We are not the police, nor paid undercover agents of the morality of society. Our obligation is to the objects.

– A conservator’s response to the question whether conservators should treat antiquities they suspect have an illicit originFootnote 1

Introduction

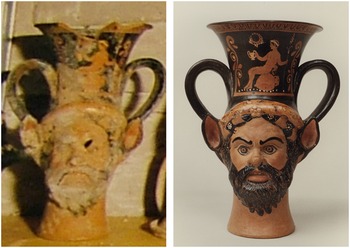

Ricardo Elia’s remark that “collectors are the real looters” highlights that the looting of archaeological sites is ultimately demand driven. That is, blame for the destruction of the archaeological record is not to be put on the often impoverished looters who unearth the objects but, rather, on the wealthy consumers who buy them.Footnote 2 But who else might have a share in the blame? Which people are involved in transforming freshly dug up loot into saleable commodities and esteemed display pieces in private and public collections? As has been pointed out in the literature, the antiquities trade is facilitated by various academic experts who lend their professional services to it.Footnote 3 These academic actors include conservators who clean, stabilize, repair, and mount unprovenanced or poorly provenanced objects for the trade (see Figure 1); scientists and science consultancies who determine the authenticity of such objects; experts and connoisseurs who likewise determine authenticity and also attribute the objects to particular cultures and workshops and judges their esthetic, cultural and scholarly importance.Footnote 4

Figure 1. Apulian red-figure vase (janiform kantharos), fourth-century BC, before and after conservation. Left: detail from photo found in the Becchina archive. Right: photo found in the Symes/Michaelides archive (courtesy of Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis, Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies).

How should this involvement in the trade be countered? Where should academics be informed of how their expertise may be employed in direct and indirect ways to further criminal activity and the obliteration of the archaeological and cultural heritage? And where could academics get the tools to proactively counter market demand for loot? For future generations of professionals, one answer to these questions is: through their university education. Therefore, it is of crucial interest to raise the issue as to what is today taught in university programs in relevant disciplines about the illicit antiquities trade and forms of academic entanglement in it. To my knowledge, this subject has not been studied before.Footnote 5 This article aims to take a first step toward such an enquiry. To keep the study within bounds, it focuses on university programs for conservators, but the issues raised in the article should be applicable to higher education in a range of other disciplines that study material remains from the past, such as archaeology, art history, epigraphy, museum studies, and numismatics.Footnote 6 The ambition of the article is to be constructive and forward looking, and, hopefully, this contribution will be useful and inspirational both for researchers designing further research in this direction and – arguably more importantly – for program leaders and others involved in teaching when they develop programs and learning activities.

Among the reasons that I want to turn attention to university education is that students spend many years at university, and the formal and informal learning that students undergo during this prolonged period of time presumably has a profound impact on shaping their identities and in guiding the decisions they take during the remainder of their careers. Students not only acquire skills and knowledge in their subject disciplines, but they also partake in a process of socialization establishing a range of norms and values that, importantly in this context, includes notions of what are one’s professional responsibilities – and, conversely, what they are not.Footnote 7 This socialization into a professional identity and the creation of notions of professional obligations is interlinked with the forming of a social identity and corresponding obligations to surrounding society. Martha Nussbaum argues that education should cultivate three main abilities: first, the capacity for a critical perspective of oneself and one’s traditions; second, the ability to view oneself not only as belonging to a particular group but also as a citizen of the world, bound to all other human beings by ties of recognition and concern; and, third, the ability to understand the perspectives of others.Footnote 8 In my reading of Nussbaum, “tradition” and “group” encompasses both larger and smaller entities, ranging from, say, Western (white, middle class, and so on) tradition/group belonging to disciplinary or institutional tradition/group belonging. Nussbaum’s goals are useful to consider when discussing the aims and content of teaching about looting, illicit antiquities trade, and professional responsibilities. They are especially pertinent when it comes to discussion on obligations to actively oppose the trade and its consequences.

As Neil Brodie has observed, most academic experts do not work on recently surfaced objects. Those that do comprise a tiny minority. Yet, as Brodie highlights, this handful play a significant role in at least two respects. First, many are regarded as distinguished professionals within their fields, and, thus, their attitudes and behavior provide a strong normative influence over junior colleagues and, it may be added, over students. Second, it only takes a few to give the market the needed expertise.Footnote 9 In light of this observation, it is worrying that in Kathryn Walker Tubb’s survey of conservators’ attitudes to treating unprovenanced antiquities, published in 2013, as many as one in 20 of the respondents opined that conservators should always treat an object, even if they hold a suspicion of it having an illicit origin. Some of the free text comments included: “I see my professional task is [to] treat something to preserve it. Let others deal with ownership” and “We are not the police, nor paid undercover agents of the morality of society. Our obligation is to the objects.”Footnote 10 The comments speak volumes on how these conservators draw the boundaries of their responsibilities.

Around half of the respondents in Tubb’s survey replied “no” to the question whether their training had contained anything about looting, theft, and the illicit trade in antiquities.Footnote 11 This suggests that coverage of this topic has varied between programs: some have addressed it, while other have not (or, perhaps, the coverage was so limited that it is not remembered by respondents). This study follows up on Tubb’s result concerning professional training for conservators, but I have opted not to treat the question of coverage in university programs of the ethical and legal considerations that are attendant on unprovenanced antiquities as only a yes or no question – as something that is either taught or not taught. It seems more relevant to extend the question and ask what is taught about conservators’ relation vis-à-vis the antiquities trade and, importantly, paying attention to the conflicting messages about this subject that might be delivered through university education.

