No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

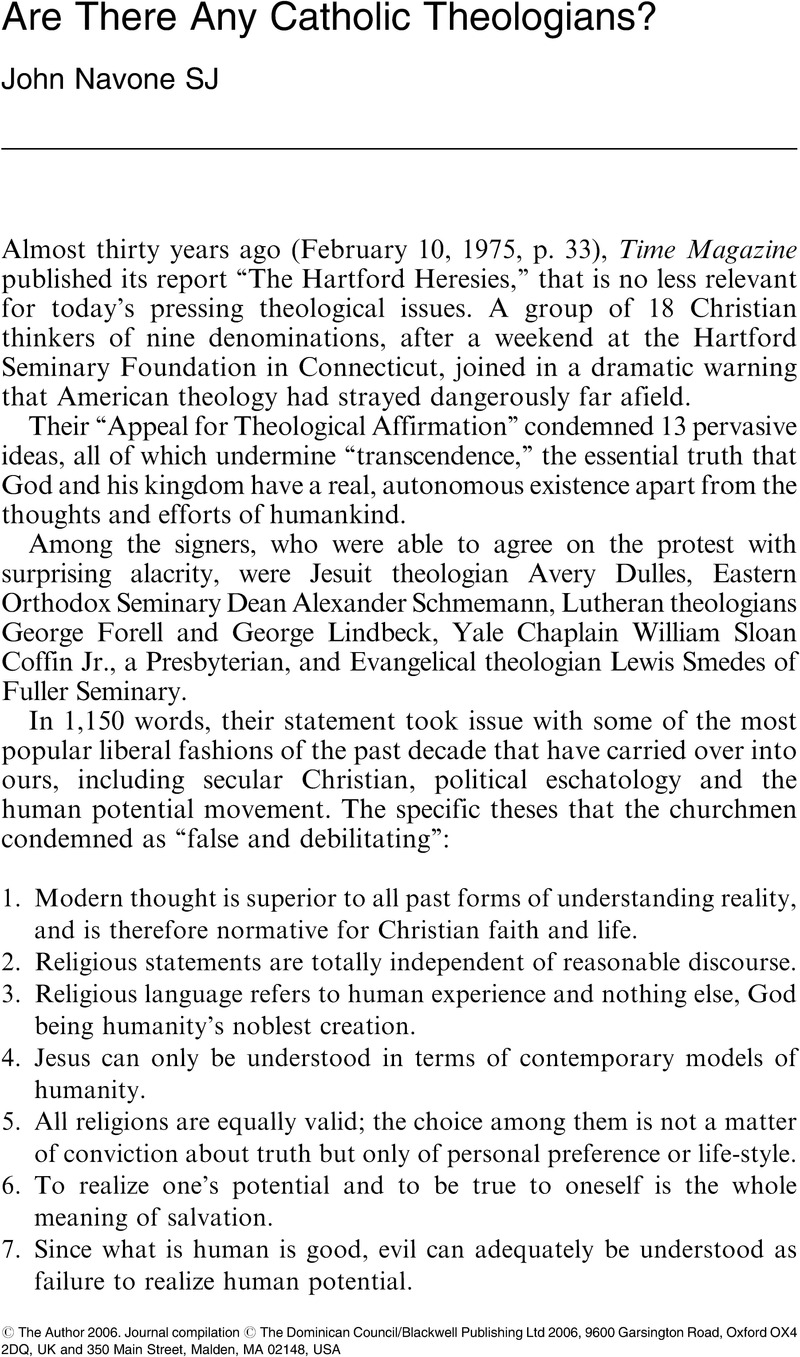

Are There Any Catholic Theologians?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2024

Abstract

- Type

- Original Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- © The Author 2006. Journal compilation © The Dominican Council/Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA