Electoral accountability, conceived as the process of ‘institutional aggregation’ of citizens’ voting behaviour and the selection of policymakers through the contestation of free and fair elections, represents the sine qua non of any minimal definition of democracy (Powell Reference Powell2004; Schmitter and Karl Reference Schmitter and Karl1991). The existence of a ‘vertical linkage’ between voters and representatives gives citizens the prerogative to hold governments responsible for their actions, and governments the possibility of providing a public account of their decisions and actions. Much of the literature focuses on retrospective economic voting (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Key Reference Key1966; Singer and Carlin Reference Singer and Carlin2013), broadly describing the existing link between citizens’ economic evaluations and voting behaviour. However, Donald Stokes (Reference Stokes1963, Reference Stokes1992) suggests enlarging the scope of research to non-economic valence issues that might influence voting behaviour. Following that approach, this article focuses on individual perceptions of electoral integrity as a determinant of electoral accountability, analysing the extent to which this policy issue might eventually hold incumbent governments accountable. While several studies attempt to look at possible non-economic determinants of electoral accountability (Clark Reference Clark2009; Ecker et al. Reference Ecker, Glinitzer and Meyer2016; Lago and Montero Reference Lago and Montero2006; Shabad and Slomczynski Reference Shabad and Slomczynski2011; Singer Reference Singer2011), research on electoral integrity usually focuses on its effect on institutional trust, political turnout or democratization.

According to democratic theory, elections have the ultimate function of generating governments that should be held accountable to voters (Powell Reference Powell2000). Poorly conducted elections might imply severe consequences for the quality and legitimacy of the political system (Norris Reference Norris2014), representing – especially in new democracies such as those in Latin America or Central and Eastern Europe – a policy dimension on which citizens may evaluate government performance through their vote choices (Bratton and Chang Reference Bratton and Chang2006; Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchick2011). In this perspective, electoral integrity assumes the characteristics of a valence issue, meaning any condition able to ‘coagulate’ large majorities of voters about desired policy outcomes (Stokes Reference Stokes1963). Voters might reward government parties for rosier perceptions of electoral integrity or express dissatisfaction with opaque electoral practices, lowering support for incumbents.

However, the extensive literature on performance voting suggests that citizens’ retrospective evaluations might suffer from an ‘instability paradox’ deriving from individual characteristics as well as contextual differences between countries (Bellucci and Lewis-Beck Reference Bellucci and Lewis-Beck2011; Charron and Bågenholm Reference Charron and Bågenholm2016; Powell and Whitten Reference Powell and Whitten1993; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007). Specifically, previous research has clearly shown how complex decision-making systems risk undermining voters’ potential to assign responsibility for economic performance (Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013). This evidence brings us to ask under what conditions voters do connect concerns about electoral integrity with their evaluations of incumbent governments. To answer this question, I employ individual-level data from Wave 6 of the World Values Survey (WVS) collected between 2010 and 2014 to conduct a wide cross-nation analysis of electoral integrity as a key determinant of electoral accountability and the moderating effect exerted by micro- and macro-level factors in 23 democracies worldwide. The analysis, in fact, is integrated by country-level data capturing the effect of two specific features of the political context: government clarity of responsibility and media freedom. The results confirm the reliability of the valence model for the study of electoral integrity performance-based voting: voters show their support for a government with higher levels of election quality with different intensity depending on micro- and macro-level characteristics. More specifically, non-partisan voters are more likely to vote according to such perceptions, while these dynamics are facilitated in countries where the characteristics of the government make the assignment of responsibility easier and where the media efficiently fulfil their function as watchdog of government activity.

The article proceeds as follows. The next section develops the theoretical framework guiding the empirical analysis. Thereafter, hypotheses concerning the effects of partisanship at the individual level and the contextual characteristics at the country level are formulated. These assumptions are tested using a logistic multilevel analysis of survey data. The conclusion discusses the implications of the results.

Performance voting: going beyond economy

The literature traditionally studies electoral accountability through the lens of economic voting – that is, the way in which government performance, in terms of macro-economic outcomes, affects voting behaviour (Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck Reference Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck2017; Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008). In this way, a substantial portion of political scientists have devoted their energies to the search for evidence of it, concluding that voters are ‘rational’, ‘economic’, ‘retrospective’, rewarding governments for good economic outcomes and punishing them for bad (Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck Reference Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck2014; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Key Reference Key1966; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007). This research developed around the ‘valence paradigm’ (Stokes Reference Stokes1963, Reference Stokes1992), according to which citizens’ preferences are not ‘spread on a continuum extending between good times and bad’ but are mostly concentrated ‘at the good times end of such a continuum’ (Butler and Stokes Reference Butler and Stokes1969: 390). In order to present themselves as the most competent and credibly committed, all the parties tend to converge towards positions closer to the socially preferred goals.

In this framework, considering the economy as the only issue activating the valence model turns out to be rather limiting, given that other dimensions of governance might affect citizens’ vote choice as well (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Kellner, Twyman and Whiteley2015; Ecker et al. Reference Ecker, Glinitzer and Meyer2016; Singer Reference Singer2011; Stokes Reference Stokes1963, Reference Stokes1992). The integrity of elections could be conceived, in fact, as a valence issue to the extent it represents a dimension of government evaluation ‘along which all voters hold identical positions (preferring more to less)’ (Stokes Reference Stokes1992: 143). Alternative definitions of election quality predominate in different subfields of the research literature. However, Pippa Norris (Reference Norris2014: 21) states that the notion is conceived as referring to norms universally applied ‘throughout the electoral cycle, including during the pre-electoral period, the campaign, on polling day, and its aftermath’. In other words, it concerns the efficient performance of electoral procedures and processes (Alvarez et al. Reference Alvarez, Atkeson and Hall2012). Such a comprehensive definition involves several dimensions of elections, consisting in 11 sequential stages: electoral law, electoral procedures, boundaries, voter registration, candidate registration, campaign media, campaign finance, voting process, vote count, results and electoral management bodies. It is evident how relevant is the – direct and indirect – role of elected officials in all the stages of the process, because of the regulatory action exerted by the government’s ministries or departments in this field and their access to material resources (Carreras and Irepoglu Reference Carreras and Irepoglu2013; Schedler Reference Schedler2002).

