The renowned Berlin Turfan collections of manuscript fragments were obtained in the early twentieth century by four state-funded German expeditions active in the Turfan area (modern-day Turpan, Xinjiang) between 1902 and 1914.Footnote 1 Towards the end of the Second World War, however, the Turfan collections, as with many other antiquities held in Berlin institutions, were moved and hidden for safekeeping. Although the vast majority of text fragments and objects from Turfan were recovered after the war with little or no damage, a few dozen fragments – a remarkably small percentage – were damaged or lost altogether.Footnote 2

When, after the war, the Turfan fragments could be recovered and gathered together again under the aegis of the Orientalische Kommission, then the Institut für Orientforschung, in Berlin, efforts were made to begin reorganizing and cataloguing the Turfan collections, especially the texts in Iranian languages (Boyce Reference Boyce1956; Boyce Reference Boyce1960: xxiv–xxviii). Prior to the war, the fragments had not been consistently numbered or catalogued, and many had lost their labels and signatures as a result of moving, storage, and vandalism during the war. In order to proceed, all the known pre-war photographs of fragments were first brought together and compared. These were: the Orientalische Kommission's own photos; a set made for F.W.K. Müller (1863–1930), returned to the Orientalische Kommission upon his death; a set made for F.C. Andreas (1846–1930) and kept in Göttingen; a set made for W. Lentz (1900–86), kept in Hamburg; and the particularly extensive and carefully organized set of Walter B. Henning (1908–67), then in London. Mary Boyce (1920–2006), who was entrusted with the initial cataloging of the Iranian fragments, recounts that all these photos were gathered in Berlin in 1953, together with Lentz’ card-catalogue and other, older, lists and transcripts. Efforts were made to maintain consistency with the older numbers already used in publications. Then, a new signature system for the Iranian fragments in Manichaean and Sogdian scripts was developed by Boyce, Henning, and Lentz, and the use of an “M” prefix for the former group of fragments was standardized (Boyce Reference Boyce1956: 317–8; Boyce Reference Boyce1960: xxv–xxvii). Boyce's catalogue of the fragments in Manichaean script was published in 1960. At this point in time, the Orientalische Kommission in Berlin held two sets of photographs, while Andreas’ photos were held in Göttingen, and Lentz's photos and card-catalogue were returned to Hamburg. Henning's photographs returned to his possession in London and he later took them with him Berkeley, where scholars lost track of them upon his death in 1967.

In 1992 Christiane Reck took up the cataloguing of the remaining Iranian fragments in Sogdian script under the auspices of the major Germany-wide project Katalogisierung der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland. “So” or “Ch/So” prefixes were added to the fragments in Sogdian script, and those fragments which were unnumbered were numbered from 20000 up (Reck Reference Reck2006: 11–12). Reck completed the cataloguing of the fragments in Sogdian script in 2015 and the results were published in three volumes (Reck Reference Reck2006; Reference Reck2016; Reference Reck2018). At about the same time, Nicholas Sims-Williams completed the cataloguing of Iranian-language fragments in Syriac script (2012). These recent catalogues, together with that of Boyce, cover essentially all of the Turfan fragments in Iranian languages, excepting those in Brahmi script (Khotanese, Tumshuqese, and Sogdian). Although these scholars were able to recover much information about lost fragments by means of the older photographs, quite a few fragments remain lost or unknown, with no photographs or other information available for them.Footnote 3

Fortunately, it is now possible to recover an additional number of the remaining lost or unknown fragments in Iranian languages – mostly Sogdian – with reference to the numerous photographs preserved in the Nachlass of Walter B. Henning.Footnote 4 The Nachlass shows that Henning in fact had two sets of Turfan photographs: an older set made in the 1930s consisting of nearly all the Iranian fragments in Manichaean and Sogdian scripts; and a newer set made in the 1960s consisting of a limited number of fragments in Manichaean script only.Footnote 5 In the present inquiry after lost manuscript fragments, the older set is naturally the more useful.

Lost Turfan fragments for which a photo is present in Henning's Nachlass fall into two categories: i) fragments which still exist, but which are now stored under a different number than they were originally, resulting in references in older publications to fragment numbers which do not correspond to any current numbers; and ii) fragments which appear actually to have been lost. Both groups will be described in the following, with select photographs provided.Footnote 6

There are, in addition, some lost fragments for which there does not seem to be a photo in Henning's Nachlass. About two dozen, both extant and lost, are represented in the Nachlass only by paper cards. It is not clear whether these cards indicate that the fragments were already unavailable at the time Henning obtained his photos, or that he subsequently loaned out his photo, but it was never returned. For example, the fragments So 14109 and So 14110, both assumed lost, are represented only by a small card with their number on it.Footnote 7 But the card for the lost fragment So 15250 bears not only the shelf number but also a short note “to Fleming”.Footnote 8 In addition, a number of extant fragments are also represented only by cards with the note “L's catalogue”, presumably referring to the list of Wolfgang Lentz's list in Hamburg.Footnote 9 Finally, though there are some photos of Christian Sogdian fragments in the Nachlass, there do not appear to be any of the lost ones among them.Footnote 10

