Introduction

The superfamily Dromioidea De Haan, Reference De Haan1833 comprises notable representatives in modern ecosystems from rocky shores to deep sea (McLay, Reference McLay1993, Reference McLay1999, Reference McLay2001; McLay and Ng, Reference McLay and Ng2005). The fossil record of dromioids extends back to the Jurassic (see Jagt et al., Reference Jagt, Van Bakel, Guinot, Fraaije, Artal, von Vaupel Klein, Charmantier-Daures and Schram2015 and Luque et al., Reference Luque2019 and references therein), and the group attained maximum diversity during the lower Eocene (Ypresian; see Table 1) in reef environments of northern Italy (Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2002, Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonello2005, Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2007, Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonello2012, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Tessier and Zorzin2016a, Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonellob, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Fornaciari, Papazzoni and Tessier2018) and Spain (herein). Detailed systematic reviews of dromioids during recent years have resulted in new classificatory schemes (Karasawa et al., Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Karasawa2012; Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Tavares and Castro2013; Jagt et al., Reference Jagt, Van Bakel, Guinot, Fraaije, Artal, von Vaupel Klein, Charmantier-Daures and Schram2015; Guinot, Reference Guinot2019; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Mychko, Spiridonov, Jagt and Fraaije2020) based mainly on new discoveries and considering their importance in decapod crustacean phylogeny.

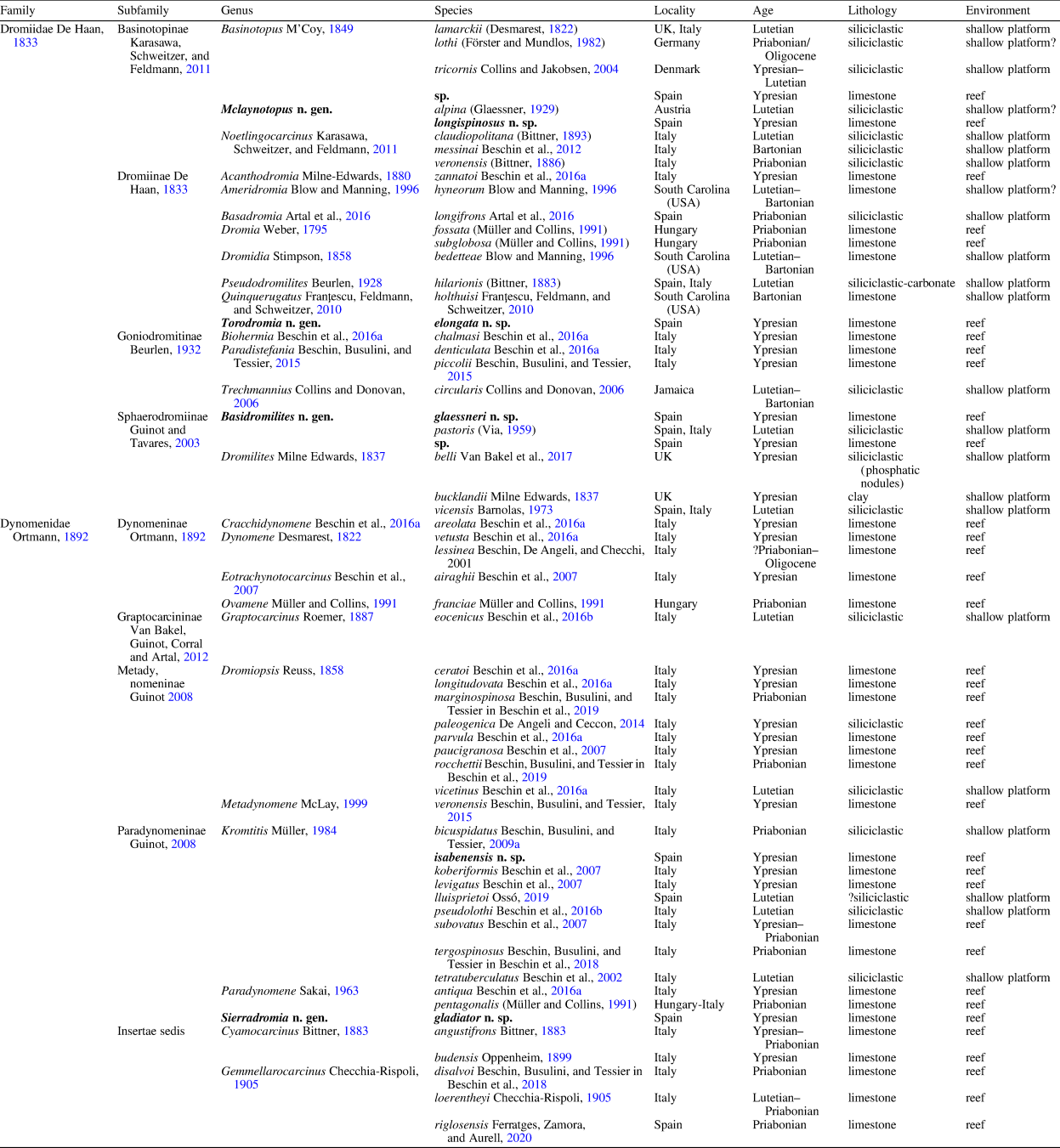

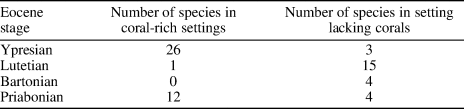

Table 1. Eocene representatives of genera placed in the superfamily Dromioidea De Haan Reference De Haan1833. New representatives of genera within the superfamily Dromioidea from the “Barranco de Ramals” outcrop and described herein indicated in bold.

The Eocene record of dromioid crabs is comparatively rich, but material is often fragmentary. To date, 53 extinct species of dromioids are known from the Eocene, with the highest diversities associated with reef environments in the Atlantic–Tethyan Realm (Desmarest, Reference Desmarest1822; Bittner, Reference Bittner1893; Checchia-Rispoli, Reference Checchia-Rispoli1905; Via, Reference Via1959; Quayle and Collins, Reference Quayle and Collins1981; Solé and Via, Reference Solé and Via1989; Müller and Collins, Reference Müller and Collins1991; Blow and Manning, Reference Blow and Manning1996; Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2002, Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2007, Reference Beschin, De Angeli and Zorzin2009b, Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonello2012, Reference Beschin, Busulini and Tessier2015, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Tessier and Zorzin2016a, Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonello2016b, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Calvagno, Tessier and Zorzin2017, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Fornaciari, Papazzoni and Tessier2018, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Tessier and Zorzin2019; Collins and Jakobsen, Reference Collins and Jakobsen2004; Jakobsen and Feldmann, Reference Jakobsen and Feldmann2004; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Artal, Fraaije and Jagt2009; Franţescu et al., Reference Franţescu, Feldmann, Schweitzer, Fransen, De Grave and Ng2010; De Angeli and Ceccon, Reference De Angeli and Ceccon2014; Artal et al., Reference Artal, Van Bakel, Domínguez and Gómez2016; Ossó, Reference Ossó2019; Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora, Aurell, Jagt, Fraaije, van Bakel, Donovan, Mellish and Schweigert2020) (see Table 1).

Here we describe new dromioid taxa from a decapod crustacean assemblage associated with reef facies of an early Eocene age in the Pyrenees (Huesca, Spain). This specific locality corresponds to a reef environment that has already yielded a wide range of decapod crustaceans (Artal and Via, Reference Artal and Via1989; Artal and Castillo, Reference Artal and Castillo2005a; Artal and Van Bakel, Reference Artal and Van Bakel2018a, Reference Artal and Van Bakelb; Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2019). Among the material recognized at this outcrop, dromioids represent only a small portion (3.1%) of the total assemblage (see Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2021), yet surprisingly, they are unusually highly diverse compared with other Eocene assemblages. This new discovery has prompted a revision of all Eocene dromioid faunules to compare these in terms of diversity and environment with the present material.

Geological setting

The southern Pyrenean basins were located at tropical latitudes during the Paleogene (e.g., Hay et al., Reference Hay, Barrera and Johnson1999; Silva-Casal et al., Reference Silva-Casal, Aurell, Payros, Pueyo and Serra-Kiel2019) and, in the Eocene, formed part of an elongated gulf that connected in the west to the Bay of Biscay and was limited in the north to the axial zone of the Pyrenees (see Plaziat, Reference Plaziat1981; Garcés et al., Reference Garcés, López-Blanco, Valero, Beamud, Muñoz, Oliva-Urcia, Vinyoles, Arbués, Caballero and Cabrera2020). These basins rank among the most complete records of Eocene marine sedimentary successions in Europe, with decapod crustacean taxa described from several outcrops (e.g., Via, Reference Via1969, Reference Via1973; Artal and Castillo, Reference Artal and Castillo2005b; Artal et al., Reference Artal, Van Bakel and Castillo2006, Reference Artal, Van Bakel, Fraaije and Jagt2013; Ossó et al., Reference Ossó, Dominguez and Artal2014; Dominguez and Ossó, Reference Dominguez, Ossó and Charbonnier2016; López-Horgue and Bodego, Reference López-Horgue and Bodego2017; Artal and Van Bakel, Reference Artal and Van Bakel2018a, Reference Artal and Van Bakelb, Reference Artal, Van Bakel, Jagt, Fraaije, van Bakel, Donovan, Mellish and Schweigert2020; Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2019, Reference Ferratges, Zamora, Aurell, Jagt, Fraaije, van Bakel, Donovan, Mellish and Schweigert2020). These successions document a wide range of depositional settings, from proximal alluvial to shallow marine in the east to slope and deep-marine and abyssal plains in the west (e.g., Garcés et al., Reference Garcés, López-Blanco, Valero, Beamud, Muñoz, Oliva-Urcia, Vinyoles, Arbués, Caballero and Cabrera2020).

