1. Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by neurocognitive [Reference Bora, Yucel and Pantelis1, Reference Bora and Özerdem2] and functional [Reference Huxley and Baldessarini3, Reference Gitlin and Miklowitz4] deficits which are a core feature of the disorder. However, a marked clinical [Reference Goldberg, Harrow and Grossman5, Reference Bauer, Andreassen, Geddes, Vedel Kessing, Lewitzka and Schulze6], neurocognitive [Reference Roux, Raust, Cannavo, Aubin, Aouizerate and Azorin7, Reference Jiménez, Solé, Arias, Mitjans, Varo and Reinares8] or functional [Reference Reinares, Papachristou, Harvey, Mar Bonnín, Sánchez-Moreno and Torrent9, Reference Solé, Bonnin, Jiménez, Torrent, Torres and Varo10] heterogeneity has been reported, in a way that, at one end, some patients with BD seem to reach a level of psychosocial [Reference Solé, Bonnin, Jiménez, Torrent, Torres and Varo10] and neurocognitive [Reference Burdick, Russo, Frangou, Mahon, Braga and Shanahan11, Reference Simonsen, Sundet, Vaskinn, Birkenaes, Engh and Faerden12] functioning similar to that of healthy subjects, in contrast, at the other end, with individuals who show a severe neurocognitive and functional impairment [Reference Latalova, Prasko, Diveky and Velartova13, Reference Tohen, Zarate, Hennen, H-MK, Strakowski and Gebre-Medhin14].

As with BD, schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder which is also associated with high levels of neurocognitive and psychosocial impairment [Reference Green and Harvey15, Reference Green16]. Moreover, it has been shown that BD and SZ share a substantial genetic risk, although there are also specific loci which are responsible for the phenotypic differences existing between both disorders [Reference McQuillin, Boocock, Stahl and Pavlides17]. Thus, the comparison of the neurocognitive and psychosocial functioning of patients with BD and SZ has not only clinical interest, but it is also of relevance in order to establish possible shared pathophysiological mechanisms.

It has been suggested that patients with BD with a history of psychotic symptoms (BD-P) could constitute a phenotypically homogeneous subtype characterized by a greater neurocognitive [Reference Bora, Yücel and Pantelis18, Reference Buoli, Caldiroli, Cumerlato Melter, Serati, de Nijs and Altamura19] and functional [Reference Dell’Osso, Camuri, Cremaschi, Dobrea, Buoli and Ketter20, Reference MacQueen, Young and Joffe21] impairment. Thus, some authors have suggested that BD-P could occupy an intermediate position between patients with schizophrenia (SZ) and patients with BD without a history of psychotic symptoms (BD-NP) [Reference Brissos, Dias, Soeiro-de-Souza, Balanzá-Martínez and Kapczinski22, Reference Szoke, Meary, Trandafir, Bellivier, Roy and Schurhoff23]. However, a number of cross sectional studies [Reference Savitz, van der Merwe, Stein, Solms and Ramesar24–Reference Soni, Singh, Shah and Bagotia26], including those from our group [Reference Sánchez-Morla, Barabash, Martínez-Vizcaíno, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Balanzá-Martínez and Cabranes-Díaz27–Reference Jiménez-López, Sánchez-Morla, Aparicio, López-Villarreal, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Rodriguez-Jimenez29], did not find any relevant difference of neurocognitive and functional performance between BD-P and BD-NP, showing only subtle differences, and circumscribed to certain neurocognitive domains, such as working memory [Reference Jiménez-López, Aparicio, Sánchez-Morla, Rodriguez-Jimenez, Vieta and Santos28], or to specific areas of functioning, such as financial issues or occupational functioning [Reference Jiménez-López, Sánchez-Morla, Aparicio, López-Villarreal, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Rodriguez-Jimenez29, Reference Caldieraro, Sylvia, Dufour, Walsh, Janos and Rabideau30].