1. Fragments now catalogued under a different numberFootnote 11

10712/10713

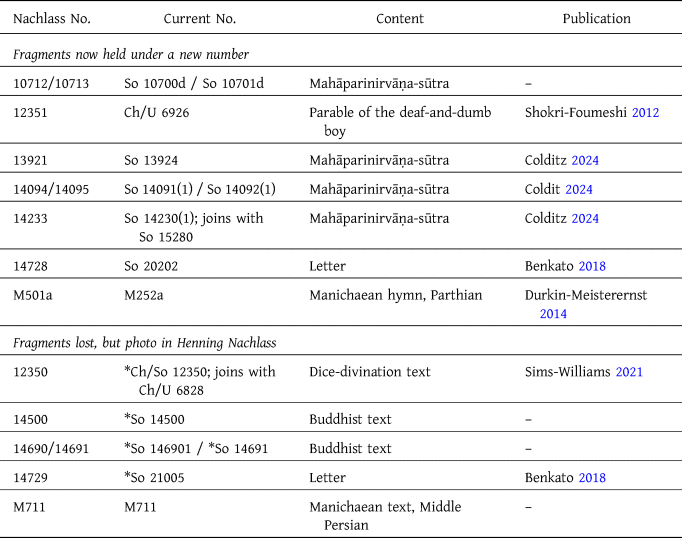

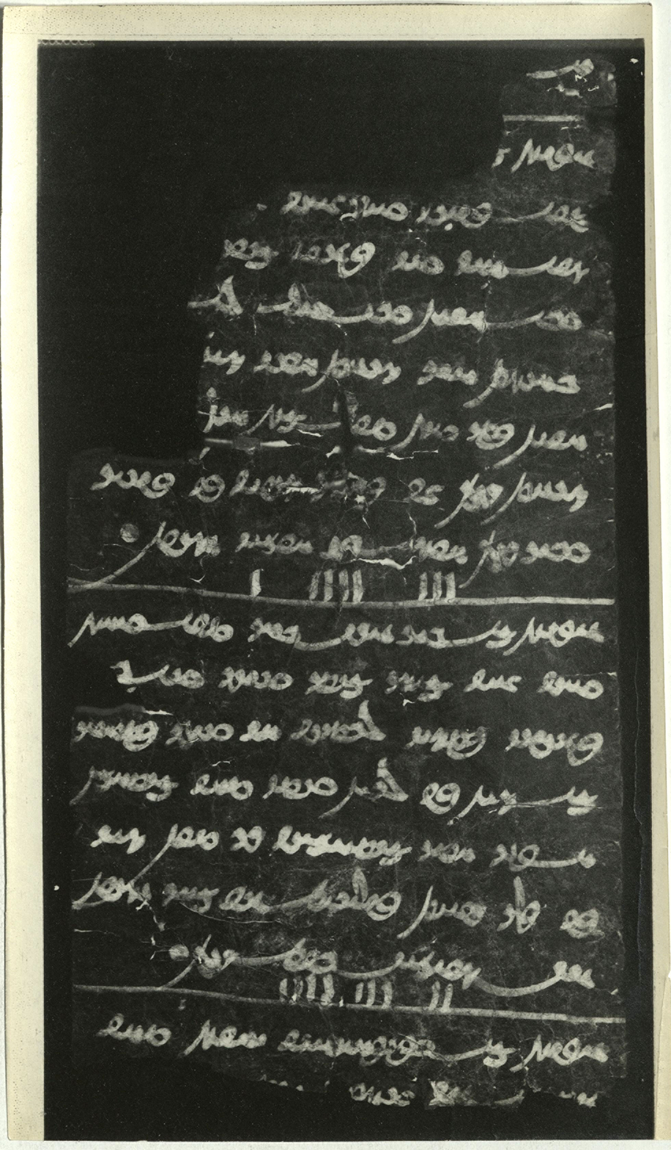

No fragments with these numbers currently exist. Utz (Reference Utz1976: 3) referenced these numbers based on the Hamburg lists, assuming – incorrectly, as Sundermann (Reference Sundermann and Irisawa2010: 82 n. 12) was to note– that the originals were held in then-east Berlin. In her catalogue, Reck confirmed that no such numbers existed, but noted that the Hamburg index card with these signatures also contained the following remark, which was not to be found on any extant glass plate in the Berlin collection: “Ein zweiseitig, ein einseitig beschriebener Fetzen aus ders. Hs. Zum unteren Auf der Glasplatte Notiz: ‘Sogdisch, wie mir ein alter Chinese auf den Ruinen gesagt hat’” (2016: 15). She suggested that the remark could apply to the extant fragments So 10700d and So 10701d, which are at present glassed together (Reck Reference Reck2016: 101–2). The photographs from the Henning Nachlass confirm Reck's intuition and show the fragments’ older glass plate, which displays the exact remark cited on the index card, in addition to another handwritten note “Soghdisch” (Figure 1). Both fragments contain text attributed to the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra and will be published by Colditz (Reference Colditz2024).

Figure 1. So 10712 (now So 10700d), above, and So 10713 (now So 10701d), below, Side I

12351

There is no extant fragment with this number. Reck (Reference Reck2018: 80) noted that the Hamburg list mentions both a 12350 (on which see below) and a 12351, with find-signatures T II 1255 and T II 1256, respectively, but lamented that “Das in der Liste als *(Ch/So) 12351 geführte Fragment bleibt bisher vollständig verschollen”. In Henning's Nachlass, photos of a fragment numbered 12351 are preserved. Comparison with the existing fragments in Berlin showed that this fragment is the same as that bearing the number Ch/U 6926 at present (with slightly different T II 1456 find-signature).Footnote 12 On the photograph, Henning had noted the transcriptions of a handful of words, with the reading of two additional words (“4 ʾBYw ʾnyw”) on the back of the photo. As Ch/U 6926, this fragment was catalogued by Reck (Reference Reck2006: 283). It contains another copy of the “Parable of the Deaf-and-Dumb Boy”, corresponding to the St Petersburg fragment L69 verso, lines 12–19, with slight differences.Footnote 13 The text of Ch/U 6926 was edited and published in Persian by Shokri-Foumeshi (Reference Shokri-Foumeshi2012: 48–9). It is worth mentioning the following modest corrections to his readings: line 4 read mʾth for mʾt, line 5 read δβʾmpnh for δβʾmpnwh.Footnote 14

13921

A fragment with this number was also referenced by Utz (Reference Utz1976: 3) with the remark that an original was no longer known. In her catalogue, Reck simply noted this number in her list of signatures lacking corresponding extant fragments (2016: 446). In the photo from Henning's Nachlass, 13921 is glassed with two other fragments, numbered 13920 and 13922. All three fragments are still extant, but now under the numbers So 13923, So 13924, and So 13925 respectively. Now bearing the number So 13924, this fragment is unpublished, but was described by Reck (Reference Reck2016: 137–8). The find signature of “T II D 63” can be confirmed, as it is present on the label of the glass plate shown in Henning's photo, though not written on the fragments themselves. The fragment contains text from the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra and will be published by Colditz (Reference Colditz2024).

14094/14095

Like the above, these two numbers do not occur on any extant fragments in the Berlin collection. Both were referenced by Utz (Reference Utz1976: 3) with the remark that photographs were preserved in Hamburg, though this is not the case. Reck (Reference Reck2016: 446) also noted that fragments under these numbers did not exist, but subsequently identified these numbers with the extant fragments So 14091(1) and So 14092(1), respectively, without further comment (2018: 195). This identification can be confirmed by the photos in Henning's Nachlass, which show a glass plate of three fragments labelled 14094–96 on the back. A label with the find-signature T II D 89 is at the upper-right. The third of these, 14096, is Old Turkic and is now numbered So 14093(1). According to Utz and Sundermann (as cited by Reck Reference Reck2016: 145), the fragments contain part of a Sogdian version of the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra, together with about 80 other fragments (Reck Reference Reck2016: 26–7). Both fragments will be published by Colditz (Reference Colditz2024).

14233

A fragment with this number was also referenced by Utz (Reference Utz1976: 3) with the remark that an original was no longer known. In her catalogue, Reck simply noted this number in her list of signatures lacking corresponding extant fragments (2016: 446). A comparison of the photo preserved in Henning's Nachlass with the extant Berlin fragments, however, revealed that 14233 is the same as the fragment now known as So 14230(1), which joins directly with So 15280 (for information on both, see Reck Reference Reck2016: 150–1). Both belong to the same manuscript of the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra as the previous two fragments, and will be published by Colditz.

14728

There is no record at all of any Turfan fragment with this number, but comparison with extant fragments revealed that it is currently preserved under the number So 20202. It must have been re-glassed and given a new number after the war. Some notes about the fragment are preserved in the Nachlass of Lentz (Reck Reference Reck2006: 237), although already under this second number. As So 20202, the fragment was edited and published in Benkato (Reference Benkato2018: 23–4), where it was mentioned that the find-signature of T II T noted by Lentz was no longer visible on the fragment. In Henning's photo a label with find-signature of T II T is visible at the upper right; this must have been lost together with the original glass plate. The text is a fragment from the middle of a letter, containing some formulae from the body, with the verso containing some address details and evidence of a complex folding pattern (Benkato Reference Benkato2018: 59–62).

M501a

There is no fragment currently bearing this number. In preparing her catalogue, Boyce notes that she was able to consult Henning's photo, describing the fragment as “Scrap, words and letters only…Parth., probably Psalms” (1960: 34). Comparing Henning's photo with the extant Turfan texts, it can now be seen that M501a is identical with the extant fragment M252a. Strangely, this identification was overlooked by Boyce, who catalogues M252a separately, though with nearly the same information as for M501a (1960: 17). As M252a, the fragment has now been edited by Durkin-Meisterernst (Reference Durkin-Meisterernst2014: 378).

