She has arrived. The Manila public has been anxiously awaiting the opportunity to witness her exceptional art, which has won her fervent homage and ardent admiration in the world's major cities, in Paris, London, Vienna, Berlin, Brussels, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and in the East, in Tokyo, Osaka, Shanghai and Hong Kong. European and American critics have been unanimous in praising her to the skies. Her passage through these cities has been triumphant: a beam of light, a ray of Spanish sunshine before the astounded eyes of the world's most artistically sophisticated, cultured audiences, a vibrant and caressing echo of traditional Spanish music imbued with classical overtones thanks to the genius of Spain's great composers, given visible form through the incomparable expressivity of this magnificent artist. Antonia Mercé, La Argentina!! (Dorillo 1929)

With all the excitement and anticipation evinced by these words in the Manila newspaper El Mercantil,Footnote 1 the Spanish dancer Antonia Mercé Luque (Buenos Aires, 1890–Bayonne, 1936), known by many as “La Argentina,” sailed into the Philippines aboard the President Pierce on February 18, 1929, the latest stop on her new international tour.Footnote 2 She would remain in the Philippines until the end of the month, before setting a course for Saigon—currently Ho Chi Minh City—in Vietnam, continuing her journey toward the West (Photo 1). This was a pioneering world tour by a Spanish dancer, one that made available the traditional stage circuits of the Americas, and included performances in cities in Asia and Oceania that extended the impact of this dance form to new audiences. Moreover, as part of her Asian tour, the case of the Philippines is particularly interesting in terms of analyzing the impact of her work in the former Spanish colony. As a result of this visit, La Argentina paid homage to Philippine culture by creating a piece inspired by its national dance, called the cariñosa—a Spanish colonial dance—which she incorporated into her international repertoire. La Argentina arrived in Manila almost thirty years after the Treaty of Paris of 1898, which transferred Spanish sovereignty over the Philippines, leaving it to the United States.Footnote 3 The use of the English language had spread under the American influence while aspects of Spanish culture gradually lost importance. The arrival of the famous dancer, therefore, would be seen by a sector of the population closest to the former colonial power—the historical elites and Spanish descendantsFootnote 4—as an opportunity to revive and reconnect with those Spanish influences that were now arriving in the form of familiar dances, music, and songs.

Photo 1. Reproduction of the portrait of Antonia Mercé La Argentina in Bolero clásico by Mme. D'Ora, dedicated to the journal Excelsior, Manila, February 1929. Legado Antonia Mercé, la Argentina, Biblioteca Fundación Juan March, Madrid.

How can we understand the place of Spanish dance in the West at the beginning of the twentieth century, and in relation to the collapse of its colonial system that immediately preceded it? What role did Spanish dance have in the diffusion and perpetuation of the colonizing logics of the former Spanish colonies, especially through emerging cultural policies such as Hispanidad? How did Eurocentric criticism condition the configuration and interpretation of La Argentina's “Hispanic” repertoire? I seek to address these questions by examining La Argentina's political motivations in deciding to include Manila in her international tour, offer a repertoire of Spanish dance, and create a new piece in homage to the mestizo Spanish legacies in the Philippines to be performed on her return to Europe. Her motivations shed light on the place of Spanish dance in Western cultural hierarchies, considering the aspects inherited from the romanticism of Spanish culture itself as exotic and Other within the European imaginary.

In this article, I examine La Argentina's brief stay in Manila and the creation of her solo La Cariñosa as a case study of the ways that early twentieth-century Spanish dance functioned as a form of “colonial gesture,” allowing us to understand Spanish dance as both colonizing and colonized. The solo stylized the Filipino national dance for Western audiences, supposedly paying homage to the Filipino people but in fact concealing a gesture that continued the exercise of colonial power under the guise of the search for the bonds of a shared Hispanidad,Footnote 5 a new instrument of cultural policies built on a fictive unity in postcolonial Philippines. The solo, therefore, exercised the symbolic and assertive power of a Filipino Creole dance from colonial times. Alternatively, the presence of Spanish dance in this context, signified and occupied a place of “primitive Other” to Europe, exoticized and racialized in relation to the canon of European ballet and the hierarchies of Western dance since Romanticism. Conditioned by the Eurocentric system of cultural hierarchies and unveiled through the intersections of race, gender, class, and nation, La Argentina's La Cariñosa therefore allows us to analyze the place of Spanish dance as both the subject and object of colonial gestures in the panorama of transnational Modernism on the basis of the cultural legacies of Romanticism.

A series of studies have analyzed La Argentina's life and career (Rodrigo Reference Rodrigo1988, Reference Rodrigo1990; VV.AA 1990; Manso Reference Manso1993; De Soye Reference De Soye1993; Bennahum Reference Bennahum2000; Alberdi Alonso Reference Alberdi Alonso, Díaz Olaya, Lluch and Muñoz2018), studied her in the framework of the European vanguards of her time (Molins and Romero Reference Molins and Romero2008; Murga Castro Reference Murga Castro2017; Murga Castro and Marinero Labrador Reference Murga Castro and Labrador2021), and examined her interpretations within the representation of national identity (Murga Castro Reference Murga Castro, Sethi and Sebro2019) and its inflections by the notions of neoclassicism, modernism, and the folk (Franko Reference Franko2020). Her Asian tour of 1929 has attracted the attention of scholars, especially in the case of her time in Japan, given the fundamental impact she had on a young Kazuo Ohno, which determined his dedication to dance and the birth of butō—to the point of creating his reenactment Argentina Sho (Soler Gallardo Reference Soler Gallardo, Barlés and Almazán2010; Franko Reference Franko2020; De Naverán Reference De Naverán2022). However, to date, no studies have been published on the work of this fundamental Spanish dance artist in light of the frictions between the colonizing and colonized, stemming from the legacy of the collapse of the colonial system.

