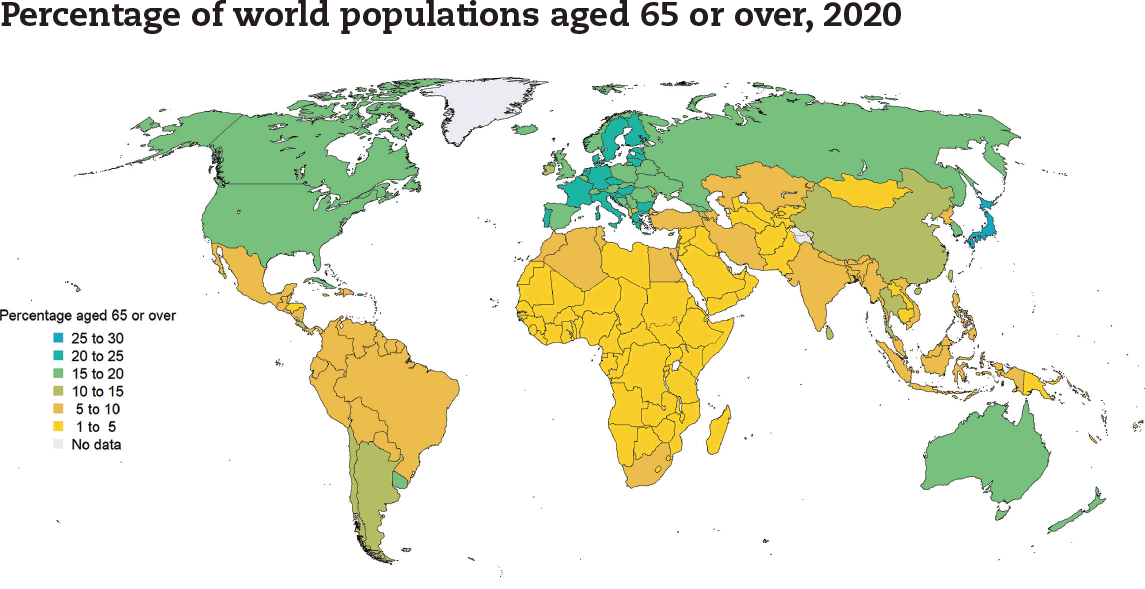

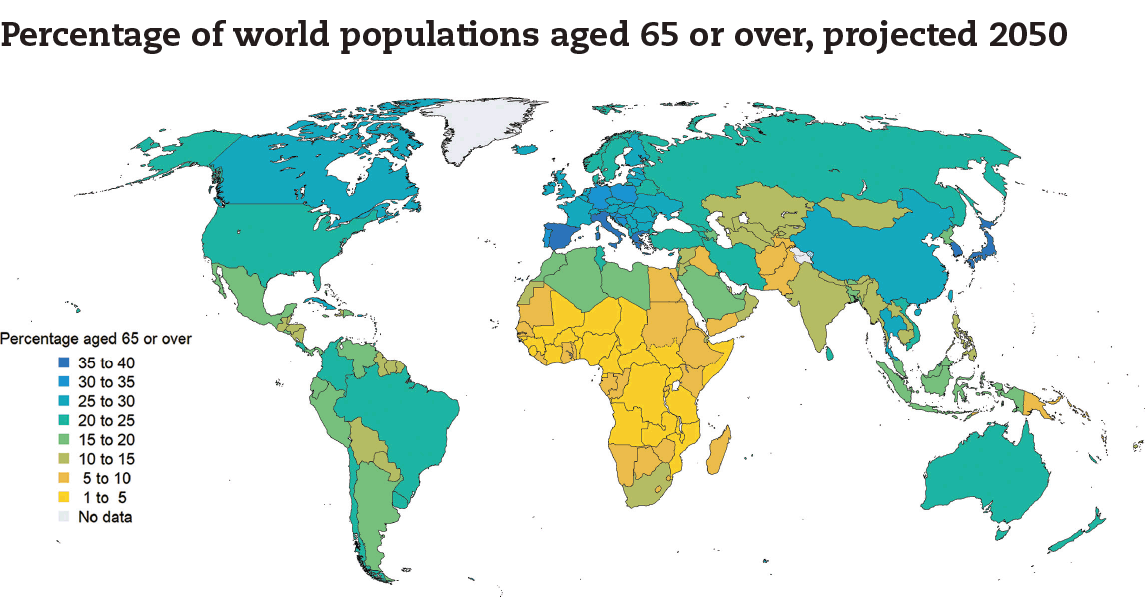

The world’s people are getting old. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), in 2018, for the first time in history, people aged over 65 outnumbered children under five. Europe has the greatest percentage of people over 60 (25 per cent) but rapid ageing is occurring almost everywhere: by 2100, the world will see just one birth for every octogenarian.1 In most parts of the globe, we are moving into a time when there will be more elderly care homes than kindergartens, more funerals than celebrations of birth.

