INTRODUCTION

In the famous Byzantine epic of Digenis Akrites, a two-blood borderlord defends the empire at the Byzantine–Arab borders by the Euphrates (Hull Reference Hull1972; Elizbarashvili Reference Elizbarashvili2010, 437–60). The name of the hero, Digenis, meaning ‘two-blooded’, refers to the union between his Arab-turned- Christian father and Christian mother, and speaks to the religious and cultural exchange in the borders as well as to borders’ permeability and fluidity (Elizbarashvili Reference Elizbarashvili2010, 443). His name Akrites, defender of borders, points to the political and military realities in Byzantine border zones and the role of local military elites in their protection (Stein Reference Stein2007, 18–19; for the role of the Akritai, Hull Reference Hull1972, xviii–xix). Although Digenis spends more time fighting for love than actually defending the Byzantine borders, this poem ‘preserves and exalts the memory of a frontier society that was vital to the empire's existence’ (Magdalino Reference Magdalino, Beaton and Ricks1993, 438; cf. Elizbarashvili Reference Elizbarashvili2010). In the long eleven centuries of its existence (from the fourth to the fifteenth centuries), Byzantium was constantly engaged in warfare and witnessed dramatic changes in its borders, moving between expansion and territorial loss until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. While the epic of Digenis encapsulates the political and military realities of the Middle Byzantine period (tenth–twelfth century), it highlights also Byzantine policies in border protection and territorial control that continued and were further crystallised in the Late Byzantine period. The management and defence of border regions was often entrusted to members of local elites, such as Digenis, who, having lived and acquired fortunes in those areas, had interests in their protection and well-being. The Digenis epic speaks also to a distinct frontier culture and captures key characteristics of military elite families who played an important role in the political and economic life of the borders (Haldon Reference Haldon1999, 244). It also serves as a commentary on the complex relation of collaboration, tension and competition between borderlords and the central administration which is a key theme in this study (Falkenhausen Reference Falkenhausen and Angold1984, 211–35; Magdalino Reference Magdalino and Angold1984; Magdalino Reference Magdalino, Beaton and Ricks1993, 5–7; Lilie Reference Lilie and Curta2005, 16).

This article explores the identity of borderlords in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and their role in in the political life of the empire, particularly the defence of Byzantine borders. It also considers borderlords’ relationship both to the Byzantine emperors and to the local populations under their control. The case studies presented here include Byzantine and foreign elites, and raise questions about individual borderlords’ ethnic, political and religious identities. How did the borderlords’ different identities inform their strategies for legitimacy and rule? How did they affect the political and socio-economic conditions in border zones? The borderlords’ role in the protection of the empire provides a window onto a better understanding of state mechanisms and changes in the political management of the Late Byzantine Empire. The study of Late Byzantine frontier zones through the lens of borderlords allows us to move beyond simple state-centred approaches to the formation of overlapping political landscapes and reassess state–society relations and the negotiation of power at the edges of the Byzantine Empire. It also reintroduces Byzantine frontiers as zones of overlapping networks of communication and of political and socio-economic relations.

In comparison to previous studies on Late Byzantine military elites and their participation in the defence and administration of the empire, this article places more emphasis on the material evidence. I rely primarily on archaeological and architectural evidence to explore how borderlords chose to represent their authority before different audiences and through different media. The material evidence discussed here provides a direct window onto these borderlords’ decisions, political strategies and the mechanisms they employed to establish their power and increase their influence. An archaeological approach also allows for an in-depth study of the multiple meanings and the reception of the political messages embedded in the borderlords’ actions, building projects and the visual language they employed.

POLITICAL REALITIES IN LATE BYZANTIUM (THIRTEENTH–FIFTEENTH CENTURIES)

The borderlords discussed in this paper, the frontier zones under their control and their relation to central authority are products of the specific political, economic and demographic conditions in the Mediterranean during the Late Byzantine period and the second half of the fourteenth century in particular. The course of the Byzantine Empire changed irreversibly with the Fourth Crusade in 1204 that led to the loss of Constantinople and the majority of Byzantine territories to the Franks and Venetians (Nicol Reference Nicol1993, 1–9; Angold Reference Angold1999; Angold Reference Angold2003). In the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, a series of Latin and Greek succession states gave rise to a politically fragmented Eastern Mediterranean that further contributed to the fragmentation and the decentralisation of the later Byzantine state (Laiou Reference Laiou2005; Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 21–2). When the Byzantines finally regained control of Constantinople in 1261, they found themselves in a new world in which they could no longer set the rules of the game (Laiou Reference Laiou and Shepard2008). Western powers had established themselves in former Byzantine territories and Italian maritime powers, Venice in particular, were in control of the Mediterranean trade. In comparison, the newly re-established Byzantine state had limited resources and exercised limited political control over a small number of territories.

The territorial losses and overall shrinkage of the empire conditioned imperial and elite power in these late centuries. Land meant resources and power for the state; it translated to an income that was used to finance the army and the fleet and as a reward system for military services and for maintaining the loyalty of the elites (Frankopan Reference Frankopan and Haldon2009, 113). Loss of lands and inability to defend its territories and maintain a serious army and fleet weakened the state, threatened its safety and created dissatisfaction and distrust among the local population and army (Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 19–20; Haldon Reference Haldon and Haldon2009, 203).

Within this framework of political turmoil and territorial loss, the Byzantine civil wars in the fourteenth century between members of the ruling family of Palaiologoi and their court were a turning point (Stathakopoulos Reference Stathakopoulos2009, 93). The wars devastated the empire and exhausted its finances, which led to the weakening of central authority and its control over military resources (Frankopan Reference Frankopan and Haldon2009, 120). They also led to alliances with foreign powers, such as the Serbians and Turks, and their infiltration into Byzantine territories with catastrophic results: for example, the first Ottoman foothold in Europe (Gallipoli) in 1354 was a result of such alliances (Nicol Reference Nicol1993, 152–66, 185–208; Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 20–1; Chrissis and Carr Reference Chrissis, Carr, Chrissis and Carr2014, 11). In the aftermath of the civil wars, Byzantine emperors were forced to depend upon military and financial support from the West and in the meantime to try to appease the Ottomans (Nicol Reference Nicol1993; Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 18–38; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 37). Finally, many elite families that were engaged in the civil wars found their fortunes exhausted, their lands lost to enemies or confiscated and the foundation of their power destroyed. These conditions gave rise to new elites who could master the flux of these years both financially and politically. Many of them had little in common with the traditional elite families with long lines of titles, connections and political career in the court; Angold (Reference Angold and Angold1984a, 6) characterised them as ‘adventurers’. It is just such adventurers who are the protagonists of the second half of the fourteenth century and of this study.

The civil wars of this era fuelled the political conflict among elites and contributed to the political fragmentation within the empire. For example, in an effort to balance and satisfy the ambitions of members of the Palaiologoi and Kantakouzenoi, John VI Kantakouzenos divided the empire and allocated large territories to each prince to rule independently in Macedonia, Thrace and the Morea (Stathakopoulos Reference Stathakopoulos2009, 96; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 35–6; Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 251–2). Similarly, Thessaloniki was ruled as a semi-independent city by members of the imperial family and enjoyed significant autonomy (Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 45–7). Centrifugal tendencies were not new in Byzantine politics: they are well attested at the end of the Middle Byzantine period and especially during the late twelfth century, when separatist movements increased and provinces started relying more upon local and regional elites (Angold Reference Angold and Angold1984b, 243; Savvides Reference Savvides1987, 121; Haldon Reference Haldon1999, 238; Anagnostakis Reference Anagnostakis and Simpson2015, 136). Financial stress and the inability of the state to protect the local population and secure their interests fuelled local dissatisfaction and turned the provinces against Constantinople and towards local magnates who were ready to protect them and their interests even against the central administration (Angold Reference Angold and Angold1984b, 242; Savvides Reference Savvides1987, 124–5; Anagnostakis Reference Anagnostakis and Simpson2015, 147–8). The power of such elites and their influence in the provinces remained strong even after 1204 and was acknowledged by the Latins. In the case of Adrianopolis, for example, the Venetians left the governance of the city in the hands of the local elites on the condition that they provided military service when needed (Angold Reference Angold and Angold1984b, 244). Such centrifugal phenomena, which promoted localism and allowed elites to rule regions quasi-independently, further crystallised in the Late Byzantine period and conditioned the relationship between elites, provinces and the state. By the second half of the fourteenth century the empire had split up into a series of apanages for the members of the ruling houses, each with its own small court and princes, creating a constellation of hubs of political activity scattered in the Eastern Mediterranean. Under these conditions it is difficult to talk about an empire in the traditional sense, since there is a lack of political, administrative and even territorial cohesiveness (Kiousopoulou Reference Kiousopoulou2011, 6–7; Angold Reference Angold and Angold1984a, 6; Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 18–19). These multiple centres of power often became a barrier to a uniform foreign policy and prompted different and less centralised solutions to the empire's administration and defence (Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 22).