This study is set during the first third of the twentieth century and within the framework of the nascent cultural politics of Hispanidad. In the years of severe internal crisis due to what became known as the “Disaster of ’98,” which caused serious doubts “about the virtualities of the national or ‛racial’ identity” (Álvarez Junco Reference Álvarez Junco2017, 171), different Spanish institutions launched initiatives to maintain cultural and scientific links with the former colonies based on shared history and language. Dance, as a language of the body, can be understood as an instrumentalized manifestation of these initiatives, as a soft and noninstitutionalized cultural policy, and as an alternative to the monumental petrification of the Columbian “discovery” statuary. Deriving from the idea of the “colonial archive”Footnote 6 (De Oto Reference De Oto2011, 167), dance becomes a living archive of Hispanidad, which many dancers ended up integrating into their repertoires as a distinctive sign. My analysis of colonial gesture in Spanish dance therefore offers an approach for understanding the place of dance forms associated with the bodies that dance them, which occupy intersections of national, racial, gender, and class identities.

La Argentina's initiative stood at the crossroads of these elements, centering the “modernized” interpretation of a colonial dance on a solo identified with the “mestiza ideal.” This depiction of the Spanish mestizas from the vantage point of the Creole elites and their “María Clara dances” (named after the famous Filipino writer and politician José Rizal's heroine), became the perfect strategy for reinforcing the construction of La Argentina's artistic status as a Spanish dancer in the West—a souvenir from a supposedly nostalgic Spanish history in the Pacific. The differences in the practice of Spanish dance for diverse audiences—those in European cultural centers or former colonies, or on Spanish stages—are evidence of its unstable position within the taxonomies of traditional historiography. This situation pushed dancers such as La Argentina to apply strategies of legitimization and “westernization” of Spanish dance and to reinforce the colonial matrix of power through both metaphorical and physical movements, actions, and facts.Footnote 7 In order to understand this colonizing and colonized double condition of La Argentina's dance production, I will now analyze the construction of the Spanish national identity associated with dance, the context of reception of her dance in the Philippines, her work of documenting folk dances, and her creative process of stylization in the West, with a view toward integrating the Filipino legacy into her repertoire of recitals as a danced archive of Hispanidad.

“The Epitome of Spanish Grace”: La Argentina and the Imagination of a Danced National Identity

Accompanied by the pianist Carmencita Pérez and her manager, Arnold Meckel, La Argentina traveled to Manila to offer a series of performances promoted by Asway Strok, a local businessperson who had earlier organized tours of Asian countries by leading exponents of Western dance such as Anna Pavlova, Ruth St. Denis, and Ted Shawn (Scolieri Reference Scolieri2020, 206). The description of the public reception of the ship upon its arrival in the Port of Manila published in El Mercantil, which opens this article, illustrates the esteem to which the artist was held among the population of Spanish descent under American rule, for whom she was considered “the epitome of Spanish Grace”Footnote 8 (Dorillo 1929). The perception of La Argentina as the epitome of “Spanishness” and the embodiment of national essence was a constant in her life. She encouraged this perception in programs distributed to audiences, and it was reflected in the reviews and interviews from the places where she toured internationally.Footnote 9

La Argentina's Asian tour, like the Latin American tour before it, should be contextualized alongside other Western dancers of the time who were conducting “fieldwork,” looking for artistic and documentary sources of different types in cultures exotic to Western audiences—mainly from India and Southeast Asia, but also with indigenous American influences.Footnote 10 This interest in non-European indigeneity would also be exploited by Spanish dancers, especially Tórtola Valencia.Footnote 11 In contrast to these approaches, La Argentina distanced herself from indigeneity as a source for her dance and embraced instead the legacy of the Spanish colonial powers on the islands. This approach, manifest in her incorporation into her repertoire of other pieces, developed as “homages” to dances from other former colonies: Cielo de Cuba, Cuba (Rumba), Jarabe mexicano, and Suite Argentina. These were the only works within her repertoire that were not inspired by Spanish folk or imaginaries, and thus can clearly be interpreted as a desire to embody the nascent concept of Hispanidad.

By the time La Argentina reached the Philippines, the hegemonic circles of Western culture had already legitimated her artistic vision. Her critical and public success, especially following the founding of her company, Les Ballets Espagnols—a French name clearly replicating Diaghilev's Ballets Russes—in the autumn of 1927, and the acclaim of her peers, had transformed her into the leading international exponent of Spanish dance. La Argentina based her own artistic contribution on the idea that Spanish dance had emerged throughout history from the stylization and distillation of various elements of folklore, flamenco, and the bolero dance of the eighteenth century. She drew inspiration from an outstanding group of Spanish literary, musical, and artistic figures in constructing an image—as she observed in an interview—of “a Spain that for many educated people, including Spaniards, is ‘more Spain’ than the real Spain” (Olmedilla Reference Olmedilla1931, 9). This “imagined community” (Anderson Reference Anderson1993) was based on a modern repertoire that combined elements inherited from the exoticized, late-Romantic view of nineteenth-century Spain with other major components of the canonical account of Spain's cultural history. Thus, her repertoire projected a vision essentially based on the casticismo (the typical and “genuine” view of the country) of nineteenth-century Madrid, Andalusian culture, the Spanish Golden Age, and artistic references to Velázquez and Goya, and at the same time moved away from the españoladas popularized during the fin-de-siècle on European stages, which, in her view, distorted the true nature of Spanish dance.

The same year as La Argentina's Asian tour, one of the main dance experts in Paris at that time, the exiled Russian critic André Levinson, published La Argentina: A Study in Spanish Dancing with Thirty-Two Plates (Reference Levinson1928), which would condition and nourish her reception by other expert critics in Europe and the Americas. In this book, Levinson drew from the exotic conception of Spanish dance that was reinforced by Romanticism: “Her indescribable success has loosened a new onslaught of Spanish dancing, the oldest and noblest of European exotics” (Levinson Reference Levinson1928, 7–8). He proposed a reading of La Argentina's dance as the story of a new “Reconquest”Footnote 12 of Christianity against the invading “Arabs,” the West over the East: “In her the spirit of the Occident triumphs anew over the lure of the Orient. She has once more reconquered Andalusia from the Arabs, and by that sign has triumphed” (Levinson Reference Levinson1928, 8). He also considered Spanish folklore to be “the first rude stammer of primitive instinct,” which, through her education and cultivation, La Argentina had “disciplined into form, by inscribing it in movements of a pure and high-bred elegance and subduing it to perfection” (Levinson Reference Levinson1928, 8). As Mark Franko has analyzed, this view was conditioned by Levinson's formulation of neoclassicism and the idea that any dance associated with a national identity would be rooted in classical and academic principles (Franko Reference Franko2020, 210). Moreover, from an ethnic perspective, Levinson was activating “colonial difference” (Mignolo Reference Mignolo2012) such that, in order to achieve sublimation and purity, Spanish dance should shed its folkloric connotations and instead be stylized and modernized.