Despite often-voiced claims about the positive consequences of a free and fair electoral process for the quality of democracy and citizens’ satisfaction with the political system, very little empirical evidence exists in relation to electoral accountability. Most of the research on electoral integrity focuses rather on its effect on electoral turnout, political trust or democratic consolidation, neglecting the possibility that performance voting could work in this policy domain (Anderson and Tverdova Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2009; Martinez i Coma and Trinh Reference Martinez i Coma and Trinh2017; Norris Reference Norris2014). Do public perceptions of election quality structure attitudes about political behaviour in substantial ways, specifically in terms of performance voting?

Norris (Reference Norris2017) theorizes that the potential for citizens to blame incumbents for negative evaluations of electoral integrity exists, but it could be favoured by specific conditions, such as: the existence of a free flow of information about the integrity of electoral procedure; the relevance of election quality for citizens as an issue; the likelihood of governments being blamed for their abuse of power; the possibility of alternation between government and opposition through competitive elections. The concurrence of these four conditions would give voters the power to hold incumbents accountable for any problem arising during the electoral process.

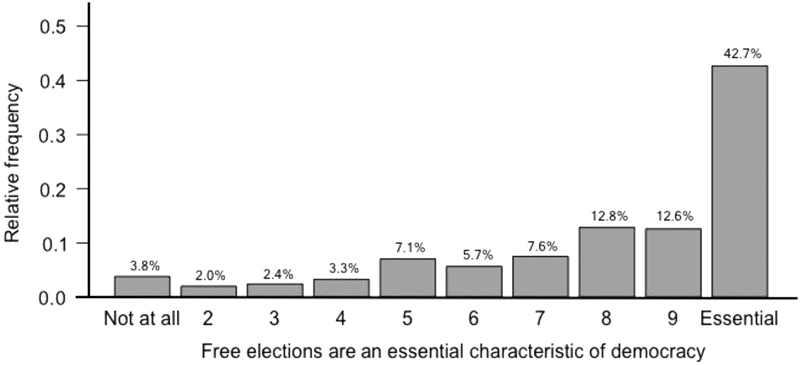

Survey data presented in Figure 1 seem to provide partial support to the empirical evidence for my theoretical proposition that electoral integrity represents an important instrument through which citizens define and measure regime performance (McAllister and White Reference McAllister and White2015). The distribution of responses resembles that of valence issues, with 75.7% of the respondents (values equal or more than 7 on a 10-point scale) considering the integrity of electoral process an essential characteristic of any democratic regime. In this perspective, policymakers may be held accountable for any reported problem in electoral integrity – concerning, for instance, electoral law, media coverage, campaign finance, vote count or gerrymandering – and pay for it with widespread discontent among citizens. Not only younger democracies, but also well-established and consolidated ones can experience procedural weaknesses, technical problems and lack of capacity in the management of electoral processes that have the potential to generate widespread discontent among the electorate (Conaghan Reference Conaghan2005; Norris Reference Norris2017).

Figure 1 Free Elections Are an Essential Characteristic of Democracy Source: Author’s elaboration on data from Wave 6 of the World Values Survey (2010–14). Note: The question was as follows: ‘V133: Please tell me for each of the following things how essential you think it is as a characteristic of democracy: People choose their leaders in free elections’. (Respondents=38,708; Countries=23).

As recent works show, in contexts where specific issues are regarded as sufficiently salient to influence vote choice, they can condition political behaviour and – eventually – constitute a decisive determinant of voters’ judgements of an incumbent’s past performance (Beaulieu Reference Beaulieu2014). These circumstances could trigger public dissatisfaction towards the political elite and be translated into a consistent loss of support for the incumbent coalition/party, or electoral reward for the opposition (Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchick2011).Footnote 1 Governments can be blamed for problems in the management of electoral procedures – as conceived in Norris’s broader notion – because they are directly involved in the functioning of those processes. These dynamics could also be facilitated in those contexts – as in several European democracies, such as Germany, Norway or Italy – that are characterized by the ‘governmental model’ of electoral administration, where the organization of elections is typically managed by ministries or offices that are directly linked to the government itself, or where government parties have the power to pass legislation to regulate strategic aspects of elections such as the drawing of district boundaries, the coverage of political debates among political actors by the state broadcaster, the regulation of public funds for political parties, and so on.

I thus theorize that citizens’ perceptions affect support for government parties and that incumbents are directly responsible to voters for any problem connected to the quality of electoral procedures. The resemblance of electoral integrity to valence issues suggests its adaptability to the traditional model of performance voting (Lewis-Beck and Nadeau Reference Lewis-Beck and Nadeau2011) – that is, the reward-or-punishment mechanism established between voters and incumbent governments. Given that citizens value the quality of democratic procedures, parties agree on the desired policy goal, conceived in terms of higher levels of electoral integrity. In this way, perceptions about the integrity of electoral procedures are likely to play a decisive role in the functioning of the accountability mechanism, pushing voters to express dissatisfaction with less virtuous electoral practices by punishing incumbent governments in the ballot box. Conversely, voters who perceive positively the way in which the electoral cycle works should reward incumbent parties when they cast their vote. These considerations lead me to formulate the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Rosier perceptions of electoral integrity positively affect the probability of voting for the incumbent.

However, there are potential issues of endogeneity that need to be addressed. Studies on performance voting (Anderson Reference Anderson2007; Evans and Andersen Reference Evans and Andersen2006; Fraile and Lewis-Beck Reference Fraile and Lewis-Beck2010; Nadeau et al. Reference Nadeau, Lewis-Beck and Belanger2013; Wlezien et al. Reference Wlezien, Franklin and Twiggs1997) extensively discuss the problem of the position of a presumed explanatory variable in a causal proposition: that is, ‘whether policy preferences, economic evaluations, or government approval (co-)determine party choice, or whether they are rather derived from party choice or party attachments’ (Van der Eijk Reference Van der Eijk2002: 39). The direction of the relationship between individual evaluations/perceptions and voting behaviour is still disputed. Regarding the present study, it might be claimed that the relationship between the main independent and the dependent variables is ‘the other way around’: that is, that electoral preferences influence and structure perceptions of electoral integrity. According to this view, individuals who voted for the incumbent in the last election – the so-called ‘electoral winners’ – would tend to perceive government performance more positively than those who are generally classified as ‘electoral losers’.