LATE BYZANTINE BORDERS AND THEIR DEFENDERS

The study of borders, frontiers and borderlands has been a developing field among historians, social and political scientists, archaeologists and geographers. Notions of borders as linear, fixed and permanent entities go back to Turner's work on the American West frontier which has long been criticised for its inapplicability to other political conditions and environments and failure to recognise the permeability and fluidity of borders (Turner Reference Turner1963; for a critical approach to Turner's work, see Slotkin Reference Slotkin1992; Kutchen Reference Kutchen2005; Naum Reference Naum2010, 102–3). In the case of ancient and medieval states, linear and clearly defined border lines emerge in texts as part of the construction of political propaganda and imperial ideology but have little to do with the reality on the ground (Berend Reference Berend1999; Pohl Reference Pohl and Curta2005, 265; Smith, M.L. Reference Smith2005; Kulikowski Reference Kulikowski and Curta2005, 247, 252–3; Parker Reference Parker2006, 80). Furthermore, as Stephenson (Reference Stephenson, Power and Standen1999, 81, 97) notes, in Byzantine textual sources frontiers were understood as entire regions as well as political boundaries, further challenging the notion of linear borders. The capacity of ancient and medieval states to control their borders has also been overstated; according to Byzantine historical accounts, borders were often breached despite garrisons and fortifications, even in the case of massive barriers, such as the Anastasian wall in Constantinople's hinterland (Smith, M.L. Reference Smith2005; Crow Reference Crow, Sarantis and Christie2013). Byzantine borders were associated with landmarks, such as cities and castles, rather than linear, steady and highly recognisable markers. Border control was achieved by controlling important landmarks and main routes, while open areas around these landmarks continued to be contested (Kaegi Reference Kaegi, Mathisen and Sivan1996; Pohl Reference Pohl and Curta2005, 260–1; for similar phenomena in the Ottoman period see Stein Reference Stein2007, 14–15). Such definitions of borders emphasise the permeable and unstable nature of Byzantine borders and place great emphasis on the control of fortifications and fortified cities. In fact, in the fourteenth century castle sieges outnumbered all other types of military conflict, suggesting that the protection of defended sites was synonymous with the protection of the borders, especially at a time when the state had neither the resources nor the army to control large frontier areas (Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 157–63, 184; for the role of fortifications in the borders see also Haldon Reference Haldon1999, 249).

The protection of the Byzantine Empire and its borders, the organisation and financial support of the army and the decisions on war were the emperor's prerogative (Cheynet Reference Cheynet and Cheynet2006, 37; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 15). Even in Late Byzantium, despite the lack of resources and the key role of elites in the defence of the empire, emperors never lost their interest and primary role in war and the empire's protection. Late Byzantine emperors continued to allocate substantial revenues towards the defence of the empire's borders, involving repairs of existing fortifications and the strengthening of the defence network by new forts, as exemplified by the building projects of Michael VIII in Asia Minor in the late thirteenth century and Andronikos III in Thrace and Macedonia in the first half of the fourteenth century (Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 158). The empire's diminishing lands had, however, direct and serious consequences for the state and deprived it of the means to maintain an army and a fleet. They thus forced Late Byzantine emperors to ‘outsource’ the defence of the empire's borders to third parties, elite and non-elite, who had the resources and the armed and naval forces to protect Byzantine territories, and rely more heavily on the Italian maritime powers for help.

One of Byzantium's main policies was to grant public and imperial lands to individuals as a reward and in exchange for their services, especially military support. In this section I discuss how such policies informed the defence of the Late Byzantine borders, and I examine the three military groups who were recipients of such grants and directly involved in border protection: simple soldiers, Byzantine military officials, and foreigners with armies and fleets available for hire.

The institution of pronoia was the main way of financing the army from the eleventh century onwards and included the allocation of imperial lands to soldiers to settle and exploit in return for their military service (Kazhdan and Wharton Reference Kazhdan and Wharton1985, 60–1; Cheynet Reference Cheynet1990, 237–47; Cheynet Reference Cheynet and Cheynet2006, 29; Bartusis Reference Bartusis2013). Pronoia translated into wealth, power and prestige (Haldon Reference Haldon and Haldon2009, 170, 195; Frankopan Reference Frankopan and Haldon2009, 113). It provided individuals and groups with access to lands and consequently with an income, accompanied by significant tax exemptions, including property tax, which increased their wealth and influence. Pronoia was also the direct marker of a special relationship between the holder and the emperor, and it thus bore social significance and power that came with proximity to the emperor (Cheynet Reference Cheynet and Cheynet2006, 28–9; Frankopan Reference Frankopan and Haldon2009, 126). The importance of pronoia for a functioning army and for the defence of the empire more broadly can clearly be seen in the situation of late thirteenth-century Asia Minor as described by the Byzantine historian Pachymeres. He mentions that the soldiers of Asia Minor could not fully prepare for war and arm themselves because they had lost the properties they had held through pronoia (Pachymeres 4.285; for this incident see also Bartusis Reference Bartusis1992, 75; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 78–9). The constant advances of the Turcomen in Asia Minor and the loss of territories, and therefore of pronoia, led to the dissatisfaction of soldiers and local elites in the borders, who felt that the state was able no longer protect their interests, leading many to join the enemy (Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 27).

Grants and privileges, particularly donations of lands in exchange for services instead of cash salaries, were also witnessed in the upper tiers of military command and government of the peripheries (Bartusis Reference Bartusis2013, 599). As Neville has argued, Byzantine governors and generals in frontier zones were encouraged to live off these territories received from the emperor, being allowed to harvest and keep for themselves the revenues instead of sending the collected taxes back to the imperial treasury, pointing to a strong link between land and defence (Neville Reference Neville2004, 24; see also Kazhdan and Wharton Reference Kazhdan and Wharton1985, 60–2; for similar policies in the management of the Ottoman borders see Stein Reference Stein2007, 133). Land grants and tax exemptions in lieu of a salary had become prominent at the end of the eleventh century and continued throughout the Late Byzantine centuries. They gave rise to a landed aristocracy which maintained substantial properties in the province supported by these grants, and allowed them to increase their wealth, power and influence (Haldon Reference Haldon and Haldon2009, 170).

Byzantine emperors were especially interested to use these grants to harness the power of elite families located in frontier zones. As is evident in the Digenis poem, the imperial administration was looking for such elites to organise the political and military life of the borders and create buffer zones between Byzantine core areas and its enemies in both an official and unofficial capacity (Magdalino Reference Magdalino, Beaton and Ricks1993, 8).

A fundamental difference between the Middle and Late Byzantine periods is that it is difficult to speak about private armies and initiatives in military affairs before the thirteenth century. In the Middle Byzantine period, and especially in the Komnenian dynasty, the military achievements and prowess of Byzantine emperors were exalted. This is a period that witnessed the rise of military elites in the borders and produced a line of emperors who came from such families. Men such as the emperor Manuel I Komnenos (1143–80) relied on his family military pedigree and modelled himself upon military heroes of the frontiers, such as Digenis, to push his aggressive military policies and gain popular support for his constant campaigns in the East (Jeffreys Reference Jeffreys1980, 484; Kazhdan and Wharton Reference Kazhdan and Wharton1985, 115). The only exception is a short period at the end of the eleventh century when, owing to repeated invasions of the eastern borders and financial shortage, the Byzantine emperors turned to wealthy individuals and entrusted them with the restorations and building of castles (Cheynet Reference Cheynet and Cheynet2006, 36). In the Late Byzantine period members of the high elite, such as John Kantakouzenos and Alexios Apokaukos, built fortifications, paid towards the salaries of the army and contributed financially to the rebuilding of an imperial fleet (Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 33–4). Kantakouzenos’ testimony of elite participation in the defence of the empire is telling, although we must take into account that such declarations in his history aim at legitimising his own actions. Still, he wrote that he never objected to elite contributions to the causes of defence and the army and he declared that he did not want to be outdone by anyone in the financial support he offered for the empire's protection (Cantacuzenus 1.185: see Schopenus Reference Schopenus1828–32). It is important to note that while these aristocrats participated more actively and financially in matters of war and defence, they did so with imperial permission and in the hope that their financial support of military affairs would enhance their influence over the Byzantine emperor (see also Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 161).