To the date, most longitudinal studies have shown stability in the neurocognitive deficit of patients with BD [Reference Bora and Özerdem2, Reference Santos, Aparicio, Bagney, Sánchez-Morla, Rodríguez-Jiménez and Mateo31–Reference Tabarés-Seisdedos, Balanzá-Martínez, Sánchez-Moreno, Martinez-Aran, Salazar-Fraile and Selva-Vera33]. Similarly, no progression of the functional deficit has been found [Reference Demmo, Lagerberg, Kvitland, Aminoff, Hellvin and Simonsen34, Reference Martino, Igoa, Scápola, Marengo, Samamé and Strejilevich35]. Nevertheless, it cannot be dismissed the possibility of the existence of a subset of patients with BD showing a progression of neurocognitive or functional outcome [Reference Robinson and Ferrier36, Reference Rosa, Magalhães, Czepielewski, Sulzbach, Goi and Vieta37]. In this regard, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have pointed out that the neurocognitive and functional trajectory may be mediated by the clinical course [Reference López-Jaramillo, Lopera-Vásquez, Gallo, Ospina-Duque, Bell and Torrent38, Reference Sánchez-Morla, López-Villarreal, Jiménez-López, Aparicio, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Roberto39]. Thus, some studies have suggested the possibility that clinical characteristics, such as the presence of episodes with psychotic symptoms, have a deleterious effect on the neurocognitive or functional trajectory of this disorder, although there are discrepant results [Reference Dell’Osso, Camuri, Cremaschi, Dobrea, Buoli and Ketter20, Reference Jiménez-López, Aparicio, Sánchez-Morla, Rodriguez-Jimenez, Vieta and Santos28, Reference Jiménez-López, Sánchez-Morla, Aparicio, López-Villarreal, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Rodriguez-Jimenez29, Reference Levy, Medina and Weiss40–Reference Kempf, Hussain and Potash43]. Long-term studies are necessary to confirm these results [Reference Trisha, Golnoush, Jan-Marie, Torres and Yatham44].

To further extend our previous studies, we have carried out a 5-year follow-up study aimed at comparing: 1) the course of neurocognitive dysfunction in a group of bipolar patients with and without a history of psychotic symptoms and a group of patients with schizophrenia, in relation to a healthy control group, 2) the course of functional impairment in these three groups of patients in relation to the control group, and 3) the severity of neurocognitive and functional impairment of the three groups of patients. We hypothesized that neurocognitive and functional deficits have a stable course both in patients with bipolar disorder and in patients with schizophrenia. Likewise, considering our previous results, we also hypothesized that there are no significant neurocognitive or functional differences between the two groups of patients with bipolar disorder.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Sample

Participants were enrolled in the Cuenca Bipolar Disorder Follow-up Study, a prospective study carried out at the Department of Psychiatry of the Hospital Virgen de la Luz de Cuenca (Castilla-La Mancha, Spain). The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cuenca Health Area. All subjects gave written informed consent, after a complete description of the procedures and prior to enrolment in the study.

The description of the sample was extensively collected in previous cross-sectional studies [Reference Jiménez-López, Aparicio, Sánchez-Morla, Rodriguez-Jimenez, Vieta and Santos28, Reference Jiménez-López, Sánchez-Morla, Aparicio, López-Villarreal, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Rodriguez-Jimenez29]. Briefly, 100 patients with bipolar disorder type I, 50 of them who had a lifetime history of psychosis and 50 who had never presented psychotic symptoms, and 50 patients with schizophrenia were included in the study. All patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. The diagnoses were confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I). The presence or absence of a history of psychotic symptoms (delusions and/or hallucinations) was established using the SCID–I, after carrying out a comprehensive review of the psychiatric chart. Variables of the course of illness such as the number of episodes and number of hospitalizations recorded both at baseline, and during the five-year follow up, were also ascertained reviewing the medical chart.