This issue is quite hard to address with cross-sectional data such as those from the WVS as it requires, instead, longitudinal panel survey data allowing measurements of the same individuals in ‘t’ and ‘t + 1’. Such an analysis would allow, in fact, a clearer estimation of causality among independent and dependent variables. However, the question on party support included in the data set is ‘prospective’ rather than ‘retrospective’, asking which party the respondent would vote for ‘if there were elections tomorrow’, rather than which party the respondent voted for in the ‘last election’. In other words, the potential endogeneity could be overcome by the fact that individual perceptions of electoral integrity are temporally prior to the party choice in the following elections. Another element that accounts for potential biases in the estimates is represented by the inclusion in the analysis presented below of ‘partisanship’ as a moderating variable. As previous studies on retrospective voting suggest, controlling for partisanship has the potential to tackle endogeneity problems, given that the influence of perceptions of economic problems or corruption scandals on vote intention has been shown to be generally stronger among non-partisans rather among than voters who belong to a specific party (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Ecker et al. Reference Ecker, Glinitzer and Meyer2016).Footnote 2

These considerations might not fully satisfy the concerns of those who express doubts about the endogeneity of individual perceptions of electoral integrity. Residual scepticism towards the use of an independent variable measuring respondents’ perceptions could still exist, since they might be strongly contaminated by respondents’ partisanship and subject to severe endogeneity problems (Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007). A strategy to further relieve these concerns is the adoption of the ‘macro-level’ approach proposed by Gerald Kramer (Reference Kramer1983) and the related literature that claims that aggregate measures of performance evaluation are more reliable predictors of people’s behaviour than individual perceptions. I thus check the robustness of the baseline effect of electoral integrity on support for the incumbent by running the main model with an alternative specification of the main independent variable – that is, by substituting individual perceptions of electoral integrity with an exogenous, country-level indicator of electoral integrity (see also note 6 and Figure A.1 in the online Appendix). The test is presented in the section ‘Robustness Checks’ below, while its results are provided in the online Appendix (Table A.4). Electoral integrity – also deprived of any endogenous biases – shows its significant effect in structuring support for the government, thus contributing not only to discourage further claims about the ‘ideological nature’ of citizens’ perceptions, but also to provide further support to the first and, indirectly, also to the second hypothesis.

Including the context: electoral integrity performance voting

The use of voters’ evaluations of government performance to predict changes in electoral support usually shows variation across countries and over time (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010; Chappell and Veiga Reference Chappell and Veiga2000; Clark Reference Clark2009; Paldam Reference Paldam1991). Thus, an extensive literature focuses on the role of individual- and contextual-level features on voters’ assignment of responsibility for government performance.

Starting from the individual characteristics that might moderate electoral integrity performance voting, we must consider partisanship. According to the extensive literature on electoral accountability, voters with weak or no ties to political parties are more sensitive to short-term issues – for instance, economic performance or corruption scandals – when they cast their vote (De Vries and Giger Reference De Vries and Giger2014; Kayser and Wlezien Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011). In this perspective, citizens who are engaged in political parties but also dissatisfied with the way in which the incumbent government did its job are less inclined to vote according to personal evaluations because of their stronger ideological ties (Gherghina Reference Gherghina2011). Conversely, those who are not close to any party will be more sensitive to this kind of short-term factor (Tilley and Hobolt Reference Tilley and Hobolt2011). The same rationale could be adopted for electoral integrity performance voting, where I expect to find that partisanship has a moderating effect on the attribution of responsibility for different levels of electoral integrity:

Hypothesis 2: The influence of perceptions of electoral integrity on the probability of voting for the incumbent is stronger for non-partisans than for voters who belong to a political party.

The literature on performance voting clearly shows the relevance of ‘contextual’ characteristics for the study of accountability. This article aims to test these assumptions with reference to electoral integrity performance voting. Even though there is a growing counter-literature which questions this argument (Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck Reference Dassonneville and Lewis-Beck2017; Ecker et al. Reference Ecker, Glinitzer and Meyer2016), it has been shown that the strength of the link between government economic performance and electoral outcomes might be mediated by countries’ ‘government clarity of responsibility’ (Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013; Schwindt-Bayer and Tavits Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Tavits2016; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007) and, in particular, by the specific characteristics of the current government. Single-party – or even compact coalition – governments that are stable throughout the legislature and can count on a clear majority in parliament make it easier for voters to identify who is responsible for policy decisions. This contextual feature turns out also to be relevant in the case of electoral integrity performance voting. In most countries included in the analysis, for instance, electoral management bodies (EMBs) – the national electoral commissions – are usually linked to the executive power because of direct control exerted by a specific department or because of their specific appointment procedures (Birch Reference Birch2011; Moreno et al. Reference Moreno, Crisp and Shugart2003). This element could make government support more sensitive to voters’ perception of electoral integrity such as judgements on scandals arising during the electoral process in contexts characterized by higher clarity of responsibility. Following these arguments, I expect electoral integrity performance voting to be stronger where voters are able to assign political responsibility for the way in which elections are managed:

Hypothesis 3: In contexts characterized by higher clarity of responsibility, the probability of voting for the incumbent government will be more influenced by individual perceptions of electoral integrity.

Christopher Anderson (Reference Anderson2007: 590), however, stresses the relevance of political context, arguing that ‘the impact of voters’ motivations to reward or punish, in turn, is contingent on political structures’. He proposes the concept of ‘political environment’, in which ‘citizens form opinions and act’ and which mediates ‘the effects of individual-level factors on citizen behaviour’. This broad concept seems to include not only the institutional arrangement regarding government and party system but also contextual features that might influence government accountability ‘from below’, such as the mass media and their degree of freedom and pluralism that guarantees information on political acts promoted by the government and gives voters the possibility of identifying and potentially sanctioning or punishing it.

