Introduction

Participatory action research (PAR) is an approach that promotes service user involvement as a means to improve research results and to bring about a positive change in the lives of the participants and their community (Borda, Reference Borda, Reason and Bradbury2006; Wright and Kongats, Reference Wright and Kongats2018; Abma et al., Reference Abma, Banks, Cook, Dias, Madsen, Springett and Wright2019). The goals of PAR can include rendering social services that meet the needs of their users or developing bottom-up initiatives for evaluation of local governance. We focus on participatory research with older people, a large group of users of social and health services (Walker, Reference Walker2007). Blair and Minkler (Reference Blair and Minkler2009) pointed out that within the field of social gerontology, PAR remains an underdeveloped domain. One of the reservations against involving older people in PAR is based on the assumption that the task is too elaborate for them to fulfil (Ray, Reference Ray, Bernard and Scharf2007). During the past decade a growing amount of empirical research has been carried out with older co-researchers (Backhouse et al., Reference Backhouse, Kenkmann, Lane, Penhale, Poland and Killett2016). The degree of their involvement varies significantly. Walker (Reference Walker2007) suggests that it fluctuates between consumerism and empowerment. Older people can be consulted to improve the recruitment of participants and provide feedback on instruments that are being used (Murray and Crummett, Reference Murray and Crummett2010; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Walford and Hockey2012; Bindels et al., Reference Bindels, Baur, Cox, Heijing and Abma2014), or they can have control as co-researchers throughout the entire research cycle (Barnes, Reference Barnes2005; Woelders and Abma, Reference Woelders and Abma2019). Both extremes of this spectrum can raise problems. Hampered participation points at an attempt to control or misuse involvement (Vera-Sanso et al., Reference Vera-Sanso, Barrientos, Damodaran, Gilhooly, Goulding, Hennessy, Means, Newman, Olphert, Sandhu, Tew, Thompson, Victor, Walford and Walker2014), whereas increased professionalisation of participants resulting from their intensive involvement can also become an issue. Ives et al. (Reference Ives, Damery and Redwod2013) report critically on the ‘professionalisation paradox’ experienced by service users who have to follow training for their participation in research as laymen.

The degree to which older people can be involved in PAR depends on their wishes, capabilities and vulnerability due to old age. Recent studies demonstrate that vital older people can fulfil various tasks. Whether they can also represent frail older people remains unclear. Bindels et al. (Reference Bindels, Baur, Cox, Heijing and Abma2014) remark that their vital senior co-researchers were both willing and able to connect with some of their more frail peers (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Murray and Harrison2012). Additional research is required to understand how age-related vulnerability and frailty can affect an older person's involvement in research.

The availability of community services and provisions, such as public transportation that is affordable and scheduled to run during hours when older citizens generally make use of it, can also influence participation of older people. Both professionals and researchers should be prepared to adjust their way of working (Ward and Cahagan, Reference Ward, Cahagan, Barnes and Cotterell2012). Groot and Abma (Reference Groot, Abma, Banks and Brudon-Miller2019) report on a PAR project where a city councillor responded to the invitation of older co-researchers to answer their questions, and where researchers had to adjust their project planning and focus in order to meet the demands of their older research partners. Such adjustments are often time-consuming, since a new voice can destabilise the status quo and power hierarchy (Baur and Abma, Reference Baur, Abma, Goodyear, Barela, Jewiss and Usinger2014; Buffel, Reference Buffel2018; Woelders and Abma, Reference Woelders and Abma2019).

Reflection on power dynamics forms an intrinsic part of PAR (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR), 2013a). Sharing power, e.g. in cases when co-researchers define the research strategy, or when a substantial part of the funding is transferred to the co-researchers’ organisation (both examples refer to the project that will be described further on), is a prerequisite for the participatory process. Organisational impediments, e.g. when the timing or duration of the project is defined top-down, can hinder the PAR process.

The co-researchers are encouraged to inspire and facilitate the research process, based on their own experience, qualities and competence, whether or not they have an academic background or methodological expertise. Each of them should be able to speak her or his mind during the entire research process. The researcher is not, like in traditional research, in the lead or the unilateral decision maker. Certain tasks can be divided, but several structural tasks often remain with the researcher. This includes reporting to the funding organisation and financial accountability. Naturally, the researcher's professional curiosity can influence the direction in which the co-creation process of the team will progress, but power relationships are not pre-defined; they remain subject to discussion, negotiation and group decisions (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Kenny and Dickson-Swift2018; Groot and Abma, Reference Groot, Abma, Banks and Brudon-Miller2019).

The conditions for interaction play an important role in PAR. Data are co-created in communicative spaces (Habermas, Reference Habermas1978), which are purposefully arranged by researchers. In such spaces the participants feel safe, open towards transformational learning and stimulated towards creativity. Transformational learning is based on ‘mutual recognition’, ‘reciprocal perspective taking’ and a ‘shared willingness to learn from each other’ (Abma et al., Reference Abma, Groot and Widdershoven2019: 130). It can result in interaction by means of inclusive dialogue, reconsideration of responsibilities and assuming a new role within the community. The insights that are co-created during this process can form a basis for transformational change, which is an aim of PAR (ICPHR, 2013a). The researcher's role is to provide tailor-made support to the co-researchers, taking into account their different backgrounds, expertise and expectations. A major transformation is not necessarily required; small but meaningful steps in learning, reflection, action and impact are valuable (Boelsma et al., Reference Boelsma, Baur, Woelders and Abma2014). The participatory research process is rarely linear and cannot be planned upfront (ICPHR, 2020). Usually it is a cyclical iterative process, a ‘journey’ from which changes can emerge. As Wadsworth (Reference Wadsworth1998: 7) writes: ‘Change does not happen at “the end” – it happens throughout’.