§2. Lost fragments with photo in Nachlass

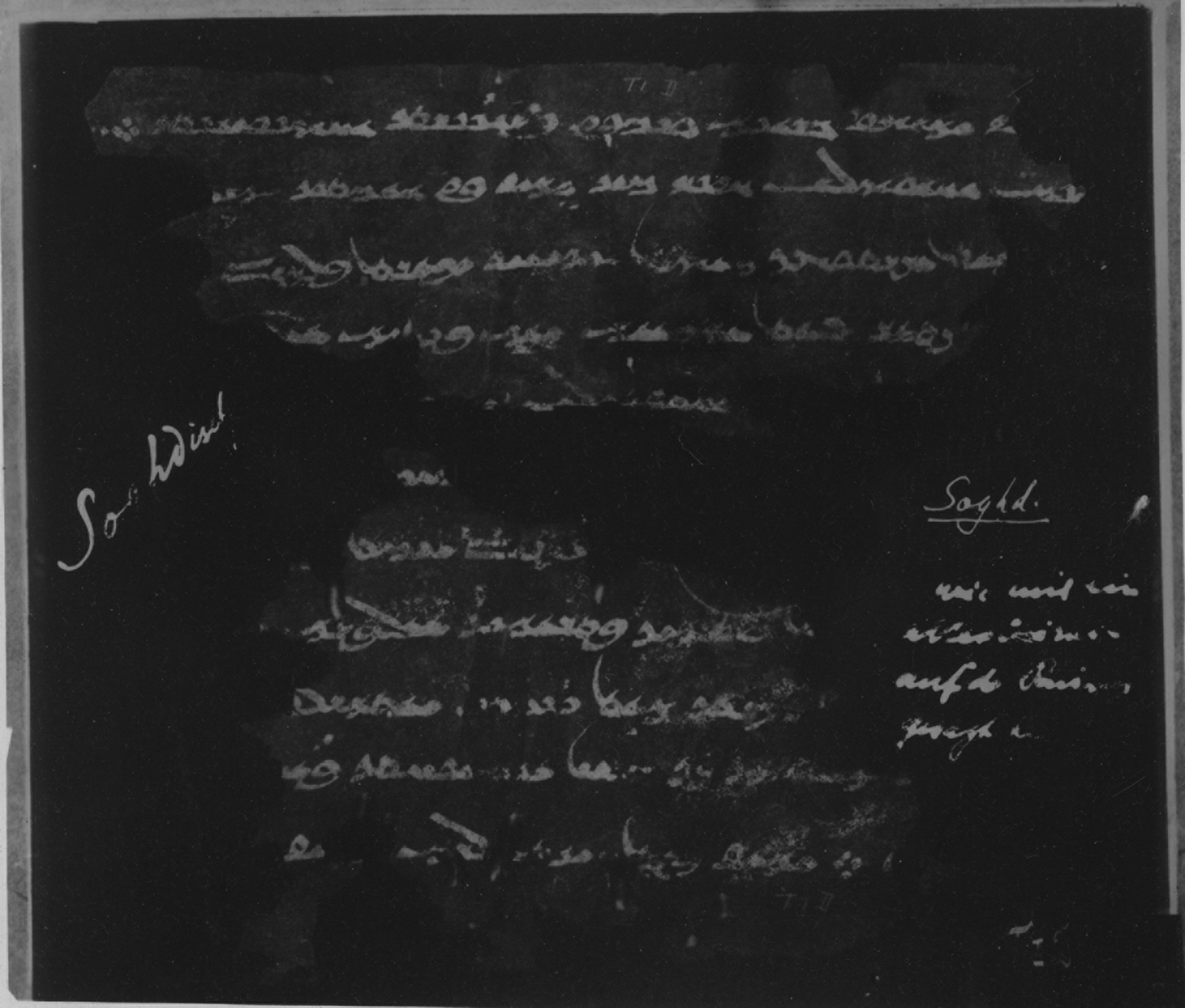

Figure 2. So 10123, Side I

Figure 3. So 10123, Side II

There is no extant fragment with this number. In his grammar, Gershevitch cited a few forms from “10,123” and “10.123” with find-signature T i α (Gershevitch Reference Gershevitch1954, §§115, 1111), and in the Hamburg list 10123 is described as a long sheet with 21 lines of Buddhist Sogdian with the note “prsnʾyc γwtʾw = Prasenajit” (Reck Reference Reck2016: 45). Henning also cited a few words from this text, referring to it only as T i α. In Henning's (Reference Henning1940: 62) Nachlass, photographs of both sides of 10123 are preserved, both bearing the find-signature T i α. On the back of the photo of side II is the handwritten note “prsnʾyc γwtʾw = Prasenajit”, while the back of the photo of side I simply reads “Prasenajit”. These facts, together with the text itself, confirm that it is indeed the 10123 / T i α of the older publications. The fragment is a short-lined pustaka leaf, rather torn around the edges, with mostly complete lines of text per side in the formal script. King Prasenajit (prsnʾyc xwtʾw) and and his son Prince Jeta (zyt) are both mentioned multiple times in the text.Footnote 15