That contradictory notions of conservators’ position in regard to unprovenanced antiquities do arise in the context of teaching may be illustrated through my own experience as a guest lecturer in conservation studies. For many years, I gave a lecture for students about the illicit antiquities trade and conservators’ relation to the trade. To most students, this was an entirely new subject, and they were quite perplexed and shocked to learn about it. On one occasion, when I talked about a particularly well-known antiquities dealer (and television celebrity) selling unprovenanced – and, thus presumably, recently looted – Chinese grave goods, the students looked more perplexed than before. A student then explained that another guest lecturer, who also runs a private conservation company, had brought objects from this dealer for the students to practice on. The items assigned to the students were Chinese porcelain – a category of objects that generally has been in circulation since its production – and, thus, these particular objects were unlikely to have originated from looted archaeological sites. Still, assigning conservation students to treat merchandise belonging to a dealer, whose assortment includes archaeological objects generally lacking provenance, is not a straightforward issue. When a person who stands in an authoritative position in relation to the students assigns them such material it might suggest to them that the business activities of the dealer (and other dealers who likewise vend unprovenanced archaeological objects) are beyond reproach and even have the approval of the university department delivering the program. A planned learning outcome of this teaching situation was to give the students experience in treating ceramic material, but another (I presume) inadvertent learning outcome could have been that it instilled the notion that the trade in unprovenanced archaeological objects is not problematic, at least as far as conservators should be concerned.

I think that this case neatly illustrates that universities teach much more than they claim to teach.Footnote 12 Apart from what is intended and explicated, educational interaction (like all forms of communicative interaction) inevitably creates unintended and implicit learning. Importantly, this kind of learning, which John Dewey refers to as “collateral learning” and which in subsequent pedagogical literature has been described as the result of a “hidden curriculum” embedded in the official curriculum, quite often runs counter to the formal aims of the education.Footnote 13 In this study, I seek to treat both the official and the hidden curriculum concerning looting, illicit antiquities trade, and conservators’ responsibilities in relation to this trade. The study focuses on analyzing the content of course literature. In the analysis, I examine parts in course literature that specifically address illicit trade and the conservator’s duties vis-à-vis the trade. In addition, I treat instances in textbooks where this topic is not addressed but where its absence arguably has implications for forming students’ perception of professional responsibility and accountability in regard to the illicit antiquities trade. These instances are ones where various conservation treatments are exemplified through the treatment of archaeological objects that lack provenance and that, in all probability, derives from recent looting.

The article is structured as follows. First, it briefly looks at how the conservator’s expertise may facilitate this trade. Second, it presents the discussion that has taken place on the conservator’s moral and legal obligations in relation to the antiquities market. Following this section, the study and its results are presented and discussed. The article proceeds with exemplifying how teaching professionals responsibly vis-à-vis the illicit antiquities trade may be related to discussions on the decolonization (and de-neocolonization) of the curriculum and the museum. The final section provides conclusions and questions for further consideration concerning teaching about the illicit antiquities trade and professional ethical concern and practice.

Conservators serving antiquities trafficking

Conservation treatment “clean” “dirty” objects in both a literal and figurative sense. A newly dug up object is dirty and quite often damaged and broken. Apart from ancient breaks and injuries, there may be recent damage incurred when the object was unearthed and transported from the site. By removing incrustations and mending breaks, the conservator makes the object more physically attractive and thus enhances its desirability in the eyes of the customers (see Figure 1). This cleaning and mending also obliterate evidence of the object’s origin and of its modern history. For example, the removal of soil and root marks may erase crucial clues as to where an object was dug up, and the reassembly of the object obscures recent breaks and tool marks.Footnote 14 The involvement of conservators in the laundering process is not necessarily limited to physical interventions carried out on objects. By participating in studying, publishing, acquiring, and exhibiting unprovenanced or poorly provenanced objects, conservators at museums and research institutions provide dealers and collectors with a veneer of academic and institutional respectability.Footnote 15 Reports and catalogue entries often pass by uncomfortable questions concerning an object’s modern history and legal status, thus reinforcing the silences created through physical intervention.

This means that questions pertaining to ethical and legal obligations in relation to the trade not only concern conservators in private practice who treat objects for dealers but also two other categories of conservators: those employed by museums (on a permanent or contractual basis) to examine, treat, and document objects in museum collections and objects considered for acquisition and the conservators and conservation scientists employed by universities and institutes who study and publish objects in private or public collections.Footnote 16 These publications (as I will come back to) are used in university education and thus have direct bearing on the present study.

The discussion on the involvement of conservators in antiquities trafficking

Although conservation work is crucial for the creation and maintenance of a market for antiquities and although a discussion on ethics in conservation goes back at least to the 1970s,Footnote 17 the conservator’s role in the antiquities trade did not become part of the ethics discussion until the 1990s. Tubb’s edited volume Antiquities Trade or Betrayed: Legal, Ethical and Conservation Issues published in 1995 was the starting point of the debate.Footnote 18 Several articles appeared in the following years.Footnote 19 In these publications, the profession was criticized for a tendency to focus on the object only and for not seeing the larger context to which it belonged. Specifically, the critique was levelled against a reluctance to see the potential negative consequences of treating unprovenanced objects, in that such treatment would aid the market and thus indirectly contribute to further looting. Some writers pointed to the fact that existing codes of ethics did not adequately cover conservators’ responsibilities in relation to the trade.Footnote 20 Since then, the spate of publications has slowed down, but Sanchita Balachandran and Brodie have published two important contributions in 2007 and 2017 respectively.Footnote 21 Balachandran widens the discussion on conservators’ responsibilities in relation to the trade to include an obligation to inform clients bringing unprovenanced archaeological objects about the consequences of collecting such material. Brodie, taking a point of departure in a court case on the high-end spectrum of the trade – an ancient marble statue sent to Colin Bowles Limited for restoration that was seized and eventually returned to Libya – highlights the possible legal consequences for conservators of treating unprovenanced objects.Footnote 22

Since the late 1990s, several conservators’ organizations have updated their codes. For example, the UK organization, the Institute of Conservation (ICON), stipulates in its Code of Conduct from 2014:

4.14. You must establish to the best of your ability that you are not agreeing to work on stolen or illicitly traded cultural objects, unprovenanced archaeological material or any items wrongfully taken, unless to establish wrong-doing or exceptionally to save the object from rapid ongoing deterioration.

