has explained, but the movement’s leftist ideology also promoted progressive reforms that led to the creation of El Museo del Barrio in 1969,Footnote 62 a stage for a major Afrolatinx incursion into Nuyorican culture.Footnote 63 Thus, as Vanessa Pérez Rosario has stated, Esteves’s poetry comes to terms with her racialized blackness and Puerto Rican “displacement” through an alignment with this global south ideology, or “models for cosmopolitan life, nonaligned transnationalities.”Footnote 64 Notably then, her 1980s poems in Yerba Buena would employ a third world rhetoric. A child warrior in her poem “Weaver,” for example, uses the term “the colors of our people” which, as Mahler has explained, was a common moniker of “anti-imperialist politics.”Footnote 65 Her poem “Staring into the Eye of Truth,” likewise venerates “Marx/ Lenin, Mao and Gibran,”Footnote 66 while her book of poetry in Yerba Buena features at least two poems venerating Cuba. This global viewpoint seems evident in her work but remains undertheorized.

Undertheorized as well is a poem that springs out of this context a few years later. Dedicated to South Africa, “Fighting Demons” (1986) unfolds an international comparison by asking rhetorically what difference there is “between here and there,” between New York and South Africa. At first reminiscent of Algarín’s relatability between Arabs and Nuyoricans, Esteves’s broad generalization takes on greater specificity as the poem conjures moments of veritable anti-Black and anti-Brown tragedies across an Atlantic continuum: “South Bronx, Soweto, Harlem, East Harlem, Namibia,/ Lower East Side, Sharpeville, Williamsburg, Watts, Johannesburg.”Footnote 67 Sharpeville, Williamsburg, and Watts, appearing in the same line, recall very specific locales of anti-Black violence.Footnote 68 But while “Williamsburg” refers to Brooklyn, New York, and Watts, Los Angeles, these two US American sites are then connected to Sharpeville, where the massacre of March 21, 1960 occurred at a police station in this South African township. This event was memorialized by Nelson Mandela in 1996, and the date of March 21 was selected by UNESCO as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The evocation of Sharpeville, moreover, links her poem to an ideology shared with Fanon. Preceding Esteves’s Sharpeville, Fanon states that “Sharpeville has become a symbol” that will unite the “Third World [that] fits into the framework of the cold war.”Footnote 69 If Sharpeville was yet another example—a symbol—of the ruthlessness of coloniality and hence the catalyst for third world revolution, Algeria was its origin. For The Wretched of the Earth reacts to Fanon’s lived experience of the French-originated genocide of 1 million Algerians during the Algerian War (1954–1962). As a result, the “Algerian revolution” that ensues, Fanon states, “has never been so acutely and so substantially present as in this region of Africa: whether among the Senegalese, the Cameroonians, or the South Africans.”Footnote 70 To link Algeria then to Sharpeville is to substantiate a third world discourse against French colonialism, one that becomes triangulated, via Fanon, in Esteves’s work. I join Esteves and Fanon less to assert that Fanon directly informs Esteves’s mention of the South African massacre and more to use this mention as an access point into other moments in Esteves’s work that underscore a clear Fanonian third world ideology, and by extension, a French colonization operative in her poetry. To develop this idea, I will first discuss how a Fanonian discourse emerges in her Art Against Apartheid poem, to later return to the ways in which this discourse develops in her poetry as is made clear from drafts in her archives.