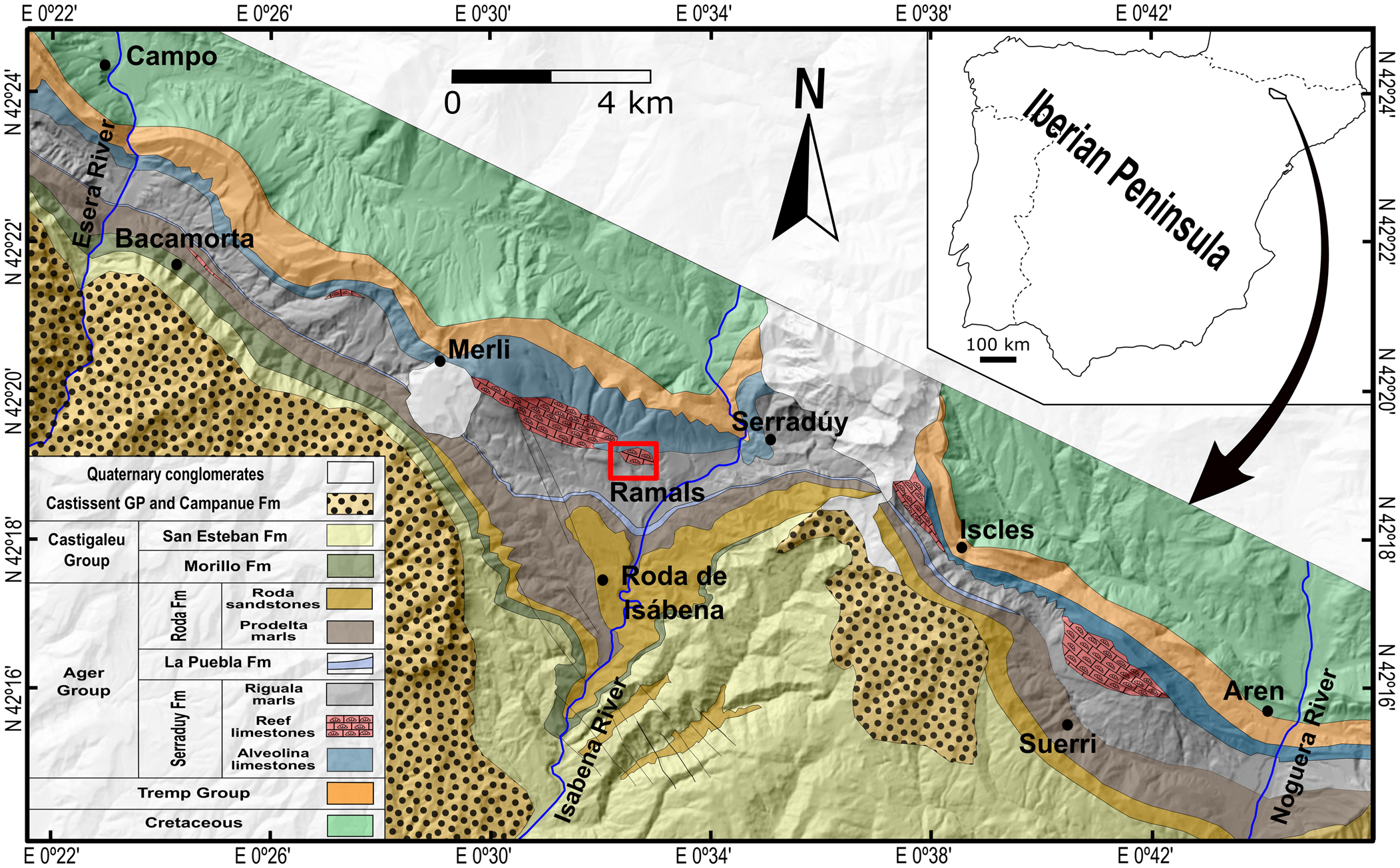

The material described herein was collected from the lower Eocene (middle Ypresian) Serraduy Formation of the Tremp-Graus Basin, and more specifically from the classic outcrop of “Barranco de Ramals” near the villages of La Puebla de Roda and Serraduy in the northeast of the province of Huesca (Aragón, Spain; Fig. 1). This locality has yielded an important assemblage of decapod crustaceans in association with pinnacle coral reefs (Via, Reference Via1973; Artal and Via, Reference Artal and Via1989; Artal and Castillo, Reference Artal and Castillo2005a; Fraaije and Pennings, Reference Fraaije and Pennings2006; Artal and Van Bakel, Reference Artal and Van Bakel2018a, Reference Artal and Van Bakelb; Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2019, Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2021) as well as diverse invertebrate faunas (see Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Aurell, Veitch, Saulsbury, López-Horgue, Ferratges, Arz and Baumiller2018; Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2021). However, dromioid crabs remained undescribed until now.

Figure 1. Geological map of the western sector of the Tremp-Graus Basin (modified after Serra-Kiel et al., Reference Serra-Kiel, Canudo, Dinares, Molina, Ortiz, Pascual, Samso and Tosquella1994). The boxed area between Merli and Serraduy marks the location of the study area.

Low depositional rates and optimum climatic conditions favored the development of a set of pinnacle reefs on top of the Alveolina limestones, which suggests a setting of intermediate depth and wave action (Gaemers, Reference Gaemers1978). The Riguala Marls Member, which overlies the reefal unit, has been dated as early to middle Ilerdian (Serra-Kiel et al., Reference Serra-Kiel, Canudo, Dinares, Molina, Ortiz, Pascual, Samso and Tosquella1994), which corresponds to the global Ypresian Stage (Pujalte et al., Reference Pujalte, Schmitz, Baceta, Orue-Echebarría, Bernaola, Dinarès-Turell, Payros, Apellaniz and Caballero2009). This unit formed as a forereef facies in which most of the material was derived from the reef as a result of storm activity, inclusive of the crab specimens described herein (see Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2021 for more details). Thus, the dromioids, as well as other decapod crustaceans recovered from the same outcrop, lived near these reef pinnacles (Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2021).

Materials and methods

Specimens were collected from the outcrop that exposes the transition between the reef limestones and the overlying Riguala Marls at a locality known as “Barranco de Ramals.” A total of 162 specimens of dromioids have been studied from this outcrop. Some of this material (18 carapaces and 17 isolated propodi; 3.1% of total assemblage) was recovered during a detailed paleoecological study of the area in years 2018–2019 (see Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2021 for more details). The remaining specimens (95 carapaces and 33 isolated propodus) were taken from historical museum collections. All material was prepared using a Micro Jack 2 air scribe (Paleotools; Brigham, Utah, USA), and fine, marly matrix was removed chemically using potassium hydroxide (KOH). Next, specimens were photographed dry and coated with ammonium chloride sublimate. Detailed photographs of carapace surfaces were taken using a Nikon D7100 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a macro 60 mm lens.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

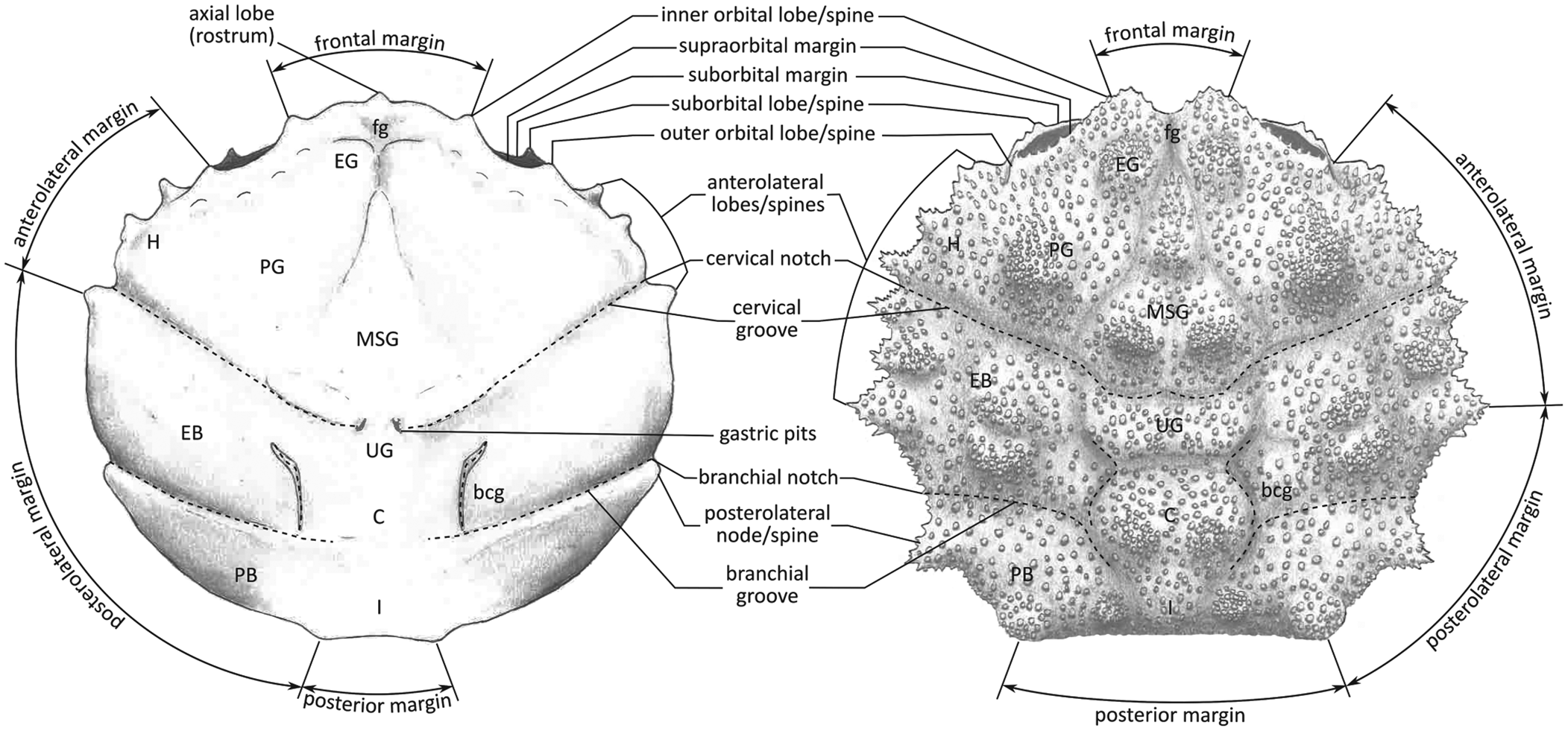

Part of the material was collected during the early 1980s (see Artal and Via, Reference Artal and Via1989); this is housed in the collections of the Geological Museum of the Barcelona Seminary (MGSB). More recent collections in the area were made to quantify the abundance and distribution of taxa (see Ferratges et al., Reference Ferratges, Zamora and Aurell2021); this material was recovered under permit EXP: 032/2018 from the “Servicio de Prevención, Protección e Investigación del Patrimonio Cultural (Gobierno de Aragón)” and is currently deposited in the paleontological collections of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad de Zaragoza (MPZ). The terminology used in the text is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Carapace regions and terminology in a dromiid (s. lat.) crab used in the text (based on McLay, Reference McLay1999). EG = epigastric region; PG = protogastric region; MSG = mesogastric region; H = hepatic region; UG = urogastric region; C = cardiac region; EB = epibranchoial region; PB = postbranchial region (meso- and metabranchial regions); I = intestinal region; fg = frontal groove; bcg = branchiocardiac groove.

Systematic paleontology

Classification and terminology used herein follow Guinot (Reference Guinot2008, Reference Guinot2019), Guinot et al. (Reference Guinot, Tavares and Castro2013), and Jagt et al. (Reference Jagt, Van Bakel, Guinot, Fraaije, Artal, von Vaupel Klein, Charmantier-Daures and Schram2015), but see alternative hypothesis of classification in Karasawa et al. (Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011) and Luque et al. (Reference Luque2019).

Superfamily Dromioidea De Haan, Reference De Haan1833

Family Dromiidae De Haan, Reference De Haan1833

Subfamily Basinotopinae Karasawa, Schweitzer, and Feldmann, Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011

Diagnosis

“Carapace slightly longer than wide, broadly triangular; rostrum broadly triangular, axially sulcate, with well developed median rostral spine; orbits deep, oblique, directed anterolaterally, suborbital margin with large spine; short segment between outer-orbital angle and first anterolateral spine, placing them at same level; lateral margin with three spines anterior to intersection of cervical groove and one very long, posterolaterally directed spine posterior to intersection of cervical groove; cervical, postcervical, and branchiocardiac grooves deep, cervical and branchiocardiac grooves intersecting carapace margin and extending onto flank; carapace with large nodes on regions” (Karasawa et al., Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011, p. 539).

Genus Mclaynotopus new genus

Type species

Mclaynotopus longispinosus n. sp. by present designation.

Other species

Mclaynotopus alpina (Glaessner, Reference Glaessner1929).

Diagnosis

Carapace subpentagonal, about as long as wide. Frontal margin trilobed, all spines of nearly equal size. Maximum width in anterior portion, at level of epibranchial region. Orbits directed anterolaterally, with blunt spine on suborbital margin. Anterolateral margins with three long spines, excluding outer orbital spine; last hepatic and large epibranchial nearly fused at base. Posterolateral margins with small spine, followed by small tubercle. Dorsal regions well defined by swellings and grooves. Dorsal surface with small granules in anterior portion, pitted posteriorly.

Etymology

Named in honor of Colin McLay (University of Canterbury, New Zealand), who has contributed greatly to our general knowledge of dynomeniform crabs, plus the suffix “notopus.”

Remarks

The morphologically most closely similar genus, Basinotopus (see the following), is characterized by a broadly triangular carapace outline (see Karasawa et al., Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011, p. 539); the maximum width is in the posterior portion, at the level of the metabranchial region. The front is prominent, with a long axial spine; the orbits are larger, with oblique supraorbital margin; the epibranchial spine is invariably weak, short, and thin; a more-projected lateral spine is situated posterior to the branchial notch, being posterolaterally directed. The lateral spines in Basinotopus are always weak, thin, and moderately long (see Busulini et al., Reference Busulini, Tessier, Visentin, Beschin, De Angeli and Rossi1983; Collins and Jakobsen, Reference Collins and Jakobsen2004; Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonello2005; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Artal, Fraaije and Jagt2009).