4.15. You must contact authorities and the current custodian or owner if you uncover in the course of your work evidence that items could have been disguised, stolen or illicitly traded. If you hold a reasonable suspicion that the current possessor is not the rightful owner, relevant authorities must be informed.Footnote 23

While codes such as this one mark a significant improvement compared to the earlier ones, it is paramount to note that the question of conservators’ duties in relation to treating objects that may be suspected of having an illicit origin is not only a question of ethics but also a legal issue. Discussing UK law, Janet Ulph and Ian Smith have argued that Article 328:1 of the Proceeds of Crime Act might apply to conservators engaging with illegally traded objects: “A person commits an offence if he enters into or becomes concerned in an arrangement which he knows or suspects facilitates (by whatever means) the acquisition, retention, use or control of criminal property by or on behalf of another person.”Footnote 24 Note that “suspicion” is the sufficient criminal requirement in this case. Recall Tubb’s survey, where one in 20 of the respondents believed that conservators should treat an antiquity even if they suspect that it has an illicit origin. The respondents in Tubb’s survey worked in many different countries (the United States and the United Kingdom being the most cited ones), and the required requisite of a crime differs between jurisdictions, but, in applying Ulph and Smith’s argument beyond the United Kingdom, it can be argued that Tubb’s survey shows that one in 20 conservators opined that conservators should commit crimes.

It is likely that the respondents were unaware of the possible legal consequences of handling pieces that one suspects are illicit. This presumably reflects that conservators’ involvement in the trade has predominantly been discussed as an ethical matter. The argument has evolved around whether the conservators who treat such objects transgress the boundaries of ethics, but less attention has been paid to whether they also transgress the boundaries of law. This in turn relates to the fact that conservators rarely figure in criminal cases relating to antiquities trafficking. Perhaps this trend is now broken. In July 2019, when charges were levelled against New York art dealer Subhash Kapoor, two conservators in London and New York were charged as alleged co-conspirators.Footnote 25 The case highlights the need for conservators, and prospective conservators, to be aware of the potential legal repercussions of their actions in relation to the antiquities trade.

Method and material

This study was carried out in the following way. A list of degree programs in conservation studies was created by web searches with the search terms “conservation studies,” “art conservation program,” and related search terms. Three bachelor’s degree programs and one master’s degree program at four different universities were randomly chosen from the list.Footnote 26 The sole criterium for choosing a program was that it included training in conservation of archaeological objects in the curriculum. The programs chosen were in two different countries (two programs in each country) that both have a significant antiquities market (and where there has been a significant debate on the illicit antiquities trade). The study mainly aimed at analyzing the course literature in the programs. In addition, it strived to look at the content of lectures, seminars, and assignments through available documents. Given the limited amount of time and resources at my disposal for the study, complementary forms of analysis, such as classroom participatory observation, were not undertaken.

The sample of programs was kept small to allow for close scrutiny of the course literature in the respective courses within the restricted time available. It was felt that, with the ambition of this article to inspire further discussion on teaching and research on teaching, the insights generated from a limited sample would provide at least some empirical grounding and related reflections from which to begin this discussion. A small sample obviously raises questions of representativity. Nothing was found during the course of the investigation to indicate that these randomly chosen programs were atypical regarding quantity and quality in the coverage of looting, illicit antiquities trade, and professional responsibility (and the textbooks encountered in the study are standard textbooks in many programs), but how these programs compare to other university programs in conservation studies must be left for further enquiry.

Such a study, which ideally should also encompass programs in other relevant disciplines, would presumably find a diversity of approaches to teaching about this topic both within and between disciplines – from no, to cursory, to in-depth coverage. There might be variation along geographic (and linguistic) borders, perhaps reflecting a country’s position as a “source,” “transit,” or “destination” country as well as the amount of public and intradisciplinary debate that there has been on the issue of professional collusion with the illicit antiquities trade in respective countries and languages.Footnote 27 The personal (research) interests and experiences – of whatever kind – in and with unprovenanced antiquities among members of teaching staff might also be a contributing factor to the degree and kind of coverage provided.

Further, to consider an “average” or general trend among a large number of programs is only relevant to a degree. To repeat, the market only needs a relatively few academic experts to operate. Thus, it matters whether particular programs provide adequate training regarding professional responsibilities in relation to the antiquities trade. In their respective countries, the programs in the study provide a fair part of the annual output of conservators for the job market.

For all programs, some information, such as the general structure of the program and course synopses, was publicly available on the program websites. To obtain further material, I contacted the program leaders at the respective programs. Regrettably, the program leaders at two programs (named Program A and B in the study) never wrote back, despite numerous emails sent over a prolonged period of time. However, the reading lists for these programs were accessible on the program websites. From a third program (Program C), which did not post reading lists on its website, I eventually got a reply from a representative of the program, stating that “looting, theft and the illicit trade in antiquities is discussed in treatment classes” but that no reading lists or any other documents could be made available to me. My follow-up question on whether it was possible to expand on how these “discussions” were framed and if I could be informed whether the program advocated any particular position that conservators should take when asked to treat unprovenanced or poorly provenanced antiquities received a polite “no.”