In research, engagement of older people can have a positive impact on their individual empowerment or on the communities to which they belong (Baur and Abma, Reference Baur and Abma2012; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2012; Tanner, Reference Tanner2012). PAR claims to make a difference, but overall evidence regarding its impact remains limited (Fudge et al., Reference Fudge, Wolfe and Mckevitt2007; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Boote, Buckley, Vougioukalou and Wright2017). This can be because many PAR projects are small and local, and they do not find their way into academic publications. Moreover, the types of impact that PAR can have are not always explicit. According to Cook et al. (Reference Cook, Boote, Buckley, Vougioukalou and Wright2017), not all change is measurable; a positive or awkward interaction can have a strong impact on people individually or the entire group. In a recent systematic review, Baldwin et al. (Reference Baldwin, Napier, Neville and Wright-St Clair2018) report that evidence of the impact is mixed, but the benefits of involvement seem to outweigh the challenges. We support their suggestion to embed evaluation in the iterative process of participatory research, in order to capture the meaning it has for the persons who are involved.

Impact is understood in relation to transformational change that occurs in the process and after PAR: ‘In participatory research change is usually recognised as the contribution that research makes to the people involved in the research and the communities and organisations they are part of, although change on the wider society, policymaking and the academy may also occur’ (Abma et al., Reference Abma, Banks, Cook, Dias, Madsen, Springett and Wright2019: 101). Impact is a transformational force from social learning (ICPHR, 2013a) to collective action, which brings about a change in the way the participants see the world around them and act in it.

In this article we describe impacts of PAR during the entire research process of a recently conducted project with older people as co-researchers. Impact took place at a personal, interpersonal and community level, in circles that enhanced each other, consecutively and at the same time. This makes a separate description of each level provisional. Our research question is:

• Which types of impact can a community-embedded PAR project have on its older participants and how can these impacts spread and be enhanced during and after the research process?

Design

Research setting

The Dutch province Zeeland is a sparsely populated area; 23 per cent of the inhabitants are older adults (65+), 34 per cent of whom are 80 or older (CBS, 2019). These are the highest percentages of older inhabitants in the country. General practitioners in Zeeland are on average older than in the rest of the Netherlands and one-third of them has a solo practice. Consequently, when they retire their practices will most probably be closed, leaving the population without sufficient first-line health-care provision (Commissie Toekomstige zorg Zeeland, 2015). Zeeland has various regional dialects and is characterised by a broad scale of cultural differences. Initially Zeeland was comprised of a large number of small islands. To date, the sense of unity within the province is quite weak. This and mobility issues have led to communication barriers within the region.

Background

In 2016, a representative of a foundation called Festival of Recognition (FoR) contacted the Department of Medical Humanities of the Amsterdam University Medical Centre. FoR was a successful voluntary organisation that counted about 50 volunteers, most of whom were 60 and older. FoR's core activity was to organise reminiscence sessions for people with dementia living in medical institutions, with the use of ‘travel bags’. ‘Travel bag’ is a figurative term and refers to a set of old-fashioned artefacts that are thematically arranged by volunteers. In short, FoR focuses on what in the academic literature is called reminiscence work, a well-established field of research and intervention, that is often used in the work with older people to stimulate their memories and interaction (Westerhof et al. Reference Westerhof, Bohlmeijer and Webster2010; Gibson, Reference Gibson2011). The initiative started in co-operation with local museums in Zeeland which lent artefacts from their collections. Other artefacts were donated by volunteers or bought at local flea markets or in antique shops. Examples of themes are ‘On the beach’, ‘In the shop’ and ‘School’. Each bag is filled with traditional paraphernalia matching the topic. All sessions take place on the premises of nursing homes. ‘Travel bags’ are kept, updated and circulated by the volunteers. FoR presents its sessions either free of charge or against a low fee that covers the travel expenses and the purchase of new artefacts; FoR does not have premises of its own.

The reasons for FoR to initiate the contact were twofold: firstly, the department has expertise in the field of reminiscence work (Bendien et al., Reference Bendien, Brown, Reavey, Domenech and Schillmeier2010; Bendien, Reference Bendien2012, Reference Bendien, Swinnen and Schweda2015). Secondly, after five years of success, FoR wanted to extend its activities towards community-dwelling older people. That decision was based on the moral appeal felt by volunteers to also help older people who have limited social contact. FoR's request to the researchers was to help them find a way in which reminiscence sessions could be held with community-dwelling older people. FoR had people in mind who were 65 or older, living alone, possibly in the early stages of dementia and not (very) mobile due to their age.

Until the initial meeting FoR had not been aware of the principles of PAR. The researchers’ suggestion to use PAR was based on three considerations. Firstly, active participation of older volunteers was a case from the very beginning of the project; after all, the idea had been developed bottom-up and presented to the researchers, not the other way around. Secondly, one of FoR's strategic goals was to become less dependent on charity funding. The researchers’ input would be temporary only, therefore PAR, with its transformational learning, appeared to be a functional approach. Thirdly, the researchers had both expertise and experience with community-based projects conducted together with older adults.

The Board of FoR accepted the suggestion to use PAR. One researcher would be permanently involved in the project, whereas two colleagues would be on standby. During the preparation phase the researcher explained the methodological design of the project to the FoR volunteers who considered becoming its co-researchers.

PAR team

PAR allowed for a continuous fine-tuning of the priorities between FoR, the co-researchers and the community-dwelling older people, during the entire project.

