1. Introduction

Students around the world are expected to engage with increasing numbers of English texts in higher educational contexts where the official medium of instruction is the local language (e.g., Graddol, Reference Graddol2006), presenting new challenges for students. Northern Europe has seen the fastest growth of internationalisation in higher education in recent years (Arnbjörnsdóttir, Reference Arnbjörnsdóttir, Arnbjörnsdóttir and Ingvarsdóttir2018), with the Nordic countries leading the shift (Gustafsson & Valcke, Reference Gustafsson, Valcke, Wilkinson and Gabriëls2021). The prevalence of English is reflected in the number of textbooks, book chapters and journal articles assigned in English at higher education institutions (HEIs). In Sweden, a Nordic country where English is a foreign language, nearly half of the required reading at the undergraduate level at ten HEIs is in English, despite Swedish being the official language of instruction. Furthermore, as many as 65% of undergraduate courses taught in Swedish require at least one text in English, and 24% require only texts in English (Malmström & Pecorari, Reference Malmström and Pecorari2022). HEIs in the Nordic countries do not require an English proficiency test score as a prerequisite for university admission (Busby, Reference Busby2020), instead relying on upper secondary schools to provide students with the necessary skills to be able to read the assigned texts in English without any support (Arnbjörnsdóttir, Reference Arnbjörnsdóttir, Arnbjörnsdóttir and Ingvarsdóttir2018). Despite this, there is little previous research on academic reading in higher education, particularly concerning undergraduate students’ experiences with and perceptions of academic reading (Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Reynolds and Delahunt2020). At the same time, there is a need for more work on the transition from secondary to tertiary education regarding differing levels of language proficiency and whether or not they lead to inequalities (Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2018). This poster offers preliminary findings from a project that aims to address both areas by illustrating the issue through the Swedish case and discussing students’ perceptions of academic reading in English. Two research questions are addressed:

1. What perceptions do first-year university and upper secondary school students in Sweden have of their preparation for and ability to read academic texts in English?

2. Do first-year university students in Sweden report challenges in relation to assigned reading in English and, if so, what challenges do they report?

2. Methodology

This project used a sequential explanatory design (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Plano Clark, Gutmann, Hanson, Tashakkori and Teddlie2003) involving two questionnaires with 505 participants and follow-up interviews with 12 of the participants. All participants were social science students in their first year of university (n = 206) or in one of the two last years of upper secondary school (n = 299). Three universities and 11 upper secondary schools participated in the study. The two questionnaires were designed to be as similar as possible but targeted one of the two groups of respondents and consisted of 35 questions related to reading (excluding demographic items which differed in number).

Closed-ended questionnaire items were analyzed in SPSS using a combination of descriptive and inferential statistics. Open-ended questionnaire items and interview transcripts were analyzed using a conventional approach to qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005), which was combined with quantitative content analysis. The latter takes a deductive approach with predetermined categories (White & Marsh, Reference White and Marsh2006), and in this case, the categories developed during the qualitative stage of the analysis (e.g., positive and negative attitudes) were used for the quantitative analysis.

3. Results and discussion

Preliminary results show that a majority of university students (68%) reported that they felt prepared to read assigned texts in English when they started university, whilst nearly one third (32%) reported being unprepared. However, more than half of the university students in the sample expressed negative attitudes including fear, anxiety and stress towards reading in English. Furthermore, just over one third of the university students reported that it is difficult to read assigned texts in English (35%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. How easy or difficult do you think it is to read the texts on your reading lists at university?

In comparison, 24% of upper secondary school students responded that it is difficult to read the fact-based texts assigned in English in school, perhaps suggesting that the texts upper secondary school students are exposed to are inadequate for preparing them for further education. Interview data and results from the open-ended questionnaire items furthermore suggest new students are unaware of the level of difficulty involved in assigned texts at university, as seen in (a), and that they would need to read texts in English at university, as shown in (b):

(a) I have almost never read any English literature in upper secondary school, so when you have to read English literature at university I feel a lot of pressure, that it will be difficult and that I will not understand. There should be a better transition between reading English literature in upper secondary school and in university. In upper secondary school we only read factual texts and books, nothing that comes close to what I read today. It's a difficult transition.