It was particularly unfortunate that no further information could be obtained from this program since it gives (or has given) a module devoted to the conservation of objects from a heavily looted part of the world and another module where students work on objects belonging to a museum known for its lack of acquisition ethics and its disrespect for the law. It would have been interesting to find out how the topic of the illicit antiquities trade and professional collusion with the trade were dealt with in these courses and the program more generally. In contrast to these (non-)replies, the program leader and module leaders at one program (Program D) provided all the requested information, including reading lists, seminar questions, power-point presentations for relevant lectures, and so on. The program leader and module leaders wrote that they wanted to have a broader coverage of the illicit antiquities trade in the future (and I was asked to suggest reading). There could be numerous reasons why the ones responsible for the first three programs chose not to participate in the study. These reasons could range from lack of time to that the question of professional involvement in the trade is a sensitive topic or that it would be embarrassing to admit that there is little teaching about the topic in a program curriculum.

In the analysis of the literature in Programs A, B, and D, I looked at how the illicit trade and conservators’ responsibilities was covered in the reading lists for core modules in the programs (optional modules were not included in the study). The total amount of reading consisted of hundreds of publications (including books, articles, webpages, and so on), and it was necessary to apply a degree of selectivity when going through this material. I browsed through every publication for which there was any likelihood that the issue of illicit antiquities would be addressed. This means that I have looked at publications on overarching conservation issues (these are works that often contain words such as “principles,” “method,” and “methodology” in the title), publications on the conservation of metals, glass, and pottery (since archaeological objects are frequently made of these materials and, hence, the illicit antiquities trade could have been seen as relevant by the authors of such books), publications on the cleaning of objects (since such publications could address topics such as the problem of removal of forensic evidence), and so on.

In the module descriptions in the programs, the reading was presented in different categories, such as “essential reading,” “recommended reading,” “background reading,” and “further reading.” The number and names of the categories differed between programs and modules. Presumably, students engage more with the “essential reading” than with the other categories, and, for reasons of space, I concentrate on the “essential reading” in what follows.

Results

The official curriculum on the illicit antiquities trade and conservators’ responsibilities

The results are found in Table 1 where all publications which contain anything on the topic illicit antiquities trade in the programs are presented. For each publication, I have also given the relevant page numbers where the topic is treated to give a rough indication of the extent of the coverage in each publication. The results suggest several observations. First, on a positive note, the topic “illicit antiquities trade” is not absent in the literature. Second, on a more negative note, there is not much information on it. In each of the three programs, the total amount of coverage consists of only a couple of pages. A third observation is that many of the textbooks used in the programs are not recent (and this observation does not only apply for the literature covering the illicit antiquities trade).Footnote 28 The publication dates for the textbooks in the programs span over the last three decades (the 1990s to the 2010s). This has bearing on the analysis of how the illicit antiquities trade and conservators’ involvement in the trade is covered since, as noted earlier, it is an area where there has been considerable development over the years.

Table 1. Publications that contain anything on the topic of illicit antiquities trade in conservation programs

A fourth observation is that none of the publications that have appeared in the last two decades dealing specifically with conservators’ relation to the antiquities trade and basing the discussion on specific cases (such as Balachandran’s “Edge of an Ethical Dilemma”; Tubb’s “Irreconcilable Differences?”; or Brodie’s “Role of Conservators”) are found on the lists.Footnote 29 Looking at Program A and B, the amount of coverage of the illicit trade – apart from the paragraphs in the American Institute for Conservation’s (AIC) Guidelines for Practice and the ICON Code of Conduct in Program A and a brief mention (four sentences) in Barbara Appelbaum’s Conservation Treatment Methodology in Program B – consists of what is found in Chris Caple’s Conservation Skills. Footnote 30 Caple has a one-page section entitled “Stolen or Looted Objects” in a chapter headed “Responsibilities.”Footnote 31 The illicit antiquities trade is also treated in a section on legislation.Footnote 32 In Program D – apart from the paragraphs in the AIC Guidelines for Practice – the illicit trade is covered in Catherine Sease’s “Codes of Ethics for Conservation.”Footnote 33

Beginning with Program A and B, the pages in Caple’s Conservation Skills quite possibly represent the total, or near total, of what students read about the illicit antiquities trade during their three-year education. It is thus worthwhile to take a closer look at what they communicate. Caple outlines two reactions to a situation when conservators are faced with offers to treat objects “of dubious provenance.” Conservators may choose to work on such objects since this ensures at least that they will be appropriately documented and recorded. Alternatively, conservators may refuse treating such objects since this denies “perpetrators or collaborators in the crime” the increase in price that a well-conserved object would give them. According to Caple, both arguments can be seen as “naïve and idealistic,” and he notes that it can be hard to refuse to treat an object in need of care “particularly as it provides the conservator with much needed employment.” He does not explicate what a “dubious” provenance is or what provenance information should be requested before undertaking a conservation commission, but, elsewhere, Caple states that owners should “provide basic information about the object which may include some proof of ownership.”Footnote 34

In sum, Caple’s presentation comes down to that there are arguments both for and against working on objects of questionable origin and that, while he obliges owners to present “basic information” about the object, the cautious and imprecise wording used does not signal that rigorous provenance checks need to be undertaken. Caple’s account may be seen as a diplomatic overview of the divided opinions there were in the profession about the question of conservators’ relation to the illicit trade around the year 2000. The question was then still relatively new on the agenda, and, as Caple also notes, the existing codes for conservators did not take a clear stand on the issue. At the time, the calls to refuse working on material believed to have been looted from archaeological sites were not received with unanimous approval within the conservation community. Influential conservators strongly disagreed.Footnote 35 Since the early 2000s, attitudes have changed, and a comparison between Caple’s wavering position with that taken in the ICON Code of Conduct from 2014 quoted earlier is illuminating. The Code does not ask the conservator to weigh the pros and cons of saving a possibly illicitly traded object versus aiding the illicit trade as such. Rather, the Code obliges the conservator to establish as far as possible that they are not working on an object of possible illicit origin. The Code also makes it plain that objects can only be treated under exceptional circumstances when where is an immediate danger of deterioration.