The initiator of the contact, SusanFootnote 1 (67), became one of the project leaders. She recruited volunteers who showed interest in becoming co-researchers for 16 months, from July 2017 till November 2018. Susan's leadership came naturally, due to her role as FoR's founder. She had been actively involved in the preparation of the project application and co-ordinated the recruiting of the project team members after the financing had been granted. The invitation to become co-researchers was published in the FoR newsletter that was sent to all its volunteers. The description of the project did not contain any references to PAR, since Susan herself was not yet familiar with it. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were defined. However, applicants who had no personal means of transport were promised personal transportation; he or she would be picked up by another member of the project team.

The team-building process that subsequently took place is described in the Results section. The team consisted of one researcher and seven co-researchers. These were all women, aged 54–85, mean age 67, whereas the researcher was 54. Of the co-researchers, five considered themselves to be in good health, one (85) was explicit about her ‘vulnerable’ age and the last one (74) pointed out that she had frail health. Initially, only Susan knew the co-researchers personally. At first the meetings were rather formal. After experimenting for two months how the meetings should be conducted in order to be efficient and also inclusive for each team member, it was agreed to ‘make a round’ for each of the agenda points. That meant that each member of the team was given the opportunity to voice her opinion on each subject that was being discussed. Some exceptions to this rule will be presented in the Results section. The process of deliberating and deciding about all project issues together led to long discussions. This was time-consuming, but the results were carried by all team members. By the end of the project the team had become a productive unit with good personal relationships. The impact of this interaction and mutual learning process will be presented in the next section. During the entire project the researcher provided individual coaching support to each member of the team. Additionally, the funding organisation arranged for a series of workshops for the co-researchers on topics such as ‘Communication with local authorities’.

Analysis

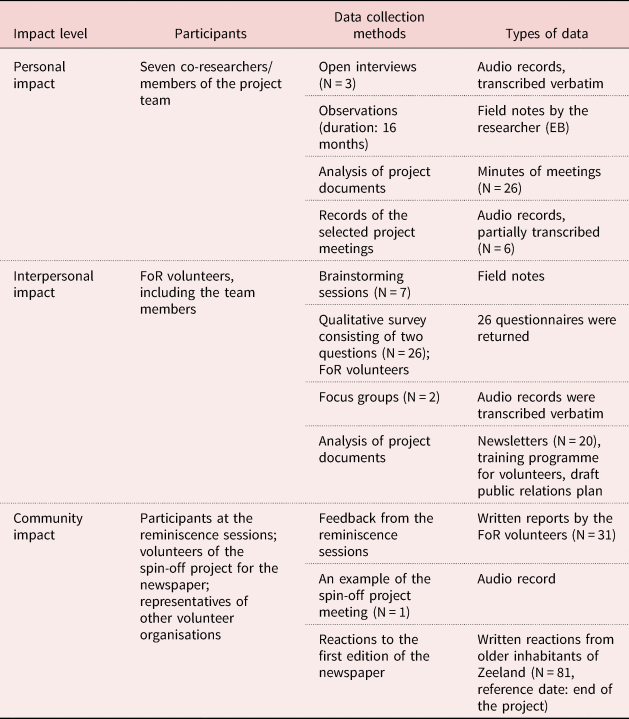

The project team assessed the impact of its activities at three different levels, using various methods of data collection. An overview of those is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Impact levels and methods of data collection

Note: FoR: Festival of Recognition.

Except for personal interviews and the audio records of the meetings, all data were discussed and analysed by the entire team. None of the co-researchers had previous experience using academic methods of analysis, so they focused on open discussions about specific datasets. The team used an iterative process for analysis as follows: the researcher made notes of the ideas that the co-researchers came up with and fed the outcome back to the team for validation. For instance, all suggestions on how to get in touch with community-dwelling older people were collected using questionnaires, transcripts of brainstorming sessions and minutes of team meetings. The raw data were made available to each of the team members. The researcher arranged for training for the team members, but part of the data analysis, specifically content analysis, turned out to be too theoretical for the co-researchers, who preferred to concentrate on more practical matters. Hence, the researcher summarised the findings in work documents that were used as a basis for discussion. Only after the entire team had agreed on the results of the analysis was the next step in the project progress made. To ascertain the validity of the accounts, the results of the questionnaire, the reports of the focus group meetings and the reports of the reminiscence sessions were all subjected to member checks from the participants. During the entire project, the intermediate results that the project team had achieved were shared with all the FoR volunteers in a monthly newsletter that had been edited by one of the team members. The content of the newsletters was prepared by the team, together with FoR volunteers.

To ensure the quality of the research, the team applied the quality criteria for PAR (ICPHR, 2017) and the ethical criteria as formulated by the ICPHR (2013b). Each team member formally consented to participate in the research project and also to the use of project records in publications. Two team members read and commented on the draft of this article. The progress and results of the project are described in full detail in the Dutch project report (Bendien, Reference Bendien2018).

