1. Introduction

Over the past decade, many health care systems across the Global North have implemented elements of market mechanisms while also dealing with the consequences of the financial crisis. The impact of both policy reforms and financial crises on health care has been researched extensively, each in their own terms. Studies on policy reforms, for instance, show how the introduction of pro-competitive policies have affected access to and prices of care (Lisac et al., Reference Lisac, Reimers, Henke and Schlette2010; Maarse et al., Reference Maarse, Jeurissen and Ruwaard2016; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Qin and Hsieh2016). In turn, research on financial crises shows how such crises can deteriorate health (Stuckler et al., Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee2009; Reference Stuckler, Reeves, Karanikolos and McKee2015; Karanikolos et al., Reference Karanikolos, Mladovsky, Cylus, Thomson, Basu, Stuckler, Mackenbach and McKee2013; Quaglio et al., Reference Quaglio, Karapiperis, Van Woensel, Arnold and McDaid2013), change the institutional environment in which health care is organized (e.g., the growing role of the EU in health policy) (Clemens et al., Reference Clemens, Michelsen and Brand2014a; Helderman, Reference Helderman2015) and decrease government spending on social policies (Cylus et al., Reference Cylus, Mladovsky and McKee2012; Clemens et al., Reference Clemens, Michelsen, Commers, Garel, Dowdeswell and Brand2014b; Letho et al., Reference Letho, Vrangbæk and Winblad2015; Morgan and Astolfi, Reference Morgan and Astolfi2015; Saltman, Reference Saltman2018). Our study draws from both strands of literature and specifically focusses on how reforms and crises can resonate with one another and together lead to new ways of working and interacting between health care organizations and their financial stakeholders, such as banks and health insurers.

The Dutch health care system provides an illustrative case since an important health care reform, introduced in 2006 – one that implemented market principles and made health care organizations increasingly risk-bearing organizations – was quickly followed by the global financial crisis, starting in 2007. Soon after that, regulatory agencies, in particularly the EU and banking sector, sought to mitigate the consequences of the financial crisis through new regulatory frameworks introduced in 2009 and 2011: Basel III for banks and Solvency II for insurers. Both regulations had unexpected consequences for health care organizations that were dependent for their capital provision and income on their interactions and negotiations with banks and health insurers after the 2006 policy reforms. Reforms and crisis thus together and iteratively shaped the transformation towards a more competitive way of working, forcing banks and health insurers to rethink their role and position towards health care organizations and the other way around.

In this paper, we study, through the lens of institutional theory, how banks, health insurers and health care organizations responded to the reform and financial crisis and subsequently took part in the creation of a new institutional ‘reality’. We answer the following question: How have roles, practices and interactions between banks, health insurers and health care organizations changed in response to health care reforms and the financial crisis?

Although both the Dutch reform and global financial crisis took place more than a decade ago, researching their impact is still relevant; particularly so because (in the Netherlands) the discussion about the desirability of competition in health care continues and often revolves around the ways in which banks, health insurers and health care organizations have developed new roles, relations and routines (Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Van der Scheer and Janssen2021). Moreover, Basel III and Solvency II regulations are under regular evaluation. Basel III is, for example, recently adjusted with newly added measures to be implemented by 2027 (so called Basel IV). New rules and stricter capital requirements can again change the ‘institutional reality’. Lastly, by focusing on how the health care reform and financial crisis impacted the dynamics between banks, health insurers and health care organizations, we shift attention to an understudied relationship that has become essential for the organization and provision of health care services in welfare states that adopted principles of managed competition. Better understanding roles, relations and interactions between health care organizations and their financial stakeholders can help to improve and safeguard access to health care and manage overall health care costs.

2. Institutional change and different ways to understand it

Our inquiry into changing relations in the financial arena of Dutch health care has been informed by institutional theory. Classically, institutions are considered as sets of rules and norms that prescribe what roles actors play in a particular setting and how their conduct is shaped by it (Hall and Taylor, Reference Hall and Taylor1996). Through their reproduction, institutions were deemed as static and self-reinforcing (March and Olsen, Reference March and Olsen1995). The stable and enduring nature of institutions was further considered to be fostered by the difficulty to diverge from a chosen path; for instance because of the ways in which institutions inscribe how to give meaning to the world (making it difficult to think beyond them; cf. David, Reference David1985; Arthur, Reference Arthur1989) or the ways in which institutions were implicated in confirming extant roles, power relations and social hierarchies (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983).