Mercenaries and foreigners were also in the service of Byzantine emperors, actively participating in the defence of the empire and holding key positions in its military and political life. Early in Michael VIII's reign, the Aegean was ruled by several Latin lords and was also plagued by piracy, making the reconquest of the Aegean both a priority and a challenge, considering the lack of a fleet and the means and time to build it. The career of Licario, a Lombard adventurer, exemplifies imperial policies under Michael VIII that allowed foreigners to play a critical role in the defence of the empire. Michael recruited Licario for his knowledge, naval skill and fleet. He made Licario responsible for commanding the mercenaries and leading major naval operations aimed at re-establishing Byzantine control in the Aegean and, more importantly, bringing Negroponte under Byzantine control. In return for his services, Michael bestowed high official titles and honours and even gave him Negroponte as his fief in return for his services (Angold Reference Angold, Saint-Guillain and Stathakopoulos2012, 35–7). Pachymeres saw this series of unprecedented events as a ‘necessity’; at a time of limited resources and no fleet, Michael harnessed the available talents of pirates, mercenaries and adventurers to create his own navy and establish Byzantine control over islands and coastal areas that were crucial for the survival of the recently re-established empire (Pachymeres 4.597: see Failler 1999). By bestowing lands and titles he also connected men like Licario to his person and ensured their loyalty. His grant of Phokaia to the Genoese brothers Manuel and Benedetto Zaccaria should be understood under the same premises (Miller Reference Miller1911; Angold Reference Angold, Saint-Guillain and Stathakopoulos2012, 36; Carr Reference Carr, Chrissis and Carr2014). Michael's practices were born of necessity and lack of resources as well as his need to establish his own authority and legitimacy. In doing so, he paved the way for later Byzantine emperors who found themselves in a similar position.

By the time Emperor John V came to the throne as sole emperor in 1354 there was no money in the imperial treasury; and with the Ottomans gaining a European stronghold and developing a stronger fleet, the need for territorial control and defence became ever more pressing (Necipoğlu Reference Necipoğlu2009, 25; 43; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 36). Under these circumstances, John V and the emperors who followed had to turn to individuals within and outside the traditional elite groups who had the means, in terms of resources and fleets, to create a buffer zone of security around the remaining Byzantine lands. That included elites and non-elites, Byzantines and foreigners, and even religious institutions, such as the Athonite monasteries, which became more involved in defence projects after the civil wars (Kondyli Reference Kondyli2010; Reference Kondyli and Chrysochoidis2016). The overlapping and often conflicting motivations and agendas of these groups meant that borders were contested areas of power not only across political boundaries but also between different political and social groups within a frontier zone (Wilson and Donnan Reference Wilson and Donnan1998, 5–6; Baud and Schendel Reference Baud and Schendel1997, 219; Zartman Reference Zartman and Zartman2010, 4–6).

THE PROFILE OF A LATE BYZANTINE BORDERLORD

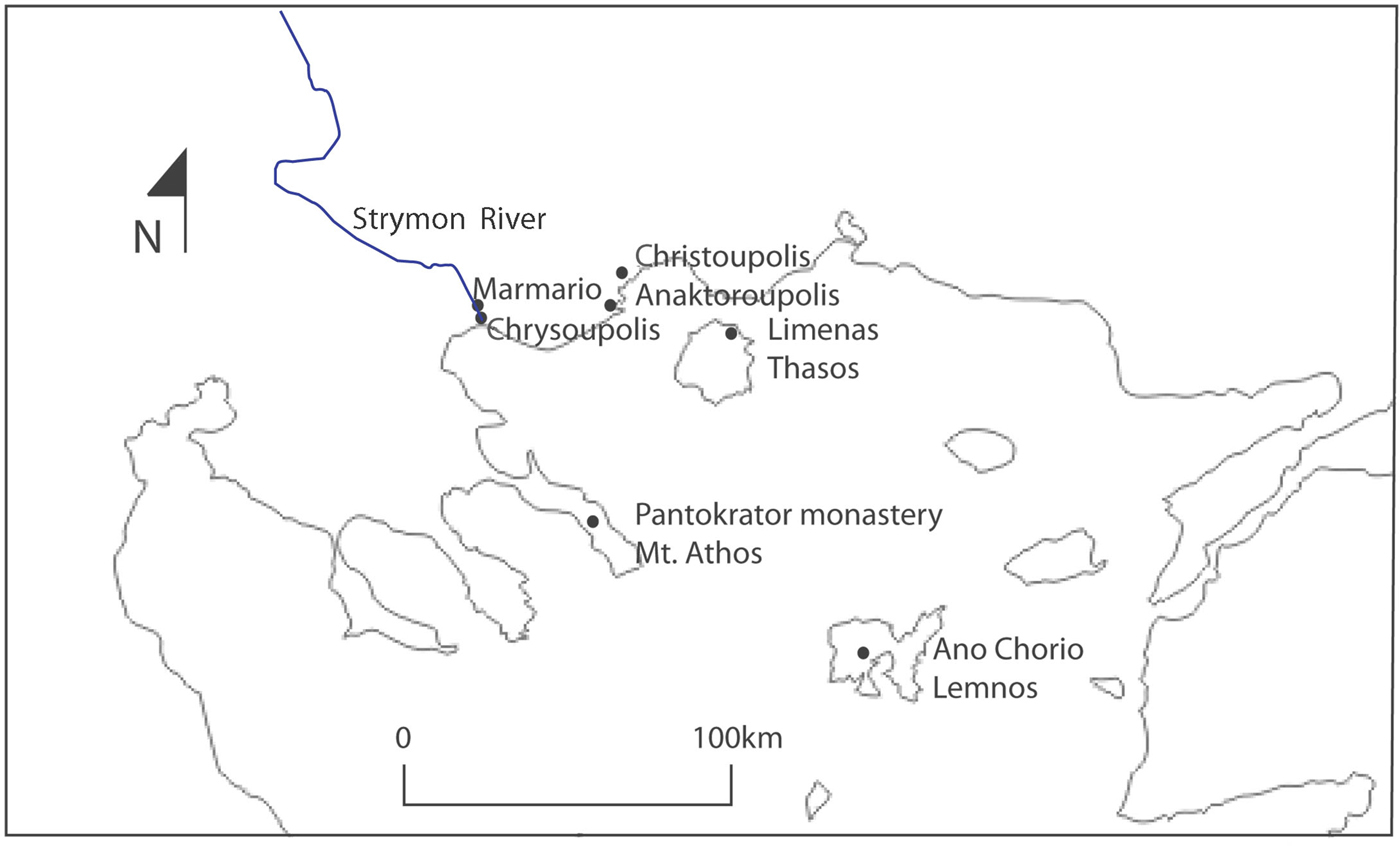

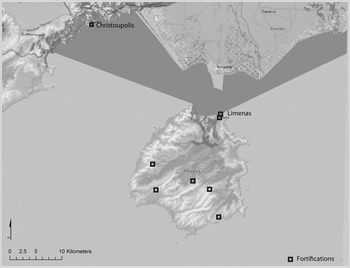

Late Byzantine borderlords were agents of power and key contributors to political landscapes shaped by their political aspirations and strategies. I present here two case studies of borderlords in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, focusing on the brothers Alexios and John, who became lords of several areas in coastal Macedonia and the Northern Aegean at a time when they were surrounded by enemies and operated as frontier zones (Fig. 1). I also briefly introduce the case of the Gattilusi, a Genoese family who also became rulers of Byzantine regions in the Northern Aegean and Thrace in the same period. Alexios and John were Byzantine officials with previous ties to the communities they were given to rule, whereas the Gattilusi were Genoese and of Latin faith, ruling territories with a dominant Greek-speaking and Orthodox population.

Fig. 1. Area of study, North Aegean, Greece (map by author).