Results

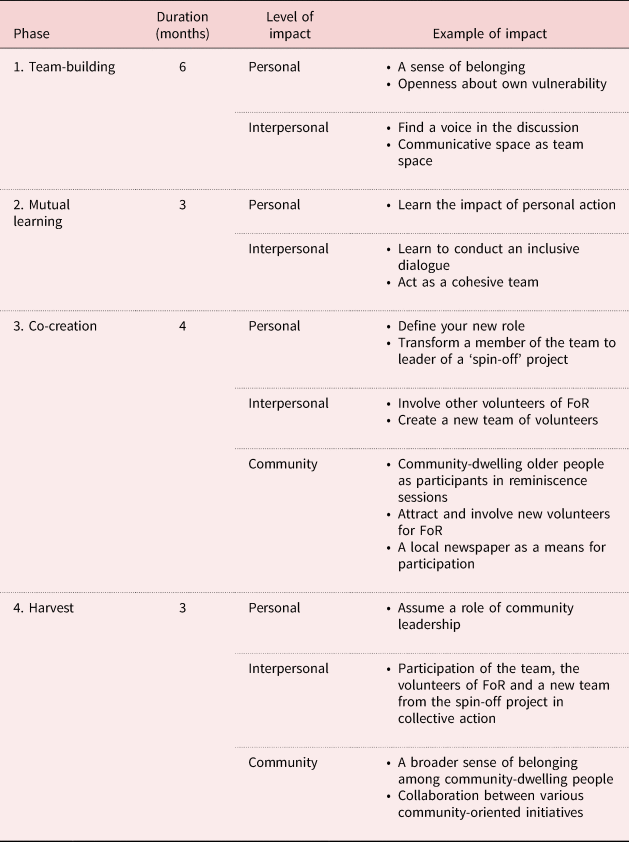

The following narrative account presents the four stages and action–reflection cycles of the project, as summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Stages and action;reflection cycles of the project

Note: FoR: Festival of Recognition.

First stage: team-building

The team-building process took six months. Initially, ten volunteers showed interest in the project, but five of them left. Three women left within a month because of informal care duties or health problems. Two men left the project after two and four months, respectively, because they felt that they could not conform to the principles of PAR. Two months after the start of the project two new women volunteers joined the group. The volunteers received an allowance in accordance with the Dutch rules for the reimbursement of voluntary work.

The team came together twice a month. In consultation with the rest of the FoR volunteers, two questions were formulated: (a) How can community-dwelling older people be invited to reminiscence sessions? and (b) Is it possible to recruit more volunteers for FoR? The organisation that funded the project also had a request, i.e. to demonstrate the added value of PAR with older co-researchers. The team did not object to it, but in first instance they coined it ‘Elena's task’ (first author). That was the first sign regarding ownership that the team showed in the course of the project. Apart from that, they preferred to call themselves project team members and not co-researchers.

To find ways to reach community-dwelling older people, the team sent a simple qualitative questionnaire to all FoR volunteers (N = 40). It contained two questions: (a) Which community-based organisations can we contact in order to promote the activities of FoR? and (b) Are you prepared to promote our activities yourself? The reactions (N = 26) to the first question were mainly about personal networks, church communities, sports clubs, etc. The replies to the second question were reserved, fluctuating between ‘I shall try’ and ‘I think it's a noble goal, but I don't feel at ease going out and pushing other people’. Based on those reactions, the team decided on two strategies: (a) use all the FoR networks to distribute invitations and (b) establish new contacts with professional organisations that are involved with community-dwelling older people. Both strategies were tried out, but without much success. Conversations with local networks did ignite some interest, but the response to individual invitations was low. The constraints of cultural differences between the sparsely populated areas, where different dialects are spoken, played a role.

In parallel, the team contacted several professional organisations that were working with older people living at home. Five of them indicated that they found the proposal appealing, but because of the privacy law contact details of individual persons could not be shared. An attempt to distribute invitations through their staff failed utterly. Despite everybody's good intentions, the message was not properly understood or did not come across at all. For example, one of the FoR volunteers received contact details of an older man who wanted to play billiards, but was not at all interested in the reminiscence sessions. There was a spark of hope when contact was made with a large welfare organisation that appeared to be eager to co-operate. However, after several months the team received a friendly message that the organisation in question had other priorities to address. The team discussed the situation at length and concluded that the messages that FoR was trying to convey were not clear enough and that health-care personnel who are not familiar with FoR should not be its ambassadors. Six months after the project had started, FoR found itself unable to reach community-dwelling older people in a structured manner. As a small organisation, run by volunteers only, FoR did not have financial or professional means at its disposal to advertise broadly about the reminiscence sessions. The local municipalities stated bluntly that small local initiatives such as FoR had to find their way to deal with promotional activities. The gap between the professional institutions and FoR as a volunteer organisation seemed to be unbridgeable, even though they were operating in the same field and with the same target group.

Reflection on the impact of PAR

Personal impact

The analysis of the recruitment process demonstrates that participation as a co-researcher can boost a person's self-confidence, but can also be experienced as an effort-consuming activity. Team member Elisabeth (74) had recently lost her husband and was still in mourning. Her decision to join PAR helped her to keep herself busy and dispel the emptiness that the loss of her husband had created. PAR was attractive to her because it allowed for openness in the team to speak about loneliness and vulnerability. Elisabeth's frail health was a common concern to the team, but she did not experience that as a barrier against taking part in the project. On the contrary, her sense of belonging was strengthened by her involvement, because she could talk about her experiences:

My husband died in 2014, and in 2015 I faced all that disaster [illness] alone. There was no place to tell your story. And yes, I've learnt to live with it, but if you say ‘vulnerable’, then yes, I am very vulnerable.

Interpersonal impact

At the start of the project the team-building process was challenging. The ‘chaotic’ meetings, during which the team members were supposed to get to know each other and to make a plan of action did not match everybody's expectations. In particular, two older men who had joined the team from the start had problems with PAR. Both used to work in managerial positions. Both explicitly worded their preference for a top-down approach with a formulated goal and time-planning fixed in advance. The messiness of the first meetings, that can well have been caused by what Cook (Reference Cook2009: 281) called deconstruction of ‘well-rehearsed notions of practice and aspects of old beliefs’, was not how they imagined the project should be carried out.