(b) Because my course is in Swedish, it seems strange that we need to read in English.

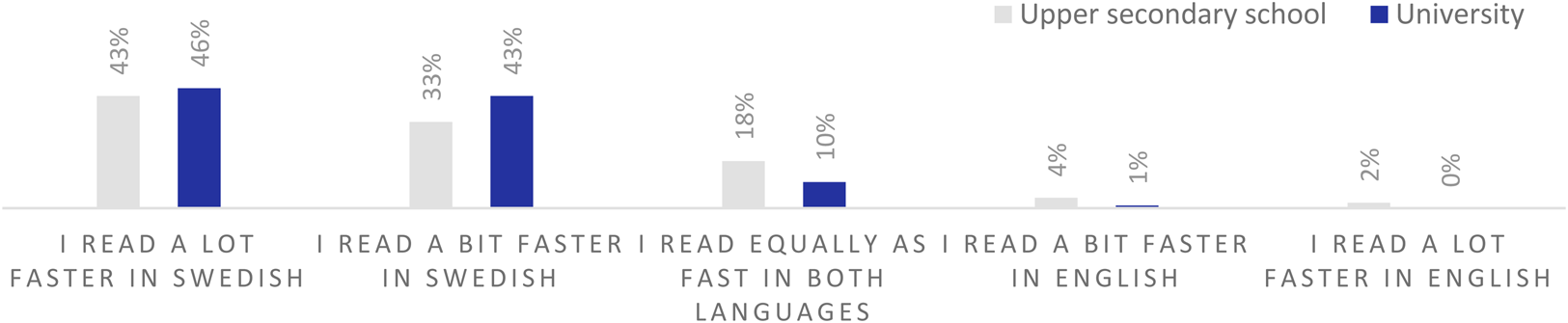

Common themes in the attitudinal data collected from the university students include a general lack of preparation for reading academic texts in English, difficulty understanding subject-specific vocabulary, and reading in English being considerably more time-consuming than reading in Swedish, as seen in Figure 2, which also includes the upper secondary school students.

Figure 2. Which language do you feel you read academic texts faster in?

The students’ reading rate in English is not only an issue in that it takes them longer to read, but also that it takes so much longer that nearly one third (32%) of the university participants frequently struggle to keep up with their assigned reading, which will likely impact their content learning, as exemplified by (c):

(c) I think it will take longer to get through than if it would have been in Swedish. I prioritize reading the course literature that is in Swedish first, which usually results in the English being read very sloppily or not at all.

Interview data further suggests that students who have lower grades in the first two required English courses in upper secondary school are actively discouraged from attending the optional English course in their final year of upper secondary school, likely making the transition from secondary to tertiary education more difficult. Students’ lack of preparedness for reading assigned texts in English can be categorised into two groups:

(1) Insufficient knowledge of English in general, e.g., students who perceive themselves to be bad at English say they have not used English for several years and/or rarely read in English.

(2) Insufficient knowledge of academic English, e.g., those who claim to be unfamiliar with academic texts in English blame ‘bad teachers’ in high school and/or a large gap between the ‘everyday English’ taught in upper secondary school and the level required at university.

4. Reflections

The ability to comprehend academic texts is one of the most important skills that English as a Second Language (ESL) and English as a Foreign Language (EFL) university students need to acquire (Nergis, Reference Nergis2013, p. 1). The Nordic countries are amongst the highest scoring countries in the world on English proficiency tests (Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2020) and students in these countries should have minor issues—if any—transitioning from secondary to tertiary education. However, as the preliminary results outlined above indicate, this does not appear to be the case and questions we should perhaps all be asking are whose responsibility it is to prepare students for tertiary education and if universities, including university faculty, need to be providing reading support for all students.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444822000246

Linda Eriksson is a Ph.D. student in Humanities with a subject specialisation in English at Örebro University in Sweden. She is a member of Örebro University's graduate school in Educational science with a focus on didactics.