The bonds between dance and race would be part of the rhetoric of many other critics in the early twentieth century, who explained La Argentina's performances in relation to a history marked by the Islamic past and the Roma community, and less so by African and Latin American legacies.Footnote 13 In his book Dancing in Spain, Cyril Rice would state that La Argentina's art “is the product of her race—the national soul seeking to express half-realised urges and longings” (Rice Reference Rice1930, 37). La Argentina herself would conclude her explanation of her body of work through technique and rhythm in her essay “Ce que j'ai apporté à la danse espagnole” by conferring a similar capacity to transmit the supposed spiritual and immortal substance of the whole Spanish people: “Spanish dance must be the mirror of the Spanish soul” (Mercé, Reference Mercén.d., “Ce que j'ai apporté à la danse espagnole).” Nevertheless, what is evident in these narratives is a certain whitening process, a masking that may remind us of racist policies of “purity of blood.” Ángel del Río, then professor at the Department of Hispanic Studies at Columbia University, summarized this racist vision very clearly. He, together with Federico García Lorca, Gabriel García Maroto, and Federico de Onís, was responsible for the tribute and subsequent book Antonia Mercé, “la Argentina” (1930), in which he referred to the cafés cantantes where “gitanería triumphs and jondo and flamenco are enthroned.… All this is nothing more than picturesque, but with a little cleaning up and aesthetic dignity it can become something transcendental” (Del Río Reference Del Río, Río, Maroto, Lorca and Onís1930, 7). This quotation reveals the vision of many of the writers and thinkers of the time who supported La Argentina's creative processes, in which they saw an intellectualization of Spanish dance that elevated it above the flamenco versions popularized by Roma dancers. In this sense, Rice pointed out how some Spaniards felt “that Argentina is unable fully to exploit the gypsy style, and there is no doubt that she is primarily a classic dancer” because she might have “certain inhibitions which prevent her from being completely possessed by the enraged fury and ardour which seizes the flamenco” (Rice Reference Rice1930, 43).

La Argentina, her Ballets Espagnols collaborators, and the critics who supported her artistic contributions sought to sell the European public an “authentic” and “real” Spain, achieved by eliminating what they considered grotesque and crude movements and gestures, and distilling and stylizing them. This procedure was explained as wanting to “legitimize an intention. Mine was to preserve popular dance's essential character and sensuality while eliminating all crude elements.… I've tried to interpret them from a less crude perspective” (Mercé, Reference Mercén.d., “À propos de la danse espagnole”). In these texts, references to the café-concert dancer who performed “disorderly movements that she accompanied with the clatter of her castanets” (Mercé, Reference Mercén.d., “Espagne, jardin de la danse”) or the “fast paced and spasmodic” (Mercé, Reference Mercén.d., “À propos …”) flamenco-stomping illustrate a negative characterization of certain types of Spanish dance as crude and primitive. Their approach thus partially reflected this exoticized view of Spanish dance, whitening any trace of those “Other” agents—flamenco artists who came from the lower classes or were of Roma ethnicity—and thus carrying out an act of epistemic violence by “civilizing,” an instrument of domination (Bhabha [Reference Bhabha1994] 2002). Some of the texts written by La Argentina in those years, such as the one already mentioned, as well as “À propos de la danse espagnole” and “La danse espagnole telle que je l'ai rêvée,”Footnote 14 evidence her quest to recover and use Spanish dance heritage as her creative basis, and she stated that she long “fought against the false or incomplete idea of Spanish dance that has been bruited about almost everywhere” (Mercé, Reference Mercén.d., “À propos …”). That false image included “music-hall performances” and “fast-paced, spasmodic dance with flamenco shoes” because “in most people's eyes, Spanish dance excludes classical dance, the danse d’école, and worse still, has no other merit than calling attention in the most brutal way possible to the spectator's sensitivity” (Mercé, Reference Mercé Luque and Paravicinin.d., “À propos …”).

On some occasions, La Argentina expressed her surrender to colonizing logics: “We are like Orientals, no matter how much we civilize ourselves” (Olmedilla Reference Olmedilla1931, 9). However, at other times, she reacted against being seen as the colonized, claiming it was possible to transcend the representation of national identity: “It is perfectly possible to be human, and therefore international, without speaking any other language than that of your country” (Mercé, Reference Mercén.d., “Les danses d'Espagne”). She also tried to refute the colonizing perception of herself through invocations of classicism and by drawing on class differences, a strategy that she would resort to in her approach to Filipino folklore. She could not escape certain paradoxes that arose as a result of these conflicting readings of artistic hierarchy and ethnic origin, which created in her a double condition of the colonized and the colonizer: “Although its sources are essentially popular, or precisely because of that origin, Spanish dance can and must aspire to a nobler life; and we must not confuse what is ‘popular’ and what is ‘low’” (Mercé, Reference Mercén.d., “La danse espagnole telle que je l'ai rêvée”).