Program B also has Appelbaum’s Conservation Treatment Methodology as “essential reading” (and Appelbaum is “recommended reading” in Program A and D), but Appelbaum only devotes one paragraph to the “ethical dilemmas” posed by the “motivations of collectors” (which in her treatment includes private and institutional collectors but which does not mention dealers), and her conclusion that “current attention to ethical lapses in collecting (particularly smuggling!) is starting to affect conservators” is not very illuminating concerning how conservators should respond to requests to treat potentially illicit material. Her wording actually downplays the seriousness of the issue by calling smuggling an ethical lapse, not a criminal offence.Footnote 36

In Program D, the illicit antiquities trade is discussed in Sease’s “Codes of Ethics for Conservation,” an article, which relative to its length (17 pages) devotes a fair amount of space to the illicit antiquities trade.Footnote 37 Like Caple, Sease addresses the dilemma of the conservator being presented with an object that may have been looted (adding the circumstance that the object is “severely deteriorating” as a complicating factor). She notes that, if a conservator refuses to a treat the object, someone else will, with the risk that the object will not be properly treated and the treatment not adequately documented, exemplifying the case of the Kanakaria mosaic. This is similar to Caple’s argument in favor of accepting such commissions, but, in contrast to Caple, Sease also warns that the examination, treatment, and technical studies of objects could be (and are) used to authenticate and legitimize looted objects, referring to a technical report on the Sevso treasure by conservator Anna Bennett.Footnote 38 Sease presents other arguments against treating possibly looted objects, including that such treatment may destroy forensic evidence. Unlike Caple’s balancing of the positives and negatives of treating objects of questionable origin, Sease’s text, while not taking an explicit stance, strongly suggests that the negatives outweigh the positives.

So what do these results reveal about what can be learned about the illicit antiquities trade and conservators’ relation to the trade from the literature in the three programs? One may note some important omissions. The first omission is any mention of the possible legal consequences for conservators who undertake work on possibly illicit material. For example, it would certainly have been useful if Caple’s calculation of the pros and cons of treating such objects had explicated that conservators who treat them might risk a prison sentence (hardly an irrelevant factor). This omission is not surprising – and not a fault of Caple’s – given that, as mentioned, the possibility that a conservator might be charged for undertaking conservation work was not on the agenda at the time that Caple was writing. The topic was first brought up in the literature from the 2000s and in more detail in still later literature.Footnote 39

A second omission is any discussion of what responsibilities conservators have when coming into contact with people collecting unprovenanced objects, not only in regard to abstaining from treating such objects but also in regard to informing these people about the negative consequences of their collecting. Again, this is hardly surprising since this question was only brought up by Balachandran in 2007.

The third omission is an important silence in Caple’s Conservation Skills: it says very little about how the trade functions; how objects are laundered in different ways by being equipped with fake provenances (yet again, this is no surprise: bogus provenances received less attention in the early literature); how seemingly reputable dealers and auction houses sell loot; how seemingly reputable research institutes authenticate loot; and how seemingly reputable museums acquire loot. Sease’s account strikes a different tone concerning “reputable” market players and academic collusion. She names both an auction house (Christie’s) as a sales place for figurines looted in Mali and the involvement of the Oxford University’s Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art in authenticating Malian figurines and legitimizing the trade.Footnote 40 In Caple’s account, the information is mainly directed at the privately employed conservator, and, whereas he provides some arguments against treating illicit material (as well as some for it), his reasoning is hard to apply in practice without any indication of how to tell illicit from licit objects in the first place. Without any such information, or a warning against the seemingly reputable sources, it might be all too easy to assume that all material is licit unless there is something particularly suspect about it. Further, from Caple’s treatment, which leaves out the many ways in which the trade may be legitimized by institutions and individuals, it might be equally easy to assume that ethics in relation to the trade only concerns privately employed conservators and the question of whether or not to undertake commissions for the trade.

Obviously, learning does not only occur through literature, and how students engage with literature depends on how the readings are related to other learning activities. From Program D, I also received information on lectures, seminars, and assignments. A module theme on ethics included an introductory lecture on heritage legislation, mentioning the 1970 UNESCO Convention, and an in-class activity on codes of ethics.Footnote 41 The provided readings were Sease’s “Codes of Ethics for Conservation” and the AIC Guidelines for Practice, which the students were instructed to read before class. The in-class activity required active student participation, which suggests that many students study the readings attentively. Another module contained a further lecture on cultural heritage legislation, covering the UNESCO Convention, looting in Syria, and some recent smuggling cases (but, noteworthily, not the involvement of auction houses, museums, or conservators).

As already mentioned, for Programs A and B, I received no information on lectures, seminars, and assignments. Possibly, the curricula of these programs put more emphasis on looting, illicit antiquities trade, and professional involvement in the trade than the reading lists suggest, but they could equally well put less emphasis on these issues if, for example, the learning activities and reading instructions related to Caple’s Conservation Skills (which is over 200 pages and covers a range of topics) turn student attention to other aspects of the book’s content.

A hidden curriculum legitimizing treating undocumented archaeological objects and whitewashing their origins?