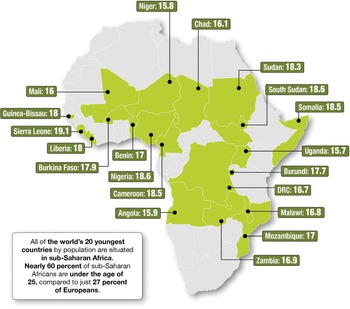

But there is one area that is bucking this trend: the world’s 20 youngest countries by population are all situated in sub-Saharan Africa.2 By 2050, Africa will be home to one billion young people,3 while the number of young people in Europe is expected to shrink by 21 per cent and in Asia by almost a third.4 As a result, by 2100 almost half of the world’s youth are expected to be from Africa, and the continent’s share of the global population is projected to grow from roughly 17 per cent in 2017 to around 40 per cent by 2100.5 The UN’s World Population Prospects says: ‘In all plausible scenarios of future trends, Africa will play a central role in shaping the size and distribution of the world’s population over the next few decades.’6

Dr Frank Swiaczny is a population specialist. A senior research fellow at the Federal Institute for Population Research in Germany and former assistant director at the United Nations Population Division in New York, he’s been studying the world’s demographics for more than two decades. Dr Swiaczny says that Africa’s high youth population could trigger a raft of economic and social benefits for the continent – an outcome known as a demographic dividend.

Figure 1 Countries with the oldest average population age

‘There is no doubt that the African continent will be completely different in future’, he says. ‘Most of the world’s population growth is happening in sub-Saharan Africa and most of it will take place in cities. Africa should be in a phase of reaping a demographic dividend – a time when the population structure contributes to economic growth. This is the same dividend that South Korea and other Asian nations were able to harness in the 20th century, but it requires development in education, rule of law, democracy and gender equality.’

Some of that dividend is already becoming evident. Dr Morten Jerven is Professor in Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. His 2015 book Africa: Why Economists Get It Wrong shows that most African economies have been growing at a rapid pace since the mid-1990s. He has written a follow-up book, The Wealth and Poverty of African States (2022), which uses tax receipts, wage data and historical GDP figures to further analyse African states. ‘I believe empirical evidence will support the argument that failed African economies are a misnomer’, he says.

Figures 2 and 3 With the exception of sub-Saharan Africa, by 2050 most regions of the globe will have a quarter or more of their populations aged over 60

A 2016 McKinsey Global Institute report, Lions on the Move II: Realizing the Potential of Africa’s Economies, supports Jerven’s view. It highlighted that growth across much of Africa accelerated to 4.4 per cent between 2010 to 2015. In 2016, Africa was already home to 700 companies with annual revenue of more than US$500 million, including 400 with annual revenue above US$1 billion. These companies, says the report, ‘are growing faster and are more profitable than their global peers’.7 The report also notes that by 2034, Africa will have a larger working-age population than either China or India, which, when added to its abundant natural resources, acts as a signifier for future growth.

Figure 4 Top 20 countries with youngest average population age

But despite the continent’s growing economic power and the scale of its emerging youth cohort, both of which are likely to make a significant contribution to worldwide development in the 21st century, Africa remains a blind spot for most in the Global North. This generation of young sub-Saharan Africans, a rapidly growing population that will vastly outnumber their Western peers by 2050, are the leaders, the scientists, the artists and the entrepreneurs that will shape our world in the next 50 years and beyond. But, in the West at least, little is known of the fears and hopes, the dreams and aspirations of this youthful population. To date, most existing research around young people has been geared towards understanding Western millennials and Gen Z. Young Africans have been largely ignored or denigrated.