Because of the emphasis placed on the stabilizing character of institutions, it was difficult to understand institutional change through this approach. Most commonly, institutional change was explained as induced by exogenous shocks. These were considered external events with far-reaching and unpredictable consequences. Examples include the collapse of communist rule (Clark and Soulsby, Reference Clark and Soulsby1995), the 9/11 terrorist attack (Stratch and Sapiro, Reference Stratch and Sapiro2011; Corbo et al., Reference Corbo, Corrado and Ferriani2015), financial crises (Luong and Weinthal, Reference Luong and Weinthal2004; Moschella, Reference Moschella2015) and, more recently, the Covid-19 crisis (Deruelle and Engeli, Reference Deruelle and Engeli2021). Such events were considered to put stress on conventional meaning-making schemes and power relations, providing time-spaces to renegotiate institutional arrangements and the ways in which they inform roles and relations (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999; Wilsford, Reference Wilsford2010).

As institutional theory started to place more emphasis on practices, different readings of how to understand institutional change started to emerge (Lawrence and Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hard, Lawrence and Nord2006; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). Of particular importance was the consideration that actors do not just enact institutional arrangements, but actively and continuously try to shape their institutional context in order to improve their institutional positions, roles and relations; for instance, by contributing to the introduction, replacement, accumulation or reinterpretation of institutional arrangements (Dorado, Reference Dorado2005; Lawrence and Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hard, Lawrence and Nord2006; Wallenburg et al., Reference Wallenburg, Hopmans, Buljac-Samardzic, Den Hoed and IJzermans2016). This way, institutional changes come about over longer periods of time and through slow, subtle and incremental processes [see Mahoney and Thelen (Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010) for a comprehensive overview of such processes].

This latter reading of institutional change has gained much traction in recent institutional literature; particularly so through concepts such as institutional work and institutional layering. Concepts that emphasize the work that actors invest in shaping their own roles, relations and positions and the ways through which these roles, relations and positions are inscribed, informed and supported by their institutional environments (Lawrence and Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hard, Lawrence and Nord2006; Van de Bovenkamp et al., Reference Van de Bovenkamp, De Mul, Quartz, Weggelaar-Jansen and Bal2014; Van Oijen et al., Reference Van Oijen, Wallenburg, Bal and Grit2020; Felder et al., Reference Felder, Van de Bovenkamp, Meerding and De Bont2021). These concepts have therefore been important to show the complex and negotiated character of institutions, institutional changes and institutionally informed roles and relations.

By foregrounding institutional processes such as layering and institutional work, the role of exogenous shocks has been pushed to the background a bit in contemporary institutional analysis, although there are some exceptions. Bacharach et al. (Reference Bacharach, Bamberger and Sonnenstuhl1996), for instance, demonstrate how deregulation of the airline industry (exogenous shock) evoked institutional work from actors to create a new form of collaboration between professionals and management; Luong and Weinthal (Reference Luong and Weinthal2004) show how a financial crisis drove the Russian government and Russian oil companies to the mutual realization that incremental tax reform was necessary; Deruelle and Engeli (Reference Deruelle and Engeli2021) observe that the mandate of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has expanded gradually over the years, but only really gained momentum during the Covid-19 crisis (Reference Deruelle and Engeli2021). In line with these authors, we argue in this paper that exogenous shocks and incremental changes are not necessarily different or contradictory approaches towards understanding institutional change and its consequences. In fact, they often intertwine in the forging of new institutional contexts.

3. Institutional change in the financial arena of Dutch health care

3.1 Health care reforms

The institutional arrangements that are currently central in the financial arena of Dutch health care also result from a combination of exogenous shocks and incremental changes. Here, the classical way of organizing health care through a mix of state-based regulation and public initiatives has been complemented with the introduction of market mechanisms (Van der Scheer, Reference Van der Scheer2013). The introduction of these market mechanisms and the way in which they shape current stakeholder dynamics did not come out of the blue. Rather they are the always preliminary outcomes of an intensive and incremental process of negotiations between stakeholders (such as policymakers, banks, health insurers and health care organizations). The financial crisis, however, did come unexpected and brought a more cautious perspective on financing health care, one that placed emphasis on monitoring and financial assurance. We will use this section to introduce the main changes in the financial arena of Dutch health care over the last decade and discuss its implications for health care organizations and their financial stakeholders, starting with the introduction of managed competition and followed by the financial crisis.

The introduction of market mechanisms is often set in 2006 with the ratification of the Health Insurance Act and Healthcare Market Regulation Act. These acts were however, preceded by numerous smaller, incremental policy changes that paved the way for managed competition and eventually resulted in the current system (Groenewegen, Reference Groenewegen1994; Hassenteufel et al., Reference Hassenteufel, Smyri, Genieys and Moreno-Fuentes2010; Helderman and Stiller, Reference Helderman and Stiller2014; Van de Bovenkamp et al., Reference Van de Bovenkamp, De Mul, Quartz, Weggelaar-Jansen and Bal2014; Tuohy, Reference Tuohy2018; Vonk and Schut, Reference Vonk and Schut2019; Bertens and Vonk, Reference Bertens and Vonk2020). Already in 1987, the ‘structure and financing of health care’ committee advised the Dutch government to implement collective, mandatory health insurance and market-like incentives to address rising costs, waiting lists and inefficiency. Successive health care ministers attempted to implement the committee's plans but failed due to a lack of public and political support (Kamerstukken II, 1987–1988; Kamerstukken II, 1989–1990; Kamerstukken II, 2000–2001; Bertens and Palamar, Reference Bertens and Palamar2021). Over a longer period, however, many policies aligning with the committee's vision were added piecemeal. For example, people were allowed to switch health insurers every year, insurers were no longer obliged to contract every health care organization, and convergence between sickness funds and private insurers was stimulated. Parties in the sector gradually prepared to adopt principles of managed competition and lengthy waiting lists roused political support for systemic reform (Bertens and Palamar, Reference Bertens and Palamar2021). The following political compromises, the adding of new policies without replacing others, the gradual implementation of new rules (e.g., free price negotiations; adding curative mental health care to the Health Insurance Act) and the fine-tuning of rules after 2006 (e.g., Diagnoses Treatment Combinations), make Dutch health care an institutionally layered health care field in ongoing state of reform (Van de Bovenkamp et al., Reference Van de Bovenkamp, De Mul, Quartz, Weggelaar-Jansen and Bal2014; Maarse et al., Reference Maarse, Jeurissen and Ruwaard2016).

The move towards managed competition had a major impact on banks, health insurers and health care organizations. Since 2006, health insurers have to negotiate annually with health care organizations on price, quantity and quality of services. They also became national orchestrators of care (Kamerstukken II, 2003–2004). Moreover, in 2008, government real-estate policies were phased out; government no longer provided ex-post compensation for real-estate costs and health care organizations were made responsible for their own business and bore the full risk of running their organizations (Enthoven and Van de Ven, Reference Enthoven and Van de Ven2007; Van der Zwart et al., Reference van der Zwart, van der Voordt and de Jonge2010). For banks – the sole financers of health care real-estate and providers of short-term credit for liquidity and daily expenses – this meant that indirect government security on loans disappeared and financing risks increased (Van der Zwart et al., Reference van der Zwart, van der Voordt and de Jonge2010; NVB, 2017). Thus, banks perceived health care organizations as increasingly risk-full investments. The focus on market incentives and competition forced health care executives to become more entrepreneurial and focus on efficiency, product improvement and competition (Van der Scheer, Reference Van der Scheer2007). This new way of thinking and working also implied taking risks. Actors had to re-interpret their roles, reposition themselves towards other actors and translate market principles into their daily practices.

3.2 Financial crisis

In the middle of adapting to these new arrangements, the world was struck by a global financial crisis, that had far-reaching consequences for the health care sector. The crisis disrupted financial systems and required governments to assume state debts, leading to budget deficits and, eventually, austerity measures. In the Netherlands, government provided capital injections to support businesses and the banking sector. They also nationalized a bank, guaranteed state debts and increased deposit assurance. The following austerity measures mainly targeted public expenditure and the income of provinces and municipalities (Kickert, Reference Kickert2012; Batenburg et al., Reference Batenburg, Kroneman, Sagan, Maresso, Mladovsky, Thomson, Sagan, Karanikolos, Richardson, Cylus, Evetovits, Jowett, Figueras and Kluge2016). Measures taken relating the health care sector focused on shifting costs from public to private sources or between statutory sources. Also, care was substituted and there was an increased focus on improving efficiency and eliminating fraud (Batenburg et al., Reference Batenburg, Kroneman, Sagan, Maresso, Mladovsky, Thomson, Sagan, Karanikolos, Richardson, Cylus, Evetovits, Jowett, Figueras and Kluge2016).

The shock of the financial crisis also set in motion another series of events that impacted health care in an unexpected way. Banking and insurance regulators responded by amending existing regulations to prevent another crisis and improve the resilience of financial systems. Basel III was developed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision as mandated by the Bank for International Settlements, and Solvency II by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, an official advisory body of the European Commission. The Basel Committee operates on a global level and its members are the central banks and supervisory authorities of countries with large financial sectors, while the European Commission is a European institution.

The Basel III and Solvency II frameworks are often pictured as three-pillared entities. The three pillars represent quantitative (1), qualitative (2) and disclosure (3) requirements. The first pillar consists of capital requirements (capital ratios for banks and solvency capital requirements for insurers). The second pillar focuses on the qualitative interpretation of risk models, expressed in the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) for banks and the Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA) for health insurers. The third pillar sets requirements for financial reporting to enhance transparency and market discipline (European Parliament, 2009; Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2011). The frameworks impacted the allocation of capital and required an internal paradigm shift for banks and insurers, with a sharper focus on quantifying risks, risk-thinking and risk management. Early on, both Basel III and Solvency II were expected to have unknown consequences, for example, for the funding patterns of banks and health insurers, the interconnectedness of the frameworks and the possibility of risk transfers to consumers and other sectors (Al-Darwish et al., Reference Al-Darwish, Hafeman, Impavido, Kemp and O'Malley2011). Banks, health insurers and health care organizations needed again to re-interpret the changes that were happening in their surroundings. By adapting their roles and interactions they give meaning to this new ‘reality’, which we will further elaborate on in the result section.

4. Materials and methods

4.1 Data collection

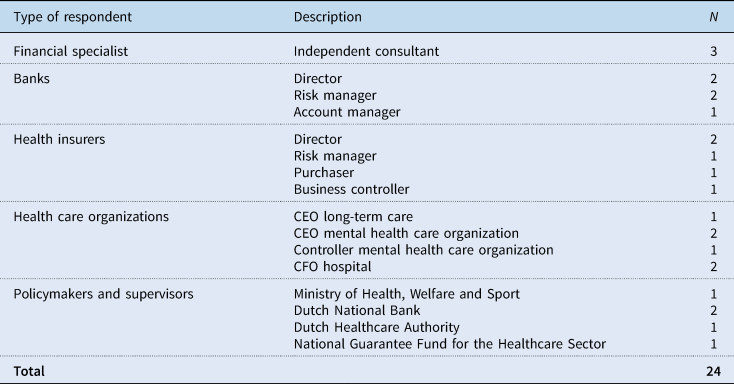

This study is based on semi-structured interviews and document analysis that cover developments within the financial arena of Dutch health care over the past 40 years (starting with a report published by the expert committee on ‘structure and financing of health care’). Seventeen interviews took place in 2017, which were complemented with seven additional interviews in 2018, 2019 and 2020. Author one was present during all interviews and authors two and four occasionally. In total, 24 respondents have been interviewed. They were chosen based on their role in the health care sector and identified through the network of the second and fourth author or the organizations they represent. Respondents included financial specialists and representatives of banks, health insurers, health care organizationsFootnote 1 and supervisory authorities. A list is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Respondents

We first interviewed financial experts working as independent advisors for health care organizations and as mediators between health care organizations and their financial stakeholders. This produced a list of key topics and helped us grasp the dynamic between health care organizations, banks and health insurers. We then interviewed representatives of these three main actors.

We ended by interviewing policymakers and supervisory authorities, chosen for their insights into policy changes in the health care sector. The Dutch National Bank also supervises health insurers and the implementation of Basel III and Solvency II. The National Guarantee Fund for the Healthcare Sector is a mutual guarantee fund for capital loans in health care and has a firm grasp of the financial topics and changing relationships that interested us.

Information derived from document analysis was used to complement, expand and confirm the insights obtained during the interviews. In addition, it helped us to better understand the process and context of the policy reforms and the financial crisis. We identified and analysed annual reports, letters to parliament and policy documents from the Ministry of Health, policy documents and working papers from government (advisory) bodies, and codes of conduct and reports from umbrella organizations (see references). The selection was based on available documents that were published by organizations that are important for the financing of Dutch health care (e.g., Ministry of Health, National Guarantee Fund for the Healthcare Sector, Dutch Banking Association). We furthermore selected documents that provided information on the financial crisis, Basel III, Solvency II and the run-up to the health care reform.

4.2 Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We used Atlas.ti and coded the interviews inductively. This resulted in 46 thematic codes, labelled closely to the words used by respondents. Codes were then compared and matched and subsequently abstracted to either the ‘role perception’ or ‘changing practices’ of actors in relation to the health care reforms or the financial crisis.

As mentioned, the documents provided background during and after the interviews and helped us understand the framework, intentions, specifications and consequences of the studied changes. They allowed us to interpret the ‘language’ used by different actors and put the interviewees' statements into context. They also made it possible to triangulate the data. Our initial interpretation was sent to respondents for a member check; they affirmed our findings and had no remarks. Finally, quotes were translated from Dutch to English.

5. Changing dynamics: how and why banks and health insurers adopt new roles, practices and interactions

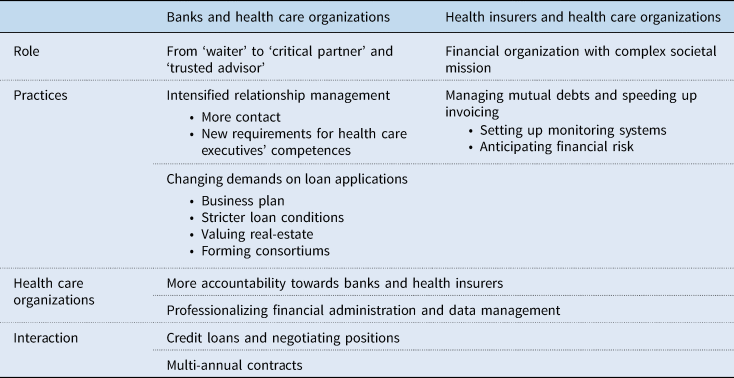

The introduction of managed competition and the Basel and Solvency frameworks led to a shift in the dependencies between banks and health care organizations and between health insurers and health care organizations. Banks and health insurers had to interpret and translate new rules and regulations into their roles, interactions and practices and reposition themselves in the field and towards one another. Below, we elaborate on these changing positions and practices. We start with banks, followed by health insurers and a short description of the consequences for health care organizations. We end with a discussion of two intersectional themes where all three actors cross paths (see Table 2 for an overview and summary of the results)