The other team members belonged to the ‘silent’ generation of hard-working women (Groot and Abma, Reference Groot, Abma, Wright and Kongats2018). They fulfilled their tasks as doers, simply getting things done and leaving the talking to somebody else. This difference in behaviour became obvious during the first meetings, after the group had agreed on the decision-making process. Each member would have a chance to voice her or his opinion on each of the issues raised. In practice, however, the initiative was being seized by one of the two men, leaving little or no room for the others to speak. In the beginning the other team members seemed to go along with this. They mostly kept silent and only became involved when tasks were divided.

Then one of the men left the team and two new women volunteers joined, which changed the group dynamics in a positive way. At this point the researcher decided to once again explain the basic principles of PAR. That proved to be a turning point. The team members suddenly realised what PAR stands for: power and decision making can be shared. Almost in chorus the women exclaimed: ‘Oh, I finally get it. We can decide ourselves what we are going to do.’ It had just taken a moment of quiet conversation to convey the message. Communicative space had been created for inclusive interaction, after which interpersonal impact also became possible. From then on each female team member started exploring new ideas. Whenever one of them wanted to say something, she would, with a wink at the researcher, start off by saying: ‘This is a participatory project, isn't it?’ Then she would pause to glance at the researcher as if looking for permission, and only then continue with what she wanted to say. It was as if they were still looking for confirmation that they were allowed to give their opinion. In fact, it indicated that the power imbalance was still in place.

PAR's democratic decision-making process slowed down the start-up phase of the project considerably. At first there was no consensus about how to proceed. Veronica (59) found it difficult to understand which new message FoR wanted to spread: ‘Do we want new volunteers or new groups of older people for our sessions?’ Two messages at the same time appeared to be too much to handle simultaneously. Having realised that helped the team to improve the quality of the research design and sharpen its focus. Also the tasks and responsibilities were not clear yet; each member of the team was looking for a new definition for their role.

To summarise, after a chaotic start, during which a few prospective co-researchers left and joined the team, respectively, a communicative space had been created and the core team emerged. Personal and interpersonal impacts of PAR had not noticeably enhanced each other or led to transformational change as yet, but ‘co-labour’ emerged, i.e. moving through distress, trouble and disappointment towards a new way of taking action (Cook, Reference Cook2009).

Second stage: mutual learning

That was the most challenging stage: it took about three months. Our aim was to make sure that community-dwelling older people would receive FoR invitations to reminiscence sessions. The team members themselves were experts-by-experience. They were convinced that the sessions would be received enthusiastically. Some of them had positive experiences with reminiscence sessions, others were inspired by enthusiastic reactions from people who accompanied persons with dementia or from community-dwelling older people, who occasionally also participated in those sessions. Yet, the team first had to deal with a collective feeling of disappointment and to start all over again. The team went back to the successful start of FoR as a voluntary organisation. In the course of several brainstorming sessions, the team pinpointed two conditions for success. Firstly, successful reminiscence sessions were always spatially and culturally localised. That had been quite a challenge, especially in sparsely populated areas, but by working closely together with local museums and nursing homes, FoR had been able to overcome that hurdle. Secondly, FoR's success so far had to a large extent been due to its network contacts with first-line care professionals, who had direct access to older people. The team decided to investigate whether attractive venues for reminiscence sessions, such as local museums or neighbourhood houses, could make a difference, especially if the invitations were distributed via professionals whom the community-dwelling older people already knew and trusted. A new course of action was set.

Reflection on the impact

Personal impact

The second project phase was characterised by a mutual learning process, which had an impact at both the personal and the team level. Martha's initiative was an inspiration for the entire team. Martha was 85 when she joined the project team. Initially, she kept quiet during meetings, because FoR was new to her and she was sceptical about ‘all that fuss about loneliness’. It took Martha a couple of months before she literally found her voice in the group. She used her expert-by-experience position to tell us what ‘the real frail older people’ thought of the societal ‘ado’ about loneliness. She went to all the available lectures and workshops where that topic was discussed, until she told us one day:

I'm sick and tired of listening to all those people. Nobody does anything; they all just keep talking. I live in an apartment building where 90 per cent of the people appear to be lonely, especially during the holidays. I am sick and tired of waiting. Christmas is coming soon. I've just placed an advertisement in the KBO [Catholic Union for Older People] newspaper ‘Are you too alone during Christmas?’ I invited every neighbour to come over for a piece of cake on Christmas Day.

On 25 December 2017, Martha had 11 visitors, each of them neighbours who had responded to her invitation.

Interpersonal impact

Martha's ‘rebellious’ action created a new circle of impact by making the entire team aware of the impact that each of them could generate individually. Rose (66) and Elisabeth (74) became actively involved in the co-ordination of FoR activities, while in another region, Katrine (65) initiated contacts with several voluntary organisations to promote the reminiscence sessions. The impact that PAR had on each of them had changed the way they interacted with each other. The project group meetings had shown that inclusive dialogue had to be learnt and reflected upon before it could become an intrinsic part of group interaction. After the team members had realised that their personal opinion counted, the meetings became chaotic again, albeit in a different way than at the start. Everybody had an experience to share; there were meetings when there was not even time left for the issues on the agenda.

The first meeting that took place after the Christmas break was representative of that stage. Everybody was glad to see each other again, but nobody was listening. The researcher was being interrupted the same way as anybody else. At some point, she reacted to an interruption by asking the group to let her finish her sentence. She thought she had asked it in a friendly manner, but suddenly everybody kept completely quiet, just like they used to at the beginning of the project. After the meeting Susan, the FoR team leader, explained:

Don't feel offended, we all have so much to tell, and we haven't seen each other for weeks. We still have to learn to listen to each other.