When the UNFPA’s analysis of this emerging cohort was first released in 2014,8 a New York Times discussion of the report was headlined ‘The World Has a Problem: Too Many Young People’.9 The newspaper’s analysis concluded that ‘the youth bulge stands to put greater pressure on the global economy, sow political unrest, spur mass migration and have profound consequences for everything from marriage to Internet access to the growth of cities’.

This regressive view, largely based on ignorance and a mix of systemic racism combined with post-colonial conceptions of superiority, is not unusual in the Global North. ‘Sub-Saharan Africa has more variation than the EU, but we often talk about it as a whole, rather than study individual countries’, says Dr Jerven. ‘And at the moment, the main purpose of research still seems to be “what’s wrong with Africa?” With demographics for example, it’s more about European concerns rather than African potential. It’s very us versus them.’

***

The opening sequence of the Marvel movie Black Panther moves from the poverty of Oakland, one of the more deprived cities in the US, to the thriving metropolis of Birnin Zana, the fictional capital of the fictional African country Wakanda.

Ostensibly, Black Panther tells the story of Wakanda’s king and his fight for power but it also projects, perhaps for the first time in the history of Hollywood, a new vision of Africa. In the movie, Wakanda is far more developed than its Western counterparts, across everything from medicine and weaponry to gender equality. Its hospitals can cure wounds that would be fatal in the West; its weapons and armour are so superior that Western criminals attempt to steal them; and its women play a powerful role, running the armed forces and designing high-tech equipment.

In its depiction of an African country as advanced and sophisticated, Black Panther challenges traditional Western perspectives of the continent. Africa has been subject to profoundly damaging misconceptions since white foreigners first encountered it. Slavery and subjugation, the carving up of an entire continent without the consent of its peoples, the imposition of imperial borders based on nothing more than the political expediency of European powers set up a historic legacy more damaging than anywhere else on the globe. Africa’s myriad peoples and cultures have long been dismissed or disregarded in the Global North. Across literature, film, news and even academia, the continent is almost invariably portrayed as poor and bereft of both history and opportunity. In 1963, Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper infamously argued that Africa had no history prior to European exploration and colonisation: ‘The rest is darkness … the unedifying gyrations of barbarous tribes in picturesque but irrelevant corners of the globe’, he wrote.10

This vision of Africa is a white creation, initially politically useful in justifying plunder and colonialism and more recently to enable a more subtle, but no more benign, Western dominance. It was never a true vision of the continent, and, as this book will show, it is certainly dated and myopic today. Wakanda offers a welcome counter-perspective. As Jelani Cobb writes in his New Yorker piece: ‘Black Panther and the invention of “Africa”’: ‘No such nation as Wakanda exists on the map of the continent, but that is entirely beside the point. Wakanda is no more or less imaginary than the Africa conjured by [David] Hume or Trevor-Roper, or the one canonized in such Hollywood offerings as “Tarzan”.’11

In fact, Wakanda reflects a nascent reality. Despite the enslavement of the continent’s people, the destruction of its cultures and the ignorance and racism that persists to this day, African nations are thriving and growing. Inspiration for Wakanda could have come from Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda or South Africa – countries rich in educated, tech-enabled young talent entirely at home conceiving and developing solutions for a 21st-century world. And Birnin Zana, with its futuristic skyscrapers, racing trains and bustling street life, could be modelled on a host of African cities – the likes of Accra, Kigali or Lagos, the vast, energetic and flourishing commercial hub of Nigeria.

Often called the Giant of Africa, Nigeria is home to one in six sub-Saharan Africans and is currently the seventh most populated country in the world. Its population is projected to surpass that of the United States shortly before 2050, at which point it will be the world’s third largest country.12 Its borders, a product of British colonial convenience rather than any reflection of the ethnic make-up of the country, encompass three major tribes – the Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa – along with more than 200 smaller ethnic groupings. It is almost equally divided between two major religions: the Christian south and Muslim north. The country faces significant security challenges including Boko Haram terrorists in the north, Biafran calls for secession in the south-east, and banditry and competing interests for land use across large swathes of the interior. With the added challenges of an economic recession and the growing impact of the climate crisis, the country’s lawmakers face a powder keg of competing interests, which they are largely failing to contain.