In the framework of electoral integrity performance voting the media acquire further relevance, representing a compensative check on manipulative politicians and institutions with low levels of independence from the political power (Besley et al. Reference Besley, Burgess and Prat2002; Birch Reference Birch2011; Green-Pedersen et al. Reference Green-Pedersen, Mortensen and Thesen2015). Even though there is broad theoretical support for this concept, there is moderate but growing empirical evidence for it. These works show that people exposed to high-quality media coverage of political issues are better informed, more civically engaged and more inclined to participate in the elections (De Vreese and Boomgaarden Reference De Vreese and Boomgaarden2006; Fraile Reference Fraile2013). In order to judge their government’s performance in terms of electoral integrity, citizens need to be informed about this issue from a plurality of sources, in particular from the media. The media have the potential to make power-holders responsible and enforce sanctions by creating opportunities or structures for citizens to do this. Such an action is mostly carried out through specific effects, such as agenda setting (that is, the influence of media coverage on the issue considered important) and priming (that is, the tendency to focus on the standards by which incumbents are judged, calling attention to specific issues), that shape individuals’ perceptions about political reality (Fournier et al. Reference Fournier, Blais, Nadeau, Gidengil and Nevitte2003; Odugbemi and Norris Reference Odugbemi and Norris2009; Winters and Weitz-Shapiro Reference Winters and Weitz-Shapiro2013). This evidence leads us to hypothesize that the media’s tendency to emphasize negative information enhances performance voting: that electoral accountability is likely to be strengthened where the media shed light on election management:

Hypothesis 4: In contexts characterized by more plural and freer media – that is, where information about cases of electoral malpractice are more available to citizens – electoral integrity performance voting will be greater.

Because of the growing importance attributed to the quality of electoral procedures, generating a better understanding of the causes and consequences of variation in electoral accountability represents a key point for this academic research. This article aims to contribute to the literature by looking at a variety of democracies in which the quality of electoral procedures and the moderating effect of contextual characteristics on the link between performance and vote might play a role in electoral accountability.

Data and methods

To test my hypotheses, I employ individual-level data from Wave 6 of the World Values Survey. It is a cross-national survey collected between 2010 and 2014 that covers 61 countries, including 29 countries worldwide in which the electoral integrity battery is administered. Of these, I include in the analysis only the 23 countries classified by the Polity IV project as ‘full democracy’ or ‘democracy’ in the reference years (2011–14).Footnote 3 Thus, the selected sample is composed of 37,225 respondents.Footnote 4

The decision to consider only a specific set of countries lies in the fact that the present research aims to analyse a relevant aspect of the quality of democracy – electoral accountability. For this reason, the sample is composed of all those countries whose political systems include the three elements Polity IV considers essential to classify them as ‘democracies’: institutions and procedures allowing citizens to select alternative policies and leaders; a system of ‘checks and balances’ on the exercise of the executive power and the guarantee of civil liberties in political participation to all citizens (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2016). Finally, this broad comparative sample, covering well-consolidated democracies (such as Germany, the Netherlands and Australia), where citizens have rosier perceptions about the fairness of the electoral process, and newly democratized countries from East Central Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa (such as Romania, Georgia, Colombia, the Philippines and Ghana) gives the analysis the potential to uncover dynamics that are common to all groups of countries.

Dependent variable

To test my expectations at the individual level, a traditional measure of national vote intention is used as a dependent variable. It asks:

If there were a national election tomorrow, for which party on this list would you vote?

Responses to this item are dichotomized (0–1), distinguishing between respondents who would vote for an opposition party (0) and respondents who would vote for a government party (1).Footnote 5 Consequently, they are divided between government party voters (46.1% of voters) and opposition party voters (53.9% of voters). This choice permits me to employ a multilevel logistic regression model to analyse the relation between dependent and independent variables at both the individual and country level.

Independent variable

As an independent variable, I use a composite measure of the perception of electoral integrity. I built it using specific items included in the survey to enquire about this aspect:

In your view, how often do the following things occur in [this country’s] elections?

- Votes are counted fairly (on a four-point scale, 1–4)

- Journalists provide fair coverage of elections (on a four-point scale, 1–4)

- Election officials are fair (on a four-point scale, 1–4)

- Voters are offered a genuine choice in the elections (on a four-point scale, 1–4)

This WVS wave, in fact, provides the most extensive battery of items which can be used to examine individual‐level factors contributing to perceived integrity of electoral procedures, encompassing important stages of the electoral process (Norris Reference Norris2014).Footnote 6

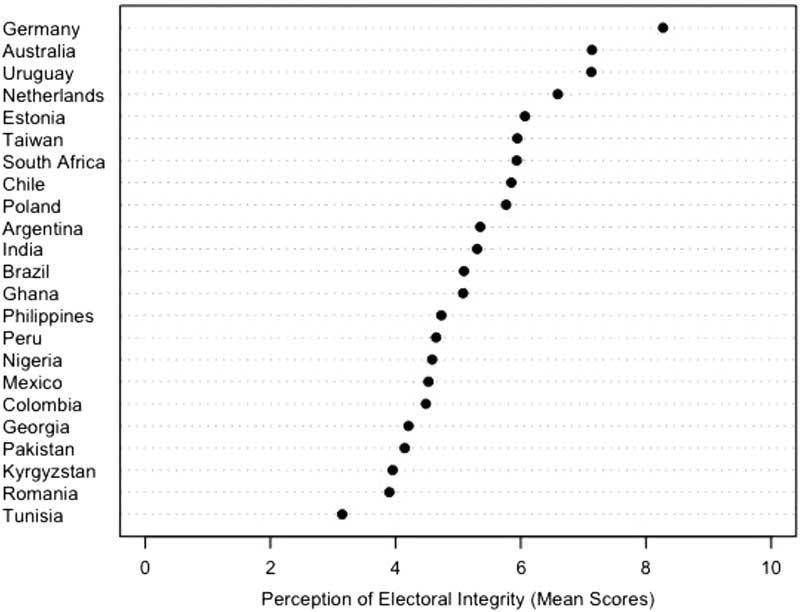

Given that the four items are quite highly correlated, I summarize them into one variable using Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Table 1 displays the results of the latent variable model. The estimates confirm the presence of one underlying dimension and that all the measures make a relevant contribution to it. Furthermore, the latent variable ‘Perception of Electoral Integrity’ explains much of the variability of the four indicators. The standardized factor scores are then computed to build the new variable, which is rescaled to range from 0 to 10. Figure 2 shows the mean values for each country included in the analysis.

Figure 2 Mean Scores for Each Country of the Latent Variable ‘Perception of Electoral Integrity’

Table 1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Latent Variable ‘Perception of Electoral Integrity’

Note: N=19,893.

Moderating variables

As moderating variables, I collected data at both micro and macro levels to study the possible effect of different factors on voters’ behaviour. To test the conditional effect of individual characteristics and, in particular, the moderating effect of partisanship on electoral integrity performance voting, I employ an item measuring respondents’ ties to a political party:

Could you tell me whether you are an active member, an inactive member or not a member of a [political party]?

Answers to this question are then recoded and dichotomized from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no partisanship and 1 indicating a voter’s identification with a party.