The new genus shows a number of clearly distinct characters, such as a subpentagonal carapace, with the maximum width in the epibranchial region; the frontal margin is nearly straight, with a weakly projected axial spine, two longer and thin inner orbital spines; the outer portion of the supraorbital margin is nearly horizontal; the epibranchial spine is extremely large and long, with a very broad base; the second anterolateral spine is fairly strong, nearly fused to the epibranchial spine, both are in close approximation. On the basis of these features, we consider the erection of a new genus warranted. We transfer Dromilites alpina Glaessner, Reference Glaessner1929 to the new genus because of similar outline of carapace and similar distribution of dorsal regions.

Type material

The holotype is MGSB77597, a well-preserved carapace, with cuticle preserved; there are five paratypes: MGSB77598a–e.

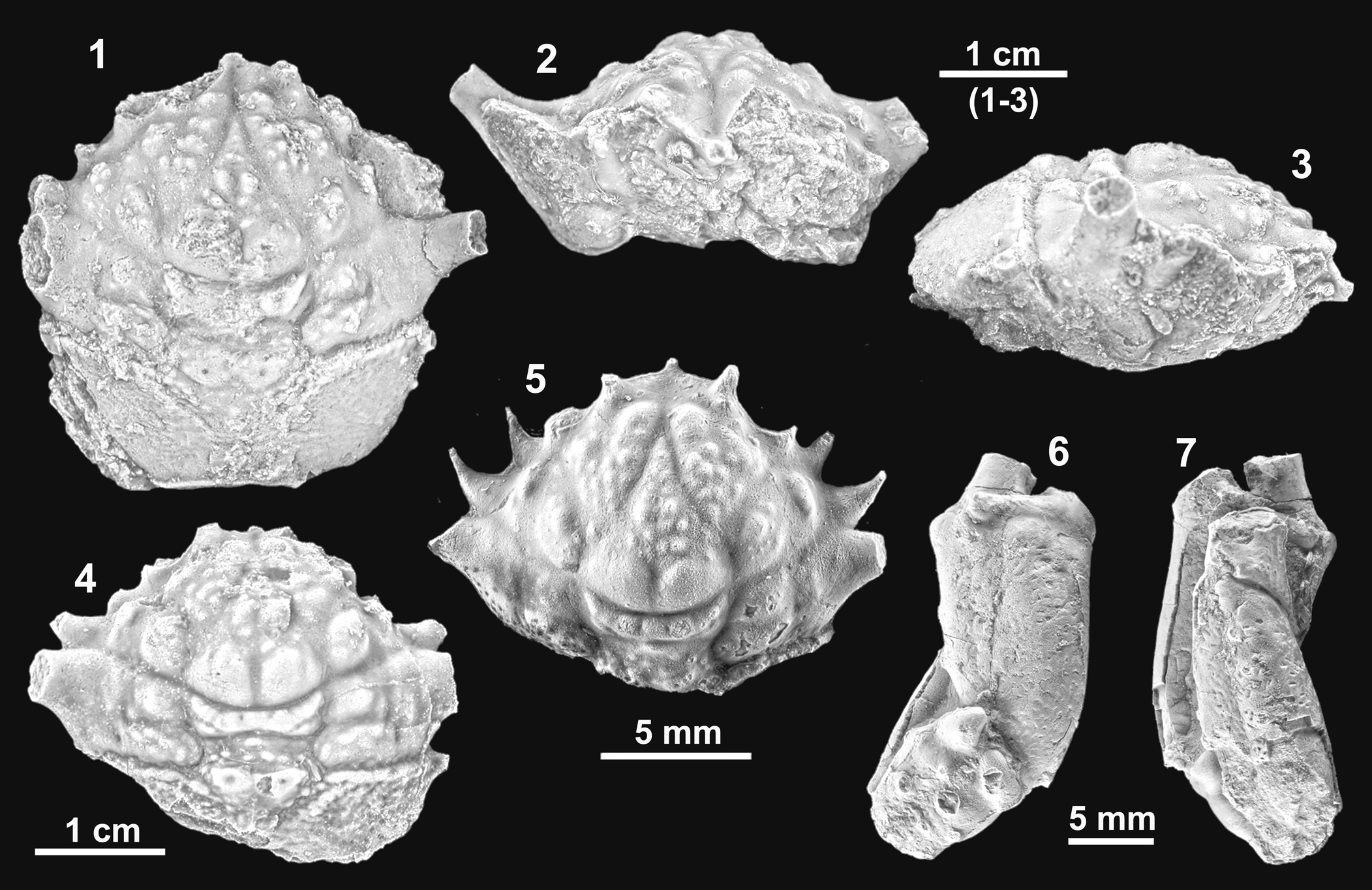

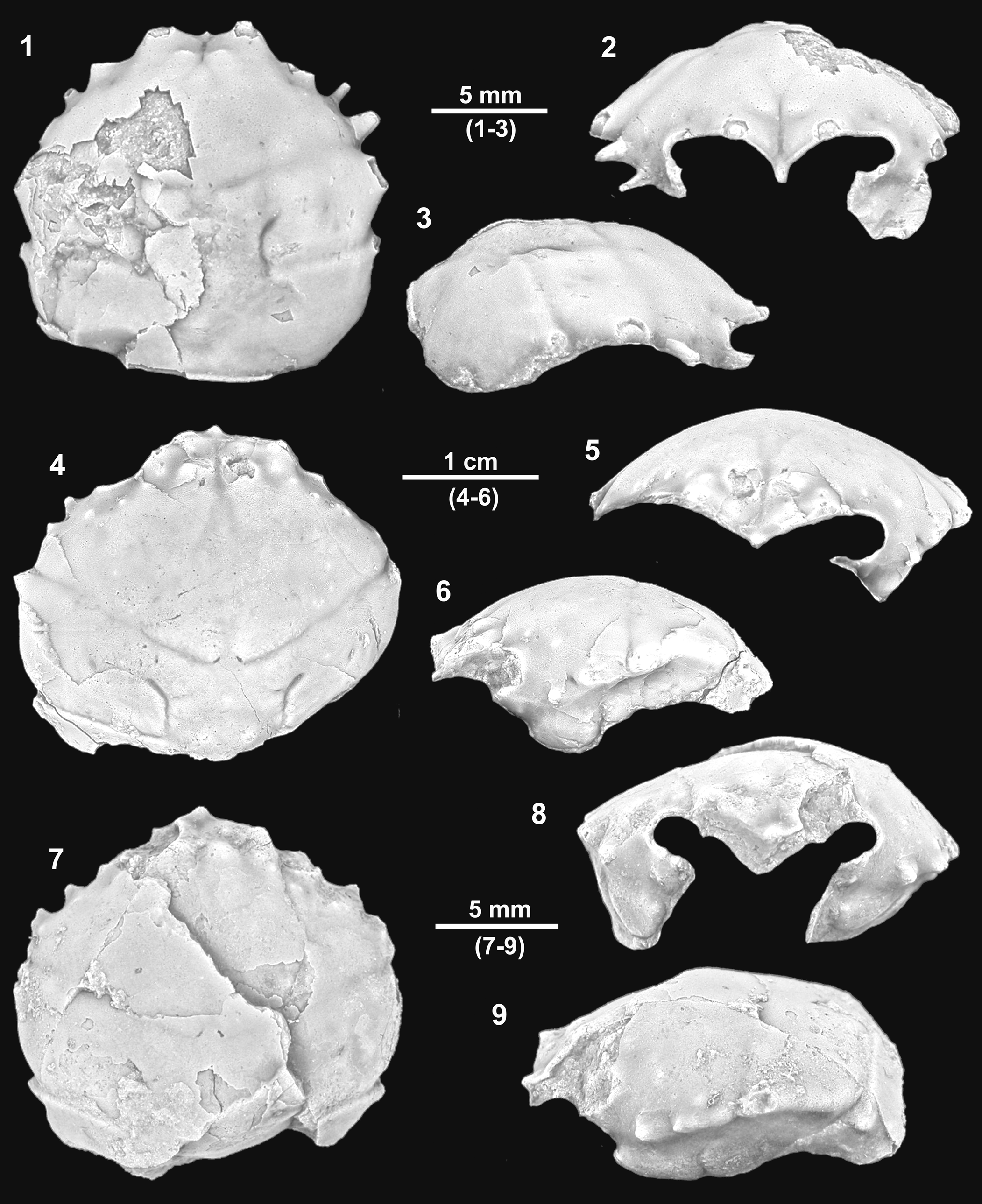

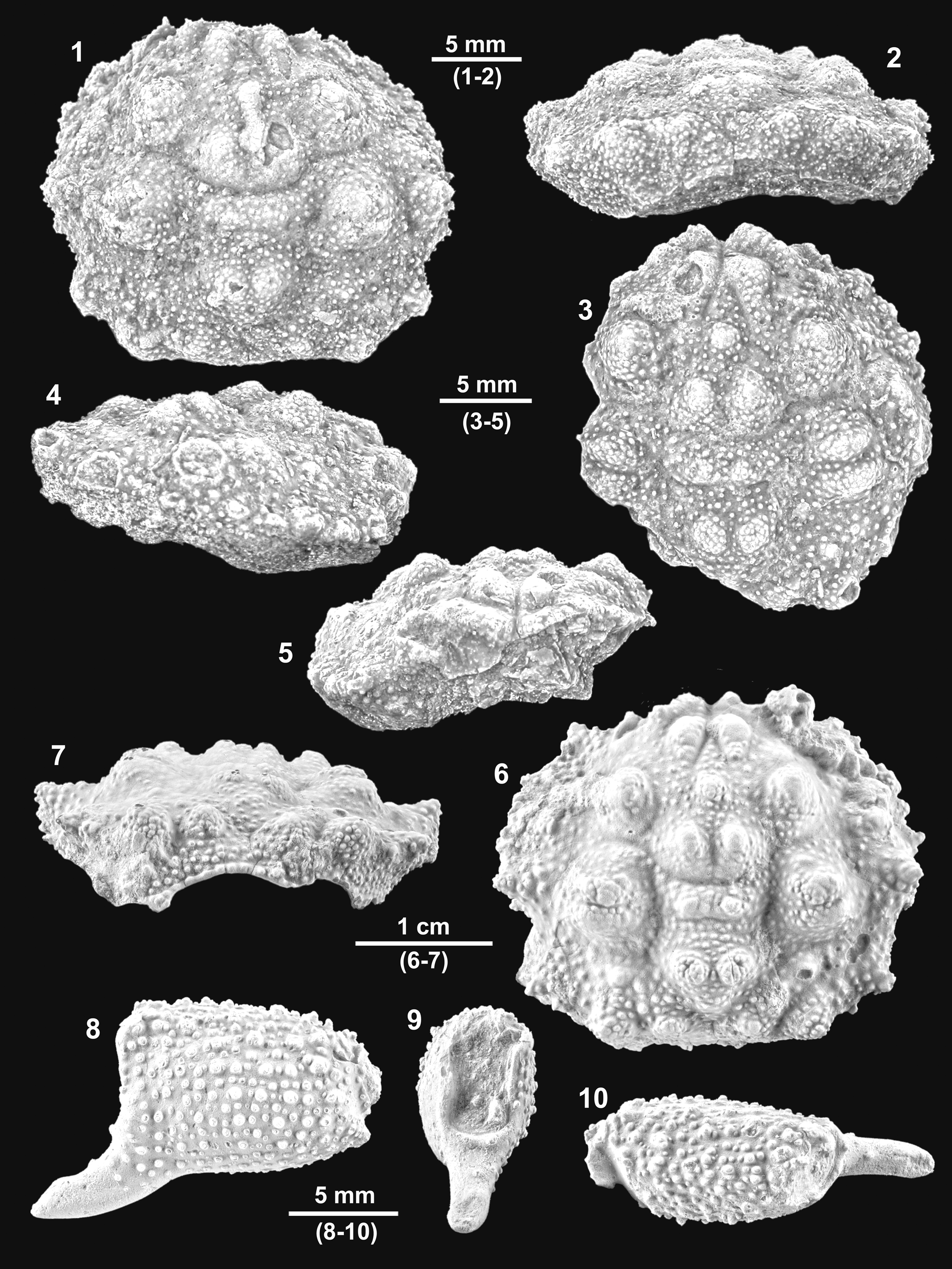

Figure 3. Mclaynotopus longispinosus n. gen. n. sp. from the Serraduy Formation (Huesca, North Spain). (1–3) Holotype MGSB77597 in dorsal, frontal, and right lateral views, respectively. (4) Paratype MGSB77598 in dorsal view. (5) Paratype MPZ-2021/153 in dorsal view. (6, 7) Isolated cheliped (MPZ-2021/148), presumably of Mclaynotopus longispinosus, in outer and inner views, respectively. Specimens whitened with ammonium chloride sublimate before photography.