Both these families fit with Angold's description of ‘adventurers’, individuals who seized the opportunity in the aftermath of the civil wars and underwent transformation from ‘leaders of war bands’ to lords of independent territories and relatives of the Byzantine emperor (Angold Reference Angold and Angold1984a, 6). They both received these lands with privileges and the right to rule them in the second half of the fourteenth century, mainly owing to their military services and loyalty to John V Palaiologos. They were also connected to the Byzantine emperor through marrying into the Byzantine imperial family. In what follows I compare and contrast their political strategies, building programmes and visual language in their monuments to better understand how political landscapes were formed in the Late Byzantine frontier zones. I pay particular attention to the changes and manipulation of the natural and built environment as the borderlords’ mechanisms to negotiate their authority and embody their aspirations of power and legitimacy (Smith, A. Reference Smith2003, 75–7). While I discuss different parts of the Northern Aegean, where the protagonists of this article operated, I pay particular attention to the island of Thasos and its fortifications. The port at Limenas in Thasos has been the subject of extensive archaeological investigation, including its architecture, spatial layout and pottery finds. Coupled with a detailed description of the area named in John's will, the archaeological evidence offers a clear idea of Limenas’ transformation in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Thasos remains at the heart of this discussion also because it was controlled by both the borderlord groups discussed here in consecutive periods, allowing further comparisons between different borderlords’ strategies in the same region.

Following Bourdieu's (Reference Bourdieu, Dirks, Eley and Ortner1994, 164) idea that symbolic power can be obtained and lost and therefore stands in proportion to the recognition an agent receives from the group, I investigate ways in which these agents of power both sought and received that recognition. In taking this approach, I recognise also the other half of the political equation: the role of the ruled in promoting and challenging their rulers' authority. That is to say, in a border zone setting, local populations could support local rulers or challenge their authority through mobility and cooperation across enemy lines; consequently they had an impact upon the borderlords’ strategies (Smith, A. Reference Smith2003, 155–6, 228–30; Zartman Reference Zartman and Zartman2010, 6, 9). I assess also the borderlords’ cross-border networks and their relation to other political and economic groups to show how they embedded their regions in wider political and socio-economic networks, thus creating new geographies and new ties among different regions in the medieval Mediterranean. The comparative study of these two cases highlights issues of agency, authority and strategy variability in the Late Byzantine Aegean. It also underscores the impact of borderlords on the political and socio-economic realities of Late Byzantium and their role within imperial strategies of border control and sovereignty in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

On His Majesty's Service: The case of Alexios and John

Alexios and John were high-ranking military officials in the service of Emperor John V Palaiologos in the second half of the fourteenth century (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 7–11; Oikonomides Reference Oikonomides, Bryer and Cunningham1996; Wright Reference Wright2014, 89–91). The two brothers had supported Palaiologos’ claim to the throne and had proved instrumental in the defence of Macedonia, pushing back the Serbian army from the coastline. John V, in return, rewarded them with large territories from the newly freed lands in the Northern Aegean after his elevation to the throne and offered John his niece in marriage. However, it is important to also recognise that before receiving these honours and rights, John and Alexios had been conquering Byzantine territories with their own armies, acting independently from any imperial power. John V decided to confirm their conquests and raised them in their rank instead of going against them or demanding the territories back (Angold Reference Angold and Angold1984a, 6). According to the archives of the Pantokrator monastery at Mount Athos which was founded by Alexios and John, they ruled, free of any financial or other obligation, the towns of Christoupolis, Chrysoupolis, Anaktoroupolis and Limenas on the island of Thasos and also owned extensive areas along the Strymon river and on the island of Lemnos (Fig. 2) (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 7–11; Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 68).

Fig. 2. Map of areas ruled by Alexios and John in the second half of the fourteenth century (map by author).

The areas under Alexios and John's control had been severely affected by the civil wars and piratical raids. The Black Death in the mid-fourteenth century had added to the areas’ devastation, amplifying problems of depopulation and decreased production. Alexios and John's main priority was to create a defensive network in coastal Macedonia that would protect the local populations from future attacks and enhance surveillance and control of the sea routes that connected Thessaloniki and Constantinople. In what follows I briefly present a series of fortifications in coastal Macedonia and Thasos associated with Alexios and John's rule. For the purpose of this article I am interested in looking at these building as a way of negotiating authority and creating new political landscapes rather than discussing in depth their architectural history. Some of these castles are the result of consecutive building phases throughout the Byzantine and later periods, including expansions, additions and restorations; it can therefore be difficult to assign a rebuilding phase to the time of Alexios and John. However, it is important to note that these fortifications came under their rule, were restored and manned and participated in a new network of defence and communication created by the two borderlords.

The castle of Anaktoroupolis played an important role in the political and military events of the mid-fourteenth century. Andronikos III (1328–41) had appreciated its strategic importance and had included it in a series of castles in Macedonia that were repaired during his rule (Karagianni, Reference Karagianni2010, 88–9). The coastal fortress of Anaktoroupolis functioned as Alexios and John's military base long before John V recognised their right to rule over that area. From there they fought against the Byzantine Emperor Kantakouzenos during the second civil war and even launched military attacks in nearby areas under Serbian control (Tsouris Reference Tsouris, Kavvadia and Damulos2012, 563; Wright Reference Wright2014, 89–90). The castle is an irregular rectangle built on a small peninsula with a circuit wall enclosing an area of 1.5 ha, strengthened by circular, polygon and square towers (Fig. 3) (Kakouris Reference Kakouris1980, 250; Dadaki et al. Reference Dadaki, Doukata, Eliadis, Lychounas and Karagianni2013, 213). It was divided into two defensive zones by an interior wall, while a lower proteichisma on the east side offered one additional line of defence. The main entrance was on the west side, flanked by square towers, while in the north-west corner remains of lower walls across the coastline could be part of a jetty (Kakouris Reference Kakouris1980, 250). The exact date of the castle's initial construction remains unknown, but literary sources point to the existence of a fortification from as early as the eleventh century (Karagianni Reference Karagianni2010, 88, 143). An inscription discovered on the south circuit wall, together with pottery found in the debris of fallen upper walls and a contemporary coin from a nearby grave, supports a late twelfth-century date for the construction or reconstruction phase (Kakouris Reference Kakouris1980, 253–5; Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 82). It is tempting to think that some of the later repairs visible on the walls and the alterations to the towers could be associated with Alexios and John, but only a complete architectural study and extensive excavation could answer this. In any case, Alexios and John recognised and exploited the key geographical position of the castle in controlling the North Aegean Sea routes.

Fig. 3. Plans of the main fortifications controlled by Alexios and John at Anaktoroupolis (drawing by the author based on plan in Kakouris Reference Kakouris1980, pl. 1).

The castle of Christoupolis, modern Kavala, has a long architectural history, with the first defence wall dating back to antiquity, probably to the fifth century bc (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 68). Expansions, modifications and repairs are known from the time of Justinian and again in the early tenth and late twelfth century, based on a series of inscriptions (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 68; Dadaki et al. Reference Dadaki, Doukata, Eliadis, Lychounas and Karagianni2013, 214). The fortifications and part of the city were destroyed at the end of the fourteenth century, so the standing remains of the acropolis date from the first half of the fifteenth century, with later additions and alterations (Fig. 4) (Mallouchou and Tufano Reference Mallouchou and Tufano1980, 344–5; Karagianni Reference Karagianni2010, 138–40). However, Byzantine features were embedded and included in the later fortifications. The central circular tower that dominates the acropolis and the nearby cistern, as well as the remains of two square towers in the outer wall could possibly be parts of the Byzantine fort (Mallouchou and Tufano Reference Mallouchou and Tufano1980, 344–5). The strategic location of the castle as a connecting node between Constantinople and Thessaloniki attracted Alexios and John's interest, and they incorporated it in their coastal fortification network, probably also repairing any damage it suffered during the second civil war.

Fig. 4. Christoupolis (drawing by the author based on plan in Karagianni Reference Karagianni2010, 139).