I also use two independent variables collected at the country level, namely government clarity of responsibility and media freedom. A vast literature discusses possible measures for capturing clarity of responsibility at the institutional as well as at the government level (Anderson Reference Anderson2000; Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson2004; Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013; Tavits Reference Tavits2007). In this study, I adopt a more straightforward measure for government clarity of responsibility.Footnote 7 It derives from Åsa Bengtsson’s (Reference Bengtsson2004) additive index, which focuses exclusively on the dispersion of power within the current government. It is an additive index capturing three important features of government responsibility: parliamentary support (minority/majority government), diversion of power (coalition/single-party government) and government stability (less than/two or more years in power), giving one point for each aspect considered clear. Scores for each aspect are then summarized and divided by three. Consequently, countries are coded as having values ranging from 0 (low clarity) to 1 (high clarity). The choice to consider only government characteristics is in line with the innovative approach proposed by Sara Hobolt, James Tilley and Susan Banducci (2013) that demonstrates how ‘government’ – rather than ‘institutional’ – clarity has a greater impact on the degree of performance voting in a country.

Freedom of the flow of information is collected using the World Press Freedom Index, published annually by Reporters without Borders. This index ranks each country on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 being the best possible score and 100 the worst. I inverted the original index, so higher values indicate greater levels of freedom of the media.Footnote 8 This index represents one of the most complete measures of media freedom, since it is built on survey data that encompass six main fields that may affect the freedom of the media system: political pluralism, media independence, environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency and infrastructure. The result is weighted with a score reflecting the level of violence against journalists, giving the final index.Footnote 9

Control variables

Finally, I include in the analysis a series of sociodemographic controls for education (highest level attained), political interest (on a four-point scale), gender and age (in full years) derived from WVS questions. They are integrated by a macro-economic indicator for the level of unemployment to control for incumbents’ economic performance and the level of corruption in each country, as measured by Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI).Footnote 10 Since these are not the principal focus of this study, they will not be discussed in the results.

Given the different nature of data – collected at both the micro and macro level – the analysis needs the use of multilevel logistic regression models to estimate direct and cross-level effects among variables with random intercepts accounting for unobserved heterogeneity between countries (Gelman and Hill Reference Gelman and Hill2007).Footnote 11 Individual respondents are, in fact, nested into nation-states so that each country has a different set of parameters for the random factors, allowing intercepts to vary by nation.

Results

Table 2 presents five multilevel logistic regression models in which the hypotheses are tested. All the models predict incumbent vote intention relative to opposition vote intention in relation to individual perceptions of electoral integrity. The models employed could be exemplified by the following equation:

$$\eqalignno { \log it ( {Y^{\asterisk} _{\rm ij} )} & {\equals}\beta _{0{\rm j}} {\plus}\beta _{{1{\rm j}}} \,Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{2{\rm j}}} \,Education\,level_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{3{\rm j}}} \,Political\,interest_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\,{\plus}\beta _{{4{\rm j}}} \,Gender_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{5{\rm j}}} Age_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr &\beta _{{0{\rm j}}} {\equals}\gamma _{{00}} {\plus}\gamma _{{01}} \,Government\,clarity_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{02}} \,Media\,freedom_{{\rm j}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\gamma _{{03}} \,Unemployment_{{\rm j}} {\plus} {\plus}\gamma _{{04}} \,Corruption_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\delta _{{0{\rm j}}} \cr & \beta _{{1{\rm j}}} {\equals}\gamma _{{10}} {\plus}\gamma _{{11}} \,Partisanship_{{\rm j}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\gamma _{{12}} Government\,clarity_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{13}} Media\,freedom_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\delta _{{1{\rm j}}} $$

$$\eqalignno { \log it ( {Y^{\asterisk} _{\rm ij} )} & {\equals}\beta _{0{\rm j}} {\plus}\beta _{{1{\rm j}}} \,Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{2{\rm j}}} \,Education\,level_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{3{\rm j}}} \,Political\,interest_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\,{\plus}\beta _{{4{\rm j}}} \,Gender_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{5{\rm j}}} Age_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr &\beta _{{0{\rm j}}} {\equals}\gamma _{{00}} {\plus}\gamma _{{01}} \,Government\,clarity_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{02}} \,Media\,freedom_{{\rm j}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\gamma _{{03}} \,Unemployment_{{\rm j}} {\plus} {\plus}\gamma _{{04}} \,Corruption_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\delta _{{0{\rm j}}} \cr & \beta _{{1{\rm j}}} {\equals}\gamma _{{10}} {\plus}\gamma _{{11}} \,Partisanship_{{\rm j}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\gamma _{{12}} Government\,clarity_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{13}} Media\,freedom_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\delta _{{1{\rm j}}} $$

Table 2 Multilevel Logistic Regression Models of Incumbent Vote Intention

Source: Wave 6 of the World Values Survey (2010–2014).

Notes: Dependent variable: national vote intention for incumbent government parties (0–1).

Standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients: *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; ***p≤0.001.

Through substitution, we obtain the following single mixed-effects equation:

$$\eqalignno{ logit(Y^{{\asterisk}} _{{{\rm ij}}} )&{\equals}\gamma _{{00}} {\plus}\gamma _{{01}} \,Government\,clarity_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{02}} Media\,freedom_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{03}} Unemployment_{{\rm j}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\gamma _{{04}} Corruption_{{\rm j}} {\plus}{\plus}\gamma _{{10}} \,Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\gamma _{{11}} \,Partisanship_{{{\rm j }{\asterisk}}} Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr & \quad {\plus}{\rm }\gamma _{{12}} \,Government\,clarity_{{{\rm j}\,}} _{{\asterisk}} Pei_{{ij}} {\plus}\gamma _{{13}} \,Media \,{\rm }freedom_{{{\rm j}{\asterisk}}} Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\beta _{{2{\rm j}}} \,Education\,level_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{3{\rm j}}} Political\,interest_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\,{\plus}\beta _{{4{\rm j}}} \,Gender_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr &\quad {\plus} \beta _{{5{\rm j}}} \,Age_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\delta _{{0{\rm j}}} {\plus}\delta _{{1{\rm j}}} $$

$$\eqalignno{ logit(Y^{{\asterisk}} _{{{\rm ij}}} )&{\equals}\gamma _{{00}} {\plus}\gamma _{{01}} \,Government\,clarity_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{02}} Media\,freedom_{{\rm j}} {\plus}\gamma _{{03}} Unemployment_{{\rm j}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\gamma _{{04}} Corruption_{{\rm j}} {\plus}{\plus}\gamma _{{10}} \,Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\gamma _{{11}} \,Partisanship_{{{\rm j }{\asterisk}}} Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr & \quad {\plus}{\rm }\gamma _{{12}} \,Government\,clarity_{{{\rm j}\,}} _{{\asterisk}} Pei_{{ij}} {\plus}\gamma _{{13}} \,Media \,{\rm }freedom_{{{\rm j}{\asterisk}}} Pei_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr & \quad {\plus}\beta _{{2{\rm j}}} \,Education\,level_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\beta _{{3{\rm j}}} Political\,interest_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\,{\plus}\beta _{{4{\rm j}}} \,Gender_{{{\rm ij}}} \cr &\quad {\plus} \beta _{{5{\rm j}}} \,Age_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}{\epsilon}_{{{\rm ij}}} {\plus}\delta _{{0{\rm j}}} {\plus}\delta _{{1{\rm j}}} $$

where Y*ij=[π ij /1−π ij ], that is the probability that voter i in a given country j votes for a government party in the next elections, and where subscripts i ∈{1,2,...N} and j ∈{1,2,...N} represent units for the individual and country levels, respectively.

Model 0 accounts for the adoption of the multilevel methodology of analysis. In Model 1 I simply include our key independent variable to test the effect of perceptions of electoral integrity on voting behaviour. Model 2 tests the moderating effect of partisanship on incumbent vote intention as electoral integrity changes. In Model 3 I test the interaction effect of government clarity on performance voting. Finally, Model 4 includes the moderating effect of press freedom on performance voting based on citizens’ perception of electoral integrity.

Model 0 represents the null – or intercept-only – model to test how much variance in the dependent variable stems from country differences. It shows that 20% (Rho=0.20) of the total variance in the incumbent vote is explained at country level, demonstrating the necessity to perform a multilevel analysis.

Therefore, I start the analysis by testing whether voters use their perceptions of electoral integrity to judge (retrospectively) incumbent government parties (Hypothesis 1). I modelled random intercept models that control for country-specific effects to ensure that unobserved differences between countries are not driving key findings. Model 1 presents the results. As hypothesized in the second section, citizens’ perceptions of electoral fairness have a positive and statistically significant effect on vote intentions for the incumbent. People with more positive perceptions about the integrity of electoral procedures are more likely to vote for the incumbent government. Moreover, the magnitude of the effect is quite high, as well as its marginal effect: increasing the level of electoral integrity perception by one unit, in fact, increases the probability of voting for the incumbent by 4.6 percentage points, maintaining all other independent variables at their mean. Thus, these findings not only confirm our theoretical statements, encouraging us to accept the first hypothesis; they also show the significant effect exerted by electoral integrity perceptions on an incumbent’s fate, comparable to that of individual economic evaluations traditionally employed as a key explanatory variable in research on electoral accountability (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008).

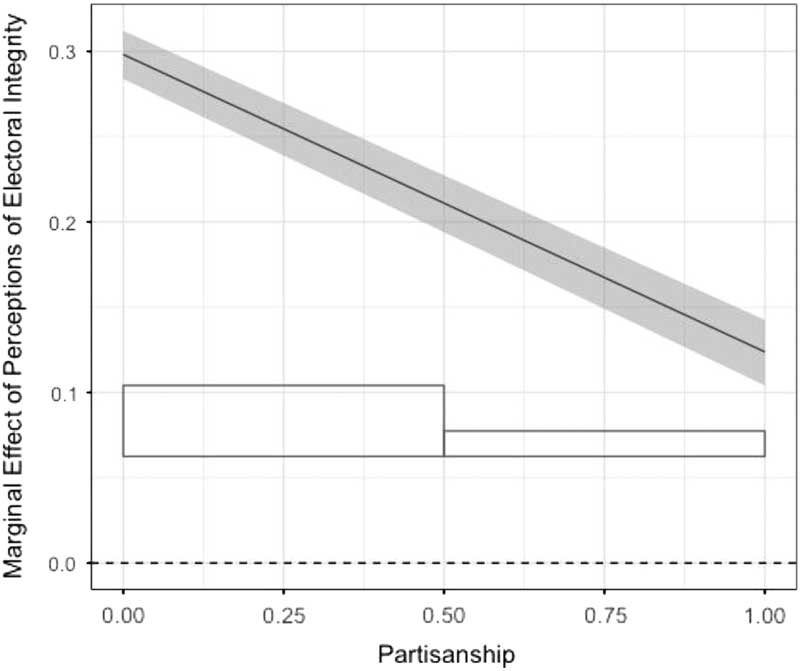

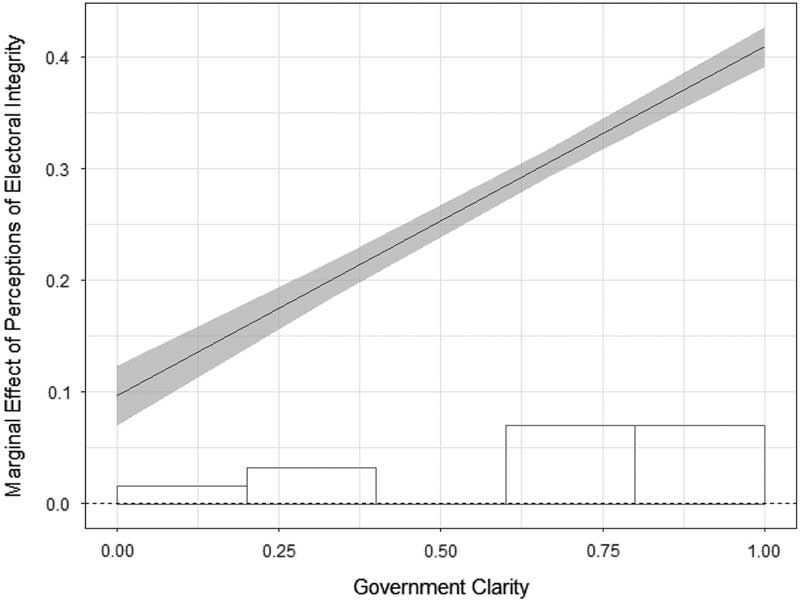

For an easier interpretation of the interactions presented in Models 2–4, we can look at the plots in Figures 3–5, where the marginal effect of electoral integrity perceptions for different levels of the moderating variables is represented.

Figure 3 The Effect of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity on Incumbent Vote Intention, Depending on the Level of Partisanship Note: The figure shows the estimated marginal effect of a one-unit change in perceptions of electoral integrity on incumbent support, conditional on the level of partisanship. All estimates and the 95% confidence interval are based on Model 2, Table 2.

Figure 4 The Effect of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity on Incumbent Vote Intention, Depending on the Level of Government Clarity Note: The figure shows the estimated marginal effect of a one-unit change in perceptions of electoral integrity on incumbent support, conditional on the level of government clarity. All estimates and the 95% confidence interval are based on Model 3, Table 2.

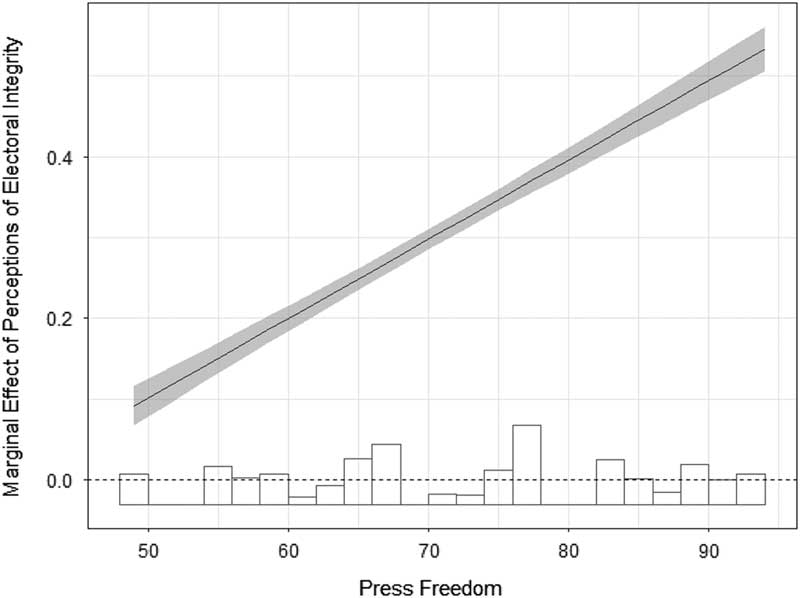

Figure 5 The Effect of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity on Incumbent Vote Intention, Depending on the Level of Press Freedom Note: The figure shows the estimated marginal effect of a one-unit change in perceptions of electoral integrity on incumbent support, conditional on the level of press freedom. All estimates and the 95% confidence interval are based on Model 4, Table 2.

Model 2 presents the results for a logistic regression model testing the moderating effect of partisanship on electoral integrity performance voting – that is, whether the strength of the link between perceptions of electoral integrity and vote varies for the two different groups of individuals (Hypothesis 2). In line with the second hypothesis, the interaction term between electoral integrity and partisanship presents a statistically significant negative coefficient. It means that the extent to which voters’ preferences are influenced by perceptions of electoral integrity is lower for partisan voters – who are expected to rely more on party cues when they assess the incumbent’s performance – while it has greater influence for those who declare they do not have any tie to a political party. Considering the predicted probability of voting for the incumbent government, when the perceived level of electoral integrity is low (with a value of 0 on a 10-point scale), the probability of voting for the incumbent is 32.4% for party-loyal voters and 21.0% for non-partisan voters. However, when there is a widespread perception of electoral integrity (the variable assumes its maximum value), the probability of voting for the incumbent government rises to 54.5% for partisans and 70.8% for citizens who do not belong to any political party.

In line with the extensive literature on retrospective performance voting, I hypothesized that in contexts where government clarity is higher, voters are more likely to assign responsibility for higher or lower levels of perceived electoral integrity (Hypothesis 3). Figure 4 plots the marginal effect of the key independent variable on vote intention for different levels of government clarity of responsibility presented in Model 3. The plot shows the existence of quite a strong ‘punishment behaviour’ of voters in contexts where government clarity is higher (a score of 1 on the scale), while the positive and highly statistically significant interaction coefficient suggests that the clearer the lines of government responsibility, the stronger the accountability link between performance and perceived electoral integrity. It is evident how strong performance voting is in contexts characterized by the presence of stable and cohesive governments: decreasing the level of electoral integrity perception by one unit in countries such as Taiwan, Ghana or Peru, in fact, decreases the probability of voting for the incumbent by ~5.7 percentage points. This effect is almost five times larger than the corresponding effect in ‘low clarity’ contexts (for instance, Romania or the Netherlands), where decreasing the level of electoral integrity perception by one unit reduces the probability of voting for the incumbent only by ~1.9 percentage points.

In Figure 5, finally, I plot performance voting conditional upon the level of press freedom. In line with the previous literature, I stated that contexts characterized by higher levels of press freedom – that is, where information about cases of electoral malpractice are available to citizens – performance voting is positively influenced (Hypothesis 4). The results in Model 4 confirm the hypothesis. While media freedom impacts negatively on the probability of an intention to vote for the governing party, it has a positive and statistically significant interaction coefficient. The marginal effect suggests that as media freedom increases, the quality of elections becomes more significant for voters’ decisions. Interpreting the results in terms of predicted probabilities, I found that in contexts in which pluralism and freedom of the media is lower (such as Pakistan), a decrease in the level of perceived electoral integrity negatively affects the probability of voting for an incumbent government party by ~1.6 percentage points. On the other hand, for countries scoring higher rates of media freedom (the Netherlands, for instance), decreasing the level of electoral integrity perception by one unit decreases the propensity to vote for the incumbent government by ~6.4 percentage points.

Robustness checks

Several robustness checks have been conducted to assess the reliability of the findings. Tables and coefficients are presented in the online Appendix. First of all, I re-run Model 1 using an alternative measure of electoral integrity to account for potential endogeneity biases in the main effect of individual perceptions on support for the incumbent government. To do so, I use the Perception of Electoral Integrity Index (PEI) 5.0 elaborated by the Electoral Integrity Project (Norris et al. Reference Norris, Martinez i Coma, Groemping and Nai2016) that is based on a survey of 2,961 experts providing evaluations of electoral integrity in 161 countries all around the world. Model 1A in Table A.4 shows that the results remain significant when the main independent variable – collected at the individual level – is replaced by the PEI index collected at the country level, thus confirming Hypothesis 1.