As noted in the introduction, education has “side effects” beyond the intended ones. When going through the literature, I observed that, in two textbooks used in Programs A and B (they were “essential reading” in Program A and “recommended reading” in Program B), various conservation treatments were exemplified with conservation work undertaken on archaeological objects lacking a secure provenance. The two books were Susan Buys and Victoria Oakley’s The Conservation and Restoration of Ceramics, first published in 1993,Footnote 42 and David Scott’s Copper and Bronze in Art: Corrosion, Colorants, Conservation from 2002.Footnote 43 Interestingly and quite ironically, in Buys and Oakley’s text, an unprovenanced archaeological object appears in a subchapter headed “Ethical Considerations.”Footnote 44 The object in question is a krater by Euphronios, depicting Herakles fight against Kyknos. Following its purchase by private collector Nelson Bunker Hunt in 1979, the krater was restored by Zdravko Barov. The restoration of the vase, of which only 25 percent of the original was preserved, involved the reconstruction of the whole shape of the vase, and the case is included in Buys and Oakley’s text to illustrate when it is ethically justifiable and desirable to restore an object to make the viewer appreciate its aesthetic impact. That is, the ethical topic raised by Buys and Oakley concerns restoration and reconstruction, not the ethics of treating and increasing the market value of objects of questionable origin.Footnote 45 The Kyknos krater was purchased by Hunt from dealer Bruce McNall, who had acquired it from Robert Hecht. It is thought to belong to the group of Euphronios vases looted at Cerveteri around 1970, and it is one of the over 250 objects that have been returned from American private and public collections to Italy.Footnote 46

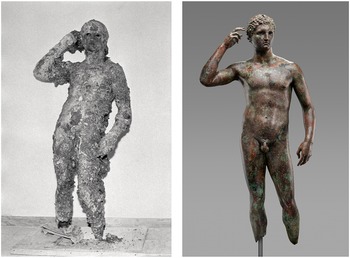

The reader of Scott’s book encounters a parade of unprovenanced, and, hence, likely recently looted, archaeological objects, one of them even before opening the book. Sprawling across the front and back cover is the image of an ancient Greek bronze statuette of a dead youth. On the frontispiece are two photos of a Roman bronze bust of a woman, shown before and after the removal of encrustations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Roman miniature portrait bust, ca. 25 BC – 25 CE, bronze, glass-paste, 16.5 x 6.7 centimeters in the J. Paul Getty Museum, before and after conservation. (courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum).

The photos of the bust reappear again in the book,Footnote 47 and, on the facing page, there are a pair of photos of an ancient Greek bronze statue of a Victorious Youth, also shown before and after the conservation that removed corrosion, sediment, and marine organisms (the statue had been found in the sea) (see Figure 3).Footnote 48 These and other objects featured in the book were purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum, mostly in the 1980s, and generally are lacking provenance.Footnote 49 The book also includes unprovenanced archaeological objects in other museums (the Ashmolean and the Miho Museum) and two that are in (anonymous) private collections. Actually, the majority of the archaeological objects featured in the book lack provenance, and several of them were treated by the book’s author, David Scott. The messages conveyed about provenance issues are – at best – contradictory. There is a lengthy discussion of how Scott’s examination of four Roman statues that “came on the art market in 1984” suggest that “all of them were buried in the same environment,” but there is no explanation given why these statues are no longer “buried” and why their findspot is unknown and how and why they “came” on the market (through an undisclosed dealer).Footnote 50 Alternative wording – such as “dug up by looters at the same place” and “bought from the dealer Robin Symes” would have been more precise.

Figure 3. Greek statue of Victorious Youth, ca. 300 BC, bronze with inlaid copper, 151.5 × 70 × 27.9 centimeters, in the J. Paul Getty Museum, before and after conservation (courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum).

A reader of these two publications by prominent conservators and conservation scientists may get the impression that it is perfectly normal for objects to appear on the market with heavy encrustations and no provenance (in the books, Oakley and Buys are titled head and respective former head of Glass and Ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Scott is presented as senior scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute and head of its Museum Research Laboratory; he has since become a distinguished professor in the Department of Art History at the University of California Los Angeles) and that it is perfectly normal for museums (and anonymous private owners) to acquire such objects and wholly unproblematic for conservators to treat them. The reader may also think that ethics in conservation is solely about the amount of reconstruction and restoration that can be undertaken.

These books are certainly excellent tools for learning the methods of conserving ceramics and metals, but while learning these methods, the reader may also be taught negligence concerning whether to undertake such treatment in the first place.Footnote 51 Further, the normative influence that is exercised extends to such seemingly mundane and innocent aspects as to which perspectives and words to deploy (for example, “buried” rather than “looted”) when writing about an object’s modern history. To paraphrase the answers in Tubb’s study, these publications might suggest that ownership issues should be left to others.Footnote 52 Scott’s Copper and Bronze in Art and Buys and Oakley’s Conservation and Restoration of Ceramics remind us that a range of factors and influences contribute to the curriculum and that these may amplify both intended and unintended learning outcomes, one of the latter possibly being a “normalizing” of the treatment of unprovenanced objects and of certain ways of representing these objects’ biographies.Footnote 53 Presumably, the risk of this potential educational side effect runs higher if questions about professional involvement in the antiquities trade are not adequately addressed in a curriculum.

Discussion

The investigation found that the literature in the three programs addressed the topic of illicit antiquities trade and of academic participation in this trade but that the coverage was not extensive and partly outdated. In particular, there was nothing on the possible legal repercussions of undertaking conservation work on objects of questionable origin. In Programs A and B, Caple’s indecisive position on treating undocumented objects is out of alignment with current ethical guidelines.Footnote 54 One interesting – and unexpected – finding were the instances in the literature used in Programs A and B where unprovenanced archaeological objects appeared to illustrate exemplary conservation treatments and even exemplary conservation ethics.Footnote 55 It seems reasonable to propose that, at a bare minimum, teaching should provide students with a basic “literacy” of the culture of the trade so that, in their future careers, they can avoid becoming unwittingly involved in activities that support it.Footnote 56 This means that teaching needs to communicate that what might look beyond reproach need not be so and that an association with allegedly reputable dealers, auction houses, museums, or academics is certainly no guarantee that the object has not been trafficked. That provenances and export documents are frequently forged is also part of the basic know-how, as is knowledge of the diverse forms of which academic involvement in the trade may be constituted. For Programs A and B, it is doubtful whether this minimum requirement of market literacy was met.