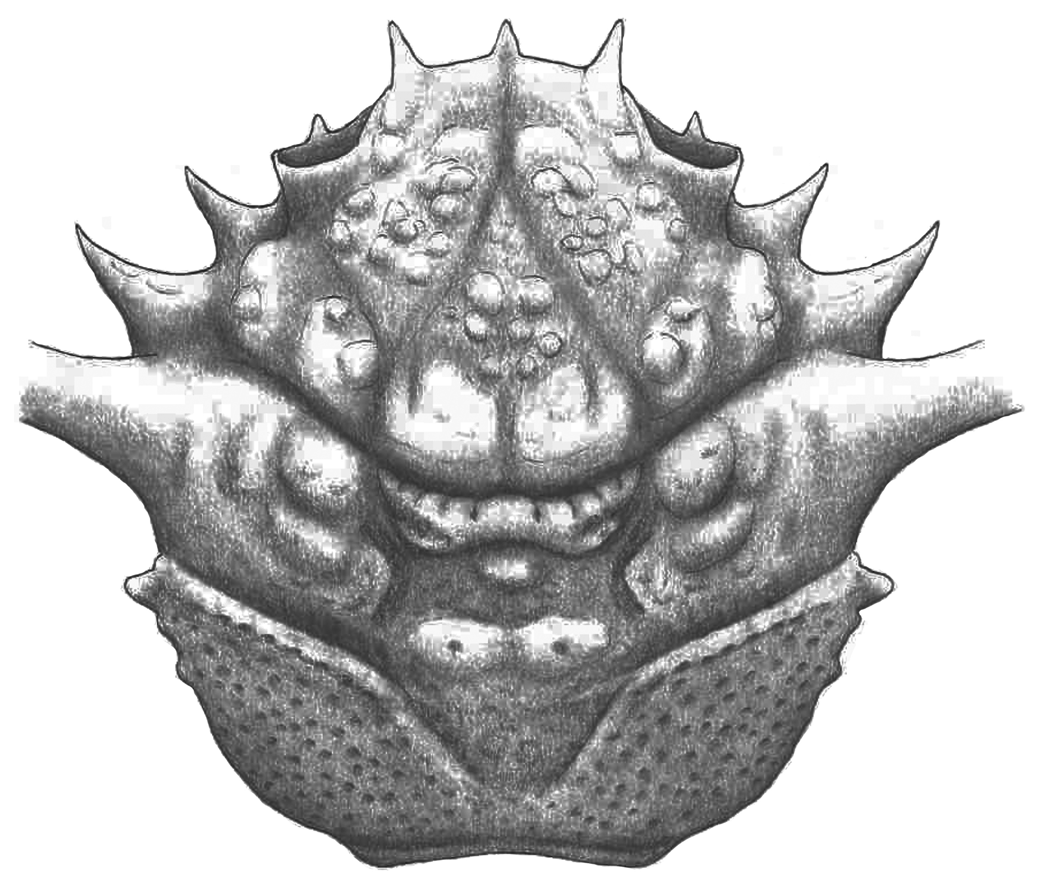

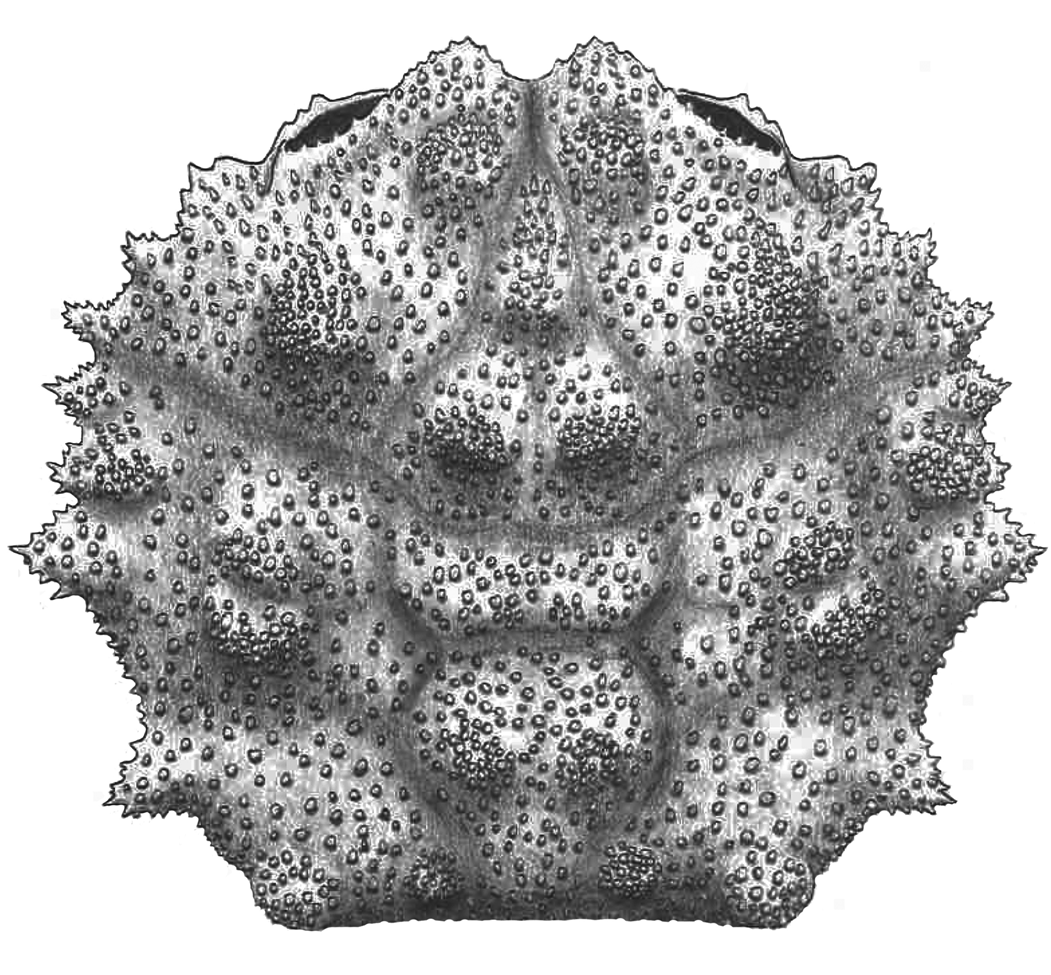

Figure 4. Reconstruction of Mclaynotopus longispinosus n. gen., n. sp.

Diagnosis

Subpentagonal carapace. Trilobed front, lateral spines of similar size, axial spine somewhat smaller. Anterolateral margins with three long spines; second hepatic and the epibranchial nearly fused, close together. Epibranchial spine large, stout; base occupying entire epibranchial area. Tips of dorsal regions and dorsal granules blunt, clearly rounded.

Description

Carapace subpentagonal, nearly as long as wide (length/width ratio about 0.95), broadly convex in both directions. Maximum width at level of epibranchial region, just posterior to extremely pronounced epibranchial spine. Dorsal surface strongly convex. Front broad, deflexed axially, broadly triangular or V-shaped in frontal view, with shallow axial depression, trilobed in dorsal view, with two robust inner orbital spines; the two inner orbital spines strong, stout, upwardly directed, not very projected, ventral side flattened, dorsal side rounded; axial spine situated in lower plane, short and robust subtriangular base, spinous tip, directed forward, visible in dorsal view. Orbits large, anterolaterally directed, slightly raised in lateral portion; outer orbital corner with deep incision, bounded by projected outer orbital and suborbital spines; subelliptical in frontal view, suborbital margin with strongly projected spine, with broadly triangular base and irregular lobe in distal portion.

Entire lateral margin with four spines, one small posterior tubercle, and two weak notches. Anterolateral margin nearly straight, only slightly convex, bearing two acute hepatic spines and one larger epibranchial spine, with broad triangular base; portion behind orbit, short, nearly vertical. Second hepatic spine larger than first spine, close to extremely projected epibranchial spine and almost fused to it. Epibranchial projection large, projected, laterally and upwardly directed, with broadly triangular base occupying entire distal portion of epibranchial region. Anterolateral and posterolateral margins nearly equal in length, posterolateral nearly straight in first portion, broadly convex posteriorly, with thin, long postbranchial, conical spine, and small posterior tubercle. Lateral margins with two slight indentations, corresponding to intersection of cervical and branchial grooves. Posterior margin nearly straight, slightly concave axially, rimmed, slightly less wide than orbitofrontal margin.

Dorsal regions defined by swollen lobes, divided into portions by grooves. Cervical groove well defined, reaching ventral portion of carapace. Branchial groove straight, nearly horizontal, bounded posteriorly by strong rim, axially interrupted by broad cardiac swelling. Branchiocardiac grooves sinuous, deep, short. Mesogastric region subtriangular, with arched base, bounded by deep cervical groove; posterior portion divided into two gently swollen lobes, separated by shallow axial groove; anterior extension swollen, bearing notable scattered tubercles. Protogastric region large; posterior portion defined by subelliptical swelling; anterior portion elongated, bearing tubercles. Hepatic region small, slightly inflated, with scarce tubercles. Suborbital region with small inflation. Urogastric region broad, arched, bounded by deep grooves, surface covered by large irregular pits and vertical depressions. Epibranchial region large, bearing two transverse swellings. Meso- and metabranchial regions undifferentiated, large, gently swollen, densely covered by small pits. Cardiac region large, subpentagonal, strongly swollen, bounded by numerous tubercles, bearing three notable tubercles; two anterior ones with large central pit and posterior one, situated apically, with some granules. Intestinal region small, depressed. Ventral portion of carapace with deep extensions of cervical and branchial grooves and with suborbital and subhepatic swellings. Chelipeds elongated; merus subtriangular in cross section, smooth; carpus slightly longer than tall; surface with some widely spaced smooth tubercles. Manus longer than tall, slightly divergent distally, elliptical in cross section; upper margin with three small, aligned tubercles; lower margin slightly concave at the base of the fixed finger, surface smooth (Fig. 3.6, 3.7).

Etymology

The specific name refers to the elongated spines on the lateral carapace margins.

Other material examined

Fifty-four incomplete carapaces (MGSB77630a–j; MGSB77632a–q; MGSB77634a–q; MPZ-2021/46; MPZ-2021/153–2021/161) and 15 isolated chelipeds (MGSB77620; MPZ-2021/148–2021/152).

Remarks

Dromilites alpina, which was subsequently listed as Basinotopus alpina (see Collins and Jakobsen, Reference Collins and Jakobsen2004; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Artal, Fraaije and Jagt2009), is a species that can be reassigned to Mclaynotopus n. gen. with confidence. Its carapace features match the generic diagnosis (see the preceding), e.g., the subpentagonal outline, the similarly distributed dorsal regions, and an extremely elongate epibranchial spine. However, the epibranchial projection in that species is much thinner, with the base not totally occupying the epibranchial margin. Moreover, the contiguous hepatic spine, which is nearly fused to it in the new species, is clearly separated in M. alpina. Mclaynotopus alpina also shows distinct dorsal regions: the protogastric and the anterior extension of the mesogastric are much more ridged. Regions in general have more acute conical tips, such as the mesogastric and epibranchial, and the urogastric has longer lateral portions (see Glaessner, Reference Glaessner1929, pl. 8).

Subfamily Dromiinae De Haan, Reference De Haan1833

Diagnosis

“Carapace longer than wide to wider than long; rostrum typically bilobed; orbits without augenrest, deep, circular; orbital margin often with protuberance or rim, subouterorbital spine often visible in dorsal view; cervical groove weak; postcervical groove sometimes present; branchiocardiac groove present” (Karasawa et al., Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011, p. 541).

Genus Torodromia new genus

Type species

Torodromia elongata n. sp. by present designation.

Diagnosis

Carapace longitudinally elongate, slightly wider than long; frontal margin bilobed, with two thin, long inner orbital spines and barely visible axial spine; orbits large, concave, directed forward. Anterolateral margins with three conspicuously long spines; two posterior ones rather robust and with broad base. Posterolateral margin with single thin spine. Dorsal regions nearly smooth, with only gentle swellings and weak grooves. Small oblique depressions in gastric area.

Etymology

The generic name combines toro, Spanish for bull, in reference to the horned rostrum, and dromia.

Remarks

The main characters of Torodromia n. gen. allow placement in the Dromiinae. These include a carapace of equal length and width, a typically bilobed rostrum, a suborbital spine that is visible in dorsal view, weak cervical and branchial grooves, and marked branchiocardiac groove (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Karasawa2012; Feldmann and Schweitzer, Reference Feldmann and Schweitzer2019). Diagnostic features of the new genus include large and long spines on lateral carapace margins, barely defined dorsal regions, and a deep, short groove in the frontal margin. Fossil representatives of the Dromiinae can be easily distinguished from Torodromia, as indicated in the following.

Basadromia Artal et al., Reference Artal, Van Bakel, Domínguez and Gómez2016, has a frontal margin with four spines, while lateral margins lack prominent spines, having merely small denticles. Dorsal regions in Basadromia are swollen; there are numerous grooves and a dense granulation. Artal et al. (Reference Artal, Van Bakel, Domínguez and Gómez2016) and Feldmann and Schweitzer (Reference Feldmann and Schweitzer2019) placed this genus in the Dromiinae.

Pseudodromilites Beurlen, Reference Beurlen1928 also possesses two strongly projected triangular spines on the frontal margin, and dorsal regions have pronounced grooves and are distinctly swollen. Lateral margins in Pseudodromilites have small lobes or small subtriangular spines while the dorsal surface is strongly granulated (De Angeli and Alberti, Reference De Angeli and Alberti2018, p. 158).

Quinquerugatus Franţescu, Feldmann, and Schweitzer, Reference Franţescu, Feldmann, Schweitzer, Fransen, De Grave and Ng2010 exhibits a nearly straight frontal margin when seen in dorsal view. It has larger supraorbital margins than in Torodromia and lateral margins bear small, short, and conical spines while the cervical groove is well defined, deep in the axial portion, bearing two small pits; the branchial groove is deep and well marked (Franţescu et al., Reference Franţescu, Feldmann, Schweitzer, Fransen, De Grave and Ng2010, p. 260).

The new genus can be differentiated from the extant Cryptodromia (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Karasawa2012) by possessing larger and longer spines on the lateral margins, a slightly developed axial spine in the frontal margin, a deep axial frontal groove, and deep branchiocardiac grooves.

Torodromia elongata new species

Figures 5.1–5.3, 6.

Figure 5. Dromioids from the Serraduy Formation (Huesca, North Spain). (1–3) Torodromia elongata n. gen. n. sp. holotype MGSB77595 in dorsal, frontal, and right lateral views, respectively. (4–9) Basidromilites glaessneri n. gen. n. sp.: (4–6) holotype MGSB77599 in dorsal, frontal, and left lateral views, respectively; (7–9) paratype MGSB77600 in dorsal, frontal, and left lateral views, respectively.

Figure 6. Reconstruction of Torodromia elongata n. gen. n. sp.

Type material

The holotype is MGSB77595, a near-complete, well-preserved carapace, retaining cuticle. There is one paratype, MGSB77596, which lacks a portion of the posterior margin of the carapace.

Diagnosis

As for genus (monotypy).

Description

Carapace suboval, slightly wider than long (length/width ratio 0.93). Maximum width posterior to epibranchial spine. Dorsal surface convex in both directions. Front deflexed, relatively narrow, bilobed in dorsal view, strongly V-shaped in frontal view, margin slightly rimmed, with a short but deep axial groove; the two inner orbital spines strong, robust, directed forward, with broadly triangular base, the axial spine situated in lower plane, thin, short, inclined forward, poorly visible in dorsal view. Orbits large, arched in appearance in dorsal view, anterolaterally directed, slightly raised in lateral portion; large, subelliptical in frontal view, bearing small, thin suborbital spine. The whole lateral margins broadly arched, with four projected spines and two faint notches. Anterolateral margin arched, bearing two thin, long hepatic projections (first one thinner, acute, second one larger) and strong epibranchial spine with broadly triangular base. Posterolateral margin equaling width of anterolateral, arched, bearing notable notch and posterior thin, projected, branchial spine. Lateral margins with two marked indentations corresponding to cervical and branchial grooves. Posterior margin nearly straight, slightly rimmed, slightly wider than frontal margin. Dorsal regions relatively well defined by gently swollen lobes and shallow grooves. Cervical groove weakly marked, more evident in central portion, interrupted by two small gastric pits. Branchial groove well defined, posteriorly bounded by a thin ridge. Branchiocardiac grooves deep, short, and axially concave. Epigastric regions small, well marked, swollen, separated by short but deep groove. Mesogastric and protogastric regions scarcely differentiated. Hepatic region large and gently swollen. Urogastric region subtrapezoidal and slightly inflated. Epibranchial and postbranchial regions large, gently swollen, separated by thin ridge. Cardiac region broad, swollen, subpentagonal. Intestinal region small, depressed. Anterior dorsal surface covered with diminutive pits.

Etymology

From the Latin elongatus, in reference to its elongated carapace shape.

Other material examined

Two additional specimens, MGSB77631a, b.

Remarks

Torodromia elongata n. gen. n. sp. is morphologically close to the extant Cryptodromia tuberculata Stimpson Reference Stimpson1858, which has an elongated carapace outline, the frontal margin characterized by a thin axial spine and two projected lateral spines, and the lateral margins arched, bearing thin and relatively elongated spines (McLay and Ng, Reference McLay and Ng2005, p. 8). However, the new fossil species differs in having larger and longer spines on the lateral margins while the axial spine on the frontal margin is slightly developed, the axial frontal groove is deep, and branchiocardiac grooves are also deep.

Quinquerugatus holthuisi Franţescu, Feldmann, and Schweitzer, Reference Franţescu, Feldmann, Schweitzer, Fransen, De Grave and Ng2010, differs in several features (see the preceding); the familial level placement of this taxon should be revised. It would appear better accommodated in the subfamily Sphaerodromiinae (see the following).

Subfamily Sphaerodromiinae Guinot and Tavares, Reference Guinot and Tavares2003

Diagnosis

“Carapace longer than wide or about as long as wide; rostrum projecting beyond orbits; orbital area composed of two contiguous circular depressions, outer depression deeper, essentially continuous with orbit, poorly separated from orbit; lateral rim merging with or separated only by short distance from outerorbital angle; subhepatic region inflated; cervical groove weak, postcervical and branchiocardiac grooves well defined” (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Karasawa2012, p. 33).

Genus Basidromilites new genus

Type species

Basidromilites glaessneri n. gen. n. sp. by the present designation.

Other species

Basidromilites pastoris (Via, Reference Via1959).

Diagnosis

Carapace subcircular, length nearly equaling width. Maximum width at level of epibranchial region. Front subtriangular, trilobed in dorsal view, axial lobe slightly projected. Entire lateral margin convex, angular. Anterolateral margins broadly arched, bearing small spine and angular, crested, complex node. Small epibranchial spine behind cervical notch. Posterolateral margin broadly convex, bearing a small node behind branchial groove. Cervical groove slightly developed, branchial groove bounded by a ridge, branchiocardiac grooves short, arched, deep. Dorsal regions smooth except for small epibranchial swellings.

Etymology

The generic name combines the root Basi, to match Basinotopus, and dromilites, a common generic name among dromioids.

Remarks

The main characters of Basidromilites n. gen. match the diagnosis of the subfamily Sphaerodromiinae. These include a subglobose carapace of nearly equal width and length, the front projected beyond orbits, the dorsal surface with regions poorly defined, and weakly marked dorsal grooves (Guinot and Tavares, Reference Guinot and Tavares2003; Schweitzer and Feldmann, Reference Schweitzer and Feldmann2010) as indicated in the preceding. Basidromilites n. gen. can be differentiated from Dromidia bedetteae Blow and Manning, Reference Blow and Manning1996 in that the latter exhibits a narrow, U-shaped frontal margin with the lateral spines very projected, a suboval, transversely elongate carapace outline, and a marked suborbital spine that is clearly visible in dorsal view (Blow and Manning, Reference Blow and Manning1996, pl. 1). Quinquerugatus shows peculiar characters, such as a near-straight front in dorsal view, a subpentagonal carapace outline, a very projected suborbital spine that is visible in dorsal view, and urogastric and cardiac regions that are swollen (Franţescu et al., Reference Franţescu, Feldmann, Schweitzer, Fransen, De Grave and Ng2010, p. 260, fig. 3).

Basidromilites glaessneri new species

Figures 5.4–5.9, 7.

Type material

The holotype, an almost complete carapace, is MGSB77599. There is one paratype, MGSB77600, in comparable preservation.

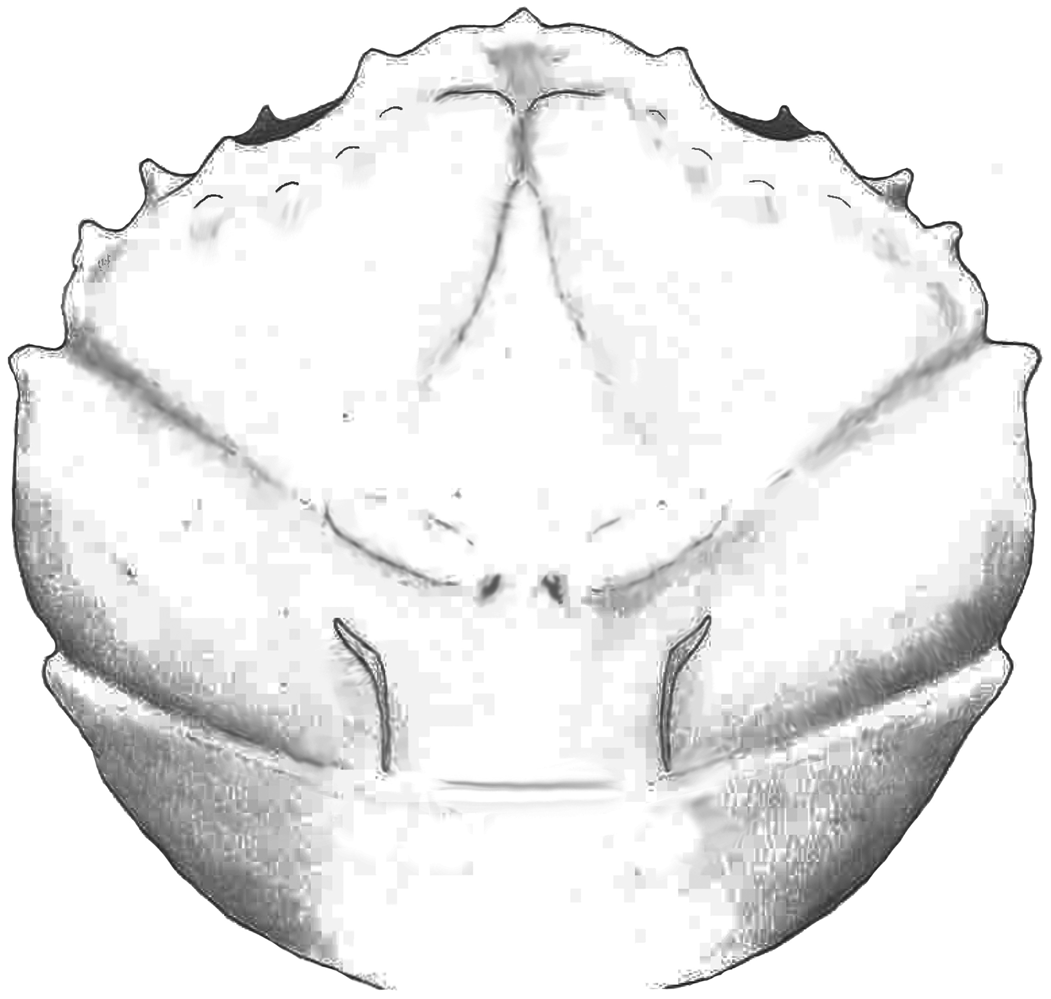

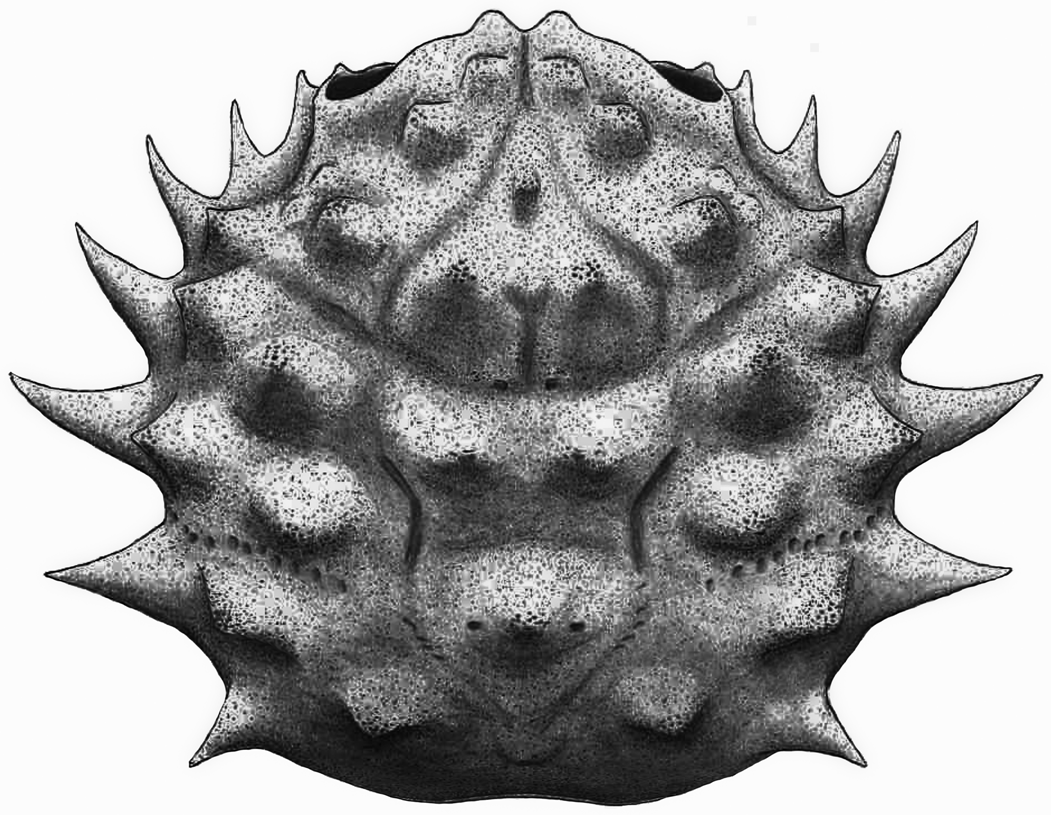

Figure 7. Reconstruction of Basidromilites glaessneri n. gen. n. sp.

Diagnosis

Species of Basidromilites characterized by three clear lobes on frontal margin, with axial one more projected, dorsal surface rather smooth, dorsal grooves weak.

Description

Carapace subcircular. Length nearly equaling the width (length/width ratio about 0.95). Maximum width at level of epibranchial region, about carapace mid-length. Dorsal surface strongly convex in both directions. Front broad, V-shaped in frontal view, short, shallow axial groove, strongly deflexed axially, broadly triangular, trilobed in dorsal view, with two robust lateral lobes; the two inner orbital lobes robust, not very projected; axial lobe situated in a lower plane, short and robust, subtriangular, directed forward, visible in dorsal view. Orbits large, anterolaterally directed, slightly raised in lateral portion, with suborbital spine visible dorsally; subelliptical in frontal view, bearing two small spines on suborbital margin.

Entire lateral margins markedly ridged, angular in cross section, bearing four projected nodes and two notable notches (Figs. 5, 7). Anterolateral margin broadly arched, bearing two strong lateral hepatic spines and strong epibranchial spine, with broadly triangular base; portion behind orbit short, arched. First lateral spine short yet robust, with blunt tip, not very projected, second node complex, composed of three ridged lobes, first two more pronounced. Posterolateral margins of equal size, broadly arched, bearing a strong branchial indentation and blunt yet robust branchial node. Entire lateral margin with two notable indentations, corresponding to cervical and branchial grooves. Posterior margin not well preserved.

Dorsal regions barely differentiated. Epibranchial regions well defined by two small subcircular swellings. Hepatic and suborbital regions bearing small tubercle. Mesogastric and urogastric regions undifferentiated, large, smooth. Epibranchial region large. Cardiac region defined only by branchiocardiac grooves. Ventral portions of carapace broadly swollen, suborbital region small, inflated; subhepatic region large, strongly swollen. Cervical groove shallow, V-shaped, weakly marked from side to side of carapace, interrupted by two oblique axial slits, present in ventral portion. Branchial groove well defined, oblique, relatively deep in outer portions, bounded by marked ridge, interrupted by broad cardiac area, deep in ventral portion. Branchiocardiac grooves arched, short.

Etymology

The specific name honors Martin Fritz Glaessner (1906–1989) for his contributions to our knowledge of fossil dromiacean crabs.

Other material examined

Five incomplete carapaces (MGSB77619a–d, MPZ-2021/162).

Remarks

The new genus differs from species of Dromilites (e.g., D. bucklandii Milne Edwards, Reference Milne Edwards1837; D. belli Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Robin, Charbonnier and Saward2017; D. montenati Robin et al., Reference Robin, van Bakel, Pacaud and Charbonnier2017; D. vicensis Barnolas, Reference Barnolas1973), which all have a frontal margin with two prominent lateral nodes, an axial node that is barely visible in dorsal view (see Milne Edwards, Reference Milne Edwards1837; Via, Reference Via1959; Barnolas, Reference Barnolas1973; Robin et al., Reference Robin, van Bakel, Pacaud and Charbonnier2017; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Robin, Charbonnier and Saward2017) while usually the dorsal grooves are more clearly marked (see Barnolas, Reference Barnolas1973), and a trend to have dorsal swellings (see Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Robin, Charbonnier and Saward2017).

However, the frontal margin in Dromilites pastoris Via, Reference Via1959 is similar to that of the present species, with a slightly projected axial lobe and similar cervical and branchial grooves. Dromilites pastoris does differ in having three small, lobe-like hepatic nodes anterior to the cervical groove and two small lateral nodes behind the cervical groove, two clear cardiac pits, and a prominent ridge behind the branchial groove. On this evidence, D. pastoris is reassigned to the new genus.

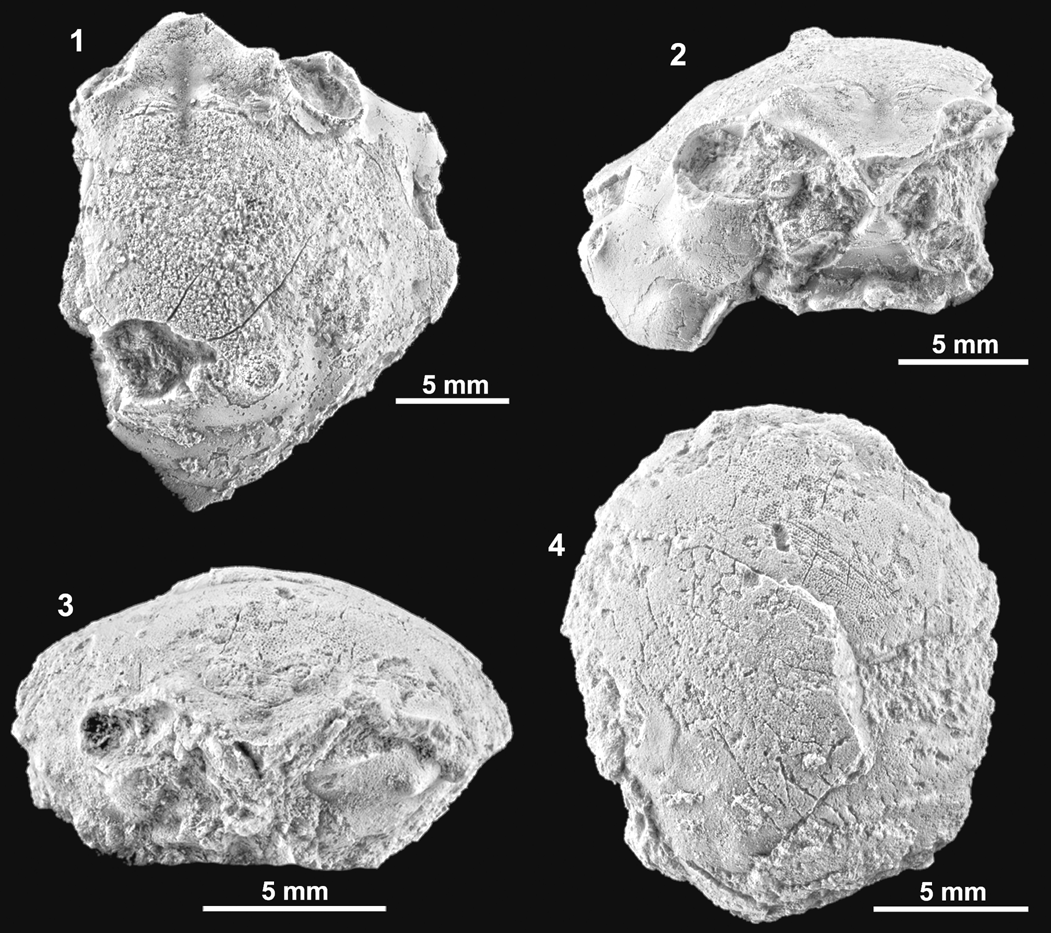

Basidromilites sp.

Figures 8.3, 8.4

Description

Carapace suboval, longer than wide (length/width ratio about 1.14). Maximum width probably at level of epibranchial region, about carapace mid-length. Dorsal surface strongly convex in both directions. Front broad, conspicuously deflexed axially, broadly triangular, trilobed in dorsal view, with two robust lateral nodes; the two outer orbital lobes strong, robust, not very projected; axial lobe situated in lower plane, directed forward, barely visible in dorsal view. Front V-shaped in frontal view, shallow axial depression. Orbits large, anterolaterally directed, margins markedly raised; subelliptical in frontal view, with outer orbital corner pointed. The whole lateral margins not well preserved, appearing to have been angular in cross section. Anterolateral margin with one small hepatic node and larger posterior node anterior to cervical notch and one larger lobe posterior to cervical notch. Posterolateral margin somewhat longer, bearing angular lobe in front of branchial notch. Posterior margin not preserved. Gastric regions undifferentiated except for two small epigastric inflations. Branchial regions large, broadly swollen, separated by weak branchial groove. Hepatic region small, barely differentiated. Cervical and branchial grooves weakly developed, more visible in distal portion. Branchiocardiac grooves not well preserved. Dorsal surface densely covered by diminutive pits.

Figure 8. Specifically indeterminate dromiids from the Serraduy Formation (Huesca, North Spain). (1, 2) ?Basinotopus sp. (MGSB77912) in dorsal and frontal views, respectively. (3, 4) Basidromilites sp. (MGSB77628) in frontal and dorsal views, respectively.

Material

A single, near-complete carapace, MGSB77628.

Remarks

The slightly projected frontal margin, with three discrete nodes, and the lobes on the lateral margins (mainly the angular hepatic lobe) are similar to Basidromilites n. gen. The smooth carapace with weak cervical and branchial grooves also matches the diagnosis of that new genus. Basidromilites sp. bears a more elongated carapace outline and more weakly marked dorsal carapace grooves than Basidromilites glaessneri.

Family incertae sedis

Genus Basinotopus M'Coy, Reference M'Coy1849

Type species

Dromilites lamarckii Desmarest, Reference Desmarest1822 by monotypy.

?Basinotopus sp.

Figure 8.1, 8.2

Material

A single incomplete carapace, MGSB77912.

Description

Carapace of probable elongate outline. Maximum width probably at level of epibranchial region, about carapace mid-length. Dorsal surface strongly convex in both directions. Front broad, deflexed axially, broadly triangular, trilobed in dorsal view, with two robust lateral spines; the two inner orbital spines strong, robust, not very projected, with blunt tip, upwardly directed; axial spine situated in lower plane, very robust, broadly subtriangular, directed forward, entirely visible in dorsal view. Front V-shaped in frontal view, shallow axial depression. Orbits large, anterolaterally directed, margins markedly raised, with suborbital spine and suborbital margin, clearly visible dorsally; subelliptical in frontal view, bearing strong spine, with broadly triangular base on suborbital margin. Lateral margins not well preserved. Epigastric regions with small yet distinct swellings. Mesogastric regions well defined by large, projected, subcircular lobes. Hepatic region small, bearing small subcircular swelling. Suborbital and subhepatic regions large, broadly swollen. Cervical groove marked only in axial portion. Epistome robust, large, subtriangular.

Remarks

This dromioid is of robust appearance, with thick cuticle and stout marginal nodes. The projected front, and particularly the robust axial spine, plus the two lateral spines recall Basinotopus tricornis Collins and Jakobsen, Reference Collins and Jakobsen2004. As seen in the genus Basinotopus are also the closed and obliquely directed orbit, with the suborbital margin and suborbital spine well visible in dorsal view. The main diference is the smooth or pitted carapace surface, which is also characteristic of Lucanthonisia Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Artal, Fraaije and Jagt2009. Features preserved in MGSB77912 match those of genera assigned to the Basinotopinae (Karasawa et al., Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Karasawa2012).

Family Dynomenidae Ortmann, Reference Ortmann1892

Subfamily Paradynomeninae Guinot, Reference Guinot2008

Diagnosis

“Body thick, uniformly covered with tubercles, granules and/or spines. Carapace longer than wide or as long as wide, sometimes slightly wider than long, subquadrangular, may be suboval; dorsal surface convex, distinctly areolated, often with swellings or bosses, usually densely ornamented. Cervical groove entire, not reaching lateral carapace margin; frontal, cervical, branchial, branchiocardiac grooves pronounced. Anterolateral margins subparallel or slightly convex, distinctly joining corners of buccal cavity, armed with 4–6 irregular salient teeth or prominences. Posterolateral margin with produced and elongated subdistal tooth; a tooth present posteriorly, variously salient. Posterior region of carapace recessed; posterior margin strongly concave. Frontal margin usually distinctly projecting, tridentate, rarely bidentate; supraorbital margin with small tubercles, notch; infraorbital margin with granules, teeth, notches. Orbits oblique, clearly visible from dorsal view” (Guinot, Reference Guinot2008, p. 11–13).

Genus Kromtitis Müller, Reference Müller1984

Type species

Dromilites koberi Bachmayer and Tollmann, Reference Bachmayer and Tollmann1953, by monotypy.

Other species included

K. bicuspidatus Beschin, De Angeli, and Zorzin, Reference Beschin, De Angeli and Zorzin2009b; K. daniensis Collins, Reference Collins2010; K. koberiformis Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2007; K. levigatus Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2007; K. lluisprietoi Ossó, Reference Ossó2019; K. pentagonalis Müller and Collins, Reference Müller and Collins1991; K. pseudolothi Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonello2016b; K. spinulata Portell and Collins, Reference Portell and Collins2004; K. subovatus Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2007; K. tergospinosus Beschin, Busulini, and Tessier in Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, Fornaciari, Papazzoni and Tessier2018; K. tetratuberculatus Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2002.

Type material

The holotype, MGSB75450, is a complete carapace (16 mm long and 15 mm wide) with well-preserved cuticle. There are two paratypes, MGSB75451a, b.

Figure 9. Kromtitis isabenensis n. sp. from the Serraduy Formation (Huesca, Spain). (1, 2) Holotype (MGSB75450) in dorsal and posterior views, respectively. (3–5) Paratype (MGSB75451a) in dorsal, left lateral, and frontal views, respectively. (6, 7) MGSB77633 from Carrasquero, near Ramals, in dorsal and posterior views, respectively. (8–10) Isolated propodus, presumably of Kromtitis isabenensis n. sp., in left lateral, frontal, and dorsal views, respectively (MPZ-2021/163).

Figure 10. Reconstruction of Kromtitis isabenensis n. sp.

Diagnosis

Carapace subquadrate, slightly wider than long, lateral margins arched; frontal margin projected, with two inner orbital nodes and deep axial notch; orbits inclined, with oblique supraorbital and suborbital margins; anterolateral margins broadly arched, bearing six robust, subtriangular spines; posterolateral margin converging posterorly, bearing a strong spine and notable concavity behind epibranchial spine; posterior margin straight; dorsal regions well defined by numerous raised swellings with rounded sides; metabranchial region with horizontal row of four swellings; dorsal surface uniformly and densely granulate.

Description

Carapace subquadrate, lateral margins arched, slightly wider than long (length/width ratio about 0.85). Maximum width at level of epibranchial region, about carapace mid-length. Dorsal surface convex in both directions. Front V-shaped in frontal view, narrow, granulated, strongly deflexed axially, broadly triangular, with deep axial groove; bilobed in dorsal view, with two robust lateral nodes and V-shaped axial incision; the two inner orbital nodes strong, robust, markedly projected. Orbits large, anterolaterally directed, granulated, slightly raised in lateral portion; margin strongly angular in outer corner, with two suborbital nodes visible dorsally; subelliptical in frontal view, bearing acute outer spine and stout inner lobe on suborbital margin. Entire lateral margins broadly arched, bearing numerous projected spines and small posterior concavity; postbranchial spine is the largest. Anterolateral margin broadly arched, bearing at least three projected irregular spines anterior to cervical notch, and two posterior ones; projected spines covered with numerous tubercles and intermediate space bearing acute granules; portion behind orbit short, arched. Posterolateral margins of similar length, slightly sinuous, bearing a very small epibranchial spine, slight concavity, relatively long and acute projection, and blunt posterior node. Posterior margin concave, equaling orbitofrontal margin in length. Dorsal regions defined by swollen lobes and shallow depressions. Dorsal grooves shallow, weakly marked. Cervical groove weakly defined, deeper in ventral portion of carapace. Branchial groove weakly marked in marginal portion, deeper in ventral portion of carapace. Branchiocardiac grooves arched. Mesogastric region subtriangular, with arched base, bounded by shallow cervical groove; posterior portion defined by two strong protuberances separated by shallow depression; narrow anterior extension bearing small swelling. Protogastric region large, posterior portion defined by strongly projected swelling, anterior portion elongated, joining epigastric swellings. Hepatic region small, bearing small tubercle. Urogastric region low, narrow, with two lateral tubercles. Epibranchial region large, inner portion defined by strong subcircular elevation, usually barely divided by a median sulcus; outer portion bearing two smaller elevations, anterior rounded, small, posterior stronger, with acute tip. Mesobranchial region depressed. Metabranchial regions large, with two strong protuberances, outer portion larger, reaching posterolateral carapace corner. Cardiac region large, raised, subpentagonal inverted in shape, anterior portion bearing strong elevations, apex barely marked. Intestinal region small, depressed. Dorsal surface densely covered by tiny granules.

Etymology

The specific name refers to the municipality of Isabena, located a few kilometers to the south of the study area.

Other material examined

MGSB77635a, b, two incomplete carapaces from Barranco de Ramals. Another well-preserved carapace, MGSB77633, originates from the neighboring locality of Carrasquero (Huesca). In addition, there are 30 isolated propodi (MGSB85952; MPZ-2021/163–2021/171).

Remarks

Kromtitis isabenensis n. sp. can be differentiated from congeners on the basis of its projected front, with a deep V-shaped notch; oblique supraorbital margins, inclined at about 45°; a lateral margin with stout and subtriangular spines; a different distribution of dorsal regions, with broadly rounded tips; and a dorsal surface that is densely and uniformly covered by tiny granules.

The genus Kromtitis has previously been linked to certain extant dynomenids, such as Paradynomene Sakai, Reference Sakai1963 (see Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2007, p. 27; Guinot, Reference Guinot2008, p. 21). In K. isabenensis, as well as in its congeners, all features are those also seen in modern representatives of the subfamily Paradynomeninae (see McLay and Ng, Reference McLay and Ng2005). The four tubercles in the posterior carapace portion (metabranchial area) in K. isabenensis are a diagnostic feature of the genus Paradynomene (see McLay and Ng, Reference McLay and Ng2005). This conservative character has often not been mentioned in previous papers. The concavities in the posterolateral margins are also remarkable. Finally, the orbitofrontal construction is similar, in dorsal view, in both K. isabenensis and P. tuberculata Sakai, Reference Sakai1963 (McLay and Ng, Reference McLay and Ng2004, p. 5).

Kromtitis isabenensis is morphologically close to K. lluispietroi Ossó, Reference Ossó2019 (both have a subquadrate outline, granular nodes on the lateral margins, and similarly distributed dorsal regions). However, the latter is easily distinguished in having clearly deeper cervical groove, an inner epibranchial swelling that is clearly separated into two differentiated portions, one below the other, and a dorsal surface that is covered by nonuniform and irregular granules (“surface sparsely granulate with coarse granules,” according to Ossó, Reference Ossó2019, p. 3). In addition, the dorsal regions are covered by numerous tubercles of different sizes, the spines on the lateral margins are composed of numerous tubercles of different sizes, and the concavity in the posterolateral margin is more clearly marked.

The new species is also close to K. koberiformis, but that species differs in having a straighter front with projected inner orbital spines. In addition, the posterior margin is straighter and broader and dorsal regions clearly differentiated, smaller, and more raised, like large tubercles. The dorsal granulation is also dense, but with larger and more irregular granules. Kromtitis koberi, type species of the genus, is easily distinguished by its more clearly ridged dorsal regions and irregular granules that are seen only on the highest portions of carapace regions. Kromtitis tetratuberculatus has an arched frontal margin, larger, more rounded swellings in dorsal regions, and larger dorsal granules, while K. subovatus exhibits a projected frontal margin with a less clearly developed median notch, and dorsal regions are more strongly tuberculated with less-evident dorsal granulation. Kromtitis levigatus differs even more, with a straight frontal margin, dorsal regions with fewer divisions, and a lack of small granules on the dorsal surface.

The sole American species, K. spinulata, is characterized by a nearly subelliptical outline, being wider than long, a projected axial portion of the frontal margin, long and acute spines on the lateral margins, and a lack of surface granulation. Kromtitis pentagonalis is clearly distinct in having larger, close-set dorsal swellings on dorsal regions, with limited space between them, and a smooth dorsal surface, without granules (Müller and Collins, Reference Müller and Collins1991, pl. 3).

Genus Sierradromia new genus

Type species

Sierradromia gladiator n. sp. by present designation.

Diagnosis

Carapace transversely subelliptical, slightly wider than long; frontal margin projected, with two strong inner orbital spines and a deep axial notch; entire lateral margins broadly arched, bearing seven long, robust, and dorsoventrally flattened spines; posterior margin narrow, nearly straight; dorsal regions conspicuously subdivided, with numerous strongly raised, conical swellings; two longitudinal axial grooves bounding mesogastric, urogastric, and cardiac regions; tips of dorsal regions with perforations.

Etymology

The generic name derives from its resemblance to a mountain range, sierra in Spanish, and the suffix dromia.

Remarks

The placement of extinct genera within the Dromiacea has always been controversial (Guinot, Reference Guinot2008, Reference Guinot2019; Guinot et al., Reference Guinot, Tavares and Castro2013). Ventral characters are rarely preserved in fossil brachyurans, which explains why genera have been assigned to different families or subfamilies on the basis of few characters, in most cases only those of dorsal carapace (Schweitzer and Feldmann, Reference Schweitzer and Feldmann2010; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Garassino, Karasawa and Schweigert2010, Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Karasawa2012; Karasawa et al., Reference Karasawa, Schweitzer and Feldmann2011). On the basis of particular dorsal carapace features, such as arched lateral margins, a projected frontal margin with two intraorbital nodes and a deep axial notch, inclined orbits with oblique supraorbital and suborbital margins, broadly arched anterolateral margins with some spines, a backward-converging posterolateral margin, well-defined dorsal regions by raised swellings, and a metabranchial region with a horizontal row of four swellings (in this case conical spines), we tentatively place Sierradromia n. gen. in the subfamily Paradynomeninae.

Sierradromia gladiator new species

Figures 11, 12

Type material

Holotype, a near-complete carapace, is MGSB75454. There are two paratypes, both of which are slightly compressed: MGSB75455a, b.

Figure 11. Sierradromia gladiator n. gen. n. sp. from the Serraduy Formation (Huesca, Spain). (1, 2) Holotype (MGSB75454) in dorsal and right lateral views, respectively. (3) Dorsal view of paratype (MGSB75455a) with some epibionts (serpulids and oysters). (4–6) Paratype (MGSB75455b) in dorsal, frontal, and right lateral views, respectively.

Figure 12. Reconstruction of Sierradromia gladiator n. gen. n. sp.

Diagnosis

As for genus (monotypy).

Description

Carapace subelliptical, slightly wider than long (length/width ratio about 0.91). Maximum width at level of epibranchial region, just posterior to second epibranchial spine. Dorsal surface strongly convex in both directions, flanks of carapace oblique. Front V-shaped in frontal view, narrow, deflexed axially, fairly bilobed in dorsal view, with two notable lateral spines and deep axial indentation, deep axial groove; the two inner orbital spines robust, short; axial node situated in lower plane, not visible in dorsal view.

Orbits large, anterolaterally directed, slightly raised in lateral portion, with strong suborbital spine visible dorsally; subelliptical in frontal view; bearing a strongly projected, robust subtriangular spine on ventral orbital region. The whole lateral margins with seven robust spines and three notably deep notches. Anterolateral margin broadly arched, with two strong hepatic spines and two projected epibranchial spines, portion posterior to outer orbital corner strongly concave. All projections robust, dorsoventrally flattened, laterally and upwardly directed; two epibranchial largest, with broad subtriangular base, separated by short yet deep indentation. Posterolateral margins of similar length, broadly arched, bearing two strong spines in meso- and metabranchial marginal sides, strongly projected, dorsoventrally flattened, and upwardly directed. Posterior margin nearly straight, weakly concave, slightly narrower than orbitofrontal margin.

Dorsal regions well defined by shallow grooves and projected protuberances; axial swellings with rounded tip, upwardly directed, marginal swellings more conical, laterally directed. Mesobranchial region subtriangular with rounded sides; defined by two strong posterior protuberances and a smaller axial protuberance in anterior extension. Protogastric region defined by two protuberances of similar size, situated obliquely. Epigastric regions small, two transverse inflations separated by shallow groove. Hepatic region small, bearing weak conical swelling. Urogastric region inverted subtrapezoidal in shape, large, broad, and long, bearing two strong swellings with rounded tips. Cardiac region large, subpentagonal, transversely inflated, anterior portion with large pits. Epibranchial region large, bearing four conical protuberances. Meso- and metabranchial regions undifferentiated, bearing two transverse inflations. Intestinal region small, depressed. Ventral portion of carapace with conical suborbital spines and subhepatic and subbranchial inflations. Cervical groove shallow but well defined, well marked on ventral side and notching lateral margins. Branchial groove barely marked, bearing irregular small inflations and pits, reaching and notching lateral margins. Branchiocardiac groove sinuous, relatively deep. Dorsal surface densely covered by diminutive pits, bearing small perforations, mainly on highest part of the swollen regions.

Etymology

The specific name “gladiator” refers to the fictitious Roman legionary, Maximus Decimus Meridius, in view of the resemblance of the carapace to the helmet that he wears in the film The Gladiator.

Other material examined

MGSB77629a–q; MGSB77913a–e; MPZ-2021/50; MPZ-2021/172; MPZ-2021/173.

Remarks

The new taxon is clearly distinct from Kierionopsis nodosa Davidson, Reference Davidson1966 (see also Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Nyborg, Bishop, Ossó-Morales and Vega2009, p. 749), which was assigned to the Dromiinae (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann, Garassino, Karasawa and Schweigert2010) and subsequently transferred to the Dynomenidae (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Feldmann and Karasawa2012). The genus Kierionopsis Davidson, Reference Davidson1966 differs in having a much more elongated outline and in the number and shape of the spines on the lateral margins, the deeper cervical and branchial grooves, and the differently situated dorsal regions that are also distinct in shape and number, mainly the cardiac region, which is extremely raised and directed backward.

Sierradromia gladiator n. gen. n. sp. is superficially close to Dromilites montenati; however, the latter can be distinguished by the different number, shape, and length of the projections on the lateral margin. In addition, the dorsal regions exhibit important differences in shape, size, and distribution, being defined by small tubercles rather than raised conical swellings, and the dorsal grooves are clearly distinct in shape, course, and depths. The orbits are distinct, and the segment behind the outer corner is utterly different while the posterior margin is extremely concave (weakly concave or nearly straight in the new genus and species), and the carapace outline appears to be more subcircular.

Eocene dromioid crabs in time and space

Modern dromioids are important constituents at tropical and subtropical latitudes and are represented by more than 140 species (e.g., Guinot and Tavares, Reference Guinot and Tavares2003; De Grave et al., Reference De Grave2009). Usually, they are associated with coral- and sponge-rich environments and hard substrates (reefs, forereefs, or coral rubble) ranging from the intertidal to deep waters (1–450 m; e.g., McLay, Reference McLay1993, Reference McLay2001; Takeda and Manuel-Santos, Reference Takeda and Manuel-Santos2006). Dromioids usually carry fragments of sponges or other objects with the help of P4–P5 (Dromiidae) or hide in crevices of coral and other hard substrates (Dynomenidae) (cf. McLay, Reference McLay2001).

The Eocene dromioid assemblage from Ramals corresponds to taxa associated with reef environments. Other localities exposing Paleocene and Eocene rocks across Europe have similar dromiids and dynomenids (e.g., Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, De Angeli and Tessier2007, Reference Beschin, Busulini and Tessier2015, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Tessier and Zorzin2016a, Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonellob, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Fornaciari, Papazzoni and Tessier2018, Reference Beschin, Busulini, Tessier and Zorzin2019; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beschin and Busulini2011). However, all those assemblages are characterized by a low diversity. Decapod crustacean faunules from the middle Danian (lower Paleocene) at Fakse (eastern Denmark) comprise a wide array of dromioids in a coral-rich setting (e.g., Woodward, Reference Woodward1901; Wienberg Rasmussen, Reference Wienberg Rasmussen1973; Collins and Jakobsen, Reference Collins and Jakobsen1994; Jakobsen and Collins, Reference Jakobsen and Collins1997; Collins, Reference Collins2010). However, species and genera are different from those studied in the present work; dynomeniform crabs, in particular, are clearly distinct, with four species of Dromiopsis Reuss, Reference Reuss1859 (Jakobsen and Collins, Reference Jakobsen and Collins1997). The present faunule resembles the dromioid fauna from the Danian of the Paris Basin (France), with merely a single dynomenid and sphaerodromiid taxon each (Robin et al., Reference Robin, van Bakel, Pacaud and Charbonnier2017). The early Eocene faunas in northern Italy document an intermediate diversity, with at least four species of Dromiopsis and other paradynomenid forms. The only taxon in the Spanish assemblage in common with the Ypresian of Italy is the genus Kromtitis, with three recorded Italian species (Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, Busulini, Tessier and Zorzin2016a, Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonellob). Only three species of dromioids have been recorded from the Ypresian of the United Kingdom: two sphaerodromiids and one basinotopid (Collins, Reference Collins2003; Van Bakel et al., Reference Van Bakel, Robin, Charbonnier and Saward2017). Deposits of Ypresian/Lutetian age in Denmark share only a single basinotopid (Collins and Jakobsen, Reference Collins and Jakobsen2004) with the Huesca assemblage. Thus, the Ramals faunule includes novel forms of dromioids that appear for the first time at such latitudes during the Eocene. Morphologically more modern dromioids are known mainly from Lutetian strata in Italy (Busulini et al., Reference Busulini, Tessier, Visentin, Beschin, De Angeli and Rossi1983; Beschin et al., Reference Beschin, De Angeli, Checchi and Zarantonello2005) and Catalonia (Via, Reference Via1969; Solé and Via, Reference Solé and Via1989).

The Eocene record of dromioids includes 58 species described to date (Table 1). Many of these are known from basins in the Mediterranean area and are related mainly to coral-rich settings (56%) (see Tables 1, 2). On the basis of sedimentological data, a preference for reef environments appears likely for the Ypresian (lower Eocene); almost all published occurrences stem from such depositional settings. This can be related to the development of “modern” reef complexes because of climatic and environmental conditions at the time (see Pomar et al., Reference Pomar, Baceta, Hallock, Mateu-Vicens and Basso2017), which enabled dromioids to inhabit such settings. However, during the middle Eocene, this trend appears to have reversed, and higher diversities then occur in siliciclastic or nonreef environments over shallow platforms. This could be related to a switch in environmental preferences of dromioids at that time and their expansion into siliciclastic environments, but it might also be linked to the poor record of reef facies in this time interval. Finally, during the late Eocene, a new increase in diversity is observed in reef settings.

Table 2. Summary of environmental distribution patterns, as listed in Table 1.

The abundance and diversity of dromioids at Ramals suggest this group was diversified and specialized for inhabiting this type of coral-rich environment during the early Eocene. It was probably related earlier with the Cretaceous Crab Revolution (see Schweitzer and Feldmann, Reference Schweitzer and Feldmann2015; Luque et al., Reference Luque2019), documenting several species that are closely similar to extant forms. Our present data support the widely accepted view that past reefs were biodiversity hotspots (e.g., Förster, Reference Förster1985; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Krobicki and Wehner2000; Krobicki and Zatoń, Reference Krobicki and Zatoń2008; Klompmaker, Reference Klompmaker2013; Klompmaker et al., Reference Klompmaker, Schweitzer, Feldmann and Kowalewski2013). The great diversity within a single group of decapod crustaceans (i.e., dromioids) is probably related to the location of the study area within reef mounds and associated coral rubble under mesophotic conditions, as well as to abundant crevices that this environment provided for refuge, feeding, and other interactions.

Although the present work discusses only a single reef mound environment of middle Ypresian (early Eocene) age, similar studies in other areas could potentially provide important ecological data on the distribution of dromioid crabs in ancient marine settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at MGSB for allowing access to the historical collections. J.E. Ortega, A. Onetti, and A. Ortiz donated important specimens to this study. I. Pérez provided photographic assistance. The present work has been supported by CGL2017-85038-P, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, the European Regional Development Fund, and Project E18 “Aragosaurus: Recursos Geológicos y Paleoambientes” of the government of Aragón-FEDER. The research of F.A. Ferratges is funded by an FPU grant (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation). Two reviewers J.W.M. Jagt (Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht, Maastricht) and C.E. Schweitzer (Kent State University) and associate editor J. Luque (Harvard University) greatly improved an earlier version of the typescript.