Moreover, Table A.5 in the online Appendix includes an alternative operationalization of the control variable capturing the national economic situation. Given the absence of an item measuring individual perceptions of the economic situation, I use a control at the country level. Unemployment is used instead of GDP growth or inflation because of its direct effect on citizens’ perceptions of the economy (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Ecker et al. Reference Ecker, Glinitzer and Meyer2016). I check this assumption by running two full models using such alternative macro-economic indicators. The results show the reliability of unemployment as a measure of economic evaluation.

In Table A.6 (Models 1B–4B) I replicate the original models with an alternative fixed-effects specification of clusters to control for the unobserved heterogeneity at the country level. According to Daniel Stegmueller (Reference Stegmueller2013: 758), in fact, maximum likelihood estimations might be more problematic in the presence of cross-level interactions, ‘even with 20 or more countries’, because of the low number of degrees of freedom at the country level. This means that the country-level estimators might suffer from omitted variable bias (Möhring Reference Möhring2012). The comparison between the coefficients confirms that all findings are robust to this alternative fixed-effect model specification.

Further, in order to account for variance in the dependent variable and to test the robustness of the findings, I also include a control for the level of democracy as measured by the Polity IV combined score for the year in question. The score ranges from −10 (autocracy) to 10 (full democracy). The results, presented in Table A.7 (Models 1C–4C) in the online Appendix, are in line with those presented in Table 2.

Finally, in order to exclude the possibility that cross-level interactions in Models 3 and 4 are driven by outlying cases, I re-run these models, removing one country at time. The results for the country-wise jackknife are presented in Table A.8. In this case too, the test does not affect the original findings.

Conclusion

Following a recent approach focused on the non-economic determinants of electoral accountability (Clark Reference Clark2009; Ecker et al. Reference Ecker, Glinitzer and Meyer2016; Singer Reference Singer2011; Xezonakis et al. Reference Xezonakis, Kosmidis and Dahlberg2016), this article aimed to understand the role of electoral integrity perceptions in shaping incumbent vote intention and how this link could be moderated by contextual characteristics. Considering 23 countries all around the world, I tested not only the direct impact of the perceived quality of electoral procedures on voters’ preferences, but also how this effect is moderated by specific individual- and country-level characteristics. First, I revealed the direct accountability effect of the key independent variable: voters use their perceptions of electoral integrity to punish or reward incumbents at the elections, almost in the same way that they use retrospective judgements on the national economy to express consent or dissent on incumbents’ performance (Becher and Donnelly Reference Becher and Donnelly2013; Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Reference Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier2007). Even though the economy still represents the main dimension of performance through which incumbent governments are evaluated, I showed that the way in which elections are managed contributes to structure voters’ electoral preferences. However, is this relation moderated in some ways by individual- as well as the country-level characteristics?

In line with research on economic voting (De Vries and Giger Reference De Vries and Giger2014; Kayser and Wlezien Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011), citizens’ partisanship confirms the relevance of its role in the attribution of responsibility and electoral integrity performance voting. Voters without any tie to political parties rely much more on perceptions of electoral integrity when they form their preferences, while partisans are more likely to be guided by their ideological predispositions. This represents an important finding: even in the presence of a cross-cutting, salient issue like electoral integrity, citizens tend to make their voting decision by relying most on their ‘partisan shortcuts’, leaving aside any short-term evaluation concerning this specific policy domain. This evidence has partial support in recent findings that show how individuals’ perceptions of election fraud are also heavily influenced by their own partisan attachments (Beaulieu Reference Beaulieu2014). However, one of the possible limitations of this article lies in the measure employed for partisanship, which does not distinguish between incumbent and opposition supporters, leaving room for further research on this specific aspect.

Following a consolidated approach to the study of electoral accountability (Anderson Reference Anderson2000; Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007), I also focused on the moderating effect of political context on performance voting. The clarity of the incumbent government affected the decisiveness of its impact on performance voting also in relation to perceptions of electoral integrity. With regard to the direct – or indirect – involvement of national executives in the organization and management of elections, voters seem to consider them responsible for higher or lower levels of electoral integrity. Cohesive and stable governments make voters able to identify who is responsible for problems concerning vote count, gerrymandering or competition that might arise during the electoral process. Therefore, the threat of retrospective voting should also persuade incumbents to approve legislation to prevent any kind of problem even indirectly connected with the management of elections.

Finally, I showed that electoral accountability in relation to perceptions of electoral integrity is not independent of the freedom and plurality of information available to citizens. The mass media have a recognized gatekeeping role that works as a powerful watchdog to inform the public and strengthen the transparency of the electoral process, revealing any potential distortion (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Golden and Hill2010; Costas-Perez et al. Reference Costas-Perez, Sole-Olle and Sorribas-Navarro2012). Results presented in this article confirm this evidence, showing how contexts characterized by a relatively independent mass media have a strong and positive influence on the link between electoral integrity perceptions and voters’ preferences. I confirmed that for electoral integrity too, the existence of plural and free media has positive consequences in terms of strengthened accountability, since it guarantees that a constant amount of information about the transparency of the electoral process is available to the public. More information, in turn, creates a ‘virtuous circle’ that contributes to enhancing the government’s clarity of responsibility and, more broadly, the quality of democracy.

In conclusion, these findings have important implications for the study of democratic quality and, specifically, for electoral accountability. As a large amount of research shows, the economy is the most important predictor of voters’ behaviour. However, this study contributes to the literature by enlarging the perspective of performance voting to the non-economic determinants of government accountability. I showed the efficacy of other factors, in this case individual perceptions of electoral integrity, that promote electoral accountability in several countries worldwide. The results also demonstrated that this relation is moderated by specific contextual factors, partly considered by the literature on economic voting. The clarity of responsibility of a current government and the degree of freedom of the media demonstrate their power to strengthen the link between perceptions of electoral integrity and vote. Future comparative research on performance voting should investigate further non-economic dimensions – at the individual as well as at the country level – able to influence voters’ capacity to reward or punish incumbent governments in the elections.

Supplementary material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please go to: https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.13.

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was carried out at the Department of Government and International Relations of the University of Sydney and supported by the Electoral Integrity Project Grant for Visiting PhD Students (February–June 2016). The author thanks Alessandro Nai, Pippa Norris, Mark Franklin and the two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions on previous versions of this work.