As these examples illustrate, the tensions between crude and refined, vernacular and universal, and traditional and modern, and the links between modern and colonialFootnote 15 formed the backdrop of the approaches and influences that permeated La Argentina's work and its interpretations by critics and scholars. For as much as she sought to “distill” and “stylize” Spanish dance, according to the power relations that dictated the circulation of dance trends in 1920s Europe, and in accordance with the “logic of the dominant scale” (De Sousa Santos Reference De Sousa Santos2010, 23), Spanish dance's dependence on the local and the vernacular precluded it from anything but a marginal consideration. To sum up, in a European context, and primarily in relation to Paris as the center of Western cultural circuits in the 1920s, La Argentina's perspective and vision of Spanish dance reveal the position of a colonized subject in the vision of a romantic traveler. However, as I will discuss, at the same time, the processes she employed in her tour of the former colonies evince an opposite stance: that of a cultural appropriation that seeks to identify links with colonial heritage in the former colonies. Through the aforementioned processes of stylization, modernization, or whitening, she incorporated these colonial dances—those from the Philippines as well as other former colonies such as Mexico, Cuba, or Argentina—into her repertoire and her vision of what she believed so-called Spanishness and the Spanish national identity should be. Thus, the “colonial gestures” applied to her own dance in terms of “modernization” and “stylization” would, at the same time, constitute the appropriative strategy of the dance from the former colonies under narratives of Hispanidad.

Toward a Danced Archive of Hispanidad: Legitimization Strategies through the Fieldwork in the Philippines

After the Crisis of 1898, officially recognized cultural visits to the Philippines by prominent figures in the arts and literature were regularly organized with the objective of preserving the Spanish legacy (Luque Talaván Reference Luque Talaván2013, 78–84).Footnote 16 Over time, the potential for cultural diplomacy offered by journeys such as these would become actual policies of Hispanidad, based on the narrative of maintaining common cultural ties of a shared past. The work of La Argentina fits as a perfect precedent. She would be the first person to receive the Lazo de la Orden de Isabel la Católica, the highest award of the Second Spanish Republic, in December 1931, barely a few months after the proclamation of the new regime and the flight of King Alfonso XIII. The new left-wing government honored her for her role as “cultural ambassador,” thus lending its support to countless performances throughout Europe, Asia, and the Americas.Footnote 17

Other Spanish visitors were invested in maintaining a dynamic in theatrical circuits that, for many years before the beginning of American rule, had brought Spanish companies and a tradition of Spanish drama to the Philippines. Although what was known as “seditious or nationalist theatre” (Lapeña-Bonifacio Reference Lapeña-Bonifacio1972, 1) was censored and persecuted by the American authorities after 1898, many Spanish plays and zarzuelas (Spanish operettas) continued to be staged in theaters such as the Zorrilla, the Cervantes, the Águila, the Comedia, and the Teatro Nacional, the latter of which converted into the Manila Grand Opera House in 1902 (Laconico-Buenaventura [Reference Laconico-Buenaventura1994] 1998, 60).Footnote 18 La Argentina's program in Manila consisted of tried and tested pieces that had always been a success. An analysis of newspaper reports (Anonymous 1929a; Dorillo 1929) and surviving programsFootnote 19 for various destinations on her Asian tour reveals that her performances included individual works from the bolero dance and solo dances scored by the most famous Spanish composers, comprising her iconic repertoire. Thus, La Argentina emerged as the incarnation of what critics considered “the pure art of the race,” in descriptions replete with cliché (Anonymous 1929b). These qualities were associated with the stereotype of what is “Spanish,” the existence of the exoticism of an “Iberian essence,” the arbitrary connection between the Spanish dancer and Andalusian “grace,” and the idea of “Castilian majesty”: unquestionably an amalgamation of colonial elements that permeated La Argentina's reception in Manila. Many times, her shows showcased the veracity of her dance's roots not only through the choice of music with Spanish flavor but also in the authenticity of the costumes and accessories. Acquired on her travels and through her fieldwork, these elements simultaneously counteracted and legitimized the staging of her stylized and modernized choreographies.

The Spanish-Filipino society of Manila was very enthused by La Argentina, as shown by many articles and letters, such as the one that the Philippine Music Association addressed to Strok, thanking him for her visit.Footnote 20 The Spanish-Philippine Society of Manila paid homage to her at the Casino Español, an institution founded in 1866 as a center for Spanish culture and society (Photo 2).Footnote 21 In the photographs of this event attended by the Spanish Consul Emilio de la Mota, she posed surrounded by other personalities from Manila (Anonymous 1929c).Footnote 22 The warm reception that Manila society afforded La Argentina presented her with an ideal opportunity to learn about Philippine culture, an interest accentuated by her desire to build on the legacies of a shared past. She expressed her happiness at being in Manila, where everything seemed familiar to her: “I feel that I've come home, to my own country, that I'm among my people” (Dorillo 1929).

Photo 2. Antonia Mercé La Argentina and Carmen Pérez at her homage in Casino Español (Anonymous 1929c). Legado Antonia Mercé, la Argentina, Biblioteca Fundación Juan March, Madrid.

These familial ties, through which La Argentina sought connection, also prompted her to document folkloric and traditional Philippine dances of Spanish origin. In this study she was helped by the Philippine dancer Rosa G. Jiménez Rivera,Footnote 23 with whom she had occasion to share knowledge about different Philippine and Spanish dances (Gómez-Rivera and Villaruz Reference Gómez-Rivera and Villaruz2017, 210). It seems that, from their exchanges, La Argentina learned of various examples of the diversity of Philippine dances: the cariñosa, considered the national dance; the binasuan (a popular dance on the sugar plantations, in which a woman dances with a glass of wine on her head and a glass of wine in each hand without spilling a drop); the Muslim singkil dance from the island of Mindanao; and the pandanggo and other dances from the Ifugao province and the Tinguian culture (Reyes Tolentino Reference Reyes Tolentino1927; Alejandro and Abad Santos-Gana Reference Alejandro and Santos-Gana2002; Namiki Reference Namiki2016).