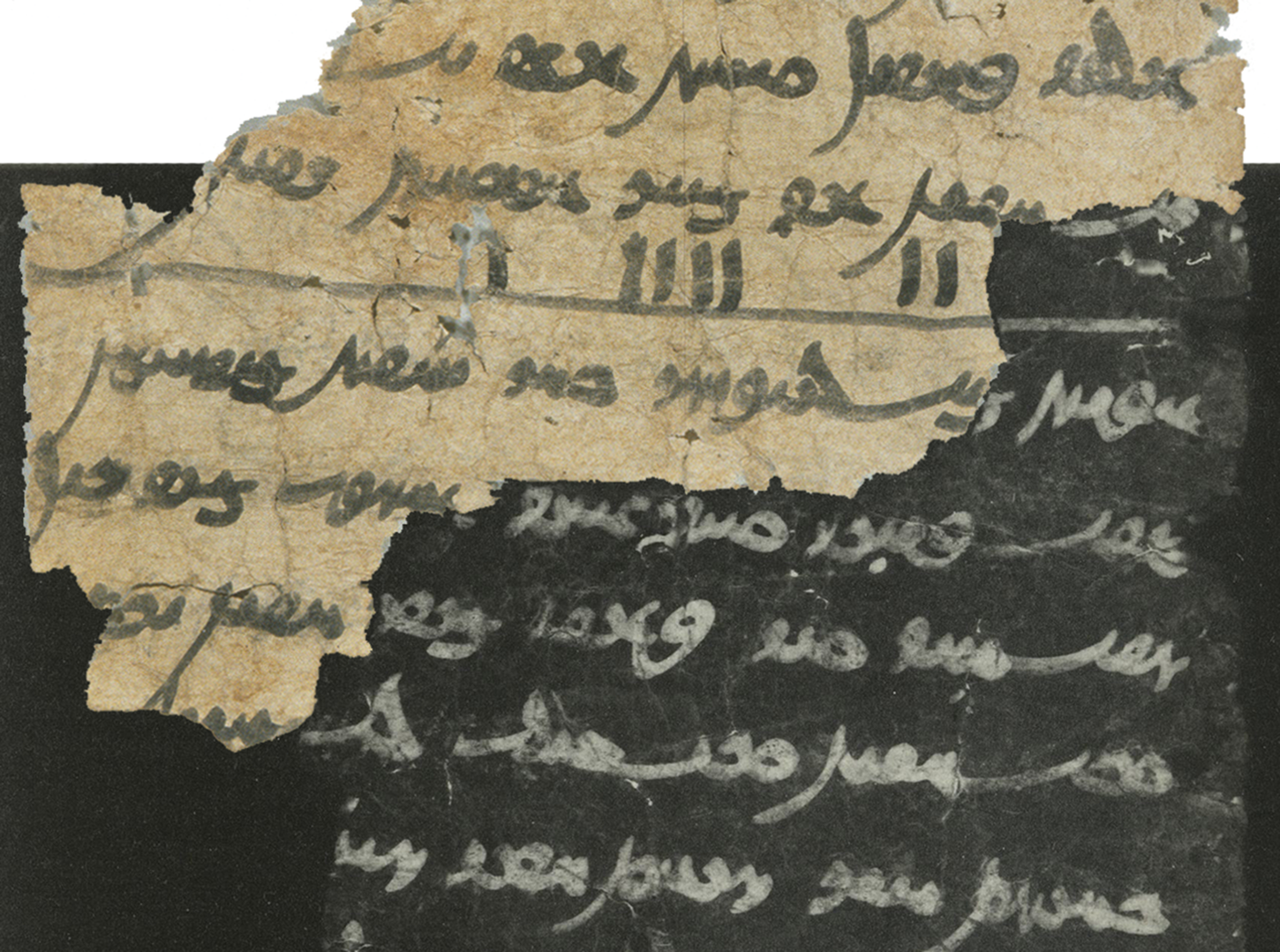

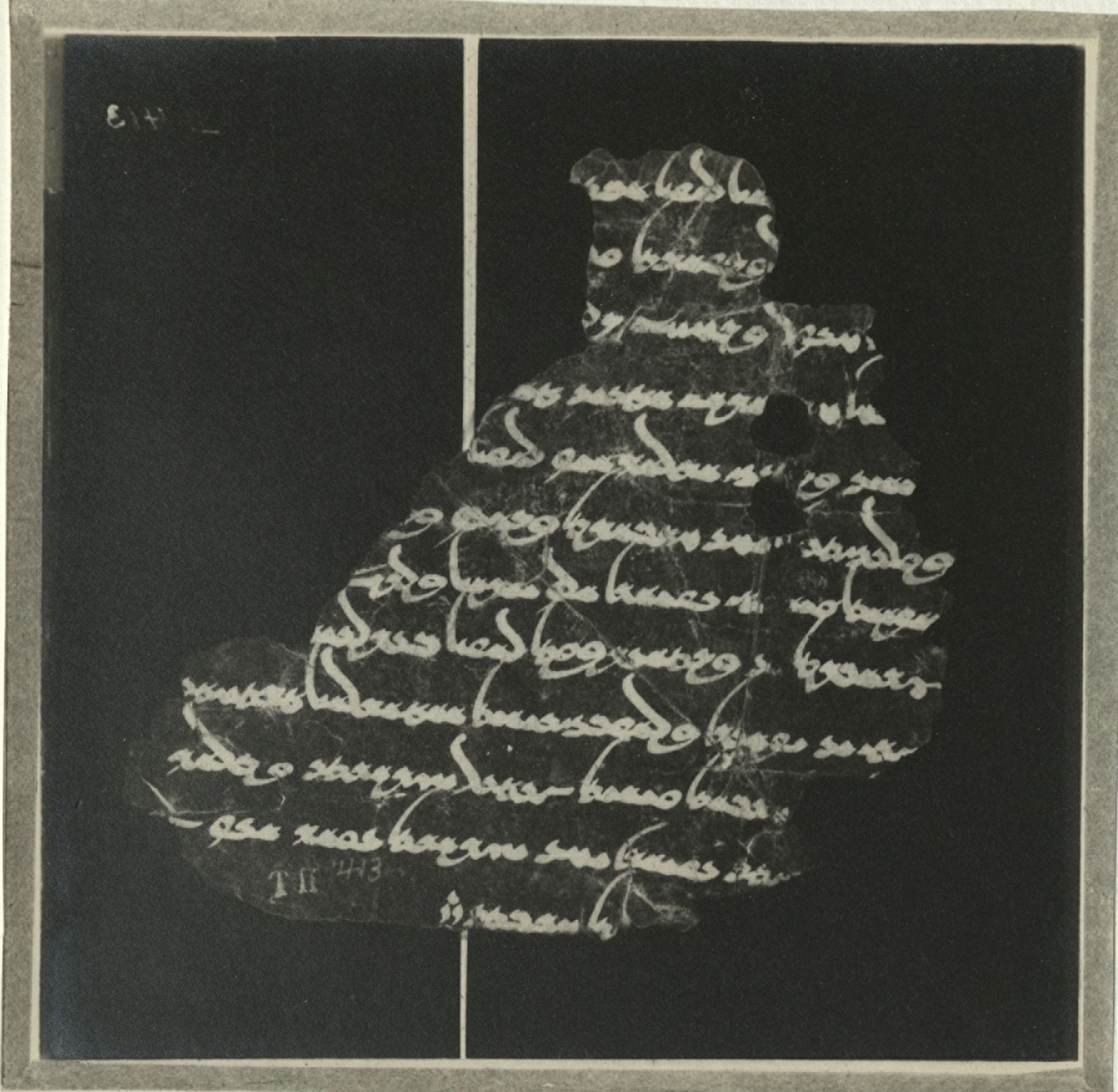

Figure 4. Ch/So 12350, verso

Figure 5. Ch/So 12350, recto

There is no extant fragment under this number. Two transcriptions of this fragment were preserved, one in a notebook of Mark Dresden currently in the possession of Hiroshi Kumamoto and one among the papers of Ilya Gershevitch held at the Ancient India and Iran Trust in Cambridge. From Dresden's notebook, Yoshida prepared a copy of the transliteration of the text, which Reck later published in her catalogue (2018: 80–81). It seems that both of these transcriptions may go back to Henning, whose Nachlass contains not only a photo of both sides of 12350, but also a handwritten transcription which is essentially the same as that published by Reck; it is possible that the versions of both Dresden and Gershevitch are copies of this transcription.Footnote 16 On the back of the photograph of the verso, one can see the find-signature “T II 1455” and the handwritten notes “βny’’k = Vināyaka?” and “upāpa gandarawa [sic]”.

The fragment, now known as *Ch/So 12350, contains a dice-divination text, which Sims-Williams (Reference Sims-Williams2021) cleverly recognized as joining directly with the extant fragment Ch/U 6828 (see Figure 6) in his recent edition of both texts. There is little to add to his edition despite its being based on an old transcription, the quality of which can be confirmed with reference to the photograph.

Figure 6. Ch/U 6828 + Ch/So 12350, verso, montage of join

In line 10 of the joined text (equivalent to line 4 of 12350), one could correct prʾyw to prẓβr “simile, likeness” as there appears to be a dot under the third letter. In line 11, Sims-Williams's suggestion of *mywy at the end of the line can be confirmed, as myw(y) is visible. At the end of line 14, there is probably only enough room to restore zʾry. In line 15, it is difficult to improve the p(…)y-skwnw of the transcriptions, as the fragment is crumpled and torn at this spot. The traces might allow for a reading p(ryʾ)y-skwnw, giving the phrase “whatever you are suffering, you will be without pain”. Perhaps there is an intentional repetition of pryʾy (both n. “pain” and 2sg.pres. “you suffer”) in this line; what seems to be an intentional pun occurs with γwnʾ some lines prior (Sims-Williams Reference Sims-Williams2021: 83). In line 16, read γwš(ʾ), 2sg.impv. “rejoice!” rather than the γwš of the old transcriptions; the aleph is indeed partially visible. It is also followed by a punctuation mark not noted in the older transcriptions. There are a few more traces visible on line 27 than are apparent from the transcriptions, though they do not contribute much to the reading of the text: (…t) xw wys(p)[w](…)[.

The Nachlass also contains a photograph of the previously unknown recto of *Ch/So 12350, which contains Chinese text with six lines of Sogdian. These lines seem to include one or two ownership or readers’ notes.Footnote 17 The text of the recto, which can be joined nicely with the text of the recto of Ch/U 6828 edited by Reck (Reference Reck2018: 111), is as follows (see Figure 7):

Figure 7. Ch/U 6828 + Ch/So 12350, recto, montage of join

*Ch/So 12350 + Ch/U 6828, recto

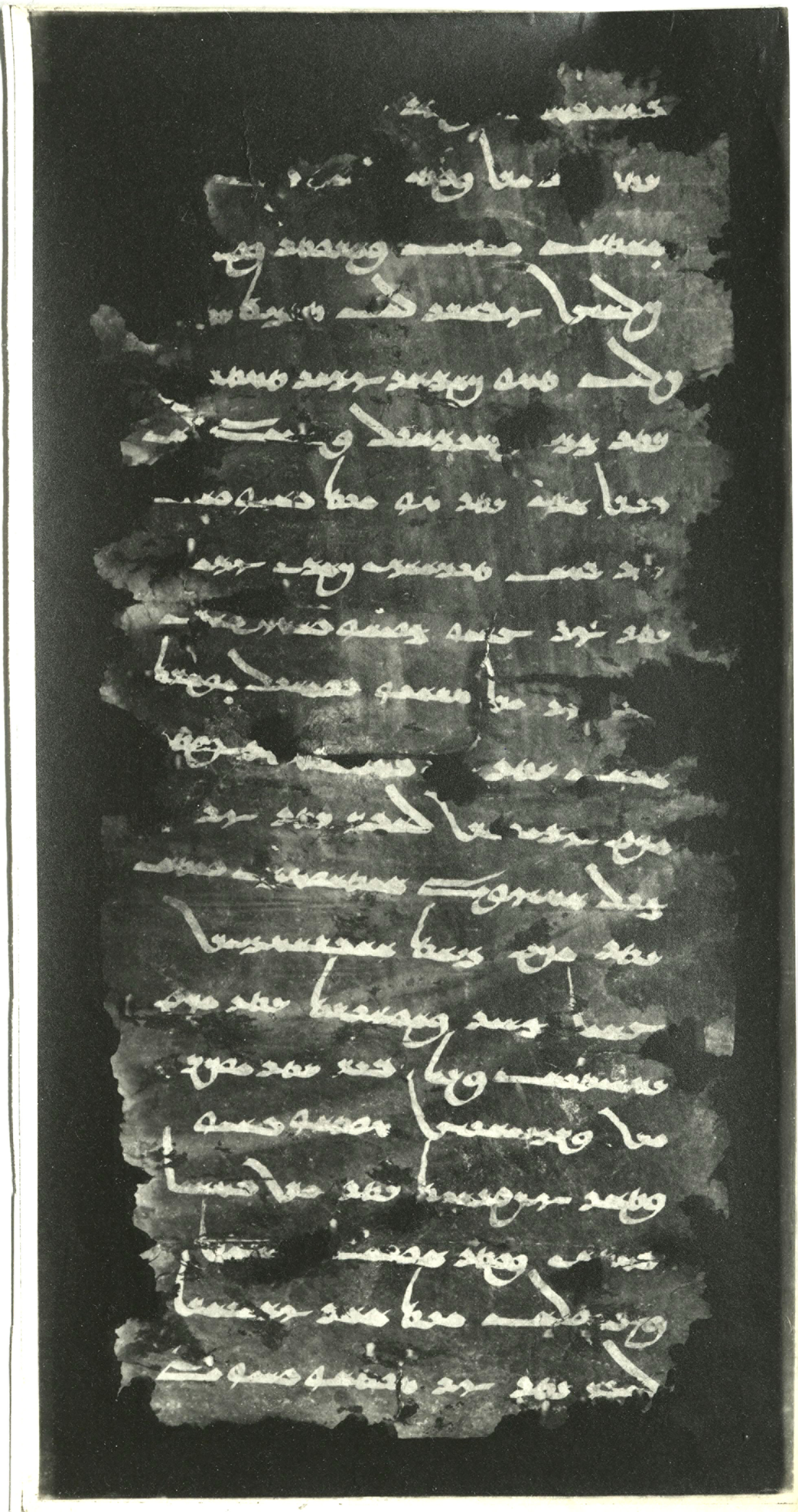

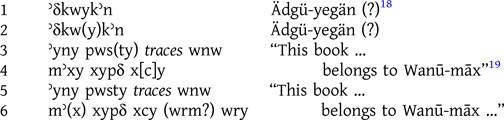

Figure 8. So 14500, Side I

Figure 9. So 14500, Side II

No fragment with this number is currently known, and there is no available photo or full transcription. As Reck relates, Gershevitch cited a text with the find-signature T II D 413 in his grammar, and a Hamburg index card for 14500 includes the same find-signature. Meanwhile, Gershevitch's own index cards contain the phrase he cited with the reference “S25,2”, which Sims-Williams located in Gershevitch's notebook in Cambridge (Reck Reference Reck2016: 163). This notebook contained two transcribed lines attributed to “T II D 413 b”. That this T II D 413 and 14500 do refer to the same fragment can now be confirmed by the photograph in Henning's Nachlass; the photos and handwritten numbers on the back only give a find-signature of T II D 413. (So) 14500 is a two-sided fragment from a pothi-leaf written in the formal script, containing parts of 12 lines on each side. Gershevitch's transliteration cited by Reck is of Side 2, lines 8–9, a phrase containing reference to Śrāvakas and Pratyekabuddhas.Footnote 20 Side 1 contains the word rnkʾ multiple times.Footnote 21

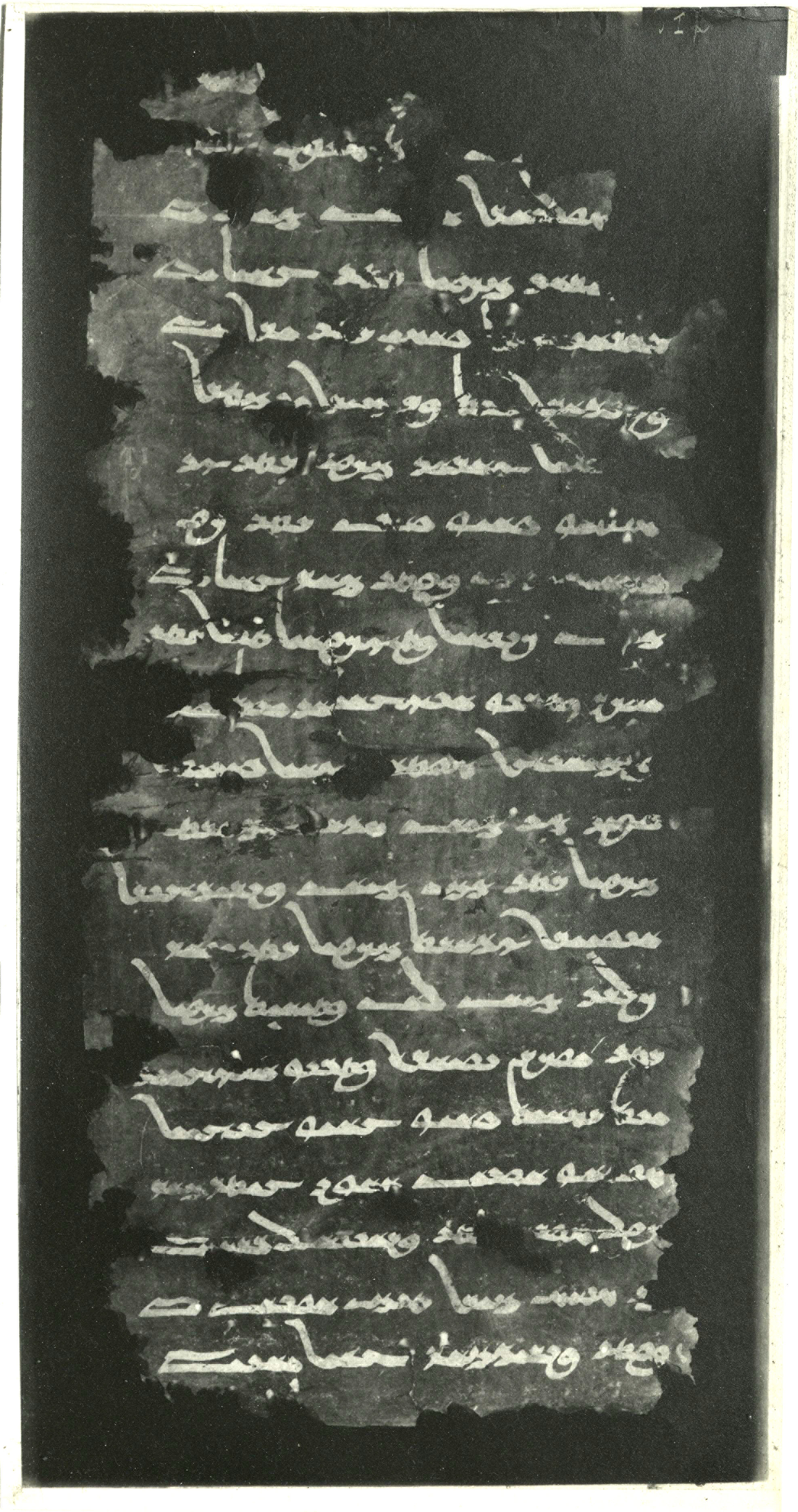

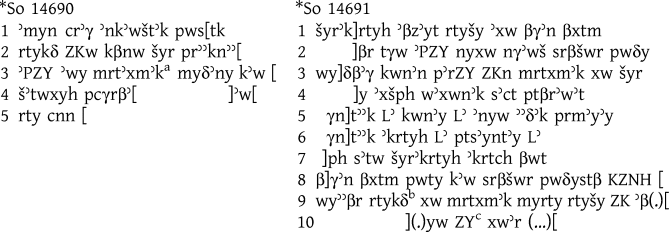

14690/14691 (Figure 10)

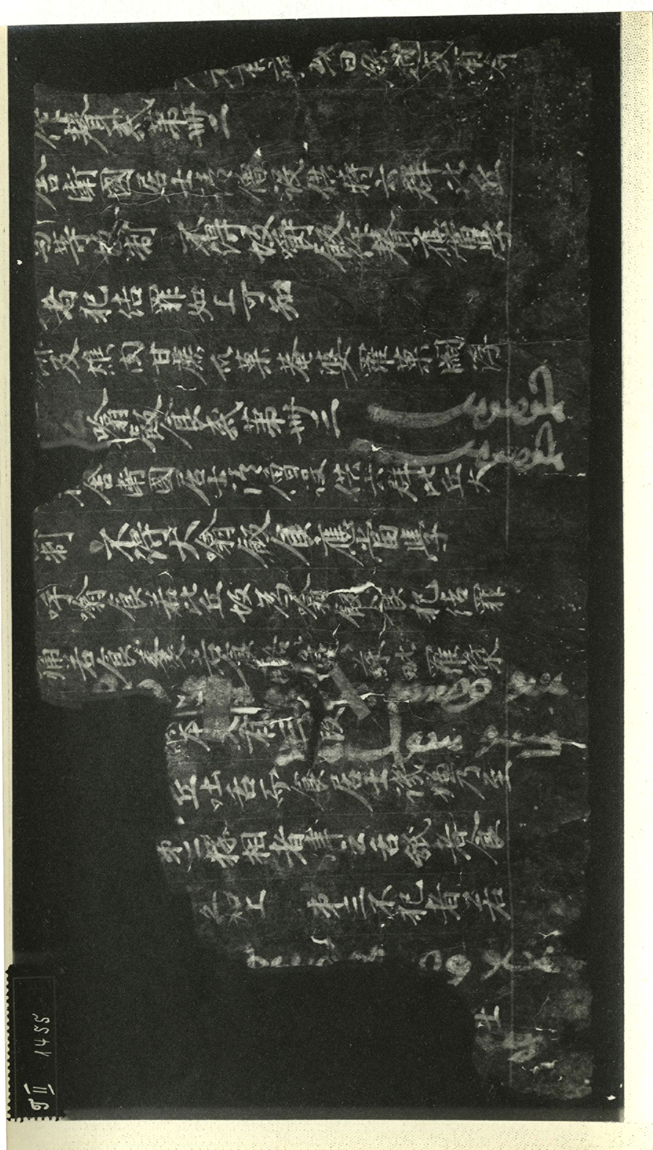

Figure 10. *So 14690 recto (top-right) and *So 14691 recto (bottom-left)

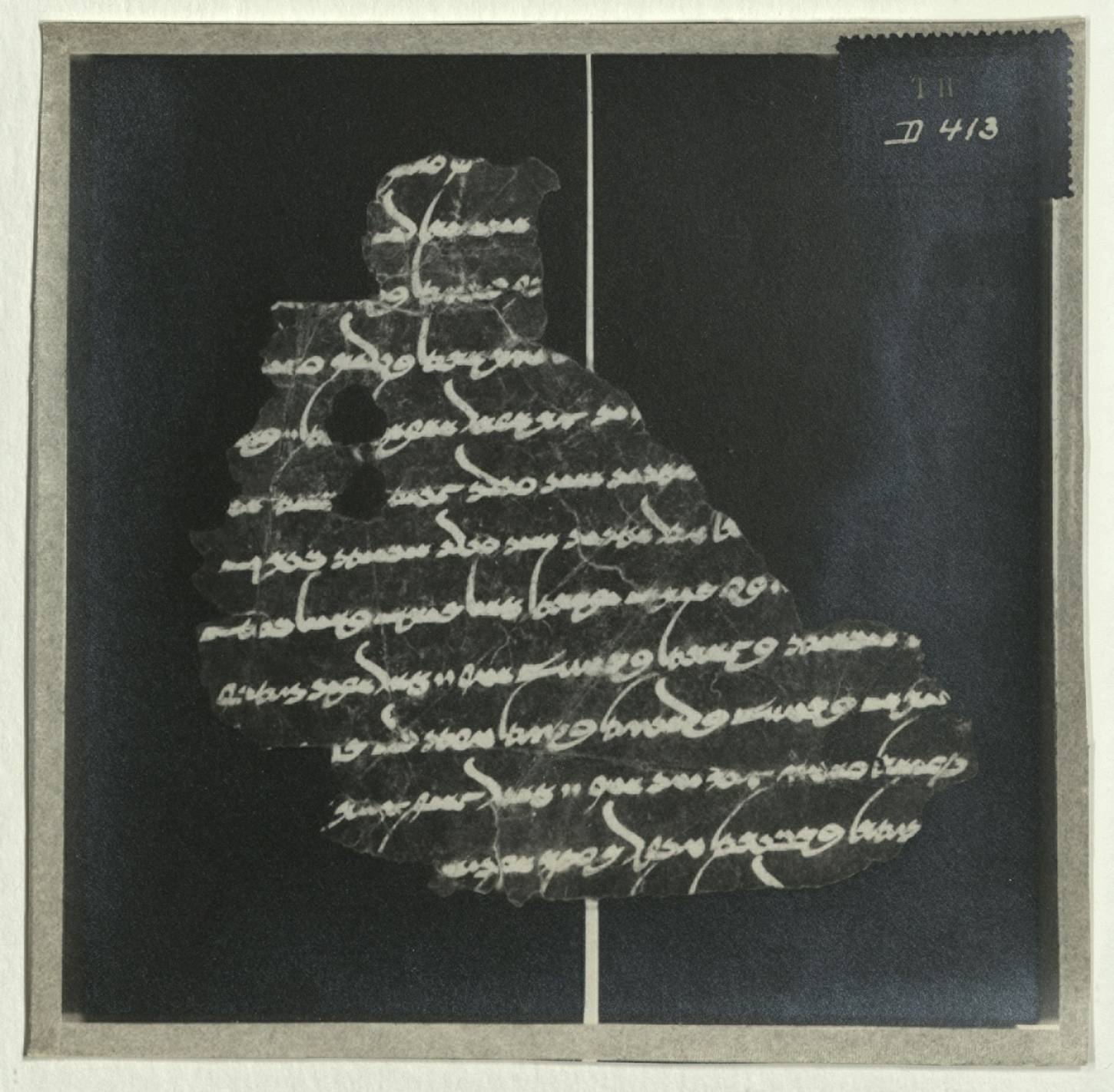

No fragments with these numbers are currently known. Though photos were not available, a transcription of each fragment is preserved in the Nachlass of Lentz in Hamburg. Reck (Reference Reck2016: 178–9), who reproduces the transcriptions of both fragments under the updated numbers *So 14690 and *So 14691, noted that their text did not match any existing fragment. It therefore seems that the fragments are actually lost, but, fortunately, Henning's Nachlass contains photos of both. The two fragments are arranged together in a glass plate bearing the label “T II Š [or S] 23”, while *So 14690 has “Š 23” written directly on it. On the back of the photograph (there is no photograph of the fragments’ verso sides), Henning wrote the find-signature “T II Š 23” and a note “Srβšwr pwδystβ (Sarvaśūra, e.g. Sanghāṭasutra in Saka)”. Indeed, Reck also suggested that the text could be a rather free adaptation of the part corresponding to §136 of the Khotanese version, roughly equivalent to T.T. 423, 13, 966b20–27. While Reck had suggested that *So 14690 and *So 14691 might belong to the same manuscript as So 16120, also containing part of the Saṃghāṭa-sūtra, examination of the photos shows that the fragments are written in a rather different hand to So 16120 and are not likely to be from the same manuscript.

The transliteration of Lentz published by Reck (Reference Reck2016: 179) with some restorations and corrections is largely accurate. It is worth reproducing with a few additional corrections:

a Sic, not Lentz's mrtxmʾk b Lentz rtkδ c Omitted by Lentz

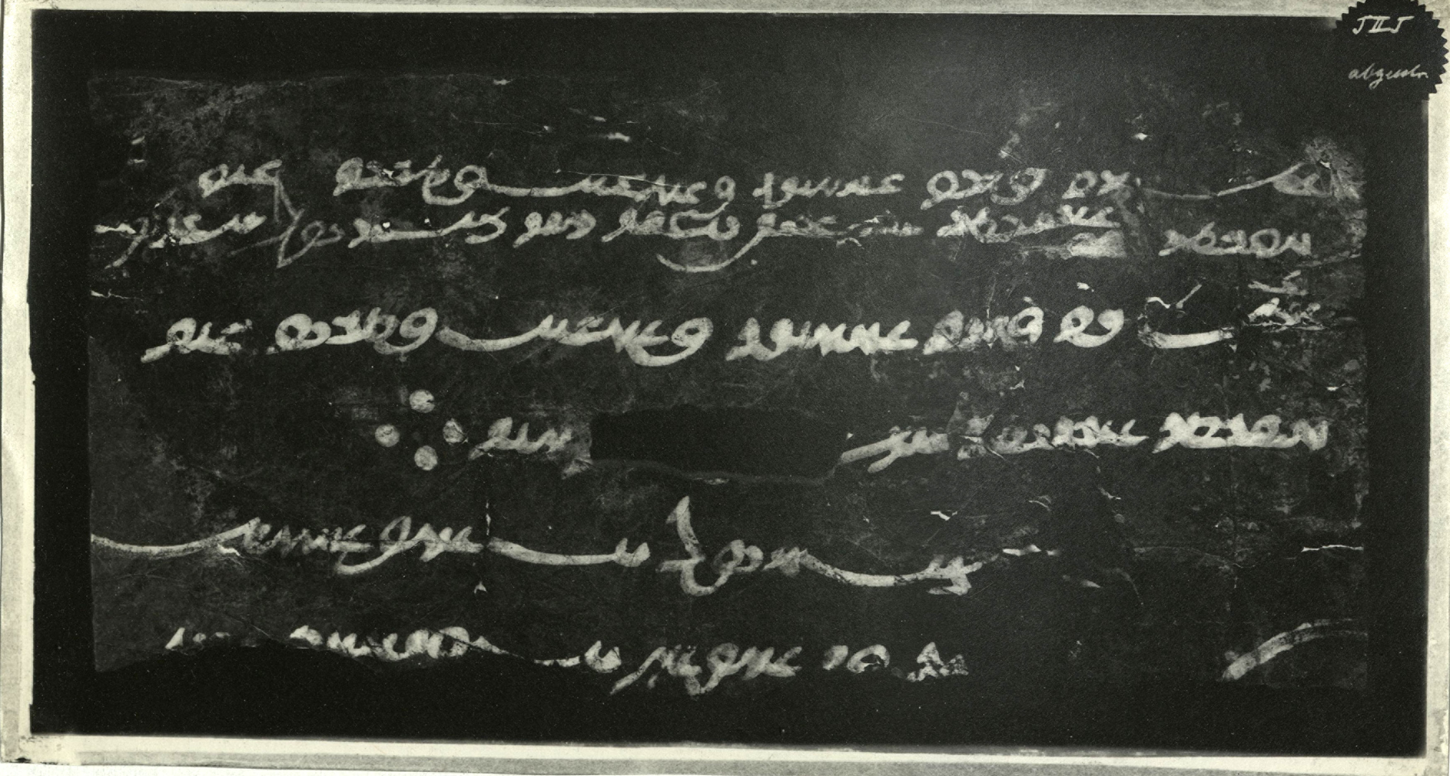

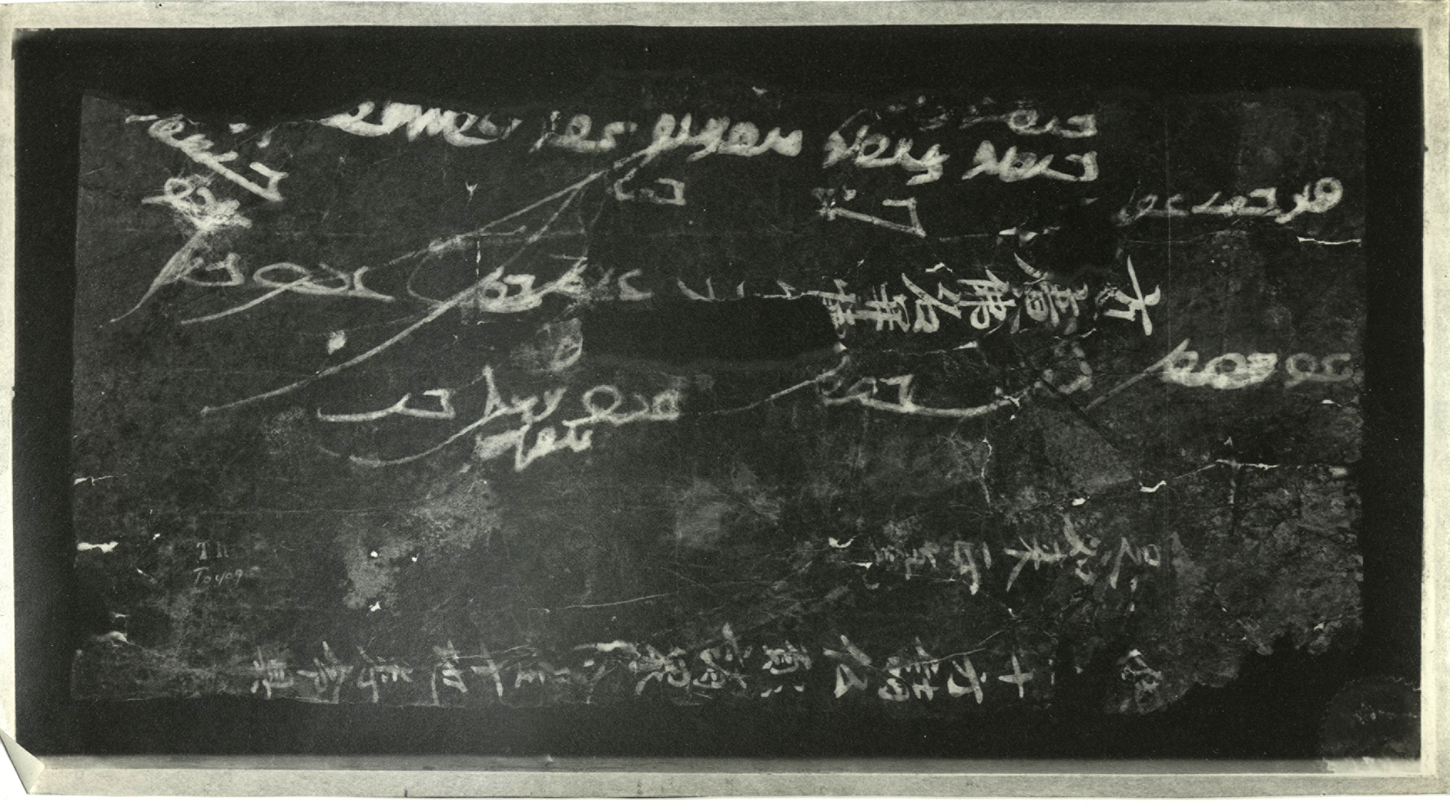

14729 (Figures 11 and 12)