The area of Limenas and its port at Thasos were also granted to Alexios and John by Emperor John V. John, the military official, in his will emphasises the island's initial ruinous state due to piratical attacks, and refers to his successful efforts to bring order and prosperity to the island (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 99–100). The areas at the Limenas port excavated by the French School at Athens and the standing structures of the acropolis together reveal a strong double set of fortifications (a fortified port-acropolis) and attest to John's efforts to transform Limenas into a new economic and administrative focal point. The French excavations exposed parts of the port's defensive wall, the foundation of a tower and an adjacent well inside the fortified area matching the description of the fortifications in John's will (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 100, no. 10 [1384]; Giros Reference Giros and Kravari1991, 47; Mulliez, Muller and Blondé. Reference Mulliez, Muller and Blondé2000, 512). The port fortress was very original in its design, divided into at least two parts, separated by a wall and a moat, making fortifications in the shape of small islands (Fig. 5) (Spieser Reference Spieser1973, 542). The Late Byzantine defensive walls followed the course of the ancient Greek wall at several points and even incorporated ancient defensive architectural elements into the medieval structures, affecting the spatial organisation of the fortifications (Giros Reference Giros and Kravari1991, 45–50; Grandjean and Salviat Reference Grandjean and Salviat2000, 59; Mulliez, Muller and Blondé Reference Mulliez, Muller and Blondé2000, 514). Of the two towers found inside the defended area, the tower located at the western part of the fortress (T1 in Fig. 5) was still standing in 1931, when it was demolished for the building of the new museum (Holtzmann Reference Holtzmann1979, 635–6; Grandjean and Salviat Reference Grandjean and Salviat2000, 35). It was of rectangular plan (14 m × 10.6 m) with a small projection on the north side where also the entrance to the tower was located (Giros Reference Giros and Kravari1991, 46). It was built from large blocks of spolia from the nearby ancient agora and from early Christian monuments, mortar and stones matching the appearance of the circuit wall (Giros Reference Giros and Kravari1991, 46). On the east part of the fortified port, the excavators revealed a bridge deck attached to another tower (T2 in Fig. 5) that allowed communication between the west and the east parts (Mulliez, Muller and Blondé Reference Mulliez, Muller and Blondé2000, 513). North-west of the port, built upon the ancient acropolis, there is another fort overseeing the port and its fortifications, probably what John referred to in his will as ‘Epano Kastro’ (Upper Castle) (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 100, no 10 [1384]). This acropolis, mentioned already at the beginning of the fourteenth century, might have been restored during the Latin conquest, and then again by John and Alexios before it was rebuilt and strengthened by the Gattilusi in the fifteenth century (Lazaridis Reference Lazaridis1958, 31; Giros Reference Giros and Kravari1991, 45; Koder Reference Koder1998, 222; Grandjean and Salviat Reference Grandjean and Salviat2000, 35; Giros and Dadaki Reference Giros, Dadaki and Martin2001, 519).

Fig. 5. Limenas, Thasos (drawing by the author based on plan in Grandjean and Salviat Reference Grandjean and Salviat2000, 513).

A viewshed analysis (which can calculate and visualise all visible areas from an observation point, taking into consideration the topography, terrain and elevation of the observation point) was applied to Limenas’ new fortifications to better understand their role in a local and regional defence network and thus appreciate the efforts of Alexios and John in the area. The massive mountainous centre of the island prohibits visual communication between the island's fortifications, limiting the extent of their visual control in nearby areas. In the distribution map of Late Byzantine fortifications in the island, the shaded areas indicate the extent of each fortification's visual control (Fig. 6). It becomes clear that, with the exception of Limenas, all other fortifications are located towards the interior of the island, in naturally protected locations mainly at the centre and south part of the island, and have very limited visibility and visual communication with each other. Hence, at a local level Limenas addresses the lack of protection in the north part of the island, particularly in the flat and arable plain to its east, and provides a spacious and well-protected harbour. At the supraregional level, however, Limenas participates in a wider network of defence across the sea, involving also the coasts of Macedonia. The viewshed analysis supports the possibility that Limenas had visual contact with Christoupolis, which was also under Alexios and John's control and could easily communicate with the fortifications on the opposite coast (Fig. 7). The viewshed analysis further supports the idea that the three forts of Christoupolis, Anaktoroupolis and Limenas created a triangle of communication and control operating between the mainland (coastal Macedonia) and the island (Thasos). At a local level, each castle protected the nearby resources and the local population but, at a supraregional level, they participated in a wider network of surveillance and protection of coastal Macedonia and the northern sea routes towards Constantinople.

Fig. 6. Distribution map of Thasos’ fortifications. Areas visible from each fortification are marked by a darker tone based on a GIS viewshed analysis (map by author).

Fig. 7. Visual communication between Limenas and Christoupolis based on GIS viewshed analysis (map by author).

Besides those coastal fortifications, Alexios and John also controlled areas along the Strymon river delta, including the fortified town of Chrysoupolis and the tower at Amphipolis and its surrounding area. The River Strymon provided the southern Balkans and inland Macedonia with access to the Aegean and was thus a natural focal point of communications, exchange and redistribution (Dunn Reference Dunn and André1999, 399). Owing to its strategic location, Chrysoupolis attracted the interest of the Palaiologan emperors and became an important administrative and economic centre in the Late Byzantine period. Specifically, during the reign of Andronikos III, the fortifications of the town were strengthened and expanded to the east to include an area of 9 ha (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 86; Dunn Reference Dunn and André1999, 407; Karagianni Reference Karagianni2010, 141). The fort is made from two circuit walls extending east and west with a small acropolis in the middle, strengthened by square towers in the east and south side of the walls and probably by a moat on the west (Fig. 8) (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 86; Dunn Reference Dunn and André1999, 408, fig. 4). It is unknown whether Alexios and John repaired the castle when it came under their control, but it was essential for their political and economic vision that the castle remained functional and able to provide protection to the area; the latter had been prey to enemy and pirate attacks for so long that, despite its advantageous location, it would remain uninhabited unless Alexios and John could provide sufficient protection and convince the local population not to abandon it. Furthermore, the two brothers owned vast lands in and around Chrysoupolis, as well as fisheries and mills in the north-western part of the delta, another incentive to invest in the protection of the area (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 7–11, 91–4, no. 9 [1374]; Dunn Reference Dunn and André1999, 407, 412).

Fig. 8. Chrysoupolis (drawing by the author based on plan in Dunn Reference Dunn and André1999, fig. 4, 408).

The ancient town of Amphipolis, located north-west from Chrysoupolis by the Strymon river, was uninhabited in the Late Byzantine period, but the general area maintained its economic importance (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 86). Numerous Athonite monasteries as well as other big landowners maintained economic bases and estates in that area and even erected their own towers (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 89–91; Dunn Reference Dunn and André1999, 411–12). Alexios and John built a tower in the location of Marmario in the north-west part of the Strymon delta by the north riverbank to better control the north part of the river, to facilitate tax collection and storing of goods, and to provide a visible marker of their presence in the area (Fig. 9) (Dunn Reference Dunn and André1999, 411). Its proximity to the fortification of Chrysoupolis allowed the two areas to work together in controlling movement of people and commodities in the Strymon river and its access to the North Aegean Sea.

Fig. 9. Alexios and John's tower at Marmario (reprinted with the permission of both D. Eugenidou and the photographer [V. Voutsas] from Eugenidou, Reference Eugenidou1997, 91).

The tower at Marmario and the fortified town of Chrysoupolis controlled a north–south corridor that leads to the North Aegean Sea, whereas the three castles of Limenas, Anaktoroupolis and Christoupolis controlled a west–east corridor in the Northern Aegean. These two sets of fortifications could very well communicate with each other, since the distance from Chrysoupolis to Anaktoroupolis can be covered in a day's journey. Moreover, free-standing towers dotted across the Macedonian coastline could become an additional link between the two sets of fortifications, allowing further communication. The Late Byzantine tower of Apollonia, for example, located between Chrysoupolis and Anaktoroupolis, could have functioned in such a way, although Nikos Zekos has recently proposed that the tower was privately owned (Zekos Reference Zekos and Karadedos2006, 57–67); even in that case, the possibility of collaboration and exchange of information among coastal fortifications in time of danger is still possible (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 85). The tower stands in the middle of a rectangular wall enclosure, and had three storeys (with built interior staircase still visible today) and an entrance on its north side standing much higher than the ground for extra security (Karagianni Reference Karagianni2010, 130). Its elevated position and proximity to the sea allows great command of the Northern Aegean; thus the tower could potentially participate in the surveillance of the Macedonian coastline.

This defensive network speaks volumes about Alexios and John's building activities and political strategies. The two brothers concentrated their efforts in rebuilding and strengthening the fortifications in coastal Macedonia and along the River Strymon. In doing so, they introduced a new geopolitical order, shaped by new focal points and by new connections among regions that were now united under the two lords’ control. Together with their small fleet, Alexios and John's fortifications could sufficiently protect local populations in these areas, provide safe access and control of important sea and river trade routes and offer political and economic stability in the Northern Aegean. The protection of ports, trade routes and markets points to their preoccupation with stimulating trade and other economic activities. The fourteenth-century pottery found in the excavation of Limenas imported from Macedonia, Lemnos and the capital underscores the economic interaction among these areas and points to the role of Thasos in sea commerce due to its new safe harbour (François Reference François1995, 125–30).