Table 2. Changing roles and practices of banks, health insurers and health care organizations

5.1 Banks

5.1.1 Role perception

The introduction of managed competition led to a change in how banks approached health care organizations. Like other private organizations, health care organizations had become risk-bearing entities. Government ex-post compensation for real-estate costs was steadily reduced and health care organizations had to rely increasingly on their sales and negotiation skills towards health insurers. This also meant a greater financial risk for banks.

Representative bank 1: Since 2006, we carry more risk. But we don't mind because that's what we do in every other sector. In fact, we're now taking on the role that we normally like to play.

Banks started to reframe their role vis-à-vis health care organizations. One of the respondents describes the old role as ‘waiter’ and the new role as ‘trusted advisor’ and ‘critical partner’ (representative bank 1 and 2). In the old role, banks passed loan applications to the ‘kitchen’ and returned with the order without asking further questions. They simply executed the order. The new role emphasizes trust and such values as ‘knowing the customer’ and ‘being a best friend’. It means advising on financial topics and making a long-term commitment to health care organizations. A critical partner, however, is not afraid to ask difficult questions and makes demands before investing, not only because of the risks involved but also because banks have a responsibility to society for ensuring financial sustainability in health care.

Banks did not adopt this new role overnight. They too had to adapt. Account managers had to learn to be trusted advisors and critical partners, for example, by training in board-level discussions of strategy. One bank manager shared what he told his account managers were the core values of this new mindset.

Representative bank 1: The most important thing about banking is to know your customer. And not just by doing their annual accounts but by visiting them regularly. Call them even if nothing's wrong, treat them like your best friend. Make a personal connection, know what's really going on with them, what keeps them awake at night. Don't just talk to the financial people, talk to stakeholders. Go meet the Supervisory Board once a year, or the medical specialists.

In keeping with their changed roles, banks use language and knowledge strategically in their business-like approach to health care organizations. The ‘partner’ and ‘best friend’ narrative is somewhat misleading, however. It suggests an equal relationship, and yet Dutch health care organizations rely heavily on banks to finance their business, as they have few other ways to access capital.

Representative bank 1: We have an enormously powerful position in the negative sense. Because if we turn off the money tap, or become averse, we can, to a certain extent, direct an organization.

5.1.2 Intensified relationship management

Banks intensified their relationship with health care organizations to get more grip on their finances, strategic choices and any risks that might affect financial results. Respondents indicate that contact between health care organizations and bank account managers has increased from annual to biannual meetings with the board and bimonthly meetings with the CFO. Banks prefer to be the principal banker, making them responsible for transactions and payments and allowing them to monitor the financial status of the health care organization and implement early-warning systems for financial distress.

Banks now also focus increasingly on health care executive performance, given executives' important role in strategic and financial planning. Their knowledge and skills, vision and relationship with external partners are crucial for banks, in addition to the relationship between the executive and supervisory boards and the organization's relationship with health insurers and its medical staff. Many respondents point out that the relationship with health insurers is of particular interest to banks, since insurers can guarantee income and revenue for health care organizations and thus indirectly guarantee interest payments.

Representative bank 2: Banks started having very different conversations with directors […] What does your health insurer think? Can they commit too? You're asking us to commit for 15, 20, 25 years, but the health insurer, the party that determines the volume of business you're going to do, has a one-year commitment. So we asked health insurers to commit for five years, or at least three. That's a big change for healthcare executives. Financing has really become a boardroom topic.

5.1.3 Changing demands on loan applications

Fuelled by the financial crisis and subsequent Basel III regulations, banks were urged to re-evaluate their previous and future investments in health care. One way for banks to mitigate and manage financial risk is by changing the loan conditions and application process, for example, by introducing business plans (1), tightening up contract conditions (2), valuing real-estate (3) and making consortium deals (4).

First, a business plan furnishes banks with the information needed to assess risk and decide on further financing. Bank representatives explain that the plan should contain information on the organization's mission, strategy and long-term vision, financial projections for the next 20 years, long-term property plans, forecasts of health care services, the organization's financial assets and the type and amount of financing required. The quote below illustrates how unfamiliar health care organizations were with this new practice.