Patients with BD were euthymic for at least three months prior to the assessments. Euthymia was defined according to the following criteria [Reference Van Gorp, Altshuler, Theberge, Wilkins and Dixon45]: a score fewer than 7 points on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and a score fewer than 6 points on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). In addition, these scores remained below that threshold in three consecutive monthly evaluations. Moreover, all patients with SZ were clinically stabilized, at least during the three months before the assessments, according to criteria used in previous studies [Reference Sánchez-Morla, Barabash, Martínez-Vizcaíno, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Balanzá-Martínez and Cabranes-Díaz27–Reference Jiménez-López, Sánchez-Morla, Aparicio, López-Villarreal, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Rodriguez-Jimenez29].

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) comorbid medical disease which can cause neurocognitive impairment, (ii) neuropsychiatric illness, other than SZ or BD, associated with cognitive impairment, (iii) drug abuse or dependence in the last 24 months, except nicotine and caffeine, (iv) a history of electroconvulsive therapy, (v) a history of brain trauma with loss of consciousness, (vi) less than six years of education, (vii) current IQ score lower than 70, (viii) refusal to sign written informed consent.

Fifty-one healthy controls (HC), matched with patients for age, gender and years of education, were enrolled in the study. In order to rule out the presence of psychiatric disorders, all control subjects were assessed with the SCID-I. The control group met the same exclusion criteria as patients, adding as an additional criterion for exclusion in this group the presence of some first-degree relative diagnosed with a severe mental disorder (bipolar disorder or psychosis). The control subjects were living in the same catchment area and had the same ethnic origin as patients.

Both patients and HC were clinical, neuropsychologically and functionally assessed at two time points: at the beginning of the study (T1), and after a five-year follow-up (T2). The same inclusion and exclusion criteria considered at T1 were used at T2, thus euthymia and stability, as previously defined, were present in all subjects.

2.2 Clinical and functional assessment

Clinical assessments were carried out using the Spanish version of the following scales: The Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS) [Reference Peralta and Cuesta46], the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [Reference Ramos-Brieva and Cordero-Villafafila47], and the Young Mania Rating Scale [Reference Colom, Vieta, Martínez-Arán, Garcia-Garcia, Reinares and Torrent48].

Functional performance was evaluated using the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) [Reference Rosa, Sánchez-Moreno, Martínez-Aran, Salamero, Torrent and Reinares49], and the function dimension of the split version of the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF-F) [Reference Pedersen, Hagtvet and Karterud50]. The GAF-F is a 100-point scale reflecting functioning which scores from 1, representing the most severe impairment, to 100, representing the least impaired individual. The FAST is a scale which was primarily developed to assess psychosocial functioning in bipolar disorder [Reference Rosa, Sánchez-Moreno, Martínez-Aran, Salamero, Torrent and Reinares49], but that was later validated for schizophrenia [Reference Costa, Massuda, Pedrini, Passos, Czepielewski and Brietzke51, Reference González-Ortega, Rosa, Alberich, Barbeito, Vega and Echeburúa52]. This 24-items scale evaluates impairment during the last two weeks in six specific areas of functioning: autonomy, occupational functioning, cognitive functioning, financial issues, interpersonal relationships and leisure time. Each item is scored on a 0–3-point scale (0: no difficulty, 1: mild difficulty, 2: moderate difficulty, 3: severe difficulty; total score ranges from 0 to 72 points), thus higher scores indicate poorer performance.

For every patient, the information was obtained from the participant, and at least, from a second source of reliable information (family, caregiver or case-management).