It is, of course, always easy to argue that there should be “more” about a particular subject in a program. It can be countered that there is an upper limit to the amount of content that can be put into it. Programs may suffer from congestion by trying to cover too much, and adding more content involves the risk of creating shallow, rather than in-depth, learning.Footnote 57 Still, in terms of literature, adding, say, two articles would go a long way toward giving students basic insights into the complexities surrounding conservators’ ethical and legal obligations in relation to the trade.Footnote 58 It would not teach them all there is to know about the subject, but it would hopefully create an awareness of when they need to seek out more information. Of course, learners benefit from actively processing and reflecting on content rather than from being passive recipients of it. Thus, ideally, the issues concerning antiquities trafficking and professional involvement should not only be covered in literature or lectures but also in assignments or seminars requiring active participation. In this respect, Program D, where Sease’s “Codes of Ethics for Conservation” was reading for an in-class activity, is exemplary.Footnote 59

As said, textbooks like Scott’s Copper and Bronze in Art might contribute to a hidden curriculum that imparts a sense that it is legitimate to work on unprovenanced archaeological objects.Footnote 60 This does not mean that this kind of literature should be censored or removed from reading lists. A hidden curriculum needs to be exposed, visualized, and problematized.Footnote 61 Used in the right way, Scott’s text – and Caple’s Conservation Skills for that matter – do have didactic potential as time capsules, and they offer excellent reference points for ethical discussion.Footnote 62 Precisely because these books represent outdated (or hopefully outdated) positions and behavior, they may serve to illustrate how moralities have changed over the years. Not the least, these publications exemplify that all textbooks should be read with a critical eye.

If a bare minimum of teaching professional responsibility in relation to the market in illicit antiquities is to give students a basic understanding of the trade to avoid becoming a promotor of it, one may ask what might the goals of teaching be beyond that? To my mind, ideally, teaching should give students the knowledge and skills to work proactively to curb the illicit antiquities trade, wherever they end up being employed, be it in the private sector, museums, universities, research institutes or heritage management organizations.Footnote 63 This trade endures on a large scale for several reasons. There are gaps and shortfalls in current policymaking, in legislative and normative means of regulation, and so on.Footnote 64 On a more general level, the trade is entangled with a range of local and global social injustices and a neocolonial world order.Footnote 65 By and large, the countries from which the objects are sourced tend to have comparatively lower incomes than those where they are marketed and put on display.Footnote 66 The trade contributes to maintaining and reinforcing this unequal distribution of economic and cultural resources and capital. The trafficking of objects from the Global South to the Global North directs tourist streams and potential sources of tourist revenue from poorer to richer parts of the world – for example, from Koh Ker in Cambodia to Manhattan, New York.Footnote 67 It causes social harm in both the South and the North. Donations of loot to museums by wealthy collectors serve to enhance their social prestige and the entire class hierarchy, and these displays may wield significant epistemic power to define and grade objects and peoples.Footnote 68

The illicit trade in cultural objects should not be seen in isolation from a larger context of local and global power structures and the endurance of a colonial world order in relation to a neocolonial one. In relation to higher education, this means that the question of teaching about the illicit antiquities trade can be productively linked to discussions on the decolonizing (and de-neocolonizing) of the curriculum.

Decolonizing and de-neocolonizing museums and conservation

In what follows, I will lay out a vision of one aspect of what active resistance to the illicit trade in cultural objects might look like from the position of the museum-employed conservator (and also of other categories of museum staff). The resistance involves calling attention to the larger system of unequal power relations in which the trade thrives, and it relates to Nussbaum’s idea of viewing oneself as a citizen of the world.Footnote 69 From this perspective, ethics for a conservator working at a museum with collections of archaeological objects from around the world would then concern not only new acquisitions of unprovenanced, and likely looted and smuggled, objects (although this remains problem) but also how to address the legacy of all those unprovenanced archaeological objects acquired in the past decades remaining at the museum. Despite the impressive number of returns made in recent years of objects connected to Giacomo Medici, Robert Hecht, and other dealers, return remains the exception rather than the norm. For return to happen, a substantial amount of evidence is needed, and that evidence is generally not available. This means that many museums still hold, and display, large numbers of archaeological objects acquired, and presumably looted, post-1970, and these objects will likely remain at these museums. There is reason to ask how such objects could and should be dealt with and where conservator’s expertise may come into the picture.Footnote 70

There are now strong calls for the decolonizing of museums, and there is also an emerging literature on the decolonizing of conservation. This literature looks at present-day curation of cultural material from Indigenous populations in settler/invader states,Footnote 71 but the discussion on conservation science and its relation to colonialism could productively be extended to colonial relations more broadly. At first, conservation and colonialism may appear wholly unrelated topics, but, for instance, techniques developed for the removal of mural paintings were (and still are) employed to detach wall paintings in different parts of the world with the intent of sending them to “safety” in Europe and the United States.Footnote 72 Appreciation and appropriation, plunder and preservation have gone hand in hand.

The shift from colonial to neocolonial hegemony is a shift from direct political and military control to indirect economic control (although military invasion and proxy wars are still in the toolbox for domination). This shift is reflected in changing patterns in the flow of cultural objects from the Global South to the Global North. Westerners can now turn to the art market to obtain their desired art treasures rather than going on military or “scientific” expeditions themselves to detach or steal the objects. In Thurstan Shaw’s succinct formulation, “‘By right of wealth’ has now replaced ‘By right of conquest’: ‘Send a gunboat’ has been superseded by ‘Send a cheque.’”Footnote 73 Many ethnographic museums in the Global North with collections from Africa and Oceania now address the political and ideological colonial context in which their collections were acquired. In stark contrast, few art museums (or self-styled universal museums) with collections of statues, architectural members, and archaeological material from the Mediterranean, the Near East, Central and Southeastern Asia, and Latin America explicate the neocolonial context in which their more recent (post-1970) acquisitions were acquired. This context, apart from purchasing power, was built on a mindset that the laws of less powerful countries need not be respected.Footnote 74 In some cases, state collapse – and, in the wake of this, an abundant supply of loot on the market – can be directly linked to military interventions. It may certainly be asked which, or whose, perspective a museum adopts when it does not explicate how it has been possible to acquire quantities of objects from Afghanistan or Cambodia in recent decades. Speaking with Nussbaum, this neglect evidences both an inability to reflect on one’s own culture and of seeing the perspectives of others.