An appreciation of the wealth of Philippine dances had already prompted incipient academic study, leading to a notable work of documentation undertaken by Francisca Reyes Tolentino, later known as Francisca Reyes Aquino. This physical education teacher at the Philippine Women's College published her book, Philippine Folk Dances and Games, in 1927. Her findings contributed to fostering knowledge and encouraging the conservation of intangible Philippine heritage for generations. However, as Declan Patrick notes, Reyes Tolentino produced knowledge about indigenous Filipino dances by assuming a “westernized” gaze and methodology (Patrick Reference Patrick2014, 402–403). Moreover, as a recent article by J. Lorenzo Perillo argues, Reyes Tolentino's work, which departs from the study of Louis H. Chalif's The Chalif Text Book of Dancing (1914) and Frederick O. England's Physical Education: A Manual for Teachers (1919), is crucial for understanding the construction of “authentic” Filipino identities and the “Filipinization” of the colonized body (Perillo Reference Perillo2017, 124). According to this study, although Reyes Tolentino's contributions defined the foundations of the “nationalist period of Filipino dance history” through her rescue of national folklore, her techniques—imported from Russian ballet as a form of “lingua franca”—continued to subordinate these materials to Western forms, thus maintaining similar colonizing dynamics.Footnote 24

It was with Reyes Tolentino that Ted Shawn documented Philippine dances in 1927, two years before La Argentina's visit. Some of the American dancer's conclusions concerning his stay are striking. He began by warning: “To be quite frank—except for the Igorots—the Filipinos had never in any way stimulated my interest, and thus, unpatriotically, I had neglected our own protectorate in the Orient for those other places whose people seemed to be more fascinating, or more talented” (Shawn Reference Shawn1927, 34). Moreover, he stated that “there is no dance art among the Filipinos at all. They have no native drama or theater and apparently no interest among the people in dancing as an art. In the past they have depended upon such performances as came over from Spain and the dancers therein, and the only instruction in stage dancing in Manila is by Spanish teachers” (Shawn Reference Shawn1927, 36). Shawn also considered that “collectively, the Filipino is on a low scale artistically, both in creativeness and appreciation.”

As part of his research in Asia and Oceania, Shawn had traveled to the Philippines with Ruth St. Denis and attended various performances by local groups, a function in the abovementioned college, and two performances at the home of a young high-society lady in Manila, Victoria López, and her brother, which included a performance of the cariñosa. Shawn described this dance with Spanish colonial roots, illustrating the text with three snapshots of the López siblings’ performance: “This dance has many attractive flirtatious movements in it—with fan and with handkerchief— … and is also danced to a waltz of Spanish character. It has more variety and charm than the group dances, but remains in the Folk dance class” (Shawn Reference Shawn1927, 35). It was precisely these dances of Spanish colonial origin that Strok—the manager who, let us recall, would organize La Argentina's tour two years later—advised Shawn to perform during his stay in the Philippines (Scolieri Reference Scolieri2020, 217). However, the American choreographer's activity in the Philippines was mainly oriented toward the observation and study of local dances, and his testimony, published in the aforementioned article of 1927, was collected two years later in the book Gods Who Dance (Shawn Reference Shawn1929, 163–177).Footnote 25 Unlike Shawn, La Argentina attended to fieldwork with a respectful and dignified attitude to legitimize the authenticity of her approach to the Philippine legacy, though in this way she evoked certain colonial impulses.

Thus, fieldwork became a fundamental base for the construction of a living colonial archive, the collection, and documentation of material and immaterial traces of dances of the former colonies. These included study with Philippine experts, filming dance examples, and the acquisition of traditional garments. Moreover, the choice of the cariñosa among the immense variety of Filipino dances evidences the interest in emphasizing the connection with the Spanish past in the islands. In the late 1920s, the most popular Philippine dances in Manila were marked by the influence of Spain and the other territories colonized by Spain since the imposition of colonial rule over the islands. This feature contrasted with the wide diversity of indigenous dances that had survived in the extensive territory of the country, composed of more than seven thousand islands. Colonial-period dances such as the minuet, the cachucha (called the katsutsa), the fandango (pandanggo), the habanera, the jota, the malagueña, the paso doble (initially known as the pasakalye), the paseo, the zapateado (pateado), and others of Western origin, such as the polka, the mazurka, the waltz (balse), and the schottische (escotis), among many others, enjoyed great popularity (Villaruz et al. Reference Villaruz, Matilac, Mijares, Pellejo and Pison2017, 5). The mixtures and Philippine adaptations of some of these fragments were termed Los bailes de ayer (dances of yesteryear) (Reyes Tolentino Reference Reyes Tolentino1993).Footnote 26 Thus, many of these dances are called de ida y vuelta (back and forth) and reveal the inherent transculturality and hybridization of the interconnections of colonial systems and the circulation of people between Europe, Africa, America, and Asia.

Nevertheless, most colonial-period dances of Spanish origin, which were associated with Manila high society and the ilustrados,Footnote 27 became known as “María Clara dances,” in honor of the heroine of José Rizal's novel, Noli me tangere.Footnote 28 Unquestionably notable among the María Clara dances is the one that La Argentina eventually included in her repertoire: the cariñosa, considered to be the national dance. In this dance, one or more pairs execute a courtship dance in which they use a handkerchief and a fan to express flirtation: “Cariñosa means affectionate, lovable, or amiable. With the fan and a handkerchief, the dancers go through hide-and-seek movements and other flirting acts expressing tender feelings for one another” (Reyes Tolentino Reference Reyes Tolentino1993, 82).Footnote 29 As with most María Clara dances, the movements are graceful and gentle, executed slowly—almost languidly—and elegantly (Villaruz Reference Villaruz2017, 145). The traditional costume for women performing the cariñosa consisted of a long silk or satin skirt without an overskirt, a richly embroidered blouse made of piña and silk fabric with bell-shaped sleeves, a shawl folded into a triangle and worn over the shoulders, low-heeled mules and an ornamental comb in the hair (Alejandro Reynaldo Reference Alejandro1978, 31). Men wore a barong Tagalog, a loose piña and silk fabric shirt with embroidered cuffs and collar, and black trousers and shoes. The music—“Count. One, two, three to a measure” (Reyes Tolentino Reference Reyes Tolentino1993, 82)—was usually played by a rondalla, a string ensemble consisting of a bandurria, a lute, an octavina, a guitar, and a bass (Reyes-Urtula, Arandez, and Tiongson Reference Reyes-Urtula, Arandez and Tiongson2017, 33). The dance began in the following way: “Partners stand opposite and facing each other about six feet apart. When facing the audience, the girls are at the right of the boys. One to any number of couples may take part of this dance” (Reyes Tolentino Reference Reyes Tolentino1993, 82).