2.3 Neuropsychological assessment

Six neurocognitive domains, which correspond mostly to the domains included in the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery [Reference Nuechterlein, Green, Kern, Baade, Barch and Cohen53], were evaluated through 12 neurocognitive measures, as follows: 1) Speed of Processing. Trail Making Test–Part A (TMT-A), WAIS-III digit-symbol coding subtest, Category Fluency Test (animal naming); 2) Working Memory. WAIS-III digit span backward subtest, letter-number sequencing subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-III); 3) Attention/vigilance. Degraded Stimulus Continuous Performance Test (DS-CPT); 4) Verbal Learning and Memory. California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT); 5) Visual memory. Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (ROCFT); 6) Executive Functions. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Stroop Test interference, Trail Making Test–Part B (TMT-B), FAS test. The value of the Cronbach´s alpha for the six neurocognitive domains was 0.721 for speed of processing, 0.586 for working memory, 0.828 for executive function, 0.937 for visual memory, 0.826 for verbal memory, and 0.854 for attention. Additionally, premorbid IQ was determined using the vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale WAIS-III.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (Chicago IL, USA) for Windows was used for data analysis. Firstly, we examined if the study variables were normally distributed, and transformations were performed when necessary. For demographic and symptomatic variables, group differences were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (continuous variables) or chi-square test (categorical variables). For the analysis of neurocognitive performance, each measure in both T1 and T2 was first converted into z-scores based on controls´ scores at T1. Data were also transformed so that higher scores always indicated better performance. The z-scores that were obtained approached a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Scores of neurocognitive domains composed of more than one measure were obtained by averaging the z-scores of all measures in the domain. Also, a neurocognitive composite index (NCI) was calculated by averaging the scores obtained in each cognitive domain.

To assess longitudinal neurocognitive and functional performance, repeated measures ANOVA was used for each neurocognitive and functional measure including the normalized T1 and T2 values based on control´s T1 mean and standard deviation, in order to adjust each change comparison for the baseline values. Effects of group, time, and group-by-time interactions were examined. Bonferroni test was used for post hoc analyses. Scores on affective symptom scales (HAM-D and YMRS) were used as covariates when significant differences between groups were found.

3. Results

One-hundred and fifty patients (50 BD-P, 50 BD-NP, 50 SZ), and 51 HC were initially included in this study. At the end of the 5-year follow-up, 37 patients (6 BP-P, 16 BD-NP, 15 SZ) were lost. Of these, 2 patients died (committed suicide), 12 did not meet the inclusion criteria at T2, and 23 patients refused to be evaluated at T2. Similarly, 15 HC refused to be assessed at T2. We found no significant differences in demographic, clinical, cognitive, functional, or treatment variables at T1 between subjects who completed and those who did not complete the follow-up for any reason.

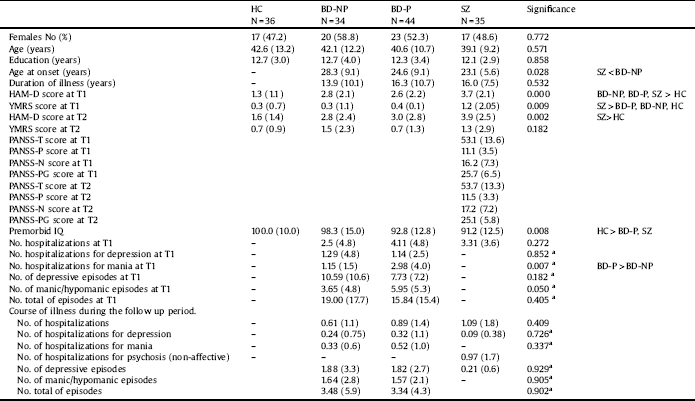

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical variables in patients with bipolar disorder with and without history of psychotic symptoms, patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls at baseline and after a five-year follow-up.

HC: Healthy controls; BD-NP: Patients with bipolar disorder without history of psychotic symptoms; BD-P: Patients with bipolar disorder with history of psychotic symptoms; SZ: Patients with schizophrenia; T1: at baseline; T2: at follow-up of five years; HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale; PANSS-T: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score; PANSS-P = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Positive symptoms; PANSS-N = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Negative symptoms; PANSS-PG = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-General psychopathology; IQ: Intelligence quotient.

aOnly BD-P and BD-NP were analyzed.

The time elapsed between the first and second assessments was 63.8 months [standard deviation (SD) = 5.2 months; range: 55–78 months] for patients and 62.4 months (SD = 8.1 months; range: 51–76 months) for the control group (p = 0.331; F = 0.953).