Representative bank 1: Healthcare organizations had become risk-bearing, especially in terms of real-estate development. And that was a reason for banks to say: ‘If you want money from us, you must submit a solid business plan.’ Well, that concept alone was totally unknown at the time. I remember people asking ‘What exactly is that? Can you send me examples?’. So, the whole idea of having to underpin your plans, especially for the future […] Well, that was unfamiliar to them.

Second, contract conditions changed because health care organizations became risk-bearing entities and banks placed them in higher risk categories. Basel III further required banks to bolster capital buffers based on their outstanding loans. Banks, financial specialists and supervisory authorities say that this led to a decrease in capital spend, a rise in interest margins and financial ratios, and to increasingly picky banks. Contracts now contain clauses that make the terms conditional on changes in the Basel regulations. Financial specialists were especially indignant about this:

Financial specialist 1: The entire risk profile, the risk you take as a bank in your market, shifts directly to the other party.

Moreover, the financial crisis meant that banks had difficulty attracting long-term capital. This in turn affected the loan terms offered to health care organizations, reducing them from 30–40 to 10–25 years. Since real-estate often serves as collateral for long-term loans and has a 30-year depreciation period, health care organizations face a refinancing challenge for both the loan and the relevant interest rate. One executive shared that he had two loans to refinance. The first was easy and they were able to lower the interest rate, but the second was not. They had to make new arrangements with the original bank, which altered the terms of the loan and raised the interest rate. For banks, such arrangements offer a strategic edge because they can then reassess loan agreements and adapt them to reflect the financial risks.

Third, banks find it increasingly precarious that the collateral (real-estate) on their loans is unusable and unmarketable, since health care facilities can serve almost no other purpose. One of the banks even refers to their value as ‘the value of land minus demolition costs’ (representative bank 2). Although there are some sector differences in terms of redevelopment options, banks struggle with the right valuation method and now ask for a valuation to be included in the business plan. This gives them some security on the value of their returns in the event of bankruptcy, as required by Basel III, but also has implications for the interest rates on loans.

Fourth, banks share the risk of financing by forming consortiums. Since the health care reforms and introduction of Basel III, they are no longer willing or able to provide the entire capital for larger financial projects on their own, preferring to do so as part of a consortium. Because only five banks operate in the Dutch health care sector, consortium formation narrows health care organizations' options considerably and diminishes their negotiating power. As most respondents point out, they have no alternative and are more or less obliged to agree to the consortium's terms. One respondent is especially concerned about the impact on the position of health care organizations.

Representative WFZ: Do I still have a choice? No, I can choose between zero and no quotation. That quotation is nothing more than the sum of various wish lists held together by a staple, and I have nowhere else to go. So those conditions have become ‘take it or leave it’ contracts, because I have no choice […] I bear all the risk that banks don't want, all the uncertainties.

5.2 Health insurers

5.2.1 Role perception

The 2006 Health Insurance Act (HIA) granted health insurers a crucial role in the health care sector, making them responsible for access to care and for reducing overall health care costs (Kamerstukken II, 2003–2004). As a result, health insurers now approach health care organizations as ‘prudent buyers’. They negotiate the type and price of health care services and take a regional view of the distribution of care based on their insured population. This sometimes clashes with the interests of individual organizations.

Representative health insurer 1: Hospital X requested a new medical device. Our accountant did a quick calculation: ‘No way, we're not going to cover it.’ They were pissed off. We said: ‘If we zoom out, we see that hospital Y specialises in this very device and is located within a radius of 1.5 kilometres. And it has overcapacity, so get together with them.’ But it's about prestige, their own interests; medical specialists' interests differ from the interest of total care provision in that region. We often have to be the bad guy.

The task assigned to health insurers under the HIA often results in conflict, as the quote shows. Health insurers say they have long struggled with their new role and how to play it. They are private organizations and represent their insured, but they often receive negative publicity for their role during negotiations with health care organizations and for their focus on finances.

Representative health insurer 1: On the one hand, we're a financial service provider. That's how we're treated, that's how we're held accountable. On the other hand, we try to take the lead in our region when it comes to the quality and development of care.

After the adoption of Solvency II, health insurers – like banks – increasingly focused on risk management. Although respondents indicate that Solvency II mainly had consequences for health insurers' internal organization, health care organizations were also affected.

5.2.2 Managing mutual debts and speeding up invoicing

The financial transactions that take place between health insurers and health care organizations consist of invoices and prepayments. Specifically, health care organizations charge for health care services and health insurers pay these charges. Owing to the lengthy contracting and slow invoicing processes,Footnote 2 however, health insurers furnish advance payment, allowing health care organizations to continue delivering care. This system results in a jumble of mutual debts that take years to settle.

The delay in debt settlement results in financial risks that have become especially critical under the Solvency II regime. If a health care organization is in debt to a health insurer, the latter must reserve capital (solvency capital requirements) to cover the risk of default. To ensure better oversight of who is in debt to whom and for how much, health insurers increasingly deploy systems to monitor mutual debts. This requires an enormous effort from both health insurers and health care organizations and has shifted the focus in interactions between them to directly available financial information.