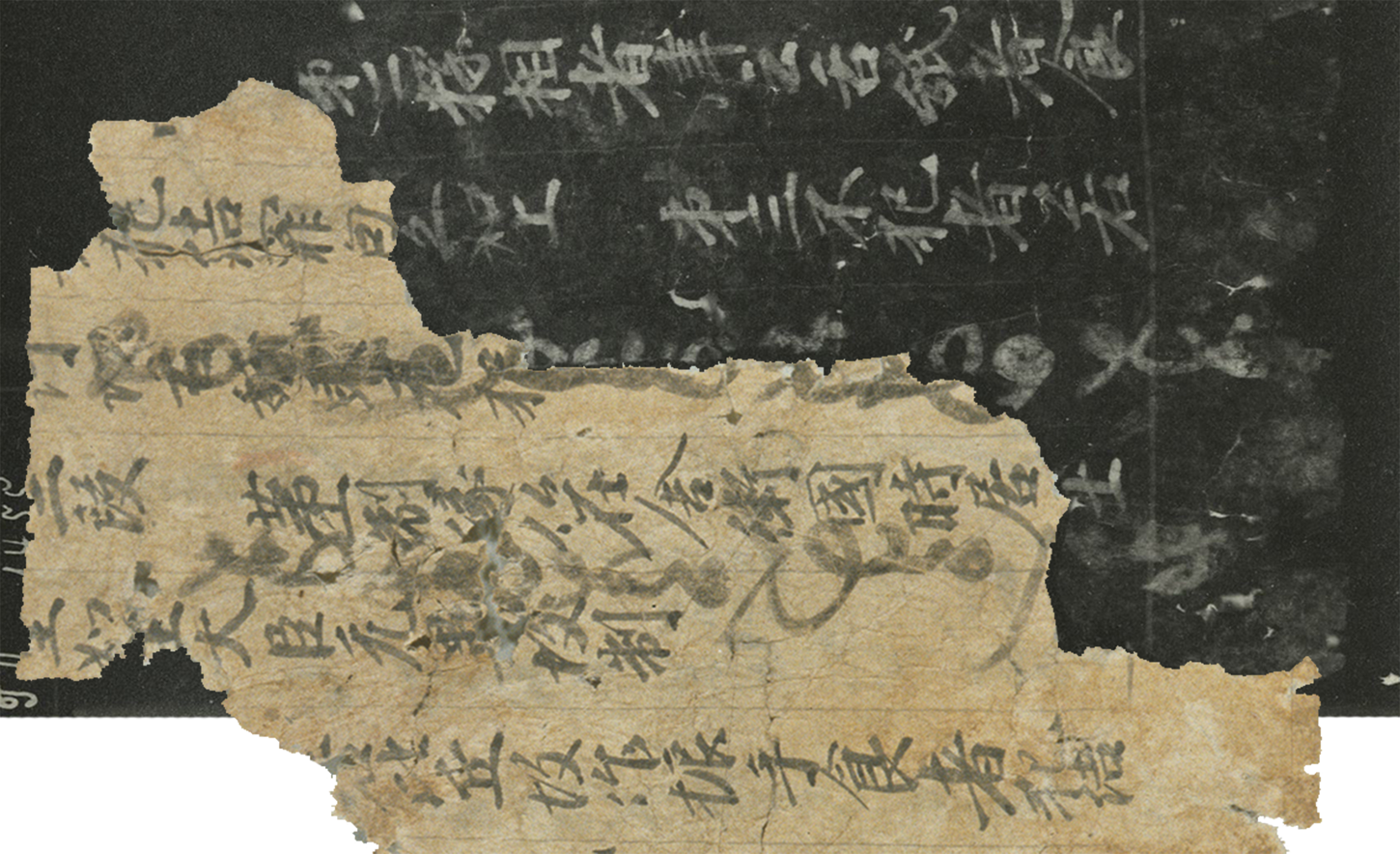

Figure 11. Ch/So 14729, verso

Figure 12. Ch/So 14729, recto

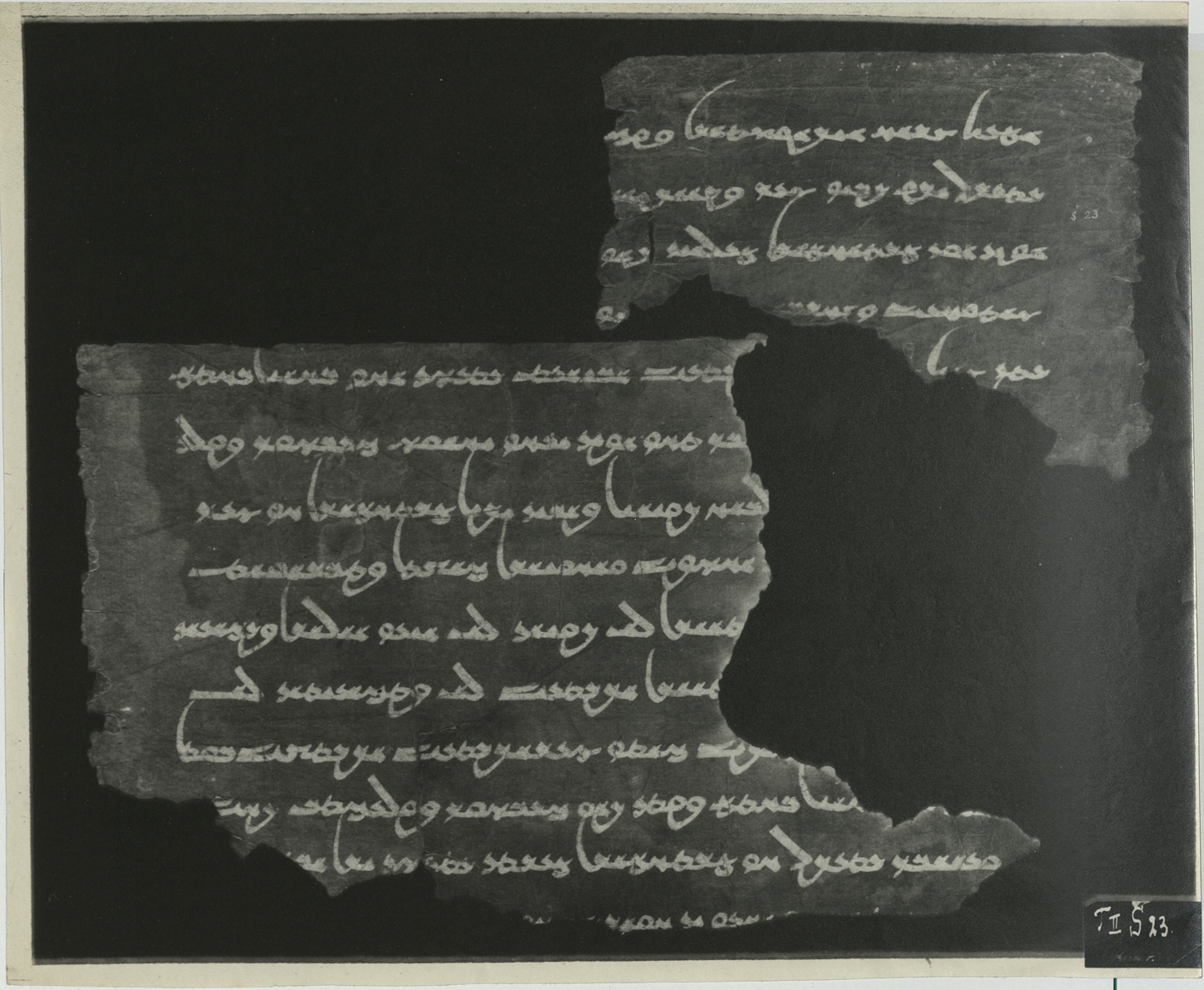

There is also no record of a fragment with this number, and no extant fragment which matches the photograph. It must be confirmed as lost. The fragment was previously known only from a transcription preserved in the Nachlass of Lentz, but lacking a number. The only description given there is “6 Zeilen auf breitem Blatt” and “Rückseite Schreibübungen”. It was assigned the new number *So 21005 by Reck (Reference Reck2006: 306), and the old transcription of Lentz was published, with corrections made on the basis of comparable epistolary formulae, in Benkato (Reference Benkato2018: 41). Those corrections can now be vindicated with reference to the photographs.

The text does not require re-editing, but the photos do add some additional information. There are two points to note. The first two lines are written in a clearly different hand to the rest of the text, which looks rather carefully written and accords well in its layout and format with other letters. In addition, part of a circle, perhaps part of a stamp or placeholder for a stamp, can be seen in the lower-left corner of the fragment, in the space left by the indented text. Together, these points suggest to me that the fragment might originally have been a real letter, which later was written on for practice by another scribe. This might be why, in line 4 of the verso, it seems that the name of the addressee was cut directly out of the paper, leaving a rectangular hole. The name of the addressee written in the first hand (lines 1–2) can be corrected from ʾynkyncʾy(?) to ʾyrkyncwr “Irkin-čōr”, an attested Turkic name.Footnote 22

In the photo of the Chinese side, the find-signature T II Toyoq can be seen written directly on the fragment. Regarding the text of this side, Lentz's original transliterations were essentially correct, but it does not seem that there is a coherent text so much as a bunch of unrelated writing exercises. A slightly improved reading and presentation to that of Lentz, which was reproduced in Benkato (Reference Benkato2018: 41), is given below:

*So 21005, recto

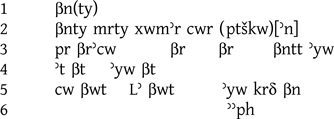

M711 (Figures 13 and 14)

Figure 13. M711, Side 1

Figure 14. M711, Side 2

Similar to M501a, discussed above, this fragment was known to Boyce only from Henning's photo, which she notes is a “copy made earlier from neg[ative]”; she describes the fragment as “bits of lines, some letters faint and blurred” (1960: 47). An additional confusion seems to have been that in Boyce's time the fragment M9012 was glassed in the plate formerly used for M711, with its label still present (1960: 138). The glass plate for M9012 is now correctly labelled, though M711 still seems to be unknown. Unfortunately, Henning's photos of M711 are of poor quality, but it is worth publishing them here for the sake of filling in the record.

Index of fragments discussed