Table 1 shows sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients and control subjects which completed the follow-up. There were no significant differences between the four groups at baseline either for age, years of education or for gender distribution. HC had higher premorbid IQ than patients with BD-P and SZ. The three groups of patients scored higher on the HAM-D than HC at T1, although, at the end of the follow-up period, differences were only found between HC and SZ. Moreover, on the YMRS, patients with SZ scored higher than patients with BD and HC at T1.

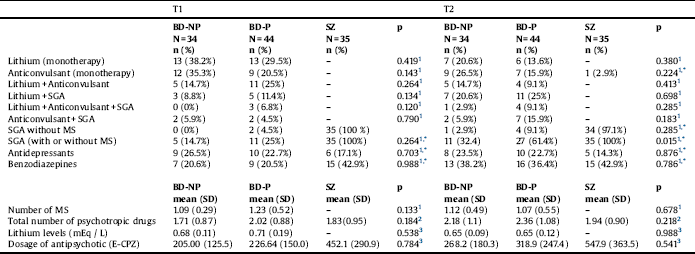

Comparing the three groups of patients, no differences were found in years of evolution of illness. Nevertheless, patients with SZ had an earlier onset than BD-NP. When we compared the course of illness between BD-P and BD-NP, at baseline, patients did not differ in number of hospitalizations, number of hospitalizations for depression, or number of episodes (total, depressive or manic/hypomanic), differing however on number of hospitalizations for mania, which were significantly higher in BD-P than in BD-NP. The characteristics of pharmacological treatment are displayed in Table 2. A greater number of patients with BD-P (Chi2 = 11.857; df:1; p < 0.001), but no of patients with BD-NP (Chi2 = 2.893; df:1; p < 0.089) received antipsychotic treatment at T2 in relation to T1.

3.1 Neurocognitive function

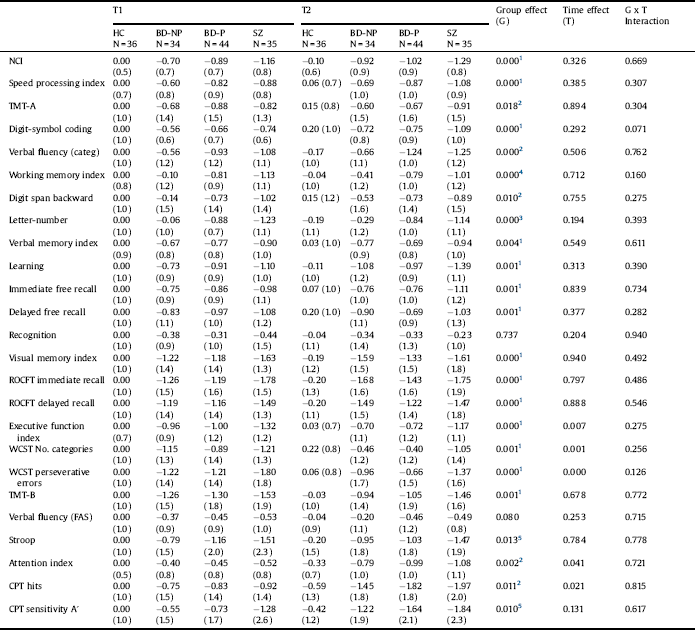

Table 3 shows the z-scores and results of the repeated-measures ANOVA for each neurocognitive measure (See Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1). We found an effect of time on some cognitive measures included in the domains executive function and attention (worse performance both at T2 than at T1 in the domain of attention, and at T1 than at T2 in executive function). However, we did not find a group x time interaction for any cognitive measure.

We found an effect of group for each neurocognitive measure, except for recognition (verbal memory domain) and verbal fluency. The results of the post-hoc tests (Bonferroni test) are shown in Table 4. For the NCI, HC had higher scores than patients. Nevertheless, no significant differences were found between the three groups of patients. Similar results were found for the domains speed processing, verbal memory, visual memory and executive function. For the domains attention and working memory, HC scored higher than BD-P and SZ, but not than BD-NP. Additionally, in the working memory domain, there were significant differences between BD-NP and SZ. We only found differences between BD-P and BD-NP in one measure of the domain working memory (letter and number).