Having a better grasp of mutual debts allows health insurers to anticipate financial risks, periodically adjust the prepayment amounts and intervene when health care organizations deliver care in excess of their contracts.

Representative health insurer 2: Standard policy is that if all goes well, we monitor. And the second the contract ceiling is reached, we stop paying. Of course, we may have a conversation about the delivery of extra care and extended contracting. That sometimes leads to extra contracting, and sometimes not […] So we've developed a whole contracting administration system that registers all the agreements with healthcare providers in detail.

Health insurers thus started to expedite payment and urged health care organizations to speed up invoicing.

5.3 Consequences for health care organizations

Health care organizations were obliged to respond to the measures taken by banks and health insurers. Health care executives indicate that banks and health insurers put pressure on them to furnish information on both the financial and governance aspects of their organization. Executives feel growing pressure to account for themselves with their financial stakeholders, even though they do not always understand the reasons for certain requirements.

Health care organizations were also urged to professionalize their financial departments and accountability practices. New job titles were created, such as internal account managers, auditors and sales managers, to draft financial prognoses for business plans and financial reports and to negotiate with health insurers. With health insurers urging them to speed up invoicing, health care organizations also invested in IT and support services. Many organizations professionalized their financial administration and boosted their liquidity positions. As with banks and health insurers, these changes increasingly steered health care organizations towards financial risk management.

To deal with this new ‘reality’, some executives say that they act strategically to establish trust relationships with their financial stakeholders. Trust is conditional, however: health care organizations can earn it if they perform well financially, adhere to financial ratios and share the same vision. This has its perks: organizations that show longer periods of financial stability and have ‘earned’ the trust of banks and health insurers have better access to capital or multi-annual contracts. Other executives are more resistant. They try, for example, to evade the influence of banks by actively seeking alternative investors to spread their own financial risk or find allies and media outlets with which to share their discomfort with the insurers' negotiating practices.

5.4 Interactions

There are two situations in which the interests of banks, health insurers and health care organizations clash or converge owing to the strategies they deploy to cope with financial risk. The first is when the actions of banks affect the negotiating position of health care organizations vis-à-vis health insurers. The second is when all three parties align their interests in a multi-annual contract.

5.4.1 Credit loans and negotiating positions

After Basel III, banks re-assessed not only their outstanding long-term loans but also their short-term credit facilities. They set limits on and increased provision rates for unused credit to reduce their risk. These moves met with resistance from health care organizations, however.

Representative bank 1: There is huge resistance from healthcare organizations. They say: ‘We want to keep that credit facility. Our backs are against the wall if we can't come to an agreement with health insurers. And then we'll have to sign a contract that we disagree with because otherwise we can't pay salaries next month.’

This example illustrates how the interests of banks, health insurers and health care organizations interact and conflict. Health insurers only want to pay for services that are delivered (and preferably invoiced); they do not want to bear the financial risk for undelivered services. Banks do not want the credit facility to be used to cover the expenses of the health care organization that could have been paid from income provided by health insurers. Finally, as the quote shows, health care organizations use the credit facility as a buffer during negotiations with health insurers. By setting stricter limits on credit facilities, banks might indirectly weaken the negotiating position of health care organizations vis-à-vis health insurers.

5.4.2 Multi-annual contracts

Multi-annual contracts are a topic of interest for banks, health insurers and health care organizations alike. All three benefit from such contracts in terms of risk containment or role fulfilment. Banks aim to mitigate financial risk and often furnish capital under the condition that health care organizations sign a multi-annual contract with health insurers. Both banks and health care organizations then have a guaranteed income for the term of the contract and are assured that long-term and short-term liabilities are covered. For health insurers, multi-annual contracts provide an opportunity to fulfil their national orchestrating role. Such contracts often see health insurers stipulating that health care organizations must re-organize and reduce their services, the idea being that this will lower overall health care costs. Such contracts appear to offer certainty, with parties sharing and allocating financial risks.

Although banks push for multi-annual contracts, health insurers say that only the health care organizations and health insurers are contracting parties and contracts are only concluded when the conditions are met and mutual trust is established. Now that ‘downsizing’ is an increasingly important factor in these contracts, banks have become more critical of them. They argue that scaling back activities may damage the business operations of health care organizations and thus hurt banks too, since health care organizations will earn less, jeopardizing their financial obligations towards banks and posing a new financial risk.

Representative bank 3: Let me put it this way. Agreements about downsizing have an impact on the business case and existing financing. We provided financing based on a certain estimated output. If that decreases, then we must decide together whether we should restructure the loan, because less income means fewer repayments on loans and lower interest obligations. So we sit down together, which isn't always fun.