Figure 5 Map of Nigeria

But the picture is far from entirely bleak. The Economist calls the country ‘the continent’s most boisterous democracy’.13 It is Africa’s largest economy, generating a quarter of the continent’s GDP14 and three of sub-Saharan Africa’s four fintech unicorns (start-ups valued at more than US$1 billion) are Nigerian. The Financial Times calls Nigeria ‘the potential economic powerhouse of the continent’ and says: ‘The country has all the ingredients for success. A huge population gives it the scale other African economies lack. It is a coastal trading hub and the world’s sixth-biggest oil exporter.’15 It is also one of the youngest countries in the world: more than 42 per cent of Nigerians are under 14,16 and half the population is under 19.17 It is the only country among the world’s five most populous that is forecast to have a rising working-age population for the rest of this century.18

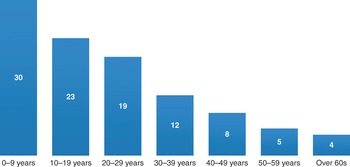

Figure 6 Percentage of Nigeria’s population by age

***

The Nigerian writer and novelist Chinua Achebe is an important figure in modern African literature. In an interview with Paris Review magazine in 1994, he said: ‘There is that great proverb – that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter. [Storytelling] is something we have to do, so that the story of the hunt will also reflect the agony, the travail, the bravery, even, of the lions.’19

This book aims to try to do just that. It documents the lives, ambitions, challenges and concerns of a group of young Nigerians living in the cities of Lagos and Abuja. It is their voices you will hear throughout the book – their hopes, their fears and their aspirations. By listening to these young Nigerians, by telling their stories, this book aims to reflect the dreams, the travails and the bravery of the young lions who will inherit the 21st century.

The young people you will meet in this book are, in the main, aged between 20 and 35. They are as different from their parents and grandparents as Western Gen Z are from Boomers. Although they share much in common with their Western counterparts, far more so than was the case a generation ago, they also inhabit a different world, with different challenges and different opportunities. And in talking with this cohort, a distinct generation emerges – creative, entrepreneurial, self-assured and hopeful, they are global in outlook but rooted in and proud of their Nigerian and African identity.

They also exhibit a confident outspokenness and a tendency for creative disruption. Enabled by the megacities in which they live and by access to technological advances – which together offer opportunities that were out of reach or simply did not exist for previous cohorts – this is a generation that is finding its voice and speaking out. This is the Soro Soke generation.

Soro Soke means ‘speak up’ in Yoruba, the language of the largest ethnic groups of Lagos and south-west Nigeria. (When correctly spelled, sọ̀rọ̀ sókè includes accents and tone marks. But, as the words have been co-opted as a protest slogan, the usage has simplified and it is this colloquial version that is used throughout the book.) The term first became a generational battle cry in the #endSARS youth protests against police brutality but has grown into the calling card of an entire cohort as it speaks up to demand opportunities and recognition. Whether it is calling out the economic challenges or failures in governance that are hampering its surge forward, celebrating its identity with vigour and pride or disrupting gender expectations and other social norms, the Soro Soke generation is making itself heard.

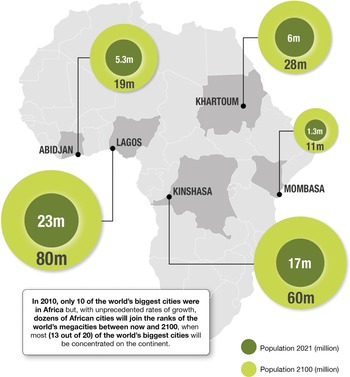

This book looks at two key factors that are shaping this cohort: urbanisation and technology. Urbanisation is changing the face of sub-Saharan Africa. By the end of this century, 13 out of 20 of the world’s biggest cities will be concentrated on the continent.20 Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is already the largest French-speaking city in the world (with Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire and the Senegalese capital of Dakar, the third and fifth respectively). Lagos is sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest conurbation and could be the world’s biggest city by 2100,21 as Greater Tokyo, currently the largest, looks set to shrink by almost a third due to an ageing population and declining birth rates.22

Cities shake things up: when people come together, creativity blossoms and innovation thrives; and Lagos is a vast metropolis with an economy significantly bigger than that of Kenya.23 In the next chapter, young Lagosians discuss how life in the city is shaping them: they are emerging as a cohort of inventive problem solvers, filled with optimism and entrepreneurial drive.