To visualize the destructive nature of the antiquities trade in museum exhibits (and online object presentations), conservators’ skills may have a crucial role to play. Conservators are perhaps the ones in museums who spend most time studying the objects, and they are in a unique position of discovering – and, then, either highlighting or obliterating – evidence of the objects’ origin. As mentioned, many objects bear physical evidence of their modern biographies in the form of breaks and tool marks. The absence or presence of old and recent restorations and mounts may be further signs of when objects were unearthed. Yet, like the stories of the objects’ acquisition, these stories are generally not told to museum audiences. But they can be: through the labelling, lighting, and positioning of objects (for example, by making it possible for visitors to see the back of stone reliefs where the drill marks usually are and by using lighting to show cracks). Literally and figuratively, an object can be seen from different perspectives.

Moreover, for those museums that have the fortune and privilege to possess loot from both the colonial era and more recent times, there is ample opportunity to visualize the shift from colonial to neocolonial hegemony. Paraphrasing Shaw in an exhibit context, nineteenth-century photos of white men on expeditions posing with objects may be juxtaposed with late twentieth-century sales bills from antiquities dealers. Clearly, old and new loot offer great, hitherto largely undeveloped, pedagogic possibilities for learning about colonialism and its legacies and endurances. Of course, engaging in serious decolonizing and de-neocolonizing internal and outreach work requires a critical mass of expertise among museum staff. Hence, the de-(neo)colonizing of museums is linked to the de-(neo)colonizing of the curricula for prospective museum workers, conservators included.

Concluding remarks

Academia has a tendency of studying down rather than up, and, in the field of illicit antiquities trade, the terms “capacity building” and “awareness raising” are generally meant for “others” rather than “selves.”Footnote 75 This study has sought to direct the gaze toward “us” and to open a discussion on how “we” teach at universities about the illicit antiquities trade and forms of academic involvement in it. Programs in conservation studies were examined to form a point of departure for such a discussion. The enquiry suggests some tentative conclusions and questions for further consideration that will hopefully be of relevance for teachers, students, and researchers when thinking about existing and prospective teaching (and prospective research on teaching) in a range of disciplines where professionals may come in contact with the ethical dilemmas and legal obligations posed by this trade.

First, it is not sufficient to ask if the topic of illicit antiquities trade and professional involvement is covered in a program or not. It is essential to examine how it is treated. A cursory examination might have suggested that Caple’s Conservation Skills provides a short but not inadequate coverage of the issues involved, whereas closer scrutiny reveals lacunas and shortfalls.Footnote 76 At worst, Caple’s text might create a false security as to the level of literacy of the trade gained. There is also reason to be mindful of those instances and situations where the absence of a discussion of the ethical (and legal) aspects of treating objects of questionable origin might influence students’ perception of these issues in ways that are out of tune with current ethical norms and the law. Such instances and situations may come from textbooks (for example, Scott’s Copper and Bronze in Art) or from (guest) lectures, as in the example referred to in the introduction, when students were assigned to treat material from a dealer vending unprovenanced archaeological material from a heavily looted part of the world.Footnote 77 As to various kinds of present-day entanglements between higher education and the antiquities trade, it may be noted that some collectors, with a track record of purchasing loot, sponsor degree programs in art, archaeology, and conservation studies.Footnote 78 This raises the question as to what influence such funding and connections might have on the official and hidden curriculum.

A second, related, conclusion is that it is relevant to ask what teaching about the illicit trade in cultural objects should aim for. This touches on broader issues about what abilities should be cultivated in training for future professionals engaging in the study, preservation, and representation of the past, and how these issues intersect with questions about how history and cultural heritage is constructed and used – by whom, for whom, and so on. The discussion on the conservation profession and its obligations in relation to dealing and collecting has mainly focused on the question whether privately employed conservators should accept or refuse to treat objects of undocumented origin. This focus might entail a sense that antiquities trafficking is a subject that concerns only a subset of the conservator community. In turn, this sense could contribute to the fact that this subject receives little coverage in the curricula (and that, as in Caple’s Conservation Skills, the coverage is narrowly focused).Footnote 79 However, as argued, there are more quandaries involved than saying yes or no to treat poorly provenanced objects, and the ethical and legal issues raised by the illicit antiquities trade do not only concern privately employed conservators. This is especially the case if one accepts that the ethical obligations that come with a unique expertise in examining objects do not only include a refusal to participate in the trade but also to actively discourage it and perhaps even to trouble the structures of injustice that drive it.

The third conclusion, as evidenced by the lack of recent literature on the illicit trade in the programs (and by that Program D asked me to suggest readings), is that there appears to be a need for venues for discussion and information sharing. Published research on the illicit antiquities trade is shattered among many journals and edited volumes,Footnote 80 and it is hardly surprising that Brodie’s “The Role of Conservators,” which appeared in the specialized journal Libyan Studies, had not made its way into the literature lists in the programs studied in this article.Footnote 81 Last, but not least, I would encourage further reflection on readings (stemming from my endeavor to compile a list of suggested readings for Program D): much of what is published has the research community as the primary audience, and there might be a need for the production of literature and learning materials targeted to students in different disciplines.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Magnus Berg, Neil Brodie, Mattias Bäckström, Christos Tsirogiannis, the two anonymous reviewers, and to the program and module leaders who provided material for this study. A special thanks to Kathryn Walker Tubb who has done so much to bring attention to conservators’ involvement in the illicit antiquities trade.