Criticisms notwithstanding, in many cases multi-annual contracts have allowed the interests of banks, health insurers and health care organizations to converge by giving them a common purpose with individual benefits.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Informed by institutional theory we show how institutional arenas come about through both the long-term efforts of institutional agents and unpredictable implications of economic and societal crises. As others (e.g., Bacharach et al., Reference Bacharach, Bamberger and Sonnenstuhl1996; Luong and Weinthal, Reference Luong and Weinthal2004; Deruelle and Engeli, Reference Deruelle and Engeli2021) have also shown, exogenous shocks and incremental changes can be intertwined as agents make sense of, reflect on and translate the implications of crises and stepwise transformations into emergent practices. Moreover, the institutional change perspective helped interpret how reforms and crises shaped roles, practices and interactions between health care organizations and their financial stakeholders in the Netherlands.

In the new arrangements that emerged, banks and health insurers took on new roles and responsibilities as critical partners or purchasers of care. This had implications for their relations vis-à-vis health care organizations. Banks became increasingly proactive and changed loan procedures unilaterally by requiring business plans, imposing stricter loan requirements, forming consortiums and valuing real-estate. They also demanded more financial information and sought more contact with health care organizations. Health insurers, in turn, struggled with their new dual role: on the one hand, they had become a financial organization; on the other, they had a role in society in ensuring access to and affordability of care. They tightened up their monitoring and accountability practices, started tracking mutual debts meticulously and expedited the invoicing cycle. The new practices imposed on health care organizations required internal adjustments. Since banks and health insurers increasingly based their decisions on financial information, health care organizations had to invest in new data and invoicing systems and expand their support services. They were forced to learn more about finances to deliver the required information, draft a business plan and speak the language of banks and health insurers.

The increased focus on mitigating and shifting financial risks by banks, health insurers and consequently health care organizations started with the introduction of managed competition and was further amplified by the financial crisis and the following regulatory frameworks. Managing financial risks became an important topic in the boardrooms of all three actors. For health care organizations, this was however a new phenomenon, one which they had to adapt to. Besides, dependence on banks and health insurers for the survival of health care organizations also increased. Health care executives were challenged to, in line with managed competition, act as entrepreneurs (Van der Scheer, Reference Van der Scheer2007), which became challenging because of restrictions on access to capital by banks and health insurers.

While Basel III and Solvency II were developed specifically for banking and insurance, they also impact other sectors. Both are currently subject to revision or already revised. How new rules are shaped on a global or European level has consequences for local health care organizations. Beck (Reference Beck1992) has argued that organizing processes in an attempt to control risk produces new risks. These ideas resonate with economists who warn of risk-shifting mechanisms arising from regulation: regulation does not eliminate financial risks in a system but shifts them onto ‘shadow banks’ and then further down the system (Van Poll, Reference Van Poll2017). We observed the same behaviour in our study, with banks in particular trying to shift financial risks onto health care organizations in their contracts.

The focus on risk management and efforts by banks, health insurers and health care organizations to minimize their own risk also resonates with literature on risk work (Horlick-Jones, Reference Horlick-Jones2005; Gale et al., Reference Gale, Thomas, Thwaites, Greenfield and Brown2016). This perspective provides an interesting alternative lens for future research into the sociological dynamics between financial institutions and health care. We observed, for instance, different forms of risk work that include the interpretation of risks, negotiation of risk ownership, risk monitoring, risk containment, risk shifting and risk-sharing behaviour. We have also seen that banks and health insurers mainly focus on maintaining and protecting one's own (financial) position. These actions complement already existing forms of risk work (Gale et al., Reference Gale, Thomas, Thwaites, Greenfield and Brown2016; Labelle and Rouleau, Reference Labelle, Rouleau and Power2016) and might provide new insights.

Our results invite discussion on the involvement of private parties in a sector with important public goals and the organization of health care systems in general. The relationship between banks, health insurers and health care organizations is not static but dynamic; it is constantly being renegotiated, reworked and translated into the financial practices of the health care sector. This requires constant reflection on the role and practices of private parties in health care and what effect these have on the societal mission of health care organizations. It is essential that the relationship between banks, health insurers and health care organizations is in balance. As mentioned, some health care organizations are seeking alternative ways to raise capital to lessen their dependence on banks. Such actions may indicate that the power balance is skewed. Stadhouders et al. (Reference Stadhouders, Wackers, Smit and Jeurissen2023) conclude the same when they show that a better financial position of health care organizations not necessarily leads to a more advantageous interest margin. As our study shows, the organization of health care systems remains a complex matter in which the top-down implementation of reforms and frameworks influence the roles and behaviours of actors, while simultaneously, the day-to-day practices of the various stakeholders also affect the state of the system and influence its sustainability.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the respondents for their time and insightful information. We also express our gratitude to the editor and reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Financial support

None.

Conflict of interest

None.