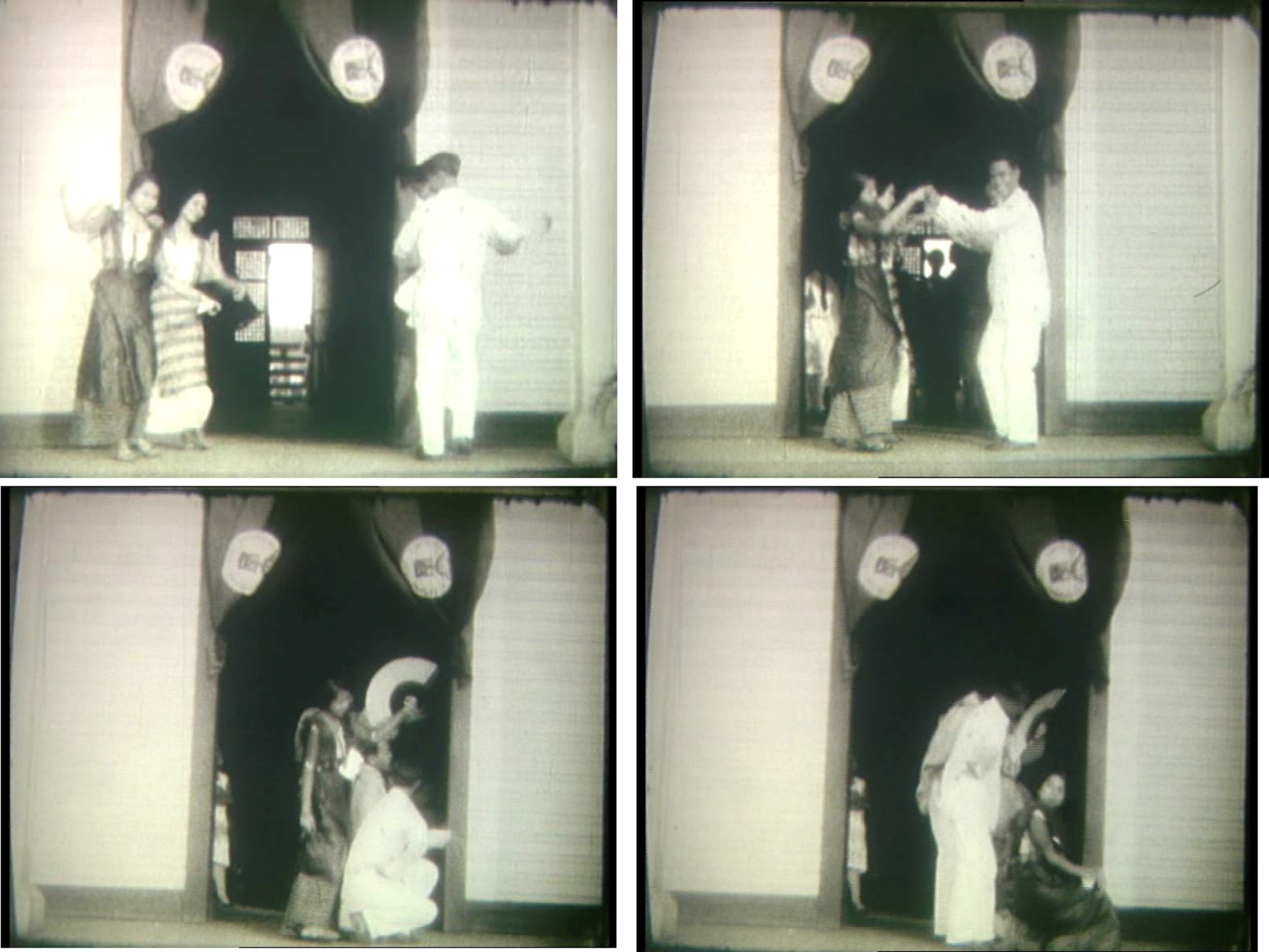

These traditional elements of dress, performance, and choreography in the cariñosa, which still persist today, are evident in a film of this piece shot by Arnold Meckel and La Argentina in February 1929, which has survived and can be consulted in the Filmoteca Española in Madrid.Footnote 30 During her international tour, they filmed various scenes of tourism and meetings with the celebrities who welcomed them at each destination. In addition, they recorded a performance by two young Filipino couples attired in their traditional costumes dancing the cariñosa in the entrance to a building, the door of which is decorated with a discrete curtain (Photo 3).Footnote 31 In order to identify the dance genre and study possible changes with respect to the documented versions, I carried out a comparative study based on written source and visual analysis between the cariñosa described by Reyes Tolentino in her 1927 book (1993, 82–87) and the dance filmed by La Argentina in 1929. Notably, the footage only captured short fragments of the various steps in a sequence lasting no more than half a minute. The version filmed by La Argentina in 1929 largely coincides with most of the movements detailed by Reyes Tolentino in her book of 1927, allowing for its identification in her collection at the Filmoteca Española as an exceptional source for the documentation and conservation of the Philippines’ dance heritage and of the cariñosa as it was performed one century ago. In total, the symbolic power of all these primary sources—especially the choreography she filmed and learned, as well as the ponyang traje de mestiza she purchased—laid the foundation for La Argentina's narrative about the authenticity of her dances and enriched the living archive that nurtured her “Hispanic” repertoire.

Photo 3. Selection of stills from the footage of the Philippine cariñosa by Antonia Mercé La Argentina and Arnold Meckel, Manila, 1929. Public domain. Filmoteca Española, Madrid.