Elena's concern, however, was not the chaotic way the meeting had been carried out, but the fragility of the personal and interpersonal impacts that the PAR project still had on the team members. Furthermore, the time element was becoming important, since the project duration was very short for a proper introduction of PAR.

As researchers, we learn that in PAR projects continuous transformational change usually requires more time than the duration of a project. In the course of a project small steps also matter. A couple of meetings later, Elisabeth (74) addressed the issue of group interaction point-blank:

I hear the same things again and again. That is not a good way of working together. Let's agree on some things to take them off the agenda.

This learning process was to continue throughout the project. The chaotic interaction had first of all to do with the newness to the team of a participatory approach. Secondly, with the need for the team members to overcome the difficulties of that project phase together and to learn from its ‘failures’. Finally, it had to do with the growing feeling of responsibility and realisation that different kinds of actions were required in order to get any further.

One major achievement during that stage was that the project group started acting as a cohesive team. By that time, it was the team members who, from time to time, chose to explain to Elena what it meant to conduct PAR. The circles of personal and interpersonal impacts enhanced each other, and as a result the tables had been turned whereby the ownership of the project had shifted to the local participants.

Third stage: creating room for creative solutions

The third stage was the turning point for the project. It took about four months and changed the team as well as the media landscape of Zeeland. Following its new course of action, the team found a way to squeeze FoR's invitations to reminiscence sessions through the tight system of privacy rules. Close co-operation throughout the province with a number of welfare professionals who were directly involved with community-dwelling older people was the answer to our question. Those key staff often were working in low- or middle-management functions for welfare or care organisations and they were directly responsible for the daily activities of their inhabitants. Their reaction to FoR's invitation stood in stark contrast to our previous experiences. They were not only enthusiastic, they also showed a hands-on mentality. They did not need time to think things over, the reminiscence sessions could be scheduled at once. Immediately after the first round of sessions, FoR received new requests. Additionally, the team started working with other voluntary organisations in Zeeland. As a result, the number of sessions as well as the number of people who wanted to join FoR as volunteers increased steeply.

One of the meetings took place in the Warenhuis Museum of Axel, where FoR, in co-operation with a volunteer organisation called ‘Sunflower’, received about 75 community-dwelling older people, most of them 70 or older. Many participants came supported by their walkers. When all the walkers had been ‘parked’, the museum aisles were more or less jammed. On that day, four sessions with reminiscence ‘travel bags’ were carried out in parallel by FoR volunteers. The collective process of remembering resulted in animated dialogues. One of the volunteers recollects:

The visitors had so many stories to tell that you had to watch carefully that everyone got a chance to talk. That afternoon was filled with feelings of solidarity and belonging. I felt so happy! These kinds of days have a golden touch.

The team was still pondering whether every effort had been made to spread their message throughout the province. Then, during one of the meetings, team member Jane (54) came up with the idea to launch a new provincial newspaper, compiled of archive articles and collective or personal reminiscences about Zeeland:

A free of charge newspaper, full of reminiscences, you know? I've seen one like that in The Hague. We shall use it to invite people to the reminiscence sessions. Isn't that a good idea?

The meeting agenda was forgotten and the project team focused on this new idea. Subsequently, a new separate project was initiated. It had a new team of volunteers, consisting of six older male journalists, archive professionals, designers and Jane herself. It took a mere five months to develop Jane's brainwave into the moment when the first copy of the newspaper, called Zeeuws Weerzien (‘See You Again, Zeeland’), was formally presented to the Executive Deputy of the Province. The newspaper project too was developed according to PAR; it was organised and carried out by Jane and her new team and supported at arm's length by the rest of the first team. The researcher followed that spin-off project as an observer only.

Reflection on the impact

Community impact

The third stage of the project has shown how interpersonal impact of a mutual learning process can spread and have an impact at the community level as well. The newspaper project gave a powerful boost to each member of the team and far beyond. The safe room for inclusive dialogue had been transformed into a room for co-creation. New ideas were being shared with the other team members, with the confidence that they would work together to implement them. Jane already had experience with public relations work, but now the scope of her organisational talent became explicit as well (personal impact). PAR had created a chain reaction, enhancing new developments and producing new circles of impact. Community impact of the new project emerged as a new creative space for the second team of volunteers, who in turn used their skills interactively (personal and interpersonal impacts) by creating the new provincial newspaper. A strong source of inspiration for the new team was the success of the many reminiscence sessions that FoR was already arranging throughout the province. The successful activities of the two projects had a strong impact on FoR's image with its new partners, i.e. the welfare professionals and the other voluntary organisations, as well as on the new participants of reminiscence sessions, i.e. community-dwelling older people.

Fourth stage: measurable and unmeasurable impacts

The fourth stage was the harvest phase. The response to the publicity was overwhelming. The headlines of the local press read: ‘Zeeland is enriched with an additional newspaper’, ‘Zeeuws Weerzien makes Zeeland more vital’. The personal reactions of the readers, often written by hand and sent to FoR by post, were enthusiastic and touching:

I work as a volunteer with people with dementia. Can I have several copies of your newspaper, so that I can use them in my work?

You've published an old photograph. The second girl on the left is my aunt!

Congratulations with the newspaper! … I look forward to receiving it. It is nice to write about the past, and I like the puzzles very much. I am 78. I live in a nursing home. I read and make puzzles a lot. The days seem so long sometimes.