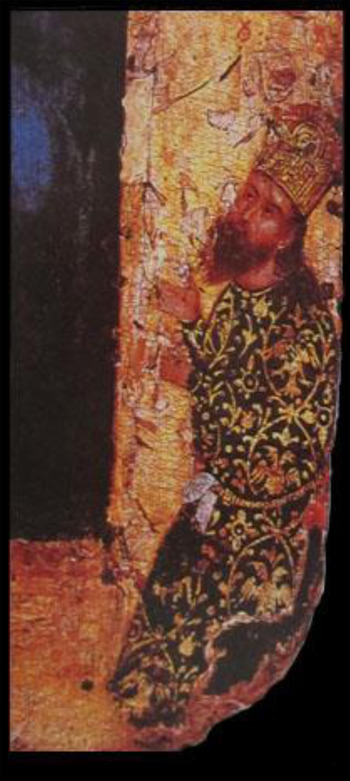

With their building programme, Alexios and John were addressing people in all social tiers, both friends and foes, trying to negotiate their permanent presence in the borders, emphasising their invested interests in coastal Macedonia and reminding everyone of the resources they were allocating for its protection. Through their building programme the two brothers presented themselves as powerful lords who could protect those territories and provide them with stability and prosperity. Their foundation of the Pantokrator monastery at Mount Athos enhanced their image as generous, wealthy and pious lords and promoted their privileged relation with God. Indicative of the way they presented themselves is the fourteenth-century icon of Pantokrator that Alexios and John donated to their monastery, now at the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Figs 10–11). Although the two brothers are portrayed as tiny figures kneeling in a gesture of deesis (prayer) at the borders of the icon (only John's portrait survives), everything about the composition speaks of their wealth, rank and social status. Both their names and titles mentioned in red letters on top of each figure and John's luxurious garments allude to their class and wealth (Fig. 11). John is wearing a green caftan-like garment made of expensive material embroidered with golden thread, typical of Late Byzantine officials and aristocrats (Parani Reference Parani2003, 58–61). It is adorned with double-headed eagles enclosed in medallions, a symbol of authority, also used by the ruling family of the Palaiologoi and their relatives (Parani Reference Parani2003, 58–9, 62, 335, Appendix 3, nos 43, 66, pl. 72; for the symbolism of the double-headed eagle, Androudis Reference Androudis2002, 16–27). His red and gold hat, known as a skaranikon, was adorned with the images of an enthroned emperor and signified John's rank, title and connection to the emperor (Parani Reference Parani2007, 108; Macrides, Munitiz and Angelov Reference Macrides, Munitiz and Angelov2013, 332–6).

Fig. 10. Icon with Christ Pantocrator and donors. Byzantium, Constantinople artist, c.1363. Wood (lime) panel with raised borders, gesso, mixed techniques. 106 × 79 × 268 cm. Inv. no. I-515. Courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Fig. 11. Detail from Icon with Christ Pantocrator and donors. Right margin showing John in prayer. Courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

In this icon it becomes clear that Alexios and John wished to draw attention not only to their rank and status but also to their special relation to both the emperor and Christ. The references to the ruling family of the Palaiologoi in John's ceremonial costume and the skaranikon emphasise the source of his authority and his proximity to the person of the emperor. His portrait functioned as a visual reminder of the brothers’ ties to the emperor and the imperial validation and recognition of the rights and property of the Pantokrator monastery. Parani (Reference Parani2007, 125–6) adds another dimension to portraits with ceremonial ritual garments, suggesting that such traditional court garments emphasised a diachronic and traditional Byzantine collective identity, especially at a time when foreign, Ottoman and Italian fashion was influencing Byzantine elite dress. Such a traditional Byzantine look would resonate with the two brothers’ military efforts to push away enemy attacks and restore order to the Byzantine borders.

The relation with Christ is also exalted in this icon. Following a typical visual vocabulary of patronage, John appears as a tiny figure in the icon's frame, kneeling and praying (Sevcenko Reference Sevcenko1993; Carr Reference Carr2006). The presence of Christ Pantokrator connects John and Alexios to the Pantokrator monastery, and both captures and perpetuates the act of donation. It highlights Christ as the source of their power and points to the privileged relation between Christ and the two brothers, since he is receptive of their prayer. This triple emphasis on rank, connection to emperor and Christ is a vehicle of self-representation fitting for elite patrons of an important Athonite monastery. We should not forget that the audience of such an icon were not isolated, ignorant monks: many monks in Athonite foundations were themselves members of the elite, highly connected to the Byzantine and other medieval courts, so the message of this icon is neither one-dimensional nor simply focused on religious piety.

The dedicatory inscription found in Alexios and John's tower at Amphipolis provides further evidence for the self-representation of the two brothers in the areas under their control. While their names, social status and activities are mentioned, there is no reference to the emperor or to their relation to the imperial family (Eugenidou Reference Eugenidou1997, 91). Here the two brothers present themselves as the founders of the Pantokrator monastery and sponsors of the tower, thus placing emphasis on their own actions and wealth to negotiate their authority and not on their connection to the emperor. I think that the message here has slightly changed because the audience is different. The tower was a visual marker of the two brothers’ ownership, economic activities and control of that territory, seen daily by the local population. The absence of the emperor here might be an effort by the two brothers to separate themselves from fiscal and military policies pursued by the Byzantine state, mainly the increase of taxes and inability to protect the borders. Considering that taxation under Ottoman rule in Macedonia and Thrace was significantly lower than under Byzantine rule, it is not surprising that border areas showed little or no resistance to the enemy (Frankopan Reference Frankopan and Haldon2009, 120; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2011, 43). It should be equally unsurprising that the connection to the Byzantine emperor was not advertised in the tower of Amphipolis.

Their military campaigns, building programme and self-representation through artistic means and inscriptions illuminate Alexios and John's strategies of negotiating their authority and articulating their role in coastal Macedonia. In these strategies, the connection to the emperor could be emphasised or underplayed depending on the audience. In contrast, the imperial connection is highlighted in official correspondence between Alexios, John and the imperial court and in official documents, including acts of donation and selling and buying contracts. For example, in all of their official documents that have survived in the archives of Pantokrator monastery, there is great emphasis on the connection and family ties of the two brothers with the emperor, where they are always referred to as the emperor's relatives and loyal servants (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 79–81, no. 5 [1357]; 85–8, no. 7 [1368]; 88–90, no. 8 [1369]; 95–102, no 10 [1384]). Alexios and John's self-presentation in different contexts supports the idea that the two brothers presented themselves in a different light when they were addressing local communities and when they were addressing the imperial court and the emperor. The absence or presence of the emperor in their rhetoric is indicative of the two brothers’ interaction with the emperor. They used the imperial institutions and the imperial office in validating official documents, in dealing with bureaucracy and getting tax exemptions. But in their role as governors of coastal Macedonia and Thasos, Alexios and John relied primarily on their own efforts, military forces and wealth. Even when they were in need of military and financial support, they turned elsewhere. In their efforts to protect the Northern Aegean from piratical attacks, they sought Venice's help in 1373 and joined forces with a small Venetian fleet to protect Mount Athos from Turkish pirates (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 9). After that experience, John also became a Venetian citizen, following the example of other Byzantine elites and high court officials (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 9; Harris Reference Harris, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 128–9). The two brothers’ complex relations with Byzantine imperial authority and with other foreign powers, such as Venice, is further highlighted in John's will (Kravari Reference Kravari1991, 99–100, no. 10 [1384]). John distrusted the military and economic ability of the state to defend its borders successfully. The foundation of the Pantokrator monastery and John's Venetian citizenship were connected to his efforts to find alternative networks of support that could protect him, his assets and the local population in the areas under his control more successfully than the Byzantine emperor. At the end of his life, he donated all of his and Alexios’ possessions to their own monastery, including the fortifications. John clearly thought that the Pantokrator monastery was better equipped to maintain control and protect the local population than the Byzantine state (for Late Byzantine investment in Mount Athos, see Pavlikianov Reference Pavlikianov2001, 197).