Fanon and the revolution he signifies is perhaps unconsciously evoked in Esteves’s “The Artist is the Life Force South Bronx” in which she connects barrio introspection to a recognizable Francophone North African frontier: “I had to look myself deep into my eye/ Deeper into the deepest part corner of the retina/ Focused in South Bronx Algiers.”Footnote 71 Noel is one of the few scholars to locate a decolonial frame in this instance, offering that the poem is a “painful self-scrutiny meets decolonial identification;”Footnote 72 a reaction to coloniality. Elaborating from this analysis, I would like to suggest that this “decolonial” expression in Esteves is also specific to the historical context of African liberation and its global allies. Before Esteves participated in Art Against Apartheid, a few drafts of poems found in her archive at Centro (the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College)—some of which are included in her Yerba Buena book of poems—map out precisely how her Fanonian ideology evolved in tandem with her admiration for global leftist movements, from the Young Lord’s internationalist rhetoricFootnote 73 to the Cuban Revolution. But it was the Cuban intervention in Africa that was perhaps most impactful to Esteves. If Algeria had become the initial instigator of African decolonization in the 1960s, as Fanon asserted, the Cuban-assisted victory of Angola became a 1970s example of what African states could accomplish for the global left after Algeria. As historian Piero Gleijeses points out, Cuba’s victory in Angola in 1975 was pivotal in giving hope to Black South Africans and even forced the United States to reevaluate its favorable policies toward a racist white-minority rule.Footnote 74 Fanon is relevant to this context because by the end of the 1970s, as Popescu argues, “Fanon’s idea of violence as a cathartic reappropriation of the activist’s abused self and as a means of recapturing the pride of being black entered the South African discursive field.”Footnote 75 Pertinent to Esteves, between 1973 when she penned her drafts—including “We” to become “From Fanon”—and the 1980s when they were published in Yerba Buena, not only was this Fanonian ideology setting in, but Cuba had defied US foreign policy by heavily financing Nelson Mandela’s party, the ANC.Footnote 76 The fact that Esteves’s Fanon poem features right next to one dedicated to Cuba’s revolution in “for Fidel Castro”Footnote 77 appears less coincidental in this context, as does the fact that in her “1st poem for Cuba,” the “we” of her initial draft for “From Fanon” features in every stanza, Footnote 78 calling for a global working-class unity. I mention this historical context to delineate the ways in which Fanon becomes, if not a center of gravity, certainly a feature of this leftist apparatus in Esteves’s drafts-cum-published poems, including “Fighting Demons.”

In her unpublished 1973 poem “We,” the differences between the original and the published version map the growing Fanonian internationalism influencing Esteves’s writing process.Footnote 79 As we can see in Figure 2, in the first stanza of her unpublished 1973 version, “we cannot remain deaf to the anguished screams from our comrades” changes to “internalizing anguish from comrades” in the published version (4). Compellingly, the detachment of a passive observer in seeing others’ “anguish” becomes “internalized,” rendering the observer an active participant in the struggle, just as much as Fanon was in Algeria. Similar is the change from “our” oppressor to “the” oppressor, or the shift from “as slaves we lost our identity” (emphasis added) to “we lost identity” in the stanza where Esteves ties Puerto Rican identity back to the era of the plantocracy. The omission of the possessive adjective “our” unlinks the poem from a nationalist Puerto Rican movement. Rather, this oppressor becomes the planetary oppressor of the global south. After all, as the poem asserts, the oppressor has “an international program,” one that Nuyoricans can attempt to dismantle “within the monster’s mechanisms.” The sidestepping of pro-nationalism that has usually defined Nuyorican poetry seems to be, if not directly shaped by Fanon in this instance, at least acquiescent to his philosophy. As Fanon pushed for an anti-nationalistic view of emancipation in Algeria specifically, he also endorsed a pan-African unity allied against France: “There is no common destiny between the national cultures of Ghana and Senegal, but there is a common destiny between the nations of Ghana and Senegal dominated by the same French colonialism.”Footnote 80 Instead, Fanon collapses arbitrary nationalisms—carved out by colonial powers—and redirected them toward what he termed in a posthumous essay “international colonialism.”Footnote 81 Using Algeria in counter-relation to France in the essay “Algeria in Accra,” Fanon links this Algerian oppression to other forms of coloniality, including apartheid, to mobilize African decolonization “whether among the Senegalese, the Cameroonians, or the South Africans.”Footnote 82 This particularity used for a generality will go on to influence Esteves’s anti-apartheid poetry.

Figure 2. “We” poem. Courtesy of the Sandra María Esteves Collection, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Library & Archives Hunter College, CUNY, New York, NY.

Inverting Fanon, Esteves uses South African apartheid to mobilize a third world resistance in “Fighting Demons”:

South Africa/ New York

What is the difference of the face of greed?

How does it construct its smile

From the burning bones of Vietnamese families

Or the music of Chile

Of a million martyred students

In a stadium filled horror

That witnessed the slashing of the poet’s tongue

The murder of Victor JaraFootnote 83

Expanding from Fanon in this instance, Esteves includes more regions in the global south than just Africa. Here, Southeast Asia and Latin America also feature, as Chile and Vietnam become integrated in the quest to free South Africa and not unlike the way Fanon would heed Africans to be mindful of lessons to be learned from failed Latin American revolutions of the nineteenth century.Footnote 84 This Fanonian influence, moreover, places Esteves in conversation with other internationalists. Egyptian internationalist Radwa Ashour similarly likens the 1973 massacre of Chileans and singer Víctor Jara to the necropolitics affecting both Egyptians and mobilized Puerto Ricans during the civil rights era.Footnote 85 Similarly, Esteves’s mention of places of terror such as “Soweto” echoes a pictural technique found in a South African internationalist artist and contributor to the original Art contre/against apartheid, Gavin Jantjes. In her mention of “Soweto,” Esteves evokes the 1973 photograph by South African journalist Sam Nzima of the death of thirteen-year-old Hector Pieterson in the arms of his rescuer, Mbuyisa Makhubu, and mourning sister, Antoinette Sithole.Footnote 86 This same image that sent shockwaves across the globe appears in Jantjes’s A South African Coloring Book (1974–1975), as figure 3 shows, along with images of Sharpeville and other horrific massacres memorialized in photos.Footnote 87 Compellingly, both Esteves and Jantjes subordinate text to image through this technique, representative of South African artistic methods before the apartheid was dismantled.Footnote 88 Moreover, this technique was popular among internationalists at the time and thus Esteves’s poem finds itself dialoguing with a third world artistic methodology.Footnote 89 Although I do not claim that this technique is directly related to Fanon, an artistic relation between third world intellectuals was paramount for decolonization in Fanon’s idealization of the process,Footnote 90 and in any case is an internationalist gesture that Esteves perhaps adopted when Art Against Apartheid emerged.

Figure 3. Gavin Jantjes contribution to Art contre/against apartheid, from Livre sur l’Afrique du sud. Photo by the author, 2021.

A more obvious Fanonian trace in Esteves, however, is the shift Esteves’s poetry takes from despair to hope, discernable through 1970s drafts of poems. The unpublished poem “I am Puerto Rican” is plagued with “a lifetime of tragedy.” The lines “I do not know/ where I am going” or “I walk in a void of emptiness/ for I have accomplished no purpose” are nihilistic; a sentiment that is later dropped from Yerba Buena. Instead, Esteves’s poem “Whose War Cry Will Be Heard Tomorrow?” ends with a vision of peace. When conflict ends, “When there is no more land to plow/ or weapons to be made,” this era will bring forth “life back to the earth” and “design new cities,” “with reverence to brotherhood.”Footnote 91 This hopeful ideology bears traces of Fanonian discourse of hope to be found in the decolonial. In fact, intellectuals of the Cold War era “returned compulsively to Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth in search of a blueprint to produce revolutionary futures.”Footnote 92 One of those hopeful models intellectuals refer to is when Fanon summons the Algerian past as a tool to build futurity: “When the colonized intellectual writing for his people uses the past he must do so with the intention of opening up the future, of spurring them into action and fostering hope.” Footnote 93 Fanon is referring to the “men and women fighting French colonialism in Algeria” who should not turn a folklorist nostalgia against French negation, but rather use national culture to “shape the future.”Footnote 94 Similar to the previous argument, Fanon wills decolonized nations to rediscover the complexities of their traditions but with a memory of the relatable ways the coloniality exerted its power.

In this way, Esteves’s “We” evolves into “From Fanon” to dialogue with this Fanonian philosophy in more ways than the obvious. In returning to this poem, I offer a stanza from the draft to elucidate how it changes:

We are a multitude of contradictions

reflecting our history oppressed controlled

once free folk too long ago

remnants of that time interacting in our souls,

I present the stanza because this section is almost unchanged in the published version, but with one notable difference. The 1980 version cuts the phrase “long ago” as this omission moves this liberationist poem into a present state of mind, or rather into a continual present made evident also in the change from “we fled to escape” to the continuous present tense in the phrase, “we flee escaping.” Footnote 95 This change indicates that decolonial temporality is coterminous with the present, ever-evolving, and hopeful. Although this example and those above do not constitute an exhaustive exploration of a Fanonian ideology, some of Esteves’s earlier thinking reflected in these drafts show the evolution of an internationalism that is perhaps less concerned with a French colonialism than with a Fanonian decolonial rhetoric. And yet, this French example for Fanon is significant as his continual traces in Esteves’s work will show. I turn now to consider the ways in which French colonial violence becomes a catalyst in Fanon to unite the masses and in turn a rhetorical strategy in Esteves’s work.

Although most of Esteves’s poems are a call for life and harmony, there are a few identifiably Fanonian traces of justified violence. In the context of “prisons,” “disease,” and “welfare,” the poem “Whose War Cry Will Be Heard Tomorrow?” asks “When will children exchange/ celebration for war.”Footnote 96 Similarly, her poem dedicated to Fidel Castro pledges “infinite rebellions,” not unlike Fanon’s assertion that Algerians and Moroccans respond to French colonial violence in kind.Footnote 97 As is well known, Fanon also justifies anti-colonialist movements with violence but does so through the poetic. In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon cites the long poem of Guinean Keita Fodeba, a veteran hero of French wars who later resists calls for him to thwart anticolonial uprisings. When Fanon introduces this martyr, he states that “there is not one colonized subject who will not understand the message in this poem.”Footnote 98 In a passionate plea, Fanon uses this poem to “prepare [the colonized] to fight.” But my point is less that Esteves and Fanon share a penchant for violent rebellion and rather that they seek unity through a focus on the relatability of third world oppression. For Fanon, French colonial violence serves to awaken anticolonial sentiment in all its global iterations. Guinea, Fanon states, “is Sétif in 1945, Fort-de-France, Saigon, Dakar, and Lagos.” Conversely, for Esteves, South African apartheid in “Fighting Demons” evokes Dutch and British colonialism but also French, Spanish, and Italian colonialism in places like Puerto Rico, Beirut, “Ireland or Ethiopia.”Footnote 99 That Fanon and Esteves both share the genre of the poem as a decolonial tool is not so much a response to French colonialism, but rather Esteves’s reaction to a Fanonian discourse of internationalism, which, in turn for him, resulted from French colonial violence. As these examples illustrate, Esteves’s archive sheds light on a Fanonian ideology inherent in Esteves’s Cold War era poetry. This ideology becomes more apparent when read through the context of her participation in Art Against Apartheid, an event that did not end with the publication of the anthology in which she appears.

Esteves’s Fanonian traces of French colonial contestation become more understandable when read through her Art Against Apartheid participation, including her public engagement. Returning to her archive, copies of publicity feature various ways she engaged with the issue, honing her internationalist focus. As Figure 4 shows, on October 16, 1984, Esteves shared the stage with renowned US multiethnic poets, such as fellow Latina Martha Quintanales, fellow Bronx native Safiya Henderson-Holmes, Hettie Jones, Meena Alexander, and Kimiko Hahn, among others.

Figure 4. Art Against Apartheid schedule and Art Against Apartheid poster. Courtesy of Larry Shore and Carolyn Somerville, Hunter College, New York, NY.

So committed was Esteves that the same year in which fellow Nuyorican founder Pedro Pietri and other poets formerly affiliated with the Young Lords shied away from the political symbols of solidarity with the global south,Footnote 100 Esteves remained staunchly aligned. On February 28, 1997, Esteves joined Young Lords Felipe Luciano, Junot Díaz, Amina Baraka, and others for a live music and poetry reading in support of racial justice at the Martin Luther King Jr. Labor Center. As Figure 5 shows, the poster for the event—called “Uprising!”—features not only two raised Black fists reminiscent of the Black Power movement, but also the silhouette of the Art Against Apartheid poster from thirteen years earlier. In 1994, Esteves also featured in the Young Lords Inc. poetry reading at the James Weldon Johnson Community Center. Most recent was her 2009 reading from her Undelivered Love Poems (1997) for the Young Lords Party’s fortieth anniversary.Footnote 101

Figure 5. Uprising poster and Young Lords Inc. poster. Courtesy of Centro, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, New York, NY.