During the following months, FoR was able to arrange additional reminiscence sessions, i.e. besides the sessions for people with dementia, for approximately 530 community-dwelling older people throughout the province. By the end of the project, FoR counted more than 100 volunteers, against approximately 50 at the start only 16 months earlier. The project was rounded off with a conference that hosted more than 170 local people, the majority of whom were older inhabitants of Zeeland. As to the moment for the project team to receive well-deserved congratulations, they decided to shift the emphasis of the closing conference and create a platform for other voluntary organisations who focused on community-dwelling older people. Six of them presented their activities, as well as FoR, and this turned the conference into a ‘festival of recognition’ for their collective input towards the wellbeing of older people in Zeeland.

Reflection on the impact

Community impact

The circles of impact of PAR during the fourth phase reached far beyond the personal development of the team members and their group interaction. The reminiscence sessions were arranged with the help of all FoR volunteers. They also distributed 50,000 copies of the newspaper. These are only two examples of collective action. We define collective action (Melucci, Reference Melucci1996) as conducted by a group that has its own identity and is driven by a societal challenge, such as a lack of social interaction among the community-dwelling older people, and inspired by the pursuit of a better future, based on inclusion of older people. The team members did not look upon the altruistic gesture they made during the end conference as something unusual, which in itself demonstrates the extent to which the group has come to understand the needs of their community. The team took responsibility for the future by sharing their knowledge with their new partners and the entire Zeeland community.

Personal impact (a new circle)

During the period the project was moving slowly, the team members kept searching for new ideas in emotionally charged discussions. Addressing their vulnerabilities was never an explicit aim of our work, but each of them came to that at some point. Martha (85) explained:

I have always done voluntary work, also when I was working. However, eventually, especially when you have passed 80, they think that you don't want to anymore, don't they? Or that you are not able to do it anymore. Anyway, they don't invite you any longer. And that is a pity. And then I heard about the Festival of Recognition and I thought, I could do that, and I am going to apply. Because I think that you also do it for yourself. It goes in both directions, doesn't it?

Susan (67) worded her feelings as follows:

I see how we all deny our vulnerability and the frailty of old age. But what I have also realised just now is that by saying yes to voluntary work you make the first step towards accepting the fact that you don't want to be ‘free’, to do nothing, to disengage. Doing voluntary work is a way to address your loneliness, and to address your potential vulnerability. Voluntary work goes both ways: you give but you also take.

Afterword

Today FoR is operating successfully in all the regions of Zeeland. Each of the PAR team members is still actively involved in various voluntary projects. Elisabeth (76 at the moment when this article was written) is doing voluntary work for FoR, but she is also actively involved in a voluntary project abroad. Veronica (61) is a co-ordinator for FoR, putting to use her excellent organisational skills. Katrine (67) has had two difficult years, fighting for her life, but is currently reclaiming her involvement as a FoR volunteer. Martha, who is 87 now, is still actively involved in her work for FoR. Jane (56) is the initiator and secretary of a new foundation, which at the time this article was written, was busy preparing the sixth edition of the by now famous ‘reminiscence’ newspaper. Rose (68) is the regional co-ordinator for FoR and also treasurer of the ‘See You Again, Zeeland’ foundation. Susan (69), FoR's ‘mother’, who initiated the entire FoR project from scratch and was the beating heart of this research project, is involved in several new initiatives and is open to new challenges. Since the end of the project, Susan, Jane and Martha each on different occasions received a Royal decoration for their voluntary work and outstanding contribution to the wellbeing of the older inhabitants of Zeeland.

Discussion and conclusion

The goal of our article was to describe various types of impact in the PAR project that was conducted by and for older adults. Our results are aimed to add to the critical discussion about types of impact that are usually overlooked in academic publications (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Boote, Buckley, Vougioukalou and Wright2017). We identify impacts as non-linear, sometimes implicit and reaching far beyond the initial goals. Taking our project as a case study, we identified three types of impact: personal, interpersonal and community. These impacts are interconnected and can be understood as an integral chain-reaction process, spreading in various circles that enhance each other.

Personal impact was revealed in the form of an increased sense of belonging between the individual team members, in their openness about personal insecurity and in the way they sought and found their own voices and assumed new roles within their community.

Intrapersonal impact was shaped throughout the mutual learning process and became evident on several occasions: when team meetings had turned into inclusive dialogues, when a personal action of a team member, Martha's Christmas party invitation, inspired collective action of the entire group, and when the researcher's position of authority shifted to the local team members, who then gave their meaning to the PAR principles. Such a power shift does not take place in every project, which can be explained by many reasons, e.g. pressure to deliver results or restrictions regarding financial accountability. Our team has come far by taking the responsibility for the project in its own hands, even though the researcher took over the reins at certain times, e.g. to submit an application for funding or to explain a methodological approach. Intrapersonal impact spread out to all the other FoR volunteers and prospective volunteers as well, thus creating a broad circle of impact.

The newspaper project, which can be called a ‘catalyst for change’ (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Boote, Buckley, Vougioukalou and Wright2017), is an example of how a new circle of impact was created. PAR's personal impact on one of the team members stimulated her creativity, allowing her to develop a brainwave, that subsequently resulted in a totally new project. A second team of volunteers was built, where the principles of the participatory approach were also introduced, which produced a new circle of personal and interpersonal PAR impacts. At that point the members of both teams found themselves in the vortex of new activities that exceeded by far the initial project goals. As a result, several new functional networks came to life, which included welfare, media, care and other voluntary organisations. Such a broad non-linear impact at the community level had not been anticipated at the time that the project was designed.

The newspaper continues to have a positive impact at the community level, which is confirmed by the large numbers of reactions that Jane receives each time after it has appeared. The new circles of community impact can be traced back to the strengthened feeling of belonging that older people experience when reading and discussing the paper with their friends and relatives; they feel that they are still a part of the community.