Knowing your audience: the case of the Gattilusi

Like Alexios and John, Francesco I Gattilusio had supported John V in his elevation to the throne during the second civil war. In recognition of his military services, Francesco was married to the emperor's sister, Maria, and received the island of Mytilene and the area of Ainos in Thrace as dowry (Hasluck Reference Hasluck1908, 252–3; Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 251–2; Wright Reference Wright2014, 78–9). Between the mid-fourteenth and mid-fifteenth century, the Genoese family of Gattilusio, who had started as merchants and pirates, married into the Byzantine imperial family and gradually became rulers of significant parts of the Northern Aegean, including the Thracian coastal town of Ainos, Old Phokaia, Mytilene, Samothrace, Thasos and Lemnos (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Map of areas ruled by the Gattilusi in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (map by author).

The rule of the Gattilusi has recently been the subject of extensive research (Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012; Wright Reference Wright2014), and thus my discussion here is brief. The case of the Gattilusi serves here as a comparison to Alexios and John's policies and allows a broader understanding of the political agendas of Late Byzantine borderlords and their material manifestation in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In the comparison between the Gattilusi and Alexios and John, I am more interested in the variety of visual means the Gattilusi employed to self-represent and establish their authority in the area under their control and in the articulation of their relationship with the Byzantine emperor.

In becoming ruler of Mytilene, Francesco I Gattilusio recognised that an imperial grant alone was not enough to successfully negotiate his authority and win the trust and loyalty of the local population. The first half of the fourteenth century had been marked by a series of failures of Latin lords to successfully negotiate their authority in the Aegean, leading to riots and violent conflicts with local populations (Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 253–4). The generally negative atmosphere against Latins, and the resistance to Latin authority by local populations, pointed to the need for a different strategy. The Gattilusi focused on making strong connections with people under their rule, respecting their traditions, cultural values, political affiliations and history. They attempted to connect with the local population and create a shared narrative by emphasising their connections to the Byzantine court and articulating their own membership in the Byzantine Empire (Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 248). For example, they relied heavily on Byzantine imperial iconography as a vehicle of political promotion and a constant reminder of their ties to the imperial family (Hasluck Reference Hasluck1908, 265–6; Ousterhout Reference Ousterhout, Ödekan, Necipoğlu and Akyürek2013, 93–4). The founder's inscription dated 1373 in the Middle Gate of the Mytilene castle displays the insignia of the Palaiologoi (ΠΑ) surrounded by the Gattilusi coats of arms on each side (consisting of scales patterns and a crowned eagle walking to the right) (Fig. 13) (Acheilara Reference Acheilara1999, 22, fig. 22). This coexistence of the Gatillusi's coats of arms with Palaiologan insignia, such as the cross beta (four betas arranged around a cross, understood as an abbreviation of the phrase Βασιλέυς Βασιλέων Βασιλέυων Βασιλεύοντων: ‘King of Kings Ruler of Rulers’), can also be seen in the main tower in the Great Enclosure in the castle of Mytilene and in some of the Gattilusi's sarcophagi (Hasluck Reference Hasluck1908, 263–4; Acheilara Reference Acheilara1999, fig. 15). This visual vocabulary of power that connected the Gattilusian rule with the Byzantine emperor also extended to Gattilusian coins (Grierson Reference Grierson1982, 283; Bellinger and Grierson Reference Bellinger and Grierson1999, 88; Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 248–9; Androudis Reference Androudis2002, 27–30). For example, some of Francesco's coins display on the obverse Palaiologan insignia, such as the cross with the four betas, and the Gattilusi's own coats of arms on the reverse (Schlumberger Reference Schlumberger1954, 437; Lunardi Reference Lunardi1980, 247). Drawing an analogy from a typical Palaiologan coin with the emperor on one side and Christ on the other as a visual reminder of the source of the Byzantine emperor's power, the Gattilusi coins can be understood as a strong political statement about the Byzantine emperor as the source of the Gattilusi's power.

Fig. 13. Founders’ inscription at the gate of the castle of Mytilene with the Palaiologan initials (ΠΑ) and the Gattilusi coats of arms (scales patterns and crowned eagle walking to the right) (reproduced, with the author's permission, from Reference AndroudisAndroudis forthcoming).

Wright argues that the Gattilusian visual vocabulary of power further evolves from the 1420s onwards, when insignia of Palaiologan and Gattilusian authority did not just stand side by side but were now combined to create new symbols of power; this also corresponds to the appearance of compound names (Palaiologos-Gattilusio) that started being used in inscriptions in the same period (Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 249–50). For example, one plaque embedded in the Mytilene castle wall shows a double-headed eagle and the four betas (all symbols associated with the Palaiologoi), but on the eagle's chest one can see engraved the coats of arms of the Gattilusi, creating hybrid new symbols (Fig. 14) (Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 249–50). A similar combination of insignia can be found on the coastal fortification walls of Old Phocea, also under Gattulusian control (Hasluck Reference Hasluck1908, 257–8; Androudis Reference Androudis2002, 26). A marble slab later embedded in a house's facade includes three panels with the monogram of the Palaiologoi, a double-headed eagle bearing an escutcheon with the Gattilusi arms in his chest, and finally the Gattilusi coats of arms. The inscription underneath the panels, dated to 1423–4, identifies Dorino Gattilussio (1428–55) as the lord of Old Phocea. Dorino used the double-headed eagle with the Gattilusi coats of arms also in his coins. In an example from the British Museum coin collection, a copper coin from Dorino's rule shows a double-headed eagle with the insignia of the Gattilusi in his chest in the obverse and a cross with the four betas in the reverse (Fig. 15) (Schlumberger Reference Schlumberger1954, 444, pl. XVI, 30; for the appearance of the four betas in Byzantine and Gattilusian coins, see Androudis Reference Androudis2002, 27–30). The coin iconography is indicative of the Gattilusi self-representation. On the one hand, they are adopting a narrative of the Crusades and Western domination of the Eastern Mediterranean following a visual tradition known from the silver denier tournois circulating in Frankish Greece in the thirteenth century. On the other hand, they separate themselves from other Western lords, combining Gattilusi and Byzantine insignia and creating a hybrid visual language of identification and power (Grierson Reference Grierson1982, 283). This allows the Gattilusi to negotiate their authority and reinvent their identities and affiliations, while masking ethnic and religious differences between them and the ruled populations.

Fig. 14. Marble block with three panels containing the Palaiologan initials, a double-headed eagle with the Gattilusi coats of arms in his chest and an eagle walking to the left, Mytilene castle (reproduced, with the author's permission, from Reference AndroudisAndroudis forthcoming).

Fig. 15. Fifteenth-century alloy coin of Dorino Gattilusio, Lordship of Mytilene, British Museum (museum number 1854,0818.38). Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

The development of a visual grammar that tied the Gattilusi rule with the Palaiologoi had to be complemented by an appealing political agenda and a robust building programme. The Gattilusi had to tackle the pragmatic needs of the territories under their rule, especially the need for safety, the maintenance of fortifications and the development of economic activities and maritime commerce. Their building programme was very similar to that of Alexios and John, and focused on fortifications in coastal areas and safe ports to stimulate sea commerce. They were very proactive in both repairing and rebuilding pre-existing castles and adding new fortifications to the areas they controlled. For example, Francesco I, immediately after receiving Mytilene, repaired the entire castle of Mytilene, respecting the course of pre-existing Byzantine walls and incorporating in his new walls Byzantine structures, as well as spolia from the ancient theatre (Loupou-Rokou Reference Loupou-Rokou1999, 172; Acheilara Reference Acheilara1999, 18–19). The castle was divided into two tiers (upper and middle) occupied by the Gattilusi and their administration, while the locals were living outside the main castle in a nearby quarter that was also fortified. The only remains from that period are the central inner line of walls and the church of St John, while everything else dates form the Ottoman period (Hasluck Reference Hasluck1908, 259–65; Loupou-Rokou Reference Loupou-Rokou1999, 172–3; Acheilara Reference Acheilara1999, 11; Georgopoulou-d'Amico Reference Georgopoulou-d'Amico2001, 52–3).