I have shown how Art contre/against apartheid reveals the ways that Esteves’s project generates a genuine South-South axis through a language of internationalism at times traced back to Fanon. Although there is undoubtably more to be elaborated regarding a Fanonian philosophy that shaped Esteves’s internationalism—including the gender roles Fanon attempted to decolonize in a patriarchal system in “Algeria Unveiled” beyond the scope of this article—this analysis seeks to foment further discussion on the global aims of Nuyorican poets within this African decolonial context. Yet, in addition to these traces, Esteves’s involvement with a French-based exhibit is not devoid of its own internal conflicts, as a critique of the project’s introduction by Derrida heightens the contradictions that emerge when Latinx writing engages with African politics in the “world.”

Latinx Literature and a South-South Relation

I end this analysis by considering what happens when a Latinx poem, such as that of Esteves, enters world literature along with its portrayal of African decolonial politics. I thus place the earlier discussion regarding Esteves’s “Fighting Demons” alongside responses to Algerian deconstructionist Derrida and his foreword to the Art contre/against apartheid project. Although this scholarly quarrel is well known, I would like to assess how Derrida’s original foreword creates certain contradictions for a Latinx writer engaged with African political liberation, specifically those of Fanon’s Algeria. This gap goes hand in hand with a dearth of information regarding Esteves’s involvement in this French-based project and a lack of critical analysis of her internationalism in Africa in general, made worse, Patricia Herrera explains, by the poetry movement’s (and criticism’s) usual snubbing of Nuyorican women writers.Footnote 102 Despite the contradictions in Art Against Apartheid, Esteves’s involvement in this project and Algarín’s inclusion of “Tangiers” in his Nuyorican poets’ anthology bolster an argument to be made about the ways coloniality works within the best intentions, along with some Fanonian hope for the future.

In a debate where Africanist new historicism squared off against French deconstruction, Derrida included his 1983 foreword in Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s 1985 special issue of Critical Inquiry, “‘Race,’ Writing, and Difference.” Later that year, McClintock and Nixon published a response accusing Derrida of obscuring African episteme. Derrida once expressed excitement about including his essay in this special issue on race because he was, he admitted to Gates, an African.Footnote 103 But “Le dernier mot du racism,” his foreword for Art contre/against apartheid, McClintock and Nixon argued, had less to do with an internationalist realpolik that would include Derrida’s native Algeria and the racial language of the third world than with the seduction of a deconstructive idea of the “divisiveness” of language—“apartheid,” in this case.Footnote 104 At the core of the issue is that, in McClintock’s and Nixon’s estimation, Derrida’s analysis of apartheid was “diffused” and “deficient” in African history. Specifically, they take aim at his eschewing of the nationalistic discourse that created apartheid.

In tracing apartheid’s discursive transformation from an ad hoc racist term to a legislative one, McClintock and Nixon explain how the term became rationalized when, divorced from its racial signifiers, it was made part of a palatable nationalist discourse. In 1958, South Africa referred to itself as “multinational” rather than “multiracial,”Footnote 105 which was meant to convey the necessary sovereignty of “nations” within a wider nation, whereby Black South Africans were “self-governed” territories expelled from the white state.Footnote 106 This nationalism escapes Derrida. Accusing him of a “blindness to the unfolding of the racial discourses in their historical context,”Footnote 107 McClintock and Nixon pressure Derrida to admit that his text—and its language—are situated within a discourse of power that distances the African heritage he claims and relegates the African record to an inferior position. (Derrida later refutes their accusation in his own fifteen-page response that same year.) But recalling the socioeconomic divide that separates Algarín from the Moroccans, this epistemic superficiality reflects the nationalistic isolation inherent in the French-based project despite the fact that the French Art contre/against apartheid seeks to defend a foreign population. It also reflects that being “African” or more specifically “Algerian” does not translate into Derrida’s yearning for African or Algerian specificity when engaging African decolonial movements as a French intellectual.