3.2 Psychosocial functioning

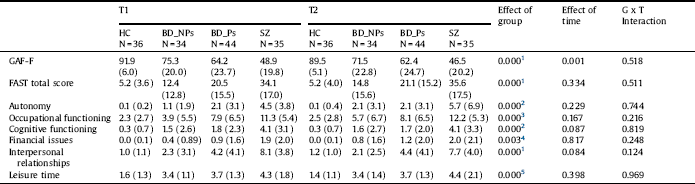

Repeated-measures ANOVA showed group x time interaction for no functional measure (Table 5), although there was an effect of time on the GAF-F (worse performance at T2 than at T1).

We found an effect of group for each functional measure (Table 5). The results of the post-hoc tests are shown in Table 4. There were differences between HC and BD-NP in no functional measure, except for the subscale of the FAST leisure time. However, HC had better performance than BD-P in the two measures of overall functioning and in the subscales occupational functioning, interpersonal relationships and leisure time. Additionally, HC had better performance than SZ in all functional measures.

BD-NP had better performance than BD-P in the two measures of overall functioning and the subscales occupational functioning and interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, BD-NP had better performance than SZ in all functional measures, except for financial issues. BD-P had better performance than SZ in the measures of overall functioning (GAF-F and FAST-total score), and the subscales autonomy, cognitive functioning, and interpersonal relationships (See Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we compared the neurocognitive and functional course of euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, with and without a lifetime history of psychosis, a group of stabilized patients with schizophrenia, and a group of healthy controls, during a five-year follow-up. Three main findings should be highlighted.

Table 2 Pharmacological treatment in patients with bipolar disorder and patients with schizophrenia.

T1: at baseline; T2: at follow-up of five years; BD-NP: Patients with bipolar disorder without history of psychotic symptoms; BD-P: Patients with bipolar disorder with history of psychotic symptoms; SZ: Patients with schizophrenia; SGA: Second-generation antipsychotics; MS: Mood stabilizers; E-CPZ: mg equivalents of Chlorpromazine.

* Comparisons only between BD-P and BD-NP.

1. Chi2.

2. Mann-Whitney U test.

3. Kruskal Wallis Test.

Table 3 Neurocognitive measures (z scores). Repeated measures analysis of variance of patients and healthy controls (Covariates: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale at T1 and T2, Young Mania rating scale at T1).

HC: Healthy controls; BD-NP: Patients with bipolar disorder without history of psychotic symptoms; BD-P: Patients with bipolar disorder with history of psychotic symptoms; SZ: Patients with schizophrenia; TMT: Trail Making Test; ROCFT. Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; CPT: Continuous Performance Test.

1. HC > BD-NP, BD-P, SZ.

2. HC > BD-P, SZ.

3. HC, BD-NP > BD-P, SZ.

4. HC > BD-P, SZ; BD-NP > SZ.

5. HC > SZ.

First, we did not find evidence of progression either in the neurocognitive or in the psychosocial impairment in any of the three groups of patients in relation to HC. The stability found in the neurocognitive impairment is in accordance with the results obtained in most longitudinal studies which have examined the course of neurocognitive function both in patients with BD [Reference Santos, Aparicio, Bagney, Sánchez-Morla, Rodríguez-Jiménez and Mateo31, Reference Burdick, Goldberg, Harrow, Faull and Malhotra54–Reference SNTM, Comijs, Dols, Beekman and Stek56], and patients with SZ [Reference Kurtz57–Reference Hoff, Svetina, Shields, Stewart and DeLisi59]. Likewise, in accordance with our results, other authors could not establish a progressive course of the psychosocial impairment in patients with BD [Reference Martino, Igoa, Scápola, Marengo, Samamé and Strejilevich35], or in patients with SZ [Reference Velthorst, A-KJ, Reichenberg, Perlman, van Os and Bromet60, Reference Jobe and Harrow61]. In this regard, although it cannot be dismissed the possibility of a subset of patients with BD with a progressive course [Reference Sánchez-Morla, López-Villarreal, Jiménez-López, Aparicio, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Roberto39], our results suggest that the presence of a history of psychotic symptoms is not associated with a progression of the neurocognitive or psychosocial impairment.