La Argentina's Solo La Cariñosa: Subject and Object of Western Colonial Gestures

Using her process of stylization as applied to other dances, La Argentina created a piece based on the Philippines’ national dance: a solo marked both by the deep imprint left on her by all her experiences in Manila, especially from her contact with Filipino dancers, and by a colonialist subordination to the tradition of European concert dances through the incarnation of a “non-white Other” and its interpretation. On her return to Paris, she premiered this solo, La Cariñosa, in her performance at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées between April 23 and 26Footnote 32 (Vautour Reference Vautour1929), continuing to perform it on Western stages in the following years. Thus far, no film of the solo has been located, so any approach to its study must be made through other secondary sources. Some traces of these movements and resources were found in photographs of her performances kept in La Argentina's collections in Madrid and Paris (Photo 4). My understanding of the dance and analyses are supported by the comments and descriptions in the theater reviews published wherever she performed during the following five years.Footnote 33

Photo 4. Antonia Mercé La Argentina performing La Cariñosa at Aldwych Theatre, London, June 11, 1934. Legado Antonia Mercé, la Argentina, Biblioteca Fundación Juan March, Madrid.

From what I can tell from these materials, La Argentina's La Cariñosa featured elements taken from the vocabulary, the gestures, and the performing stances as well as appearance, costumes, and elements typical of the Philippines’ dance, such as the use of a fan and handkerchief, the graceful movements, and the elegant pose. Thanks to the analysis of the movement offered by Reyes Tolentino (Reference Reyes Tolentino1993, 82–87), and the seconds captured by the film shot by La Argentina, we know that, in the traditional Filipino cariñosa, the fan and, especially, the handkerchief are elements she uses to flirt with her partner by totally or partially hiding her face, to underline at certain moments the power of the gaze and to add to the courtship game in each of the roles played by the couple.Footnote 34 Despite the importance of this “flirtation” that defines the essence of the dance, the first striking aspect of La Argentina's piece is that the pair dance has become a solo. The male performance has been eliminated to become a ghostly presence, just like the colonial past to which the dance refers; we do not see it, but it is evoked by the dance of La Argentina. This strategy was not new in La Argentina's repertoire, or in the cases of other Spanish dancers who turned the folklore dances of different regions of the Iberian Peninsula—traditionally danced in pairs—into stylized solos. The aim was to achieve authenticity by wearing genuine folk costumes that were acquired in the respective places visited—as was the case with the traditional Philippine costume (Photo 5)—but the choreography was adapted for exclusive female representation and movement stylization in line with concert dance requirements in order to separate itself from the “roughness” and “coarseness” of the popular and thus approach “pure” art.

Photo 5. Antonia Mercé La Argentina dressed in a Filipino costume, Manila, 1929. Legado Antonia Mercé, la Argentina, Biblioteca Fundación Juan March, Madrid, album no. 9, p. 28.

In this regard, it is interesting to consider La Argentina's remarks on the type of energy she used when performing the choreography: “The Philippines are a bit like Spain, aren't they? In addition, their dances are exactly the same as ours, with the difference that for us, everything is energy and vivacity whereas for them, this becomes slowness and languor due to the hot climate” (Anonymous 1929d). The photographs confirm the soft and languid movement quality and show a body language motivated by a rather introverted attitude. The facial gestures are emphasized by sidelong glances and half smiles, which show a seductive, yet restrained and discreet intentionality that corresponds to the stereotype that racializes and exoticizes Oriental women and, in particular, mixed-race Filipino women.Footnote 35 The association of the cariñosa as the most iconic piece of Las danzas de María Clara directly links the interpretation of this piece with the imaginary of the mestiza ideal that La Argentina chose to evoke for Western audiences. Thus, in La Cariñosa, the female dancer, through affectionate and soft movements highlighted by the handkerchief and the smooth piña and silk fabrics, and in the absence of the male figure, embodies the mestiza ideal and flirts with the audience. Their colonizing gaze appropriates the body of the Filipino woman who performs the Creole dance represented by La Argentina.

Nevertheless, regarding the reception of the piece, it is worth reading the detailed explanation that appeared in the French newspapers, which underemphasized La Argentina's agency in interpreting this colonial dance as performed in Europe, as most of the responsibility was attributed to the critics and the spectators. André Levinson's review in Comoedia is worthy of particular mention for the significance of its impact and its descriptive and evocative capacity, which illustrates the approach of Western critics—full of clichés, layer by layer, gesture by gesture—as that colonial gaze (Photo 6).Footnote 36 Levinson thus celebrated La Argentina's latest premiere as if the audience were actually witnessing a kind of “documentary, as they say in filmmaking”—the exact reproduction of this popular dance brought back as a tourist souvenir from the Philippines, rather than a newly created piece into which the whole mentality of the time was poured. Also striking is Levinson's recourse to underlining the aristocratic aspect of the dance as coming from the Filipino elites associated with Spanish ancestry by drawing a parallel between that mestiza ideal and its French equivalent, which he identifies in the Empress of France herself: “I do not know what aristocratic grandeur persists even in the little tricks of feminine coquetry. . . . The charm of a Joséphine de Beauharnais should be of the same kind” (Levinson Reference Levinson1929).

Photo 6. Antonia Mercé La Argentina in La Cariñosa by Mme. D'Ora. Reproduced in the program of Les Représentations de Madame Argentina avec sa troupe de Ballets Espagnols, Théâtre National de l'Opéra-Comique, Paris, May–June 1929. Private collection.

After its premiere, La Cariñosa became part of La Argentina's repertoire and was performed on her tours through numerous countries in Europe,Footnote 37 the Americas,Footnote 38 and the north of Africa.Footnote 39 Its presence is recurrent in the Suites de danses, interwoven with three types of pieces: those taken from her ballets or from compositions by famous musicians, such as El amor brujo by Falla, Danza de los ojos verdes by Granados, and La corrida by Valverde; dances from Iberian folklore, such as Lagarterana, Seguidillas, and Jota; and pieces from former Spanish colonies, such as Cielo de Cuba, Jarabe mexicano, and Rumba. Among these performances, it is particularly interesting to highlight that of La Cariñosa together with Cuba (Rumba) with music by Isaac Albéniz, which was directly related to the colonial past through the title L'Espagne d'Outre mer and Tropical Spain.Footnote 40 The constant inclusion of this piece in the program between 1929 and 1935, although not as frequent as other numbers related to the Spanish imaginary, such as La corrida or Falla's solos, shows that the formula of Hispanidad was a success with audiences as diverse as those in Europe, the Americas, and North Africa. Thus, the Philippine presence—through both the performance of the solo and the reproduction of the studio photographs by Madame d'Ora—became another resource to reinforce the Hispanidad narratives wherever she toured.