Different from Fanon, the coloniality at work here is that either African epistemologies elide Derrida or that French coloniality outweighs a Fanonian third world ideology. In other words, it is as if Derrida’s lack of specificity both denies the Algerian decolonial history that Fanon championed, but also goes further than Fanon in simplifying and thus omitting African history. Because I have been discussing the ways coloniality is at work in South-South relations, or Latin-African relations more specifically, I have isolated French coloniality in North Africa to assess the ways it registers and operates, however differently, in Algarín and Esteves. The case of the Art contre/against apartheid controversy perhaps disregards Algarín but weighs on Esteves’s project in a crucial way: it presents a case for how French coloniality continues operating in the circulation of minoritized literature, even if the aims are Fanonian, leftist, or third worldist. Thus, ironically, if Esteves’s Fanonian poem is contained in Art Against Apartheid—a project that is ideologically separated from Fanon via Derrida—does this project then render Esteves’s Fanonian poem (or Fanonian purpose) contradictory at best, or invisible at worst? These questions become all the more urgent when considering the waning involvement of Esteves with African decolonization in the 1990s, as African nation-states showed signs of strain. Esteves’s “Take some Dreams” in Contrapunto in the Open Field (1998), for example, reflects a burdensome revolution relegated to the next generation: the lines “Here, take some dreams/ Got more than I need” are pained and nihilistic. Or in “Puerto Rican Discoveries 38: Poem for My People,” the poem overemphasizes the desire for a decolonized world never to be via the repeated line, “I wish I could.” These poems break from Fanonian decolonization, in line with fellow Nuyorican poets’ distance from third world ideology.Footnote 108

But the invisibility of the African internationalism of writers like Esteves or Algarín in literary criticism derives from an ideological framework harnessed to the racism of latinité and distance from the methodologies of the global south. Regarding the former, an unwillingness to address either the ethnic and racial constructs that circumscribe Afrolatinidad, or other intersections outside of American studies, is still commonplace. As Josefina María Saldaña-Portillo has argued, the “compartmentalization of the study of race and ethnicity” in Chicanx/Latinx studies is evident in these fields’ tendencies to devote themselves exclusively “to colonial annexation and labor migration,” thereby producing a reductive representation of Latinx identity and history.Footnote 109 Locating a lack of interest in African affairs in Latinx studies, late Puerto Rican scholars Miriam Jiménez-Román and Juan Flores held that even “the word ‘Afro-Latin@’” can be viewed as an expression of long-term transnational and world events that include “the growth of African liberation movements as part of a global decolonization process.”Footnote 110 It is perhaps the lack of this South-South paradigm that Jiménez-Román and Flores call for that also distances the postcolonial from studies on Latin America and its diaspora.

The Fanonian call to expand earnestly into African epistemologies is hopeful. Internationalism comparatists Vadde and Vaughn Rasberry, for instance, have steadfastly advocated for the bolstering of marginal comparativist approaches in Black studies and multilingual archival research, respectively.Footnote 111 Likewise, world literature theory has also adopted African historicism in response to anti-nationalistic approaches. In her assessment of a scaled history in world literature, Wai Chee Dimock cites the African record—via historian Philip Curtain’s assessment of a “plantation complex” stretching beyond the bounds of the United States—to explain how a recognizable trope in American literature, slavery, becomes “unrecognizable.”Footnote 112 The broadening of this geographical and disciplinary scope in Latinx studies is precisely what Esteves and Algarín exemplify for American studies. Their work, however complex it may be for considering the internationalist aims of their literature, speaks to a model of inclusion for Atlantic world, postcolonial, and world literature studies that unsettles the occidental approaches of these disciplines. More specifically, within the complexities of their writing, Algarín and Esteves’s poems begin to shape the formation of an engagement with African decolonial histories.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Vanessa Pérez Rosario and Urayoán Noel for their generous input as well as that from the anonymous reviewers.