On the island of Samothrace, another North Aegean island under Gattilusian control, two major fortifications at Chora and Palaiopolis and a coastal tower known as the tower of Phonias on the north side of the island are associated with their rule (Georgopoulou-d'Amico Reference Georgopoulou-d'Amico2001, 58–9; Tsouris Reference Tsouris, Kavvadia and Damulos2012, 573; Androudis Reference Androudis and Karagianni2013, 233–9). Samothrace was given to Palamedes Gattilusio at the beginning of the fifteenth century with the expectation that he would defend and protect it and govern in the name of the emperor; it is important to note that Palamedes was also related to the Palaiologoi directly, since his daughter was married to the Byzantine Emperor John VI, exemplifying again the role of intermarriages in the political management of the empire (Kiousopoulou Reference Kiousopoulou2011, 61; Androudis Reference Androudis and Karagianni2013, 233). There are two interesting elements in Palamedes’ fortifications. First, the rapid response to the need of fortification; based on inscriptions referring to the date of the fortifications’ construction, the Gattilusi had significantly boosted the defence of the island in only three years (1431–3) (Androudis Reference Androudis and Karagianni2013, 238). Equally interesting are the numerous Greek and Latin inscriptions on the fortification walls addressing both locals and Genoese, and introducing Palamedes as the protector of the island and responsible for strengthening its defence (Androudis Reference Androudis and Karagianni2013, 235–6; for similar inscriptions in Greek in the fortifications at Ainos, see Hasluck Reference Hasluck1908, 254).

After becoming rulers of Thasos (1419), the Gattilusi concentrated their efforts on maintaining and expanding the fortifications at Limenas to further serve their political and economic agendas. Besides their connection to the emperor, the Gattilusi were also following in the footsteps of Alexios and John and their successful government, thus also embedding their narrative within that of the island's recent past. At Limenas, the Gattilusi rebuilt the acropolis with strong walls and towers. At least the two square towers still standing in the acropolis circuit walls, the cisterns and a chapel in its interior, are probably associated with the Gattilusi rule (Fig. 16) (Dadaki and Giros Reference Dadaki and Giros1994, 387; Koder Reference Koder1998, 182; Karagianni Reference Karagianni2010, 133–4). The most prominent feature of the acropolis is its monumental gate that is entirely built with large blocks of spolia, matching the aesthetics and building material of the port fortifications, adding to the castle's monumentality (Fig. 17). According to Cyriacus of Ancona, the use of spolia also extended to the beautification of the port, with an array of marble statues along it (Bodnar and Mitchell Reference Bodnar and Mitchell1976, 42–4). The Gattilusi's building activities at Thasos reflect their concerns about security, but also their interest in monumentality. Notions of wealth, control and monumentality travelled well in a more international commercial and political stage, since the Gattilusi wanted to reintroduce Thasos and the port of Limenas as an important hub in the sea trade between the West, Constantinople and the Black Sea. The imported pottery of the fifteenth century found at Limenas from the Black Sea, Spain and Italy represents the long-distance trade networks of Genoa in which the Gattilusi were involved; hence, it speaks to their successful strategies to connect Thasos’ with wider commercial, cultural and political networks beyond Northern Aegean and the Byzantine Empire (François Reference François1995, 125–30, 141).

Fig. 16. Tower from the upper acropolis, Limenas, Thasos (photo by author).

Fig. 17. The monumental gate of the upper acropolis with extensive ancient spolia at Limenas, Thasos (photo by author).

The Gattilusi's building activities, political propaganda and visual language underscore the ways in which they crafted their own local identities and negotiated their affiliations both with the local communities under their rule and with the Byzantine court. A shared sense of belonging and a strong connection to the local population facilitated their negotiation of authority, enhanced the economic and demographic stability in their ruling territories and promoted their own political and economic agendas.

LATE BYZANTINE MODES OF RULESHIP AND FRONTIER CONTROL

The stories of Alexios, John and the Gattilusi offer a different avenue of exploration pertaining to the changes in Late Byzantine mode of government and border administration, particularly in its last century, from the mid-fourteenth to the mid-fifteenth century. The choice of borderlords, their expanded roles in frontier areas and the nature of their authority derive from the political and economic realities of the Eastern Mediterranean in the fourteenth to fifteenth centuries, particularly the empire's limited resources, territorial loss and the rise of new economic and political powers around its borders. These borderlords are also associated with imperial policies in times of extreme political and military stress. John V's grants to Alexios, John and the Gattilusi coincided with the end of the civil wars, a time when both the empire's and traditional elites’ resources were exhausted and Byzantine territories were in immediate need of protection. Framed in a context of decline, John V's grants and rights bestowed upon these borderlords can be understood as proof of the political and economic deterioration of the Late Byzantine Empire. They support the idea that the Late Byzantine emperors were unsuccessful in ruling and protecting their territories and in resisting pressures from foreign and domestic elites. While I do not wish to underplay the severe political and economic challenges of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Byzantine imperial policies can be better understood when seen within a framework of wider changes in the political landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean (see also Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012). They should also be studied in relation to changes in the function of the imperial office in the last Byzantine century. In her excellent book about the Byzantine state and the political landscape of the fifteenth century, Tonia Kiousopoulou (Reference Kiousopoulou2011, 130–2) introduces the Late Byzantine emperors more as managers and administrators than as absolute rulers, who had to adapt to the political and economic realities of their time and were forced to allocate to individuals and groups tasks that were previously the state's responsibility. In the process, imperial rule became more inclusive of various social groups, such as the imperial family and the aristocratic circles, as well as the city council and even the local population, who would participate in imperial policies and decision-making in various degrees (Kiousopoulou Reference Kiousopoulou2011, 86–114). A more fruitful way of considering the role of borderlords beyond a frame of decline would thus be to recognise an imperial ruling system that invited the participation of different agents, was more flexible in its mode of exercising control, and used an elaborate system of social and economic mechanisms to regulate its relation with all agents involved in political and military action.

As we saw earlier in this article, the imperial grant of lands and tax exemptions had been in the empire's ruling kit of the periphery for centuries, but the frequency of such grants in Late Byzantium is so startling that it introduces a new default modus operandi for running the empire (Magdalino Reference Magdalino2002, 263–4; Bartusis Reference Bartusis2013, 610–13). From the thirteenth century onwards, the number of these grants had significantly increased; they become hereditary and (as in the cases of Alexios and John, and the Gattilusi) they also came with full administrative and judicial authority (Haldon Reference Haldon and Haldon2009, 188; Bartusis Reference Bartusis2013, 274–82). Such grants weakened the state and deprived it of resources, and moreover reinforced the power and wealth of elite groups in the provinces, thus giving rise to new agents of power who supplanted imperial authority in the borders and only nominally adhered to the central administration (Laiou Reference Laiou1973, 147–9). Their power could pose a threat to imperial authority, since the elites’ allegiance to the Byzantine emperor was only as strong as the benefits he could offer them at a given time (Standen Reference Standen, Power and Standen1999, 21–2; Kazhdan and Wharton Reference Kazhdan and Wharton1985, 64–5; Magdalino Reference Magdalino, Beaton and Ricks1993, 9–11; Zartman Reference Zartman and Zartman2010, 14). Many were deeply rooted in frontier areas, with first-hand knowledge of the landscape and the people with large estates and properties, and could easily gain popularity with the locals and the army if they could successfully protect the frontiers, especially in times when the empire was failing to do so (Magdalino Reference Magdalino and Angold1984; Maksimović Reference Maksimović1988, 123; Angold Reference Angold and Angold1984b, 237).

These grants can, however, also be understood as a balancing act that allowed the emperors to exploit and accommodate a range of different and often clashing interests (Angold Reference Angold, Angelov and Saxby2013, 92). The competition for such grants and for favour and proximity to the emperor more generally was fierce, and provided emperors with the means of maintaining the loyalty and support of elites, managing the ambition and power struggles of antagonistic groups and regulating their access to resources and power (Frankopan Reference Frankopan and Haldon2009, 114–26; Haldon Reference Haldon and Haldon2009, 181; Stathakopoulos Reference Stathakopoulos2009, 96). This can clearly be seen from both the allocation and the confiscation of lands, which served as ways for emperors to manage power struggles and regulate society (Haldon Reference Haldon and Haldon2009, 195; Bartusis Reference Bartusis2013, 545–8). This balancing act extends to imperial efforts to keep frontier zones safe and within their sphere of influence without bearing the costs for their protection. Instead, borderlords were responsible for the costs of defence, such as repairs and new construction of fortifications, as well as any other investments in the frontier zones, such as ports. More importantly, at a time with no real imperial navy to speak of, these were groups which could provide the Late Byzantine emperors with a ready fleet that could patrol the coasts and islands and respond to the increased aggression of Turkish fleets (Wright Reference Wright, Harris, Holmes and Russell2012, 256–7).