Second, in line with the results obtained in our cross-sectional study [Reference Jiménez-López, Aparicio, Sánchez-Morla, Rodriguez-Jimenez, Vieta and Santos28], BD-P and BD-NP have a neurocognitive profile of similar characteristics, with only slight differences found between them, circumscribed to the working memory domain. Similarly, other authors did not find relevant neurocognitive differences between these two subsets of patients [Reference Savitz, van der Merwe, Stein, Solms and Ramesar24, Reference Sánchez-Morla, Barabash, Martínez-Vizcaíno, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Balanzá-Martínez and Cabranes-Díaz27, Reference Amann, Gomar, Ortiz-Gil, McKenna, Sans-Sansa and Sarró62–Reference Liu, Chiu, Chang, Hwang, Hwu and Chen64], even in early stages BD [Reference Trisha, Golnoush, Jan-Marie, Torres and Yatham44, Reference Demmo, Lagerberg, Aminoff, Hellvin, Kvitland and Simonsen65], although there exist some discrepant findings [Reference Bora, Yücel and Pantelis18, Reference Krabbendam, Arts, van Os and Aleman66]. In any case, there is broad agreement on the presence of an overlapping in the neurocognitive performance of both groups of patients in a way that the differences found are subtle [Reference Bora, Yücel and Pantelis18]. On the other hand, also a number of studies have found the presence of differences in the working memory domain [Reference Simonsen, Sundet, Vaskinn, Birkenaes, Engh and Faerden12, Reference Bora, Yücel and Pantelis18, Reference Glahn, Bearden, Cakir, Barrett, Najt and Serap Monkul67–Reference Hewedi, Frydecka and Moustafa70], although the effect size is small. Interestingly, in our study, BD-NP did not differ from the control group. In this regard, it has been suggested that working memory deficits found in patients with BD-P could indicate the presence of a possible association between psychosis and frontal lobe dysfunction [Reference Bora, Yücel and Pantelis18].

Table 4 Repeated measures analysis of variance of patients and healthy controls for neurocognitive and functional measures. Significance of test post-hoc (Bonferroni test).

HC: Healthy controls; BD-NP: Patients with bipolar disorder without history of psychotic symptoms; BD-P: Patients with bipolar disorder with history of psychotic symptoms; SZ: Patients with schizophrenia; TMT: Trail Making Test; ROCFT. Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; CPT: Continuous Performance Test; GAF-F: Function dimension of the Global Assessment of Functioning; FAST: Functioning Assessment Short Test.

Table 5 Functional outcome measures. Repeated measures analysis of variance of patients and healthy controls (Covariates: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale at T1 and T2, Young Mania rating scale at T1).

HC: Healthy controls; BD-NP: Patients with bipolar disorder without history of psychotic symptoms; BD-P: Patients with bipolar disorder with history of psychotic symptoms; SZ: Patients with schizophrenia; GAF-F: Function dimension of the Global Assessment of Functioning; FAST: Functioning Assessment Short Test.

1. HC, BD-NP > BD-P > SZ.

2. HC, BD-NP, BD-P > SZ.

3. HC, BD-NP > BD-P, SZ.

4. HC > SZ.

5. HC > BD-NP, BD-P, SZ.

Fig. 1. Course of neurocognitive and functional outcome of patients with bipolar disorder, with (BD-P) and without a history of psychosis (BD-NP), patients with schizophrenia (SZ) and healthy controls (HC): A) z-scores of the neurocognitive composite index (NCI) at baseline (T1) and at follow-up of five years (T2); B) Total score of function dimension of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF-F); C) Total score of the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST).