Because of their diversity, megacities like Lagos also play an important role influencing cultural trends. The city’s fashion industry is thriving, its music industry is having a global impact and the Nigerian film industry, known colloquially as Nollywood, makes more films than any other country, bar India.24 For this generation, this explosion of creativity is rooted in expressing an African, as well as specifically Nigerian, identity. In Chapter 3, the Soro Soke generation talk about their pride in Nigerian and African culture and demonstrate how they are owning their heritage and spreading that message across the globe.

Religion and tradition still have a strong cultural hold in Nigeria, but some members of this younger cohort are starting to speak up and confront social norms around gender identity and queerness. In Chapter 4, young Nigerians talk of how the increased wealth and cosmopolitan attitudes of city life, along with the burgeoning power of social media, are helping to give greater voice to marginalised groups.

Figure 7 Predicted growth of five African cities by 2100

Although urban life offers many opportunities, life in a developing megacity can also be a struggle. Emigration, the dream of a better life elsewhere, remains an aim for some, and in Chapter 5 the Soro Soke generation talk about the benefits and challenges of migration.

While increasing urbanisation plays a significant role in shaping young sub-Saharan Africans, it is access to technology that is perhaps the single greatest factor that differentiates this age group from those that came before. Technology is changing lives across the continent. As with their peers around the globe, new technologies are enabling the Soro Soke generation to mine opportunities that were unthinkable as little as a decade ago. This highly entrepreneurial cohort is using technology to leapfrog the Global North and turn intransigent pan-African problems into business opportunities that are both profitable and for the social good.25 In Chapters 6 and 7, young Nigerians discuss how technology is changing their lives and highlight the freedom and entrepreneurial opportunities it offers them.

Social media also plays an outsize role. Access to social media is enabling young Nigerians to tell their own stories and engage on equal terms with those on the same platforms in the West. It has opened this generation to wider possibilities and viewpoints and is facilitating a growing recognition of what is no longer tolerable within their society, helping to create a generation that is both increasingly frustrated and willing to call out the injustices it faces. Young people are using social media to drive activism across the continent, such as the #endSARS movement against police brutality and corruption – discussed in Chapter 8 – which mobilised a generation in street protests across Nigeria.

One of the biggest challenges facing young sub-Saharan Africans is poor governance and access to power. Africa may be home to the youngest population on earth, but its leaders are among the oldest and often cling to power for decades. Nigeria is no exception: current president Muhammadu Buhari is approaching 80 and is widely seen as out of touch with his young electorate. There is a recognition among the Soro Soke cohort that it has both the strength in numbers and the energy and ability to govern, but that it faces a real battle in accessing power. In Chapter 9, young activists in Abuja, the Nigerian capital, look to the future and discuss the issues and possible ways forward.

***

For some readers, particularly in the Global North, the stories in this book will be challenging. Encountering successful, strong, proud and outspoken young entrepreneurs, activists and leaders, there is an inclination to refute the relevance of their stories. Brought up on a diet of bleak news around sub-Saharan Africa, some will argue that the voices in this book are not representative, that these are the lucky few, the privileged minority. It is true there are people facing great hardship on the continent and that overcoming poverty is an ongoing battle for many. But in the past 40 years the African middle class has tripled to more than 330 million people and that number is predicted to exceed a billion by 2060.26 Consumer spending is rising too, by almost 4 per cent every year, to more than US$1.93 trillion in 2021.27

It is cities that are experiencing the greatest growth in wealth and almost half a billion young sub-Saharan Africans live in the region’s cities. Even by the most conservative estimate, well over a hundred million of these young people are working, studying, founding businesses, succeeding, building their lives, creating a future. That means millions upon millions who are renting apartments, eating in restaurants, being entertained in clubs and bars. They are online, on social media, using smartphones and laptops. They are living 21st-century lives. The stories in this book reflect this growing reality.

With almost a billion young people on the continent, no book can be a definitive round-up of every experience, every dream, every reality. Just as it is not possible for young people in New York to speak for the entire US, let alone for the whole of the North American continent, neither can young, urban Nigerians represent every member of their generation across a diverse country and a vast and disparate continent. But as one of the largest and most diverse groups, they offer a valuable insight into the changing landscape of young Africa. And it is only by listening to their voices, documenting the lives and dreams of the people who will lead, inspire and build our mutual future that we can begin to understand what it means to be young in an otherwise ageing world.