Conclusion

Against the backdrop of this Philippine dance heritage, La Argentina's desire to learn and perform La Cariñosa can be first viewed, in line with her own statements, as a tribute and homage to Spanish-Philippine culture. Her documentary approach to the sources of Philippine folk dance places her among the early twentieth-century pioneers who attempted to recover and recreate the living art and culture they came into contact with on their travels. However, in this gesture of homage, it is also possible to glimpse a colonial gesture. This gesture is first seen in the framework of the incipient cultural policies of Hispanidad, which attempted to recover and strengthen cultural links with the former colonies. Second, it can be seen in a wider transnational framework of Western/non-Western frictions, which is particularly complex because of the articulation that Spanish dance itself had in the canonical Eurocentric accounts of dance. Therefore, La Argentina's strategies toward Spanish dance in the former colonies could paradoxically be considered colonizing—given that they draw on the concept of Hispanidad and recover Spanish colonial dance to recall an influence in these territories—but also colonized—given that she applied strategies of westernization or modernization dictated by Eurocentric canons to Spanish dance itself and to the recovered Filipino dance (Photo 7).

Photo 7. Antonia Mercé La Argentina with a Manila shawl, 1928. Archivo General de la Nación, Buenos Aires.

La Argentina's choice of the piece with Spanish colonial roots illuminates emerging cultural interests in the use of art as a diplomatic tool in the cultural policies of Hispanidad. These interests mobilized ideologies evoking a shared past of the Spanish-speaking nations or cultures that had been part of the Spanish empire. In the case of the Philippines, these ideas had fundamental literary precedents, and in the theatrical context were to be understood within the framework of the theater companies’ tours of the colonial period. La Argentina's work marked an outstanding milestone in this context, and she would shortly afterward be officially recognized by the government of the Second Spanish Republic. She embodied, in a nostalgic way, supposed national essences, thus personifying an imaginary and acting as a colonial archive—a living archive of historical dances of the former colonies, for whose legitimation, in the case in question, she did not hesitate to be advised by prestigious native personalities, such as Rosa G. Jiménez Rivera, and by dancers from Manila.

In contrast to what other dancers proposed—we have noted Tórtola Valencia's modernist exoticism and Ted Shawn's disdain for Philippine dance forms—La Argentina selected to adapt and perform the “loftiest,” most sophisticated, and stylized dance from a Western perspective at that time, the cariñosa. In this way, she distinguished hers from other projects of recovery and dignification—although through certain westernized suppositions—of Philippine folklore, such as the case of Francisca Reyes Tolentino, who had also paid attention to the diversity of Filipino indigenous dance. However, the objective of her dances was to search for the “authentic” and “real” with which to build up this living archive of the danced Hispanidad. This would also lead La Argentina to document the Spanish popular dances in some Spanish regions like Salamanca, Mallorca, and Asturias, but also criollo and mestizo dances in Cuba, Mexico, and Argentina.

Through such processes of appropriation under the colonial gesture, La Argentina created a repertoire of “Hispanic essences” that constructed a postcolonial “community,” equivalent to the rock-hard monumentality of a Hispanidad—the commemoration through Columbus statues and colonial architecture—now celebrated from the body, its performativity, its symbolism, and its gesture, and that marked a turning point in the use of the political power of Spanish dance from the 1930s. While this was exploited by the leftist republican government, the narrative of a Hispanidad based on traditionalism, the Catholic substrate, and more conservative leanings was operationalized within the rise of Fascism. The work of Fascist writers such as Ramiro de Maeztu (Reference Maeztu1934) would eventually be exploited during the Franco dictatorship, and the Hispanidad policies would mark other avenues of international diplomacy with countries such as Perón's Argentina, when the regime was isolated from other surrounding countries in the postwar period. The recognition of La Argentina by the Spanish republic could thus paradoxically be understood as one of the first precedents in an emergent Spanish cultural diplomacy based on this Hispanic community, later taken to the extreme with the tours of the Coros y Danzas de la Sección Femenina de Falange Española (Choirs and Dances of the Women's Section of the Spanish Falange), from Nazi Germany to Peronist Argentina. However, although La Argentina was distinguished as a “cultural ambassador,” she was never very explicit in her political beliefs and managed to avoid the attempts to appropriate her figure, which would multiply after her sudden death at the start of the Spanish Civil War.

Additionally, the colonial gesture in La Argentina's maneuver with La Cariñosa should be understood as a complex process of simultaneously conforming to and differentiating Spanish dance as an exotic genre within the configuration of dances in the West, as leading voices such as Levinson or Rice identified. For this reason, it is worth insisting on the partial agency of La Argentina, subjected to a context of interpretations by critics and the audience that conditioned the reception of this and other pieces. She sought to modernize popular dances by stylizing, distilling, and thus eschewing the rude and impure. In doing so, she aimed to achieve civility and universality and leave behind all the hybrid roots of Orientalism for the European public: the prominence of the Roma community, the recognition of the popular, the transatlantic dregs of the African slave trade, and the subjugation of the American and Philippine colonies. This is clear from many of her aforementioned texts, in which she reiterates the arguments also defended by authors such as Levinson, Rice, and Del Río. Paradoxically, in this need to banish the “picturesque,” a strategy that Del Río called “cleaning up,” the performance of La Cariñosa by La Argentina before Western audiences on her return from the Asian tour was yet another instance within a long transnational tradition of white concert dancers embodying non-white Others. In this case, she embodied the mestiza ideal, the Filipino-Spanish woman who was upper-class but racialized, thus essentializing racial difference. La Argentina's strategy to “save” those popular dances from oblivion as an example of a living history of that “Spain of Goya surviving in the heart of the Pacific” actually redefined and controlled them from the West, rewriting them into the colonial narratives that longed for a shared past. In the end, although the term cariño is defined in Spanish as both “affection” and “nostalgia,” the feelings to which La Argentina appealed when looking at the archipelago only masked the perpetuation of the logics with which she, a self-defined “Spanish dancer,” sometimes played and other times attempted to circumvent.