Third, considering psychosocial functioning, while patients with BD-NP have a level of performance similar to that found in HC, BD-P had a worse performance than HC on most functional measures. Likewise, as has been found in other studies, BD-P showed lower impairment than SZ in overall functioning measures [Reference Lewandowski, Cohen, Keshavan, Sperry and Öngür71, Reference Dickerson, Sommerville, Origoni, Ringel and Parente72]. In addition, BD-P had a worse level of psychosocial functioning than BD-NP, in a way that we could not replicate the findings of our previous cross-sectional study [Reference Jiménez-López, Sánchez-Morla, Aparicio, López-Villarreal, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Rodriguez-Jimenez29]. However, the present results are in accordance with other authors which also reported that patients with BD-P had a worse functional performance than patients with BD-NP [Reference Dell’Osso, Camuri, Cremaschi, Dobrea, Buoli and Ketter20, Reference Levy, Medina and Weiss40–Reference Kempf, Hussain and Potash43]. Therefore, the psychosocial functioning of BD-P would occupy an intermediate position between the functional impairment of patients with BD-NP and that of patients with SZ [Reference Szoke, Meary, Trandafir, Bellivier, Roy and Schurhoff23].

The current study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Most importantly, the small sample size. Another limitation of the study is that all patients were receiving pharmacological treatment. It should be noted that a higher percentage of patients with BD-P were being treated with antipsychotics. Thus, the possibility of a deleterious effect of antipsychotics on the level of neurocognitive and psychosocial functioning cannot be ruled out [Reference Kim, Son, Kim, Lee, Cho and Kim73, Reference Wunderink, Nieboer, Wiersma, Sytema and Nienhuis74]. Finally, a Cronbach alpha coefficient for the working memory domain of 0.585 could alert about the appropriateness of the instruments used for measuring this domain. However, this theoretically low value should be interpreted cautiously, since it is a coefficient which depends on the number of items (only two in our case, WAIS-III digit span backward subtest and letter-number sequencing subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale), and the variation of the population where consistency is evaluated, in such a way that higher values of alpha are expected in homogeneous populations, and our sample included patients with BD, patients with SZ and control individuals [Reference De Vet, Terwee, Mokkink and Dirk75].

Despite the mentioned limitations, we should also note several strengths. First the longitudinal design. Second, the 5-year duration of the follow-up, which could be considered long enough to detect changes. Third, the inclusion of a healthy control group which was also assessed after a five-year follow-up. Fourth, the fact that both patients with BD and patients with SZ were in symptomatic remission at the two time-points of assessment.

In conclusion, our study highlighted that the course of the neurocognitive functioning and the functional outcome in both patients with schizophrenia and patients with bipolar disorder, including those with a history of psychotic symptoms, is stable. Likewise, the profile of neurocognitive impairment of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, with or without psychotic symptoms, is similar, with only quantitative differences circumscribed to certain domains, such as working memory. Importantly, the results suggest the existence of a subgroup of patients with bipolar disorder, characterized by the absence of psychotic symptoms, which does not show a functional deterioration. Nevertheless, these results should be considered preliminary, being necessary longitudinal studies with larger samples and a longer duration to confirm these findings.

Disclosure of interest

Dr. R. Rodriguez-Jimenez has been a consultant for, spoken in activities of, or received grants from: Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid Regional Government (S2010/BMD-2422 AGES; B2017/BMD-3740 AGES CM 2-CM), JanssenCilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Ferrer, Juste, Takeda. Dr. Vieta has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, Allergan, Angelini, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Farmindustria, Ferrer, Forest Research Institute, Gedeon Richter, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, the Brain and Behaviour Foundation, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), the Seventh European Framework Programme (ENBREC), and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the grant PI16/00359 (Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, FIS, and FEDER), by Madrid Regional Government (R&D activities in Biomedicine S2017/BMD-3740 (AGES-CM 2-CM)) and Structural Funds of the European Union, and by the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM) of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.008.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.