The popularity of the reminiscence sessions and the newspaper is still increasing. Continuation of the activities that the project focused on after the researchers left is a vital ex-post measuring point for the validity of its impacts (Israel et al., Reference Israel, Schulz, Parker, Becker, Allen, Guzman, Lichtenstein, Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel and Minkler2017; Abma et al., Reference Abma, Banks, Cook, Dias, Madsen, Springett and Wright2019). In our case, the juxtaposition of the impacts that the two initiatives are having cements their sustainability after completion of the project.

Our analysis of the impacts of PAR revealed two additional issues. The first one concerns gendered group dynamics. At the beginning of the project, the group dynamics replicated the gender roles that the team members had internalised: the power to make decisions was ‘allocated’ to the two older men and partly to the researcher who had prior knowledge of PAR, and the responsibility for carrying out the decisions was ‘assigned’ to the rest of the team. The upbringing of the team members might have played a role here. As a result, PAR could not work until all team members had started acting according to its principles. In comparison, the second team of the newspaper project showed very different dynamics. Jane led it and the other six members were all men. They worked harmoniously from the very beginning. The differences in the group dynamics could be explained by the fact that the second team focused on a clear-cut job that corresponded with their professional past, whereas the first team was searching for solutions in a field they had never worked in before. However, this does not fully explain why the male members of the newspaper team accepted the participatory principles, which the two men from the first team had not been able to agree to. In the literature on participatory research gender is often addressed in anthropological work (Cornwall, Reference Cornwall2003). In social gerontology little has been done so far to study (potential) gender tensions in community-based PAR projects. Our cautious conclusion at this stage is that any gendered tension that manifests itself during PAR must be explicitly addressed and analysed, otherwise it could well reinforce the gendered distribution of power that it is supposed to overcome.

The second issue concerns the involvement of frail older people as co-researchers. During our project no conditions or limitations regarding gender, ethnicity or social status were mentioned as possible barriers to participation in voluntary work. Frail health was raised as a potential barrier within the project team, because the workload of participation can exceed the (cap-)abilities of older people. This question about limitations in engagement can be seen as part of a broader discussion in social and critical gerontology about disengagement, active or productive ageing, and dynamics within and between the third and the fourth age (Grenier, Reference Grenier2012; Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2017). Our view on this issue is rooted in the process approach towards ageing that is characterised by heterogeneity and changeability of individual experiences of becoming older (Bendien, Reference Bendien, Kriebernegg, Maierhofer and Ratzenböck2014). A simple reference to a person's age or health status does not provide sufficient information about his or her desire or ability to become a co-researcher. The personal life history, social competences and cumulative (dis-)advantages of a person's life (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2020; Settersten, Reference Settersten, Settersten, Grenier and Phillipson2020) all play a role for or against participation. At FoR, most of the volunteers are active people of the third age. Many frail community-dwelling older people participated in reminiscence sessions with gratitude, but declined to become volunteers. Some did not explain, whereas others pointed at their frail health, but there can be more to it than that. Based on their age and health, Martha (85) and Elisabeth (74) had reached the fourth age; nevertheless they were both actively involved in the project. It is difficult to draw the line between the third and the fourth age as an indicator for a person's participation. In fact, involvement may be one of the effective ways of showing resistance against the idea of ageing that is solely understood as decline (Katz, Reference Katz, Settersten, Grenier and Phillipson2020). Resistance to comply with the inference ‘old is impaired and thus passive’ could lead to transformational change in how old age is socially constructed. However, how involvement of older people in research can be facilitated without ignoring the issues of frailty (Pickard, Reference Pickard2018) is a question for further investigation.

Finally, we should consider whether our findings can be generalised. The possibility to ‘transfer interventions from one locality to the next’ allows for an important form of societal impact (ICPHR, 2013a: 19). Blair and Minkler (Reference Blair and Minkler2009: 660) point out that ‘participatory research improves one facet of external validity, its relevance to end users of findings, but the more we make a study locally relevant, the more we make it potentially ungeneralizable beyond that setting and population’. To generalise, PAR then has to be understood in terms of meta-processes. Our results can be useful for PAR projects with older adults within and outside the Netherlands. Conditions that could be applied elsewhere to secure participation of older co-researchers are: (a) a moderate pace of the mutual learning process, (b) communicative space for co-labour and creativity, and (c) attention to gendered group dynamics. Another relevant point in this context is that PAR can be suitable for older people with various health conditions. Frailty of the co-researchers is not necessarily a barrier against participation, but more research is needed to address the ways in which their engagement can be facilitated. How we should generalise the findings also depends on the dissemination strategy. In our case, the circles of impacts reach beyond the boundaries of the province of Zeeland. The team was invited to present its work at several workshops and conferences that were organised throughout the country. The key messages to other initiatives were participation and collaboration: own your initiative and try to work together with other voluntary and (semi-)professional organisations. In our project the community impact of PAR with older people is local, but dissemination of its findings is ongoing, with the result that new impacts of that research are being generated continuously elsewhere.

We conclude that PAR that is conducted by older people can lead to impacts spreading like circles at various levels. The emancipatory effect of PAR has enabled personal growth of the team members through their collective learning process and has promoted most of them into a position of community leadership.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the input of the seven PAR team members and the many other volunteers who participated in this project. Our special thanks to Sylvia van Dam Merrett and Hanneke de Vroe, who read and commented on the draft version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch fund FNO. The financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis or interpretation of the data, or the writing of the study.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Ethical standards

This participatory project has been embedded in the research of the Centre for Client Experiences, Amsterdam, and meets all the necessary ethical standards for participatory action research.